Sharada Srinivasan (2014)

This paper attempts a historiography of the Nataraja bronze which famously came to wider international attention through Ananda Coomaraswamy’s (1912) essay, ‘Dance of Siva’, and his explorations into its symbolism; for which he is arguably best known in posterity. Cast over several hundred centuries, however, with few associated inscriptions, there have been some lacunae in understanding its development in stone and bronze. There have also been debates about the actual or original significance since Coomaraswamy’s interpretations seemed to have been based on later texts. Although this bronze is almost synonymous with the Imperial Chola dynasty of Tamil Nadu, there is a certain lack of clarity on earlier and later manifestations and other regional developments in India and in spheres of interaction beyond such as Sri Lanka. Insights from archaeometallurgical and stylistic study and documentation of surviving bronze casting practices in Tanjavur district throw new light on techno-cultural aspects of south Indian bronzes and this enigmatic icon. The place the image has acquired in the global imagination through the writings of well known artists, scientists and thinkers following Coomaraswamy’s musings is briefly elucidated here, as well as his contributions to the documentation of arts and crafts and the archaeometallurgy of the southern Indian subcontinent.

‘Archaeometallurgy’ in the southern Indian subcontinent and Coomaraswamy’s role in arts and crafts awareness

In the past few decades, the discipline of archaeometallurgy has emerged as an important sub-discipline in archaeology and scientific archaeology. It is concerned with the application of scientific techniques in the study of metal artefacts, not only for understanding their methods of manufacture from related studies of mining, metal extraction or alloying but also for the implications of technical analysis in gaining further insights into issues concerning the history of art such as the source of artefacts and stylistic affiliations. The stature of Ananda Coomaraswamy (1877-1947) as a towering art historian of the twentieth century is well known through his writings integrating visual art, religion, literature and metaphysics. However, what is perhaps less well recognized is that even in terms of these recently defined fields of ‘archaeometallurgy’ and ‘ethnoarchaeology’ his contributions are equally seminal, especially concerning the southern part of the Indian subcontinent. From his education as a scientist and geologist he turned his interests towards the documentation of artisanal technologies and crafts including metalworking. In this sense, his work in some ways even anticipated that of Cyril Stanley Smith, another Renaissance personality and materials scientist and aesthetician who is recognized as a founding figure in the field of archaeometallurgy. A student of botany and geology at the London University who in fact distinguished himself by discovering Thorianite (Rangarajan 1992), Coomaraswamy took up the post of Director of the Mineralogical Survey of the island (Moore in Foreword, Coomaraswamy 1909).

Coomaraswamy’s (1951: 190-3) early documentation of finds of iron smelting slags at Tissamaharama and ethnographic studies of iron smelting and furnaces near Balagoda and of steel making by elderly artisans in Alutnuvara are pioneering in terms of early archaeometallurgical studies related to Sri Lanka and indeed South Asia.

What sets Coomaraswamy apart though, is the way in which his interests were tempered by a deeply humanistic concern for the milieu of the traditional craftsmen and artisans and his efforts to revitalize them. Through his geological and rural fieldwork experiences, from around 1902 he became much more concerned and engaged with documenting the traditional arts and crafts of Ceylon in terms of social history and social conditions. Although he was part English, he became very perceptive to the negative effects that European colonization had had on the traditional artisanal knowledge of South Asia. He founded the Ceylon Social Reform Society in 1906 which had as its aim the discouragement of ‘thoughtless imitation of unsuitable European customs’ and preservation of traditional crafts and the social values that had shaped them (Oldmeadow 2004: 194-202). He was among the leading figures who took an early interest in the Indian crafts and its revival including Sir George Birdwood and E.B. Havell. His writings about the Indian craftsman still ring true: ‘Indian society presents to us no more fascinating picture than that of the craftsman as an organic element in the national life…’ (Coomaraswamy 1909: Foreword by A. Moore). He was also involved in the Swadeshi movement promoted by key figures such as MK Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore, in terms of the need for sustaining traditional artisanship. These movements also set the stage for post-Independence developments, whereby Mangalore-born Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay almost single-handedly turned around the situation on Indian crafts with the setting up of All India Handicrafts Board and through her far reaching engagement.

‘Dance of Siva’ and the world stage

Son of a Ceylonese Tamil father Muthu Coomaraswamy, a legislator and philosopher who died when he was a baby, and an English mother, Elizabeth Beeby, it seems that the languages that Coomaraswamy held mastery over, in terms of his art historical and philosophical expositions were Sanskrit and Pali, the language of the rich body of Theravada Buddhist canon followed by the Sinhalese majority of his homeland, rather than Tamil. Nevertheless, it may be fitting in the light of his ancestry that perhaps Coomaraswamy’s genius as a writer flourished most eloquently in his inspired exposition of the Nataraja bronze made famous in Chola bronzes from Tamil Nadu, of the dancing Hindu god Shiva, and based on his interpretations of Tamil Saiva Siddhanta texts. His background as scientist-aesthetican comes through in his essay ‘The Dance of Siva’ (1912), where he wrote: ‘In the night of Brahma, Nature is inert, and cannot dance till Shiva wills it. He rises from His rapture, and dancing sends through inert matter pulsing waves of awakening sound, and lo! matter also dances appearing as a glory round about Him. Dancing He sustains its manifold phenomena. In the fullness of time, still dancing, he destroys all forms and names by fire and gives now rest. This is poetry; but none the less science.’

Coomaraswamy’s (1912) interpretation of the Nataraja bronze appealed widely to leading figures of his time (Srinivasan 2010). His writings, such as the passage above, seem to be echoed in T.S. Eliot’s famous poetic lines ‘At the still point of the turning world…there the dance is…’ Celebrated French sculptor August Rodin (1913) in his essay ‘La Danse de Siva’ illustrated it with the same Nataraja bronze from the Government Museum, Chennai as did Coomaraswamy. His writings also provided something of a post-modernist metaphor for savouring the implications of modern physics. Fritjof Capra (1976: 258) further catapulted the Nataraja into the global spotlight by writing that, as envisaged through Coomaraswamy’s writings, ‘Siva’s dance is the dance of sub-atomic particles’ (Srinivasan 2003). Such writings also led astronomer Carl Sagan to state that the Nataraja bronze held out a premonition of astronomical ideas. The distance traversed by such eastern art forms onto the world stage can be gauged from the fact that the CERN Cosmic Lab, which has witnessed recent excitement over the Higgs Boson (also nicknamed the ‘God particle’), has the largest Nataraja image in the world today, installed there with plaques citing quotes from Coomaraswamy and Capra. This impressive work had been undertaken by the master craftsman Rajan with support from IGCAR Kalpakkam (Baldev Raj, pers comm.). The Nataraja bronze figured on the dust jacket of Belgian scientist Ilya Prigogine’s book (Glansdorff and Prigogine 1971) as if providing visual metaphors for abstract concepts related to thermodynamics, flux and stability. Notwithstanding the romanticism, Coomaraswamy’s writings assume significance in the ways they engaged Eurocentric western audiences in his times towards a better rapprochement of Indian thought and art. Coomaraswamy’s transcendental approach to Indian art influenced leading art historians such as Stella Kramrisch (Oldmeadow 2004), though in recent times art history has seen newer revisionist approaches.

Insights from bronze casting traditions at Swamimalai, Tanjavur district

![]()

Micro-structure of 13thSouth

Indian bronze

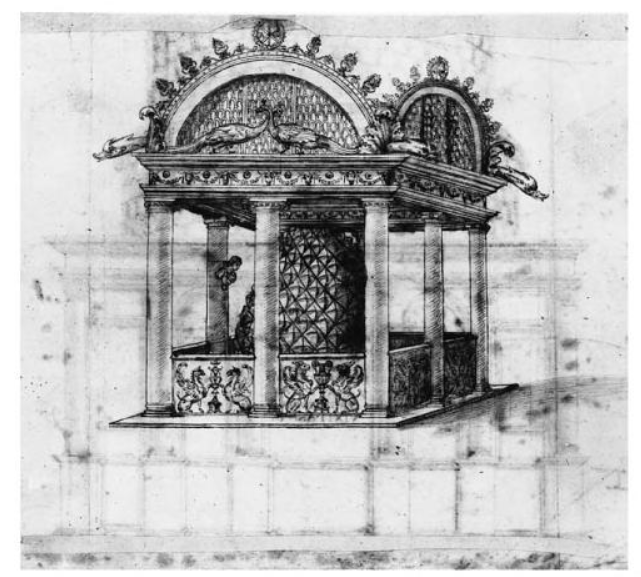

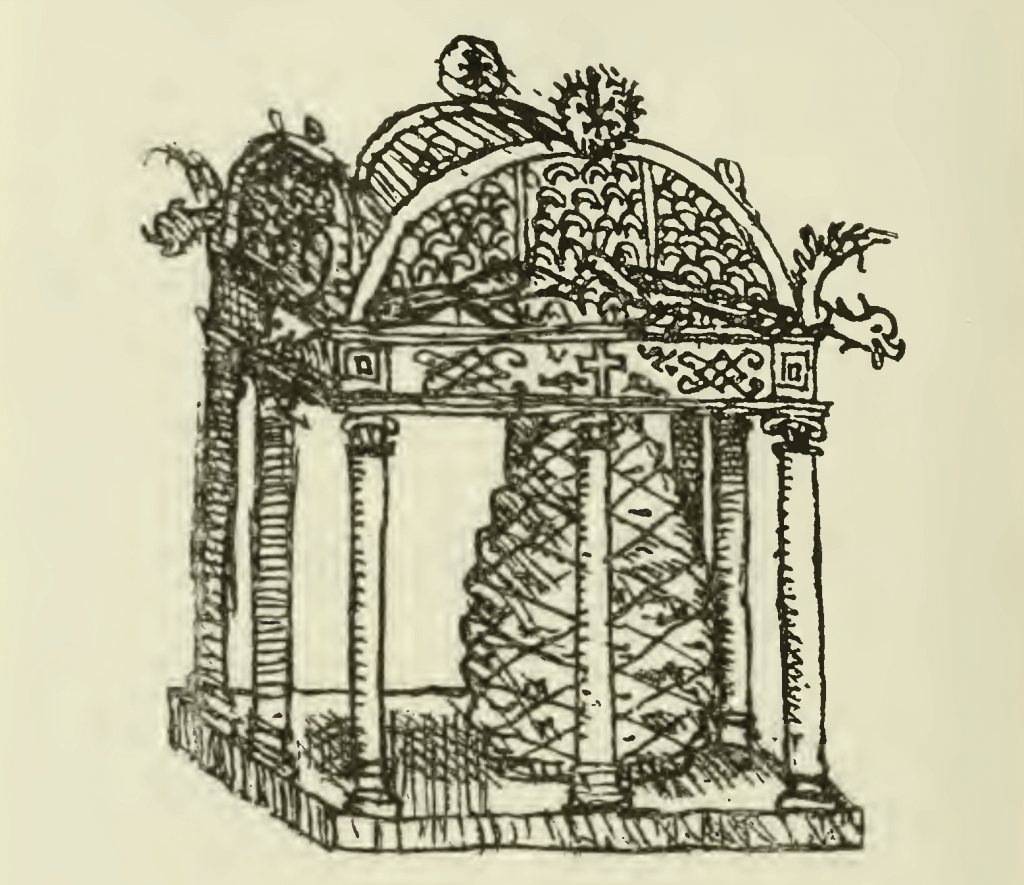

Images were made in southern India of Hindu, Buddhist and Jain religious affiliations. Whereas Buddhist and Jain bronzes often have donor inscriptions, Hindu images were rarely inscribed. An overwhelming majority of south Indian bronzes, especially of Hindu affiliation, are from the Tamil region and more specifically the Tanjavur region. South Indian metal Hindu icons were made as utsava murti or festival images that were taken out in rituals and festivals involving processional worship and were not generally intended for worship in the main sanctum. South Indian statuary bronze is made by a process of cire perdue or lost wax casting, a technique which has a long history in the subcontinent. The lost wax processes known as Madhuchchhisthavidhana is also described in the southern Indian text the Manasollasaattributed to the Chalukyan king Somesvara. The Kasyapa Silpasatra, a Tamil text discusses iconometric aspects of the modelling of the image including the navatala methods of proportioning the icon derived from texts such as the Brhat Samhita.

Chola inscriptions describe the image of the deity as ghanamagha or dense, i.e. solid, and the bull or rishabha as chhedya or hollow cast. As an example, a fine set of Chola bronzes from Tandanttottam is cast such that the main images of Rishabhavahana and consort are solid cast and the damaged bull is hollow cast (Sivaramamurti 1963: 14). Present day sthapatis or icon makers also maintain that the metal deities for processional worship in temples should never be hollow cast because that would be inauspicious although this rule does not apply to the vahana or the vehicles in animal forms associated with deities. According to Coomaraswamy (1956:154) and Von Schroeder (1981:19), the Sariputra, a Ceylonese text (ca 12th-15th century) based on South Indian sources warns against the making of hollow images which would lead to calamities such as famine and warfare. Interestingly, although early historic images both from southern India such as Amaravati and Sri Lanka tend to be hollow cast, from the early medieval period they are invariably solid cast, unlike northern Indian images which are most often hollow cast.

Unlike European sculptures which were usually made from physical models, South Indian icon makers in the past are thought to have not used models but were expected to memorise all thetalamana canon of measurement and then invoke the images of the deities in their minds usingdhyanaslokas or verses which were meant to help mentally visualise the qualities and attributes of a particular image to be carved in wax (Reeves 1962: 114, Gangoly 1978). Since the wax melted away each bronze was hence apparently a unique product of the craftsman’s imagination. There were also dhyanaslokas pertaining to each type of deity to visualise the qualities and attributes, associated myths and symbolism and these were recited and mentally invoked before executing the image (Rathnasabhapathy 1982). Hence, according to Reeves (1962: 115), it was by a process of dhyana-yoga defined by Coomaraswamy as ‘visual contemplative union and realisation of formal identity with an inwardly known image’, that the master craftsmen modelled images in wax.

![]()

Radhakrishna Sthapati of Swamimalai

making a wax model of a Nataraja bronze

photographed in 2003

E. B. Havell, writing perceptively in 1908 inIndian Sculpture and Painting (as cited in Coomaraswamy 1989: 183) seems to have witnessed something of the deep intellectual and spiritual tradition which must have informed the high craftsmanship of antiquity, commenting that ‘even at the present day the Indian craftsman, deeply versed in his Silpa Sastras, learned in folk-lore and in national epic literature is, though, excluded from Indian universities – or rather, on that account – far more highly cultured, intellectually and spiritually, than the average Indian graduate. In medieval times the craftsman’s intellectual influence, being creative and not merely assimilative, was at least as great as that of the priest and bookman’. Figure 1 shows the traditional master craftsman Radhakrishna Stapathy of Swamimalai, carving a wax model of a Nataraja image, which also movingly captures something of this inner meditative and contemplative spirit that underpinned the great artistic traditions of South Asian antiquity. While the preservation of crafts traditions themselves remains a challenge in the present day notwithstanding the very laudable and far reaching efforts of the Crafts Councils in India, what also remains a matter of concern is the decline in artistic standards due to the loss of the traditional aesthetic and philosophical milieu within which the crafts functioned.

The solid lost wax image casting process is still followed by traditional icon makers known asSthapatis such as at Devasenasthapati’s workshop in Swamimalai. Here, the image is made from a solid piece of wax, then covered with three layers of clay made from alluvial clay from the Kaveri to make a mould, which is then heated so that the wax is melted out and finally the molten metal is poured into the mould which solidifies into the cavity in the form of the image. The odiolai or coconut palm leaf is used to mark out the tala measurements for the dimensions of the icon. Although realistic portraiture was not common, it seems that bronzes representing important personalities were made now and then even if they were not physical portraits. For example an inscription of Rajendra I, mentions offerings for worship made to the images of the Chola queen Sembiyan Mahadevi who was a great patroness of temples and bronzes (Balasubrahmanyam 1971: 182). It is thought that the Devi at the Smithsonian Institution’s Freer Gallery may represent the widowed queen’s portrait due to the simple yet regal bearing (Dehejia 1990: 36-8, Srinivasan 2001).

Analysis of bronzes and the enigmatic panchaloha composition of icons

South Indian metal icons are often described as panchaloha or icons made of five metals in colloquial terms. South Indian Chola inscriptions themselves only refer to cepputtirumeni or copper images (Nagaswamy 1988: 146-7). The mystique of panchaloha is captured in Parker’s (1992) quote of a traditional sthapati in Tamil Nadu that ‘Panchaloham as a material has the second greatest sakti or power, after the material stone used for the mulamurti, followed by wood and last of all cutai (brick and mortar)’. The Caraka Samhita of the 2nd or 3rd century CE speaks of the ‘pouring of the five metals of gold, silver, copper, tin and lead into various wax-moulds’ (Von Schroeder 1981: 17).

During the course of my doctoral thesis, I technically analysed 130 important South Indian metal icons from the early historic to late medieval periods sampled from collections including Government Museum, Madras or Chennai, Victoria and Albert Museum, and British Museum, London using multi-element spectro-chemical compositional analysis and lead isotope analysis (Srinivasan 1996). The results show that some 80% of the sampled images were leaded bronzes and the rest leaded brasses, so that there is no significant alloying of five metals.

However the Swamimalai sthapati interviewed in 1990 mentioned that the images are known aspanchaloha icons because in addition to three metals of copper, lead and zinc or tin, very minor amounts of silver and gold were added more as a shastra or ritual. Analyses support the notion of the addition of traces of gold and silver to some medieval images (Srinivasan 1999). We commissioned and documented the making of a panchaloha icon in 1990. About 100 mg. of gold and silver was melted in a ladle by the artisans. My husband Digvijay was invited to pour the gold and silver into the crucible together with the sthapati before casting as it is considered auspicious. In this light, it is interesting to note also some of Coomaraswamy’s (1951: 205) observations related to five-metalled alloys of ‘pas-lo’ which he mentions in the context of Sri Lanka was used too make ‘certain small articles such as nails used in superstitious ceremonies’. This suggests too that this alloy if it was used had more of a ceremonial or ritualistic purpose than practical utility.

From about the 8th century AD large solid castings up to 1 metre high began to be made in the region of Tamil Nadu with images such as the Nataraja images of Siva as cosmic dancer (Fig 2) weighing up to 200 kg. From the author’s analyses it seems that some 80% of 130 south Indian images from the early historic to late medieval period were leaded bronzes with tin contents up to 15%, at the limit of solid solubility of tin in copper, with lead up to 25%. The rest were leaded brasses with up to 25% zinc. None of these images had tin exceeding 15%, which is the limit of solid solubility of tin in copper. This ensured that the bronzes were solid, as cast bronzes with a tin content of over 15% are breakable. The average tin content in icons of the Chola period (c. 850-1070 A.D) was the highest at around seven percent. The tin content was less in later Chola and Vijayanagara and Nayaka bronzes. Lead isotope analysis of an early historic zinc ingot with a Brahmi inscription suggests an attribution to the Andhra region and it also matched a votive brass lamp with 14% zinc from the Andhra Krishna valley region. The highest average amounts of zinc were found in the bronzes of the later Chalukya period of 2.5 percent. Fig 2 shows a Nataraja bronze from Kankoduvanithavam with 8 percent tin and 8 percent lead and finger-printed to about the mid 11th century. Fig. 3 is a microstructure of a 13th century South Indian image of leaded bronze studied by the author at the Institute of Archaeology, London.

The mastery of solid cast bronze casting by South Indian and also Sri Lankan sculptors is something remarkable in the history of art. As implied by materials scientist V.S. Arunachalam (Nehru Centre lecture, 1993) in the title of his lectures ‘From Temples to Turbines’, the modern technology of investment casting used to make turbines has an illustrious history rooted in the subcontinent’s sacred past. Indeed, Chola bronzes bring together metallurgy and aesthetics, and the sensuous and the sacred in a remarkable fashion (Srinivasan and Ranganathan 2006).

Interpretations of the Nataraja and insights on dating from technical studies and questions about the ‘cosmic’ dimension

![]()

Nataraja bronze,c 1050 CE,

from Kankoduvanithavam in Government

Museum, Chennai

As reported in the author’s doctoral thesis and papers (Srinivasan 1996, 1999, 2004), 130 representative south Indian metal icons from museums including the Government Museum, Chennai, Victoria and Albert Museum, London and British Museum, London were compositionally analysed for 18 elements, and sixty of these images were analysed for lead isotope ratios. The lead isotope ratios and trace elements of a control group of images were calibrated against the stylistic and inscriptional evidence to yield characteristic finger-prints for different groups of images as Pre-Pallava (c. 200-600 C.E) [8], Pallava (c. 600-875 C.E) [17], Vijayalaya Chola (c. 850-1070 C.E) [31], Early Chalukya-Chola (c. 1070-1125 C.E) [12], Later Chalukya-Chola (c. 1125-1279 C.E) [17], Later Pandya (c. 1279-1336 C.E) [15], Vijayanagara and Early Nayaka (c. 1336-1565 C.E) [20] and Later Nayaka and Maratha (c. 1565-1800 C.E) [12]. Using these calibrations, images of uncertain attributions could be stylistically re-assessed (Srinivasan 1996).

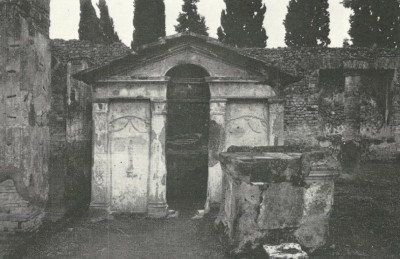

This exercise of archaeometallurgical finger-printing suggested that the classic Nataraja metal icon of Siva dancing with an extended right leg in bhujangatrasita karana originated in the Pallava period (c. 800-850 C.E.) rather than the 10th century Chola period (Srinivasan 2001, Srinivasan 2004). Two Nataraja images, one from the British Museum and one from the Government Museum, Chennai which were thought to have been of the Chola period, had lead isotope ratio and trace element finger-prints that better matched the Pallava group. No Nataraja bronzes could be identified datable to the Vijayanagara period (c 14th-16th century) which was predominantly a Vaishnava dynasty. It is generally thought that stone Nataraja images in the round come more into prominence during the patronage of Queen Sembiyan Mahadevi (c. 940 CE) at temples such as Kailasanathaswami. However, the studies mentioned before suggest that bronze Nataraja images may have preceded stone ones. Bennink et al. (2012) have pointed to free standing stone Nataraja images with consort Sivakami or Parvati akin to the bronze forms represented in Chola utsava murtis which may have copied the bronze versions.

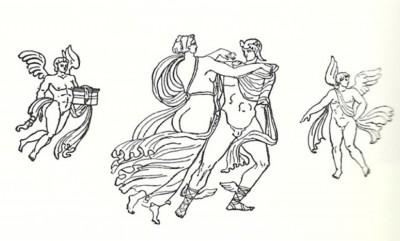

Citing the 13th century Tamil text Unmai Vilakkam (verse 36) thought to have been composed around Chidambaram, Coomaraswamy (1912: 87) explained the significance of the dance as ‘Creation arises from the drum: protection proceeds from the hand of hope; from fire proceeds destruction: the foot held aloft gives release’. He added that the dance represented the five activities (pancakritya) of Shrishti (creation), Sthiti (preservation), Samhara (destruction),Tirobhava (illusion), and Anugraha (salvation). As such, we may note that Coomaraswamy does not in his own essay actually use the term ‘Cosmic Dance of Siva’, the phrase by which the Nataraja is often popularly described the world over at various museums, although he does mention that the above ‘cosmic activity is the central motif of the dance’. Furthermore, although Coomarawasmy (ibid.) mentions the ‘tandava’ mode of dance of Shiva performed in cemeteries and burning grounds, he does not in his essay actually use the term ‘ananda-tandava’. As mentioned in Zvelebil (1985: 2) it was K.V. Soundara Rajan who vigorously highlighted the identification of the Nataraja bronze with the extended leg with the ‘ananda-tandava’ murti or ‘awesome dance of bliss’, while Zvelebil (ibid.) opines that the word ‘tantu’ is derived from the Tamil/Dravidian word for leaping over.

Some of the problems in only relying on Coomaraswamy’s metaphysical interpretations of the Nataraja bronze which seem to have been based on later 13th century texts were highlighted by various scholars. As Zvelebil (1998:8) put it insightfully, both in praise and criticism, that the essay ‘quotes in somewhat haphazard fashion a number of Tamil texts without much respect for their dating and historical sequence’, adding that ‘the essay is beautiful and has contributed in a very important manner to Western understanding of Indian art..’. In a thought provoking paper Padma Kaimal (1999) suggests alternate shades of meaning to the Shiva Nataraja bronze, somewhat removed from Coomaraswamy’s mystical approach. She argues that the cult of Nataraja may have been strategically propagated by the Imperial Cholas due to the martial implications associated with the dance of destruction, as a symbol of power and their expansionist agenda. Indeed, many early Tamil hymns also invoke Nataraja as the dark lord wandering around cremation grounds. In a similar vein, it is no doubt pertinent to query the extent to which there really had been a ‘cosmic’ dimension associated with the actual visualization of the icon by its makers.

Nevertheless, this author would like to reiterate that the comment of Zvelebil (1985: 8 ) that Coomaraswamy had ‘…with tremendous intuition…foreseen the results of later research’ has a ring of truth in that the ‘cosmic’ dimensions that his writings hinted at, cannot be dismissed as being totally removed from the subtext of the conceptualization of this bronze. The author has thus argued that the dating of the Nataraja bronze to the Pallava period based on the technical finger-printing evidence (Srinivasan 2004), predating the Chola period, raises new possibilities of making connections with some of the mystical references to be found in the writings of Tamil poet saints from the 7th-9th century, suggesting a nascent ‘cosmic’ comprehension.

The temple of Chidambaram dated to the 12th-13th century, is the only shrine where the Nataraja metal icon of dancing Siva is worshipped in the inner sanctum or garbhagriha in place of the aniconic lingam or cosmic pillar (Younger 1995). In all other Siva temples elsewhere in Tamil Nadu, metal Nataraja icons are only processional images for festivals or the utsava murti. Within the Chidambaram temple, the Nataraja image is worshipped inside the golden roofed structure called the ‘chit sabha’, i.e. ‘hall of consciousness’. Exploring the etymology of the word Chidambaram itself, one of its meanings could be as follows: chit translates as the consciousness and ambaram the cosmos, so in that sense Chidambaram itself could signify the cosmic consciousness. In a hymn to Nataraja ‘Kunchitanghrim bhaje’ composed by the 13th Tamil poet Umapati Sivacarya of Chidambaram (Smith 1998: 21), Siva as Nataraja performs theanandatandava or dance of bliss and is also described as sacchidananda or the one whose mind or consciousness is in a state of the dance of blissful equilibrium. The ‘Chidambaram Rahasya’ or secret of Chidambaram relates to the worship of Nataraja also in the form of ‘akasa’ or the element sky or ether. Sivaramamurti (1974: 147) mentions that the Sanskrit Vadnagar Prasasti of Kumarapala describes Siva as playing with crystal balls as if they were newly created planets.

At the same time, there are already references in the pre-Sanskritic poetic corpus of devotional poetry to Nataraja worshipped at Tillai (the old name for Chidambaram) by Tamil saints such as Manikavachakar and Appar using the Tamil words of ‘unarve’ (consciousness) and ‘nilavu’ (sky). This suggests that such ‘abstract’ notions need not have been later Sanskritised introductions but could have also formed a part of the general ways in the icon was understood in this earlier period from about the 7th-9th century when so much of the Tamil devotional poetry related to the icon was actually compiled.

For example, a verse by Manikavachakar goes, ‘He who creates, protects, and destroys the verdant world…’ (Mowry 1983: 53). Another verse by Manikavachakar cited in Yocum (1983: 20) describes Nataraja as ‘Him who is fire, water, wind, earth and ether’. Yet another 9th century verse by Manikkavachakar (Yocum 1983: 24) cited below already suggests a mystical comprehension of the Nataraja bronze in terms of ‘consciousness’ as suggested by the Tamil word (unarve), preceding the use of the Sanskritic term chit as consciousness.:

O unique consciousness (or unarve),

which is realised (unarvatu) as standing firm,

transcending words and (ordinary) consciousness (unarvu),

O let me know a way to tell of You. (22:3)

A ‘cosmic’ sense of nature mysticism also permeates a Tamil verse to Nataraja composed by the 7th century saint Appar (Handelman and Shulman 2004), referring to sky as the Tamil ‘nilavu’, prior to 12th-13th century usage of the Sanskrit ‘akasa’:

The Lord of the Little Chamber,

filled with honey,

will fill me with sky (nilavu)

and make me be. [5.1.5]

In Srinivasan (2011) the author has also suggested that this ‘cosmic’ sensibility may also hark back to the nature imagery that pervades the earlier classical Tamil Sangam poetic tradition with its sense of traversing from the inner space (akam) to the outer space (puram). This sensibility is captured in A.K. Ramanujan’s fine commentaries on early Sangam poetry, himself an exceptional scholar-literateur who in this author’s opinion evokes something of the linguistic finesse of Coomarasamy’s academic prose. For example, the following verse from A. K. Ramanujan’s translation (1980: 108-9) conveys the creative tension generated by the juxtaposition of akamwith puram genres, of outer with inner space:

‘Bigger than earth, certainly,

higher than the sky,

more unfathomable than the waters

is this love for this man…’

In this context too, Coomaraswamy’s writings pointing to such ‘cosmic’ elements have resonance, such as the following verse he sites from Tirukuttu Darsharna (‘Vision of the sacred dance’) from Tirumular’s Tirumantiram, ‘He dances with water, fire, wind and ether, his body is Akash, the dark cloud therein is Muyalaka (the dwarf demon below Siva’s foot)’. Dates for Tirumular vary from the 8th century to as late as the 11th-12th century.

Finally, the author would also like to allude to preliminary archaeoastronomical studies made by her with late astrophysicist Nirupama Raghavan which point to the connections of the Nataraja imagery with the star positions in and around the Orion constellation and the possible inspiration also drawn in aspects of Nataraja worship from a postulated sighting of the 1054 supernova explosion (Srinivasan 2006). Although these are preliminary findings, there is some tentative evidence in the worship of the Nataraja in a chariot processional festival Chidambaram in the month of Margazhi around December known as Tiruvadurai. The ardra tandava darshanam at Chidambaram is related to the sighting of ardra or the reddish star Betelguese in the constellation Orion who is associated with Nataraja. The constellation of Orion appears at the zenith at this time of the year and as witnessed also by the author, some of the star positions and Orion seem to broadly correlate with some of the body parts of Siva Nataraja, for example the Orion belt falls along his belt and the lifted leg pointing towards Syrius. A Tamil text by A. Cokkalinkam identified by the late Raja Deekshitar (pers. comm.) of Chidambaram showed some of the star positions of Orion around the Nataraja bronze entitled ‘ardra tandava darsanam’. This implies the sighting of the tandava dance performed by Shiva Nataraja as ardra or arudra, the wrathful one, hence associated with the reddish star Betelguese.

The above paper summarises some of the new trends or insights that art historical studies combined with archaeometallurgical, ethnoarchaeological, crafts documentation and archaeoastronomical studies yields in terms of an understanding of the enigmatic Nataraja bronze and the milieu of south Indian and South Asian bronzes. The ground breaking legacy of Coomaraswamy in contributing to this overall understanding is highlighted.

(This article was earlier published in Asian Art and Culture: A Research Volume in Honour of Ananda Coomaraswamy, Kelaniya: Centre for Asian Studies, pp. 245-256)

(Professor Sharada Srinivasan, of the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore, works in the areas of archaeological sciences, archaeometallurgy, art history and performance studies. A PhD in archaeometallurgy, Institute of Archaeology, University College, London, she is a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain, and the World Academy of Art and Science. As an exponent of Bharatanatyam she has given several lecture-demonstrations including one at the Royal Academy of Arts, London, for their exhibition ‘Chola: Sacred Bronzes from Southern India’ (2007))

Balasubrahmanyam, S. R. 1971. Early Chola temples Parantaka I to Rajaraja I (A.D. 907-985). New Delhi: Orient Longman.

Capra, F. 1976. The Tao of Physics: An Exploration of the Parallels between Modern Physics and Eastern Mysticism. London: Fontana, p. 258.

Coomaraswamy, A. K., 1909, The Indian craftsmen, New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd.

Coomaraswamy, A.K. 1956. Mediaeval Sinhalese Art. New York.

Dehejia, V. 1990. Art of the Imperial Cholas. New York: Columbia University Press.

Gangoly, O.C., 1978, South Indian Bronzes, Calcutta.

Glansdorff, A. and Prigogine, I. 1971. Thermodynamic theory of structure, stability and fluctuations. New York: Wiley-Interscience.

Handelman, D. and Shulman, D. 2004. Siva in the Forest of Pines: An Essay on Sorcery and Self-Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kaimal, P. 1999. Shiva Nataraja: Shifting meanings of an icon, Art Bulletin, Vol. LXXXI, 3, 390-420.

Mowry, L. “The theory of the phenomenal world in Manikkavachakar’s Tiruvachakam”. In: Clothey, F. and Long. B. (eds.). Experiencing Siva: Encounters with a Hindu Deity. New Delhi: Manohar Publications, pp. 37-59.

Oldmeadow, H. 2004, Journeys East: 20th century western encounters with eastern religious traditions, Bloomington: World Wisdom.

Parker, S. 1992. The matter of value inside and out: aesthetic categories in contemporary Hindu temple arts. Ars Orientalis 22: 98-109.

Ramanujan, A.K. 1980, The Interior Landscape: Love poems from a classical Tamil Anthology, Clarion Books.

Rangarajan, A. 1992. ‘A confluence of East and West: Ananda Coomaraswamy’.

Reeves, R. 1962. Cire Perdue Casting in India. New Delhi: Crafts Museum.

Rodin, A, ‘La Danse de Siva’, Ars Asiatica, 3:7-13.

Sivaramamurti, C. 1963, South Indian Bronzes, New Delhi: Lalit Kala Academy.

Sivaramamurti, C. 1974. Nataraja in Art, Thought and Literature. New Delhi: National Museum

Smith, D. 1998. The Dance of Siva: Religion, Art and Poetry in South India. Cambridge: University Press

Srinivasan, S. 1996. The enigma of the dancing ‘pancha-loha’ (five-metalled) icons: archaeometallurgical and art historical investigations of south Indian bronzes. Unpublished Phd. Thesis. Institute of Archaeology, University of London.

Srinivasan, S. 1999. Lead isotope and trace element analysis in the study of over a hundred south Indian metal icons. Archaeometry 41(1).

Srinivasan, S. 2001. ‘Dating the Nataraja dance icon: Technical insights’. Marg-A Magazine of the Arts, 52(4): 54-69.

Srinivasan, S. 2004. ‘Siva as cosmic dancer: On Pallava origins for the Nataraja bronze’. World Archaeology. Vol. 36(3): 432-450. Special Issue on ‘Archaeology of Hinduism.

Srinivasan, S. 2006. ‘Art and Science of Chola Bronzes’. Orientations, 37 (8): 46-55.

Srinivasan, S. and Ranganathan, S. 2006, ‘Nonferrous materials heritage of mankind,’ Transactions of Indian Institute of Metals, Vol. 59, 6, pp. 829-846.

Srinivasan, S. 2010, ‘Cosmic inspiration & art in relation to dancing Shiva Nataraja bronze’, Published abstract, INSAP VII, (Seventh international conference on inspiration from astronomical phenomena), Bath Royal Literary and Scientific Institution.

Srinivasan, S. 2011, ‘Nataraja and Cosmic Space: Nature and Culture intertwinings in the early Tamil tradition’, In Nature and Culture, ed. R. Narasimha, History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in Indian Civilization, PHISPC Series and Centre for Studies in Civilisation, pp. 271-291.

Von Schroeder, U. 1981. Indo-Tibetan Bronzes. Hong Kong: Visual Dharma.

Younger, P. 1995. ‘The Home of Dancing Sivan: Traditions of the Hindu Temple in Citamparam’, Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 112.

Zvelebil, K., 1985, Ananda-Tandava of Siva-Sadanrttamurti, Institute of Asian Studies, Madras.

Logo of the Rione.

Logo of the Rione.

Map of the archaeological complex: Largo di Torre Argentina, Rome, Italy

Map of the archaeological complex: Largo di Torre Argentina, Rome, Italy

_-2.jpg)

This temple was built for the Egyptian merchants. It was located on the Commercial Agora near the western gate. There is also another entrance into the temple from the south-west corner of the Agora through stairs.

This temple was built for the Egyptian merchants. It was located on the Commercial Agora near the western gate. There is also another entrance into the temple from the south-west corner of the Agora through stairs.

Technical information

Technical information

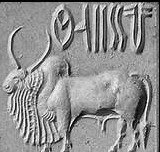

Marduk, winged, holding the pine-cone. Bracelet has safflower hieroglyph. Annunaki, Sumerian.

Marduk, winged, holding the pine-cone. Bracelet has safflower hieroglyph. Annunaki, Sumerian. Pine cones helod by eagle-divinities flanking tree of life. The divinities also hold wallets.

Pine cones helod by eagle-divinities flanking tree of life. The divinities also hold wallets.

A pair of eagle-headed Annunak flanking a staff capped with a pine-cone.

A pair of eagle-headed Annunak flanking a staff capped with a pine-cone.

What is described as a “pinecone” at the small museum at Arbeia (South Shields, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne, U.K.), which was found in Romano-British context.

What is described as a “pinecone” at the small museum at Arbeia (South Shields, near Newcastle-upon-Tyne, U.K.), which was found in Romano-British context.

Roman

Roman

Samarra bowl.

Samarra bowl.

Vikas Swarup

Vikas Swarup

Bronze statue. Sanxingdui in Guanghan, Sichuan Province ca 1200 BCE. 262 cm. tall.Sanxingdui Museum.

Bronze statue. Sanxingdui in Guanghan, Sichuan Province ca 1200 BCE. 262 cm. tall.Sanxingdui Museum.

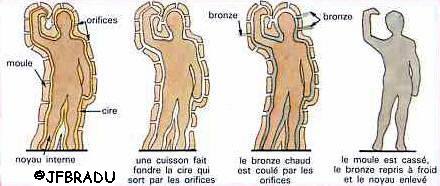

Cire perdue.

Cire perdue.  Cire perdue.

Cire perdue. Bronze deity oil lamp, pre-1900

Bronze deity oil lamp, pre-1900

Présentation des étapes de réalisation d’une pièce en bronze dans un moule réalisé via la méthode de la cire perdue.

Présentation des étapes de réalisation d’une pièce en bronze dans un moule réalisé via la méthode de la cire perdue.

Fillet worn on the forehead of a person with a neat hair-style and a hair-bun. 40. Head (back), Mohenjo-daro

Fillet worn on the forehead of a person with a neat hair-style and a hair-bun. 40. Head (back), Mohenjo-daro

Crete. Cow-head rhython with trefoil decor.

Crete. Cow-head rhython with trefoil decor.

D

D

http://indiafacts.co.in/something-awry-in-iit-madras-the-full-story/

there is no point is castigating these guys; we need to do two things:

1- emasculate the agenda of the evangelicals and foreign govts

2- re-evaluate the true sense of alienation by the disadvantaged indians as a whole so that they are not available for hire

modi seems to have the right plan to address both, but he must stay the course - and hasten

What is more disgusting is about the fake photos shown by News Papers.

Gullible students specially who are brilliant i,e who need less effort to prepare for a subject are the most disillusioned lot. These are the ones who were Che-Guivera t-shirts and with the drop of a hat start protesting against anything under the sun. They will encourage other students to take part in politics forgetting about their studies, but they themselves will leave for US for higher studies. I have seen these happen to my batchmates. The che-guiveras on one hand criticizes how US and capitalist MNC are the root cause of all evils but they are the one who goes to US and joins MNCs with high salary. Enemies of India knows that India has one of the best intellectual capital that can be nurtured in universities and colleges for Indias development, so what they do is they corrupt the atmosphere where these intellecttuals can further develop their skills.

I request Ajit Doval to put spies as student in famous govt colleges and monitor the anti-india activities. I am sure just like scams in NGOs there will be numerous scam in student unions.Most senior CPM leaders used to be active in students politics in colleges.

I dont block people for differing.. I block them for either ranting or mass-tagging.. Your grievance has no logic. Me blocking you has no connection with a Public account like PMOIndia blocking me.. If you cant tell the difference.. Im glad I blocked you.. So stop whining on my page... I usually dont even respond to criticism because people are entitled to their views.. You are blocked because of your hatred... Stick with that..

arnab leafs the pack as a jobless old mam woman to gossip on prime time tv and instigate one and all against go

vt

arnab leafs the pack as a jobless old mam woman to gossip on prime time tv and instigate one and all against go

vt

Most interesting was the moderator who let it slip rather quietly that free speech means the freedom to talk ill of and abuse someone whom you don’t agree with and not one panelist even raised an eyebrow about that!. There were even some non hindu panelists and I am quite sure they understood the real meaning of the word “someone” in that statement i.e., someone = hindus ! If the same discussion had happened in the 60s when Periyar was calling the shots that statement would have surely had an additional phrase “to attack,kill, desecrate or rape” and there would have been applause all round. Thank God we are a few decades past those days and there seems to be some faint light visible at the end of the tunnel.

Many thanks to people like you Ravi.

Our culture can only progress when we identify bigots such as Commie-Chrislamists and their media supporters & punish them. In the current scenario, country needs to have a strong Media Regulating body defining do & don'ts for MSM.

1. There should be a ban on mainstream social media particularly digital media for one year (or more) to get rid of/ wash out present genre of journalists/ anchors/ editors. Let's live with DD !

2. Govt & Judiciary should form a constitutional Regulatory body on reporting and panel discussion keeping National, social, cultural and humanitarian aspects in view, within 6 to 9 months.

3. The proposed ban shall be lifted after the Regulatory body is formed completely and settles down with needed guidelines in place (to sink into the public (at least 3 months) for reconciliation of penalties for all deviations).

4. During the time of ban, Newspapers and social media can dispense the requirements of information dissemination.

Namaste!

I need your help. You and I have the same aim.

I have started a new blog to expose Dynastycrooks. Everyday I choose 1 Dynastycrook to expose. Today I have written about Dynastycrook Mihir Sharma and his "samosa ban"

https://dynastycrooks.wordpress.com/2015/06/04/dynastycrook-mihir-sharma-and-the-samosa-ban/

Tomorrow, I will write about Dynastycrook Sagarika aunty. Please help me spread the word and expose more dynastycrooks.

It is amazing how it is ok to abuse the perceived "advantaged" class of people. But any retaliation by them is termed as racist, bigoted, fascist. So, a high caste, rich Hindu male from the IIT be damned. He can be abused to any extent and he has no right to retaliate.

The handout culture introduced by Commies has bred a whole bunch of nincompoops feeling entitled and acting victims while being extremely abusive. Hope IITM throws such hooligans out as do other institutions of repute!