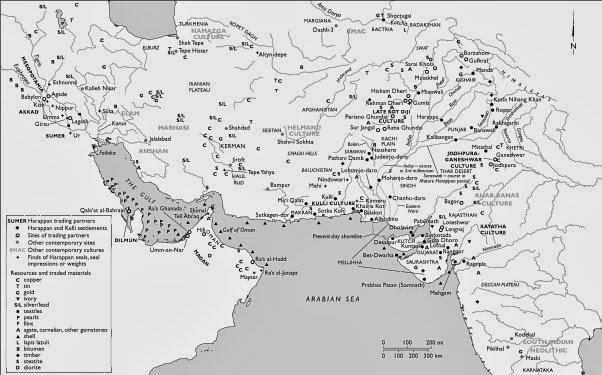

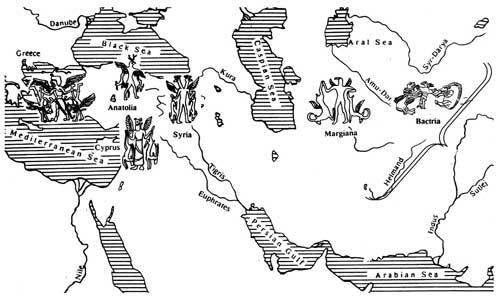

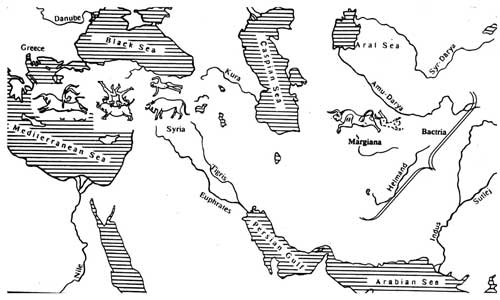

From Hanoi-Malacca (Malakka) to Meluhha, from Meluhha to Mari-Haifa, the speech area (sprachbund) from 5th millennium BCE was Meluhha. The areas identified as Bronze-Age sites and of Austro-Asiatic speakers attest to this sprachbund since the major wealth-creating activity involved tin trade of the Tin-Bronze Revolution from 5th millennium BCE, from the Tin Belt of the Globe in the Himalayan river basins of Mekong, Irrawaddy and Salween through Brahmaputra, Ganga-Yamuna-Sarasvati-Persian Gulf, complementing the Indian Ocean Maritime Route.

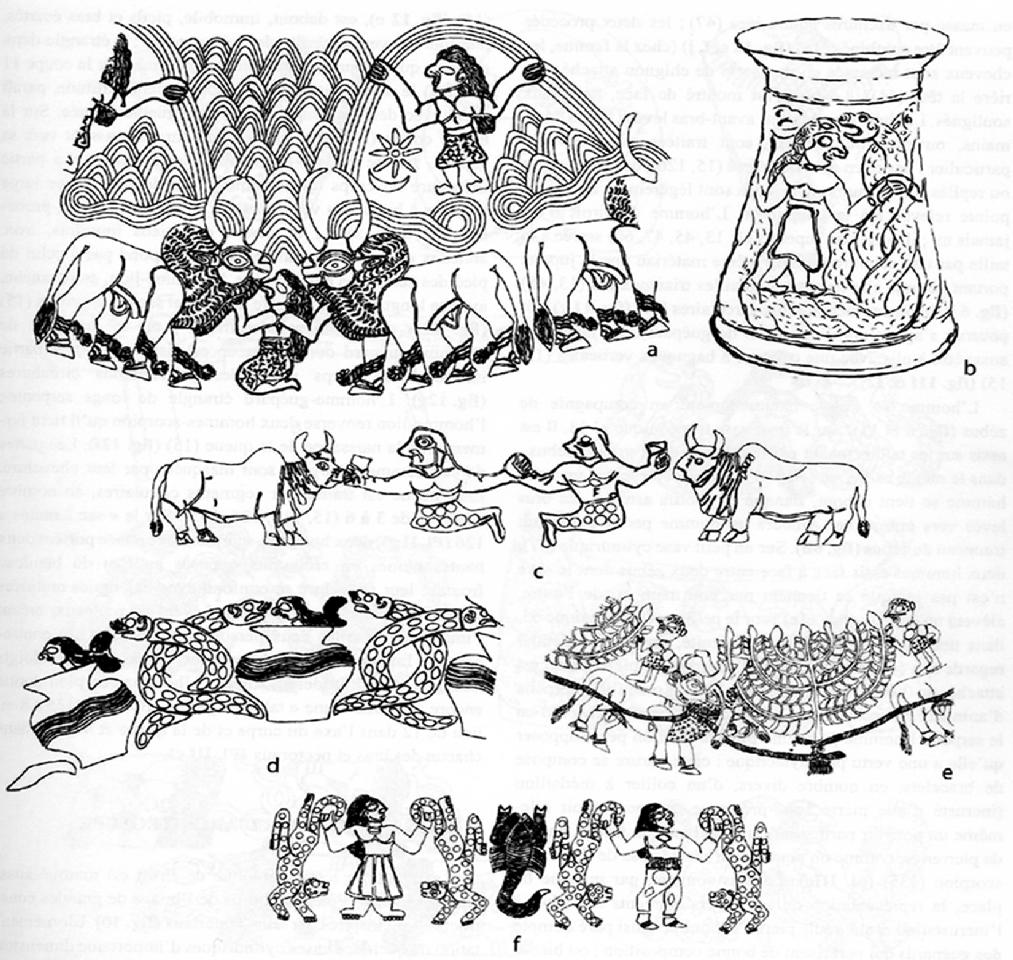

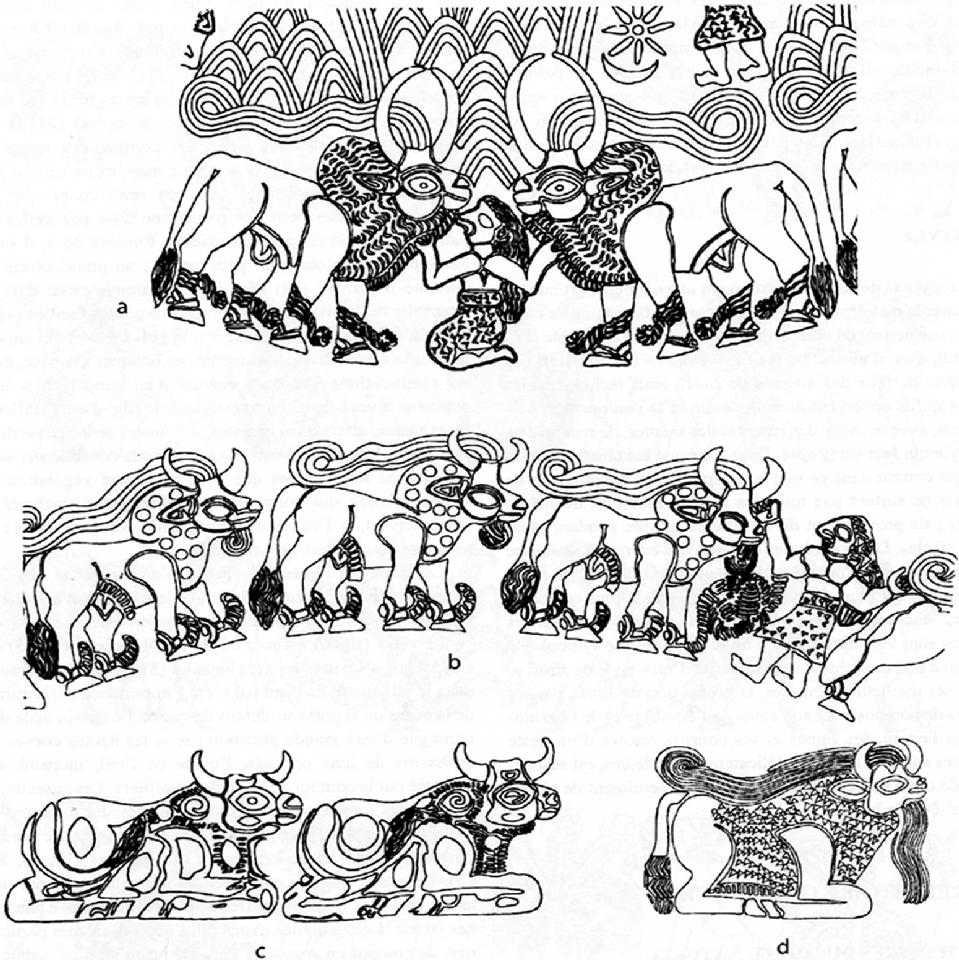

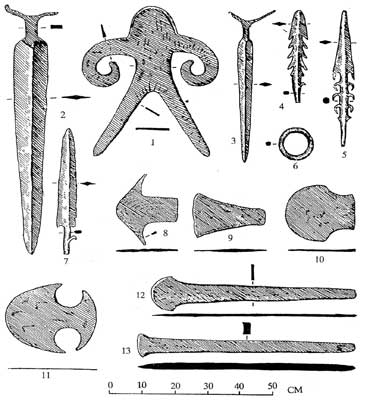

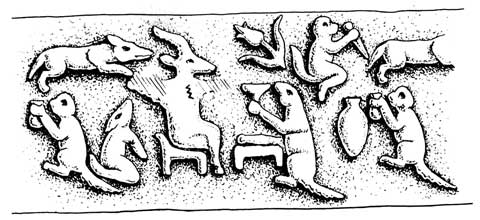

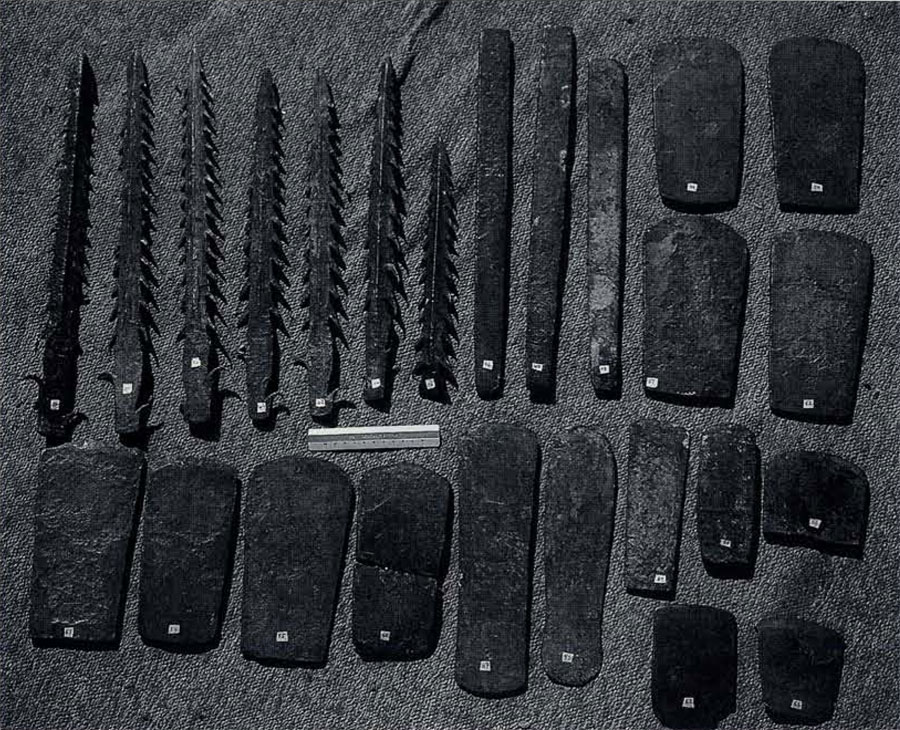

This monograph presents images of artifacts with Indus Script hypertexts which signify wealth-accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues. These include:

खरडा kharaḍā 'A leopard' (cheetah) Rebus: karaḍā 'hard metal alloy'

पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'zebu, bos indicus taurus' rebus: पोळा [ pōḷā ] 'magnetite, ferrite ore: Fe3O4'.

seṇa 'falcon' śyena, anzu 'eagle', aśáni 'thunderbolt' rebusآهن ګر āhan gar, 'blacksmith

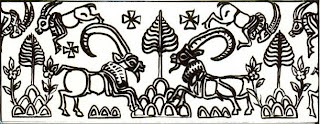

miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati) Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic languages)

arye 'lion' rebus: ara 'brass'

kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'

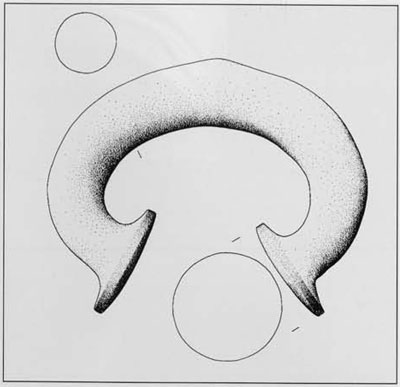

फड 'cobra hood' (फडनीस phaḍanīsa 'scribe' of फड 'metals manufactory'

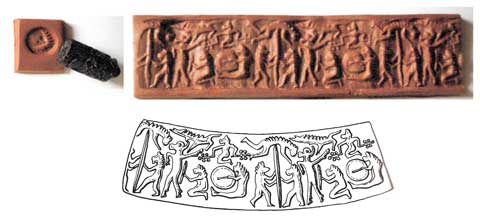

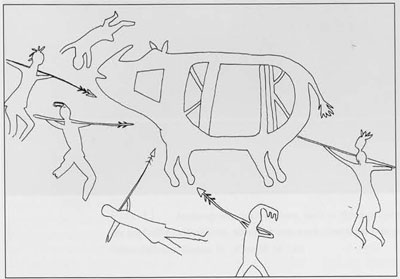

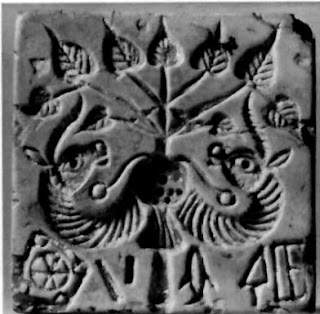

Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820 कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa, 'cattlepen', 'young bull',Rebus: kõdār 'turner' (Bengali). konda 'furnace, fire-altar' kō̃da कोँद 'furnace for smelting': kõdā 'to turn in a lathe' (B.) कोंद kōnda. 'engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems' (Marathi) kundaṇa 'fine gold'

karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

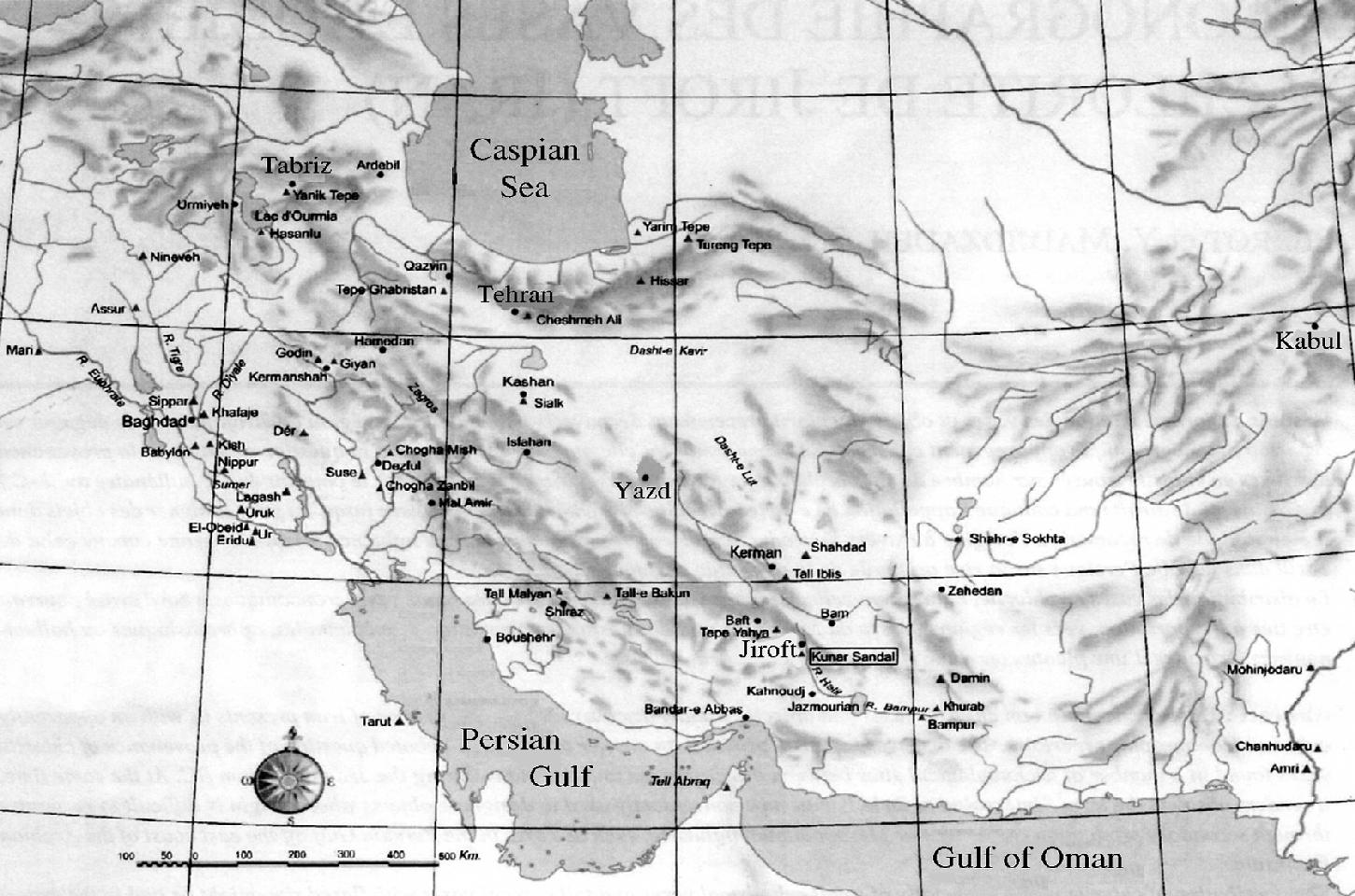

![Image result for ziggurat jiroft]() The ziggurat of Jiroft (Konar Sandal) is an echo of the Mohenjo-daro Stupa also enshrined on the tiered structures of Sit-Shamshi Bronze (Louvre).Sit-Shamshi bronze is a veneration of the morning Sun. शुष्मः 'sun' (Skt.) cognate Shamash (Akkadian), Sun divinity. A word cognate with shamas, 'sun' (Akkadian) is शुष्णः śuṣṇḥशुष्णः [शुष्-नः कित् Uṇ.3.12] 1 The sun.-2 Fire.-शुष्मः śuṣmḥ शुष्मः [शुष्-मन् किच्च] 1 The sun. -2 Fire. शाश्वत 'heaven , ether' (Samskr̥tam). शुष्मः for शुष्ण Pa1n2. 3-1 , 85 Sch. m. the sun

The ziggurat of Jiroft (Konar Sandal) is an echo of the Mohenjo-daro Stupa also enshrined on the tiered structures of Sit-Shamshi Bronze (Louvre).Sit-Shamshi bronze is a veneration of the morning Sun. शुष्मः 'sun' (Skt.) cognate Shamash (Akkadian), Sun divinity. A word cognate with shamas, 'sun' (Akkadian) is शुष्णः śuṣṇḥशुष्णः [शुष्-नः कित् Uṇ.3.12] 1 The sun.-2 Fire.-शुष्मः śuṣmḥ शुष्मः [शुष्-मन् किच्च] 1 The sun. -2 Fire. शाश्वत 'heaven , ether' (Samskr̥tam). शुष्मः for शुष्ण Pa1n2. 3-1 , 85 Sch. m. the sunAratta is a land that appears in Vedas(B.S 2.13.14) - It is a fabulously wealthy place full of gold, silver, lapis lazuli and other precious materials, as well as the artisans to craft them.

- It is remote and difficult to reach.

- It is home to the goddess Inana, who transfers her allegiance from Aratta to Uruk.

- It is conquered by Enmerkar of Uruk. Writers in other fields have continued to hypothesize Aratta locations. A "possible reflex" has been suggested in Sanskrit Āraṭṭa or Arāṭṭa mentioned in the Mahabharata and other texts; Alternatively, the name is compared with the toponym Ararat or Urartu. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aratta

Marhaši (Mar-ḫa-šiKI 𒈥𒄩𒅆𒆠, Marhashi, Marhasi, Parhasi, Barhasi; in earlier sources Waraḫše) was a 3rd millennium BC polity situated east of Elam, on the Iranian plateau. It is known from Mesopotamian sources, but its precise location has not been identified, though some scholars link it with Jiroft. Francfort and Tremblay[1] on the basis of the Akkadian textual and archaeological evidence, proposed to identify the kingdom of Marhashi and Ancient Margiana. An inscription attributed to Lugal-Anne-Mundu of Adab (albeit in much later copies) mentions it among the seven provinces of his empire, between the names of Elam and Gutium...Hammurabi of Babylonia's 30th year name was "Year Hammurabi the king, the mighty, the beloved of Marduk, drove away with the supreme power of the great gods the army of Elam who had gathered from the border of Marhashi, Subartu, Gutium, Tupliash (Eshnunna) and Malgium who had come up in multitudes, and having defeated them in one campaign, he (Hammurabi) secured the foundations of Sumer and Akkad." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Marhasi

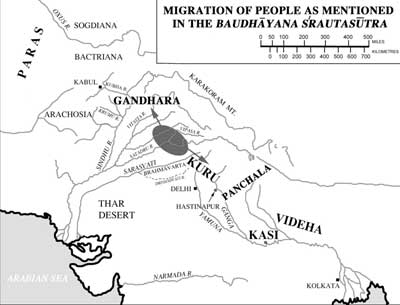

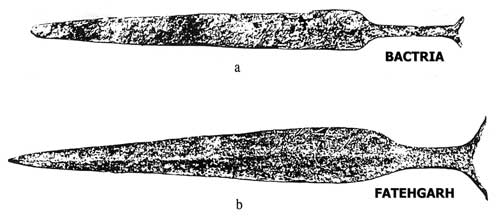

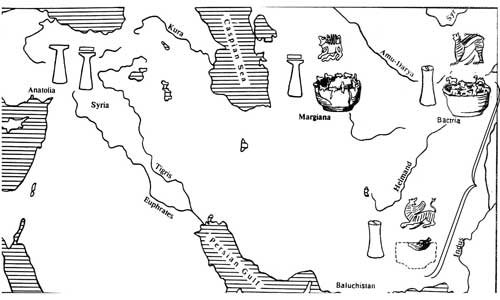

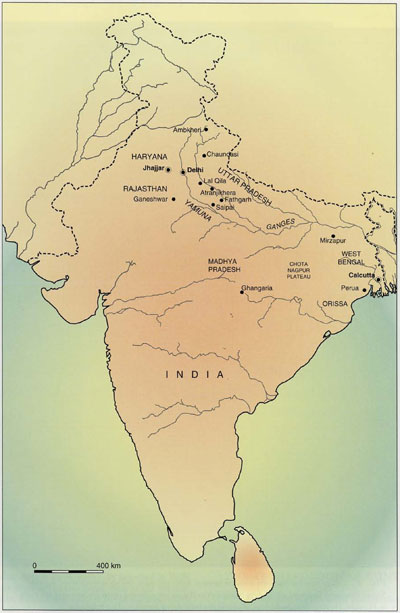

Bronze Age sites of eastern Bha_rata and neighbouring areas: 1. Koldihwa; 2. Khairdih; 3. Chirand; 4. Mahisadal; 5. Pandu Rajar Dhibi; 6. Mehrgarh; 7. Harappa; 8. Mohenjo-daro; 9. Ahar; 10.Kayatha; 11. Navdatoli; 12. Inamgaon; 13. Non Pa Wai; 14. Nong Nor; 15. Ban Na Di and Ban Chiang; 16. Non Nok Tha; 17. Thanh Den; 18. Shizhaishan; 19. Ban Don Ta Phet [After Fig. 8.1 in: Charles Higham, 1996, The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press].

Araṭṭa as Meluhha speech area (sprachbund)

Figure 1. Map of Iran, with Jiroft, Konār Ṣandal, and sites of the 3rd millenium BCE with chlorite vessels. Courtesy of the author. (Jean Perrot)

[quote]

One of the most potentially significant finds reported on the Internet from Konar Sandal—but to the Internet from the “excavations in Jiroft,” “the Jiroft ancient site—”are a number of alleged inscriptions. It remains unclear how many inscriptions exist, where they were excavated, or if any in fact were recovered from one or both of the tepes. The Internet mentions two inscriptions discovered at Konar Sandal in 2005, but no contexts are mentioned. In the same source, Madjidzadeh is quoted as stating that they should be labeled Proto-Iranian, not Proto-Elamite. Further, two other inscriptions are said to have been recovered in a local farmer’s backyard, 300 meters from one of the tepes in 2006, that is, they were not excavated; they measure 18 x 10 cm and 13.5 x 8.5 cm. One Internet-published alleged inscription is on a broken object labeled a brick (20.3 cm) and preserving parts of one and a half lines of indentations. It is proclaimed to be 300 years older than writing from Susa, which signifies to the excavator that the Elamites learned about writing from “Jiroft.” Another is a broken but complete tablet alleged to derive from Konar Sandal B (Basello, 2006; no documentation for the source or size is provided); it consists of five lines of incised geometric indentations. Another alleged inscription (still unpublished but circulating among scholars) consists of four lines of geometric incisions (that look as if freshly incised). Not one of the published (not by Madjidzadeh but on the Internet) tablets and their indentations has any relationship with any known system of writing from any ancient culture (see Covington, 2004, p. 11).

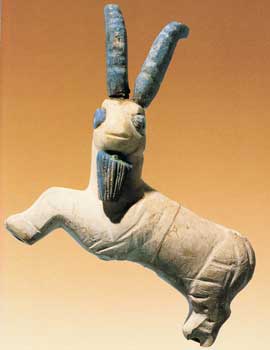

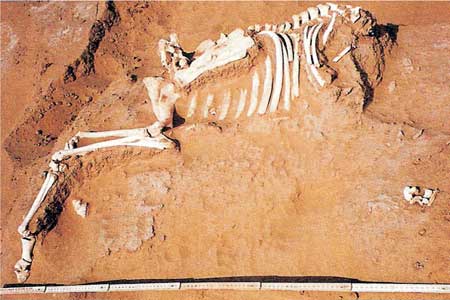

Concomitant with the Konar Sandal tepe excavations, Madjidzadeh (2003b, p. 26) briefly mentioned excavations of several burials at two local cemeteries, Riganbar and Konar Sandal, but with no reference to their specific locations relative to the tepes or what was recovered. Only one has been published as a photograph (ibid., p. 25) that shows pottery vessels; it is a Bronze Age burial. An Internet report recorded that the bronze head of a goat “was found in the historical cemetery of Jiroft,” a site that eludes us.

Such is the situation about the limited extent of archeological knowledge both of the plunder and the excavations at sites south of Jiroft up to 2007.

Bibliography:

Pierre Amiet, review of Madjidzadeh, 2003a, in Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie Orientale 96/1, 2002, pp. 95-96.

Gian Pietro Basello, “The Tablet from Konar Sandal B (Jiroft),” at www. elamit.net, accessed on 7 November 2006.

Richard Covington, “What was Jiroft?” Saudi Aramco World, September/October 2004, pp. 2-11.

Cultural Heritage News Agency, “Discovery of the Main Part of Kenar Sandal’s Ziggurat,” at “Latest Archaeological News from Iran,” http://iranarch.blogspot.com/2006/02 /discovery-of-main-part-of-kenar.html, accessed on 25 February 2006.

Jean Daniel Forest, “La Mésopotamie et les échanges à longue distance aux IV et III millénaires,” Dossiers d’Archeologie, no. 287, October 2003, pp. 126-34.

C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky, “New Centers of Complexity in the Iranian Bronze Age,” The Review of Archaeology, Spring 2004, pp. 5-10.

Andrew Lawler, “Rocking the Cradle,” Smithsonian, May 2004, pp. 41-48.

Yousef Madjidzadeh, Jiroft: The Earliest Oriental Civilization, Tehran, 2003a.

Idem, “La découverte de Jiroft,” Dossiers d’Archeologie, no. 287, October 2003b, pp. 19-26.

Idem, “La premiére campagne de fouilles à Jiroft,” Dossiers d’Archeologie, no. 287, October 2003c, pp. 65-75.

Oscar White Muscarella: “Jiroft and ‘Jiroft-Aratta’,” Bulletin of the Asia Institute 15, 2001 (publ. 2005), pp. 173-98.

Jean Perrot, “L’iconographie de Jiroft,” Dossiers d’Archeologie, no. 287, October 2003, pp. 97-113.

Jean Perrot and Youssef Madjidzadeh, “Découvertes récentes á Jiroft (sud du plateau Iranien),” CRAIBL, 2003, pp. 1087-1102.

Idem, “Récentes découvertes à Jiroft (Iran): Résultats de la campagne de fouilles, 2004,” CRAIBL, 2004, pp. 1105-20.

Idem, “L’iconographie des vases et objets en chlorite de Jiroft (Iran),” Paléorient31/2, 2005, pp. 123-52.

Idem, “À travers l’ornamentation des vases et objets en chlorite de Jiroft,” Paléorient 32/1:, 2006, pp. 99-112.

Holly Pittman “La culture du Halil Roud,” Dossiers d’Archeologie, no. 287, October 2003, pp. 78-87.

D. T. Potts, “In the Beginning: Marhashi and the Origins of Magan’s Ceramic Industry in the Third Millennium BC,” Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy 16/1, 2005, pp. 67-78.

(Oscar White Muscarella)

Originally Published: December 15, 2008

Last Updated: April 17, 2012

World's Oldest Ziggurat in Jiroft Being Excavated

25 Feb. 2006

|

Stairs of Konra-Sandal Ziggurat |

LONDON, (CAIS) -- The main part of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat of the Jiroft ancient site, located in the southern Iranian province of Kerman, has recently been excavated, the Persian service of CHN reported on Friday.

Before the discovery of the ziggurat in 2002, Chogha Zanbil, a major remnant of the Elamite civilization near Susa , was the only surviving ziggurat in Iran . Chogha Zanbil Ziggurat dates back to 1250 BCE.

“The main part of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat is the lower part and is 200 years older than the upper section. Thus, construction of the ziggurat was carried out in stages beginning in 2200 BCE,” said Professor Yusef Majidzadeh, the director of the archaeological team working at the site.

Built some time around 2100 BCE by king Ur-Nammu, the Ur Ziggurat is the oldest one inMesopotamia , but the Konar Sandal Ziggurat is a century older than it, he added.

The Ur Ziggurat was built in honor of the god Sin in Ur , a Sumerian city on the Euphrates , in the south of modern-day Iraq . It was called 'Etemennigur', which means 'house whose foundation creates terror'.

“The archaeologists have determined the original shape of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat for restoration,” Majidzadeh said.

Jiroft came into the spotlight nearly four years ago when reports of extensive illegal excavations and plundering of the priceless historical items of the area by local people surfaced.

Since 2002, two excavation seasons have been carried out at the Jiroft site under the supervision of Majidzadeh, leading to the discovery of a ziggurat made of more than four million mud bricks dating back to about 2200 BCE.

Jiroft is one of the richest historical areas in the world, with ruins and artifacts dating back to the third millennium BCE. Over 100 historical sites are located along the approximately 400 kilometers of the Halil Rud riverbank.

Many Iranian and foreign experts see the findings in Jiroft as signs of a civilization as great as Sumer and ancient Mesopotamia . Majidzadeh believes that Jiroft is the ancient city of Aratta , which was described as a great civilization in a Sumerian clay inscription.

ÂRYÂ (ARYAN)

Philology of Ethnic Epithet of Iranian Peoples

By Sir Harold Bailey

December 1987

ARYA, an ethnic epithet in the Achaemenid inscriptions and in the Zoroastrian Avestan tradition. It is used in the Avesta of members of an ethnic group and contrasts with other named groups (Tūirya, Sairima, Dāha, Sāinu or Sāini) and with the outer world of the An-airya "non-Arya." Old Persian ariya- occurs in the phrase of Darius: ariya: ariya: ciça, "Arya, of Arya origin," and of Xerxes: pārsa: pārsahyā: puça: ariya: ariyaciça, "a Persian, son of a Persian, Arya, of Arya origin." The phrase with ciça, "origin, descendance," assures that it is an ethnic name wider in meaning than pārsa and not a simple adjectival epithet. The corresponding Akkadian and Elamite offer the transcriptions a-ri-i, ar-ri-i ṣitir and har-ri-ia, har-ri-ia, ṣi-iš-ša. Elamite has also preserved the gloss to the name of the god Ahuramazdā: u-ra-mas-da na-ap har-ri-ia-na-um(Behistun 62), "Ahuramazdā, god of the Aryas." In DB 4.89 ariyā, "in the Arya," refers to script or language. The Avesta has the plural aire (Yt. 5.69): yaθa azəm avata vərəθra hačāne yaθa vīspe anye aire "may I possess so much force as all the other Aryas." The archer Ǝrəxša- (NPers. Āraš) is described (Yt. 8.6) as xšviwi.išvatəmō airyanąm "most swift-arrowed of the Aryas." Kavi Haosravō is called (Yt. 15.32) arša airyanąm "the hero (aršan- "male") of the Aryas." The dahyu- lands of the Aryas (gen. plur. airyanąmdahyunąm) are known; and once the pāδa- "settlement" is mentioned (Yt. 4.5 airyābyō pa’aēibyō). The xᵛarənah- "fortune" or (of royalty) a vague "glory," is coupled with the gen. plur. (airyanąm xᵛarənō) and with the adjective (airyanəm xᵛarənō). The same adjective qualifies vaēǰah- "extensive territory," in the name airyanəm vaēǰō, loc. sing. airyene vaēǰahi "the Aryan plain," the first of the lands created by Ahura Mazdā (Vidēvdāt 1.3). In Yašt 13.87, the phrase nāfō airyanąm daḣyunąm čiθrəm airyanąm daḣyunąm "the kindred of the Arya lands, the origin of the Arya lands," coincides in use of čiθra- with Old Pers. ariyaciça. Over against the Arya lands stand those which are anairya- "non-Arya" (as in anairyǡ diŋhāvō, Yt. 19.68); this dichotomy was continued later in Persian tradition.

Four place-names containing airya- occur in the Avesta. The airyō.šayana- "dwelling of the Aryas" (Yt. 10.14), comprises six names, of which four are well known: iškatəm pourutəmča mourum hārōyum gaomča suγδəm xᵛāirizəmča "Iskata, Pouruta, Margu, Haraiva, Gava-Sugda, Hvārazmi." The mountain Airyō-xšuθa (Yt. 8.6) was in eastern Iran: yaθa tiγriš mainya-asǡ yim aŋhaṱ ərəxšō xšviwi.išuš xšviwi.išvatəmō airyanąm airyō.xsuθaṱ hača garōiṱ xᵛ anvantəm avi gairīm "like the mind-swift arrow which the archer Ǝrexša shot, swift-arrowed, most swift-arrowed of the Aryas, from Mount Airyō-xšuθa to Mount Xvanvant." The forest (razurā, Yt. 15.32) called vīspe.aire.razuraya (loc. sing.) was where Kavi Haosravō slew Vāyu. The fourth name is the airyanəm vaēǰō, Zor. Pahl. ērān-vēž, frequent in the texts and remembered also in Manichean Sogdian ʾryʾn wyžn (*aryān vēžan) and Turfan Parthian (/ / / n wyžn, see W. B. Henning, BSOAS 11, 1943, p. 69). In Greek, Herodotus (7.62) stated that, in the past, the Medes had been called Arioi. The Greek use of Areia (Latin Aria) for Old Pers. Haraiva, Balōčī Harē(v), Arm. H(a)reu, was likely to cause confusion.

The same ethnic concept was held in the later centuries. The Dēnkard (ed. Madan, p. 438.23) offers hutōhmaktom ēr martōm "the best-born Arya man," associating arya- with good birth; cf. the Old Persian connection with birth in ariyačiça. Similarly ērīh ut dahyupatīh (ibid., 553.17) "nobility and lordship," contrasts with arg ut bār hač škōhišn, "labor and burdens from poverty." In the inscription of Šāpūr I on the Kaʿba-ye Zardošt (ŠKZ), Parth. ʾryʾn W ʾnʾryʾn (aryān ut anaryān), Mid. Pers. ʾyrʾn W ʾnyrʾn (ērān ut anērān; cf. Armenian eran eut aneran) comprises the inhabitants of all the known lands. The imperial title in Sasanian inscriptions is Parth. MLKYN MLKʾ aryān ut anaryān kē šihr hač yazdān. Mid. Pers. kē čiθrē hač yazdān, Greek arianōn kai arrarianōn (ŠKZ 1). In the singular Parth. ʾry, Mid. Pers. ʾyly, Greek arian occurs in a title: ʾry mzdyzn nrysḥw MLKʾ, *ary mazdēzn Narēsahv šāh (Parth. ŠKZ 19); ʾyly mzdysn nrsḥy MLKʾ (Mid. Pers. version 24), Greek arian masdaasnou. The empire is called ʾryʾn ḥštr(Parth.), ērān šahr (Zor. Pahl.). Armenian has retained arya- in nom. pl. ari-kʿ, gem. pl. areacʿ, and in sing. ari ayr "Arya man, Persian;" the negative anari-kʿ is found, as well as the Mid. Pers. phrase eran eut aneran. New Persian has ērān (western, īrān), ērān-šahr. In the Caucasus Ossetic has Digoron erä, irä, Iron ir, with Dig. iriston, Iron iryston (the i-umlaut modifying the vowel a-, but leaving the -r- untouched), the ancestral "Alān" and Latin (1459 A.D.) Arani. The name "Alān" is found in Greek Alanoi, Latin Alani, Chinese A-lan, Caucasian Megrel alani kʾočʿi "brave man," Georgian Alaneṭʿi "Alan country," Pers. Alān, Arab-Pers. al-Lān as the name of a people north of the Caucasus powerful until the Mongol invasion.

An ethical use of Zor. Pahl. ēr, anēr can be seen in Mēnōg ī xraḍ 20.15: anērīh ī hrōmāyīkān "the evil conduct of the Romans (i.e., Byzantines);" Dādīstān ī dēnīg 66.1: mart ī ēr ī hudēn "the Arya man of good faith" (here "noble").

Outside Iranian there is much further evidence in the Old Indian tradition of the Vedas and later texts. A word arya- with three accentuations (árya-, aryá-, aryà-) is traditionally glossed by īśvara- "owner, possessor," more vaguely "lord." This same meaning was also offered for Rig Veda arí-. But to compare with Iranian arya- the Indian tradition has āˊrya-. The latter is normally taken as an adjective by lengthened vowel (vṛddhi formation) but could also be explained by a long ā before two consonants. In the Vedas occurs Kāṭhaka āryaṃ varṇaṃ "the Arya color," contrasting with dāˊsaṃ várṇaṃ "the Dāsa color" of the enemies of the Arya people (RV 2.12.4). Beside this confrontation there is also the social difference of Jaiminīya āryaṃ ca varṇaṃ śaudraṃ ca "both the Ārya and the Śūdra color," the Śūdra being at first the workers. In RV 1.77.3 occurs devayántīr víśa . . . āˊrīḥ "the devout Ārya houses" (if this is the feminine to āˊrya-; the traditional rendering is from ar- "to move"). In later Indian texts the drama has āryaputra for the wife’s address to her husband: "son of an Arya" or "of a noble." In Buddhist sources ārya-, feminine āryikā-, is a laudatory epithet of the monk and nun used in place of bhikṣu- and bhikṣuṇī. It is used in some sense of "noble" of the Buddhist satyāni (true doctrines) and of the dharma- (doctrine) in the terms ārya-satyāni and ārya-dharma-. In ārya-dharma- the arya- is translated by Khotan Saka āysña "of high birth." The later Indian languages, Pali, and various Prakrits have the corresponding later forms. The Buddhist glosses confirm the sense of "high-born" or "noble" and "lord." Thus Tibetan has rje-po, rje-hu, jo-bo jo-hu "lord," with Chinese gloss "honored person;" Tibetan ya-rabs "high birth," renders āryatā (hence "nobility"). As laudatory epithet note also Āryadésa- "noble land," for India; and Ārya-bhāṣā- "noble language," for Sanskrit. Note, with Suffix, āryaka- "honored man," Pali ayyaka- "grandfather," and ayyakā- "grandmother." Hindu Sanskrit has āryāvarta. The contrast between ārya- "noble and dāsá- "slave" and dásyu- (the pejorative epithet) is missing in the Iranian tradition. Old Persian has dahyu- "a land and its people;" Turfan Parth. has dāhīft "slavery." But Khotan Saka daha- "man, virile person," and Waxī ’ai "hero" (*dahy-) are used in a good sense. To this daha- one can compare dása- "man" (RV6.21.11), who is set in a generation before mánu- "man."

These facts are undisputed, but no decision has yet been reached regarding the earlier meaning of the Iranian and Indian words. No evidence for such an Indo-European ethnic name has been found. The Irano-Indian ar- is a syllable ambiguous in origin, from IE. ar-, er-, or or-. The only evidence that this word is from Indo-European ar- is in the Celtic Old Irish aire "the free man" in Irish law, and aire (gen. sing. airech, nom. pl. airig) glossed by Latin optimas "of the best class." (The first component ario- of Germanic names may always be identified with hario- "army, troop." The Celtic first component ario- in names is uncertain because Celtic lost initial p-.) On this slight evidence it has been usual to accept Indo-European ar- as the base. Attempts to connect arya- with other basic words have been many. H. Güntert, Der arische Weltkönig und Heiland (Halle, 1924), proposed "allied" (base ar- "to fit"). Paul Thieme offered a detailed proposal to trace Rigvedic arí, glossed īśvara- and arí, Atharvavedic ári- "enemy" (AV 13.1.29: árir yó naḥ pṛtanyati "the foe who fights against us"), together with arya- and ārya-, to a primitive society in which the mutual connection of host and guest was expressed by the one word; he translated it "stranger" (Der Fremdling in Ṛgveda, Leipzig, 1938). This was adopted by L. Renou (Ētudes védiques et pāṇinéennes II, Paris, 1956, pp. 109-11) and in Wackernagel-Debrunner (the revised preface) but criticized by G. Dumézil, Le troisième soverain, Paris, 1949. It places the work too early in Indo-European times and hardly offers a way to advance from "stranger" to an ethnic name. A different explanation was proposed by the writer in "Iranian arya and daha-," TPS, 1959, pp. 71-115 and supplementary note TPS, 1960, pp. 87-88. Accepting the interpretation of arí- and arya- by īśvara- "possessor," these words were traced to a base ar- well attested in Iranian in the sense of "get" and "cause to get, give." Avestan has ar- and Ossetic ar-; cf. Greek arnumai "to get," and Armenian aṙnoum "to take," hence Indo-European ar-. (The word ari-, ári- "enemy," however, was connected with Rigvedic ṛti- "attack," and Iranian Pahl. artīk "attack," and so to Indo-European er-.) For arya-, the Iranian ethnic name, it was proposed to start from the sense of "good birth" and so with Ossetic ār-: ārd "to bear young," a specialized meaning of the same IE. base ar-. Cf. Old Norse geta "to get," also "to bear young," getinn "born." The stage of society represented by the word was the oikarkhia, birth into which gave nobility; this is expressed by the later use of ā-zan- as in āzāta- "born into the House, noble;" in the Indian tradition it is expressed by ājāneya- "well born" (said of man or animal). This arya-, Indian ārya- "noble," was thus an excellent name for a people; and it favored the further development into an ethical concept of "excellence, nobility." The identification of ar- with ā-zan- is attested by the Khotan Saka rendering of arya- by āysña- from *ā-zan-ya-, for which Avestan provides āsna- "well born," and Man. Mid. Pers. āznān, Armenian azniu "excellent, noble." The Celtic *ariak "free man" and "optimas" fit here admirably. Note, too, that (with causative -nu-) Hittite ar-nu- "to bring an animal to copulation," can best be placed with this same Iranian Ossetic ār- "to bear young, give birth," rather than with Greek ornumi "to stir up, excite." For the pregnant meaning "good birth" for arya-, note how Latin gentīlis, originally simply "of the family," was in the Romance languages changed to the meaning "noble." Hittite arawa- "free, noble" could be brought in here in preference to E. Laroche, Hommages à G. Dumézil, Brussels, 1960, pp. 124-28, where it is traced to ara- "friend," and compared with Gothic freis "free," and frijonds "friend."

Arya- as first component in proper names becomes ambiguous if two words existed: arya- "Aryan," and *arya- "wealth" (cf. Man. Parth. ʿyr, Arm. ir, Mid. Pers. xīr, Khotan Saka hära-, all meaning "thing"). Such names are Old Pers. Ariyāramna (Greek Ariaramnēs), Ariobarzanēs, Elamite Harrikhama, Harrimade, Harrimana, Harripirtan; Lydian Arijamaña; Nisa Parthian ʾrymtrk, ʾrybrzn; the Sogdian name of the capital city Bukhara: in Chinese, A-lam-mit from *aryāmēθa(n) (J. Markwart, Wehrot und Arang, Leiden, 1938, p. 140), later Rāmēθan.

Finally various explanations have been offered for Rigvedic Aryamán-, Avestan airyaman-, where the first component has been rendered "true, Aryan, wealth." The supernatural being (called ādityá-) Aryaman has the epithet sátpati- "official in the house." He is in charge of the treasury; hence this writer has preferred to explain his name as "the being in charge of riches and hospitality."

Bibliography:

![]() | O. Schrader and A. Nehring, Reallexikon der indogermanischen Altertumskunde, Berlin and Leipzig, 1917-23 (s.v. Arier). |

![]() | A Debrunner, "Zum Ariernamen," in A Volume of Eastern and Indian Studies Presented to F. W. Thomas, Bombay, 1939, pp. 71-74. |

![]() | W. Belardi, "Sui nomi ari nell’Asia anteriore antica," Fontes Ambrosiani XXVII, 1951, pp. 55-74. |

![]() | M. Mayrhofer, Kurzgefasstes etymologisches Wörterbuch des Altindischen I, Heidelberg, 1956, pp. 49,70, etc. |

![]() | Idem, Onomastica persepolitana, Vienna, 1973, nos. 8.458, 8.472, etc. |

![]() | H. W. Bailey, "The Second Stratum of the Indo-Iranian Gods", in Mithraic Studies, ed. J. R. Hinnells, Manchester, 1975, pp. 1-20. |

12 June 2004

An Iranian scholar believes Elamites used a decimal system in their bills to reflect the heightened importance of trade at that era.

“Studies on an inscription representing an Elamite bill manifest they were the first people in Iran to use a decimal system in their business transactions. Other inscriptions in pictorial language of pre-Elamite show animals, vessels and other objects standing for fractions and decimal numbers,” said Rogha’eh Behzadi, the author of “Ancient Tribes in Caucasus, Mesopotamia, and the Fertile Crescent”.

She added, “On these tablets, there some designs of circles and the thumb. A small circle is believed to have been used to represent zero while the thumb was a symbol of 1. The pre-Elamites language was read from right to left.”

Elam first came into existence sometime between 3500 and 2500 BC. In around 2000 BC the Elamite dynasty conquered most of southern Mesopotamia.

At its zenith, Elam controlled an empire that stretched from what is now the Baghdad area to the entrance of the Persian Gulf. The Assyrians sacked the Elamite capital, Susa, in 647 BC.

Jiroft is the Ancient City of Marhashi: Piotr Steinkeller

8 May 2008

LONDON, (CAIS) -- Piotr Steinkeller, professor of Assyriology in Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations of Harvard University, believes that the prehistoric site of Jiroft is the lost ancient city of Marhashi.

He developed the theory in his paper during the first round of the International Conference on Jiroft Civilisation, which was held in Tehran on May 5 and 6.

Marhashi, (in earlier sources Warahshe) was a 3rd millennium BCE polity situated east of Elam, on the Iranian plateau. It is known from Mesopotamian sources, and its precise location has not been identified. An inscription of Lugal-Anne-Mundu, the most important king of the Adab city-state in Sumer, locates it, along with Elam, to the south of Gutium, an ancient polity in upper Mesopotamia. The inscription also explains that Lugal-Anne-Mundu confronted the Warahshe king, Migir-Enlil.

Jiroft is the lost ancient city of Marhashi, which had been located between Anshan and Meluhha, Steinkeller said.

Anshan was one of the early capitals of Elam, from the 3rd millennium BCE, which is located 36 kilometers northwest of modern Shiraz in Fars Province, southwestern Iran.

The Indus Valley Civilization has been tentatively identified with the toponym Meluhha known from Sumerian records.

According to Steinkeller, Marhashi was a political and economic power in eastern Iran, which had been in a close contact with Babylonia. This relationship had been developed over two periods, which has influenced the political history of the region for at least a half century.

Steinkeller had previously been searching the Kerman region in order to identify a site from the 3rd millennium BCE, which he could consider it as Marhashi. He had found Tappeh Yahya and Tall-e Eblis, but he believes that Tappeh Yahya is too small to be considered as Marhashi and Tall-e Eblis has been has almost entirely been destroyed over the years.

Thus, he said that Jiroft is the heart of the ancient city of Marhashi and hoped that upcoming excavations and studies would help archaeologists discover other parts of the city.

According to the conference scientific secretary Professor Yusef Majidzadeh, over 700 ancient sites such as Tappehs and graves have been discovered in Jiroft over the past six seasons of excavation by a team of archaeologists led by Majidzadeh.

Located next to the Halil-Rud River in southern Iran’s Kerman Province, Jiroft came into the spotlight in 2002 when reports surfaced of extensive illegal excavations being carried out by local people who went on to plunder priceless historical items.

Majidzadeh team unearthed a great number of artefacts at Jiroft as well as three tablets in one of the present-day villager’s homes and a brick inscription near Jiroft’s Konar-Sandal region wherein they also discovered ruins of a large fortress, which previously was believed to be a ziggurat. The structure is surmised have been made of more than four million mud bricks.

The pottery works and the shards discovered in the Konar-Sandal fortress date back to an interval between the fourth millennium BCE and early years of the Islamic period, Majidzadeh said during the conference.

Once, Majidzadeh had said that Jiroft is the ancient city of Aratta, which was described in a Sumerian clay inscription as an impressive center of civilization. In December 2007, he suggested that archaeologists use the term Proto-Iranian instead of Proto-Elamite for the script found at Jiroft.

He believes that the world should revise its knowledge of the Eastern civilizations due to the inscriptions discovered at Jiroft.

Majidzadeh describes the inscriptions as unique and also elaborates that the tablets and the brick inscription bearing a script which has been invented along with the Mesopotamia script at the same time.

A great number of Iranian and foreign archaeologists and scholars will discuss latest studies on the Jiroft civilization during the conference, which will be continued in Jiroft from May 8 to 9.

Photo: A team of archaeologists work on a prehistoric site near Konar-Sandal in the Jiroft region in undated photo. This site was previously believed to be a ziggurat.

Jiroft Inscriptions Necessitate Reconsideration of Eastern Civilizations: Majidzadeh

LONDON, (CAIS) -- Iranian archaeologist Professor Yusef Majidzadeh believes that new inscriptions discovered at the 5000-year-old sites of Jiroft invites us to a revise our knowledge of the Eastern civilizations.

Majidzadeh described the inscriptions as unique and added, “We have discovered a script which has been invented along with the Mesopotamia script at the same time.”

“The script is geometrical and differs from the Mesopotamian one. Thus, the discovery of this script is very important for the world, because many traditional theories on the Eastern civilizations must be revised because of the discovery of the new script,” he added.

However, this idea is in opposition to the previous theory crediting the Sumerians of ancient Mesopotamia with inventing the earliest system of writing, which appeared ca. 3500 BCE.

During the past six seasons of excavation by a team of archaeologists led by Majidzadeh, the team had unearthed three tablets in one of the present-day villager’s homes and a brick inscriptions near Jiroft’s Konar-Sandal region wherein they also discovered a ziggurat made of more than four million mud bricks.

Located next to the Halil-Rud River in southern Iran’s Kerman Province, Jiroft came into the spotlight in 2002 when reports surfaced of extensive illegal excavations being carried out by local people who went on to plunder priceless historical items.

In November 2007, the team returned to Jiroft in order to renew digs of the site in the hope of finding further artifacts bearing inscriptions, but this season came to an end with no result.

According to Majidzadeh, it is roughly impossible to decipher the inscriptions due to little number of discovered items bearing such writings.

“The deciphering of ancient writings such as hieroglyphic and cuneiform scripts have been carried out using a tablet or a brick that bore bilingual inscriptions which referred to the same subject and one inscription could be read by another one,” he explained.

“We should search Jiroft for a bilingual tablet or something like that which would enable us to read the geometrical script, otherwise deciphering the inscriptions are unattainable. In nay case, the important fact is that the Jiroft inscriptions are part of a civilization,” he added.

After numerous unique discoveries had been made in the region, Majidzadeh declared Jiroft to be the cradle of art.

Many scholars questioned this theory due to the fact that no writings had been discovered at the site, but shortly afterwards his team discovered the inscriptions.

The inscriptions are older than the oldest inscriptions, such as the Inshushinak, found at Elamite sites.

Many Iranian and foreign experts consider the Jiroft findings as evidence for the existence of a civilization in Jiroft as great as that of Sumer or ancient Mesopotamia.

Majidzadeh believes that Jiroft is the ancient city of Aratta, which was described in a Sumerian clay inscription as an impressive center of civilization. In December 2007, he suggested that archaeologists use the term Proto-Iranian instead of Proto-Elamite for the script found at Jiroft.

Latest studies on the Jiroft civilization are scheduled to be discussed during a conference, which will be held in Tehran, Kerman, and Jiroft from May 5 to 9.

Majidzadeh is the scientific secretary of the conference, which its first edition was held in 2004.

![]()

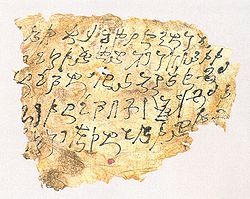

The inscription on a brick found in the archeological site of Jiroft is identified by experts as a manuscript belonging to the Elamite era.

The inscription which includes two lines proves that the residents of the area enjoyed writing during the Bronze Age (the first half of the third millennium BC).

Jiroft historical site, which is located next to the Halilrood River in the central province of Kerman, has been called “Archeologists’ Lost Heaven”. Numerous ancient items and remains have been discovered there during the last three years.

The inscription on the brick is not the first example of handwriting found in Jiroft and some other evidence had previously been identified among seal impressions, however, it is notable with respect to the reassurance it gives experts concerning the existence of handwriting then.

The inscription is written on a brick, of which only the left corner and two written lines remain. Enough to have archeologists categorize it as an Elamite one, explained head of the Jiroft excavation team, Yusef Majidzadeh.

The most known Elamite manuscript is the inscription of In-Shushinak, the Elamite King, which dates to the second millennium BC and has been unearthed in the Susa diggings, Khuzestan, south of Iran. Meanwhile, the oldest discovered handwriting is early Elamite dating to the third millennium BC.

Elamite manuscripts have previously been found in Susa, the Burnt City, and some other ancient sites.

Majidzadeh and Holly Pittman, an ancient art professor at the University of Pennsylvania working in Jiroft are optimist that further diggings will lead to an understanding of the more ancient developments and maybe the root of the newly discovered handwriting. It is not yet read, but the archeologists say it is probably a building inscription or an offering to the King.

Archaeologists have Discovered the World's Oldest Inscription in Jiroft

5 November 2007![]() LONDON, (CAIS) -- Archaeologists have discovered the world's most ancient inscription in the Iranian city of Jiroft, near the Halil Roud historical site, according to Iran Press TV.

LONDON, (CAIS) -- Archaeologists have discovered the world's most ancient inscription in the Iranian city of Jiroft, near the Halil Roud historical site, according to Iran Press TV.

"The inscription, discovered in a palace, was carved on a baked mud-brick whose lower left corner has only remained,” explained Professor Yousof Majid-Zadeh, head of the Jiroft excavation team.

“The only ancient inscriptions known to experts before the Jiroft discovery were cuneiform and hieroglyph,” said Majid Zadeh, adding that,”the new-found inscription is formed by geometric shapes and no linguist around the world has been able to decipher it yet.”

Archaeologists have found many artefacts confirming the existence of a rich civilization dating back to the third millennium BCE, during the 5 previous seasons.

The sixth season of Jiroft excavations will focus on the temple and the sites where the tablets were found during previous phases.

Archaeologists believe the discovered inscription is the most ancient written script found so far and that the Elamite written language originated in Jiroft, where the writing system developed first and was then spread across the country.

http://www.cais-soas.com/News/2007/November2007/05-11.htm

Jiroft Inscription the Most Controversial Discovery in the Region: Majidzadeh

8 March 2007LONDON, (CAIS) -- Director of the excavation team in Jiroft historical site said that the traces of primitive scripts are the most controversial findings in the region since it invalidates claims by foreign archaeologists that until the Achaemenid era, the writing was unknown to Iranian peoples.

According to Persian service of ISNA, Professor Yousef Majidzadeh, who was speaking in a meeting titled ’Latest Jiroft Excavation’ added that currently explorations are being conducted in Matoutabad, Hosseinabad and Konar Sandal. The main section of the studies focuses on Konar Sandal, he noted.

Most of the objects discovered, particularly the earthenware found in cemeteries, are mythological oriented since they pertain to life after death, he said, adding that the origin of the belief is not yet clear.

He stated, “Jiroft culture is self-existent and cannot be compared to that of Mesopotamia to conclude that such beliefs were not indigenous.“

Probably the Achaemenid art has its root in Jiroft because common elements have been found in the two, Majidzadeh said.

Referring to the four inscriptions found in the region, he said that based on carbon tests conducted in Pennsylvania University, they date back to 2500 BCE.

The script used in writing them is totally different from the Mesopotamian script or even the Egyptian Hieroglyph, he said.

“We have called the script geometric or Jiroft script, which is similar to scripts which were once prevalent in Ilam for a period of 20 years,“ he concluded.http://www.cais-soas.com/News/2007/March2007/08-03-jiroft.htm

Foreign Experts to Attempt to Decipher Newly Discovered Jiroft Script15 February 2005

The brick inscription which was recently discovered in Konar Sandal at the ancient site of Jiroft will be studied by foreign experts who will attempt to decipher its text, the director of the archaeological team working on Jiroft and the Halil-Rud River cultural area announced on Tuesday.

The archaeological team determined in initial studies that the inscription dates back to the Bronze Age (the first half of the third millennium B.C.).

“The inscription proves that writing was in use in the region at the time and it will shed light on the dark corners of life in the first half of the third millennium B.C. Thus, we decided to give the inscription to an expert from France and several others from the U. S.,” Yusef Majidzadeh added.

“Although only the left corner and two lines of writing remain, the script of the inscription has been definitely identified as Elamite,” he said.

The oldest Elamite script, known as Proto-Elamite, first appeared in about 2900 B.C. in Susa, the capital of Elam, in the southwestern Iranian province of Khuzestan. The Proto-Elamite script is thought to have been developed from an early Sumerian script.

Old Elamite was a syllabic script derived from Proto-Elamite and was known to have been used between about 2250 and 2220 B.C., although it may have been invented at an earlier date. The Inshushinak inscription, found during an excavation in Susa, had been written in this type of script.

“The Konar Sandal inscription is older than the Inshushinak inscription, thus it seems that the recently discovered inscription will link proto and old Elamite scripts,” Majidzadeh said.

Known as the “archeologists’ lost heaven”, the ancient site of Jiroft is located next to the Halil-Rud River in the southern province of Kerman. Numerous ancient ruins and artifacts of Jiroft have been excavated by archaeologists, and also by smugglers unfortunately, over the past three years.

http://www.cais-soas.com/News/2005/February2005/15-02.htm

Jiroft Inscription, Oldest Evidence of Written Language

12 January 2006

LONDON, (CAIS) -- Studies by five linguists from the United States, France, Russia, Denmark, and Iran on a discovered inscription in Jiroft indicate that this Elamite script is 300 years older than that of the great civilization of Susa.

![]()

Archeologists believe that Jiroft was the origin of Elamite written language in which the writing system developed first and was then spread across the country and reached Susa. The discovered inscription of Jiroft is the most ancient written script found so far.

The city of Jiroft is situated close to Halil-Rud historical site. Halil-Rud, located on the basin of Halil-Rud River enjoyed a rich civilization. Many stone and clay objects as well as other historical evidence belonging to the 3rd millennium BC have been discovered during the archeological excavations and also the illegal diggings by the smugglers in this area. 120 historical sites, including that of Jiroft, have been identified in the basin of the 400 kilometer length of Halil-Rud River.

According to archeological studies, the history of Halil-Rud area goes back to some 3000 years ago. The discovered stone dishes in the area belonging to the first half of the third millennium BC point to the developed art of carving on stones at that time.

“Five Elamite professional linguists from different countries have studied the brick inscription discovered in Jiroft. According to the studies, they have concluded that this discovered inscription is 300 years older than that found in Susa; and most probably the written language went to Susa from this region. However, more studies are still needed to give a final approval to this thesis,” said professor Yousof Majid Zadeh, head of archeological excavation team in Jiroft.

“This inscription was discovered in a palace. Although it is not yet known which Elamite king this inscription belongs to, it is definitely an Elamite inscription. More studies are needed to determine the exact time in which it was inscribed, but most probably it is the most ancient written language. Further excavations are being carried out to find the rest of the inscription. However, what is obvious about this discovered inscription is that it is older than the Elamite inscription of Susa,” explained Majidzadeh.

The inscription was carved on a brick, and only the lower left corner of it has been remained. Although only two lines with a few words are remained intact on this inscription, there is no doubt that it is an Elamite written script.

The most famous Elamite script is the Susinak inscription which was unearthed during archeological excavations in Susa. This inscription is most probably left from the reign of Susinak, Elamitee king who ruled during the second half of the first millennium BC. .

Elamite language is only partly understood by scholars. It had no relationship to Sumerian, Semitic or Indo-European languages, and there are no modern descendants of it. After 3000 BC the Elamites developed a semi-pictographic writing system called Proto-Elamite. Later the cuneiform script was introduced.

Archeological excavations are being carried out in north and south shores of the Halil-Rud River in order to discover different dwellings and cemeteries in the region.

The wide plundering of the historical and archeological relics by the smugglers led to the lost of a lot of these invaluable evidences. Most of these historical relics were taken out of the country. Although Iran is trying to redeem them, some of those who have collected these relics refuse to give them back claiming that these articles were not made in Iran and thus don’t belong to this country. Iranian archeologists are trying to discover more evidence to prove Iran’s possession over these historical objects.

News Source: CHN

http://www.cais-soas.com/News/2006/January2006/12-01.htmSecond Royal Inscription Discovered at Joroft's Konar Sandal Ziggurat

8 April 2006

![Related image]()

![Related image]()

LONDON, (CAIS) -- A team of archaeologists working at the ancient site of Jiroft recently discovered a second royal inscription at the Konar Sandal Ziggurat, the Persian service of CHN reported on Thursday.

Team member Nader Soleimani said that the discovery provides further evidence that Jiroft dates back to the third millennium BCE.

The inscription is on an 11x7 centimeter piece of brick which bears five lines with each line containing 12 words, Soleimani added.

“The first example was found during the previous excavations, which French archaeologist Jean Perrot called a royal edict. Considering the similarity of the newly discovered inscription with the previous one, experts surmise that this is the second royal decree.

“The inscription was found near the stairway of the upper section of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat, which is a century older than the Ur Ziggurat,” he explained.

The Konar Sandal Ziggurat is one of the ruins of ancient Jiroft, which is located in the southern Iranian province of Kerman.

Analysis of pieces of coal discovered during last year’s excavations of Jiroft indicates that the oldest layer of the region dates back to 2800 BC.

Many Iranian and foreign experts see the findings in Jiroft as signs of a civilization as great as Sumer and ancient Mesopotamia.

Iranian expert Yusef Majidzadeh believes that Jiroft is the ancient city of Aratta, which was described as a great civilization in a Sumerian clay inscription.

Jiroft Inscription the Symbol of Eastern Civilisatio

n30 May 2006

![]()

LONDON, (CAIS) -- In his latest research paper about the discovered inscription in Konar Sandal in Jiroft, Piotr Steinkeller, professor of Assyriology in Department of Near Eastern Languages and Civilizations of Harvard University, explains that there exists no correlation between the inscriptions discovered in Jiroft, Shahdad, and Melian historical sites with the Elamite civilization which itself was under the influence of the Mesopotamian civilization, and they should be considered as an eastern written language.

“In his latest paper, Prof. Steinkeller has explained that there should not have been any relation between the discovered inscription in Jiroft and Elamite civilization, which itself was under the influence of Mesopotamian civilization. Steinkeller believes that it would be better to throw away this way of thinking and say ‘eastern script’ instead of ‘Elamite script,’” said Yousof Majidzadeh, head of excavation team in Jiroft.

The Elamite script is known to belong to Khutelutush-In-Shushinak (c. 1120 - 1110 BCE), the Elamite king. Experts believe that it is not logical to accept that a nation, who has a writing language itself, abandons its script after the conquest of a powerful neighbor and adopt Mesopotamian culture and script. They believe that this script found its way to Susa from eastern Iran.

“Decoding the discovered inscription in Jiroft requires a lot of time. However, archaeologists believe that this script must have been more ancient than that of the Elamite civilization. Further archaeological excavations in Jiroft historical site might help researchers to learn more about the identity of this inscription. We had two different writing languages in Iran during ancient times: One of them is Proto-Elamite script, which was mainly figures and numbers, and the other was writing language which did not use images. Prior to the discovery of Jiroft inscription, the most ancient script had been found in Susa historical site which has remained from the reign of Khutelutush-In-Shushinak. This inscription dates back to 1200 BCE, while the Jiroft inscription is older than that and is estimated to be between 4400 to 4500 years old,” added Majidzadeh.

Elam is one of the most ancient civilizations on record. It was centered in the far west and southwest of today Iran. The Elamites came in power about 300 years after the fall of the Jiroft Kingdom (5000-3000 BCE). The reign of the Elamite kings lasted from 2700 to 539 BCE, coming after what is known as the Proto-Elamite period which began around 3200 BCE when Susa, the later capital of the Elamites, began to receive influences from the cultures of the Iranian Plateau to the east.

“It is believed that Jiroft’s writing language came into existence at the same time Mesopotamia started developing a writing system. According to the carbon 14 tests conducted on the layers in which Jiroft inscription was discovered, this inscription was dated to 2500 BCE. Although such tests have not been carried out on Mesopotamia inscription yet, based on the discovered evidence so far, archaeologists strongly believe that Mesopotamia’s script goes back to 2600-2700 BCE at most,” explained Majidzadeh.

The new discoveries during the archaeological excavations in Konar Sandal such as historical inscriptions, the most ancient ziggurat of the world, and many other historical relics have confused archaeologist and confronted them with an unknown civilization in the east. This further led into revisions on some previous archaeological hypotheses.

The city of Jiroft is situated close to Halil Rud historical site in Kerman province. The discovered stone dishes in the area belonging to the first half of the third millennium BCE point to the developed art of carving on stones at that time. The second inscription that was recently discovered at the Konar Sandal Ziggurat of Jiroft is scheduled to be deciphered by teams of researchers from the University of Chicago and the University of Paris. Archeologists are waiting for the results to come out which may well change the history of civilization as we know today.

![]() Professor Piotr Steinkeller

Professor Piotr Steinkeller

Semitic Museum

Harvard University

6 Divinity Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

Semitic Museum, Room 103

617-495-0553

617-496-8904

steinkel@fas.harvard.edu

Before coming to teach at Harvard (in 1981), Professor Steinkeller pursued research at the Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago. His scholarly work deals broadly with the history, culture, and languages of early Mesopotamia (3000-1500 BCE), its particular focus being the socioeconomic history of Babylonia during the 3rd mil. BCE and, most recently, the early history of Sumero-Akkadian religion. He is also interested in Mesopotamian archaeology, as evidenced in his present involvement in an archaeological project at the site of Tell Arbid in north-west Syria. Among his ongoing projects is a study of the population density and settlement patterns in Babylonia at ca. 2900 BCE, which utilizes both textual and archaeological data, and an investigation of the economic organization of the Ur III state (2900-2000 BC). He has written or co-authored three books and over eighty articles and book reviews. He teaches a wide range of courses and seminars on the Sumerian and Akkadian languages, Mesopotamian religion, and history of ancient Mesopotamia.

French & US Experts to Decipher Jiroft Inscription

9 April 2006

LONDON, (CAIS) -- The second inscription that was recently discovered at the Konar Sandal Ziggurat of the Jiroft ancient site is scheduled to be deciphered by teams of researchers from the University of Chicago and the University of Paris.

The inscription, which is on a brick 11x7 centimetres with a depth of two centimetres, is more intact than the first inscription discovered during the previous phase of excavations carried out at the site last year. Only the left corner and two lines of writing remain of the first inscription.

“Professor Yusef Majidzadeh has sent pictures of the inscription to the researchers, who believe the previous inscription was an imperial decree,” Nader Soleimani, a member of the archaeological team working at Konar Sandal, told the Persian service of CHN on Saturday.

Due to the similarities between the words written in Elamite on both inscriptions, Iranian archaeologists believe that the new inscription is also an imperial decree. The inscription has five lines, each with about 12 words.

Known as the “archeologists’ lost heaven”, the ancient site of Jiroft is located next to the Halil-Rud River in the southern province of Kerman. Many ancient ruins and artifacts of Jiroft have been excavated by archaeologists, and also by smugglers, unfortunately, over the past four years.

After numerous artifacts were discovered in the region, Majidzadeh, the director of the archaeological team working on Jiroft and the Halil-Rud River cultural area, named Jiroft the cradle of human art. Many scholars doubted the idea due to the fact that no writings or architectural structures had yet been discovered at the site, but the newly discovered writings have caused experts to reconsider their views on the site.

The oldest Elamite script, known as Proto-Elamite, first appeared in about 2900 BCE in Susa, the capital of Elam, in the southwestern Iranian province of Khuzestan. The Proto-Elamite script is thought to have been developed from an early Sumerian script.

Old Elamite was a syllabic script derived from Proto-Elamite and was known to have been used between about 2250 and 2220 BCE, although it may have been invented at an earlier date. The Inshushinak inscription, found during an excavation in Susa, had been written in this type of script.

The Konar Sandal inscriptions are older than the Inshushinak inscription, thus it seems that the recently discovered inscriptions link Proto and Old Elamite scripts.

Legend in Prakrit (Brahmi script, from left to right):: "Rajnah Kunindasya Amoghabhutisya maharajasya." Obverse: Kharoshti legend. AIC pg. 146, 1; MACW 4442; Senior pg. 233. Legend in Kharoshti script, from righ to left: Rana Kunidasa Amoghabhutisa Maharajasa, ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas").

Tin Road: Ashur-Kultepe and Meluhha hieroglyphs

![]() The land of Kuninda (also called Kulinda) stretched along the foothills of the Himalayas eastwards from the borders of Audumbara (c. 150-100 BCE) temporarily independent of the Punjab area in the Pathankot region of the Beas river valley to the borders of Nepal.

The land of Kuninda (also called Kulinda) stretched along the foothills of the Himalayas eastwards from the borders of Audumbara (c. 150-100 BCE) temporarily independent of the Punjab area in the Pathankot region of the Beas river valley to the borders of Nepal.

![]() Legend in Prakrit (Brahmi script, from left to right):: "Rajnah Kunindasya Amoghabhutisya maharajasya." Obverse: Kharoshti legend. AIC pg. 146, 1; MACW 4442; Senior pg. 233. Legend in Kharoshti script, from righ to left: Rana Kunidasa Amoghabhutisa Maharajasa, ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas").

Legend in Prakrit (Brahmi script, from left to right):: "Rajnah Kunindasya Amoghabhutisya maharajasya." Obverse: Kharoshti legend. AIC pg. 146, 1; MACW 4442; Senior pg. 233. Legend in Kharoshti script, from righ to left: Rana Kunidasa Amoghabhutisa Maharajasa, ("Great King Amoghabhuti, of the Kunindas").The hieroglyphs on the Kuninda/Puninda silver coin of ca. 2nd century BCE are : on the obverse a deer to the right of a female figure (facing) and holding a flower in right hand and her left hand rests on the thigh with inscriptions written around. On the reverse a five-arched hill in the centre surmounted by a Nandi-pada symbol, on the right is a tree in a railing and on the left two symbols: svastika and 'standard device' sangaḍa 'lathe, portable furnace'.

Animal-human hieroglyph multiplex: ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin' barad 'ox' rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' hangi 'molluscs' rebus: sangi 'pilgrim'. The woman with a 'lotus' flag is Lakshmi with tAmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tAmra 'copper'.

The mollusc 'sangi' may also connote s'ankhanidhi (one of nine nidhi or treasures of Kubera) as on a Bharhut frieze with a flag-bearer carrying a s'ankha (turbinella pyrum) mounted post:

kola 'woman' Rebus: kola 'working in iron'.

melh ‘goat’ (Brahui) Rebus: milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali)

kāṇḍa ‘flowing water’ Rebus: Ku. lokhaṛ ʻiron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ(CDIAL 11171).

ḍangar 'bull', ḍã̄g mountain-ridge (H.)(CDIAL 5476). Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili)

The 'nandipada' hieroglyph may signify tied-up pair of fish with a rope: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' aya 'fish' rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal', dhAtu 'strand of rope' rebus: dhAtu 'mineral'. Thus, together with the mountain-ridge hieroglyph, the combined message is: ironsmith.

satthiya 'svastika glyph' Rebus satthiya, jasta 'zinc' (Kashmiri. Kannada); sattva 'zinc' (Prakrit)

![]()

khambhaṛā 'fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'coiner, coinage, mint' aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'. Thus, the srivatsa hypertext on Kuninda coin signifies an alloy metalcasting mint PLUS Hieroglyph: seed, something round: *gōṭṭa ʻ something round ʼ. [Cf. guḍá -- 1. -- In sense ʻ fruit, kernel ʼ cert. ← Drav., cf. Tam. koṭṭai ʻ nut, kernel ʼ, Kan. goṟaṭe &c. listed DED 1722]K. goṭh f., dat. °ṭi f. ʻ chequer or chess or dice board ʼ; S. g̠oṭu m. ʻ large ball of tobacco ready for hookah ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; P. goṭ f. ʻ spool on which gold or silver wire is wound, piece on a chequer board ʼ; N. goṭo ʻ piece ʼ, goṭi ʻ chess piece ʼ; A. goṭ ʻ a fruit, whole piece ʼ, °ṭā ʻ globular, solid ʼ, guṭi ʻ small ball, seed, kernel ʼ; B. goṭā ʻ seed, bean, whole ʼ; Or. goṭā ʻ whole, undivided ʼ, goṭi ʻ small ball, cocoon ʼ, goṭāli ʻ small round piece of chalk ʼ; Bi. goṭā ʻ seed ʼ; Mth. goṭa ʻ numerative particle ʼ; H. goṭf. ʻ piece (at chess &c.) ʼ; G. goṭ m. ʻ cloud of smoke ʼ, °ṭɔ m. ʻ kernel of coconut, nosegay ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ lump of silver, clot of blood ʼ, °ṭilɔ m. ʻ hard ball of cloth ʼ; M. goṭā m. ʻ roundish stone ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ a marble ʼ, goṭuḷā ʻ spherical ʼ; Si. guṭiya ʻ lump, ball ʼ; -- prob. also P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ.*gōḍḍ -- ʻ dig ʼ see *khōdd -- .Addenda: *gōṭṭa -- : also Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271) Ta. koṭṭai seed of any kind not enclosed in chaff or husk, nut, stone, kernel; testicles; (RS, p. 142, items 200, 201) koṭṭāṅkacci, koṭṭācci coconut shell. Ma. koṭṭakernel of fruit, particularly of coconut, castor-oil seed; kuṟaṭṭa, kuraṭṭa kernel; kuraṇṭi stone of palmfruit. Ko. keṭ testes; scrotum. Ka. koṭṭe, goṟaṭe stone or kernel of fruit, esp. of mangoes; goṭṭa mango stone. Koḍ. koraṇḍi id. Tu. koṭṭè kernel of a nut, testicles; koṭṭañji a fruit without flesh; koṭṭayi a dried areca-nut; koraṇtu kernel or stone of fruit, cashew-nut; goṭṭu kernel of a nut as coconut, almond, castor-oil seed. Te. kuriḍī dried whole kernel of coconut. Kol. (Kin.) goṛva stone of fruit. Nk. goṛage stone of fruit. Kur. goṭā any seed which forms inside a fruit or shell. Malt. goṭa a seed or berry. / Cf. words meaning 'fruit, kernel, seed' in Turner, CDIAL, no. 4271 (so noted by Turner).(DEDR 2069) Rebus: khōṭa 'alloy ingot' (Marathi)

kharosti 'blacksmith lip, carving' and harosheth 'smithy' Suniti Kumar Chatterjee suggested that kharōṣṭī may be cognate with harosheth in: harosheth hagoyim 'smithy of nations'. Etymology of harosheth is variously elucidated, while it is linked to 'chariot-making in a smithy of nations'. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harosheth_Haggoyim See also: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/11/archaeological-mystery-solved-site-of.html Harosheth Hebrew: חרושת הגויים; is pronounced khar-o-sheth? Most likely, (haroshet) a noun meaning a carving. Hence, kharoṣṭī came to represent a 'carving, engraving' art, i.e. a writing system. Harosheth-hagoyim See: Haroshet [Carving]; a forest; agriculture; workmanship;Harsha [Artifice: deviser: secret work]; workmanship; a wood http://tinyurl.com/d7be2qh Cognate with haroshet: karṣá m. ʻ dragging ʼ Pāṇ., ʻ agriculture ʼ Āp.(CDIAL 2905). karṣaṇa n. ʻ tugging, ploughing, hurting ʼ Mn., ʻ cultivated land ʼ MBh. [kárṣati, √kr̥ṣ] Pk. karisaṇa -- n. ʻ pulling, ploughing ʼ; G. karsaṇ n. ʻ cultivation, ploughing ʼ; OG. karasaṇī m. ʻ cultivator ʼ, G. karasṇī m. -- See *kr̥ṣaṇa -- .(CDIAL 2907). Harosheth-hagoyim is the home of general Sisera, who was killed by Jael during the war of Naphtali and Zebulun against Jabin, king of Hazor in Canaan (Judges 4:2). The lead players of this war are the general Barak and the judge Deborah. The name Harosheth-hagoyim obviously consists of two parts. The first part is derived from the root , which HAW Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament treats as four separate roots (harash I, II, III, & IV). The verb (harash I) means to engrave or plough. HAW Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament reads, "The basic idea is cutting into some material, e.g. engraving metal or plowing soil." Derivatives of this verb are: (harash), meaning engraver; (haroshet) a noun meaning a carving. This word is equal to the first part of the name Harosheth-hagoyim; (harish), meaning plowing or plowing time; (maharesha) meaning ploughshare; (harishi), a word which is only used in Jona 4:8 to indicate a certain characteristic of the sun - vehement (King James) or scorching (NIV). The verb (harash II) most commonly denotes refraining from speech or response, either because one is deaf or mute, or because one doesn't want to respond. None of the sources indicates a relation with the previous root, and perhaps there is none, but on the other hand, perhaps deafness was regarded in Biblical as either being marked or else cut or cut off. The noun (horesh) from root (hrsh III) occurs only in Isaiah 17:9 and has to do with a wood or forest. The noun (heresh) from root (hrsh IV) occurs only in Isaiah 3:3 and probably means magical art or expert enchanter, or something along those lines. The second part of the name, hagoyim, comes from the definite article (ha plus the common word (goy) meaning nation, people, gentile. This word comes from the assumed root (gwh), which is not translated but which seems to denote things that are surpassed or left behind. Other derivatives are: (gaw a and gew), meaning back, as in "cast behind the back," i.e. put out of mind (1 Kings 14:9, Nehemiah 9:26, Isaiah 38:17); (gewiya), meaning body, either dead or alive (Genesis 47:18, Judges 14:8, Daniel 10:6). The meaning of the name Harosheth-hagoyim can be found as any combination of the above. NOBS Study Bible Name List reads Carving Of The Nations, but equally valid would be Silence Of The Gentiles or Engraving Of What's Abandoned. Jones' Dictionary of Old Testament Proper Names reads Manufactory for Harosheth and "of the Gentiles" for Hagoyim. http://www.abarim-publications.com/Meaning/Harosheth.html khar 5 ख््र्, in khara-ponzu ख््र-पं&above;जु&below; । म्लिष्टरेखाः unmeaning scrawls in imitation of writing, made by untaught children, or the like.(Kashmiri)khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta खार-बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü -ब&above;ठू&below; । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy -बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru -द्वकुरु&below; । लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer. -gȧji -ग&above;जि&below; or -güjü -ग&above;जू&below; । लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. (sg. dat. -höjü -हा&above;जू&below;), a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl 5. -kūrü -कूरू&below; । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. -koṭu -क&above;टु&below; । लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. -küṭü -क&above;टू&below; । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më˘ʦü 1 -म्य&above;च&dotbelow;ू&below; । लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see [khāra 3] ), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore. -nĕcyuwu -न्यचिवु&below; । लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see [khārun] ), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ -च्&dotbelow;ञ । लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wān वान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil.(Kashmiri) Allograph: khāra 2 खार (= ) or khār 4 खार् (L.V. 96, K.Pr. 47, Śiv. 827) । द्वेषः m. (for 1, see [khār 1] ), a thorn, prickle, spine (K.Pr. 47; Śiv. 827, 153)(Kashmiri) खरोष्टी kharōṣṭī , 'A kind of alphabet; Lv.1.29'. Often, there is an alternative (perhaps, erroneous) transliteration as kharōṣṭhī. The compound is composed of: khar + ōṣṭī (or, उष्ट 'mfn. burnt' (CDIAL 2386); uṣṭa -- ʻ settled ʼ (CDIAL 2385) ṓṣṭha m. ʻ lip ʼ RV. Pa. oṭṭha -- m., Pk. oṭṭha -- , uṭ°, hoṭṭha -- , huṭ° m., Gy. pal. ōšt, eur. vušt m.; Ash. ọ̈̄ṣṭ, Wg. ṳ̄ṣṭ, wūṣṭ, Kt. yūṣṭ (prob. ← Ind. NTS xiii 232); Paš. lauṛ. ūṭh f. ← Ind. (?), gul. ūṣṭ ʻ lip ʼ, dar. weg. uṣṭ ʻ bank of a river ʼ (IIFL iii 3, 22); Kal. rumb. ūṣṭ, uṣṭ ʻ lip ʼ; Sh. ō̃ṭṷ m. ʻ upper lip ʼ, ō̃ṭi̯ f. ʻ lower lip ʼ (→ Ḍ ōṭe pl.); K. wuṭh, dat. °ṭhas m. ʻ lip ʼ; L. hoṭh m., P. hoṭh, hõṭh m., WPah. bhal. oṭh m., jaun. hōṭh, Ku. ū̃ṭh, gng. ōṭh, N. oṭh, A. ō̃ṭh, MB. Or. oṭha, Mth. Bhoj. oṭh, Aw. lakh. ō̃ṭh, hō̃ṭh, H. oṭh, õṭh, hoṭh, hõṭhm., G. oṭh, hoṭh m., M. oṭh, õṭh, hoṭ m., Si. oṭa.WPah.poet. oṭhḷu m. ʻ lip ʼ, hoṭṛu, kṭg. hóṭṭh, kc. ōṭh, Garh. hoṭh, hō̃ṭ. (CDIAL 2563). In the context of use of the term kharōṣṭī for a writing system, it is apposite to interpret the compound as composed of khar + ōṣṭī 'blacksmith + lip'. "The Kharosti scrolls, the oldest collection of Buddhist manuscripts in the world, are radiocarbon-dated by the Australian Nuclear Science and Technology Organisation (ANSTO). The group confirms the initial dating of the Senior manuscripts to 130-250 CE and the Schøyen manuscripts to between the 1st and 5th centuries CE." http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/2006_in_archaeology "The Kharoṣṭhī script is an ancient Indic script used by the Gandhara culture of ancient Northwest South Asia(primarily modern-day Afghanistan and Pakistan) to write the Gāndhārī language (a dialect of Prakrit) and theSanskrit language. An abugida (or "alphasyllabary"), it was in use from the middle of the 3rd century BCE until it died out in its homeland around the 3rd century CE. It was also in use in Kushan, Sogdiana (see Issyk kurgan) and along the Silk Road where there is some evidence it may have survived until the 7th century in the remote way stations of Khotan and Niya...As preserved in Sanskrit documents the alphabet runs: a ra pa ca na la da ba ḍa ṣa va ta ya ṣṭa ka sa ma ga stha ja śva dha śa kha kṣa sta jñā rtha (or ha) bha cha sma hva tsa gha ṭha ṇa pha ska ysa śca ṭa ḍha ...![]()

Kharoshti Script

A brief essay

The Kharoshti language was introduced into Gandhara - Afghanistan and the North-west frontiers of India during the early part of the 5th century BCE as a result of Achaemenian conquests eastwards4. The language and script, it seems, became refined with time but it was ultimately overtaken by the much older language of the region, Brahmi and it became extinct by about the middle (c. 300-350 CE) of the Sassanian Dynasty (which lasted c.224 to 641 CE). It certainly differed from all other Indic scripts in that it retained the Semitic characteristic of being written from right to left. After all it was derived from its north Semitic parent, Aramaic, like Pahlavi was. Yet it retained the distinct Indian ways - in the use of the consonants, double consonants and the vowels.

|

Kuninda coin composite Obverse: Brahmi script Reverse: Kharoshti script (Click to enlarge) |

Sanskrit in Brahmi script slowly gave place to Prakrit in Devnagari script. As Brahmi progressed into the Devnagari group of Indic languages the Kharoshti script gradually died out about c. 305-325 CE. There was some overlap of the scripts on coins as Satraps vied with the suzerain Kings and usurped their Satrapy as an autonomous kingdom.

The coins showing the Greek divinities5 - Zeus (holding a thunderbolt and/or a sceptre), Hercules (usually holding a club and/or lion skin), Nike (usually winged, City divinity holding cornucopia), Artemis drawing arrow from bow, Helios (Sun), Selene (Moon) and the Indo-Iranian divinities: Mozao Oaho or Mazdaonho (Ahura Mazda), Athasho (Fire), Bago (Bhaga), Miiro/ Mioro (Sun/Mithra), Ardoksho (Earth), Orlango (Verethaghna), Saorhora (Sherewar, Mao (Moon), Apto/Appo (Waters), Vado (Wind), Pharro (Aura /Khwarena), Manaobago (Vohu Manah), Boddo (Buddha), sometimes a humped Indian bull or an elephant or the two-humped Bactrian camel on the reverse......etc were slowly replaced by the standing Shiva (holding a trident or a club) in front of a bull, Parvati (consort of Shiva) seated on a lion, Lakshmi (representing wealth) seated or standing on a lotus, Peacock motif…..etc. The coins were minted mainly in Balkh, Merv, Herat, Pushkalavati (near modern Kabul), Takhshashilla (modern Taxila), Baamiyan, Jammu….etc.

Kharoshti script and changes of regimes in Gandhara and and surrounding regions

Graeco-Bactrian Period: (c. 250-174 BCE)3The history begins circa 250 BCE when the Indo-Greeks in Bactria revolted against their Seleucid masters and formed an autonomous empire free from the suzerainty of an overlord. It was led by Diodotus I (c. 250-230 BCE) with his son, Diodotus II (c. 250-230 BCE) usurped the Eastern Satraps, Sughda and Margiana from the Suzerain King Seleucus I Nikator (ruled c.313-281 BCE), who was himself assassinated. The Graeco-Bactrians had only the Greek legend on both sides of their coins. The Kharoshti script on coins was not in use during this period, which ended in 174 BCE.

Indo-Greek (Yonas, word for Ionians) Period: (c.174 BCE-10 CE) 3

Commencing with Apollodotus I (c.174-165 BCE) and ending with Strato II (ruled with Strato III c. 25 BCE -10 CE in North Afghanistan) coins were minted with the Greek legend on the obverse and the Kharoshti script on the reverse.

Demetrius (at first associated with his father c.205-190 BCE and then by himself c.190-166 BCE) ruling further east and in Arachosia (South Afghanistan) also minted bilingual coins, with Kharoshti on the Reverse (MAHARAJaSa APaRaJITaSa DEMETRIYaSa) and Greek on the Obverse (Invincible King Demetrius). This could have occurred only if Kharoshti was then a common spoken language among a large population in these regions. The script on the coins was Kharoshti throughout the Indo-Greek period.

Indo-Scythian Period: (c.10 CE-130 CE) 3The Indo-Scythians were a branch of the Sakas from central Asia. Overlapping the Indo-Greeks they had initially settled in the west Afghan plateau of Drangiana, calling it ‘Sakastan’. About 10 CE the Indo-Scythian King Rajuvula, a minor Satrap in Mathura defeated and dethroned Strato III. Around 80 CE they moved eastwards to overtake South Afghanistan. In previous times the Indo-Scythian king Maues had already occupied Gandhara and Taxila (improperly dated around 80 BCE), but his kingdom disintegrated upon his death and the Indo-Greeks had prospered again for a while, as suggested by the coinage of kings Apollodotus II(c.110-80 BCE) and Hippostratos (c.90-60 BCE), until the Saka King Azes Ipermanently established Indo-Scythian rule in the northwest in 60 BCE. They too minted coins with the Greek legend on the obverse and the Kharoshti script on the reverse of their coins. The Yueh-chi / Yuehzhi (Kushans from western China) Period: (c.135-350 BCE) 3The Yueh-chi were a nomadic confederation of five tribes that originally lived near the border of China. They came from the Tarim Basin region, which is a part of what is now Gansu and Xinjiang provinces. They encountered severe problems with the Hsiung-nu (White Huns; later called Hephthalites) in the years 176-160 B.C. After suffering two major defeats by the Huns, the Yueh-chi decided to move west and then south. Their decision to migrate affected the course of history. When they moved south, some Turkic tribes went with them. The Turkic people had also encountered problems with the Huns. They moved into an area north of the Oxus in what is now Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan and displaced a branch of the Scythians called the Sakas. By about 135 B.C., the Yue-chi and their Turkic allies had reached Bactria, a region that included parts of North West Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Greek dynasties of the Seleucids and Greco-Bactrians had ruled it for a long time. The Yueh-chi were able to eventually gain control of Bactria. They had driven out the last nomadic Indo-Greek king, Heliocles I (c. 135-110 BCE).

The later Kushans called themselves the Kushano-Sassanians 230-271 CE and Kushanshahs 271-350 CE. Depending on the affiliation to the Sassanians or Kushans their coins had only the Pahlavi or Greek script. They thrived roughly up to the middle of the Sassanian rule (about 350 CE). The Nahapana Satraps of the Sassanian era, who ruled in India as far south as Kutch, Gujarat and Saurashtra, however, had coins minted with trilingual scripts - Greek, Brahmi and Kharoshti.

There was also a short rule of the Indo-Parthians in a limited region (c. 78-124 CE). Both groups minted coins with the Greek legend on the obverse and the Kharoshti script on the reverse of their coins. This second wave of ‘Indo-Parthians’ moved eastwards into the Kabul Valley and present Pakistan c. 20 CE led by ‘Gondophores’ taking over from the Kushan King, Kujula Kadophises. Gondophores has been mentioned in the manuscripts “Actae Thomae” as the ‘King, Guduphara’ who had met Saint Thomas, the Apostle on his journey to South India. Christianity had been established in India 500 years before the early Christian Portuguese missionaries c.1522 came with their dreams of the colonializing of India. The missionaries were surprised at seeing huts and buildings with a cross atop in the Malabar coastal region of the present State of Kerala. The region was recaptured from the Indo-Parthians by the Kushans, possibly by Soter Megas c.45-90 CE. The Kharoshti script was no longer seen on any of the coins. It was replaced by the Brahmi script, which was now written and read from left to right (although, it seems from an isolated document that the earliest Brahmi script 3rd Century BCE was written from right to left). He was succeeded by Kadophises II 120 CE.

By the time of Kanishka I, the greatest of the Kushan kings (the exact dates of his 23-27 years of rule are under dispute) his kingdom included Kashmir, Khotan and Kashgar and Yarkand The last three were Chinese dependencies in the Tarim Basin, modern Xinjiang. His vast kingdom extended from Bukhara in the west to Sarnath in India, with Peshawar as the Capital) the coins in the Brahmi script showed the images and/or inscriptions of Boddo (Buddha), (Oisho) Shiva holding a trident near a bull (Nandi), Mihira/Miira (Mithra), Athro (Atar), Varahran (Verethragna), Mao (Moon), Appo (Water), Aodo (Vata). The appearance of the Avestan divinities was attributed to the fact that the Sassanian King, Hormazd II (303-309 CE) had earlier married the daughter of a Kushan king in Gandhara. Thereafter, Ardochso (Lakshmi), the consort of Vishnu remained a standard diety and was absorbed into the first Gupta Empire of Chandra Gupta (305-325 CE). His grandfather, Shrigupta (c 270-290 CE) ruling as ‘Maharaja’ of a small principality was the real founder of the Gupta Dynasty. Then, all traces of the Iranian influence have been found absent from the coins.

With regular revolts against the suzerain King there was some overlap of dynasties as kingdoms were lost and regained for short periods. Some tribal States - the Audumbara and the Kuninda (c. 150-100 BCE), used Kharoshti on one side of their coins and Brahmi on the other side. Indeed, the Audumbara tribal kings Dharagosa and Rudravarma were credited as being the first to introduce the Brahmi script on one side with the Kharoshti script on the other side of their coins. The neighbouring States soon followed. Most Kuninda coins have been found in hoards north of a line between Ambala and Saharanpur. There were also some even with trilingual inscriptions - Greek, Brahmi and Kharoshti. The Kuninda Kings followed the practice.