That the hieroglyph of pot/vase overflowing with water is a recurring theme can be seen from other cylinder seals, including Ibni-Sharrum cylinder seal. Such an imagery also occurs on a fragment of a stele, showing part of a lion and vases.

காண்டம்² kāṇṭam, n. < காண்டம்² kāṇṭam n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர். துருத்திவா யதுக்கிய குங்குமக் காண் டமும் (கல்லா. 49, 16).. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர். துருத்திவா யதுக்கிய குங்குமக் காண் டமும் (கல்லா. 49, 16) (Tamil) Rebus: khāṇḍa ‘tools, weapons, vessels’ (Marathi) [Note: On some of the Ancient Near East cylinder seal representations, the flowing water, overflowing pot are augmented by swimming fish, suggesting that ‘fish’ hieroglyph should also be taken as part of the message: ayo, aya ‘fish’ rebus: aya ‘iron’ ayas ‘metal’]

![]()

m1656 Mohenjodro Pectoral. Carnelian. kanda kanka ‘rim of pot’ (Santali) rebus: kanda ‘fire-altar’khaNDa ‘implements’ PLUS karNaka ‘rim of jar’ rebus: karNi ‘Supercargo, scribe’ PLUS semantic determinant: kANDa ‘water’ rebus: khaNDa ‘implements’. In the context of semantics of karNi ‘supercargo’, it is possible to decipher the standard device sangaDa ‘lathe’ rebus: jangada ‘double-canoe’ as a seafaring merchant vessel. The suffix -karnika signifies a ‘maker’. Kāraṇika [der. fr. prec.] the meaning ought to be “one who is under a certain obligation” or “one who dispenses certain obligations.” In usu˚ S ii.257 however used simply in the sense of making: arrow — maker, fletcher (Pali). kāraṇika m. ʻ teacher ʼ MBh., ʻ judge ʼ Pañcat. [kā- raṇa — ]Pa. usu — kāraṇika — m. ʻ arrow — maker ʼ; Pk. kāraṇiya — m. ʻ teacher of Nyāya ʼ; S. kāriṇī m. ʻ guardian, heir ʼ; N. kārani ʻ abettor in crime ʼ; M. kārṇī m. ʻ prime minister, supercargo of a ship ʼ, kul — karṇī m. ʻ village accountant ʼ.

(CDIAL 3058) “Fletching (also known as a flight or feather) is the aerodynamic stabilization of arrows or darts with materials such as feathers, each piece of which is referred to as a fletch. A fletcher is a person who attaches the fletching.The word is related to the French word flèche, meaning “arrow”, via Old French; the ultimate root is Frankish fliukka.” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/FletchingPerhaps the reading should be ˚kāraka. (Pali) Similarly, khaNDa Kāraṇika can be semantically explained as ‘implements maker’. The pectoral thus signifies the profession of an implements-maker and a supercargo, merchant’s representative on the merchant vessel taking charge of the cargo and the trade of the cargo.

Hieroglyph: sãghāṛɔ ‘lathe’.(Gujarati).Rebus: Vajra Sanghāta ‘binding together’ (Varahamihira) *saṁgaḍha ʻ collection of forts ʼ. [*gaḍha — ]L. sãgaṛh m. ʻ line of entrenchments, stone walls for defence ʼ.(CDIAL 12845). సంగడము (p. 1279) [ saṅgaḍamu ] A raft or boat made of two canoes fastened side by side. రెండుతాటి. బొండులు జతగాకట్టినతెప్ప சங்கடம்² caṅkaṭam, n. < Port. jangada. Ferry-boat of two canoes with a platform thereon; இரட்டைத்தோணி. (J.) G. sãghāṛɔ m. ʻ lathe ʼ; M. sãgaḍ f. ʻ a body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together, part of a turner’s apparatus ʼ, m.f. ʻ float made of two canoes joined together ʼsaṁghāṭa m. ʻ fitting and joining of timber ʼ R. [√ghaṭ] LM 417 compares saggarai at Limurike in the Periplus, Tam. śaṅgaḍam, Tu. jaṅgala ʻ double — canoe ʼ),sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ lathe ʼ; Si. san̆gaḷa ʻ pair ʼ, han̆guḷa, an̆g° ʻ double canoe, raft ʼ.(CDIAL 12859) Cangavāra [cp. Tamil canguvaḍa a dhoney, Anglo– Ind. ḍoni, a canoe hollowed from a log, see also doṇi] a hollow vessel, a bowl, cask M i.142; J v.186 (Pali)

Hieroglyph: खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. खोंडरूं [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा-cowl (Marathi. Molesworth); kōḍe dūḍa bull calf (Telugu); kōṛe ‘young bullock’ (Konda)Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) Rebus: kundaṇa pure gold (Tulu)

kāṇḍam காண்டம்² kāṇṭam, n. < kāṇḍa. 1. Water; sacred water; நீர். துருத்திவா யதுக்கிய குங்குமக் காண் டமும் (கல்லா. 49, 16). Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘metal tools, pots and pans’ (Marathi) (B) {V} “(pot, etc.) to ^overflow”. See `to be left over’. @B24310. #20851. Re(B) {V} “(pot, etc.) to ^overflow”. See`to be left over’. (Munda ) Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi) The hieroglyph clearly refers to the metal tools, pots and pans of copper.

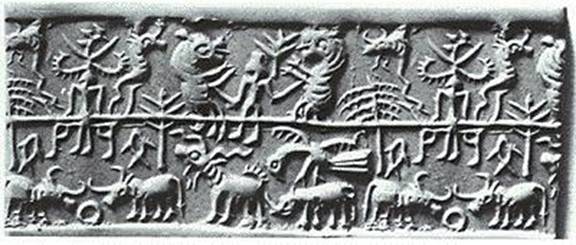

Some examples of ‘overflowing pot’ metaphors on Ancient Near East artifacts, cylinder seals:

![]()

I suggest that together with the adaptation of Egyptian hieroglyphs, the Indus Script hypertexts were also adapted and absorbed into Ancient Near East glyptics to signify wealth creation by metalwork of Meluhha artisans.

Fig. 11.4 shows both on a Syrian dynastic seal and on a Syrian seal signifying a Canaanite goddess a common hieroglyph: an ankh (/ˈæŋk/ or /ˈɑːŋk/; Egyptian ˁnḫ), also known as crux ansata (the Latin for “cross with a handle”) is an ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic ideograph symbolizing “life”. It should be noted that the Syrian seal which shows the ankh upside down also includes two Indus Script hypertext hieroglyphs: 1. twisted rope at the bottom rgister of the seal; 2. overflowing water pot. These two hieroglyphs are read rebus in Indus Script cipher:

1. Twisted rope: मेढा [ mēḍhā ] ‘a curl or snarl; twist in thread’ rebus: med ‘iron’ med ‘copper’ (Slavic) medhā ‘dhana, yajña’.

2. Overflowing water pot: lo ‘overfowing pot’ rebus: loh ‘copper’ PLUS kāṇḍa ‘water’ rebus: kāṇḍā ‘implements’ Thus, together the expression is lokhaṇḍa ‘ metal implements’.

![]()

Chlorite vessel found at Khafajeh: Ht 11.5 cm. 2,600 BCE, Khafajeh, north-east of Baghdad (Photo from pg. 69 of D. Collon’s 1995 Ancient Near Eastern Art).

Impression of seal on tablets from Kanesh (After Larsen, Mogens Trolle and Moller Eva, Five old Assyrian texts, in: D. Charpin – Joannès F. (ed.), Marchands, Diplomates et Empereurs. Études sur la civilization Mésopotamienne offertes à Paul Garelli (Éditions research sur les Civilisations), Paris, 1991, pp. 214-245: figs. 5,6 and 10.)

Timber and exotic stones to decorate the temples were brought from the distant lands of Magan and Meluhha (possibly to be identified as Oman and the Indus Valley).

Gudea Basin. Water overflowing from vases. : The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler … By Claudia E. Suter “The standing statue N (Fig. 5) holds a vase from which four streams of water flow down on each side of the dress into identical vases depicted on the pedestal, which are equally overflowing with water. Little fish swim up the streams to the vase held by Gudea. This statue evidently shows the ruler in possession of prosperity symbolized by the overflowing vase.” (p.58)ayo ‘fish’ (Munda) Rebus: ayo ‘iron’ (Gujarati); ayas‘metal’ (Skt.) Together with lo, ‘overflow’, the compound word can be read as loh+ayas. The compound lohāyas is attested in ancient Indian texts, contrasted withkṛṣṇāyas, distinguishing red alloy metal (bronze) from black alloy metal (iron alloy). ayaskāṇḍa is a compound attested in Pāṇini; the word may be semantically explained as ‘metal tools, pots and pans’ or as alloyed metal.

![]() Workers from Elam, Susa, Magan and Meluhha were deployed by Gudea, the ruler of Lagaṣ, to build The Eninnu, the main temple of Girsu, c. 2125 BCE. We are dealing with Indian sprachbundwhen we refer to Meluhha. This sprachbund has a remarkable lexeme which is used to signify a smithy, as also a temple: Kota. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. Toda. kwala·l Kota smithy Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer; Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133).

Workers from Elam, Susa, Magan and Meluhha were deployed by Gudea, the ruler of Lagaṣ, to build The Eninnu, the main temple of Girsu, c. 2125 BCE. We are dealing with Indian sprachbundwhen we refer to Meluhha. This sprachbund has a remarkable lexeme which is used to signify a smithy, as also a temple: Kota. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. Toda. kwala·l Kota smithy Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer; Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133).![]()

Gudea Basin. Water overflowing from vases. : The Representation of an Early Mesopotamian Ruler … By Claudia E. Suter “The standing statue N (Fig. 5) holds a vase from which four streams of water flow down on each side of the dress into identical vases depicted on the pedestal, which are equally overflowing with water. Little fish swim up the streams to the vase held by Gudea. This statue evidently shows the ruler in possession of prosperity symbolized by the overflowing vase.” (p.58)ayo ‘fish’ (Munda) Rebus: ayo ‘iron’ (Gujarati); ayas‘metal’ (Skt.) Together with lo, ‘overflow’, the compound word can be read as loh+ayas. The compound lohāyas is attested in ancient Indian texts, contrasted withkṛṣṇāyas, distinguishing red alloy metal (bronze) from black alloy metal (iron alloy). ayaskāṇḍa is a compound attested in Pāṇini; the word may be semantically explained as ‘metal tools, pots and pans’ or as alloyed metal.

![]()

![]() Cylinder seal explained as Enki seated on a throne with a flowing stream full of fish, ca. 2250 BCE

Cylinder seal explained as Enki seated on a throne with a flowing stream full of fish, ca. 2250 BCE

(BM 103317).British Museum.

meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)

![]()

![]() 2605 (#KJ Roach’s thesis). Sealed tablet. Susa. Illituram, son of Il-mishar, servant of Pala-isshan

2605 (#KJ Roach’s thesis). Sealed tablet. Susa. Illituram, son of Il-mishar, servant of Pala-isshan![]() #KJ Roach M9 Mesopotamia

#KJ Roach M9 Mesopotamia![]() #Roach 2168 Cream limestone. Susa.

#Roach 2168 Cream limestone. Susa.![]() A person with a vase with overflowing water; sun sign. C. 18th cent. BCE. [E. Porada,1971, Remarks on seals found in the Gulf states, Artibus Asiae, 33, 31-7

A person with a vase with overflowing water; sun sign. C. 18th cent. BCE. [E. Porada,1971, Remarks on seals found in the Gulf states, Artibus Asiae, 33, 31-7![]() The seal of Gudea: Gudea, with shaven head, is accompanied by a minor female diety. He is led by his personal god, Ningishzida, into the presence of Enlil, the chief Sumerian god. Wind pours forth from of the jars held by Enlil, signifying that he is the god of the winds. The winged leopard (griffin) is a mythological creature associated with Ningishzida, The horned helmets, worn even by the griffins, indicates divine status (the more horns the higher the rank). The writing in the background translates as: “Gudea, Ensi [ruler], of Lagash”. lōī f., lo m.2. Pr. ẓūwī ʻfoxʼ (Western Pahari)(CDIAL 11140-2). Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi). Te. eṟaka, ṟekka, rekka, neṟaka, neṟi id. (DEDR 2591). Rebus: eraka, eṟaka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); urukku (Ta.); urukka melting; urukku what is melted; fused metal (Ma.); urukku (Ta.Ma.); eragu = to melt; molten state, fusion; erakaddu = any cast thng; erake hoyi = to pour meltted metal into a mould, to cast (Kannada)

The seal of Gudea: Gudea, with shaven head, is accompanied by a minor female diety. He is led by his personal god, Ningishzida, into the presence of Enlil, the chief Sumerian god. Wind pours forth from of the jars held by Enlil, signifying that he is the god of the winds. The winged leopard (griffin) is a mythological creature associated with Ningishzida, The horned helmets, worn even by the griffins, indicates divine status (the more horns the higher the rank). The writing in the background translates as: “Gudea, Ensi [ruler], of Lagash”. lōī f., lo m.2. Pr. ẓūwī ʻfoxʼ (Western Pahari)(CDIAL 11140-2). Rebus: loh ‘copper’ (Hindi). Te. eṟaka, ṟekka, rekka, neṟaka, neṟi id. (DEDR 2591). Rebus: eraka, eṟaka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); urukku (Ta.); urukka melting; urukku what is melted; fused metal (Ma.); urukku (Ta.Ma.); eragu = to melt; molten state, fusion; erakaddu = any cast thng; erake hoyi = to pour meltted metal into a mould, to cast (Kannada)Gudea’s link with Meluhha is clear from the elaborate texts on the two cylinders describing the construction of the Ninĝirsu temple in Lagash. An excerpt: 1143-1154. Along with copper, tin, slabs of lapis lazuli, refined silver and pure Meluḫa cornelian, he set up (?) huge copper cauldrons, huge …… of copper, shining copper goblets and shining copper jars worthy of An, for laying (?) a holy table in the open air …… at the place of regular offerings (?). Ninĝirsu gave his city, Lagaš

Location.Current Repository

Inscription on base of skirt- God commands him to build house. Gudea is holding plans. Gudea depicted as strong, peaceful ruler. Vessel flowing with life-giving water w/ fish. Text on garment dedicates himself, the statue, and its temple to the goddess Geshtinanna.

According to the inscription this statue was made by Gudea, ruler of Lagash (c. 2100 BCE) for the temple of the goddess Geshtinanna. Gudea refurbished the temples of Girsu and 11 statues of him have been found in excavations at the site. Nine others including this one were sold on the art market. It has been suggested that this statue is a forgery. Unlike the hard diorite of the excavated statues, it is made of soft calcite, and shows a ruler with a flowing vase which elsewhere in Mesopotamian art is only held by gods. It also differs stylistically from the excavated statues. On the other hand, the Sumerian inscription appears to be genuine and would be very difficult to fake. Statues of Gudea show him standing or sitting. Ine one, he rests on his knee a plan of the temple he is building. On some statues Gudea has a shaven head, while on others like this one he wears a headdress covered with spirals, probably indicating that it was made out of fur. Height 61 cm. The overflowing water from the vase is a hieroglyph comparable to the pectoral of Mohenjo-daro showing an overflowing pot together with a one-horned young bull and standard device in front. The diorite from Magan (Oman), and timber from Dilmun (Bahrain) obtained by Gudea could have come from Meluhha.

- he has constructed.

- By the power of the goddessNinâ,

- by the power of the godNin-girsu,

- to Gudea

- who has endowed with the sceptre

- the godNin-girsu,

- the country ofMâgan, 1

- the country ofMelughgha,

- the country ofGubi, 2

- and the country ofNituk, 3

- which possess every kind of tree,

- vessels laden with trees of all sorts

- intoShirpurla

- have sent.

- From the mountains of the land ofMâgan

- a rare stone he has caused to come;

- for his statue

- http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/rp/rp202/rp20221.htm#fr_228

![]() Sumerian sign for the term ZAG ‘purified precious’. The ingot had a hole running through its length Perhaps a carrying rod was inserted through this hole.

Sumerian sign for the term ZAG ‘purified precious’. The ingot had a hole running through its length Perhaps a carrying rod was inserted through this hole.Glyph: ḍhol ‘a drum beaten on one end by a stick and on the other by the hand’ (Santali); ḍhol ‘drum’ (Nahali); dhol (Kurku); ḍhol (Hi.) dhol a drum (G.)(CDIAL 5608) డోలు [ḍōlu ] [Tel.] n. A drum. Rebus: dul ‘to cast in a mould’; dul mẽṛhẽt, dul meṛeḍ, dul; koṭe meṛeḍ ‘forged iron’ (Santali) WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ḍhōˋḷ m. ʻstoneʼ, kṭg. ḍhòḷṭɔ m. ʻbig stone or boulderʼ, ḍhòḷṭu ʻsmall id.ʼ Him.I 87.(CDIAL 5536).

Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023). Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ)

![]() Cylinder seal with kneeling nude heroes, ca. 2220–2159 b.c.; Akkadian Mesopotamia Red jasper H. 1 1/8 in. (2.8 cm), Diam. 5/8 in. (1.6 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art – USA

Cylinder seal with kneeling nude heroes, ca. 2220–2159 b.c.; Akkadian Mesopotamia Red jasper H. 1 1/8 in. (2.8 cm), Diam. 5/8 in. (1.6 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art – USAFour flag-posts(reeds) with rings on top held by the kneeling persons define the four components of the iron smithy/forge. This is an announcement of four shops, पेढी (Gujarati. Marathi). पेंढें ‘rings’ Rebus: पेढी ‘shop’.āra ‘serpent’ Rebus; āra ‘brass’. karaḍa ‘double-drum’ Rebus: karaḍa ‘hard alloy’.

Specific materials offered for sale/exchange in the shop are: hard alloy brass metal (ayo, fish); lokhaṇḍ (overflowing pot) ‘metal tools, pots and pans, metalware’; arka/erka ‘copper’; kammaṭa (a portable furnace for melting precious metals) ‘coiner, mint’ Thus, the four shops are: 1. brass alloys, 2. metalware, 3. copper and 4. mint (services).

erãguḍu bowing, salutation (Telugu) iṟai (-v-, -nt-) to bow before (as in salutation), worship (Tamil)(DEDR 516). Rebus: eraka, eṟaka any metal infusion (Kannada.Tulu) eruvai ‘copper’ (Tamil); ere dark red (Kannada)(DEDR 446).

puṭa Anything folded or doubled so as to form a cup or concavity; crucible. Alternative: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)

Allograph: ढाल [ ḍhāla ] f (S through H) The grand flag of an army directing its march and encampments: also the standard or banner of a chieftain: also a flag flying on forts &c. ढालकाठी [ ḍhālakāṭhī ] f ढालखांब m A flagstaff; esp.the pole for a grand flag or standard. 2 fig. The leading and sustaining member of a household or other commonwealth. 5583 ḍhāla n. ʻ shield ʼ lex. 2. *ḍhāllā — . 1. Tir. (Leech) “dàl” ʻ shield ʼ, Bshk. ḍāl, Ku. ḍhāl, gng. ḍhāw, N. A. B. ḍhāl, Or. ḍhāḷa, Mth. H. ḍhāl m.2. Sh. ḍal (pl. °le̯) f., K. ḍāl f., S. ḍhāla, L. ḍhāl (pl. °lã) f., P. ḍhāl f., G. M. ḍhāl f. WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ḍhāˋl f. (obl. — a) ʻ shield ʼ (a word used in salutation), J. ḍhāl f. (CDIAL 5583).

They are four Glyphs: paṭākā ‘flag’ Rebus: pāṭaka, four quarters of the village.

kã̄ḍ reed Rebus: kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

- Pk. kamaḍha— , °aya— m. ʻ bamboo ʼ; Bhoj. kōro ʻ bamboo poles ʼ. 2. N. kāmro ʻ bamboo, lath, piece of wood ʼ, OAw. kāṁvari ʻ bamboo pole with slings at each end for carrying things ʼ, H. kã̄waṛ, °ar, kāwaṛ, °ar f., G. kāvaṛf., M. kāvaḍ f.; — deriv. Pk. kāvaḍia — , kavvāḍia — m. ʻ one who carries a yoke ʼ, H. kã̄waṛī, °ṛiyā m., G. kāvaṛiyɔ m. 3. S. kāvāṭhī f. ʻ carrying pole ʼ, kāvāṭhyo m. ʻ the man who carries it ʼ. 4. Or. kāmaṛā, °muṛā ʻ rafters of a thatched house ʼ; G. kāmṛũ n., °ṛī f. ʻ chip of bamboo ʼ, kāmaṛ — koṭiyũ n. ʻ bamboo hut ʼ. 5. B. kāmṭhā ʻ bow ʼ, G. kāmṭhũ n., °ṭhī f. ʻ bow ʼ; M. kamṭhā, °ṭā m. ʻ bow of bamboo or horn ʼ; — deriv. G. kāmṭhiyɔ m. ʻ archer ʼ. 6. A. kabāri ʻ flat piece of bamboo used in smoothing an earthen image ʼ. 7. kã̄bīṭ, °baṭ, °bṭī, kāmīṭ, °maṭ, °mṭī, kāmṭhī, kāmāṭhī f. ʻ split piece of bamboo &c., lath ʼ.(CDIAL 2760). kambi f. ʻ branch or shoot of bamboo ʼ lex. Pk. kaṁbi — , °bī — , °bā — f. ʻ stick, twig ʼ, OG. kāṁba; M. kã̄b f. ʻ longitudinal division of a bamboo &c., bar of iron or other metal ʼ. (CDIAL 2774). कंबडी [ kambaḍī ] f A slip or split piece (of a bamboo &c.)(Marathi)

The rings atop the reed standard: पेंढें [ pēṇḍhēṃ ] पेंडकें [ pēṇḍakēṃ ] n Weaver’s term. A cord-loop or metal ring (as attached to the गुलडा of the बैली and to certain other fixtures). पेंडें [ pēṇḍēṃ ] n (पेड) A necklace composed of strings of pearls. 2 A loop or ring. Rebus: पेढी (Gujaráthí word.) A shop (Marathi) Alternative: koṭiyum [koṭ, koṭī neck] a wooden circle put round the neck of an animal (Gujarati) Rebus: ācāri koṭṭya = forge, kammārasāle (Tulu)

![]() The four hieroglyphs define the four quarters of the village smithy/forge: alloy, metalware, turner’s lathe-work, cruble (or, ingot).

The four hieroglyphs define the four quarters of the village smithy/forge: alloy, metalware, turner’s lathe-work, cruble (or, ingot).ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo ‘metal, alloy’

కాండము [ kāṇḍamu ] kānḍamu. [Skt.] n. Water. నీళ్లు (Telugu) kaṇṭhá — : (b) ʻ water — channel ʼ: Paš. kaṭāˊ ʻ irrigation channel ʼ, Shum. xãṭṭä. (CDIAL 14349).

lokhãḍ ‘overflowing pot’ Rebus: ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ (Gujarati)

arká1 m. ʻ flash, ray, sun ʼ RV. [√arc] Pa. Pk. akka — m. ʻ sun ʼ, Mth. āk; Si. aka ʻ lightning ʼ, inscr. vid — äki ʻ lightning flash ʼ.(CDIAL 624) அருக்கன் arukkaṉ, n. < arka. Sun; சூரி யன். அருக்க னணிநிறமுங் கண்டேன் (திவ். இயற். 3, 1).(Tamil) agasāle ‘goldsmithy’ (Kannada) అగసాలి [ agasāli ] or అగసాలెవాడు agasāli. n. A goldsmith. కంసాలివాడు. (Telugu) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada) cf. eruvai = copper (Tamil) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tulu) Rebus: eraka = copper (Ka.) eruvai = copper (Ta.); ere – a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a = syn. erka, copper, weapons (Ka.) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada) akka, aka (Tadbhava of arka) metal; akka metal (Te.) arka = copper (Skt.) erako molten cast (Tulu)

Alternative: kunda ‘jasmine flower’ Rebus: kunda ʻa turner’s latheʼ. kundaṇa pure gold.

The image could denote a crucible or a portable furnace: kammaṭa ‘coiner, mint, a portable furnace for melting precious metals (Telugu) On some cylinder seals, this image is shown held aloft on a stick, comparable to the bottom register of the ‘standard device’ normally shown in front of a one-horned young bull. Alternatives: puṭa Anything folded or doubled so as to form a cup or concavity; crucible. Ta. kuvai, kukai crucible. Ma. kuva id. Ka. kōve id. Tu. kōvè id., mould. (DEDR 1816). Alternative: Shape of ingot: దళము [daḷamu] daḷamu. [Skt.] n. A leaf. ఆకు. A petal. A part, భాగము. dala n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ MBh. Pa. Pk. dala — n. ʻ leaf, petal ʼ, G. M. daḷ n.(CDIAL 6214). <DaLO>(MP) {N} “^branch, ^twig”. *Kh.<DaoRa>(D) `dry leaves when fallen’, ~<daura>, ~<dauRa> `twig’, Sa.<DAr>, Mu.<Dar>, ~<Dara> `big branch of a tree’, ~<DauRa> `a twig or small branch with fresh leaves on it’, So.<kOn-da:ra:-n> `branch’, H.<DalA>, B.<DalO>, O.<DaLO>, Pk.<DAlA>. %7811. #7741.(Munda etyma) Rebus: ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati).

![]() A baked-clay plaque from Ur, Iraq, portraying a goddess; she holds a vase overflowing with water (‘hé-gál’ or ‘hegallu’) is a symbol of abundance and prosperity. (Beijing World Art Museum) Fish in water on statue, on viewer’s right. Gudea’s Temple Building “The goddesses with overflowing vases. (Fig.8). The large limestone basin (SV.7) restored by Unger from twenty-six fragments is carved in relief on its outside. It shows a row of goddesses walking on a stream of water. Between them they are holding vases from which water flows down into the stream. These, in turn, are fed with water poured from vases which are held by smaller-scale goddesses hovering above. All goddesses wear long pleated dresses, and crowns with a single horn pair. There are remains of at least six standing and four hovering goddesses. Considering the importance the number seven plays in Gudea’s inscriptions, Unger’s reconstruction of seven goddesses of each type is credible. The inscription on the basin, which relates its fashioning, designates it as a large S’IM, a relatively rare and only vagueely understood term, perhaps to be read agarinX. The fashioning of one or more S’IM is also related in the Cylinder inscriptions, and the finished artifact is mentioned again in the description of the temple…Since the metaphor paraphrasing the basin refers to th ceaseless flow of water, it is possible that the basin(s) mentioned in the account of Eninnu’s construction is (are) identical with the fragmentary remains of the one (perhaps two?) actually found within the area of Gudea’s Eninnu, as Unger presumed. Several similar and somewhat intuitive identifications of the goddesses with the overflowing vases have been proposed: Heuzey saw personifications of the Euphrates and Tigris; Unger saw personifications of sources and rain clouds that form the Tigris and identified them with Ningirsu and Baba’s seven daughters; van Buren saw personifications of higher white clouds and lower rain clouds whom she assigned to Ea’s circle. Neither are the seven (not fourteen!) daughters of Ningirsu and Baba ever associated with water, nor can fourteen personified clouds be made out in Ea’s circle…The clue must be the overflowing vase which van Buren correctly interpreted as a symbol of abundance and prosperity. This interpretation is corroborated by the Gottertsypentext which states that the images of Kulullu is blessing with one hand (ikarrab) and holding abundance (HE.GAL) in the other. The protective spirit Kulullu is usually associated with abundance and divine benevolence, and may be reminiscent of the god bestowing the overflowing vase upon a human petititioner in much earlier presentation scenes. The narrative context in which the goddess with the overflowing vase occurs is confined to presentations of a human petititioner to a deity. The Akkadian seal fo the scribe Ili-Es’tar shows her accompanying the petitioner, not unlike a Lamma.

A baked-clay plaque from Ur, Iraq, portraying a goddess; she holds a vase overflowing with water (‘hé-gál’ or ‘hegallu’) is a symbol of abundance and prosperity. (Beijing World Art Museum) Fish in water on statue, on viewer’s right. Gudea’s Temple Building “The goddesses with overflowing vases. (Fig.8). The large limestone basin (SV.7) restored by Unger from twenty-six fragments is carved in relief on its outside. It shows a row of goddesses walking on a stream of water. Between them they are holding vases from which water flows down into the stream. These, in turn, are fed with water poured from vases which are held by smaller-scale goddesses hovering above. All goddesses wear long pleated dresses, and crowns with a single horn pair. There are remains of at least six standing and four hovering goddesses. Considering the importance the number seven plays in Gudea’s inscriptions, Unger’s reconstruction of seven goddesses of each type is credible. The inscription on the basin, which relates its fashioning, designates it as a large S’IM, a relatively rare and only vagueely understood term, perhaps to be read agarinX. The fashioning of one or more S’IM is also related in the Cylinder inscriptions, and the finished artifact is mentioned again in the description of the temple…Since the metaphor paraphrasing the basin refers to th ceaseless flow of water, it is possible that the basin(s) mentioned in the account of Eninnu’s construction is (are) identical with the fragmentary remains of the one (perhaps two?) actually found within the area of Gudea’s Eninnu, as Unger presumed. Several similar and somewhat intuitive identifications of the goddesses with the overflowing vases have been proposed: Heuzey saw personifications of the Euphrates and Tigris; Unger saw personifications of sources and rain clouds that form the Tigris and identified them with Ningirsu and Baba’s seven daughters; van Buren saw personifications of higher white clouds and lower rain clouds whom she assigned to Ea’s circle. Neither are the seven (not fourteen!) daughters of Ningirsu and Baba ever associated with water, nor can fourteen personified clouds be made out in Ea’s circle…The clue must be the overflowing vase which van Buren correctly interpreted as a symbol of abundance and prosperity. This interpretation is corroborated by the Gottertsypentext which states that the images of Kulullu is blessing with one hand (ikarrab) and holding abundance (HE.GAL) in the other. The protective spirit Kulullu is usually associated with abundance and divine benevolence, and may be reminiscent of the god bestowing the overflowing vase upon a human petititioner in much earlier presentation scenes. The narrative context in which the goddess with the overflowing vase occurs is confined to presentations of a human petititioner to a deity. The Akkadian seal fo the scribe Ili-Es’tar shows her accompanying the petitioner, not unlike a Lamma.![]() Enki walks out of the water to the land attended by his messenger, Isimud

Enki walks out of the water to the land attended by his messenger, Isimudwho is readily identifiable by his two faces looking in opposite directions (duality).

M177. Kidin-Marduk, son of Sha-ilima-damqa, the sha reshi official of Burnaburiash, king of the world Untash-Napirisha

![]() Cylinder seal image. The water-god in his sea house (Abzu) (ea. 2200 B.C.). On the extreme right is Enki, the water-god, enthroned in his sea house. To the left is Utu, the sun-god, with his rays and saw. The middle deity is unidentified. (British Museum)

Cylinder seal image. The water-god in his sea house (Abzu) (ea. 2200 B.C.). On the extreme right is Enki, the water-god, enthroned in his sea house. To the left is Utu, the sun-god, with his rays and saw. The middle deity is unidentified. (British Museum)![]() Gypsum statuette. “A Gypsum statuette of a priestess or goddess from the Sumerian Dynastic period, most likely Inanna. …She holds a sacred vessel from which the life-giving waters flow in two streams. Several gods and goddesses are shown thus with running water, including Inanna, and it speaks of their life-giving powers as only water brings life to the barren earth of Sumeria. The two streams of water are thought to stand for the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. This is the earliest of the group of statues and dates to c. 2600-2300 B.C. 150 mm tall.” http://www.aliraqi.org/forums/showthread.php?t=53773&page=2

Gypsum statuette. “A Gypsum statuette of a priestess or goddess from the Sumerian Dynastic period, most likely Inanna. …She holds a sacred vessel from which the life-giving waters flow in two streams. Several gods and goddesses are shown thus with running water, including Inanna, and it speaks of their life-giving powers as only water brings life to the barren earth of Sumeria. The two streams of water are thought to stand for the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. This is the earliest of the group of statues and dates to c. 2600-2300 B.C. 150 mm tall.” http://www.aliraqi.org/forums/showthread.php?t=53773&page=2These images are explained in terms of associated sacredness of Enki, who in Sumerian mythology

(Enki and Ninhursag) is associated with Abzu where he lives with the source sweet waters.

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A kind of sword, straight, broad-bladed, two-edged, and round-ended (Marathi) M. lokhãḍ n. ʻironʼ(Marthi) yields the clue to the early semantics of khāṇḍā which should have referred to tools, pots and pans (of metal). Kumaoni has semantics: lokhaṛ ʻiron tools’. लोहोलोखंड [ lōhōlōkhaṇḍa ] n (लोह & लोखंड) Iron tools, vessels, or articles in general (Marathi).

Thus lohakāṇḍā would have referred to copper tools. The overflowing vase on the hands of Gudea would have referred to this compound, represented by the hieroglyphs and rendered rebus.

lokhar ʻ bag in which a barber keeps his tools ʼ; H. lokhar m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; — X lauhabhāṇḍa — : Ku. lokhaṛ ʻ iron tools ʼ; H. lokhaṇḍ m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; G. lokhãḍ n. ʻ tools, iron, ironware ʼ; M. lokhãḍ n. ʻ iron ʼ (LM 400 < — khaṇḍa — )(CDIAL 11171). lōhitaka ʻ reddish ʼ Āpast., n. ʻ calx of brass, bell- metal ʼ lex. [lṓhita — ]K. lŏy f. ʻ white copper, bell — metal ʼ. (CDIAL 11166). lōhá ʻ red, copper — coloured ʼ ŚrS., ʻ made of copper ʼ ŚBr., m.n. ʻ copper ʼ VS., ʻ iron ʼ MBh. [*rudh — ] Pa. lōha — m. ʻ metal, esp. copper or bronze ʼ; Pk. lōha — m. ʻ iron ʼ, Gy. pal. li°, lihi, obl. elhás, as. loa JGLS new ser. ii 258; Wg. (Lumsden) “loa” ʻ steel ʼ; Kho. loh ʻ copper ʼ; S. lohu m. ʻ iron ʼ, L. lohā m., awāṇ.lōˋā, P. lohā m. (→ K.rām. ḍoḍ. lohā), WPah.bhad. lɔ̃u n., bhal. lòtilde; n., pāḍ. jaun. lōh, paṅ. luhā, cur. cam. lohā, Ku. luwā, N. lohu, °hā, A. lo, B. lo, no, Or. lohā, luhā, Mth. loh, Bhoj. lohā, Aw.lakh. lōh, H.loh, lohā m., G. M. loh n.; Si. loho, lō ʻ metal, ore, iron ʼ; Md. ratu — lō ʻ copper ʼ.(CDIAL 11158). lōhakāra m. ʻ iron — worker ʼ, °rī — f., °raka — m. lex., lauhakāra — m. Hit. [lōhá — , kāra — 1] Pa. lōhakāra — m. ʻ coppersmith, ironsmith ʼ; Pk. lōhāra — m. ʻ blacksmith ʼ, S. luhā̆ru m., L. lohār m., °rī f., awāṇ. luhār, P. WPah.khaś. bhal. luhār m., Ku. lwār, N. B. lohār, Or. lohaḷa, Bi.Bhoj. Aw.lakh. lohār, H. lohār, luh° m., G. lavār m., M. lohār m.; Si. lōvaru ʻ coppersmith ʼ. Addenda: lōhakāra — : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) lhwāˋr m. ʻ blacksmith ʼ, lhwàri f. ʻ his wife ʼ, Garh. lwār m.(CDIAL 11159). lōhahala 11161 lōhala ʻ made of iron ʼ W. [lōhá — ](CDIAL 11161). Bi. lohrā, °rī ʻ small iron pan ʼ(CDIAL 11160). Bi. lohsārī ʻ smithy ʼ(CDIAL 11162). P.ludh. lōhṭiyā m. ʻ ironmonger ʼ.(CDIAL 11163). लोहोलोखंड [ lōhōlōkhaṇḍa ] n (लोह & लोखंड) Iron tools, vessels, or articles in general.रुपेशाई लोखंड [ rupēśāī lōkhaṇḍa ] n A kind of iron. It is of inferior quality to शिक्केशाई. लोखंड [ lōkhaṇḍa ] n (लोह S) Iron. लोखंडाचे चणे खावविणें or चारणें To oppress grievously. लोखंडकाम [ lōkhaṇḍakāma ] n Iron work; that portion (of a building, machine &c.) which consists of iron. 2 The business of an ironsmith. लोखंडी [ lōkhaṇḍī ] a (लोखंड) Composed of iron; relating to iron. 2 fig. Hardy or hard–a constitution or a frame of body, one’s हाड or natal bone or parental stock. 3 Close and hard;–used of kinds of wood. 4 Ardent and unyielding–a fever. 5 लोखंडी, in the sense Hard and coarse or in the sense Strong or enduring, is freely applied as a term of distinction or designation. Examples follow. लोखंडी [ lōkhaṇḍī ] f (लोखंड) An iron boiler or other vessel. लोखंडी जर [ lōkhaṇḍī jara ] m (लोखंड & जर) False brocade or lace; lace &c. made of iron.लोखंडी रस्ता [ lōkhaṇḍī rastā ] m लोखंडी सडक f (Iron-road.) A railroad. लोह [ lōha ] n S Iron, crude or wrought. 2 m Abridged from लोहभस्म. A medicinal preparation from rust of iron.लोहकार [ lōhakāra ] m (S) A smelter of iron or a worker in iron.लोहकिट्ट [ lōhakiṭṭa ] n (S) Scoriæ or rust of iron, klinker.लोहंगी or लोहंगी काठी [ lōhaṅgī or lōhaṅgī kāṭhī ] f (लोह & अंग) A club set round with iron clamps and rings, a sort of bludgeon.लोहार [ lōhāra ] m ( H or लोहकार S) A caste or an individual of it. They are smiths or workers in iron. लोहारकाम [ lōhārakāma ] n Iron-work, work proper to the blacksmith.लोहारकी [ lōhārakī ] f (लोहार) The business of the blacksmith.लोहारडा [ lōhāraḍā ] m A contemptuous form of the word लोहार.लोहारसाळ [ lōhārasāḷa ] f A smithy.

Loha (nt.) [Cp. Vedic loha, of Idg. *(e)reudh “red”; see also rohita & lohita] metal, esp. copper, brass or bronze. It is often used as a general term & the individual application is not always sharply defined. Its comprehensiveness is evident from the classification of loha at VbhA 63, where it is said lohan ti jātilohaŋ, vijāti˚, kittima˚, pisāca˚ or natural metal, produced metal, artificial (i. e. alloys), & metal from the Pisāca district. Each is subdivided as follows: jāti˚=ayo, sajjhaŋ, suvaṇṇaŋ, tipu, sīsaŋ, tambalohaŋ, vekantakalohaŋ; vijāti˚=nāga — nāsika˚; kittima˚=kaŋsalohaŋ, vaṭṭa˚, ārakūṭaŋ; pisāca˚=morakkhakaŋ, puthukaŋ, malinakaŋ, capalakaŋ, selakaŋ, āṭakaŋ, bhallakaŋ, dūsilohaŋ. The description ends “Tesu pañca jātilohāni pāḷiyaŋ visuŋ vuttān’ eva (i. e. the first category are severally spoken of in the Canon). Tambalohaŋ vekantakan ti imehi pana dvīhi jātilohehi saddhiŋ sesaŋ sabbam pi idha lohan ti veditabbaŋ.” — On loha in similes see J.P.T.S. 1907, 131. Cp. A iii.16=S v.92 (five alloys of gold: ayo, loha, tipu, sīsaŋ, sajjhaŋ); J v.45 (asi˚); Miln 161 (suvaṇṇam pi jātivantaŋ lohena bhijjati); PvA 44, 95 (tamba˚=loha), 221 (tatta — loha — secanaŋ pouring out of boiling metal, one of the five ordeals in Niraya). — kaṭāha a copper (brass) receptacle Vin ii.170. — kāra a metal worker, coppersmith, blacksmith Miln 331. — kumbhī an iron cauldron Vin ii.170. Also N. of a purgatory J iii.22, 43; iv.493; v.268; SnA 59, 480; Sdhp 195. — guḷa an iron (or metal) ball A iv.131; Dh 371 (mā ˚ŋ gilī pamatto; cp. DhA iv.109). — jāla a copper (i. e. wire) netting PvA 153. — thālaka a copper bowl Nd1 226. — thāli a bronze kettle DhA i.126. — pāsāda“copper terrace,” brazen palace, N. of a famous monastery at Anurādhapura in Ceylon Vism 97; DA i.131; Mhvs passim. — piṇḍa an iron ball SnA 225. — bhaṇḍa copper (brass) ware Vin ii.135. — maya made of copper, brazen Sn 670; Pv ii.64. — māsa a copper bean Nd1 448 (suvaṇṇa — channa). — māsaka a small copper coin KhA 37 (jatu — māsaka, dāru — māsaka+); DhsA 318. — rūpa a bronze statue Mhvs 36, 31. — salākā a bronze gong — stick Vism 283. Lohatā (f.) [abstr. fr. loha] being a metal, in (suvaṇṇassa) aggalohatā the fact of gold being the best metal VvA 13. (Pali) agga- is explained: erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Kannada) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tulu) agasāle, agasāli, agasālavāḍu = a goldsmith (Telugu) cf. eruvai = copper (Tamil)

Thus loha in aggalohatā gets the semantics ‘metal’.

“Sumerian words with a pre-Sumerian origin are:

professional names such as simug ‘blacksmith’ and tibira ‘copper smith’, ‘metal-manufacturer’ are not in origin Sumerian words.

Agricultural terms, like engar ‘farmer’, apin ‘plow’ and absin ‘furrow’, are neither of Sumerian origin.

Craftsman like nangar ‘carpenter’, agab ‘leather worker’

Religious terms like sanga ‘priest’

Some of the most ancient cities, like Kish, have names that are not Sumerian in origin.

These words must have been loan words from a substrate language. The words show how far the division in labor had progressed even before the Sumerians arrived.”

The rebus readings are:

కాండము [ kāṇḍamu ] kānḍamu. [Skt.] n. Water. నీళ్లు (Telugu) kaṇṭhá — : (b) ʻ water — channel ʼ: Paš. kaṭāˊ ʻ irrigation channel ʼ, Shum. xãṭṭä. (CDIAL 14349). kāṇḍa ‘flowing water’ Rebus: kāṇḍā ‘metalware, tools, pots and pans’. lokhaṇḍ (overflowing pot) ‘metal tools, pots and pans, metalware’ lokhãḍ ‘overflowing pot’ Rebus: ʻtools, iron, ironwareʼ (Gujarati) Rebus: लोखंड lokhaṇḍ Iron tools, vessels, or articles in general. lo ‘pot to overflow’. Gu<loRa>(D) {} “^flowing strongly”.

கொட்டம்¹ koṭṭam Flowing, pouring; நீர் முதலியன ஒழுகுகை. கொடுங்காற் குண்டிகைக் கொட்ட மேய்ப்ப (பெருங். உஞ்சைக். 43, 130) கொட்டம் koṭṭam < gōṣṭha. Cattle- shed (Tamil)

koṭṭam flowing, pouring (Tamil). Ma. koṭṭuka to shoot out, empty a sack. ? Te. koṭṭukonipōv.

బత్తి batti batti. [for. Skt. భక్తి.] n. Faith. బత్తిగల faithful. "అంగనయెంతటి పుణ్యమూర్తివో, బత్తిజనింపనాదుచెర బాపితి." S. iii. 63. See on భక్తి. బత్తుడు battuḍu. n. A worshipper. భక్తుడు. The caste title of all the five castes of artificers as వడ్లబత్తుడు a carpenter. కడుపుబత్తుడు one who makes a god of his belly. L. xvi. 230. பத்தர்³ pattar, n. < bhakta. 1. Devotees, votaries; அடியார். பத்தர் சிக்கெனப் பிடித்த செல் வமே (திருவாச. 37, 8). 2. Persons who are loyal to God, king or country; அன்புடையார். தேசபத்தர். 3. A caste of Vīrašaiva vegetarians; வீரசைவரில் புலாலுண்ணாத வகுப்பினர். Loc.

Hieroglyph: pāṭroṛo m. ʻwooden troughʼ(Sindhi) pathiyā ʻ basket used as feeding trough for animals (Maithili): *prasthapattra ʻ seed account ʼ. [prastha -- 2, páttra -- ]K. pathawaturu m. ʻ memorandum showing the area sown ʼ.(CDIAL 8871) prastha2 m.n. ʻ a measure of weight or capacity = 32 palas ʼ MBh.Pa. pattha -- m. ʻ a measure = 1/4 āḷhaka, cooking vessel containing 1 pattha ʼ; NiDoc. prasta ʻ a measure ʼ; Pk. pattha -- , °aya -- m. ʻ a measure of grain ʼ; K. path m. ʻ a measure of land requiring 1 trakh (= 9 1/2 lb.) of seed ʼ; L. patth, (Ju.) path m. ʻ a measure of capacity = 4 boras ʼ; Ku. pātho ʻ a measure = 2 seers ʼ; N. pāthi ʻ a measure of capacity = 1/10 man ʼ; Bi. pathiyā ʻ basket used by sower or for feeding cattle ʼ; Mth. pāthā ʻ large milk pail ʼ, pathiyā ʻ basket used as feeding trough for animals ʼ; H. pāthī f. ʻ measure of corn for a year ʼ; Si. pata ʻ a measure of grain and liquids = 1/4 näliya ʼ.*prasthapattra -- .Addenda: prastha -- 2: WPah.poet. patho m. ʻ a grain measure about 2 seers ʼ (prob. ← Ku. Mth. form) Him.I 110.(CDIAL 8869) Ta. pātti bathing tub, watering trough or basin, spout, drain; pattal wooden bucket; pattar id., wooden trough for feeding animals. Ka. pāti basin for water round the foot of a tree. Tu. pāti trough or bathing tub, spout, drain. Te. pādi, pādu basin for water round the foot of a tree. (DEDR 4079) பத்தல் pattal, n. 1. A wooden bucket; மரத்தாலான நீரிறைக்குங் கருவி. தீம்பிழி யெந்திரம் பத்தல் வருந்த (பதிற்றுப். 19, 23). 2. See பத்தர்¹, 2. 3. See பத்தர்¹, 3. 4. Ditch, depression; குழி. ஆன்வழிப்படுநர் தோண்டிய பத்தல் (நற். 240). 5. A part of the stem of the palmyra leaf, out of which fibre is extracted; நாருரித்தற்கு ஏற்ற பனைமட்டையின் ஓருறுப்பு. (G. Tn. D. I, 221.) பத்தர்¹ pattar, n. 1. See பத்தல், 1, 4, 5. 2. Wooden trough for feeding animals; தொட்டி. பன்றிக் கூழ்ப்பத்தரில் (நாலடி, 257). 3. Cocoanut shell or gourd used as a vessel; குடுக்கை. கொடிக்காய்ப்பத்தர் (கல்லா. 40, 3).பாத்திரம்² pāttiram, n. < pātra. 1. Vessel, utensil; கொள்கலம். (பிங்.) 2. Mendicant's bowl; இரப்போர் கலம். (சூடா.) pāˊtra n. ʻ drinking vessel, dish ʼ RV., °aka -- n., pātrīˊ- ʻ vessel ʼ Gr̥ŚrS. [√pā1]Pa. patta -- n. ʻ bowl ʼ, °aka -- n. ʻ little bowl ʼ, pātĭ̄ -- f.; Pk. patta -- n., °tī -- f., amg. pāda -- , pāya -- n., pāī -- f. ʻ vessel ʼ; Sh. păti̯ f. ʻ large long dish ʼ (← Ind.?); K. pāthar, dat. °tras m. ʻ vessel, dish ʼ, pôturu m. ʻ pan of a pair of scales ʼ (gahana -- pāth, dat. pöċü f. ʻ jewels and dishes as part of dowry ʼ ← Ind.); S. pāṭri f. ʻ large earth or wooden dish ʼ, pāṭroṛo m. ʻ wooden trough ʼ; L. pātrī f. ʻ earthen kneading dish ʼ, parāt f. ʻ large open vessel in which bread is kneaded ʼ, awāṇ. pātrī ʻ plate ʼ; P. pātar m. ʻ vessel ʼ, parāt f., parātṛā m. ʻ large wooden kneading vessel ʼ, ḍog. pāttar m. ʻ brass or wooden do. ʼ; Ku.gng. pāiʻ wooden pot ʼ; B. pātil ʻ earthern cooking pot ʼ, °li ʻ small do. ʼ Or. pātiḷa, °tuḷi ʻ earthen pot ʼ, (Sambhalpur) sil -- pā ʻ stone mortar and pestle ʼ; Bi. patĭ̄lā ʻ earthen cooking vessel ʼ, patlā ʻ milking vessel ʼ, pailā ʻ small wooden dish for scraps ʼ; H. patīlā m. ʻ copper pot ʼ, patukī f. ʻ small pan ʼ; G. pātrũ n. ʻ wooden bowl ʼ, pātelũ n. ʻ brass cooking pot ʼ, parāt f. ʻ circular dish ʼ (→ M. parāt f. ʻ circular edged metal dish ʼ); Si. paya ʻ vessel ʼ, päya (< pātrīˊ -- ). (CDIAL 8055)

பத்தர்² pattar, n. < T. battuḍu. A caste title of goldsmiths; தட்டார் பட்டப்பெயருள் ஒன்று. பத்தர்&sup5; pattar, n. perh. vartaka. Merchants; வியாபாரிகள். (W.)Hypertext: सांगड sāṅgaḍa m f (संघट्ट S) f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together.

Rebus: sãgaṛh 'fortification' sangar 'trade' అంగడి aṅgaḍi angadi. [Drav.] (Gen. అంగటి Loc. అంగట, plu. అంగళ్లు) n. A shop. అంగడిపెట్టు to open a shop. అంగళ్లవాడ range of shops. అంగట పోకార్చి selling in the shop. అంగడివీధి a market place. Ta. aṅkāṭi bazaar, bazaar street. Ma. aṅṅāṭi shop, bazaar. Ko. aŋga·ḍy id. To. ogoḏy bazaar (? < Badaga). Ka. aṅgaḍi shop, stall. Koḍ. aŋgaḍi id. Tu. aṅgaḍi id. Te. aṅgaḍi id. Kol. aŋgaḍi bazaar. Nk.

aŋgāṛi id. Nk. (Ch.) aŋgāṛ market. Pa. aŋgoḍ courtyard, compound. / ? Cf. Skt. aṅgaṇa- courtyard.

(DEDR 35)

m1429

m1429

Pict-91

Pict-91

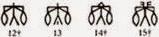

Mahadevan concordance Field Symbol 83: Person wearing a diadem or tall head-dress standing within an ornamented arch; there are two stars on either side, at the bottom of the arch.मेढ

Mahadevan concordance Field Symbol 83: Person wearing a diadem or tall head-dress standing within an ornamented arch; there are two stars on either side, at the bottom of the arch.मेढ  Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

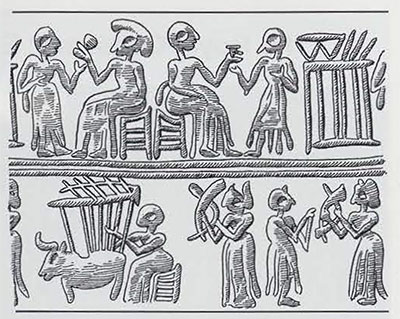

/detail-of-the-standard-of-ur-showing-a-sumerian-harpist-and-a-ruler-about-2600-2400-bc-501585375-589b3c525f9b5874eedd992b.jpg)

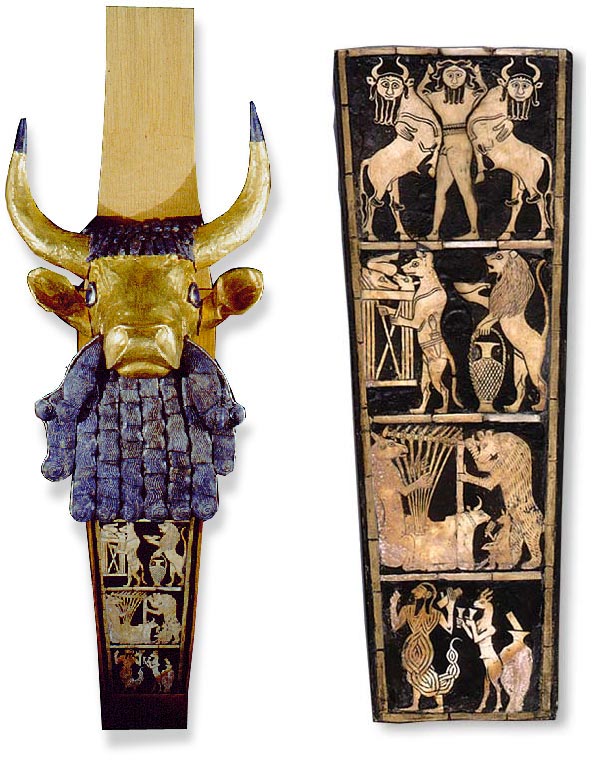

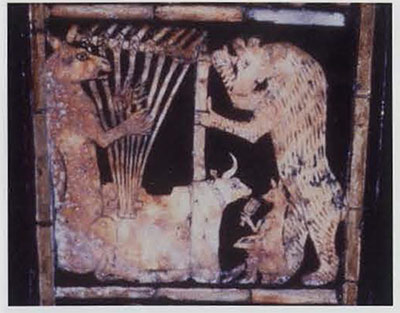

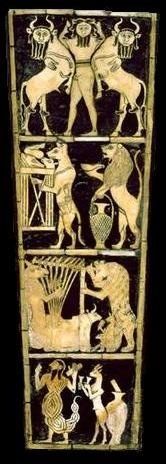

"Great Lyre" from Ur: Ht 33 cm

"Great Lyre" from Ur: Ht 33 cm

m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'

m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'

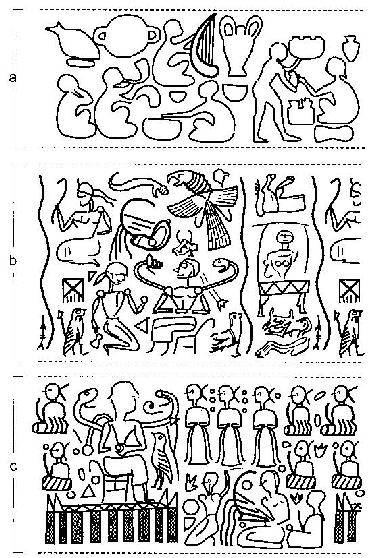

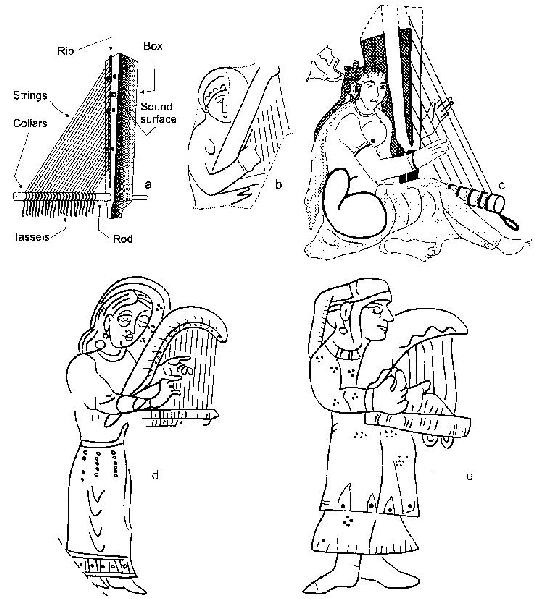

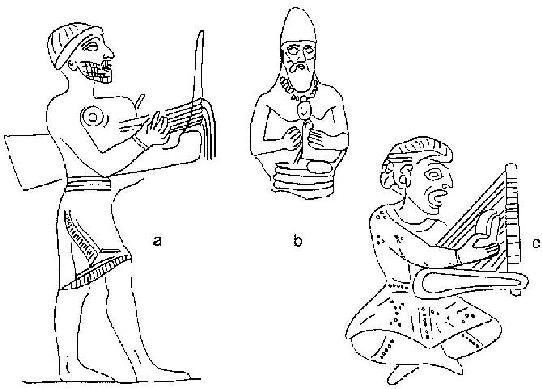

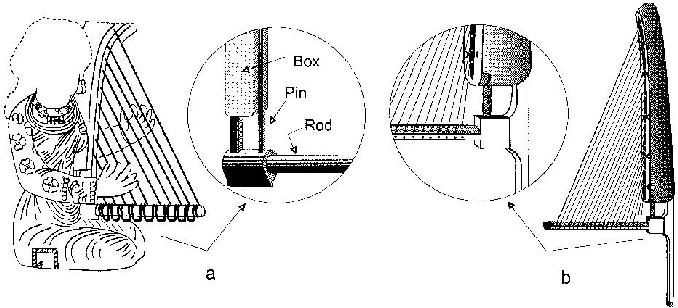

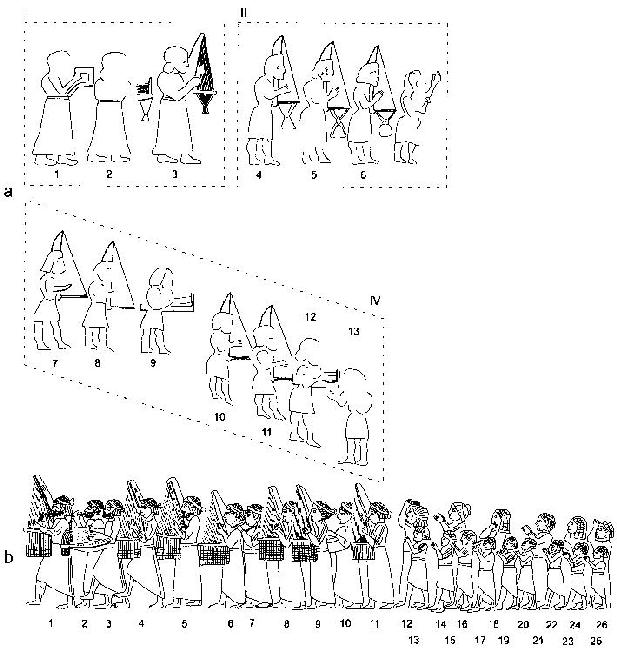

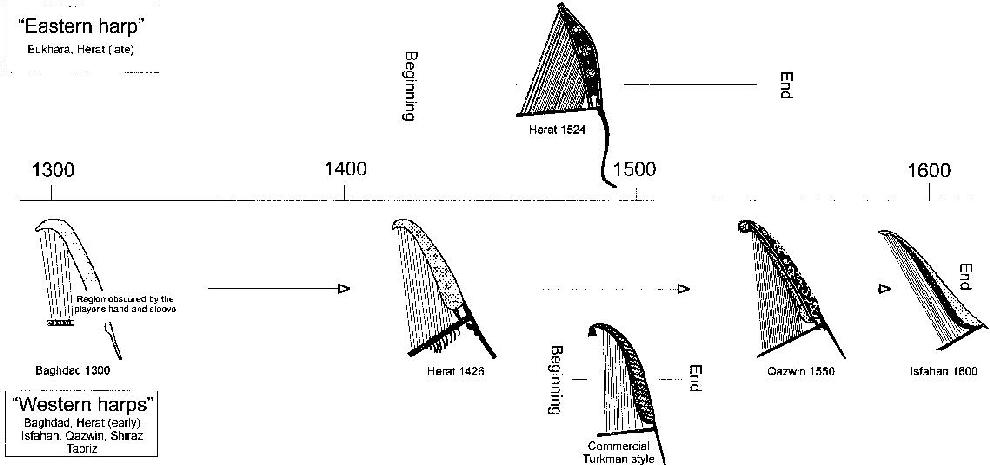

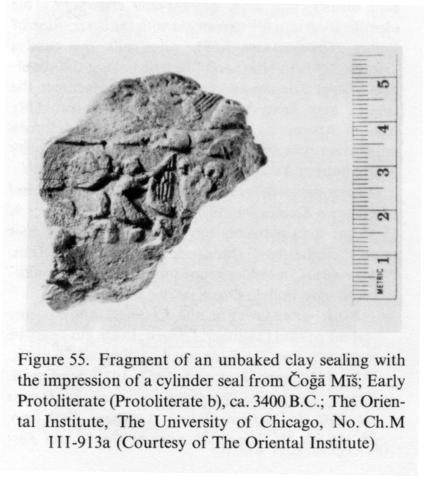

"These exchanges would have led to lengthy arguments carried out in various dialects. At best, the deals ended in banquets and at worst, in blood feuds. History abounds with trade arguments leading to wars. A bloody massacre such as that at Tell Brak would have led to the antagonists finding ways to appease tension during negotiations. Urukeans developed one of the most subtle and ancient arts as a possible solution. This is substantiated by the emergence of harps fitted with three or four strings, as depicted on a fourth millennium seal impression from Choga Mish, east of Uruk in Elam, in modern south-west Iran (Fig. 3). The seal depicts a four-string arched harp played by a seated person, while two others beat a drum, a bowl-drum and clappers. (

"These exchanges would have led to lengthy arguments carried out in various dialects. At best, the deals ended in banquets and at worst, in blood feuds. History abounds with trade arguments leading to wars. A bloody massacre such as that at Tell Brak would have led to the antagonists finding ways to appease tension during negotiations. Urukeans developed one of the most subtle and ancient arts as a possible solution. This is substantiated by the emergence of harps fitted with three or four strings, as depicted on a fourth millennium seal impression from Choga Mish, east of Uruk in Elam, in modern south-west Iran (Fig. 3). The seal depicts a four-string arched harp played by a seated person, while two others beat a drum, a bowl-drum and clappers. (

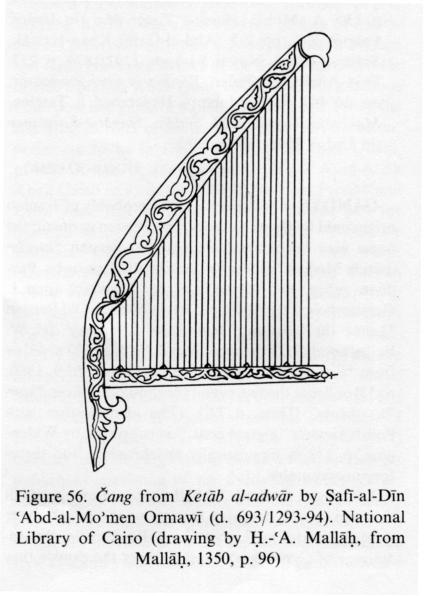

[quote]Harps from Uruk and Djemdet Nasr were generally monoxyle or monostructural, meaning that there was no distinction between the soundbox and the part which would become the yoke, or the neck. They would have been made from gourds or calabashes, the natural shape of which were appropriate for this. It is possible that they were domesticated through simple cultivation techniques which made them grow in the shape of musical instruments. 6The dried fruit was hollowed out from an oval opening, which was then covered with a soundboard made from damp sheep, pig or calf raw hide. It was stretched at the back with wet hide strands. The strings were made from fresh twisted gut or vegetal fibres. A sliver of wood was tied at the end of each string, to prevent it slipping out of the soundboard during tuning. The upper ends of the strings were tied to a strip of woven material rolled around the neck, to ensure tuning by friction (Fig. 5-left). At that time, and especially towards the end of the fourth millennium, the size of soundboxes progressively increased while necks became thinner. Gourds and calabashes would still have been used for soundboxes, but necks would now be made of wood into which the Urukeans would later have plugged tuning pegs to ensure the tension of the strings (Fig. 5-right). Fourth millennium harps would have been small, with probably no more than three strings, stretched over a plan of around 110 degrees determined by the angle of the soundbox in relation to the neck. This suggests an anhemitonic disposition with a span of no more than a musical fifth, possibly including a third. These harps were always depicted in rural scenes, surrounded by animals, but with no reference to religious rituals; practical usage was thus implied, as is clearly shown on cylinder seals. However, from the third millennium onwards, harps were always shown in scenes depicting Inanna, the guardian Goddess of Uruk; they even symbolised her. Some texts record Inanna’s animals and her attributes, which included the reed, the palm, the aster Venus, and the harp itself.

[quote]Harps from Uruk and Djemdet Nasr were generally monoxyle or monostructural, meaning that there was no distinction between the soundbox and the part which would become the yoke, or the neck. They would have been made from gourds or calabashes, the natural shape of which were appropriate for this. It is possible that they were domesticated through simple cultivation techniques which made them grow in the shape of musical instruments. 6The dried fruit was hollowed out from an oval opening, which was then covered with a soundboard made from damp sheep, pig or calf raw hide. It was stretched at the back with wet hide strands. The strings were made from fresh twisted gut or vegetal fibres. A sliver of wood was tied at the end of each string, to prevent it slipping out of the soundboard during tuning. The upper ends of the strings were tied to a strip of woven material rolled around the neck, to ensure tuning by friction (Fig. 5-left). At that time, and especially towards the end of the fourth millennium, the size of soundboxes progressively increased while necks became thinner. Gourds and calabashes would still have been used for soundboxes, but necks would now be made of wood into which the Urukeans would later have plugged tuning pegs to ensure the tension of the strings (Fig. 5-right). Fourth millennium harps would have been small, with probably no more than three strings, stretched over a plan of around 110 degrees determined by the angle of the soundbox in relation to the neck. This suggests an anhemitonic disposition with a span of no more than a musical fifth, possibly including a third. These harps were always depicted in rural scenes, surrounded by animals, but with no reference to religious rituals; practical usage was thus implied, as is clearly shown on cylinder seals. However, from the third millennium onwards, harps were always shown in scenes depicting Inanna, the guardian Goddess of Uruk; they even symbolised her. Some texts record Inanna’s animals and her attributes, which included the reed, the palm, the aster Venus, and the harp itself.

Chapitre 1

Chapitre 1

Carved stone tablets with the inscription Om syllables from Om Mani Padme Hum mantra - Everest region, Nepal, Himalayas

Carved stone tablets with the inscription Om syllables from Om Mani Padme Hum mantra - Everest region, Nepal, Himalayas

Goa. An aerial view.

Goa. An aerial view. Gudea (

Gudea (

Gudea portrait on statue.

Gudea portrait on statue.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā

Reed PLUS ring on Inanna standard on Warka vase.

Reed PLUS ring on Inanna standard on Warka vase.

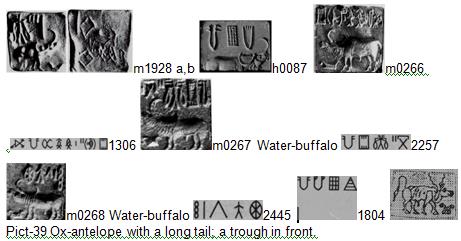

Trough PLUS buffalo/bull

Trough PLUS buffalo/bull

Banawali b-17 Tiger PLUS standard device

Banawali b-17 Tiger PLUS standard device m290 tiger PLUS trough

m290 tiger PLUS trough

h088 Rhinoceros PLUS trough

h088 Rhinoceros PLUS trough

Mund. Toda.

Mund. Toda.

Pearl millet in the field.

Pearl millet in the field.

In front of a soldier, a

In front of a soldier, a

"

"

Large male gaur.

Large male gaur. Present range of Gaur.

Present range of Gaur.

Workers from Elam, Susa, Magan and Meluhha were deployed by Gudea, the ruler of Lagaṣ, to build The Eninnu, the main temple of Girsu, c. 2125 BCE. We are dealing with Indian sprachbundwhen we refer to Meluhha. This sprachbund has a remarkable lexeme which is used to signify a smithy, as also a temple: Kota. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. Toda. kwala·l Kota smithy Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer; Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133).

Workers from Elam, Susa, Magan and Meluhha were deployed by Gudea, the ruler of Lagaṣ, to build The Eninnu, the main temple of Girsu, c. 2125 BCE. We are dealing with Indian sprachbundwhen we refer to Meluhha. This sprachbund has a remarkable lexeme which is used to signify a smithy, as also a temple: Kota. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. Toda. kwala·l Kota smithy Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer; Ka.kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith; (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith. Te. kolimi furnace. Go.(SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133).

Cylinder seal explained as Enki seated on a throne with a flowing stream full of fish, ca. 2250 BCE

Cylinder seal explained as Enki seated on a throne with a flowing stream full of fish, ca. 2250 BCE

2605 (#KJ Roach’s thesis). Sealed tablet. Susa. Illituram, son of Il-mishar, servant of Pala-isshan

2605 (#KJ Roach’s thesis). Sealed tablet. Susa. Illituram, son of Il-mishar, servant of Pala-isshan #KJ Roach M9 Mesopotamia

#KJ Roach M9 Mesopotamia #Roach 2168 Cream limestone. Susa.

#Roach 2168 Cream limestone. Susa. A person with a vase with overflowing water; sun sign. C. 18th cent. BCE. [E. Porada,1971, Remarks on seals found in the Gulf states, Artibus Asiae, 33, 31-7

A person with a vase with overflowing water; sun sign. C. 18th cent. BCE. [E. Porada,1971, Remarks on seals found in the Gulf states, Artibus Asiae, 33, 31-7 See:

See:  The seal of Gudea

The seal of Gudea

Musee

Musee Sumerian sign for the term ZAG ‘purified precious’. The ingot had a hole running through its length Perhaps a carrying rod was inserted through this hole.

Sumerian sign for the term ZAG ‘purified precious’. The ingot had a hole running through its length Perhaps a carrying rod was inserted through this hole. Cylinder seal with kneeling nude heroes, ca. 2220–2159 b.c.; Akkadian Mesopotamia Red jasper H. 1 1/8 in. (2.8 cm), Diam. 5/8 in. (1.6 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art – USA

Cylinder seal with kneeling nude heroes, ca. 2220–2159 b.c.; Akkadian Mesopotamia Red jasper H. 1 1/8 in. (2.8 cm), Diam. 5/8 in. (1.6 cm) Metropolitan Museum of Art – USA The four hieroglyphs define the four quarters of the village smithy/forge: alloy, metalware, turner’s lathe-work, cruble (or, ingot).

The four hieroglyphs define the four quarters of the village smithy/forge: alloy, metalware, turner’s lathe-work, cruble (or, ingot). A baked-clay plaque from Ur, Iraq, portraying a goddess; she holds a vase overflowing with water (‘hé-gál’ or ‘hegallu’) is a symbol of abundance and prosperity. (Beijing World Art Museum) Fish in water on statue, on viewer’s right.

A baked-clay plaque from Ur, Iraq, portraying a goddess; she holds a vase overflowing with water (‘hé-gál’ or ‘hegallu’) is a symbol of abundance and prosperity. (Beijing World Art Museum) Fish in water on statue, on viewer’s right.  Enki walks out of the water to the land attended by his messenger, Isimud

Enki walks out of the water to the land attended by his messenger, Isimud

Gypsum statuette. “A Gypsum statuette of a priestess or goddess from the Sumerian Dynastic period, most likely Inanna. …She holds a sacred vessel from which the life-giving waters flow in two streams. Several gods and goddesses are shown thus with running water, including Inanna, and it speaks of their life-giving powers as only water brings life to the barren earth of Sumeria. The two streams of water are thought to stand for the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. This is the earliest of the group of statues and dates to c. 2600-2300 B.C. 150 mm tall.”

Gypsum statuette. “A Gypsum statuette of a priestess or goddess from the Sumerian Dynastic period, most likely Inanna. …She holds a sacred vessel from which the life-giving waters flow in two streams. Several gods and goddesses are shown thus with running water, including Inanna, and it speaks of their life-giving powers as only water brings life to the barren earth of Sumeria. The two streams of water are thought to stand for the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. This is the earliest of the group of statues and dates to c. 2600-2300 B.C. 150 mm tall.”