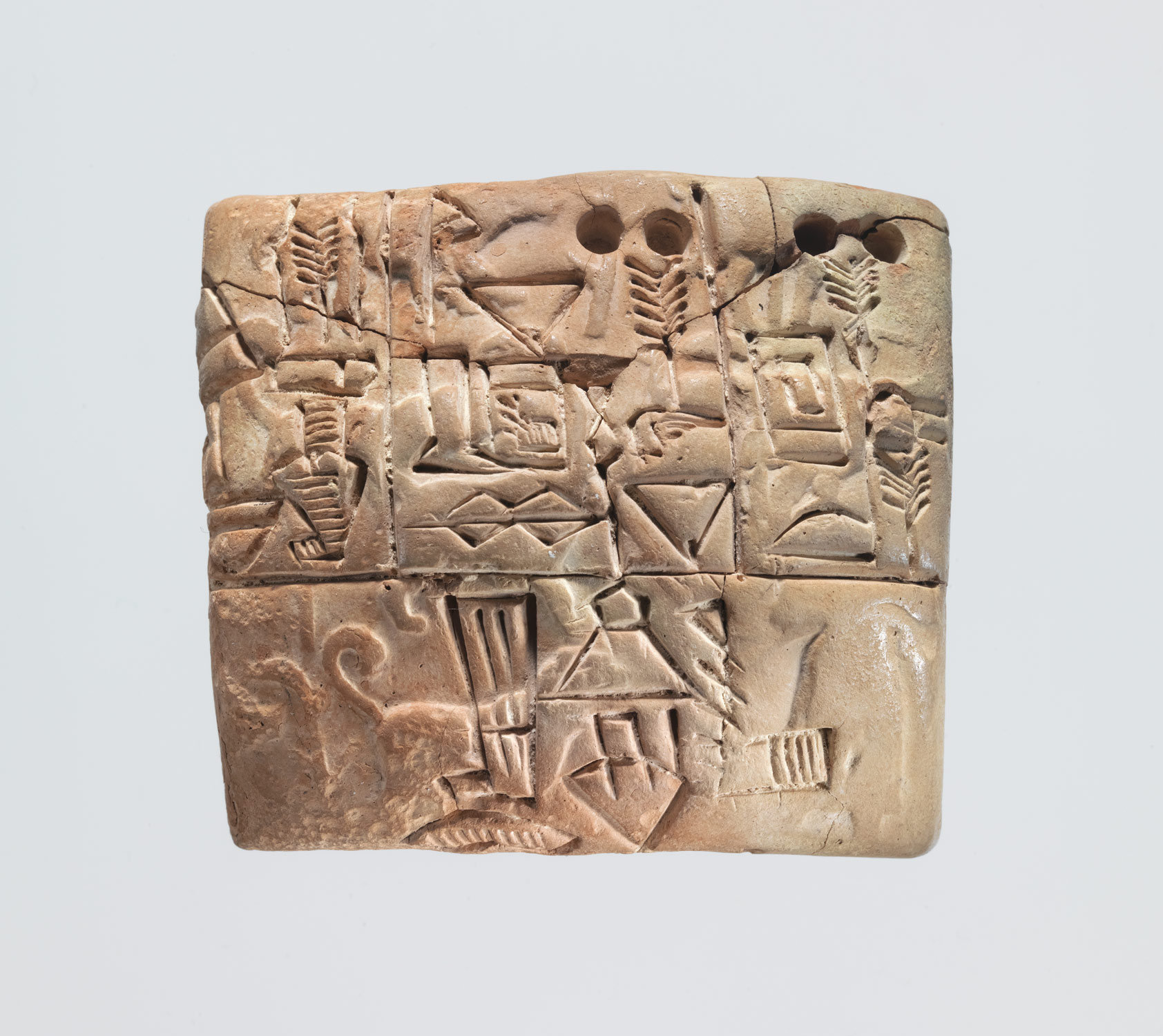

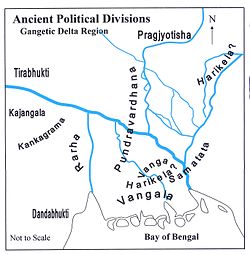

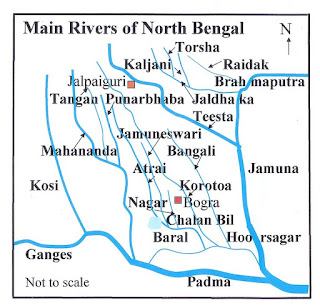

Note: The reference to Videha occurs in Baudhayana Srauta Sutra (BSS).See the detailed article by Vishal Agarwal. Puratattva (Bulletin of the Indian Archaeolgical Society), New Delhi,No. 36, 2005-06, pp. 155-165 On Perceiving Aryan Migrations in Vedic Ritual Texts. Kāśi-Videha is the region into which some from Kurukshetra migrated. When did this migration occur? Pururava-Uruvasi dialog, finds mention in Rgveda X.95. BSS 18.45 notes that the descendants of Amavasu, i.e., Arattas, Parsus and Gandharis migrated westwards from the Kurushetra region. Caland: "To the East went Ayus; from him descend the Kurus, Pancalas, Kasis and Videhas. These are the peoples which originated as a consequence of Ayus's going forth. To the West went Amavasu; from him descend the Gandharis, the Sparsus and the Arattas. These are the peoples which originated as a consequence of Amavasu's going forth." So when did the Ayus migrate to Kāśi-Videha? Since RV mentions the ākhyāna, the date of migration eastwards may relate to a period earlier than the RV text (X.95). This means that the iron age at Videha on Ganga Basin is coterminus with the Bronze Age of Sarasvati Civilization. What is Sadānīra? Karatoya? Gaṇḍakī? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pundranagar![BD Map Rivers of North Bengal2.jpg]() Rivers of Bangladesh, August 1997 edition, produced by Graphosman, 55/1 Purana Paltan, Dhaka – 1000, map of Bengal in History of Ancient Bengal, by Dr. R.C. Majumdar,First published 1971, Reprint 2005, p. 4

Rivers of Bangladesh, August 1997 edition, produced by Graphosman, 55/1 Purana Paltan, Dhaka – 1000, map of Bengal in History of Ancient Bengal, by Dr. R.C. Majumdar,First published 1971, Reprint 2005, p. 4

Comment on: http://indiafacts.org/the-memory-of-a-lost-civilization/

KalyanaramanOn Perceiving Aryan Migrations in Vedic Ritual Texts

By Vishal Agarwal

Puratattva (Bulletin of the Indian Archaeolgical Society), New Delhi,No. 36, 2005-06, pp. 155-165

1. Background:

Vedicists have generally agreed in the last 150 years that the vast corpus of extant Vedic literature, comprising of several hundred texts, is completely silent on Aryan immigrations from Central Asia into India. But, in a lecture delivered on 11 October 1999 at the Jawaharlal Nehru University (New Delhi), historian Romila Thapar (1999) made a revisionist claim:

" ...and later on, the Srauta Sutra of Baudhayana refers to the Parasus and the arattas who stayed behind and others who moved eastwards to the middle Ganges valley and the places equivalent such as the Kasi, the Videhas and the Kuru Pancalas, and so on. In fact, when one looks for them, there are evidence for migration."

Another historian of ancient India, Ram Sharan Sharma considers this passage as an important piece of evidence in favor of the Aryan Migration Theory (AMT). He writes (Sharma 1999: 87-89):

"More importantly, Witzel produces a passage from the Baudhayana Srautasutra which contains 'the most explicit statement of immigration into the Subcontinent'. This passage contains a dialogue between Pururava and Urvasi which refers to horses, chariot parts, 100 houses and 100 jars of ghee.

Towards the end, it speaks of the birth of their sons Ayu and Amavasu, who were asked by their parents, to go out. 'Ayu went eastward. His people are the Kuru-Pancalas and the Kasi-Videhas. This is the Ayava kin group. Amavasu stayed in the west. His people are the Gandharas, the Parsavas and the Arattas. This is the Amavasava kin group.'"

Sharma is so confident of the 'evidence' of the AMT produced by Witzel that he even goes to the extent of co-relating these two groups with various pottery types attested in the archaeological record (ibid, p. 89). It is quite apparent that all these claims of alleged Vedic literary evidence for an Indo-Aryan immigration into

the Indian subcontinent are informed by the following passage written by a Harvard philologist (Witzel 1995: 320-321):

"Taking a look at the data relating to the immigration of the Indo-Aryans into South Asia, one is stuck by the number of vague reminiscences of foreign localities and tribes in the Rgveda, inspite repeated assertions to the contrary in the secondary literature. Then, there is the following direct statement contained in (the admittedly much later) BSS (=Baudhayana Shrauta Sutra) 18.44:397.9 sqq which has once again been overlooked, not having been translated yet: "Ayu went eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru Panchala and the Kasi-Videha. This is the Ayava (migration). (His other people) stayed at home. His people are the Gandhari, Parsu and Aratta. This is the Amavasava (group)" (Witzel 1989a: 235)."

That the above passage of the Baudhayana Srautasutra (henceforth 'BSS') is the only 'direct' evidence for an Indo-Aryan immigration into India is clarified by Witzel in the same article later (p. 321). The reference (Witzel 1989a: 235) at the end of the above citation pertains to an earlier article by Witzel, where he has elaborated it

further (Witzel 1989: 235):

"In the case of ancient N. India, we do not know anything about the immigration of various tribes and clans, except for a few elusive remarks in the RV (= Rigveda), SB (= Shatapatha Brahmana) or BSS ( =Baudhayana Shrauta Sutra). This text retains at 18.44 : 397.9 sqq. the most pregnant memory, perhaps, of an immigration of the Indo- Aryans into Northern India and of their split into two groups: pran Ayuh pravavraja. Tasyaite Kuru-Pancalah Kasi-Videha ity. Etad Ayavam pravrajam. Pratyan amavasus. Tasyaite Gandharvarayas Parsavo 'ratta

ity. Etad Amavasavam. "Ayu went eastwards. His (people) are the Kuru- Pancala and the Kasi Videha. This is the Ayava migration. (His other people) stayed at home in the West. His people are the Gandhari, Parsu and Aratta. This is the Amavasava (group)".

Finally, this mistranslation is found in an even older publication of Witzel (1987: 202) as well. This article intends to show how this Sutra passage actually says the reverse of what Witzel intends to prove, because Witzel's translation is flawed. As an aside, a Czech scholar Vaclav Blazek (2002: 216) relies on the mistranslation of the

passage in Witzel (1995: 320-321) to reinforce his conclusion that the Arattas were localized in the Helmand basin. Interestingly, in the 'Acknowledgements' section (p. 235) of the paper, Blazek mentions Witzel. Therefore, we can discount his interpretation as one that has no independent value due to it being dependent upon Witzel's

erroneous arguments.

2. Grammatical Flaws in Witzel's Mis-translation of Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44-

In a review of Erdosy's volume where Witzel's article appeared, Koenraad Elst took issue with Witzel on the precise translation of the Sanskrit passage. He stated (Elst 1999: 164-165):

"This passage consists of two halves in parallel, and it is unlikely that in such a construction, the subject of the second half would remain unexpressed, and that terms containing contrastive information (like "migration" as opposed to the alleged non-migration of the other group) would remain unexpressed, all left for future scholars

to fill in. It is more likely that a non-contrastive term representing a subject indicated in both statements, is left

unexpressed in the second: that exactly is the case with the verb pravavrāja "he went", meaning "Ayu went" and "Amavasu went". Amavasu is the subject of the second statement, but Witzel spirits the subject away, leaving the statement subject-less, and turns it into a verb, "amā vasu", "stayed at home". In fact, the meaning of the sentence is really quite straightforward, and doesn't require supposing a lot of unexpressed subjects: "Ayu went east, his is the Yamuna-Ganga region", while "Amavasu went west, his is Afghanistan, Parshu and West Panjab". Though the then location of "Parshu" (Persia?) is hard to decide, it is definitely a western country,

along with the two others named, western from the viewpoint of a people settled near the Saraswati river in what is now Haryana. Far from attesting an eastward movement into India, this text actually speaks of a westward movement towards Central Asia, coupled with a symmetrical eastward movement from India's demographic centre around the Saraswati basin towards the Ganga basin."

Elst further commented (ibid):"The fact that a world-class specialist has to content himself with a late text like the BSS, and that he has to twist its meaning this much in order to get an invasionist story out of it, suggests that harvesting invasionist information in the oldest literature is very difficult indeed. Witzel claims (op. cit., p.320) that: 'Taking a look at the data relating to the immigration of Indo-Aryans into South Asia, one is struck by a number of vague reminiscences of foreign localities and tribes in the Rgveda, in spite [of] repeated assertions to the contrary in the secondary literature.' But after this promising start, he fails to quote even a single one of those 'vague reminiscences'."

If Elst's critique is correct, the solitary direct literary evidence cited by Witzel for the AMT gets annulled. Elst's revelation generated a very bitter controversy involving accusations of a personal nature. We need not detail these here as the controversy is documented in my earlier online article (Agarwal 2001). Dr. S.

Kalyanaraman, referred the matter to Dr. George Cardona, an international authority in Sanskrit language and author of numerous definitive publications on Panini's grammar. Cardona clearly rejected Witzel's translation, and upheld the objections of Elst on the basis of rules of Sanskrit grammar. In a message posted on an internet

discussion forum, he stated (Cardona 2000):

"The passage (from Baudha_yana S'rautasu_tra), part of a version of the Puruuravas and Urva'sii legend concerns two children that Urva'sii bore and which were to attain their full life span, in contrast with the previous ones she had put away. On p. 397, line 8, the text says: saayu.m caamaavasu.m ca janayaa.m cakaara 'she bore

Saayu and Amaavasu.' Clearly, the following text concerns these two sons, and not one of them along with some vague people. Grammatical points also speak against Witzel's interpretation. First, if amaavasus is taken as amaa 'at home' followed by a form of vas, this causes problems: the imperfect third plural of vas (present vasati

vasata.h vasanti etc.) would be avasan; the third plural aorist would be avaatsu.h. I have not had the chance to check Witzel's article again directly, so I cannot say what he says about a purported verb form (a)vasu.h. It is possible, however, that Elst has misunderstood Witzel and that the latter did not mean vasu as a verb form per se.

Instead, he may have taken amaa-vasu.h as the nominative singular of a compound amaa-vasu- meaning literally 'stay-at-home', with -vas-u- being a derivate in -u- from -vas. In this case, there is still what Elst points out: an abrupt elliptic syntax that is a mismatch with the earlier mention of Amaavasu along with Aayu. Further, tasya can

only be genitive singular and, in accordance with usual Vedic (and later) syntax, should have as antecedent the closest earlier nominal: if we take the text as referring to Amaavasu, all is in order: tasya (sc. Amaavaso.h). Finally, the taddhitaanta derivates aayava and aamaavasava then are correctly parallels to the terms aayu and

amaavasu. In sum, everything fits grammatically and thematically if we straightforwardly view the text as concerning the wanderings of two sons of Urva'sii and the people associated with them. There is

certainly no good way of having this refer to a people that remained in the west."

The noted archaeologist B. B. Lal (Lal 2005: 85-88) has also stated clearly that Witzel's translation is untenable and is a willful distortion of Vedic texts to prove the non-proven Aryan migration theory (AMT). Lal's criticism is along the same lines as that of Elst.

3. Translations of BSS 18:44 by other Scholars in English, German and Dutch: Let us consider the few publications where the relevant Baudhayana Srautasutra (BSS) passage has actually been studied, or has beentranslated by other scholars.

3.1 Willem Caland's Dutch translation: It is Caland who first published the Baudhayana Srautrasutra from manuscripts (Caland 1903-1913). In an obscure study of the Urvashi legend written in Dutch, he focuses on the version found in Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44-45 and translates the relevant sentences of text (Caland 1903: 58). Translated into English, the relevant sentences in the Dutch original read:

"To the East went Ayus; from him descend the Kurus, Pancalas, Kasis and Videhas. These are the peoples which originated as a consequence of Ayus's going forth. To the West went Amavasu; from him descend the Gandharis, the Sparsus and the Arattas. These are the peoples which originated as a consequence of Amavasu's going forth."

The text, as reconstituted by Caland (and also accepted by Kashikar - - see below) reads 'Sparsus', which apparently stands for the peoples who are known as 'Parshus' elsewhere in the Vedic literature, and are often identified as the ancestors of Persians (or even of Pashtuns). Clearly, Caland interpreted this sutra passage to mean that from a central region, the Arattas, Gandharis and Parsus migrated west, while the Kasi-Videhas and Kuru-Pancalas migrated east. Combined with the testimony of the Satapatha Brahmana (see below), the implication of this version in the Baudhayana Srautasutra, narrated in the context of the agnyadheya rite, is that that the two outward migrations took place from the central region watered by the Sarasvati. Interestingly, the volume of Caland's Kleine Schriften have been edited as by none other than Michael Witzel (1990).

Therefore it is all the more surprising that in this entire controversy, Witzel did not allude to Caland's translation of the passage at all!

3.2 C. G. Kashikar's English translation: Very recently, Kashikar (2003: 1235) has translated the relevant sentences of the text as follows:

"Ayu moved towards the east. Kuru-Pancala and Kasi-Videha were his regions. This is the realm of Ayu. Amavasu proceeded towards the west. The Gandharis, Sparsus and Arattas were his regions. This is the realm of Amavasu."

3.3 D. S. Triveda's English translation: In an article (Triveda 1938- 39) dealing specifically with the homeland of Aryans, he titles the concluding section as "Aryans went abroad from India". He commences this section with the following words (ibid, p. 68):

"The Kalpasutra asserts that Pururavas had two sons by Urvasi -- Ayus and Amavasu. Ayu went eastwards and founded Kuru -- Pancala and Kasi -- Videha nations, while Amavasu went westwards and founded Gandhara,

Sprsava and Aratta."

In a footnote, the author gives the source as 'Baudhayana Srautasutra XVIII. 35-51'. The address is wrong, but it is clear that Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44 is meant. Therefore, Triveda also takes the passage to mean that Amavasu migrated westwards, rather than staying where he was as Witzel would translate it.

3.4 Toshifumi Goto's German Translation: In his recent study (Goto 2000) of some parallel Vedic passages dealing with the agnyadheya rite, Toshifumi Goto translates the relevant Sutra passage into German (p. 101 sqq.). Loosely translated into English, this reads: "From there, Ayu wandered Eastwards. To him belong (the groups

called) 'Kurus and Panchalas, Kashis and Videhas' (note 87). They are the branches/leading away (note 88) originating from Ayu. From there, Amavasu turned westwards (wandered forth). To him belong (the groups

called) 'Gandharis, Parsus (note 89) Arattas'. They are the branches/leading away originating from Amavasu. (note 90)."

{90}: It appears that the notion of 'Ayu' as an normal adjectival sense 'living', 'agile' underlies this name. Correspondingly, Krick 214 interprets Amavasu as -- "Westwards [travelled] A. (or: he stayed back in the west in his home, because his name says -- 'one who has his goods at home')".

Notes 87-89 in the German original are irrelevant to this present discussion and are therefore left untranslated here. We will discuss the views of Hertha Krick referred to by Goto in greater detail later. What is important here is that four scholars have translated the disputed passage in the same manner as Elst, and differently from

Witzel.

4. Pururava-Uruvasi (or Urvasi) Narratives in Vedic Texts, a Conspectus:

The Pururava-Urvasi legend is found in numerous Vedic and non-Vedic texts. In the former, the couple and their son Ayu are related to the agnyadheya rite. Some passages in Vedic texts that allude to this rite/tale are -- Rigveda 10.95; Kathaka Samhita 26.7 etc.; Agnyadheya Brahmana (in the surviving portions of the Brahmana of Katha Sakha) etc.; Maitrayani Samhita 1.2.7; 3.9.5; Vajasneyi (Madhyandina) Samhita 5.2; Satapatha Brahmana (Madhyandina) 11.5.1.1; Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44-45; Vadhula Anvakhyana 1.1-2 etc. Note that the Kathaka Brahmana exists only in short fragments, most of which have been collected together by Suryakanta (1981), Rosenfield (2004) and also by some other earlier scholars. The agnyadheya brahmanam portion of the Kathaka Brahmana survives (and is included in Suryakanta's collection), but it does not shed any light on the question at hand. Many of the above textual references, as well as those in Srautasutras (not listed above), do not throw much light on the historical aspects of the legend. Several passages cursorily mention Urvasi as mother, Pururava as father, Ayu (equated to Agni) as their son and ghee as (Pururava's) seed in a symbolic manner in connection with various rites (Taittiriya Samhita 1.3.7.1; 6.3.5.3; Kathaka Samhita 3.4; Kapisthala Samhita 2.11; 41.5; Kanva Samhita 5.2; Maitrayani Samhita 2.8.10). Elsewhere, Urvasi is enumerated as an apsara and prayers are directed towards her for protection (Kathaka Samhita 17.9; Kapisthala Samhita 26.8, Taittiriya Samhita 4.4.3.2; Maitrayani Samhita 2.8.10). At least in one ritual context, Urvasi is taken to represent all Devis (Taittiriya Samhita 1.2.5.2). Kathaka Samhita 8.10 narrates the tale in brief and may be paraphrased as:

"Urvasi was the wife of Pururava. She left Pururava and returned to devas. Pururava prayed to devas for Urvasi. Then, devas gave him a son named Ayu. At their bidding, Pururava fabricated aranis (fire stick and base used for the fire sacrifice) from the branches of a tree and rubbed them together. This generated fire, and Pururava's desire was fulfilled. He who establishes sacrificial fires this attains progeny, animals etc.".

Thus, this passage also equates Ayu with Agni. In addition, some passages of Srautasutras mention them in the context of caturmasya rites (E.g., Katyayana Srautasutra 5.1.24-25).

The texts that are of most use for the present purpose are Rigveda 10.95, Satapatha Brahmana 11.5.1; Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44-45 and Vadhula Anvakhyana 1.1-2. Dozens of published secondary studies

examine the legend from the data scattered in Vedic, Puranic and Kavya texts. We need not dwell upon the versions available in Brhaddevata, Sarvanukramani, Puranas etc., here because they are either too late or do not shed any additional light on our problem. A survey of a few of these is given in Shridhar (2001: 311-345). Most

of these studies do take into account the information contained in Rigveda and Satapatha Brahmana. Very few however analyze the information in the Baudhayana Srautasutra. Even Volume I.1 of the Srautakosa (Dandekar 1958), which studies the agnyadheya rite in detail with a special emphasis on the Baudhayana Srautasutra, ignores these sections. To my knowledge, only Willem Caland (1903), Hertha Krick (1982) and Yasuke Ikari (1998) have studied the relevant sections of the Baudhayana Srautasutra in detail.

5. Kuruksetra in Baudhayana Srautasutra 18:45:

A very strong piece of evidence for deciding the correct translation of Baudhayana Srautrasutra 18.44 is the passage that occurs right after it, i.e., Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.45. I am reproducing the translation of Kashikar (2003: 1235) with minor modifications that do not affect the issue at hand:

"[....]After having returned from the Avabhrta (the king) saw her (Urvasi). The sons approached her and said, "Do thou take us there where thou are going. We are strong. Thou hast put our father, one of you two, to grief."[2]

She said, "O sons, I have given birth to you together. (Therefore) I stay here for three nights. Let not the word of the brahmana be untrue." The king wearing the inner garment lived with her for three nights. He shed semen virile unto her.

She said, "What is to be done?""What to do?", the king responded. She said, "Do thou fetch a new pitcher?" She disposed it into it. In Kurukshetra, there were ponds called Bisavati. The northern-most among then created gold. She put it (the semen) into it (the pond). From it (the banks of the pond) came out the Asvattha tree surrounded

by Sami. It was Asvattha because of the virile semen, it was Sami by reason of the womb. Such is the creation of (Asvattha tree) born over Sami. This is its source.

It is indeed said, "Gods attained heaven through the entire sacrifice."[3]

When the sacrifice came down to man from the gods, it came down upon the Asvattha (tree). They prepared the churning woods out of it; it is the sacrifice. Indeed, whichever may the Asvattha be, it should be deemed, as growing on the Sami (tree). [....]

[2] Doubtful word and meaning.

[3] Taittiriya Samhita I.7.1.3"

From this text, it is clear that Urvasi, Pururava and their two sons were present in Kurukshetra in their very lifetimes. There is no evidence that Ayu's descendants traveled all the way from Afghanistan to Haryana (where Kurukshetra is located) subsequently, nor is there any evidence that she took her sons from Kurukshetra to Afghanistan after disposing off the pitcher. Therefore, the disputed passage BSS 18.45 would imply that the descendants of Amavasu, i.e., Arattas, Parsus and Gandharis migrated westwards from the Kurushetra region.

Note that in Taittiriya Aranyaka 5.1.1, the Kurukshetra region is said to be bounded by Turghna (=Srughna or the modern village of Sugh in the Sirhind district of Punjab) in the north, by Khandava in the south (corresponding roughly to Delhi and Mewat regions), Maru (= desert) in the west, and 'Parin' (?) in the east. This roughly

corresponds to the modern state of Haryana in India.

6. Satapatha Brahmana IX.5.1 and Pururava-Urvasi Narrative

The Satapatha Brahmana XI.5.1 is very clear that the wanderings of Pururava, the re-union with Uravashi (and from context, their initial cohabitation) were all in the Kurukshetra region (and not in W Punjab or anywhere further west). Another point to note is that Pururava is said to be the son of Ila, a deity again closely linked to the

Kurukshetra region and Sarasvati. Let me reproduce the relevant passages from the Satapatha Brahmana XI.5.1, as translated by Julius Eggeling [1900(1963): 68-74]:

"Then, indeed, she vanished: 'Here I am back,' he said, and lo! She had vanished. Wailing with sorrow he wandered all over Kurukshetra. Now there is a lotus-lake there, called Anyatahplaksha: He walked along its bank; and there nymphs were swimming about in the shape of swans. XI.5.1.4

At this stage, the text reproduces some verses from Rgveda X.95, which contain the Pururava-Uruvasi dialog, ending with Rgveda X.95.16. The narrative continues:

"This discourse in fifteen verses has been handed down by the Bahvrikas. Then her heart took pity on him. XI.5.1.10

She said, 'Come here the last night of the year from now; then shalt thou lie with me for one night, and then this son of thine will have been born.' He came there on the last night of the year, and lo, there stood a golden palace! They then said to him only this (word), 'Enter!' and then they bade her go to him. XI.5.1.11

She then said, 'Tomorrow morning the Gandharvas will grant thee a boon, and thou must make thy choice.' He said, 'Choose thou for me!' -- She replied, 'Say, Let me be one of yourselves!' In the morning the Gandharvas granted him a boon; and he said, 'Let me be one of yourselves!' XI.5.1.12

They said, 'Surely, there is not among men that holy form of fire by sacrificing wherewith one would become one of ourselves.' They put fire into a pan, and gave it to him saying, 'By sacrificing therewith thou shalt become one of ourselves.' He took it (the fire) and his boy, and went on his way home. He then deposited the fire in the

forest and went to the village with the boy alone. [He came back and thought] 'Here I am back;' and lo! It had disappeared: what had been the fire was an Asvattha tree (ficus religiosa), and what had been the pan was the Sami tree (mimosa suma). He then returned to the Gandharvas. XI.5.1.13[....]"

The mention of a lotus pond at Kurukshetra in the Satapatha Brahmana needs to be noted by the reader because it is consistent with the information provided by Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.45, which also refers to the presence of Pururava and Urvasi by a lotus pond surrounded by Peepul (Asvattha) trees in Kuruksetra, and performance

of rituals at the site. It is clear then, that Urvasi and Pururava themselves were present in Kuruksetra for the birth of Ayu according to the author of both the Satapatha Brahmana and Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44-45. In conclusion therefore, Ayu or his descendants did not migrate to India from Afghanistan according to these texts.

7. Vadhula Anvakhyana Version of the Narrative

The relevant portion of the text has been published only recently, first by Y Ikari (1998:19-23), and more recently by Braj Bihari Chaubey (2001). Based on Ikari's text, Toshifumi Goto (2000) has studied the legend in detail, comparing it with parallel passages in Vedic texts, in particular Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44-45. The

Vadhula Anvakhyana Brahmana 1.1-2 (Chaubey 2001: pp. 34-35, 1-3 of devanagari text) does not add any additional geographical information except stating that Pururava and Urvasi traveled to Urvasi's father's

home for the birth of their son Ayu. This might again be interpreted by Aryan invasionists as proof that Ayu was born in Afghanistan. They would argue that Urvasi was an apsara, and therefore, she belonged to the gandharvas who are sometimes placed in Afghanistan by scholars still believing in the Aryan Invasion Theory (AIT). For instance, Malati Shengde (1977: 111) suggests that the gandharvas were the priests of people who resided in the Kabul valley. Such speculations however are very tentative and tenuous, and do not constitute

evidence of any type. They certainly cannot over-ride rules of Sanskrit grammar in interpreting Sanskrit texts such as Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44. Moreover, the Vadhula text does not mention the separation of Pururava and Urvasi. It does not mention Amavasu or his birth at all, and states instead that Pururava left the home of his

in laws with his son Ayu, and with the knowledge of yajna. The section 1.1.2 of this text explicitly equates Ayu with Agni, that eats food for both humans and the Devas ("....aayurasi iti jaatam abhimantrayate sa vaa esha aayuh pauruuvasa ubhayeshaan devamanushyanaam annaado agnibhagavaan ubhayeshaam..."). It also

states explicitly that Urvasi was actually a human who had been given over to the gandharvas. So much for the Afghani provenance of Urvasi and Pururava!

8. Hertha Krick's study (Krick 1982) on the agnyadheya Rite:

Hertha Krick presents her translation, or rather an interpretation of Baudhayana Srautrasutra 18.44 (p. 214) in her PhD thesis that was published posthumously (Krich 1982). She first suggests that the descendants of Amavasu migrated westwards, but them proposes an alternate interpretation that Amavasu stayed west in his home, and

only Ayu migrated eastwards. Later on too, she refers (page 218-219) to her second interpretation that the descendants of Ayu migrated to Kurukshetra region and thence to other parts of Madhyadesha where Vedic orthodoxy/orthopraxy was established eventually by Brahmins, whereas the Amavasus stayed back in western regions of Gandhara etc. She also links Ayu and his descendants with symbolism related to Moon and Soma, and reproduces passages from later Sanskrit texts on the progeny of Pururava and Urvashi. None of this really sheds light on our problem at hand. It should be noted that the entire work of Krick is written under the Aryan invasionist (AIT) paradigms. Her major argument for situating Urvasi in the Gandhara region is that Urvasi

resided with sheep and goats and rearing of these animals was especially important for residents of Afghanistan and its adjoining areas! Parpola (1980: 8) translates the relevant sentences from German,

"Urvasi calls them (pair of sheep) her children, and becomes desperate when they are robbed, while Pururavas boasts of having 'ascended the sky' through the recapture of the ram. This shows that the generative and fertility power of the royal family and thereby the whole kingdom was dependent upon these sheep. This component of

the tale should be based upon the actual old customs and cultic conceptions of a country subsisting in sheep raising, such as Gandhara....(p. 160)".

But such an argument is not conclusive because sheep and goat herding have been important occupations not just in Afghanistan and North Western Frontier Province region of Pakistan, but also in much of Rajasthan, Punjab and parts of Haryana down to present times. Not surprisingly, scholars who still adhere to AIT and its euphemistic interpretations (such as Aryan migration theory) continue to torture Vedic texts and see 'evidence' for Indo-Aryan migrations into India. Therefore, Krick's interpretations have also found support in her obituary written by Asko Parpola, another scholar who till this day believes not just in one, but in multiple Aryan invasions of India.

Parpola (1980:10) remarks sympathetically:

"Such feasts dedicated to gandharvas and apsarases have been celebrated at quite specific lotus ponds surrounded by holy fig trees in the Kuruksetra. The analysis cited above suggests, however, that the original location of the legend was a country like Gandhara, where sheep-raising was the predominant form of economy. This eastward shift, which is in agreement with the model of the Aryan penetration into India, starting from the mountains of the northwest, is corroborated. Hertha Krick points out, also by the geneology of the peoples as given in the Baudhayana-Srautasutra (18,44-45): while Amavasu stayed in the west (Gandhara), Ayu went to the east (Kuruksetra)."

Likewise, in a later publication, Witzel (2001a) too draws solace from the fact that Krick interprets 'Amavasu' as one who 'keeps his goods at home', and 'Ayu', as 'active/agile/alive'. According to Witzel, Krick and Parpola, BSS 18.44 designates the homeland of Gandharis, Parsus and Arattas as 'here' ('ama' in 'amavasu'). Prima facie, this suggestion is illogical, because the territory inhabited by these three groups of people is a vast swathe of land comprising a major portion of modern-day NWFP/Baluchistan provinces of Pakistan, and much of Afghanistan. To denote such a vast swathe of territory by the word 'here', while contrasting it with supposed migrations of Kurus and other Indian peoples from 'here' to 'there' (= northern India) is somewhat of a stretch. Muni Baudhayana (or whoever wrote BSS 18.44) was definitely a resident of northern India, and for him, Afghanistan and northwestern Pakistan would be 'there', and not 'here' or 'home' (which would be his region of northern India).

Now, in an online paper, Witzel (Witzel 2001: 16, fn. 45) tries to minimize the importance he had placed earlier on BSS 18.44 as the only important 'direct evidence' for an Indo-Aryan immigration. In this paper, Witzel refers to his earlier publication 'Witzel (1980)' as proof that Arattas were 'Arachosians' (= residents of Helmand valley in S W Afghanistan). But when the present author checked this publication (Witzel 1980: fn. 3), it was found to place the Arattas in the Badakhshan area in extreme N E Afghanistan! In other words, Witzel now misquotes his own earlier publication incorrectly while defending his mistranslation!

9. Conclusion- Imposing Colonial Paradigms on Ancient Ritual Passages:

Rather than insisting on seeing evidence for 'movement' or 'migration' in the word 'Ayu', and correspondingly 'remaining in their home' in the word Amavasu, it is perhaps less tortuous to interpret this passage figuratively in a manner that is more consistent with the Indian tradition. How then do we interpret the Vedic narratives about the birth of Ayu and Amavasu? Tradition holds that the Kuru-Panchalas, and later the Kashi-Videhas conformed to Vedic orthoproxy (i.e., they performed fire sacrifices to the Devas) and were therefore 'alive'. On the other hand, the progeny of Amavasu did not sacrifice to the Devas and hoarded their wealth in their homes.

An over-arching theme in the versions of the Pururava-Urvasi legend in the Vedic texts is the semi-divine origin of the Vedic ritual. The yajna is said to have reached mankind through Pururava, who got it from semi-divine beings, the gandharvas, via the intervention of Urvasi, who herself was an apsaraa and belonged to the gandharvas. Coupled with the Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44-45 passage, we may interpret the names of Ayu and Amavasu to mean that the former represents the mythical ancestor of peoples (Kuru-Panchalas and Kasi-Videhas) who are 'alive and bright', and 'vibrant' or 'moving'because they sacrificed to the Devas. Vadhula Anvakhyana 1.1.1

explicitly declares that before the birth of Ayu, humans did not perform Yajna properly due to which they had developed only the trunk part of their body and not their limbs- "...naanyaani kaani chanaangaani...". In contrast, the Gandharis, Parsus and Arattas did not perform Vedic sacrifices for Devas and hoarded their 'possessions in their homes', due to which they were 'stationary' or 'dead' and 'devoid of light', like the 'amavasya' or moonless night. This interpretation would be completely consistent with later traditions concerning the conformity to Vedic orthopraxy by the Kurus, Panchalas, Kashis and Videhas; and the lack of the same in the case of Arattas, Gandharis and Parshus. In 'modern idiom', the former group are progeny of 'fire' or 'light', and the latter are progeny of 'darkness' and 'death' from the perspective of Vedic orthopraxy.

Whatever be the ritual interpretation of this passage, there is no convincing way to uphold Witzel's mistranslation or over- interpretation of Baudhayana Srautasutra 18.44. One must be extremely wary of using at least the Vedic versions of this legend to construct real history of human migrations, otherwise we would have to deduce

an outward from India towards Central Asia. There is absolutely no need to read modern and colonial Aryan invasion and migration theories into ancient ritual texts. Therefore, we may conclude there still exists no Vedic evidence for an Aryan immigration into India. All such attempts by Witzel (and following him R Thapar, and R S

Sharma) must be considered as over-zealous misinterpretations eventually derived from colonial theories such as the Aryan invasion theory. Eminent historians must not fall into the trap of seeing 'evidence' for Aryan migrations or invasions in texts that are chronologically removed by a 1000 years from the period of these supposed demographic movements. Doing so is bad historiography and not just a case of "when one looks for them, there are evidence for migration" (Thapar 1999). The Vedic texts, comprising of several thousand pages of printed texts, indeed do not have a single statement may serve as literary evidence for AIT or AMT unless one wants to imagine evidence that does not exist.

Acknowledgements: At my request, Koenraad Elst translated the Dutch passage in Caland (1903:58), while Nitin Agrawal (my younger brother) consulted Kashikar (2003: 1235) promptly. Professor Shiva Bajpai provided several useful suggestions, although all errors are mine. The paper was presented at the World Association For Vedic Studies' conference at Houston (USA) held on 8-10 July 2006.

Bibliography

Agarwal, Vishal. 2001. The Aryan Migration Theory, Fabricating Literary Evidence, available at

Blazek, Vaclav. 2002. 'Elamo-Arica'. In The Journal of Indo-European Studies, Vol. XXX, Nos. 3-4 (Fall/Winter 2002): 215-242

Caland, Willem. 1903-1913. The Baudhayana srauta sutra belonging to the Taittiriya samhita (3 vols.). Calcutta: Bibliotheca Indica

_____. 1903. "Eene Nieuwe Versie van de Urvasi-Mythe". In Album-Kern, Opstellen Geschreven Ter Eere van Dr. H. Kern. Leiden: E. J. Brill (pp. 57-60)

Cardona, George. 2000. Message no. 3 (dated April 11, 2000) in the public archives of the Sarasvati Discussion list. (The website of the discussion list was

http://sarasvati.listbot.com/. The list is now defunct and messages are no longer available).

Chaubey, Braj Bihari. 2001. Vadhula-Anvakhyanam, Critically edited with detailed Introduction and Indices. Hoshiarpur: Katyayan Vaidik Sahitya Prakashan

Dandekar, R. N. (ed). 1958. Srautakosa, Volume I, Part I, English Section. Poona: Vaidik Samsodhana Mandala

Eggeling, Julius. 1900. The Satapatha-Brahmana according to the Text of the Madhyandina School, Part V. London: Clarendon Press. Repr. By Motilal Banarsidass (Delhi), 1963

Elst, Koenraad. 1999. Update the Aryan Invasion Debate. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan

Goto, Toshifumi. 2000. 'Pururavas und Urvasi" aus dem neuntdecktem Vadhula-Anvakhyana (Ed. Y. Ikari)'. In Tichy, Eva and Hintze, Almut (eds.), Anusantatyai, Germany: J. H. Roll (pp. 79-110)

Ikari, Yasuke. 1998. "A Survey of the New Manuscripts of the Vadhula School -- MSS. of K1 and K4-" In ZINBUN, no. 33: 1-30

Kashikar, Chintamani Ganesh. 2003. Baudhayana Srautasutra...

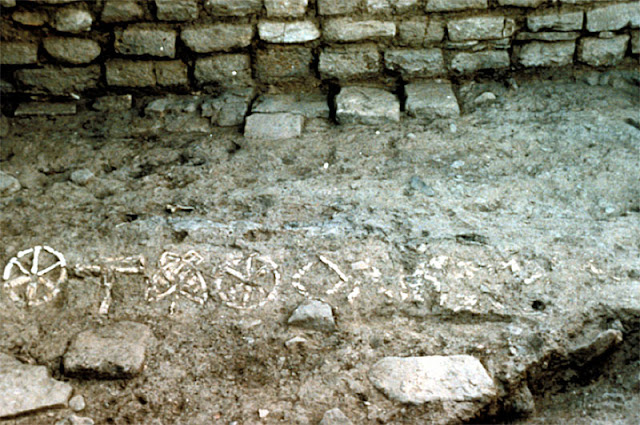

![clip_image057[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0574-thumb.jpg?w=80&h=68)

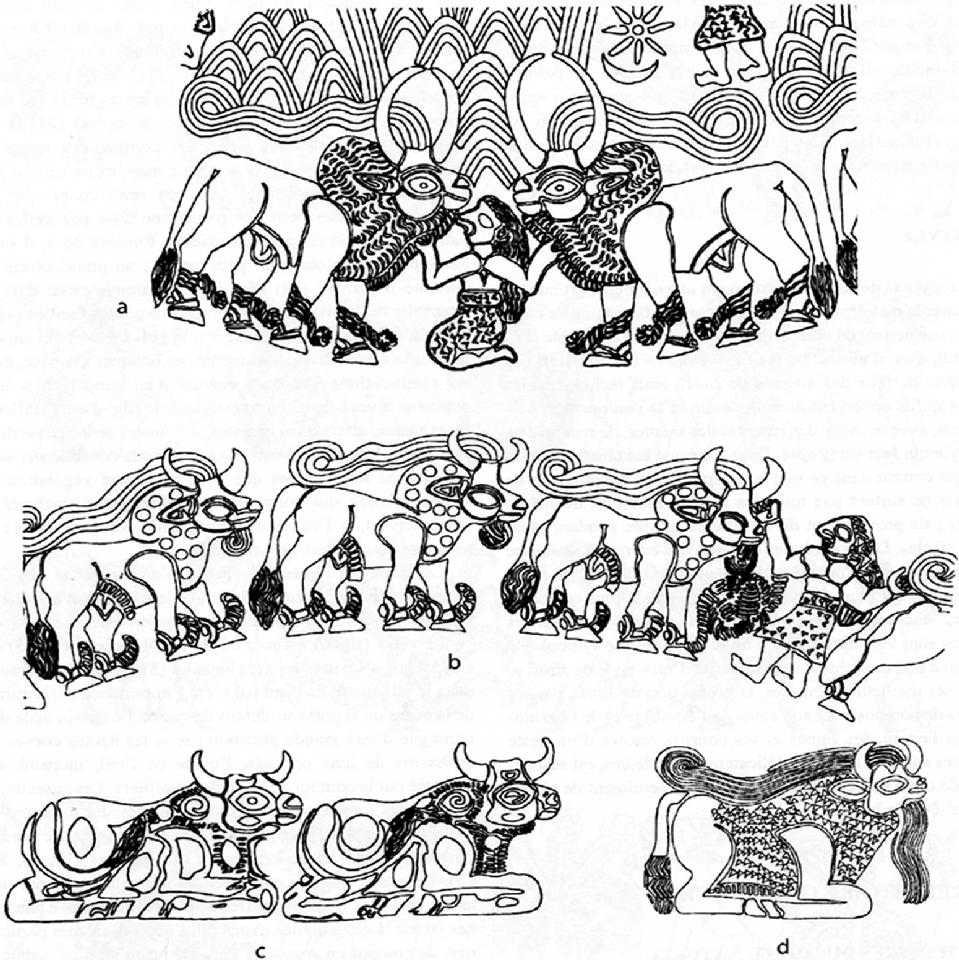

Bharhut sculptural frieze.

Bharhut sculptural frieze.

BMAC artefacts. फड, phaḍa 'cobra hood' फड, phaḍa 'Bhāratīya arsenal of metal weapons'. Shaped like a bag or wallet with handle. dhokra 'wallet, basket' rebus; dhokra 'cire perdue metal caster'.

BMAC artefacts. फड, phaḍa 'cobra hood' फड, phaḍa 'Bhāratīya arsenal of metal weapons'. Shaped like a bag or wallet with handle. dhokra 'wallet, basket' rebus; dhokra 'cire perdue metal caster'.

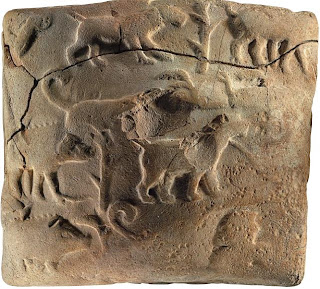

m1405 Pict-97 Reverse: Person standing at the centre pointing with his right hand at a bison facing a trough, and with his left hand pointing to the Sign 15. Obverse: A tiger and a rhinoceros in file.

m1405 Pict-97 Reverse: Person standing at the centre pointing with his right hand at a bison facing a trough, and with his left hand pointing to the Sign 15. Obverse: A tiger and a rhinoceros in file.  Ganweriwala tablet. Kneeling adorant.

Ganweriwala tablet. Kneeling adorant.

Harappa tablet

Harappa tablet

m0478A

m0478A m0478B tablet

m0478B tablet

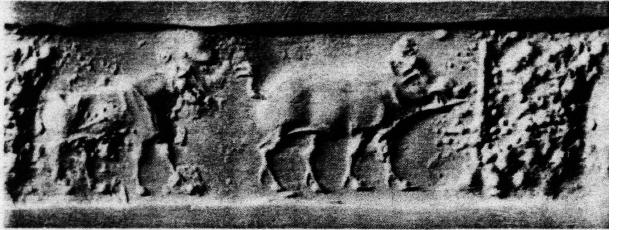

Fig.1 and 2: Indus Seals with Vratya Figures

Fig.1 and 2: Indus Seals with Vratya Figures Fig 3. Harappan Seal of Kalibangan

Fig 3. Harappan Seal of Kalibangan Fig. 4: Rudra as Vratyapati with his Bow Pinaka, also called Jyadroda

Fig. 4: Rudra as Vratyapati with his Bow Pinaka, also called Jyadroda

L

L

Figure 1. A box plot showing the three modeled components of Indian Ancestry for the 140 populations studied by the authors. The gray line indicates the position of the genuine brāhmaṇa population with the lowest steppe ancestry (i.e. leaving out some groups which are not conventional brāhmaṇa, e.g. viśvakarman). It is clear that the brāhmaṇa-s show above average steppe ancestry and below average Indian hunter-gatherer ancestry.

Figure 1. A box plot showing the three modeled components of Indian Ancestry for the 140 populations studied by the authors. The gray line indicates the position of the genuine brāhmaṇa population with the lowest steppe ancestry (i.e. leaving out some groups which are not conventional brāhmaṇa, e.g. viśvakarman). It is clear that the brāhmaṇa-s show above average steppe ancestry and below average Indian hunter-gatherer ancestry. Figure 2. The same data is represented as a histogram. It is clear that whereas the Indus-periphery and Indian Hunter-gatherer ancestry is unimodal, the steppe ancestry is not with groups showing low and high steppe ancestry. This explains the authors’ earlier model of ASI and ANI.

Figure 2. The same data is represented as a histogram. It is clear that whereas the Indus-periphery and Indian Hunter-gatherer ancestry is unimodal, the steppe ancestry is not with groups showing low and high steppe ancestry. This explains the authors’ earlier model of ASI and ANI. Figure 3. Ternary diagram of the 3 strands of Indian ancestry. The 5 caste-tribal groups defined above are colored: 1-red, 2-orange, 3-aquamarine; 4-blue; 5-violet. One can see the effect of the two admixtures with the steppe ancestry’s effect being predominant in the varṇa populations.

Figure 3. Ternary diagram of the 3 strands of Indian ancestry. The 5 caste-tribal groups defined above are colored: 1-red, 2-orange, 3-aquamarine; 4-blue; 5-violet. One can see the effect of the two admixtures with the steppe ancestry’s effect being predominant in the varṇa populations. Figure 4. A box plot of the inferred steppe ancestry in the above-defined five groups. The steppe ancestry is arrayed in accordance with the caste ladder and tribals have the least of it on an average.

Figure 4. A box plot of the inferred steppe ancestry in the above-defined five groups. The steppe ancestry is arrayed in accordance with the caste ladder and tribals have the least of it on an average. Figure 5. A box plot of the inferred Indus-periphery ancestry in the above-defined five groups. It is interesting to note that unlike the steppe ancestry’s the Indus-periphery ancestry is greater in the warrior and middle caste groups than in braḥmaṇa-s, who have a lower median value of this component. However, this difference is only mildly significant in the current data (p=.033) and sampling bias cannot be ruled out.

Figure 5. A box plot of the inferred Indus-periphery ancestry in the above-defined five groups. It is interesting to note that unlike the steppe ancestry’s the Indus-periphery ancestry is greater in the warrior and middle caste groups than in braḥmaṇa-s, who have a lower median value of this component. However, this difference is only mildly significant in the current data (p=.033) and sampling bias cannot be ruled out. Figure 6. A box plot of the inferred Indian hunter-gatherer ancestry in the above-defined five groups. Here for the four groups from the warrior castes to the tribes we see a reverse of the scenario seen for the steppe ancestry. However, the braḥmaṇa-s show a slightly higher median value of this component. While again we should be clear that this could be due to sampling bias, taken together with the above plot, it might reflect some sociological reality. The braḥmaṇa-s probably to start with did not mix much with the preexisting populations of the subcontinent but as they expanded, especially while moving south, they mixed with directly with populations with lower Indus-periphery and higher hunter-gatherer components.

Figure 6. A box plot of the inferred Indian hunter-gatherer ancestry in the above-defined five groups. Here for the four groups from the warrior castes to the tribes we see a reverse of the scenario seen for the steppe ancestry. However, the braḥmaṇa-s show a slightly higher median value of this component. While again we should be clear that this could be due to sampling bias, taken together with the above plot, it might reflect some sociological reality. The braḥmaṇa-s probably to start with did not mix much with the preexisting populations of the subcontinent but as they expanded, especially while moving south, they mixed with directly with populations with lower Indus-periphery and higher hunter-gatherer components.

A Gold Rhyton with two tigers; svastika incised on thigh of tiger; found in historical site of Gilan

A Gold Rhyton with two tigers; svastika incised on thigh of tiger; found in historical site of Gilan

Banawari. Seal 17. Text 9201. Hornd tiger PLUS lathe + portable furnace.

Banawari. Seal 17. Text 9201. Hornd tiger PLUS lathe + portable furnace.

Slide7

Slide7