https://tinyurl.com/y5yqmxeh

-- Kuviran of Keeladi (identified in Tamil Brahmi) and an oval carnelian ring with বরা 'boar' of rebus badaga 'artificer' of Keeladi (Tamil Nadu, 6th cent. BCE)

-- Dwaraka is a site where a turbinella pyrum seal was found with a composite animal with protomes of bull, antelope (or markhor) and one-horned young bull

कोंद kōnda 'young bull' rebus: कोंद kōnda 'engraver, turner, smelter.' कोंद kōnda 'kiln, furnace';khoT 'alloy metal, wedge' PLUS singhin 'spiny horned' rebus: singi 'ornament gold' PLUS Tor. miṇḍ 'ram', miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (CDIAL 10310)Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic languages); (Vikalpa: ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin ore'); barad, balad'ox' rebus: baran, bharat 'mixed alloys' (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

-- Carnelian ring with Meluhha rebus reading, badhia 'boar' rebus: badaga 'artificer'.

The presence of a carnelian ring of Keeladi and varieties of gemstones and beads found at the site links the settlement to Gujarat and the traditions of lapidary- and metal-work of Sarasvati Civilization. The link of ancient Tamil kings with Dwaraka of Gujarat is attested in an ancient Sangam text. See Annex Reference to Dwaraka as Tuvarai in an ancient Sangam text.

Keeladi is an archaeological site which is a continuum of Sarasvati Civilization, a site dated to ca. 6th cent. BCE.

Carnelian is called akki-k-kal * அக்கிக்கல் akki-k-kal , n. akṣi +. Cornelian, a kind of chalcedony; ஸ்படிக வகை (Tamil).अकीक akīka m ( A) A carnelian.(Marathi)

TN Archaeological Society reports a potsherd with an inscription which reads in Tamil Brahmi, Kuviran, a phonetic variant of Sanskrit Kubera.(Keeladi An Urban Settlement Of Sangam Age by TN Archeological Society p.14). The name signifies that the owner of the ring used it as a seal for trade transactions in wood and iron, belongs to a rich artificer. কুবের kubēra: the Hindu god of wealth (cp. Pluto, Mammon). ̃পুরী n. the abode or city of Kuvera (কুবের) which is full of wealth and pomp and grandeur. ̃সদৃশ, ̃তুল্য a. as rich as Kuvera (কুবের); extremely wealthy, very rich.(Bengali) Yakkha [Vedic yakṣa]. They stand in a close relationship to and under the authority of Vessavaṇa (Kuvera), one of the 4 lokapālas. They are often the direct servants (messengers) of Yama himself, the Lord of the Underworld (and the Peta -- realm especially). Cp. D ii. 257; iii. 194 sq.; J iv. 492 (yakkhinī fetches water for Vessavaṇa); vi. 255 sq. (Puṇṇaka, the nephew of V.); VvA 341 (Serīsaka, his messenger). In relation to Yama: dve yakkhā Yamassa dūtā Vv 522; cp. Np. Yamamolī DhA iv. 208. -- In harmony with tradition they share the rôle of their master Kuvera as lord of riches (cp. Pv ii. 922) and are the keepers (and liberal spenders) of underground riches, hidden treasures etc., with which they delight men. (Pali) See: कुवेर न० कुत्सितं वेरमस्य । धनदे उत्तरदिक्पाले देवभेदे कुबेरशब्दे विवृतिः कुवेरोत्पत्यादिकं रामा० उ० का० (https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/वाचस्पत्यम्) कुवेरः, पुं, (कुत्सितं वेरं शरीरमस्य ।) तथा च वायु-मार्कण्डेयपुराणे ।(https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/शब्दकल्पद्रुमः)

Another inscription just reported is a carnelian ring with a glass boss bearing the inscription of a boar. Meluhha rebus reading of the boar is: baḍhia 'a boar' rebus: baḍhi 'worker in iron and wood', baḍhoria'expert in working in wood'.বরা2 barā2: the boar, the hog.বরাহ barāha: the boar, the hog; the third incarnation of Vishnu (বিষ্ণু) when he slew Bara (বরা) the demon. fem. বরাহী the sow (Bengali) baḍaga 'artisan'. బత్తుడు

battuḍu 'a guild, title of goldsmiths' baḍaga 'a professional title of five artificers'. In Sanskrit, the refined etymon is: varāha.Varāha [Vedic varāha & varāhu, freq. in Rigveda] a boar, wild hog Dh 325=Th 1, 17; J v. 406=vi. 277; Miln 364; Sdhp 378.(Pali) varāhá -- , varāˊhu -- m. ʻ wild boar ʼ RV. Pa. Pk. varāha -- m. ʻ boar ʼ; A. B. barā ʻ boar ʼ (A. also ʻ sow, pig ʼ), Or. barāha, (Sambhalpur) barhā, (other dial.) bā̆rihā, bāriā, H. bā̆rāh m., Si. varā. varāhamūla -- .varāhamūla n. ʻ name of a place in Kashmir ʼ Rājat. [varāhá -- , mūˊla -- ?] K. warahmul ʻ a town at west end of the valley of Kashmir ʼ.(CDIAL 11325, 11326) warāh वराह॒ । सूकरः m. a boar, pig (wild or domesticated); the third, or boar, incarnation of Vishnu (Śiv. 856).(Kashmiri) See the pronunciation variants of the semantics of 'boar' in Indian sprachbund (speech union) or Indian Linguistic Area;

I submit the pre-Common Era etymon is likely to pronounce closer to the Santali etymon baḍhia 'castrated boar'.

బత్తుడు battuḍu báḍḍhi वर्धकि, vaḍlaṅgi, baṛhaï, baḍaga, baḍhi, bāṛaï, varāha, 'title of five artisans' phaḍa फड, paṭṭaḍa 'metals manufactory' venerated in Indus Script https://tinyurl.com/yct26xc6

Scores of pronunciation variants presented for the etymon బత్తుడు battuḍu 'worshipper''artificer title' are characteristic of Meluhha (cognate mleccha) pronunciation variants commented upon by early linguists such as Patanjali. Meluhha is cognate mleccha. Mleccha are island-dwellers (attested in Mahabharata and other ancient Indian sprachbund texts). Their speech does not conform to the rules of grammar (mlecchāḥ mā bhūma iti adhyeyam vyākaraṇam) and had dialectical variants (variant pronunciations) in words (mlecchitavai na apabhāṣitavai) (Patanjali: Mahābhāṣya).

Unfortunately, the photograph is not legible. The legend provided by the photographer and reporter in TOI of Nov. 2, 2019 reads: "An enlarged image of an oval-shaped carnelian ring with incised boar displayed at the temporary Madurai museum for Keeladi artifacts inaugurated by the CM on Friday (1 Nov. 2019)." Source: Times of India, Chennai Edition, page 1, report titled: Rs. 12-crore museum in Sivaganga to showcase Keeladi artifacts.

Map showing Vaigai river (Keeladi settlement is on the banks of Vaigai river in Sivaganga district)

Key Findings – Keeladi Excavation (201702018 season)

Excavation work, during this season had yielded 5820 antiquities with enough cultural traits in the form of structural activity (brick structures, terracotta ring wells, fallen roofing tiles with double holes and deeply finger pressed grooves to draw rain water).

Antiquities like few pieces of golden ornaments, broken portions, copper objects, iron implements, terracotta gamesmen (chessman), hop scotches, ear ornaments, spindle whorls, figurines and portions besides beads of terracotta, glass, semi-precious stones (agate, carnelian, crystal, etc.).

Popular ceramic types like finer variety of Black and Red ware, Black ware, Black Polished ware, Red ware, Rouletted ware, few pieces of Arretines were also found. There are also enough numbers of graffiti sherds of both pre and post firing nature. A good number of Tamil Brahmi sherds also have been unearthed.

Analysed AMS (Accelerator mass spectrometry) dates. Six carbon samples were sent to Beta Analytic Lab in the US for AMS dating. The dates of all six samples fell between 6th cent. BCE and 3rdcentury BCE, according to T. Udhayachandran, Commissioner, Dept. of Archaeology, Tamil Nadu Govt. Result was released after consulting with scholars like K Rajan, who also agreed that Keeladi presented strong evidence to some of the hitherto held hypotheses All these finds clearly indicate the cultural richness of the ancient civilization of the Tamils of this region having its close proximity to the temple city Madurai. Hence it becomes essential to continue to probe such cultural hidden treasures of Keeladi site in future and reveal the cultural wealth of the ancient Tamil society.

Keeladi museum, Dinamalar, 2 Nov. 2019

Part of ring well found intact at KeeladiRing well, about 4 ft. high; 4 rings; each ring measures about 1 ft. About 8 ring wells have been discovered.

Floor of a channel paved with burnt bricks, thought to be a continuation of a similar structure (tank?) excavated by ASI in 2016. Channel with breadth of about one metre may be extension of a tank.

Lives of people who lived at the site on the banks of Vaigai river, about 2600 years ago. "The Tamil Nadu state archaeology department analysed AMS (Accelerator mass spectrometry) dates. Six carbon samples were sent to Beta Analytic Lab in the US for AMS dating. The dates of all six samples fell between 6th cent. BCE and 3rdcentury BCE, according to T. Udhayachandran, Commissioner, Dept. of Archaeology, Tamil Nadu Govt. Result was released after consulting with scholars like K Rajan, who also agreed that Keeladi presented strong evidence to some of the hitherto held hypotheses.

Read more at:

Artefacts on display in the Museum, World Tamil Sangam building, Madurai include:

Orange carnelian stone with wild boar engraved on it; it is a stamp, balanced on top of a glass holder; a seal

Shell ornaments

https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/madurai/part-of-ring-well-found-intact-at-keeladi/articleshow/70461639.cmsKeeladi: Unearthing the 'Vaigai Valley' Civilisation of Sangam era Tamil Nadu

Excavations in the tiny hamlet of Keeladi prove that an urban civilisation existed in Tamil Nadu in the Sangam era on the banks of the river Vaigai. What links did this civilisation have with the Indus Valley Civilisation? S. Annamalai reports on the findings and the questions and answers they have thrown up

In the last week of September 2019, Keerthi Jeyaraj, Director of EduRight Foundation, flew from Texas, the U.S., to Pallichandai Thidal, a nondescript mound at the far end of Keeladi, a tiny hamlet located 12 km southeast of the historic city of Madurai in Tamil Nadu. The next week, three Sri Lankan Tamils arrived at the same spot. It was their second visit to the excavation site. Also on his way by rail was Chennai-based documentary filmmaker Amshan Kumar. To accommodate these visitors and thousands more, a temporary parking lot was created in Keeladi. A stall selling snacks and coffee sprung up at what looked like a new picnic spot.

An astonishing 1.16 lakh people visited the site between September 20 and October 10. The visitors flocked to the hamlet in curiosity and fascination following the publication of a report by the Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology (SDA) on September 18. Earlier, carbon samples from Keeladi had been sent to the Beta Analytic Lab in Miami, Florida, for carbon dating, a widely accepted tool to ascertain the age of archaeological and historical remains. The Lab had found that the cultural deposits unearthed during the fourth excavation at Keeladi in Sivaganga district could be safely dated to a period between 6th century BCE and 1st century CE. These place Keeladi artefacts about 300 years earlier than previously believed.

Findings over the years

The Keeladi tale began to unravel in March 2015. The first round of excavation, undertaken by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), unearthed antiquities that “may provide crucial evidence to understanding the missing links of the Iron Age [12th century BCE to 6th century BCE] to the Early Historic Period [6th century BCE to 4th century BCE] and subsequent cultural developments.”

The second round (2016) threw up strong clues about the existence of a Tamil civilisation that had trade links with other regions in the country and abroad. This civilisation has been described by Tamil poets belonging to the Sangam period. (Tamil Sangam, an assembly of poets, had its seat in Madurai between 4th century BCE and 2nd century BCE. The works of this period are collectively called Sangam Literature). This round was significant as it provided archaeological evidence about what was found in Tamil literature. Results of carbon dating of a few artefacts, which were released in February 2017, traced their existence to 2nd century BCE (the Sangam period).

The third round (2017) saw a delayed start. First, the excavation report was submitted late. Then the Superintending Archaeologist, K. Amarnath Ramakrishna, was transferred, in a perceived attempt to play down the excavation findings. Keeladi almost faded from public memory as there was no “significant finding” in the third round. This led to criticism that the excavation had been deliberately restricted to 400 metres. On the intervention of the Madurai Bench of the Madras High Court, ASI permitted the SDA to take up further excavation on its own. Thus, the excavations in the fourth round were carried out by the SDA.

In the fourth round (2018), 5,820 antiquities were found. These included brick structures, terracotta ring wells, fallen roofing with tiles, golden ornaments, broken parts of copper objects, iron implements, terracotta chess pieces, ear ornaments, spindle whorls, figurines, black and redware, rouletted ware and a few pieces of Arretine ware, besides beads made of glass, terracotta and semi-precious stones.

A sense of history

The recent dating is very significant, says K. Rajan, archaeologist at the Department of History, Pondicherry University. “Based on radiometric dates recovered from archaeological sites like Kodumanal, Alagankulam and Porunthal [all in Tamil Nadu], we know that Tamili [the Tamil-Brahmi script] was dated to 5th century BCE. But the recent scientific dates obtained from the Keeladi findings push back the date by another century,” he writes in the SDA publication, Keeladi: An Urban Settlement of Sangam Age on the Banks of River Vaigai.

Commenting on the Keeladi findings, Dilip K. Chakrabarti, Emeritus Professor of South Asian Archaeology, Cambridge University, observes in an e-mail note sent to Rajan on September 26 that the recent excavations conducted in the State, including in Kodumanal and Porunthal, which have been “strengthened by a large number of radiocarbon dates, have brought about a sea-change in our understanding of the archaeological developments in Tamil Nadu, taking our gaze from megalithic burials and the finds of Roman coins to megalithic habitation sites and their chronological developments.”

The fifth round (2018-19), which ended on October 13, was a game changer. The SDA plunged into “guided excavation” using the Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Survey, the Magnetometer Survey and the Ground Penetrating Radar Survey. “We wanted to blend technology with traditional wisdom in Keeladi. The lessons learnt are significant and the results are good. We are positioning archaeology as a multidisciplinary and transdisciplinary area of knowledge,” says T. Udhayachandran, Principal Secretary, Department of Archaeology. Guided excavation has led to the discovery of a lot of structures this round. The report for this is being prepared.

The Vaigai Valley Civilisation

The Keeladi findings have led academics to describe the site as part of the Vaigai Valley Civilisation. The findings have also invited comparisons with the Indus Valley Civilisation. A researcher of the Indus Valley Civilisation and retired civil servant, R. Balakrishnan, points to the similarities in urban planning between the Indus Valley and Keeladi. Rajan refers to the cultural gap of 1,000 years between the two places: “This cultural gap is generally filled with Iron Age material in south India. The graffiti marks encountered in Iron Age sites of south India serve as the only residual links between the Indus Valley Civilisation and south India.” Some of the symbols found in pot sherds of Keeladi bear a close resemblance to Indus Valley signs. Graffiti marks are found in earthenware, caves and rocks in or near the excavation sites of Tamil Nadu. The Tamil Brahmi script, found engraved on the outer surface or the shoulder of black and red earthenware in Keeladi, carries personal names, say archaeologists. According to the SDA report, “One of the sherds carries the vowel ‘o’ at the beginning of the name which is rarely found in both cave and pottery inscriptions.”

Udhayachandran affirms that the qualification of Keeladi as an urban habitat cannot be questioned as it reflects all the characteristics of an urban civilisation, with brick structures, luxury items and proof of internal and external trade. An interesting feature of Keeladi is that it has not revealed any signs of religious worship in all the five rounds. Till now, it has been a tale of an industrious and advanced civilisation that celebrated life. The artefacts unearthed at Keeladi are evidence of this. Recent finds include seven gold ornaments, copper articles, gem beads, shell and ivory bangles, and brick structures that point to the existence of industrial units. Structures that could have been used to convey molten metal or filter liquid strongly point to the existence of people who were involved in industrial work.

The SDA report concludes that the “recent excavations and the dates arrived at scientifically clearly suggest that the people were living in Tamil Nadu continuously... and the Keeladi excavation [has] clearly ascertained that they attained literacy or learnt the art of writing [Tamil-Brahmi] in as early as 6th century BCE during [the] Early Historic Period.”

A sophisticated urban settlement

For Balakrishnan, Keeladi is significant for many reasons. It has given evidence of urban life and settlements in Tamil Nadu during the Early Historic Period. It was around this time that evidence for a second urbanisation started appearing in the Gangetic Valley. Keeladi has added greatly to the credibility of Sangam Literature. At the same time, he cautions that we should not feel intimidated by the ‘spatial-temporal gaps’ of 1,300 years and 1,500 km between the Indus Valley Civilisation and Keeladi.

To substantiate this point, he recalls the observations made by K. N. Dikshit in 1939 when he was Director General of ASI: “Considering that the conch shell, typical of the Indus Valley civilisation, and which seems to have been in extensive use in Indus cities, was obtained from [the] south-east coast of the Madras Presidency, it would not be too much to hope that a thorough investigation of the area in Tinnevelly District and the neighbouring regions such as the ancient seaport of Korkai will one day lead to the discovery of some site which would be contemporary with or even little later than the Indus civilisation.” This is exactly what has happened in Keeladi. Twenty-three bangle pieces made of shell and glass were found in the fourth round. Another Director General of ASI, B.B. Lal, had suggested in 1960 a possible link between the undeciphered Indus signs and the graffiti marks on black and red ware pottery of Tamil Nadu.

“Technology helped to fine-comb the search for structures in this round. The most significant find is the continuous brick structure that runs over 340 metres,” says B. Asaithambi, excavation in-charge at Keeladi. Over 900 antiquities, including unique signature Carnelian beads, were unearthed during this round.

At the end of the third round of excavations, an ASI official is said to have told a team of High Court judges who visited Keeladi that the excavated artefacts did not give a clear indication of the nature of settlement as urban or industrial.

But artefacts from the fourth round proved that Keeladi was indeed an urban habitation. Seventy samples of animal skeletal fragments, which were tested by the Deccan College Post Graduate and Research Institute, Pune, show 53% of them belonging to oxen, cows, buffaloes and goats. This indicates that the habitants were predominantly cattle-rearing people. Balakrishnan is excited about the presence of oxen and cows belonging to the Bos indicus species. The hump of the Bos indicus species is referred to as imil in Tamil literature, which later came to be known as timil. The grandeur of this species, which was also present in the Indus Valley, lies in its hump, points out Balakrishnan. Bos indicus is also the icon of the ancient sport eru thazhuvuthal or eru anaithal (embracing the bull), which was prevalent in villages around Keeladi. In this sport, now practised as jallikattu, the contestant is supposed to hold on to the hump of the bull inside the arena for a particular distance or period of time.

The State Department of Archaeology’s comparison of graffiti found in Keeladi with Indus Valley signs

Analysis of samples of materials used in the construction of walls, sent to the Vellore Institute of Technology, has shown that every specimen contained elements like silica, lime, iron, aluminium and magnesium. “The long survival of these materials is due to the quality of material deployed in construction activities,” says the SDA report. More significant are the letters engraved on pots that clearly demonstrate the “high literacy level of the contemporary society that survived in 6th century BCE.”

It is inferred from the spectroscopic analysis of black and red ware by the Earth Science Department of Pisa University, Italy, that “the potters of Keeladi were familiar with the technique [of using carbon material for black colour and hematite for red] and knew the art of raising the kiln temperature to 1100°C to produce the typical black-and-red ware pottery.” They had also followed the same technique and materials from 6th century BCE to 2nd century BCE. “A few pottery samples of 2nd century BCE do contain earth content similar to that of other regions, thereby suggesting that they exchanged goods with neighbouring regions, probably through traders, craftsmen and visitors,” says the SDA report. The antiquities, taken together, suggest that the prime occupation of the people of Keeladi was agriculture, which was supplemented by the iron industry, carpentry, pottery-making and weaving.

Expanding sites

There is already a demand in the region to expand the excavation to more areas along the Vaigai so that there is archaeological evidence to prove the glory of life along the river in the ancient Pandya kingdom. Noted epigraphist V. Vedachalam supports the idea of an extended excavation beginning in Madurai. More evidence could be unearthed to re-establish the antiquity of Madurai and its relationship with towns and villages along the Vaigai. Su. Venkatesan, winner of the Sahitya Akademi award for his book on Madurai, Kaaval Kottam, and who represents Madurai in the Lok Sabha, wants the Union government to recognise Keeladi and its surrounding villages as a heritage cluster and declare Keeladi as a protected monument.

Udhayachandran says that the State government has already approached ASI to declare five villages — Keeladi, Agaram, Manalur, Konthagai (a burial site) and Pasiapuram — as the Keeladi cluster. The sixth round of excavation is expected to commence in mid-January. The State government has also decided to continue excavation in other sites and scientifically prove the link among places such as Adichanallur, Alagankulam and Mangulam.

Importance of carbon dating

Is carbon dating enough to establish Keeladi as the centre of the ‘Vaigai Valley Civilisation’ or connect it to the Indus Valley Civilisation? Researchers caution that unverified claims or positions may derail the effort at revisiting history. Udhayachandran says, “We have placed the available archaeological evidence before the intellectual community to ponder, discuss and arrive at a conclusion by comparing them with literary references.” He says more guidance and collaboration is required to come to conclusions on Keeladi. “It looks like we are sitting on a major city. We need corroborative evidence. We want to bring in more experts. People have a fundamental right to own history. That is why we have maintained transparency in the Keeladi excavations,” he says.

Recalling the late epigraphist Iravatham Mahadevan’s observations about the continuity of Indus legacies in old Tamil traditions, Balakrishnan says that the unassailable identical place name clusters suggest that the Indus civilisation and the recalled “flashback memories” of Sangam Tamil texts are closely interlocked. However, more excavations have to be carried out in the Vaigai and Tamirabarani regions to conclusively figure out how close the the Vaigai civilisation was to the Indus Valley in “temporal terms”. More excavations in the region are required, he says, along with timely submission of reports.

Many institutions of higher learning have come forward to collaborate with the SDA in the scientific analysis of Keeladi’s artefacts. Madurai Kamaraj University is in the process of finalising its plans to conduct a DNA analysis of bones. R.M. Pitchappan, renowned scientist who has worked as Regional Director for National Geographic Corporation’s Genographic Project, which traced the origin and migration of man, will be the mentor for the project. Madurai Kamaraj University, according to him, is now looking at the feasibility of setting up an ancient DNA laboratory in Madurai itself. “Human genomic data of thousands of people are available and scientists from institutions like the Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology, Hyderabad, have past experience in analysis of this data. They can be roped in for interpretation. Technology for DNA sequencing is also available in the country. By comparing ancient DNA with the available samples, one can deconstruct the migrational story of Tamil Nadu in the pre-Sangam period,” says Pitchappan.

The Keeladi excavations have triggered a healthy debate on Indian civilisation and added value to the discipline of archaeology. “Till now, we have been deploying orthodox methods of excavation tempered with our intuition but now technology has given us more strength by proving that our intuitions are right,” says Asaithambi, who has earlier worked in Alagankulam excavation. Keeladi could well be a priceless piece in a massive geographic jigsaw puzzle.

Keezhadi : Does it reflect a non-Vedic Dravidian civilization in ancient Tamil Nadu?

Indology | 12-10-2019

The early Tamil kingdoms were part of one unified civilization which included northern Janapadas as well, and the Tamil kingdoms and ancient sites like Keezhadi were not part of any separate pre-Vedic civilization like Dravidianists wants them to be.

he ancient archaeological site at Keezhadi from Tamil Nadu was in the news recently for it’s latest discoveries on the antiquity of the site, early usage Tamil Brahmi script and graffiti symbols which supposedly has links to the script of the earlier Indus valley civilization. Many reports have gone as far to state that the urbanization in ancient Tamil Nadu started at the same time as in Gangetic regions of northern India, around 6th century BCE. They also state that the pre-Vedic Dravidian people of Indus valley civilization migrated southwards and settled in ancient Tamil lands or Tamilakam to give rise to another civilization which was free from the Vedic influences from north, and that Keezhadi finds reflects this pre-Vedic Tamil civilization. How true are these claims? This write up does an analysis of such claims with factual sources.

Usage of early Tamil Brahmi script

First let’s go through the issue regarding Tamil Brahmi script. What is Tamil Brahmi? One of the veteran epigraphist who spent his lifetime on Tamil inscriptions, late Shri Iravatham Mahadevan, states that Tamil Brahmi was regional script adapted from original Brahmi to suit the needs of Tamil [1]

“The early Tamil cave inscriptions are written in a special regional and linguistic variant of the Brahmi script adapted to the needs of Tamil phonetics. This script, now generally referred to as Tamil-Brahmi, is most probably the one named Damili in the Jaina canonical works Samavayanga Sutta and Pannavana Sutta (assigned to the Pre-Christian Era), and as Dravidahpi in the Buddhist work Lalitavistara (probably written in the early centuries A.D.). “

Mahadevan viewed earlier script of Indus valley civilization as representing Dravidian language, but even he had to admit that Tamil Brahmi is but a modified version of original Brahmi which was used in other parts of the Indian subcontinent. It only means Brahmi script was originally used to write dialects of Prakrit language, which were evolved from Old Vedic Sanskrit or it’s related dialects, which was also the popular language from regions of Afghanistan in north to Deccan in south during the early historic period.

The fact that Prakrit was the original language of Brahmi is further supported by occurrence of many Prakrit inscriptions from early Sangam age Tamilakam. It could only point towards northern origins of Brahmi from Prakrit speaking areas. Archaeologist K. Rajan in his book has written the following [2].

“There are several names of north Indian origin, which are in Prakrit proper. A few are in hybrid form too. The Prakrit names can be recognized by the occurrence of non-Tamil graphemes (aspirants. soft letters, and sibilants) and the genitive case endings like śa, sa, ha. ya. There are several names in pure Tamil like campaṉ , vaḷikaṉ , kannaṉ , antavaṉ n, cuḷantai, māttaṉ , pākaṉ, in Prakrit like nikama, and in Tamilized Pralkrit like kuviraṉ , silikaṉ and makatai. There are certain names like ātaṉ-asaṭaṉ and periyaṉ -sātaṉ , in which, one segment is in Tamil and another segment is in Prakrit or in Tamilized Prakrit. Another interesting feature is that certain names are written differently. For instance, the Prakrit names sāta and tisa are Tamilized by adding alveolar ṉ at the end making the word as sātaṉ and tissaṉ respectively. In another instance. the initial sa in the word sātaṉ is converted into Tamil ca. Likewise, the name tisa is written as tīssaṉ/tissaṉ as well as tissan (the alveolar ending ṉ is replaced with dental n).The writing in both ways like cātaṉ or sātaṉ, clearly suggests that the residents of Kodumanal were familiar with both the languages.

In fact multiple sites dating back to early Sangam age in Tamil Nadu has yielded inscribed Prakrit words. As per K. Rajan, the Prakrit words occurs from earliest layers in Tamil Nadu, going back to 6th century BCE [3]

“Thus, the influence of Prakrit-speaking at lexical and structural levels needs to be studied very closely. However, there is not much room for such structural analysis in Kodumanal inscribed potsherds as 99% of them are very short and mostly carry personal names. We hardly get any evidence of Prakritized Tamil, probably unwarranted in Tamil speaking area. The occurrence of Prakrit names from the lowermost layers of the habitation cuttings suggest that the adaptation process might have taken place well before 6th century BCE. “

Also, supposedly one of the earliest discovered Tamil Brahmi inscription from Tamil Nadu reads as ‘vayra’ which itself is a loan from Sanskrit or Prakrit vajra. So this proves that Tamil Brahmi had Prakrit loans since earliest period [4]

Another thing is that as per the excavation reports, the early Tamil Brahmi inscriptions from Keezhadi itself shows Tamilized loans from Prakrit or Sanskrit such as the name Kuviraṉ. It is ultimately from Sanskrit name Kubera, who is the ruler of Yakshas or nature spirits. [5]

From all these evidences, we can say that early Prakrit loans into Tamil inscriptions from earliest periods shows a crystal clear link with north, and probably that Prakrit loans came from north to south along with the Brahmi script. So in nutshell, the discovery of early Tamil Brahmi inscriptions only pushes back the antiquity of the original northern Brahmi as well.

The link between Indus script symbols and graffities discovered from southern sites.

Now we move on the Graffiti-Indus link. The finds of Indus script-like graffities from Tamil Nadu is nothing new. Over the years, there have been various reports of these Indus script-like finds. However none of them have been verified properly because the graffiti signs occur here and there, that too mostly in isolated cases without any proper sequence like we see in a proper writing system. These signs do occur along with Brahmi letters sometimes, but probably these were trademarks or other sort of marks representing regional marks, industry, clan or tribe etc. To claim that it represents a developed writing system like Indus script is too much, as we don’t have any proper inscriptions in such graffities apart from isolated occurrences. Such graffiti symbols also occurs in iron age cultures of north India. For example as seen in this seal from the ancient city of Vaishali in Bihar [6].

This seal is dated much later than Indus valley civilization. It was commented upon even by Iravatham Mahadevan, who usually endorsed Dravidian authorship of Indus valley civilization, as representing Indus script-like signs [7].

We do not know the exact significance of such symbols. It is true that some symbols does have resemblance to the Indus signs, and even if such graffiti symbols found from southern India indeed derive from Indus script, it doesn’t mean that Indus language was Dravidian. After all the seal from Vaishali is obviously from the era when the region was part of Vedic culture (archaeologists dated it to Mauryan era at the earliest, while Mahadevan comments that it is at least from 1100 BCE). Hence, we can also view that such graffiti symbols came from north to south via historical expansion of the Vedic culture into southern India which had it’s origins from Indus valley, if we identify Indus valley civilization as Vedic or even ancestral to the Vedic culture! Thus the assumption that the Indus-like symbols discovered from southern India indicates a Dravidian migration from Indus valley to southern India is entirely based on the preconceived notion that Indus valley civilization was Dravidian.

A non-Vedic civilization in early Tamilakam?

Finally we come to the most important issue. Since the Keezhadi finds, the Dravidianists have been claiming that Keezhadi represents an independent pre-Vedic secular Tamil civilization which was free of Vedic influences from north.

From the Prakrit loans highlighted previously, it is clear that Keezhadi, like other ancient sites of Tamilakam, had links with northern India since it’s earliest period and they were not part of any isolated separate pre-Vedic Tamil civilization.

True, the findings from Keezhadi would push back the date of urbanism in Tamilakam back to 6th century BCE. But to say that it was contemporary to Gangetic urbanization is not entirely correct.

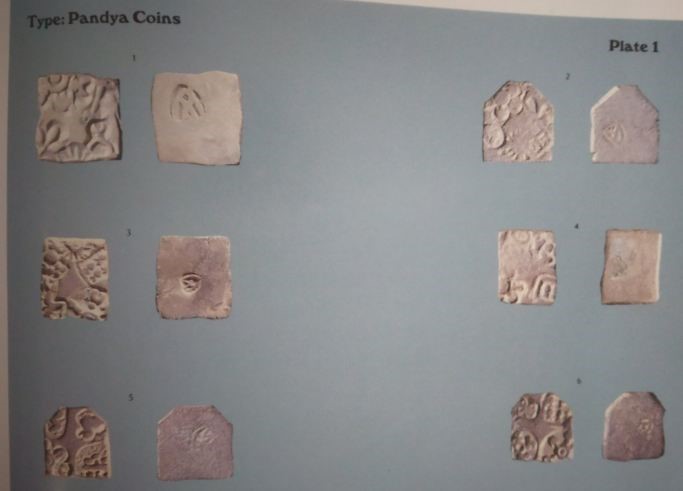

By 600 BCE many urban Vedic Janapadas with grand cities were already established in Gangetic region as well as in Deccan. These Janapadas also minted their own punch-marked coins. In fact we also find early Tamil Pandyan kingdom minting the same type of coins with their royal fish symbol on reverse [8]

This only means that proper kingdoms & currency system was established in southern India during the time of Vedic Janapadas with the influences from north.

Thus, the early Tamil kingdoms were part of one unified civilization which included northern Janapadas as well, and the Tamil kingdoms & ancient sites like Keezhadi were not part of any separate pre-Vedic civilization like Dravidianists wants them to be.

Also it is plain wrong to state that urbanism in Tamilakam occurred same time as in Gangetic region. Urbanism in Gangetic region dates back to ‘proto-urban’ Pianted Grey Ware or PGW cultural phase, beyond 1000 BCE and well beyond 6th century BCE dates from Keezhadi. Some PGW sites also overlaps with late Indus culture. As noted historian Upinder Singh has written in her book [9]:

“The dates of the PGW culture range from c.1100 to c 500/400 BCE, and the sites in the north-west are probably earlier than those in the Ganga valley Given as wide geographical distribution and chronological range, it is not surprising that there are regional variations both in the pottery as well as in associated remains. In the archaeological sequence of the Ganga valley, the PGW phase is followed by the Northern Black Polished Ware (NBPW) phase, the beginning or which goes back to c, 700 BCE at Sringaverapura.The evidence from various PGW sites suggests a proto-urban phase. “

Important evidence of the PGW material culture is available from excavated slits such as Hastinapur, Alamgirpur, Ahichchatra, Allahpur, Mathura, Kampil, Noh, Jodhpura, Bhagwanpura, Jakhera, Kaushambi, and Shravasti. PGW occurs in four kinds of stratigraphic contexts. At some sites (e.g. Rupar and Sangho! in Punjab, Daulatpur in Haryana, and Alamgirpur and Hulas in western UP), it is preceded by a late Harappan level, with an intervening break in occupation. At other sites (e.g. Dadhert, Katpalon. and Nagar in the Punjab and Bhagwanpura in Haryana), there is an overlap between the PGW and late Harappan phase.”

In fact Keezhadi is just one site showing early signs of urbanism in Tamilakam, while most other ancient sites in ancient Tamilakam were overwhelmingly in non-urban megalithic phase during the iron age until urbanism came in during later centuries. In Gangetic zone we have signs of urbanism or proto-urbanism from multiple sites which later evolved into grand cities as stated above.

The urbanization of Gangetic region was a gradual process, tracing the roots to iron age PGW culture which itself overlapped with late Indus culture. It is certainly older than any urban site from Tamilakam discovered so far. So it is not correct to claim that process of urbanism in early Tamilakam was contemporary with that of north.

Vedic civilization unified north & south India

Finally, I quote the words of one of the greatest south Indian historian Shri KAN Sastri. According to him the Vedic ‘Aryanization’ process of southern India started with early phase from around 1000 BCE onwards [10]

“The Aryanization of the South was no doubt a slow process spread over several centuries. Beginning probably about 1000 BC, it had reached its completion before the time of Katyayana, the grammarian of the fourth century BC, who mentions the names of the Tamil countries of the extreme South. “

During 1000 BCE most parts of Tamilakam was in megalithic phase. While we have no clue about the language or religion of these iron age megalithic people, from their association with punch-marked coins & prevalence of megalithic culture even into later centuries (by then Tamil kingdoms already followed Vedic culture), we can probably infer that it could indeed have been associated with expansion of Vedic culture from north. The proper urban civilization in Tamilakam gradually evolved from megalithic phase by later centuries BCE & it didn’t form any separate civilization from north. Once the expansion of Vedic culture into south happened, both north & south India had one unified Vedic civilization since earliest attested historic era.

All likely the Vedic cultural expansions from out of Aryavarta (regions of northern India which was the land of Vedic Aryans) during late Vedic era onwards also included movement of people as well. Hence, vast majority of the modern speakers of Dravidian linguistic group, including the Tamils, also share the heritage & ancestry of ancient Vedic civilization.

References

[1] Recent Discoveries of Jaina Cave Inscriptions in Tamilnadu by Iravatham Mahadevan

[2] Early Writing System: A Journey from Graffiti to Brahmi by K. Rajan p.421.

[3] Ibid, p.422.

[4] Palani excavation triggers fresh debate – The Hinduhttps://www.thehindu.com/news/national/tamil-nadu/palani-excavation-triggers-fresh-debate/article2408091.ece

[5] Keeladi An Urban Settlement Of Sangam Age by TN Archeological Society p.14

[6] Vaisali excavations, 1958-1962, by B. P. Sinha, and Sita Ram Roy Plate XXX, seal 24.

[7] Iravatham Mahadevanas cited in The Lost River: On The Trail of the Sarasvati, by Michel Danino p.218

[8] Sangam Age Tamil Coins by R.Krishnamurthy Plate 1, 1-6.

[9] A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century by Upinder Singh p.246. [10] A History of South India: From Prehistoric Times to the Fall of Vijayanagar by KAN Sastri p.17.

Featured Image: The Hindu http://indiafacts.org/keezhadi-does-it-reflect-a-non-vedic-dravidian-civilization-in-ancient-tamil-nadu/

The location of Keeladi on the banks of Vaigai river is significant. The origins of this river close to Kerala (and Westcoast of India) indicates the possible sea-route which may have been taken by the artificers of Sarasvati River Basin who moved away from Tuvarai approximately 42 generations prior to 600 BCE as recorded in an ancient Sangam text.

“Legend has it that the Pandava princes ...left on a pilgrimage of India, and in Kerala, each of these brothers installed Vishnu on the banks of the Pampa and nearby places and offered worship. (Chengannur - Yuddhishtra, Tiruppuliyur - Bheema, Aranmula - Arjuna, Tiruvamundur - Nakula and Tirukkadittaanam - Sahadeva). It is said that Arjuna built this temple at Nilackal near Sabarimalai. and the image was brought here in a raft made of six pieces of bamboo to this site, and hence the name Aranmula (six pieces of bamboo). Legend has it that Arjuna built this temple, to expiate for the sin of having killed Karna on the battlefield, against the dharma of killing an unarmed enemy. It is also believed that Vishnu (here) revealed the knowledge of creation to Brahma, from whom the Madhukaitapa demons stole the Vedas.”

The location of Keeladi on the banks of Vaigai river is significant. The origins of this river close to Kerala (and Westcoast of India) indicates the possible sea-route which may have been taken by the artificers of Sarasvati River Basin who moved away from Tuvarai approximately 42 generations prior to 600 BCE as recorded in an ancient Sangam text.

Annex. Reference to Dwaraka as Tuvarai in an ancient Sangam text

This Vedic expression ayasipur is consistent with the description of Dwaraka in Purananuru as a fortification with walls made of copper (metal).

இவர் யார் என்குவை ஆயின் இவரே

ஊருடன் இரவலர்க்கு அருளித் தேருடன்

Ayasipur is a Vedic expression. अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c अयस्मय (अयोमय) a. (-यी f.) Ved. Made of iron or of any metal. -यी N. of one of the three habita- tions of Asuras. pur पुर् f. (Nom. sing. पूः; instr. du. पूर्भ्याम्) 1 A town, fortified town; thus ayasipur refers to a fortification made of stone or metal. (पूरण्यभिव्यक्तमुखप्रसादा R.16.23)

துவரை² tuvarai, n. See துவாரகை. உவரா வீகைத் துவரை யாண்டு (புறநா. 201). துவாரகை tuvārakai , n. < dvārakā. The capital of Kṛṣṇa on the western side of Gujarat, supposed to have been submerged by the sea, one of catta-puri, q. v.; சத்தபுரியுளொன் றாயதும் கடலாற்கொள்ளப்பட்ட தென்று கருதப்படுவதும் கண்ணபிரான் அரசுபுரிந்ததுமான நகரம்.

This Vedic expression ayasipur is consistent with the description of Dwaraka in Purananuru as a fortification with walls made of copper (metal).

ஊருடன் இரவலர்க்கு அருளித் தேருடன்

முல்லைக்கு ஈத்த செல்லா நல்லிசை

படுமணி யானைப் பறம்பின் கோமான்

நெடுமாப் பாரி மகளிர் யானே

தந்தை தோழன் இவர் என் மகளிர்

அந்தணன் புலவன் கொண்டு வந்தனனே

நீயே வட பால் முனிவன் தடவினுள் தோன்றிச்

செம்பு புனைந்து இயற்றிய சேண் நெடும் புரிசை

உவரா ஈகைத் துவரை யாண்டு

நாற்பத்து ஒன்பது வழி முறை வந்த

வேளிருள் வேள விறல் போர் அண்ணல்

தார் அணி யானைச் சேட்டு இருங்கோவே

ஆண் கடன் உடைமையின் பாண் கடன் ஆற்றிய

ஒலியற் கண்ணிப் புலிகடிமாஅல்

யான் தர இவரைக் கொண்மதி வான் கவித்து

இரும் கடல் உடுத்த இவ் வையகத்து அரும் திறல்

பொன்படு மால் வரைக் கிழவ வென் வேல்

உடலுநர் உட்கும் தானைக்

கெடல்அரும் குரைய நாடு கிழவோயே !

If you ask who they are, they are his daughters,

he who granted cities to those who came in need

and earned great fame for gifting

a chariot to the jasmine vine to climb,

he who owned elephants with jingling bells,

the lord of Parampu, the great king Pāri.

They are my daughters now.

As for me, I am their father’s friend, a Brahmin,

a poet who has brought them here.

You are the best Vēlir of the Vēlir clan,

with a heritage of forty nine generations of Vēlirs

who gave without limits,

who ruled Thuvarai with its long walls that

seemed to be made of copper, the city that

appeared in the sacrificial pit of a northern sage (Yaja).

King who is victorious in battles!

Great king with garlanded elephants!

Pulikatimāl with a bright garland

who knows what a man’s responsibility is,

and what you can do for bards!

I am offering them. Please accept them.

Lord of the sky high mountain that yields gold!

You whose strength cannot be equaled on the earth

that is covered by an arched sky and surrounded

by the ocean, you whose army puts fear into

enemies with victorious spears!

O ruler of a land that can never be ruined!

படுமணி யானைப் பறம்பின் கோமான்

நெடுமாப் பாரி மகளிர் யானே

தந்தை தோழன் இவர் என் மகளிர்

அந்தணன் புலவன் கொண்டு வந்தனனே

நீயே வட பால் முனிவன் தடவினுள் தோன்றிச்

செம்பு புனைந்து இயற்றிய சேண் நெடும் புரிசை

உவரா ஈகைத் துவரை யாண்டு

நாற்பத்து ஒன்பது வழி முறை வந்த

வேளிருள் வேள விறல் போர் அண்ணல்

தார் அணி யானைச் சேட்டு இருங்கோவே

ஆண் கடன் உடைமையின் பாண் கடன் ஆற்றிய

ஒலியற் கண்ணிப் புலிகடிமாஅல்

யான் தர இவரைக் கொண்மதி வான் கவித்து

இரும் கடல் உடுத்த இவ் வையகத்து அரும் திறல்

பொன்படு மால் வரைக் கிழவ வென் வேல்

உடலுநர் உட்கும் தானைக்

கெடல்அரும் குரைய நாடு கிழவோயே !

If you ask who they are, they are his daughters,

he who granted cities to those who came in need

and earned great fame for gifting

a chariot to the jasmine vine to climb,

he who owned elephants with jingling bells,

the lord of Parampu, the great king Pāri.

They are my daughters now.

As for me, I am their father’s friend, a Brahmin,

a poet who has brought them here.

You are the best Vēlir of the Vēlir clan,

with a heritage of forty nine generations of Vēlirs

who gave without limits,

who ruled Thuvarai with its long walls that

seemed to be made of copper, the city that

appeared in the sacrificial pit of a northern sage (Yaja).

King who is victorious in battles!

Great king with garlanded elephants!

Pulikatimāl with a bright garland

who knows what a man’s responsibility is,

and what you can do for bards!

I am offering them. Please accept them.

Lord of the sky high mountain that yields gold!

You whose strength cannot be equaled on the earth

that is covered by an arched sky and surrounded

by the ocean, you whose army puts fear into

enemies with victorious spears!

O ruler of a land that can never be ruined!

Irunkovel is supposed to be 49th generation of a king from (Thuvarai) Dwaraka. It can mean two things. Assuming about 30 years per generation, 1500 years earlier Dwaraka which had walls made of copper. Dating the early phase of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization to ca. 3500 BCE, and the submergence of Dwaraka to ca. 1900 BCE (a date indicative of the drying up of Vedic River Sarasvati due to migrations of Sutlej and Yamuna rivers which were tributaries bringing in glacier waters), which necessitated the movements of Sarasvati's children down the coastline to Kerala, this text places Sangam literature text of Purananuru to ca. 400 BCE.

(Source: http://historum.com/asian-history/76340-satyaputras-earliest-indo-aryanizers-south-india-3.html

Migration from Tuvarai (Dwaraka) is attested in a 12th century inscription (Pudukottai State inscriptions, No.

120) cited by Avvai S. Turaicaami in Puranaanuru, II (SISSW Publishing Soc., Madras, 1951).

•துவரை மாநகர் நின்ருபொந்த தொன்மை பார்த்துக்கிள்ளிவேந்தன் நிகரில் தென் கவரி நாடு தன்னில் நிகழ்வித்த நிதிவாளர்

Archaeo-metallurgical and seafaring traditions of the Civilization are attested in regions of southern Bharat

The archaeo-metallurgical and seafaring traditions of the Civilization are attested in Southern Bharat as exemplified by the following:

https://www.scribd.com/doc/289709143/Metal-casting-Traditions-South-Asia-PT-Craddock-2014

http://www.insa.nic.in/writereaddata/UpLoadedFiles/IJHS/Vol50_2015_1_Art05.pdf Indian Journal of Hisory of Science, 50.1 (2015), 55-82 PT Craddock, Metal casting traditions of South Asia: Continuity and Innovation

The archaeo-metallurgical and seafaring traditions of the Civilization are attested in Southern Bharat as exemplified by the following:

https://www.scribd.com/doc/289709143/Metal-casting-Traditions-South-Asia-PT-Craddock-2014

http://www.insa.nic.in/writereaddata/UpLoadedFiles/IJHS/Vol50_2015_1_Art05.pdf Indian Journal of Hisory of Science, 50.1 (2015), 55-82 PT Craddock, Metal casting traditions of South Asia: Continuity and Innovation

“Legend has it that the Pandava princes ...left on a pilgrimage of India, and in Kerala, each of these brothers installed Vishnu on the banks of the Pampa and nearby places and offered worship. (Chengannur - Yuddhishtra, Tiruppuliyur - Bheema, Aranmula - Arjuna, Tiruvamundur - Nakula and Tirukkadittaanam - Sahadeva). It is said that Arjuna built this temple at Nilackal near Sabarimalai. and the image was brought here in a raft made of six pieces of bamboo to this site, and hence the name Aranmula (six pieces of bamboo). Legend has it that Arjuna built this temple, to expiate for the sin of having killed Karna on the battlefield, against the dharma of killing an unarmed enemy. It is also believed that Vishnu (here) revealed the knowledge of creation to Brahma, from whom the Madhukaitapa demons stole the Vedas.”