-- -- मक्षिका mākṣikā 'pyrites' metaphor in R̥gveda, 3-D hieroglyphs on Nahal Mishmar arsenical bronze hoards of

Indus Script Cipher has a unique princple to form hypertexts. Animal parts are combined to signify wealth classification categories.

![]() Combined animal heads on a bovine body. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Combined animal heads on a bovine body. Mohenjo-daro seal.

![]()

ډنګر ḏḏangar, s.m. (5th) A bullock or buffalo. Pl. ډنګر ḏḏangœr. ډنګره ḏḏangaraʿh, s.f. (3rd). Pl. يْ ey. 2. adj. Thin, weak, lean, meagre, emaciated, scraggy, attenuated. rebus: dangar 'blacksmith'.![]()

![Istanbul Arch Museum 01391.jpg]() Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate.

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate.

![]() Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

mēd 'body' (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ 'iron' (Ho.) Ta. mēṉi body, shape, colour, beauty; mēl body. Ma. mēni body, shape, beauty, excellence; mēl body. Koḍ. me·lï body. Te. mēnu id.; mēni brilliancy, lustre; belonging to the body, bodily, personal. Kol. me·n (pl.me·nḍl) body. Nk. mēn (pl. mēnuḷ) id. Nk. (Ch.) mēn id. Pa. mēn (pl. mēnul) id. Ga. (S.) mēnu (pl. mēngil), (P.) mēn id. Go. (Tr.) mēndur (obl. mēnduḍ-), (A. Y. W. M.) mēndul, (L.) meṇḍū˘l, (SR.) meṇḍol id. (Voc.2963). Konḍa mēndol human body. Kur. mē̃d, mēd body, womb, back. Malt. méth body (DEDR 5099)

![Baked clay plaque showing a bull-man holding a post.]()

On this terracotta plaque, the mace is a phonetic determinant of the bovine (bull) ligatured to the body of the person holding the mace. The person signified is: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ "... head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull...Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. British Museum. WCO2652. Bull-manTerracotta plaque. Bull-man holding a post. Mesopotamia, ca. 2000-1600 BCE."R̥gveda 1.119.9, 10 speaks of the 'mystic science' of using mākṣikā, bees' and Dadhyãc bones. I suggest that this is a pun on the word: Hieroglyph: माक्षिक [p= 805,2] mfn. (fr. मक्षिका mākṣikā) coming from or belonging to a bee Ma1rkP. Rebus: माक्षिक n. a kind of honey-like mineral substance or pyrites MBh.

Nahal Mishmar hieroglyphs on 'crowns' signify smithy/temple in fortified town producing hard metal alloys http://tinyurl.com/njzvx7f

![]()

dukraदुक्र । वाद्यविशेषः m. a certain musical instrument, described as consisting of linked rings fixed to a staff. Cf. dahara.(Kashmiri)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() The most common objects were 118 of these "standards" or "scepters." What they really were is anybody's guess. Some had traces of reeds or wood in the holes, suggesting that they were attached to poles.

The most common objects were 118 of these "standards" or "scepters." What they really were is anybody's guess. Some had traces of reeds or wood in the holes, suggesting that they were attached to poles.![]()

Clara Amit, IAA

![]() There are ten of these cylindrical objects in the hoard. They are conventionally known as "crowns," but more archaeologists think they were stands for vessels with pointed bottoms.

There are ten of these cylindrical objects in the hoard. They are conventionally known as "crowns," but more archaeologists think they were stands for vessels with pointed bottoms. ![]() What is one to make of this hippopotamus ivory object, essentially a slice from a hippo's tooth drilled with as many holes as would fit?

What is one to make of this hippopotamus ivory object, essentially a slice from a hippo's tooth drilled with as many holes as would fit?![]() This object seems to be proof that the pushmi-pullyu really existed in the Chalcolithic era.

This object seems to be proof that the pushmi-pullyu really existed in the Chalcolithic era. ![]() The closest major site of this period is a shrine at the oasis of Ein Gedi, 7 miles (12 km) away, and the objects may have been hiddenwhen the shrine was under some kind of threat. The cave is in a steep ravine, accessible only with ropes and ladders, so it would have made a good hiding place. So good that this amazing collection of objects remained hidden for 5500 years.

The closest major site of this period is a shrine at the oasis of Ein Gedi, 7 miles (12 km) away, and the objects may have been hiddenwhen the shrine was under some kind of threat. The cave is in a steep ravine, accessible only with ropes and ladders, so it would have made a good hiding place. So good that this amazing collection of objects remained hidden for 5500 years.

![]() Nahal Mishmar treasure was discovered by chance , tucked in a secluded niche corner of a cave inhabited calcolítica located on the north side of the Nahal Mishmar throat , in the wilderness of Judah. Was wrapped in a mat and contained 442 different objects, 429 of copper, 6 oligisto , stone 1 , 5 , 1 hippo ivory elephant ivory . A collection of strange and unique findings and seems to have been hastily collected and hidden in the final days of occupation of the cave. In view of this, it has been suggested , plausibly , that the whole is the sacred shrine Enguedi treasure (which is apparently devoid of found objects), located just eight miles .

Nahal Mishmar treasure was discovered by chance , tucked in a secluded niche corner of a cave inhabited calcolítica located on the north side of the Nahal Mishmar throat , in the wilderness of Judah. Was wrapped in a mat and contained 442 different objects, 429 of copper, 6 oligisto , stone 1 , 5 , 1 hippo ivory elephant ivory . A collection of strange and unique findings and seems to have been hastily collected and hidden in the final days of occupation of the cave. In view of this, it has been suggested , plausibly , that the whole is the sacred shrine Enguedi treasure (which is apparently devoid of found objects), located just eight miles .

Most treasure objects are made of copper containing a variable percentage of arsenic, but always high ( 4 % -12 %). Most surprising is that this special copper was used only on objects made with the lost wax technique rather simple chisels and hammers, lso found that 16. This distinction is also present in other sites . There is therefore a clear difference in the use of the two types of copper . For votes almost pure copper was used , although softer , for special objects no longer , harder and easier to empty arsenical copper was used.

The whole treasure is a magnificent collection of art objects. The objects are made of valuable materials , maintain high technological quality and have a superior finish . Their shapes witness to a developed artistic sense. It can be assumed , in view of the decorative motifs , which is a rich repository of religious symbolism.

![]()

a) Crowns

The cache ten cylindrical objects that seem crowns, with a diameter of 15'6 to 19 inches , and a height of 7 inches to 11'7 found. Two are provided with small feet. The body sometimes takes an incised decoration varied design : parallel lines , triangles and bands as Fishbone .

![]()

b ) The scepters

This is a group of 118 different objects , with lengths ranging from 7 to 40 inches. Some of the scepters retained traces of wooden handles or cane , and some was a black sticky substance. This has led archaeologists to conclude that the objects were taken on long poles , perhaps in sacred processions. A linen thread found in one of the Sceptres may indicate that they are bound lightweight materials such as tapes . All scepters are similar in shape but differ greatly in their size and detail of its decoration. The most splendid has five heads of animals (four of ibex and an animal with twisty horns) . It should be noted that similar scepters found at other sites .

c ) The poles

This term describes a group of stylized , long and solid scepters . Three of them appear refined versions of scepters with curved ends. The fourth is like the stem of a plant and the fifth has a flat head hooked .

![]()

d ) The sets standards

The three splendid banners of this group were definitely mounted on poles . The first is a hollow pear-shaped object with two twins ibex represented with one body , four legs and two heads. Each ibex is facing one of the biggest arms, one ax-shaped and the other knife , leaving the piriform body . The second banner has a short hollow columnilla a rectangular panel that extends from the center , made in the form of a vulture with outstretched wings. The third is more modest ; swelling part of his plans four protruding out in four different directions.

e) The horn-shaped objects

Three objects in the form of curved horn emphasize the importance of the horns in the Chalcolithic ritual. Two of the horns lead schematic figures of birds.

f ) Containers

A jug turtleneck beautiful proportions , a cup or deep bowl and three cups shaped basket with high vertical handle are the only containers found in the treasure.

g) maceheads

The largest group of objects with a total of 261 , including several thickened (rounded , pear-shaped , elongated or discoidal ) forms that are usually called " mace heads " objects. All have a hole in the center to insert a handle . Some specimens preserved remains of wooden handles . The surface is well polished and all undecorated .

Although the mace-head was a common weapon in Mesopotamia and Egypt , these objects may not to be considered as weapons. Their presence in the treasure seems, rather, a ceremonial use. If similarity with convex parts of the banners and scepters supports this view .

Six mace heads were made of hematite , Natural iron oxide . Were emptied but not drilled , as yet no technology known iron work . Another club head is made of hard limestone .

![]()

h ) The objects made of hippo tusk

Five mysterious objects were hidden along with objects of copper hippopotamus ivory , sectioned along the tusk shaped scythe. Are perforated by three rows of round holes , and in the middle of each there is a hole with a protruding edge .

i ) Cash ivory

Final object of one type is an ivory box 38 inches long made with a piece of elephant tusk well polished .

Translation from Spanish.http://curiosomundoazul.blogspot.in/2011/07/el-tesoro-de-nahal-mishmar.html

http://www.eretz.com/NEW/articlepage.php?num=27

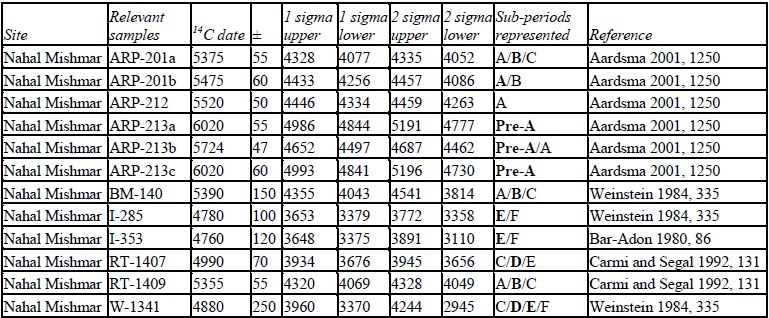

Addendum on carbon-14 dating of Nahal Mishmar finds to ca. +4400 BCE:

![]()

Source: https://www.academia.edu/3427110/_2010_Developmental_Trends_in_Chalcolithic_Copper_Metallurgy_A_Radiometric_Perspective_Shugar_and_Gohm_

https://www.academia.edu/attachments/31198898/download_file 10. Developmental Trends in Chalcolithic Copper Metallurgy: A Radiometric Perspective -- Aaron N. Shugar and Christopher J. Gohm

http://www.scribd.com/doc/198085507/Shugar-and-Gohm-Chapter-10-2010-in-Print

Radiometric evidence from Nahal Mishmar (Cave 1) is complicated, as dates both old and new offer contradictory information (Table 10.6). For the most part, these contradictions are related to the dating of the reed mat in which the hoard was wrapped (ARP-series, BM-140, I-285 and W-1341, the last three of which are included here for comparative purposes only, as they were measured very early in the history of the technique and may not be entirely reliable). These nine dates suggest that the mat was an ancient heirloom repaired occasionally over time, as they ‘spread out in at least three groups over a millennium or more … and that such repairs may be responsible for the divergent 14C ages from different portions of the mat’ (Aardsma 2001, 1251–3).

Owing to the incredible variations between these determinations the date of the reed mat contributes little to the present discussion, and instead other samples from Cave 1 should be considered. A sample from another reed mat (RT-1407) yielded a date between the 40th and 37th centuries cal BCE, while a sample from a possible loom fragment (RT-1409) appears to date between the 44th and 41st centuries cal BCE (Carmi and Segal 1992, 131). A third date originating from the haft of one of the copper standards (I-353), between the 40th and 34th centuries cal BCE, also deserves mention despite its age (measured inthe 1960s) (Weinstein 1984, 335). These determinations are not statistically the same, and the sub-periods best represented by these three dates are D followed by E, suggesting significant activity at Nahal Mishmar from the 39th to the 36th centuries cal BC (there is also a concentration of radiocarbon years in sub-period B, but these are strongly outweighed by those of D and E). Based on these determinations and the stratigraphic context of the hoard itself, it would be very difficult to push the date of the hoard’s deposition earlier than the first quarter of the 4th millennium cal BCE (a conclusion also reached by Moorey (1988, 173)).

http://www.scribd.com/doc/56148616/Besenval-Roland-2005 Shahi-Tump leopard weight.Leopard weight. Shahi-Tump (Balochistan).

Meluhha hieroglyphs; rebus readings: Leopard, kharaḍā; rebus:karaḍā 'hard alloy from iron, silver etc.'; ibex or markhor 'meḍh' rebus: ‘iron stone ore, metal merchant.’

खरडा [ kharaḍā ] A leopard. खरड्या [ kharaḍyā ] m or खरड्यावाघ m A leopard (Marathi). Kol. keḍiak tiger. Nk. khaṛeyak panther. Go. (A.) khaṛyal tiger; (Haig) kariyāl panther Kui kṛāḍi, krānḍi tiger, leopard, hyena. Kuwi (F.) kṛani tiger; (S.) klā'ni tiger, leopard; (Su. P. Isr.) kṛaˀni (pl. -ŋa) tiger. / Cf. Pkt. (DNM) karaḍa- id. (CDIAL 1132+). Rebus 1: kharādī ‘ turner, a person who fashions or shapes objects on a lathe’ (Gujarati) Rebus 2: करड्याची अवटी [ karaḍyācī avaṭī ] f An implement of the goldsmith. Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

miṇḍāl ‘markhor’ (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120); rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda)Lothal seal L048 Ibex. Another hieroglyph shown on the seal: ayo 'fish' rebus: ayo 'metal alloy' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Sanskrit)![]()

Fish sign incised on copper anthropomorph, Sheorajpur, upper Ganges valley, ca. 2nd millennium BCE, 4 kg; 47.7 X 39 X 2.1 cm. State Museum, Lucknow (O.37) Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo, ayas ‘metal. Thus, together read rebus: ayo meḍh ‘iron stone re, metal merchant.’

Nahal Mishmar evidence of cire perdue metal casting, R̥gveda evidence of cupellation of mākṣika 'pyrites' to gain amśu, ancu 'iron' in Ancient Pyrotechnology

https://tinyurl.com/ybd3lyux

https://www.academia.edu/40265596/Nahal_Mishmar_evidence_of_hieroglyphs_and_link_with_writing_system_of_Indus_Script_dated_to_ca_3300_BCE

Nahal Mishmar evidence of hieroglyphs and link with writing system of Indus Script, dated to ca 3300 BCE

https://www.academia.edu/34039274/The_Nahal_Mishmar_Hoard_and_Chalcolithic_Metallurgy_in_Israel

NahalMishmar evidences of cire perdue metal casting artifacts are dated to 6th millennium BCE. R̥gveda textual evidences relate to metalworking processes of a period earlier than 7th millennium BCE. This note claims that aspects of metalwork related to Ancient Pyrotechnology are: 1 cire perdue technique of metal casting and 2. use of cupellation to obtain purified metals from working with pyrites and mineral ores in furnaces, kilns or fire-altars.

il![]()

-- Nahal Mishmar 6th millennium BCE 3-D visual codes of arsenical bronze metalwork catalogues

Thanks to Nissim Amzallag for the insights on 3-D visual codes of a proto-writing system on prestige artifacts from

Nahal Mishmar. His insights were reported on Haaretz on August 5, 2019.

3-D hieroglyphs are characteristic of Indus Script logograms as may be seen from the following examples.

I suggest the cave in which Paṇi had hidden the treasure is Nahal Mishmar cave.

This links with the Saramā, Rasā R̥gveda metaphors, narratives of .

-- Defining Airyana Vaeja, metahors of R̥gveda Saramā, rásā रसा 'river'मा 'mother, water, divinity of wealth signified on Indus Script Corpora

-- An alliteration of the expression रसा 'river'मा 'mother' is Saramā and hence, the explanation of Saramā as 'mother of beasts'..

-- Airyana Vaeja, Saramā 'mother of beasts' alliteration of rásā रसा mother divinity river of R̥gveda compares with Styx of Greek tradition

-- Insights provided by K.E.Eduljee are pointers to the delineation of the ancient land with which R̥gveda people had trade transactions, a region which is Akkad

रसा rásā in R̥gveda is a reference to moisture, humidity and is name of a river. The locatin of this river is central to resolve the Aryan debate.

Indus Script Cipher has a unique princple to form hypertexts. Animal parts are combined to signify wealth classification categories.

Combined animal heads on a bovine body. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Combined animal heads on a bovine body. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Combined animal figurine: elephant, buffalo, feline in sculptured form. Why are these three distinct animals combined? Because, they signify distinct wealth categories of metalwork.

Rebus renderings signify solder, pewter, tin, tinsel, tin foil: Hieroglyph: Ku. N. rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ(CDIAL 10559) Rebus: 10562 raṅga3 n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. [Cf. nāga -- 2 , vaṅga -- 1 ] Pk. raṁga -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ (← H.); Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼ, gng. rã̄k; N. rāṅ, rāṅo ʻ tin, solder ʼ, A. B. rāṅ; Or. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; Si. ran̆ga ʻ tin ʼ.*raṅgapattra -- .10567 *raṅgapattra ʻ tinfoil ʼ. [raṅga -- 3 , páttra -- ] B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.(CDIAL 10562, 10567)

ranku 'antelope' rebus:rã̄k,ranku 'tin'

melh,mr̤eka 'goat or antelope' rebus: milakkhu '

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate.

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate.khoṇḍa singi 'horned young bull' rebus; kunda singi 'fine gold, ornament gold'.

शृङ्गिन् śṛṅgin शृङ्गिन् a. (-णी f.) [शृङ्गमस्त्यस्य इनि] 1 Horned. -2 Crested, peaked. -m. 1 A mountain. -2 An elephant. -3 A ram. -4 A tree. -5 N. of Śiva. -6 N. of one of Śiva's attendants; शृङ्गी भृङ्गी रिटिस्तुण्डी Ak. -7 A bull; शङ्ग्यग्निदंष्ट्र्यसिजलद्विजकण्टकेभ्यः Bhāg.1.8.25. shrang श्रंग् । शृङ्गम्, प्रधानभूतः m. a horn; the top, peak, summit of a mountain (Kashmiri)

Meluhha Indus Script cipher or mlecchita vikalpa, śṛṅgin 'horned' rebus: śr̥ngī 'gold used for onaments' https://tinyurl.com/yyd5kqk4

![]() Wicker-basket-shaped crown with Indus Script hieroglyphs of

Wicker-basket-shaped crown with Indus Script hieroglyphs of

Hieroglyph, 'horned animal': siṅgin.'horned', having a horn Vin ii. 300; J iv. 173 (=cow); clever, sharp -- witted, false Th 1, 959; A ii. 26; It 112; cp. J.P.T.S. 1885, 53. (Pali) OMarw. (Vīsaḷa) sīṁgī f.adj. ʻhorned (of cow)ʼ. (CDIAL 12595).

Rebus: singī & singi (f.) [cp. Sk. śṛngī] gold Vini. 38; S ii. 234; J i. 84 (Pali) śr̥ngī-कनकम् gold used for ornaments. शृङ्गिः śṛṅgiḥ शृङ्गिः Gold for ornaments. शृङ्गी śṛṅgī Gold used for ornaments.

The one-horned bovine is thus read as: kār kunda siṅgin 'gold for use in ornaments' (by) 'blacksmith, turner, goldsmith.' Singin 'clever, sharp -- witted, false Th 1, 959; Aii. 26; It 112; cp. J.P.T.S. 1885, 53.(Pali) is a synonym of کنده kār-kunda 'manager, director, adroit, clever, experienced' (Pashto) kunda1 m. ʻ a turner's lathe ʼ lex. [Cf. *cunda -- 1 ]N. kũdnu ʻ to shape smoothly, smoothe, carve, hew ʼ, kũduwā ʻ smoothly shaped ʼ; A. kund ʻ lathe ʼ, kundiba ʻ to turn and smooth in a lathe ʼ, kundowā ʻ smoothed and rounded ʼ; B. kũd ʻ lathe ʼ, kũdā, kõdā ʻ to turn in a lathe ʼ; Or. kū˘nda ʻ lathe ʼ, kũdibā, kū̃d˚ ʻ to turn ʼ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ʻ lathe ʼ); Bi. kund ʻ brassfounder's lathe ʼ; H. kunnā ʻ to shape on a lathe ʼ, kuniyā m. ʻ turner ʼ, kunwā m.(CDIAL 3295) kunda 'a treasure of Kubera'; kunda 'gold' kundaṇa 'fine gold'. Thus, of کنده kār-kunda singin signifies 'fine gold, gold for ornaments'. kõdār 'turner' (Bengali) kō̃da 'kiln, furnace' (Kashmiri)

This is an addendum to:

Meluhha Indus Script cipher or mlecchita vikalpa, śṛṅgin 'horned' rebus: śr̥ngī 'gold used for onaments' https://tinyurl.com/yyd5kqk4

![Image result for unicorn terracotta figure]() Unicorn read rebus in Meluhha as खोंड khōṇḍa singin 'young bull, horned'.

Unicorn read rebus in Meluhha as खोंड khōṇḍa singin 'young bull, horned'.

Assur are iron workers. The links to Ashur of Ancient Near East are attested in Indus Script hieroglyphs and Sanauli artifacts. This monograph suggests that Assur, Ashur are shown as golden anthropomorph of Sanauli and on eight bull-man anthropomorphs on coffins found at Sanauli. The link between Assur and Ashur is reinforced by the wicker-basket hat worn by Gudea of Ancient Near East, the same style of hat worn by the Golden anthropomorph dancer of Sanauli. The recurrent display of ficus infectoria, ficus religiosa on Indus Script inscriptions reinforces the rebus rendering of the one-horn or horned as singin rebus singin 'village headman, gold for ornaments'.

The 'crowns' of Nahal Mishmar are shaped like the wicker-basket. A crown of this shape is called káraṇḍa mukuṭa. káraṇḍa1 m.n. ʻ basket ʼ BhP., ˚ḍaka -- m., ˚ḍī -- f. lex.

Pa. karaṇḍa -- m.n., ˚aka -- m. ʻ wickerwork box ʼ, Pk. karaṁḍa -- , ˚aya -- m. ʻ basket ʼ, ˚ḍī -- , ˚ḍiyā -- f. ʻ small do. ʼ; K. kranḍa m. ʻ large covered trunk ʼ, kronḍu m. ʻ basket of withies for grain ʼ, krünḍü f. ʻ large basket of withies ʼ; Ku. kaṇḍo ʻ basket ʼ; N. kaṇḍi ʻ basket -- like conveyance ʼ; A. karṇi ʻ open clothes basket ʼ; H. kaṇḍī f. ʻ long deep basket ʼ; G. karãḍɔ m. ʻ wicker or metal box ʼ, kãḍiyɔ m. ʻ cane or bamboo box ʼ; M. karãḍ m. ʻ bamboo basket ʼ, ˚ḍā m. ʻ covered bamboo basket, metal box ʼ, ˚ḍī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; Si. karan̆ḍuva ʻ small box or casket ʼ. -- Deriv. G. kãḍī m. ʻ snake -- charmer who carries his snakes in a wicker basket ʼ.(CDIAL 2792) The shape of wicker-basket is a semantic determinative of the aquatic bird kāraṇḍava m. ʻ a kind of duck ʼ MBh. [Cf. kāraṇḍa- m. ʻ id. ʼ R., karēṭu -- m. ʻ Numidian crane ʼ lex.: see karaṭa -- 1 ] Pa. kāraṇḍava -- m. ʻ a kind of duck ʼ; Pk. kāraṁḍa -- , ˚ḍaga -- , ˚ḍava -- m. ʻ a partic. kind of bird ʼ; S. kānero m. ʻ a partic. kind of water bird ʼ < *kāreno.(CDIAL 3059)

Such an aquatic bird or duck is also shown on a Nahal Mishmar crown together with the hieroglyphs of a tower and foundation peg.

The rebus reading in Meluhha is: káraṇḍa 'duck''wicker-basket shape' Rebus 1: karaṇḍa 'hard alloy'; Rebus 2: karandi 'fire god' (Remo)

Wicker-basket-shaped crown with Indus Script hieroglyphs of

Wicker-basket-shaped crown with Indus Script hieroglyphs of tower, foundation peg, a pair of ducks read rebus as related to a catalogue of metalwork, dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'..

After Fig 6.2 Unicorn seal, detail of head, H95-2491, scanning electron miscroscope photo ( Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Iconography of the Indus Unicorn: Origins and Legacy, in: Shinu Anna Abraham, Praveena Gullapalli, Teresa P. Raczek, Uzma Z. Rizvi, (Eds.), 2013, Connections and Complexity, New Approaches to the Archaeology of South Asia, Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, California, pp. 107-126) Hieroglyph III (three linear strokes): kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS singi 'horned' rebus: singi 'village headman' singi 'gold for ornaments'; koḍiyum 'neck ring' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'; khara 'onager (face)' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'; खोंड khōṇḍa 'A young bull' rebus: kunda, 'one of कुबेर's nine treasures', kundaṇa 'fine gold'. Composite hypertext, cyphertext: khōṇḍa khara singi kolom 'young bull, onager, one-horn (horned) rebus plain text: kōṇḍa kunda khār singi kolimi 'कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste, kō̃da कोँद 'kiln, furnace', fine-gold smith gold for ornaments smithy/forge'.

The reading of khara 'onager' ligatured to a young bovine is reinforced by:کر ś̱ẖʿkar or ḵ́ẖʿkar, 'horn' (Pashto) PLUS खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi). کار کند kār-kund (corrup. of P کار کن ) adj. Adroit, clever, experienced. 2. A director, a manager; (Fem.) کار کنده kār-kundaʿh. (Pashto) P کار kār, s.m. (2nd) Business, action, affair, work, labor, profession, operation.

Singin (adj.) [Vedic śṛngin] having a horn Vinii. 300; J iv. 173 (=cow); clever, sharp -- witted, false Th 1, 959; A ii. 26; It 112; cp. J.P.T.S. 1885, 53. Rebus: Singī & singi (f.) [cp. Sk. śṛngī] 1. gold Vin i. 38; S ii. 234; J i. 84. -- nada gold Vv 6428; VvA 284. -- loṇa ( -- kappa) license as to ginger & salt Vin ii. 300, 306. -- vaṇṇa gold-coloured D ii. 133. -- suvaṇṇa gold VvA 167.(Pali)

The Assyrian word, sakea mentioned in the cuneiform inscription is the following hieroglyph of the 'unicorn':

शृङ्गिन् śṛṅgin शृङ्गिन् a. (-णी f.) [शृङ्गमस्त्यस्य इनि] 1 Horned. -2 Crested, peaked. -m. 1 A mountain. -2 An elephant. -3 A ram. -4 A tree. -5 N. of Śiva. -6 N. of one of Śiva's attendants; शृङ्गी भृङ्गी रिटिस्तुण्डी Ak. -7 A bull; शङ्ग्यग्निदंष्ट्र्यसिजलद्विजकण्टकेभ्यः Bhāg.1.8.25. shrangश्रंग् । शृङ्गम्, प्रधानभूतः m. a horn; the top, peak, summit of a mountain (Kashmiri)

Hieroglyph, 'horned animal': siṅgin.'horned', having a horn Vinii. 300; J iv. 173 (=cow); clever, sharp -- witted, false Th 1, 959; A ii. 26; It 112; cp. J.P.T.S. 1885, 53. (Pali) OMarw. (Vīsaḷa) sīṁgī f.adj. ʻhorned (of cow)ʼ. (CDIAL 12595).

Rebus: singī & singi (f.) [cp. Sk. śṛngī] gold Vini. 38; S ii. 234; J i. 84 (Pali) śr̥ngī-कनकम् gold used for ornaments. शृङ्गिः śṛṅgiḥ शृङ्गिः Gold for ornaments. शृङ्गी śṛṅgī Gold used for ornaments.

The one-horned bovine is thus read as: kār kunda siṅgin 'gold for use in ornaments' (by) 'blacksmith, turner, goldsmith.' Singin 'clever, sharp -- witted, false Th 1, 959; Aii. 26; It 112; cp. J.P.T.S. 1885, 53.(Pali) is a synonym of کنده kār-kunda 'manager, director, adroit, clever, experienced' (Pashto) kunda1 m. ʻ a turner's lathe ʼ lex. [Cf. *cunda -- 1 ]N. kũdnu ʻ to shape smoothly, smoothe, carve, hew ʼ, kũduwā ʻ smoothly shaped ʼ; A. kund ʻ lathe ʼ, kundiba ʻ to turn and smooth in a lathe ʼ, kundowā ʻ smoothed and rounded ʼ; B. kũd ʻ lathe ʼ, kũdā, kõdā ʻ to turn in a lathe ʼ; Or. kū˘nda ʻ lathe ʼ, kũdibā, kū̃d˚ ʻ to turn ʼ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ʻ lathe ʼ); Bi. kund ʻ brassfounder's lathe ʼ; H. kunnā ʻ to shape on a lathe ʼ, kuniyā m. ʻ turner ʼ, kunwā m.(CDIAL 3295) kunda 'a treasure of Kubera'; kunda 'gold' kundaṇa 'fine gold'. Thus, of کنده kār-kunda singin signifies 'fine gold, gold for ornaments'.

This rebus decipherment of the frequently used hieroglyph of 'horn' explains why Shalamaneser III Black obelisk, which is a Rosetta stone for Indus Script displays a one-horned young bull as a tribute received from Musri. Third row from the top of the obelisk lists the tributes in the following sculptural friezes, together with a cuneiform inscription describing the details.

![]()

The reading of khara 'onager' ligatured to a young bovine is reinforced by:

Singin (adj.) [Vedic śṛngin] having a horn Vin

The Assyrian word, sakea mentioned in the cuneiform inscription is the following hieroglyph of the 'unicorn':

The answer, the Eureka moment for decipherment of Indus Script inscriptions is:

singin 'horned' rebus: singi 'gold used for ornaments'. Thus, the animal signifies gold used for ornaments as the tribute of the land of Musri to Shalameneser III.

Singa2 the young of an animal, calf J v. 92; cp. Deśīnāma- mālā viii. 31.(Pali)

शृङ्गिन् śṛṅgin शृङ्गिन् a. (-णी f.) [शृङ्गमस्त्यस्य इनि] 1 Horned. -2 Crested, peaked. -m. 1 A mountain. -2 An elephant. -3 A ram. -4 A tree. -5 N. of Śiva. -6 N. of one of Śiva's attendants; शृङ्गी भृङ्गी रिटिस्तुण्डी Ak. -7 A bull; शङ्ग्यग्निदंष्ट्र्यसिजलद्विजकण्टकेभ्यः Bhāg.1.8.25. shrang

Hieroglyph, 'horned animal': siṅgin.'horned', having a horn Vin

Rebus: singī & singi (f.) [cp. Sk. śṛngī] gold Vin

The one-horned bovine is thus read as: kār kunda siṅgin 'gold for use in ornaments' (by) 'blacksmith, turner, goldsmith.' Singin 'clever, sharp -- witted, false Th 1, 959; A

This rebus decipherment of the frequently used hieroglyph of 'horn' explains why Shalamaneser III Black obelisk, which is a Rosetta stone for Indus Script displays a one-horned young bull as a tribute received from Musri. Third row from the top of the obelisk lists the tributes in the following sculptural friezes, together with a cuneiform inscription describing the details.

Apart from sakea (animal with horn), there are other animals -- camels with two humps, river-ox, susu, elephant, monkeys, apes -- in the four sculptural frieze registers in row 3 of the Black obelisk of Shalamaneser III are also hieroglyphs which signify in Meluhha (Indian sprachbund, 'language union') tributes of wealth.

Rebus: singī & singi (f.) [cp. Sk. śṛngī] gold Vin

The one-horned bovine is thus read as: kār kunda siṅgin 'gold for use in ornaments' (by) 'blacksmith, turner, goldsmith.' Singin 'clever, sharp -- witted, false Th 1, 959; A

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.mēd 'body' (Kur.)(DEDR 5099); meḍ 'iron' (Ho.) Ta. mēṉi body, shape, colour, beauty; mēl body. Ma. mēni body, shape, beauty, excellence; mēl body. Koḍ. me·lï body. Te. mēnu id.; mēni brilliancy, lustre; belonging to the body, bodily, personal. Kol. me·n (pl.me·nḍl) body. Nk. mēn (pl. mēnuḷ) id. Nk. (Ch.) mēn id. Pa. mēn (pl. mēnul) id. Ga. (S.) mēnu (pl. mēngil), (P.) mēn id. Go. (Tr.) mēndur (obl. mēnduḍ-), (A. Y. W. M.) mēndul, (L.) meṇḍū˘l, (SR.) meṇḍol id. (Voc.2963). Konḍa mēndol human body. Kur. mē̃d, mēd body, womb, back. Malt. méth body (DEDR 5099)

Ta. kōṭu (in cpds. kōṭṭu-) horn, tusk, branch of tree, cluster, bunch, coil of hair, line, diagram, bank of stream or pool; kuvaṭu branch of a tree; kōṭṭāṉ, kōṭṭuvāṉ rock horned-owl (cf. 1657 Ta. kuṭiñai). Ko. ko·ṛ (obl.ko·ṭ-) horns (one horn is kob), half of hair on each side of parting, side in game, log, section of bamboo used as fuel, line marked out. To. kw&idieresisside;ṛ (obl. kw&idieresisside;ṭ-) horn, branch, path across stream in thicket. Ka. kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr̤ horn. Tu. kōḍů, kōḍu horn. Te. kōḍu rivulet, branch of a river. Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn. Ga. (Oll.) kōr (pl. kōrgul) id. Go. (Tr.) kōr (obl. kōt-, pl. kōhk) horn of cattle or wild animals, branch of a tree; (W. Ph. A. Ch.) kōr (pl. kōhk), (S.) kōr (pl. kōhku), (Ma.) kōr̥u (pl. kōẖku) horn; (M.) kohk branch (Voc. 980); (LuS.) kogoo a horn. Kui kōju (pl. kōska) horn, antler.

(DEDR 2200) Rebus: koḍ artisan's workshop (Kuwi) Ta. koṭṭakai shed with sloping roofs, cow-stall; marriage pandal; koṭṭam cattle-shed; koṭṭil cow-stall, shed, hut; (STD) koṭambe feeding place for cattle. Ma. koṭṭil cowhouse, shed, workshop, house. Ka. koṭṭage, koṭige, koṭṭige stall or outhouse (esp. for cattle), barn, room. Koḍ. koṭṭï shed. Tu. koṭṭa hut or dwelling of Koragars; koṭya shed, stall. Te. koṭṭā̆mu stable for cattle or horses; koṭṭāyi thatched shed. Kol. (Kin.) koṛka, (SR.) korkā cowshed; (Pat., p. 59) konṭoḍi henhouse. Nk. khoṭa cowshed. Nk. (Ch.) koṛka id. Go. (Y.) koṭa, (Ko.) koṭam (pl. koṭak) id. (Voc. 880); (SR.) koṭka shed; (W. G. Mu. Ma.) koṛka, (Ph.) korka, kurkacowshed (Voc. 886); (Mu.) koṭorla, koṭorli shed for goats (Voc. 884). Malt. koṭa hamlet. / Influenced by Skt. goṣṭha-. (DEDR 2058)

British Museum number103225 Baked clay plaque showing a bull-man holding a post.

Old Babylonian 2000BC-1600BCE Length: 12.8 centimetres Width: 7 centimetres Barcelona 2002 cat.181, p.212 BM Return 1911 p. 66On this terracotta plaque, the mace is a phonetic determinant of the bovine (bull) ligatured to the body of the person holding the mace. The person signified is: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ "... head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull...Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. British Museum. WCO2652. Bull-manTerracotta plaque. Bull-man holding a post. Mesopotamia, ca. 2000-1600 BCE."

Terracotta. This plaque depicts a creature with the head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull. Though similar figures are depicted earlier in Iran, they are first seen in Mesopotamian art around 2500 BC, most commonly on cylinder seals, and are associated with the sun-god Shamash. The bull-man was usually shown in profile, with a single visible horn projecting forward. However, here he is depicted in a less common form; his whole body above the waist, shown in frontal view, shows that he was intended to be double-horned. He may be supporting a divine emblem and thus acting as a protective deity.

Old Babylonian, about 2000-1600 BCE From Mesopotamia Length: 12.8 cm Width: 7cm ME 103225 Room 56: Mesopotamia Briish Museum

Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. While many show informal scenes and reflect the private face of life, this example clearly has magical or religious significance.

Hieroglyph carried on a flagpost by the blacksmith (bull ligatured man: Dhangar 'bull' Rebus: blacksmith')

I suggest that the hieroglyphs on selected artifacts of Nahal Mishmar deploy Indus Script Cipher

to signify metalwork wealth categories by the vidual codes of hieroglyphs such as birds, towers, ibexes.

R̥gveda 1.119.9, 10 speaks of the 'mystic science' of using mākṣikā, bees' and Dadhyãc bones. I suggest that this is a pun on the word: Hieroglyph: माक्षिक [p= 805,2] mfn. (fr. मक्षिका mākṣikā) coming from or belonging to a bee Ma1rkP. Rebus: माक्षिक n. a kind of honey-like mineral substance or pyrites MBh.

The metaphor used in R̥gveda 1.119.9 to produce madhu, i.e. Soma is a reference to use of pyrites to produce electrum Soma which is also referred to in R̥gveda as amśu cognate ancu 'iron' (Tocharian) अंशु [p= 1,1] a kind of सोम libation S3Br. (Monier-Williams)

I suggest that the references to pyrites and horse bones (of Dadhyãc) in RV 1.119.9 is a narrative of metallurgical process of cupellation to remove lead ores from pyrite ores --मक्षिका mākṣikā-- to realize pure metals such as gold, silver or copper.

See:

Gobekli Tepe (12k ya) and Nahal Mishmar (8k ya) Indus Scrript hypertexts relate to Ancient pyrotechnology

Indus Script Hieroglyph karaḍa 'aquatic bird' rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy metal' occurs on a Nahal Mishmar (6th millennium BCE) cire perdue artifact. The same artifact also signifies 'peg' hieroglyph: dāmā ʻ peg to tie a buffalo' (Assamese) rebus: dhāu 'mineral ore'.Hieroglyph: rivet: ṭaṅka3 (a) ʻ *rod, spike ʼ, (b) m. ʻ leg ʼ lex. 2. ṭaṅga -- 3 m. ʻ leg ʼ lex. [Orig. ʻ stick ʼ? Cf. list s.v. *ḍakka -- 2 ] 1. (a) K. ṭang m. ʻ projecting spike which acts as a bolt at one corner of a door ʼ; N. ṭāṅo ʻ rod, fishing rod ʼ, °ṅi ʻ measuring rod ʼ; H. ṭã̄k f. ʻ iron pin, rivet ʼ (→ Ku. ṭã̄ki ʻ thin iron bar ʼ).(b) Pk. ṭaṁka -- m., °kā -- f. ʻ leg ʼ, S. ṭaṅga f., L. P. ṭaṅg f., Ku. ṭã̄g, N. ṭāṅ; Or. ṭāṅka ʻ leg, thigh ʼ, °ku ʻ thigh, buttock ʼ.2. B. ṭāṅ, ṭeṅri ʻ leg, thigh ʼ; Mth. ṭã̄g, ṭãgri ʻ leg, foot ʼ; Bhoj. ṭāṅ, ṭaṅari ʻ leg ʼ, Aw. lakh. H. ṭã̄g f.; G. ṭã̄g f., °gɔ m. ʻ leg from hip to foot ʼ; M. ṭã̄g f. ʻ leg ʼ. *uṭṭaṅka -- 2 , *uṭṭaṅga -- . Addenda: ṭaṅka -- 3 . 1(b): S.kcch. ṭaṅg(h) f. ʻ leg ʼ, WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ṭāṅg f. (obl. -- a) ʻ leg (from knee to foot) ʼ. 2. ṭaṅga -- 3 : A. ṭāṅī ʻ wedge ʼ(CDIAL 5428) Rebus: ṭaṅkaśālā -- , ṭaṅkakaś° f. ʻ mint ʼ lex. [ṭaṅka -- 1 , śāˊlā -- ] N. ṭaksāl, °ār, B. ṭāksāl, ṭã̄k°, ṭek°, Bhoj. ṭaksār, H. ṭaksāl, °ār f., G. ṭãksāḷ f., M. ṭã̄ksāl, ṭāk°, ṭãk°, ṭak°. -- Deriv. G. ṭaksāḷī m. ʻ mint -- master ʼ, M. ṭāksāḷyā m.Addenda: ṭaṅkaśālā -- : Brj. ṭaksāḷī, °sārī m. ʻ mint -- master ʼ.(CDIAL 5434)

Hieroglyphs: pegs: dāmā ʻ peg to tie a buffalo' (Assamese) rebus: dhāu 'mineral ore'; kūṭa 'a peg, etc.'; kūṭi 'a hat turban peg or stand' (Kannada) khut.i Nag. (Or. khut.i_) diminutive of khuṇṭa, a peg driven into the ground, as for tying a goat (Mundari) khuṇṭi = pillar (Santali) Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' PLUS *skabha ʻ post, peg ʼ. [√skambh] Kal. Kho. iskow ʻ peg ʼ BelvalkarVol 86 with (?). SKAMBH ʻmake firmʼ (CDIAL 13638). Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236). Thus, the pegs signify: dhāu kuṭhi kammaṭa 'minerls smelter, mint'.

Indus Script Hieroglyph karaḍa 'aquatic bird' rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy metal' occurs on a Nahal Mishmar (6th millennium BCE) cire perdue artifact. The same artifact also signifies 'peg' hieroglyph: dāmā ʻ peg to tie a buffalo' (Assamese) rebus: dhāu 'mineral ore'.

Hieroglyph: rivet: ṭaṅka3 (a) ʻ *rod, spike ʼ, (b) m. ʻ leg ʼ lex. 2. ṭaṅga -- 3 m. ʻ leg ʼ lex. [Orig. ʻ stick ʼ? Cf. list s.v. *ḍakka -- 2 ] 1. (a) K. ṭang m. ʻ projecting spike which acts as a bolt at one corner of a door ʼ; N. ṭāṅo ʻ rod, fishing rod ʼ, °ṅi ʻ measuring rod ʼ; H. ṭã̄k f. ʻ iron pin, rivet ʼ (→ Ku. ṭã̄ki ʻ thin iron bar ʼ).(b) Pk. ṭaṁka -- m., °kā -- f. ʻ leg ʼ, S. ṭaṅga f., L. P. ṭaṅg f., Ku. ṭã̄g, N. ṭāṅ; Or. ṭāṅka ʻ leg, thigh ʼ, °ku ʻ thigh, buttock ʼ.2. B. ṭāṅ, ṭeṅri ʻ leg, thigh ʼ; Mth. ṭã̄g, ṭãgri ʻ leg, foot ʼ; Bhoj. ṭāṅ, ṭaṅari ʻ leg ʼ, Aw. lakh. H. ṭã̄g f.; G. ṭã̄g f., °gɔ m. ʻ leg from hip to foot ʼ; M. ṭã̄g f. ʻ leg ʼ. *uṭṭaṅka -- 2 , *uṭṭaṅga -- . Addenda: ṭaṅka -- 3 . 1(b): S.kcch. ṭaṅg(h) f. ʻ leg ʼ, WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ṭāṅg f. (obl. -- a) ʻ leg (from knee to foot) ʼ. 2. ṭaṅga -- 3 : A. ṭāṅī ʻ wedge ʼ(CDIAL 5428) Rebus: ṭaṅkaśālā -- , ṭaṅkakaś° f. ʻ mint ʼ lex. [ṭaṅka -- 1 , śāˊlā -- ] N. ṭaksāl, °ār, B. ṭāksāl, ṭã̄k°, ṭek°, Bhoj. ṭaksār, H. ṭaksāl, °ār f., G. ṭãksāḷ f., M. ṭã̄ksāl, ṭāk°, ṭãk°, ṭak°. -- Deriv. G. ṭaksāḷī m. ʻ mint -- master ʼ, M. ṭāksāḷyā m.Addenda: ṭaṅkaśālā -- : Brj. ṭaksāḷī, °sārī m. ʻ mint -- master ʼ.(CDIAL 5434)

Hieroglyphs: pegs: dāmā ʻ peg to tie a buffalo' (Assamese) rebus: dhāu 'mineral ore'; kūṭa 'a peg, etc.'; kūṭi 'a hat turban peg or stand' (Kannada) khut.i Nag. (Or. khut.i_) diminutive of khuṇṭa, a peg driven into the ground, as for tying a goat (Mundari) khuṇṭi = pillar (Santali) Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' PLUS *skabha ʻ post, peg ʼ. [√skambh] Kal. Kho. iskow ʻ peg ʼ BelvalkarVol 86 with (?). SKAMBH ʻmake firmʼ (CDIAL 13638). Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236). Thus, the pegs signify: dhāu kuṭhi kammaṭa 'minerls smelter, mint'.

Hieroglyphs: pegs: dāmā ʻ peg to tie a buffalo' (Assamese) rebus: dhāu 'mineral ore'; kūṭa 'a peg, etc.'; kūṭi 'a hat turban peg or stand' (Kannada) khut.i Nag. (Or. khut.i_) diminutive of khuṇṭa, a peg driven into the ground, as for tying a goat (Mundari) khuṇṭi = pillar (Santali) Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' PLUS *skabha ʻ post, peg ʼ. [√skambh] Kal. Kho. iskow ʻ peg ʼ BelvalkarVol 86 with (?). SKAMBH ʻmake firmʼ (CDIAL 13638). Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236). Thus, the pegs signify: dhāu kuṭhi kammaṭa 'minerls smelter, mint'.

Hieroglyph: *skabha ʻ post, peg ʼ. [√skambh ]Kal. Kho. iskow ʻ peg ʼ BelvalkarVol 86 with (?).SKAMBH ʻ make firm ʼ: *skabdha -- , skambhá -- 1 , skámbhana -- ; -- √*chambh. skambhá1 m. ʻ prop, pillar ʼ RV. 2. ʻ *pit ʼ (semant. cf. kūˊpa -- 1 ). [√skambh ]1. Pa. khambha -- m. ʻ prop ʼ; Pk. khaṁbha -- m. ʻ post, pillar ʼ; Pr. iškyöp, üšköb ʻ bridge ʼ NTS xv 251; L. (Ju.) khabbā m., mult. khambbā m. ʻ stake forming fulcrum for oar ʼ; P. khambh, khambhā, khammhā m. ʻ wooden prop, post ʼ; WPah.bhal. kham m. ʻ a part of the yoke of a plough ʼ, (Joshi) khāmbā m. ʻ beam, pier ʼ; Ku. khāmo ʻ a support ʼ, gng. khām ʻ pillar (of wood or bricks) ʼ; N. khã̄bo ʻ pillar, post ʼ, B. khām, khāmbā; Or. khamba ʻ post, stake ʼ; Bi. khāmā ʻ post of brick -- crushing machine ʼ, khāmhī ʻ support of betel -- cage roof ʼ, khamhiyā ʻ wooden pillar supporting roof ʼ; Mth. khāmh, khāmhī ʻ pillar, post ʼ, khamhā ʻ rudder -- post ʼ; Bhoj. khambhā ʻ pillar ʼ, khambhiyā ʻ prop ʼ; OAw. khāṁbhe m. pl. ʻ pillars ʼ, lakh. khambhā; H. khām m. ʻ post, pillar, mast ʼ, khambh f. ʻ pillar, pole ʼ; G. khām m. ʻ pillar ʼ, khã̄bhi , °bi f. ʻ post ʼ, M. khã̄b m., Ko. khāmbho, °bo, Si. kap (< *kab); -- X gambhīra -- , sthāṇú -- , sthūˊṇā -- qq.v.2. K. khambü rü f. ʻ hollow left in a heap of grain when some is removed ʼ; Or. khamā ʻ long pit, hole in the earth ʼ, khamiā ʻ small hole ʼ; Marw. khã̄baṛo ʻ hole ʼ; G. khã̄bhũ n. ʻ pit for sweepings and manure ʼ.*skambhaghara -- , *skambhākara -- , *skambhāgāra -- , *skambhadaṇḍa -- ; *dvāraskambha -- . Addenda: skambhá -- 1 : Garh. khambu ʻ pillar ʼ.(CDIAL 13638, 13689) *skambha2 ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, plumage ʼ. [Cf. *skapa -- s.v. *khavaka -- ]S. khambhu, °bho m. ʻ plumage ʼ, khambhuṛi f. ʻ wing ʼ; L. khabbh m., mult. khambh m. ʻ shoulder -- blade, wing, feather ʼ, khet. khamb ʻ wing ʼ, mult. khambhaṛā m. ʻ fin ʼ; P. khambh m. ʻ wing, feather ʼ; G. khā̆m f., khabhɔ m. ʻ shoulder ʼ.(CDIAL 13640) rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'

See:

See:

Nahal Mishmar hieroglyphs on 'crowns' signify smithy/temple in fortified town producing hard metal alloys http://tinyurl.com/njzvx7f

Foundation peg on the Nahal Mishmar arsenic-bronze 'crown' reinforces the nature of the horned building: kole.l 'smithy' Rebus: kole.l 'temple'. The artefacts might have been carried in procession from the smithy/temple to declare/announce the metallurgical repertoire of the artisans of the 5th millennium BCE, Nahal Mishmar.

Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village. To. kwala·l Kota smithy.

Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ka. kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace; (Bell.; U.P.U.) konimi blacksmith (Gowda) kolla id. Koḍ. kollë blacksmith.

Te. kolimi furnace. Go. (SR.) kollusānā to mend implements; (Ph.) kolstānā, kulsānā to forge; (Tr.) kōlstānā to repair (of ploughshares); (SR.) kolmi smithy (Voc. 948). Kuwi (F.) kolhali to forge. (DEDR 2133)

I suggest that the so-called crowns of Nahal Mishmar are stacked-up cylindrical rings, components of a rebus-metonymy layered representations of a smithy and objects out of the smithy: karaḍā 'hard metal alloys'. The structure of the horned building: koṭṭa -- , kuṭ° n.; Kt. kuṭ ʻ tower (?) (Prakritam). I agree with Irit Ziffer that the artefacts are NOT crowns.

The two birds on the edge of the crown are aquatic birds:

Hieroglyph: కారండవము [kāraṇḍavamu] n. A sort of duck. కారండవము [ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. कारंडव [kāraṇḍava ] m S A drake or sort of duck. कारंडवी f S The female. karandava [ kârandava ] m. kind of duck. कारण्ड a sort of duck R. vii , 31 , 21 கரண்டம் karaṇṭam, n. Rebus: Rebus: karaḍā ‘hard alloy’ (Marathi)

Hieroglyphy: horns: Ta. kōṭu (in cpds. kōṭṭu-) horn, tusk, branch of tree, cluster, bunch, coil of hair, line, diagram, bank of stream or pool; kuvaṭu branch of a tree; kōṭṭāṉ, kōṭṭuvāṉ rock horned-owl (cf. 1657 Ta. kuṭiñai). Ko. ko·ṛ (obl. ko·ṭ-) horns (one horn is kob), half of hair on each side of parting, side in game, log, section of bamboo used as fuel, line marked out. To. kw&idieresisside;ṛ (obl.kw&idieresisside;ṭ-) horn, branch, path across stream in thicket. Ka.

kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr̤ horn. Tu. kōḍů, kōḍu horn. Te. kōḍu

rivulet, branch of a river. Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn. Ga. (Oll.) kōr (pl. kōrgul) id. Go. (Tr.) kōr (obl. kōt-, pl. kōhk) horn of cattle or wild animals, branch of a tree; (W. Ph. A. Ch.) kōr (pl. kōhk), (S.) kōr (pl. kōhku), (Ma.) kōr̥u (pl. kōẖku)horn; (M.) kohk branch (Voc. 980); (LuS.) kogoo a horn. Kui kōju (pl. kōska) horn, antler. (DEDR 2200) Rebus: fortified town: kōṭṭa1 m. (n. lex.) ʻ fort ʼ Kathās., kōṭa -- 1 m. Vāstuv. Aś. sn. koṭa -- ʻ fort, fortified town ʼ, Pk. koṭṭa -- , kuṭ° n.; Kt. kuṭ ʻ tower (?) ʼ NTS xii 174; Dm. kōṭ ʻ tower ʼ, Kal. kōṭ; Sh. gil. kōṭ m. ʻ fort ʼ (→ Ḍ. kōṭ m.), koh. pales. kōṭ m. ʻ village ʼ; K. kūṭh, dat. kūṭas m. ʻ fort ʼ, S. koṭu m., L. koṭ m.; P. koṭ m. ʻ fort, mud bank round a village or field ʼ; A. kõṭh ʻ stockade, palisade ʼ; B. koṭ, kuṭ ʻ fort ʼ, Or. koṭa, kuṭa, H. Marw. koṭ m.; G. koṭ m. ʻ fort, rampart ʼ; M. koṭ, koṭh m. ʻ fort ʼ, Si. koṭuva (Geiger EGS 50 < kōṣṭhaka -- ).Addenda: kōṭṭa -- 1 : A. kõṭh ʻ fort ʼ and other lggs. with aspirate and meaning ʻ fort ʼ perh. X kṓṣṭha (CDIAL 3500).

Ruth Amiran reconstructs the gate-like projections on a multi-tiered layers of copper crowns. The superimposed drums of composite stand-like objects, cult stands or altars might have been stacked up as shown in the figure:

Cult stand/altar made of superimposed crowns, as reconstructed by Amiran (Amiran, Ruth, 1985, A suggestion to see the copper 'crowns' of the Judean Desert in treasure as Drums of Stand-like altars, in: Palestine in the Bronze and Iron Ages: Papers in honour of Olga Tufnell, ed. JN Tubb, 10-14, London, Institute of Archaeology, fig.1)

Late Uruk cylinder seal impression from Susa depicting war scene with horned building (Amiet, Pierre, 1987, Temple sur terrasse on fortressa? RA 81:99-104, fig.1)

Siege of Kishesim, Khorsabad (Amiet, Pierre, 1987, Temple sur terrasse on fortressa? RA 81:99-104, fig.4)

Elamite edifice adorned with bull horns, Nineveh (Potts, Daniel T., 1990,

Some horned buildings in Iran, Mesopotamia and Arabia, RA 84: 33-40, fig.2)

See: https://www.academia.edu/2093398/A_Note_on_the_Nahal_Mishmar_Crowns

Irit Ziffer, A note on the Nahal Mishmar 'crowns' in:

Jack Cheng, & Marian H Feldman, eds., 2007, Ancient Near Eastern Art in Context, BRILL., pp. 47-67.Addendum on carbon-14 dating of Nahal Mishmar finds to ca. +4400 BCE:

Table 10.6 Radiocarbon determinations from Nahal Mishmar

Source: https://www.academia.edu/3427110/_2010_Developmental_Trends_in_Chalcolithic_Copper_Metallurgy_A_Radiometric_Perspective_Shugar_and_Gohm_

"The specialty of Dhokra handicraft is that each relic seems to have been made up of a seamless wire coiled around the clay article. This is indeed an illusion as the metal casting is done using the lost-wax technique which forms the main attraction of this craft. It is believed that the lost-wax technique for copper casting had been found in other East Asian, Middle-East and Central American regions as well. In Purulia, the Dhokras make mixed aluminum by the lost wax process but do not make any images or figures; they rather make paikona, dhunuchi, pancha pradeep, anklets, and ghunghrus.

Dhokra metal casting is generally famous for unique artefacts like animals, jewelry, piggybank (Buli), ornamented pots and various deities. In the genre of jewelry: payeri (anklets), hansuli (necklace), earrings and bangles are most in demand because of the style statement they impart. The single and multiple diya lamps are, even molded in the forms of elephants, and are considered auspicious for many Hindu occasions. Dhokra is the only live example of the metal casting in the East India as other similar crafts have faded away with time. But unfortunately, no substantial initiatives have been taken to promote and help sustain the Dhokra art in recent times in West Bengal." http://indianscriptures.com/vedic-society/arts/arts-and-traditions-of-west-bengal

"Carbon-14 dating of the reed mat in which the objects were wrapped suggests that it dates to at least 3500 B.C." http://www.metmuseumorg/toah/hd/nahl/hd_nahl.htm

" I-1819, which comes from a piece of cloth found in a burial in nearby Cave 2, is slightly younger, but another short-lived sample, I-616 from the Cave of Horror at Nahal Hever, gave a result in the late 5th millennium." https://journals.

להתראות, עוזי.

I deeply appreciate the help provided by Dr. Uzi Avner for this update. I will provide the 2011 citation for the new C-14 dating in an addendum in due course.

Dr. Uzi Avner notes that "The first seminar, the reference in Nahal Mishmar hoard interesting but requires updating - a series of dates Carbon relatively new (2011) indicates ± 4400 BC, not the end of the fourth millennium."

This insight of Dr. Uzi Avner has a profound impact on chronology studies of the evolution of bronze age and writing systems.

Presence of dhokra (lost-wax artisans) in Nahal (Nachal) Mishmar is stunning and points to ancient Israel-India connections from 5th millennium BCE. I had noted that the two pure tin ingots found in Haifa shipwreck had Meluhha hieroglyphs to denote tin. ranku 'antelope'; ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku 'tin (cassiterite) ore'. S. Kalyanaraman, 2010, The Bronze Age Writing System of Sarasvati Hieroglyphics as Evidenced by Two “Rosetta Stones” - Decoding Indus script as repertoire of the mints/smithy/mine-workers of Meluhha, Journal of Indo-Judaic Studies, Number 11, pp. 47-74

Dhokra cire perdue (lost-wax) is a brilliant bronze age invention and should herald a new approach to explain the hieroglyphs on thousands of cylinder seals of the Fertile Crescent right from the chalcolithic times (ca. 5th millennium BCE -- now based on Nahal Mishmar new carbon-14 datings) into the bronze age.

Also that harosheth hagoyim is cognate with kharoṣṭī goya lit. 'blacksmith lip guild'.

It is interesting that Dr. Moti Shemtov refers to Nahal Mishmar as Nachal Mishmar. It is similar to the change from Meluhha to Mleccha !

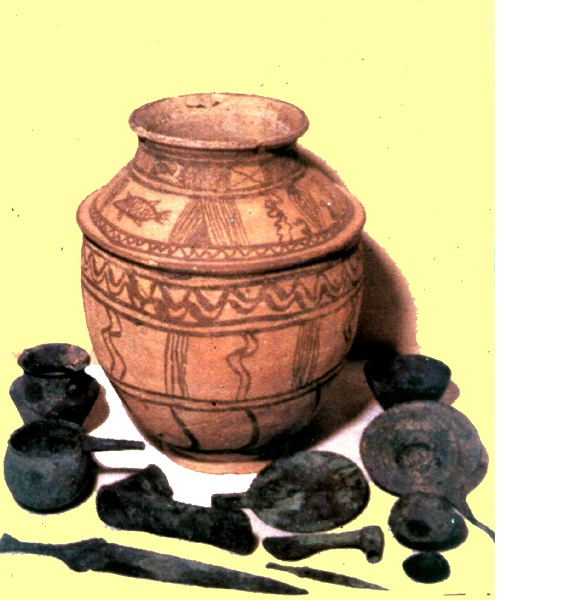

This Nahal Mishmar copper stand might have held a storage pot with a pointed bottom or a pot like the Susa pot which had a 'fish' hieroglyph and metal artifacts of tools and vessels. The Meluhha hieroglyph 'fish' read: ayo 'fish' (Munda) Rebus: ayo 'metal alloy' (Gujarati. Pali) It could also have held a Burzahom type-pot with beads and a buffalo-horn hieroglyph.

Dr. Uzi Avner notes that "The first seminar, the reference in Nahal Mishmar hoard interesting but requires updating - a series of dates Carbon relatively new (2011) indicates ± 4400 BC, not the end of the fourth millennium."

Dhokra cire perdue (lost-wax) is a brilliant bronze age invention and should herald a new approach to explain the hieroglyphs on thousands of cylinder seals of the Fertile Crescent right from the chalcolithic times (ca. 5th millennium BCE -- now based on Nahal Mishmar new carbon-14 datings) into the bronze age.

- Worlds Largest Bronze Nataraja.This is the largest bronze Nataraja in the world approx. 8ft high, bigger than the Chidambaram Nataraja.Chola Bronze at Thirunallam. Konerirajapuram is about half hour drive from Kumbakonam, in Mayiladithurai taluka of Nagapattinam district in Tamil Nadu.

The word dhokra is represented as a hieroglyph on two Indus seals from Dholavira and Mohenjo-daro. Now we know that the word means 'cire perdue' or lost-wax technology for metal alloys to create bronze/brass statues, tools and weapons. This was arrival of the bronze age with a bang! contributed by dhokra artisans who live today in India and are called dhokra kamar.

Hieroglyph:

ḍŏkuru-ḍŏkuru; । कुब्जावस्था m. (sg. dat. ḍŏkaris-ḍŏkaris ड्वकरिस््-ड्वकरिस् ), the condition of a bent or humpbacked person (from old age, injury to the spine, or the like). Cf. ḍŏkhürü and dọ̆ku. -- dyunu -- । कार्श्ये&1;पि कार्यविधानम् m.inf. to do a little work as best one can when one is bent by old age.(Kashmiri) 1. Ku. ḍokro, ḍokhro ʻ old man ʼ; B. ḍokrā ʻ old, decrepit ʼ(CDIAL 5567).

ټوقړ ṯṯūḳaṟṟ s.m. (5th) An old or decrepit man. Pl.ټوقړان ṯṯūḳaṟṟān. See ټاقړ (Pashto)

?Allograph: 1. N. ḍhoknu, ḍhognu ʻ to bow down before, salute respectfully ʼ; H. ḍhoknā ʻ to lean against ʼ; -- Ku. ḍhok ʻ obeisance ʼ, N. ḍhok, ḍhog -- bheṭ (whence -- g in verb), H. ḍhok f., OMarw. ḍhoka f.2. H. dhoknā ʻ to bow down before ʼ, dhok f. ʻ obeisance ʼ.(CDIAL 5611). Go. (Mu.) doṛī- to bow (DEDR 3525).

W .) 1. A kind of ola covering to protect fruits on the tree; மரத் திற் பழங்களைப் பொதிந்துவைக்கும் ஓலைமறைவு. 2. A small ola-basket for fruit; பழம் வைக்குஞ் சிறு கூடை. See other etyma embedded from CDIAL in an earlier blogpost URL cited.

Rebus:

Hieroglyph:

ḍŏkuru-ḍŏkuru

ټوقړ ṯṯūḳaṟṟ s.m. (5th) An old or decrepit man. Pl.

dŏkuru परिघः a kind of hammer for use in metal-work, with a drum-shaped head. (El. dauker; L. 46, dokar; Śiv. 1563.) dŏkȧri-dab दब् । कूटाघातः m. hitting with a hammer, esp. the welding together of heated metal. -- dan -दन् । लघुकूटदण्डः m. the wooden handle of such a hammer. (Kashmiri)

धोकाळ [ dhōkāḷa ] m C A large blazing fire.(Marathi)

धोकाळ [ dhōkāḷa ] m C A large blazing fire.(Marathi)

dukra

Dhokra kamr or gharua of Bankura, Purulia, Midnapore, Burdwan in West Bengal, Malhars of Jharkhand and Sithrias of Orissa and Vis'wakarma of Tamil Nadu and Kerala also use the dhokra technique of metal casting.

That we are discussing dhokra art still practiced in India today may be seen

from

Dhokra. Mother with five children

Susa pot.Louvre Museum..

English: Pot depicting horned figure. Burzahom (Kashmir), 2700 BC. National Museum, New Delhi. Noticed in the museum : the pot depicts horned motifs, which suggests extra territorial links with sites like Kot-Diji, in Sindh.

Français : Pot orné d'incisions et de motifs peints portant de grandes cornes recourbées, qui laissent supposer des liens extra territoriaux avec des sites tels que Kot-Diji, dans le Sindh. H env. 50cm. Site archéologique de Burzahom (Kashmir) daté 2700 av. J.-C. Musée National, New Delhi

Part of the copper hoard discovered in 1961, in Nahal Mishmar. "Hidden in a natural crevice and wrapped in a straw mat, the hoard contained 442 different objects: 429 of copper, six of hematite, one of stone, five of hippopotamus ivory, and one of elephant ivory. Many of the copper objects in the hoard were made using the lost-wax process, the earliest known use of this complex technique. For tools, nearly pure copper of the kind found at the mines at Timna in the Sinai Peninsula was used. However, the more elaborate objects were made with a copper containing a high percentage of arsenic (4–12%), which is harder than pure copper and more easily cast.Radiocarbon dating showed that they were from the Chalcolithic or Copper Age, between 4000 and 3500 BC." (Note: Now revised date points to 4400 BCE).

FRIDAY, APRIL 6, 2012

Most treasure objects are made of copper containing a variable percentage of arsenic, but always high ( 4 % -12 %). Most surprising is that this special copper was used only on objects made with the lost wax technique rather simple chisels and hammers, lso found that 16. This distinction is also present in other sites . There is therefore a clear difference in the use of the two types of copper . For votes almost pure copper was used , although softer , for special objects no longer , harder and easier to empty arsenical copper was used.

The whole treasure is a magnificent collection of art objects. The objects are made of valuable materials , maintain high technological quality and have a superior finish . Their shapes witness to a developed artistic sense. It can be assumed , in view of the decorative motifs , which is a rich repository of religious symbolism.

a) Crowns

The cache ten cylindrical objects that seem crowns, with a diameter of 15'6 to 19 inches , and a height of 7 inches to 11'7 found. Two are provided with small feet. The body sometimes takes an incised decoration varied design : parallel lines , triangles and bands as Fishbone .

b ) The scepters

This is a group of 118 different objects , with lengths ranging from 7 to 40 inches. Some of the scepters retained traces of wooden handles or cane , and some was a black sticky substance. This has led archaeologists to conclude that the objects were taken on long poles , perhaps in sacred processions. A linen thread found in one of the Sceptres may indicate that they are bound lightweight materials such as tapes . All scepters are similar in shape but differ greatly in their size and detail of its decoration. The most splendid has five heads of animals (four of ibex and an animal with twisty horns) . It should be noted that similar scepters found at other sites .

c ) The poles

This term describes a group of stylized , long and solid scepters . Three of them appear refined versions of scepters with curved ends. The fourth is like the stem of a plant and the fifth has a flat head hooked .

d ) The sets standards

The three splendid banners of this group were definitely mounted on poles . The first is a hollow pear-shaped object with two twins ibex represented with one body , four legs and two heads. Each ibex is facing one of the biggest arms, one ax-shaped and the other knife , leaving the piriform body . The second banner has a short hollow columnilla a rectangular panel that extends from the center , made in the form of a vulture with outstretched wings. The third is more modest ; swelling part of his plans four protruding out in four different directions.

e) The horn-shaped objects

Three objects in the form of curved horn emphasize the importance of the horns in the Chalcolithic ritual. Two of the horns lead schematic figures of birds.

f ) Containers

A jug turtleneck beautiful proportions , a cup or deep bowl and three cups shaped basket with high vertical handle are the only containers found in the treasure.

g) maceheads

The largest group of objects with a total of 261 , including several thickened (rounded , pear-shaped , elongated or discoidal ) forms that are usually called " mace heads " objects. All have a hole in the center to insert a handle . Some specimens preserved remains of wooden handles . The surface is well polished and all undecorated .

Although the mace-head was a common weapon in Mesopotamia and Egypt , these objects may not to be considered as weapons. Their presence in the treasure seems, rather, a ceremonial use. If similarity with convex parts of the banners and scepters supports this view .

Six mace heads were made of hematite , Natural iron oxide . Were emptied but not drilled , as yet no technology known iron work . Another club head is made of hard limestone .

h ) The objects made of hippo tusk

Five mysterious objects were hidden along with objects of copper hippopotamus ivory , sectioned along the tusk shaped scythe. Are perforated by three rows of round holes , and in the middle of each there is a hole with a protruding edge .

i ) Cash ivory

Final object of one type is an ivory box 38 inches long made with a piece of elephant tusk well polished .

Translation from Spanish.http://curiosomundoazul.blogspot.in/2011/07/el-tesoro-de-nahal-mishmar.html

| ||||

Mysteries of the Copper Hoard Fifty years have passed since Pessah Bar-Adon discovered, in a cave in the Judean Desert canyon of Nahal Mishmar, the biggest hoard of ancient artifacts ever found in the Land of Israel: 429 copper objects, wrapped in a reed mat. Five decades and dozens of academic papers after their discovery, the enigma of how and why these 6,000-year-old ritual objects ended up in a remote cave in the Judean Desert is still unsolvedBy Yadin Roman Extracted from ERETZ Magazine, June-July 2011 | ||||

The Forum for the Research of the Chalcolithic Period, "a group of academics interested in this prehistoric age", according to Dr. Ianir Milevski (Israel Antiquities Authority), gathered on June 2 at the Israel Museum in Jerusalem in order to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery of the most important find from this period: the Nahal Mishmar copper hoard. After a day of presenting new insights pertaining to the copper objects, the conference wrapped up with a discussion on the source of the items in the cave and the reason they were hidden there. The debate emphasized what has remained unsolved after 50 years of research: while it is widely accepted that the hoard is an assembly of ritual objects, there still is no agreement or plausible reason as to where the objects came from and why they were stashed away. The treasure was found while looking for something completely different. In 1947, Bedouins from the Ta’amireh tribe, who roamed the Judean Desert, discovered ancient parchments hidden in the caves of the sheer cliffs of the canyons leading down to the Dead Sea. Once it was discovered that these brittle parchments could bring in money when sold to dealers in Bethlehem and Jerusalem, the Bedouins turned into avid archaeologists, scouring the desert caves in search of ancient scrolls. In the 1950s, new scrolls sold to the dealers in Bethlehem, which was part of Jordan at the time, led archaeologists working in Jordan to discover letters and other artifacts in Nahal Murabba’at, south of Qumran, where the Dead Sea Scrolls had been found. As more pieces of ancient scrolls began to appear in the antiquities market, it was clear that some of them were coming from the Israeli side of the Judean Desert. The desert border between Israel and Jordan was a straight unmarked line on the map, inaccessible to vehicles. The Bedouins, even if they had heard of the newly set-up border, did not recognize it and crossed over freely from side to side. Immediately after the War of Independence, Prof. Eliezer Sukenik, the dean of Israeli archaeologists and the father of Yigael Yadin, discussed the need to survey the caves on the Israeli side of the Judean Desert. Sukenik had purchased the first three complete Dead Sea Scrolls on the eve of the War of Independence and his son would later purchase the four remaining complete scrolls in New York. The year that Sukenik died, 1953, the first, impromptu Israeli desert cave survey was conducted. | ||||

Addendum on carbon-14 dating of Nahal Mishmar finds to ca. +4400 BCE:

Table 10.6 Radiocarbon determinations from Nahal Mishmar

https://www.academia.edu/attachments/31198898/download_file 10. Developmental Trends in Chalcolithic Copper Metallurgy: A Radiometric Perspective -- Aaron N. Shugar and Christopher J. Gohm

http://www.scribd.com/doc/198085507/Shugar-and-Gohm-Chapter-10-2010-in-Print

Radiometric evidence from Nahal Mishmar (Cave 1) is complicated, as dates both old and new offer contradictory information (Table 10.6). For the most part, these contradictions are related to the dating of the reed mat in which the hoard was wrapped (ARP-series, BM-140, I-285 and W-1341, the last three of which are included here for comparative purposes only, as they were measured very early in the history of the technique and may not be entirely reliable). These nine dates suggest that the mat was an ancient heirloom repaired occasionally over time, as they ‘spread out in at least three groups over a millennium or more … and that such repairs may be responsible for the divergent 14C ages from different portions of the mat’ (Aardsma 2001, 1251–3).

Owing to the incredible variations between these determinations the date of the reed mat contributes little to the present discussion, and instead other samples from Cave 1 should be considered. A sample from another reed mat (RT-1407) yielded a date between the 40th and 37th centuries cal BCE, while a sample from a possible loom fragment (RT-1409) appears to date between the 44th and 41st centuries cal BCE (Carmi and Segal 1992, 131). A third date originating from the haft of one of the copper standards (I-353), between the 40th and 34th centuries cal BCE, also deserves mention despite its age (measured inthe 1960s) (Weinstein 1984, 335). These determinations are not statistically the same, and the sub-periods best represented by these three dates are D followed by E, suggesting significant activity at Nahal Mishmar from the 39th to the 36th centuries cal BC (there is also a concentration of radiocarbon years in sub-period B, but these are strongly outweighed by those of D and E). Based on these determinations and the stratigraphic context of the hoard itself, it would be very difficult to push the date of the hoard’s deposition earlier than the first quarter of the 4th millennium cal BCE (a conclusion also reached by Moorey (1988, 173)).

http://www.scribd.com/doc/56148616/Besenval-Roland-2005 Shahi-Tump leopard weight.Leopard weight. Shahi-Tump (Balochistan).

Meluhha hieroglyphs; rebus readings: Leopard, kharaḍā; rebus:karaḍā 'hard alloy from iron, silver etc.'; ibex or markhor 'meḍh' rebus: ‘iron stone ore, metal merchant.’

खरडा [ kharaḍā ] A leopard. खरड्या [ kharaḍyā ] m or खरड्यावाघ m A leopard (Marathi). Kol. keḍiak tiger. Nk. khaṛeyak panther. Go. (A.) khaṛyal tiger; (Haig) kariyāl panther Kui kṛāḍi, krānḍi tiger, leopard, hyena. Kuwi (F.) kṛani tiger; (S.) klā'ni tiger, leopard; (Su. P. Isr.) kṛaˀni (pl. -ŋa) tiger. / Cf. Pkt. (DNM) karaḍa- id. (CDIAL 1132+). Rebus 1: kharādī ‘ turner, a person who fashions or shapes objects on a lathe’ (Gujarati) Rebus 2: करड्याची अवटी [ karaḍyācī avaṭī ] f An implement of the goldsmith. Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

miṇḍāl ‘markhor’ (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120); rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda)Lothal seal L048 Ibex. Another hieroglyph shown on the seal: ayo 'fish' rebus: ayo 'metal alloy' (Gujarati); ayas 'metal' (Sanskrit)

Fish sign incised on copper anthropomorph, Sheorajpur, upper Ganges valley, ca. 2nd millennium BCE, 4 kg; 47.7 X 39 X 2.1 cm. State Museum, Lucknow (O.37) Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo, ayas ‘metal. Thus, together read rebus: ayo meḍh ‘iron stone re, metal merchant.’

meḷh ‘goat’ (Br.) Rebus: meḍho ‘one who helps a merchant’ vi.138 ‘vaṇiksahāyah’ (deśi. Hemachandra). Allograph: meṛgo = with horns twisted back; meṛha, m., miṛhi f.= twisted, crumpled, as a horn (Santali)

Nahal Mishmar evidence of cire perdue metal casting, R̥gveda evidence of cupellation of mākṣika 'pyrites' to gain amśu, ancu 'iron' in Ancient Pyrotechnology

https://tinyurl.com/ybd3lyux

Some evidences from Nahal Mishmar artifacts and R̥gveda texts are discussed in this monograph. Both categories of evidence may be relevant to identify or hypothesise on techniques of Ancient Pyrotechnology of Gobekli Tepe Pre-pottery neolithic period (ca. 10th millennium BCE).

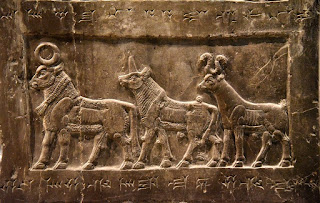

"The depictions of horned animals, birds, human noses and other motifs found on the artifacts are not just random decorations or symbolic images, claims Nissim Amzallag, a researcher from the Department of Bible studies, Archeology and the Ancient Near East at Ben Gurion University.

Amzallag, who focuses on the cultural origins of ancient metallurgy, theorizes that these representations form a rudimentary three-dimensional code, in which each image symbolizes a word or phrase and communicates a certain concept."

http://archaeologynewsreport.blogspot.com/2019/08/nahal-mishmar-hoard-one-of-earliest.html Archaeology News Report by Jonathan Kantrowitz, Aug. 5, 2019.

https://www.academia.edu/40265596/Nahal_Mishmar_evidence_of_hieroglyphs_and_link_with_writing_system_of_Indus_Script_dated_to_ca_3300_BCE

Nahal Mishmar evidence of hieroglyphs and link with writing system of Indus Script, dated to ca 3300 BCE

https://www.academia.edu/34039274/The_Nahal_Mishmar_Hoard_and_Chalcolithic_Metallurgy_in_Israel

The Nahal Mishmar Hoard and Chalcolithic Metallurgy in Israel.

Eretz-Israel , 1996

nissamz@post.bgu.ac.il

Nissim Amzallag, 2018, Visual code in the Nahal Mishmar Hoard. The earliest case of proto-writing? Antiguo Oriente, Vol. 16, 2018

NahalMishmar evidences of cire perdue metal casting artifacts are dated to 6th millennium BCE. R̥gveda textual evidences relate to metalworking processes of a period earlier than 7th millennium BCE. This note claims that aspects of metalwork related to Ancient Pyrotechnology are: 1 cire perdue technique of metal casting and 2. use of cupellation to obtain purified metals from working with pyrites and mineral ores in furnaces, kilns or fire-altars.

Many conjectures have been made on the role of the horse bones of Dadhyãc in Soma processing. I suggest that the use of bones is for cupellation process to oxidise lead iin pyrites, as 'litharge cakes of lead monoxide', thus removing lead from the mineral ores. A cupel which resembles a small egg cup, is made of ceramic or bone ash which was used to separate base metals from noble metals -- to separate noble metals, like gold and silver, from base metals like lead, copper, zinc, arsenic, antimony or bismuth, present in the ore. "The base of the hearth was dug in the form of a saucepan, and covered with an inert and porous material rich in calcium or magnesium such as shells, lime, or bone ash.The lining had to be calcareous because lead reacts with silica (clay compounds) to form viscous lead silicate that prevents the needed absorption of litharge, whereas calcareous materials do not react with lead.[7]Some of the litharge evaporates, and the rest is absorbed by the porous earth lining to form "litharge cakes".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cupellation

![]() Brass moulds for making cupels.Mixture of bones and wood ashes are used, together with clay, to create the cupels for cupellation.

Brass moulds for making cupels.Mixture of bones and wood ashes are used, together with clay, to create the cupels for cupellation.

The ability to work with bees'wax to create metal artifacts by the cire perdue (lost-wax) method of metal castings is clearly evidenced in Nahal Mishmar artifacts (5th millennium BCE).

![Image result]() Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)

Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)

http://www.aiarch.org.au/bios/cjd/147%20Davey%202009%20BUMA%20VI%20offprint.pdf

![]() Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.https://www.harappa.com/blog/mehrgarh-wheel-amulet-analysis-yields-many-secrets

Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.https://www.harappa.com/blog/mehrgarh-wheel-amulet-analysis-yields-many-secrets

![Image result for cire perdue lead weight shahi tump]() 3rd millennium BCE. Cire perdue technique used for leopard weight. Shahi Tump. H.16.7cm; dia.13.5cm; base dia 6cm; handle on top.The shell has been manufactured by lost-wax foundry of a copper alloy (12.6%b, 2.6%As), then it has been filled up through lead (99.5%) foundry.

3rd millennium BCE. Cire perdue technique used for leopard weight. Shahi Tump. H.16.7cm; dia.13.5cm; base dia 6cm; handle on top.The shell has been manufactured by lost-wax foundry of a copper alloy (12.6%b, 2.6%As), then it has been filled up through lead (99.5%) foundry.

Sayana/Wilson Trans.

1.119.09 That honey-seeking bee also murmured your praise; the son of Usij invokes you to the exhilaratin of Soma; you conciliated the mind of Dadhyãc, so that, provided with the head of a horse, he taught you (the mystic science).

1.119.10 Aśvins, you gave to Pedu the white (horse) desired by many, the breaker-through of combatants, shining, unconquerable by foes in battle, fit for every work; like Indra, the conquerer of men.

Griffith Trans.

RV 1.119.09 To you in praise of sweetness sang the honeybee-: Ausija calleth you in Soma's rapturous joy.

Ye drew unto yourselves the spirit of Dadhyãc, and then the horses' head uttered his words to you.RV 1.119.10 A horse did ye provide for Pedu, excellent, white, O ye Aśvins, conqueror of combatants,Invincible in war by arrows, seeking heaven worthy of fame, like Indra, vanquisher of men.

Ghassulian

Ghassulian refers to a culture and an archaeological stage dating to the Middle and Late Chalcolithic Period in the Southern Levant (c. 4400 – c. 3500 BC).[1] Its type-site, Teleilat Ghassul (Teleilat el-Ghassul, Tulaylat al-Ghassul), is located in the eastern Jordan Valley near the northern edge of the Dead Sea, in modern Jordan. It was excavated in 1929-1938 and in 1959-1960, by the Jesuits. [2][3][4] Basil Hennessy dug at the site in 1967 and in 1975-1977, and Stephen Bourke in 1994-1999.[1][5]

The Ghassulian stage was characterized by small hamlet settlements of mixed farming peoples, who had immigrated from the north and settled in the southern Levant - today's Jordan, Israel and Palestine. [3] People of the Beersheba Culture (a Ghassulian subculture) lived in underground dwellings - a unique phenomenon in the archaeological history of the region - or in houses that were trapezoid-shaped and built of mud-brick. Those were often built partially underground (on top of collapsed underground dwellings) and were covered with remarkable polychrome wall paintings. [3][6] Their pottery was highly elaborate, including footed bowls and horn-shaped drinking goblets, [3] indicating the cultivation of wine.[citation needed] Several samples display the use of sculptural decoration or of a reserved slip (a clay and water coating partially wiped away while still wet). [3] The Ghassulians were a Chalcolithic culture as they used stone tools but also smelted copper. [3][6] Funerary customs show evidence that they buried their dead in stone dolmens [7] and also practiced Secondary burial [6].

Settlements belonging to the Ghassulian culture have been identified at numerous other sites in what is today southern Israel, especially in the region of Beersheba, where elaborate underground dwellings have been excavated. The Ghassulian culture correlates closely with the Amratian of Egypt and also seems to have affinities (e.g., the distinctive churns, or “bird vases”) with early Minoan culture in Crete.[3][6]

Contents

Definition[edit]

Ghassulian, a name applied to a Chalcolithic culture of the southern Levant, is derived from the eponymic site of Teleilat (el) Ghassul, northeast of the Dead Sea in the Great Rift Valley. The name has been used as a synonym for Chalcolithic in general and sometimes for late phases, associated with late strata at that site and other sites considered to be contemporary. More recently it has come to be associated with a regional cultural phenomenon (defined by sets of artifacts) in what is today central and southern Israel, the Palestinian territories in the West Bank, and the central area of western Jordan; all either well-watered or semi-arid zones.[dubious ] Other phases of the Chalcolithic, associated with different regions of the Levant, are Qatifian and Timnian (arid zones) and Golanian. The use of the name varies from scholar to scholar.[citation needed]

Origins[edit]

The main culture of the Chalcolithic era in Israel is the Ghassulian culture, thus named after the name of its type-site, Teleilat el-Ghassul, located in the eastern part of the Jordan Rift Valley, opposite Jericho. Afterwards, many additional settlements, located in other archaeological sites, were identified as Ghassulian settlements. All these settlements had been built in areas that had not been previously inhabited, mainly on the outskirts of populated areas. Thus, Chalcolithic settlements have been discovered in the Jordan Rift Valley, in the Israeli coastal plain and on its fringes, in the Judaean Desert and in the northern and western Negev. On the other hand, it seems that people of the Chalcolithic period did not settle in the mountainous regions of Israel or in northern Israel. Several facts allow us to assume that the carriers of this culture were immigrants who had brought their own culture with them: all excavated sites represent an advanced stage of this culture, whereas no evidence of its nascent stages has been discovered, so far, anywhere in the region. This culture's characteristics indicate they had connections with neighboring regions and that their culture had not evolved in the southern Levant. Their origins are not known.[6][8]

It is hard to determine the time of the Ghassulian settlement in the region, and whether or not they had evolved out of local, pre-Ghassulian, populations (such as the Bsorian culture).[9] It could generally be said that most of these settlements date to the 2nd half of the 5th millennium BC, and that they usually existed for only a short period of time, with the exception of Teleilat el-Ghassul, where 8 successive layers of occupation from the Chalcolithic have been excavated, of which 6 are considered Ghassulian and the earlier, pre-Ghassulian, layers are thought to belong to the Besorian culture. The total depth of these layers is 4.5 meters.[6][8]

Ghassulian Copper Industry

The earliest evidence to the existence of a copper-industry in Israel was discovered in Bir abu Matar, Near Be'er Sheba, which specialized in copper production and the casting of copper tools and artifacts. No copper ore is naturally available in the area of Beersheba, so it appears that the ore was brought here from Wadi Feynan, in southern Jordan, and possibly also from Timna, where an ancient copper mine was discovered. It was attributed by Beno Rothenberg to the Chalcolithic era.[6]

Dates and transition phases