5 AUGUST, 2019 - 18:40 ED WHELAN

Earliest Writing System May Have Been Developed by Ancient Metalworkers 6,000 Years Ago

An Israeli academic has claimed to have found the earliest writing in the world. He claims that a proto-writing system was developed by ancient metalworkers over 6,000 years ago in the southern Levant. They belonged to the mysterious but very important Ghassulian culture.

An Israeli academic has claimed to have found the earliest writing in the world. He claims that a proto-writing system was developed by ancient metalworkers over 6,000 years ago in the southern Levant. They belonged to the mysterious but very important Ghassulian culture.Nissim Amzallag, who works at the Ben Gurion University and is an expert on the culture and origins of metalworking in the ancient world made the claim. He developed the theory after examining the famous hoard from Nahal Mishmar one of the most important archaeological discoveries from the Chalcolithic era, also known as the Copper Age. The Nahal Mishmar hoard was found in a cave in 1961 and is 6,300 years old.

The cache included hundreds of mace heads, scepters, and strange objects that are crown shaped. In total, some 421 objects were found. It is believed that they were secreted in the cave by priests from a nearby shrine, possibly during a time of danger, and they were never recovered.

Photo of discovery of Nahal Mishmar hoard in 1961. (Chamberi / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The Ghassulian Culture

The bronze objects were probably made by members of the Ghassulian culture. This was a very influential and sophisticated Copper Age culture in the ancient Levant who had trading links with Anatolia and the Caucasus. They developed a complex society and they had a high level of “craft specialization” and were experts at metalworking, according to the Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies .Amzallag, studied the objects, figures such as horned animals, geometric patterns and motifs, and concluded that they were symbolic. This is something shared by other experts who believe that the artifacts had some ceremonial or religious meaning. However, according to Haaretz he also argues that the “representations form a rudimentary three-dimensional code, in which each image symbolizes a word or phrase and communicates a certain concept”.

Discovered at Nahal Mishmar dozens of scepters and other objects made of copper. Do these represent an early writing system? (Nick Thompson / CC BY-SA 2.0 )

Early Writing System

The academics believe that the “Nahal Mishmar hoard should be seen as a precursor to the early writing systems that would emerge centuries later in Egypt and Mesopotamia” reports Haaretz. He believes the symbols were part of a secret code used by Ghassulian smiths. These metalworkers were very sophisticated for the time and had contacts with other cultures.

Amzallag analyzed several key pieces in particular and claims to have deciphered their symbols. These signifiers represented physical objects and are known as ‘ logograms’ and were the basis of later writing systems. In order to communicate complex ideas, the so-called rebus-principle was used by the Ghassulians. According to Haaretz, this principle used “a character, or phonogram, whose corresponding word sounds very similar to the complex idea that the writer is trying to communicate”.

Cooper items discovered at Nahal Mishmar. Researcher claims to have deciphered their symbols. (Matanya / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

The researchers believe that the many representations of horned animals are of ibex. Haaretz reports that the “West Semitic word used for young ungulates does sound very similar to the designation of ‘dust’ and ‘ore’”. This means that the representation of the horned animal was possibly related to how alloys were used and made. Amzallag also believes that there is a connection between birds and the early Semitic word for metalworking.

- Easy as Alep, Bet, Gimel? Cambridge Research Explores Social Context of Ancient Writing

- Oldest metal object found to date in Middle East

- Kharga Oasis spider rock art may be astronomical writing

The symbol of the horned ibex was possibly related to how alloys were used and made. (Teacoolish / CC BY-SA 3.0 )

A Secret Code Used by Metalworkers

The reason for the development of this script was based on the needs of the metalworkers. All of the symbols signify some aspect of working with copper and bronze. The smith's craft was one that was considered almost magical and their skills would have been closely guarded.

They probably developed the script so that they could share their secrets and instruct other smiths, without divulging them to the general population and to other groups. The writing was a secret code that was known only to the Ghassulian smiths and metalworkers.

However, there has been considerable pushback against this theory. Firstly, it is not known if the Ghassulians, spoke a Semitic language and secondly it is notoriously difficult to interpret ancient symbols and iconography. Then there is the argument that the symbols are only decorative.

It is generally agreed that the first systematic writing systems were developed in Egypt and Mesopotamia around 3,200 BC. However, the academic believes that the Ghassulians helped to develop the ‘rebus principle’ and this was a critical contribution to writing and its development. If the interpretation of the bronze objects is correct the Ghassulian may have developed an important proto-writing system that played a crucial part in the development of literacy in the ancient Near East.

Top image: Bronze scepter from the Nahal Mishmar. Source: Poliocretes / CC BY-SA 3.0 .

By Ed Whelan

https://www.ancient-origins.net/news-history-archaeology/writing-system-0012398https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QSm1VuPlndI (0:57)

6000 year old Copper-Bronze tools from Nahal Mishmar Judean Desert Israel

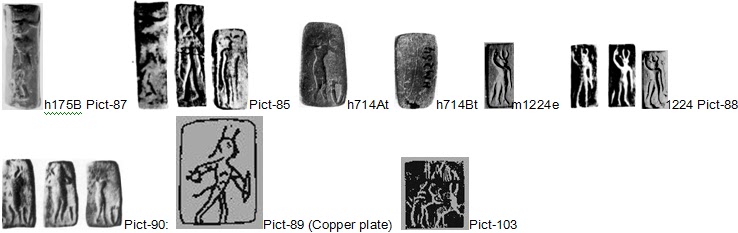

Ancient Near East Indus Script bull-man dhangra 'bull' with ḍã̄g 'mace' is ḍāṅro, ṭhākur ʻblacksmithʼ. 240 Nahal Mishmar maceheads signify guild of blacksmiths

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/huogrgr

Out of 442 artifacts discovered in Nahal Mishmar, 240 are maceheads. These should signify the major preoccupation of the people who left the artifacts in Nahal Mishmar. This is suggested because, a mace held in a person's hand on ancient sculptural friezes signifies his or her profession -- smithy.

I posit that the maceheads are a signature tune of a guild of blacksmiths of the Bronze Age, giving meaning to the phrase: harosheth hagoyim 'smithy of nations'. (Book of Judges 5:10).

In RV 3.53.12, Rishi Visvamitra states that this mantra (brahma) shall protect the people: visvamitrasya rakshati brahmedam Bhāratam Janam.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/11/tracing-roots-of-bharatam-janam-from.html Rishi http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/bharatam-janam-of-rigveda-rv-353-mean.html

The word Bharata in the expression of identification by Visvamitra is derived from the metalwork lexis of Prakritam: ‘bhārata ‘a factitious alloy of copper, pewter, tin’; baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin)’. Thus, the expression Bhāratam Janam can be described semantically as ‘metalcaster folk’, thus firmly establishing the identity of the people of India, that is Bharat and the spoken form of their language ca. 3500 BCE.

This monograph tests the hypothesis to demonstrate that a person holding a mace in ancient Bronze Age signifies a blacksmith, a metalworker.

![Baked clay plaque showing a bull-man holding a post.]()

On this terracotta plaque, the mace is a phonetic determinant of the bovine (bull) ligatured to the body of the person holding the mace. The person signified is: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ "... head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull...Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. British Museum. WCO2652. Bull-manTerracotta plaque. Bull-man holding a post. Mesopotamia, ca. 2000-1600 BCE."

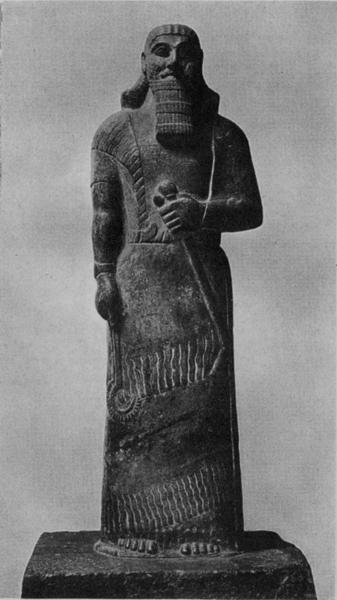

![]() Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II, in 883 BCE carries a mace/

Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II, in 883 BCE carries a mace/

![]() Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE), son of Ashurbanipal II carries a mace

Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE), son of Ashurbanipal II carries a mace

![Stele of Ashurnasirpal II. Neo-Assyrian, 883-859 BCE. Now in the British Museum:]() British Museum. Stele of Ashurnasirpal II. Neo-Assyrian, 883-859 BCE

British Museum. Stele of Ashurnasirpal II. Neo-Assyrian, 883-859 BCE

![]()

![Image result for tukulti mace]()

![]() Unprovenienced. Person with a mace.

Unprovenienced. Person with a mace.

![]() Bactria Margiana. Bronze macehead with snake hieroglyph

Bactria Margiana. Bronze macehead with snake hieroglyph

![]()

Bronze knobbed mace - Balkan Peninsula, Macedonia. Near East Bronze age: 3,300 - 1,200 BC. 4 cm tall x 6.5 cm wide.

![Plaster cast of a Neo-Hittite relief; soldier or guardsman walking right with mace, long sword and spear; painted black in imitation of original basalt; mounted in wooden frame. Culture/period: Neo-Hittite - 10thC BC:]()

![]() upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws. Does he carry a mace?

upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws. Does he carry a mace?![]() tela of Adad-Nirari III carries a mace (809-782 BCE) Tell El-Rimah

tela of Adad-Nirari III carries a mace (809-782 BCE) Tell El-Rimah![]() Maceheads. Votive?

Maceheads. Votive?

![Image result for tukulti mace]() The person accompanying Tukulti Ninurta I who kneels in front of the fire-altar carries a mace. The entire frame is flanked by two safflowers.

The person accompanying Tukulti Ninurta I who kneels in front of the fire-altar carries a mace. The entire frame is flanked by two safflowers.

In the orthographic tradition of Ancient Near East, a professional is signified by the hieroglyph he or she carries. Thus, a coppersmith, seafaring merchant carries a goat proclaiming that he works with mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu 'copper' (See cylinder seal with cuneiform Akkadian of Shu-ilishu)

![Image result for shu ilishu]() Shu-ilishu cylinder seal of eme-bal, interpreter. Akkadian. Cylinder seal Impression. Inscription records that it belongs to ‘S’u-ilis’u, Meluhha interpreter’, i.e., translator of the Meluhhan language (EME.BAL.ME.LUH.HA.KI) The Meluhhan being introduced carries an goat on his arm. Musee du Louvre. Ao 22 310, Collection De Clercq 3rd millennium BCE. The Meluhhan is accompanied by a lady carrying a kamaṇḍalu. The goat on the trader's hand is a phonetic determinant -- that he is Meluhha. This is decrypted based on the word for the goat: mlekh 'goat' (Brahui); mr..eka 'goat' (Telugu) Rebus: mleccha'copper' (Samskritam); milakkhu 'copper' (Pali) Thus the sea-faring merchant carrying the goat is a copper (and tin) trader from Meluhha. The jar carried by the accompanying person is a liquid measure:ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. A hieroglyph used to denote ranku may be seen on the two pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck in Haifa. That Pali uses the term ‘milakkhu’ is significant (cf. Uttarādhyayana Sūtra 10.16) and reinforces the concordance between ‘mleccha’ and ‘milakkhu’ (a pronunciation variant) and links the language with ‘meluhha’ as a reference to a language in Mesopotamian texts and in the cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu. [Possehl, Gregory, 2006, Shu-ilishu’s cylinder seal, Expedition, Vol. 48, No. 1http://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/48-1/What%20in%20the%20World.pdf] This seal shows a sea-faring Meluhha merchant who needed a translator to translate meluhha speech into Akkadian. The translator’s name was Shu-ilishu as recorded in cuneiform script on the seal. This evidence rules out Akkadian as the Indus or Meluhha language and justifies the search for the proto-Indian speech from the region of the Sarasvati river basin which accounts for 80% (about 2000) archaeological sites of the civilization, including sites which have yielded inscribed objects such as Lothal, Dwaraka, Kanmer, Dholavira, Surkotada, Kalibangan, Farmana, Bhirrana, Kunal, Banawali, Chandigarh, Rupar, Rakhigarhi. The language-speakers in this basin are likely to have retained cultural memories of Indus language which can be gleaned from the semantic clusters of glosses of the ancient versions of their current lingua francaavailable in comparative lexicons and nighanṭu-s. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/04/ox-hide-ingots-of-tin-and-one-third.html

Shu-ilishu cylinder seal of eme-bal, interpreter. Akkadian. Cylinder seal Impression. Inscription records that it belongs to ‘S’u-ilis’u, Meluhha interpreter’, i.e., translator of the Meluhhan language (EME.BAL.ME.LUH.HA.KI) The Meluhhan being introduced carries an goat on his arm. Musee du Louvre. Ao 22 310, Collection De Clercq 3rd millennium BCE. The Meluhhan is accompanied by a lady carrying a kamaṇḍalu. The goat on the trader's hand is a phonetic determinant -- that he is Meluhha. This is decrypted based on the word for the goat: mlekh 'goat' (Brahui); mr..eka 'goat' (Telugu) Rebus: mleccha'copper' (Samskritam); milakkhu 'copper' (Pali) Thus the sea-faring merchant carrying the goat is a copper (and tin) trader from Meluhha. The jar carried by the accompanying person is a liquid measure:ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. A hieroglyph used to denote ranku may be seen on the two pure tin ingots found in a shipwreck in Haifa. That Pali uses the term ‘milakkhu’ is significant (cf. Uttarādhyayana Sūtra 10.16) and reinforces the concordance between ‘mleccha’ and ‘milakkhu’ (a pronunciation variant) and links the language with ‘meluhha’ as a reference to a language in Mesopotamian texts and in the cylinder seal of Shu-ilishu. [Possehl, Gregory, 2006, Shu-ilishu’s cylinder seal, Expedition, Vol. 48, No. 1http://www.penn.museum/documents/publications/expedition/PDFs/48-1/What%20in%20the%20World.pdf] This seal shows a sea-faring Meluhha merchant who needed a translator to translate meluhha speech into Akkadian. The translator’s name was Shu-ilishu as recorded in cuneiform script on the seal. This evidence rules out Akkadian as the Indus or Meluhha language and justifies the search for the proto-Indian speech from the region of the Sarasvati river basin which accounts for 80% (about 2000) archaeological sites of the civilization, including sites which have yielded inscribed objects such as Lothal, Dwaraka, Kanmer, Dholavira, Surkotada, Kalibangan, Farmana, Bhirrana, Kunal, Banawali, Chandigarh, Rupar, Rakhigarhi. The language-speakers in this basin are likely to have retained cultural memories of Indus language which can be gleaned from the semantic clusters of glosses of the ancient versions of their current lingua francaavailable in comparative lexicons and nighanṭu-s. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/04/ox-hide-ingots-of-tin-and-one-third.html

![]()

![]()

![]() Three-faced person with armlets, bracelets seated on a stool with bovine legs. Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050

Three-faced person with armlets, bracelets seated on a stool with bovine legs. Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050

Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.296 Mackay 1938: 335, pl. LXXXVII, 222 ![]()

![]()

Procession of Elamite warriors, Susa, Iran, Elamit c. 1150 BCE Bronze relief, Louvre, Paris

![]()

![]() A person is a standard bearer of a banner holding aloft the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Indus writing. The banner is comparable to the banner shown on two Mohenjo-daro tablets.

A person is a standard bearer of a banner holding aloft the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Indus writing. The banner is comparable to the banner shown on two Mohenjo-daro tablets.

https://tinyurl.com/ybd3lyux

R̥gveda 1.119.9, 10 speaks of the 'mystic science' of using mākṣikā, bees' and Dadhyãc bones. I suggest that this is a pun on the word: Hieroglyph: माक्षिक [p= 805,2] mfn. (fr. मक्षिका mākṣikā) coming from or belonging to a bee Ma1rkP. Rebus: माक्षिक n. a kind of honey-like mineral substance or pyrites MBh.

The metaphor used in R̥gveda 1.119.9 to produce madhu, i.e. Soma is a reference to use of pyrites to produce electrum Soma which is also referred to in R̥gveda as amśu cognate ancu 'iron' (Tocharian) अंशु [p= 1,1] a kind of सोम libation S3Br. (Monier-Williams)

I suggest that the references to pyrites and horse bones (of Dadhyãc) in RV 1.119.9 is a narrative of metallurgical process of cupellation to remove lead ores from pyrite ores --मक्षिका mākṣikā-- to realize pure metals such as gold, silver or copper.

Many conjectures have been made on the role of the horse bones of Dadhyãc in Soma processing. I suggest that the use of bones is for cupellation process to oxidise lead iin pyrites, as 'litharge cakes of lead monoxide', thus removing lead from the mineral ores. A cupel which resembles a small egg cup, is made of ceramic or bone ash which was used to separate base metals from noble metals -- to separate noble metals, like gold and silver, from base metals like lead, copper, zinc, arsenic, antimony or bismuth, present in the ore. "The base of the hearth was dug in the form of a saucepan, and covered with an inert and porous material rich in calcium or magnesium such as shells, lime, or bone ash.The lining had to be calcareous because lead reacts with silica (clay compounds) to form viscous lead silicate that prevents the needed absorption of litharge, whereas calcareous materials do not react with lead.[7]Some of the litharge evaporates, and the rest is absorbed by the porous earth lining to form "litharge cakes".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cupellation

![]() Brass moulds for making cupels.Mixture of bones and wood ashes are used, together with clay, to create the cupels for cupellation.

Brass moulds for making cupels.Mixture of bones and wood ashes are used, together with clay, to create the cupels for cupellation.

The ability to work with bees'wax to create metal artifacts by the cire perdue (lost-wax) method of metal castings is clearly evidenced in Nahal Mishmar artifacts (5th millennium BCE).

![Image result]() Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)

Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)

http://www.aiarch.org.au/bios/cjd/147%20Davey%202009%20BUMA%20VI%20offprint.pdf

![]() Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.https://www.harappa.com/blog/mehrgarh-wheel-amulet-analysis-yields-many-secrets

Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.https://www.harappa.com/blog/mehrgarh-wheel-amulet-analysis-yields-many-secrets

![Image result for cire perdue lead weight shahi tump]() 3rd millennium BCE. Cire perdue technique used for leopard weight. Shahi Tump. H.16.7cm; dia.13.5cm; base dia 6cm; handle on top.The shell has been manufactured by lost-wax foundry of a copper alloy (12.6%b, 2.6%As), then it has been filled up through lead (99.5%) foundry.

3rd millennium BCE. Cire perdue technique used for leopard weight. Shahi Tump. H.16.7cm; dia.13.5cm; base dia 6cm; handle on top.The shell has been manufactured by lost-wax foundry of a copper alloy (12.6%b, 2.6%As), then it has been filled up through lead (99.5%) foundry.

Sayana/Wilson Trans.

1.119.09 That honey-seeking bee also murmured your praise; the son of Usij invokes you to the exhilaratin of Soma; you conciliated the mind of Dadhyãc, so that, provided with the head of a horse, he taught you (the mystic science).

1.119.10 Aśvins, you gave to Pedu the white (horse) desired by many, the breaker-through of combatants, shining, unconquerable by foes in battle, fit for every work; like Indra, the conquerer of men.

Griffith Trans.

RV 1.119.09 To you in praise of sweetness sang the honeybee-: Ausija calleth you in Soma's rapturous joy.

Ye drew unto yourselves the spirit of Dadhyãc, and then the horses' head uttered his words to you.

Out of 442 artifacts discovered in Nahal Mishmar, 240 are maceheads. These should signify the major preoccupation of the people who left the artifacts in Nahal Mishmar. This is suggested because, a mace held in a person's hand on ancient sculptural friezes signifies his or her profession -- smithy.

I posit that the maceheads are a signature tune of a guild of blacksmiths of the Bronze Age, giving meaning to the phrase: harosheth hagoyim 'smithy of nations'. (Book of Judges 5:10).

In RV 3.53.12, Rishi Visvamitra states that this mantra (brahma) shall protect the people: visvamitrasya rakshati brahmedam Bhāratam Janam.

Translation: 3.053.12 I have made Indra glorified by these two, heaven and earth, and this prayer of Vis'va_mitra protects the people (janam) of Bharata. [Made Indra glorified: indram atus.t.avam-- the verb is the third preterite of the casual, I have caused to be praised; it may mean: I praise Indra, abiding between heaven and earth, i.e. in the firmament].

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/11/tracing-roots-of-bharatam-janam-from.html Rishi http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/bharatam-janam-of-rigveda-rv-353-mean.html

The word Bharata in the expression of identification by Visvamitra is derived from the metalwork lexis of Prakritam: ‘bhārata ‘a factitious alloy of copper, pewter, tin’; baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin)’. Thus, the expression Bhāratam Janam can be described semantically as ‘metalcaster folk’, thus firmly establishing the identity of the people of India, that is Bharat and the spoken form of their language ca. 3500 BCE.

This monograph tests the hypothesis to demonstrate that a person holding a mace in ancient Bronze Age signifies a blacksmith, a metalworker.

British Museum number103225 Baked clay plaque showing a bull-man holding a post.

Old Babylonian 2000BC-1600BCE Length: 12.8 centimetres Width: 7 centimetres Barcelona 2002 cat.181, p.212 BM Return 1911 p. 66On this terracotta plaque, the mace is a phonetic determinant of the bovine (bull) ligatured to the body of the person holding the mace. The person signified is: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ "... head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull...Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. British Museum. WCO2652. Bull-manTerracotta plaque. Bull-man holding a post. Mesopotamia, ca. 2000-1600 BCE."

Terracotta. This plaque depicts a creature with the head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull. Though similar figures are depicted earlier in Iran, they are first seen in Mesopotamian art around 2500 BC, most commonly on cylinder seals, and are associated with the sun-god Shamash. The bull-man was usually shown in profile, with a single visible horn projecting forward. However, here he is depicted in a less common form; his whole body above the waist, shown in frontal view, shows that he was intended to be double-horned. He may be supporting a divine emblem and thus acting as a protective deity.

Old Babylonian, about 2000-1600 BCE From Mesopotamia Length: 12.8 cm Width: 7cm ME 103225 Room 56: Mesopotamia Briish Museum

Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. While many show informal scenes and reflect the private face of life, this example clearly has magical or religious significance.

Hieroglyph carried on a flagpost by the blacksmith (bull ligatured man: Dhangar 'bull' Rebus: blacksmith')

Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II, in 883 BCE carries a mace/

Ashurnasirpal II succeeded his father, Tukulti-Ninurta II, in 883 BCE carries a mace/ Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE), son of Ashurbanipal II carries a mace

Shalmaneser III (859–824 BCE), son of Ashurbanipal II carries a mace British Museum. Stele of Ashurnasirpal II. Neo-Assyrian, 883-859 BCE

British Museum. Stele of Ashurnasirpal II. Neo-Assyrian, 883-859 BCEAssyrian reliefs show persons with maces. Remarks about Some Assyrian Reliefs E. Porada Anatolian Studies

Vol. 33, Special Number in Honour of the Seventy-Fifth Birthday of Dr. Richard Barnett (1983), pp. 15-18

Unprovenienced. Person with a mace.

Unprovenienced. Person with a mace. Bactria Margiana. Bronze macehead with snake hieroglyph

Bactria Margiana. Bronze macehead with snake hieroglyph

Bronze knobbed mace - Balkan Peninsula, Macedonia. Near East Bronze age: 3,300 - 1,200 BC. 4 cm tall x 6.5 cm wide.

laster cast of a Neo-Hittite relief; soldier or guardsman walking right with mace, long sword and spear; painted black in imitation of original basalt; mounted in wooden frame. Culture/period: Neo-Hittite - 10thC BCE![An Assyrian soldier waving a mace escorts four prisoners, who carry their possessions in sacks over their shoulders. Their clothes and their turbans, rising to a slight point which flops backwards, are typical of the area; people from the Biblical kingdom of Israel, shown on other sculptures, wear the same dress, gypsum wall panel relief, South West Palace, Nimrud, Kalhu Iraq, neo-assyrian, 730BC-727BC:]() British Museum. An Assyrian soldier waving a mace escorts four prisoners, who carry their possessions in sacks over their shoulders. Their clothes and their turbans, rising to a slight point which flops backwards, are typical of the area; people from the Biblical kingdom of Israel, shown on other sculptures, wear the same dress, gypsum wall panel relief, South West Palace, Nimrud, Kalhu Iraq, neo-assyrian, 730BC-727BCE

British Museum. An Assyrian soldier waving a mace escorts four prisoners, who carry their possessions in sacks over their shoulders. Their clothes and their turbans, rising to a slight point which flops backwards, are typical of the area; people from the Biblical kingdom of Israel, shown on other sculptures, wear the same dress, gypsum wall panel relief, South West Palace, Nimrud, Kalhu Iraq, neo-assyrian, 730BC-727BCE

upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws. Does he carry a mace?

upper part of the stele of Hammurabi's code of laws. Does he carry a mace? tela of Adad-Nirari III carries a mace (809-782 BCE) Tell El-Rimah

tela of Adad-Nirari III carries a mace (809-782 BCE) Tell El-Rimah Maceheads. Votive?

Maceheads. Votive?![]() Anzu depicted on a stone macehead from the mid-third millennium BCE

Anzu depicted on a stone macehead from the mid-third millennium BCE

![]() Mace Ti kulti Ninurta Louvre AO 2152.

Mace Ti kulti Ninurta Louvre AO 2152.

In the orthographic tradition of Ancient Near East, a professional is signified by the hieroglyph he or she carries. Thus, a coppersmith, seafaring merchant carries a goat proclaiming that he works with mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu 'copper' (See cylinder seal with cuneiform Akkadian of Shu-ilishu)

Gods, caves, and scholars: Chalcolithic Cult and Metallurgy in the Judean Desert by Yuval Goren Near Eastern Archaeology Vol. 77, No. 4 (December 2014), pp. 260-266Published by: The American Schools of Oriental Research http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5615/neareastarch.77.4.0260

Gods, caves, and scholars: Chalcolithic Cult and Metallurgy in the Judean Desert by Yuval Goren Near Eastern Archaeology Vol. 77, No. 4 (December 2014), pp. 260-266Published by: The American Schools of Oriental Research http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5615/neareastarch.77.4.0260

240 maceheads of Nahal Mishmar are indicative of the widely prevalent name for a blacksmith of the Harosheth Hagoyim. If taken in a procession on flagposts, these would have recollected the memories of the metalsmiths of yore and paying respects to the memories of ancestors. Hieroglyph: ḍã̄g m. ʻ club, mace ʼ(Kashmiri) Rebus: K. ḍangur (dat. °garas) m. ʻ fool ʼ; P. ḍaṅgar m. ʻ stupid man ʼ; N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ, ḍāṅre ʻ large and lazy ʼ; A.ḍaṅurā ʻ living alone without wife or children ʼ; H. ḍã̄gar, ḍã̄grā m. ʻ starveling ʼ.N. ḍiṅgar ʻ contemptuous term for an inhabitant of the Tarai ʼ; B. ḍiṅgar ʻ vile ʼ; Or. ḍiṅgara ʻ rogue ʼ, °rā ʻ wicked ʼ; H. ḍiṅgar m. ʻ rogue ʼ; M. ḍĩgar m. ʻ boy ʼ.(CDIAL 5524)I ډانګ ḏḏāng, s.m. (2nd) A club, a stick, a bludgeon. Pl. ډانګونه ḏḏāngūnah. ډانګ لکئِي ḏḏāng lakaʿī, s.f. (6th) The name of a bird with a club-tail. Sing. and Pl. See توره آنا ډانګورئِي ḏḏāngoraʿī, s.f. (6th) A small walking- stick, a small club. Sing. and Pl. (The dimin. of the above). (Pashto) ḍã̄g डाँग् । स्थूलदण्डः m. a club, mace (Gr.Gr. 1); a blow with a stick or cudgel (Śiv. 13); a walking-stick. Cf. ḍã̄guvu. -- dini -- दिनि &below; । ताडनम् m. pl. inf. to give clubs; to give a drubbing, to flog a person as a punishment. (Kashmiri) ḍakka2 ʻ stick ʼ. 2. *ḍaṅga -- 1 . [Cf. other variants for ʻ stick ʼ: ṭaṅka -- 3 , *ṭiṅkara -- , *ṭhiṅga -- 1 , *ḍikka -- 1 (*ḍiṅka -- )]1. S. ḍ̠aku m. ʻ stick put up to keep a door shut ʼ, ḍ̠akaru ʻ stick, straw ʼ; P. ḍakkā m. ʻ straw ʼ, ḍakkrā m. ʻ bit (of anything) ʼ; N. ḍã̄klo ʻ stalk, stem ʼ.2. Pk. ḍaṅgā -- f. ʻ stick ʼ; A. ḍāṅ ʻ thick stick ʼ; B. ḍāṅ ʻ pole for hanging things on ʼ; Or. ḍāṅga ʻ stick ʼ; H. ḍã̄g f. ʻ club ʼ (→ P. ḍã̄g f. ʻ stick ʼ; K. ḍã̄g m. ʻ club, mace ʼ); G. ḍã̄g f., °gɔ,ḍãgorɔ m., °rũ n. ʻ stick ʼ; M. ḍãgarṇẽ n. ʻ short thick stick ʼ, ḍã̄gḷī f. ʻ small branch ʼ, ḍã̄gśī f.Addenda: *ḍakka -- 2 . 2. *ḍaṅga -- 1 : WPah.kṭg. ḍāṅg f. (obl. -- a) ʻ stick ʼ, ḍaṅgṛɔ m. ʻ stalk (of a plant) ʼ; -- poss. kṭg. (kc.) ḍaṅgrɔ m. ʻ axe ʼ, poet. ḍaṅgru m., °re f.; J. ḍã̄grā m. ʻ small weapon like axe ʼ, P. ḍaṅgorī f. ʻ small staff or club ʼ (Him.I 84).(CDIAL 6520)Allograph Hieroglyph: ḍhaṅgaru, ḍhiṅgaru m. ʻlean emaciated beastʼ(Sindhi)

Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ S. ḍhaṅgaru m. ʻ lean emaciated beast ʼ ; L. (Shahpur) ḍhag̠g̠ā ʻ small weak ox ʼ(CDIAL 5324)

240 maceheads of Nahal Mishmar are indicative of the widely prevalent name for a blacksmith of the Harosheth Hagoyim. If taken in a procession on flagposts, these would have recollected the memories of the metalsmiths of yore and paying respects to the memories of ancestors. Hieroglyph: ḍã̄g m. ʻ club, mace ʼ(Kashmiri) Rebus: K. ḍangur (dat. °garas) m. ʻ fool ʼ; P. ḍaṅgar m. ʻ stupid man ʼ; N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ, ḍāṅre ʻ large and lazy ʼ; A.ḍaṅurā ʻ living alone without wife or children ʼ; H. ḍã̄gar, ḍã̄grā m. ʻ starveling ʼ.N. ḍiṅgar ʻ contemptuous term for an inhabitant of the Tarai ʼ; B. ḍiṅgar ʻ vile ʼ; Or. ḍiṅgara ʻ rogue ʼ, °rā ʻ wicked ʼ; H. ḍiṅgar m. ʻ rogue ʼ; M. ḍĩgar m. ʻ boy ʼ.(CDIAL 5524)

I ډانګ ḏḏāng, s.m. (2nd) A club, a stick, a bludgeon. Pl. ډانګونه ḏḏāngūnah. ډانګ لکئِي ḏḏāng lakaʿī, s.f. (6th) The name of a bird with a club-tail. Sing. and Pl. See توره آنا ډانګورئِي ḏḏāngoraʿī, s.f. (6th) A small walking- stick, a small club. Sing. and Pl. (The dimin. of the above). (Pashto) ḍã̄g डाँग् । स्थूलदण्डः m. a club, mace (Gr.Gr. 1); a blow with a stick or cudgel (Śiv. 13); a walking-stick. Cf. ḍã̄guvu. -- dini -- दिनि &below; । ताडनम् m. pl. inf. to give clubs; to give a drubbing, to flog a person as a punishment. (Kashmiri) ḍakka2 ʻ stick ʼ. 2. *ḍaṅga -- 1 . [Cf. other variants for ʻ stick ʼ: ṭaṅka -- 3 , *ṭiṅkara -- , *ṭhiṅga -- 1 , *ḍikka -- 1 (*ḍiṅka -- )]1. S. ḍ̠aku m. ʻ stick put up to keep a door shut ʼ, ḍ̠akaru ʻ stick, straw ʼ; P. ḍakkā m. ʻ straw ʼ, ḍakkrā m. ʻ bit (of anything) ʼ; N. ḍã̄klo ʻ stalk, stem ʼ.2. Pk. ḍaṅgā -- f. ʻ stick ʼ; A. ḍāṅ ʻ thick stick ʼ; B. ḍāṅ ʻ pole for hanging things on ʼ; Or. ḍāṅga ʻ stick ʼ; H. ḍã̄g f. ʻ club ʼ (→ P. ḍã̄g f. ʻ stick ʼ; K. ḍã̄g m. ʻ club, mace ʼ); G. ḍã̄g f., °gɔ,ḍãgorɔ m., °rũ n. ʻ stick ʼ; M. ḍãgarṇẽ n. ʻ short thick stick ʼ, ḍã̄gḷī f. ʻ small branch ʼ, ḍã̄gśī f.Addenda: *ḍakka -- 2 . 2. *ḍaṅga -- 1 : WPah.kṭg. ḍāṅg f. (obl. -- a) ʻ stick ʼ, ḍaṅgṛɔ m. ʻ stalk (of a plant) ʼ; -- poss. kṭg. (kc.) ḍaṅgrɔ m. ʻ axe ʼ, poet. ḍaṅgru m., °re f.; J. ḍã̄grā m. ʻ small weapon like axe ʼ, P. ḍaṅgorī f. ʻ small staff or club ʼ (Him.I 84).(CDIAL 6520)

Allograph Hieroglyph: ḍhaṅgaru, ḍhiṅgaru m. ʻlean emaciated beastʼ(Sindhi)

Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ S. ḍhaṅgaru m. ʻ lean emaciated beast ʼ ; L. (Shahpur) ḍhag̠g̠ā ʻ small weak ox ʼ(CDIAL 5324)

Plaque de pierre en relief illustrant une scène de banquet, les préparatifs et les divertissements, Khafajeh, époque dynastique archaïque II – III A (ca. 2700 – 2600 av. J.-C.), 20,4 x 20 x 4,2 cm. "Plaques such as this were part of a door-locking system for important buildings. The plaque was embedded in the doorjamb and a peg, inserted into the central perforation, was used to hold a hook or cord that secured the door and was covered with clay impressed by one or more seals." https://oi.uchicago.edu/collections/highlights/highlights-collection-mesopotamia The bottom register shows a harp player. Rightmost is a person perhaps carrying a mace. The harp is a hieroglyph: tambura 'harp'; rebus: tambra 'copper'.The mace carrying person is a blacksmith; rebus reading: ḍã̄g m. ʻ club, mace ʼ(Kashmiri) Rebus: K. ḍangur (dat. °garas) m. ʻ fool ʼ; P. ḍaṅgar m. ʻ stupid man ʼ; N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ, ḍāṅre ʻ large and lazy ʼ; A.ḍaṅurā ʻ living alone without wife or children ʼ; H. ḍã̄gar, ḍã̄grā m. ʻ starveling ʼ.N. ḍiṅgar ʻ contemptuous term for an inhabitant of the Tarai ʼ; B. ḍiṅgar ʻ vile ʼ; Or. ḍiṅgara ʻ rogue ʼ, °rā ʻ wicked ʼ; H. ḍiṅgar m. ʻ rogue ʼ; M. ḍĩgar m. ʻ boy ʼ.(CDIAL 5524)

Three-faced person with armlets, bracelets seated on a stool with bovine legs. Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050

Three-faced person with armlets, bracelets seated on a stool with bovine legs. Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050Hieroglyph: kamaḍha ‘penance’ (Pkt.) Rebus 1: kampaṭṭa ‘mint’ (Ma.) kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.);Rebus 2: kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar' (Santali); kan ‘copper’ (Ta.)

Hieroglyph: karã̄ n. pl. ʻwristlets, bangles ʼ (Gujarati); kara 'hand' (Rigveda) Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

The bunch of twigs = ku_di_, ku_t.i_ (Skt.lex.) ku_di_ (also written as ku_t.i_ in manuscripts) occurs in the Atharvaveda (AV 5.19.12) and Kaus’ika Su_tra (Bloomsfield’s ed.n, xliv. cf. Bloomsfield, American Journal of Philology, 11, 355; 12,416; Roth, Festgruss an Bohtlingk,98) denotes it as a twig. This is identified as that of Badari_, the jujube tied to the body of the dead to efface their traces. (See Vedic Index, I, p. 177).[Note the twig adoring the head-dress of a horned, standing person]

Procession of Elamite warriors, Susa, Iran, Elamit c. 1150 BCE Bronze relief, Louvre, Paris

- Frise d'un panneau de mosaïqueVers 2500 - 2400 avant J.-C.Mari, temple d'Ishtar

- Coquille, schiste

- Fouilles Parrot, 1934 - 1936AO 19820

- Richelieu wing

Ground floor

Ancient Mesopotamia

Room 1 b

Vitrine 7 : Epoque des dynasties archaïques de Sumer, vers 2900 - 2340 avant J.-C. Antiquités de Mari (Moyen-Euphrate) - Life of Mari, Frise d'un panneau de mosaïque.

A person is a standard bearer of a banner holding aloft the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Indus writing. The banner is comparable to the banner shown on two Mohenjo-daro tablets.

A person is a standard bearer of a banner holding aloft the one-horned young bull which is the signature glyph of Indus writing. The banner is comparable to the banner shown on two Mohenjo-daro tablets. Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820

These inlaid mosaics, composed of figures carved in mother-of-pearl, against a background of small blocks of lapis lazuli or pink limestone, set in bitumen, are among the most original and attractive examples of Mesopotamian art. It was at Mari that a large number of these mosaic pieces were discovered. Here they depict a victory scene: soldiers lead defeated enemy captives, naked and in chains, before four dignitaries....The leader appears to be a shaven-headed figure: stripped to the waist and wearing kaunakes, he carries a standard showing a bull standing on a pedestal. The lower register, on the right, features traces of a chariot drawn by onagers, a type of wild ass.

Bibliography

Contenau G., Manuel d'archéologie orientale depuis les origines jusqu'à Alexandre : les découvertes archéologiques de 1930 à 1939, IV, Paris : Picard, 1947, pp. 2049-2051, fig. 1138

Parrot A., Les fouilles de Mari, première campagne (hiver 1933-1934), Extr. de : Syria, 16, 1935, paris : P. Geuthner, pp. 132-137, pl. XXVIII

Parrot A., Mission archéologique de Mari : vol. I : le temple d'Ishtar, Bibliothèque archéologique et historique, LXV, Paris : Institut français d'archéologie du Proche-Orient, 1956, pp. 136-155, pls. LVI-LVII Author: Iselin Claire

See:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-bronze-age-legacy_6.html Ancient Near East bronze-age legacy: Processions depicted on Narmer palette, Indus writing denote artisan guilds

21 plates of ḍaṅgorī 'mace, club' including maceheads of 9 millennia upto the 1st millennium.

Images selected and compiled by Michael Serbane in his doctoral thesis under the supervision of Prof. Benjamin Sass of Tel Aviv University on ‘The Mace in Israel and the Ancient Near East from the Ninth millennium to the First – Typology and chronology, technology, military and ceremonial use, regional interconnections’ (2009). Linked and excerpts circulated with blogpost:

![]() This figure presented by Dr. Michael Serbane evokes the imagery of a Soma Yaga Yupa with a caSAla.The figure on the top row with a safflower ligature is significant. I siggest that the safflower signified all over Ancient Near East and the Levant, करडी [ karaḍī ] f (

This figure presented by Dr. Michael Serbane evokes the imagery of a Soma Yaga Yupa with a caSAla.The figure on the top row with a safflower ligature is significant. I siggest that the safflower signified all over Ancient Near East and the Levant, करडी [ karaḍī ] f (

If carried on processions, these standards or flagposts are comparable to the procession shown on two Mohenjo-daro tablets as proclamations of metallurgical competence.

Nahal Mishmar evidence of cire perdue metal casting, R̥gveda evidence of cupellation of mākṣika 'pyrites' to gain amśu, ancu 'iron' in Ancient Pyrotechnology

https://tinyurl.com/ybd3lyux

See:

Gobekli Tepe pictograms signify heat treatment of mineral stones in Ancient Pyrotechnology; a hypothesis posited from Indus Script hypertexts https://tinyurl.

Gobekli Tepe (12k ya) and Nahal Mishmar (8k ya) Indus Scrript hypertexts relate to Ancient pyrotechnology https://tinyurl.com/y8ly57kh

Did the metallurgical techniques (in Ancient Pyrotechnology) of Gobekli Tepe artisans include cire perdue techniques and cupellation?

Some evidences from Nahal Mishmar artifacts and R̥gveda texts are discussed in this monograph. Both categories of evidence may be relevant to identify or hypothesise on techniques of Ancient Pyrotechnology of Gobekli Tepe Pre-pottery neolithic period (ca. 10th millennium BCE).

NahalMishmar evidences of cire perdue metal casting artifacts are dated to 6th millennium BCE. R̥gveda textual evidences relate to metalworking processes of a period earlier than 7th millennium BCE. This note claims that aspects of metalwork related to Ancient Pyrotechnology are: 1 cire perdue technique of metal casting and 2. use of cupellation to obtain purified metals from working with pyrites and mineral ores in furnaces, kilns or fire-altars.

R̥gveda 1.119.9, 10 speaks of the 'mystic science' of using mākṣikā, bees' and Dadhyãc bones. I suggest that this is a pun on the word: Hieroglyph: माक्षिक [p= 805,2] mfn. (fr. मक्षिका mākṣikā) coming from or belonging to a bee Ma1rkP. Rebus: माक्षिक n. a kind of honey-like mineral substance or pyrites MBh.

The metaphor used in R̥gveda 1.119.9 to produce madhu, i.e. Soma is a reference to use of pyrites to produce electrum Soma which is also referred to in R̥gveda as amśu cognate ancu 'iron' (Tocharian) अंशु [p= 1,1] a kind of सोम libation S3Br. (Monier-Williams)

I suggest that the references to pyrites and horse bones (of Dadhyãc) in RV 1.119.9 is a narrative of metallurgical process of cupellation to remove lead ores from pyrite ores --मक्षिका mākṣikā-- to realize pure metals such as gold, silver or copper.

Many conjectures have been made on the role of the horse bones of Dadhyãc in Soma processing. I suggest that the use of bones is for cupellation process to oxidise lead iin pyrites, as 'litharge cakes of lead monoxide', thus removing lead from the mineral ores. A cupel which resembles a small egg cup, is made of ceramic or bone ash which was used to separate base metals from noble metals -- to separate noble metals, like gold and silver, from base metals like lead, copper, zinc, arsenic, antimony or bismuth, present in the ore. "The base of the hearth was dug in the form of a saucepan, and covered with an inert and porous material rich in calcium or magnesium such as shells, lime, or bone ash.The lining had to be calcareous because lead reacts with silica (clay compounds) to form viscous lead silicate that prevents the needed absorption of litharge, whereas calcareous materials do not react with lead.[7]Some of the litharge evaporates, and the rest is absorbed by the porous earth lining to form "litharge cakes".

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cupellation

Brass moulds for making cupels.Mixture of bones and wood ashes are used, together with clay, to create the cupels for cupellation.

Brass moulds for making cupels.Mixture of bones and wood ashes are used, together with clay, to create the cupels for cupellation.The ability to work with bees'wax to create metal artifacts by the cire perdue (lost-wax) method of metal castings is clearly evidenced in Nahal Mishmar artifacts (5th millennium BCE).

Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)

Akkadian head from Nineveh, 2300-2159 BCE (from Iraq 3 pl. 6) Lost-wax casting of large-scale statuary was well developed in Mesopotamia in the second half of the 3rd millennium BCE. The objec was mjade of copper. X-radiographs confirm tha the hair lines were chased onto the object after casting. Only the last stage of 'sloshing' was yet to be developed. (Davey, Christopher J., 2009, The early history of lost-wax casting, in J. Mei and Th. Rehren, eds., Metallurgy and civilisation: Eurasia and beyond archetype, London 2009, p.150)http://www.aiarch.org.au/bios/cjd/147%20Davey%202009%20BUMA%20VI%20offprint.pdf

Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.https://www.harappa.com/blog/mehrgarh-wheel-amulet-analysis-yields-many-secrets

Mehergarh. Cire perdue method used to make spoked wheel of copper/bronze. 4th millennium BCE.https://www.harappa.com/blog/mehrgarh-wheel-amulet-analysis-yields-many-secretsSayana/Wilson Trans.

1.119.09 That honey-seeking bee also murmured your praise; the son of Usij invokes you to the exhilaratin of Soma; you conciliated the mind of Dadhyãc, so that, provided with the head of a horse, he taught you (the mystic science).

1.119.10 Aśvins, you gave to Pedu the white (horse) desired by many, the breaker-through of combatants, shining, unconquerable by foes in battle, fit for every work; like Indra, the conquerer of men.

Griffith Trans.

RV 1.119.09 To you in praise of sweetness sang the honeybee-: Ausija calleth you in Soma's rapturous joy.

Ye drew unto yourselves the spirit of Dadhyãc, and then the horses' head uttered his words to you.

RV 1.119.10 A horse did ye provide for Pedu, excellent, white, O ye Aśvins, conqueror of combatants,

Invincible in war by arrows, seeking heaven worthy of fame, like Indra, vanquisher of men.

Iris of the eye + markhor Indus Script hypertext on Kuwait gold disc signifies 'goldsmith's ironsmith's workshop'

https://tinyurl.com/yc7ra4p2

This is an addendum to Kuwait gold disc, gold seal Indus Script hypertexts, metalwork catalogues, repertoire of Meluhha metalworkers https://tinyurl.com/yb4zaoaa![]()

A modified rebus reading is suggested for the 'eye', 'eyebrow' and 'iris of the eye' signified by the hypertext on Kuwait gold disc.

![]()

The iris of the is plal 'iris of the eye' (Gaw.)(CDIAL 8711) a pronuciation variant is provided by pā̆hār ʻsunshine' in Nepali. If this phonetic form pā̆hār explains the hieroglyph 'iris of the eye', the rebus reading is: pahārā m. ʻ goldsmith's workshop ʼ(Punjabi)(CDIAL 8835).. The 'iris of the eye' hieroglyph is adorned with the horns of a markhor. The markhor is read rebus: miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ(Tor.): mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4 , miṇḍha -- 2 , °aka -- , mēṭha -- 2 , mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2 , °aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ]

1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb. amŕ n/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*l l ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m., °ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., °ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, °ḍā m., °ḍhi f., H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M. mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.

2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.*mēṇḍharūpa -- , mēḍhraśr̥ṅgī -- .Addenda: mēṇḍha -- 2 : A. also mer (phonet. me r) ʻ ram ʼ(CDIAL 10310) Rebus:meḍ 'iron'. mẽṛhet 'iron' (Santali.Mu.Ho.).

*prabhāla ʻ light ʼ. [Cf. bhāla --3 n. ʻ splendour ʼ Inscr. -- prabhāˊ -- : √ bhā ]Dm. pral ʻ light ʼ; Gaw. plal, plɔl ʻ light, iris of eye ʼ, adj. ʻ light, bright ʼ; Kal. (Leitner) pralik, rumb. pre lík ʻ light ʼ, Bshk. čāl, čäl, Chil. čulo; Sv. plal adj. ʻ light, bright ʼ; Gau. čou sb., Phal. prāl; Sh. c̣alō m. ʻ lighted torch ʼ (on ac. of a and ō perh. rather < *pralōka -- ); N. pālā ʻ lamp ʼ AO xviii 230.(CDIAL 8711) N. pā̆hār ʻ sunshine, sunny place ʼ, A. pohar ʻ light ʼ; -- M. pahāṭ f. ʻ period before sunrise, dawn ʼ (+?).prabhāˊ f. ʻ light ʼ Mn. [√bhā ]Pa. Pk. pabhā -- f. ʻ light ʼ, Pk. pahā -- f.; K. prawa f. pl. ʻ rays of light, sunshine ʼ; S. piriha f. ʻ dawn ʼ; L. pôh f. ʻ dawn ʼ, (Ju.) pau f., mult. parah f., P. pauh, paih, °hi f., ḍog. pao f.; OA. puhā, A. puwā ʻ sunrise, morning time ʼ; H. pah, poh, pau f. ʻ dawn ʼ; OM. pāhe f. ʻ dawn, next day ʼ; Si. paha ʻ fire ʼ, pähä ʻ light, brilliance ʼ (or < prakāśá -- ), paba ʻ light, brightness (← Pa.?); -- ext. -- ḍa<->(CDIA 8705)

M. pasārā; -- K. pasôru m. ʻ petty shopkeeper ʼ; P. pahārā m. ʻ goldsmith's workshop ʼ; A. pohār ʻ small shop ʼ; -- ← Centre: S. pasāru m. ʻ spices ʼ; P. pasār -- haṭṭā m. ʻ druggist's shop ʼ; -- X paṇyaśālā -- : Ku. pansārī f. ʻ grocer's shop ʼ.prasāra m. ʻ extension ʼ Suśr., ʻ trader's shop ʼ Nalac. [Cf. prasārayati ʻ spreads out for sale ʼ Mn. -- √sr̥ ]Paš. lāsar ʻ bench -- like flower beds outside the window ʼ IIFL iii 3, 113; K. pasār m. ʻ rest ʼ (semant. cf. prásarati in Ku. N. Aw.); P. puhārā m. ʻ breaking out (of fever, smallpox, &c.) ʼ; Ku. pasāro ʻ extension, bigness, extension of family or property, lineage, family, household ʼ; N. pasār ʻ extension ʼ; B. pasār ʻ extent of practice in business, popularity ʼ, Or. pasāra; H. pasārā m. ʻ stretching out, expansion ʼ (→ P. pasārā m.; S. pasārom. ʻ expansion, crowd ʼ), G. pasār, °rɔ m., (CDIAL 8835)

This is an addendum to Kuwait gold disc, gold seal Indus Script hypertexts, metalwork catalogues, repertoire of Meluhha metalworkers https://tinyurl.com/yb4zaoaa

A modified rebus reading is suggested for the 'eye', 'eyebrow' and 'iris of the eye' signified by the hypertext on Kuwait gold disc.

The iris of the is plal 'iris of the eye' (Gaw.)(CDIAL 8711) a pronuciation variant is provided by pā̆hār ʻsunshine' in Nepali. If this phonetic form pā̆hār explains the hieroglyph 'iris of the eye', the rebus reading is: pahārā m. ʻ goldsmith's workshop ʼ(Punjabi)(CDIAL 8835).. The 'iris of the eye' hieroglyph is adorned with the horns of a markhor. The markhor is read rebus: miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ(Tor.): mēṇḍha

1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb. am

2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.*

Thus, the iris of the eye + markhor (horns) is a hypertext which signifies: meḍ mẽṛhet pahārā m. ʻgoldsmith's, ironsmith's workshopʼ

*prabhāla ʻ light ʼ. [Cf. bhāla --

M. pasārā; -- K. pasôr