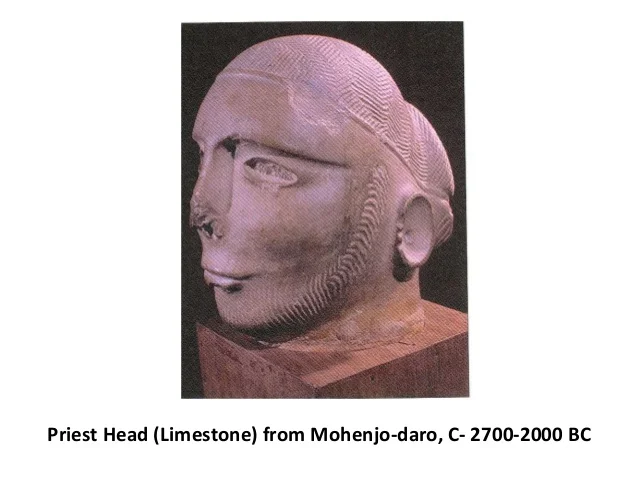

This monograph posits links between Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization and Mari of the 3rd millennium BCE and posits that the 'unicorn' standard carried on a victory procession signifies gold for ornaments produced by the artisans of the civilization who produced over 8000 inscriptions in Meluhha Indus Script. This links with the presence of Meluhha colonies in the Ancient Near East authenticated by cuneiform texts and trade in copper, tin, semi-precious stones with Meluhha. The Mohenjo-daro priest is Potr, dhavad, 'purifier priest, smelter', Potadar 'assayer of metals'. The priest of Mari is also likely to be in thie genre of temple administrators regulating trade by artisans and seafaring merchants of Meluhha who documented their wealth-creation activities on Indus Script inscriptions as wealth-accounting, metalwork, lapidary-work ledgers. This is also attested as tributes from Musiri recorded on Shalamaneser II Black Obelisk.

-- kuṭhāru कुठारु 'monkey'रत्नी ratnī 'female monkey dressed as woman' Indus Script hieroglyphs rebuskuṭhāru कुठारु 'armourer' carry ratna 'gifts'; hence, shown as tributes to Shalamaneser by Meluhha artisans and merchants रत्निन्

mfn. possessing or receiving gifts RV. (Monier-Williams)

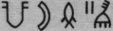

After Fig 6.2 Unicorn seal, detail of head, H95-2491, scanning electron miscroscope photo ( Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, Iconography of the Indus Unicorn: Origins and Legacy, in: Shinu Anna Abraham, Praveena Gullapalli, Teresa P. Raczek, Uzma Z. Rizvi, (Eds.), 2013,Connections and Complexity, New Approaches to the Archaeology of South Asia, Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, California, pp. 107-126) Hieroglyph III (three linear strokes): kolom 'three' rebus:kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS singi 'horned' rebus: singi 'village headman' singi 'gold for ornaments'; koḍiyum 'neck ring' rebus:koḍ 'workshop'; khara 'onager (face)' rebus: khār'blacksmith'; खोंड khōṇḍa 'A young bull' rebus: kunda, 'one of कुबेर's nine treasures', kundaṇa 'fine gold'. Composite hypertext, cyphertext: khōṇḍa khara singi kolom 'young bull, onager, one-horn (horned) rebus plain text: kōṇḍa kunda khār singi kolimi 'कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste, kō̃da कोँद 'kiln, furnace', fine-gold smith gold for ornaments smithy/forge'.

The reading of khara 'onager' ligatured to a young bovine is reinforced by:کر ś̱ẖʿkar or ḵ́ẖʿkar, 'horn' (Pashto) PLUS खोंड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi). کار کند kār-kund (corrup. of P کار کن ) adj. Adroit, clever, experienced. 2. A director, a manager; (Fem.) کار کنده kār-kundaʿh. (Pashto) P کار kār, s.m. (2nd) Business, action, affair, work, labor, profession, operation.

The reading of khara 'onager' ligatured to a young bovine is reinforced by:

Singin (adj.) [Vedic śṛngin] having a horn Vin ii. 300; J iv. 173 (=cow); clever, sharp -- witted, false Th 1, 959; A ii. 26; It 112; cp. J.P.T.S. 1885, 53. Rebus: Singī & singi (f.) [cp. Sk. śṛngī] 1. gold Vin i. 38; S ii. 234; J i. 84. -- nada gold Vv 6428; VvA 284. -- loṇa ( -- kappa) license as to ginger & salt Vin ii. 300, 306. -- vaṇṇa gold-coloured D ii. 133. -- suvaṇṇa gold VvA 167.(Pali)

Cuneiform text related to the four sides reads in translation from Akkadian:

These hieroglyphs are read rebus in Meluhha expressions since Musri is an area of Kurds many of whom practice Hindu traditions even today.

The readings in Meluhha expressions, of the hypertexts and plan texts are:

karibha 'camels' rebus: karba, 'iron'

ranga 'buffalo' rebus: ranga 'pewter'

sakea is a composite animal hypertext in Indus Script: khara 'onager' PLUS khoṇḍa 'young bull' PLUSmer̥ha 'crumpled (horn)' rebus: kār kunda 'blackmith, turner, goldsmith' کار کنده kār-kunda 'manager, director, adroit, clever, experienced' (Pashto) medhā 'yajna, dhanam' med 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic)

susu is antelope: ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin'

karibha, ibha, 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron'

bazitu/uqupu is monkey/ape: kuṭhāru कुठारु monkey; rebus: kuṭhāru, कुठारु an armourer.

![]() Two monkey anthropomorphs are held in leash following the elephant.

Two monkey anthropomorphs are held in leash following the elephant.

The first monkey is read rebus as: कुठारु 'monkey' (Monier-Williams) Rebus: कुठारु 'armourer' (Monier-Williams)

The second monkey anthropomorph turns its head backwards. The rebus readings of this second animal are:

ūkam

ūkam

Hieroglyph: Female monkey: ஊகம்1 ūkam , n. 1. Female monkey; பெண் குரங்கு. (திவா.) 2. Black monkey; கருங் குரங்கு. பைங்க ணூகம்பாம்பு பிடித்தன்ன (சிறுபாண் . 221). 3. cf. ஊகை2 . இயூகம் iyūkam , n. < ஊகம் . Black monkey; கருங்குரங்கு . (பெருங். வத்தவ . 17, 14.) வல்லூகம்2 val-l-ūkam , n. < வல்1 + ஊகம்1 . (W .) 1. Male monkey; ஆண்குரங்கு . 2. Large ape; முசு . கருவிரலூகம் karu-viral-ūkam , n. < கரு-மை +. A catapultic machine, of the shape of a monkey with black claws, mounted on the walls of a fort in ancient times and intended to seize and bite the approaching enemy; கரிய விரல்களையுடைய குரங்குபோலிருந்து சேர்ந்தாரைக் கடிக்கும் மதிற்பொறி. கருவிரலூகமுங் கல்லுமிழ் கவ ணும் (சிலப் . 15, 208). காரூகம் kār-ūkam , n. < கார் + ஊகம் . Black monkey; கருங்குரங்கு. (திவா.) யூகம்1 yūkam , n. < ஊகம்1 . 1. Black monkey; கருங்குரங்கு. யூகமொடு மாமுக முசுக்கலை (திருமுரு . 302). (பிங் .) 2. Female monkey; பெண்குரங்கு. (திவா.)

Ko. uk steel. Ka. urku, ukku id. Koḍ. ur- (uri-) to melt (intr.); urïk- (urïki-) id. (tr.); ukkï steel. Te.ukku id. Go. (Mu.) urī-, (Ko.) uṛi- to be melted, dissolved; tr. (Mu.) urih-/urh- (Voc. 262). Konḍa (BB) rūg- to melt, dissolve. Kui ūra (ūri-) to be dissolved; pl. action ūrka (ūrki-); rūga (rūgi-) to be dissolved. Kuwi (Ṭ.) rūy- to be dissolved; (S.) rūkhnai to smelt; (Isr.) uku, (S.) ukku steel. (DEDR 661)

On this sculptural frieze, the first animal from the left has been mentioned in the cuneiform inscription and translated as a river- or water-ox (buffalo). It is possible that the iconography of the animal may signify an aurochs or zebuand thus, the animal may be a composite animal in Indus Script Cipher tradition of iconography. The animal has a scarf on its shoulder and the horns merge into a circle. The cleft hoofs of the three bovines are clearly indicated in the iconography.

On this sculptural frieze, the first animal from the left has been mentioned in the cuneiform inscription and translated as a river- or water-ox (buffalo). It is possible that the iconography of the animal may signify an aurochs or zebuand thus, the animal may be a composite animal in Indus Script Cipher tradition of iconography. The animal has a scarf on its shoulder and the horns merge into a circle. The cleft hoofs of the three bovines are clearly indicated in the iconography. ukṣán

https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/ancient_records_assyria1.pdf

Hieroglyph: scarf on the shoulder of the bovine: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√

I suggest that the Meluhha expression which is consistent with the iconography and the cuneiform inscription is that the animal is a zebu. Thus, the animal with the scarf on its neck is read rebus as: पोळ pōḷa, 'zebu, bos indicus' signifies pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide Fe3O4' PLUS dhatu 'scarf' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral'. Thus, the animal signifies the wealth resource tribute of iron magnetite ore PLUS circle as horn: vaṭṭa 'circle'. Thus, the expression of scarf PLUS horns is read as: dhã̄i 'mineral ore' PLUS vaṭṭa 'circle' rebus: dhāvaḍ 'smelter'. Thus, the mineral wealth as a tribute signified by this composite animal signifies smelted iron, magnetite ore.

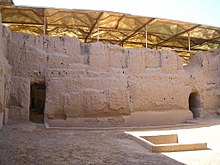

"Mari is not considered a small settlement that later grew, but rather a new city that was purposely founded during the Mesopotamian Early Dynastic period I c. 2900 BC, to control the waterways of the Euphrates trade routes that connect the Levantwith the Sumerian south.The city was built about 1 to 2 kilometers away from the Euphrates river to protect it from floods,and was connected to the river by an artificial canal that was between 7 and 10 kilometers long, depending on which meander it used for transport, which is hard to identify today.(Margueron, Jean-Claude (2013). "The Kingdom of Mari". In Crawford, Harriet (ed.). The Sumerian World. Translated by Crawford, Harriet. Routledge, p.520)

"The city is difficult to excavate as it is buried deep under later layers of habitation.[4] A defensive system against floods composed of a circular embankment was unearthed,[4] in addition to a circular 6.7 m thick internal rampart to protect the city from enemies.[4]An area 300 meters in length filled with gardens and craftsmen quarters[5] separated the outer embankment from the inner rampart, which had a height of 8 to 10 meters and was strengthened by defensive towers....Mari's (Tell Harriri) position made it an important trading center as it controlled the road linking between the Levant and Mesopotamia. The Amorite Mari maintained the older aspects of the economy, which was still largely based on irrigated agriculture along the Euphrates valley. The city kept its trading role and was a center for merchants from Babylonia and other kingdoms, it received goods from the south and east through riverboats and distributed them north, north west and west.[174] The main merchandises handled by Mari were metals and tin imported from the Iranian Plateau and then exported west as far as Crete. Other goods included copper from Cyprus, silver from Anatolia, woods from Lebanon, gold from Egypt, olive oil, wine, and textiles in addition to precious stones from modern Afghanistan...Mari was classified by the archaeologists as the "most westerly outpost of Sumerian culture".(Gadd, Cyril John (1971). "The Cities of Babylonia". In Edwards, Iorwerth Eiddon Stephen; Gadd, Cyril John; Hammond, Nicholas Geoffrey Lemprière (eds.). Part 2: Early History of the Middle East. The Cambridge Ancient History (Second Revised Series). 1 (3 ed.). Cambridge University Press, p.97. )...A journal devoted to the site since 1982, is Mari: Annales de recherches interdisciplinaires...Since the beginning of excavations, over 25,000 clay tablets in Akkadian language written in cuneiform were discovered...The language of the texts is official Akkadian, but proper names and hints in syntax show that the common language of Mari's inhabitants was Northwest Semitic...Excavations stopped as a result of the Syrian Civil War that began in 2011 and continues to the present (2019).The site came under the control of armed gangs and suffered large scale looting. A 2014 official report revealed that robbers were focusing on the royal palace, the public baths, the temple of Ishtar and the temple of Dagan.

Frise d'un panneau de mosaïque

Vers 2500 - 2400 avant J.-C.

Mari, temple d'Ishtar Fouilles Parrot, 1934 - 1936

AO 19820

These inlaid mosaics, composed of figures carved in mother-of-pearl, against a background of small blocks of lapis lazuli or pink limestone, set in bitumen, are among the most original and attractive examples of Mesopotamian art. It was at Mari that a large number of these mosaic pieces were discovered. Here they depict a victory scene: soldiers lead defeated enemy captives, naked and in chains, before four dignitaries.

A victory scene

The pieces that make up this shell mosaic composition were found scattered on the floor of the Temple of Ishtar, and therefore the reconstruction of the original panel is based on guesswork, all the more so in that the shell pieces are missing. The shell figures were arranged on a wooden panel covered with a layer of bitumen. The whole composition was organized in several registers, and the frame of the panel was emphasized by a double red and white line of stone and shell. The spaces between the figures were filled by small tiles of gray-black shale. The panel depicts the end of a battle, with soldiers leading their stripped and bound captives before dignitaries. The soldiers wear helmets, carry spears or adzes, and are dressed in kaunakes (fleecy skirts or kilts) and scarves. The dignitaries wear kaunakes and low fur hats, and each carries a long-handled adze on the left shoulder. Their leader appears to be a shaven-headed figure: stripped to the waist and wearing kaunakes, he carries a standard showing a bull standing on a pedestal. The lower register, on the right, features traces of a chariot drawn by onagers, a type of wild ass.

The art of mosaic

Many fragments of mosaic panels were discovered in the temples of Mari. Used to decorate the soundboxes of musical instruments, "gaming tables," or simple rectangular wooden panels, the pieces of mosaic seen here were like scattered pieces of a jigsaw puzzle when they were found. Mosaic pictures were particularly prized in Mesopotamia. Fragments can be found in Kish, Tello, and Tell Asmar, in Mesopotamia, and in Ebla, Syria, where these extremely fragile works of art did not survive the destruction of the buildings in which they were housed. Only the Standard of Ur (Mesopotamia) has been preserved, an object which offers many points of comparison with the present work, since one side of this artifact is devoted to the theme of war. We know that the fragments discovered at Mari were manufactured locally, for the workshop of an engraver using mother-of-pearl was found in the palace. By the delicacy of their carving and engraving, the mother-of-pearl figures produced in this capital of a kingdom on the Middle Euphrates distinguish it from other centers of artistic production; they sometimes even surpass works of art produced in the Mesopotamian city of Ur. One of the distinctive features of Mari is the diversity of the scenes depicted: battles and scenes of offerings made to the gods, religious scenes with priests and priestesses, and sacrifices of rams.These scenes provide us with invaluable insights into the social, political, and religious life of Mari.

Bibliography

Contenau G., Manuel d'archéologie orientale depuis les origines jusqu'à Alexandre : les découvertes archéologiques de 1930 à 1939, IV, Paris : Picard, 1947, pp. 2049-2051, fig. 1138

Parrot A., Les fouilles de Mari, première campagne (hiver 1933-1934), Extr. de : Syria, 16, 1935, paris : P. Geuthner, pp. 132-137, pl. XXVIII

Parrot A., Mission archéologique de Mari : vol. I : le temple d'Ishtar, Bibliothèque archéologique et historique, LXV, Paris : Institut français d'archéologie du Proche-Orient, 1956, pp. 136-155, pls. LVI-LVII

Parrot A., Les fouilles de Mari, première campagne (hiver 1933-1934), Extr. de : Syria, 16, 1935, paris : P. Geuthner, pp. 132-137, pl. XXVIII

Parrot A., Mission archéologique de Mari : vol. I : le temple d'Ishtar, Bibliothèque archéologique et historique, LXV, Paris : Institut français d'archéologie du Proche-Orient, 1956, pp. 136-155, pls. LVI-LVII

The remains of the royal palace of Mari. "The Royal Palace of Mari was the royal residence of the rulers of the ancient kingdom of Mari in eastern Syria. Situated centrally amidst Palestine, Syria, Babylon, Levant, and other Mesopotamian city-states, Mari acted as the “middle-man” to these larger, powerful kingdoms.[2] Both the size and grand nature of the palace demonstrate the importance of Mari during its long history, though the most intriguing feature of the palace is the nearly 25,000 tablets found within the palace rooms.[3] The royal palace was discovered in 1935, excavated with the rest of the city throughout the 1930s, and is considered one of the most important finds made at Mari[4] André Parrotled the excavations and was responsible for the discovery of the city and the palace. Thousands of clay tablets were discovered through the efforts of André Bianquis, which provided archaeologists the tools to learn about, and to understand, everyday life at the palace and in Mari.[5] The discovery of the tablets also aided in the labeling of various rooms in terms of their purpose and function...The palace reached its grandest state with its last renovation under king Zimri-Lim in the 18th century BC; in addition to serving as the home of the royal family, the palace would have also housed royal guards, state workers, members of the military, and those responsible for the daily activities of the kingdom...Statues of gods and past rulers were the most common among statues unearthed at the Palace of Zimri-Lin. The title of Shakkanakku (military governor) was borne by all the princes of a dynasty who reigned at Mari in the late third millennium and early second millennium BC. These kings were the descendents of the military governors appointed by the kings of Akkad. Statues and sculpture were used to decorate the exterior and interior of the palace. Zimri-Lin used these statues to connect his kingship to the gods and to the traditions of past rulers. Most notable of these statues are the statue of Iddi-Ilum, Ishtup-Ilum, the Statue of the Water Goddess, and Puzur-Ishtar."

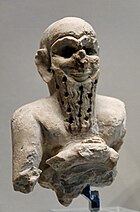

The remains of the royal palace of Mari. "The Royal Palace of Mari was the royal residence of the rulers of the ancient kingdom of Mari in eastern Syria. Situated centrally amidst Palestine, Syria, Babylon, Levant, and other Mesopotamian city-states, Mari acted as the “middle-man” to these larger, powerful kingdoms.[2] Both the size and grand nature of the palace demonstrate the importance of Mari during its long history, though the most intriguing feature of the palace is the nearly 25,000 tablets found within the palace rooms.[3] The royal palace was discovered in 1935, excavated with the rest of the city throughout the 1930s, and is considered one of the most important finds made at Mari[4] André Parrotled the excavations and was responsible for the discovery of the city and the palace. Thousands of clay tablets were discovered through the efforts of André Bianquis, which provided archaeologists the tools to learn about, and to understand, everyday life at the palace and in Mari.[5] The discovery of the tablets also aided in the labeling of various rooms in terms of their purpose and function...The palace reached its grandest state with its last renovation under king Zimri-Lim in the 18th century BC; in addition to serving as the home of the royal family, the palace would have also housed royal guards, state workers, members of the military, and those responsible for the daily activities of the kingdom...Statues of gods and past rulers were the most common among statues unearthed at the Palace of Zimri-Lin. The title of Shakkanakku (military governor) was borne by all the princes of a dynasty who reigned at Mari in the late third millennium and early second millennium BC. These kings were the descendents of the military governors appointed by the kings of Akkad. Statues and sculpture were used to decorate the exterior and interior of the palace. Zimri-Lin used these statues to connect his kingship to the gods and to the traditions of past rulers. Most notable of these statues are the statue of Iddi-Ilum, Ishtup-Ilum, the Statue of the Water Goddess, and Puzur-Ishtar." A Mariote from the second kingdom. (25th century BCE)

A Mariote from the second kingdom. (25th century BCE) Statue of Ebih-Il. (25th century BCE)

Statue of Ebih-Il. (25th century BCE)

Cylinder dating to the Second Kingdom. (25th century BCE)

The lion of Mari. (22nd century BCE)

The lion of Mari. (22nd century BCE) Goddess of the vase. (18th century BCE). Statue of a Water Goddess. Was originally a fountain, with water flowing out of the vase. The circular design of the mouth of the vase compares with the design of Eyes in the Eye Temple.

Goddess of the vase. (18th century BCE). Statue of a Water Goddess. Was originally a fountain, with water flowing out of the vase. The circular design of the mouth of the vase compares with the design of Eyes in the Eye Temple.

Investiture of Zimri-Lim (19th cent. BCE)

Puzur Ishtar, Shakkanakku of Mari. (c. 2050 BCE). Former Governor of Mari.

Puzur Ishtar, Shakkanakku of Mari. (c. 2050 BCE). Former Governor of Mari.

The kingdom of Nagar c. 2340 BCE.

Eye figurines from the Eye Temple."During the third millennium BC, the city was known as "Nagar", which might be of Semitic origin and mean a "cultivated place". The name "Nagar" ceased occurring following the Old Babylonian period,however, the city continued to exist as Nawar, under the control of Hurrian state of Mitanni. Hurrian kings of Urkesh took the title "King of Urkesh and Nawar" in the third millennium BC; although there is general view that the third millennium BC Nawar is identical with Nagar, some scholars, such as Jesper Eidem, doubt this.Those scholars opt for a city closer to Urkesh which was also called Nawala/Nabula as the intended Nawar."https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tell_Brak"

Eye figurines from the Eye Temple."During the third millennium BC, the city was known as "Nagar", which might be of Semitic origin and mean a "cultivated place". The name "Nagar" ceased occurring following the Old Babylonian period,however, the city continued to exist as Nawar, under the control of Hurrian state of Mitanni. Hurrian kings of Urkesh took the title "King of Urkesh and Nawar" in the third millennium BC; although there is general view that the third millennium BC Nawar is identical with Nagar, some scholars, such as Jesper Eidem, doubt this.Those scholars opt for a city closer to Urkesh which was also called Nawala/Nabula as the intended Nawar."https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tell_Brak"The kingdom of Nagar c. 2340 BCE.

NOV

2

Indus Script 'Unicorn' on Mari mosaic frieze procession of Ishtar temple is kunda, lapidary, furnace metalwork artificer

कुन्द is a name of विष्णु, Kubera's treasure. Rebus pictographs Meluhha signifiers of कुन्द lapidary, goldsmith, metalworker setter of gems in gold jewels. Shown with a standard device (lathe, portable furnace) which is sangaḍ, he is also rebus: jangaḍiyo 'guard accompanying treasure into the treasury' (Gujarati). The rebus expression jangaḍ signifies a unique method of invoicng on approval basis which is practised even today by jewellers and diamond workers of Gujarat.

Reinforcement is provided by many artifacts with Indus Script hypertexts which signify a cattlepen. The word in Indian sprachbuns for a cattlepen is:कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa f A fold or pen. कोंडवाड kōṇḍavāḍa C (कोंडणें & वाडा) A pen or fold for cattle. कोंडी kōṇḍī ...confined place gen.; a lockup house, a pen, fold, pound Rebus: Fine gold: Ta. kuntaṉam interspace for setting gems in a jewel; fine gold (< Te.). Ka. kundaṇa setting a precious stone in fine gold; fine gold; kundana fine gold. Tu. kundaṇapure gold. Te. kundanamu fine gold used in very thin foils in setting precious stones; setting precious stones with fine gold.(DEDR 1725)

Evidences for the signifier of one-horned young bull ('unicorn') on Ancient Near East artifacts including cylinder seals are presented in this monograph.

कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa, 'cattlepen', Mesopotamia Rebus: kundaṇa 'fine gold' Rebus: konda 'lapidary, metalworker, setting gems in find gold jewels'. singi 'horned' rebus: singi ;gold for ornaments'. श्रंग् । शृङ्गम्, प्रधानभूतः m. a horn; the top, peak, summit of a mountain; the head man or leading person in a village or the like.

Mudhif and three reed banners

Figure 15.1. Sealing with representations of reed structures with cows, calves, lambs, and ringed

bundle “standards” of Inana (drawing by Diane Gurney. After Hamilton 1967, fig. 1)

Three rings on reed posts are three dotted circles: dāya 'dotted circle' on dhā̆vaḍ priest of 'iron-smelters', signifies tadbhava from Rigveda dhāī ''a strand (Sindhi) (hence, dotted circle shoring cross section of a thread through a perorated bead);rebus: dhāū, dhāv ʻa partic. soft red ores'. dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

Cylinder seal impression, Uruk period, Uruk?, 3500-2900 BCE. Note a load of livestock (upper), overlapping greatly (weird representation), and standard 'mudhif' reed house form common to S. Iraq (lower).

Cattle Byres c.3200-3000 B.C. Late Uruk-Jemdet Nasr period. Magnesite. Cylinder seal. In the lower field of this seal appear three reed cattle byres. Each byre is surmounted by three reed pillars topped by rings, a motif that has been suggested as symbolizing a male god, perhaps Dumuzi. Within the huts calves or vessels appear alternately; from the sides come calves that drink out of a vessel between them. Above each pair of animals another small calf appears. A herd of enormous cattle moves in the upper field. Cattle and cattle byres in Southern Mesopotamia, c. 3500 BCE. Drawing of an impression from a Uruk period cylinder seal. (After Moorey, PRS, 1999, Ancient mesopotamian materials and industries: the archaeological evidence, Eisenbrauns.)

A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia.

· Fragment of a stele, raised standards. From Tello.

· Hieroglyphs: Quadrupeds exiting the mund (or mudhif) are pasaramu, pasalamu ‘an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped’ (Telugu) పసరము [ pasaramu ] or పసలము pasaramu. [Tel.] n. A beast, an animal. గోమహిషహాతి.

· A cow and a stable of reeds with sculpted columns in the background. Fragment of another vase of alabaster (era of Djemet-Nasr) from Uruk, Mesopotamia. Limestone 16 X 22.5 cm. AO 8842, Louvre, Departement des Antiquites Orientales, Paris, France. Six circles decorated on the reed post are semantic determinants of Glyphआर [ āra ] A term in the play of इटीदांडू,--the number six. (Marathi) आर [ āra ] A tuft or ring of hair on the body. (Marathi) Rebus: āra ‘brass’. काँड् । काण्डः m. the stalk or stem of a reed, grass, or the like, straw. In the compound with dan 5 (p. 221a, l. 13) the word is spelt kāḍ. The rebus reading of the pair of reeds in Sumer standard is: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’.

Rebus: pasra = a smithy, place where a black-smith works, to work as a blacksmith; kamar pasra = a smithy; pasrao lagao akata se ban:? Has the blacksmith begun to work? pasraedae = the blacksmith is at his work (Santali.lex.) pasra meṛed, pasāra meṛed = syn. of koṭe meṛed = forged iron, in contrast to dul meṛed, cast iron (Mundari.lex.) పసారము [ pasāramu ] or పసారు pasārdmu. [Tel.] n. A shop. అంగడి.

· http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-standard-compares-with-nahal.html

· Both hieroglyphs together may have read rebus: *kāṇḍāra: *kāṇḍakara ʻ worker with reeds or arrows ʼ. [kāˊṇḍa -- , kará -- 1] L. kanērā m. ʻ mat -- maker ʼ; H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers ʼ.(CDIAL 3024). Rebus: kaṇḍa 'fire-altar'. khaṇḍa 'implements' (Santali) लोखंड (p. 423) lōkhaṇḍa n (लोह S) Iron. लोखंडकाम (p. 423) lōkhaṇḍakāma n Iron work; that portion (of a building, machine &c.) which consists of iron. 2 The business of an ironsmith. लोखंडी (p. 423) lōkhaṇḍī a (लोखंड) Composed of iron; relating to iron.

· Mudhif is a cattle pen.

·

· Sumerian mudhif (reedhouse) http://www.laputanlogic.com/articles/2004/01/24-0001.html

· and modern mudhif structure (Iraq) compare with the Toda mund (sacred hut)

·

·

·

· The Uruk trough. From Uruk (Warka), southern Iraq. Late Prehistoric period, about 3300-3000 BC

· A cult object in the Temple of Inanna?

· This trough was found at Uruk, the largest city so far known in southern Mesopotamia in the late prehistoric period (3300-3000 BC). The carving on the side shows a procession of sheep approaching a reed hut (of a type still found in southern Iraq) and two lambs emerging. The decoration is only visible if the trough is raised above the level at which it could be conveniently used, suggesting that it was probably a cult object, rather than of practical use. It may have been a cult object in the Temple of Inana (Ishtar), the Sumerian goddess of love and fertility; a bundle of reeds (Inanna's symbol) can be seen projecting from the hut and at the edges of the scene. Later documents make it clear that Inanna was the supreme goddess of Uruk. Many finely-modelled representations of animals and humans made of clay and stone have been found in what were once enormous buildings in the centre of Uruk, which were probably temples. Cylinder seals of the period also depict sheep, cattle, processions of people and possibly rituals. Part of the right-hand scene is cast from the original fragment now in the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Berlin

· J. Black and A. Green, Gods, demons and symbols of -1 (London, The British Museum Press, 1992)

· H.W.F. Saggs, Babylonians (London, The British Museum Press, 1995)

· D. Collon, Ancient Near Eastern art (London, The British Museum Press, 1995)

· H. Frankfort, The art and architecture of th (London, Pelican, 1970)

· P.P. Delougaz, 'Animals emerging from a hut', Journal of Near Eastern Stud-1, 27 (1968), pp. 186-7 http://www.britishmuseum.org/explore/highlights/highlight_objects/me/t/the_uruk_trough.aspx

· Sumerian mudhif facade, with uncut reed fonds and sheep entering, carved into a gypsum trough from Uruk, c. 3200 BCE (British Museum WA 12000). Photo source.

· See also: Expedition 40:2 (1998), p. 33, fig. 5b Life on edge of the marshes.

· Fig. 5B. Carved gypsum trough from Uruk. Two lambs exit a reed structure identifical to the present-day mudhif on this ceremonial trough from the site of Uruk in northern Iraq. Neither the leaves or plumes have been removed from the reds which are tied together to form the arch. As a result, the crossed-over, feathered reeds create a decorative pattern along the length of the roof, a style more often seen in modern animal shelters built by the Mi'dan. Dating to ca. 3000 BCE, the trough documents the extraordinry length of time, such arched reed buildings have been in use. (The British Museum BCA 120000, acg. 2F2077)

· End of the Uruk trough. Length: 96.520 cm Width: 35.560 cm Height: 15.240 cm

· 284 x 190 mm. Close up view of a Toda hut, with figures seated on the stone wall in front of the building. Photograph taken circa 1875-1880, numbered 37 elsewhere. Royal Commonwealth Society Library. Cambridge University Library. University of Cambridge.

· The Toda mund, from, Richard Barron, 1837, "View in India, chiefly among the Nilgiri Hills'. Oil on canvas. The architecture of Iraqi mudhif and Toda mund -- of Indian linguistic area -- is comparable.

· A Toda temple in Muthunadu Mund near Ooty, India.http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Toda_people

· The hut of a Toda Tribe of Nilgiris, India. Note the decoration of the front wall, and the very small door.

· ![]() Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.

Rebus Meluhha readings: kōṭhā 'warehouse' kuṭhāru 'armourer, PLUS kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS ḍhāla 'flagstaff' rebus: ḍhālako 'large ingot'. Thus, the message is: armoury, smithy, forge ingots.·

· m0702 Text 2206 showing Sign 39, a glyph which compares with the Sumerian mudhif structure.

· - ढालकाठी [ ḍhālakāṭhī ] f ढालखांब m A flagstaff; esp.the pole for a grand flag or standard.

· ढाल [ ḍhāla ] 'flagstaff' rebus: dhalako 'a large metal ingot (Gujarati) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati). The mudhif flag on the inscription is read rebus: xolā 'tail' Rebus: kole.l 'smithy, temple'. The structure is goṭ 'catttle-pen' (Santali) rebus: koṭṭhaka 'warehouse'. [kōṣṭhāgāra n. ʻ storeroom, store ʼ Mn. [kṓṣṭha -- 2, agāra -- ]Pa. koṭṭhāgāra -- n. ʻ storehouse, granary ʼ; Pk. koṭṭhāgāra -- , koṭṭhāra -- n. ʻ storehouse ʼ; K. kuṭhār m. ʻ wooden granary ʼ, WPah. bhal. kóṭhār m.; A. B. kuṭharī ʻ apartment ʼ, Or. koṭhari; Aw. lakh. koṭhārʻ zemindar's residence ʼ; H. kuṭhiyār ʻ granary ʼ; G. koṭhār m. ʻ granary, storehouse ʼ, koṭhāriyũ n. ʻ small do. ʼ; M. koṭhār n., koṭhārẽ n. ʻ large granary ʼ, -- °rī f. ʻ small one ʼ; Si. koṭāra ʻ granary, store ʼ.WPah.kṭg. kəṭhāˊr, kc. kuṭhār m. ʻ granary, storeroom ʼ, J. kuṭhār, kṭhār m.; -- Md. kořāru ʻ storehouse ʼ ← Ind.(CDIAL 3550)] Rebus: kuṭhāru 'armourer,

·

· ![]() Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.

Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.

Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.

Field symbol is zebu (bos indicus). pōḷa 'zebu, bos indicus' rebus: pōḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' [pōlāda] 'steel'.· Text 1330 (appears with Zebu glyph) showing Sign 39. Pictorial motif: Zebu (Bos indicus) This sign is comparable to the cattle byre of Southern Mesopotamia dated to c. 3000 BCE. Rebus Meluhha readings of gthe inscription are from r. to l.: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS goṭ 'cattle-pen' rebus: koṭṭhāra 'warehouse' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' PLUS aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS kuṭika— 'bent' MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) PLUS kanka, karṇika कर्णिक 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale'. Read together with the fieldsymbol of the zebu,the message is: magnetite ore smithy, forge, warehouse, iron alloy metal, bronze merchandise (ready for loading as cargo).

·

· goṭ = the place where cattle are collected at mid-day (Santali); goṭh (Brj.)(CDIAL 4336). goṣṭha (Skt.); cattle-shed (Or.) koḍ = a cow-pen; a cattlepen; a byre (G.) कोठी cattle-shed (Marathi) कोंडी [ kōṇḍī ] A pen or fold for cattle. गोठी [ gōṭhī ] f C (Dim. of गोठा) A pen or fold for calves. (Marathi)

·

· koṭṭhaka1 (nt.) "a kind of koṭṭha," the stronghold over a gateway, used as a store -- room for various things, a chamber, treasury, granary Vin ii.153, 210; for the purpose of keeping water in it Vin ii.121=142; 220; treasury J i.230; ii.168; -- store -- room J ii.246; koṭthake pāturahosi appeared at the gateway, i. e. arrived at the mansion Vin i.291.; -- udaka -- k a bath -- room, bath cabinet Vin i.205 (cp. Bdhgh's expln at Vin. Texts ii.57); so also nahāna -- k˚ and piṭṭhi -- k˚, bath -- room behind a hermitage J iii.71; DhA ii.19; a gateway, Vin ii.77; usually in cpd. dvāra -- k˚ "door cavity," i. e. room over the gate: gharaŋ satta -- dvāra -- koṭṭhakapaṭimaṇḍitaŋ "a mansion adorned with seven gateways" J i.227=230, 290; VvA 322. dvāra -- koṭṭhakesu āsanāni paṭṭhapenti "they spread mats in the gateways" VvA 6; esp. with bahi: bahi -- dvārakoṭṭhakā nikkhāmetvā "leading him out in front of the gateway" A iv.206; ˚e thiṭa or nisinna standing or sitting in front of the gateway S i.77; M i.161, 382; A iii.30. -- bala -- k. a line of infantry J i.179. -- koṭṭhaka -- kamma or the occupation connected with a storehouse (or bathroom?) is mentioned as an example of a low occupation at Vin iv.6; Kern, Toev. s. v. "someone who sweeps away dirt." (Pali)

·

· कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa, 'cattlepen', Mesopotamia Rebus: kundaṇa 'fine gold'

·

One-horned young bulls and calves are shown emerging out of कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa cattlepens heralded by Inana standards atop the mudhifs. The Inana standards are reeds with three rings. The reed standard is the same which is signified on Warka vase c. 3200–3000 BCE. Ring on a standard is also shown on Jasper cylinder seal with four standardd bearers holding aloft Indus Script hypertexts. See:

One-horned young bulls and calves are shown emerging out of कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa cattlepens heralded by Inana standards atop the mudhifs. The Inana standards are reeds with three rings. The reed standard is the same which is signified on Warka vase c. 3200–3000 BCE. Ring on a standard is also shown on Jasper cylinder seal with four standardd bearers holding aloft Indus Script hypertexts. See:

· Ancient Near East jasper cylinder seal, Warka vase hieroglyphs: crucible iron, zinc, lead, copper kāṇḍa metalwork implements http://tinyurl.com/o5sozfv

कुन्द a turner's lathe (Monier-Williams) कुन्द N. of विष्णु MBh. xiii. 7036; one of कुबेर's nine treasures (N. of a गुह्यक Gal. ) (Monier-Williams) Fine gold, lapidary work: Ta. kuntaṉam interspace for setting gems in a jewel; fine gold (< Te.). Ka. kundaṇa setting a precious stone in fine gold; fine gold; kundana fine gold. Tu. kundaṇapure gold. Te. kundanamu fine gold used in very thin foils in setting precious stones; setting precious stones with fine gold(DEDR 1725)

kunda is thus a lapidary, a worker with a lathe, setting gems in gold jewels. A cognate word signifies a cattle-pen: कोंडण kōṇḍaṇa f A fold or pen. कोंडणी kōṇḍaṇī f (Poetry. कोंडणें) Shut up, confined, embarrassed, or perplexed state, lit. fig. Ex. ऐशा विचाराच्या घालुनि कोंडणीं ॥ काय चक्रपाणि निजले ती ॥. कोंडणें kōṇḍaṇēṃ v c To shut up; to stop or block up; to confine gen. (a person in a room, a stream by an embankment, the breath &c.) 2 fig. To pose, puzzle, confute, silence. कोंडी kōṇḍī f (कोंडणें) A confined place gen.; a lockup house, a pen, fold, pound; a receiving apartment or court for Bráhmans gathering for दक्षिणा; a prison at the play of आट्यापाट्या; a dammed up part of a stream &c. &c. कोंडवाड kōṇḍavāḍa n f C (कोंडणें & वाडा) A pen or fold for cattle.(Marathi) gōṣṭhá m. ʻ cow -- house ʼ RV., ʻ meeting place ʼ MBh. 2. *gōstha -- . [

The standard bearer looks like the priest shown on the Tell al Ubaid temple architectural frieze.

Figure 15.6. Tell al Ubaid, Temple of Ninhursag. Tridacna shell inlaid architectural frieze with bitumen

and black shale. Early Dynastic period (ca. 2600 b.c.) (Hall and Woolley 1927)

Figure 15.5. Tell al Ubaid, Temple of Ninhursag. Tridacna shell-inlaid architectural frieze with bitumen

and black shale. Early Dynastic period (ca. 2600 b.c.e.) (© The Trustees of the British Museum)

कोंडी (p. 102) kōṇḍī f (कोंडणें) A confined place gen.; a lockup house, a pen, fold, pound; a receiving apartment or court for Bráhmans gathering for दक्षिणा; a prison at the play of आट्यापाट्या; a dammed up part of a stream &c. &c. कोंडवाड (p. 102) kōṇḍavāḍa n f C (कोंडणें & वाडा) A pen or fold for cattle. कोंडण (p. 102) kōṇḍaṇa f A fold or pen. कोंडमार (p. 102) kōṇḍamāra or -मारा m (कोंडणें & मारणें) Shutting up in a confined place and beating. Gen. used in the laxer senses of Suffocating or stifling in a close room; pressing hard and distressing (of an opponent) in disputation; straitening and oppressing (of a person) under many troubles or difficulties; कोंडाळें (p. 102) kōṇḍāḷēṃ n (कुंडली S) A ring or circularly inclosed space. 2 fig. A circle made by persons sitting round. कोंड (p. 102) kōṇḍa m C A circular hedge or field-fence. 2 A circle described around a person under adjuration. 3 The circle at marbles. 4 A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste. 5 Grounds under one occupancy or tenancy. 6 f R A deep part of a river. 7 f (Or कोंडी q. v.) A confined place gen.; a lock-up house &c.

Shell plaque of a Sumerian Soldier with a Battleaxe from the city of Mari. same time period as the Royal Tombs of Ur. Louvre

Shell plaque of a Sumerian Soldier with a Battleaxe from the city of Mari. same time period as the Royal Tombs of Ur. LouvreCuneiform texts evidence trade of Ancient Near East areas with Meluhha and Shu-ilishu seal attests a language called Meluhha.

Indus Script inscriptions use a logo-semantic writing system to express Meluhha words related to wealth accounting ledgers of metalwork.

A vivid link to priest image carrying, in a procession, the banner of 'one-horned young bull' of Sarasvati Civilization is presented on a painting in Mari (showing association with metalwork/metal weapons).

Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820 (Fig.2) Indus Script Cipher provides a clue to the standard of Mari which is signified by a young bull with one horn.

On the Mari mosaic panel, a similar-looking priest leads a procession with a unique flag. The flagpost is a culm of millet and at the top of the post is a rein-ring proclaiming a one-horned young bull. All these are Indus Script hieroglyphs. The 'rein rings' are read rebus: valgā, bāg-ḍora 'bridle' rebus (metath.) bagalā 'seafaring dhow'.

Hypertexts on a procession depicted on the schist panel inlaid with mother of pearl plaques are: 1. culm of millet and 2. one-horned young bull (which is a common pictorial motif in Harappa (Indus) Script Corpora.

Culm of millet hieroglyph: karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

One-horned young bull hypertext/hyperimage: कोंद kōnda ‘young bull' कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, turner'. कुलालादिकन्दुः f. a kiln; a potter's kiln; kō̃da कोँद 'potter's kiln' (Kashmiri) Thus, an iron turner (in smithy/forge).

Culm of millet hieroglyph: karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

One-horned young bull hypertext/hyperimage: कोंद kōnda ‘young bull' कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, turner'. कुलालादिकन्दुः f. a kiln; a potter's kiln; kō̃da कोँद 'potter's kiln' (Kashmiri) Thus, an iron turner (in smithy/forge).

![]() The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. The cuneiform text reads: Shu-Ilishu

The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. The cuneiform text reads: Shu-Ilishu

EME.BAL.ME.LUH.HA.KI (interpreter of Meluhha language).

The Shu-ilishu cylinder seal is a clear evidence of the Meluhhan merchants trading in copper and tin. The Meluhha merchant carries melh,mr̤eka 'goat or antelope' rebus: milakkhu 'copper and the lady accompanying the Meluhhan carries a ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin'; On the field is shown a crucbile:

Apparently, the Meluhhan is the person carrying the antelope on his arms. I also suggest that on the Shu-ilishu cylinder seal, a significant hieroglyph is shown. It is a crucible which may have been used by the copper-tin artisans to work with an extraordinary invention called ukku in Kannada produced in a crucible. I suggest that Kannada word ukku is the root word because of semantic association signified by cognate words: uggi, urika which mean 'burning'. Crucible steel process is vividly explained by these etyma. "Another Akkadian text records that Lu-sunzida “a man of Meluhha” paid to the servant Urur, son of AmarluKU 10 shekels of silver as a payment for a tooth broken in a clash. The name Lu-sunzida literally means “Man of the just buffalo cow,” a name that, although rendered in Sumerian, according to the authors does not make sense in the Mesopotamian cultural sphere, and must be a translation of an Indian name." (MASSIMO VIDALE Ravenna Growing in a Foreign World: For a History of the “Meluhha Villages” in Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium BC Published in Melammu Symposia 4: A. Panaino and A. Piras (eds.), Schools of Oriental Studies and the Development of Modern Historiography. Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Symposium of the Assyrian and Babylonian Intellectual Heritage Project. Held in Ravenna, Italy, October 13-17, 2001 (Milan: Università di Bologna & IsIao 2004), pp. 261-80. Publisher: http://www.mimesisedizioni.it/)

https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/201402/Vidale-Indus-Mesopotamia.pdf

The 1977 paper of Simo Parpola et al reviews texts containing references to Meluhha and Meluhhans, focussing on 9 texts dated to Ur III times (22nd to 21st cent. BCE) and included references to Sargonic texts (24th to 23rd cen. BCE). (Parpola S., A. Parpola & R.H. Brunswig, Jr. (1977) “The Meluhha Village. Evidence of acculturation of Harappan traders in the late Third Millennium Mesopotamia.” Journal of Economic and Social History of the Orient, 20, 129-165.)

Massimo Vidale provides a succint summary of the general picture presented in the paper of Simo Parpola et al. The surprising references relate to the fact that metals like gold, silver and tin were imports from Meluhha and involved Meluhhan settlers in Ancient Far East. "The maximum archaeological evidence of Indian imports and Indusrelated artefacts in Mesopotamia may be dated to latest phases of ED III (at the Royal Cemetery of Ur) and immediately later to the Akkadian period, when, as widely reported, Sargon claimed with pride that under his power Meluhhan ships docked at his capital, and at least one tablet mentions a person with an Akkadian name qualified as a “the holder of a Meluhha ship.”… (pp.262, 263)… according to the literary sources, between the end of the 3rd and the beginning of the 2nd millennium BC Meluhhan ships exported to Mesopotamia precious goods among which exotic animals, such as dogs, perhaps peacocks, cocks, bovids, elephants (? Collon 1977) precious woods and royal furniture, precious stones such as carnelian, agate and lapislazuli, and metals like gold, silver and tin (among others Pettinato 1972; During Caspers 1971; Chakrabarti 1982, 1990; Tosi 1991; see also Lahiri 1992 and Potts 1994). In his famous inscriptions, Gudea, in the second half of the 22nd century BC, states that Meluhhans came with wood and other raw materials for the construction of the main temple in Lagash (see Parpola et al. 1977: 131 for references). Archaeologically, the most evident raw materials imported from India are marine shell, used for costly containers and lamps, inlay works and cylinder seals; agate, carnelian and quite possibly ivory. Hard green stones, including garnets and abrasives might also have been imported from the Subcontinent and eastern Iran (Vidale & Bianchetti 1997, 1998-1999; Heimpel et al. 1988; Vidale 2002; see also Collon 1990, Tallon 1995 and Sax 1991). Carnelian could have been imported in form of raw nodules of large size (as implied by some texts) to be transformed into long beads, or as finished products. As we shall see, recent studies would better suggest that the Indus families in Mesopotamia imported raw materials rather than finished beads (Kenoyer 1997; Kenoyer & Vidale 1992; Inizan 2000), and expediently adapted their production to the changing needs of the Mesopotamian demand and markets. To the same period is ascribed a famous cylinder seal owned by a certain Su-ilisu, “Meluhha interpreter” (Sollberger 1970; Tosi 1991). Another Akkadian text records that Lu-sunzida “a man of Meluhha” paid to the servant Urur, son of AmarluKU 10 shekels of silver as a payment for a tooth broken in a clash. The name Lu-sunzida literally means “Man of the just buffalo cow,” a name that, although rendered in Sumerian, according to the authors does not make sense in the Mesopotamian cultural sphere, and must be a translation of an Indian name…… the Mesopotamian demand and markets. To the same period is ascribed a famous cylinder seal owned by a certain Su-ilisu, “Meluhha interpreter” (Sollberger 1970; Tosi 1991). Another Akkadian text records that Lu-sunzida “a man of Meluhha” paid to the servant Urur, son of AmarluKU 10 shekels of silver as a payment for a tooth broken in a clash. The name Lu-sunzida literally means “Man of the just buffalo cow,” a name that, although rendered in Sumerian, according to the authors does not make sense in the Mesopotamian cultural sphere, and must be a translation of an Indian name." (MASSIMO VIDALE Ravenna Growing in a Foreign World: For a History of the “Meluhha Villages” in Mesopotamia in the 3rd Millennium BC Published in Melammu Symposia 4: A. Panaino and A. Piras (eds.), Schools of Oriental Studies and the Development of Modern Historiography. Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Symposium of the Assyrian and Babylonian Intellectual Heritage Project. Held in Ravenna, Italy, October 13-17, 2001 (Milan: Università di Bologna & IsIao 2004), pp. 261-80. Publisher: http://www.mimesisedizioni.it/)

Among the imports from Meluhha into the Ancient Near East, the imports of silver and tin metals are significant because these two metals were the principal engines of the Tin-Bronze Revolution from 5th millennium BCE and for laying the foundations of monetary systems based on currency-based transactions which emerged in 7th century BCE with the Lydia electrum coins and Aegean Turtle silver staters of 480 to 457 BCE.

Massimo Vidale, 2017, A “Priest King” at Shahr-i Sokhta? in: Archaeological Research in Asia The paper discusses the published fragment of a statuette made of a buff-grey limestone, recently found on the surface of Shahr-i Sokhta (Sistan, Iran) and currently on exhibit in a showcase of the archaeological Museum of Zahedan (Sistan-Baluchistan, Iran). Most probably, it belongs to a sculptural type well known in some sites of Middle and South Asia dating to the late 3rd-early 2nd millennium BCE - a male character sitting on the right heel, with the left hand on the raised left knee, and a robe leaving bare the left shoulder.

Images of Zahedan torso (Shahr-i-Sokhta):

This article is discussed in the monograph:

A 'Priest King' at Shahr-i Sokhta? -- Massimo Vidale. Some images of Potr̥, 'priests' as dhāvaḍa 'smelters' Indus Script hypertexts

Other pronunciation variants for the word meluhha are: milakkha, milakkhuka 'a regional dialect speaker, explained as "Andha -- Damil'ādi."; milakkhu 'copper', milāca 'a wild man of woods' (Pali) mleccha- inmleccha-mukha 'copper'; mleccha 'a person who lives by agriculture or by making weapons' (Samskrtam). Milakkha [cp. Ved. Sk. mleccha barbarian, root mlecch, onomat. after the strange sounds of a foreign tongue, cp. babbhara & mammana] a barbarian, foreigner, outcaste, hillman S v. 466; J vi. 207; DA i. 176; SnA 236 (˚mahātissa -- thera Np.), 397 (˚bhāsā foreign dialect). The word occurs also in form milakkhu (q. v.).Milakkhu [the Prk. form (A -- Māgadhī, cp. Pischel, Prk. Gr. 105, 233) for P. milakkha] a non -- Aryan D iii. 264; Th 1, 965 (˚rajana "of foreign dye" trsl.; Kern, Toev. s. v. translates "vermiljoen kleurig"). As milakkhuka at Vin iii. 28, where Bdhgh expls by "Andha -- Damil'ādi."Milāca [by -- form to milakkha, viâ *milaccha>*milacca> milāca: Geiger, P.Gr. 622 ; Kern, Toev. s. v.] a wild man of the woods, non -- Aryan, barbarian J iv. 291 (not with C.=janapadā), cp. luddā m. ibid., and milāca -- puttā J v. 165 (where C. also expls by bhojaputta, i. e. son of a villager).(Pali) म्लेच्छ m. a foreigner , barbarian , non-Aryan , man of an outcast race , any person who does not speak Sanskrit and does not conform to the usual Hindu institutions S3Br. &c (f(ई); a person who lives by agriculture or by making weapons L.; ignorance of Sanskrit , barbarism Nyāyam. Sch.; n. copper L.; vermillion.)

In the reviews of ancient languages of India, Prakrit is linked with many dialects. One such dialect is Paiśācī which could also have the characteristic mis-pronunciations of words which are labeled 'mleccha'. The mleccha, according to Mahābhārata are located all over ancient India and are active participants in the events recorded in the Great Epic. One Paiśācī language work is attested in Jaina Maharashtri dialect (cf. a fragmentary text discussed by Alfred Master). Thus, languages such as Paiśācī, Pali, Ardhamāgadhi, Jaina Maharashtri can be clubbed under the group called 'mleccha' (with mis-pronounced words and ungrammatical expressions in local speech parlance). Such dialects are seen as Indian sprachbund (speech union) with links to literary forms attests in ancient texts in Samskrtam and Chandas. Some linguists also see links between Paiśācī and Gondi (with speakers in in the present-day states of Madhya Pradesh, Gujarat, Telangana, Maharashtra, Chhattisgarh, Andhra Pradesh). Links of Ardhamāgadhi with Munda, Santali, Mon-Khmer languages are also attested.

Ardhamagadhi Prakrit was a Middle Indo-Aryan language and a Dramatic Prakrit thought to have been spoken in modern-day Uttar Pradesh and used in some early Buddhism and Jainism. It was likely a Central Indo-Aryan language, related to Pali and the later Sauraseni Prakrit.[3]

It was originally thought to be a predecessor of the vernacular Magadhi Prakrit, hence the name (literally "half-Magadhi").

Theravada Buddhist tradition has long held that Pali was synonymous with Magadhi and there are many analogies between it and an older form of Magadhi called Ardhamāgadhī "Proto-Magadhi" -- derivative from Prakrit. Ardhamāgadhī was prominently used by Jain scholars (Constance Jones; James D. Ryan (2006). Encyclopedia of Hinduism. Infobase Publishing. p. 42.) and is preserved in the Jain Agamas. Both Gautama Buddha and the tirthankara Mahavira preached in Magadha.

Other Prakrits, such as Paiśācī, are reported in old historical sources but are not attested. "The most widely known work, although lost, attributed to be in Paiśācī is the Bṛhatkathā (literally "Big Story"), a large collection of stories in verse, attributed to Gunadhya. It is known of through its adaptations in Sanskrit as the Kathasaritsagara in the 11th century by Somadeva, and also from the Bṛhatkathā by Kshemendra. Both Somadeva and Kshemendra were from Kashmir where the Bṛhatkathā was said to be popular." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paishachi The 13th-century Tibetan historian Buton Rinchen Drub wrote that the early Buddhist schools were separated by choice of sacred language: the Mahāsāṃghikas used Prākrit, the Sarvāstivādins used Sanskrit, the Sthaviravādins used Paiśācī, and the Saṃmitīya used Apabhraṃśa.(Yao, Zhihua. The Buddhist Theory of Self-Cognition. 2012. p. 9).

":The term Prakrit, which includes Pali, is also used as a cover term for the vernaculars of North India that were spoken perhaps as late as the 4th to 8th centuries, but some scholars use the term for the entire Middle Indo-Aryan period. Middle Indo-Aryan languages gradually transformed into Apabhraṃśa dialects, which were used until about the 13th century. The Apabhraṃśas later evolved into Modern Indo-Aryan languages."(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Apabhraṃśa)

Prakrits (/ˈprɑːkrɪt/; Sanskrit: प्राकृत prākṛta; Shauraseni: pāuda; Jain Prakrit: pāua) are classified as Middle-Indo-Aryan spoken languages. "The phrase "Dramatic Prakrits" often refers to three most prominent of them: Shauraseni, Magadhi Prakrit, and Maharashtri Prakrit. However, there were a slew of other less commonly used Prakrits that also fall into this category. These include Pracya, Bahliki, Daksinatya, Sakari, Candali, Sabari, Abhiri, Dramili, and Odri. There was a strict structure to the use of these different Prakrits in dramas. Characters each spoke a different Prakrit based on their role and background; for example, Dramili was the language of "forest-dwellers", Sauraseni was spoken by "the heroine and her female friends", and Avanti was spoken by "cheats and rogues" (Banerjee, Satya Ranjan. The Eastern School of Prakrit Grammarians : a linguistic study. Calcutta: Vidyasagar Pustak Mandir, 1977, pp.19-21) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prakrit

Sten Konow, ("181 [95] - The home of the Paisaci - The home of the Paisaci - Page - Zeitschriften der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft - MENAdoc – Digital Collections". menadoc.bibliothek.uni-halle.de) Felix Lacôte ( Félix Lacôte (4 March 2018). "Essai sur Guṇāḍhya et la Bṛhatkathā") & Alfred Master have explained that Paiśācī was the ancient name for Pāli, the language of the Pāli Canon of Theravada Buddhism.(See embedded monograph on a fragment of Paiśācī): Alfred Master, 1948, An Unpublished Fragment of Paiśācī in: Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies,University of London, Vol. 12,No. 3/4, Oriental and African Studies Presented to Lionel David Barnett by His Colleagues, Past and Present (1948), pp. 659-667

Standard of Mari. The standard-bearer has a shaven face and head. The staff upholding the one-horned young bull is खोंड a variety of jōndhaḷā Holcus sorghum; the hieroglyph signifies karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'.

Standard of Mari. The standard-bearer has a shaven face and head. The staff upholding the one-horned young bull is खोंड a variety of jōndhaḷā Holcus sorghum; the hieroglyph signifies karba 'culm of millet' rebus: karba 'iron'. Hoe: Ta. kuntāli, kuntāḷi pickaxe. Ma. kuntāli, kūntāli id. Kurub. (LSB 1.11) kidli a spade. Ko. kuda·y hoe.

Ka. guddali, gudli a kind of pickaxe, hoe. Koḍ. guddali hoe with spade-like blade. Tu. guddali, guddoli, (B-K.) guddoḷi a kind of pickaxe; guddolipuni to dig with a pickaxe. Te. guddali, (VPK) guddili, guddela, guddēli, guddēlu a hoe; guddalincu to hoe. Nk. kudaḷ spade. Go. (G. Mu.) kudaṛ spade, axe; (Ma. M. Ko.) guddaṛ spade, hoe (Voc. 749); (LuS.) goodar hoe. Konḍa gudeli hoe-like instrument for digging. Malt. qodali a spade. Cf. 1719 Ta. kuttu. / Cf. Skt. kuddāla- spade, hoe; Turner, Stool, squat: Ta. kuntu (kunti-) to sit on the heels with legs folded upright, squat; n. sitting on the heels, squatting. Ma. kuttuka to squat, sit on one's heels. Ka. kuntu, kūtu having sat down. Tu. (B-K.) kutoṇu to sit. Te. gontu-gūrcuṇḍu to squat, sit with the soles of the feet fully on the ground and the buttocks touching it or close to it; kudikilu, kudikilãbaḍu to squat down; kundikāḷḷu, kundikundikāḷḷu a boys' game like leapfrog; kundē̆lu hare. Go. (Ko.) kud- to sit (Voc. 748); caus. (KoyaT.) kup-, (KoyaSu.) kuppis-; (many dialects) kuttul a stool to sit on (Voc. 745).(DEDR 1728) Rebus: kunda 'lapidary, metalworker setting gemstones in fine gold jewels'.

Triangula tablet. Horned seated person. crocodile. Split ellipse (parenthesis). On this tablet inscription, the hieroglyphs are: crocodile, fishes, person with a raised hand, seated in penance on a stool (platform). eraka 'raised hand' rebus: eraka 'molten cast, copper' arka 'copper'. manca 'platform' rebus: manji 'dhow, seafaring vessel' karA 'crocodile' rebus: khAr 'blacksmith'

dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'metal'. Thus, cast iron.

Hieroglyph: kamaḍha 'penance' (Prakrit) kamaḍha, kamaṭha, kamaḍhaka, kamaḍhaga, kamaḍhaya = a type of penance (Prakrit)

Rebus: kamaṭamu, kammaṭamu = a portable furnace for melting precious metals; kammaṭīḍu = a goldsmith, a silversmith (Telugu) kãpṛauṭ jeweller's crucible made of rags and clay (Bi.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Tamil)

kamaṭhāyo = a learned carpenter or mason, working on scientific principles; kamaṭhāṇa [cf. karma, kām, business + sthāna, thāṇam, a place fr. Skt. sthā to stand] arrangement of one’s business; putting into order or managing one’s business (Gujarati)

The composition of two hieroglyphs: kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) + kamaḍha 'a person seated in penance' (Prakrit) denote rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri); kāru ‘artisan’ (Marathi) + kamaṭa 'portable furnace'; kampaṭṭam 'coinage, coin, mint'. Thus, what the tablet conveys is the mint of a blacksmith. A copulating crocodile hieroglyph -- kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) + kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali) -- conveys the same message: mint of a blacksmith kāru kampaṭṭa 'mint artisan'.

m1429B and two other tablets showing the typical composite hieroglyph of fish + crocodile. Glyphs: crocodile + fish ayakāra ‘blacksmith’ (Pali) kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu) aya 'fish' (Munda) The method of ligaturing enables creation of compound messages through Indus writing inscriptions. kāru a wild crocodile or alligator (Telugu) Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri); kāru ‘artisan’ (Marathi).

Pali: ayakāra ‘iron-smith’. ] Both ayaskāma and ayaskāra are attested in Panini (Pan. viii.3.46; ii.4.10). WPah. bhal. kamīṇ m.f. labourer (man or woman) ; MB. kāmiṇā labourer (CDIAL 2902) N. kāmi blacksmith (CDIAL 2900).

Kashmiri glosses:

khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन्, which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta khāra-basta खार-बस््त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü -ब&above;ठू&below; । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy -बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer. -gȧji or -güjü - लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. (sg. dat. -höjü -हा&above;जू&below;), a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl 5. -kūrü लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. -koṭu - लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. -küṭü लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më˘ʦü 1 - लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see [khāra 3] ), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore. -nĕcyuwu लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see [khārun] ), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ । लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wānवान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 3). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil.

Thus, kharvaṭ may refer to an anvil. Meluhha kāru may refer to a crocodile; this rebus reading of the hieroglyph is.consistent with ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (Pali) [fish = aya (G.); crocodile = kāru (Telugu)]

Orthography of face of seated person on seal m0304 tvaṣṭṛ, ṭhaṭṭhāra 'smelter, brassworker', hypertexts on Indus Script Corpora signify iron smelters

I suggest that orthography of face of seated person on seal m0304 signifies tvaṣṭṛ, ṭhaṭṭhāra 'smelter, brassworker', so do similar hypertexts on Indus Script Corpora signify iron smelters

Sprout: Kui gunda (gundi-) to sprout, bud, shoot forth into bud or ear; n. a sprouting, budding. ? Kuwi (Isr.) kunda a very small plot of ground (e.g. for seed-bed). Kur. kundnā to germinate, bud, shoot out; kundrnā to be born; kundrkā birth; kundrta'<-> ānā to generate, beget, produce. Malt. kunde to be born, be created.(DEDR 1729) Rebus: kunda 'lapidary, metalworker setting gemstones in fine gold jewels'.

Source: Massimo Vidale, 2010, Aspects of palace life at Mohenjo-Daro, in: South Asian Studies, Vol. 16, No.1, pp. 59-76) https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Vidale_South_Asian_Studies.pdf

https://www.harappa.com/content/indus-seals-and-glyptic-studies-overview

https://www.scribd.com/document/386704685/Indus-Seals-and-Glyptic-studies-an-overview-Asko-Parpola-2017

Pillar with ringstones. Dholavira.

Pillar with ringstones. Dholavira.Alternative 1. Serpent (?) entwined around a pillar with capital (?); motif carvd in high-relief. Alternative 2. Ring-stones around a pillar with coping stones in a building-

Pillar: Ka. kunda a pillar of bricks, etc. Tu. kunda pillar, post. Te. kunda id. Malt. kunda block, log. ? Cf. Ta. kantu pillar, post.(DEDR 1723) Rebus: kunda 'lapidary, goldsmith setting gemstones'

Ringstone columns of Mohenjo-Daro are Indus Script Hypertexts, metalwork catalogues

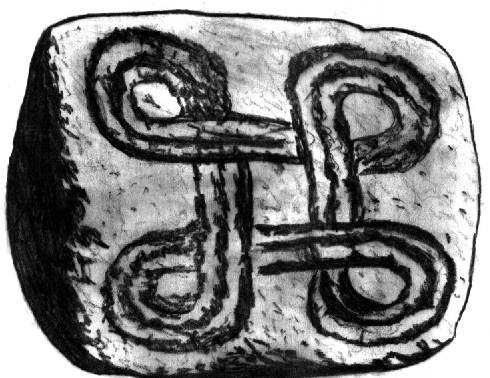

Indus Script Hypertext: pillar or ringstone column: meḍ(h) 'post' rebus medhā, 'yajña, nidhi, dhanam'. This hieroglyph is reinforced as a phonetic determinant, by the endless-knot motif on the reverse of the tablets.

Sign 342 kanka, karṇaka 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī '

d"Mackay's final interpretation was that ring-stones, as Cousins had suggested, were column segments, originally threaded onto an innter tapering wooden shaft.While the transversal dowel-holes fastened the stone to the inner shaft, the cup-marks were mason's devices used for planning the assemblage of the rings. He also proposed that the twenty-seven or twenty-eight rings belonged to two monumental columns made of fourteen segments each, whose height would have been near to 3.5 m...the few impressed terracotta tablets found at Mohenjo-Daro (Figure 7), bearing on both faces the same figures and most probably impressed after the same moulds or seals. All come from DK area. On one side they show a labyrinth-like cross and two signs. On the opposite face, they bear in high relief what I identify as the image of a column made of six superimposd ring-stones. The lowermost segments are thinner and flat, and I am tempted to identify them as a flat square base capped by a concave ring...Besides supporting the evidence of Dholavira, these rare tablets show the relevance of the symbol of the composite column in Indus iconography." (Massimo Vidale, 2010, Aspects of palace life at Mohenjo-Daro, in: South Asian Studies, Vol. 16, No.1, pp. 69-70)

Hieroglyph: pillar, post: mēthí m. ʻ pillar in threshing floor to which oxen are fastened, prop for supporting carriage shafts ʼ AV., ˚thī -- f. KātyŚr.com., mēdhī -- f. Divyāv. 2. mēṭhī -- f. PañcavBr.com., mēḍhī -- , mēṭī -- f. BhP. 1. Pa. mēdhi -- f. ʻ post to tie cattle to, pillar, part of a stūpa ʼ; Pk. mēhi -- m. ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, N. meh(e), miho, miyo, B. mei, Or. maï -- dāṇḍi, Bi. mẽh, mẽhā ʻ the post ʼ, (SMunger) mehā ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ, Mth. meh, mehā ʻ the post ʼ, (SBhagalpur) mīhã̄ ʻ the bullock next the post ʼ, (SETirhut) mẽhi bāṭi ʻ vessel with a projecting base ʼ.2. Pk. mēḍhi -- m. ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ, mēḍhaka<-> ʻ small stick ʼ; K. mīr, mīrü f. ʻ larger hole in ground which serves as a mark in pitching walnuts ʼ (for semantic relation of ʻ post -- hole ʼ see kūpa -- 2 ); L. meṛh f. ʻ rope tying oxen to each other and to post on threshing floor ʼ; P. mehṛ f., mehaṛ m. ʻ oxen on threshing floor, crowd ʼ; OA meṛha, mehra ʻ a circular construction, mound ʼ; Or. meṛhī, meri ʻ post on threshing floor ʼ; Bi. mẽṛ ʻ raised bank between irrigated beds ʼ, (Camparam) mẽṛhā ʻ bullock next the post ʼ, Mth. (SETirhut) mẽṛhā ʻ id. ʼ; M. meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.(CDIAL 10317)

गोटी [ gōṭī ] f (Dim. of गोटा) A roundish stone or pebble. गोदा [ gōdā ] m A circular brand or mark made by actual cautery (Marathi)गोटा [ gōṭā ] m A roundish stone or pebble. 2 A marble (of stone, lac, wood &c.) 2 A marble. 3 A large lifting stone. Used in trials of strength among the Athletæ. 4 A stone in temples described at length underउचला 5 fig. A term for a round, fleshy, well-filled body. 6 A lump of silver: as obtained by melting down lace or fringe. गोटुळा or गोटोळा [ gōṭuḷā or gōṭōḷā ] a (गोटा) Spherical or spheroidal, pebble-form. (Marathi)

·

· Rebus: krvṛi f. ‘granary (WPah.); kuṛī, kuṛo house, building’(Ku.)(CDIAL 3232) कोठी [ kōṭhī ] f (कोष्ट S) A granary, garner, storehouse, warehouse, treasury, factory, bank. (Marathi)

· कोठी The grain and provisions (as of an army); the commissariatsupplies. Ex. लशकराची कोठी चालली-उतरली- आली-लुटली. कोठ्या [ kōṭhyā ] कोठा [ kōṭhā ] m (कोष्ट S) A large granary, store-room, warehouse, water-reservoir &c. 2 The stomach. 3 The chamber of a gun, of water-pipes &c. 4 A bird's nest. 5 A cattle-shed. 6 The chamber or cell of a hunḍí in which is set down in figures the amount. कोठारें [ kōṭhārēṃ ] n A storehouse gen (Marathi)

https://tinyurl.com/ycfsgwdv

meḍhi 'plait, twist' Rupaka, 'metaphor' or rebus reading:: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) मृदु mṛdu, mẽṛhẽt 'iron' (Samskrtam. Santali) med 'copper' (Slavic languages) मेधा 'धन' Naigh. ii , 10; yajña. These metaphors explain why the endless knot motif adorns a copper plate inscription.

(Samskrtam.Santali)![Image result for copper plate endless knotmotif]()

A new copper plate of Dhruva II of the Gujarat Rashtrakuta branch, datedsaka 806 (AS Altekar,Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XXII, 1933-34, pp. 64-76). The endless knot motif signifies: meḍhi 'plait, twist' Rupaka, 'metaphor' or rebus reading: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic languages) मेधा धन Naigh. ii , 10; yajña.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00040/salon.html

meḍhi 'plait, twist' Rupaka, 'metaphor' or rebus reading:: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) मृदु mṛdu, mẽṛhẽt 'iron' (Samskrtam. Santali) med 'copper' (Slavic languages) मेधा 'धन' Naigh. ii , 10; yajña. These metaphors explain why the endless knot motif adorns a copper plate inscription.

(Samskrtam.Santali)

A new copper plate of Dhruva II of the Gujarat Rashtrakuta branch, datedsaka 806 (AS Altekar,Epigraphia Indica, Vol. XXII, 1933-34, pp. 64-76). The endless knot motif signifies: meḍhi 'plait, twist' Rupaka, 'metaphor' or rebus reading: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic languages) मेधा धन Naigh. ii , 10; yajña.

Figures 1-4"Another interesting motif from a BMAC seal which can be followed through the centuries is the endless knot (Fig. 1)(After: Sarianidi, V. I., Bactrian Centre of Ancient Art, Mesopotamia, 12 / 1977, Fig. 59 / 18). It reappears on mediaeval metalwork (Bowl, Khorasan, early 13th century in: Melikian-Chirvani, A. S., Islamic Metalwork from the Iranian World, London, 1982, No. 26.), and together with the interlaced motif of the seal from Fig. 2 on a 14th century Italian painting depicting an Anatolian carpet (Erdmann, K., Der orientalische Knüpfteppich, Tübingen, 2. Aufl, 1960, Abb. 18). Additionally, it can be seen on a very important carpet from eastern Anatolia, now in the Vakiflar Museum in Istanbul(Balpinar, B.,Hirsch, U.,Vakiflar Museum Istanbul II: Teppiche - Carpets, Wesel, 1988, Pl. 62), as well as on many 19thcentury Lori- and Bakhtiari weavings (Opie, J., Tribal Rugs, London, 1992, Fig. 4.16) Another seal includes the kind of endless knot ornament (Sarianidi, V. I., Soviet Excavations in Bactria: The Bronze Age, Fig. 11 / 9, in: Ligabue, G., Salvatori, S., eds., Bactria An ancient oasis civilization from the sands of Afghanistan, Venice, 1990) that is part of the Chinese symbol of happiness (Opie, J., Tribal Rugs, London, 1992, Fig. 4.11), connects the medallions on a 12th century bronze kettle from Samarqand (von Gladis, A., Islamische Metallarbeiten des 9. bis 15. Jahrhunderts, Abb. 219, in: Kalter, J., Pavaloi, M., eds., Usbekistan, Stuttgart, 1995), on a group of East Anatolian carpets from the 15th century (Balpinar, B.,Hirsch, U.,Vakiflar Museum Istanbul II: Teppiche - Carpets, Wesel, 1988, Pl. 37), and on carpets in Timurid miniatures (Briggs, A., 1940, cited in: Pinner, R., Franses, M., Two Turkoman Carpets of the 15th century, in: Turkoman Studies I, London, 1980, Fig. 130)."

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00040/salon.html

Haystack, heap of straw: Ta. kuntam haystack. Ka. kuttaṟi a stack, rick.(DEDR 1724)kuṇḍa3 n. ʻ clump ʼ e.g. darbha -- kuṇḍa -- Pāṇ. [← Drav. (Tam. koṇṭai ʻ tuft of hair ʼ, Kan. goṇḍe ʻ cluster ʼ, &c.) T. Burrow BSOAS xii 374]Pk. kuṁḍa -- n. ʻ heap of crushed sugarcane stalks ʼ; WPah. bhal. kunnū m. ʻ large heap of a mown crop ʼ; N. kunyũ ʻ large heap of grain or straw ʼ, baṛ -- kũṛo ʻ cluster of berries ʼ.(CDIAL 3266) *kuṇḍaka ʻ husks, bran ʼ.Pa. kuṇḍaka -- m. ʻ red powder of rice husks ʼ; Pk. kuṁḍaga -- m. ʻ chaff ʼ; N. kũṛo ʻ boiled grain given as fodder to buffaloes ʼ, kunāuro ʻ husk of lentils ʼ (for ending cf. kusāuro ʻ chaff of mustard ʼ); B. kũṛā ʻ rice dust ʼ; Or. kuṇḍā ʻ rice bran ʼ; M. kũḍā, kõ˚ m. ʻ bran ʼ; Si. kuḍu ʻ powder of paddy &c. ʼAddenda: kuṇḍaka -- in cmpd. kaṇa -- kuṇḍaka -- Arthaś.(CDIAL 3267)कोंडा kōṇḍā m Bran, husk of corn gen. 2 fig. Miliary scab, scurf. 3 fig. Rash, any efflorescence on the body. 4 A small kind of bamboo. 5 Commonly कोंयंडा. कोंड्याचा मांडा करणें To make, by culinary skill, a savory dish out of coarse materials. कोंडेकड kōṇḍēkaḍa n A cake composed of rice-bran well peppered and salted.(Marathi)

Bow: Kol. (Kin.) gunti bow. Go. (A.) gunti, (S.) gunṭi id.; (Ma.) guncili pellet-bow (Voc. 1132). Pe. guṇci, guṇca id. Kur. guṛthā, gunthā id. Malt. guṉṛta id.(DEDR 1727)

कुन्द m. ( Un2. iv , 101) a kind of jasmine (Jasminum multiflorum or pubescens) MBh. &c; n. the jasmine flower (Monier-Williams).

SumerSumer was first permanently settled between c. 5500 and 4000 BCE. Bhirrana-Kunal and Mehrgarh date to 8th m. BCE.

![No photo description available.]() I have suggested a rebus reading of the curious flagpost carried in a procession by a priest of Mari. The reading is based on Meluhha linguistics (Indian sprachbund'language union' words. This clearly shows that Meluhha people had moved into Mari and celebrated their competence in metalwork signified by the one-horned young bull: khonda 'holcus sorghum' khonda 'young bull' rebus: kond 'kiln', kundar, 'turner' kundana 'fine gold' PLUS karba 'stalk of millet' (holcus sorghum) rebus: karba 'iron'. The proclamation message of the procession is that the gold workers have started working with iron,another metalwork wealth category.

I have suggested a rebus reading of the curious flagpost carried in a procession by a priest of Mari. The reading is based on Meluhha linguistics (Indian sprachbund'language union' words. This clearly shows that Meluhha people had moved into Mari and celebrated their competence in metalwork signified by the one-horned young bull: khonda 'holcus sorghum' khonda 'young bull' rebus: kond 'kiln', kundar, 'turner' kundana 'fine gold' PLUS karba 'stalk of millet' (holcus sorghum) rebus: karba 'iron'. The proclamation message of the procession is that the gold workers have started working with iron,another metalwork wealth category.

![No photo description available.]()

Frieze of a mosaic panel Circa 2500-2400 BCE Temple of Ishtar, Mari (Tell Hariri), Syria Shell and shale André Parrot excavations, 1934-36 AO 19820 panel depicts proclamation of metalwork competence ofkonda, 'one-horned young bull' (rebus kō̃da कोँद 'potter's kiln') from Tell Hariri, ancient Mari, Temple of Ishtar -- graduating from gold to iron. The contacts with Meluhha (Sarasvati_Sindhu Civilization area) during the mature phase of the civilization are suggested by the date of the mosaic panel, ca. 2500 BCE.

I suggest that the priest shown on the Mari frieze mosaic panel is sanga 'priest' a word derived from Gujarati word sanghvi. saṅgin ʻ attached to, fond of ʼ MBh. [saṅgá -- ]Pk. saṁgi -- , saṁgilla -- ʻ attached to ʼ; S. L. P. saṅgī m. ʻ comrade ʼ (P. also ʻ one of a party of pilgrims ʼ), N. saṅi, Or. sāṅga, ˚gī, H. saṅgī m., M. sãgyā, sāgyā m.Addenda: saṅgin -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) sɔ́ṅgi m. ʻ friend ʼ, kṭg. sɔ́ṅgəṇ, kc. sɔṅgiṇ f., J. saṅgī, saṅgu m. (prob. ← H. Him.I 212)(CDIAL 13084)

Substrate sanga 'priest' in Sumerian is from sangvi 'priest' (Gujarati)

Jerald Jack Starr Nashville, Tennessee has set up a http://sumerianshakespeare.com portal to establish that the people of Mari of ca. 3rd millennium BCE and the Sumerians are the same people.

The trade contacts of Meluhha with Sumer is firmly anchored by the decipherment of the Susa pot Indus Script hypertexts.

![]() Sb 2723 (After Harper, Prudence Oliver, Joan Aruz, Francoise Tallon, 1992, The Royal city of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre, Metropolitan Musem of Art, New York.)

Sb 2723 (After Harper, Prudence Oliver, Joan Aruz, Francoise Tallon, 1992, The Royal city of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre, Metropolitan Musem of Art, New York.)![]()

![]()

![]()

Sargon (2334-2279 BCE) founded the Akkad dynasty which saw inter-regional trade routes, from Dilmun and Magan to Susa and Ebla. Later Naram-Sin (c. 2254-2218 BCE) conquered the cities of Mari and Ebla. Agade of Sargon boasted of gold, tin and lapis lazuli brought from distant lands. A description (Kramer, Samuel Noah, 1958: History Begins at Sumer (London: Thames & Hudson, 289-290) reads:

When Enlil had given Sargon, king of Agade,

Sovereignty over the high lands and over the low lands

...

under the loving guidance of its divine patron Inanna.

Its houses filled with gold, silver, copper, tin, lapis lazuli;

...

The Martu (Amorites) came there, that nomadic people from the west,

'who know not wheat' but who bring oxen and choice sheep;

The folk from Meluhha came, 'the peole of the black lands',

Bearing their exotic products;

The Elamites came and the Sabareans, peoples from the East and the North,

With their bundles like 'beasts of burden'...

In this narrative, Meluhha folk from the black lands were those who required a translator. (Se Shu-ilishu cylinder seal of an Akkadian translator).

See:

Unfortunately, archaeological work has not been done on the so-called Stupa at Mohenjo-daro. I suggest that this is a ziggurat and compares with the ziggurat at the ancient city of Mari.

![Ruins of ziggurat n ancient city of Mari.]()

Ruins of ziggurat in ancient city of Mari. Mari, Syria - a ziggurat near the palace. "Mari was an ancient Semitic city in modern-day Syria. Its remains constitute a tell located 11 kilometers north-west of Abu Kamal on the Euphrates river western bank, some 120 kilometers southeast of Deir ez-Zor. It flourished as a trade center and hegemonic state between 2900 BCE and 1759 BCE. As a purposely-built city, the existence of Mari was related to its position in the middle of the Euphrates trade routes; this position made it an intermediary between Sumer in the south and the Levant in the west."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gala_(priests)

I suggest that this Ziggurat of Mari is derived from the Ziggurat of Mohenjo-daro (referred to as 'stupa'). Both the Ziggurat of Mari and the stupa of Mohenjo-daro compare with the stepped pyramid shown on Sit Shamshi bronze.

![Image result for ziggurat mohenjo-daro]()