--Together, کار کنده kār-kundaʿh 'director of metalwork manufactories' of ancient India and Sumer

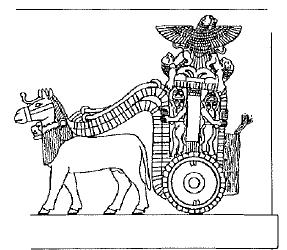

Erwin Neumayer presents compelling evidence of animal-drawn chariots on chalcolithic rock art of many sites from ancient India (samples appended).-- khara, 'Onager' together with khōṇḍa 'young bull-calf' are Indus Script hieroglyphic signifiers khār'blacksmith' PLUS kunda'turner, lapidary'; thus, together کار کنده kār-kundaʿh 'director of metalwork manufactories'. -- tã̄bṛā 'carnelian', tanbura 'harp, lyre' rebus tambra 'copper', rathī रथी 'leader', ratha, 'chariot', khara, 'onagers', rebus کار kār 'professional'کار کنده kār-kundaʿh 'director', khār 'blacksmith' of Indian and Sumerian art-- Carnelian, tã̄bṛā, tāmṛā 'stone resembling māṇikya, a ruby' from Gujarat found in Ancient Near East sites, 3rd m.BCE-- څرخ ṯs̱arḵẖ, s.m. (2nd) A wheel (particularly a potter's, or of a water-mill or well). 2. A grindstone. 3. Circular motion, turn, revolution, the act of turning. rebus: څرخ ṯs̱arḵẖ, s.m. (2nd) (P چرخ ). 2. A wheeled-carriage, a gun-carriage, a cart. Pl. څرخونه ṯs̱arḵẖūnah. -- Daimabad ratha, 'chariot', khara, 'onagers' of Sumerian chariot, ca. 2600 BCE

-- रथ्य n. carriage equipments (trappings , a wheel &c ) RV. La1t2y. rathin रथिन् A warrior who fights from a chariot; आत्मानं रथिनं विद्धि शरीरं रथमेव तु । बुद्धिं तु सारथिं विद्धि मनः प्रग्रहमेव च ॥ Kaṭha Up.1.3.3; R.7.37 rathī रथी Ved. 1 Riding in a chariot. -2 Furnished with a carriage. -3 A coachman. -4 A guide, leader.-- khara खर -रः 1 An ass, Ms.2.21; 4.115,12,8.37; Y.2.16. -2 A mule.-यानम् a donkey-cart; Ms.11.21. -शब्दः 1 the braying of an ass. -शाला a stable for asses. khara1 m. ʻ donkey ʼ KātyŚr., ˚rī -- f. Pāṇ.NiDoc. Pk. khara -- m., Gy. pal. ḳăr m., kắri f., arm. xari, eur. gr. kher, kfer, rum. xerú, Kt. kur, Pr. korūˊ, Dm. khar m., ˚ri f., Tir. kh*l r, Paš. lauṛ. khar m., khär f., Kal. urt. khār, Phal. khār m., khári f., K. khar m., khürü f., pog. kash. ḍoḍ. khar, S. kharu m., P. G. M. khar m., OM. khari f.; -- ext. Ash. kərəṭék, Shum. xareṭá; <-> L. kharkā m., ˚kī f. -- Kho. khairánu ʻ donkey's foal ʼ (+?).*kharapāla -- ; -- *kharabhaka -- .Addenda: khara -- 1 : Bshk. Kt. kur ʻ donkey ʼ (for loss of aspiration Morgenstierne ID 334).(CDIAL 3818) Rebus: khara 'quick and nimble' (A.); WPah. bhad. kharo ʻ good ʼ, paṅ. cur. cam. kharā ʻ good, clean ʼ; Ku. kharo ʻ honest ʼ; N. kharo ʻ real, keen ʼ(CDIAL 3819) Semantic expansions: P کار kār, s.m. (2nd) Business, action, affair, work, labor, profession, operation. Pl. کارونه kārūnah. (E.) کار آرموده .چار kār āzmūdah. adj. Experienced, practised, veteran. کار و بار kār-o-bār, s.m. (2nd) Business, affair. Pl. کار و بارونه kār-o-bārūnah. کار خانه kār- ḵẖānaʿh, s.f. (3rd) A manufactory, a dock- yard, an arsenal, a workshop. Pl. يْ ey. کاردیده kār-dīdah, adj. Experienced, tried, veteran. کار روائي kār-rawā-ī, s.f. (3rd) Carrying on a business, management, performance. Pl. ئِي aʿī. کار زار kār-zār, s.m. (2nd) Battle, conflict. Pl. کار زارونه kār-zārūnah. کار ساز kār-sāz, adj. Adroit, clever; (Fem.) کار سازه kār-sāzaʿh. کار ساري kār-sāzī, s.f. (3rd) Cleverness, adroitness. Pl. ئِي aʿī. کار کند kār-kund(corrup. of P کار کن ) adj. Adroit, clever, experienced. 2. A director, a manager; (Fem.) کار کنده kār-kundaʿh. کار کول kār kawul, verb trans. To work, to labor, to trade.(Pashto) khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) खारवी khāravī m A caste or an individual of it. They are employed in ships and boats along the coast, in tiling houses, in plantation-business &c.खारसंध khārasandha m (खार & सांधा) Metallic cement, solder.खारसळई khārasaḷī f The stone upon which खार is levigated in preparing खारसंध or metallic cement.

![Model of a two-wheeled Sumerian chariot, with chariot rein post and rings. The model of the chariot shows the image of a god on its interior.panel.It is from a later period (Neo-sumerian,ca 2000 BC):]() Model of a two-wheeled Sumerian chariot, with chariot rein post and rings. The model of the chariot shows the image of a god on its interior.panel.It is from a later period (Neo-sumerian,ca 2000 BCE)

Model of a two-wheeled Sumerian chariot, with chariot rein post and rings. The model of the chariot shows the image of a god on its interior.panel.It is from a later period (Neo-sumerian,ca 2000 BCE)

"Chariots figure prominently in the Rigveda, evidencing their presence in India in the 2nd millennium BCE. Notably, the Rigveda differentiates between the Ratha (chariot) and the Anas (often translated as "cart").[2] Rigvedic chariots are described as made of the wood of Salmali (RV 10.85.20), Khadira and Simsapa (RV 3.53.19) trees. While the number of wheels varies, chariot measurements for each configuration are found in the Shulba Sutras.Chariots also feature prominently in later texts, including the other Vedas, the Puranas and the great Hindu epics (Ramayana andMahabharata). Indeed, most of the deities in the Hindu pantheon are portrayed as riding them. Among Rigvedic deities, notablyUshas (the dawn) rides in a chariot, as well as Agni in his function as a messenger between gods and men. In RV 6.61.13, the Sarasvati river is described as being wide and speedy, like a (Rigvedic) chariot." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ratha

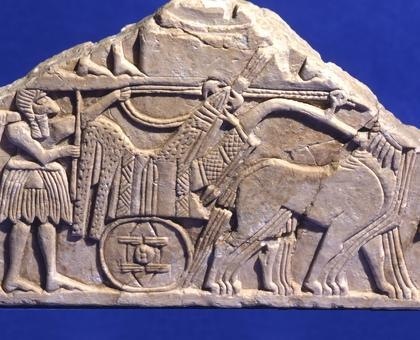

The style of the chariot box of Harappa (with an X on the siges) compares with the war chariot of Sumer.![Image result for chariot box harappa]() Daimabad. Charioteer.

Daimabad. Charioteer.

![Image result for chariot box harappa]()

Daimabad chariot drawn by two zebu, charioteer.

![]() Bronze chariot boxes. Harappa. Chanhudaro. Copper model of a passenger box on a cart, Chanhudaro, ca. 2,000 BCE. Source for Picture 27.2 of Harappa copper model: Figure 35 from Excavations at Harappa by MS Vats, 1940. “Two types of two-wheeled carts are represented. The first one has curved platform with holes for uprights (Mohenjo-daro, Chanhu-daro). The second one has a seat placed over the axle (bronze model from Chanhu-daro)(Mackay, 1951: 97, pl. xxi:13; ; xix:1; Piggott 1970: 200-202; Allchins 1973: fig.30). (loc.cit. Elena Efimovna Kuz’mina, 2007, The origin of the Indo-Iranians, BRILL., p.336).” रथ m. ( √4. ऋ) " goer " , a chariot , car , esp. a two-wheeled war-chariot (lighter and swifter than the अनस् q.v.) , any vehicle or equipage or carriage (applied also to the vehicles of the gods) , waggon , cart RV. &c (ifc.f(आ).)(Monier-Williams) rátha m. ʻ chariot, cart ʼ RV. Pa. ratha -- , °aka -- m., Pk. OG. raha -- (Pk. m.n.); Si. riya ʻ waggon, carriage ʼ; -- ext. -- ḍ -- : L. rēhṛā m. ʻ handcart ʼ; P. rehṛā, rihṛā m., °ṛī f. ʻ cart ʼ; H. rahṛū,rẽhṛū m. ʻ light open cart with one seat ʼ; -- with -- l -- : P. rahilā m., °lī f. ʻ cart ʼ.(CDIAL 10602)

Bronze chariot boxes. Harappa. Chanhudaro. Copper model of a passenger box on a cart, Chanhudaro, ca. 2,000 BCE. Source for Picture 27.2 of Harappa copper model: Figure 35 from Excavations at Harappa by MS Vats, 1940. “Two types of two-wheeled carts are represented. The first one has curved platform with holes for uprights (Mohenjo-daro, Chanhu-daro). The second one has a seat placed over the axle (bronze model from Chanhu-daro)(Mackay, 1951: 97, pl. xxi:13; ; xix:1; Piggott 1970: 200-202; Allchins 1973: fig.30). (loc.cit. Elena Efimovna Kuz’mina, 2007, The origin of the Indo-Iranians, BRILL., p.336).” रथ m. ( √4. ऋ) " goer " , a chariot , car , esp. a two-wheeled war-chariot (lighter and swifter than the अनस् q.v.) , any vehicle or equipage or carriage (applied also to the vehicles of the gods) , waggon , cart RV. &c (ifc.f(आ).)(Monier-Williams) rátha m. ʻ chariot, cart ʼ RV. Pa. ratha -- , °aka -- m., Pk. OG. raha -- (Pk. m.n.); Si. riya ʻ waggon, carriage ʼ; -- ext. -- ḍ -- : L. rēhṛā m. ʻ handcart ʼ; P. rehṛā, rihṛā m., °ṛī f. ʻ cart ʼ; H. rahṛū,rẽhṛū m. ʻ light open cart with one seat ʼ; -- with -- l -- : P. rahilā m., °lī f. ʻ cart ʼ.(CDIAL 10602)

A conversation between a grammarian and a charioteer

"Indo-Aryan languages have a long history of transmission, not only in the form of literary works and treatises dealing with logical, philosophical, and ritual matters but also in phonetic, phonological, and grammatical descriptions. The languages are divisible into three major stages: Old-, Middle- and New- (or Modern-) Indo-Aryan. The first is represented by an enormously rich literature stretching over millennia, including Vedic texts and later literary works of various genres. In addition, we are privileged to have knowledge of the details of Old Indo-Aryan of different eras and areas through extraordinarily perceptive descriptions of phonetics and phonology relative to traditions of Vedic recitation in prAtizAkhya works and PANini's ASTAdhyAyI, the brilliant set of rules describing the language current at around the fifth century BCE, with important dialectical observations and contrasts drawn between the then current speech and earlier Vedic usage. Moreover, observations by YAska (possibly antedating PANini) and Patanjali (second century BCE) inform us about some dialect features of Old Indo-Aryan in early times...Speakers of Sanskrit were aware from early on not only of differences between their current language and Vedic but also of areal differences at a given time. Well known examples stem from YAska and Patanjali, who speak of usages proper to the Kamboja, SaurASTra, the east and midlands, as well as of Arya speakers. It is noteworthy that zav is said to occur in Kamboja, a northwestern people whom in his commentary on Nirukta 2.2 Durga refers to as Mleccha (Bhadkamkar 1918: 166.5-6: gatyartho dhAtuh kambojeSv eva bhASyate mleccheSu prakRtyA prayujyata AkhyAtapadabhAvena): zyav, zav, ziyav 'go' are used in Avestan and Old Persian...Patanjali refers to the use of hamm 'go' in SauRASTra. Another feature of the speech of this area is noted in the metrical version of the PANinIyazikSA, which says that nasalized vowels as in arAm 'spokes' of RV 8.77.3b (khe arAm iva khedayA'(...pushed...down) like spokes in the wheel navel with an instrument for pressing together') are pronounced in the manner that a woman from SauRAStra pronounces takram 'buttermilk': takraM, with a fully nasalized final vosel (PS 26: yathA saurASTrikA nArI takrAm ity abhibhASate evam rangAh prayoktavyA khe arAM iva khedayA). Patanjali is well aware of the r/l alternation in particular lexical terms...Old Indo-Aryan was of course dialectically differentiated (See Emeneau 1966). The earliest distribution of dialect areas would have to stem from Vedic times, and the texts, right back to the Rgveda, show evidence of dialect differences, reflected, for example, in the use of forms of the type dakSi and dhakSi 'burn' (Cardona 1991)...There is a large variety of PrAkrits, traditionally named after regions and their inhabitants: MAhArASTrI, zaurasenI and so on. Thus, Bharata mentions (NZ 17.48: mAgadhy avantijA prAcyA zauraseny ardhamAgadhI bAhlikA dAkSiNatyA ca sapta bhASAh prakIrtitA) seven languages as being well known: MAgadhI, the language of Avanti, the language of the east, ZaurasenI, ArdhamAgadhI, BAhlIkA, and the language of the south. Theoreticians of poetics and grammarians of PrAkrits also enumerate and characterize different PrAkrits, among wich MAhArAStrI is given the highest status...The closest thing we have comparable to a dialect map of Middle Indo-Aryan is represented by Azoka's inscriptions of the third century BCE. As has been recognizedd (See Bloch 1950: 43-5, Azokan/PAli section 1.2), the major rock edicts show that east, nortwest and west constitute three major dialect areas...Arya has various meanings centering about the notion of noble, venerable, honorable, but this term was explicitly used with reference to a particular group of people, characterized by the way they spoke...Patanjali uses the phrases AryA bhASante 'Aryas say' and AryAh prayunjate 'Aryas use'. In the comparable passage of his Nirukta, YAska (Nir. 2.2 [161.11-13]) says zavatir gatikarmA kambojeSv eva bhASyate...vikAram asyAryeSu bhASante zava it 'zav meaning 'go' is used only in Kamboja...in the Arya community one uses a derivate (vikAram 'modification) zava 'corpse''. Here, YAska uses the locative plural AryeSu parallel to kambojeSu, both terms referring to communities in which particular usages prevail...The Indian subcontinent has long been home to speakers of languages belonging to different language failies, principally Indo-European (Indo-Aryan), Dravidian, and Austro-Asiatic (Munda). It is to be expected that speakers of these languages who were in contact with each other should have been subject to possible influence of other languages on their own. Scholars have long been aware of and remarked on the changes which the language reflected in the earliest Vedic underwent over time, gradually becoming more and more 'Indianized', so that one can speak of an Indian linguistic area (Emeneau 1956, 1971, 1974, 1980, Kuiper 1967). Scholars have also differed concerning the degree of influence exerted by Munda or Dravidian languages on Indo-Aryan at different stages and the manner in which such influence was made felt. It is proper to emphasize from the outset that Old Indo-Aryan should be viewed as encompassing a variety of regional and social dialects spoken natively, developing historically in the way any living language does, and whose speakers interacted in a society where diglossia and polyglossia were the norm. Sanskrit speakers show an awareness of these facts. Thus, it is not only historically true that early Vedic root aorists of the type akar, agan were gradually replaced by forms of the types akArSU, agamat but also that YAska and Patanjali were aware of such changes and brought the fact out in their paraphrases; see Mehendale 1968: 15-33. PANini accounted for major features of Vedic which differed from his current language. In addition, such early native speakers of Sanskrit give us evidence of attitudes towards different varieties of speech which should be taken into consideration...Patanjali recounts the dialogue: A certain grammarian (kazcid vaiyAkaraNah) says to a chariot driver, ko 'sya rathasya pravetA 'Who is the driver of this car?' The driver answers, AyuSmann aham prAjitA 'Sir, I am the driver', upon which the grammarian accuses him of using an incorrect speech form (apazabda). The driver retorts that the grammarian knows what should obtain by rule (prAptijnah) but not what is desired (iSTijnah): this term is desirable (iSyata etad rUpam), Patanjali doubtless reflects a historical change in the language between PANini's time and area and his. At the same time, he is clearly willing to countenance that usage could include terms which a strict grammarian might consider improper. And he puts this in terms of a contrast between a grammarian and a charioteer. Another famous MaHAbhASya passage concerns sages (RSi-) who were characterized by the way they pronounced the phrases yad vA nah and tad vA nah: yar vA nah, tar vA nah. Although these sages spoke with such vernacular features, they did not do so during ritual acts...On the contrary, both accepted forms and those considered incorrect served equally to convey meanings, and what distinguished corrrect speech was that one gaind merit from such usage accompanied by a knowledge of its grammatical formation. One must recognize also that the standard speech could include elements which originally were not part of the Sanskrit norm. Moreover, Zabara remarks (on JS 1.3.5.10 [II.151]) that although authoity (pramANam) is granted to a learned elite (ziSTAh whose behaviour is authoritative with respect to what cannot be known directly (yat tu ziSTAcArah pramANam iti tat pratyakSAnavagate 'rthe) and who are experts (abhiyuktAh) as concerns the meanings of terms, nevertheless Mlecchas are more expert as concernss the care and binding of birds (yat tv abhiyuktAh zabdArtheSu ziSTA iti tatrocyate: abhiyuktatarAh pakSiNAm poSaNe bandhan ca mlecchAh). Consequently, when it comes to terms like pika- 'cuckcoo', which Aryas do not use in any meaning but which Mlecchas do (ZBh. 1.3.5.10 [II.149]: atha yAN chamdAn AryA na kasmimzcid artha Acaranti mlecchAs tu kasmimzcit prayunjate yathA pika...), authority is granted to Mleccha usage...There is thus evidence to show that before the second century BCE and possibly before PANini's time Mlecchas who inhabited areas outside the bounds of AryAvartta could be absorbed into the prevalent social system and that terms from speech areas such as that of the Kambojas could be treated as Indo-Aryan...Arya brAhmaNas normally were not supposed to engage in discourse with Mlecchas, but they had to do so on occasion. In brief, the picture is that of a society in which an Arya group considered itself the carrier of a higher culture and strived to keep this culture and the language associated with it but at the same time had necessarily to interact with groups like Mlecchas, whose language and customs were considered lesser. The result of such interaction, both with other Indo-Aryans who spoke dalects with Middle Indo-Aryan features and with non-Indo-Aryans, was that Sanskrit was effected through adoption of lexical terms and grammatical features...There is no cogent reason to consider that such changes due to contact had not been carried out gradually over generations for a long time before. Modern views. Although scholars generally agree that Old Indo-Aryan was indeed affected by 'autochthonous' languages and that there is indeed a South Asia linguistic area (see, e.g., Emeneau 1956, 1980, Kuiper 1967, Masica 1976), there are disagreements concerning the possible degree to which such effects should be seen in early Vedic and whether the features at issue could reflect also developments from Indo-European sources. In addition to the extent and sources of lexical borrowings, the main points of contention concern four features commonly considered characteristic of a South Asian linguistic area: (1) a contrast between retroflex and dental consonants, (2) the use of quotative particle (Skt. iti), (3) the use of absolutives (Skt. -tvA, ya), (4) the general unmarked word subject-object-verb...As to what non-Indo-Aryan languages are concerned, obvious candidates are Dravidian and Munda languages. The number of such borrowings into early Indo-Aryan has been the topic of ongoing debate...It has also to be admitted that the archaeological evidence available does not serve to confirm Indo-Aryan migrations into the subcontinent. Moreover, there is no textual evidence in the early literary traditions unambiguously showing a trace of such migration...In an email message kindly conveyed to me by S. Kalyanaraman (11 April 1999)...BaudhAyanazrautasUtra passage...this text cannot serve to document an Indo-Aryan migration into the main part of the subcontinent... " (Dhanesh Jain, George Cardona (eds.), 2003, The Indo-Aryan languages, Routledge, pp.6-7,17-21, 26-28, 31-37)

Terracotta spokes painted on wheels and axle. ca. 2500 BCE. Bhirrana. On the specimens found at Kalibangan and Rakhigarhi, the spokes of the wheel are shown by painted lines radiating from the central hub to the periphery, and in the case of specimens from Banawali these are executed in low relief.

![]() Elamite chariot ca 2500 BCE drawn by four onagers with primitive and painful harnessing.

Elamite chariot ca 2500 BCE drawn by four onagers with primitive and painful harnessing.

![Image result for chanhudaro chariot]() Wagon drawn by bulls Metropolitan Museum Period: Early Bronze Age II-III Date: ca. 2700–2000 B.C. Geography: Anatolia Medium: Copper Dimensions: 3.31 x 2.99 x 8.86 in.

Wagon drawn by bulls Metropolitan Museum Period: Early Bronze Age II-III Date: ca. 2700–2000 B.C. Geography: Anatolia Medium: Copper Dimensions: 3.31 x 2.99 x 8.86 in. ![Related image]()

![Image result for sumerian chariot]()

"A copper statue of a chariot being pulled by four donkeys. It depicts an early form of the wheel, which Sumerians made by pressing two pieces of wood together. The statue is 2.75 inches tall, dates to about 2700 B.C.E., and was found at Tell Agrab in Iraq." http://www.abovetopsecret.com/forum/thread568221/pg1

https://hurst-ancienthistory-kis.wikispaces.com/Guide+to+Placard+Images

Bronze chariot model with a flat shield, circa 2500 BC. See a profile view and hi-res picture.Assyrian four-wheel chariot. This picture illustrates how the side panel flairs into the curves at the top of the shield. http://sumerianshakespeare.com/84201.html![]() Ancient Sumerian wheel and axle. The Sumerians are one of the progenitor peoples of civilization with inventions such as the wheel-axle. Pan-Turk activists claim that the ancient Sumerians spoke a dialect of Turkish and that they were Turks. Linguistic and archaeological studies by international scholarship fails to verify pan-Turkist claims.

Ancient Sumerian wheel and axle. The Sumerians are one of the progenitor peoples of civilization with inventions such as the wheel-axle. Pan-Turk activists claim that the ancient Sumerians spoke a dialect of Turkish and that they were Turks. Linguistic and archaeological studies by international scholarship fails to verify pan-Turkist claims. ![Photograph:A clay war chariot is a toy from ancient Greece.]() A clay war chariot is a toy from ancient Greece.A mythical chariot to carry the sun across the sky. Gold leaf on bronze, ca. 1500 BCE.

A clay war chariot is a toy from ancient Greece.A mythical chariot to carry the sun across the sky. Gold leaf on bronze, ca. 1500 BCE.![Image result for king Tut's (1323 BCE) chariot in Egyptian museum.]() KING TUT: Painted chest, from the Tomb of Tutankhamen, Thebes, Egypt, ca. 1333-1323 BCE. Wood, approx. 1' 8 long. Egyptian Museum, Cairo.

KING TUT: Painted chest, from the Tomb of Tutankhamen, Thebes, Egypt, ca. 1333-1323 BCE. Wood, approx. 1' 8 long. Egyptian Museum, Cairo. ![King Tutankhamun's Chariot and Shields:]() King Tutankhamun's Chariot and Shields

King Tutankhamun's Chariot and Shields![]() Etruscan chariot. 530 BCE Met Museum.

Etruscan chariot. 530 BCE Met Museum.

![]()

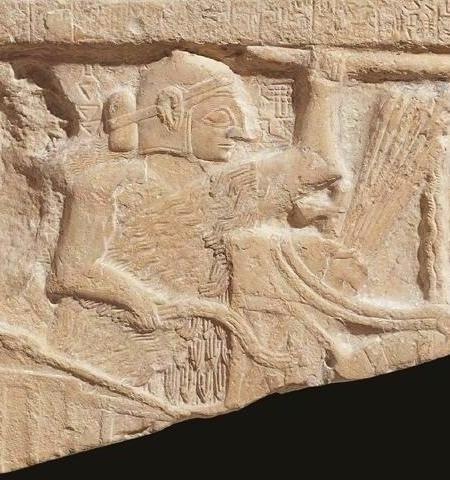

"Additional proof that some chariots had this configuration is found on a cylinder seal. The chariot in the lower register has an angled-front and a wide panel on the side of the shield."![]() "Eannatum. His chariot on the Vulture Stele is like the chariots on the Standard of Ur, with the same angled front and the crossed diagonals on the shield. The chariot is drawn in the same unusual manner, with the front on the side and the side on the front. His chariot also has the same peaked panel as the king's chariot. "

"Eannatum. His chariot on the Vulture Stele is like the chariots on the Standard of Ur, with the same angled front and the crossed diagonals on the shield. The chariot is drawn in the same unusual manner, with the front on the side and the side on the front. His chariot also has the same peaked panel as the king's chariot. "![]() "A fragment of a chariot from a Gudea stele commemorating the building of a temple for the war god Ningirsu. The front of the chariot is decorated with the figures of two gods. Above the double-curve top (like on the chariots of the Standard of Ur) is a battle ensign featuring Anzud, the lion-headed eagle, grasping two lions with his claws."

"A fragment of a chariot from a Gudea stele commemorating the building of a temple for the war god Ningirsu. The front of the chariot is decorated with the figures of two gods. Above the double-curve top (like on the chariots of the Standard of Ur) is a battle ensign featuring Anzud, the lion-headed eagle, grasping two lions with his claws."![]()

![]() See treaded tires on a ceremonial chariot from the period of Gudea.Source: http://sumerianshakespeare.com/84201.html

See treaded tires on a ceremonial chariot from the period of Gudea.Source: http://sumerianshakespeare.com/84201.html

![Related image]()

![Related image]() Sumerian chariot drawn by two onagers

Sumerian chariot drawn by two onagers

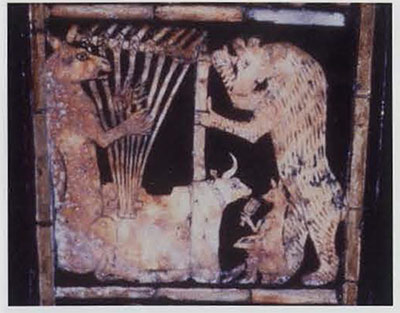

![]() "Peace," detail of Standard of Ur, showing lyrist and possibly a singer.

"Peace," detail of Standard of Ur, showing lyrist and possibly a singer.

![Standard of Ur - War.jpg]()

Standard of Ur. Royal cemetery. Ur-Pabilsag, a king who died around 2550 BCE. British Museum. shell, limestone, lapis lazuli, bitumen. c. 2600 BCE. 121201Reg number:1928,1010.3 "The present form of the artifact is a reconstruction, presenting a best guess of its original appearance. It has been interpreted as a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimetres (8.50 in) wide by 49.53 centimetres (19.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli. The box has an irregular shape with end pieces in the shape of truncated triangles, making it wider at the bottom than at the top, along the lines of a Toblerone bar." (Zettler, Richard L.; Horne, Lee; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly. Treasures from the royal tombs of Ur, pp. 45-47. UPenn Museum of Archaeology, 1998. )

Hieroglyph of onager, Ur lyre, ca. 2600 BCE: Harp, tantiburra, tambur, BAN.TUR (Sumerian) is an Indus Script hypertext. tanbura 'harp' rebus: tambra 'copper'.

--Together, کار کنده kār-kundaʿh 'director of metalwork manufactories' of ancient India and Sumer

Erwin Neumayer presents compelling evidence of animal-drawn chariots on chalcolithic rock art of many sites from ancient India (samples appended).

-- khara, 'Onager' together with khōṇḍa 'young bull-calf' are Indus Script hieroglyphic signifiers khār'blacksmith' PLUS kunda'turner, lapidary'; thus, together کار کنده kār-kundaʿh 'director of metalwork manufactories'.

-- tã̄bṛā 'carnelian', tanbura 'harp, lyre' rebus tambra 'copper', rathī रथी 'leader', ratha, 'chariot', khara, 'onagers', rebus کار kār 'professional'کار کنده kār-kundaʿh 'director', khār 'blacksmith' of Indian and Sumerian art

-- Carnelian, tã̄bṛā, tāmṛā 'stone resembling māṇikya, a ruby' from Gujarat found in Ancient Near East sites, 3rd m.BCE

-- څرخ ṯs̱arḵẖ, s.m. (2nd) A wheel (particularly a potter's, or of a water-mill or well). 2. A grindstone. 3. Circular motion, turn, revolution, the act of turning. rebus: څرخ ṯs̱arḵẖ, s.m. (2nd) (P چرخ ). 2. A wheeled-carriage, a gun-carriage, a cart. Pl. څرخونه ṯs̱arḵẖūnah.

-- Daimabad ratha, 'chariot', khara, 'onagers' of Sumerian chariot, ca. 2600 BCE

-- रथ्य n. carriage equipments (trappings , a wheel &c ) RV. La1t2y. rathin रथिन् A warrior who fights from a chariot; आत्मानं रथिनं विद्धि शरीरं रथमेव तु । बुद्धिं तु सारथिं विद्धि मनः प्रग्रहमेव च ॥ Kaṭha Up.1.3.3; R.7.37 rathī रथी Ved. 1 Riding in a chariot. -2 Furnished with a carriage. -3 A coachman. -4 A guide, leader.

-- khara खर -रः 1 An ass, Ms.2.21; 4.115,12,8.37; Y.2.16. -2 A mule.-यानम् a donkey-cart; Ms.11.21. -शब्दः 1 the braying of an ass. -शाला a stable for asses. khara1 m. ʻ donkey ʼ KātyŚr., ˚rī -- f. Pāṇ.NiDoc. Pk. khara -- m., Gy. pal. ḳăr m., kắri f., arm. xari, eur. gr. kher, kfer, rum. xerú, Kt. kur, Pr. korūˊ, Dm. khar m., ˚ri f., Tir. kh*l r, Paš. lauṛ. khar m., khär f., Kal. urt. khār, Phal. khār m., khári f., K. khar m., khürü f., pog. kash. ḍoḍ. khar, S. kharu m., P. G. M. khar m., OM. khari f.; -- ext. Ash. kərəṭék, Shum. xareṭá; <-> L. kharkā m., ˚kī f. -- Kho. khairánu ʻ donkey's foal ʼ (+?).*kharapāla -- ; -- *kharabhaka -- .Addenda: khara -- 1 : Bshk. Kt. kur ʻ donkey ʼ (for loss of aspiration Morgenstierne ID 334).(CDIAL 3818) Rebus: khara 'quick and nimble' (A.); WPah. bhad. kharo ʻ good ʼ, paṅ. cur. cam. kharā ʻ good, clean ʼ; Ku. kharo ʻ honest ʼ; N. kharo ʻ real, keen ʼ(CDIAL 3819) Semantic expansions: P کار kār, s.m. (2nd) Business, action, affair, work, labor, profession, operation. Pl. کارونه kārūnah. (E.) کار آرموده .چار kār āzmūdah. adj. Experienced, practised, veteran. کار و بار kār-o-bār, s.m. (2nd) Business, affair. Pl. کار و بارونه kār-o-bārūnah. کار خانه kār- ḵẖānaʿh, s.f. (3rd) A manufactory, a dock- yard, an arsenal, a workshop. Pl. يْ ey. کاردیده kār-dīdah, adj. Experienced, tried, veteran. کار روائي kār-rawā-ī, s.f. (3rd) Carrying on a business, management, performance. Pl. ئِي aʿī. کار زار kār-zār, s.m. (2nd) Battle, conflict. Pl. کار زارونه kār-zārūnah. کار ساز kār-sāz, adj. Adroit, clever; (Fem.) کار سازه kār-sāzaʿh. کار ساري kār-sāzī, s.f. (3rd) Cleverness, adroitness. Pl. ئِي aʿī. کار کند kār-kund(corrup. of P کار کن ) adj. Adroit, clever, experienced. 2. A director, a manager; (Fem.) کار کنده kār-kundaʿh. کار کول kār kawul, verb trans. To work, to labor, to trade.(Pashto) khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) खारवी khāravī m A caste or an individual of it. They are employed in ships and boats along the coast, in tiling houses, in plantation-business &c.खारसंध khārasandha m (खार & सांधा) Metallic cement, solder.खारसळई khārasaḷī f The stone upon which खार is levigated in preparing खारसंध or metallic cement.

Model of a two-wheeled Sumerian chariot, with chariot rein post and rings. The model of the chariot shows the image of a god on its interior.panel.It is from a later period (Neo-sumerian,ca 2000 BCE)

Assyrian four-wheel chariot. This picture illustrates how the side panel flairs into the curves at the top of the shield. http://sumerianshakespeare.com/84201.html

Etruscan chariot. 530 BCE Met Museum.

Etruscan chariot. 530 BCE Met Museum.

While फड phaḍa is a metals manufactory of the bronze age, it is reasonable to identify metalwork in the context of pictorial narratives displaying harps or lyres and also lapidaries involved in drilling and working with stone beads like carnelian beads. One such example of फड phaḍa is provided by the narratives on lyre of Ur discussed in the context of rebus reading of a manager of metal workers called کار کند kār-kund adj. Adroit, clever, experienced. 2. A director, a manager (of kundār, 'turners' or copper/metalworkers' and lapidary guild working with tāmra 'copper' and tã̄bṛā, tāmṛā 'stone resembling māṇikya, a ruby (which could be carnelian)'.

![Image result for bharatkalyan97 bull-headed lyre]() DETAIL FROM THE PANEL ON THE BULL-HEADED LYRE showing an 8-stringed bovine lyre being played. At the top of the lyre, braided material is wrapped around the crossbar under the tuning sticks. The small fox-like animal facing the front of the lyre holds a sistrum, or rattle. UPM 817694. Detail of neg. 735-110. ca. 2600 BCE.

DETAIL FROM THE PANEL ON THE BULL-HEADED LYRE showing an 8-stringed bovine lyre being played. At the top of the lyre, braided material is wrapped around the crossbar under the tuning sticks. The small fox-like animal facing the front of the lyre holds a sistrum, or rattle. UPM 817694. Detail of neg. 735-110. ca. 2600 BCE.

khara 'onager' rebus khār 'blacksmith' plays the large bull-headed lyre of Ur, c. 2600 BCE. Indus Script hypertext deciphered https://tinyurl.com/y6zvg9st

khara 'onager', kora 'harp' rebus: khār’ blacksmith’ kola 'tiger, jackal' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'

‘fine gold’ (Kannada). Ta. kuntaṉam interspace for setting gems in a jewel; fine gold (< Te.). Ka. kundaṇa setting a precious stone in fine gold; fine gold; kundana fine gold. Tu. kundaṇa pure gold. Te. kundanamu fine gold used in very thin foils in setting precious stones; setting precious stones with fine gold. (DEDR 1725) कुन्द [p= 291,2] one of कुबेर's nine treasures (N. of a गुह्यक Gal. ) L. کار کند kār-kund (corrup. of P کار کن) adj. Adroit, clever, experienced. 2. A director, a manager; (Fem.) کار کنده kār-kundaʿh. (Pashto) P کار kār, s.m. (2nd) Business, action, affair, work, labor, profession, operation. Pl. کارونه kārūnah. (E.)

.

The lyre narrative shows khara 'onager' as a harp-player and as a singer or choirmaster.

नाचण्याचा फड, गाण्याचा फड are natch house and a singing shop or merriment shop. The word फड phaḍa expresses freely Gymnasium or arena, circus, club-room, debating-room, house or room or stand for idlers, newsmongers, gossips, scamps &c. फड phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; as a court of justice, an exchange, a mart, a counting-house, a custom-house, an auction-room: also, in an ill-sense, as खेळण्या- चा फड A gambling-house, नाचण्याचा फड A nachhouse, गाण्याचा or ख्यालीखुशालीचा फड A singingshop or merriment shop. The word expresses freely Gymnasium or arena, circus, club-room, debating-room, house or room or stand for idlers, newsmongers, gossips, scamps &c. 2 The spot to which field-produce is brought, that the crop may be ascertained and the tax fixed; the depot at which the Government-revenue in kind is delivered; a place in general where goods in quantity are exposed for inspection or sale. 3 Any office or place of extensive business or work,--as a factory, manufactory, arsenal, dock-yard, printing-office &c.

I do not know if Sign 311 also signified tanbura 'harp' rebus: tambra 'copper'; tã̄bṛā, tāmṛā 'stone resembling māṇikya, a ruby'

Sign 311 Indus Script Sign List (Mahadevan) tantrīˊ f. ʻ string of a lute ʼ ŚāṅkhŚr. [tántra -- ]

तन्ति f. ( Pa1n2. 6-4 , 39 Ka1s3. on iii , 3 , 174 and vii , 2 , 9) a cord , line , string (esp. a long line to which a series of calves are fastened by smaller cords) RV. vi , 24 , 4 BhP. Sch. on S3Br. xiii and Ka1tyS3r. xx (ifc.) Rebus: a weaver.

Pa. tanti -- f. ʻ lute ʼ, Pk. taṁtī -- f.; OAw. tāṁti ʻ string of a musical instrument ʼ, H. tant f.; Si. täta ʻ string of a lute ʼ.(CDIAL 5667)

Ta. taṇṭu lute. Ma. taṇṭi a musical instrument. (DEDR 3057)

Hieroglyph: kora 'harp' rebus: koraga 'musician' (Tulu) khār 'blacksmith

After Figures 9 and 10 in: Lorenz Rahmstorf, 2015, The Aegean before and after c. 2200 BC between Europe and Asia: trade as a prime mover of cultural change

https://www.academia.edu/18193778/The_Aegean_before_and_after_c._2200_BC_between_Europe_and_Asia_trade_as_a_prime_mover_of_cultural_change?fbclid=IwAR179x12bS2DUHVp3MI2zomSnI4lvHb7yWAlbmMiMTlLMz2cDgtah0pMCl0

An elongated carnelian bead from Bogazköy-Hattusa, province of Çorum (Turkey) (cf. Fig. 1o), typologically datable to 26oo–19oo BCE, clearly shows a drilling pattern that implies a manufacture in the Indus Valley or by Indus craftsmen living in Mesopotamia (G. Ludvik/M. Pieniążek/J. M. Kenoyer, Stonebead-making technology and beads fromHattuša: A preliminary report. In: A. Schach-ner, Die Ausgrabungen in Bog˘azköy-H˘attuša2o13. Arch. Anz. 2o4,1, 147–153. Fig. 83).

Necklace or belt, Mohenjo-daro

Carnelian and copper/bronze necklace or belt. With 42 long bicone carnelian beads, 72 spherical bronze beads, 6 bronze spacer beads, 2 half moon shaped bronze terminals, 2 hollow cylindrical bronze terminals. Hoard No. 2, DK Area, Room 1, House 1, Trench E.

Material: carnelian, bronze

Dimensions: carnelian beads range from 8.22 cm to 12.4 cm length, 0.9 cm max dia.; bronze beads c. .86 cm length, .85 cm dia.; bronze spacer beads 0.2 cm length, 0.63 cm width, 6.2 cm height; bronze moon shaped terminal 3.9 cm length, 0.8 cm thickness, 6.1 cm height; bronze hollow terminal, 2.39 cm length, 1.0 cm max dia.

Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro Museum, MM1435

Marshall 1931: 520, pl. CLI, B 10 https://www.harappa.com/slide/necklace-or-belt-mohenjo-daro

Dimensions: carnelian beads range from 8.22 cm to 12.4 cm length, 0.9 cm max dia.; bronze beads c. .86 cm length, .85 cm dia.; bronze spacer beads 0.2 cm length, 0.63 cm width, 6.2 cm height; bronze moon shaped terminal 3.9 cm length, 0.8 cm thickness, 6.1 cm height; bronze hollow terminal, 2.39 cm length, 1.0 cm max dia.

Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro Museum, MM1435

Marshall 1931: 520, pl. CLI, B 10 https://www.harappa.com/slide/necklace-or-belt-mohenjo-daro

Carnelian beads with etched white lines

This carnelian bead has been artificially colored with white lines and circles using a special bleaching technique developed by the ancient Harappans.

-- kundār 'Meluhha lapidaries' are creatprs pf kunda, one of the nine treasures of Kubera

Figure 1 map prepared by VN Prabhakar, showing the location of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization sites in Gujarat is instructive. It provides a framework for positing the following hypotheses in the context of archaeologically attested trade by seafaring merchants from Meluhha:

1. The lapidaries of the civilization were kundakara m. ʻ turner ʼ W. [Cf. *

Puruṣa sūktam & Indus Script Cipher. Veneration of sādhya साध्य celestial beings, treasures, children of सोम-सद्s गण-देवता, यत्र पूर्वे साध्याः सन्ति देवाः; सायणभाष्यम्, टिप्पणी -- विकिस्रोत https://tinyurl.com/yxh4ewx6

2. The carnelian beads decorated by kundār, 'Meluhha lapidaries' are called pōttī ʻ glass bead ʼ.Pk. pottī -- f. ʻ glass ʼ; S. pūti f. ʻ glass bead ʼ, P. pot f.; N. pote ʻ long straight bar of jewelry ʼ; B. pot ʻ glass bead ʼ, puti, pũti ʻ small bead ʼ; Or. puti ʻ necklace of small glass beads ʼ; H. pot m. ʻ glass bead ʼ, G. M. pot f.; -- Bi. pot ʻ jeweller's polishing stone ʼ(CDIAL 8403) "According to Pliny the Elder, sard derived its name from the city of Sardis in Lydia from which it came, and according to others, may ultimately be related to the Persian word سرد sered, meaning yellowish red...The red variety of chalcedony has been known to be used as beads since the Early Neolithic in Bulgaria. The first faceted (with constant 16+16=32 facets on each side of the bead) carnelian beads are described from the Varna Chalolithic necropolis (middle of the 5th millennium BCE). The bow drill was used to drill holes into carnelian in Mehrgarh between 4th-5th millennium BCE. Carnelian was recovered from Bronze Age Minoan layers at Knossos on Crete in a form that demonstrated its use in decorative arts;[5] this use dates to approximately 1800 BC." (Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.)https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carnelian Twist design on the carnelian beads signify: meḍhi'plait, twist' rebus: medhā 'yajna, dhanam'.

3.

Necklace with gold beads and carnelian beads, Cypriot artwork with Mycenaean inspiration, ca. 1400–1200 BC. From Enkomi. British Museum

3. That Dholavira and Lothal may have been connected by a waterway through the Nal Sarovar, thus making most sites on the coastline of the islands of Gujarat to be ports of landing for seafaring merchants and establishing a maritime trade route through Rann of Kutch into the Persian Gulf; and

2. That the civilization sites of Rann of Kutch are explained because they were islands in the Arabian Sea and acted as port town linking seafaring merchants through the Persian Gulf.

After Figure 1. Map showing the location of Harappan sites in Gujarat (map by the author, V.N. Prabhakar, based on Google Earth Gazetteerprepared by Randall Law) Source: Prabhakar, VN, 2018, Decorated carnelian beads from the Indus Civilization site of Dholavira (Great Rann of Kachchha, Gujarat), in: Dennys Frenez et al., (eds.), Walking with the Unicorn -- Social Organization and Material Culture in Ancient South Asia, Jonathan Mark Kenoyer Felication Volume, Oxford, Archaeopress Publishing Ltd., pp. 475-485

https://tinyurl.com/y4fn6shc

After Fig. 4 in Prabhakar VN opcit., Map showing the find spots of 'etched'/bleached/decorated carnelian beads (3rd millennium BCE)

![]() Cross-section view of a strand (say, through a bead), ‘dotted circle’: धातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

Cross-section view of a strand (say, through a bead), ‘dotted circle’: धातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

![Related image]()

https://tinyurl.com/y4fn6shc

After Fig. 4 in Prabhakar VN opcit., Map showing the find spots of 'etched'/bleached/decorated carnelian beads (3rd millennium BCE)

After Figures 7 and 8. Prabhakar, VN opcit. Different patterns of decorated carnelian beads from Dholavira. Figure 8. Dholavira: a) Single-eyed decoratedcarnelian bead; b) Double-eyed decoratedcarnelian bead; c) Multiple double-eyeddecorated carnelian bead; d) Triple-eyeddecorated carnelian bead (photographsby Randall Law and the author, courtesy Archaeological Survey of India.

This monograph deciphers the Indus Script inscriptions discovered in Oman Peninsula as wealth-accounting,metalwork catalogues indicating maritime trade of metal artifacts by Meluhha merchants and artisans.

Thanks to Dennys Frenez for making available Indus Script Inscriptions and providing archaeological evidence for trade between Meluhha (Sarasvati Civilization) and Oman.

Oman 1 artifact: dotted circles on softstone bowl deciphered: dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)

Cross-section view of a strand (say, through a bead), ‘dotted circle’: धातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

Cross-section view of a strand (say, through a bead), ‘dotted circle’: धातु ‘strand, element’ rebus: ‘primary element of the earth, mineral, metal’ dhātu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ(whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)Oman1

(After Fig.35.1 in Dennys Frenez, 2018; Umm-an. Nar type softstone bowl found at Mohenjo-daro, Pakistan (after Tosi 1991)

Oman2

(After Fig. 35.2 Dennys Frenez, 2018; Indu black slipped jars: (a) entire vessel from Harappa (courtesy Indus Civilization Exhibition, Tokyo/Nagoya); (b) fragment with Indus signs scratched from Building H, Room 18 (Priod II) Ras Al-Jinz RJ-2 (photograph by D. Frenez, courtesy Oman National Museum))

After Fig. 35.4 Dennys Frenez, 2018

(After Fig.35.7 Dennys Frenez 2018. Indus style copper axes from (a Tell Abraq; (b) Umm an-Nar, (c) Ras Al Jinz, RJ2, (d) Jebel Buhais BSH67, and (3) Al Moyassar 4 (Potts 1999: Fig. 36; Frifelt 1995: fig.276; Cleuziou and Tosi 2000;fig. 12.7; Jasim 2003: fig.6; Weisgerher 1980: fig. 5.11), and (f) Indus tanged spearhead from Khor Bani Bu Ali SWY-3 (Mery and Marquis 1998: fig.7).

Oman5

(AfterFig. 35.8. Dennyss Frenez 2018. Indus drills in ernestite from Dholavira, Gujarat (photography by RW Law, courtesy Archaeological Survey of India).

Oman6

(After Fig. 35.9 Dennys Frenez 2018. Indus long and very long biconical beads in carnelian from (a) Salut ST1 (photograph by D.Frenez, courtesy Italian Mission to Oman), and (b) Bat Tomb 155 (photography by P. Koch, courtesy Ministry of Heritage and Culture of Oman).

Oman7

After Fig. 35.10 Dennys Frenez 2018.Indus bleached crnelian beads from (a) Bat Burial Pit 0025 (after Thornton et al. 2016: fig. 1.3, courtesy German Archaeological Mission to Bal), (b) Bat Tomb 401 (courtey German Archaeological Mission to Bat), (c) Bat Tower 1156 (photograph by A. Mortimer, courtesy Bal Archaeological Project), and (d) BidBid (photograph by D. Frenez and JM Kenoyer)..

Further reading

- Allchin, B. 1979. "The agate and carnelian industry of Western India and Pakistan". – In: South Asian Archaeology 1975. E. J. Brill, Leiden, 91–105.

- Beck, H. C. 1933. "Etched carnelian beads". – The Antiquaries Journal, 13, 4, 384–398.

- Bellina, B. 2003. "Beads, social change and interaction between India and South-east Asia". – Antiquity, 77, 296, 285–297.

- Brunet, O. 2009. "Bronze and Iron Age carnelian bead production in the UAE and Armenia: new perspectives". – Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, 39, 57–68.

- Carter, A. K., L. Dussubieux. 2016. "Geologic provenience analysis of agate and carnelian beads using laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry (LA-ICP-MS): A case study from Iron Age Cambodia and Thailand". – J. Archeol. Sci.: Reports, 6, 321–331.

- Cornaline de l'Inde. Des pratiques techniques de Cambay aux techno-systèmes de l'Indus (Ed. J.-C. Roux). 2000. Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l'homme, Paris, 558 pp.

- Glover, I. 2001. "Cornaline de l'Inde. Des pratiques techniques de Cambay aux techno-systèmes de l'Indus (sous la direction de V. Roux). – Bulletin de l'Ecole française d'Extrême-Orient, 88, 376–381.

- Inizan, M.-L. 1999. "La cornaline de l’Indus à la Mésopotamie, production et circulation: la voie du Golfe au IIIe millénaire". – In: Cornaline et pierres précieuses. De Sumer à l'Islam (Ed. by F. Tallon), Musée du Louvre, Paris, 127–140.

- Insoll, T., D. A. Polya, K. Bhan, D. Irving, K. Jarvis. 2004. "Towards an understanding of the carnelian bead trade from Western India to sub-Saharan Africa: the application of UV-LA-ICP-MS to carnelian from Gujarat, India, and West Africa". – J. Archaeol. Sci., 31, 8, 1161–1173.

- Kostov, R. I.; Pelevina, O. (2008). "Complex faceted and other carnelian beads from the Varna Chalcolithic necropolis: archaeogemmological analysis". Proceedings of the International Conference "Geology and Archaeomineralogy". Sofia, 29–30 October 2008. Sofia: Publishing House "St. Ivan Rilski": 67–72.

- Mackay, E. 1933. "Decorated carnelian beads". – Man, 33, Sept., 143–146.

- Theunissen, R. 2007. "The agate and carnelian ornaments". – In: The Excavations of Noen U-Loke and Non Muang Kao (Eds. C. Higham, A. Kijngam, S. Talbot). The Thai Fine Arts Department, Bangkok, 359–377.Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carnelian

Chariots in the Chalcolithic Rock Art of India

In this article Erwin Neumayer studies the rock paintings from sites in Madhya Pradesh, Karnataka, Uttar Pradesh and Rajasthan to investigate the role and types of the chariot. Based on writing and other artefacts (such as the copper hoard) he offers a date between 1800-1200 BC for these paintings, however whether these dates relate to the paintings remains unconfirmed. Within the realm of symbolism, he posits that these chariots could be read as vehicles of the Gods and Heroes, and the animals as fantastical creatures and chimeras.

Of course the wheel persists as one of the most enduring of ancient motifs, represented later in the Buddhist chakra and Gandhi's spinning wheel.

Within the Harappan civilization, there are numerous depictions of wheels on seals, as well as clay figurines in the shape of bullock carts and wheeled animals. Mark Kenoyer has discussed these in detail in Wheeled Vehicles of the Indus Valley Civilization of Pakistan and India published previously on Harappa.com.

Erwin Neumayer writes, "It so happens we are dealing with a very elusive object: We have cities as big as the late Bronze Age allowed, alas without horses, but carts and wheels in miniature, wheeled toys and marks of wheels on city roads, with cattle as draught animals alone. All we got from then is a number of toy carts made of clay and one a miniature bronze chariot from Daimabad, the find from an outlaying area of the Harappan Culture Region deep down in the Deccan. It is only this chariot which gives away enough on technological details to understand that the war chariot was known, but the draught animals are still long legged oxen. But there we also see a yoke fit for the neck of horses rather then cattle, and loops at the yoke serving as reign-sorters fit to guide crossed reign trains- a necessity for a fast moving chariot." [Foreword, pp. 1-2.]

Our book review of Neumayer's Preshitoric Rock Art of India(Oxford, 2008).

Photo credit: http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/india/central_india/characteristics_in...

https://www.harappa.com/content/chariots-chalcolithic-rock-art-india

Of course the wheel persists as one of the most enduring of ancient motifs, represented later in the Buddhist chakra and Gandhi's spinning wheel.

Within the Harappan civilization, there are numerous depictions of wheels on seals, as well as clay figurines in the shape of bullock carts and wheeled animals. Mark Kenoyer has discussed these in detail in Wheeled Vehicles of the Indus Valley Civilization of Pakistan and India published previously on Harappa.com.

Erwin Neumayer writes, "It so happens we are dealing with a very elusive object: We have cities as big as the late Bronze Age allowed, alas without horses, but carts and wheels in miniature, wheeled toys and marks of wheels on city roads, with cattle as draught animals alone. All we got from then is a number of toy carts made of clay and one a miniature bronze chariot from Daimabad, the find from an outlaying area of the Harappan Culture Region deep down in the Deccan. It is only this chariot which gives away enough on technological details to understand that the war chariot was known, but the draught animals are still long legged oxen. But there we also see a yoke fit for the neck of horses rather then cattle, and loops at the yoke serving as reign-sorters fit to guide crossed reign trains- a necessity for a fast moving chariot." [Foreword, pp. 1-2.]

Our book review of Neumayer's Preshitoric Rock Art of India(Oxford, 2008).

Photo credit: http://www.bradshawfoundation.com/india/central_india/characteristics_in...

https://www.harappa.com/content/chariots-chalcolithic-rock-art-india

Prehistoric Rock Paintings and Ancient Indus Motifs

July 14th, 2016

One of the least explored avenues in ancient Indus research, one which would so clearly reinforce the available evidence for the long, deep local roots of Indus civilization stretching back deep into the Stone Age (25,000-30,000 years back), when "primitive" tribes painted their stories on rock faces all over India. "India is one of the regions in the world where Stone Age paintings have survived in great numbers and in astonishingly well-reserved state," writes Erwin Neumayer, author of Prehistoric Rock Art of India (p. ix) and other books on this enormous and little understood subject.

Neumayer is one of the most unique scholars of ancient Indian history, one who has spent thousands of hours carefully reading and transcribing drawings made by our ancestors in rock cliffs, deep caves and exposed stone surfaces from the Karakorams to Bhopal, from the southern Deccan to Nepal. Alone he has saved and preserved thousands of images as a personal crusade, much like the leading Indian discoverers of these drawings like V.S. Wakankar, to whom Neumayer's book is dedicated, and other greats in the field whose life works contribute to the record in Prehistoric Rock Art of India.

It's hard to look at these images and not think that there are deep similarities with ancient Indus iconography. The intricate design patterns of Mesolithic art (10,000-5,000 BCE) mesmerize; there is the figure with the bow and arrow; the side profile nature of animal depictions, especially bovines carried through to seals; a hunter spearing a buffalo; bangled women; the ubiquitous use of red oxide paint. It does not seem irrational to suppose a continuity between Neolithic, Mesolithic and later Indus iconography, a continuity from which nearly all traces have been lost to archaeology and science. Except for these rock paintings, that is.

"Depictions of bulls with decorated horns constitute a prominent feature of Chalcolithic rock art [from around 2500 BCE, the Indus period]. The humped bull obviously held a pivotal position in religious symbolism. It is likely that the bull symbolized a deity, which is at times expressed in a symbolic dualism between a hero and a bull. This symbolism is also seen on Indus valley seals and in paintings on Chalcolithic pottery from the early Neolithic cultures of western South Asia" writes Neumayer (p. 194, C002, Figures 1. and 2. below).

Then there is, in Neumayer's words "the ithyphallic Hero surrounded by - or confronting - animals, a recurring mythologem in Chalcolithic art." (3.)

There is even a "Deity of the 'Pashupatinath-type' with a wide out-loading horn-crown from which emanate plant-sprouts." (4.)

Then there are multi-level narrative pieces like this one: "The composition has several thematic and directional orientations. The centre of the composition seems to be made up by the man driving two yoked cattle. The man sports frizzy hair and decorations on his middle. The cattle move towards one other man who also drives two yoked cattle. Around these groups are several cattle with prominent humps. Below this are deer and other smaller wild animals. Two hunters with a bow and arrow held ready are moving towards this group. Below the ploughman is a large wild buffalo and below this is a file of monkeys preceded by a dog (?), a peacock, a boar and several antelopes (?), all moving against the direction of the ploughman. (p. 202, C047)"

This is the first of a series of posts in the coming months which will look in more detail at some of the possible similarities between Indus iconography and prehistoric rock art (ca. 25000 BCE-2500 BCE)

Illustrations are all from Erwin Neumayer's Prehistoric Rock Art of India (2013).

1. Humped bull with lyre-shaped horns led by an axe-wielding man. Nearby a man is struck down by another man with an axe. Chibbar Nulla, Chalocolithic, Length of animal 20 cm. (C002)

2. Depictions of bulls with decorated horns constitute a prominent feature of Chalcolithic rock art. The humped bull obviously held a pivotal position in religious symbolism. It is likely that the bull symbolized a deity, which is at times expressed in a symbolic dualism between a hero and a bull. This symbolism is also seen on Indus valley seals and in paintings on Chalcolithic pottery from the early Neolithic cultures of western South Asia. Naldeh, Chalcolithic, Length 40 cm, Bull [all 4 paintings]. C015-C018

3. The ithyphallic Hero surrounded by - or confronting - animals. Satkunda, Chalcolithic, Height of the person 25 cm. C035.

4. Deity of the 'Pashupatinath-type' with a wide out-loading horn-crown from which emanate plant-sprouts. In his right hand he holds a staff with upwards directed prongs and a serrated scythe (?). From the deity's phallus emanates a line that encircles animals and smaller deities. This picture was found under a rocky ledge which forms a waterfall during the rains. A heavy encrustation covers the pictures. Bundi, Mahadeo Pani, Chalcolithic, Height 50 cm. C022.

5. A pair of yoked humped cattle. Raisen-Ramchaja, Raisen, Chalcolithic, Red, length of bovid ca. 20 cm. C047.

https://www.harappa.com/blog/prehistoric-rock-paintings-and-ancient-indus-motifs-0

Pola festival. Animals on wheels

![Image result for daimabad rhinoceros]() Daimabad, bronze animals on wheels

Daimabad, bronze animals on wheels

![Related image]()

Neumayer is one of the most unique scholars of ancient Indian history, one who has spent thousands of hours carefully reading and transcribing drawings made by our ancestors in rock cliffs, deep caves and exposed stone surfaces from the Karakorams to Bhopal, from the southern Deccan to Nepal. Alone he has saved and preserved thousands of images as a personal crusade, much like the leading Indian discoverers of these drawings like V.S. Wakankar, to whom Neumayer's book is dedicated, and other greats in the field whose life works contribute to the record in Prehistoric Rock Art of India.

It's hard to look at these images and not think that there are deep similarities with ancient Indus iconography. The intricate design patterns of Mesolithic art (10,000-5,000 BCE) mesmerize; there is the figure with the bow and arrow; the side profile nature of animal depictions, especially bovines carried through to seals; a hunter spearing a buffalo; bangled women; the ubiquitous use of red oxide paint. It does not seem irrational to suppose a continuity between Neolithic, Mesolithic and later Indus iconography, a continuity from which nearly all traces have been lost to archaeology and science. Except for these rock paintings, that is.

"Depictions of bulls with decorated horns constitute a prominent feature of Chalcolithic rock art [from around 2500 BCE, the Indus period]. The humped bull obviously held a pivotal position in religious symbolism. It is likely that the bull symbolized a deity, which is at times expressed in a symbolic dualism between a hero and a bull. This symbolism is also seen on Indus valley seals and in paintings on Chalcolithic pottery from the early Neolithic cultures of western South Asia" writes Neumayer (p. 194, C002, Figures 1. and 2. below).

Then there is, in Neumayer's words "the ithyphallic Hero surrounded by - or confronting - animals, a recurring mythologem in Chalcolithic art." (3.)

There is even a "Deity of the 'Pashupatinath-type' with a wide out-loading horn-crown from which emanate plant-sprouts." (4.)

Then there are multi-level narrative pieces like this one: "The composition has several thematic and directional orientations. The centre of the composition seems to be made up by the man driving two yoked cattle. The man sports frizzy hair and decorations on his middle. The cattle move towards one other man who also drives two yoked cattle. Around these groups are several cattle with prominent humps. Below this are deer and other smaller wild animals. Two hunters with a bow and arrow held ready are moving towards this group. Below the ploughman is a large wild buffalo and below this is a file of monkeys preceded by a dog (?), a peacock, a boar and several antelopes (?), all moving against the direction of the ploughman. (p. 202, C047)"

This is the first of a series of posts in the coming months which will look in more detail at some of the possible similarities between Indus iconography and prehistoric rock art (ca. 25000 BCE-2500 BCE)

Illustrations are all from Erwin Neumayer's Prehistoric Rock Art of India (2013).

1. Humped bull with lyre-shaped horns led by an axe-wielding man. Nearby a man is struck down by another man with an axe. Chibbar Nulla, Chalocolithic, Length of animal 20 cm. (C002)

2. Depictions of bulls with decorated horns constitute a prominent feature of Chalcolithic rock art. The humped bull obviously held a pivotal position in religious symbolism. It is likely that the bull symbolized a deity, which is at times expressed in a symbolic dualism between a hero and a bull. This symbolism is also seen on Indus valley seals and in paintings on Chalcolithic pottery from the early Neolithic cultures of western South Asia. Naldeh, Chalcolithic, Length 40 cm, Bull [all 4 paintings]. C015-C018

3. The ithyphallic Hero surrounded by - or confronting - animals. Satkunda, Chalcolithic, Height of the person 25 cm. C035.

4. Deity of the 'Pashupatinath-type' with a wide out-loading horn-crown from which emanate plant-sprouts. In his right hand he holds a staff with upwards directed prongs and a serrated scythe (?). From the deity's phallus emanates a line that encircles animals and smaller deities. This picture was found under a rocky ledge which forms a waterfall during the rains. A heavy encrustation covers the pictures. Bundi, Mahadeo Pani, Chalcolithic, Height 50 cm. C022.

5. A pair of yoked humped cattle. Raisen-Ramchaja, Raisen, Chalcolithic, Red, length of bovid ca. 20 cm. C047.

https://www.harappa.com/blog/prehistoric-rock-paintings-and-ancient-indus-motifs-0

Pola festival. Animals on wheels

Daimabad, bronze animals on wheels

Daimabad, bronze animals on wheels

See treaded tires on a

See treaded tires on a

"Peace," detail of Standard of Ur, showing

"Peace," detail of Standard of Ur, showing