-- Master of animals is a bull-man, a blacksmith who attains the status of a divinity, generator of shared wealth of a nation, in Meluhha Indus Script Cipher

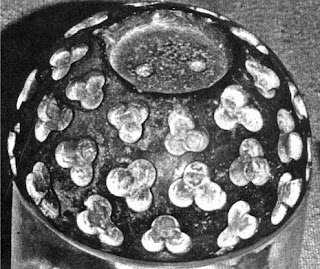

-- Jagati, jagali, cēdi is a pedestal for an idol, for e.g., to hold a śivalinga

-- anthropomorph bull-man is ḍhã̄gu 'bull', ḍã̄go ʻmale (of animals)ʼ rebus ṭhakkura ʻidol' ṭhākur 'blacksmith', 'deity'; ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith (Nepalese)(CDIAL 5524)

This is an addendum to:

jagati, 'pedestal of an idol' with dhāu 'mineral' trefoils rebus धामन् dhāman 'wealth' https://tinyurl.com/y66ru3o9

A less frequently used name is shedu (Cuneiform: 𒀭𒆘, an.kal×bad; Sumerian: dalad; Akkadian, šēdu), which refers to the male counterpart of a lamassu.(Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (2003). An Illustrated dictionary, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. The British Museum Press).https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamassu

I submit that this Akkadian word shedu is cognate with the substrate Meluhha word cēdi which is a synonm of jagati, jagali, 'a pedestal for an idol, for e.g., to hold a śivalinga'. This cēdi, 'pedestal' is archaeologically evidenced from Mohenjo-daro. The trefoil decoration on the pedestal signifies dhāu 'mineral' trefoils rebus धामन् dhāman 'wealth'. In the tradition of Ancient Near East regions, including Sumer and Elam, the

1. A finely polished pedestal. Dark red stone. Trefoils. (DK 4480, After Mackay 1938: I, 412; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218.) National Museum, Karachi. Stone base for Sivalinga.Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone.2. Two decorated bases and a lingam, Mohenjodaro. Trefoil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994, p. 218. "In an earthenware jar, No. 12414, recovered from Mound F, Trench IV, Square I"

Cēdi is a St ūpa, a sm āraka., according to the Pali lexicon.

Paia-sadda-mahannavo(a Comprehensive Prakrit-hindi Dictionary) Part-i

ByPandit, Hargovind, 1923

cēdi is the jagati, lingam base. The importance and cultural significance of the word cēdi in Ancient India is seen in the name of a janapada, it was called cēdi (See appended note)

वेदि, वेदी vēdi, vēdī , or वेदिका f S A plat or raised ground on which sacrifices or oblations are offered. 2 A border around the कुंड (the pit) or the level area of a place of sacrifice. 3 A defined space (as in the yard of a temple &c.) on which a raised mass is made, serving as an altar; a seat for the vessels used in oblations &c; a stand for idols to be placed and worshiped.

लिंग liṅga n (S) The penis. 2 Gender. (पुल्लिंग Masculine, स्त्रीलिंग Feminine, नपुंसकलिंग Neuter.) 3 The Phallus or emblematic representation of Shiva. 4 An affix to the names of worshipers of the lingam; as दादलिंग, सदलिंग. 5 A distinguishing mark; a sign, token, badge. 6 Nature or Prakriti, according to the Sánkhya philosophy; the active or motive power in creation. (Marathi)![Image result for bull man bharatkalyan97]() Bull-man. Chitragupta temple.Khajuraho.

Bull-man. Chitragupta temple.Khajuraho.

"The lamassu is a celestial being from Mesopotamian mythology. Human above the waist and a bull below the waist, it also has the horns and the ears of a bull. It appears frequently in Mesopotamian art, sometimes with wings. The lamassu and shedu were household protective spirits of the common Babylonian people. Later during the Babylonian period they became the protectors of kings as well always placed at the entrance. Statues of the bull-man were often used as gatekeepers. The Akkadians associated the god Papsukkal with lamassu and the god Isum with shedu."

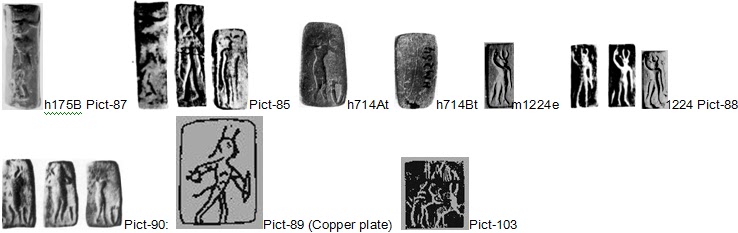

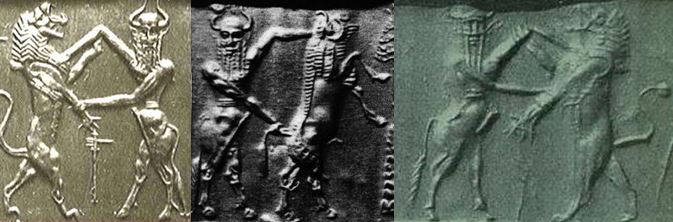

R M van Dijk-Coombes (Stellenbosch University), 2016, Cylinder seals in the collections of Iziko museums of South Africa in Cape Town and the Dept. of Ancient Studies of Stellenbosch University, in: Akroterion 61 (2016) 1-23

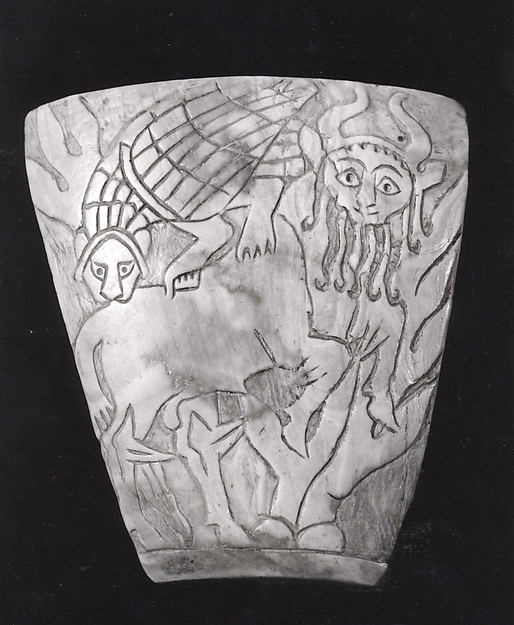

Plaque carved from a piece of shell incised with the image of a human-headed bull attacked by a lion-headed eagle. Sumerian, Early Dynastic IIIa, ca. 2600–2500 B.C.E (The Metropolitan Museum of Art).

Cylinder seal of Uruk displaying a confronted-lioness motif sometimes described as a "serpopard" - 3000 BCE - Louvre

Sphinx. A South Indian temple frescoe. Bull-man venerates Śivalinga. Offers a chess piece of horse. https://www.sanskritimagazine.com/indian-religions/hinduism/sphinx-in-the-vedas/ While chanting Yajurveda, the priest presents a Purushamrga lamp.

Sphinx. A South Indian temple frescoe. Bull-man venerates Śivalinga. Offers a chess piece of horse. https://www.sanskritimagazine.com/indian-religions/hinduism/sphinx-in-the-vedas/ While chanting Yajurveda, the priest presents a Purushamrga lamp.

Sandstone Sanchi, Central India Shunga period,

2nd Century BC - Winged Lion of India

Griffin at the stupa of Sanchi,second half of 2ndcent. BCE (Kramrisch 1954, pic.13)

https://www.insa.nic.in/writereaddata/UpLoadedFiles/IJHS/Vol51_4_2016_Art05.pdf

(Katayoun Fekripour, 2016, The Hybrid Creatures in Iranian and Indian Art, in: Indian Journal of History of Science, 51.4 (2016) , pp.585-591).

purushamriga, Kailasha temple. 8th cent.

purushamriga, Kailasha temple. 8th cent. Sphinx of India or purushamriga has now also been found in the Mallikarjuna temple at Pattadakal,

Sphinx of India or purushamriga has now also been found in the Mallikarjuna temple at Pattadakal, Spinx. Nataraja temple. Chidambaram.

Spinx. Nataraja temple. Chidambaram.

Sphinx on the southern side, facing northeast; sphnx on the northern side, facing southeast. Kailasha temple, Ellora.

Sphinx on the southern side, facing northeast; sphnx on the northern side, facing southeast. Kailasha temple, Ellora.

Lamassu winged bull amulet replica. Limestone and Quartzite composite stone Lamassu bull Dimensions:- 5.5 cm x 5.5 cm / 2-1/4 x 2-1/4 inches

The construction of the Stairs of All Nations and the Gate of All Nations was ordered by the Achaemenid king Xerxes I (486-465 BC), the successor of the founder of Persepolis, Darius I the Great. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gate_of_All_Nations

Truncated vase representing a bull man seizing snakes

Iran, southeastern region

Trans-Elamite civilization

2600-2200 BCE

Chlorite, incrustations of carnelian and limestone or heated steatite?

Jeogjt” 12 c,. doa” 6.8 cm Formerly Kevorkian collection

INV. 241-29

“In this instance, the mythological jinn, rendered twice is a bull man, a hybrid creature wel-known in the Mesopotamian iconography of the third millennium…It is represented in the posture of a master of animals who tames eared snakes."—Agnes Benoit Le profane et le divin, arts de l’Antiquite

Modern impression of an Akkadian cylinder seal inscribed with a scene of a seated deity wearing horned headdress, with attendant and a recumbent bull supporting a winged gate, Akkadian. seal c 2300 2100 BCE. Edhaim delta, Balad, Iraq. (Photo by Werner Forman/Universal Images Group/Getty Images)

Weight bearing an engraving depicting the hero Gilgamesh fighting two snakes, steatite or chlorite. Sumerian civilisation, 3rd millennium BC. (Photo by DeAgostini/Getty Images)

Akkadian cylinder-seal impression of a bull-man and hero. Each is holding a bull by the horns, and in the centre is a stylised mountain with a sacred tree on top. The hero may be Gilgamesh, and the bull-man Enkidu his best friend. (Photo by CM Dixon/Print Collector/Getty Images)

Cylinder Seal with Kneeling Nude Heroes, c. 2220-2159 B.C.E., Akkadian (Metropolitan Museum of Art) Cylinder Seal (with modern impression), showing Kneeling Nude Heroes, c. 2220-2159 B.C.E., Akkadian (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Cylinder seal impression from the Akkadian period with a combat scene between a bearded hero and a bull-man and various beasts; in the Oriental Institute, University of Chicago.

Cylinder seal with two registers. On the upper register two bull-men crouch on either side of a triple plant on a stylised mountain, possibly representing the tree of life. Eagles bite the backs of the bull-men and are driven off by two mythological figures, the bull-man "Enkidu" (left) and the naked hero "Gilgamesh" (right). On the lower register: Two bulls bow in worship before the eagle, possibly a representatin of the god Imdugud, with the outspread wings. Behind, a goat and deer with a bird between them. Culture: Mesopotamian Period: Early Dynastic III, 3000-2340 BC Material:Lazulite. Credit Line: Werner Forman Archive/ British Museum, London

CREDIT

Werner Forman Archive

Werner Forman Archive

Cylinder Seal and Modern Impression: Bull Man, Hero, and Lion Contest in the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

[quote]Cylinder Seal and Modern Impression: Bull Man, Hero, and Lion Contest

Marble

Mesopotamia

Early Dynastic III, 2600-2334 BC

Accession # 55.65.4

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art label.

and

Seals

Although engraved stones had been used as early as the seventh millennium BC to stamp impressions in clay, the invention in the fourth millennium BC of carved cylinders that could be rolled over clay allowed the development of more complex seal designs. These “cylinder seals,” first used in Mesopotamia, served as a mark of ownership or identification. Seals were either impressed in clay masses that were used to close jars, doors, and baskets, or they were rolled onto clay tablets that recorded information about commercial or legal transactions. The seals were often made of precious stones. Protective properties may have been ascribed to both the material itself and the carved designs. Seals are important to the study of ancient Near Eastern art because many examples survive from every period and can, therefore, help to define chronological phases. Often preserving imagery no longer extant in any other medium, they serve as a visual chronicle of style and iconography.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art plaque. [unquote]

Marble

Mesopotamia

Early Dynastic III, 2600-2334 BC

Accession # 55.65.4

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art label.

and

Seals

Although engraved stones had been used as early as the seventh millennium BC to stamp impressions in clay, the invention in the fourth millennium BC of carved cylinders that could be rolled over clay allowed the development of more complex seal designs. These “cylinder seals,” first used in Mesopotamia, served as a mark of ownership or identification. Seals were either impressed in clay masses that were used to close jars, doors, and baskets, or they were rolled onto clay tablets that recorded information about commercial or legal transactions. The seals were often made of precious stones. Protective properties may have been ascribed to both the material itself and the carved designs. Seals are important to the study of ancient Near Eastern art because many examples survive from every period and can, therefore, help to define chronological phases. Often preserving imagery no longer extant in any other medium, they serve as a visual chronicle of style and iconography.

Text from the Metropolitan Museum of Art plaque. [unquote]

Ugarit relief, 2nd-1st millennium, BCE. Mountain-god and two bulls with human heads and arms. Basalt bas-relief on a socle (13th BCE) from Ain Dara, north of Aleppo, Syria. National Museum, Aleppo, Syria ![Related image]()

There are some seals with clear Indus themes among Dept. of Near Eastern Antiquities collections at the Louvre in Paris, France, among them the Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum, described as "one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period [2350–2170 BCE]. . . . The decoration, which is characteristic of the Agade period, shows two buffaloes that have just slaked their thirst in the stream of water spurting from two vases held by two naked kneeling heroes." It belonged to Ibni-Sharrum, the scribe of King Sharkali-Sharri, who succeeded his father Naram-Sin. The caption cotinues: "The two naked, curly-headed heroes are arranged symmetrically, half-kneeling. They are both holding vases from which water is gushing as a symbol of fertility and abundance; it is also the attribute of the god of the river, Enki-Ea, of whom these spirits of running water are indeed the acolytes. Two arni, or water buffaloes, have just drunk from them. Below the scene, a river winds between the mountains represented conventionally by a pattern of two lines of scales. The central cartouche bearing an inscription is held between the buffaloes' horns." The buffalo was known to have come from ancient Indus lands by the Akkadians.

The first image shows the imprint of the cylinder seal, the general Mesopotamian type of seal as opposed to the usually square stamp seals found in Indus cities. The second is the diorite cylinder seal, the negative of the pressed sealing.

A second seal at the Louvre is made of steatite, the traditional Indus material, "the animal carving is similar to those found in Harappan works. The animal is a bull with no hump on its shoulders, or possibly a short-horned gaur. Its head is lowered and the body unusually elongated. As was often the case, the animal is depicted eating from a woven wicker manger."

Both seals can be found in Room 8 of the Richeliu wing, Iran and Susa during the 3rd millennium BCE.

Courtesy, The Louvre, Paris, respectively copyright RMN/Franck Raux and RMN/Thierry Ollivier. More at

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/cylinder-seal-carved-elongated-bu...

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/cylinder-seal-ibni-sharrum

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/cylinder-seal-carved-elongated-bu...

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/cylinder-seal-ibni-sharrum

greenish-black serpentine seal

Overall: 1 7/16 × 1 in. (3.6 × 2.5 cm)

The Pierpont Morgan Library, New York

Morgan Seal 159 Water buffalo subdued by nude bearded hero --Bull-man fighting lion -- Between contestant pairs, tree on knoll. Notes:

"In the seals of mature Akkad style, the theme of contest between heroes and beasts is embodied in two pairs of fighting figures flanking a central design or the panel of an inscription. A characteristic detail of the resulting rather formal composition is the lozenge effect produced by the arms of the fighters and the legs of their victims. The nude bearded hero and the bull-man are the most common protagonists in these contests, but figures attired like human huntsmen often take the place of the nude bearded hero (165) or of both fighters (166, 169). In other instances two identical bull-men (167) or nude bearded heroes (168) are represented. Water buffaloes and lions are the most frequent opponents of the heros. In these seals of mature Akkad style, lions are almost always shown in profile. The scene of 170, showing a figure pouring a libation beside the two fighting pairs, is exceptional." Porada, CANES, p. 22 https://www.themorgan.org/seals-and-tablets/83782

Ea wrestling with a water-buffalo, and bull-man possibly Enkidu fighting with a lion. Akkadian Empire. Cylinder seal.

ca. 1820–1730 B.C.

Gift of Nanette B. Kelekian, in memory of Charles Dikran and Beatrice Kelekian, 1999

Cylinder Seal (with modern impression), royal worshipper before a god on a throne with bull’s legs; human-headed bulls below, c. 1820-1730 B.C.E. (The Metropolitan Museum of Art)

Cylinder seal and modern impression- bull-man wrestling with lion; nude bearded hero wrestling with a water buffalo. Akkadian; Cylinder seal; Stone-Cylinder Seals-Inscribed. circa 2250 –2150 B.C.E. Serpentine, black. 1.42 in. (3.61 cm). Met Museum Acc. No. 41.160.281

Panels of molded bricks Susa, Iran. Louvre Museum.

The ‘Man-bull’, Panels of molded bricks, the middle of 12thcent. BCE. Apadana, Susa. H: 1.355 m; D: 0.375 m. Louvre (www.louvre.fr.)

Mors, Bronze, Ages of the Iron II-III (1000-700 BCE). Archaeology Museum, Francfort-sur-le-Main. Two heads of the griffon and one head of the man-bull. Body of the bull with a human head, horned, on the is ligatured to the body of the bull..

Master of Animals, Bronze Plate. Luristan, 11thcent. BCE. Second and fourth register carries identical narratives. Two felines are confronted and are interlaced two or three times. The thigh has a helical ornament. They seize an ibex.

Interlaced felines. Electrum goblet decorated with Master of Animals, grasping gazelles. 14th– 12th cent. BCE. Marlik. Museum of Louvre. Upper part of an animal (leopard), middle part of woman (cf. breasts), bottom part of a bird.

Master of animals, Luristan, 9th-7thcent. BCE. H: 16 cm. She is probably a female master.

Man-bull and Man-lion, Orthostates of Kargamis, 1050-850 BCE. Archaeology Museum, Ankara.

Source: http://eijh.modares.ac.ir/article-27-7470-en.pdf Ali Reza Taheri, 2017, The Man-bull and the Master of Animals in Mesopotamia and in Iran, in: Intl. J. Humanities (2013) Vol. 20(1): (13-28)

A SUMERIAN COPPER PROTOME

A SUMERIAN COPPER PROTOME EARLY DYNASTIC III, CIRCA 2550-2250 B.C.E.

A SUMERIAN COPPER PROTOME

EARLY DYNASTIC III, CIRCA 2550-2250 B.C.E.

In the form of a bull-man, cast with thick walls, the oval face with raised arching brows above lidded almond-shaped eyes, the sclerae inlaid in white stone with lapis lazuli pupils, the long triangular nose with lightly-grooved nostrils, his thin mouth smiling, with projecting triangular ears and large forward-curving tapering horns, the poll outlined by a raised ridge

4 in. (10.1 cm.) wide Provenance

EARLY DYNASTIC III, CIRCA 2550-2250 B.C.E.

In the form of a bull-man, cast with thick walls, the oval face with raised arching brows above lidded almond-shaped eyes, the sclerae inlaid in white stone with lapis lazuli pupils, the long triangular nose with lightly-grooved nostrils, his thin mouth smiling, with projecting triangular ears and large forward-curving tapering horns, the poll outlined by a raised ridge

4 in. (10.1 cm.) wide Provenance

Florent Dalcq de Gilly, Belgium (1878-1950); thence by descent.

Private Collection, Neuchâtel.

Private Collection, Neuchâtel.

2350-2150 B.C.E. Written in Akkadian A cylinder seal with a "bull-man" fighting a lion and a nude man fighting a water buffalo. (all photos from http://library.artstor.org/library/#1

Neo-Sumerian Statuette of an Androcephalous Bull, C. 2350-2000 BCE

Neo-Sumerian Statuette of an Androcephalous Bull, C. 2350-2000 BCE  Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.Hieroglyph: A. damrā ʻ young bull ʼ, dāmuri ʻ calf ʼ; B. dāmṛā ʻ castrated bullock ʼ; Or. dāmaṛī ʻ heifer ʼ, dāmaṛiā ʻ bullcalf, young castrated bullock ʼ, dāmuṛ, °ṛi ʻ young bullock ʼ.Addenda: damya -- : WPah.kṭg. dām m. ʻ young ungelt ox ʼ.damya ʻ tameable ʼ, m. ʻ young bullock to be tamed ʼ Mn. [~ *

tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) dhangar 'bull' Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'. dhangar 'blacksmith'

*dab ʻ a noise ʼ. [Onom.]P. dabaṛ -- dabaṛ ʻ with the sound of heavy and noisy steps ʼ; N. dabdab ʻ mud ʼ; H. dabdabā m. ʻ noise ʼ; M. dabdab ʻ noise of a slack drum ʼ.(CDIAL 6170)

Hieroglyph: harp: tambur

The rebus reading of hieroglyphs are: తంబుర [tambura] or

Thus the seal connotes a merchant of copper.

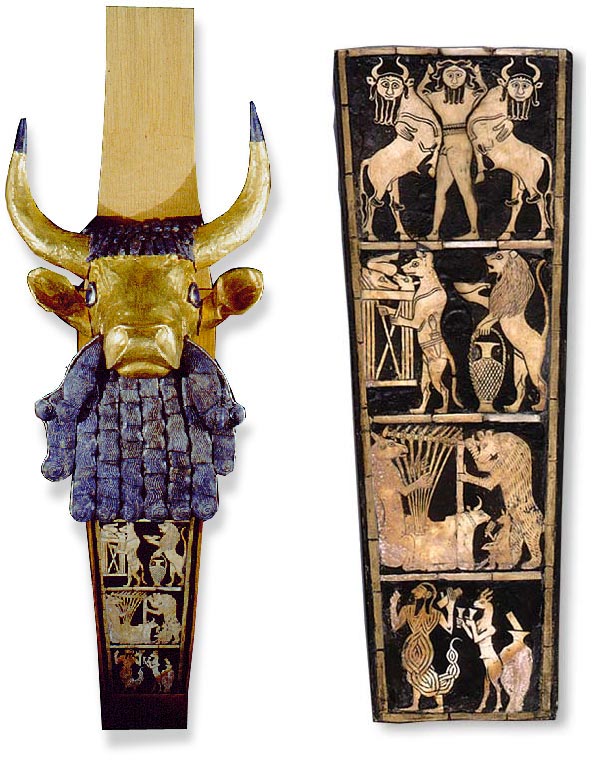

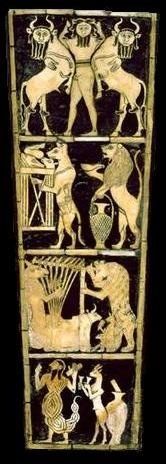

Standard of Ur, c. 2600-2400 BCE, BM ME 121201.

Bull-headed harp with inlaid sound box, from the tomb of Pu-abi (tomb 800), Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq, ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, gold, lapis lazuli, red limestone, and shell, 3′ 8 1/8″ high. British Museum, London.

Sound box of the bull-headed harp from tomb 789 (“King’s Grave”), Royal Cemetery, Ur (modern Tell Muqayyar), Iraq,ca. 2600-2400 BCE. Wood, lapis lazuli, and shell, 1′ 7″ high. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia.

"Great Lyre" from Ur: Ht 33 cm. 2550 - 2400 BCE, royal tomb at Ur (cf. pg. 106 of J. Aruz and R. Wallenfels (eds.) 2003 Art of the First Cities).

Great Lyre from the "King's Grave" (left)

and Detail of Front Panel of the Great Lyre from the "King's Grave" (right)

Ur, Iraq, ca. 2650–2550 B.C.

Gold, silver, lapis lazuli, shell, bitumen, and wood

Height: 35.6 cm (head), 33 cm (plaque)

PG 789; B17694 (U.10556)

University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology

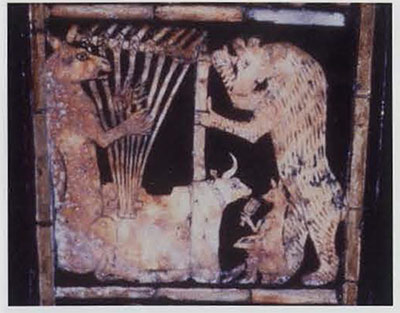

"The figures featured on the sound box of the harp are shell and red limestone and are seperated by registers. The bottom register features a scorpion-man in composite and a gazelle bearing goblets. Above them are an ass playing the harp, ajackal playing the zither and a bear steadying the harp or dancing. The second register from the top has a dog wearing a dagger and carrying a laden table with a lion bringing the beverage service. The uppermost register features the hero, also in composite, embracing two man-bulls in a heraldic composition. The meaning behind the sound box depictions is unclear but could be of funerary significance, suggesting that the creatures inhabit the land of the dead and the feast is what awaits in the afterlife. In any case, the sound box provides a very early specimen of the depiction of animals acting as people that will be found throughout history in art and literature."

https://klimtlover.wordpress.com/mesopotamia-and-persia/mesopotamia-and-persia-sumerian-art/

DETAIL FROM THE PANEL ON THE BULL-HEADED LYRE showing an 8-stringed bovine lyre being played. At the top of the lyre, braided material is wrapped around the crossbar under the tuning sticks. The small fox-like animal facing the front of the lyre holds a sistrum, or rattle. UPM 817694. Detail of neg. 735-110

Inlay panel from the soundbox of lyre.from Ur, c. 2600 B.C.E Gold, lapis lazuli, shell and bitumen

tambura 'lyre' Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper' Alternative: khara 'onager', kora 'harp' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'

barad, barat 'bull' Rebus: bharata, baran 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

kola 'tiger, jackal' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'

bica 'scorpion' rebus: bica 'hematite, ferrite ore'.

"Great Lyre" from Ur: Ht 33 cm

"Great Lyre" from Ur: Ht 33 cm. 2550 - 2400 BCE, royal tomb at Ur (cf. pg. 106 of J. Aruz and R. Wallenfels (eds.) 2003 Art of the First Cities).

Standard of Ur

Sumerian Early Dynastic III, c. 2600-2400 BCE. From the royal cemetery, Ur (Iraq).

Lapis lazuli, shell, and red limestone, with restored bitumen and red material on restored wood box

Width 49.5 cm, height 21.6 cm. Possibly soundbox of a musical instrument. British Museum ME 121201

Front and Rear views.https://www.kornbluthphoto.com/images/LouvreManBull_1.jpg

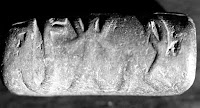

Recumbent bull with man's head,Department of Near Eastern Antiquities: Mesopotamia,Louvre

- Statuette of an androcephalous bullNeo-Sumerian period

- Chlorite with inlaysH. 12.10 cm; W. 14.90 cm; D. 8 cm

- Acquired in 1898 , 1898AO 2752

- Images of human-headed bulls are found throughout Mesopotamian history. Several statuettes dating from the late third millennium BC show a bearded creature wearing the divine horned headdress, lying down with its head turned to the side. They have been found at various Sumerian sites, the majority from Telloh.

The human-headed bull

The animal is shown lying, its head turned to the side and its tail underneath its right hoof. On its head is the divine headdress with three pairs of horns. It has a man's face with large elongated eyes, a beard covering half its cheeks and joining with the mustache before cascading down over its breast, where it ends in small curls, and long ringlets framing its face. The ears, however, are a bull's, though fleecy areas at the shoulders and hindquarters seem to suggest the animal is actually a bison. Another example in the Louvre displays particularly fine workmanship, the eyes and the whole body being enriched with decorative elements, applied or inlaid in trilobate and lozenge-shaped cavities (in the hooves). There is a small group of these recumbent bulls dating from the Neo-Sumerian period (around 2150-2000 BC), one of which is inscribed with the name of Gudea, the Second Dynasty ruler of Lagash. In the Neo-Assyrian period (9th-6th centuries BC), the human-headed bull, now with a pair of wings, becomes the guardian of the royal palace, flanking the doors through which visitors entered. This creature was a lamassu, a benevolent protective spirit generally associated with the sun-god Shamash.A base for a vessel, or for a statue of a deity?

An elongated cavity of irregular shape in the middle of the back of this statuette, also found in other examples, might have been intended to hold a removable offering bowl, as illustrated in Mesopotamian iconography. The Louvre has a statuette of a dog from Telloh, inscribed with the name of Sumu-ilum, king of Larsa in the 19th century BC, which has a mortice in the back into which fits an unpolished tenon supporting a small oval cup. It may be that the statuette was subsequently adapted to this use. Relief depictions also show a seated deity (usually the sun-god Shamash) with his foot on the back of a similar hybrid creature, which might suggest that they served as bases for statuettes of gods. Another statuette of a recumbent human-headed bull has two horizontal perforations in the narrower forequarters, suggesting that these might have served to attach a small lid.Steatite: a popular stone in the reign of Gudea

Steatite, the soft stone used for this statuette, was the material frequently chosen in the reign of Gudea to make precious objects connected with cultic rituals, such as libation vessels and offering dishes. Statuettes representing worshippers were also carved from this stone, generally depicting members of the royal family, such as the statuette of a woman with a scarf, or high-ranking dignitaries.Bibliography

André-Salvini B., "Art of the first cities : The Third millenium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus", Exposition, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 8 mai-17 août 2003, p. 440, n 313.

Barrelet M., "Taureaux et symbolique solaire", in Revue d'Assyriologie et d'Archéologie orientale, 48, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, 1954, pp. 16-27.

Caubet A., "Exposition des quatre grandes civilisations mondiales : La Mésopotamie entre le Tigre et l'Euphrate", Exposition itinérante, Setagaya, Musée d'art de Setagaya, 5 août 2000-3 décembre 2000, Fukuoka, Musée d'art asiatique de Fukuokua, 16 décembre 2000- 4 mars 2001, Tokyo : NKH, 2000, n 120.

Heuzey L., "Le taureau chaldéen androcéphale et la sculpture à incrustations", Monuments Piot, VII, 1900-1901, pp. 7-11 et planche I.

Parrot A., Tello, vingt campagnes de fouilles (1877- 1933), Paris, Albin Michel, 1948, p. 146, fig. 12b.

Huot J.-L., "The Man-Faced Bull L. 76. 17 of Larsa", in Sumer, 34, Bagdad, State Organization of Antiquities and Heritage, 1978, pp. 106- 108, fig. a.

Spycket A., La statuaire du Proche-Orient ancien, Leyde, Brill, 1981, p. 220, n 184, pl. 147.

Three-faced person with armlets, bracelets seated on a stool with bovine legs. Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050

Three-faced person with armlets, bracelets seated on a stool with bovine legs. Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050Hieroglyph: kamaḍha ‘penance’ (Pkt.) Rebus 1: kampaṭṭa ‘mint’ (Ma.) kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.);Rebus 2: kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar' (Santali); kan ‘copper’ (Ta.)

Hieroglyph: karã̄ n. pl. ʻwristlets, bangles ʼ (Gujarati); kara 'hand' (Rigveda) Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

The bunch of twigs = ku_di_, ku_t.i_ (Skt.lex.) ku_di_ (also written as ku_t.i_ in manuscripts) occurs in the Atharvaveda (AV 5.19.12) and Kaus’ika Su_tra (Bloomsfield’s ed.n, xliv. cf. Bloomsfield, American Journal of Philology, 11, 355; 12,416; Roth, Festgruss an Bohtlingk,98) denotes it as a twig. This is identified as that of Badari_, the jujube tied to the body of the dead to efface their traces. (See Vedic Index, I, p. 177).[Note the twig adoring the head-dress of a horned, standing person]

On Mohenjo-Daro seal No. 357, female with horns, hooves, and tail is shown attacking a tiger. A tree in the background.

Mohenjo-Daro seal showing a zoomorphic horned female with horns, hooves and a tail, attacking a tiger. National Museum, New Delhi, India. Source: flickr/mukul banerjee

Dholavira molded terracotta tablet showing the zoomorphic horned female with hooves and a tail, holding the hand of a man. Source: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com

Dholavira molded terracotta tablet showing the zoomorphic horned female with hooves and a tail, holding the hand of a man. Source: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.comBull-man hypertexts in Ancient Near East including Meluhha Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union) signify a blacksmith.

Ugarit relief, 2nd-1st millennium, BCE. Mountain-god and two bulls with human heads and arms. Basalt bas-relief on a socle (13th BCE) from Ain Dara, north of Aleppo, Syria. National Museum, Aleppo, Syria

British Museum number103225 Baked clay plaque showing a bull-man holding a post.

Old Babylonian 2000BC-1600BCE Length: 12.8 centimetres Width: 7 centimetres Barcelona 2002 cat.181, p.212 BM Return 1911 p. 66

On this terracotta plaque, the mace is a phonetic determinant of the bovine (bull) ligatured to the body of the person holding the mace.

Girsu (Tlloh) archaeological find. 11 ft. tall copper plated flagpost. This may relate to a period when Girsu (ca. 2900-2335 BCE) was the capital of Lagash at the time of Gudea.

Girsu (Tlloh) archaeological find. 11 ft. tall copper plated flagpost. This may relate to a period when

ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)Allograph: ढाल [ ḍhāla ] f (S through H) The grand flag of an army directing its march and encampments: also the standard or banner of a chieftain: also a flag flying on forts &c. ढालकाठी [ ḍhālakāṭhī ] f ढालखांब m A flagstaff; esp.the pole for a grand flag or standard. 2 fig. The leading and sustaining member of a household or other commonwealth. 5583 ḍhāla n. ʻ shield ʼ lex. 2. *ḍhāllā -- . 1. Tir. (Leech) "dàl"ʻ shield ʼ, Bshk. ḍāl, Ku. ḍhāl, gng. ḍhāw, N. A. B. ḍhāl, Or. ḍhāḷa, Mth. H. ḍhāl m.2. Sh. ḍal (pl. °le̯) f., K. ḍāl f., S. ḍhāla, L. ḍhāl (pl. °lã) f., P. ḍhāl f., G. M. ḍhāl f. WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ḍhāˋl f. (obl. -- a) ʻ shield ʼ (a word used in salutation), J. ḍhāl f. (CDIAL 5583).

ḍhālako = a large metal ingot (G.) ḍhālakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (Gujarati)Allograph: ढाल [ ḍhāla ] f (S through H) The grand flag of an army directing its march and encampments: also the standard or banner of a chieftain: also a flag flying on forts &c. ढालकाठी [ ḍhālakāṭhī ] f ढालखांब m A flagstaff; esp.the pole for a grand flag or standard. 2 fig. The leading and sustaining member of a household or other commonwealth. 5583 ḍhāla n. ʻ shield ʼ lex. 2. *ḍhāllā -- . 1. Tir. (Leech) "dàl"ʻ shield ʼ, Bshk. ḍāl, Ku. ḍhāl, gng. ḍhāw, N. A. B. ḍhāl, Or. ḍhāḷa, Mth. H. ḍhāl m.2. Sh. ḍal (pl. °le̯) f., K. ḍāl f., S. ḍhāla, L. ḍhāl (pl. °lã) f., P. ḍhāl f., G. M. ḍhāl f. WPah.kṭg. (kc.) ḍhāˋl f. (obl. -- a) ʻ shield ʼ (a word used in salutation), J. ḍhāl f. (CDIAL 5583).

The person signified is: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ "... head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull...Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. British Museum. WCO2652. Bull-manTerracotta plaque. Bull-man holding a post. Mesopotamia, ca. 2000-1600 BCE."

Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ "... head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull...Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. British Museum. WCO2652. Bull-manTerracotta plaque. Bull-man holding a post. Mesopotamia, ca. 2000-1600 BCE."

Terracotta. This plaque depicts a creature with the head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull. Though similar figures are depicted earlier in Iran, they are first seen in Mesopotamian art around 2500 BC, most commonly on cylinder seals, and are associated with the sun-god Shamash. The bull-man was usually shown in profile, with a single visible horn projecting forward. However, here he is depicted in a less common form; his whole body above the waist, shown in frontal view, shows that he was intended to be double-horned. He may be supporting a divine emblem and thus acting as a protective deity.

Old Babylonian, about 2000-1600 BCE From Mesopotamia Length: 12.8 cm Width: 7cm ME 103225 Room 56: Mesopotamia Briish Museum

Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. While many show informal scenes and reflect the private face of life, this example clearly has magical or religious significance.

Hieroglyph carried on a flagpost by the blacksmith (bull ligatured man: Dhangar 'bull' Rebus: blacksmith') ḍhāla 'flagstaff' Rebus: ḍhāla 'large ingot'

Note: Indus Script Corpora signifies bull as a hieroglyph: dhangar 'bull' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'

Field Symbol codes 50 to 53:

50. Personage wearing a diadem or tall head-dress Slanding between two posts or under an ornamental arch.

51. Standing pe rsonage with horns and bovine features (hoofed legs an d/or tail).

52. Standing personage with ho rns and bovine features. hold ing a bow in one hand and an arrow o r an un ce rtain

object in the other.

53. Standing pe rsonage with horns and bovine features holding a staff or mace on his shoulder.

Stone seal. h179. National Museum, India. Carved seal. Scan 27418 Tongues of flame decorate the flaming pillar, further signified by two 'star' hieroglyphs on either side of the bottom of the flaming arch.

Stone seal. h179. National Museum, India. Carved seal. Scan 27418 Tongues of flame decorate the flaming pillar, further signified by two 'star' hieroglyphs on either side of the bottom of the flaming arch.The canopy is visually and semantically reinforced by a series of decorative canopies (pegs) topped by umbrella hieroglyph along the arch.

The hypertexts are read rebus in Meluhha Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union):

1. The adorned, horned person standing within the canopy: karã̄ 'wristlets' khār 'blacksmith' kūṭa, 'horn'kūṭa 'company'

2. Headdress: kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. Vikalpa: Vikalpa: kūtī = bunch of twigs (Skt.) Rebus: kuṭhi = furnace (Santali).Thus the standing person with twig headdress is a khār blacksmith working with khār smelter and furnace.

3. Canopy: M. mã̄ḍav m. ʻ pavilion for festivals ʼ, mã̄ḍvī f. ʻ small canopy over an idol ʼ(CDIAL 9734) rebus:

maṇḍā 'warehouse, workshop' (Konkani) maṇḍī 'market' karã̄ n. pl.wristlets, banglesRebus: khār 'karmakāra -- ]Pa. kammāra -- m. ʻ worker in metal ʼ; Pk. kammāra -- , °aya -- m. ʻ blacksmith ʼ, A. kamār, B. kāmār; Or. kamāra ʻ blacksmith, caste of non -- Aryans, caste of fishermen ʼ; Mth. kamār ʻ blacksmith ʼ, Si. kam̆burā.*karmāraśālā -- .

Addenda: karmāˊra -- : Md. kan̆buru ʻ blacksmith ʼ.(CDIAL 2898)

4 Decoration on canopy: umbrella on pegs: Hieroglyph: canopy, umbrella: Ta. kuṭai umbrella, parasol, canopy. Ma. kuṭa umbrella. Ko. koṛ umbrella made of leaves (only in a proverb); keṛ umbrella. To. kwaṛ

id. Ka. koḍe id., parasol. Koḍ. koḍe umbrella. Tu. koḍè id. Te. goḍugu id., parasol. Kuwi (F.) gūṛgū, (S.) gudugu, (Su. P.) guṛgu umbrella (< Te.). / Cf. Skt. (lex.) utkūṭa- umbrella, parasol.Ta. kūṭāram(DEDR 1881) Rebus: kūṭa 'company' (Kannada)

5. The canopy is flanked by a pair of stars: Hieroglyph:मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'polar star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Santali.Mu.Ho.) dula'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' Thus, signifying a cast iron smelter.

Ka. kūṭa joining, connexion, assembly, crowd, heap, fellowship, sexual intercourse; ku·ṭï gathering, assembly. Tu. kūḍuni to join (tr.), unite, copulate, embrace, adopt; meet (intr.), assemble, gather, be mingled, be possible; kūḍisuni to add; kūḍāvuni, kūḍisāvuni to join, connect, collect, amass, mix; kūṭuni, kūṇṭuni to mix, mingle (tr.); kūḍa along with; kūḍigè joining, union, collection, assemblage, storing, mixing; kūṭaassembly, meeting, mixture. Te. kūḍu to meet (tr.), join, associate with, copulate with, add together; meet (intr.), join, agree, gather, collect, be proper; kūḍali, kūḍika joining, meeting, junction; kūḍa along with; kūḍaniwrong, improper; kūḍami impropriety; kūṭamu heap, assembly, conspiracy; kūṭuva, kūṭuvu heap, collection, army; kūṭami meeting, union, copulation; kūṭakamu addition, mixture; kūr(u)cu to join, unite, bring together, amass, collect; caus. kūrpincu; kūrpu joining, uniting. Kol. (Kin.) kūṛ pāv meeting of ways (pāv way, path). Pa. kūṛ er- to assemble. Go. (S.) kūṛ- to join; (Mu.) gūḍ- to assemble (Voc. 833); (M.) guṛnā to swarm (Voc. 1160). Konḍa kūṛ- (-it-) to join, meet, assemble, come together; kūṛp- to mix (cereals, etc.), join or put together, collect; kūṛaŋa together. Pe. kūṛā- (kūṛa ā-) to assemble. Kuwi (Su.) kūṛ- id.; (Isr.) kūṛa ā-to gather together (intr.); kūṛi ki- to collect (tr.); (S.) kūḍi kīnai to gather; kūṛcinai to collect. Kur. xōṇḍnā to bring together, collect into one place, gather, wrinkle (e.g. the nose), multiply in imagination; xōṇḍrnā to meet or come together, be brought into the company of.(DEDR 1882)

Obverse: Pictorial motif

khār 'blacksmith' emerges out of the tree or flaming pillar (skambha) identified by the 'star' hieroglyph'. The wristlets he wears and headdress signify that he is khār working with kuṭhi 'tree' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelting furnace'. He is a smith engaged in smelting.

Hieroglyph:मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'polar star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Santali.Mu.Ho.) dula'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' Thus, signifying a cast iron smelter.

Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.Hieroglyph: karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, bangles' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'

Hieroglyph: head-dress: kūdī, kūṭī bunch of twigs (Sanskrit) kuṭhi 'tree' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelting furnace' (Santali) (Phonetic determinative of skambha, 'flaming pillar', rebus:kammaTa 'mint, coiner, coinage'). Skambha, flamiung pillar is the enquiry in Atharva veda Skambha Sukta (AV X.7,8)

Scan 27419.

Hieroglyphs: backbone + four short strokes

Signs 47, 48: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) + gaṇḍa ‘four’ Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’. Thus, Sign 48 reads rebus: bharat kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’, furnace for mixed alloy called bharat(copper, zinc, tin alloy), Pk. karaṁḍa -- m.n. ʻ bone shaped like a bamboo ʼ, karaṁḍuya -- n. ʻ backbone ʼ.( (CDIAL 2670) rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy'. Vikalpa:

Hieroglyph: khāra 2 खार (= खार् (L.V. 96, K.Pr. 47, Śiv. 827) । द्वेषः m. (for 1, see khār 1 ), a thorn, prickle, spine (K.Pr. 47; Śiv. 827, 153)(Kashmiri) Pk. karaṁḍa -- m.n. ʻ bone shaped like a bamboo ʼ, karaṁḍuya -- n. ʻ backbone ʼ.*kaṇṭa3 ʻ backbone, podex, penis ʼ. 2. *kaṇḍa -- . 3. *karaṇḍa -- 4 . (Cf. *kāṭa -- 2 , *ḍākka -- 2 : poss. same as káṇṭa -- 1 ]1. Pa. piṭṭhi -- kaṇṭaka -- m. ʻ bone of the spine ʼ; Gy. eur. kanro m. ʻ penis ʼ (or < káṇṭaka -- ); Tir. mar -- kaṇḍḗ ʻ back (of the body) ʼ; S. kaṇḍo m. ʻ back ʼ, L. kaṇḍ f., kaṇḍā m. ʻ backbone ʼ, awāṇ. kaṇḍ, °ḍī ʻ back ʼ; P. kaṇḍ f. ʻ back, pubes ʼ; WPah. bhal. kaṇṭ f. ʻ syphilis ʼ; N. kaṇḍo ʻ buttock, rump, anus ʼ, kaṇḍeulo ʻ small of the back ʼ; B. kã̄ṭ ʻ clitoris ʼ; Or. kaṇṭi ʻ handle of a plough ʼ; H. kã̄ṭā m. ʻ spine ʼ, G. kã̄ṭɔ m., M. kã̄ṭā m.; Si. äṭa -- kaṭuva ʻ bone ʼ, piṭa -- k° ʻ backbone ʼ.2. Pk. kaṁḍa -- m. ʻ backbone ʼ.(CDIAL 2670) కరాళము karāḷamu karāḷamu. [Skt.] n. The backbone. వెన్నెముక (Telugu) Rebus: khār खार् 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

bhāthī m. ʻ warrior ʼ bhaTa 'warrior' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace', thus reinforcing the smelting process in the fire-altars. Smelters might have used bhaThi 'bellows'. bhástrā f. ʻ leathern bag ʼ ŚBr., ʻ bellows ʼ Kāv., bhastrikā -- f. ʻ little bag ʼ Daś. [Despite EWA ii 489, not from a √bhas ʻ blow ʼ (existence of which is very doubtful). -- Basic meaning is ʻ skin bag ʼ (cf. bakura <-> ʻ bellows ʼ ~ bākurá -- dŕ̊ti -- ʻ goat's skin ʼ), der. from bastá -- m. ʻ goat ʼ RV. (cf.bastājina -- n. ʻ goat's skin ʼ MaitrS. = bāstaṁ carma Mn.); with bh -- (and unexpl. -- st -- ) in Pa. bhasta -- m. ʻ goat ʼ, bhastacamma -- n. ʻ goat's skin ʼ. Phonet. Pa. and all NIA. (except S. with a) may be < *bhāsta -- , cf. bāsta -- above (J. C. W.)]With unexpl. retention of -- st -- : Pa. bhastā -- f. ʻ bellows ʼ (cf. vāta -- puṇṇa -- bhasta -- camma -- n. ʻ goat's skin full ofwind ʼ), biḷāra -- bhastā -- f. ʻ catskin bag ʼ, bhasta -- n. ʻ leather sack (for flour) ʼ; K. khāra -- basta f. ʻ blacksmith's skin bellows ʼ; -- S. bathī f. ʻ quiver ʼ (< *bhathī); A. Or. bhāti ʻ bellows ʼ, Bi. bhāthī, (S of Ganges) bhã̄thī; OAw. bhāthā̆ ʻ quiver ʼ; H. bhāthā m. ʻ quiver ʼ, bhāthī f. ʻ bellows ʼ; G. bhāthɔ,bhātɔ, bhāthṛɔ m. ʻ quiver ʼ (whence bhāthī m. ʻ warrior ʼ); M. bhātā m. ʻ leathern bag, bellows, quiver ʼ, bhātaḍ n. ʻ bellows, quiver ʼ; <-> (X bhráṣṭra -- ?) N. bhã̄ṭi ʻ bellows ʼ, H. bhāṭhī f.Addenda: bhástrā -- : OA. bhāthi ʻ bellows ʼ .(CDIAL 9424) bhráṣṭra n. ʻ frying pan, gridiron ʼ MaitrS. [√bhrajj ]

Pk. bhaṭṭha -- m.n. ʻ gridiron ʼ; K. büṭhHieroglyph: canopy: nau -- maṇḍḗ n. du. ʻ the two sets of poles rising from the thwarts or the two bamboo covers of a boat (?)(CDIAL 9737) ![]() maṇḍapa m.n. ʻ open temporary shed, pavilion ʼ Hariv., °pikā -- f. ʻ small pavilion, customs house ʼ Kād. 2. maṇṭapa -- m.n. lex. 3. *maṇḍhaka -- . [Variation of ṇḍ with ṇṭ supports supposition of non -- Aryan origin in Wackernagel AiGr ii 2, 212: see EWA ii 557. -- Prob. of same origin as

maṇḍapa m.n. ʻ open temporary shed, pavilion ʼ Hariv., °pikā -- f. ʻ small pavilion, customs house ʼ Kād. 2. maṇṭapa -- m.n. lex. 3. *maṇḍhaka -- . [Variation of ṇḍ with ṇṭ supports supposition of non -- Aryan origin in Wackernagel AiGr ii 2, 212: see EWA ii 557. -- Prob. of same origin as maṭha -- 1 and maṇḍa -- 6 with which NIA. words largely collide in meaning and form]1. Pa. maṇḍapa -- m. ʻ temporary shed for festive occasions ʼ; Pk. maṁḍava -- m. ʻ temporary erection, booth covered with creepers ʼ, °viā -- f. ʻ small do. ʼ; Phal. maṇḍau m. ʻ wooden gallery outside a house ʼ; K. manḍav m. ʻ a kind of house found in forest villages ʼ; S. manahũ m. ʻ shed, thatched roof ʼ; Ku. mãṛyā, manyā ʻ resthouse ʼ; N. kāṭhmã̄ṛau ʻ the city of Kathmandu ʼ (kāṭh -- < kāṣṭhá -- ); Or. maṇḍuā̆ ʻ raised and shaded pavilion ʼ, paṭā -- maṇḍoi ʻ pavilion laid over with planks below roof ʼ, muṇḍoi, °ḍei ʻ raised unroofed platform ʼ; Bi. mã̄ṛo ʻ roof of betel plantation ʼ, mãṛuā, maṛ°, malwā ʻ lean -- to thatch against a wall ʼ, maṛaī ʻ watcher's shed on ground without platform ʼ; karã̄ 'wristlets' khār 'blacksmith' kūṭa, 'horn' kūṭa 'company'ʼ, mã̄ḍvɔ m. ʻ booth ʼ, mã̄ḍvī f. ʻ slightly raised platform before door of a house, customs house ʼ, mã̄ḍaviyɔm. ʻ member of bride's party ʼ; M. mã̄ḍav m. ʻ pavilion for festivals ʼ, mã̄ḍvī f. ʻ small canopy over an idol ʼ; Si. maḍu -- va ʻ hut ʼ, maḍa ʻ open hall ʼ SigGr ii 452.2. Ko. māṁṭav ʻ open pavilion ʼ.3. H. mã̄ḍhā, māṛhā, mãḍhā m. ʻ temporary shed, arbour ʼ (cf. OMarw. māḍhivo in 1); -- Ku. mã̄ṛā m.pl. ʻ shed, resthouse ʼ (or < maṇḍa -- 6 ?]*chāyāmaṇḍapa -- .Addenda: maṇḍapa -- : S.kcch. māṇḍhvo m. ʻ booth, canopy ʼ(CDIAL 9734)

Ku. mã̄ṛā m. pl. ʻ shed, resthouse ʼ (if not < *mã̄ṛhā < *maṇḍhaka -- s.v.

maṇḍa

Pa. maṇḍana -- n., Pk. maṁḍaṇa -- n. and adj.; OMarw. māṁḍaṇa m. ʻ ornament ʼ; G. mã̄ḍaṇ n. ʻ decorating foreheads and cheeks of women on festive occasions ʼ. (CDIAL 9739) *maṇḍadhara ʻ ornament carrier ʼ. [

Pa. maṇḍēti ʻ adorns ʼ, Pk. maṁḍēi, °ḍaï; Ash. mū˘ṇḍ -- , moṇ -- intr. ʻ to put on clothes, dress ʼ, muṇḍaāˊ -- tr. ʻ to dress ʼ; K. manḍun ʻ to adorn ʼ, H. maṇḍnā; OMarw. māṁḍaï ʻ writes ʼ; OG. māṁḍīiṁ 3 pl. pres. pass. ʻ are written ʼ, G. mã̄ḍvũ ʻ to arrange, dispose, begin ʼ, M. mã̄ḍṇẽ, Ko. mã̄ṇḍtā.(CDIAL 9741)

Konḍa maṇḍi earthen pan, a covering dish. Pe. manḍi cooking pot. Kui manḍi brass bowl. Kuwi (S.)

mandi basin; (Isr.) maṇḍi plate, bowl. Cf. 4682 Ta. maṇṭai(DEDR 4678)Ta. maṇṭai

mendicant's begging bowl, earthen vessel, head, skull, cranium, brain-pan, top portion as of palms, a standard of measure. Ma. maṇṭa skull; similar objects. Ko. maṇḍ head. To. maḍ id.

Ka. maṇḍe id.; (Hav.) maṇḍage a big jar. Koḍ. maṇḍe head. Tu. maṇḍè large earthen vessel, skull, head. Kor. (M.) maṇḍa, (O. T.) manḍe head. Cf. 4678 Konḍa maṇḍi. / Cf. Skt. (lex.) maṇḍa- head. (DEDR 4682)

Ta. maṇṭu (maṇṭi-) to blaze up, glow; maṭu (-pp-, -tt-) to kindle. Te. maṇḍu to burn, blaze, flame, cause or produce a burning pain, be angry, be in a fury or violent rage, be envious; maṇṭa flame, blaze, burning pain, anger, wrath, fury, envy; maṇḍincu to burn (tr.), inflame, provoke, irritate; maḍḍu great heat, redhot iron, brand; very hot; (K.) mrandu to be consumed by fire, burn. Kol. (Pat., p. 167) manḍeng to burn, scorch(intr.). Nk. manḍ- to burn (intr.). Go. (M.) maṛgānā to blaze; (Ma.) maṛg- to burn (intr.) (Voc. 2745); (Tr.) maṛūstānā to cook in oil (Voc. 2743); (ASu.) maṛū- (curry) to be charred. Kui mṛahpa (mṛaht-) to consume by fire, burn; n. destruction by fire.(DEDR 4680)

Grain market: OAw. māṁḍa m. ʻ a kind of thin cake ʼ, lakh. maṇḍī ʻ grain market ʼ(CDIAL 9735)

Mesopotamian Molded Plaque with Bull-Men Flanking a Tree Trunk Surmounted by a Sun Disc in the Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Photo: “An Indian saint Vakyapaada lookaline--- the so-called Bullman”

From Review: Small but captivating of Oriental Institute Museum

British Museum number103225 Baked clay plaque showing a bull-man holding a post.

Old Babylonian 2000BC-1600BCE Length: 12.8 centimetres Width: 7 centimetres Barcelona 2002 cat.181, p.212 BM Return 1911 p. 66

On this terracotta plaque, the mace is a phonetic determinant of the bovine (bull) ligatured to the body of the person holding the mace. The person signified is: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ (CDIAL 5488) N. ḍāṅro ʻ term of contempt for a blacksmith ʼ "... head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull...Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. British Museum. WCO2652. Bull-manTerracotta plaque. Bull-man holding a post. Mesopotamia, ca. 2000-1600 BCE."

Terracotta. This plaque depicts a creature with the head and torso of a human but the horns, lower body and legs of a bull. Though similar figures are depicted earlier in Iran, they are first seen in Mesopotamian art around 2500 BC, most commonly on cylinder seals, and are associated with the sun-god Shamash. The bull-man was usually shown in profile, with a single visible horn projecting forward. However, here he is depicted in a less common form; his whole body above the waist, shown in frontal view, shows that he was intended to be double-horned. He may be supporting a divine emblem and thus acting as a protective deity.

Old Babylonian, about 2000-1600 BCE From Mesopotamia Length: 12.8 cm Width: 7cm ME 103225 Room 56: Mesopotamia Briish Museum

Baked clay plaques like this were mass-produced using moulds in southern Mesopotamia from the second millennium BCE. While many show informal scenes and reflect the private face of life, this example clearly has magical or religious significance.

Hieroglyph carried on a flagpost by the blacksmith (bull ligatured man: Dhangar 'bull' Rebus: blacksmith')

![Image result for bull man mesopotamia]() A bull man fights a lion. Mesopotamia half 2 Second millennium 1500 BC Iraq

A bull man fights a lion. Mesopotamia half 2 Second millennium 1500 BC Iraq

- Image ID: CFGK83

Lamassu from Dur-Sharrukin. University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Gypsum (?) Neo-Assyrian Period, c. 721–705 BCE

This past Monday, May 13, OI faculty, staff, supporters, volunteers, and friends gathered in the Museum to celebrate the day when the University of Chicago Trustees officially founded the OI 100 years ago! #birthdaycake#lamassu#oi100![Camera 📷]() http://www.charissajohnsonphotography.com

http://www.charissajohnsonphotography.com

http://www.charissajohnsonphotography.com

http://www.charissajohnsonphotography.com Taureau ailé de Khorsabad

- Hero mastering a lion-AO19862

- Reproduction of a winged bull with human head-AO 30043

- Human-headed winged bulls from Sargon II's palace in Dur-Sharrukin, modern Khorsabad (Louvre)

A tetramorph is a symbolic arrangement of four differing elements, or the combination of four disparate elements in one unit. The term is derived from the Greek tetra, meaning four, and morph, shape. A composition of the Four Living Creatures into one tetramorph. Matthew the man, Mark the lion, Luke the ox, and John the eagle.

A tetramorph is a symbolic arrangement of four differing elements, or the combination of four disparate elements in one unit. The term is derived from the Greek tetra, meaning four, and morph, shape. A composition of the Four Living Creatures into one tetramorph. Matthew the man, Mark the lion, Luke the ox, and John the eagle.  Cast from the original in Iraq, this is one of a pair of five-legged lamassuwith lion's feet in Berlin

Cast from the original in Iraq, this is one of a pair of five-legged lamassuwith lion's feet in Berlin The lamassu in Persepolis

The lamassu in PersepolisAn Assyrian winged bull, or lamassu. "In the Middle Bronze Age Assyria was a city state on the Upper Tigris river, named after its capital, the ancient city of Assur.The Assyrians were just to the north of their rivals, the Babylonians. All the kingdoms of ancient Mesopotamia used the cuneiform writing system invented by the Sumerians. Assyrians are an ethnic group whose descendents remain in what is today Iraq, Iran, Turkey and Syria, but who have gone to the Caucasus, North America and Western Europe during the past century. Hundreds of thousands more live in Assyrian diaspora and Iraqi refugee communities in Europe, the former Soviet Union, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, Syria, Jordan, and Lebanon."

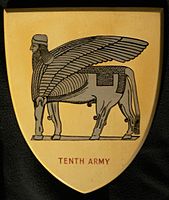

"A lamassu (Cuneiform: 𒀭𒆗, an.kal; Sumerian: dlammař; Akkadian: lamassu; sometimes called a lamassus is an Assyrian protective deity, often depicted as having a human head, the body of a bull or a lion, and bird wings.[3]In some writings, it is portrayed to represent a female deity. A less frequently used name is shedu (Cuneiform: 𒀭𒆘, an.kal×bad; Sumerian: dalad; Akkadian, šēdu), which refers to the male counterpart of a lamassu.[5]Lammasu represent the zodiacs, parent-stars or constellations."

Kriwaczek, Paul. Babylon: Mesopotamia and the Birth of Civilization, p. 37.

http://www.torrossa.it/resources/an/2401509#page=241

Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2003). The Pantheon of Uruk During the Neo-Babylonian Period. Brill.

Black, Jeremy; Green, Anthony (2003). An Illustrated dictionary, Gods, Demons and Symbols of Ancient Mesopotamia. The British Museum Press

Hewitt, J.F. History and Chronology of the Myth-Making Age. p. 85.

W. King, Leonard. Enuma Elish Vol 1 & 2: The Seven Tablets of Creation; The Babylonian and Assyrian Legends Concerning the Creation of the World and of Mankind. p. 78. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lamassu

The British Museum - Human Headed Winged Lions and Reliefs from Nimrudwith the Gates of Balawat

The British Museum - Human Headed Winged Bulls from Dur-Sharrukin

The British Museum - Human Headed Winged Bulls from Dur-Sharrukin The British Museum - Human Headed Winged Lion and Bull from Nimrud, companion pieces in Metropolitan Museum of Art

The British Museum - Human Headed Winged Lion and Bull from Nimrud, companion pieces in Metropolitan Museum of Art Louvre - Human Headed Winged Bulls from Dur-Sharrukin

Louvre - Human Headed Winged Bulls from Dur-Sharrukin Louvre - Human Headed Winged Bulls, Sculpture and Reliefs from Dur-Sharrukin; note the lamassu in the foreground is a cast from the University of Chicago Oriental Institute

Louvre - Human Headed Winged Bulls, Sculpture and Reliefs from Dur-Sharrukin; note the lamassu in the foreground is a cast from the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Louvre - Human Headed Winged Bulls and Reliefs from Dur-Sharrukin, in their wider setting of reliefs

Louvre - Human Headed Winged Bulls and Reliefs from Dur-Sharrukin, in their wider setting of reliefs Louvre - Human Headed Winged Bulls and Reliefs from Dur-Sharrukin

Louvre - Human Headed Winged Bulls and Reliefs from Dur-Sharrukin The Metropolitan Museum of Art - Human Headed Winged Lion and Bull from Nimrud, companion pieces to those in the British Museum

The Metropolitan Museum of Art - Human Headed Winged Lion and Bull from Nimrud, companion pieces to those in the British Museum Detail, University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Gypsum(?), Dur-Sharrukin, entrance to the throne room, c. 721-705 BCE

Detail, University of Chicago Oriental Institute. Gypsum(?), Dur-Sharrukin, entrance to the throne room, c. 721-705 BCE Cuneiform script on the back of a lamassu in the University of Chicago Oriental Institute

Cuneiform script on the back of a lamassu in the University of Chicago Oriental Institute Modern impression of Achaemenidcylinder seal, fifth century BCE. A winged solar disc legitimises the Achaemenid emperor, who subdues two rampant Mesopotamian lamassu figures

Modern impression of Achaemenidcylinder seal, fifth century BCE. A winged solar disc legitimises the Achaemenid emperor, who subdues two rampant Mesopotamian lamassu figures Head of lamassu. Marble, 8th century BCE, from Assur, Iraq. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul

Head of lamassu. Marble, 8th century BCE, from Assur, Iraq. Ancient Orient Museum, Istanbul Head of a lamassu from the palace of Esarhaddon, from Nimrud, Iraq, 7th century BC. The British Museum

Head of a lamassu from the palace of Esarhaddon, from Nimrud, Iraq, 7th century BC. The British Museum Lamassu from the Throne Room (Room B) of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Iraq, 9th century BC. The British Museum, London

Lamassu from the Throne Room (Room B) of the North-West Palace at Nimrud, Iraq, 9th century BC. The British Museum, London Insignia of the British 10th Army "The British 10th Army, which operated in Iraq and Iran in 1942–1943, adopted the lamassu as its insignia. A bearded man with a winged bull body appears on the logo of the United States Forces – Iraq."

Insignia of the British 10th Army "The British 10th Army, which operated in Iraq and Iran in 1942–1943, adopted the lamassu as its insignia. A bearded man with a winged bull body appears on the logo of the United States Forces – Iraq." The entrance of a fire temple in Fort Mumbai displaying a lamassu

The entrance of a fire temple in Fort Mumbai displaying a lamassu Shiva as Sharabha subduing Narasimha (Lord Vishnu), panel view from Munneswaram temple in Sri Lanka. "Sharabha (Sanskrit: शरभ, Śarabha, Kannada: ಶರಭ, Telugu: శరభ) or Sarabha is a part-lion and part-bird beast in Hindu mythology, who, according to Sanskrit literature, is eight-legged and more powerful than a lion or an elephant, possessing the ability to clear a valley in one jump. In later literature, Sharabha is described as an eight-legged deer...Shaiva scriptures narrate that god Shiva assumed the Avatar (incarnation) of Sharabha to pacify Narasimha - the fierce man-lion avatar of Vishnu worshipped by Vaishnava sect. This form is popularly known as Sharabeshwara ("Lord Sharabha") or Sharabeshwaramurti.The Vaishnavas refute the portrayal of Narasimha as being destroyed by Shiva-Sharabha and regard Sharabha as a name of Vishnu. Another tale narrates that Vishnu assumed the form of the ferocious Gandaberunda bird-animal to combat and defeat Sharabha. In Buddhism, Sharabha appears in Jataka Tales as a previous birth of the Buddha.

Shiva as Sharabha subduing Narasimha (Lord Vishnu), panel view from Munneswaram temple in Sri Lanka. "Sharabha (Sanskrit: शरभ, Śarabha, Kannada: ಶರಭ, Telugu: శరభ) or Sarabha is a part-lion and part-bird beast in Hindu mythology, who, according to Sanskrit literature, is eight-legged and more powerful than a lion or an elephant, possessing the ability to clear a valley in one jump. In later literature, Sharabha is described as an eight-legged deer...Shaiva scriptures narrate that god Shiva assumed the Avatar (incarnation) of Sharabha to pacify Narasimha - the fierce man-lion avatar of Vishnu worshipped by Vaishnava sect. This form is popularly known as Sharabeshwara ("Lord Sharabha") or Sharabeshwaramurti.The Vaishnavas refute the portrayal of Narasimha as being destroyed by Shiva-Sharabha and regard Sharabha as a name of Vishnu. Another tale narrates that Vishnu assumed the form of the ferocious Gandaberunda bird-animal to combat and defeat Sharabha. In Buddhism, Sharabha appears in Jataka Tales as a previous birth of the Buddha.Sharabha also appears in the emblem of State government of the Indian state of Karnataka, University of Mysore and the Karnataka Soaps and Detergents Limited...The Chola dynasty in Tamil Nadu was particularly favourable to the beliefs of Shaiva sect. It is said that the sectarian aspect got highlighted during their reign. This is evident from the four Sharabha images, the earliest at the Vikramsolishwaram temple near Kumbakonam built by Vikrama Chola (1118–35). The other images are at Darasuram and Kampahareshvarar temple, Thirubuvanam built by a Chola ruler, Kulottunga Chola III where Sharabha's image is housed in a separate shrine...A sculpture of Sharbeshwaramurti in the Tribhuvanam temple, a Shiva temple in Tanjore district, in Tamil Nadu is seen with three legs, with body and face of a lion and a tail. It has four human arms, the right upper hand holds axe, noose is held in the lower right hand, the deer in the upper left hand and fire in the lower left hand. Narasimha is shown with eight arms in the Airavatesvara Temple at Darasuram, a rare image of the Chola period, in black basalt, depicts Shiva as Sharabha. It is deified in an exclusive small shrine, as part man, beast and bird, destroying the man-lion incarnation of Vishnu, Narasimha. This highlights the hostility between the Shaivite and Vaishnavite sects. In the Chennakeshava temple of Belur (1113), Karnataka, Gandaberunda (2-faced bird identified with Vishnu) depiction is a carved scene of "chain of destruction". Initially, a deer is prey to a large python, followed by being lifted by an elephant and a lion attacking the elephant, and the lion shown as devoured by Sharabha.[15]In Maharashtra the stone cut Sharabha idol is placed on the outer walls of the entrance gate of many historic forts. In iconographic representations of the myth of Shiva vis-à-vis Vishnu, Sharabha form has been built around Narasimha but substantially embellished with wings to represent Kali and Durga to denote the female powers (shaktis) of Shiva; Sharabha is also shown with a bird head and a serpent in his beak head."

Image of Yali at Orchha fort, Madhya Pradesh, India. "Yali/Yāḷi (Sanskrit: याळि, IAST: Yāli) is words derived from Tamil known as Vyala or Vidala in Sanskrit is a mythical creature seen in many South Indian temples, often sculpted onto the pillars. It may be portrayed as part lion, part elephant and part horse, and in similar shapes. Also, it has been sometimes described as a leogryph (part lion and part griffin),[1] with some bird-like features.Descriptions of and references to yalis are very old, but they became prominent in south Indian sculpture in the 16th century. Yalis were believed to be more powerful than the lion, the Tiger or the elephant...In its iconography and image the yali has a catlike graceful body, but the head of a lion with tusks of an elephant (gaja) and tail of a serpent. Sometimes they have been shown standing on the back of a makara, another mythical creature and considered to be the Vahan of Budha (Mercury). Some images look like three-dimensional representation of yalis. Images or icons have been found on the entrance walls of the temples, and the graceful mythical lion is believed to protect and guard the temples and ways leading to the temple. They usually have the stylized body of a lion and the head of some other beast, most often an elephant (gaja-vyala). Other common examples are: the lion-headed (simha-vyala), horse-(ashva-vyala), human-(nir-vyala) and the dog-headed (shvana-vyala) ones." ("Carved Wood bracket - description". British Museum.)

Image of Yali at Orchha fort, Madhya Pradesh, India. "Yali/Yāḷi (Sanskrit: याळि, IAST: Yāli) is words derived from Tamil known as Vyala or Vidala in Sanskrit is a mythical creature seen in many South Indian temples, often sculpted onto the pillars. It may be portrayed as part lion, part elephant and part horse, and in similar shapes. Also, it has been sometimes described as a leogryph (part lion and part griffin),[1] with some bird-like features.Descriptions of and references to yalis are very old, but they became prominent in south Indian sculpture in the 16th century. Yalis were believed to be more powerful than the lion, the Tiger or the elephant...In its iconography and image the yali has a catlike graceful body, but the head of a lion with tusks of an elephant (gaja) and tail of a serpent. Sometimes they have been shown standing on the back of a makara, another mythical creature and considered to be the Vahan of Budha (Mercury). Some images look like three-dimensional representation of yalis. Images or icons have been found on the entrance walls of the temples, and the graceful mythical lion is believed to protect and guard the temples and ways leading to the temple. They usually have the stylized body of a lion and the head of some other beast, most often an elephant (gaja-vyala). Other common examples are: the lion-headed (simha-vyala), horse-(ashva-vyala), human-(nir-vyala) and the dog-headed (shvana-vyala) ones." ("Carved Wood bracket - description". British Museum.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yali_(mythology)

Yali pillars at the Ranganatha temple in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka state, India

Yali pillars at the Ranganatha temple in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka state, India Yali pillars at Bhoganandishvara temple in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka state, India

Yali pillars at Bhoganandishvara temple in Chikkaballapur district, Karnataka state, India Yali pillars at Krishna temple at Hampi, Karnataka state, India

Yali pillars at Krishna temple at Hampi, Karnataka state, India Yali in Aghoreswara temple, Ikkeri, Shivamogga district, Karnataka state, India

Yali in Aghoreswara temple, Ikkeri, Shivamogga district, Karnataka state, India Yali and rider, Mukteshvara Temple, Bhubaneshwar, Odisha state, India

Yali and rider, Mukteshvara Temple, Bhubaneshwar, Odisha state, India Yali and rider, Mukteshvara Temple, Bhubaneshwar, Odisha state, India

Yali and rider, Mukteshvara Temple, Bhubaneshwar, Odisha state, India Yali in Aghoreswara temple, Ikkeri, Shivamogga district, Karnataka state, India

Yali in Aghoreswara temple, Ikkeri, Shivamogga district, Karnataka state, India Yali pillars, Rameshwara Temple, Keladi, Shivamogga District, Karnataka state, Indiahttps://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Yali_pillars_in_mantapa_of_Rameshwara_temple_at_Keladi.jpg/220px-Yali_pillars_in_mantapa_of_Rameshwara_temple_at_Keladi.jpg

Yali pillars, Rameshwara Temple, Keladi, Shivamogga District, Karnataka state, Indiahttps://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/14/Yali_pillars_in_mantapa_of_Rameshwara_temple_at_Keladi.jpg/220px-Yali_pillars_in_mantapa_of_Rameshwara_temple_at_Keladi.jpg Gandaberunda, the Karnataka state emblem, flanked by red maned yellow lion elephant Sharabha. "The Royal Emblem of Mysore has also been adopted by the University of Mysore as their logo too. This logo displays Gandabherunda flanked on either side by the lion-elephant - stronger than the lion and the elephant and defender of uprightness, surmounted by a lion." ("The University Emblem". University of Mysore.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sharabha

Gandaberunda, the Karnataka state emblem, flanked by red maned yellow lion elephant Sharabha. "The Royal Emblem of Mysore has also been adopted by the University of Mysore as their logo too. This logo displays Gandabherunda flanked on either side by the lion-elephant - stronger than the lion and the elephant and defender of uprightness, surmounted by a lion." ("The University Emblem". University of Mysore.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sharabha Narasimha transformed into Gandaberunda, to combat Sharabha. Ashtamukha Gandaberunda Narasimha slaying Sharabha and Hiranyakashipu, depicted in his lap.

Narasimha transformed into Gandaberunda, to combat Sharabha. Ashtamukha Gandaberunda Narasimha slaying Sharabha and Hiranyakashipu, depicted in his lap. Two-headed Sharabha with four legs.

Two-headed Sharabha with four legs. Sharabha idol on Kothaligad fort.

Sharabha idol on Kothaligad fort.(Pattanaik, Devdutt (2006). Shiva to Shankara decoding the phallic symbol. Sharabha (Shiva Purana). Indus Source. pp. 123–124; Waradpande, N. R. (2000). The mythical Aryans and their invasion. Sharabha. Books & Books. pp. 43, 46; Smith, David (2003). The Dance of Siva Religion, Art and Poetry in South India Volume 7 of Cambridge Studies in Religious Traditions. Cambridge University Press. p. 193; "Gandaberunda- The Two Headed Bird". Kamat Potpourri; Kramrisch, Stella (1994). The Presence of Siva. Princeton University Press. p. 436.)

शरभ m. a kind of deer or (in later times) a fabulous animal (supposed to have eight legs and to inhabit the snowy mountains ; it is represented as stronger than the lion and the elephant ; cf. अष्ट-पद् and महा-स्कन्धिन्) AV. &c; (pl.) N. of a people MBh. (B. शबर)(Monier-Williams)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sharabha

Chedi Kingdom and other Mahajanapadas in the Post Vedic period. "Chedi was an ancient Indian kingdom which fell roughly in the Bundelkhand division of Madhya Pradesh regions to the south of river Yamuna along the river Ken. Its capital city was called Suktimati in Sanskrit and Sotthivati-nagara in Pali.In Pali-language Buddhist texts, it is listed as one of the sixteen mahajanapadas ("great realms" of northern and central India). According to the Mahabharata, the Chedi Kingdom was ruled by Shishupala, an ally of Jarasandha of Magadha and Duryodhana of Kuru. He was a rival of Vasudeva Krishna who was his uncle's son. He was killed by Vasudeva Krishna during the Rajasuya sacrifice of the Pandava king Yudhishthira. Bhima's wife was from Chedi. Prominent Chedis during the Kurukshetra War included Damaghosha, Shishupala, Dhrishtaketu, Suketu, Sarabha, Bhima's wife, Nakula's wife Karenumati, Dhrishtaketu's sons. Other Chedis included King Uparichara Vasu, his children, King Suvahu, King Sahaja. It was ruled during early periods by Paurava kings and later by Yadava kings in the central part of the country...The Kuru-Panchalas, the Salwas, the Madreyas, the Jangalas, the Surasenas, the Kalingas, the Vodhas, the Mallas, the Matsyas, the Sauvalyas, the Kuntalas, the Kasi-Kosalas, the Chedis, the Karushas, the Bhojas...(6,9)Chedi was one among the kingdoms chosen for spending the 13th year of exile by the Pandavas.Surrounding the kingdom of the Kurus, are, many countries beautiful and abounding in corn, such as Panchala, Chedi, Matsya, Surasena, Pattachchara, Dasarna, Navarashtra, Malla, Salva, Yugandhara, Saurashtra, Avanti, and the spacious Kuntirashtra. (4,1)."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chedi_Kingdomhttps://tinyurl.com/y3dwju97

Citragupta is a quintessential accountant, a keeper of accounts, wealth-accounting ledgers. This tradition is traceable to R̥gveda and Indus Script Corpora.

-- Bull anthropomorphs, Kubera of navanidhi fame and Citragupta, accountant.

-- Citragupta is born of kāya, 'the body of Brahma' and hence, called kāyasta, 'guild of merchants'.

-- The name citragupta is instructive; citra signifies hieroglyphic writing and gupta signifies a cipher and is a synonym of mlecchita vikalpa 'alternative messaging by mleccha,meluhha 'copper artisans, dialect-speakers who mispronounce words and expressions'.

-- Lotus stalk held on the hands of Varuna, Kubera, Bull anthropomorphs, Citragupta signify tāmarasa'lotus' rebus: tāmra 'copper'.

This monograph demonstrates that the Indus Script Cipher tradition continues into historical periods and evidenced on rendition of bull anthropomorphs, Kubera and Citragupta on sculptural friezes.

Bull anthropomorphs, Kubera, Citragupta sculptures hold lotus stalks to signify writing instruments. Hieroglyph: stalk: खोंड khōṇḍa A variety of जोंधळा., holcus sorghum (Marathi) Rebus: kō̃da कोँद 'potter's kiln' (Kashmiri) kāˊṇḍa (kāṇḍá -- TS.) m.n. ʻ single joint of a plant ʼ AV., ʻ arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ cluster, heap ʼ (in tr̥ṇa -- kāṇḍa -- Pāṇ. Kāś.). [Poss. connexion withgaṇḍa -- 2 makes prob. non -- Aryan origin (not with P. Tedesco Language 22, 190 < kr̥ntáti). Prob. ← Drav., cf. Tam. kaṇ ʻ joint of bamboo or sugarcane ʼ EWA i 197]Pa. kaṇḍa -- m.n. ʻ joint of stalk, stalk, arrow, lump ʼ; Pk. kaṁḍa -- , ˚aya -- m.n. ʻ knot of bough, bough, stick ʼ; Ash. kaṇ ʻ arrow ʼ, Kt. kåṇ, Wg. kāṇ, ãdotdot; Pr. kə̃, Dm. kā̆n; Paš. lauṛ. kāṇḍ, kāṇ, ar. kōṇ, kuṛ. kō̃, dar. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ torch ʼ; Shum. kō̃ṛ, kō̃ ʻ arrow ʼ, Gaw. kāṇḍ, kāṇ; Kho. kan ʻ tree, large bush ʼ; Bshk. kāˋ'n ʻ arrow ʼ, Tor. kan m., Sv. kã̄ṛa, Phal. kōṇ, Sh. gil. kōn f. (→ Ḍ. kōn, pl. kāna f.), pales. kōṇ; K. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ stalk of a reed, straw ʼ (kān m. ʻ arrow ʼ ← Sh.?); S. kānu m. ʻ arrow ʼ, ˚no m. ʻ reed ʼ, ˚nī f. ʻ topmost joint of the reed Sara, reed pen, stalk, straw, porcupine's quill ʼ; L. kānã̄ m. ʻ stalk of the reed Sara ʼ, ˚nī˜ f. ʻ pen, small spear ʼ; P. kānnā m. ʻ the reed Saccharum munja, reed in a weaver's warp ʼ, kānī f. ʻ arrow ʼ; WPah. bhal. kān n. ʻ arrow ʼ, jaun. kã̄ḍ; N. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, ˚ṛo ʻ rafter ʼ; A. kã̄r ʻ arrow ʼ; B. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, ˚ṛā ʻ oil vessel made of bamboo joint, needle of bamboo for netting ʼ, kẽṛiyā ʻ wooden or earthen vessel for oil &c. ʼ; Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻ stalk, arrow ʼ; Bi. kã̄ṛā ʻ stem of muñja grass (used for thatching) ʼ; Mth. kã̄ṛ ʻ stack of stalks of large millet ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ wooden milkpail ʼ; Bhoj. kaṇḍā ʻ reeds ʼ; H. kã̄ṛī f. ʻ rafter, yoke ʼ, kaṇḍā m. ʻ reed, bush ʼ (← EP.?); G. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ joint, bough, arrow ʼ, ˚ḍũ n. ʻ wrist ʼ, ˚ḍī f. ʻ joint, bough, arrow, lucifer match ʼ; M. kã̄ḍ n. ʻ trunk, stem ʼ, ˚ḍẽ n. ʻ joint, knot, stem, straw ʼ, ˚ḍī f. ʻ joint of sugarcane, shoot of root (of ginger, &c.) ʼ; Si. kaḍaya ʻ arrow ʼ. -- Deriv. A. kāriyāiba ʻ to shoot with an arrow ʼ.(CDIAL 3023) Rebus: kanda 'fire-altar'.Rebus: kāṇḍā '(metal) equipment'.

What does a Bull anthroporph signify? dangra 'bull' *ḍaṅgara1 ʻ cattle ʼ. 2. *daṅgara -- . [Same as ḍaṅ- gara -- 2 s.v. *ḍagga -- 2 as a pejorative term for cattle] 1. K. ḍangur m. ʻ bullock ʼ, L. ḍaṅgur, (Ju.) ḍ̠ãgar m. ʻ horned cattle ʼ; P. ḍaṅgar m. ʻ cattle ʼ, Or. ḍaṅgara; Bi. ḍã̄gar ʻ old worn -- out beast, dead cattle ʼ, dhūr ḍã̄gar ʻ cattle in general ʼ; Bhoj. ḍāṅgar ʻ cattle ʼ; H. ḍã̄gar, ḍã̄grā m. ʻ horned cattle ʼ.2. H. dã̄gar m. = prec.(CDIAL 5526) rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' (Maithili) became thākur, 'blacksmith' and later royalty. Sculptures of bull anthropomorphs are also shown carrying lotus stalks signifying reed-pens as writing instruments. ṭhakkura m. ʻ idol, deity (cf. ḍhakkārī -- ), ʼ lex., ʻ title ʼ Rājat. [Dis- cussion with lit. by W. Wüst RM 3, 13 ff. Prob. orig. a tribal name EWA i 459, which Wüst considers nonAryan borrowing of śākvará -- : very doubtful] Pk. ṭhakkura -- m. ʻ Rajput, chief man of a village ʼ; Kho. (Lor.) takur ʻ barber ʼ (= ṭ˚ ← Ind.?), Sh. ṭhăkŭr m.; K. ṭhôkur m. ʻ idol ʼ ( ← Ind.?); S. ṭhakuru m. ʻ fakir, term of address between fathers of a husband and wife ʼ; P. ṭhākar m. ʻ landholder ʼ, ludh. ṭhaukar m. ʻ lord ʼ; Ku. ṭhākur m. ʻ master, title of a Rajput ʼ; N. ṭhākur ʻ term of address from slave to master ʼ (f. ṭhakurāni), ṭhakuri ʻ a clan of Chetris ʼ (f. ṭhakurni); A. ṭhākur ʻ a Brahman ʼ, ṭhākurānī ʻ goddess ʼ; B. ṭhākurāni, ṭhākrān, ˚run ʻ honoured lady, goddess ʼ; Or. ṭhākura ʻ term of address to a Brahman, god, idol ʼ, ṭhākurāṇī ʻ goddess ʼ; Bi. ṭhākur ʻ barber ʼ; Mth. ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. ṭhākur ʻ lord, master ʼ; H. ṭhākur m. ʻ master, landlord, god, idol ʼ, ṭhākurāin, ṭhā̆kurānī f. ʻ mistress, goddess ʼ; G. ṭhākor, ˚kar m. ʻ member of a clan of Rajputs ʼ, ṭhakrāṇī f. ʻ his wife ʼ, ṭhākor ʻ god, idol ʼ; M. ṭhākur m. ʻ jungle tribe in North Konkan, family priest, god, idol ʼ; Si. mald. "tacourou"ʻ title added to names of noblemen ʼ (HJ 915) prob. ← Ind.Addenda: ṭhakkura -- : Garh. ṭhākur ʻ master ʼ; A. ṭhākur also ʻ idol ʼ (CDIAL 5488)

The vāhana of Kubera is a mongoose. This hieroglyph signifies

Hieroglyph: magguśa 'mongoose' rebus: maṅginī 'ship'; mañci a large sort of boat, single-masted Pattimar in coasting trade, holding 10-40 tons. He is shown holding a lotus stalk and carries a purse of mongoose skin, signifying him as a seafaring merchant creating the wealth and treasures of a nation.

![]() Portrait of Abdul Karim (the Munshi) by Rudolf Swoboda.This is cognate with Persian word "Munshi (Urdu: مُنشی; Hindi: मुंशी; Bengali: মুন্সী) is a Persian word, originally used for a contractor, writer, or secretary, and later used in the Mughal Empire and British India for native language teachers, teachers of various subjects especially administrative principles, religious texts, science, and philosophy and were also secretaries and translators employed by Europeans." (Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munshi

Portrait of Abdul Karim (the Munshi) by Rudolf Swoboda.This is cognate with Persian word "Munshi (Urdu: مُنشی; Hindi: मुंशी; Bengali: মুন্সী) is a Persian word, originally used for a contractor, writer, or secretary, and later used in the Mughal Empire and British India for native language teachers, teachers of various subjects especially administrative principles, religious texts, science, and philosophy and were also secretaries and translators employed by Europeans." (Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. 19 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Munshi

RV VIII.21.18

![]() Holds lotus stalk, noose, stands on makara. Makara is a composite animal composed of hieroglyphs: crocodile, elephant trunk, feline paws, fish-fins;the Meluhha rebus readings are: (dh)mākara 'composite animal' rebus: dhmākara 'bellows-blower, blacksmith'; kara 'crocodile' rebus: khar 'blacksmith'; karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron'; panja 'feline paws' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'; aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' aya khambhaṛā 'fih-fin' rebus: aya kammaṭa 'iron mint, coiner, coinage'.

Holds lotus stalk, noose, stands on makara. Makara is a composite animal composed of hieroglyphs: crocodile, elephant trunk, feline paws, fish-fins;the Meluhha rebus readings are: (dh)mākara 'composite animal' rebus: dhmākara 'bellows-blower, blacksmith'; kara 'crocodile' rebus: khar 'blacksmith'; karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron'; panja 'feline paws' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'; aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' aya khambhaṛā 'fih-fin' rebus: aya kammaṭa 'iron mint, coiner, coinage'.

![]() Holds lotus stalk, next to mongoose

Holds lotus stalk, next to mongoose![]() Kubera, hholding mace, lotus stalk, and a mongoose skin purse, with unidentified animal by his side, Jagadambi Temple

Kubera, hholding mace, lotus stalk, and a mongoose skin purse, with unidentified animal by his side, Jagadambi Temple![]() Seated Kubera, with cup, mongoose purse, and lotus stalks, with pots by his side, Kandariya Mahadev Temple

Seated Kubera, with cup, mongoose purse, and lotus stalks, with pots by his side, Kandariya Mahadev Temple

![]()

![]() One of the Ashta Vasus, holding trishul, lotus stalk and Kamandalu, with fire by his side, Chitragupta Temple

One of the Ashta Vasus, holding trishul, lotus stalk and Kamandalu, with fire by his side, Chitragupta Temple![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() One of the Ashta Vasus, holding lotus stalk and scroll, Chitragupta Temple

One of the Ashta Vasus, holding lotus stalk and scroll, Chitragupta Temple

![]()

चित्र--गुप्त m. N. of one of यम's attendants (recorder of every man's good and evil deeds) महाभारत, xiii, स्कन्द-पुराण, नारदीय-पुराण, वराह-पुराण,बादरायण 's ब्रह्म-सूत्र iii , 1 , 15, Sāyaṇa, कथासरित्सागर lxxii ; a secretary of a man of rank (kind of mixed caste) (Monier-Williams) citra चित्र a. [चित्र्-भावे अच्; चि-ष्ट्रन् वा Uṇ.4.163] 1 Bright, clear. -2 Variegated, spotted, diversified. -3 amusing, interesting, agreeable; Māl.1.4. -4 Various, different, manifold; Pt.1.136; Ms.9.248; Y.1.288. -5 Surprising, wonderful, strange; किमत्र चित्रम् R.5.33; Ś.2.15. -6 Perceptible, visible. -7 Conspicuous, excellent, distinguished; न यद्वचश्चित्रपदं हरेर्यशो जगत्पवित्रं प्रगृणीत कर्हिचित् Bhāg.1.5.1. -8 Rough, agitated (as the sea, opp सम). -9 Clear, loud, perceptible (as a sound). -गुप्तः one of the beings in Yama's world recording the vices and virtues of mankind; नामान्येषां लिखामि ध्रुवमहम- धुना चित्रगुप्तः प्रमार्ष्टु Mu.1.2. (Apte)