"Ram Sarup Joon (History of the Jats/Chapter VI, p.115)writes that Dr. Huthi of Georgia paid a visit to India in 1967 and studied the Gujars living in Northern India. He has stated that there are Georgian tribes too among the Gujars because the accent of the Indian Gujars, their dress and their bullock carts resemble that of the Georgians. Dr. Huthi is of the view that they came to India when Timur let loose a reign of terror over them and consequently they settled here. They came here to protect their lives and religion and called themselves "Georgian", "Jorjars",. Later this word was changed into Gujjar..."Georgia" is an exonym, used in the West since the medieval period. It is presumably derived from the Persian designation of the Georgians, gurğ, ğurğ, borrowed around the time of the First Crusade, ultimately derived from the Middle Persian varkâna, meaning "land of Varkas"...Early modern authors such as Jean Chardin tried to link the name to the literal meaning of Greek γεωργός ("tiller of the earth; agriculturalist")."

Who were the Gurjara-Pratīhāras?

V. B. Mishra

Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Vol. 35, No. 1/4 (1954), pp. 42-53 (12 pages)

A rebuttal of Shanta Rani sharmas arguments-and of hersupporters

Posted on November 18, 2015 by gurjaradesa

Shanta Rani Sharma published an article named “Explodingthe Myth of the Gūjara Identity of the Imperial Pratihāras“. In this article she mentions the Gallaka inscription which states that Nagabhata I defeated the “invincible Gurjaras”. Naghabhatta I was the first king of the Imperial Pratihara dynasty, Shanta Rani implies that Gallaka’s inscription is conclusive and unambiguous evidence that Pratiharas were not Gurjaras.

She further asserts that Pratiharas such as Mathanadeva and Hariraja were known as Gurjaras because of their nationality not ethnicity; as she believes that beside the ethnic people called Gurjara, the nationals of Gurjaradesa (Gurjara Country) were also known as Gurjara.

The short response:

Gallaka’s inscription cannot be regarded as conclusive and unambiguous evidence that Gurjaras and Pratiharas were two different people.

The fact that the Pratihara king Naghabatta I defeated the “invincible Gurjaras” has no bearing on his Gurjara ethnicity. For example, the Americans are the descendants of the British people, but they fought each other over the control of North America. So based on this fact, can one deny the British ancestry of Americans? There are many examples in history which show that kings often fought against their own family, tribe, ethnicity, and sometimes even siblings! Therefore, Shanta Rani’s attempt to give Gallaka’s inscription an “ethnic” color is purely subjective and arbitrary. The inscription has no intrinsic value in deciding the matter of Pratihara ethnicity.

On the other hand, we have two instances where Pratihara kings have directly been called “Gurjaras”. Parmashvara Mathanadeva calls himself “Gurjara Pratiharvayah” (Gurjara of Pratihara clan) in his Rajor inscription. On a point of importance, Mathanadeva was not a mere chief or feudotory, but a powerful King who styled himself with the imperial title “Maharaja Di Raja” (King of Kings). Another powerful Pratihara king, Hariraja, is also called “Garjjad Gurjara” (Ferocious Gurjara) in Kadwaha inscription. This is conclusive proof that Pratiharas were a powerful clan of the Gurjaras.

Other than that, there are two important contemporary testimonies that clearly call Imperial Pratiharas as Gurjaras. Ibn Rustah in his book Al Masalik Wa Mumalik has clearly written that, “In Hind…there is a kingdom whose king is called Al Jurz”. His statement is confirmed by another independent source, namely the Kaneres poet Pampa Bharata. He writes in his book that his patron (a Chalukya King) was the one who defeated “Mahipala” who was a “Gurjara Raja” (Gurjara King).

The Imperial Rashtrakutta sources also confirm the presence of “a strong Gurjara army”. They mention their wars with the “thundering Gurjaras”, and the fact that these wars were “remembered by the old men”. Who were these “thundering Gurjaras” with their “strong Gurjara army” and “clansmen”, that were capable of stepping in a battlefield against the Imperial Rashtrakuttas? Of course, these references were only applicable to Imperial Pratiharas.

The long response:

History is defined as the aggregate of past events, but its interpretation always happens through the present lens. This article will talk about a specific example of how the present point of views can reflect back at history, and in turn, change the narrative of the past.

The medieval dynasties of North India (from 500 CE – 1300 CE), such as the Chahamana (Chauhan), Parmara (Parmar), Chalukya (Solanki), Tomara (Tonwar), and Pratihara (Parihar), are commonly referred to as Rajputs by historians. In fact, the very era of medieval India is often referred to as the Rajput period. However, the name Rajput did not appear in history until 1300 CE! That means they could not have been called by that name during the medieval era.

So what were these people called before that? The answer is, Gurjaras! The term Gurjara is still associated with a large group called Gurjar or Gujar, who are mostly middle-class farmers and landholders, but a segment of them are also nomadic herders! The prevailing viewpoint among historians is that the prominent members of the Chahamana, Parmara, Tomara, Chalukya, and Pratihara families branched-off from their Gurjara (Gurjar) identity, and incorporated themselves into the Rajput confederacy. However, the term Gurjara has become a stumbling block for some historians writing about Rajput history, because of its connection with the Gurjar or Gujar people! Consequently, these historians have resolved to bypass this problem altogether, by using the name Rajput for these dynasties, which were actually called Gurjaras in the past!

The history of the Gurjaras was first discovered during the British Raj. It was around the same time that the medieval era of India came to be known as the “Rajput period”. The prolific author from Gujarat, K.M. Munshi, wrote the following in his book regarding this:

“The whole of the period from 550 to 1300 A.C. is organic…The central theme of this period in the country was the achievement of Gurjara warriors… Modern histories by calling this period the Rajput period still perpetuate the faulty outlook which Col. Todd constructed out of the Agnikula legend a century and a half ago. The name Rajput, given to warriors of the old Gurjaradesa by the Turks and Afghans, coupled with the theories of their foreign origins has created a mist which shuts out the historian’s mind from a true perspective of this period…” (Munshi, 1957, p. IV).

The Pratiharas, often called Gurjara-Pratiharas, were the most prominent among these dynasties. The fact that the Pratiharas were called Gurjaras or Gurjars, before they were known as Rajputs, has lead to a tug-of-war between historians. One group says, that Pratiharas, and other dynasties of medieval North India, were originally Gurjars or Gujars, who branched off into a Rajput confederacy through political empowerment. The second group, which is strongly against a Gurjar origin of prominent Rajput families, has come up with elaborate theories to dissociate the Pratiharas and others from their Gurjara history. The author, B.N. Puri, who wrote his thesis on the Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty at Oxford, had the following to say about the historians which deny the Gurjara history of the Pratiharas:

“It has been proposed by some scholars that the Pratiharas and the Gurjaras were two distinct peoples and the former were in no way related to the latter. This view was first proposed by Dr. Ganguly and later on endorsed by Mr. Haldar and others. Dr. Ganguly obscures his meaning by needless and clumsy inversion of words. Thus, he interprets the expression ‘Gurjara-Pratihara’ in the Rajor inscription of Mathanadeva to mean ‘the Pratihara family of the Gurjara country’, and not the ‘Pratihara clan of the Gurjara tribe’, as translated by others. He later changes his position by arguing that even if the term Gurjara in this connection is taken to have referred to the tribe, the Gurjara origin of the Pratiharas cannot be definitely proved. It can very well be taken to mean that Mathanadeva’s father belonged to the family of Gurjara tribe, and his mother was a member of the Pratihara family. Again, his attempt to show that the references to Gurjaras or Gurjara kings do not apply to the Pratiharas only suggest that he approaches the problem with a view to maintain a particular thesis, as Dr. Majumdar rightly suggests.” (Puri, 1957, p. 13).

So in other words, authors like B.N. Puri, R.C. Majumdar, and others, believe that the historians that deny Gurjara history of the Pratiharas, do so because of their will to stick to a certain narrative of history, i.e. “the Rajput period”. All the prominent historians which have written about Gurjara-Pratiharas in detail agree that they were Gurjaras first and Rajputs second. Authors such as D.R. Bhandarkar, A.M.T. Jackson, Rudolf Hoernel, Georg Buhler, Alexander Cunningham, V.A. Smith, R.S. Tripathi, V.S. Sharma, and many other prominent historians of the time, all believed the Pratiharas to be originally Gurjaras.

This is the very reason that the Pratihara dynasty famously came to be known as Gurjara-Pratihara dynasty.

——————–//——————–

The Rajputs have been portrayed as the real heroes of medieval India from many centuries. They are mentioned in history as the modern representatives of ancient Kshatriyas. However, recent historical surveys of ancient India have proven these notions to be false. It has been shown beyond a shadow of doubt that the word Rajput came into Indian history only in recent times, very likely during Mughal era.

Having said that, any idea that challenges this deeply ingrained notion of Indian society, faces a stiff opposition.

If one contrasts the general image that society has about the words Rajput and Gurjar (Gujjar), the reluctance of some historians to use the term Gurjar for the ancestors of “Rajput kings” is somewhat understandable. It is not that these historians are involved in a conspiracy against Gujjars, rather their intellectual bias, reluctance, and dishonesty are the real culprits.

The true history of the era has been replaced by the concocted histories of the Rajput bards, who instilled these notions into society for repeated generations. The aim of the Rajput bard was simple, to emphasise the noble and valourous lineages of his patrons, which were accorded to them by the Brahmanas! It was the Brahmanas which disclosed (fabricated) these lineages in exchange for generosity shown to them. The tradition of bestowing gifts on Brahamans to acquire a higher social status, was an ancient practice in Northern India, and the Rajputs just followed suit.

However, when a myth is repeated for generations, it takes a life of its own. The image of a medieval Rajput, based on fabricated stories of the Brahmanas, is a myth which has transformed into real history. Consequently, the historians (mostly Brahmanas) which are supposed to remain objective, sometimes also become subjective in front of the deeply rooted notions of their society.

——————–//——————–

A set of historians, which can only be described as intellectually biased, reluctant, or dishonest, have bought the histories of Rajput bards wholesale. In doing so, they have devised arguments, which at the surface look academic, but really are attempts to maintain the status quo!

One of the biggest biases that these historians have shown against Gurjars, is that they try to box them with the lower classes of the society! Then they use this “fact” as justification to say: how could people from a lower social class, eg. mere pastoralists, have anything to do with imperial families? First of all, it cannot be forgotten that often the prestige of an ancient people does not correlate well with their present. For example, looking at the Mughals of today one can hardly imagine the prestige of their past. And secondly, the stereotype of the Gujjars as mere pastoralists, is neither true in history nor present. The Gurjar identity has existed for more than a millenium, and its social ladder has encompassed every class from pastoralists to emperors. Here is what a highly respected social scientist like Brajadulal Chattopadhyaya has to say about this:

“To start with the Pratiharas, despite some laboured attempts to dissociate them from the Gurjaras on the plea that Gurjara, in the ‘Gurjara-Pratihara’ combine represented the country and not the people it would appear that the Pratiharas who rose to prominence sometime in the eighth century were really from the Gurjara stock. In early India, janapada names were commonly interchangeable with tribal names. Secondly, the argument that the Pratiharas could not have emerged from the pastoral Gurjara stock is misplaced, because as early as in the seventh century, the Gurjaras of Nandipuri represented a ruling family. Thirdly, a branch of the Pratiharas in the Alwar area is taken to represent the Bad Gujars. Documents dating from the seventh century suggest a wide distribution of the Gurjaras as a political power in western India, and references to Gurjara commoners may indicate that the political dominance of certain families reflected a process of stratification that had developed within the stock. The Pancatantra evidence which mentions the Gurjara country as providing camels for sale may suggest, though inadequately, pastoralism. The Gurjaras are mentioned as cultivators also in an inscription of a Gurjara Pratihara king Mathana from Rajorgarh in Alwar. It would seem that the Pratiharas like several other Gurjara lineages branched off the Gurjara stock through the channel of political power and the case probably offers parallel to that of the Kusanas who originally a sept of the Yueh-chih rose to political prominence and integrated five different jabgous. Further the fact that some Pratiharas also became brahmanas will find parallel in developments among the Abhiras out of whom emerged Abhira brahmanas, Abhira ksatriyas, Abhira sudras, and so on.” (Chattopadhyaya, 1994, p. 64).

If one looks at the real history, instead of the bardic histories of the Rajputs, it is abundantly clear that the Pratiharas were not Rajputs but Gurjaras. The common argument of the reluctant historians is that since Pratihara princes adopted Rajput identity, their history became one with Rajput history! That is an argument which is logically void, because as far as history is concerned, Gurjaras are still the predecessors of Rajputs. Similarly, the predecessors of the Pratihara princes were still part of the Gurjara identity, before they branched off into a Rajput confederacy. What happened centuries after the fall of Gurjara Pratihara empire, neither changes the identity of the imperial Pratiharas, nor the chronology of historical identities.

It is true that the Imperial Pratiharas tried to branch off from Gurjaras, but that does not change the fact that they hailed from the Gurjara stock. In fact, the important reason they wanted distance from their Gurjara identity was because the idea of them being a tribal people would have impeded their imperial ambitions. To avoid such an outcome, Pratiharas were keen on projecting themselves as Kshatriyas, first and foremost. The Kshatriya identity, rather than Gurjara identity, would have helped them establish a mutual relationship with the subordinate or feudal kings. This was the reason that they emphasized their descent from a Raghuvanshi hero such as Lakshmana. Author, Sanjay Sharma, writes the following regarding this:

“… at local levels and in areas that were traditionally associated with the Gurjaras, the Pratiharas were not wary of the projection of their tribal antecedents. In fact, it might have helped the consolidation of their authority. A tribal background, in its pure form would not have been in line with the idea of kingship, at least in normative terms. Interestingly enough, this very identity was repeatedly referred to in the inscriptions of the Rashtrakutas.” (Sharma, 2006, p. 190).

So while the Gurjara-Pratiharas had strategic reasons for distancing themselves from their tribal identity, their enemies such as the Rashtrakutas, Arabs, and Palas had no such reasons. The contemporaries simply referred to the Pratiharas with their tribal name, Gurjara. The local Pratiharas too were free of the imperial politics, and had no hesitations in referring to themselves as Gurjaras, as Sanjay explains further:

“It is only in the later inscriptions of some of the local rulers, perhaps belonging to the collateral lines of the Pratiharas of Kanauj, that we first come across the projection/self projection of the Gurjara identity. Mathanadeva, a ruler of the Alwar area of Rajasthan, in his Rajor inscription of AD 959-60 claims to have belonged to the Gurjara-Pratihara lineage. Besides this, the Kadwaha fragmentary inscription, which documents the achievements of the line of sages belonging to Saivism, refers, in the context of the grant of some villages, to the paramount king Hariraja, who belonged to the Pratihara family (prasutirgotram pratiharamahisvaranam) and who was the ferocious Gurjjara (garjjad gurjjara meghacanda).” (Sharma, 2006, p. 189).

The Rashtrakutas, who were the worst enemy of the Pratiharas, have also referred to them as Gurjaras in several inscriptions. The following reference lists some of these Rashtrakuta inscriptions:

- The undated and fragmentary Dasavatara cave inscription mentions that Dantidurga gave presents at Ujjain and that the king’s camp was located in a Gurjara palace (in all probability in Ujjain) (Majumdar and Dasgupta, A Comprehensive History of India).

- The Sanjan copper plate inscription of Amoghavarsa (Saka samvat 793 = AD 871) credits Dantidurga with making the Gurjara lord of Ujjainhis door keeper (El, Vol. XVIII,p. 243,11.6-7), perhaps a pun on the Pratihara identity.

- The Baroda plate of Karkka II (AD 812-13) extols Indradeva, who is said to have single-handedly put the lord of the Gurjaras to flight (The Indian Antiquary [henceforth IA], Vol. XII, p. 160, 11. 33-34). The same inscription later says that Karkka gave protection to the ruler of Malwa in the direction of the lord of the Gurjaras, who had become insolent owing to his victory over Gauda and Vanga (Majumdar and Dasgupta, A Comprehensive History of India, p. 455).

- The Bagumra copper plate of Dhruva III of the Gujarat branch (AD 867) says with reference to Dhruva II that ‘he had to face the Gurjaras on one side and Vallabha on the other’ (IA, Vol. XII, p. 188).

- The Nilgunda inscription of Amoghavarsa (AD 866) eulogizes Govinda (also called Jagattunga) for having ‘fettered the people of Kerala and Malwa and Gauda, together with the Gurjaras, those who dwelt in the hill fort of Citrakuta’ (El, Vol. VI, pp. 102-3, 11. 6-7).

- The Karhad Plates of Krsna III (AD 959) say, ‘He who spoke pleasant words, who terrified the Gurjara’ (El, Vol. IV, p. 283, 1. 22). The same plates further say that on hearing the conquest of all the strongholds in the southern region simply by means of an angry glance, the hope about Kalanjara and Citrakuta vanished from the heart of the Gurjara (Ibid., p. 284, 1. 44).

- The Nesarika grant of Govinda III (AD 805) also refers to the defeat of the Gurjara at his hands (El, Vol. XXXIV, p. 130,1. 24). In a later set of verses, he is said to have deprived fourteen kings of their royal insignia, one of whom was the Gurjara (Ibid.).

(Sharma, 2006, p. 188).

The Arab records of the time also mention the Pratihara empire with the name Juzr or Jurz (the Arabic transliterations of the term Gurjara):

“Early Arab geographers also provide valuable information with reference to the question under consideration. Among the important kingdoms of India they mention inter alia Balahara, Juzr or Jurz, and Ruhmi or Rahma (synonymous with Dhm [read Dhaum] or `Dharma’, which term, initially used for Dharmapala, later came to denote, in general, a Pala ruler). The term `Balahara’ has been taken to mean Vallabha (the Rastrakuta king), and Juzr or Jurz refers to the Gurjara ruler. The earliest of these writers, the merchant Sulaiman, who is known to have written around the middle of the ninth century, mentions Balahara as the most eminent [of the] princes of India, whose superiority was widely acknowledged. About Jurz, Sulaiman says that he was at war with Balahara, had numerous forces and was inimical to the Arabs.” Abu Zaidu 1 Hasan of Siraf, who made additions to the work of Sulaiman, provides us with more concrete evidence about the identity of Jurz. While making observations on various social and occupational groups, he refers to `Kanauj, a large country forming the empire of Jurz’. Al Ma’sudi (d. AD 956), another prominent early Arab writer, is said to have visited Multan and Manshura in AD 912 and Cambay in 916. He must have written his account around this lime. With regard to Rahma, he says that his dominions border on those of the king of Jurz on the one side and those of the Balahara on the other, with both of whom he was at war. Ibn Kurdadhbih also refers to the king of Al Jurz as amongst the prominent kings of India.” (Sharma, 2006, p. 189).

These references are enough to prove that the empire of the Pratiharas was indeed known by the name Gurjara, or Pratihara kings were indeed known as Gurjara kings. Historians which reject the obvious interpretation of these historical references, only do so because of their manifest bias rather than historical facts.

——————–//——————–

As noted before, some historians have created a controversy over the term Gurjara. They argue that the term signified not only a tribal, but a geographical, identity as well. According to them, the people who lived in the Gurjara kingdom were also known as Gurjaras. So in essence, there were two types of Gurjaras: tribal-Gurjaras and geographical-Gurjaras.

Authors like Shanta Rani Sharma, which borrow heavily from D.C. Ganguly, argue that Gurjara Pratiharas were geographical-Gurjaras. That they had nothing to do with tribal-Gurjaras, who they identify with present day Gujjars. Furthermore, they believe that Gurjara Pratiharas are the ancestors of Pratihar Rajputs, whose ancestors were only known as Gurjaras (Gurjars, Gujjars) because they lived in the Gurjara kingdom. They use the same argument about the Bargujar (Great-Gujar) clan of the Rajputs, that they were known as Bargujars (Great-Gujars) because they hailed from Gurjaradesa, a.k.a. Gujardes.

The last sentence might have given away the confusing nature of this argument. If everyone from the Gurjara kingdom was known as Gurjara, that means the tribal and geographical distinction must have faded awaywith time. The term Gurjara must have become a broader identity (a nation or ethnicity) then. So, what is the point of defining Gurjar as only a tribal identity today? When the very argument is that the term Gurjara (Gurjar, Gujar) had evolved into an ethnicity (geographical and cultural identity)!

Furthermore, which magic-ball is telling these authors that none of the present day Gujjars have descended from the Gurjara ethnicity (the so called “geographical-gurjaras”)? The claim that Gujjars have only descended from tribal-Gurjaras, and not at all from geographical-Gurjaras, has never been substantiated by these authors with anything. It is just presumed, just like it is presumed that Rajputs are the only people descending from the royal families of medieval era! This brings us back full circle to the “Rajput sponsored, Brahmana composed, Bardic histories (stories)”!

——————–//——————–

Shanta Rani Sharma, has brought a new twist to this theory. She claims to have found the smoking gun of all evidences. She has brought forward Gallaka’s inscription, who was a feudatory of Naghabhatta I. It is a noteworthy inscription because Naghabhatta I was the first imperialking of the Gurjara Pratihara dynasty. Gallaka’s inscriptions mentions that Naghabhatta I was the one who defeated the invincible Gurjaras. This according to S.R. Sharma is unambiguous evidence that Naghabhtta I was not a Gurjara, but an enemy to the Gurjaras!

However, contrary to what Shanta has claimed, the statement in Gallaka’s inscription has no intrinsic value in defining the ethnicity of Pratiharas. This could have easily been a reference to Pratiharas establishing themselves as leaders of the Gurjara stock! A possibility which a respected author like Chattopadhyaya has already accepted and related to a historical example in the following quote:

“… references to Gurjara commoners may indicate that the political dominance of certain families reflected a process of stratification that had developed within the stock… It would seem that the Pratiharas like several other Gurjara lineages branched off the Gurjara stock through the channel of political power and the case probably offers parallel to that of the Kusanas who originally a sept of the Yueh-chih rose to political prominence and integrated five different jabgous (branches).” (Chattopadhyaya, 1994, p. 64).

The interpretation of the Gallaka inscription along the lines of political dominance or supremacy within the same stock makes much more sense, especially when taken with all the contemporary references where Pratiharas have been mentioned as Gurjaras. The process of political dominance among a same people is as old as history itself. To talk about Galakas inscription in purely ethnic terms, in spite of these facts, is simply being unfaithful to history.

Furthermore, the conditions surrounding Naghabhatta I’s reign also support the inference that he might have had to conquer several of the Gurjara lines. The invincible Gurjaras in Galaka’s inscription could very well have been the Broach Gurjaras, who were long-time feudatories of the Chalukyan king, Puleksin. It is possible that when, Nagabhatta I, tried to establish his supremacy over the region, the Broach Gurjaras sided with their previous overlord Puleksin, and hence fought against the Gurjara-Pratiharas. To understand this scenario, the following quote from Puri can be quite helpful:

“The rising tide of the Arab threat which flooded the central and the south-western Peninsula completely submerged the smaller states, and when it had subsided. two strong powers emerged—the Calukyas in the south-west, and the Gurjara-Pratiharas in the north. The leaders of the two families—Avanijanasraya Pulakesiraja and Nagabhata I distinguished themselves by stemming the progress of the Arab incursions in the south-west India and Madhyabharata. The Nausari Plates dated in the year 490 of the Kalacuri era, eulogise the Calukya ruler who defeated the Arabs when they were proceeding towards Navasarika after conquering the Saindhavas, Kacchellas, Surastra, Cavotaka, Maurya and Gurjjara (those of Broach) Kings. In the Central belt—the Gwalior Prasati of Bhoja praises Nagabhata for driving away the Mleechas. The two kings, who hurled back the forces of Islam and caused the ultimate retreat of the marauders, were shrewd enough to take full advantage of the worsening situation, and they integrated those small states which were overrun by the Arab invaders. A bid for supremacy between the two was inevitable, and the absence of any record of Avanijanasraya Pulakesiraja after the year 490 of the Kalacuri era, and the reference to Nagavaloka, the ruling sovereign in the Hansot Plates of Bhartrivaddha, suggest that the Pratihara King Nagavaloka=Nagabhata was triumphant, and his empire extended from Ujjain to the Arabian Sea. The history of this ruler, who was the founder of the Gurjara:Pratihara line, is annaled in several records, other than his own, and it is only by piecing together the information from various sources, that an account of him—his capital, conquests, and his successors can be made available …

Naghbhatta’s achievement against the Arabs inspired confidence in him, and against the Arabs, he decided to unsheath the sword elsewhere. It is not known how, and when, his supremacy was recognised at Broach. The absence of any record of Avanijasraya Pulaksiraja after the year 490 of the Kalacuri era (AD 738-9), and the recognition of Nagavaloka’s (Nagabhata’s) authority at Broach in the Vikrama year 813 (A.D. 756) by the Cahamana feudatory Bhartivaddha II suggests that the Pratihara ruler probably conquered this territory after his clash with the Calukya ruler, who seems to have given way. ” (Puri, 1957, p. 33-37).

In the end, Gallaka’s inscription itself contains no mention of ethnicity, and it can very well be interpreted as a struggle for supremacy within the same people. Therefore, Shanta Rani Sharma’s attempt to give Gallaka’s inscription an ethnic color is purely arbitrary, and it contradicts the known history of the Gurjara Pratiharas.

——————–//——————–

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Munshi, K. M. (1957). Glory that was Gurjara Desa (A.D. 550-1300). Chaupatty, Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

Puri, Baij Nath (1957). The history of the Gurjara-Pratiharas. Munshiram Manoharlal.

Chattopadhyaya, Brajadulal (1994). The Making of Early Medieval India. Oxford University Press.

Sharma, Sanjay (2006). “Negotiating Identity and Status Legitimation and Patronage under the Gurjara-Pratīhāras of Kanauj”, Studies in History, 22 (22): 181–220. https://gurjaradesa.wordpress.com/2015/11/18/a-rebuttal-of-shanta-rani-sharmas-arguments-and-of-her-supporters/

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Hephthalite wearing the crown of Peroz I Late 5th century CE

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Hephthalite bowl. th cent. CE. British Museum.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Hephthalite horseman on British Museum bowl, 460–479 CE.According to Procopius of Caesarea, they were of the same stock as European Huns "in fact as well as in name", but sedentary and white-skinned.

Hephthalite horseman on British Museum bowl, 460–479 CE.According to Procopius of Caesarea, they were of the same stock as European Huns "in fact as well as in name", but sedentary and white-skinned.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Hephthalites bowl details.jpg]()

Hephthalites bowl details

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() Hephtalites(An-mu-lu-chjen). (Hephtalite tamga, after Zuev Yu.A., "Horse Tamgas from Vassal Princedoms (Translation of Chinese composition "Tanghuyao" of 8-10th centuries)", Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences, Alma-Ata, I960, p. 132)

Hephtalites(An-mu-lu-chjen). (Hephtalite tamga, after Zuev Yu.A., "Horse Tamgas from Vassal Princedoms (Translation of Chinese composition "Tanghuyao" of 8-10th centuries)", Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences, Alma-Ata, I960, p. 132)

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

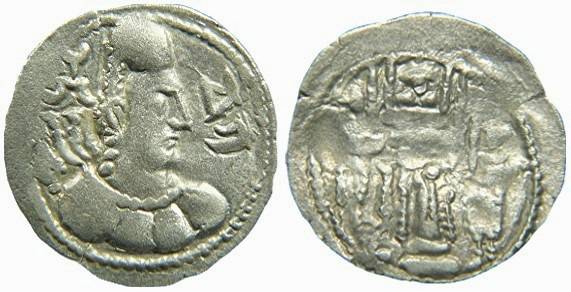

Early Hephthalites settled around Baktria in the mid-300's, and issued coins in the Persian style

Source: http://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=48403

(downloaded June 2006)

"HEPHTHALITES. Baktria? Circa 350 AD. AR Drachm (3.43 gm). Imitating Sasanian king Shahpur I. Tall narrow bust resembling Shapur I; crown with korymbos and earflap / Fire altar flanked by attendants, sprig and caduceus to either side of flames. This apparently unpublished imitative dirhem of Shahpur I is possibly one of the first issues of the Hephthalite tribes that settled in Baktria in the 350s AD and established treaty relations with Shahpur II. The sprig and caduceus symbols on the reverse are not found on any other issue, but they may be intended to mimic the wreath and taurus symbols on contemporary Sasanian coins."

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

The coin of a Hephthalite ruler called Khingila (c.440-490), with a Brahmi inscription, perhaps from a mint at Taxila

Source: http://www.vcoins.com/ancient/dltcoins/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=884&large=1

(downloaded June 2006)

"Hephthalites, Khingila. AR Drachm. c. AD 440-490/ Mint" Taxila (?)/ Obverse Brahmi Khi-Gi (for "Khingila"). Tall, Central-Asian bust right, wearing diadem, earrings and necklace; tamgha behind head. Reverse Fire altar with attendants, bust in flames. Weight 3.59gm Diameter 26mm."

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

A coin issued by a Hephthalite ruler, Raja Lakhana Udayaditya, with a Brahmi inscription, c. late 400's or 500's

Source: http://www.vcoins.com/ancient/dltcoins/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=874&large=1

(downloaded June 2006)

"Hephthalites, Raja Lakhana Udayaditya. AR Drachm; c. late 5th - end 6th century. Obverse: Brahmi legend, Raja Lakhana Udayaditya. Tall Central-Asiatic bust right, wearing diadem with crescent and large earrings. Reverse: Traces of fire altar with attendants design. Weight 3.72gm.Diameter 28mm." [Image and description courtesy of *David L. Tranbarger Rare Coins*.]

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

A coin issued by the "Nezak Malkas" from Kabul in the 600's

Source: http://www.vcoins.com/ancient/dltcoins/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=1179&large=1

(downloaded July 2006)

"Nezak Malkas, Unknown Ruler. AE Drachm, c. AD 630-711. Mint: Kapisa, Kabul. Obverse: Pahlavi legend. Bust r., wearing winged buffalo crown. Reverse: Fire altar with highly stylized attendants, wheel above each. Weight 3.35gm. Diameter 27mm. "Nezak Malka" is generally considered to be a title, not the ruler's personal name. The Nezak Malkas were a Turco-Hephthalite dynasty who ruled Kabul, Ghazni and Gandhara as vassals of the Western Turk Yabghu at Qunduz. In recent years, the dating of these coins has been placed firmly in the 7th century rather than the 6th as previously thought (Gobl, Mitchiner, etc), thus placing the Nezak "Huns" in the Turkic period rather than the Hephthalite." [Image and description courtesy of *David L. Tranbarger Rare Coins*.]

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00routesdata/0400_0499/hunacoins/hunacoins.html

HEPHTHALITE coins

The Hephthalites were nomads who showed up in Iran-Afghanistan-Pakistan-Kashmir starting in the 4th century AD. They came, as all Eurasian nomads did, from the northeast. Their ethnic makeup is unknown at this time. Their cultural aspects are for the most part obscure. It is a matter of debate whether they were related to the Huns who invaded the Roman empire, though they call themselves "Hono" on some of their coins.

Most of their relics are the coins they struck from eastern Iran to India. They captured the Sasanian shah Peroz and held him for ransom. The millions of Sasanian silver coins with which that ransom was paid marked the start of their venture into coinage. They countermarked them and copied them, and went on from there. Hephthalite coinage continued for a few hundred years before the Hephthalites dissolved into the local populations.

Hephthalite coins are all imitative. Most imitate Sasanian types, a few imitate Kushans, and there are some imitations of Greek and Scythian coins that may also be Hephthalite, notwithstanding the half millennium gap between the originals and the the imitations.

It is possible that some of the coins typically classified as Hephthalite these days are not ethnically Hephthalite at all. There are enough gaps in the history of the region to hide large kingdoms and longlived dynasties.

A lot of newly seen Hephthalite types are coming out these days (1990s-2000s). Nice ones in gold and silver can be quite expensive.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, Khingila, c. 430-490 AD, 27mm silver drachm, G-79, tall bust R, RAJA LAKHANA (UDAYA) DITYA / traces of fire altar,

HEPHTHALITE, Khingila, c. 430-490 AD, 27mm silver drachm, G-79, tall bust R, RAJA LAKHANA (UDAYA) DITYA / traces of fire altar,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, Khingila, c. 430-490 AD, 23mm silver drachm, MA-1424v, like Göbl Em. 81, tall moustached bust R, tamgha behind, flowers in vase before / traces of fire altar, Afghanistan issue, compact flan,

HEPHTHALITE, Khingila, c. 430-490 AD, 23mm silver drachm, MA-1424v, like Göbl Em. 81, tall moustached bust R, tamgha behind, flowers in vase before / traces of fire altar, Afghanistan issue, compact flan,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HM1491a) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1491, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, western Afghanistan.

HM1491a) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1491, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, western Afghanistan.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HM1491b) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1491, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, western Afghanistan, small split on edge

HM1491b) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1491, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, western Afghanistan, small split on edge

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() 276-81. HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1493, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, nice style, decent rev., porous obv, crude planchet,

276-81. HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1493, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, nice style, decent rev., porous obv, crude planchet,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1494, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek with "beetle" countermark / fire altar, western Afghanistan, slightly dirty

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1494, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek with "beetle" countermark / fire altar, western Afghanistan, slightly dirty

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1494, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek with "beetle" countermark / wreath(?) rev. I showed this coin to several people, all of whom guessed it was a multiple strike of some sort. I do not find that idea convincing. The "wreath" is poorly struck, apparently nothing is inside. Patinated

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1494, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek with "beetle" countermark / wreath(?) rev. I showed this coin to several people, all of whom guessed it was a multiple strike of some sort. I do not find that idea convincing. The "wreath" is poorly struck, apparently nothing is inside. Patinated

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon 1/4 drachm, MA-1495, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar,

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon 1/4 drachm, MA-1495, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon 1/4 drachm, MA-1495, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, slightly porous

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon 1/4 drachm, MA-1495, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, slightly porous

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, angular S behind / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, angular S behind / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, angular S behind / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region,

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, angular S behind / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region, excellent

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region, excellent

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1501, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1501, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HM1502a) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, excellent

HM1502a) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, excellent

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HM1502b) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki (or Nezak) Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

HM1502b) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki (or Nezak) Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HM1502c) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, superb

HM1502c) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, superb

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HM1502d) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, outstanding

HM1502d) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, outstanding

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502, similar, angular S behind head / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502, similar, angular S behind head / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, silver plated, MA-1507+, bust R with bull head crown, cursive S behind, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, silver plated, MA-1507+, bust R with bull head crown, cursive S behind, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, silver plated, MA-1507+, bust R with bull head crown, cursive S behind, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region, both sides clear

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, silver plated, MA-1507+, bust R with bull head crown, cursive S behind, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region, both sides clear

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1508+, similar, cursive S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1508+, similar, cursive S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1508+, similar, cursive S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1508+, similar, cursive S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1509, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, bits of crust

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1509, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, bits of crust

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1510, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1510, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1510, bust R with bull head crown, Napki (or Nezak) Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul,

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1510, bust R with bull head crown, Napki (or Nezak) Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara, split edge.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara, split edge.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R with tendril hat, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R with tendril hat, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1523v, bust R with trident over moon crown, abbreviated NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, baton before, Gandhara

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1523v, bust R with trident over moon crown, abbreviated NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, baton before, Gandhara

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527, bust R / large tamgha

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527, bust R / large tamgha

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527, bust R / small tamgha

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527, bust R / small tamgha

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527v, bust R / small tamgha

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527v, bust R / small tamgha

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, Sasanian types with Sri Shaho legend in Pahlavi, MA-1529,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() a) nice

a) nice

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() b) a bit crusty

b) a bit crusty

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, MA-1529, Sasanian types with Sri Shaho legend in Pahlavi

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, MA-1529, Sasanian types with Sri Shaho legend in Pahlavi

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 14mm copper (1/8 drachm?), like MA-1529

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 14mm copper (1/8 drachm?), like MA-1529

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, MA-1533, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi / fire altar

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, MA-1533, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi / fire altar

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() 274-42. HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 18mm copper 1/4 drachm, MA-1541, bust R, standard before / fire altar,

274-42. HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 18mm copper 1/4 drachm, MA-1541, bust R, standard before / fire altar,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 13mm copper, 0.7g, MA-1541v1, unusual style

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 13mm copper, 0.7g, MA-1541v1, unusual style

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 12mm copper , 0.1g, Napki type bust R / tamgha like Chach in Uzbekistan!, obv. like MA-1534, rev. see Ziemal

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 12mm copper , 0.1g, Napki type bust R / tamgha like Chach in Uzbekistan!, obv. like MA-1534, rev. see Ziemal

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 11mm copper, 0.6g, Smast type, Zem-x2, imitation of Kujula Herakles type tetradrachm

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 11mm copper, 0.6g, Smast type, Zem-x2, imitation of Kujula Herakles type tetradrachm

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 11mm square copper, 1.4g, imitation of Menander elephant head / club chalkous

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 11mm square copper, 1.4g, imitation of Menander elephant head / club chalkous

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), Kashmir Smast series, 15mm copper, 1.2g, Zem-x4, beardless bust 1/4 R, scepter held in raised L hand / fancifully evolved fire altar with attendants, a bit porous obv.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), Kashmir Smast series, 15mm copper, 1.2g, Zem-x4, beardless bust 1/4 R, scepter held in raised L hand / fancifully evolved fire altar with attendants, a bit porous obv.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), Kashmir Smast series, 9mm square copper, Zem-x5, Sasanian bust R / schematic fire altar.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), Kashmir Smast series, 9mm square copper, Zem-x5, Sasanian bust R / schematic fire altar.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), Kashmir Smast series, 10-13mm, standing king / Ardoksho seated

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), Kashmir Smast series, 10-13mm, standing king / Ardoksho seated

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), Kashmir Smast series, 9mm square copper, Zem-x5, Sasanian bust R / schematic fire altar, crude

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), Kashmir Smast series, 9mm square copper, Zem-x5, Sasanian bust R / schematic fire altar, crude

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 12-13mm copper, standing figure / tripod, types adapted from Apollodotos I bronze

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 12-13mm copper, standing figure / tripod, types adapted from Apollodotos I bronze

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 15mm copper, seated king facing / Zeus R, types adapted from Azes bronze

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 15mm copper, seated king facing / Zeus R, types adapted from Azes bronze

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 12x13mm rectangular copper, fragmentary (elephant head?) / Ardoksho enthroned facing, types adapted from Menander (?) & late Kushan types,

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 12x13mm rectangular copper, fragmentary (elephant head?) / Ardoksho enthroned facing, types adapted from Menander (?) & late Kushan types,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() 274-43. HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, c. 5-6th c. AD, Kashmir Smast series, AE11x12 rectangular, standing king / Ardoksho seated, 1.5g, off center rev.

274-43. HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, c. 5-6th c. AD, Kashmir Smast series, AE11x12 rectangular, standing king / Ardoksho seated, 1.5g, off center rev.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() 274-44. HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, c. 5-6th c. AD, Kashmir Smast series, AE11x12 rectangular, standing king / Ardoksho seated, 1.7g

274-44. HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, c. 5-6th c. AD, Kashmir Smast series, AE11x12 rectangular, standing king / Ardoksho seated, 1.7g

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 21mm, 4.1g, MA-nl, "Gidrifi" style bust R / trace of design, "Narendra" fully written, very unusual with anything on reverse

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 21mm, 4.1g, MA-nl, "Gidrifi" style bust R / trace of design, "Narendra" fully written, very unusual with anything on reverse

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, MA-nl, "Gidrifi" style bust R / blank

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, MA-nl, "Gidrifi" style bust R / blank

***A hoard of these camoe out in late 2007. I know of at least 75 pieces. My guy told me that's all there are but I don't believe it. Such assurances are pretty much never true. So immediately the price is $100 less than it used to be. How low will they go? Only the Shadow knows. And note that I call the bust style "Gidrifi," which is the nickname of the type put out by the Abbasids few centuries later. Probably the Gidrifis should really be nicknamed "Narendroid."

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 22mm, 6g, bust R / blank, "Narendra" fully written

HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 22mm, 6g, bust R / blank, "Narendra" fully written

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 22mm, 6g, bust R / blank, "Narendra" fully written, 22mm, 6.5g

HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 22mm, 6g, bust R / blank, "Narendra" fully written, 22mm, 6.5g

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() 269-92. HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 5.5g, MA-nl, bust R / blank, "Narendra" fully written, slight porosity

269-92. HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 5.5g, MA-nl, bust R / blank, "Narendra" fully written, slight porosity

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() 269-93. HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 6.5g, MA-nl, bust R / blank, "Narendra" barbarously written

269-93. HEPHTHALITE, Gandhara, "Narendra," c. 570-600 AD, billon drachm, 6.5g, MA-nl, bust R / blank, "Narendra" barbarously written

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() 276-83. HEPHTHALITE, NW PAKISTAN, Mihiragula, c. 515-530 AD, copper stater, MA-3779v, haloed king standing / Ardoksho seated facing, 4.5g,

276-83. HEPHTHALITE, NW PAKISTAN, Mihiragula, c. 515-530 AD, copper stater, MA-3779v, haloed king standing / Ardoksho seated facing, 4.5g,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, NW PAKISTAN, Mihiragula, c. 515-530 AD, 21mm copper stater, king standing / Ardoksho seated facing

HEPHTHALITE, NW PAKISTAN, Mihiragula, c. 515-530 AD, 21mm copper stater, king standing / Ardoksho seated facing

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]() HEPHTHALITE, c. 590-610, silver drachm, MA-nl, imitation of Sasanian Hormazd IV, BHL year 11, countermarked tamgha obv. & FORO in cursive Greek rev., shallow obv die, sketchy obv. c/m,

HEPHTHALITE, c. 590-610, silver drachm, MA-nl, imitation of Sasanian Hormazd IV, BHL year 11, countermarked tamgha obv. & FORO in cursive Greek rev., shallow obv die, sketchy obv. c/m,

http://www.anythinganywhere.com/commerce/coins/coinpics/indi-heph.htm

वैश्रवण mf(ई)n. relating or belonging to कुबेर MBh.; m. (fr. वि-श्रवण ; cf. g. शिवा*दि) a patr. (esp. of कुबेर and रावण) AV. &c

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Ancient Coins - INDIA, ALCHON HUNS, Shahi Vaisravana Silver drachm, Göbl 139, VERY RARE & CHOICE!]()

Image may be NSFW.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Hephthalite wearing the crown of Peroz I Late 5th century CE

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Hephthalite bowl. th cent. CE. British Museum.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Hephthalite horseman on British Museum bowl, 460–479 CE.According to Procopius of Caesarea, they were of the same stock as European Huns "in fact as well as in name", but sedentary and white-skinned.

Hephthalite horseman on British Museum bowl, 460–479 CE.According to Procopius of Caesarea, they were of the same stock as European Huns "in fact as well as in name", but sedentary and white-skinned.Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Hephthalites bowl details

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Hephtalites(An-mu-lu-chjen). (Hephtalite tamga, after Zuev Yu.A., "Horse Tamgas from Vassal Princedoms (Translation of Chinese composition "Tanghuyao" of 8-10th centuries)", Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences, Alma-Ata, I960, p. 132)

Hephtalites(An-mu-lu-chjen). (Hephtalite tamga, after Zuev Yu.A., "Horse Tamgas from Vassal Princedoms (Translation of Chinese composition "Tanghuyao" of 8-10th centuries)", Kazakh SSR Academy of Sciences, Alma-Ata, I960, p. 132)Clik here to view.

Source: http://www.cngcoins.com/Coin.aspx?CoinID=48403

(downloaded June 2006)

"HEPHTHALITES. Baktria? Circa 350 AD. AR Drachm (3.43 gm). Imitating Sasanian king Shahpur I. Tall narrow bust resembling Shapur I; crown with korymbos and earflap / Fire altar flanked by attendants, sprig and caduceus to either side of flames. This apparently unpublished imitative dirhem of Shahpur I is possibly one of the first issues of the Hephthalite tribes that settled in Baktria in the 350s AD and established treaty relations with Shahpur II. The sprig and caduceus symbols on the reverse are not found on any other issue, but they may be intended to mimic the wreath and taurus symbols on contemporary Sasanian coins."

Clik here to view.

Source: http://www.vcoins.com/ancient/dltcoins/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=884&large=1

(downloaded June 2006)

"Hephthalites, Khingila. AR Drachm. c. AD 440-490/ Mint" Taxila (?)/ Obverse Brahmi Khi-Gi (for "Khingila"). Tall, Central-Asian bust right, wearing diadem, earrings and necklace; tamgha behind head. Reverse Fire altar with attendants, bust in flames. Weight 3.59gm Diameter 26mm."

Clik here to view.

Source: http://www.vcoins.com/ancient/dltcoins/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=874&large=1

(downloaded June 2006)

"Hephthalites, Raja Lakhana Udayaditya. AR Drachm; c. late 5th - end 6th century. Obverse: Brahmi legend, Raja Lakhana Udayaditya. Tall Central-Asiatic bust right, wearing diadem with crescent and large earrings. Reverse: Traces of fire altar with attendants design. Weight 3.72gm.Diameter 28mm." [Image and description courtesy of *David L. Tranbarger Rare Coins*.]

Clik here to view.

Source: http://www.vcoins.com/ancient/dltcoins/store/viewItem.asp?idProduct=1179&large=1

(downloaded July 2006)

"Nezak Malkas, Unknown Ruler. AE Drachm, c. AD 630-711. Mint: Kapisa, Kabul. Obverse: Pahlavi legend. Bust r., wearing winged buffalo crown. Reverse: Fire altar with highly stylized attendants, wheel above each. Weight 3.35gm. Diameter 27mm. "Nezak Malka" is generally considered to be a title, not the ruler's personal name. The Nezak Malkas were a Turco-Hephthalite dynasty who ruled Kabul, Ghazni and Gandhara as vassals of the Western Turk Yabghu at Qunduz. In recent years, the dating of these coins has been placed firmly in the 7th century rather than the 6th as previously thought (Gobl, Mitchiner, etc), thus placing the Nezak "Huns" in the Turkic period rather than the Hephthalite." [Image and description courtesy of *David L. Tranbarger Rare Coins*.]

http://www.columbia.edu/itc/mealac/pritchett/00routesdata/0400_0499/hunacoins/hunacoins.html

HEPHTHALITE coins

The Hephthalites were nomads who showed up in Iran-Afghanistan-Pakistan-Kashmir starting in the 4th century AD. They came, as all Eurasian nomads did, from the northeast. Their ethnic makeup is unknown at this time. Their cultural aspects are for the most part obscure. It is a matter of debate whether they were related to the Huns who invaded the Roman empire, though they call themselves "Hono" on some of their coins.

Most of their relics are the coins they struck from eastern Iran to India. They captured the Sasanian shah Peroz and held him for ransom. The millions of Sasanian silver coins with which that ransom was paid marked the start of their venture into coinage. They countermarked them and copied them, and went on from there. Hephthalite coinage continued for a few hundred years before the Hephthalites dissolved into the local populations.

Hephthalite coins are all imitative. Most imitate Sasanian types, a few imitate Kushans, and there are some imitations of Greek and Scythian coins that may also be Hephthalite, notwithstanding the half millennium gap between the originals and the the imitations.

It is possible that some of the coins typically classified as Hephthalite these days are not ethnically Hephthalite at all. There are enough gaps in the history of the region to hide large kingdoms and longlived dynasties.

A lot of newly seen Hephthalite types are coming out these days (1990s-2000s). Nice ones in gold and silver can be quite expensive.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, Khingila, c. 430-490 AD, 27mm silver drachm, G-79, tall bust R, RAJA LAKHANA (UDAYA) DITYA / traces of fire altar,

HEPHTHALITE, Khingila, c. 430-490 AD, 27mm silver drachm, G-79, tall bust R, RAJA LAKHANA (UDAYA) DITYA / traces of fire altar, | Obverse | Bust of king right, wearing crescent-crested crown, Brahmi legend around, at left: rajalakhana, at right: udayaditya |

| Reverse | Fire altar, with armed attendants standing left and right, obliterated as usual for these coins |

| Date | c. 5th century CE |

| Weight | 3.55 gm. |

| Diameter | 28-30 mm. |

| Die axis | ? |

| Reference | Göbl Hunnen 79 |

| Comments | Probably issued in Taxila. Note the elongated head typical of these Huns who practiced head binding. Normally the legend for this coin is written as Raja Lakhana Udayaditya, but I have instead written it as Rajalakhana Udayaditya, on the theory that it might be intended to be a conjoined version of Raja Alakhana Udayaditya, i.e., Udayaditya, the Alchon king. A choice specimen, with a bold portrait! The style of Udayaditya's coins reveals that he was a successor of Khingila. |

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, Khingila, c. 430-490 AD, 23mm silver drachm, MA-1424v, like Göbl Em. 81, tall moustached bust R, tamgha behind, flowers in vase before / traces of fire altar, Afghanistan issue, compact flan,

HEPHTHALITE, Khingila, c. 430-490 AD, 23mm silver drachm, MA-1424v, like Göbl Em. 81, tall moustached bust R, tamgha behind, flowers in vase before / traces of fire altar, Afghanistan issue, compact flan, | Obverse | Bust of king right, lunar crescents on shoulder, tamgha at left, medallion or sun wheel at right, Brahmi legend above: Devashahi ... Khingila |

| Reverse | Fire altar, with armed attendants standing left and right, obliterated as usual for these coins |

| Date | c. 5th century CE |

| Weight | 3.60 gm. |

| Diameter | 26.5 mm. |

| Die axis | 3 o'clcock |

| Reference | Göbl Hunnen 81 |

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HM1491a) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1491, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, western Afghanistan.

HM1491a) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1491, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, western Afghanistan. Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HM1491b) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1491, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, western Afghanistan, small split on edge

HM1491b) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1491, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, western Afghanistan, small split on edgeImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

276-81. HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1493, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, nice style, decent rev., porous obv, crude planchet,

276-81. HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1493, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, nice style, decent rev., porous obv, crude planchet,Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1494, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek with "beetle" countermark / fire altar, western Afghanistan, slightly dirty

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1494, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek with "beetle" countermark / fire altar, western Afghanistan, slightly dirty Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1494, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek with "beetle" countermark / wreath(?) rev. I showed this coin to several people, all of whom guessed it was a multiple strike of some sort. I do not find that idea convincing. The "wreath" is poorly struck, apparently nothing is inside. Patinated

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1494, Napki Malka type bust, SRIO SHAHO in cursive Greek with "beetle" countermark / wreath(?) rev. I showed this coin to several people, all of whom guessed it was a multiple strike of some sort. I do not find that idea convincing. The "wreath" is poorly struck, apparently nothing is inside. PatinatedImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon 1/4 drachm, MA-1495, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar,

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon 1/4 drachm, MA-1495, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar,Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon 1/4 drachm, MA-1495, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, slightly porous

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon 1/4 drachm, MA-1495, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar, slightly porousImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, Napki Malka type bust, SRI SHAHO in cursive Greek / fire altar Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, angular S behind / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, angular S behind / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul regionImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region. Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, angular S behind / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region,

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, angular S behind / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region,Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region, excellent

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1500, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region, excellentImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1501, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, silver drachm, MA-1501, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul regionImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HM1502a) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, excellent

HM1502a) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, excellentImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HM1502b) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki (or Nezak) Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

HM1502b) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki (or Nezak) Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/ZabulImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HM1502c) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, superb

HM1502c) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, superbImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HM1502d) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, outstanding

HM1502d) HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502+, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul, outstandingImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul regionImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502, similar, angular S behind head / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1502, similar, angular S behind head / fire altar, Kabul/ZabulImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, silver plated, MA-1507+, bust R with bull head crown, cursive S behind, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, silver plated, MA-1507+, bust R with bull head crown, cursive S behind, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, silver plated, MA-1507+, bust R with bull head crown, cursive S behind, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region, both sides clear

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, silver plated, MA-1507+, bust R with bull head crown, cursive S behind, Napki Malka in Pahlavi / fire altar, Kabul/Zabul region, both sides clearImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1508+, similar, cursive S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1508+, similar, cursive S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/ZabulImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1508+, similar, cursive S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1508+, similar, cursive S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/ZabulImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1509, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, bits of crust

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1509, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, bits of crustImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1510, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1510, bust R with bull head crown, Napki Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendantsImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1510, bust R with bull head crown, Napki (or Nezak) Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul,

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1510, bust R with bull head crown, Napki (or Nezak) Malka in Pahlavi, S behind / fire altar with sun wheels above attendants, Kabul/Zabul, Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara, split edge.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara, split edge. Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R with tendril hat, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R with tendril hat, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, GandharaImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, Gandhara

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1520+, bust R, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, GandharaImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1523v, bust R with trident over moon crown, abbreviated NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, baton before, Gandhara

HEPHTHALITE, c. 475-576 AD, billon drachm, MA-1523v, bust R with trident over moon crown, abbreviated NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi, baton before, GandharaImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527, bust R / large tamgha

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527, bust R / large tamgha Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527, bust R / small tamgha

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527, bust R / small tamghaImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527v, bust R / small tamgha

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper drachm, MA-1527v, bust R / small tamghaHEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, Sasanian types with Sri Shaho legend in Pahlavi, MA-1529,

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

a) nice

a) niceImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

b) a bit crusty

b) a bit crustyImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, MA-1529, Sasanian types with Sri Shaho legend in Pahlavi

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, MA-1529, Sasanian types with Sri Shaho legend in Pahlavi Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 14mm copper (1/8 drachm?), like MA-1529

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 14mm copper (1/8 drachm?), like MA-1529Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, MA-1533, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi / fire altar

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, copper hemidrachm, MA-1533, NAPKI MALKA in Pahlavi / fire altarImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

274-42. HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 18mm copper 1/4 drachm, MA-1541, bust R, standard before / fire altar,

274-42. HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 18mm copper 1/4 drachm, MA-1541, bust R, standard before / fire altar,Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 13mm copper, 0.7g, MA-1541v1, unusual style

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576, 13mm copper, 0.7g, MA-1541v1, unusual styleImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 12mm copper , 0.1g, Napki type bust R / tamgha like Chach in Uzbekistan!, obv. like MA-1534, rev. see Ziemal

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 12mm copper , 0.1g, Napki type bust R / tamgha like Chach in Uzbekistan!, obv. like MA-1534, rev. see ZiemalImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 11mm copper, 0.6g, Smast type, Zem-x2, imitation of Kujula Herakles type tetradrachm

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 11mm copper, 0.6g, Smast type, Zem-x2, imitation of Kujula Herakles type tetradrachmImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 11mm square copper, 1.4g, imitation of Menander elephant head / club chalkous

HEPHTHALITE, GANDHARA, c. 475-576 (?), 11mm square copper, 1.4g, imitation of Menander elephant head / club chalkousImage may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.