https://tinyurl.com/y7vsvtdm

See map of Mesopotamia sites (http://www-oi.uchicago.edu/OI/INFO/MAP/SITE/ANE_Site_Maps.html)

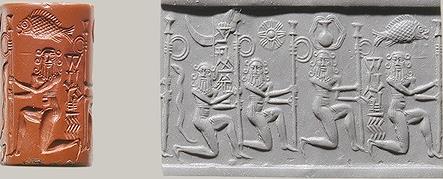

![]() Hieroglyph components on the head-gear of the person on cylinder seal impression are: twig, crucible, buffalo horns: kuThI 'badari ziziphus jojoba' twig Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'; koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer'; tattAru 'buffalo horn' Rebus: ṭhã̄ṭhāro 'brassworker'.

Hieroglyph components on the head-gear of the person on cylinder seal impression are: twig, crucible, buffalo horns: kuThI 'badari ziziphus jojoba' twig Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'; koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer'; tattAru 'buffalo horn' Rebus: ṭhã̄ṭhāro 'brassworker'.

![]() This hieroglyph multiplex ligatures head of an antelope to a snake: nAga 'snake' Rebus: nAga 'lead' ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. tuttināgamu is a Prakritam gloss meaning 'pewter, zinc'. A comparable alloy may be indicated by the hieroglyph-multiplex of antelope-snake: rankunAga, perhaps a type of zinc or lead alloy.

This hieroglyph multiplex ligatures head of an antelope to a snake: nAga 'snake' Rebus: nAga 'lead' ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. tuttināgamu is a Prakritam gloss meaning 'pewter, zinc'. A comparable alloy may be indicated by the hieroglyph-multiplex of antelope-snake: rankunAga, perhaps a type of zinc or lead alloy.

![]() This mkultiplx is flanked by 1. kolom 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; 2. kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smeter'. Thus the message is that the warehouse of cast metal alloy metal implements is complemented by a smelter and a smithy/forge -- part of the metalwork repertoire.

This mkultiplx is flanked by 1. kolom 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; 2. kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smeter'. Thus the message is that the warehouse of cast metal alloy metal implements is complemented by a smelter and a smithy/forge -- part of the metalwork repertoire.

All these hieroglyhphs/hieroglyph-multiplexes are read as metalwork catalogue items in Prakritam which had tadbhava, tatsama identified in Samskritam in Indian sprachbund (speech union).![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Dilmun seals

Dilmun seals

![]()

![Image result for cylinder seal persian gulf]()

![]()

![Stamp seal and modern impression: quadruped]()

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1984.175.15/![Stamp seal and modern impression: horned animal and bird]()

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1984.175.13/

![]() Gulf seal with bucranium (top center), anthropomorph (left), grid, and scorpion (right), as well as bird (Kjærum 1983: 37). karaṇḍa 'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa 'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) bicha 'scorpiion' rebus: bicha 'haematite ore' kaNDa 'divisions' rebus: kaNDa 'implements' muh 'face' rebus: muhA 'quantity of smelted metal taken out of a furnace';'ingot' kaNDa 'arrow' rebus: kaNDA 'implements' kanda 'fire-altar' meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'supercargo'.

Gulf seal with bucranium (top center), anthropomorph (left), grid, and scorpion (right), as well as bird (Kjærum 1983: 37). karaṇḍa 'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa 'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) bicha 'scorpiion' rebus: bicha 'haematite ore' kaNDa 'divisions' rebus: kaNDa 'implements' muh 'face' rebus: muhA 'quantity of smelted metal taken out of a furnace';'ingot' kaNDa 'arrow' rebus: kaNDA 'implements' kanda 'fire-altar' meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'supercargo'.

![]()

Some hieroglyphs which recur on Ancient Near seals and their Meluhha rebus readings:

bull-man, bull ḍangar 'bull' read rebus ḍhangar 'blacksmith'; ṭagara 'ram' Rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian) ṭhakkura, ‘idol’, ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ, ṭhākur m. ʻmaster’.ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). dula ‘pair’.

Rebus: dul 'metal casting'

1. kula '

![]() al-Sindi 1994: no. 17 barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin' kaNDa 'water' rebus: kaNDa 'implements'

al-Sindi 1994: no. 17 barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin' kaNDa 'water' rebus: kaNDa 'implements'

![]() al-Sindi 1994: no. 18 meD 'foot' rebus: meD 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic) barad, balad' ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'

al-Sindi 1994: no. 18 meD 'foot' rebus: meD 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic) barad, balad' ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'

![]() al-Sindi 1994: no. 23 kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'

al-Sindi 1994: no. 23 kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'

![]() Kjærum 1983: no. 212 [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं ) Akid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] 'hard alloy' (Marathi)

Kjærum 1983: no. 212 [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं ) Akid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] 'hard alloy' (Marathi)

![]() Kjærum 1983: no. 81 [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं ) Akid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] 'hard alloy' (Marathi) dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Kjærum 1983: no. 81 [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं ) Akid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] 'hard alloy' (Marathi) dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting'

![]() Kjærum 1983: no. 274 [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं ) Akid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] 'hard alloy' (Marathi) barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'

Kjærum 1983: no. 274 [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं ) Akid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] 'hard alloy' (Marathi) barad, balad 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'

![]() Until now only one single seaal has been discovered (in 2004) which comes from a non-Dilmun cultural environment. It is a cylinder seal with a cuneiform inscription that refers to "Ab-gina, sailor from a huge ship, the son of Ur-Abba" (F. Rahman). This seal provides further evidence of the existing contacts between Dilmun and ancient Mesopotamia at the end of the 3rd- beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE.

Until now only one single seaal has been discovered (in 2004) which comes from a non-Dilmun cultural environment. It is a cylinder seal with a cuneiform inscription that refers to "Ab-gina, sailor from a huge ship, the son of Ur-Abba" (F. Rahman). This seal provides further evidence of the existing contacts between Dilmun and ancient Mesopotamia at the end of the 3rd- beginning of the 2nd millennium BCE.

![]() A minor fragment of a globularly shaped metal sheet may represent a fragment of a vessel.

A minor fragment of a globularly shaped metal sheet may represent a fragment of a vessel. ![]() Blades are technologically more demanding than awls and fish-hooks. A few complete pieces and some major fragments seem to represent knives and perhaps razors.

Blades are technologically more demanding than awls and fish-hooks. A few complete pieces and some major fragments seem to represent knives and perhaps razors.![]() Metal awls are made from thin copper rods of circular or rectangular section. Most of them have both ends pointed. A handful of pieces have simple handles from bird and mammal bones. These awls may have been used for various purposes. Large amounts of shells at the site may indicate that the awls could have served to open and take out the flesh from the shells of bivalves and gastropods.

Metal awls are made from thin copper rods of circular or rectangular section. Most of them have both ends pointed. A handful of pieces have simple handles from bird and mammal bones. These awls may have been used for various purposes. Large amounts of shells at the site may indicate that the awls could have served to open and take out the flesh from the shells of bivalves and gastropods.

![]() Two tanged arrowheads have been found.

Two tanged arrowheads have been found. ![]() From among other utensils, needles with eyes and a pair of tweezers have been uncovered.

From among other utensils, needles with eyes and a pair of tweezers have been uncovered. ![]() Collection of copper fish-hooks.

Collection of copper fish-hooks.![]() Besides vessels, steatite was used for the production of stamp seals and small personal ornaments (pendants). Sherds of broken vessels were further used also as tools (e.g. polishers).

Besides vessels, steatite was used for the production of stamp seals and small personal ornaments (pendants). Sherds of broken vessels were further used also as tools (e.g. polishers).![]()

![]() Typical globular bowl with incised decoration (dotted-circles).

Typical globular bowl with incised decoration (dotted-circles).![]() Small carnelian bead (pointing to link with Gujarat as the possible source of carnelian).

Small carnelian bead (pointing to link with Gujarat as the possible source of carnelian).![]() Net sinker (left) and limestone lid (above). The local limestone was also used for the production of working slabs, grinders and grindstones (below).Pearls were recovered from heavy residue fractions of the soil samples processed by water flotation. They almost exclusively occur in contexts dominated by mother-of-pearl shells.

Net sinker (left) and limestone lid (above). The local limestone was also used for the production of working slabs, grinders and grindstones (below).Pearls were recovered from heavy residue fractions of the soil samples processed by water flotation. They almost exclusively occur in contexts dominated by mother-of-pearl shells.![]() Stamp seal cut from shell nacre layers (above). Pendant made from a strombus shell (left). Semi-product made from an oyster shell (right).

Stamp seal cut from shell nacre layers (above). Pendant made from a strombus shell (left). Semi-product made from an oyster shell (right).

Source. http://www.kuwaitarchaeology.org/gallery/al-khidr-finds-2.html Kuwaiti-Slovak Archaeological Mission

Failaka Island is located approximately 20 km northeast of Kuwait City. The island has a shallow surface measuring 12 km in length and 6 km width. The island proved to be an ideal location for human settlements, because of the wealth of natural resources, including harbours, fresh water, and fertile soil. It was also a strategic maritime commercial route that linked the northern side of the Gulf to the southern side. Studies show that traces of human settlement can be found on Failaka dating back to as early as the end of the 3rd millennium BC and extended through most of the 20th century CE.

Failaka was first known as Agarum, the land of Enzak, the great god of Dilmun civilisation according to Sumerian cuneiform texts found on the island. Dilmun was the leading commercial hub for its powerful neighbours in their need to exchange processed goods for raw materials. Sailing the Arabian Gulf was by far the most convenient trade route at a time as transportation over land meant a much longer and more hazardous journey. As part of Dilmun, Failaka became a hub for the activities which radiated around Dilmun (Bahrain) from the end of the 3rd millennium to the mid-1st millennium BCE.

The cities of Sumer in Mesopotamia, the Harappan people from the Indus Valley, the inhabitants of Magan and the Iranian hinterland have left many archaeological traces of their encounters on Failaka Island. More speculative is the ongoing debate among academics on whether Failaka might be the mythical Eden: the place where Sumerian hero Gilgamesh almost unraveled the secret of immortality; the paradise later described in the Bible.

As a result of changes in the balance of political powers in the region towards the end of the 2nd millennium BCE and beginning of 1st millennium BCE, the importance of Failaka began to decline.

Studies indicate that Alexander the Great received reports from missions sent to explore the Arabian shoreline of the Gulf. The reports referenced two islands, one located approximately 120 stadia (almost 19 km) from an estuary; the second island located a complete day and night sailing journey with proper climate conditions. As the historian Aryan stated, “Alexander the Great ordered that the nearer island be named “Ikaros” (now Failaka) and the distant island as “Tylos” (now the Kingdom of Bahrain). Ikaros was described by the explorers as an island covered with rich vegetation and a shelter for numerous wild animals, considered sacred by the inhabitants who dedicate them to their local goddess.

After the collapse of the great empires in western Asia (Greek, Persian, Roman), the first centuries of the Christian era brought new settlers to Failaka. The island became a secure home for a Christian community, possibly Nestorian, until the 9th century CE. At Al- Qusur, in the centre of the island, archaeologists have uncovered two churches, built at an undetermined date, around which a large settlement grew. Its name may have changed again at that time, to Ramatha.

Failaka was continuously inhabited throughout the Islamic period until the 1990s. Excavations on the Island began in 1958 and continue today. Many archaeological expeditions have worked on Failaka and it is considered one of the key sources of knowledge about civilisations emerging from within the Gulf region.

Brochure at http://darmuseum.org.kw/dai/wp-content/uploads/2013/05/Loans-From-KNM-Brochure.pdf![]() Failaka geography

Failaka geography

![]()

![]()

Failaka (also transcribed as Failakah or Faylakah, and locally known by the names Feileche, Feiliche or Feliche), in antiquity known as Ikaros was mentioned by the Geographer Strabo in ca. 25 AD and later by Arrian. It is the second biggest offshore island of Kuwait situated at the entrance to Kuwait Bay ca. 16 – 17 km far from Ras Al-Ardh in Salmiya and ca. 12 km from Ras As-Sabbiya. It blocks access to the Bay opposite the mouths of the Tigris and Euphrates (Shatt Al-Arab). Failaka has attracted the attention of researchers since 1957 when Danish archaeologists first had the opportunity to study material from the island received from a member of the British political representation to Kuwait. According to the results of up-to-date archaeological research, the ancient history of Failaka goes back to the beginning of the second millennium BC – to the Bronze Age when the Dilmun cultural phenomenon occupied the western shoreline and islands of the Arabian Gulf.

The Dilmun monuments are the most significant antiquities of the history of Failaka and Kuwait. Major Bronze Age sites on Failaka are located on its south-west (Tell Sa’ad/F3; F6; G3), north-west (Al-Khidr) and north-east (Al-Awazim) coasts, one perhaps even being located in the south-east (Al-Sed Al-Aaliy/Matitah) part of the island [6,14]. During the Bronze Age the temple of the god Inzak, tutelary god of Dilmun, existed on Failaka as it is mentioned in the cuneiform and Proto-Aramaic inscriptions on vessel fragments, Dilmun stamp seals and slabs from excavations [5]. In F6, the French excavations revealed buildings interpreted as a tower temple and palace [8].

kaNDa 'divisions' rebus: kaNDa 'implements'

Research Notes--The Middle Asian Interaction Sphere (Gregory Possehl, 2007, Expedition, Vol. 49, No. 1, Spring 2007)

The Copper Hoards of Northern India Paul Yule, 1997, Copper hoards of northern India, Expedition, Vol. 39, No. 1, Spring 1997)

The Indus Civilization and Dilmun, the Sumerian Paradise Land Samuel Noah Kramer, 1964, Expedition, Vol. 6, No. 3, Spring 1964)

The Mythical Massacre at Mohenjo-daro (George F. Dales, 1964, Expedition, Vol. 6, No. 3, Spring 1964)

Shipping and Maritime Trade of the Indus People (S. R. Rao, 1965, Expedition,Vol.7, No. 3, Spring 1965)

The Ganga-Yamuna Basin in the First Millennium B.C. (Vimala S. Begley, Expedition Volume 9, Number 1 Fall 1966)

South Asia's Earliest Writing--Still Undeciphered (George F. Dales, Expedition Volume 9, Number 4 Summer 1967)

The Early Bronze Age of Iran as Seen from Tepe Yahya (C. C. Lamberg-Karlovsky and Philip L. Kohl, Expedition Volume 13, Number 3 - 4 Spring/Summer 1971)

Aspects of Elamite Art and Archaeology (Edith Porada, Expedition Volume 13, Number 3 - 4 Spring/Summer 1971)

Pika Ghosh Expedition Volume 42, Number 3 Winter 2000

The Multiple Landscapes of Vijayanagara--From the Mythic and the Ritual to the Kingly and the Common

Alexandra Mack Expedition Volume 46, Number 2 Summer 2004

Re-Orienting Yoga

Sarah Strauss Expedition Volume 46, Number 3 Winter 2004Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/oapwlyo

'Twisted rope' which is identified as an Indus Script hieroglyph is signified on the following 14 artifacts of Ancient Near East, dated from ca. 2400 to 1650 BCE:![Image result for bogazkoy seal]() Bogazkoy seal impression with 'twisted rope' hieroglyph (Fig. 13) eruvai 'kite' dula 'pair' eraka 'wing' Rebus: eruvai dul 'copper cast metal' eraka'moltencast' PLUS dhāu 'strand of rope' Rebus: dhāv 'red ore' (ferrite) ti-dhāu 'three strands' Rebus: ti-dhāv 'three ferrite ores: magnetite, hematite, laterite'.

Bogazkoy seal impression with 'twisted rope' hieroglyph (Fig. 13) eruvai 'kite' dula 'pair' eraka 'wing' Rebus: eruvai dul 'copper cast metal' eraka'moltencast' PLUS dhāu 'strand of rope' Rebus: dhāv 'red ore' (ferrite) ti-dhāu 'three strands' Rebus: ti-dhāv 'three ferrite ores: magnetite, hematite, laterite'.

Hieroglyph: श्येन m. a hawk , falcon , eagle , any bird of prey (esp. the eagle that brings down सोम to man) RV. (Monier-Williams). This words is expanded in the expression: aśáni f. ʻ thunderbolt ʼRebus: P آهن āhan, s.m. (9th) Iron. Sing. and Pl. آهن ګر āhan gar, s.m. (5th) A smith, a blacksmith. Pl. آهن ګران āhan-garān. آهن ربا āhan-rubā, s.f. (6th) The magnet or loadstone. (E.) Sing. and Pl.); (W.) Pl. آهن رباوي āhan-rubāwī. See اوسپنه .

Fig. 1 First cylinder seal-impressed jar from Taip 1, Turkmenistan

Fig. 2 Hematite cylinder seal of Old Syria ca. 1820-1730 BCE

Fig. 3 Hematite seal. Old Syria. ca. 1720-1650 BCE

Fig. 4 Cylinder seal modern impression. Mitanni. 2nd millennium BCE

Fig. 5 Cylinder seal modern impression. Old Syria. ca. 1720-1650 BCE

Fig. 6 Cylinder seal. Mitanni. 2nd millennium BCE

Fig. 7 Stone cylinder seal. Old Syria ca. 1720-1650 BCE

Fig. 8 Hematite cylinder seal. Old Syria. ca. early 2nd millennium BCE

Fig. 9 Fragment of an Iranian Chlorite Vase. 2500-2400 BCEFig.10 Shahdad standard. ca. 2400 BCE Line drawing

Fig.13 Bogazkoy Seal impression ca. 18th cent. BCE

Hieroglyph: bica 'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'hematite' (Fig.4)

Hieroglyph: karaNDava 'aquatic bird' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy'. (Fig.7)

![Image result for rim of jar meluhha daimabad]() Daimabad seal. Rim of jar hieroglyph. karNI 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo', karNIka 'scribe'.

Daimabad seal. Rim of jar hieroglyph. karNI 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo', karNIka 'scribe'.

Decipherment of Indus Script hieroglyphs:

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/10/indus-script-hieroglyph-twisted-rope-on.html

Sea-faring Meluhhan business in Mesopotamia

It is commonly understood that Meluhhan were sea-faring merchants from the Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization. What was the business of the Meluhhan Ur-Lamma and others in Meluhhan villages in Mesopotamia, in a seaport of Guabba with a temple for Ninmar? Meluhhan bronze is hinted in a text: bronze (uruda) with the Meluhhan village: 6 ma-na uruda me-luh-ha.

Here is a remarkable account by Prof. PS Vermaak on the business of Meluhhan villages in Mesopotamia:

“The Meluhhan granaries. The Meluhhan village was known for its granaries (i-dub e-duru me-luh-ha) and the large amounts of royal barley that were delivered to the town of Girsu. When one calculates the amounts delivered by the Meluhhan granaries in comparison to other regions, towns or villages it was surprisingly high. It cannot exactly be determined why they delivered more barley (up to three times more) than most of the other granaries. It might be that the Meluhhan granaries had a larger region under their premises or perhaps they had to deliver more to the Girsu authorities due to their foreign origin, but this is pure speculation at this stage. There are, however, two t0065ts dating from the sixth year of Amar-Sin (AS 6-vii) and the eighth year of Shu-Sin (SS 8) respectively (from Girsu) where the Meluhhan granary was the only deliverer of the royal barley and it seems that the various granaries had separate monthly instalments to pay (text ASJ 03 152 107). The Meluhhan garden. Some references can be found to the Meluhhan garden (kiri me-luh-ha) in the Neo-Sumerian period, but no more specific details can be derived from these texts except to note that they were connected to the temple of Ninmar. However, several types of Meluhhan artefacts have been identified which probably made up the Meluhhan garden, especially the ab-ba me-luh-ha which is a sort o Meluhhan wood, or the ab-ba could refer to some kind of water feature in a garden…The Meluhhan temples. Two temples have been connected to the Meluhhan village in Ur III Girsu, namely those of the gods’ Nanshe and Nin-mar. In a text where a number of scribes (dub-sar-me) are listed it has been summarized in three interesting lines, namely shu-nigin 6 gurush, arad Nanshe-me, ugula me-luhha (A total of 6 men, servants of the god, Nanshe, while the overseer is a Meluhhan) which definitely seems to connect the Meluhhan village with the temple of Nanshe. This text relates to the temple of Nanshe and the Meluhhan official, which is a good illustration of the Meluhhan s being incorporated into the society of southern Mesopotamia. Another text suggests that the Meluhhans worked in the temple of Nanshe: dumu me-luh-ha erin e Nanshe (‘The Meluhhan worker in the house of Nanshe’). In a balanced account (nig-kas-ak) regarding the different types of barley delivered to the temple of Ninmar (nig-kas ak Lu-Shul-gi shabra she e Nin-MAR.KI) the seal of the well-known Meluhhan appears twice in the text (Kishib Ur-Lamma dumu me-luh-ha). The royal barley deliveries sent to the different gardens (kiri en-ne) in the region of Girsu (year 48 of Shulgi) and the Meluhhan garden was again connected to the temple of Nin-Mar (kiri me-luh-ha Nin-MAR.KI) which was not connected to the Meluhhan temple. This means there had to be two gardens in the same temple of Ninmarki, one as a Meluhhan garden and another one not. The Meluhhan avifauna. The Meluhhan bird (dar me-luh-ha) appears five times in the Ur III texts, only once with the determinative of a bid (mushen). In most of the cases the dar has been listed together with images (alan) which indicates that in these instances the dar probably does not refer to a real bird, but to an image of a bird, maybe as a carved bird (as curio) from wood or ivory. In all instances these texts came from Ur and date from the thirteenth year of Ibbi-Sin. It has been speculated that the dar might be a ‘multi-coloured’ Meluhhan bird, described by Leemans (1960: 166) as a ‘peacock’, but he (Leemans 1968: 222) later corrected himself and regarded it as a kind of a ‘hen’ due to his understanding of it as a bird from ‘India’. The Meluhhan fauna. Although in earlier and later texts references are made to the Meluhhan fauna species from other periods such as the multicoloured Meluhhan dog which was given as a gift to Ibbi-Sin and a Meluhhan cat (Akkadian shuranu) in a Babylonian proverb (Lambert 1960: 272). The only Meluhhan fauna in the Ur III texts is a reference to the goat: mash ga me-luh-ha, ‘the Meluhhan milk goat’. The Meluhhan timber/woods. Special kinds of timber/woods came into southern Mesopotamia from various places such as Magan and Meluhha from the Early Dynastic III to the Gudea period. Lexical texts confirm the import of Meluhhan timber which entered via the ports in the Gulf. Various kinds of Meluhhan wood have been identified during the Ur III and other periods and they were mostly used for different kinds of furniture. The mes-me-luh-ha wood only occurs twice in the Ur III texts, but also continued to be used for furniture and household utensils during the Old Babylonian period (Leemans 160: 126). Its Akkadian equivalent musukkannu was referred to as a Magan and Meluhhan import and it was probably a hard and/or black wood. However, it was locally available during the first millennium BCE (Maxwell-Hyslop 1983: 70-71). The ab-ba me-luh-ha wood had a special purpose to make inter alia special chairs or thrones with ivory inlays. Heimpel (1993: 54) describes it as ‘Meerholz’ which indicates the usage as boat building material, but its Akkadian equivalent is even more well known kushabku.” The Meluhhan bronzes. Since the Uruk III period upto the Gudea period the acquiring of bronzes from the three places Dilmun, Magan en Meluhha was well documented, however during the Ur III period only one reference was found which connects the bronze (uruda) with the Meluhhan village: 6 ma-na uruda me-luh-ha. The Meluhhan village of Guabba.According to the electronic UR III databases there are more than four hundred references in texts mentioning the place name Gu-ab-ba and the texts mostly originate from Girsu/Lagash. Several features immediately come forward when you retrieve these texts, but we will only outline some of these features in order to find the common business of the area concerned…MVN 7 420 = ITT 4 8024…the Meluhhan village often referred to is now connected to the well-known place/village of Gu-ab-ba which is also mentioned twice in this text. It is also linked with a person called Ur-Lamma who has often been mentioned in several other Ur III texts and seals as a Meluhhan (dumu me-luh-ha)...Currently, all 44 texts have been published and are available electronically referring to Meluhha as a place or as a qualifier (a so-called ‘adjective’). On the other hand the place Gu-ab-ba is to be found several hundred times in the Sargonic and Ur III texts…Guabba continued with Meluhha temples…these temples, especially the one of Ninmar, have also been associated with the place of Guabba in earlier periods. One oyal inscription during the time of Ur-Bau in Lagash II dates the year according to the building of temple of Ninmar in Guabba: mu e-nin-mar –ka gu-ab-ba –ka ba-du-a ‘year in which the temple of Ninmar in Guabba was built’ (AO 3355)…In a Sumerian temple hymn (TH 23) Guabba is twice mentioned in connection with the temple of Ninmar…Guabba as a Meluhhan textile hub. .. During the UR III period Guabba provides the largest group of people from Girsu working in the weaving sector, mainly women and children. In one text 4272 women and 1800 children from Guabba are listed as being in the weaving industry (cf. Waetzoldt 1972-94)…if Guabba was indeed a Meluhhan village then one could speculate that this group could have been ancestors of a distant group which diffused into this area, bringing their skills of textiles into the region or being used as cheap labour…Ur-Lamma the Meluhhan of Guabba. Although the name Ur-Lamma occurs several hundred times in the UR III texts, it seems that several persons carried the name Ur-Lamma, because there are often references to the names of their fathers or sons, thus several could be distinguished. However, Ur-Lamma the Meluhhan occurs in a few texts and in seals, but Meluhha occurs only once as a personal name from Guabba…According to the references in texts the personal name Ur-Lamma occurs at least twice in seals from texts, namely Kishib Ur-Lamma dumu me-luh-ha (OBTR 242 = JESHO 20, 135 02)(SH 40)(2x in text) in a financial ‘balanced account’ (nig-kas-ak) and Kishib Ur-Lamma dumu me-luh-ha (UDT 64=CBCY 3, NBC 64). Guabba as a Meluhhan seaport. Guabba has been interpreted as a harbor town under the jurisdiction of Girsu/Lagas due to the literal meaning of the reading gu-ab-ba which did not include the determinative KI for the place name in text SRT 49 II 4, thus gu-ab-ba (‘sea-shore’) instead of the normal gu-ab-ba…Since pre-Sargonic and Sargonic times, references to ‘large boats’ hint at a trading colony which initially had direct contact with their distant ancestors. The following literary document (Lamentation of Sumer and Ur. Michalowski 1989) confirms the previous status: Line 168-169: nin-mar –ra esh gu-ab-ba-ka izi im-ma-da-an-te ku za-gin-bi ma-gal-gal-la bala-she i-ak-e (‘Fire approached Ninmarki in the shrine Guabba (and) large boats were transporting precious metals and gem stones’…one might be able to say that Guabba is a Meluhhan village in southern Mesopotamia…(pp. 556-568) Excerpts from:http://www.scribd.com/doc/21340164/Guabbasemit-v17-n2-a12

Meluhhan (mleccha) speakers were all over India, and also established villages close to Guabba, seaport (not far from Tigris-Euphrates): “In order to form a comprehensive view of the Meluhhan remnants (in Mesopotamia) a variety of texts could be consulted, although they display a picture of a people that have been integrated into the Sumerian and Babylonian cultures much earlier than the Ur III period. ” [i.e., earlier than (2112-2004 BC)] (cf. PS Vermaak, 2008, Guabba, the Meluhhan village in Mesopotamia, Journal of Semitics, 17/2, pp. 553-570). It should be possible to identify mleccha (meluhha) substratum words in Sumerian/Akkadian. One substrate word is sanga 'priest' (Akkadian); cognate with sanghvi 'priest accompanying pilgrims' (Gujarati).

Seal published: The Elamite Cylinder seal corpus: c. 3500-1000 BCE miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati)(

Hieroglyph: stalk, thorny

S. kã̄ḍo ʻ thorny ʼ (CDIAL 3022).kāˊṇḍa (kāṇḍá -- TS.) m.n. ʻ single joint of a plant ʼ AV., ʻ arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ cluster, heap ʼ (in tr̥ṇa -- kāṇḍa -- Pāṇ. Kāś.). [Poss. connexion with gaṇḍa -- 2 makes prob. non -- Aryan origin (not with P. Tedesco Language 22, 190 < kr̥ntáti). Prob. ← Drav., cf. Tam. kaṇ ʻ joint of bamboo or sugarcane ʼ EWA i 197] Pa. kaṇḍa -- m.n. ʻ joint of stalk, stalk, arrow, lump ʼ; Pk. kaṁḍa -- , °aya -- m.n. ʻ knot of bough, bough, stick ʼ; Ash. kaṇ ʻ arrow ʼ, Kt. kåṇ, Wg. kāṇ, kŕãdotdot;, Pr.kə̃, Dm. kā̆n; Paš. lauṛ. kāṇḍ, kāṇ, ar. kōṇ, kuṛ. kō̃, dar. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ torch ʼ; Shum. kō̃ṛ, kō̃ ʻ arrow ʼ, Gaw. kāṇḍ, kāṇ; Kho. kan ʻ tree, large bush ʼ; Bshk. kāˋ'nʻ arrow ʼ, Tor. kan m., Sv. kã̄ṛa, Phal. kōṇ, Sh. gil. kōn f. (→ Ḍ. kōn, pl. kāna f.), pales. kōṇ; K. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ stalk of a reed, straw ʼ (kān m. ʻ arrow ʼ ← Sh.?); S. kānu m. ʻ arrow ʼ, °no m. ʻ reed ʼ, °nī f. ʻ topmost joint of the reed Sara, reed pen, stalk, straw, porcupine's quill ʼ; L. kānã̄ m. ʻ stalk of the reed Sara ʼ, °nī˜ f. ʻ pen, small spear ʼ; P. kānnā m. ʻ the reed Saccharum munja, reed in a weaver's warp ʼ, kānī f. ʻ arrow ʼ; WPah. bhal. kān n. ʻ arrow ʼ, jaun. kã̄ḍ; N. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, °ṛo ʻ rafter ʼ; A. kã̄r ʻ arrow ʼ; B. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, °ṛā ʻ oil vessel made of bamboo joint, needle of bamboo for netting ʼ, kẽṛiyā ʻ wooden or earthen vessel for oil &c. ʼ; Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻ stalk, arrow ʼ; Bi. kã̄ṛā ʻ stem of muñja grass (used for thatching) ʼ; Mth. kã̄ṛ ʻ stack of stalks of large millet ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ wooden milkpail ʼ; Bhoj. kaṇḍā ʻ reeds ʼ; H. kã̄ṛī f. ʻ rafter, yoke ʼ, kaṇḍā m. ʻ reed, bush ʼ (← EP.?); G. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ joint, bough, arrow ʼ, °ḍũ n. ʻ wrist ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint, bough, arrow, lucifer match ʼ; M. kã̄ḍ n. ʻ trunk, stem ʼ, °ḍẽ n. ʻ joint, knot, stem, straw ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint of sugarcane, shoot of root (of ginger, &c.) ʼ; Si. kaḍaya ʻ arrow ʼ. -- Deriv. A. kāriyāiba ʻ to shoot with an arrow ʼ. [< IE. *kondo -- , Gk. kondu/lo s ʻ knuckle ʼ, ko/ndo s ʻ ankle ʼ T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 55] S.kcch. kāṇḍī f. ʻ lucifer match ʼ?(CDIAL 3023) *kāṇḍakara ʻ worker with reeds or arrows ʼ. [kāˊṇḍa -- , kará -- 1 ] L. kanērā m. ʻ mat -- maker ʼ; H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers ʼ.(CDIAL 3024). 3026 kāˊṇḍīra ʻ armed with arrows ʼ Pāṇ., m. ʻ archer ʼ lex. [kāˊṇḍa -- ]H. kanīrā m. ʻ a caste (usu. of arrow -- makers) ʼ.(CDIAL 3026).

Barbar temple, Bahrain and Meluhha hieroglyphs

Copper ? Bull's head. c. 20 cm. high After Fig. 3 in: During Caspers, Elizabeth C.L., 1971, The bull's head from Barbar temple II, Bahrain, a contact with early dynastic Sumer, East and West, Vol. 21, No.3/4, September-December 1971, p.217. The curved style of the horns becomes a way of decorating the crowns of eminent persons on Sumerian, Elamite and Mesopotamian cylinder seals.

ḍhangra ‘bull’ Rebus: ṭhakkura m. ʻ idol, deity (cf. ḍhakkārī -- ), ʼ lex., ʻ title ʼ Rājat. [Dis- cussion with lit. by W. Wüst RM 3, 13 ff. Prob. orig. a tribal name EWA i 459, which Wüst considers nonAryan borrowing ofśākvará -- : very doubtful] Pk. ṭhakkura -- m. ʻ Rajput, chief man of a village ʼ; Kho. (Lor.) takur ʻ barber ʼ (= ṭ° ← Ind.?), Sh. ṭhăkŭr m.; K. ṭhôkur m. ʻ idol ʼ ( ← Ind.?); S. ṭhakuru m. ʻ fakir, term of address between fathers of a husband and wife ʼ; P. ṭhākar m. ʻ landholder ʼ, ludh. ṭhaukar m. ʻ lord ʼ; Ku. ṭhākur m. ʻ master, title of a Rajput ʼ; N. ṭhākur ʻ term of address from slave to master ʼ (f. ṭhakurāni), ṭhakuri ʻ a clan of Chetris ʼ (f. ṭhakurni); A.ṭhākur ʻ a Brahman ʼ, ṭhākurānī ʻ goddess ʼ; B. ṭhākurāni, ṭhākrān, °run ʻ honoured lady, goddess ʼ; Or. ṭhākura ʻ term of address to a Brahman, god, idol ʼ, ṭhākurāṇī ʻ goddess ʼ; Bi. ṭhākur ʻ barber ʼ; Mth.ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ; Bhoj. Aw.lakh. ṭhākur ʻ lord, master ʼ; H. ṭhākur m. ʻ master, landlord, god, idol ʼ, ṭhākurāin, ṭhā̆kurānī f. ʻ mistress, goddess ʼ; G. ṭhākor, °kar m. ʻ member of a clan of Rajputs ʼ, ṭhakrāṇī f. ʻ his wife ʼ, ṭhākor ʻ god, idol ʼ; M. ṭhākur m. ʻ jungle tribe in North Konkan, family priest, god, idol ʼ; Si. mald. "tacourou"ʻ title added to names of noblemen ʼ (HJ 915) prob. ← Ind.Garh. ṭhākur ʻ master ʼ; A. ṭhākur also ʻ idol ʼ AFD 205.(CDIAL 5488)

Seal, Bet Dwaraka 20 x 18 mm of conch shell. Drawing based on a seal from the Harappan port of Dwaraka (After Fig. 5.7 in: Crawford, Harriett EW, 1998, Dilmun and its Gulf neighbours, Cambridge University Press)

The artistic rendering with vivid eyes of the ligatured set of animals is typical Dilmun but the motif is from Meluhha as evidenced by many seals with a comparable ligatured set of animals.

m1169, m1170, m0298 Mohenjo-daro seals which compare with the Dwaraka shell seal of Dilmun type motifs.

Meluhha hieroglyphs read rebus:

sangaḍi = joined animals (M.) Rebus: sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस् ), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, Rebus: sãgaṛh m. ʻline of entrenchments, stone walls for defenceʼ; sangath संगथ् । संयोगः f. (sg. dat. sangüʦü संग&above;च&dotbelow;ू&below; ), association, living together, partnership (e.g. of beggars, rakes, members of a caravan, and so on); jangaḍ ‘entrusted articles on approval basis’. Allograph: sangath संगथ् (of a man or woman) copulation.

tagara 'ram, antelope' Rebus: tagara 'tin'; damgar, tamkāru 'merchant' (Akkadian)

ayo ‘fish’ (Mu.) Rebus: aya = iron (G.); ayah, ayas = metal (Skt.)

mr̤eka ‘goat’. Rebus: milakkhu ‘copper’ Rebus: meṛh ‘helper of merchant’.

kondh ‘young bull’. ‘Pannier’ glyph: खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा, to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) Rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) . कोंद kōnda‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi)

ḍhangra ‘bull’. Rebus: ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

kolom ‘sprout’ Rebus: kolami ‘smithy, forge’ (Telugu)

khareḍo = a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

"Dilmun and the Harappans. The Harapan civilistion played a formative role in the emergence of Bahrain's mercantile tradition. The inhabitants of Bahrain adopted the Harappan weight system. Seven weights conforming to the Harappan series are known from Qala'at al-Bahrain, mainly in City IIa layers, with others found at Saar. The value of a Dilmun standard measure, calculated according to ratio given in an Isin Larsa text from Ur, was found to correspond exactly to a unit in the Harappan system. Harappan script and motifs are found on Persian Gulf seals which are associated with the 3rd milennium...At Saar a number of sherds comparable to Late Sorath Harappan and possibly Jhukar ware have been found...In Gujarat, a Dilmun seal was found at Lothal in unstratified deposits perhaps indicating the presence of Dilmun merchants at that site; a Dilmun-related seal has been reported from Dwarka...the role of the Harappans in the maritime trading system of the late 3rd millennium appears to have been very great." (Carter, Robert, 'Restructuring bronze age trade: Bahrain, southeast Arabia and the copper question, in: Crawford, Harriet, 2003, Archaeology of Bahrain, Proceedings of a seminar held on Monday 14th July 2000, BAR International Series 1189, pp.34, 42)

Unprovenanced Harappan-style cylinder seal impression; Museedu Louvre; cf. Corbiau, 1936, An Indo-Sumerian cylinder, Iraq 3, 100-3, p. 101, Fig.1; De ClercqColl.; burnt white agate; De Clercqand Menant, 1888, No. 26; Collon, 1987, Fig. 614. A hero grasping two tigers and a buffalo-and-leaf-horned person, seated on a stool with hoofed legs, surrounded by a snake and a fish on either side, a pair of water buffaloes. Another person stands and fights two tigers and is surrounded by trees, a markhorgoat and a vulture above a rhinoceros. Text 9905

Hieroglyphs on the cylinder seal impression are: buffalo, tiger, rice-plant, eagle, ram, hooded snake, fish pair, round object (circle), crucible, twigs as part of hair-style of the seated person.

kula 'hooded snake' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'; kolle 'blacksmith' kolhe 'smelter'

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'

The bunch of twigs = kūdī,kūṭī (Samskritam)kūdī (also written as kūṭī in manuscripts) occurs in the Atharvaveda (AV 5.19.12) and KauśikaSūtra (Bloomsfield'sed.n, xliv. cf. Bloomsfield, American Journal of Philology, 11, 355; 12,416; Roth, Festgrussan Bohtlingk, 98) denotes it as a twig. This is identified as that of Badarī, the jujube tied to the body of the dead to efface their traces. (See Vedic Index, I, p. 177). Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

Hieroglyph multiplexes of the hypertext of the cylinder seal from a Near Eastern Source can be identified: aquatic bird, rhinoceros, buffalo, buffalo horn, crucible, markhor, antelope, hoofed stool, fish, tree, tree branch, twig, roundish stone, tiger, rice plant.

Hieroglyph components on the head-gear of the person on cylinder seal impression are: twig, crucible, buffalo horns: kuThI 'badari ziziphus jojoba' twig Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'; koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer'; tattAru 'buffalo horn' Rebus: ṭhã̄ṭhāro 'brassworker'.

Hieroglyph components on the head-gear of the person on cylinder seal impression are: twig, crucible, buffalo horns: kuThI 'badari ziziphus jojoba' twig Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'; koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer'; tattAru 'buffalo horn' Rebus: ṭhã̄ṭhāro 'brassworker'. This hieroglyph multiplex ligatures head of an antelope to a snake: nAga 'snake' Rebus: nAga 'lead' ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. tuttināgamu is a Prakritam gloss meaning 'pewter, zinc'. A comparable alloy may be indicated by the hieroglyph-multiplex of antelope-snake: rankunAga, perhaps a type of zinc or lead alloy.

This hieroglyph multiplex ligatures head of an antelope to a snake: nAga 'snake' Rebus: nAga 'lead' ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'. tuttināgamu is a Prakritam gloss meaning 'pewter, zinc'. A comparable alloy may be indicated by the hieroglyph-multiplex of antelope-snake: rankunAga, perhaps a type of zinc or lead alloy.Two fish hieroglyphs flank the hoofed legs of the stool or platform signify: warehouse of cast metal alloy metal implements:

Hieroglyph: kaṇḍō a stool Rebus: kanda 'implements'

Hieroglyph: maṇḍā 'raised platform, stool' Rebus: maṇḍā 'warehouse'.

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'

ayo 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron' (Gujarati) ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c.(Marathi).

This mkultiplx is flanked by 1. kolom 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; 2. kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smeter'. Thus the message is that the warehouse of cast metal alloy metal implements is complemented by a smelter and a smithy/forge -- part of the metalwork repertoire.

This mkultiplx is flanked by 1. kolom 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; 2. kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi 'smeter'. Thus the message is that the warehouse of cast metal alloy metal implements is complemented by a smelter and a smithy/forge -- part of the metalwork repertoire.The hieroglyph-multiplex of a woman thwarting two rearing tigers is also signified on other seals and tablets to signify:

Hieroglyph: kola 'woman' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS kola 'tiger' Rebus: kolle 'blacksmith'; kolhe 'smeter'; kole.l 'smithy, forge'. The kolmo 'rice-plant' Rebus kolimi 'smithy, forge' is a semantic determinant of the cipher: smithy with smelter.

The bottom register of the cylinder seal impression lists the products: smithy/forge forged iron, alloy castings (laterite PLUS spelter), hard alloy implements.

goTa 'roundish stone' Rebus: gota 'laterite'

dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS rã̄go 'buffalo' Rebus: rāṅgā 'zinc alloy, spelter, pewter'. Thus, cast spelter PLUS laterite.

markhor PLUS tail

miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) koṭe meṛed = forged iron, in contrast to dul meṛed, cast iron (Mundari) PLUS Kur. xolā tail. Malt. qoli id. (DEDR 2135) Rebus: kol 'working in iron' Ta. kol working in iron, blacksmith; kollaṉ blacksmith. Ma. kollan blacksmith, artificer. Ko. kole·l smithy, temple in Kota village.

Rhinoceros PLUS aquatic bird or eagle

Hieroglyhph: kāṇṭā 'rhinoceros. gaṇḍá m. ʻ rhinoceros ʼ Rebus: kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans and metal-ware' (Gujarati)

karaṛa 'large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: karaḍā 'hardalloy of metals' (Marathi) Alternative: eruvai 'kite, eagle' Rebus: eruvai 'copper (red)'

Two water-buffalos flanks a hieroglyph: something round, like a seed. Hieroglyph: rã̄go 'buffalo' Rebus: rāṅgā 'zinc alloy, spelter, pewter'. What does the hieroglyph 'something round' signify? I suggest that it signifies goTa 'laterite (ferrous ore)'.

Persian Gulf seals, 2500-1800 B.C.E. At the British Museum, London.These seals were used in trade in the Persian Gulf. Most were button-shaped, some were cylindrical or differently shaped. The top left seal has an Indus script inscription.

Impression from a cylinder seal. urseal6 Cylinder seal; BM 122947; U. 16220 (cut down into Ur III mausolea from Larsa level; U. 16220), enstatite; Legrain, 1951, No. 632; Collon, 1987, Fig. 611. Humped bull stands before a plant, feeding from a round manger or a bundle of fodder (or, probably, a cactus); behind the bull is a scorpion and two snakes; above the whole a human figure, placed horizontally, with fantastically long arms and legs, and rays about his head.

Rebus reading of scorpion glyph: bicha ‘scorpion’ (Assamese) Rebus:bica ‘stone ore’ (Munda) pola ‘magnetite ore’ (Munda. Asuri); bichi 'scorpion'; 'hematite ore'; tagaraka 'tabernae montana'; tagara 'tin'; ranga 'thorny'; Rebus: pewter, alloy of tin and antimony; kankar., kankur. = very tall and thin, large hands and feet; kankar dare = a high tree with few branches (Santali) Rebus: kanka, kanaka = gold (Samskritam); kan = copper (Tamil) nAga 'snake' nAga 'lead' (Samskritam). पोलाद [ pōlāda ] n (पोलादी a Of steel. (Marathi) bulad 'steel, flint and steel for making fire' (Amharic); fUlAd 'steel' (Arabic)

Stamp seal and modern impression: quadruped

Period: Ubaid-Middle Gawra

Date: ca. 4500–3500 B.C.

Geography: Northern Syria or eastern Anatolia

Medium: Chlorite, black

Dimensions: Seal face: 3.16 x 2.96 cm

Height: .68 cm

String Hole: 0.4 cm

Height: .68 cm

String Hole: 0.4 cm

Classification: Stone-Stamp Seals

Stamp seal and modern impression: horned animal and bird

Period: Ubaid

Date: 6th–5th millennium B.C.

Geography: Syria or Anatolia

Medium: Steatite or chlorite

Dimensions: 0.2 x 0.8 x 0.84 in. (0.51 x 2.03 x 2.13 cm)

Classification: Stone-Stamp Seals

The Ubaid Period (5500–4000 B.C.)

In the period 5500–4000 B.C., much of Mesopotamia shared a common culture, called Ubaid after the site where evidence for it was first found. Characterized by a distinctive type of pottery, this culture originated on the flat alluvial plains of southern Mesopotamia (ancient Iraq) around 6200 B.C. Indeed, it was during this period that the first identifiable villages developed in the region, where people farmed the land using irrigation and fished the rivers and sea (Persian Gulf). Thick layers of alluvial silt deposited every spring by the flooding rivers cover many of these sites. Some villages began to develop into towns and became focused on monumental buildings, such as at Eridu and Uruk. The Ubaid culture spread north across Mesopotamia, gradually replacing the

. Ubaid pottery is also found to the south, along the west coast of the Persian Gulf, perhaps transported there by fishing expeditions. Baked clay figurines, mainly female, decorated with painted or appliqué ornament and lizardlike heads, have been found at a number of Ubaid sites. Simple clay tokens may have been used for the symbolic representation of commodities, and pendants and stamp seals may have had a similar symbolism, if not function. During this period, the repertory of seal designs expands to include snakes, birds, and animals with humans. There is much continuity between the Ubaid culture and the succeeding

, when many of the earlier traditions were elaborated, particularly in architecture.

http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1984.175.13/

Gulf seal with bucranium (top center), anthropomorph (left), grid, and scorpion (right), as well as bird (Kjærum 1983: 37). karaṇḍa 'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa 'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) bicha 'scorpiion' rebus: bicha 'haematite ore' kaNDa 'divisions' rebus: kaNDa 'implements' muh 'face' rebus: muhA 'quantity of smelted metal taken out of a furnace';'ingot' kaNDa 'arrow' rebus: kaNDA 'implements' kanda 'fire-altar' meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'supercargo'.

Gulf seal with bucranium (top center), anthropomorph (left), grid, and scorpion (right), as well as bird (Kjærum 1983: 37). karaṇḍa 'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa 'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) bicha 'scorpiion' rebus: bicha 'haematite ore' kaNDa 'divisions' rebus: kaNDa 'implements' muh 'face' rebus: muhA 'quantity of smelted metal taken out of a furnace';'ingot' kaNDa 'arrow' rebus: kaNDA 'implements' kanda 'fire-altar' meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' karNaka 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'supercargo'.Dilmun seals (35) and decipherment through Indus Script Cipher

I am grateful to Luca Peyronel for selecting the following Dilmun seals from out of hundreds from Failaka, Bahrain and other Persian Gulf sites and categorizing them on iconographic frames (i.e. with the types of hieroglyphs signified on the seals). Peyronel gleans meanings of sacredness and ritual offerings from adorants explaining the iconograhic motifs.

The procedure for gleaning semantics (i.e. decipherment) of the hierolyphs is to treat them as Indus Script Cipher of rebus-metonymy-Meluhha speech renderings of metalwork proclamations.

I, therefore, suggest -- an alternative semantic framework -- that all the 35 Dilmun seals are Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplexes which are technical descriptions for documentation or proclamation as metalwork catalogues.

Proto-Prakritam or Meluhha hieroglyphs and rebus-metonymy readings of the hieroglyph-multiplexes on the 35 Dilmun seals:

Some hieroglyphs which recur on Ancient Near seals and their Meluhha rebus readings:

bull-man, bull ḍangar 'bull' read rebus ḍhangar 'blacksmith'; ṭagara 'ram' Rebus: damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian) ṭhakkura, ‘idol’, ṭhākur ʻ blacksmith ʼ, ṭhākur m. ʻmaster’.ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’.

tiger kol 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'

lion arye 'lion'āra 'brass'

aquatic bird karaḍa ‘aquatic bird, duck’ Rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy'

eagle eraka 'eagle' Rebus: erako 'moltencast copper

buffalo கண்டி kaṇṭi , n. 1. Buffalo bull Rebus: Pk. gaḍa -- n. ʻlarge stoneʼ? (CDIAL 3969)

six hair-curls āra 'six curls' Rebus: āra 'brass'

face mũh ‘face’ Rebus: mũh ‘ingot’.

stag karuman 'stag' karmara 'artisan'

antelope melh 'goat' Rebus: milakkhu 'copper'

calf khoṇḍ 'young bull-calf' Rebus khuṇḍ '(metal) turner'.

scorpion bica ‘scorpion’ (Assamese) Rebus: bica ‘stone ore’

stalk daṭhi, daṭi 'stalks of certain plants' Rebus: dhatu ‘mineral.kāṇḍa काण्डः m. the stalk or stem of a reed. Rebus: kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’.

twig kūdī ‘twig’ Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter’

fish ayo 'fish' Rebus: ayo, ayas 'metal'.

overflowing pot lo ‘pot to overflow’ kāṇḍa ‘water’. Rebus: लोखंड lokhaṇḍ Iron tools, vessels, or articles in general.

spear మేడెము [ mēḍemu ] or మేడియము mēḍemu. [Tel.] n. A spear or dagger. Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’.

ring, bracelet kaḍum a bracelet, a ring (G.) Rebus: kaḍiyo [Hem. Des. kaḍaio = Skt. sthapati a mason] a bricklayer; a mason;

star मेढ [ mēḍha ] The polar star (Marathi). [cf.The eight-pointed star Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Mundari. Remo.)

safflower karaḍa -- m. ʻsafflowerʼ Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

twig kūdī ‘twig’ Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter’

frond (of palm), palm tamar, ‘palm tree, date palm’ Rebus: tam(b)ra, ‘copper’ (Prakrit)

tree kuṭhāru 'tree' Rebus: kuṭhāru ‘armourer or weapons maker’(metal-worker)

ram, ibex, markhor 1.ram मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] m (मेष S through H) A male sheep, a ram or tup.(Marathi) meḍ 'iron' (Mundari. Remo.)

goat melh 'goat' Rebus: milakkhu 'copper'

knot (twist) meḍ, ‘knot, Rebus: 'iron’

reed, scarf dhaṭu m. (also dhaṭhu) m. ‘scarf’ (WPah.) (CDIAL 6707) Rebus: dhatu ‘minerals’ (Santali); dhātu ‘mineral’ (Pali) kāṇḍa काण्डः m. stem of a reed. Rebus: kāṇḍa ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’

mountain डोंगर [ ḍōṅgara ] m A hill. डोंगरकणगर or डोंगरकंगर [ ḍōṅgarakaṇagara or ḍōṅgarakaṅgara ] m (डोंगर & कणगर form of redup.) Hill and mountain; hills comprehensively or indefinitely. डोंगरकोळी [ ḍōṅgarakōḷī ] m A caste of hill people or an individual of it. (Marathi) ḍāngā = hill, dry upland (B.); ḍã̄g mountain-ridge (H.)(CDIAL 5476). Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) dhokra 'cire perdue metallurgist'

wing eraka 'wing' eṟaka, ṟekka, rekka, neṟaka, neṟi ‘wing’ (Telugu)(DEDR 2591). Rebus: erako 'moltencast copper'.

snake nāga 'snake' nāga 'lead'

frame of building sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ (M.)(CDIAL 12859) Rebus: sangāṭh संगाठ् । सामग्री m. (sg. dat. sangāṭas संगाटस्), a collection (of implements, tools, materials, for any object), apparatus, furniture, a collection of the things wanted on a journey, luggage (Kashmiri) jangaḍ 'entrustment note' (Gujarati)

monkey kuṭhāru = a monkey (Sanskrit) Rebus: kuṭhāru ‘armourer or weapons maker’(metal-worker), also an inscriber or writer.

kick kolsa 'to kick' Rebus: kol working in iron, blacksmith

foot . khuṭo ʻ leg, foot ʼ Rebus: khũṭ ‘community, guild’ (Santali)

copulation (mating) kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali) Rebus: kampaṭṭa ‘mint, coiner’

adultery ṛanku, ranku = fornication, adultery (Telugu) ranku 'tin'

koṭe meṛed = forged iron, in contrast to dul meṛed, cast iron (Mundari)

meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). dula ‘pair’.

Rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) dul meṛed, cast iron (Mu.) mẽṛhẽt baṭi = iron (Ore) furnaces (Santali).A. bhaṭā ʻ brick -- or lime -- kiln ʼ; B. bhāṭi ʻ kiln ʼ; Or. bhāṭi ʻ brick -- kiln, distilling pot ʼ; Mth. bhaṭhī, bhaṭṭī ʻ brick -- kiln, furnace, still ʼ; Aw.lakh. bhāṭhā ʻ kiln ʼ; H. bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ, bhaṭ f. ʻ kiln, oven, fireplace ʼ; M. bhaṭṭā m. ʻ pot of fire ʼ, bhaṭṭī f. ʻ forge ʼ. -- X bhástrā -- q.v. S.kcch. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ʻ distil (spirits) ʼ.(CDIAL 9656).

Hieroglyph: sãgaḍ f. ʻa body formed of two or more fruits or animals or men &c. linked together' (Marathi). sãghāṛɔ (Gujarati) 'joined animal or animal parts, linked together' Rebus: sangara 'proclamation'.

Hieroglyph: dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'

Hieroglyphs:

1. kolom 'three'

2. Hieroglyph: kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

Hieroglyph: 'human face': mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) Rebus: mũh opening or hole (in a stove for stoking (Bi.); ingot (Santali) mũh metal ingot (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) kaula mengro ‘blacksmith’ (Gypsy) mleccha-mukha (Skt.) = milakkhu ‘copper’ (Pali) The Samskritam gloss mleccha-mukha should literally mean: copper-ingot absorbing the Santali gloss, mũh, as a suffix.

Hieroglyph: करडूं or करडें [karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. Rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy of metal (Marathi) Allograph: करण्ड m. a sort of duck L. కారండవము (p. 0274) [ kāraṇḍavamu ] kāraṇḍavamu. [Skt.] n. A sort of duck. (Telugu) karaṭa1 m. ʻ crow ʼ BhP., °aka -- m. lex. [Cf. karaṭu -- , karkaṭu -- m. ʻ Numidian crane ʼ, karēṭu -- , °ēṭavya -- , °ēḍuka -- m. lex., karaṇḍa2 -- m. ʻ duck ʼ lex: see kāraṇḍava -- ]Pk. karaḍa -- m. ʻ crow ʼ, °ḍā -- f. ʻ a partic. kind of bird ʼ; S. karaṛa -- ḍhī˜gu m. ʻ a very large aquatic bird ʼ; L. karṛā m., °ṛī f. ʻ the common teal ʼ.(CDIAL 2787)

koḍ `horn' (Kuwi) Rebus: koḍ `artisan's workshop' (Gujarati).

कुठारु [p= 289,1] kuṭhāru monkey (Samskritam) Rebus: armourer (Samskritam)

koṭhāri 'crucible' Rebus: koṭhāri 'treasurer' (If the hieroglyph on the leftmost is moon, a possible rebus reading: قمر ḳamar A قمر ḳamar, s.m. (9th) The moon. Sing. and Pl. See سپوږمي or سپوګمي (Pashto) Rebus: kamar 'blacksmith' )

Hieroglyph: arka ‘sun’; agasāle ‘goldsmithy’ (Ka.) erka = ekke (Tbh. of arka) aka (Tbh. of arka) copper (metal); crystal (Ka.lex.) cf. eruvai = copper (Ta.lex.) eraka, er-aka = any metal infusion (Ka.Tu.); erako molten cast (Tulu) Rebus: eraka = copper (Ka.) eruvai = copper (Tamil); ere - a dark-red colour (Ka.)(DEDR 817). eraka, era, er-a = syn. erka, copper, weapons (Kannada)

Hierolyphs:

1. kuDi 'to drink'

2. kuTi 'tree' Rebus: kuThi '

Hieroglyphs:

1. gaṇḍa 'four'

2. కాండము [ kāṇḍamu ] kānḍamu. [Skt.] n. Water. నీళ్లు (Telugu) kaṇṭhá -- : (b) ʻ water -- channel ʼ

3. khaṇḍ 'field,division' (Samskritam) Rebus 1: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Rebus 2: khaṇḍa 'metal implements' lokhãḍ, kāṇḍa ‘flowing water’‘overflowing pot’ Rebus: lokhãḍ, kāṇḍā ‘metalware, tools, pots and pans’(Gujarati)

kole.l 'temple' Rebus: kole.l 'smithy' (Kota)

kāṅga 'comb' Rebus: kanga 'brazier, fireplace' (Kashmiri)

Hieroglyphs:

1. kula '

2. kur.i 'woman'

3. kola ‘tiger’ (Telugu); kola ‘tiger, jackal’ (Kon.). Rebus: kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil) kolhe 'smelter'

mē̃ḍh 'antelope, ram'; rebus: mē̃ḍ 'iron' (Mu.)

క్రమ్మర krammara. adv. క్రమ్మరిల్లు or క్రమరబడు Same as క్రమ్మరు 'look back' (Telugu). Rebus: krəm backʼ(Kho.)(CDIAL 3145) Rebus: kamar 'artisan, smith'

pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild, goldsmith'.

ḍhangar ‘bull’ Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili) ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi)

balad m. ʻox ʼ, gng. bald, (Ku.) barad, id. (Nepali. Tarai) Rebus: bharat (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin)(Punjabi) pattar ‘trough’ Rebus: pattar ‘guild, goldsmith’. Thus, copper-zinc-tin alloy (worker) guild. Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' (Marathi) bhāraṇ = to bring out from a kiln (G.) bāraṇiyo = one whose profession it is to sift ashes or dust in a goldsmith’s workshop (G.lex.) In the Punjab, the mixed alloys were generally called, bharat (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin). In Bengal, an alloy called bharan or toul was created by adding some brass or zinc into pure bronze. bharata = casting metals in moulds; bharavum = to fill in; to put in; to pour into (G.lex.) Bengali. ভরন [ bharana ] n an inferior metal obtained from an alloy of coper, zinc and tin. baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

Hieroglyph: ‘hoof’: Kumaon. khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ, °ṭī ʻgoat's legʼ; Nepalese. khuṭo ʻleg, footʼ(CDIAL 3894). S. khuṛī f. ʻheelʼ; WPah. paṅ. khūṛ ʻfootʼ. (CDIAL 3906). Rebus: khũṭ ‘community, guild’ (Santali)

Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Malt. kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali) kāṇḍa ’stone ore’. kāṇḍa 'tools, pots and pans

‘scarf’ hieroglyph: dhaṭu m. (also dhaṭhu) m. ‘scarf’ (Wpah.) (CDIAL 6707) Rebus: dhatu ‘minerals’ (Santali)

Seated person seated on a stool, with a tiara of a set of curved horns (sometimes with double crown as in al-Sindi 1994: no. 19; Kjærum 1983: no. 185 shown below). A pigtail hangs over the seated person's shoulders. Other hieroglyphs are: drinking through tubes from jar, bull -- sometimes paired, antelope (kid) -- sometimes paired, standard (portable brazier).

kaNDa 'water' rebus: kaNDa 'implements' meDha 'polar star' rebus: meD 'iron' med 'copper' (Slavic)

Dotted circles and three lines on the obverse of many Failaka/Dilmun seals are read rebus as hieroglyphs:

![]() dhAv 'strand' rebus: dhAv 'dhAtu, mineral' tri-dhAtu 'three strands' rebus: 'three minerals'

dhAv 'strand' rebus: dhAv 'dhAtu, mineral' tri-dhAtu 'three strands' rebus: 'three minerals'

A (गोटा) gōṭā Spherical or spheroidal, pebble-form. (Marathi) Rebus 1: khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ (metal) (Marathi) खोट [khōṭa] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge (Marathi). P. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼ (CDIAL 3931) Rebus 2: goTa 'laterite ore'

kolom ‘three’ (Mu.) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

Thus, the seals are intended to serve as metalware catalogs from the smithy/forge. Details of the alloyed metalware are provided by the hieroglyphs of Indus writing on the reverse of the seal.

![]() Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

The rebus reading of hieroglyphs are: తంబుర [tambura] orతంబురా tambura. [Tel. తంతి +బుర్ర .] n. A kind of stringed instrument like the guitar. A tambourine. Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper' tambabica, copper-ore stones; samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari.lex.) tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'.

Thus the seal connotes a merchant of tin and copper.

![]() Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Hieroglyphs on this Dilmun seal are: star, tabernae montana flower, cock, two divided squares, two bulls, antelope, sprout (paddy plant), drinking (straw), stool, twig or tree branch. A person with upraised arm in front of the antelope. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus using lexemes (Meluhha, Mleccha) of Indiansprachbund.

meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)

ṭagara (tagara) fragrant wood (Pkt.Skt.).tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangar ‘bull’; rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi) dula 'pair' (Kashmiri). Rebus: dul 'cast metal' (Santali) Thus, a pair of bulls connote 'cast metal blacksmith'.

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kolmo ‘paddy plant’ (Santali) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali)

Tu. aḍaru twig. Rebus: aduru 'native (unsmelted) metal' (Kannada) Alternative reading: కండె [kaṇḍe] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. Rebus 1: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Rebus 2: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

eraka ‘upraised arm’ (Te.); eraka ‘copper’ (Te.)

Thus, the Dilmun seal is a metalware catalog of damgar 'merchant' dealing with copper and tin.

The two divided squares attached to the straws of two vases in the following seal can also be read as hieroglyphs:

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangā = small country boat, dug-out canoe (Or.); ḍõgā trough, canoe, ladle (H.)(CDIAL 5568). Rebus: ḍānro term of contempt for a blacksmith (N.); ḍangar (H.) (CDIAL 5524)

Thus, a smelting furnace for stone (ore) is connoted by the seal of a blacksmith, ḍangar :

Similar readings are suggested for all hieroglyphs on Failaka seals treating them as evidences of Indus writing in ancient Near East. The suggested rebus readings for specific hieroglyphs of Failaka seals (akin to Dilmun seal readings) are listed in the following section.

Note: What is shown like the phase of a moon may not denote a moon but the shape of a bun-ingot. ḍabu ‘an iron spoon’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’. Alternative reading: mū̃h 'ingot'. Read together with the polar star, the rebus reading is: meḍ mū̃h 'iron ingot'. [meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)] The antelope + divided square is read rebus: eraka tagara kaṇḍ 'tin furnace' (merchant, damgar). The upraised arm indicates eraka 'copper': eraka ‘upraised arm’ (Telugu); eraka ‘copper’ (Telugu) Thus, the seal denotes a merchant dealing in iron, tin and copper ingots.

Rebus readings of hieroglyphs on Failaka seals (akin to Dilmun seal readings):

తంబుర [tambura] orతంబురా tambura. [Tel. తంతి +బుర్ర .] n. A kind of stringed instrument like the guitar. A tambourine. Rebus: tam(b)ra 'copper' tambabica, copper-ore stones; samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari.lex.)

Skt. kuṭī- intoxicating liquor. Ta. kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale; n. drinking, beverage (DEDR 1654). Rebus: kuṭhi‘smelting furnace’.

meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.) Allograph: meḍh ‘ram’.

mūxā ‘frog’. Rebus: mũh ‘(copper) ingot’ (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end (Santali) Allographs: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) मोख [ mōkha ] . Add:--3 Sprout or shoot. (Marathi) Kuwi (Su.) mṛogla shoot of bamboo; (P.) moko sprout (DEDR 4997) Tu. mugiyuni to close, contract, shut up; muguru sprout, shoot, bud; tender, delicate; muguruni, mukuruni to bud, sprout; muggè, moggè flower-bud, germ; (BRR; Bhattacharya, non-brahmin informant) mukkè bud. Kor. (O.) mūke flower-bud. (DEDR 4893)

ḍato ‘claws or pincers (chelae) of crabs’; ḍaṭom, ḍiṭom to seize with the claws or pincers, as crabs, scorpions; ḍaṭkop = to pinch, nip (only of crabs) (Santali) Rebus: dhātu ‘mineral’ (Vedic); dhatu ‘a mineral, metal’ (Santali)

![]() Designs of stamp seals from Al-Khidr are composed of characteristic Early Dilmun stamp seal motifs. This stamp seal depicts human and half-human-half-animal horned figures, monkeys, serpents and birds on either side of a central motif of a standard and a podium at the bottom (drawing of stamp seal impression).

Designs of stamp seals from Al-Khidr are composed of characteristic Early Dilmun stamp seal motifs. This stamp seal depicts human and half-human-half-animal horned figures, monkeys, serpents and birds on either side of a central motif of a standard and a podium at the bottom (drawing of stamp seal impression).![]() On the obverse of Dilmun seals from Al-Khidr are depicted human or divine figures, half human-half animal creatures, animal figures (such as gazelles, bulls, scorpions, and snakes), celestial bodies (star or sun and moon), sometimes drinking scenes and also other activities (playing musical instruments). Composition of these motifs varies from formal (with ordering the figures and symbols to clear scenes) to chaotic.

On the obverse of Dilmun seals from Al-Khidr are depicted human or divine figures, half human-half animal creatures, animal figures (such as gazelles, bulls, scorpions, and snakes), celestial bodies (star or sun and moon), sometimes drinking scenes and also other activities (playing musical instruments). Composition of these motifs varies from formal (with ordering the figures and symbols to clear scenes) to chaotic.

![]() koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer, warehouse' . मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda) dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' meD 'body' rebus:meD 'iron' Dhangar 'bull' rebus: Dhangar 'blacksmith'

koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer, warehouse' . मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda) dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' meD 'body' rebus:meD 'iron' Dhangar 'bull' rebus: Dhangar 'blacksmith'

![]()

![]() Seals with rotating designs usually bear pure plant, animal or geometric motifs. karaDi 'safflower' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' (Marathi) kaNDa 'divisions' rebus: kaNDa 'implements'.

Seals with rotating designs usually bear pure plant, animal or geometric motifs. karaDi 'safflower' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' (Marathi) kaNDa 'divisions' rebus: kaNDa 'implements'.

dhAv 'strand' rebus: dhAv 'dhAtu, mineral' tri-dhAtu 'three strands' rebus: 'three minerals'

dhAv 'strand' rebus: dhAv 'dhAtu, mineral' tri-dhAtu 'three strands' rebus: 'three minerals'A (गोटा) gōṭā Spherical or spheroidal, pebble-form. (Marathi) Rebus 1: khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ (metal) (Marathi) खोट [khōṭa] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge (Marathi). P. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼ (CDIAL 3931) Rebus 2: goTa 'laterite ore'

kolom ‘three’ (Mu.) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

Thus, the seals are intended to serve as metalware catalogs from the smithy/forge. Details of the alloyed metalware are provided by the hieroglyphs of Indus writing on the reverse of the seal.

Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.

Composition of two horned animals, sitting human playing a four-string musical instrument, a star and a moon.The rebus reading of hieroglyphs are: తంబుర [tambura] or

Thus the seal connotes a merchant of tin and copper.

Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]

Inventory No. 8480. A seal from Dilmun, A seal from Dilmun, made of soft stone, classified as the 3rd largest seal in Failaka Island, decorated with human and zoomorphic figures. 0.16 X 4.8 cm. Site: the Ruler's Palace. 2nd millennium BCE, Dilmun civilization [NOTE: Many such seals of Failaka and Dilmun have been read rebus as Indus writing on blogposts.]Hieroglyphs on this Dilmun seal are: star, tabernae montana flower, cock, two divided squares, two bulls, antelope, sprout (paddy plant), drinking (straw), stool, twig or tree branch. A person with upraised arm in front of the antelope. All these hieroglyphs are read rebus using lexemes (Meluhha, Mleccha) of Indiansprachbund.

meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)

ṭagara (tagara) fragrant wood (Pkt.Skt.).tagara 'antelope'. Rebus 1: tagara 'tin' (ore) tagromi 'tin, metal alloy' (Kuwi) Rebus 2: damgar 'merchant'

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangar ‘bull’; rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi) dula 'pair' (Kashmiri). Rebus: dul 'cast metal' (Santali) Thus, a pair of bulls connote 'cast metal blacksmith'.

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kolmo ‘paddy plant’ (Santali) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali)

Tu. aḍaru twig. Rebus: aduru 'native (unsmelted) metal' (Kannada) Alternative reading: కండె [kaṇḍe] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. Rebus 1: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Rebus 2: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

eraka ‘upraised arm’ (Te.); eraka ‘copper’ (Te.)

Thus, the Dilmun seal is a metalware catalog of damgar 'merchant' dealing with copper and tin.

The two divided squares attached to the straws of two vases in the following seal can also be read as hieroglyphs:

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus 1: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (ore). Rebus 2: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar' (Santali) Thus, the two divided squares connote furnace for stone (ore).

kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelting furnace’ (Santali)

ḍangā = small country boat, dug-out canoe (Or.); ḍõgā trough, canoe, ladle (H.)(CDIAL 5568). Rebus: ḍānro term of contempt for a blacksmith (N.); ḍangar (H.) (CDIAL 5524)

Thus, a smelting furnace for stone (ore) is connoted by the seal of a blacksmith, ḍangar :

Stamp seal with a boat scene. Steatite. L. 2 cm. Gulf regio, Failaka, F6 758. Early Dilmun, ca. 2000-1800 BCE. Ntional Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum, 1129 ADY. The subject is a nude male figure standing in the middle of a flat-bottomed boat, facing right. The man's arms are bent at the elbow, perpendicular to his torso. Beside him are two jars stand on the deck of the boat, each containing a long pole to which is attached a hatched square that perhaps represents a banner. Six square stamp seals from Failaka have been published...It is unlikely that the hatched squares represent sails, since the poles to which they are attached emerge from vases. The two diagonal lines on the body of the boat may represent the reed bundles from which these craft were buit. See Kjærum 1983, seal nos. 192, 234, 254, 266, 335, 367. Source: Source: Joan Aruz et al., 2003, Art of the First cities: the third millennium BCE from the Mediterranean to the Indus, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art (Pages 320, 322).See also: http://ancientworldonline.blogspot.in/2012/10/kuwaiti-slovak-archaeological-mission.html

Similar readings are suggested for all hieroglyphs on Failaka seals treating them as evidences of Indus writing in ancient Near East. The suggested rebus readings for specific hieroglyphs of Failaka seals (akin to Dilmun seal readings) are listed in the following section.

Note: What is shown like the phase of a moon may not denote a moon but the shape of a bun-ingot. ḍabu ‘an iron spoon’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’. Alternative reading: mū̃h 'ingot'. Read together with the polar star, the rebus reading is: meḍ mū̃h 'iron ingot'. [meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.)] The antelope + divided square is read rebus: eraka tagara kaṇḍ 'tin furnace' (merchant, damgar). The upraised arm indicates eraka 'copper': eraka ‘upraised arm’ (Telugu); eraka ‘copper’ (Telugu) Thus, the seal denotes a merchant dealing in iron, tin and copper ingots.

Rebus readings of hieroglyphs on Failaka seals (akin to Dilmun seal readings):

తంబుర [tambura] or

kolmo ‘paddy plant’ (Santali); kolom = cutting, graft; to graft, engraft, prune; kolma hoṛo = a variety of the paddy plant (Desi)(Santali.) kolom ‘three’ (Mu.) Rebus: kolami ‘furnace, smithy’ (Telugu)

khaṇḍ ‘field, division’ (Skt.) Rebus: Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ, (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone (DEDR 1298). खडा (Marathi) is ‘metal, nodule, stone, lump’. kaṇi ‘stone’ (Kannada) with Tadbhava khaḍu. khaḍu, kaṇ ‘stone/nodule (metal)’. Rebus: khaṇḍaran, khaṇḍrun ‘pit furnace’ (Santali) kaṇḍ ‘furnace’ (Skt.) लोहकारकन्दुः f. a blacksmith's smelting furnace (Grierson Kashmiri lex.) [khaṇḍa] A piece, bit, fragment, portion.(Marathi) Rebus: khānḍa ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

Allographs: Kur. kaṇḍō a stool. Malt. kanḍo stool, seat. (DEDR 1179) खंड [ khaṇḍa ] A piece, bit, fragment, portion.(Marathi) khaṇḍ ‘ivory’ (H.) jaṇḍ khaṇḍ = ivory (Jaṭkī) khaṇḍ ī = ivory in rough (Jaṭkī) kandhi = a lump, a piece (Santali.lex.) kandi (pl. -l) beads, necklace (Pa.); kanti (pl. -l) bead, (pl.) necklace; kandit. bead (Ga.)(DEDR 1215).

Ta. kaṇ eye, aperture, orifice, star of a peacock's tail. (DEDR 1159a) Rebus ‘brazier, bell-metal worker’: கன்னான் kaṉṉāṉ , n. < கன்¹. [M. kannān.] Brazier, bell-metal worker, one of the divisions of the Kammāḷa caste; செம்புகொட்டி. (திவா.) కండె [ kaṇḍe ] kaṇḍe. [Tel.] n. A head or ear of millet or maize. జొన్నకంకి (Telugu) kã̄ṛ ʻstack of stalks of large milletʼ(Maithili) kã̄ḍ 2 काँड् m. a section, part in general; a cluster, bundle, multitude (Śiv. 32). kã̄ḍ 1 काँड् । काण्डः m. the stalk or stem of a reed, grass, or the like, straw. In the compound with dan 5 (p. 221a, l. 13) the word is spelt kāḍ.

Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330).

Ka. (Hav.) aḍaru twig; (Bark.) aḍïrï small and thin branch of a tree; (Gowda) aḍəri small branches. Tu. aḍaru twig.(DEDR 67) Rebus: aduru gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330).

satthiya ‘svastika glyph’; rebus: satthiya ‘pewter’.

Skt. kuṭī- intoxicating liquor. (DEDR 1654) Ta. kuṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to drink, inhale; n. drinking, beverage,drunkenness; kuṭiyaṉ drunkard. Rebus: kuṭi= smelter furnace (Santali)

gaṇḍ 'four'. kaṇḍ 'bit'. Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar'. kolmo 'three'. Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

tagara 'antelope'; rebus 1: tagara 'tin'; rebus 2: tamkāru, damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian)

The bamboo-shoot is tã̄bā read rebus: tamba 'copper'.

tagara 'antelope'; rebus 1: tagara 'tin'; rebus 2: tamkāru, damgar 'merchant' (Akkadian)

The bamboo-shoot is tã̄bā read rebus: tamba 'copper'.

B. Or. bichā 'scorpion', Mth. bīch (CDIAL 12081) Rebus: meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Mu.lex.)

kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali) Rebus:kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire altar, consecrated fire’.

mūxā ‘frog’. Rebus: mũh ‘(copper) ingot’ (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end (Santali) Allographs: mũhe ‘face’ (Santali) मोख [ mōkha ] . Add:--3 Sprout or shoot. (Marathi) Kuwi (Su.) mṛogla shoot of bamboo; (P.) moko sprout (DEDR 4997) Tu. mugiyuni to close, contract, shut up; muguru sprout, shoot, bud; tender, delicate; muguruni, mukuruni to bud, sprout; muggè, moggè flower-bud, germ; (BRR; Bhattacharya, non-brahmin informant) mukkè bud. Kor. (O.) mūke flower-bud. (DEDR 4893)

pajhar. = to sprout from a root (Santali) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

ḍangar ‘bull’; rebus: ḍangar ‘blacksmith’ (Hindi)

ḍumgara ‘mountain’ (Pkt.)(CDIAL 5423). Rebus: damgar ‘merchant’.

kangha (IL 1333) kãgherā comb-maker (H.) Rebus: kangar ‘portable furnace’

kangha (IL 1333) kãgherā comb-maker (H.) Rebus: kangar ‘portable furnace’