https://tinyurl.com/yd85bsck

This is an addendum to

I. tihāsa. Navanidhi of Kubera identified in Indus Script Corpora as wealth-accounting ledgrers, metalwork catalogues https://tinyurl.com/ya2c9kmm

2. Venerated Trefoil. Mohenjo-daro and Bactrian priests wear तार्प्य Sky Garment of Varuṇa Indus Script signifiers of dhā̆vaḍ potr̥, 'smelter, purifier priest' https://tinyurl.com/ycpghhse

![]()

![]()

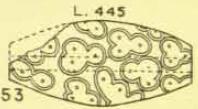

Trefoil Decorated bead. Pl. CXLVI, 53 (Marshall, opcit.)

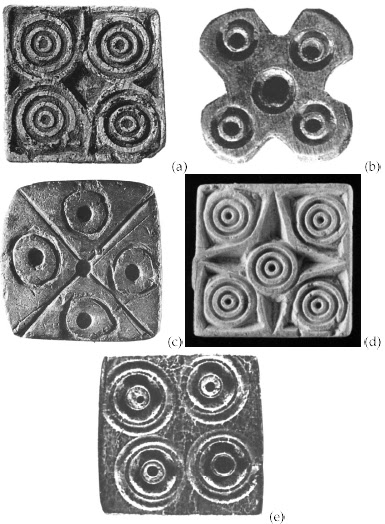

Hieroglyph-multiplex of dotted circles as 'beads': kandi 'bead' Rebus: kanda 'fire-altar' khaNDa 'metal implements'

![]() Trefoils painted on steatite beads, Harappa (After Vats, Pl. CXXXIII, Fig.2)

Trefoils painted on steatite beads, Harappa (After Vats, Pl. CXXXIII, Fig.2)![]() Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit Harappa.com

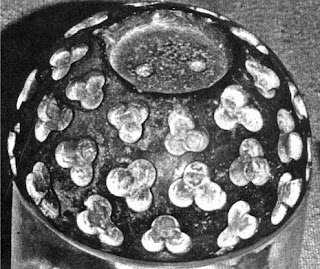

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit Harappa.com![]() Trefoil inlay decorated on a bull calf. Uruk (W.16017) ca. 3000 BCE. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge),

Trefoil inlay decorated on a bull calf. Uruk (W.16017) ca. 3000 BCE. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge),

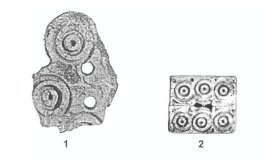

![]() Artifacts from Jiroft.

Artifacts from Jiroft.

![]()

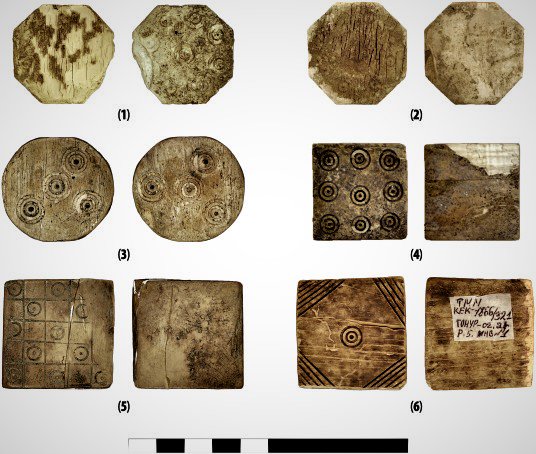

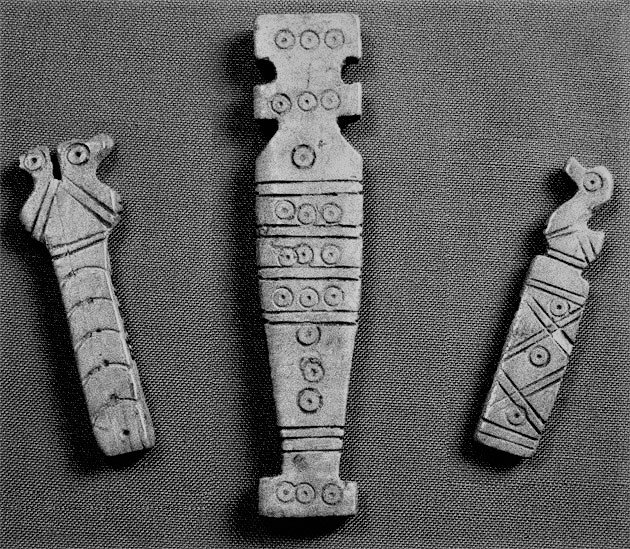

Ivory combs. Turkmenistan.

![]()

![]()

Ivory objects. Sarasvati Civilization

![]()

![]()

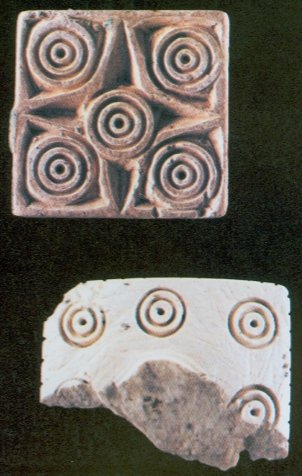

Tablets.Ivory objects. Mohenjo-daro.

![]()

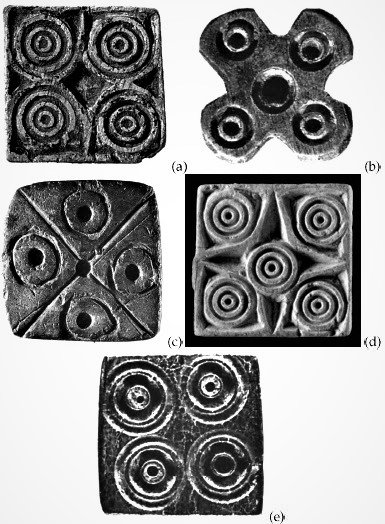

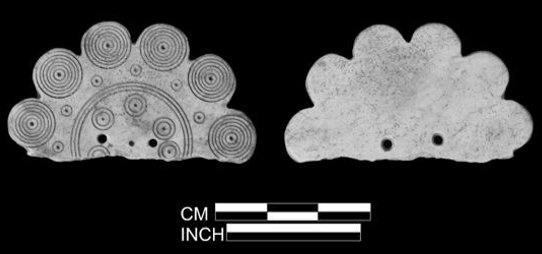

Button seal. Baror, Rajasthan.

Courtesy: manasataramgini @blog_supplement

![]()

![]()

![]() The + glyph of Sibri evidence is comparable to the large-sized 'dot', dotted circles and + glyph shown on this Mohenjo-daro seal m0352 with dotted circles repeated on 5 sides A to F. Mohenjo-daro Seal m0352 shows dotted circles in the four corners of a fire-altar and at the centre of the altar together with four raised 'bun' ingot-type rounded features. Rebus readings of m0352 hieroglyphs:

The + glyph of Sibri evidence is comparable to the large-sized 'dot', dotted circles and + glyph shown on this Mohenjo-daro seal m0352 with dotted circles repeated on 5 sides A to F. Mohenjo-daro Seal m0352 shows dotted circles in the four corners of a fire-altar and at the centre of the altar together with four raised 'bun' ingot-type rounded features. Rebus readings of m0352 hieroglyphs:

![]()

वट [p= 914,3] m. (perhaps Prakrit for वृत , " surrounded , covered " ; cf. न्यग्-रोध) the Banyan or Indian fig. tree (Ficus Indica) MBh.Ka1v. &c RTL. 337 (also said to be n.); a pawn (in chess) L. (Monier-Williams) Ta. vaṭam cable, large rope, cord, bowstring, strands of a garland, chains of a necklace; vaṭi rope; vaṭṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to tie. Ma. vaṭam rope, a rope of cowhide (in plough), dancing rope, thick rope for dragging timber. Ka. vaṭa, vaṭara, vaṭi string, rope, tie. Te. vaṭi rope, cord. Go. (Mu.) vaṭiya strong rope made of paddy straw (Voc. 3150). Cf. 3184 Ta. tār̤vaṭam. / Cf. Skt. vaṭa- string, rope, tie; vaṭāraka-, vaṭākara-, varāṭaka- cord,string; Turner, CDIAL, no. 11212. (CDIAL 5220)vaṭa2 ʻ string ʼ lex. [Prob. ← Drav. Tam. vaṭam, Kan. vaṭi, vaṭara, &c. DED 4268] N. bariyo ʻ cord, rope ʼ; Bi. barah ʻ rope working irrigation lever ʼ, barhā ʻ thick well -- rope ʼ, Mth. barahā ʻ rope ʼ. (CDIAL 11212).

See: https://tinyurl.com/y85goask Wealth of a nation...

Trefoil decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. Steatite statue fragment. Mohenjo-daro (Sd 767). After Ardeleanu-Jansen, 1989: 196, fig. 1; cf. Parpola, 1994, p. 213. Trefoils painted on steatite beads. Harappa (After Vats. Pl. CXXXIII, Fig. 2) Trefoil on the shawl of the priest. Mohenjodaro. The discovery of the King Priest acclaimed by Sir John Marshall as “the finest piece of statuary that has been found at Moenjodaro….draped in an elaborate shawl with corded or rolled over edge, worn over the left shoulder and under the right arm. This shawl is decorated all over with a design of trefoils in relief interspersed occasionally with small circles, the interiors of which are filled with a red pigment “. Gold fillet with ‘standard device’ hieroglyph. Glyph ‘hole’: pottar, பொத்தல் pottal, n. < id. [Ka.poṭṭare, Ma. pottu, Tu.potre.] trika, a group of three (Skt.) The occurrence of a three-fold depiction on a trefoil may thus be a phonetic determinant, a suffix to potṛ as in potṛka.

![Image result for Steatite statue fragment. Mohenjo-daro (Sd 767). After Ardeleanu-Jansen, 1989: 196, fig. 1; cf. Parpola, 1994, p. 213. Trefoils painted on steatite beads. Harappa (After Vats. Pl. CXXXIII, Fig. 2)]() Steatite statue fragment; Mohenjodaro (Sd 767); trefoil-decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. After Ardeleanu-Jansen 1989: 196, fig. 1; Parpola, 1994, p. 213.

Steatite statue fragment; Mohenjodaro (Sd 767); trefoil-decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. After Ardeleanu-Jansen 1989: 196, fig. 1; Parpola, 1994, p. 213.

![]() Detail of terracotta bangle with red and white trefoil on a green background H98-3516/8667-01 from Trench 43).

Detail of terracotta bangle with red and white trefoil on a green background H98-3516/8667-01 from Trench 43).

![]() miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda)

miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda)

தட்டார்பாட்டம் taṭṭār-pāṭṭam

3878 Ta. paṭṭai flatness; paṭṭam flat or level surface of anything, flat piece (as of bamboo). Ko. paṭ flatness (of piece of iron, of head); paṭm (obl.paṭt-) ground for house. To. poṭ site of dairy or house. ? Koḍ. paṭṭi space before house, spreading space; maṇa-paṭṭi sandbank. Nk. paṛ place. Pa.paḍ place, site. Pe. paṭ kapṛa top of the head. Manḍ. paṭ kapṛa id. Malt. paṭa numeral classifier of flat objects.

3865 Ta. paṭṭaṭai, paṭṭaṟai anvil, smithy, forge. Ka. paṭṭaḍe, paṭṭaḍi anvil, workshop. Te. paṭṭika, paṭṭeḍa anvil; paṭṭaḍa workshop

3866 Ta. paṭṭaṭai neck-ornament (< Te.). Tu. paṭṭaḍi a kind of necklace. Te. paṭṭeḍa a sort of ornament worn by women round the neck.

![Image result for gold fillet mohenjodaro]()

![]()

http://www.harappa.com/indus/43.html Seated male sculpture, or "Priest King" from Mohenjo-daro (41, 42, 43). Fillet or ribbon headband with circular inlay ornament on the forehead and similar but smaller ornament on the right upper arm. The two ends of the fillet fall along the back and though the hair is carefully combed towards the back of the head, no bun is present. The flat back of the head may have held a separately carved bun as is traditional on the other seated figures, or it could have held a more elaborate horn and plumed headdress.

Two holes beneath the highly stylized ears suggest that a necklace or other head ornament was attached to the sculpture. The left shoulder is covered with a cloak decorated with trefoil, double circle and single circle designs that were originally filled with red pigment. Drill holes in the center of each circle indicate they were made with a specialized drill and then touched up with a chisel. Eyes are deeply incised and may have held inlay. The upper lip is shaved and a short combed beard frames the face. The large crack in the face is the result of weathering or it may be due to original firing of this object.

Material: white, low fired steatite

Dimensions: 17.5 cm height, 11 cm width

Mohenjo-daro, DK 1909

National Museum, Karachi, 50.852

Marshall 1931: 356-7, pl. XCVIII

![terracotta-dice-ashmolean-museum]()

![]()

![Image result for dice mohenjodaro one]() Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)

Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)

![]() dāya 'dotted circle, role of dice of one is the centre-piece of the early Gandhara punchmarked silver coin with a six-armed wheel, a vajra, thunderbolt metallic weapon, ca. 6th century BCE. The dot in the circle signifies silver. The punchmarked coin is made of silver. The circle is vaṭa. Together, with dāya, the single dot within circle, the hypertext signifier is dhāvḍī ʻdhāvaḍ 'smelting, smelter' - a key metallurgical repertoire of the Gandhara mint which issued the punchmarked coin, the paharaṇa mudrā 'struck' coins .

dāya 'dotted circle, role of dice of one is the centre-piece of the early Gandhara punchmarked silver coin with a six-armed wheel, a vajra, thunderbolt metallic weapon, ca. 6th century BCE. The dot in the circle signifies silver. The punchmarked coin is made of silver. The circle is vaṭa. Together, with dāya, the single dot within circle, the hypertext signifier is dhāvḍī ʻdhāvaḍ 'smelting, smelter' - a key metallurgical repertoire of the Gandhara mint which issued the punchmarked coin, the paharaṇa mudrā 'struck' coins .

ஏர்த்தாயம் ēr-t-tāyam , n. < id. +. Ploughing in season; பருவகாலத்துழவு. (W .)காணித்தாயவழக்கு kāṇi-t-tāya-vaḻakku, n. < id. +. Dispute between coparceners about hereditary land; பங்காளிகளின் நிலவழக்கு. (J .)தர்மதாயம் tarma-tāyam , n. < id. + dāya. Charitable inams; தருமத்துக்கு விடப்பட்ட மானியம். (G. S m. D. I , ii, 55.)தாயம் tāyam

, n. < dāyabhāga. 1. Division of an estate among heirs; ஞாதிகள் தம்முள் பிரித்துக்கொள்ளும் உரிமைப்பங்கு. 2. A treatise on the Hindu law of inheritance by Jīmūtavākaṉa; பாகப்பிரிவினையைப்பற்றி ஜீமூத வாகனர் இயற்றிய நூல். 3. Chapter on the law of inheritance in the Mitākṣara of Vijñāṉēšvara, 12th c. (R. F .); பன்னிரண்டாம் நூற்றாண்டில் விஞ் ஞானேசுரர் இயற்றிய மிதாக்ஷரத்தில் தாயவுரிமை யைப்பற்றிக் கூறும் பகுதி.தாயம் tāyam , n. < dāya. 1. Patrimony, inheritance, wealth of an ancestor capable of inheritance and partition (R. F .); பாகத்திற்குரிய பிதிரார்ச்சிதப்பொருள். 2. Share; பங்கு. (யாழ். அக.) 3. Paternal relationship; தந்தைவழிச் சுற்றம். (யாழ். அக.) 4. A fall of the dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் விருத்தம். முற்பட இடுகின்ற தாயம் (கலித். 136, உரை). 5. Cubical pieces in dice-play; கவறு. (யாழ். அக.) 6. Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. 7. Gift, donation; கொடை. (யாழ். அக.) 8. Good opportunity; சமயவாய்ப்பு. (யாழ். அக.) 9. Affliction, distress; துன்பம். (யாழ். அக.) 10. Delay, stop; தாக்காட்டு. (W .) 11. A child's game played with seeds or shells on the ground; குழந்தை விளையாட்டுவகை. 12. Excellence, superiority; மேன்மை. தாயமாம் பதுமினிக்கு (கொக்கோ. 1, 28).

![Ageless traditional ajrak print from Kutch, Gujarat]()

![Traditional ajrak print from Barmer, Rajasthan that is still prominent today]()

![The trefoil motif on an ajrak printed shawl]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

nīˊla ʻ dark blue, dark green, black ʼ RV., nīlaka -- lex. 2. nīˊla -- n. ʻ blue substance ʼ ŚBr., ʻ indigo ʼ Yājñ.

1. Pa. nīla -- , ˚aka -- ʻ dark blue, blue -- green ʼ; Pk. ṇīla<-> ʻ blue, green ʼ, Gy. pal. nīˊlă; Ḍ. nīla ʻ blue, dark green ʼ; Ash. nīˊlestə ʻ green, blue ʼ; Wg. nyīlə, nīrə ʻ blue ʼ, Kt. nīlə, ninyílë, Pr. nīl, nyīˊli, Dm. nīla; Tir. nīlə ʻ green blue ʼ; Paš. nil ʻ dark blue ʼ; Shum. nīl ʻ blue ʼ, Gaw. nīˊla, Kal.urt. nīˊl*l , Bshk. (Biddulph) nül, f. nīl, Tor. nīˊlə; Phal. nīˊlo ʻ green, blue ʼ, Sh. nīlṷ, K. nyūlu , dat. nīlis; S. nīro ʻ blue ʼ, L. nīlā, P. nīlā, līlā; WPah.bhal. nīl m. ʻ wild cock ʼ, nīlo ʻ blue, green ʼ, jaun. līlo ʻ blue ʼ; Ku. nīl m. ʻ a bruise ʼ; N. niloʻ blue ʼ, A. nil, B. nila, Or. niḷa; Mth. nīl ʻ dark blue, black ʼ; H. nīlā, līl(ā) ʻ blue ʼ, G. nīḷũ, nīlũ, līlũ, M. nīḷ, niḷā; Si. nil ʻ green, blue ʼ; Md. nū, nulē ʻ blue ʼ. -- X *lōhila -- q.v.2. S. nīru m. ʻ blue colour, indigo ʼ; L. nīl m. ʻ indigo ʼ, P. nīl, līl m., Or. nīḷā, (Sambhalpur) nirā.*nīliya -- , nīlī -- , *nailiya -- ; ānīla -- ; *nīlakāra -- , nīlamaṇi -- , nīlavarṇa -- , nīlōtpala -- ; indranīla -- .

Addenda: nīˊla -- . 1. S.kcch. nīlo ʻ green ʼ; Md. nū ʻ blue ʼ, nulē ʻ is blue ʼ.2. nīˊla -- n.: WPah.poet. nīḷ m. ʻ indigo ʼ, J. nīḷ m. ʻ inner part of the blue or other pine ʼ.(CDIAL 7563)*nīlakāra ʻ dyer ʼ. [nīˊla -- , kāra -- 1 ]L. nirālī m. ʻ indigo dyer ʼ, awāṇ lilārī m. ʻ dyer ʼ, P. lilārī, lal˚ m., H. lilārī m. (CDIAL 7564)![Image may contain: one or more people]() "A bust of a priest-king excavated at Mohenjo-daro, currently in theNational Museum of Pakistan, shows him draped over one shoulder in a piece of cloth that resembles an ajrak. Of special note are the trefoilpattern etched on the person's garment interspersed with small circles, the interiors of which were filled with a red pigment...Ajraks are made all over Sindh, especially in Matiari, Hala, Bhit Shah, Moro, Sukkur, Kandyaro, Hyderabad, and many cities of Upper Sindh and Lower Sindh."

"A bust of a priest-king excavated at Mohenjo-daro, currently in theNational Museum of Pakistan, shows him draped over one shoulder in a piece of cloth that resembles an ajrak. Of special note are the trefoilpattern etched on the person's garment interspersed with small circles, the interiors of which were filled with a red pigment...Ajraks are made all over Sindh, especially in Matiari, Hala, Bhit Shah, Moro, Sukkur, Kandyaro, Hyderabad, and many cities of Upper Sindh and Lower Sindh."

Etymology of the Word Ajrak

History of Ajrak

Tracing the Origins

The International Fancy for the Intricate Ajrak

Status of Ajrak Industry in Pakistan

Etymology of the Word Ajrak

History of Ajrak

Tracing the Origins

The International Fancy for the Intricate Ajrak

Status of Ajrak Industry in Pakistan

Etymology of the Word Ajrak

History of Ajrak

Tracing the Origins

The International Fancy for the Intricate Ajrak

Status of Ajrak Industry in Pakistan

![http://www.houseofpakistan.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/09/history-of-ajrak.jpg]()

Ajrak: The Sacred Cloth of Sindh BY SAHAPEDIA AUGUST 26, 2017

This is an addendum to

I. tihāsa. Navanidhi of Kubera identified in Indus Script Corpora as wealth-accounting ledgrers, metalwork catalogues https://tinyurl.com/ya2c9kmm

2. Venerated Trefoil. Mohenjo-daro and Bactrian priests wear तार्प्य Sky Garment of Varuṇa Indus Script signifiers of dhā̆vaḍ potr̥, 'smelter, purifier priest' https://tinyurl.com/ycpghhse

Is the trefoil motif created by embroidery process or Ajrak block printing process on cotton textiles?

Trefoil on the shawl of Mohenjo-daro priest is made of cotton. It could be an ajrak. The motif is kakar 'cloud'. One elaboration of the metaphor of trefoil is that it signifies thefusion of three sun-disks of the sungod, water god and earth god.

Ajrak is a shawl of the dimensions of 2.5 ft. width and 3 metres length. It appers that the priests of Sarasvati Civilization wore this shawl as a one-piece cloth covering their body across the left shoulder leaving the right shoulder bare. This shawl-wearing is comparable to many sculptures which depict the Sarasvati Civilization priests wearing a similar garment.

It should be noted that the motif on the shawl of Mohenjo-daro priest has one dot two dots joined and three dots joined. The fillet he wears on his forehead and right shoulder is also a dotted circle.This dotted circle is read rebus: dhavad 'smelter'.The cloth is potti 'cloth' rebus: Potr̥ 'purifier priest' of R̥gveda.

Harappan male ornament styles. After Fig.6.7 in Kenoyer, JM, 1991, Ornament styles of the Indus valley tradition: evidence from recent excavations at Harappa, Pakistan in: Paleorient, vol. 17/2 -1991, p.93 Source: Marshall, 1931: Pl. CXVIII

http://a.harappa.com/sites/g/files/g65461/f/Kenoyer1992_Ornament%20Styles%20of%20the%20Indus%20Valley%20Tradition%20Ev.pdf

http://a.harappa.com/sites/g/files/g65461/f/Kenoyer1992_Ornament%20Styles%20of%20the%20Indus%20Valley%20Tradition%20Ev.pdf

https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/styles/galleryformatter_slide/public/priest-king-painted-3.jpg?itok=z4uEk1Yq

![Image result for ajrak mohenjodaro priest]()

Clearly, the wearing a fillet on the shoulder and wearing a dress with trefoil hieroglyphs made the figure of some significance to the community.

"Inlaid bead. No. 53 (L445). (See also Pl. CLII,17) Steatite. An exceptionally fine bead. The interiors of the trefoils were probably filled in with either paste or colour. The former is the more probable, for in the base of each foil there is a small pitting that may been used for keying a coloured paste. The depth of the cutting is 0.05 inch. Level, 3 feet below surface. late Period. Found in Chamber 27, Block 4, L Area. The most interesting of these beads are those with the trefoil pattern, which also occurs on the robe worn by the statue pictured in Pl. XCVIII. The trefoils on both the beads and statue are irregular in shape and in this respect differ from the pattern as we ordinarily know it. (For another example of this ornamentation, see the bull illustrated in Jastrow, Civilization of Babylonia and Assyria, pl. liii, and the Sumerian bull from Warka shown in Evans, Palace of Minos, vol. ii, pt. 1, p.261, fig. 156. Sir Arthus Evans has justly compared the trefoil markings on this latter bull with the quatrefoil markings of Minoan 'rytons', and also with the star-crosses on Hathor's cow. Ibid., vol. i, p.513. Again, the same trefoil motif is perhaps represented on a painted sherd from Tchechme-Ali in the environs of Teheran. Mem. Del. en Perse, t.XX, p. 118, fig. 6)."(John Marshall, opcit., p.517)

Clearly, the wearing a fillet on the shoulder and wearing a dress with trefoil hieroglyphs made the figure of some significance to the community.

"Inlaid bead. No. 53 (L445). (See also Pl. CLII,17) Steatite. An exceptionally fine bead. The interiors of the trefoils were probably filled in with either paste or colour. The former is the more probable, for in the base of each foil there is a small pitting that may been used for keying a coloured paste. The depth of the cutting is 0.05 inch. Level, 3 feet below surface. late Period. Found in Chamber 27, Block 4, L Area. The most interesting of these beads are those with the trefoil pattern, which also occurs on the robe worn by the statue pictured in Pl. XCVIII. The trefoils on both the beads and statue are irregular in shape and in this respect differ from the pattern as we ordinarily know it. (For another example of this ornamentation, see the bull illustrated in Jastrow, Civilization of Babylonia and Assyria, pl. liii, and the Sumerian bull from Warka shown in Evans, Palace of Minos, vol. ii, pt. 1, p.261, fig. 156. Sir Arthus Evans has justly compared the trefoil markings on this latter bull with the quatrefoil markings of Minoan 'rytons', and also with the star-crosses on Hathor's cow. Ibid., vol. i, p.513. Again, the same trefoil motif is perhaps represented on a painted sherd from Tchechme-Ali in the environs of Teheran. Mem. Del. en Perse, t.XX, p. 118, fig. 6)."(John Marshall, opcit., p.517)

Trefoil Decorated bead. Pl. CXLVI, 53 (Marshall, opcit.)

Hieroglyph-multiplex of dotted circles as 'beads': kandi 'bead' Rebus: kanda 'fire-altar' khaNDa 'metal implements'

Trefoil Hieroglyph-multiplex as three dotted circles: kolom 'three' Rebus: kole.l kanda 'temple fire-altar'

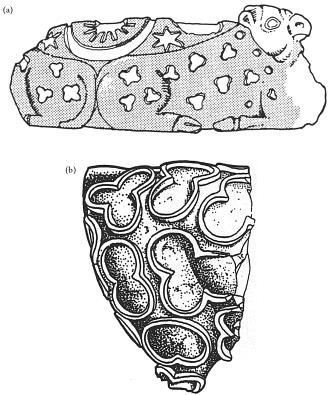

(After Fig. 18.10 Parpola, 2015, p. 232) (a) Neo-Sumerian steatite bowl from Ur (U.239), bearing symbols of the sun, the moon (crucible), stars and trefoils (b) Fragmentary steatite statuette from Mohenjo-daro. After Ardeleanu-Jansen 1989-205, fig. 19 and 196, fig. 1

A finely polished pedestal. Dark red stone. Trefoils. (DK 4480, cf. Mackay 1938: I, 412 and II, pl. 107.35). National Museum, Karachi.

Hieroglyph: kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy'; kolle

'blacksmith'; kole.l 'smithy, temple' (Kota)

Trefoils painted on steatite beads, Harappa (After Vats, Pl. CXXXIII, Fig.2)

Trefoils painted on steatite beads, Harappa (After Vats, Pl. CXXXIII, Fig.2) Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit Harappa.com

Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period, dating after 1900 BC. Credit Harappa.comHieroglyph markhor, ram: mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4, miṇḍha -- 2, °aka -- , mēṭha -- 2, mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2, °aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ]1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb. amŕn/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*ll ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m.,°ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., °ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, °ḍā m., °ḍhi f., H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M.mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.A. also mer (phonet. mer) ʻ ram ʼ (CDIAL 10310). Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.)damkom = a bull calf (Santali) Rebus: damha = a fireplace; dumhe = to heap, to collect together (Santali)

https://tinyurl.com/y8fed8xd

Meluhha artisans, Indus script writers draw circles with small radii to signify dhātu, dhāv 'mineral' hypertexts

वृत्त [p= 1009,2] mfn. turned , set in motion (as a wheel) RV.; a circle; vr̥ttá ʻ turned ʼ RV., ʻ rounded ʼ ŚBr. 2. ʻ completed ʼ MaitrUp., ʻ passed, elapsed (of time) ʼ KauṣUp. 3. n. ʻ conduct, matter ʼ ŚBr., ʻ livelihood ʼ Hariv. [√vr̥t 1 ] 1. Pa. vaṭṭa -- ʻ round ʼ, n. ʻ circle ʼ; Pk. vaṭṭa -- , vatta -- , vitta -- , vutta -- ʻ round ʼ; L. (Ju.) vaṭ m. ʻ anything twisted ʼ; Si. vaṭa ʻ round ʼ, vaṭa -- ya ʻ circle, girth (esp. of trees) ʼ; Md. va'ʻ round ʼ GS 58; -- Paš.ar. waṭṭəwīˊk, waḍḍawik ʻ kidney ʼ ( -- wĭ̄k vr̥kká -- ) IIFL iii 3, 192?(CDIAL 12069) வட்டம்போர் vaṭṭam-pōr, n. < வட்டு +. Dice-play; சூதுபோர். (தொல். எழுத். 418, இளம்பூ.)வட்டச்சொச்சவியாபாரம் vaṭṭa-c-cocca-viyāpāram, n. < id. + சொச்சம் +. Money-changer's trade; நாணயமாற்று முதலிய தொழில். Pond. வட்டமணியம் vaṭṭa-maṇiyam, n. < வட் டம் +. The office of revenue collection in a division; வட்டத்து ஊர்களில் வரிவசூலிக்கும் வேலை. (R. T .) వట్ట (p. 1123) vaṭṭa vaṭṭa. [Tel.] n. The bar that turns the centre post of a sugar mill. చెరుకుగానుగ రోటినడిమిరోకలికివేయు అడ్డమాను. వట్టకాయలు or వట్టలు vaṭṭa-kāyalu. n. plu. The testicles. వృషణములు, బీజములు. వట్టలుకొట్టు to castrate. lit: to strike the (bullock's) stones, (which are crushed with a mallet, not cut out.) వట్ర (p. 1123) vaṭra or వట్రన vaṭra. [from Skt. వర్తులము.] n. Roundness. నర్తులము, గుండ్రన. వట్ర. వట్రని or వట్రముగానుండే adj. Round. గుండ్రని.

धाव (p. 250) dhāva m f A certain soft, red stone. Baboons are said to draw it from the bottom of brooks, and to besmear their faces with it. धवड (p. 249) dhavaḍa m (Or धावड) A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावड (p. 250) dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावडी (p. 250) dhāvaḍī a Relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron.

Meluhha artisans, Indus script writers draw circles with small radii to signify dhātu, dhāv 'mineral' hypertexts

kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'. Thus, three dotted circles (trefoil) signify

dhāvaḍa kolimi 'smelter smithy, forge'.

वृत्त [p= 1009,2] mfn. turned , set in motion (as a wheel) RV.; a circle; vr̥ttá ʻ turned ʼ RV., ʻ rounded ʼ ŚBr. 2. ʻ completed ʼ MaitrUp., ʻ passed, elapsed (of time) ʼ KauṣUp. 3. n. ʻ conduct, matter ʼ ŚBr., ʻ livelihood ʼ Hariv. [√

धाव (p. 250) dhāva m f A certain soft, red stone. Baboons are said to draw it from the bottom of brooks, and to besmear their faces with it. धवड (p. 249) dhavaḍa m (Or धावड) A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावड (p. 250) dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावडी (p. 250) dhāvaḍī a Relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron.

"Kashi, Kakar Wari Ajrak, Naar Ji Ajrak, Dabli wari, Taidi, Hansho Wall are the main verities of Ajrak. Today in Sindh Ajraks are made mainly in Bhitt Shah, Tando Adam, Tando Mohammad Khan, Matli and Sukkur. Block printing is the original form of Ajrak making...History: Ajrak is a block printed shawl in Sindh, Pakistan; Kutch, Gujarat; and Barmer, Rajasthan in India. The shawls display special designs and patterns made using block printing stamps of wood. Common colours used while making these patterns may include but are not limited to blue, red, black, yellow and green. Over the years, ajrak have become a symbol of Sindhi culture and traditions."

Artifacts from Jiroft.

Artifacts from Jiroft.

Ivory combs. Turkmenistan.

Ivory objects. Sarasvati Civilization

Tablets.Ivory objects. Mohenjo-daro.

Button seal. Baror, Rajasthan.

Courtesy: manasataramgini @blog_supplement

Indus Script hypertext, dot + circles = dāya 'one in dice' + vaṭṭa 'circle' rebus dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter'

A Harappan button. Note how they had an instrument to precisely mark small circles of various radii![]()

Button tablet. Harappa. Dotted circles.

![File:Musée GR de Saint-Romain-en-Gal 27 07 2011 13 Des et jetons.jpg]()

Button tablet. Harappa. Dotted circles.

Dices and chips in bone, Roman time. Gallo-Roman Museum of Saint-Romain-en-Gal-Vienne.

Indus Script hypertext/hieroglyph: Dotted circle: दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)

தாயம் tāyam:Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. (Tamil)

rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ(whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻrelic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773) धाव (p. 250) dhāva m f A certain soft, red stone. Baboons are said to draw it from the bottom of brooks, and to besmear their faces with it. धावड (p. 250) dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. In these parts they are Muhammadans. धावडी (p. 250) dhāvaḍī a Relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron. (Marathi).

PLUS

Hieroglyph: vaṭṭa 'circle'.

Thus, together, the hypertext reads rebus dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter'

The dotted circle hypertexts link with 1. iron workers called धावड (p. 250) dhāvaḍa and 2. miners of Mosonszentjános, Hungary; 3. Gonur Tepe metalworkers, metal traders and 4. the tradition of अक्ष-- पटल [p= 3,2] n. court of law; depository of legal document Ra1jat. Thus, अक्ष on Indus Script Corpora signify documents, wealth accounting ledgers of metal work with three red ores. Akkha2 [Vedic akṣa, prob. to akṣi & Lat. oculus, "that which has eyes" i. e. a die; cp. also Lat. ālea game at dice (fr.* asclea?)] a die D i. 6 (but expld at DA i. 86 as ball -- game: guḷakīḷa); S i. 149 = A v. 171 = Sn 659 (appamatto ayaŋ kali yo akkhesu dhanaparājayo); J i. 379 (kūṭ˚ a false player, sharper, cheat) anakkha one who is not a gambler J v. 116 (C.: ajūtakara). Cp. also accha3 . -- dassa (cp. Sk. akṣadarśaka) one who looks at (i. e. examines) the dice, an umpire, a judge Vin iii. 47; Miln 114, 327, 343 (dhamma -- nagare). -- dhutta one who has the vice of gambling D ii. 348; iii. 183; M iii. 170; Sn 106 (+ itthidhutta & surādhutta). -- vāṭa fence round an arena for wrestling J iv. 81. (? read akka -- ).

దాయము (p. 588) dāyamu dāyamu. [Skt.] n. Heritage. పంచుకొనదగినతంత్రిసొమ్ము. Kinship, heirsh జ్ఞాతిత్వము. A gift, ఈవి. దాయము, దాయలు or దాయాలు dāyamu. [Tel.] n. A certain game among girls. గవ్వలాట; గవ్వలు పాచికలు మొదలగువాని సంఖ్య. (Telugu)

ஏர்த்தாயம் ēr-t-tāyam , n. < id. +. Ploughing in season; பருவகாலத்துழவு. (W.)காணித்தாயவழக்கு kāṇi-t-tāya-vaḻakku, n. < id. +. Dispute between coparceners about hereditary land; பங்காளிகளின் நிலவழக்கு. (J.)தர்மதாயம் tarma-tāyam , n. < id. + dāya. Charitable inams; தருமத்துக்கு விடப்பட்ட மானியம். (G. Sm. D. I, ii, 55.)தாயம் tāyam

ஏர்த்தாயம் ēr-t-tāyam , n. < id. +. Ploughing in season; பருவகாலத்துழவு. (W.)காணித்தாயவழக்கு kāṇi-t-tāya-vaḻakku, n. < id. +. Dispute between coparceners about hereditary land; பங்காளிகளின் நிலவழக்கு. (J.)தர்மதாயம் tarma-tāyam , n. < id. + dāya. Charitable inams; தருமத்துக்கு விடப்பட்ட மானியம். (G. Sm. D. I, ii, 55.)தாயம் tāyam

, n. < dāya. 1. Patrimony, inheritance, wealth of an ancestor capable of inheritance and partition (R. F.); பாகத்திற்குரிய பிதிரார்ச்சிதப்பொருள். 2. Share; பங்கு. (யாழ். அக.) 3. Paternal relationship; தந்தைவழிச் சுற்றம். (யாழ். அக.) 4. A fall of the dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் விருத்தம். முற்பட இடுகின்ற தாயம் (கலித். 136, உரை). 5. Cubical pieces in dice-play; கவறு. (யாழ். அக.) 6. Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. 7. Gift, donation; கொடை. (யாழ். அக.) 8. Good opportunity; சமயவாய்ப்பு. (யாழ். அக.) 9. Affliction, distress; துன்பம். (யாழ். அக.) 10. Delay, stop; தாக்காட்டு. (W.) 11. A child's game played with seeds or shells on the ground; குழந்தை விளையாட்டுவகை. 12. Excellence, superiority; மேன்மை. தாயமாம் பதுமினிக்கு (கொக்கோ. 1, 28).தாயப்பதி tāya-p-pati

n. < id. +. City or town got by inheritance; தனக்கு உரிமையாகக் கிடைத்துள்ள வாழிடம்

அல்லது

ஊர். தாயப்பதிகள் தலைச்சிறந் தெங்கெங்கும் (திவ். திருவாய். 8, 6, 9).தாயபாகம் tāya-pākam

, n. < dāyabhāga. 1. Division of an estate among heirs; ஞாதிகள் தம்முள் பிரித்துக்கொள்ளும் உரிமைப்பங்கு. 2. A treatise on the Hindu law of inheritance by Jīmūtavākaṉa; பாகப்பிரிவினையைப்பற்றி ஜீமூத வாகனர் இயற்றிய நூல். 3. Chapter on the law of inheritance in the Mitākṣara of Vijñāṉēšvara, 12th c. (R. F.); பன்னிரண்டாம் நூற்றாண்டில் விஞ் ஞானேசுரர் இயற்றிய மிதாக்ஷரத்தில் தாயவுரிமை யைப்பற்றிக் கூறும் பகுதி.தாயம் tāyam, n. < dāya. 1. Patrimony, inheritance, wealth of an ancestor capable of inheritance and partition (R. F.); பாகத்திற்குரிய பிதிரார்ச்சிதப்பொருள். 2. Share; பங்கு. (யாழ். அக.) 3. Paternal relationship; தந்தைவழிச் சுற்றம். (யாழ். அக.) 4. A fall of the dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் விருத்தம். முற்பட இடுகின்ற தாயம் (கலித். 136, உரை). 5. Cubical pieces in dice-play; கவறு. (யாழ். அக.) 6. Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. 7. Gift, donation; கொடை. (யாழ். அக.) 8. Good opportunity; சமயவாய்ப்பு. (யாழ். அக.) 9. Affliction, distress; துன்பம். (யாழ். அக.) 10. Delay, stop; தாக்காட்டு. (W.) 11. A child's game played with seeds or shells on the ground; குழந்தை விளையாட்டுவகை. 12. Excellence, superiority; மேன்மை. தாயமாம் பதுமினிக்கு (கொக்கோ. 1, 28).

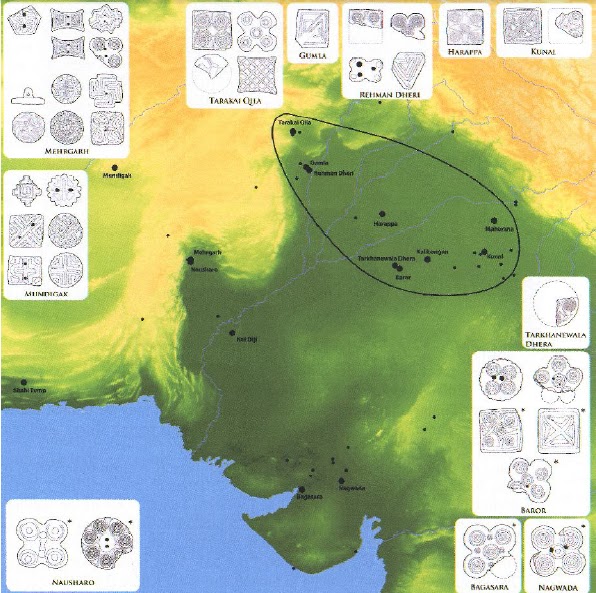

Kot Diji type seals with concentric circles from (a,b) Taraqai Qila (Trq-2 &3, after CISI 2: 414), (c,d) Harappa(H-638 after CISI 2: 304, H-1535 after CISI 3.1:211), and (e) Mohenjo-daro (M-1259, aftr CISI 2: 158). (From Fig. 7 Parpola, 2013).

Distribution of geometrical seals in Greater Indus Valley during the early and *Mature Harappan periods (c. 3000 - 2000 BCE). After Uesugi 2011, Development of the Inter-regional interaction system in the Indus valley and beyond: a hypothetical view towards the formation of the urban society' in: Cultural relagions betwen the Indus and the Iranian plateau during the 3rd millennium BCE, ed. Toshiki Osada & Michael Witzel. Harvard Oriental Series, Opera Minora 7. Pp. 359-380. Cambridge, MA: Dept of Sanskrit and Indian Studies, Harvard University: fig.7

The + glyph of Sibri evidence is comparable to the large-sized 'dot', dotted circles and + glyph shown on this Mohenjo-daro seal m0352 with dotted circles repeated on 5 sides A to F. Mohenjo-daro Seal m0352 shows dotted circles in the four corners of a fire-altar and at the centre of the altar together with four raised 'bun' ingot-type rounded features. Rebus readings of m0352 hieroglyphs:

The + glyph of Sibri evidence is comparable to the large-sized 'dot', dotted circles and + glyph shown on this Mohenjo-daro seal m0352 with dotted circles repeated on 5 sides A to F. Mohenjo-daro Seal m0352 shows dotted circles in the four corners of a fire-altar and at the centre of the altar together with four raised 'bun' ingot-type rounded features. Rebus readings of m0352 hieroglyphs:dhātu 'layer, strand'; dhāv 'strand, string' Rebus: dhāu, dhātu 'ore'

1. Round dot like a blob -- . Glyph: raised large-sized dot -- (gōṭī ‘round pebble);goTa 'laterite (ferrite ore)

2. Dotted circle khaṇḍa ‘A piece, bit, fragment, portion’; kandi ‘bead’;

3. A + shaped structure where the glyphs 1 and 2 are infixed. The + shaped structure is kaṇḍ ‘a fire-altar’ (which is associated with glyphs 1 and 2)..

Rebus readings are: 1. khoṭ m. ʻalloyʼgoTa 'laterite (ferrite ore); 2. khaṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’; 3. kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar, consecrated fire’.

Four ‘round spot’; glyphs around the ‘dotted circle’ in the center of the composition: gōṭī ‘round pebble; Rebus 1: goTa 'laterite (ferrite ore); Rebus 2:L. khoṭf ʻalloy, impurityʼ, °ṭā ʻalloyedʼ, awāṇ. khoṭā ʻforgedʼ; P. khoṭ m. ʻbase, alloyʼ M.khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ (CDIAL 3931) Rebus 3: kōṭhī ] f (कोष्ट S) A granary, garner, storehouse, warehouse, treasury, factory, bank. khoṭā ʻalloyedʼ metal is produced from kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’ yielding khaṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’. This word khaṇḍā is denoted by the dotted circles.

Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.A Stamp seal and its impression from the Harappan site of Lothal north of Bombay, of the type also found in the contemporary cultures of southern Iraq and the Persian Gulf Area. http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/archaeology-in-india/

These powerful narratives are also validated -- archaeologically attested -- by the discovery of Mohenjo-daro priest wearing (on his forehead and on the right shoulder) fillets of a dotted circle tied to a string and with a uttarīyam decorated with one, two, three dotted circles. The fillet is an Indus Script hypertext which reads: dhã̄i 'strand' PLUS vaṭa 'string' rebus: dhāvaḍ 'smelter'. The same dotted circles enseemble is also shown as a sacred hieroglyph on the bases of Śivalingas found in Mohenjo-dar. The dotted circles are painted with red pigment, the same way as Mosonszentjanos dice are painted with red iron oxide pigment.

वट [p= 914,3] m. (perhaps Prakrit for वृत , " surrounded , covered " ; cf. न्यग्-रोध) the Banyan or Indian fig. tree (Ficus Indica) MBh.Ka1v. &c RTL. 337 (also said to be n.); a pawn (in chess) L. (Monier-Williams) Ta. vaṭam cable, large rope, cord, bowstring, strands of a garland, chains of a necklace; vaṭi rope; vaṭṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to tie. Ma. vaṭam rope, a rope of cowhide (in plough), dancing rope, thick rope for dragging timber. Ka. vaṭa, vaṭara, vaṭi string, rope, tie. Te. vaṭi rope, cord. Go. (Mu.) vaṭiya strong rope made of paddy straw (Voc. 3150). Cf. 3184 Ta. tār̤vaṭam. / Cf. Skt. vaṭa- string, rope, tie; vaṭāraka-, vaṭākara-, varāṭaka- cord,string; Turner, CDIAL, no. 11212. (CDIAL 5220)vaṭa2 ʻ string ʼ lex. [Prob. ← Drav. Tam. vaṭam, Kan. vaṭi, vaṭara, &c. DED 4268] N. bariyo ʻ cord, rope ʼ; Bi. barah ʻ rope working irrigation lever ʼ, barhā ʻ thick well -- rope ʼ, Mth. barahā ʻ rope ʼ. (CDIAL 11212).

See: https://tinyurl.com/y85goask Wealth of a nation...

Trefoil decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. Steatite statue fragment. Mohenjo-daro (Sd 767). After Ardeleanu-Jansen, 1989: 196, fig. 1; cf. Parpola, 1994, p. 213. Trefoils painted on steatite beads. Harappa (After Vats. Pl. CXXXIII, Fig. 2) Trefoil on the shawl of the priest. Mohenjodaro. The discovery of the King Priest acclaimed by Sir John Marshall as “the finest piece of statuary that has been found at Moenjodaro….draped in an elaborate shawl with corded or rolled over edge, worn over the left shoulder and under the right arm. This shawl is decorated all over with a design of trefoils in relief interspersed occasionally with small circles, the interiors of which are filled with a red pigment “. Gold fillet with ‘standard device’ hieroglyph. Glyph ‘hole’: pottar, பொத்தல் pottal, n. < id. [Ka.poṭṭare, Ma. pottu, Tu.potre.] trika, a group of three (Skt.) The occurrence of a three-fold depiction on a trefoil may thus be a phonetic determinant, a suffix to potṛ as in potṛka.

Rebus reading of the hieroglyph: potti ‘temple-priest’ (Ma.) potR `" Purifier "'N. of one of the 16 officiating priests at a sacrifice (the assistant of the Brahman), यज्ञस्य शोधयिट्रि (Vedic) Rebus reading is: potri ‘priest’; poTri ‘worship, venerate’. Language is Meluhha (Mleccha) an integral component of Indian sprachbund (linguistic area or language union). The trefoil is decoded and read as: potr(i).

Steatite statue fragment; Mohenjodaro (Sd 767); trefoil-decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. After Ardeleanu-Jansen 1989: 196, fig. 1; Parpola, 1994, p. 213.

Steatite statue fragment; Mohenjodaro (Sd 767); trefoil-decorated bull; traces of red pigment remain inside the trefoils. After Ardeleanu-Jansen 1989: 196, fig. 1; Parpola, 1994, p. 213.![Harappa Terracotta bangle fragments]()

One badge used had a bangle with trefoil hieroglyph.

It was suggested that this may relate to the functions of a dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter' tri-dhAtu,'‘three

minerals'.

Terracotta bangle fragments decorated with red trefoils outlined in white

on a green ground from the late Period 3C deposits in Trench 43. This image

shows both sides of the two fragments

(H98-3516/8667-01 & H98-3517/8679-01)

Detail of terracotta bangle with red and white trefoil on a green background H98-3516/8667-01 from Trench 43).

Detail of terracotta bangle with red and white trefoil on a green background H98-3516/8667-01 from Trench 43).  miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda)

miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)mẽṛh t iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda) "Late Harappan Period dish or lid with perforation at edge for hanging or attaching to large jar. It shows a Blackbuck antelope with trefoil design made of combined circle-and-dot motifs, possibly representing stars. It is associated with burial pottery of the Cemetery H period,dating after 1900 BC.The Late Harappan Period at Harappa is represented by the Cemetery H culture (190-1300 BC) which is named after the discovery of a large cemetery filled with painted burial urns and some extended inhumations. The earlier burials in this cemetery were laid out much like Harappan coffin burials, but in the later burials, adults were cremated and the bones placed in large urns (164). The change in burial customs represents a major shift in religion and can also be correlated to important changes in economic and political organization. Cemetery H pottery and related ceramics have been found throughout northern Pakistan, even as far north as Swat, where they mix with distinctive local traditions. In the east, numerous sites in the Ganga-Yamuna Doab provide evidence for the gradual expansion of settlements into this heavily forested region. One impetus for this expansion may have been the increasing use of rice and other summer (kharif) crops that could be grown using monsoon stimulated rains. Until late in the Harappan Period (after 2200 BC) the agricultural foundation of the Harappan cities was largely winter (rabi) crops that included wheat and barley. Although the Cemetery H culture encompassed a relatively large area, the trade connections with thewestern highlands began to break down as did the trade with the coast. Lapis lazuli and turquoise beads are rarely found in the settlements, and marine shell for ornaments and ritual objects gradually disappeared. On the other hand the technology of faience manufacture becomes more refined, possibly in order to compensate for the lack of raw materials such as shell, faience and possibly even carnelian." (Kenoyer in harappa.com slide description)http://www.harappa.com/indus2/162.htm

Trefoil motifs are carved on the robe of the so-called "priest-king" statuette from Mohenjo-daro and are also known from contemporary sites in western Pakistan, Afghanistan, and southern Central Asia.dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter' tri-dhAtu,'‘three minerals". त्रिधातु mfn. consisting of 3 parts , triple , threefold (used like Lat. triplex to denote excessive)RV. S3Br. v , 5 , 5 , 6; n. the aggregate of the 3 minerals.tri त्रिधा ind. in 3 parts, ways or places; triply, ˚त्वम् tripartition; Ch. Up. -धातुः an epithet of Gaṇeśa. dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼMBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ

lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f.ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

त्रिधातुः is an epithet of Gaṇeśa. This may indicate three forms of ferrite ores: magnetite, haematite, laterite which were identified in Indus Script as poLa 'magnetite', bichi 'haematite' and goTa 'laterite'.

Rebus readings of Indus Script hieroglyphs may explain the त्रिधातुः epithet of Gaṇeśa: karibha 'elephant's trunk' rebus: karba 'iron' ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron'.

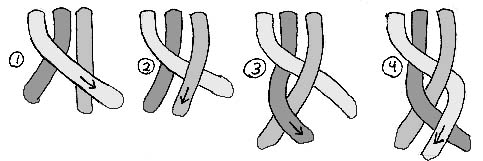

It has been suggested at

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/11/trefoil-of-indus-script-corpora-and.html?view=sidebar that the trefoil decorating the shawl of the 'priest-king' of Mohenjo-daro is a cross-sectional signifier of three strands of rope.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Thus, a dotted circle is signified by the word: dhāī 'wisp of fibre' (Sindhi).

These orthographic variants provide semantic elucidations for a single: dhātu, dhāū, dhāv 'red stone mineral' or two minerals: dul PLUS dhātu, dhāū, dhāv 'cast minerals' or tri- dhātu, -dhāū, -dhāv 'three minerals' to create metal alloys'. The artisans producing alloys are dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -- smeltersʼ, dhāvḍī ʻcomposed of or relating to ironʼ)(CDIAL 6773).

dām 'rope, string' rebus: dhāu 'ore' rebus: मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ 'iron, copper' (Munda. Slavic) mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda).

Semantics of single strand of rope and three strands of rope are: 1. Sindhi dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, Lahnda dhāī˜ id.; 2. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ (RigVeda)

Ta. vaṭam cable, large rope, cord, bowstring, strands of a garland, chains of a necklace; vaṭi rope; vaṭṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to tie. Ma. vaṭam rope, a rope of cowhide (in plough), dancing rope, thick rope for dragging timber. Ka. vaṭa, vaṭara, vaṭi string, rope, tie. Te. vaṭi rope, cord. Go. (Mu.) vaṭiya strong rope made of paddy straw (Voc. 3150). Cf. 3184 Ta. tār̤vaṭam. / Cf. Skt. vaṭa- string, rope, tie; vaṭāraka-, vaṭākara-, varāṭaka- cord, string; Turner, CDIAL, no. 11212. (DEDR 5220) vaṭa2 ʻ string ʼ lex. [Prob. ← Drav. Tam. vaṭam, Kan. vaṭi, vaṭara, &c. DED 4268]N. bariyo ʻ cord, rope ʼ; Bi. barah ʻ rope working irrigation lever ʼ, barhā ʻ thick well -- rope ʼ, Mth. barahā ʻ rope ʼ.(CDIAL 11212)

I suggest that the expression dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter' signified by trefoil or three strands is a semantic duplication of the parole words: dhāī 'wisp of fibre' PLUS vaṭa, vaṭara, vaṭi string, rope, tie. Thus, it is possible that the trefoil as a hieroglyph-multiplex was signified in parole by the expression dhā̆vaḍ 'three strands' rebus: dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter'.

The shawl decorated with dhā̆vaḍ 'trefoil' is a hieroglyph: pōta 'cloth' rebus:

पोता पोतृ, 'purifier' in a yajna. போற்றி pōṟṟi, போத்தி pōtti Brahman temple- priest in Malabar; மலையாளத்திலுள்ள கோயிலருச் சகன். Marathi has a cognate in

पोतदार [pōtadāra] m ( P) An officer under the native governments. His business was to assay all money paid into the treasury. He was also the village-silversmith.

पोता पोतृ, 'purifier' in a yajna. போற்றி pōṟṟi, போத்தி pōtti Brahman temple- priest in Malabar; மலையாளத்திலுள்ள கோயிலருச் சகன். Marathi has a cognate in

पोतदार [pōtadāra] m ( P) An officer under the native governments. His business was to assay all money paid into the treasury. He was also the village-silversmith.

पोता, [ऋ] पुं, (पुनातीति । पू + “नप्तृनेष्टृ-त्वष्टृहोतृपोतृभ्रातृजामातृमातृपितृदुहितृ ।”उणा० २ । ९६ । इति तृन्प्रत्ययेन निपात्यते ।) विष्णुः । इति संक्षिप्तसारोणादिवृत्तिः ॥ऋत्विक् । इति भूरिप्रयोगः ॥ (यथा, ऋग्वेदे ।४ । ९ । ३ ।“स सद्म परि णीयते होता मन्द्रो दिविष्टिषु ।उत पोता नि षीदति ॥”)

https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/शब्दकल्पद्रुमः पोतृ [p= 650,1] प्/ओतृ or पोतृ, m. " Purifier " , N. of one of the 16 officiating priests at a sacrifice (the assistant of the Brahman ; = यज्ञस्य शोधयिट्रि Sa1y. )

पोतृ m. One of the sixteen officiating priests at a sacrifice (assistant of the priest called ब्रह्मन्). पोत्रम् [पू-त्र] The office of the Potṛi. ब्रह्मन् m. one of the 4 principal priests or ऋत्विज्as (the other three being the होतृ , अध्वर्यु and उद्गातृ ; the ब्रह्मन् was the most learned of them and was required to know the 3 वेदs , to supervise the sacrifice and to set right mistakes ; at a later period his functions were based especially on the अथर्व-वेद) RV. &c होतृ m. (fr. √1. हु) an offerer of an oblation or burnt-offering (with fire) , sacrificer , priest , (esp.) a priest who at a sacrifice invokes the gods or recites the ऋग्-वेद , a ऋग्-वेद priest (one of the 4 kinds of officiating priest »ऋत्विज् , p.224; properly the होतृ priest has 3 assistants , sometimes called पुरुषs , viz. the मैत्रा-वरुण , अच्छा-वाक, and ग्रावस्तुत् ; to these are sometimes added three others , the ब्राह्मणाच्छंसिन् , अग्नीध्र or अग्नीध् , and पोतृ , though these last are properly assigned to the Brahman priest ; sometimes the नेष्टृ is substituted for the ग्राव-स्तुत्) RV.&c नेष्टृ m. (prob. fr. √ नी aor. stem नेष् ; but cf. Pa1n2. 3-2 , 135 Va1rtt. 2 &c ) one of the chief officiating priests at aसोम sacrifice , he who leads forward the wife of the sacrificer and prepares the सुरा (त्वष्टृ so called RV. i , 15 , 3) RV. Br. S3rS. &c अध्वर्यु m. one who institutes an अध्वर any officiating priest a priest of a particular class (as distinguished from the होतृ , the उद्गातृ , and the ब्रह्मन् classes. The अध्वर्युpriests " had to measure the ground , to build the altar , to prepare the sacrificial vessels , to fetch wood and water , to light the fire , to bring the animal and immolate it " ; whilst engaged in these duties , they had to repeat the hymns of the यजुर्-वेद , hence that वेद itself is also called अध्वर्यु)pl. (अध्वर्यवस्) the adherents of the यजुर्-वेद; उद्-गातृ m. one of the four chief-priests (viz. the one who chants the hymns of the सामवेद) , a chanterRV. ii , 43 , 2 TS. AitBr. S3Br. Ka1tyS3r. Sus3r. Mn. &c

अच्छा-वाकm. " the inviter " , title of a particular priest or ऋत्विज् , one of the sixteen required to perform the great sacrifices with the सोम juice. ग्रावन् m. a stone for pressing out the सोम (originally 2 were used RV. ii , 39 , 1 ; later on 4 [ S3a1n3khBr.xxix , 1] or 5 [Sch. on S3Br. &c ]) RV. AV. VS. S3Br.= ग्राव-स्त्/उत् Hariv. 11363

pōtrá1 ʻ *cleaning instrument ʼ (ʻ the Potr̥'s soma vessel ʼ RV.). [√pū]Bi. pot ʻ jeweller's polishing stone ʼ? -- Rather < *pōttī -- .(CDIAL 8404) *pōttī ʻ glass bead ʼ.Pk. pottī -- f. ʻ glass ʼ; S. pūti f. ʻ glass bead ʼ, P. pot f.; N. pote ʻ long straight bar of jewelry ʼ; B. pot ʻ glass bead ʼ, puti, pũti ʻ small bead ʼ; Or. puti ʻ necklace of small glass beads ʼ; H. pot m. ʻ glass bead ʼ, G. M. pot f.; -- Bi. pot ʻ jeweller's polishing stone ʼ rather than < pōtrá --(CDIAL 8403) pōtana पोतन a. 1 Sacred, holy. -2 Purifying.

Hence the importance of the office of Potr̥, 'Rigvedic priest of a yajna' signified as 'purifier', an assayer of dhāˊtu 'minerals.

I suggest that this fillet (dotted circle with a connecting strand or tape is the hieroglyph which signifies धातु (Rigveda) dhāu (Prakrtam) 'a strand' rebus: element, mineral ore. This hieroglyph signifies the पोतृ,'purifier' priest of dhā̆vaḍ 'iron-smelters' of dhāū, dhāv 'red stone minerals'.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/11/priest-of-dhavad-iron-smelters-with.html Orthography of the 'dotted circle' is representation of a single strand: dhāu rebus: dhāū 'red stone minerals.

It is this signifier which occurs in the orthography of the dotted circle hieroglyph-multiplex on early punch-marked coins of Magadha -- a proclamation of the dhāū 'element, mineral ores' used in the Magadha mint. On one Silver Satamana punch-marked coin of Gandhara septa-radiate or, seven strands emerge from the dotted circle signifying the use in the mint of सप्त--धातु 'seven mineral ores'.

நெற்றிப்பட்டம் neṟṟi-p-paṭṭam, n. < id. +. Thin plate of metal worn on the forehead, as an ornament or badge of distinction; நுதலி லணியும் பட்டம். (W.)

பட்டம்² paṭṭam, n. < paṭṭa. 1. Plate of gold worn on the forehead, as an ornament or badge of distinction; சிறப்புக்கு அறிகுறியாக நெற்றி யிலணியும் பொற்றகடு. பட்டமுங் குழையு மின்ன (சீவக. 472). 2. An ornament worn on the forehead by women; மாதர் நுதலணி. பட்டங் கட்டிப்பொற்றோடு பெய்து (திவ். பெரியாழ். 3, 7, 6). 3. Title, appellation of dignity, title of office; பட்டப்பெயர். பட்டமும் பசும்பொற் பூணும் பரந்து (சீவக. 112). 4. Regency; reign; ஆட்சி. 5. Fasteners, metal clasp; சட்டங்களை இணைக்க உதவும் தகடு. ஆணிகளும் பட்டங்களுமாகிய பரிய இரும்பாலேகட்டி (நெடுநல். 80, உரை). High position; உயர் பதவி. (பிங்.)

பட்டை² paṭṭai

, n. < paṭṭa. [T. K. paṭṭe, M. paṭṭam.] 1. Plate, slab, tablet; தகடு. 2. Flatness; தட்டையான தன்மை. 3. Lace-border; சரிகைப்பட்டை. 4. Painted stripe, as on a temple wall; பட்டைக்கோடு. 5. Dapple, piebald colour;

தட்டார்பாட்டம் taṭṭār-pāṭṭam

, n. < தட் டான்¹ +. Profession tax on goldsmiths; தட்டார் இறுக்கும் அரசிறைவகை. (S. I. I. ii, 117.)

http://www.harappa.com/indus/43.html Seated male sculpture, or "Priest King" from Mohenjo-daro (41, 42, 43). Fillet or ribbon headband with circular inlay ornament on the forehead and similar but smaller ornament on the right upper arm. The two ends of the fillet fall along the back and though the hair is carefully combed towards the back of the head, no bun is present. The flat back of the head may have held a separately carved bun as is traditional on the other seated figures, or it could have held a more elaborate horn and plumed headdress.

Two holes beneath the highly stylized ears suggest that a necklace or other head ornament was attached to the sculpture. The left shoulder is covered with a cloak decorated with trefoil, double circle and single circle designs that were originally filled with red pigment. Drill holes in the center of each circle indicate they were made with a specialized drill and then touched up with a chisel. Eyes are deeply incised and may have held inlay. The upper lip is shaved and a short combed beard frames the face. The large crack in the face is the result of weathering or it may be due to original firing of this object.

Material: white, low fired steatite

Dimensions: 17.5 cm height, 11 cm width

Mohenjo-daro, DK 1909

National Museum, Karachi, 50.852

Marshall 1931: 356-7, pl. XCVIII

(After Ardeleanu-Jansen, A., 'The sculptural art of the Harappan culture' in M Jansen et al, ed., Forgotten cities on the Indus: early cvilization in Pakistan from the 8th to the 2nd millennium BCE, Mainz: Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 1991.)

Role of dice in Bhāratīya Itihāsa, dotted circle Indus Script hypertexts on ivory game pieces of ANE miners and a tribute to Dennys Frenez, István Koncz and Zsuzsanna Tóth for their brilliant archaeological insights and riveting, logically argued archeo-metallurgical analyses.

Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)

Mohenjo-daro (Ashmolean Museum), Harappa dice.. दाय 1 [p= 474,2] dāya n. game , play Pan5cad.; mfn. ( Pa1n2. 3-1 , 139 ; 141) giving , presenting (cf. शत- , गो-); m. handing over , delivery Mn. viii , 165 (Monier-Williams)தாயம் tāyam:Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. (Tamil)

See:

goṭi, ‘silver, laterite’ are signified by goṭa, ‘seed’ hieroglyph. gōṭh गोठ् । अष्टापदम्, इष्टफलम् f. (sg. dat.gōṭi गोटि ), a kind of chequered cloth of thirty-six squares for playing chess, causar, or similar game, a dice-board; an aim, desired object. -- marüñü-- मर&above;ञू&below; । इष्टावाप्तिः f.inf. to obtain a desired object, achieve one's object.(Kashmiri)

Hieroglyph: seed, something round: *gōṭṭa ʻ something round ʼ. [Cf. guḍá -- 1. -- In sense ʻ fruit, kernel ʼ cert. ← Drav., cf. Tam. koṭṭai ʻ nut, kernel ʼ, Kan. goṟaṭe &c. listed DED 1722]K. goṭh f., dat. °ṭi f. ʻ chequer or chess or dice board ʼ; S. g̠oṭu m. ʻ large ball of tobacco ready for hookah ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; P. goṭ f. ʻ spool on which gold or silver wire is wound, piece on a chequer board ʼ; N. goṭo ʻ piece ʼ, goṭi ʻ chess piece ʼ; A. goṭ ʻ a fruit, whole piece ʼ, °ṭā ʻ globular, solid ʼ, guṭi ʻ small ball, seed, kernel ʼ; B. goṭā ʻ seed, bean, whole ʼ; Or. goṭā ʻ whole, undivided ʼ, goṭi ʻ small ball, cocoon ʼ, goṭāli ʻ small round piece of chalk ʼ; Bi. goṭā ʻ seed ʼ; Mth. goṭa ʻ numerative particle ʼ; H. goṭf. ʻ piece (at chess &c.) ʼ; G. goṭ m. ʻ cloud of smoke ʼ, °ṭɔ m. ʻ kernel of coconut, nosegay ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ lump of silver, clot of blood ʼ, °ṭilɔ m. ʻ hard ball of cloth ʼ; M. goṭā m. ʻ roundish stone ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ a marble ʼ, goṭuḷā ʻ spherical ʼ; Si. guṭiya ʻ lump, ball ʼ; -- prob. also P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ.*gōḍḍ -- ʻ dig ʼ see *khōdd -- .Addenda: *gōṭṭa -- : also Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271) Ta. koṭṭai seed of any kind not enclosed in chaff or husk, nut, stone, kernel; testicles; (RS, p. 142, items 200, 201) koṭṭāṅkacci, koṭṭācci coconut shell. Ma. koṭṭakernel of fruit, particularly of coconut, castor-oil seed; kuṟaṭṭa, kuraṭṭa kernel; kuraṇṭi stone of palmfruit. Ko. keṭ testes; scrotum. Ka. koṭṭe, goṟaṭe stone or kernel of fruit, esp. of mangoes; goṭṭa mango stone. Koḍ. koraṇḍi id. Tu. koṭṭè kernel of a nut, testicles; koṭṭañji a fruit without flesh; koṭṭayi a dried areca-nut; koraṇtu kernel or stone of fruit, cashew-nut; goṭṭu kernel of a nut as coconut, almond, castor-oil seed. Te. kuriḍī dried whole kernel of coconut. Kol. (Kin.) goṛva stone of fruit. Nk. goṛage stone of fruit. Kur. goṭā any seed which forms inside a fruit or shell. Malt. goṭa a seed or berry. / Cf. words meaning 'fruit, kernel, seed' in Turner, CDIAL, no. 4271 (so noted by Turner).(DEDR 2069) Rebus: khōṭa 'alloy ingot' (Marathi)

, n. < dāya. 1. Patrimony, inheritance, wealth of an ancestor capable of inheritance and partition (R. F .); பாகத்திற்குரிய பிதிரார்ச்சிதப்பொருள். 2. Share; பங்கு. (யாழ். அக.) 3. Paternal relationship; தந்தைவழிச் சுற்றம். (யாழ். அக.) 4. A fall of the dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் விருத்தம். முற்பட இடுகின்ற தாயம் (கலித். 136, உரை). 5. Cubical pieces in dice-play; கவறு. (யாழ். அக.) 6. Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண். Colloq. 7. Gift, donation; கொடை. (யாழ். அக.) 8. Good opportunity; சமயவாய்ப்பு. (யாழ். அக.) 9. Affliction, distress; துன்பம். (யாழ். அக.) 10. Delay, stop; தாக்காட்டு. (W .) 11. A child's game played with seeds or shells on the ground; குழந்தை விளையாட்டுவகை. 12. Excellence, superiority; மேன்மை. தாயமாம் பதுமினிக்கு (கொக்கோ. 1, 28).தாயப்பதி tāya-p-pati

n. < id. +. City or town got by inheritance; தனக்கு உரிமையாகக் கிடைத்துள்ள வாழிடம்

அல்லது

ஊர். தாயப்பதிகள் தலைச்சிறந் தெங்கெங்கும் (திவ். திருவாய். 8, 6, 9).தாயபாகம் tāya-pākam

A significant find of Mosonszentjános in Hungary reported in a brilliant, scintillating Archaeological excursus by István Koncz and Zsuzsanna Tóth is that the ivory game pieces signified by dotted circles were found in the graves of guild of mine workers.

A significant find of Dennys Frenez reported in a brilliant, scintillating analytical piece on Gonur Tepe archaeological finds of ivories with dotted circles is that the ivory came from Indian elephants. Both these reports are relatable to the most significant event narrated in Bhāratīya Itihāsa of the game of dice in Mahābhārata which resulted in two acts of adharma: Yudhiṣṭhira offering Draupadi as a wager and Duryodhana attempting to disrobe Draupadi in public. This is followed by the act of dharma by Śri Kr̥ṣṇa rescuing Draupadi from the indignity. These powerful narratives, 1. finds of Mosonzzetanos; 2. finds of Gonur Tepe and 3. dice game in Mahābhārata are matched by the fact that the Indus Script rebus words associated with dice are datable from 7th millennium BCE attested in R̥gveda.

"Ajrak printing is a distinguished form of woodblock printing that originated in the present-day province of Sindh, Pakistan and neighbouring Indian districts of Kutch in Gujarat and Barmer in Rajasthan...The essence of ajrak printing is to celebrate nature in terms of the vast use of natural raw materials and resources and the representation of its motifs and colours. For millennia artisans have made use of natural dyes to produce the deep intense colours of ajrak, such as extracts of the madder plant for red and extracts from the true indigo plant for the popular indigo colour. The motifs featured in ajrak print are mainly elaborate geometric jewel-like shapes that incorporate motifs which symbolise nature, such as stars and flowers. Noorjehan Bilgrami, an esteemed artist, textile designer, research and author, has played a major role in the modern-day perpetuation of the art and craft of ajrak printing. Of a common motif found in ajrak print, the trefoil, she writes that it “is thought to be composed of three sun discs fused together to represent the inseparable unity of the Gods of sun, water and earth.”"

L: Ageless traditional ajrak print from Kutch, Gujarat

R: Traditional ajrak print from Barmer, Rajasthan that is still prominent today

The trefoil motif on an ajrak printed shawl

Images: Noorani Biswas, Ruth Clifford, Itokri, D'Source https://strandofsilk.com/journey-map/rajasthan/ajrak-printing/introduction

Ajrak is a canopy for this bullock cart.

Ismail Khatri with his brothers in Ajrakpur, Gujarat

|

| Festivity of Ajrak shawl and Ajrak dresses |

nīˊla is one of the nine treasures of Kubera. This word signifies 1. indigo colour (also called Azrak in Arabic) used for dyeing cotton cloth; 2. indigo colour of lapis lazuli precious stones; 3. Nīla "sapphire" nīla (antimony)

All three commodities are constituents of wealth-creation process in Sarasvati Civilization.

nīˊla ʻ dark blue, dark green, black ʼ RV., nīlaka -- lex. 2. nīˊla -- n. ʻ blue substance ʼ ŚBr., ʻ indigo ʼ Yājñ.

1. Pa. nīla -- , ˚aka -- ʻ dark blue, blue -- green ʼ; Pk. ṇīla<-> ʻ blue, green ʼ, Gy. pal. nīˊlă; Ḍ. nīla ʻ blue, dark green ʼ; Ash. nīˊlestə ʻ green, blue ʼ; Wg. nyīlə, nīrə ʻ blue ʼ, Kt. nīlə, ninyílë, Pr. nīl, nyīˊli, Dm. nīla; Tir. nīlə ʻ green blue ʼ; Paš. nil ʻ dark blue ʼ; Shum. nīl ʻ blue ʼ, Gaw. nīˊla, Kal.urt. nīˊl

Addenda: nīˊla -- . 1. S.kcch. nīlo ʻ green ʼ; Md. nū ʻ blue ʼ, nulē ʻ is blue ʼ.2. nīˊla -- n.: WPah.poet. nīḷ m. ʻ indigo ʼ, J. nīḷ m. ʻ inner part of the blue or other pine ʼ.(CDIAL 7563)*nīlakāra ʻ dyer ʼ. [

"A bust of a priest-king excavated at Mohenjo-daro, currently in theNational Museum of Pakistan, shows him draped over one shoulder in a piece of cloth that resembles an ajrak. Of special note are the trefoilpattern etched on the person's garment interspersed with small circles, the interiors of which were filled with a red pigment...Ajraks are made all over Sindh, especially in Matiari, Hala, Bhit Shah, Moro, Sukkur, Kandyaro, Hyderabad, and many cities of Upper Sindh and Lower Sindh."

"A bust of a priest-king excavated at Mohenjo-daro, currently in theNational Museum of Pakistan, shows him draped over one shoulder in a piece of cloth that resembles an ajrak. Of special note are the trefoilpattern etched on the person's garment interspersed with small circles, the interiors of which were filled with a red pigment...Ajraks are made all over Sindh, especially in Matiari, Hala, Bhit Shah, Moro, Sukkur, Kandyaro, Hyderabad, and many cities of Upper Sindh and Lower Sindh."Fiza Iftikhar September 30, 2013 'The Story of Ajrak': 'History and Making'

We all are very well aware about the benefits of Globalization. Now you must be wondering if I am distracting from the title but it is a fact that due to globalization everything has come close to each other and nothing remains confined to a specific area or culture. But the word that draws the distinctive line between this globalization is belongingness.

We may adopt the culture, inheritance or values of any nation or society but we cannot steal and snatch the foundation and identity of anyone.

Now if we take Ajrak in that context, many people still do not know about the story behind the origin of Ajrak especially our youth may be due to their occupation and the daily emerging international brands their interest has switched and may be because they can find Ajrak anywhere in Pakistan and even across Pakistan too so they may not find it important to explore the history behind it.

Etymology of the Word Ajrak

Pakistan is a blessed country with a variety of cultures in its provinces, be it a lingual aspect or attire, food or whatever.

The word Ajrak is derived from an Arabic word azrak which means blue. It is a cloth of 2.5 “ 3 meters length, decorated mostly with rich crimson and a deep indigo color but a little bit of white and black is also used to give definition to the geometric patterns. It is commonly used in Sindh as men use it as a turban and curled it around the shoulders while women use it as a shawl and sometimes as a makeshift swing for children.

Besides, Sindhis have a special feeling and association for the ajrak and they use Ajrak from cradle to grave. They also wear it without any status barrier on festive occasions like birth, marriage, and death.

History of Ajrak

Tracing the Origins

Pashtuns have their own identity, Punjab stands at its own specialty, just like that Ajrak is an essential part of the Sindhi attire but the origin of the Ajrak can be marked out from the ancient times around 2500 BC – 1500 BC when a statue of King- Priest was quarried from Mohenjo-Daro which had draped a shawl over his shoulder – adorned with a trefoil pattern (like a three leafed clover) sprinkled with small circles filled with a red color.

The trefoil signifies three sun-disks glued together to characterize the unity of the gods of the Sun, water and earth. Since the Ajrak has been used in Sindh for centuries and the block printing techniques and dyes are all ages-old methods of dying cloth but this symbol is still used on the Ajrak these days.

There are also some interesting facts about the use of Ajrak including the Egyptians. They used to clothe their mummies with Ajrak, imported from Sindh which they called Sindhin. In 500 BC, the Ajrak was also presented to Persian King Dara (first) at his crown ceremony. If we elaborate the impression of Ajrak, it is pertinent to know about its importance and use to its native and how it is made.Process of Ajrak Making

Let’s come to the unique and motivating process of Ajrak making. Motivating, because it is more than just daily work but it involves their devotion and spiritual association as Ajrak has a deep root to the Sufi culture that encompasses throughout the Sindh. That’s why we can find more Ajrak makers and their workplace near the shrines in interior Sindh.

The basic four themes used in Ajrak preparation are known as, Teli Ajrak, Sabuni Ajrak, Do Rangi Ajrak and Kori Ajrak.

Fabric Washing and Cleansing (Churrai)

There are numerous steps involved in preparation of Ajrak ranging from 18 to 19 steps but the basic process is called Churrai by local communities. Precisely, the process involves washing cloth and beating to extricate the impurities. The fabric is then soaked in a solution of a special oil and Soda Bicarbonate, which is a complicated procedure and takes several days.

Resist Printing

Next step is the printing of cloth. The real Ajrak is printed on both sides, which is called resist printing. The printing is done by hand carved wooden blocks, which are so perfectly carved so that the pattern is synchronized with the whole of the Ajrak.

Bleaching

In the end the ready Ajraks are again washed in Soda and water with bleaching powder to give brightness to the colors.

The International Fancy for the Intricate Ajrak

Besides being a domain of Sindh culture, Ajrak is profoundly used by everyone not only nationwide but internationally. Ajrak has been exhibited in national exhibitions since many years but these days the scale has been enlarged and display of Ajrak on Expo centers has increase its fame internationally. Many fashion designers are using Ajrak moderately with different ornaments like sequences and Gota work. The integration of traditional customs with contemporary one is a very unique and beautiful amalgamation.

Status of Ajrak Industry in Pakistan

Unfortunately, on the other hand the real local Ajrak industry is declined rapidly, which can be evidently noted from different researches and reports narrated that due to negligence of people, more than 30 ajrak factories have been demolished and replaced by iron steel and other industries. It occurs may be due to the unfavorable wages to the workers. Wholesalers pay very low prices to the craftsmen to keep their profit margin high, due to which no credit facilities are available to the workers resulted in decline of real Ajrak and weaning of traditional sources of livelihood.

This situation eventually leads to the replacement of original Ajrak to the quicker printing method of the copy and fake Ajrak pattern. But the trends have changed again and young generation is very eager to save its heritage and they value this treasure.

This can be seen from the celebration of Ajrak Day at individual and institutional level

Fiza Iftikhar September 30, 2013

We all are very well aware about the benefits of Globalization. Now you must be wondering if I am distracting from the title but it is a fact that due to globalization everything has come close to each other and nothing remains confined to a specific area or culture. But the word that draws the distinctive line between this globalization is belongingness.

We may adopt the culture, inheritance or values of any nation or society but we cannot steal and snatch the foundation and identity of anyone.

Now if we take Ajrak in that context, many people still do not know about the story behind the origin of Ajrak especially our youth may be due to their occupation and the daily emerging international brands their interest has switched and may be because they can find Ajrak anywhere in Pakistan and even across Pakistan too so they may not find it important to explore the history behind it.

Etymology of the Word Ajrak

Pakistan is a blessed country with a variety of cultures in its provinces, be it a lingual aspect or attire, food or whatever.

The word Ajrak is derived from an Arabic word azrak which means blue. It is a cloth of 2.5 “ 3 meters length, decorated mostly with rich crimson and a deep indigo color but a little bit of white and black is also used to give definition to the geometric patterns. It is commonly used in Sindh as men use it as a turban and curled it around the shoulders while women use it as a shawl and sometimes as a makeshift swing for children.

Besides, Sindhis have a special feeling and association for the ajrak and they use Ajrak from cradle to grave. They also wear it without any status barrier on festive occasions like birth, marriage, and death.

History of Ajrak

Tracing the Origins

Pashtuns have their own identity, Punjab stands at its own specialty, just like that Ajrak is an essential part of the Sindhi attire but the origin of the Ajrak can be marked out from the ancient times around 2500 BC – 1500 BC when a statue of King- Priest was quarried from Mohenjo-Daro which had draped a shawl over his shoulder – adorned with a trefoil pattern (like a three leafed clover) sprinkled with small circles filled with a red color.

The trefoil signifies three sun-disks glued together to characterize the unity of the gods of the Sun, water and earth. Since the Ajrak has been used in Sindh for centuries and the block printing techniques and dyes are all ages-old methods of dying cloth but this symbol is still used on the Ajrak these days.

There are also some interesting facts about the use of Ajrak including the Egyptians. They used to clothe their mummies with Ajrak, imported from Sindh which they called Sindhin. In 500 BC, the Ajrak was also presented to Persian King Dara (first) at his crown ceremony. If we elaborate the impression of Ajrak, it is pertinent to know about its importance and use to its native and how it is made.Process of Ajrak Making

Let’s come to the unique and motivating process of Ajrak making. Motivating, because it is more than just daily work but it involves their devotion and spiritual association as Ajrak has a deep root to the Sufi culture that encompasses throughout the Sindh. That’s why we can find more Ajrak makers and their workplace near the shrines in interior Sindh.

The basic four themes used in Ajrak preparation are known as, Teli Ajrak, Sabuni Ajrak, Do Rangi Ajrak and Kori Ajrak.

Fabric Washing and Cleansing (Churrai)

There are numerous steps involved in preparation of Ajrak ranging from 18 to 19 steps but the basic process is called Churrai by local communities. Precisely, the process involves washing cloth and beating to extricate the impurities. The fabric is then soaked in a solution of a special oil and Soda Bicarbonate, which is a complicated procedure and takes several days.

Resist Printing

Next step is the printing of cloth. The real Ajrak is printed on both sides, which is called resist printing. The printing is done by hand carved wooden blocks, which are so perfectly carved so that the pattern is synchronized with the whole of the Ajrak.

Bleaching

In the end the ready Ajraks are again washed in Soda and water with bleaching powder to give brightness to the colors.

The International Fancy for the Intricate Ajrak

Besides being a domain of Sindh culture, Ajrak is profoundly used by everyone not only nationwide but internationally. Ajrak has been exhibited in national exhibitions since many years but these days the scale has been enlarged and display of Ajrak on Expo centers has increase its fame internationally. Many fashion designers are using Ajrak moderately with different ornaments like sequences and Gota work. The integration of traditional customs with contemporary one is a very unique and beautiful amalgamation.

Status of Ajrak Industry in Pakistan

Unfortunately, on the other hand the real local Ajrak industry is declined rapidly, which can be evidently noted from different researches and reports narrated that due to negligence of people, more than 30 ajrak factories have been demolished and replaced by iron steel and other industries. It occurs may be due to the unfavorable wages to the workers. Wholesalers pay very low prices to the craftsmen to keep their profit margin high, due to which no credit facilities are available to the workers resulted in decline of real Ajrak and weaning of traditional sources of livelihood.

This situation eventually leads to the replacement of original Ajrak to the quicker printing method of the copy and fake Ajrak pattern. But the trends have changed again and young generation is very eager to save its heritage and they value this treasure.

This can be seen from the celebration of Ajrak Day at individual and institutional level

http://www.houseofpakistan.com/2013/09/the-story-of-ajrak-history-and-making/

Fiza Iftikhar September 30, 2013

We all are very well aware about the benefits of Globalization. Now you must be wondering if I am distracting from the title but it is a fact that due to globalization everything has come close to each other and nothing remains confined to a specific area or culture. But the word that draws the distinctive line between this globalization is belongingness.

We may adopt the culture, inheritance or values of any nation or society but we cannot steal and snatch the foundation and identity of anyone.

Now if we take Ajrak in that context, many people still do not know about the story behind the origin of Ajrak especially our youth may be due to their occupation and the daily emerging international brands their interest has switched and may be because they can find Ajrak anywhere in Pakistan and even across Pakistan too so they may not find it important to explore the history behind it.

Etymology of the Word Ajrak

Pakistan is a blessed country with a variety of cultures in its provinces, be it a lingual aspect or attire, food or whatever.

The word Ajrak is derived from an Arabic word azrak which means blue. It is a cloth of 2.5 “ 3 meters length, decorated mostly with rich crimson and a deep indigo color but a little bit of white and black is also used to give definition to the geometric patterns. It is commonly used in Sindh as men use it as a turban and curled it around the shoulders while women use it as a shawl and sometimes as a makeshift swing for children.

Besides, Sindhis have a special feeling and association for the ajrak and they use Ajrak from cradle to grave. They also wear it without any status barrier on festive occasions like birth, marriage, and death.

History of Ajrak

Tracing the Origins

Pashtuns have their own identity, Punjab stands at its own specialty, just like that Ajrak is an essential part of the Sindhi attire but the origin of the Ajrak can be marked out from the ancient times around 2500 BC – 1500 BC when a statue of King- Priest was quarried from Mohenjo-Daro which had draped a shawl over his shoulder – adorned with a trefoil pattern (like a three leafed clover) sprinkled with small circles filled with a red color.

The trefoil signifies three sun-disks glued together to characterize the unity of the gods of the Sun, water and earth. Since the Ajrak has been used in Sindh for centuries and the block printing techniques and dyes are all ages-old methods of dying cloth but this symbol is still used on the Ajrak these days.

There are also some interesting facts about the use of Ajrak including the Egyptians. They used to clothe their mummies with Ajrak, imported from Sindh which they called Sindhin. In 500 BC, the Ajrak was also presented to Persian King Dara (first) at his crown ceremony. If we elaborate the impression of Ajrak, it is pertinent to know about its importance and use to its native and how it is made.Process of Ajrak Making

Let’s come to the unique and motivating process of Ajrak making. Motivating, because it is more than just daily work but it involves their devotion and spiritual association as Ajrak has a deep root to the Sufi culture that encompasses throughout the Sindh. That’s why we can find more Ajrak makers and their workplace near the shrines in interior Sindh.

The basic four themes used in Ajrak preparation are known as, Teli Ajrak, Sabuni Ajrak, Do Rangi Ajrak and Kori Ajrak.

Fabric Washing and Cleansing (Churrai)

There are numerous steps involved in preparation of Ajrak ranging from 18 to 19 steps but the basic process is called Churrai by local communities. Precisely, the process involves washing cloth and beating to extricate the impurities. The fabric is then soaked in a solution of a special oil and Soda Bicarbonate, which is a complicated procedure and takes several days.

Resist Printing

Next step is the printing of cloth. The real Ajrak is printed on both sides, which is called resist printing. The printing is done by hand carved wooden blocks, which are so perfectly carved so that the pattern is synchronized with the whole of the Ajrak.

Bleaching

In the end the ready Ajraks are again washed in Soda and water with bleaching powder to give brightness to the colors.

The International Fancy for the Intricate Ajrak