Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/hcn8tlf

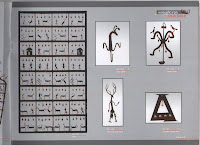

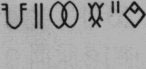

Indus Script visible language hypertexts on 12 inscriptions signifies kammaṭa 'mint' with component khambhaṛā 'fish-fin'

Running down the street to find his brother Jean-François Champollion (1790-1832) yelled "Je tiens mon affaire!" (I've got it!) but collapsed from the excitement. This note is a tribute to this exclamation and genius of Champollion.

I call Bharatam Janam, Tvaṣṭr̥ dhokra kolhe sippi, the lost-wax smelters, sculptors, metasmiths, artificers who invented a writing system of remarkable fidelity and simplicity of the cipher based on rebus method.

I call Bharatam Janam, Tvaṣṭr̥ dhokra kolhe sippi, the lost-wax smelters, sculptors, metasmiths, artificers who invented a writing system of remarkable fidelity and simplicity of the cipher based on rebus method.

Tvaṣṭr̥ is a metaphor for veneration of metalwork artificers, Bhāratam Janam, in Rigveda

Dhokra- root in: tarkhāṇ (Western Pahadi)

X Tvaṣṭr̥ (Rigveda)

ترکانړ tarkāṟṟṉ, s.m. (5th) A carpenter. Pl. ترکانړان tarkāṟṟṉān. (Panjābī).دروزګر darūz-gar, s.m. (5th) A carpenter, a joiner. Pl. دروزګران darūzgarān (corrup. of P درود گر ).(Pashto) Taccha1 [Vedic takṣan, cp. taṣṭṛ, to takṣati (see taccheti), Lat. textor, Gr. te/ktwn carpenter (cp. architect), te/xnh art] a carpenter, usually as ˚ka: otherwise only in cpd. ˚sūkara the carpenter -- pig (=a boar, so called from felling trees), title & hero of Jātaka No. 492 (iv. 342 sq.). Cp. vaḍḍhakin.1

Tacchati [fr. taccha1 , cp. taccheti] to build, construct; maggaŋ t. to construct or repair a road J vi. 348.

Taccheti [probably a denom. fr. taccha1 =Lat. texo to weave (orig. to plait, work together, work artistically), cp. Sk. taṣṭṛ architect =Lat. textor; Sk. takṣan, etc., Gr.te/xnh craft, handiwork (cp. technique), Ohg. dehsa hatchet. Cp. also orig. meaning of karoti & kamma] to do wood -- work, to square, frame, chip J i. 201; Miln 372, 383.(Pali)

துவட்டர் tuvaṭṭar , n. < tvaṣṭṛ. Artificers, smiths; சிற்பியர். (சூடா.)துவட்டா tuvaṭṭā, n. < TvaṣṭāTvaṣṭṛ. Višvakarmā, the architect of the gods; தெய்வத்தச்சனாகிய விசுவகருமா. துவட்டா வீன்ற தனயன் (திருவிளை. இந்திரன்பழி. 8).தொட்டா toṭṭā, n. < TvaṣṭāTvaṣṭṛ. One of tuvātacātittar, q.v.; துவாத சாதித்தருள் ஒருவன். நள்ளிரு ளெறிதொட்டா (கூர்மபு. ஆதவர்சிறப்.).="article" id="தொட்டாச்சி_toṭṭācci">

தொட்டாச்சி toṭṭācci, n. < தொட்ட +. ஆய்ச்சி. Godmother; ஞானத்தாய். (W .)

takṣa 5618 takṣa in cmpd. ʻ cutting ʼ, m. ʻ carpenter ʼ VarBr̥S., vṛkṣa -- takṣaka -- m. ʻ tree -- feller ʼ R. [√takṣ ] Pa. tacchaka -- m. ʻ carpenter ʼ, taccha -- sūkara -- m. ʻ boar ʼ; Pk. takkha -- , °aya -- m. ʻ carpenter, artisan ʼ; Bshk. sum -- tac̣h ʻ hoe ʼ (< ʻ *earth -- scratcher ʼ),tec̣h ʻ adze ʼ (< *takṣī -- ?); Sh. tac̣i f. ʻ adze ʼ; -- Phal. tērc̣hi ʻ adze ʼ (with "intrusive" r).takṣaṇa 5619 takṣaṇa n. ʻ cutting, paring ʼ KātyŚr. [√takṣ ]Pa. tacchanī -- f. ʻ hatchet ʼ; Pk. tacchaṇa -- n., °ṇā -- f. ʻ act of cutting or scraping ʼ; Kal. tēčin ʻ chip ʼ (< *takṣaṇī -- ?); K. tȧchyunu (dat. tȧchinis) m. ʻ wood -- shavings ʼ; Ku. gng. taċhaṇ ʻ cutting (of wood) ʼ; M. tāsṇī f. ʻ act of chipping &c., adze ʼ.Addenda: takṣaṇa -- : Pk. tacchaṇa -- n. ʻ cutting ʼ; Kmd.barg. taċə̃ři ʻ chips (on roof) ʼ GM 22.6.71.620 tákṣati (3 pl. tákṣati RV.) ʻ forms by cutting, chisels ʼ MBh. [√takṣ ]Pa. tacchati ʻ builds ʼ, tacchēti ʻ does woodwork, chips ʼ; Pk. takkhaï, tacchaï, cacchaï, caṁchaï ʻ cuts, scrapes, peels ʼ; Gy. pers. tetchkani ʻ knife ʼ, wel. tax -- ʻ to paint ʼ (?); Dm. taċ -- ʻ to cut ʼ (ċ < IE. k̂s NTS xii 128), Kal. tã̄č -- ; Kho. točhik ʻ to cut with an axe ʼ; Phal. tac̣<-> ʻ to cut, chop, whittle ʼ; Sh. (Lor.) thačoiki ʻ to fashion (wood) ʼ; K. tachun ʻ to shave, pare, scratch ʼ, S. tachaṇu; L. tachaṇ ʻ to scrape ʼ, (Ju.) ʻ to rough hew ʼ, P. tacchṇā, ludh. taccha nā ʻ to hew ʼ; Ku. tāchṇo ʻ to square out ʼ; N. tāchnu ʻ to scrape, peel, chip off ʼ (whence tachuwā ʻ chopped square ʼ, tachārnu ʻ to lop, chop ʼ); B. cã̄chā ʻ to scrape ʼ; Or. tã̄chibā, cã̄chibā,chã̄cibā ʻ to scrape off, clip, peel ʼ; Bhoj. cã̄chal ʻ to smoothe with an adze ʼ; H. cã̄chnā ʻ to scrape up ʼ; G. tāchvũ ʻ to scrape, carve, peel ʼ, M. tāsṇẽ; Si. sahinavā,ha° ʻ to cut with an adze ʼ. <-> Kho. troc̣ik ʻ to hew ʼ with "intrusive" r.

Addenda: tákṣati: Kmd. taċ -- ʻ to cut, pare, clip ʼ GM 22.6.71; A. cã̄ciba (phonet. sãsibɔ) ʻ to scrape ʼ AFD 216, 217, ʻ to smoothe with an adze ʼ 331.TAÑC: †takmán -tákṣan 5621 tákṣan (acc. tákṣaṇam RV., takṣāṇam Pāṇ.) m. ʻ carpenter ʼ. [√takṣ ] Pk. takkhāṇa -- m., Paš. ar. tac̣an -- kṓr, weg. taṣāˊn, Kal. kaṭ -- tačon, Kho. (Lor.) tačon, Sh. thac̣&oarcacute;ṇ m., kaṭ -- th°, K. chān m., chöñü f., P. takhāṇ m.,°ṇī f., H. takhān m.; Si. sasa ʻ carpenter, wheelwright ʼ < nom. tákṣā. -- With "intrusive" r: Kho. (Lor.) tračon ʻ carpenter ʼ, P. tarkhāṇ m. (→ H. tarkhān m.), WPah. jaun. tarkhāṇ. -- With unexpl. d -- or dh -- (X dāˊru -- ?): S. ḍrakhaṇu m. ʻ carpenter ʼ; L. drakhāṇ, (Ju.) darkhāṇ m. ʻ carpenter ʼ (darkhāṇ pakkhī m. ʻ woodpecker ʼ), mult. dhrikkhāṇ m.,

dhrikkhaṇī f., awāṇ. dhirkhāṇ m.

Dhokra- root in: tarkhāṇ (Western Pahadi)

X Tvaṣṭr̥ (Rigveda)

Tacchati [fr. taccha

Taccheti [probably a denom. fr. taccha1 =Lat. texo to weave (orig. to plait, work together, work artistically), cp. Sk. taṣṭṛ architect =Lat. textor; Sk. takṣan, etc., Gr.te/xnh craft, handiwork (cp. technique), Ohg. dehsa hatchet. Cp. also orig. meaning of karoti & kamma] to do wood -- work, to square, frame, chip J i. 201; Miln 372, 383.(Pali)

துவட்டர் tuvaṭṭar , n. < tvaṣṭṛ. Artificers, smiths; சிற்பியர். (சூடா.)துவட்டா tuvaṭṭā, n. < TvaṣṭāTvaṣṭṛ. Višvakarmā, the architect of the gods; தெய்வத்தச்சனாகிய விசுவகருமா. துவட்டா வீன்ற தனயன் (திருவிளை. இந்திரன்பழி. 8).தொட்டா toṭṭā, n. < TvaṣṭāTvaṣṭṛ. One of tuvātacātittar, q.v.; துவாத சாதித்தருள் ஒருவன். நள்ளிரு ளெறிதொட்டா (கூர்மபு. ஆதவர்சிறப்.).="article" id="தொட்டாச்சி_toṭṭācci">

தொட்டாச்சி toṭṭācci, n. < தொட்ட +. ஆய்ச்சி. Godmother; ஞானத்தாய். (W .)

தொட்டாச்சி toṭṭācci, n. < தொட்ட +. ஆய்ச்சி. Godmother; ஞானத்தாய். (

Addenda: tákṣati: Kmd. taċ -- ʻ to cut, pare, clip ʼ GM 22.6.71; A. cã̄ciba (phonet. sãsibɔ) ʻ to scrape ʼ AFD 216, 217, ʻ to smoothe with an adze ʼ 331.TAÑC: †

What language did they speak?

A Prakritam gloss with phonetic variants provides the lead: kamad.ha, kamat.ha,

kamad.haka, kamad.haga, kamad.haya= a type of penance is recognized in sets of hieroglyph-multiplexes on ten inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora. These inscriptions and decipherment are presented.

(Haragovindadāsa Trikamacanda Seṭha, 1963,Prakrit-Sanskrit-Hindi dictionary, Motilal Banarsidass, Dehi,p.223)

kamad.haka, kamad.haga, kamad.haya= a type of penance is recognized in sets of hieroglyph-multiplexes on ten inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora. These inscriptions and decipherment are presented.

(Haragovindadāsa Trikamacanda Seṭha, 1963,Prakrit-Sanskrit-Hindi dictionary, Motilal Banarsidass, Dehi,p.223)

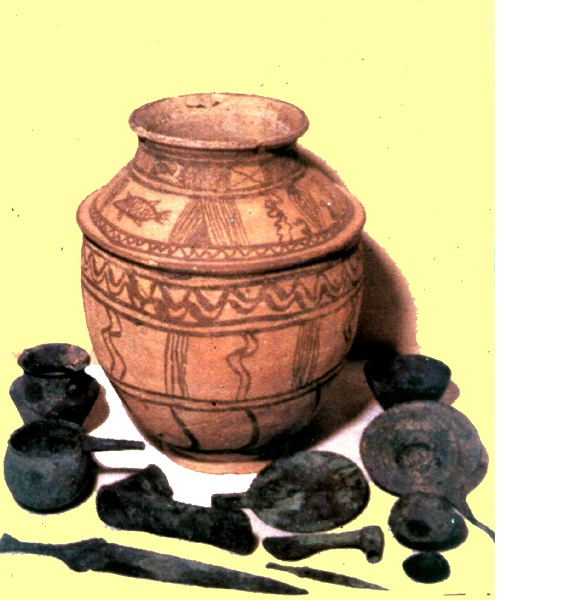

Proto-Elamite seal impressions, Susa. Seated bulls in penance posture. (After Amiet 1980: nos. 581, 582).Hieroglyph: kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) Rebus: kammaTTa 'coiner, mint'Hieroglyph: dhanga 'mountain range' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'

Hieroglyph: rango 'buffalo' Rebus: rango 'pewter'Ganweriwala tablet. Ganeriwala or Ganweriwala (Urdu: گنےریوالا Punjabi: گنیریوالا) is a Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization site in Cholistan, Punjab, Pakistan.

gumat.a, gumut.a, gumuri, gummat.a, gummut.a a copula or dome (Ka.); ghumat.a (M.); gummat.a, gummad a dome; a paper lantern; a fire-baloon (H.Te.); kummat.t.a arch, vault, arched roof, pinnacle of a pagoda; globe, lantern made of paper (Ta.)(Ka.lex.); gummaṭ m. ‘dome’ (P.) CDIAL 4217Other glyphs (glyphemes): gúlma— m. ‘clump of trees’ VS., gumba— m. ‘cluster, thicket’ (Pali); gumma— m.n. ‘thicket’ (Pkt.); S. gūmbaṭu m. ‘bullock’s hump’; gumbaṭ m., gummaṭ f. ‘bullock’s hump’ (L.) CDIAL 4217rebus: kumpat.i = ban:gala = an:ga_ra s’akat.i_ = a chafing dish, a portable stove, a goldsmith’s portable furnace (Te.lex.) kumpiṭu-caṭṭichafing-dish, port- able furnace, potsherd in which fire is kept by goldsmiths; kumutam oven, stove; kummaṭṭi chafing-dish (Ta.).kuppaḍige, kuppaṭe, kum- paṭe, kummaṭa, kummaṭe id. (Ka.)kumpaṭi id. (Te.) DEDR 1751. kummu smouldering ashes (Te.); kumpōḍsmoke.(Go) DEDR 1752.

Glyphs on a broken molded tablet, Ganweriwala. The reverse includes the 'rim-of-jar' glyph in a 3-glyph text. Observe shows a person seated on a stool and a kneeling adorant below.

Hieroglyph: kamadha '

1. kuṭila ‘bent’; rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) [cf. āra-kūṭa, ‘brass’ (Skt.) (CDIAL 3230)

2. Glyph of ‘rim of jar’: kárṇaka m. ʻ projection on the side of a vessel, handle ʼ ŚBr. [kárṇa -- ]Pa. kaṇṇaka -- ʻ having ears or corners ʼ; (CDIAL 2831) kaṇḍa kanka; Rebus: furnace account (scribe). kaṇḍ = fire-altar (Santali); kan = copper (Tamil) khanaka m. one who digs , digger , excavator Rebus: karanikamu. Clerkship: the office of a Karanam or clerk. (Telugu) káraṇa n. ʻ act, deed ʼ RV. [√kr̥1] Pa. karaṇa -- n. ʻdoingʼ; NiDoc. karana, kaṁraṁna ʻworkʼ; Pk. karaṇa -- n. ʻinstrumentʼ(CDIAL 2790)

3. khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ‘ turner’ (G.)

Hieroglyph: मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ 'iron, copper' (Munda. Slavic) mẽṛhẽt, meD 'iron' (Mu.Ho.Santali)meď 'copper' (Slovak)

Mohenjo-daro. Sealing. Surrounded by fishes, lizard and snakes, a horned person sits in 'yoga' on a throne with hoofed legs. One side of a triangular terracotta amulet (Md 013); surface find at Mohenjo-daro in 1936, Dept. of Eastern Art, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. [seated person penance, crocodile?] Brief memoranda: kamaḍha ‘penance’ Rebus: kammaṭa ‘mint, coiner’; kaṇḍo ‘stool, seat’ Rebus: kāṇḍa ‘metalware’ kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar’.kAru 'crocodile' Rebus: kAru 'artisan'.

Hieroglyphs (allographs): kamaḍha 'penance' (Prakriam) kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali)

Glyph: meD 'to dance' (F.)[reduplicated from me-]; me id. (M.) in Remo (Munda)(Source: D. Stampe's Munda etyma) meṭṭu to tread, trample, crush under foot, tread or place the foot upon (Te.); meṭṭu step (Ga.); mettunga steps (Ga.). maḍye to trample, tread (Malt.)(DEDR 5057) మెట్టు (p. 1027) [ meṭṭu ] meṭṭu. [Tel.] v. a. &n. To step, walk, tread. అడుగుపెట్టు, నడుచు, త్రొక్కు . "మెల్ల మెల్లన మెట్టుచుదొలగి అల్లనల్లనతలుపులండకు జేరి ." BD iv. 1523. To tread on, to trample on. To kick, to thrust with the foot.మెట్టిక meṭṭika. n. A step , మెట్టు, సోపానము (Telugu) Rebus: meD 'iron' (Mundari. Remo.)

![clip_image026]() Slide 207 Tablet with inscription. Twisted terra cotta tablet (H2000-4441/2102-464) with a mold-made inscription and narrative motif from the Trench 54 area. In the center is the depiction of what is possibly a deity with a horned headdress in so-called yogic position seated on a stool under an arch.Harappa. Two tablets. Seated figure or deity with reed house or shrine at one side. Left: H95-2524; Right: H95-2487.Harappa. Planoconvex molded tablet found on Mound ET. A. Reverse. a female deity battling two tigers and standing above an elephant and below a six-spoked wheel; b. Obverse. A person spearing with a barbed spear a buffalo in front of a seated horned deity wearing bangles and with a plumed headdress. The person presses his foot down the buffalo’s head. An alligator with a narrow snout is on the top register. “We have found two other broken tablets at Harappa that appear to have been made from the same mold that was used to create the scene of a deity battling two tigers and standing above an elephant. One was found in a room located on the southern slope of Mount ET in 1996 and another example comes from excavations on Mound F in the 1930s. However, the flat obverse of both of these broken tablets does not show the spearing of a buffalo, rather it depicts the more well-known scene showing a tiger looking back over its shoulder at a person sitting on the branch of a tree. Several other flat or twisted rectangular terracotta tablets found at Harappa combine these two narrative scenes of a figure strangling two tigers on one side of a tablet, and the tiger looking back over its shoulder at a figure in a tree on the other side.” [JM Kenoyer, 1998, p. 115].

Slide 207 Tablet with inscription. Twisted terra cotta tablet (H2000-4441/2102-464) with a mold-made inscription and narrative motif from the Trench 54 area. In the center is the depiction of what is possibly a deity with a horned headdress in so-called yogic position seated on a stool under an arch.Harappa. Two tablets. Seated figure or deity with reed house or shrine at one side. Left: H95-2524; Right: H95-2487.Harappa. Planoconvex molded tablet found on Mound ET. A. Reverse. a female deity battling two tigers and standing above an elephant and below a six-spoked wheel; b. Obverse. A person spearing with a barbed spear a buffalo in front of a seated horned deity wearing bangles and with a plumed headdress. The person presses his foot down the buffalo’s head. An alligator with a narrow snout is on the top register. “We have found two other broken tablets at Harappa that appear to have been made from the same mold that was used to create the scene of a deity battling two tigers and standing above an elephant. One was found in a room located on the southern slope of Mount ET in 1996 and another example comes from excavations on Mound F in the 1930s. However, the flat obverse of both of these broken tablets does not show the spearing of a buffalo, rather it depicts the more well-known scene showing a tiger looking back over its shoulder at a person sitting on the branch of a tree. Several other flat or twisted rectangular terracotta tablets found at Harappa combine these two narrative scenes of a figure strangling two tigers on one side of a tablet, and the tiger looking back over its shoulder at a figure in a tree on the other side.” [JM Kenoyer, 1998, p. 115].![]() m1181A

m1181A![clip_image012]() 2222 Pict-80: Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown), wearing bangles and armlets and seated, in a yogic posture, on a hoofed platformMohenjo-daro. Square seal depicting a nude male deity with three faces, seated in yogic position on a throne, wearing bangles on both arms and an elaborate headdress. Five symbols of the Indus script appear on either side of the headdress which is made of two outward projecting buffalo style curved horns, with two upward projecting points. A single branch with three pipal leaves rises from the middle of the headdress. Seven bangles are depicted on the left arm and six on the right, with the hands resting on the knees. The heels are pressed together under the groin and the feet project beyond the edge of the throne. The feet of the throne are carved with the hoof of a bovine as is seen on the bull and unicorn seals. The seal may not have been fired, but the stone is very hard. A grooved and perforated boss is present on the back of the seal.

2222 Pict-80: Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown), wearing bangles and armlets and seated, in a yogic posture, on a hoofed platformMohenjo-daro. Square seal depicting a nude male deity with three faces, seated in yogic position on a throne, wearing bangles on both arms and an elaborate headdress. Five symbols of the Indus script appear on either side of the headdress which is made of two outward projecting buffalo style curved horns, with two upward projecting points. A single branch with three pipal leaves rises from the middle of the headdress. Seven bangles are depicted on the left arm and six on the right, with the hands resting on the knees. The heels are pressed together under the groin and the feet project beyond the edge of the throne. The feet of the throne are carved with the hoof of a bovine as is seen on the bull and unicorn seals. The seal may not have been fired, but the stone is very hard. A grooved and perforated boss is present on the back of the seal.

Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050

Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.296 Mackay 1938: 335, pl. LXXXVII, 222 Hieroglyph: kamaḍha ‘penance’ (Pkt.) Rebus 1: kampaṭṭa ‘mint’ (Ma.) kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.);Rebus 2: kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar' (Santali); kan ‘copper’ (Ta.)

Hieroglyph: karã̄ n. pl. ʻwristlets, bangles ʼ (Gujarati); kara 'hand' (Rigveda) Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) The bunch of twigs = ku_di_, ku_t.i_ (Skt.lex.) ku_di_ (also written as ku_t.i_ in manuscripts) occurs in the Atharvaveda (AV 5.19.12) and Kaus’ika Su_tra (Bloomsfield’s ed.n, xliv. cf. Bloomsfield, American Journal of Philology, 11, 355; 12,416; Roth, Festgruss an Bohtlingk,98) denotes it as a twig. This is identified as that of Badari_, the jujube tied to the body of the dead to efface their traces. (See Vedic Index, I, p. 177).[Note the twig adoring the head-dress of a horned, standing person]

Horned deity seals, Mohenjo-daro: a. horned deity with pipal-leaf headdress, Mohenjo-daro (DK12050, NMP 50.296) (Courtesy of the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan); b. horned deity with star motifs, Mohenjo-daro (M-305) (PARPOLA 1994:Fig. 10.9); courtesy of the Archaeological Survey of India; c. horned deity surrounded by animals, Mohenjo-daro (JOSHI – PARPOLA 1987:M-304); courtesy of the Archaeological Survey of India.

![clip_image006]() m0305AC

m0305AC ![clip_image008]() 2235 Pict-80: Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown with two stars on either side), wearing bangles and armlets. Two stars adorn the curved buffalo horns of the seated person with a plaited pigtail. The pigtail connotes a pit furnace:Glyph: kamad.ha, kamat.ha, kamad.haka, kamad.haga, kamad.haya = a type of penance (Pkt.lex.)

2235 Pict-80: Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown with two stars on either side), wearing bangles and armlets. Two stars adorn the curved buffalo horns of the seated person with a plaited pigtail. The pigtail connotes a pit furnace:Glyph: kamad.ha, kamat.ha, kamad.haka, kamad.haga, kamad.haya = a type of penance (Pkt.lex.)

kamat.amu, kammat.amu = a portable furnace for melting precious metals; kammat.i_d.u = a goldsmith, a silversmith (Te.lex.) ka~pr.aut.,kapr.aut. jeweller’s crucible made of rags and clay (Bi.); kapr.aut.i_wrapping in cloth with wet clay for firing chemicals or drugs, mud cement (H.)[cf. modern compounds: kapar.mit.t.i_ wrapping in cloth and clay (H.);kapad.lep id. (H.)](CDIAL 2874). kapar-mat.t.i clay and cowdung smeared on a crucible (N.)(CDIAL 2871).

kampat.t.tam coinage, coin (Ta.); kammat.t.am, kammit.t.am coinage, mint (Ma.); kammat.i a coiner (Ka.)(DEDR 1236) kammat.a = coinage, mint (Ka.M.) kampat.t.a-k-ku_t.am mint; kampat.t.a-k-ka_ran- coiner; kampat.t.a- mul.ai die, coining stamp (Ta.lex.)

Seated person in penance. Wears a scarf as pigtail and curved horns with embedded stars and a twig.

mēḍha The polar star. (Marathi) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); Rebus: dul ‘cast (metal)’(Santali) ḍabe, ḍabea ‘large horns, with a sweeping upward curve, applied to buffaloes’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’, clot, make a lump or clot, coagulate, fuse, melt together (Santali) kūtī = bunch of twigs (Skt.) Rebus: kuṭhi = (smelter) furnace (Santali) The narrative on this metalware catalog is thus: (smelter) furnace for iron and for fusing together cast metal. kamaḍha ‘penance’.Rebus 1: kaṇḍ ‘stone (ore) metal’.Rebus 2: kampaṭṭa‘mint’.

ṭhaṭera 'buffalo horns'. Rebus: ṭhaṭerā 'brass worker'kamadha '

Text on obverse of the tablet m453A: Text 1629. m453BC Seated in penance, the person is flanked on either side by a kneeling adorant, offering a pot and a hooded serpent rearing up.

Glyph: kaṇḍo ‘stool’. Rebus; kaṇḍ ‘furnace’. Vikalpa: kaṇḍ ‘stone (ore) metal’. Rebus: kamaḍha ‘penance’. Rebus 1: kaṇḍ ‘stone ore’. Rebus 2: kampaṭṭa ‘mint’. Glyph: ‘serpent hood’: paṭa. Rebus: pata ‘sharpness (of knife), tempered (metal). padm ‘tempered iron’ (Ko.) kulA 'hood of serpent' Rebus: kolle 'blacksmith'.

Glyph: rimless pot: baṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘smelter, furnace’. It appears that the message of the glyphics is about a mint or metal workshop which produces sharpened, tempered iron (stone ore) using a furnace.

Rebus readings of glyphs on text of inscription:

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu. Kōḍi corner; kōṇṭu angle, corner, crook. Nk. Kōnṭa corner (DEDR 2054b) G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼRebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295)

aṭar ‘a splinter’ (Ma.) aṭaruka ‘to burst, crack, sli off,fly open; aṭarcca ’ splitting, a crack’; aṭarttuka ‘to split, tear off, open (an oyster) (Ma.); aḍaruni ‘to crack’ (Tu.) (DEDR 66) Rebus: aduru ‘native, unsmelted metal’ (Kannada)

ãs = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya ‘metal, iron’ (Gujarati.) cf. cognate to amśu 'soma' in Rigveda: ancu 'iron' (Tocharian)G.karã̄ n. pl. ‘wristlets, bangles’; S. karāī f. ’wrist’ (CDIAL 2779). Rebus: khār खार् ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri)

dula ‘pair’; rebus dul ‘cast (metal)’

Glyph of ‘rim of jar’: kárṇaka m. ʻ projection on the side of a vessel, handle ʼ ŚBr. [kárṇa -- ]Pa. kaṇṇaka -- ʻ having ears or corners ʼ; (CDIAL 2831) kaṇḍa kanka; Rebus: furnace account (scribe). kaṇḍ = fire-altar (Santali); kan = copper (Tamil) khanaka m. one who digs , digger , excavator Rebus: karanikamu. Clerkship: the office of a Karanam or clerk. (Telugu) káraṇa n. ʻ act, deed ʼ RV. [√kr̥1] Pa. karaṇa -- n. ʻdoingʼ; NiDoc. karana, kaṁraṁna ʻworkʼ; Pk. karaṇa -- n. ʻinstrumentʼ(CDIAL 2790)

The suggested rebus readings indicate that the Indus writing served the purpose of artisans/traders to create metalware, stoneware, mineral catalogs -- products with which they carried on their life-activities in an evolving Bronze Age.

m453B. Scarf as pigtail of seated person.Kneeling adorant and serpent on the field.

khaṇḍiyo [cf. khaṇḍaṇī a tribute] tributary; paying a tribute to a superior king (Gujarti) Rebus 1: khaṇḍaran, khaṇḍrun ‘pit furnace’ (Santali) Rebus 2: khaNDa 'metal implements'![]() Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.

paṭa. 'serpent hood' Rebus: pata ‘sharpness (of knife), tempered (metal). padm ‘tempered iron’ (Kota) kulA 'hood of serpent' Rebus: kolle 'blacksmith'.

Proto-Elamite seal impressions, Susa. Seated bulls in penance posture. (After Amiet 1980: nos. 581, 582).

Hieroglyph: kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) Rebus: kammaTTa 'coiner, mint'

Hieroglyph: dhanga 'mountain range' Rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith'

Hieroglyph: rango 'buffalo' Rebus: rango 'pewter'

Hieroglyph: rango 'buffalo' Rebus: rango 'pewter'

Ganweriwala tablet. Ganeriwala or Ganweriwala (Urdu: گنےریوالا Punjabi: گنیریوالا) is a Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization site in Cholistan, Punjab, Pakistan.

gumat.a, gumut.a, gumuri, gummat.a, gummut.a a copula or dome (Ka.); ghumat.a (M.); gummat.a, gummad a dome; a paper lantern; a fire-baloon (H.Te.); kummat.t.a arch, vault, arched roof, pinnacle of a pagoda; globe, lantern made of paper (Ta.)(Ka.lex.); gummaṭ m. ‘dome’ (P.) CDIAL 4217

Other glyphs (glyphemes): gúlma— m. ‘clump of trees’ VS., gumba— m. ‘cluster, thicket’ (Pali); gumma— m.n. ‘thicket’ (Pkt.); S. gūmbaṭu m. ‘bullock’s hump’; gumbaṭ m., gummaṭ f. ‘bullock’s hump’ (L.) CDIAL 4217

rebus: kumpat.i = ban:gala = an:ga_ra s’akat.i_ = a chafing dish, a portable stove, a goldsmith’s portable furnace (Te.lex.) kumpiṭu-caṭṭichafing-dish, port- able furnace, potsherd in which fire is kept by goldsmiths; kumutam oven, stove; kummaṭṭi chafing-dish (Ta.).kuppaḍige, kuppaṭe, kum- paṭe, kummaṭa, kummaṭe id. (Ka.)kumpaṭi id. (Te.) DEDR 1751. kummu smouldering ashes (Te.); kumpōḍsmoke.(Go) DEDR 1752.

Glyphs on a broken molded tablet, Ganweriwala. The reverse includes the 'rim-of-jar' glyph in a 3-glyph text. Observe shows a person seated on a stool and a kneeling adorant below.

Hieroglyph: kamadha '

Reading rebus three glyphs of text on Ganweriwala tablet: brass-worker, scribe, turner:

1. kuṭila ‘bent’; rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) [cf. āra-kūṭa, ‘brass’ (Skt.) (CDIAL 3230)

2. Glyph of ‘rim of jar’: kárṇaka m. ʻ projection on the side of a vessel, handle ʼ ŚBr. [kárṇa -- ]Pa. kaṇṇaka -- ʻ having ears or corners ʼ; (CDIAL 2831) kaṇḍa kanka; Rebus: furnace account (scribe). kaṇḍ = fire-altar (Santali); kan = copper (Tamil) khanaka m. one who digs , digger , excavator Rebus: karanikamu. Clerkship: the office of a Karanam or clerk. (Telugu) káraṇa n. ʻ act, deed ʼ RV. [√kr̥1] Pa. karaṇa -- n. ʻdoingʼ; NiDoc. karana, kaṁraṁna ʻworkʼ; Pk. karaṇa -- n. ʻinstrumentʼ(CDIAL 2790)

3. khareḍo = a currycomb (G.) Rebus: kharādī ‘ turner’ (G.)

Hieroglyph: मेढा [mēḍhā] A twist or tangle arising in thread or cord, a curl or snarl (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ 'iron, copper' (Munda. Slavic) mẽṛhẽt, meD 'iron' (Mu.Ho.Santali)

meď 'copper' (Slovak)

Mohenjo-daro. Sealing. Surrounded by fishes, lizard and snakes, a horned person sits in 'yoga' on a throne with hoofed legs. One side of a triangular terracotta amulet (Md 013); surface find at Mohenjo-daro in 1936, Dept. of Eastern Art, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford. [seated person penance, crocodile?] Brief memoranda: kamaḍha ‘penance’ Rebus: kammaṭa ‘mint, coiner’; kaṇḍo ‘stool, seat’ Rebus: kāṇḍa ‘metalware’ kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar’.

Hieroglyphs (allographs):

kamaḍha 'penance' (Prakriam)

kamḍa, khamḍa 'copulation' (Santali)

kamaṭha crab (Skt.)

kamaṛkom = fig leaf (Santali.lex.) kamarmaṛā (Has.), kamaṛkom (Nag.); the petiole or stalk of a leaf (Mundari.lex.) kamat.ha = fig leaf, religiosa (Sanskrit)

kamāṭhiyo = archer; kāmaṭhum = a bow; kāmaḍ, kāmaḍum = a chip of bamboo (G.) kāmaṭhiyo a bowman; an archer (Sanskrit)

Rebus: kammaṭi a coiner (Ka.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Ta.) kammaṭa = mint, gold furnace (Te.) kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Telugu); kampaṭṭam = mint (Tamil)

Glyph: meD 'to dance' (F.)[reduplicated from me-]; me id. (M.) in Remo (Munda)(Source: D. Stampe's Munda etyma) meṭṭu to tread, trample, crush under foot, tread or place the foot upon (Te.); meṭṭu step (Ga.); mettunga steps (Ga.). maḍye to trample, tread (Malt.)(DEDR 5057) మెట్టు (p. 1027) [ meṭṭu ] meṭṭu. [Tel.] v. a. &n. To step, walk, tread. అడుగుపెట్టు, నడుచు, త్రొక్కు . "మెల్ల మెల్లన మెట్టుచుదొలగి అల్లనల్లనతలుపులండకు జేరి ." BD iv. 1523. To tread on, to trample on. To kick, to thrust with the foot.మెట్టిక meṭṭika. n. A step , మెట్టు, సోపానము (Telugu)

Harappa. Two tablets. Seated figure or deity with reed house or shrine at one side. Left: H95-2524; Right: H95-2487.

Harappa. Planoconvex molded tablet found on Mound ET. A. Reverse. a female deity battling two tigers and standing above an elephant and below a six-spoked wheel; b. Obverse. A person spearing with a barbed spear a buffalo in front of a seated horned deity wearing bangles and with a plumed headdress. The person presses his foot down the buffalo’s head. An alligator with a narrow snout is on the top register. “We have found two other broken tablets at Harappa that appear to have been made from the same mold that was used to create the scene of a deity battling two tigers and standing above an elephant. One was found in a room located on the southern slope of Mount ET in 1996 and another example comes from excavations on Mound F in the 1930s. However, the flat obverse of both of these broken tablets does not show the spearing of a buffalo, rather it depicts the more well-known scene showing a tiger looking back over its shoulder at a person sitting on the branch of a tree. Several other flat or twisted rectangular terracotta tablets found at Harappa combine these two narrative scenes of a figure strangling two tigers on one side of a tablet, and the tiger looking back over its shoulder at a figure in a tree on the other side.” [JM Kenoyer, 1998, p. 115].

m1181A![clip_image012]() 2222 Pict-80: Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown), wearing bangles and armlets and seated, in a yogic posture, on a hoofed platform

2222 Pict-80: Three-faced, horned person (with a three-leaved pipal branch on the crown), wearing bangles and armlets and seated, in a yogic posture, on a hoofed platform

Mohenjo-daro. Square seal depicting a nude male deity with three faces, seated in yogic position on a throne, wearing bangles on both arms and an elaborate headdress. Five symbols of the Indus script appear on either side of the headdress which is made of two outward projecting buffalo style curved horns, with two upward projecting points. A single branch with three pipal leaves rises from the middle of the headdress.

Seven bangles are depicted on the left arm and six on the right, with the hands resting on the knees. The heels are pressed together under the groin and the feet project beyond the edge of the throne. The feet of the throne are carved with the hoof of a bovine as is seen on the bull and unicorn seals. The seal may not have been fired, but the stone is very hard. A grooved and perforated boss is present on the back of the seal.

Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050

Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.296 Mackay 1938: 335, pl. LXXXVII, 222

Material: tan steatite Dimensions: 2.65 x 2.7 cm, 0.83 to 0.86 thickness Mohenjo-daro, DK 12050

Islamabad Museum, NMP 50.296 Mackay 1938: 335, pl. LXXXVII, 222

Hieroglyph: kamaḍha ‘penance’ (Pkt.) Rebus 1: kampaṭṭa ‘mint’ (Ma.) kamaṭa = portable furnace for melting precious metals (Te.);Rebus 2: kaṇḍa ‘fire-altar' (Santali); kan ‘copper’ (Ta.)

Hieroglyph: karã̄ n. pl. ʻwristlets, bangles ʼ (Gujarati); kara 'hand' (Rigveda) Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

The bunch of twigs = ku_di_, ku_t.i_ (Skt.lex.) ku_di_ (also written as ku_t.i_ in manuscripts) occurs in the Atharvaveda (AV 5.19.12) and Kaus’ika Su_tra (Bloomsfield’s ed.n, xliv. cf. Bloomsfield, American Journal of Philology, 11, 355; 12,416; Roth, Festgruss an Bohtlingk,98) denotes it as a twig. This is identified as that of Badari_, the jujube tied to the body of the dead to efface their traces. (See Vedic Index, I, p. 177).[Note the twig adoring the head-dress of a horned, standing person]

Horned deity seals, Mohenjo-daro: a. horned deity with pipal-leaf headdress, Mohenjo-daro (DK12050, NMP 50.296) (Courtesy of the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan); b. horned deity with star motifs, Mohenjo-daro (M-305) (PARPOLA 1994:Fig. 10.9); courtesy of the Archaeological Survey of India; c. horned deity surrounded by animals, Mohenjo-daro (JOSHI – PARPOLA 1987:M-304); courtesy of the Archaeological Survey of India.

Glyph: kamad.ha, kamat.ha, kamad.haka, kamad.haga, kamad.haya = a type of penance (Pkt.lex.)

kamat.amu, kammat.amu = a portable furnace for melting precious metals; kammat.i_d.u = a goldsmith, a silversmith (Te.lex.) ka~pr.aut.,kapr.aut. jeweller’s crucible made of rags and clay (Bi.); kapr.aut.i_wrapping in cloth with wet clay for firing chemicals or drugs, mud cement (H.)[cf. modern compounds: kapar.mit.t.i_ wrapping in cloth and clay (H.);kapad.lep id. (H.)](CDIAL 2874). kapar-mat.t.i clay and cowdung smeared on a crucible (N.)(CDIAL 2871).

kampat.t.tam coinage, coin (Ta.); kammat.t.am, kammit.t.am coinage, mint (Ma.); kammat.i a coiner (Ka.)(DEDR 1236) kammat.a = coinage, mint (Ka.M.) kampat.t.a-k-ku_t.am mint; kampat.t.a-k-ka_ran- coiner; kampat.t.a- mul.ai die, coining stamp (Ta.lex.)

Seated person in penance. Wears a scarf as pigtail and curved horns with embedded stars and a twig.

mēḍha The polar star. (Marathi) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); Rebus: dul ‘cast (metal)’(Santali) ḍabe, ḍabea ‘large horns, with a sweeping upward curve, applied to buffaloes’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’, clot, make a lump or clot, coagulate, fuse, melt together (Santali) kūtī = bunch of twigs (Skt.) Rebus: kuṭhi = (smelter) furnace (Santali) The narrative on this metalware catalog is thus: (smelter) furnace for iron and for fusing together cast metal. kamaḍha ‘penance’.Rebus 1: kaṇḍ ‘stone (ore) metal’.Rebus 2: kampaṭṭa‘mint’.

mēḍha The polar star. (Marathi) Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); Rebus: dul ‘cast (metal)’(Santali) ḍabe, ḍabea ‘large horns, with a sweeping upward curve, applied to buffaloes’ (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo ‘lump (ingot?)’, clot, make a lump or clot, coagulate, fuse, melt together (Santali) kūtī = bunch of twigs (Skt.) Rebus: kuṭhi = (smelter) furnace (Santali) The narrative on this metalware catalog is thus: (smelter) furnace for iron and for fusing together cast metal. kamaḍha ‘penance’.Rebus 1: kaṇḍ ‘stone (ore) metal’.Rebus 2: kampaṭṭa‘mint’.

ṭhaṭera 'buffalo horns'. Rebus: ṭhaṭerā 'brass worker'

kamadha '

karã̄ n. pl. wristlets, banglesRebus: khAr 'blacksmith, iron worker'

rango 'buffalo' Rebus:rango 'pewter'

kari 'elephant' ibha 'elephant' Rebus: karba 'iron' ib 'iron'

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'

gaNDA 'rhinoceros' Rebus: kaNDa 'im;lements'

mlekh 'antelope, goat' Rebus: milakkha 'copper'

meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron''copper'

dhatu 'scarf' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral

Text on obverse of the tablet m453A: Text 1629. m453BC Seated in penance, the person is flanked on either side by a kneeling adorant, offering a pot and a hooded serpent rearing up.

Glyph: kaṇḍo ‘stool’. Rebus; kaṇḍ ‘furnace’. Vikalpa: kaṇḍ ‘stone (ore) metal’. Rebus: kamaḍha ‘penance’. Rebus 1: kaṇḍ ‘stone ore’. Rebus 2: kampaṭṭa ‘mint’. Glyph: ‘serpent hood’: paṭa. Rebus: pata ‘sharpness (of knife), tempered (metal). padm ‘tempered iron’ (Ko.) kulA 'hood of serpent' Rebus: kolle 'blacksmith'.

Glyph: rimless pot: baṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘smelter, furnace’. It appears that the message of the glyphics is about a mint or metal workshop which produces sharpened, tempered iron (stone ore) using a furnace.

Rebus readings of glyphs on text of inscription:

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu. Kōḍi corner; kōṇṭu angle, corner, crook. Nk. Kōnṭa corner (DEDR 2054b) G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼRebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295)

aṭar ‘a splinter’ (Ma.) aṭaruka ‘to burst, crack, sli off,fly open; aṭarcca ’ splitting, a crack’; aṭarttuka ‘to split, tear off, open (an oyster) (Ma.); aḍaruni ‘to crack’ (Tu.) (DEDR 66) Rebus: aduru ‘native, unsmelted metal’ (Kannada)

ãs = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya ‘metal, iron’ (Gujarati.) cf. cognate to amśu 'soma' in Rigveda: ancu 'iron' (Tocharian)

Rebus readings of glyphs on text of inscription:

koṇḍa bend (Ko.); Tu. Kōḍi corner; kōṇṭu angle, corner, crook. Nk. Kōnṭa corner (DEDR 2054b) G. khū̃ṭṛī f. ʻangleʼRebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’(B.) कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) koḍ ‘artisan’s workshop’ (Kuwi) koḍ = place where artisans work (G.) ācāri koṭṭya ‘smithy’ (Tu.) कोंडण [kōṇḍaṇa] f A fold or pen. (Marathi) B. kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; Or.kū̆nda ‘lathe’, kũdibā, kū̃d ‘to turn’ (→ Drav. Kur. Kū̃d ’ lathe’) (CDIAL 3295)

aṭar ‘a splinter’ (Ma.) aṭaruka ‘to burst, crack, sli off,fly open; aṭarcca ’ splitting, a crack’; aṭarttuka ‘to split, tear off, open (an oyster) (Ma.); aḍaruni ‘to crack’ (Tu.) (DEDR 66) Rebus: aduru ‘native, unsmelted metal’ (Kannada)

ãs = scales of fish (Santali); rebus: aya ‘metal, iron’ (Gujarati.) cf. cognate to amśu 'soma' in Rigveda: ancu 'iron' (Tocharian)

G.karã̄ n. pl. ‘wristlets, bangles’; S. karāī f. ’wrist’ (CDIAL 2779). Rebus: khār खार् ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri)

dula ‘pair’; rebus dul ‘cast (metal)’

Glyph of ‘rim of jar’: kárṇaka m. ʻ projection on the side of a vessel, handle ʼ ŚBr. [kárṇa -- ]Pa. kaṇṇaka -- ʻ having ears or corners ʼ; (CDIAL 2831) kaṇḍa kanka; Rebus: furnace account (scribe). kaṇḍ = fire-altar (Santali); kan = copper (Tamil) khanaka m. one who digs , digger , excavator Rebus: karanikamu. Clerkship: the office of a Karanam or clerk. (Telugu) káraṇa n. ʻ act, deed ʼ RV. [√kr̥1] Pa. karaṇa -- n. ʻdoingʼ; NiDoc. karana, kaṁraṁna ʻworkʼ; Pk. karaṇa -- n. ʻinstrumentʼ(CDIAL 2790)

The suggested rebus readings indicate that the Indus writing served the purpose of artisans/traders to create metalware, stoneware, mineral catalogs -- products with which they carried on their life-activities in an evolving Bronze Age.

khaṇḍiyo [cf. khaṇḍaṇī a tribute] tributary; paying a tribute to a superior king (Gujarti) Rebus 1: khaṇḍaran, khaṇḍrun ‘pit furnace’ (Santali) Rebus 2: khaNDa 'metal implements'

Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.paṭa. 'serpent hood' Rebus: pata ‘sharpness (of knife), tempered (metal). padm ‘tempered iron’ (Kota) kulA 'hood of serpent' Rebus: kolle 'blacksmith'.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/06/ancient-near-east-scarf-hieroglyph-on.html

What is writing? Mlecchita vikalpa of ancient Indian tradition of bhāratam janam is Indus Script writing.

What is writing? Let us define what writing is NOT.

Writing is not doodle.

Writing is not scribble even if they may have constituted 'potters' marks' comparable to trade marks or road signs.

So, writing is an alternative representation to communicate language or thought. In the context of ancient Indian tradition, one such alternative is called mlecchita vikalpa, 'Meluhha cipher writing' -- identified as one of 64 arts to be learned by youth.

![Image result for indus script sign bird fish parenthesis]() Mohenjodro 0304 seal impression http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/hieroglyph-multiplex-ayas-alloymetal.html

Mohenjodro 0304 seal impression http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/hieroglyph-multiplex-ayas-alloymetal.html

There are some who define writing as only alphabet (consonant, vowel) or syllable (phoneme) representations to signify sounds of a language.

This restrictive definition rules out writing systems which express ideas, exemplified by Chinese writing.

This restrictive definition also rules out mlecchita vikalpa type of writing systems which use hieroglyphs to signify words with more than one meaning: a meaning to signify, say, an object as a drawing (e.g. bharati 'partridge, quail'); another meaning to signify an entirely different object as a life-activity (e.g. bharati 'alloy metal of copper, pewter, tin'). In such a vikalpa (alternative), a hieroglyph denotes a partidge/quail but the intended message is an alloy metal.

It is unclear why languages evolve with the use of similar sounding words (homonyms) to signify different meanings.

A characteristic feature of many languages of Indian sprachbund (speech union) is that homonyms are frequently encountered. There is also a language characteristic of reduplications of spoken words in Indiansprachbund. (A precise account of reduplication feature of languages is at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reduplication ) The term sprachbund has a synonym in linguistic studies: linguistic area or areal linguistics. In the context of Indian languages the phrase got into vogue from an author of Dravidian Etymological Dictionary: Emeneau, M. (1956). "India as a Linguistic Area". Language 32 (1): 3–16.

In a series of works, mlecchita vikalpa has been identified in Indus Script Corpora which has now grown to about 7000 inscriptions (Over 4500 identified in the Corpus in 3 volumes so far by Asko Parpola's team PLUS about 2000 Persian Gulf seals PLUS over 1000 cylinder seal impressions of Ancient Near East which use hieroglyphs of Indus Script).

For example, see the following use of a unique rebus-metonymy layered cipher for some hieroglyphs and hieroglyph-multiplexes of Indus script:

- fish: aya 'fish' (Munda) Rebus aya 'iron' (Gujarati)

- partridge/quail: bharati 'partridge/quail' Rebus: bharati 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' (Marathi)

- safflower: karaDi 'safflower' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' (Marathi) khambhaṛā ʻfinʼ (Lahnda)(CDIAL 13639) khambu 'plumage' (S.); khambh 'wing, feather' (Punjabi)(CDIAL 13640) rebus: kammaTa 'coiner, coinage, mint (Kannada):

- crocodile: karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

- ram: meD 'ram' Rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.)

- narrow-necked jar: karava 'narrow-necked jar' Rebus: kharva 'wealth'; karba 'iron' (Tulu)

- rim of jar: karNaka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNIka 'scribe'

- young bull: khond 'young bull' Rebus: khond 'turner' (metals)

- wallet: dhokra 'wallet' Rebus: dhokra 'cire perdue metalcaster'

- water-carrier: kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

- warrior: bhaTa 'warrior' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

- rhinoceros: kANDa 'rhinoceros' Rebus: kANDa 'implements'

It has been demonstrated that the Indus Script Corpora is catalogus catalogorum of metalwork and the metalcasters of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization where the writing system originated ca. 3300 BCE called themselves workers of metal alloy, bharata/bharati, thus as bhāratam janam in a very ancient document, a sacred text, Rigveda:

viśvāmitrasya rakṣati brahmedam bhāratam janam. RV3.53.12. (

It will be an error to rule out writing systems like Indus Script which deploy word-hieroglyph patterns of representation as distinct from syllable or consonant/vowel representation exemplified by Aramaic or Brāhmi or Kharoṣṭhī.

What is writing? Let us define what writing is NOT.

Writing is not doodle.

Writing is not scribble even if they may have constituted 'potters' marks' comparable to trade marks or road signs.

So, writing is an alternative representation to communicate language or thought. In the context of ancient Indian tradition, one such alternative is called mlecchita vikalpa, 'Meluhha cipher writing' -- identified as one of 64 arts to be learned by youth.

![Image result for indus script sign bird fish parenthesis]() Mohenjodro 0304 seal impression http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/hieroglyph-multiplex-ayas-alloymetal.html

Mohenjodro 0304 seal impression http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/08/hieroglyph-multiplex-ayas-alloymetal.html

There are some who define writing as only alphabet (consonant, vowel) or syllable (phoneme) representations to signify sounds of a language.

This restrictive definition rules out writing systems which express ideas, exemplified by Chinese writing.

This restrictive definition also rules out mlecchita vikalpa type of writing systems which use hieroglyphs to signify words with more than one meaning: a meaning to signify, say, an object as a drawing (e.g. bharati 'partridge, quail'); another meaning to signify an entirely different object as a life-activity (e.g. bharati 'alloy metal of copper, pewter, tin'). In such a vikalpa (alternative), a hieroglyph denotes a partidge/quail but the intended message is an alloy metal.

It is unclear why languages evolve with the use of similar sounding words (homonyms) to signify different meanings.

A characteristic feature of many languages of Indian sprachbund (speech union) is that homonyms are frequently encountered. There is also a language characteristic of reduplications of spoken words in Indiansprachbund. (A precise account of reduplication feature of languages is at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reduplication ) The term sprachbund has a synonym in linguistic studies: linguistic area or areal linguistics. In the context of Indian languages the phrase got into vogue from an author of Dravidian Etymological Dictionary: Emeneau, M. (1956). "India as a Linguistic Area". Language 32 (1): 3–16.

In a series of works, mlecchita vikalpa has been identified in Indus Script Corpora which has now grown to about 7000 inscriptions (Over 4500 identified in the Corpus in 3 volumes so far by Asko Parpola's team PLUS about 2000 Persian Gulf seals PLUS over 1000 cylinder seal impressions of Ancient Near East which use hieroglyphs of Indus Script).

For example, see the following use of a unique rebus-metonymy layered cipher for some hieroglyphs and hieroglyph-multiplexes of Indus script:

It has been demonstrated that the Indus Script Corpora is catalogus catalogorum of metalwork and the metalcasters of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization where the writing system originated ca. 3300 BCE called themselves workers of metal alloy, bharata/bharati, thus as bhāratam janam in a very ancient document, a sacred text, Rigveda:

viśvāmitrasya rakṣati brahmedam bhāratam janam. RV3.53.12. (

It will be an error to rule out writing systems like Indus Script which deploy word-hieroglyph patterns of representation as distinct from syllable or consonant/vowel representation exemplified by Aramaic or Brāhmi or Kharoṣṭhī.

Writing is not doodle.

Writing is not scribble even if they may have constituted 'potters' marks' comparable to trade marks or road signs.

So, writing is an alternative representation to communicate language or thought. In the context of ancient Indian tradition, one such alternative is called mlecchita vikalpa, 'Meluhha cipher writing' -- identified as one of 64 arts to be learned by youth.

There are some who define writing as only alphabet (consonant, vowel) or syllable (phoneme) representations to signify sounds of a language.

This restrictive definition rules out writing systems which express ideas, exemplified by Chinese writing.

This restrictive definition also rules out mlecchita vikalpa type of writing systems which use hieroglyphs to signify words with more than one meaning: a meaning to signify, say, an object as a drawing (e.g. bharati 'partridge, quail'); another meaning to signify an entirely different object as a life-activity (e.g. bharati 'alloy metal of copper, pewter, tin'). In such a vikalpa (alternative), a hieroglyph denotes a partidge/quail but the intended message is an alloy metal.

It is unclear why languages evolve with the use of similar sounding words (homonyms) to signify different meanings.

A characteristic feature of many languages of Indian sprachbund (speech union) is that homonyms are frequently encountered. There is also a language characteristic of reduplications of spoken words in Indiansprachbund. (A precise account of reduplication feature of languages is at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reduplication ) The term sprachbund has a synonym in linguistic studies: linguistic area or areal linguistics. In the context of Indian languages the phrase got into vogue from an author of Dravidian Etymological Dictionary: Emeneau, M. (1956). "India as a Linguistic Area". Language 32 (1): 3–16.

In a series of works, mlecchita vikalpa has been identified in Indus Script Corpora which has now grown to about 7000 inscriptions (Over 4500 identified in the Corpus in 3 volumes so far by Asko Parpola's team PLUS about 2000 Persian Gulf seals PLUS over 1000 cylinder seal impressions of Ancient Near East which use hieroglyphs of Indus Script).

For example, see the following use of a unique rebus-metonymy layered cipher for some hieroglyphs and hieroglyph-multiplexes of Indus script:

- fish: aya 'fish' (Munda) Rebus aya 'iron' (Gujarati)

- partridge/quail: bharati 'partridge/quail' Rebus: bharati 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' (Marathi)

- safflower: karaDi 'safflower' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' (Marathi) khambhaṛā ʻfinʼ (Lahnda)(CDIAL 13639) khambu 'plumage' (S.); khambh 'wing, feather' (Punjabi)(CDIAL 13640) rebus: kammaTa 'coiner, coinage, mint (Kannada):

- crocodile: karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

- ram: meD 'ram' Rebus: meD 'iron' (Ho.)

- narrow-necked jar: karava 'narrow-necked jar' Rebus: kharva 'wealth'; karba 'iron' (Tulu)

- rim of jar: karNaka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karNI 'supercargo' karNIka 'scribe'

- young bull: khond 'young bull' Rebus: khond 'turner' (metals)

- wallet: dhokra 'wallet' Rebus: dhokra 'cire perdue metalcaster'

- water-carrier: kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

- warrior: bhaTa 'warrior' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

- rhinoceros: kANDa 'rhinoceros' Rebus: kANDa 'implements'

It has been demonstrated that the Indus Script Corpora is catalogus catalogorum of metalwork and the metalcasters of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization where the writing system originated ca. 3300 BCE called themselves workers of metal alloy, bharata/bharati, thus as bhāratam janam in a very ancient document, a sacred text, Rigveda:

viśvāmitrasya rakṣati brahmedam bhāratam janam. RV3.53.12. (

It will be an error to rule out writing systems like Indus Script which deploy word-hieroglyph patterns of representation as distinct from syllable or consonant/vowel representation exemplified by Aramaic or Brāhmi or Kharoṣṭhī.

The system of writing, mlecchita vikalpa by bhāratam janam was matched by the splendour of prosody calledchandas in Rigveda. Mlecchita vikalpa encoded speech (mleccha/meluhha), while chandas encoded mantras like the one cited from Rishi Viśvāmitra who also recited the Gāyatri mantra venerating the effulgent sun and making speech resonate with anāhata nāda brahman 'unstruck sound cosmic-consciousness' of vāk, speech as mother divine.

Addendum to: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2016/04/heralding-civilization-bronze-age.html

![]()

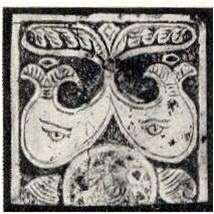

What is often cited as 'tri-ratna' or 'srivatsa' or 'nandipada' symbol is seen to be a hypertext, an Indus Script hieroglyph-multiplex, composed of: 1. lotus; 2. two fish-fins; 3. two petals; 4. spathe. The hypertext is superscipted together with two petals on a circle. The centrepiece is a skambha, 'pillar' (as a phonetic determinant of khambhaṛā 'fish-fin'). The entire hypertext is superscripted by a spoked wheel.

1. tAmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tAmra 'copper'

1. tAmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tAmra 'copper'

2. khambhaṛā ʻfinʼ (kammaṭa 'coiner, coinage, mint (Kannada):

3. dala 'petal' rebus: ḍhāḷakī 'ingot'

4. sippī ʻspathe of date palmʼ Rebus: sippi 'artificer, craftsman'

5. dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal'

6. goTa 'round' rebus 1: khoTa 'ingot' (phonetic determinative of the two metals atop the circle); rebus 2: goTa 'laterite ferrite ore'

7. eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arA 'spokes' rebus: Ara 'brass'.

Thus, the proclamation atop Sanchi/Bharhut torana is a kammaṭa 'coinage, coiner, mint' with competence in metalwork with copper, ferrite ores, brass, ingots, metal-sculpting (casting).

dala 'petal' Rebus: ḍhāḷako = a large ingot (G.) ḍhāḷakī = a metal heated and poured into a mould; a solid piece of metal; an ingot (G.)

Hieroglyph: Pali sippī- pearl oyster, Pkt. sippī- id., etc. (DEDR 2535). sippī f. ʻspathe of date palmʼ Rebus: sippi 'artificer, craftsman'. śilpin ʻ skilled in art ʼ, m. ʻ artificer ʼ Gaut., śilpika<-> ʻ skilled ʼ MBh. [śílpa -- ] Pa. sippika -- m. ʻ craftsman ʼ, NiDoc. śilpiǵa, Pk. sippi -- , °ia -- m.; A. xipini ʻ woman clever at spinning and weaving ʼ; OAw. sīpī m. ʻ artizan ʼ; M. śĩpī m. ʻ a caste of tailors ʼ; Si. sipi -- yā ʻ craftsman ʼ.(CDIAL 12471) சிற்பியர். (சூடா.) சிற்பம்¹ ciṟpam , n. < šilpa. 1. Artistic skill; தொழிலின் திறமை. செருக்கயல் சிற்பமாக (சீவக. 2716). 2. Fine or artistic workmanship; நுட்பமான தொழில். சிற்பந் திகழ்தரு திண்மதில் (திருக்கோ. 305). சிற்பர் ciṟpar , n. < šilpa. Mechanics, artisans, stone-cutters; சிற்பிகள். (W .)சிற்பி ciṟpi , n. < šilpin. Mechanic, artisan, stone-cutter; கம்மியன். (சூடா.)சிற்பியல் ciṟpiyal , n. < சிற்பம்¹ + இயல். Architecture, as an art; சிற்பசாஸ்திரம். மாசில் கம் மத்துச் சிற்பியற் புலவர் (பெருங். இலாவாண. 4, 50).

7. eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arA 'spokes' rebus: Ara 'brass'.

Thus, the proclamation atop Sanchi/Bharhut torana is a kammaṭa 'coinage, coiner, mint' with competence in metalwork with copper, ferrite ores, brass, ingots, metal-sculpting (casting).

Sadakana Bull Maharathis of Chandravalli . ಚಂದ್ರವಳ್ಳಿಯ ( ಚಿತ್ರದುರ್ಗ ) ಸದಕನ ಮಹಾರಥಿಗಳು .(30 BC- 70 AD)

, Lead karshapana. Zebu. Brahmi legend: Maharathi putasa sudakana (kanhasa) Krishna Six arched hill with crescent, wavy line below, nandipada,

poLa 'zebu' rebus: poLa 'magnetite ferrite ore'meTTu 'mound' rebus: meD 'iron' kuThAru 'crucible' rebus: kuThAru 'armourer'kANDa 'water' rebus: kaNDa 'implements'kammaṭa 'mint'sattva 'svastika' rebus: jasta 'zinc'

Taxila, Uninscribed die-struck Coin (200-150 BC), MIGIS-4 type 578, 3.94g. Obv: Lotus standard flanked by banners in a railing, with two small three-arched hill symbols on either side. Rev: Three-arched hill with crescent above a bold 'open cross' symbol.

![FIG. 20. ANCIENT INDIAN COIN. (Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)]() Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.

Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.

The Migration of Symbols, by Goblet d'Alviella, [1894

(Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)

kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

dala 'petal' rebus: dhALaki 'ingot'![]() śrivatsa symbol [with its hundreds of stylized variants, depicted on Pl. 29 to 32] occurs in Bogazkoi (Central Anatolia) dated ca. 6th to 14th cent. BCE on inscriptions Pl. 33, Nandipāda-Triratna at: Bhimbetka, Sanchi, Sarnath and Mathura] Pl. 27, Svastika symbol: distribution in cultural periods] The association of śrivatsa with ‘fish’ is reinforced by the symbols binding fish in Jaina āyāgapaṭas (snake-hood?) of Mathura (late 1st cent. BCE). śrivatsa symbol seems to have evolved from a stylied glyph showing ‘two fishes’. In the Sanchi stupa, the fish-tails of two fishes are combined to flank the ‘śrivatsa’ glyph. In a Jaina āyāgapaṭa, a fish is ligatured within the śrivatsa glyph, emphasizing the association of the ‘fish’ glyph with śrivatsa glyph.

śrivatsa symbol [with its hundreds of stylized variants, depicted on Pl. 29 to 32] occurs in Bogazkoi (Central Anatolia) dated ca. 6th to 14th cent. BCE on inscriptions Pl. 33, Nandipāda-Triratna at: Bhimbetka, Sanchi, Sarnath and Mathura] Pl. 27, Svastika symbol: distribution in cultural periods] The association of śrivatsa with ‘fish’ is reinforced by the symbols binding fish in Jaina āyāgapaṭas (snake-hood?) of Mathura (late 1st cent. BCE). śrivatsa symbol seems to have evolved from a stylied glyph showing ‘two fishes’. In the Sanchi stupa, the fish-tails of two fishes are combined to flank the ‘śrivatsa’ glyph. In a Jaina āyāgapaṭa, a fish is ligatured within the śrivatsa glyph, emphasizing the association of the ‘fish’ glyph with śrivatsa glyph.

(After Plates in: Savita Sharma, 1990, Early Indian symbols, numismatic evidence, Delhi, Agama Kala Prakashan; cf. Shah, UP., 1975, Aspects of Jain Art and Architecture, p.77)

Khandagiri caves (2nd cent. BCE) Cave 3 (Jaina Ananta gumpha). Fire-altar?, śrivatsa, svastika(hieroglyphs) (King Kharavela, a Jaina who ruled Kalinga has an inscription dated 161 BCE) contemporaneous with Bharhut and Sanchi and early Bodhgaya.

Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.

Fig. 20. Ancient Indian Coin.The Migration of Symbols, by Goblet d'Alviella, [1894

(Archæological Survey of India, vol. x., pl. ii., fig. 8.)

kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'

dala 'petal' rebus: dhALaki 'ingot'

(After Plates in: Savita Sharma, 1990, Early Indian symbols, numismatic evidence, Delhi, Agama Kala Prakashan; cf. Shah, UP., 1975, Aspects of Jain Art and Architecture, p.77)

Kushana period, 1st century C.E.From Mathura Red Sandstone 89x92cm

books.google.com/books?id=evtIAQAAIAAJ&q=In+the+image...

![]() Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.

Ayagapatta, Kankali Tila, Mathura.uddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet." http://www.cristoraul.com/ENGLISH/readinghall/UniversalHistory/INDIA/Cambridge/I/CHAPTER_XXVI.html

![]() Vishnu Sandstone Relief From Meerut India Indian Civilization 10th Century Dharma chakra. Srivatsa. Gada.Rebus: dhamma 'dharma' (Pali) Hieroglyphs: dām 'garland, rope':Hieroglyphs: hangi 'mollusc' + dām 'rope, garland' dã̄u m. ʻtyingʼ; puci 'tail' Rebus: puja 'worship'

Vishnu Sandstone Relief From Meerut India Indian Civilization 10th Century Dharma chakra. Srivatsa. Gada.Rebus: dhamma 'dharma' (Pali) Hieroglyphs: dām 'garland, rope':Hieroglyphs: hangi 'mollusc' + dām 'rope, garland' dã̄u m. ʻtyingʼ; puci 'tail' Rebus: puja 'worship'

Rebus: ariya sanghika dhamma puja 'veneration of arya sangha dharma'

![]() Hieroglyph: Four hieroglyphs are depicted. Fish-tails pair are tied together. The rebus readings are as above: ayira (ariya) dhamma puja 'veneration of arya dharma'.

Hieroglyph: Four hieroglyphs are depicted. Fish-tails pair are tied together. The rebus readings are as above: ayira (ariya) dhamma puja 'veneration of arya dharma'.

ayira 'fish' Rebus:ayira, ariya, 'person of noble character'. युगल yugala 'twin' Rebus: जुळणें (p. 323) [ juḷaṇēṃ ] v c & i (युगल S through जुंवळ ) To put together in harmonious connection or orderly disposition (Marathi). Thus an arya with orderly disposition.

sathiya 'svastika glyph' Rebus: Sacca (adj.) [cp. Sk. satya] real, true D i.182; M ii.169; iii.207; Dh 408; nt. saccaŋ truly, verily, certainly Miln 120; saccaŋ kira is it really true? D i.113; Vin i.45, 60; J (Pali)

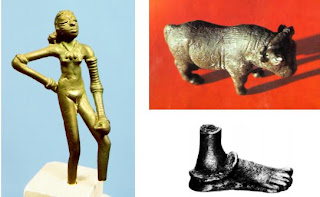

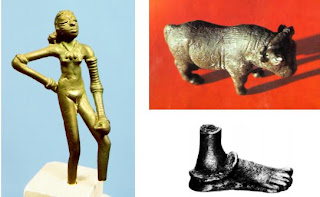

सांगाडा [ sāṅgāḍā ] m The skeleton, box, or frame (of a building, boat, the body &c.), the hull, shell, compages. 2 Applied, as Hulk is, to any animal or thing huge and unwieldy.सांगाडी [ sāṅgāḍī ] f The machine within which a turner confines and steadies the piece he has to turn. Rebus: सांगाती [ sāṅgātī ] a (Better संगती ) A companion, associate, fellow.![]() Buddha-pada (feet of Buddha), carved on a rectangular slab. The margin of the slab was carved with scroll of acanthus and rosettes. The foot-print shows important symbols like triratna, svastika, srivatsa,ankusa and elliptical objects, meticulously carved in low-relief. From Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, being assignable on paleographical grounds to circa 1st century B.C --2nd century CE,

Buddha-pada (feet of Buddha), carved on a rectangular slab. The margin of the slab was carved with scroll of acanthus and rosettes. The foot-print shows important symbols like triratna, svastika, srivatsa,ankusa and elliptical objects, meticulously carved in low-relief. From Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, being assignable on paleographical grounds to circa 1st century B.C --2nd century CE,

uddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet." http://www.cristoraul.com/ENGLISH/readinghall/UniversalHistory/INDIA/Cambridge/I/CHAPTER_XXVI.html

Vishnu Sandstone Relief From Meerut India Indian Civilization 10th Century Dharma chakra. Srivatsa. Gada.

Rebus: dhamma 'dharma' (Pali) Hieroglyphs: dām 'garland, rope':

Hieroglyph: Four hieroglyphs are depicted. Fish-tails pair are tied together. The rebus readings are as above: ayira (ariya) dhamma puja 'veneration of arya dharma'.

Hieroglyph: Four hieroglyphs are depicted. Fish-tails pair are tied together. The rebus readings are as above: ayira (ariya) dhamma puja 'veneration of arya dharma'.sathiya 'svastika glyph' Rebus: Sacca (adj.) [cp. Sk. satya] real, true D i.182; M ii.169; iii.207; Dh 408; nt. saccaŋ truly, verily, certainly Miln 120; saccaŋ kira is it really true? D i.113; Vin i.45, 60; J (Pali)

Buddha-pada (feet of Buddha), carved on a rectangular slab. The margin of the slab was carved with scroll of acanthus and rosettes. The foot-print shows important symbols like triratna, svastika, srivatsa,ankusa and elliptical objects, meticulously carved in low-relief. From Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, being assignable on paleographical grounds to circa 1st century B.C --2nd century CE,

Buddha-pada (feet of Buddha), carved on a rectangular slab. The margin of the slab was carved with scroll of acanthus and rosettes. The foot-print shows important symbols like triratna, svastika, srivatsa,ankusa and elliptical objects, meticulously carved in low-relief. From Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh, being assignable on paleographical grounds to circa 1st century B.C --2nd century CE,![An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre, from Mathura]() The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum.

The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum.

![An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre and inscription below, from Mathura]() An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre and inscription below, from Mathura. "Photograph taken by Edmund William Smith in 1880s-90s of a Jain homage tablet. The tablet was set up by the wife of Bhadranadi, and it was found in December 1890 near the centre of the mound of the Jain stupa at Kankali Tila. Mathura has extensive archaeological remains as it was a large and important city from the middle of the first millennium onwards. It rose to particular prominence under the Kushans as the town was their southern capital. The Buddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet. The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum." http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/a/largeimage58907.html

An ayagapata or Jain homage tablet, with small figure of a tirthankara in the centre and inscription below, from Mathura. "Photograph taken by Edmund William Smith in 1880s-90s of a Jain homage tablet. The tablet was set up by the wife of Bhadranadi, and it was found in December 1890 near the centre of the mound of the Jain stupa at Kankali Tila. Mathura has extensive archaeological remains as it was a large and important city from the middle of the first millennium onwards. It rose to particular prominence under the Kushans as the town was their southern capital. The Buddhist, Brahmanical and Jain faiths all thrived at Mathura, and we find deities and motifs from all three and others represented in sculpture. In reference to this photograph in the list of photographic negatives, Bloch wrote that, "The technical name of such a panel was ayagapata [homage panel]." The figure in the centre is described as a Tirthamkara, a Jain prophet. The piece is now in the Lucknow Museum." http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/apac/photocoll/a/largeimage58907.html![]()

![]() View of the Jaina stupa excavated at Kankali Tila, Mathura.

View of the Jaina stupa excavated at Kankali Tila, Mathura.![]() Manoharpura. Svastika. Top of āyāgapaṭa. Red Sandstone. Lucknow State Museum. (Scan no.0053009, 0053011, 0053012 ) See: https://www.academia.edu/11522244/A_temple_at_Sanchi_for_Dhamma_by_a_k%C4%81ra%E1%B9%87ik%C4%81_sanghin_guild_of_scribes_in_Indus_writing_cipher_continuum

Manoharpura. Svastika. Top of āyāgapaṭa. Red Sandstone. Lucknow State Museum. (Scan no.0053009, 0053011, 0053012 ) See: https://www.academia.edu/11522244/A_temple_at_Sanchi_for_Dhamma_by_a_k%C4%81ra%E1%B9%87ik%C4%81_sanghin_guild_of_scribes_in_Indus_writing_cipher_continuum

![]()

Ayagapata (After Huntington)

![]()

Jain votive tablet from Mathurå. From Czuma 1985, catalogue number 3. Fish-tail is the hieroglyph together with svastika hieroglyph, fish-pair hieroglyph, safflower hieroglyph, cord (tying together molluscs and arrow?)hieroglyph multiplex, lathe multiplex (the standard device shown generally in front of a one-horned young bull on Indus Script corpora), flower bud (lotus) ligatured to the fish-tail. All these are venerating hieroglyphs surrounding the Tirthankara in the central medallion.

Pali etyma point to the use of 卐 with semant. 'auspicious mark'; on the Sanchi stupa; the cognate gloss is: sotthika, sotthiya 'blessed'.

Or. ṭaü ʻ zinc, pewter ʼ(CDIAL 5992). jasta 'zinc' (Hindi) sathya, satva 'zinc' (Kannada) The hieroglyph used on Indus writing consists of two forms: 卐卍. Considering the phonetic variant of Hindi gloss, it has been suggested for decipherment of Meluhha hieroglyphs in archaeometallurgical context that the early forms for both the hieroglyph and the rebus reading was: satya.

The semant. expansion relating the hieroglyph to 'welfare' may be related to the resulting alloy of brass achieved by alloying zinc with copper. The brass alloy shines like gold and was a metal of significant value, as significant as the tin (cassiterite) mineral, another alloying metal which was tin-bronze in great demand during the Bronze Age in view of the scarcity of naturally occurring copper+arsenic or arsenical bronze.

I suggest that the Meluhha gloss was a phonetic variant recorded in Pali etyma: sotthiya. This gloss was represented on Sanchi stupa inscription and also on Jaina ayagapata offerings by worshippers of ariya, ayira dhamma, by the same hieroglyph (either clockwise-twisting or anti-clockwise twisting rotatory symbol of svastika). Linguists may like to pursue this line further to suggest the semant. evolution of the hieroglyph over time, from the days of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization to the narratives of Sanchi stupa or Ayagapata of Kankali Tila.

स्वस्ति [ svasti ] ind S A particle of benediction. Ex. राजा तुला स्वस्ति असो O king! may it be well with thee!; रामाय स्वस्ति रावणाय स्वस्ति ! 2 An auspicious particle. 3 A term of sanction or approbation (so be it, amen &c.) 4 Used as s n Welfare, weal, happiness.स्वस्तिक [ svastika ] n m S A mystical figure the inscription of which upon any person or thing is considered to be lucky. It is, amongst the जैन , the emblem of the seventh deified teacher of the present era. It consists of 卍. 2 A temple of a particular form with a portico in front. 3 Any auspicious or lucky object.(Marathi)

svasti f. ʻ good fortune ʼ RV. [su -- 2 , √as 1 ]Pa. suvatthi -- , sotthi -- f. ʻ well -- being ʼ, NiDoc. śvasti; Pk. satthi -- , sotthi -- f. ʻ blessing, welfare ʼ; Si. seta ʻ good fortune ʼ < *soti (H. Smith EGS 185 < sustha -- ). svastika ʻ *auspicious ʼ, m. ʻ auspicious mark ʼ R. [svastí -- ]Pa. sotthika -- , °iya -- ʻ auspicious ʼ; Pk. satthia -- , sot° m. ʻ auspicious mark ʼ; H. sathiyā, sati° m. ʻ mystical mark of good luck ʼ; G. sāthiyɔ m. ʻ auspicious mark painted on the front of a house ʼ.(CDIAL 13915, 13916)

Nibbānasotthi (welfare). saccena suvatthi hotu nibbānaŋ Sn 235.Sotthi (f.) [Sk. svasti=su+asti] well -- being, safety, bless ing A iii. 38=iv. 266 ("brings future happiness"); J i. 335; s. hotu hail! D i. 96; sotthiŋ in safety, safely Dh 219 (=anupaddavena DhA iii. 293); Pv iv. 64 (=nirupaddava PvA 262); Sn 269; sotthinā safely, prosperously D i. 72, 96; ii. 346; M i. 135; J ii. 87; iii. 201. suvatthi the same J iv. 32. See sotthika & sovatthika. -- kamma a blessing J i. 343. -- kāra an utterer of blessings, a herald J vi. 43. -- gata safe wandering, prosperous journey Mhvs 8, 10; sotthigamana the same J i. 272. -- bhāva well -- being, prosperity, safety J i. 209; iii. 44; DhA ii. 58; PvA 250. -- vācaka utterer of blessings, a herald Miln 359. -- sālā a hospital Mhvs 10, 101.Sotthika (& ˚iya) (adj.) [fr. sotthi] happy, auspicious, blessed, safe VvA 95; DhA ii. 227 (˚iya; in phrase dīgha˚ one who is happy for long [?]).Sotthivant (adj.) [sotthi+vant] lucky, happy, safe Vv 8452 .Sovatthika (adj.) [either fr. sotthi with diaeresis, or fr. su+atthi+ka=Sk. svastika] safe M i. 117; Vv 187 (=sotthika VvA 95); J vi. 339 (in the shape of a svastika?); Pv iv. 33 (=sotthi -- bhāva -- vāha PvA 250). -- âlankāra a kind of auspicious mark J vi. 488. (Pali)

[quote]Cunningham, later the first director of the Archaeological Survey of India, makes the claim in: The Bhilsa Topes (1854). Cunningham, surveyed the great stupa complex at Sanchi in 1851, where he famously found caskets of relics labelled 'Sāriputta' and 'Mahā Mogallāna'. [1] The Bhilsa Topes records the features, contents, artwork and inscriptions found in and around these stupas. All of the inscriptions he records are in Brāhmī script. What he says, in a note on p.18, is: "The swasti of Sanskrit is the suti of Pali; the mystic cross, or swastika is only a monogrammatic symbol formed by the combination of the two syllables, su + ti = suti." There are two problems with this. While there is a word suti in Pali it is equivalent to Sanskrit śruti'hearing'. The Pali equivalent ofsvasti is sotthi; and svastika is either sotthiya or sotthika. Cunningham is simply mistaken about this. The two letters su + ti in Brāhmī script are not much like thesvastika. This can easily been seen in the accompanying image on the right, where I have written the word in the Brāhmī script. I've included the Sanskrit and Pali words for comparison. Cunningham's imagination has run away with him. Below are two examples of donation inscriptions from the south gate of the Sanchi stupa complex taken from Cunningham's book (plate XLX, p.449).

![]()

"Note that both begin with a lucky svastika. The top line reads 卐 vīrasu bhikhuno dānaṃ - i.e. "the donation of Bhikkhu Vīrasu." The lower inscription also ends with dānaṃ, and the name in this case is perhaps pānajāla (I'm unsure about jā). Professor Greg Schopen has noted that these inscriptions recording donations from bhikkhus and bhikkhunis seem to contradict the traditional narratives of monks and nuns not owning property or handling money. The last symbol on line 2 apparently represents the three jewels, and frequently accompanies such inscriptions...Müller [in Schliemann(2), p.346-7] notes that svasti occurs throughout 'the Veda' [sic; presumably he means the Ṛgveda where it appears a few dozen times]. It occurs both as a noun meaning 'happiness', and an adverb meaning 'well' or 'hail'. Müller suggests it would correspond to Greek εὐστική (eustikē) from εὐστώ (eustō), however neither form occurs in my Greek Dictionaries. Though svasti occurs in the Ṛgveda, svastika does not. Müller traces the earliest occurrence of svastika to Pāṇini's grammar, the Aṣṭādhyāyī, in the context of ear markers for cows to show who their owner was. Pāṇini discusses a point of grammar when making a compound using svastika and karṇa, the word for ear. I've seen no earlier reference to the word svastika, though the symbol itself was in use in the Indus Valley civilisation.[unquote]

1. Cunningham, Alexander. (1854) The Bhilsa topes, or, Buddhist monuments of central India : comprising a brief historical sketch of the rise, progress, and decline of Buddhism; with an account of the opening and examination of the various groups of topes around Bhilsa. London : Smith, Elder. [possibly the earliest recorded use of the word swastika in English].

2. Schliemann, Henry. (1880). Ilios : the city and country of the Trojans : the results of researches and discoveries on the site of Troy and through the Troad in the years 1871-72-73-78-79. London : John Murray.

http://jayarava.blogspot.in/2011/05/svastika.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/deciphering-indus-script-meluhha.html

Views of Koenraad Elst and Carl Sagan on Svastika symbol

"Koenraad Elst points out that swastika had been a fairly prevalent symbol of the pre-Christian Europe and remained pretty much in vogue even until the 20th century. British troops preparing to help Finland in the war of winter 1939-40 against Soviet aggression painted swastikas, then a common Finnish symbol, on their airplanes. It was also a symbol of Austrian and German völkisch subculture where it was associated with the celebration of the summer solstice. In 1919, the dentist Friedrich Krohn adopted it as the symbol of the DAP because it was understood as the symbol of the Nordic culture. Hitler adopted a variant of the DAP symbol and added the three color scheme of the Second Reich to rival the Communist hammer and sickle as a psychological weapon of propaganda (Elst, Koenraad: The Saffron Swastika, Volume 1, pp. 31-32)...Besides pre-Christian and Christian Europe, the swastika has been depicted across many ancient cultures over several millennia. Carl Sagan infers that it was inspired by the sightings of comets by the ancients. In India, it was marked on doorsteps as it was believed to bring good fortune. It was prevalent worldwide by the second millennium as Heinrich Schliemann, the discoverer of Troy, found. It was depicted in Buddhist caverns in Afghanistan. Jaina, who emphasize on avoidance of harm, have considered it a sign of benediction. The indigenous peoples of North America depicted it in their pottery, blankets, and beadwork. It was widely used in Hellenic Europe and Brazil. One also finds depictions of the swastika, turning both ways, from the seals of the Indus Valley Civilization (IVC) dating back to 2,500 BCE, as well as on coins in the 6th century BCE Greece (Sagan, Carl and Druyan, Ann: Comet, pp. 181-186)" loc.cit.: http://indiafacts.co.in/the-swastika-is-not-a-symbol-of-hatred/

Svastika is a hieroglyph used in Indus Script corpora.It denoted jasta, 'zinc'Mirror:

https://www.academia.edu/8362658/Meluhha_hieroglyph_5_svastika_read_rebus_tuttha_sulphate_of_zinc

A hieroglyph which is repeatedly deployed in Indus writing is svastika. What is the ancient reading and meaning?

I suggest that it reads sattva. Its rebus rendering and meaning is zastas 'spelter or sphalerite or sulphate of zinc.'

Zinc occurs in sphalerite, or sulphate of zinc in five colours.

The Meluhha gloss for 'five' is: taṭṭal Homonym is: ṭhaṭṭha ʻbrassʼ(i.e. alloy of copper + zinc). *ṭhaṭṭha ʻ brass ʼ. [Onom. from noise of hammering brass? -- N. ṭhaṭṭar ʻ an alloy of copper and bell metal ʼ. *ṭhaṭṭhakāra ʻ brass worker ʼ. 2. *ṭhaṭṭhakara -- 1. Pk. ṭhaṭṭhāra -- m., K. ṭhö̃ṭhur m., S. ṭhã̄ṭhāro m., P. ṭhaṭhiār, °rā m.2. P. ludh. ṭhaṭherā m., Ku. ṭhaṭhero m., N. ṭhaṭero, Bi. ṭhaṭherā, Mth. ṭhaṭheri, H. ṭhaṭherā m. (CDIAL 5491, 5493)

Glosses for zinc are: sattu (Tamil), satta, sattva (Kannada) jasth जस्थ । त्रपु m. (sg. dat. jastas जस्तस् ), zinc, spelter; pewter; zasath ज़स््थ् or zasuth ज़सुथ् । त्रपु m. (sg. dat. zastas ज़स्तस् ), zinc, spelter, pewter (cf. Hindī jast).

jastuvu; । त्रपूद्भवः adj. (f. jastüvü), made of zinc or pewter.(Kashmiri).

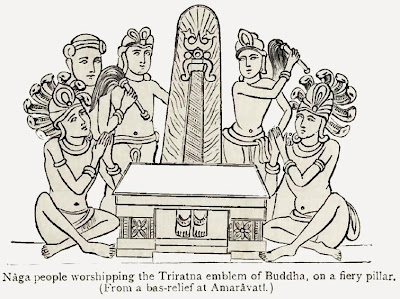

Fig. 32. (After T Wilson opcit)FOOTPRINT OF BUDDHA WITH SWASTIKA, FROM AMARAVATI TOPE.From a figure by Fergusson and Schliemann.in remote ages,' pl. 41, figs. 20-24![]()

![]() 'Triratna' or "Three Jewels" symbol, on a Buddha footprint (bottom symbol, the top symbol being a dharmachakra). 1st century CE,Gandhara.Begram ivories. Plate 389 Reference: Hackin, 1954, fig.195, no catalog N°. According to an inscription on the southern gate of Sanchi stupa,it has been carved by ivory carvers of Vidisha.Southern Gateway panel information:West pillar Front East Face has an inscription. Vedisakehi dantakarehi rupa-kammam katam - On the border of this panel – Epigraphia Indica vol II – written in Brahmi, language is Pali – the carving of this sculpture is done by the ivory carvers of Vedisa (Vidisha). http://puratattva.in/2012/03/21/sanchi-buddham-dhammam-sangahm-5-1484 Ta. kaṇ eye, aperture, orifice, star of a peacock's tail. Ma. kaṇ, kaṇṇu eye, nipple, star in peacock's tail, bud. Ko. kaṇ eye. To. koṇ eye, loop in string. Ka. kaṇ eye, small hole, orifice. Koḍ. kaṇṇï id. Pe. kaṇga (pl. -ŋ, kaṇku) id. Manḍ. kan (pl. -ke) id. Kui kanu (pl. kan-ga), (K.) kanu (pl. kaṛka) id. Kuwi (F.) kannū (S.) kannu (pl. kanka), (Su. P. Isr.) kanu (pl. kaṇka) id. (DEDR 1159). Rebus: kanga 'brazier' (Kashmiri)

'Triratna' or "Three Jewels" symbol, on a Buddha footprint (bottom symbol, the top symbol being a dharmachakra). 1st century CE,Gandhara.Begram ivories. Plate 389 Reference: Hackin, 1954, fig.195, no catalog N°. According to an inscription on the southern gate of Sanchi stupa,it has been carved by ivory carvers of Vidisha.Southern Gateway panel information:West pillar Front East Face has an inscription. Vedisakehi dantakarehi rupa-kammam katam - On the border of this panel – Epigraphia Indica vol II – written in Brahmi, language is Pali – the carving of this sculpture is done by the ivory carvers of Vedisa (Vidisha). http://puratattva.in/2012/03/21/sanchi-buddham-dhammam-sangahm-5-1484 Ta. kaṇ eye, aperture, orifice, star of a peacock's tail. Ma. kaṇ, kaṇṇu eye, nipple, star in peacock's tail, bud. Ko. kaṇ eye. To. koṇ eye, loop in string. Ka. kaṇ eye, small hole, orifice. Koḍ. kaṇṇï id. Pe. kaṇga (pl. -ŋ, kaṇku) id. Manḍ. kan (pl. -ke) id. Kui kanu (pl. kan-ga), (K.) kanu (pl. kaṛka) id. Kuwi (F.) kannū (S.) kannu (pl. kanka), (Su. P. Isr.) kanu (pl. kaṇka) id. (DEDR 1159). Rebus: kanga 'brazier' (Kashmiri)![Buddhist symbols, Shrivatsa in Triratana over the chakra wheel on Torana, stupas of Sanchi, UNESCO World Heritage - Stock Image]()

![Buddhist symbols, Shrivatsa in Triratana over the chakra wheel on Torana, stupas of Sanchi, UNESCO World Heritage - Stock Image]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Variants of 'Tri-ratna' Grey-schist relief, Gandhara. These variants should be contrasted with the Indus Script hypertext signifies kammaṭa 'mint'. There are three flowers decorating three arms of the W symbol to signify three jewels. Dharmacakka upholds the hieroglyph-multiplex, making these variants clearly influenced by Bauddha dhamma. An alternative rebus reading could be: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS tAmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tAmra 'copper' Thus, rendering moltencast copper forge/smithy as a venerated kole.l 'smithy' rebus; kole.l 'temple'.