Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/oeajp67

It is a remarkable 'rosetta stone' because it validates the expression used by Panini: ayaskANDa अयस्--काण्ड [p= 85,1] m. n. " a quantity of iron " or " excellent iron " , (g. कस्का*दि q.v.). The early semantics of this expression is likely to be 'metal implements' compared with the Santali expression to signify iron implements: meď 'copper' (Slovak), me~r.he~t khanDa (Santali).

Santali glosses.

Santali glosses.It is a remarkable 'rosetta stone' because it provides archaemetallurgical and also epigraphic evidence of metal implements by holding them as contents of the storage pot, describes them with a hieroglyph of Indus Script as a painting on the pot itself.

Consistent with this decipherment of Susa pot Indus Script hieroglyphs, a cylinder seal found at Susa is also deciphered as metalwork catalogue.

The Susa cylinder seal with Indus Script hieroglyphs has been deciphered:

Guild of artisans working with alloy implements

barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c.(Marathi)

S. pāṭri f. ʻ large earth or wooden dish ʼ, pāṭroṛo m. ʻ wooden trough ʼ; pāˊtra n. ʻ drinking vessel, dish ʼ RV., °aka -- n., pātrīˊ- ʻ vessel ʼ Gr̥ŚrS. [√pā 1 ]Pa. patta -- n. ʻ bowl ʼ, °aka -- n. ʻ little bowl ʼ, pātĭ̄ -- f.; Pk. patta -- n., °tī -- f., amg. pāda -- , pāya -- n., pāī -- f. ʻ vessel ʼ; Sh. păti̯ f. ʻ large long dish ʼ (← Ind.?); K. pātha r, dat. °tras m. ʻ vessel, dish ʼ, pôturu m. ʻ pan of a pair of scales ʼ (gaha na -- pāth, dat. pöċü f. ʻ jewels and dishes as part of dowry ʼ ← Ind.); L. pātrī f. ʻ earthen kneading dish ʼ, parāt f. ʻ large open vessel in which bread is kneaded ʼ, awāṇ. pātrī ʻ plate ʼ; P. pātar m. ʻ vessel ʼ, parāt f., parātṛā m. ʻ large wooden kneading vessel ʼ, ḍog. pāttar m. ʻ brass or wooden do. ʼ; Ku.gng. pāi ʻ wooden pot ʼ; B. pātil ʻ earthern cooking pot ʼ, °li ʻ small do. ʼ Or. pātiḷa, °tuḷi ʻ earthen pot ʼ, (Sambhalpur) sil -- pā ʻ stone mortar and pestle ʼ; Bi. patĭ̄lā ʻ earthen cooking vessel ʼ, patlā ʻ milking vessel ʼ, pailā ʻ small wooden dish for scraps ʼ; H. patīlā m. ʻ copper pot ʼ, patukī f. ʻ small pan ʼ; G. pātrũ n. ʻ wooden bowl ʼ,pātelũ n. ʻ brass cooking pot ʼ, parāt f. ʻ circular dish ʼ (→ M. parāt f. ʻ circular edged metal dish ʼ); Si. paya ʻ vessel ʼ, päya (< pātrīˊ -- ). pāˊtra -- : S.kcch. pātar f. ʻ round shallow wooden vessel for kneading flour ʼ; WPah.kṭg. (kc.) pərāt f. (obl. -- i ) ʻ large plate for kneading dough ʼ ← P.; Md. tilafat ʻ scales ʼ (+ tila <tulāˊ -- ).(CDIAL 8055)

pattar 'trough'; rebus pattar, vartaka 'merchant, goldsmith' (Tamil) பத்தர்² pattar , n. < T. battuḍu. A caste title of goldsmiths; தட்டார் பட்டப்பெயருள் ஒன்று.

mainda 'clod breaker' Rebus: meD 'iron' dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'

piparā 'ant' (Assamese) Rebus: pippala 'knife' (Prakritam)

kuṭi 'curve' PLUS dula 'pair' Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) PLUS dul 'cast metal'.

kaṭṭala 'door-frame' (Malayalam) Rebus: katthīl 'bronze' PLUS khāṇḍā 'notch' Rebus: kāṇḍā 'implements'. Thus, together, 'bronze implements'.

śanku ‘twelve-fingers’ measure’ (Samskritam) Rebus: śanku 'arrowhead'

kuṭi ‘water carrier’ (Te.) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) PLUS khāṇḍā 'notch' Rebus: kāṇḍā 'implements'. Thus, together, 'implements (out of) furnace'.

Fish is a frequently signified hieroglyph in Indus Script Corpora.

This indication of the occurrence, together, of two or more 'fish' hieroglyphs with modifiers is an assurance that the modifiers ar semantic indicators of how aya 'metal' is worked on by the artisans.

āĩsa ʻfish' (Oriya): āmiṣá n. ʻ flesh ʼ, āˊmiṣ -- n. ʻ raw flesh, dead body ʼ RV.Pa. āmisa -- n. ʻ raw meat, bait ʼ; Pk. āmisa -- n. ʻ flesh ʼ; B. ã̄is ʻ scales of fish ʼ; Or. āĩsa ʻ flesh, fish, fish scales ʼ; M. ã̄vas n. ʻ flesh of a kill left by a tiger to be eaten on the following day ʼ; Si. äma ʻ bait ʼ; -- der. A. ã̄hiyā ʻ having the smell of raw flesh or fish ʼ, B. ã̄ste (Chatterji ODBL 491(CDIAL 1256)

Munda: So. ayo `fish'. Go. ayu `fish'. Go <ayu> (Z), <ayu?u> (Z),, <ayu?> (A) {N} ``^fish''. Kh. kaDOG `fish'. Sa. Hako `fish'. Mu. hai (H) ~ haku(N) ~ haikO(M) `fish'. Ho haku `fish'. Bj. hai `fish'. Bh.haku `fish'. KW haiku ~ hakO |Analyzed hai-kO, ha-kO (RDM). Ku. Kaku`fish'.@(V064,M106) Mu. ha-i, haku `fish' (HJP). @(V341) ayu>(Z), <ayu?u> (Z) <ayu?>(A) {N} ``^fish''. #1370. <yO>\\<AyO>(L) {N} ``^fish''. #3612. <kukkulEyO>,,<kukkuli-yO>(LMD) {N} ``prawn''. !Serango dialect. #32612. <sArjAjyO>,,<sArjAj>(D) {N} ``prawn''. #32622. <magur-yO>(ZL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish''. *Or.<>. #32632. <ur+GOl-Da-yO>(LL) {N} ``a kind of ^fish''. #32642.<bal.bal-yO>(DL) {N} ``smoked fish''. #15163. Vikalpa: Munda: <aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree''.#10171. So<aDara>(L) {N} ``^scales of a fish, sharp bark of a tree''.

Indian mackerel Ta. ayirai, acarai, acalai loach, sandy colour, Cobitis thermalis; ayilai a kind of fish. Ma.ayala a fish, mackerel, scomber; aila, ayila a fish; ayira a kind of small fish, loach (DEDR 191)

aduru native metal (Ka.); ayil iron (Ta.) ayir, ayiram any ore (Ma.); ajirda karba very hard iron (Tu.)(DEDR 192). Ta. ayil javelin, lance, surgical knife, lancet.Ma. ayil javelin, lance; ayiri surgical knife, lancet. (DEDR 193). aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka. Siddhānti Subrahmaṇya’ Śastri’s new interpretation of the AmarakoŚa, Bangalore, Vicaradarpana Press, 1872, p.330); adar = fine sand (Ta.); ayir – iron dust, any ore (Ma.) Kur. adar the waste of pounded rice, broken grains, etc. Malt. adru broken grain (DEDR 134). Ma. aśu thin, slender;ayir, ayiram iron dust.Ta. ayir subtlety, fineness, fine sand, candied sugar; ? atar fine sand, dust. அய.ர³ ayir, n. 1. Subtlety, fineness; நணசம. (த_வ_.) 2. [M. ayir.] Fine sand; நணமணல. (மலசலப. 92.) ayiram, n. Candied sugar; ayil, n. cf. ayas. 1. Iron; 2. Surgical knife, lancet; Javelin, lance; ayilavaṉ, Skanda, as bearing a javelin (DEDR 341).Tu. gadarů a lump (DEDR 1196) áyas n. ʻ metal, iron ʼ RV.Pa. ayō nom. sg. n. and m., aya -- n. ʻ iron ʼ, Pk. aya -- n., Si. ya.ayaścūrṇa -- , ayaskāṇḍa -- , *ayaskūṭa -- .Addenda: áyas -- : Md. da ʻ iron ʼ, dafat ʻ piece of iron ʼ. ayaskāṇḍa m.n. ʻ a quantity of iron, excellent iron ʼ Pāṇ. gaṇ. [áyas -- , kāˊṇḍa -- ] Si. yakaḍa ʻ iron ʼ.(CDIAL 590, 591)

The vase a la cachette, shown with its contents. Acropole mound, Susa. Old Elamite period, ca. 2500 - 2400 BCE. Clay. H 201/4 in. (51 cm) Paris. http://www.louvre.fr/oeuvre-notices/vase-la-cachette

Indus Script hieroglyphs painted on the jar are: fish, quail and streams of water;

aya'fish' (Munda) rebus: aya'iron' (Gujarati) ayas'metal' (Rigveda)

baTa 'quail' Rebus: baTa'furnace'.

kāṇḍa 'water' Rebus: kāṇḍa'implements'.

Thus, read together, the proclamation on the jar by the painted hieroglyphs is: baTa ayas kāṇḍa'metal implements out of the furnace (smithy)'.

A quail'; painted on the top register of the jar.

A quail'; painted on the top register of the jar.

Fish painted on the rim and top segment of the storage pot.

Fish painted on the rim and top segment of the storage pot.- Jarre et couvercle

- Terre cuite peinteH. : 51 cm. ; D. : 26 cm.

- Sb 2723, Sb 2723 bis

- Aile Richelieu

Rez-de-chaussée

Iran, Suse au IIIe millénaire avant J.-C.

Salle 8

Vitrine 2 : Le Vase à la Cachette. Suse IVA (vers 2450 avant J.-C.). Fouilles Jacques de Morgan, 1907, tell de l'Acropole.

Notes by Nancie Herbin (Translated) on the treasure of copper and bronze objects:

This jar covered with a bowl contained, and a second pottery, buried treasure by its owner on the tell of the Acropolis of Susa. The set includes objects of various shapes and materials typical of an era when Susa, dominated by its Mesopotamian neighbors, kept numerous exchanges with areas ranging from the Gulf to the Indus.

A treasure hidden in a jar

This is a jar closed with a ducted bowl. The treasure called "vase in hiding" was initially grouped in two containers with lids. The second ceramic vessel was covered with a copper lid. It no longer exists leaving only one. Both pottery contained a variety of small objects form a treasure six seals, which range from proto-Elamite period (3100-2750 BC.) To the oldest, the most recent being dated to 2450 BC. AD (First Dynasty of Ur). Therefore it is possible to date these objects, this treasure. Everything included 29 vessels including 11 banded alabaster, mirror, tools and weapons made of copper and bronze, 5 pellets crucibles copper, 4 rings with three gold and a silver, a small figurine of a frog lapis lazuli, gold beads 9, 13 small stones and glazed shard. Metal objects, including tools used may have weight or exchange currency. For some reason we do not know, this treasure has been hidden by its owner but may not get it back. According to Pierre Amiet, it may have been a vassal tribute to the local prince.

A wide variety of shapes and materials

The large number and variety of copper objects testify to the importance of this metal in the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. J-C. The shapes are inspired by the craftsmanship of the neighboring regions such as Luristan and Mesopotamia. The presence of four bronze objects indicates that this alloy began to be controlled by the artisans of the region. However, the small number of objects in precious metals and stones contrast with the richness of the materials used in the Sumerians. Copper came from Oman while lapis lazuli was mined Afghan mountains. The alabaster vases imported objects are either Sistan or Lut desert, the Susian artisans using a coarser material. Such vases were found in large numbers in the city of Ur and show a taste for the exotic which is found until the beginning of the second millennium.

A new cultural momentum

At that time, the Susa region is successively under the aegis of the Mesopotamian kingdoms of Sumer and Akkad. Suse likely begins to emerge from the isolation in which she was to enter a new cultural phase. Although still on the fringes of commercial circuits, a network of exchanges, particularly with regard to materials, is set up with neighboring regions such as Southeast Iran and the Gulf countries, or slightly more distant as the Indus valley.

Bibliography

AMIET × P., Age of inter-Iranian Trade, Paris: Meeting of National Museums, 1986, p.125-126; Fig. 96, 1-9, (Notes and documents of the Museums of France).

AMIET P. Susa 6000 years of history, Paris: Meeting of National Museums, 1988, p.64-65; Fig. 26.

A. BENOIT, The Civilizations of the former Prochre East Paris: Ecole du Louvre, 2003, p.252-253; Fig. 109 (Manuals Ecole du Louvre, Art and Archaeology).

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/07/rosetta-stones-for-deciphered-indus.html

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/07/rosetta-stones-for-deciphered-indus.htmlSargon (2334-2279 BCE) founded the Akkad dynasty which saw inter-regional trade routes, from Dilmun and Magan to Susa and Ebla. Later Naram-Sin (c. 2254-2218 BCE) conquered the cities of Mari and Ebla. Agade of Sargon boasted of gold, tin and lapis lazuli brought from distant lands. A description (Kramer, Samuel Noah, 1958: History Begins at Sumer (London: Thames & Hudson, 289-290) reads:

When Enlil had given Sargon, king of Agade,

Sovereignty over the high lands and over the low lands

...

under the loving guidance of its divine patron Inanna.

Its houses filled with gold, silver, copper, tin, lapis lazuli;

...

The Martu (Amorites) came there, that nomadic people from the west,

'who know not wheat' but who bring oxen and choice sheep;

The folk from Meluhha came, 'the peole of the black lands',

Bearing their exotic products;

The Elamites came and the Sabareans, peoples from the East and the North,

With their bundles like 'beasts of burden'...

In this narrative, Meluhha folk from the black lands were those who required a translator. (Se Shu-ilishu cylinder seal of an Akkadian translator).

King Manistusu commemorates the import of diorite for royal statuary and other stone. Arrival in Sumer ports of boats from Meluhha are said to bring in ivory, copper, precious stones and timber (Leemans, WF, 1960, Foreign trade in the Old Babylonian period as revealed by texts from Southern Mesopotama (Leiden): 27-30). A tamkarum from Umma and his three sons were engaged in the trade of wool, cereals, fruit, sesame oil and copper (Foster, B., 1993, International trade at sargonic Susa, AoF 20 : 62-63). It is possible that this colony of merchants in Susa were seafaring merchants from Meluhha.

"In the third millennium Sumerian texts list copper among the raw materials reaching Uruk from Aratta and all three of the regions Magan, Meluhha and Dilmun are associated with copper, but the latter only as an emporium. Gudea refers obliquely to receiving copper from Dilmun: 'He (Gudea) conferred with the divine Ninzaga (= Enzak of Dilmun), who transported copper like grain deliveries to the temple builder Gudea...' (Cylinder A: XV, 11-18, Englund 1983, 88, n.6). Magan was certainly a land producing the metal, since it is occasionally referred to as the 'mountain of copper'. It may also have been the source of finished bronze objects." (Moorey, Peter Roger Stuart, 1999, Ancient Mesopotamian Materials and industries: the archaeological evidence, Eisenbrauns, p.245).

Tin for Mesopotamia from southeast Asia or Central Asia?

Daniel T. Potts discounts the possibility that Meluhha was the source of tin.

"Tin. The sources of Mesopotamia's tin...have been sought from Southeast Asia to Cornwall. With regard to the former possibility, it has always proved difficult to establish any sort of an archaeological link between Burma, Thailand or any other part of mainland Southeast Asia and the Indian sub-continent, supposing that this was the location of Meluhha from which Gudea (Cyl B XIV.13) claims to have imported tin. As the Indian subcontinent has no tin itself, Meluhha's tin must have been acquired elsewhere and then trans-shipped to Mesopotamia, just as Dilmun's copper was acquired in Magan during the early second millennium BCE. With a view to examining the evidence for a connection between the tin-rich regions of Southeast Asia and the Indus Valley, it is interesting to note that some years ago the claim was made that etched carnelian beads, a particularly diagnostic type fossil of the Harappan civilization, had been found at the early tin-bronze producing site of Ban Chiang in Thailans. This made the likelihood that Meluhhan tin was southeast Asian in origin less far-fetched than previously thought. In fact, however, scholars who have actually seen the Ban Chiang beads have confirmed that they are not Harappan at all, but date rather to the last centuries BCE or first centiries CE when different types of etched carnelian beads, clearly distinct from those of the earlier Harappan period, were manufactured. For the time being, therefore, we should not consider southeast Asia a likely tin source based on this now discredited piece of evidence...Since lapiz lazuli, which certainly originated in Afghanistan (Badakshan), is said by Gudea to have been acquired from Meluhha, it is quite probable that the tin which he received from that country originated in Central Asia as well."(Potts, Daniel T., 1997, Mesopotamian civilization: the material foundations, A&C Black, pp.266-269)

With the recognition of Indus Script hieroglyphs on cire perdue cast Dong Son Bronze drums, the possibility that Meluhha merchants functioned as the intermediaries for the tin from the Tin Belt of Mekong delta should be re-evaluated to validate Gudea's reference to Meluhha in the context of carnelian and tin imports.

Gudea Cylinder B, column 14.13 [Jacobsen , T.,1987, The Harps that once...Sumerian poetry in translation: New Haven (Yale University Press): 437]:

Beside copper, tin, slabs of lapis lazuli,

refined silver and pure Meluhhan carnelian,he set up a huge copper pail...

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/12/tin-road-from-meluhha-to-ancient-near.htmlhttp://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/12/tin-road-from-meluhha-to-ancient-near.html

Reference in some Sumerian texts to acquisition of lapis lazuli and gold from Meluhha suggest that the sea route through the Persian Gulf was used by Meluhha merchants.

Seal of Shu-ilishu showing a Meluhha merchant. The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. http://a.harappa.com/content/shu-ilishus-cylinder-seal

Seal of Shu-ilishu showing a Meluhha merchant. The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. http://a.harappa.com/content/shu-ilishus-cylinder-sealThere are two Indus Script hieroglyphs which signify possible trade transactions on this seal: 1. the goat carried by the Meluhha merchant; and 2. the liquid-container carried by the lady accompanying the merchant.

1. Hieroglyph: mlekh'goat' (Brahui) Rebus: milakkhu'copper' (Pali)

2. Hieroglyph: ranku 'liquid measure' Rebus: ranku'tin'.

If these rebus renderings are valid, the seal may be evidence of trade in copper and tin being negotiated by the Meluhha merchant with the Akkadian merchant. Shu-ilishu lived in Mesopotamia during the Late Akkadian period (ca. 2020 BCE.

Fish glyph on a Susa pot has been decoded as Indus script. See http://bharatkalyan97.

In particular, there is a bronze sculpture excavated in Susa, called Sit Shamshi. "Sunrise (ceremony)" This large piece of bronze shows a religious ceremony. In the center are two men in ritual nudity surrounded by religious furnishings - vases for libations, perhaps bread for offerings, steles - in a stylized urban landscape: a multi-tiered tower, a temple on a terrace, a sacred wood. In the Middle-Elamite period (15th-12th century BC), Elamite craftsmen acquired new metallurgical techniques for the execution of large monuments, statues and reliefs. http://tinyurl.com/

I suggest that this religious ceremony in front of a ziggurat is a sandhyavandanam (morning prayer to the sun) by the metallurgist artisan from Meluhha. The prayer is a veneration of the ancestors whose remains are interned in the ziggurat/stupa. Further researches have to be done on the continuance of similar traditions in the metal smelting areas on Ganga valley, sites such as Lohardiwa, Malhar, and Raja-nal-ki-tila (where Rakesh Tiwari has found evidence of iron smelting in ca. 18th century BCE).

A seal made in Susa with Indus writing

Sceau-cylindre : buffle très étiré et inscription harapéenne (It ain't a buffalo, but a bull)

Stéatite cuite

H. 2.3 cm; Diam. 1.6 cm

Fouilles J. de Morgan

Sb 2425

Near Eastern Antiquities

Richelieu wing

Ground floor

Iran and Susa during the 3rd millennium BC

Room 8

Vitrine 4 : Importations exotiques à Suse, 2600 - 1700 avant J.-C. Suse IVB (2340 - 2100 avant J.-C.).

9801Susa

Susa, Iran; steatite cylinder seal.Cylinder seal carved with an elongated buffalo and a Harappa inscription circa 2600-1700 BCE; Susa, Iran; Fired steatite; H. 2.3 cm; Diam. 1.6 cm; Jacques de Morgan excavations, Susa; Sb 2425; Near Eastern Antiquities; Richelieu wing; Ground floor; Iran and Susa during the 3rd millennium BC; Room 8.

Marshall comments on a Susa cylinder seal: “…the occurrence of the same form of manger on a cylinder-seal of bone found at Susa leaves no doubt, I think, that this seal either came from India in the first instance, or, as is suggested by its very rough workmanship, was engraved for an Indian visitor to Susa by an Elamite workman…One of these five (Mesopotamian seals with Indus script) is a bone roll cylinder found at Susa, apparently in the same strata as that of the tablets in Proto-Elamitic script of the second period of painted ware. Scheil, in Delegation en Perse, vol. xvii, assigns this group of tablets and painted pottery to the period of Sargon of Agade, twenty-eighth century BCE, and some of the tablets to a period as late as the twenty-fourth century. The cylinder was first published by Scheil in Delegation en Perse ii, 129, where no precise field data by the excavator are given. The test is there given as it appears on the seal, and consequently the text is reversed. Louis Delaporte in his Catalogue des Cylindres Orientaux…du Musee du Louvre, vol. I, pl. xxv, No. 15, published this seal from an impression, which gives the proper representation of the inscription. Now, it will be noted that the style of the design is distinctly pre-Sargonic: witness the animal file and the distribution of the text around the circumference of the seal, and not parallel to its axis as on the seals of the Agade and later periods…It is certain that the design known as the animal file motif is extremely early in Sumerian and Elamitic glyptic; in fact is among the oldest known glyptic designs. But the two-horned bull standing over a manger was a design unknown in Sumerian glyptic, except on the small round press seal found by De Sarzec at Telloh and published by Heuzey, Decouvertes en Chaldee, pl. xxx, fig. 3a, and by Delaporte, Cat. I, pl. ii, t.24. The Indus seals frequently represent this same bull or bison with head bent towards a manger…Two archaeological aspects of the Susa seal are disturbing. The cylinder roll seal has not yet been found in the Indus Valley, nor does the Sumero-Elamitic animal file motif occur on any of the 530 press seals of the Indus region. It seems evident, therefore, that some trader or traveler from that country lived at Susa in the pre-Sargonic period and made a roll seal in accordance with the custom of the seal-makers of the period, inscribing it with his own native script, and working the Indian bull into a file design after the manner of the Sumero-Elamitic glyptic. The Susa seal clearly indicated a period ad quem below which this Indian culture cannot be placed, that is, about 2800 BCE. On a roll cylinder it is frequently impossible to determine where the inscription begins and ends, unless the language is known, and that is the case with the Susa seal. However, I have been able to determine a good many important features of these inscriptions and I believe that this text should be copied as follows: The last sign is No. 194 of my list, variant of No. 193, which is a post-fixed determinative, denoting the name of a profession, that is ‘carrier, mason, builder’, ad invariably stands at the end. (The script runs from right to left.)”[Catalogue des cylinders orient, Musee du Louvre, vol. I, pl. xxv, fig. 15. See also J. de Morgan, Prehistoric Man, p. 261, fig. 171; Mem. Del. En Perse, t.ii, p. 129.loc.cit.,John Marshall, 1931, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, Delh, AES, Repr., 2004, p.385; pp. 424-425 Note: Five cylinder seals hav since been found at Mohenjo-daro and Kalibangan.]The seal's chalky white appearance is due to the fired steatite it is made of. Craftsmen in the Indus Valley made most of their seals from this material, although square shapes were usually favored. The animal carving is similar to those found in Harappa works. The animal is a bull with no hump on its shoulders, or possibly a short-horned gaur. Its head is lowered and the body unusually elongated. As was often the case, the animal is depicted eating from a woven wicker manger."

Arrowhead, smelter furnace, native metla, black metal: இறும்பி iṟumpi, n. < எறும்பு. [K. iṟumpu, M. iṟumbu.] Ant; எறும்பு. (யாழ். அக.) இரும்பு irumpu, n. < இரு-மை. cf. செம்பு for செம்மை. [T. inumu, M. irumbu.] 1. Iron, literally, the black metal; கரும்பொன். (தேவா. 209, 3.) 2. Instrument, weapon: ஆயுதம். இரும்பு மேல் விடாது நிற்பார் (சீவக. 782). śanku ‘twelve-fingers’ measure’ (Skt.); Rebus: ‘arrowhead’ (Skt.) kuṭi ‘water carrier’ (Te.) Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṛī f. ‘fireplace’ (H.); krvṛi f. ‘granary (WPah.); kuṛī, kuṛo house, building’(Ku.)(CDIAL 3232) aḍar ‘harrow’; அடர்¹-. 1. To press down; அமுக்குதல். திருவிரலா லடர்த் தான் வல்லரக்கனையும் (தேவா. 509, 8) Rebus: aduru = gan.iyinda tegadu karagade iruva aduru = ore taken from the mine and not subjected to melting in a furnace (Ka.) dula ‘pair’ (Kashmiri); rebus: dul ‘casting’ (Santali).

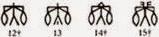

Signs 12 to 15. Indus script: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal').![]()

Identifying Meluhha gloss for parenthesis hieroglyph or ( ) split ellipse: குடிலம்¹ kuṭilam, n. < kuṭila. 1. Bend curve, flexure; வளைவு. (திவா.) (Tamil) In this reading, the Sign 12 signifies a specific smelter for tin metal: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/ kuṭila, 'tin (bronze)metal; kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) [cf. āra-kūṭa, ‘brass’ (Samskritam)

kuTi 'curve' Rebus: kuTila 'bronze' (8 parts copper, 2 parts tin).

खांडा (p. 202) [ khāṇḍā ] A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon).(Marathi)

N. lokhar ʻ bag in which a barber keeps his tools ʼ; H. lokhar m. ʻ iron tools, pots and pans ʼ; -- X

kṣattŕ̊ m. ʻ carver, distributor ʼ RV., ʻ attendant, door- keeper ʼ AV., ʻ charioteer ʼ VS., ʻ son of a female slave ʼ lex. [√

kāṣṭhá n. ʻ piece of wood ʼ ŚBr., °ikā -- f. ʻ small do. ʼ Pañcat.Pa. Pk. kaṭṭha -- n. ʻ wood ʼ, NiDoc. kaṭh́a; Gy. pal. kŭšt ʻ firewood ʼ, eur. kašt m. ʻ piece of wood, timber ʼ; Kt. kåṭ ʻ branch ʼ; Paš. kaṣṭa -- lauṛa ʻ wooden contrivance used in threshing ʼ, Sh. gil. kāṭ m. ʻ wood ʼ, (→ Ḍ kōṭ m.), koh. kāṭhṷ, gur. kāṭṷ, (Lor.) kāṭo ʻ rafter ʼ; K. kāṭh m. ʻ wood ʼ, kôṭh

Ma. kaṭṭila, kaṭṭala, kaṭṭiḷa door frame. ? Ko. kaṭo·ḷ wall of temple compound. Koḍ. kaṭṭoḷe door frame. Ta. kaṭṭil cot, bedstead, couch, sofa; throne. Ma. kaṭṭil bedstead, cot. Ko. kaṭḷ cot. Koḍ. kaṭṭï id. Te. kaṭli litter, dooly. Go. (Tr. Mu.) kaṭṭul (obl. kaṭṭud-, pl. kaṭṭuhk) bed, cot; (numerous dialects) kaṭṭul, kaṭul id. (Voc. 477). Konḍa (Sova dial.) kaṭel(i) cot. Pe. kaṭel id. Manḍ. kaṭel id. Kui (K.) gaṭeli id. Kuwi (Su.) kaṭeli, (P.) gaṭeli, (S.) kateli, (F.) kuteli (i.e. kaṭeli;pl. kutelka, i.e. kaṭelka) id. / Cf. Turner, CDIAL, no. 3781, kháṭvā- cot; no. 3785, khaṭṭi- bier (lex.); also kaṭāha- cot (lex.). From IA: Pa. kaṭeya cot (< Halbi); Kui kaṭe id.; Kur. khaṭībedstead, bed; Malt. kaṭe, káṭi id.(DEDR 1145, 1146)

kháṭvā f. ʻ bedstead ʼ Kauś., °vākā -- f. Pāṇ., °vikā -- Kāś., khaṭṭā -- f., °ṭaka -- m. Apte. [Cf.

(a) Ta. pāppātti butterfly. Ma. pāppātti id. Koḍ. pa·pïli id., moth. Go. pāpe (A. Y. Ch. Ph. S.) butterfly, (Ma.) grasshopper; (Tr.) pāpē butterfly; (W.) phāpe id., grasshopper; (Ph.)phāphe locust (Voc. 2189). Kur. paplā butterfly. Cf. 4084 Pe. pāmi.(b) Ma. pāṟṟa moth. Ka. (Bark.) hānte id.

Tu. pāntè butterfly; (B-K.) pāte, pānte id., moth.(c) Nk. (Ch.) pipuli butterfly. Pa. pilpili id.

Go. (SR.) piprī, (Mu.) pīplī id. (Voc. 2231). Kui pipili moth. / Cf. Halbi pilpili butterfly.

(d) Kuwi (Su. S. Isr.) pubuli, (F.) pūbūli butterfly.(DEDR 4083)

pipīlá m. ʻ ant ʼ RV., °laka -- m. ʻ large black ant ʼ ChUp., pipīˊlikā -- f. ʻ small red ant ʼ AV., pīlaka -- m. ʻ ant ʼ lex. 2. *piphīla -- . 3. *pippīla -- . 4. *pipphīla -- . 5. *pippīḍa -- . 6. *pilīla -- . [Variety of MIA. and NIA. forms for ʻ ant ʼ may be due partly to its (unknown) nonAryan origin (EWA ii 285), partly to contamination with kīṭá -- and kŕ̊mi -- , but mainly to some sort of taboo for a noxious insect. Although there appear to be six main types, not all NIA. forms can be grouped exactly under them]1. Pa. pipīlikā -- , pipillikā -- f. ʻ ant ʼ, Pk. pipīliā -- f., °lia<-> m., pivīliā -- f., Wg. pīmilīˊk, pilīˊk, Gaw. pilo, Tor. pel f.; -- dissim. of p -- p (Wackernagel AiGr i Nachträge 158) or X

pippalaka m. ʻ pin ʼ Car.Pa. pippalaka -- n. (?) ʻ scissors (?) ʼ; Pk. pippala-<-> ʻ knife ʼ; H. pīplā m. ʻ striking part of a sword (about a span from point), end or point of sword, metallic tip of sheath ʼ; M. pĩpiḷā m. ʻ instrument for cutting plaintain leaves (sometimes fastened to a stick) ʼ.(CDIAL 8206)

मैंद (p. 667) [ mainda ] m (A rude harrow or clodbreaker; or a machine to draw over a sown field, a drag.

śaṅkú

Pa. saṅku -- , °uka -- m. ʻ stake, spike, javelin ʼ, Pk. saṁku -- m.; Dm. šaṅ ʻ branch, twig ʼ, šã̄kolīˊ ʻ small do. ʼ, Gaw. šāṅkolīˊ; Kal.rumb. šoṅ (st. šoṅg -- ), urt. šaṅ ʻ branch ʼ; Kho. šoṅg ʻ a kind of shrub with white twigs (?) ʼ; Phal. šōṅ ʻ branch ʼ; P. saṅglā m. ʻ a plank bridge in the hills ʼ; A. xãkāli ʻ a kind of fishing spear ʼ; Si. aku -- va ʻ stake ʼ. -- X

Herbin Nancie's note on the Louvre Museum websie:

This cylinder seal, carved with a Harappan inscription, originated in the Indus Valley. It is made of fired steatite, a material widely used by craftsmen in Harappa. The animal - a bull with no hump on its shoulders - is also widely attested in the region. The seal was found in Susa, reflecting the extent of commercial links between Mesopotamia, Iran, and the Indus.

A seal made in Meluhha

The language of the inscription on this cylinder seal found in Susa reveals that it was made in Harappa in the Indus Valley. In Antiquity, the valley was known as Meluhha. The seal's chalky white appearance is due to the fired steatite it is made of. Craftsmen in the Indus Valley made most of their seals from this material, although square shapes were usually favored. The animal carving is similar to those found in Harappan works. The animal is a bull with no hump on its shoulders, or possibly a short-horned gaur. Its head is lowered and the body unusually elongated. As was often the case, the animal is depicted eating from a woven wicker manger.

Trading links between the Indus, Iran, and Mesopotamia

This piece can be compared to another circular seal carved with a Harappan inscription, also found in Susa. The two seals reveal the existence of trading links between this region and the Indus valley. Other Harappan objects have likewise been found in Mesopotamia, whose sphere of influence reached as far as Susa.

The manufacture and use of the seals

Cylinder seals were used mainly to protect sealed vessels and even doors to storage spaces against tampering. The surface of the seal was carved. Because the seals were so small, the artists had to carve tiny scenes on a material that allowed for fine detail. The seal was then rolled over clay to produce a reverse print of the carving. Some cylinder seals also had handles.

Bibliography

Amiet Pierre, L'Âge des échanges inter-iraniens : 3500-1700 av. J.-C., Paris, Éditions de la Réunion des musées nationaux, 1986, coll. "Notes et documents des musées de France", p. 143 et p. 280, fig. 93.Borne interactive du département des Antiquités orientales.

Les cités oubliées de l'Indus : archéologie du Pakistan,

cat. exp. Paris, Musée national des arts asiatiques, Guimet,

16 novembre 1988-30 janvier 1989, sous la dir. de Jean-François Jarrige, Paris, Association française d'action artistique, 1988, pp. 194-195, fig. A5.

http://www.louvre.fr/en/oeuvre-notices/cylinder-seal-carved-elongated-buffalo-and-harappan-inscription

Gensheimer, TR, 1984, The role of shell in Mesopotamia: evidence for trfade exxchange with Oman and the Indus Valley, in: Paleorient, Vol. 10, Numero 1, pp. 65-73

http://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_1984_num_10_1_4350

http://www.archive.org/

http://www.archive.org/

TR Gensheimer reports:"Turbinella pyrum, has a much more massive columella and medium to large shells can easily produce a cylinder that is 30 mm in diameter and upto 50 mm in length. A preliminary study of the large cylinder seals from the graves at Ur suggess that they could only have been made from T. pyrum. Other isolated examples of such large shell cylinder seals are reported from Tepe Gawra and Susa and together they indicate that Mesopotamian workshops were obtaining T.pyrum columella or rough cylinders through trade contacts with the Indus Valley. Prior to this availability, large shell cylinders were apparently made by joining sections of shell together as is seen in cylinder seal #U-9907 from the Royal Cemetery." http://www.persee.fr/doc/paleo_0153-9345_1984_num_10_1_4350

Kenoyer, JM 1985, Shell working industries of the Indus civilisation: An archaeological and ethnographic perspective, PhD thesis, UC Berkeley, 363; Woolley L, 1934, Excavations at Ur 1931-34. Antiquities Journal 14.4, Pl. 99a

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

Sarasvati Research Center

October 1, 2015