Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/p8hvgfp

Hieroglyphs signify proclamations in Indus Script Corpora. Artifacts in the round also occur with hieroglyphs to signify proclamations of metalwork competence of the artisans and seafaring merchants of Meluhha. One remarkable artifact of the civilization is a copper anthropomorph with characteristic components of hieroglyph-multiplex as hypertext. This hypertext is deciphered in Indus Script cipher as copper merchant's helper. The hieroglyph for a proclamation is sangada'joined animal parts' Rebus: sangara'proclamation'. This decipherment explains why such unique hieroglyph-multiplexes are created and presented as Indus Script Corpora catalogus catalogorum of metalwork.

Hieroglyphs signify proclamations in Indus Script Corpora. Artifacts in the round also occur with hieroglyphs to signify proclamations of metalwork competence of the artisans and seafaring merchants of Meluhha. One remarkable artifact of the civilization is a copper anthropomorph with characteristic components of hieroglyph-multiplex as hypertext. This hypertext is deciphered in Indus Script cipher as copper merchant's helper. The hieroglyph for a proclamation is sangada'joined animal parts' Rebus: sangara'proclamation'. This decipherment explains why such unique hieroglyph-multiplexes are created and presented as Indus Script Corpora catalogus catalogorum of metalwork.

Orthographic style of creating anthropomorph (sangaḍa 'joined animal parts') is a characteristic feature of Indus Script cipher. Examples are: copper anthropomorphs found all over North India, terracotta figurines of felines or bulls/bovines as anthropomorphs, i.e. attribution of a human form to animal motifs. Hieroglyph-multiplex sangaḍa Rebus: sangara is a proclamation, an orthographic representation in Indus Script Cipher, a metalwork catalogue.

Consistent with the Indus Script Corpora as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork, the hieroglyph-multiplexes on the anthropomorphs may be deciphered as part of a metalwork lexis in Meluhha.

Медь [Med'] (Russian, Slavic) 'copper' gloss is cognate with mē̃ḍ 'iron' (Munda) meḍ 'iron' (Ho.) . The early semantics of the Meluhha word meḍ is likely to be 'copper metal'. Rebus: मेढ meḍh 'helper of merchant'. Seafaring merchants of Meluhha !

The anthropomorphs are a proclamation (Rebus: sangara-- hieroglyph: sangaḍa 'joined animals or animal parts'), ancient professional calling cards on ancient forms of tablets of metalwork competence.

Copper anthropomorphs found in significant numbers are of two types: Type 1: (Without any further texts or inscription) A body of a standing person (with head shaped like a sivalinga) with arms signified by the curved horns of a ram. Type 2. The same form as Type 1 but with an added hieroglyph: fish.

Indus Script Cipher explains hieroglyphs as hypertexts on the copper anthropomorphs

mē̃ḍh 'antelope, ram'; Rebus: mē̃ḍ'iron' (Mu.) meḍ iron (Ho.) Rebus:मेढ meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakritam. Desinamamala. Hemacandra) medh a sacrifice (Samskritam)

meḍ 'body' Rebus: mē̃ḍ 'iron'

meNḍha'ram' Rebus: mē̃ḍ 'iron'

aya'fish' Rebus: aya'iron'ayas'metal'

The body of a standing person with the legs drawn apart may also signify a warrior. baTa 'warrior' Rebus: baTa'furnace'.

Thus, the copper anthropomorphs signify metalwork, iron furnaces. The word meD is explained as 'iron' in Munda and Ho. The same word is explained in Slavic languages as 'copper'. Such transferance of signifying metals by th same gloss also occurs for the word loh which is semantically explained as copper or iron or metal, in general.

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic). Corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry.

Used in most of the Slavic and Altaic languages.

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz'] Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

Kòper Kashubian

Бакар [Bakar] Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med'] Russian

Meď Slovak

Baker Slovenian

Бакар [Bakar] Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainianhttp://www.vanderkrogt.net/elements/element.php?sym=Cu ![]()

The Sheorajpur anthropomorph (348 on Plate A) has a 'fish' hieroglyph incised on the chest ![]() Title / Object:anthropomorphic sheorajpurFund context:Saipai, Dist. KanpurTime of admission:1981Pool:SAI South Asian ArchaeologyImage ID:213 101Copyright:Dr Paul Yule, HeidelbergPhoto credit:Yule, Metalwork of the Bronze in India, Pl 23 348 (dwg)

Title / Object:anthropomorphic sheorajpurFund context:Saipai, Dist. KanpurTime of admission:1981Pool:SAI South Asian ArchaeologyImage ID:213 101Copyright:Dr Paul Yule, HeidelbergPhoto credit:Yule, Metalwork of the Bronze in India, Pl 23 348 (dwg)

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/composite-copper-alloy-anthropomorphic.html

![]()

![]()

![]() Fig. 2: Anthropomorphic figures from the Indian Subcontinent. 10 type I, Saipai, Dist. Etawah, U.P.; 11 type I, Lothal, Dist. Ahmedabad,Guj.; 12 type I variant, Madarpur, Dist. Moradabad, U.P.; 13 type II, Sheorajpur, Dist. Kanpur, U.P.; 14 miscellaneous type, Fathgarh,

Fig. 2: Anthropomorphic figures from the Indian Subcontinent. 10 type I, Saipai, Dist. Etawah, U.P.; 11 type I, Lothal, Dist. Ahmedabad,Guj.; 12 type I variant, Madarpur, Dist. Moradabad, U.P.; 13 type II, Sheorajpur, Dist. Kanpur, U.P.; 14 miscellaneous type, Fathgarh,

![]() Saipal, Dist. Etawah, UP. Anthropomorph, type I. 24.1x27.04x0.76 cm., 1270 gm., both sides show a chevron patterning, left arm broken off (Pl. 22, 337). Purana Qila Coll. Delhi (74.12/4) -- Lal, BB, 1972, 285 fig. 2d pl. 43d

Saipal, Dist. Etawah, UP. Anthropomorph, type I. 24.1x27.04x0.76 cm., 1270 gm., both sides show a chevron patterning, left arm broken off (Pl. 22, 337). Purana Qila Coll. Delhi (74.12/4) -- Lal, BB, 1972, 285 fig. 2d pl. 43d

![]() From Lothal was reported a fragmentary Type 1 anthropomorph (13.0 pres. X 12.8 pres. X c. 0.08 cm, Cu 97.27%, Pb 2.51% (Rao), surface ptterning runs lengthwise, lower portion slightly thicker than the edge of the head, 'arms' and 'legs' broken off (Pl. 1, 22)-- ASI Ahmedabad (10918 -- Rao, SR, 1958, 13 pl. 21A)

From Lothal was reported a fragmentary Type 1 anthropomorph (13.0 pres. X 12.8 pres. X c. 0.08 cm, Cu 97.27%, Pb 2.51% (Rao), surface ptterning runs lengthwise, lower portion slightly thicker than the edge of the head, 'arms' and 'legs' broken off (Pl. 1, 22)-- ASI Ahmedabad (10918 -- Rao, SR, 1958, 13 pl. 21A)

![]()

http://www.clevelandart.org/art/2004.31 Anthropomorphic Figure, c. 1500 - 1300 BC

India, Bronze Age. copper, Overall - h:23.50 w:36.50 d:0.50 cm (h:9 1/4 w:14 5/16 d:3/16 inches). Norman O. Stone and Ella A. Stone Memorial Fund 2004.31

![]()

![knives]()

http://archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/19th-century-paradigms-5

Consistent with the Indus Script Corpora as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork, the hieroglyph-multiplexes on the anthropomorphs may be deciphered as part of a metalwork lexis in Meluhha.

Медь [Med'] (Russian, Slavic) 'copper' gloss is cognate with mē̃ḍ 'iron' (Munda) meḍ 'iron' (Ho.) . The early semantics of the Meluhha word meḍ is likely to be 'copper metal'. Rebus: मेढ meḍh 'helper of merchant'. Seafaring merchants of Meluhha !

The anthropomorphs are a proclamation (Rebus: sangara-- hieroglyph: sangaḍa 'joined animals or animal parts'), ancient professional calling cards on ancient forms of tablets of metalwork competence.

Copper anthropomorphs found in significant numbers are of two types: Type 1: (Without any further texts or inscription) A body of a standing person (with head shaped like a sivalinga) with arms signified by the curved horns of a ram. Type 2. The same form as Type 1 but with an added hieroglyph: fish.

Indus Script Cipher explains hieroglyphs as hypertexts on the copper anthropomorphs

mē̃ḍh 'antelope, ram'; Rebus: mē̃ḍ'iron' (Mu.) meḍ iron (Ho.) Rebus:मेढ meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakritam. Desinamamala. Hemacandra) medh a sacrifice (Samskritam)

meḍ 'body' Rebus: mē̃ḍ 'iron'

meNḍha'ram' Rebus: mē̃ḍ 'iron'

aya'fish' Rebus: aya'iron'ayas'metal'

The body of a standing person with the legs drawn apart may also signify a warrior. baTa 'warrior' Rebus: baTa'furnace'.

Thus, the copper anthropomorphs signify metalwork, iron furnaces. The word meD is explained as 'iron' in Munda and Ho. The same word is explained in Slavic languages as 'copper'. Such transferance of signifying metals by th same gloss also occurs for the word loh which is semantically explained as copper or iron or metal, in general.

Used in most of the Slavic and Altaic languages.

— Slavic

Мед [Med] BulgarianBakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz'] Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

Kòper Kashubian

Бакар [Bakar] Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med'] Russian

Meď Slovak

Baker Slovenian

Бакар [Bakar] Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian

Title / Object:anthropomorphic sheorajpurFund context:Saipai, Dist. KanpurTime of admission:1981Pool:SAI South Asian ArchaeologyImage ID:213 101Copyright:Dr Paul Yule, HeidelbergPhoto credit:Yule, Metalwork of the Bronze in India, Pl 23 348 (dwg)

Title / Object:anthropomorphic sheorajpurFund context:Saipai, Dist. KanpurTime of admission:1981Pool:SAI South Asian ArchaeologyImage ID:213 101Copyright:Dr Paul Yule, HeidelbergPhoto credit:Yule, Metalwork of the Bronze in India, Pl 23 348 (dwg)One anthropomorph had fish hieroglyph incised on the chest of the copper object, Sheorajpur, upper Ganges valley, ca. 2nd millennium BCE, 4 kg; 47.7 X 39 X 2.1 cm. State Museum, Lucknow (O.37) Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo, ayas ‘metal. Thus, together read rebus: ayo meḍh ‘iron stone ore, metal merchant.’

A remarkable legacy of the civilization occurs in the use of ‘fish‘ sign on a copper anthropomorph found in a copper hoard. This is an apparent link of the ‘fish’ broadly with the profession of ‘metal-work’. The ‘fish’ sign is apparently related to the copper object which seems to depict a ‘fighting ram’ symbolized by its in-curving horns. The ‘fish’ sign may relate to a copper furnace. The underlying imagery defined by the style of the copper casting is the pair of curving horns of a fighting ram ligatured into the outspread legs (of a warrior).

Hieroglyhph: eraka 'wing' Rebus: eraka, arka 'copper'.In 2003, Paul Yule wrote a remarkable article on metallic anthropomorphic figures derived from Magan/Makkan, i.e. from an Umm an-Nar period context in al-Aqir/Bahla' in the south-western piedmont of the western Hajjar chain. "These artefacts are compared with those from northern Indian in terms of their origin and/or dating. They are particularly interesting owing to a secure provenance in middle Oman...The anthropomorphic artefacts dealt with...are all the more interesting as documents of an ever-growing body of information on prehistoric international contact/influence bridging the void between south-eastern Arabia and South Asia...Gerd Weisgerber recounts that in winter of 1983/4...al-Aqir near Bahla' in the al-Zahirah Wilaya delivered prehistoric planoconvex 'bun' ingots and other metallic artefacts from the same find complex..."

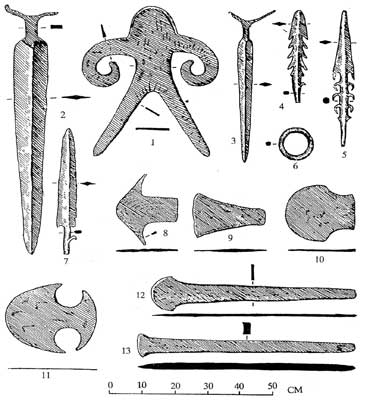

In the following plate, Figs. 1 to 5 are anthropomorphs, with 'winged' attributes. The metal finds from the al-Aqir wall include ingots, figures, an axe blade, a hoe, and a cleaver (see fig. 1, 1-8), all in copper alloy.

Fig. 1: Prehistoric metallic artefacts from the Sultanate of Oman: 1-8 al-Aqir/Bahla'; 9 Ra's al-Jins 2, building vii, room 2, period 3 (DA 11961) "The cleaver no. 8 is unparalleled in the prehistory of the entire Near East. Its form resembles an iron coco-nut knife from a reportedly subrecent context in Gudevella (near Kharligarh, Dist. Balangir, Orissa) which the author examined some years ago in India...The dating of the figures, which command our immediate attention, depends on two strands of thought. First, the Umm an-Nar Period/Culture dating mentioned above, en-compasses a time-space from 2500 to 1800 BC. In any case, the presence of “bun“ ingots among the finds by nomeans contradicts a dating for the anthropomorphic figures toward the end of the second millennium BC. Since these are a product of a simple form of copper production, they existed with the beginning of smelting in Oman. The earliest dated examples predate this, i.e. the Umm an-NarPeriod. Thereafter, copper continues to be produced intothe medieval period. Anthropomorphic figures from the Ganges-Yamuna Doab which resemble significantly theal-Aqir artefacts (fig. 2,10-15) form a second line of evidence for the dating. To date, some 21 anthropomorphsfrom northern India have been published." (p. 539; cf. Yule, 1985, 128: Yule et al. 1989 (1992) 274: Yule et al 2002. More are known to exist, particularly from a large hoard deriving from Madarpur.)

Fig. 2: Anthropomorphic figures from the Indian Subcontinent. 10 type I, Saipai, Dist. Etawah, U.P.; 11 type I, Lothal, Dist. Ahmedabad,Guj.; 12 type I variant, Madarpur, Dist. Moradabad, U.P.; 13 type II, Sheorajpur, Dist. Kanpur, U.P.; 14 miscellaneous type, Fathgarh,Dist. Farrukhabad, U.P.; 15 miscellaneous type, Dist. Manbhum, Bihar.

The anthropomorph from Lothal/Gujarat (fig. 2,11), from a layer which its excavator dates to the 19 th century BCE. Lothal, phase 4 of period A, type 1. Some anthropomorphs were found stratified together with Ochre-Coloured Pottery, dated to ca. 2nd millennium BCE. Anthropomorph of Ra's al-Jins (Fig. 1,9) clearly reinforces the fact that South Asians travelled to and stayed at the site of Ra's al-Jins. "The excavators date the context from which the Ra’s al-Jins copper artefact derived to their period III, i.e. 2300-2200 BCE (Cleuziou & Tosi 1997, 57), which falls within thesame time as at least some of the copper ingots which are represented at al-Aqir, and for example also in contextfrom al-Maysar site M01...the Franco-Italian teamhas emphasized the presence of a settled Harappan-Peri-od population and lively trade with South Asia at Ra's al-Jins in coastal Arabia. (Cleuziou, S. & Tosi, M., 1997, Evidence for the use of aromatics in the early Bronze Age of Oman, in: A. Avanzini, ed., Profumi d'Arabia, Rome 57-81)."

"In the late third-early second millennium, given the presence of a textually documented 'Meluhha village' in Lagash (southern Mesopotamia), one cannot be too surprised that such colonies existed 'east of Eden' in south-eastern Arabia juxtaposed with South Asia. In any case, here we encounter yet again evidence for contact between the two regions -- a contact of greater intimacy and importance than for the other areas of the Gulf."(Paul Yule, 2003, Beyond the pale of near Eastern Archaeology: Anthropomorphic figures from al-Aqir near Bahla' In: Stöllner, T. (Hrsg.): Mensch und Bergbau Studies in Honour of Gerd Weisgerber on Occasion of his 65th Birthday. Bochum 2003, pp. 537-542).

See: Weisgerber, G., 1988, Oman: A bronze-producing centre during the 1st half of the 1st millennium BCE, in: J. Curtis, ed., Bronze-working centres of western Asia, c. 1000-539 BCE, London, 285-295.

With curved horns, the ’anthropomorph’ is a ligature of a mountain goat or markhor (makara) and a fish incised between the horns. Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. At Sheorajpur, three anthropomorphs in metal were found. (Sheorajpur, Dt. Kanpur. Three anthropomorphic figures of copper. AI, 7, 1951, pp. 20, 29).

One anthropomorph had fish hieroglyph incised on the chest of the copper object, Sheorajpur, upper Ganges valley, ca. 2nd millennium BCE, 4 kg; 47.7 X 39 X 2.1 cm. State Museum, Lucknow (O.37) Typical find of Gangetic Copper Hoards. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (G.)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍh ‘helper of merchant’ (Gujarati) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda) ayo ‘fish’ Rebus: ayo, ayas ‘metal. Thus, together read rebus: ayo meḍh ‘iron stone ore, metal merchant.’

A remarkable legacy of the civilization occurs in the use of ‘fish‘ sign on a copper anthropomorph found in a copper hoard. This is an apparent link of the ‘fish’ broadly with the profession of ‘metal-work’. The ‘fish’ sign is apparently related to the copper object which seems to depict a ‘fighting ram’ symbolized by its in-curving horns. The ‘fish’ sign may relate to a copper furnace. The underlying imagery defined by the style of the copper casting is the pair of curving horns of a fighting ram ligatured into the outspread legs (of a warrior).

An elaboration of the copper anthropomorph occurs on a Haryana artifact. An animal-headed anthropomorph http://www.business-standard.com/article/specials/naman-ahuja-is-mastering-the-art-of-reaching-out-114092501180_1.html The hieroglyphs are: 1. crocodile; 2. one-horned young bull; 3. anthropomorph (with ram's curved horns, body and legs resembling a person) Indus Script cipher readings of hieroglyph-multiplexes on this artifact are: 1. meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: meḍ 'iron' (Ho.) 2. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' baTa 'warrior' Rebus: baTa 'furnace' 3. khoṇḍ, kõda 'young bull-calf' Rebus: kũdār ‘turner’. कोंद kōnda ‘engraver, lapidary setting or infixing gems’ (Marathi) 4. kāru 'crocodile' (Telugu) Rebus: kāruvu 'artisan' (Telugu) khār 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri) http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/composite-copper-alloy-anthropomorphic.html |

|---|

From Lothal was reported a fragmentary Type 1 anthropomorph (13.0 pres. X 12.8 pres. X c. 0.08 cm, Cu 97.27%, Pb 2.51% (Rao), surface ptterning runs lengthwise, lower portion slightly thicker than the edge of the head, 'arms' and 'legs' broken off (Pl. 1, 22)-- ASI Ahmedabad (10918 -- Rao, SR, 1958, 13 pl. 21A)

From Lothal was reported a fragmentary Type 1 anthropomorph (13.0 pres. X 12.8 pres. X c. 0.08 cm, Cu 97.27%, Pb 2.51% (Rao), surface ptterning runs lengthwise, lower portion slightly thicker than the edge of the head, 'arms' and 'legs' broken off (Pl. 1, 22)-- ASI Ahmedabad (10918 -- Rao, SR, 1958, 13 pl. 21A)The extraordinary presence of a Lothal anthropomorph of the type found on the banks of River Ganga in Sheorajpur (Uttar Pradesh) makes it apposite to discuss the anthropomorph as a Meluhha hieroglyph, since Lothal is reportedly a mature site of the civilization which has produced nearly 7000 inscriptions (what may be called Meluhha epigraphs, almost all of which are relatable to the bronze age metalwork of India).

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2014/01/meluhha-hieroglyphs-snarling-iron-of.html

http://www.clevelandart.org/art/2004.31 Anthropomorphic Figure, c. 1500 - 1300 BC

India, Bronze Age. copper, Overall - h:23.50 w:36.50 d:0.50 cm (h:9 1/4 w:14 5/16 d:3/16 inches). Norman O. Stone and Ella A. Stone Memorial Fund 2004.31

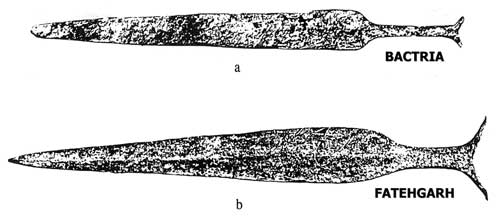

Copper hoards from the Gangetic valley, India. Of the type not found in Bactria.

Antennae-hilted swords of copper.

http://archaeologyonline.net/artifacts/19th-century-paradigms-5

![Image result for anthropomorphic indus]() Anthropomorphic figure

Anthropomorphic figure

India

Indus civilization (ca. 3300-1300 B.C.)

ca. 1500 B.C.

Sculpture in bronze

H 19 cm x W 30,50 http://www.axel-vervoordt.com/en/art-antiques/ancient-oriental/pre-columbian/#!/anthropomorphic-figure

Indus civilization (ca. 3300-1300 B.C.)

ca. 1500 B.C.

Sculpture in bronze

H 19 cm x W 30,50 http://www.axel-vervoordt.com/en/art-antiques/ancient-oriental/pre-columbian/#!/anthropomorphic-figure

Anthropomorphic figures formed from copper. Northern India, Doab region, circa 1500-1200 BCE

"Two composite anthropomorphic / animal figurines from Harappa. Whether or not the masks/amulets and attachable water buffalo horns were used in magic or other rituals, unusual and composite animals and anthropomorphic/animal beings were clearly a part of Indus ideology. The ubiquitous "unicorn" (most commonly found on seals, but also represented in figurines), composite animals and animals with multiple heads, and composite anthropomorphic/animal figurines such as the seated quadruped figurines with female faces, headdresses and tails offer tantalizing glimpses into a rich ideology, one that may have been steeped in mythology, magic, and/or ritual transformation. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D) of the larger figurine: 3.5 x 7.1 x 4.8 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)" Source: http://www.harappa.com/figurines/72.html

Aligrama, Swat

1600 - 500 BC

The Gandhara (or Swat) grave culture emerged ca. 1600 BC, and flourished in Gandhara, Pakistan from 1500 BC to 500 BC. Simply made terracotta figurines were buried with the pottery, and other items are decorated with simple dot designs. Horse remains were found in at least one burial.

The Gandhara grave people have been conjecturally associated by certain Indian archeologists with early Indo-Aryan speakers, and the Indo-Aryan migration into South Asia, which cross-bred with indigenous elements of the remnants of the Indus Valley Civilization (Cemetery H). There is no evidence that they spoke an Indo-Aryan language.

Anthropomorph bull. Man's face on a terracotta bull. http://www.harappa.com/figurines/1.html A group of terracotta figurines from Harappa "After many decades of research, the Indus Civilization is still something of an enigma -- an ancient civilization with a writing system that still awaits convincing decipherment, monumental architecture whose function still eludes us, no monumental art, a puzzling decline, and little evidence of the identity of its direct descendants. In a civilization extending over an area so vast, we expect to find monumental art and/or architectural symbols of power displaying the names of the powerful. Instead, we find an emphasis on small, elegant art and sophisticated craft technology. In this so-called "faceless civilization," three-dimensional representations of living beings in the Harappan world are confined to a few stone and bronze statues and some small objects crafted in faience, stone, and other materials - with one important exception. Ranging in size from slightly larger than a human thumb to almost 30 cm. (one foot) in height, the anthropomorphic and animal terracotta figurines from Harappa and other Indus Civilization sites offer a rich reflection of some of the Harappan ideas about representing life in the Bronze Age. (Photograph by Georg Helmes)."

http://www.harappa.com/figurines/49.html Feline figurine with "coffee bean" eyes from Harappa. "It has been suggested that some feline figurines have anthropomorphic facial features. While features such as "coffee bean" eyes are unusual, the facial features of many animal figurines are stylized. Such features as beards are not necessarily anthropomorphic features, but may represent either tigers’ ruffs or lions’ manes. Variations in facial features may represent differences in wild felines rather than anthropomorphization. Approximate dimensions (W x H(L) x D): 4.1 x 12.2 x 6.1 cm. (Photograph by Richard H. Meadow)"

Abhik Ghosh, PhD

Department of Anthropology, Panjab University

Department of Anthropology, Panjab University

Keywords

chotanagpur, ethno-archaeology, india, iron, prehistory, rock art

Citation

A Ghosh. Prehistory Of The Chotanagpur Region Part 4: Ethnoarchaeology, Rock Art, Iron And The Asuras. The Internet Journal of Biological Anthropology. 2008 Volume 3 Number 1.

Abstract

This paper discusses for interrelated aspects of prehistoric and proto-historic cultures from the Chotanagpur region of India. It begins by looking at the ethno-archaeological data from the region. Then, it goes on to discuss the various kinds of rock art sites in the entire region. Third, it looks at the iron sites in the region. Finally, it looks at the phenomenon often described as Asura sites or Asura cultures in the region. All these elements would be studied to glean important facts regarding the prehistoric sites in the region and to attempt to find ways to understand their cultures. It is hoped that this paper would generate many studies that expand the scope of this paper to incorporate more data and many more ideas for a further and better understanding of these early cultures.

Introduction

In this continuing saga of human expansion in the Chotanagpur region, it is necessary to note the fact that there are many communities in the region which have lifestyles and cultures from which we may learn about the earlier pre-historic and proto-historic communities of the region. Archaeologists practicing this arena of knowledge are called ethno-archaeologists. Through the works of a number of ethno-archaeologists, the first section of the paper will attempt to delineate the variety of cultural models that will attempt to make sense of the Chotanagpur prehistoric material from the past[123].

The conclusions from this material will then lead us into the study of the symbols and findings of the huge number of rock art material from the region. This will add on to our knowledge of the way early cultures thought about their environments and their lives. It would add on the knowledge of ethno-zoology/palaeo-zoology to the earlier data of the region. Some of the data is available in the adjoining states of Orissa, Madhya Pradesh and West Bengal, rather than solely in the heartland of the Bihar/Jharkhand region.

The complexity and variety of iron-using and iron-making as well as iron-extracting communities in India is amazingly diverse. In fact, there are so many kinds of cultures that are involved in these processes that it would be entirely wrong to say that there has ever been a true Iron Age community in India, and definitely not in the Chotanagpur region. These facts are illustrated through the sites found showing iron usage.

Leading through this morass of data of the Chotanagpur region, finally, I shall describe the complexity of information available regarding the Asuras of the region. The Asuras have been studied ethno-archaeologically, they have been part of the iron-using and iron-making part of Chotanagpur culture and, it is possible, they have been instrumental in forming some of the first states in the region. The data available on the Asuras will thus be discussed in detail throwing light on the various issues that emerge.

It is hoped that this paper will thus help us in formulating a better idea of the cultures that lived during the prehistoric and proto-historic period in Chotanagpur.

The Data From Ethno-Archaeology

It must be stated here that often archaeologists have mistaken assumptions regarding what constitutes a tribe. This is aided and abetted by the fact that even today anthropologists have also defined tribes differently. Further, the term ‘tribe’ may be used as an econo-political type in an evolutionary hierarchy of societies[4], or it may be used as a socio-cultural type, whether or not evolutionarily connected to an earlier era. For details of the real problems that it generates, it would be useful to look at the concept as a really occurring cluster of types some of which may or may not be present[5].

The snake cults in the region have been discussed many times by others. There seem to be a snake in the rock carvings found in the excavation of Sarjamhatu medium irrigation scheme near Chaibasa. Further, Rajgir has many items which show snake being a venerated item dated to the third century BC. This continues into the Manasa cult in Bengal. Such Naga figures also exist in Vaisali and Kumrahar in Bihar between 2nd century BC to the 1st century AD. A Naga-Panchami festival is still held in July-August in Bihar[6].

R. P. Sharma[7], in this context, argues out a gradual differentiation of peasantry from an earlier tribal ancestry in the Indian context. However, due to a mixing up of the term ‘tribe’ with other categories which may or may not be associated with it, his claims fall flat. Further, he has also not noted, that perhaps what we have begun to call tribes may not have come into existence until after the state came into existence in the region and a group of people was forced to create an identity of its own, in opposition to state forces and definitely because of it[8]. Even if it happened in a limited number of cases, it is still a valid enough possibility for it not to be ignored.

Bhattacharya[9] comments on the terracotta snake found from Chirand and links it up with the cultural aspects of the Bauris of Bankura district in West Bengal. Their worship of the cult of Manasa is symbolically associated with their linkage to the king, and hence to power, prestige and economic advantages.

Such studies have also been conducted very fruitfully in great detail on the Kanjars of Uttar Pradesh by Malti Nagar and V.N. Misra[10] and on the Van Vagris of Rajasthan by V.N. Misra[11].

As far as the metallurgy of the region is concerned, many authors have tried to link up the metallurgy of local indigenous communities with the meals found from archaeological sites. Ray, et al.[12] and Ray[13] have found that the Sithrias caste practise a brass working in an indigenous style which is remarkably similar to the brass artifacts found at Kuanr.

In this regard, the structure of the indigenous iron-making communities as studied by Sarkar[14] is of great importance. He divides the art of the blacksmith into two sections – the removal of iron from the ore or smelting, and the fashioning of iron into other products or forging. He sees, often, that the two are supported by two different groups of people. Sometimes, the two are looked upon differently by local populations, one being kept lower than the other in the hierarchy. The Agaria are a tribal community that have inhabited the Central Indian region and their name comes from the word aag or fire. The Agaria were less numerous in the Ranchi plateau but had become incorporated with the Asurs of the region. Lohars are a group of communities who work on iron and they may have either a tribal or non-tribal origin. They were often secluded and were of a low caste designation. He was required widely and most villages had at least one Lohar . In the Santal Parganas, they trace their origin either from Birbhum, Manbhum or Burdwan, as well as from Magahi.

It seems that in these areas, general use of iron had not started in the early historical period. Thus, though mining and extraction of the metal was important to the states of the period, its use seems to have remained unmentioned. In fact, the word Munda (as a tribe of this region is called) also means a ball of iron. Tribal groups were mostly relegated to iron extraction and often the ores were found in the forested and hilly regions which were claimed to be traditionally their habitats. The iron of Bengal was famed for its malleability. In Birbhum, the iron smelters included Santals, Bonyahs and Kols. Such activity was part-time and seasonal and was combined with agriculture. ‘Iron earth’ was obtained either from the surface or by digging small shafts under the ground. The extraction was normally in the open, but the smelting houses were like blacksmith’s workshops and run by Kol-lohars , who were a non-agricultural group. They were in contact with iron merchants and received advances from them. There were also others who sold it to others and carried to iron markets called aurangs [15].

In Bihar and Jharkhand, such iron-smelting was an ancient craft in the Rajmahal Hills, Palamu-Ranchi and Dhalbhum-Singhbhum regions. Many tribals participated. In the Rajmahals it was the Kols, who were migrants with hunting as a subsidiary occupation or even some agriculture. Then, there were the Agaria/Asurs of Ranchi and Chotanagpur, the Cheros and Bhoktas of Palamau, Hos and Kharias of Dhalbhum, Korahs and Nyahs of Bhagalpur district, often on their way to becoming settled agriculturists. They handed over iron to the Lohars for cash. In the Rajmahal hills and Santal parganas there were larger forges and indications of organized, large-scale and long-term smelting of iron also, leading to functional specialization and blacksmith colonies. In Orissa, Patuas and Juangs created iron of the best quality. In Bonai it was done by the Kols, probably from Singhbhum. It was a subsidiary craft practiced by Sambalpur villagers along with agriculture. In Darjeeling, iron was manufactured but not smelted by the Kamins. In Khasia hills it was done by the Garos, Khasis and Nagas, though this region had features different from that of the Chotanagpur[15].

Thus, over time, the blacksmith became part of the caste hierarchy and often rose in it through the process of Sanskritization while the iron-smelters remained lower in the hierarchy. While the Lohars and Lohras were allowed to become smiths in the villages of Oraons, the Agarias were not even allowed to use Oraon wells. Myths exist in the whole region, which separate the Gonds, the Santals, Bhumij, Ho or Lohars from the iron-smelting tribes and they involve the invoking of gods (like the Sun) to destroy the Asurs/Agarias. Thus, while these tribes worship the sun the Asur-Agarias do not. The Kherwars, Cheros and Bhoktas similarly removed the Bhurs and Marhs to Singhrauli or Kaimur where they were smelting iron. One group of Kols, under the influence of the Oraons, started worshipping the sun, doing agriculture and left iron-smelting. Another group ran from there, hid in the Bonai hills and started iron-smelting. Women in tribal communities like the Agaria or Kol were allowed to work in the smelting process while the Lohars did not allow women in their work. Such practices recreated this social division between them. As Lohars from outside kept adjusting to the communities they stayed with, they also became more and more confused in the adoption of these new cultural mores[15].

Tripathi and Mishra[16] also studied the iron-making communities in detail and found out that the Mahuli Agarias produced white iron which was used for preparing weapons. A high grade iron was also produced by the Parsa group of Agarias as well as the Kamis of Darjeeling.

Shahida Ansari[1718] has explained certain specific features of hunter-gatherers of the past using the cultural practices of the Musahars, or rat-eaters, of Uttar Pradesh. It was claimed by the author that some of the small animals carried in rock paintings include rats for eating. It is, of course, a fact that a great deal can be learnt from such studies, especially relating to demography, resource use, cultural practices, decision-making as well as housing structures and material culture. Their settlement patterns have also been used as a method to study the settlement patterns of archaeological sites in the Uttar Pradesh region, in order to understand them better.

Ansari[18] studied the Kols, Musahars and Tharus of U.P. to get a better idea of the way clay storage bins are used in the Neolithic period. Mahisdal (1380±105 BC and 1085±110 BC for Period I Chalcolithic) and Pandu Rajar Dhibi (1012±120 BC for Period II Chalcolithic), among others, were analyzed in this category. From Mahisdal in the 2nd millennium BC layer Rice (Oryza sativa L.) were found while the same was found in the first half of the 2ndmillennium BC layer at Pandu Rajar Dhibi.

Mohanta, et al.[19] have discovered 17 iron-smelting sites of prehistoric origin in the Mayurbhanj district. They argue against a diffusion of iron-smelting technology into the area and claim that it was produced indigenously. Iron is dated here to about the second half of the first millennium B.C. but it could have been earlier. Whether it was the prime mover in the clearing of forests and initiating agriculture is still not clear.

Further, Ray[13] also comments that the megalithic structure creation is a cultural habit of the present day Bhumij tribe, who erect such big stones over the charred bones of their ancestors. Such practices may have continued from the Neolithic.

Ray and Chakraborty[20] studied the Santals in the West Bengal region and saw the major use of pottery was by these tribals, yet they did not know how to make pottery. This function was performed by Hindu potters. As a result, such Hindu potters aided in a way the Santal habit of mixing hunting-gathering with an agricultural way of life.

The Rock Art Of The Region

In 1915 Percy Brown with C.J. Balding and C.W. Anderson found the rock paintings at Singanpur[21]. These were made with red ochre and the iron oxide was found in the rocks of the cave. Suspecting that the present floor was not the original one, it was excavated to a depth of 18 inches to 2.5 feet, yielding some pieces of rock crystal, coloured quartz, a small lump of red ochre and agate flakes. The weapons depicted include clubs, bows and axes. According to N.K. Chowdhury, these were drawn on felspathic sandstones, probably of the Dharwar period. The removal of felspars due to weathering has led to the friability.

The rock paintings found from Hazaribagh in Bihar became popular due to the efforts of Bulu Imam, who had contacted INTACH in order to publicise and protect these paintings through printed book/s[22] and web sites. The sites are found at Isko, Thathangi, Raham and Satpahar (1-9) in Hazaribagh district; Ranigadar, Naadiha, Fioluhar (Kauwakola), Sarkanda (Kakolata Fall Area) in district Nawada; Baltharva, Sankarpur in district Gaya and Mukwa, Pateshar, Jhapla, Hathidah, Dugha in district Kaimur.

They are often made of white or black paints. Neumayer[23] tries to give these paintings the context that is present in the Vindhyan rock paintings, comparing styles and patterns to show similarities and differences. He reaches the conclusion that one could not achieve any decision relating to dates from this site though it is possible that were linked to the Mesolithic settlements in the Vindhyan region. Further, the Oraons and other tribes in the region use similar styles of paintings even today in their depiction of various scenes on their bridal huts which they had been calling Khowar . Hence, due to this nomenclature, the tribal Khowar art has been transformed from the ancient past to the present day has been the claim of Bulu Imam and others. The proof of such a claim is still awaited though some tools have been picked up from the floor of the cave (Singh; 1996-97: personal communication). The linkage of the tools on the floor with the period of the paintings is still not clear.

Prasad[24] calls it the Vratya tradition. Here, again, it is claimed that skins may have been used for painting where caves were not available, and after the Palaeolithic it may have been a lost art which was again ‘reawakened’ many years later. It is claimed here that flint burins of various types and sizes were employed. The pigments used were red haematite or other oxides of iron and lime. Most of this was available in the nearby area. The painting was done by fingers or with a spatula, a crude brush like a frayed end of a twig or a pad of fur. A liquid binder must have been used for the paint whose identity has yet to be established. Prasad claims that a pastoral economy has mainly male deities. The paintings depict an organized catching of animals for domestication. A man carries a baby animal over his shoulder while a tall ‘superman’ stands with a prominent phallus observing. A dancing woman has been drawn using the form of a petroglyph using sharp stones. Other animals, including a dinosaur-type of animal are also seen. In Kaimur community dancing is seen as among the present-day tribals of the region. Other symbols seem to be magical or religious.

The rock engravings in the rock-shelters of Orissa (part of which are within the Chotanagpur plateau region) have been referred to by Neumayer with respect to the context of the Mesolithic in the region. They include Vikramkhol and Ulap in Sambalpur district (the former reported by K.P. Jayaswal[25] in 1933), Gudahandi and Yogimath (Nuwapara district), Manikmoda and Ushakothi (Sundargarh district) and Pakhna Pathar (Mayurbhanj district). Since then twenty-one more rock art sites have been added. Most of these are in district Sundargarh. It forms the connecting link between the Central Indian Chhattisgarh region and the Eastern Indian Chotanagpur region. The rock-art of this region resembles the rock-art sites in Central India[26].

The rock system is sedimentary, fossiliferous, purple ferruginous sandstone, silt-stone, shells and grits. The rocks found here are soft, medium-grained sandstone and red shale of the Cuddapah group and thus weathers easily. There are extensive plateaus and dense vegetation with several seasonal and perennial nallahs and streams. At the peaks or edges of such regions the rocks have been hollowed out naturally giving rise to rock shelters. Artifacts, including microliths, are also found lying beside or are embedded in and around these shelters. At Vikramkhol, Jayaswal in 1933 had claimed that the inscriptions resembled a pictographic script from right to left intermediary between the script of Brahmi and that of Mohenjodaro. The paintings include the use of red and yellow ochre. He claimed, thus, that Brahmi was Indian and the Phoenician and European scripts were developments from it. This was supported by N.P. Chakrabarti in 1936, Charles Fabri[27] in 1936 and G.C. Mohapatra[28] in 1982. However, Gordon[29] in 1960 disagreed with this view, claiming that there was no script to be seen among these inscriptions. This was also agreed as not being a script by Pradhan[26].

The microliths found include blades, backed points, lunates, trapeze, triangles, tined arrow-heads, burins, fluted cores, flakes and chips, lumps of ground haematites, hand-made mat-impressed pottery and wheel made pottery (Lekhamoda VI), ringstones, hammer-stones and celts extending from the Mesolithic period to the Neolithic-chalcolithic period. In all the cases engravings have been found with the paintings. The engravings were filled with dark red ochre or rubbed with moist haematite lumps. In their stylistic nature and their symbolism, they differ from the Central Indian rock paintings (though faint resemblances exist) and may have had a ritual purpose as among the wall paintings of the Saora and Santal, engravings among the Juangs, Kondhs or Gonds of tribal Orissa. Thus, an ethno-archaeological method of analysis might be more suitable in this context[26].

Erwin Neumayer[30] also reported more sites from Sambalpur and Sundargarh districts of Orissa – Osakothi or Ushakothi, Phuldungri, Brahmanigupha, Chhenga Pahar, Bridge Rock, Lakhamara, Sargikhol, Chhichiriakhol, Ulapgarh and Titliabahal. Again, he could not discern any similarities between these images and those in Central India.

The Problem Of The ‘Asura’ Sites

Over a hundred sites were described by S.C. Roy over the years (see an outline in Roy[31]). They were described as Asur sites due to local mythology, Asur garhs or forts and Asur sasans or burial grounds. In fact, the great slabs of stones on some of these Asur graves had been removed by the Mundas for the graves of their ancestors. Roy saw them as having the following basic features (after Chakrabarti[32]):

They were always on elevated areas conveniently located on the banks of a water course and eminently suited for defence.

They had foundations of brick buildings, large tanks, cinerary urns, copper ornaments and stone beads, copper celts and traces of iron-smelting. The antiquity of the stone temple ruins and stone sculptures found associated with some reputed Asura sites was unlikely to be applicable to them.

The period covers a wide chronological horizon, though Roy’s assertion that they cover the Stone, Copper and early Iron Age are wrong. They are mostly within the early historic period.

Further, S.C. Roy divided two kinds of urns found in the graves as belonging to Group A or Group B. Group A in Khuntitoli included large earthenware urns not found by him earlier in Ranchi and Singhbhum excavations. Group A and Group B in this village were separated by a water channel. Group B urns were of the usual ghara shape that he normally found in such graves in the district. In both cases, the contents of the urns do not indicate any differences. He also indicates that since the area had seen prolonged use, perhaps one group (group A) was more advanced and had a more improved pattern of urn than group B which might have been an earlier form. The slabs were supported like a seat with four stones on four corners ‘like a house’ and the size of the slab was no indication of the amount of grave goods included. Each slab was placed East-West on its long axis.

The grave goods included bronze and copper chains, bracelets, anklets, finger rings, toe rings, beads, bronze ankle bells, ear ornaments, dishes, bells, unstamped copper coins, iron arrowheads, rings, jugs (some spouted) with patterns on them and bones, which had been kept here after burning. Below the level of the graveyard some Neolithic stone celts were also found. Here, after the rains, Roy picked up stone crystal beads, arrowheads, axe-heads, stone cores and flakes from 7/8-15 feet below the brick foundations of Asur buildings. Shiva-lingas with the encircling yonis were also present. Roy believed the Asurs to be the worshippers of these. At Khuntitoli, a tiny metal figure of a man driving a plough drawn by two bullocks was ploughed up near an Asur site.

Further small stools were found in regions like Palamau district, and such stools are still worshipped and kept under trees, people believing them to have been there for many centuries. Further, Roy also comments on the fact that even if Asurs invented the smelting of iron, there were too few iron artifacts. Thus, he sees a four or three stage culture represented by the Asur graves – first a Neolithic stage, over that a Copper Age and overlapping that an Iron Age. Under this there may be some palaeolithic tools. Above this there may be Kushan coins. The Asurs of yore seem to have great forts, were skilled potters and workers in copper, bronze and iron. The currency involved coins of shells and small, round, thick pieces of copper.

A strong belief in the after-life was also inferred from the grave goods. The bodies were burnt, then broken with a heavy stick and put into the cinerary urns. Some of the bones show injury marks, one on a skull, if it be ante-mortem which is likely, resulted in the death of the individual. The stature was between 4 feet 10 inches to 5 feet with good musculature. Such an injury that resulted in death was inferred from a skull in Khuntitoli, Singhbhum district[33]. The skull capacity was smaller and there were prominent cheek bones, with small jaws, face and slight prognathism[34]. Caldwell[35] also analyzed the proportion of various metals in the artifacts found.

Murray’s report in 1940 indicates his studies of Ruamgarh in 1926 of such a site from Singhbhum district. There are problems of lumping all the cultural materials into one horizon and then labeling it as being from 3rd-4thcenturies AD. The two crania found were not part of the site itself but were found some way beside it due to the exposure of their burial and two stones resting near them indicate a burial area. One was a male of between 22-26 years, the other, also a male, between 17-21 years. They could possibly be linked to Mundas in the region[33].

The skulls and skeletal material found from Bulandibagh and Kumrahar near Patna are dated to about 2115 ± 250 BP (Kumrahar). The Kumrahar adult female skull was more recent and different to the Bulandibagh young adult male[36].

Though the issue may be argued, there is no true megalithic formation present. The so-called ‘megalithic’ sites found in the district could be interpreted in a different way. The majority of the tribals of the region, especially the Mundas and the Oraons, worship not only the forests, land, river, and mountains but also the stones around them. Spirits are given a place in the hearth by digging in a wooden block or a piece of stone. There is ancestor worship and many of the spirits are those of ancestors. Hence, the usage of large stone pieces to mark graves or to extend the usage to give a khunt or permanent place for a spirit cannot be extrapolated into an entire, regulated practice and cultural features that is a hallmark of megalithic cultures in South India.

Secondly, there are problems with the dating of this practice since large stones or pulkhi are still placed on top of the place where the remains of the dead are interred to this date in many tribal villages, especially among the Mundas.

Thus, the ‘Asura’ sites are characterized by remains of brick buildings, traces of iron-smelting, copper implements and ornaments, gold coins, stone implements, beads, silted up tanks, cinerary urns, iron implements, potsherds, stone implements and sculptures. The pottery is of coarse fabric, thick in section, terracotta red in colour and mostly wheelmade. It includes jars, bowls and vases[32]. The radio carbon dates suggested that these finds belonged to the late centuries B.C. and the early centuries A.D. Copper objects found sometimes overlap with these Asura sites[37].

Two uncalibrated radiocarbon dates for some of these sites are TF-369 – 1970+90 BP (20 BC) and TF-70 – 1850+100 BP (100 AD)[32].

Was there an Asura kingdom at the time? We cannot know this for certain. There are indications that some of these sites were located on elevated areas which were highly defensible. It is entirely possible that what is taken to be Asura finds may be the finds of two or more cultures living in close association or trading, with one of them participating in early chiefdoms or states. That the ‘Asura’ community was practicing trade with others is evident from the gold coins found in some of the sites.

In Darbhanga district, Bihar, there is a fort called Asurgarh, about 40 miles from Darbhanga and Madhubani. Supposedly, it had been settled by Asur Shah, a Muslim chieftain, some of whose punch marked coins were also found. Locals claim the area to be old, if not Buddhistic in period, but a Muslim chieftain would put it not older than 15th century. The name given to the chieftain is also not complimentary[38].

What we know of present Asuras is very little. The 1981 Census shows them to be less than 8,000 in number. They remember that their sole earning used to be from smelting iron ore with the help of charcoal. Few families maintain this practice now, and NGOs like Vikas Bharati in Bishunpur are trying to train them and others to teach and re-learn these dying skills[3940].

Banerji-Sastri[41] tried to trace them through historical sources and found the earliest reference to be around 2nd century BC. Earlier to this, they may have belonged to the land of the Assyrians. It is claimed that the Ashur absorbed the cultures of ancient Egypt and Babylon and passed them on to India. They are known in history as Ashur about the 1200s (BC) after which they disappear to re-emerge in the 10th century BC. The author claims they came to India through sea routes rather than land ones.

They then became incorporated into Indian society, traveling into many of its parts. They became the Brahmans who sat beside the various kings in India and were well-versed in astronomy and medicine. They also collaborated and fought with a variety of different groups. They may have become the kings of Magadh (now the Patna and Gaya districts of Bihar) and have left traces in Rajgir and various other Central Indian sites along with the mythology of the sacrifice conducted by Raja Janmejaya due to which all the snakes of the Chotanagpur region died, a mythology still enacted by many tribals of the region[42].

Further, they were seafarers and traveled all over India often through waterways. They became gradually absorbed into Indian society of that time, though some returned back to Assyria and others went on to the Pacific. Small groups of them often lost at wars and hid in the jungles of Chotanagpur, Nagpur, the North East, going to the places which carried their names, for they brought to India their own serpent symbols of the Naga and that of Garuda[43].

Initially, it may be supposed that the defined Asuras of Sanskritic mythology of those who were “of unintelligible speech”, “devoid of rites”, “following strange ordinances”, “without devotion”, “not sacrificing”, “indifferent to the gods” and “lawless” were the tribals of the Chotanagpur and other regions. However, this may not be entirely true, since Munda mythology refers to the Asuras as being killed by their gods, the variety of Asura sites and their graveyards. Roy[44] claims that the present-day Asurs took up the name of this ancient group and its iron-smelting.

These Asurs are divided into three kinds: there are the Soika Asurs, also called Agarias or Agaria Asurs (the iron-smelters), the Birjias who have also taken up plaiting bamboo baskets, etc. with iron-smelting and the Jait Asurs who live in villages, smelt iron and manufacture ploughshares and other rude iron implements, some families also taking up agriculture and being Hinduised neither marry nor interdine with other sections. Incidentally, iron-smelting Agarias are also found in Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh states also[44].

The Birjias as well as the Soika Asurs have nomadic or migratory groups (uthlu ) as well as settled groups (thania ). The settled Birjias are further divided into the Dudh Birjias who do not eat beef and the Rarh Birjias who do. A further division among the Birjias are those who anoint their brides and bridegrooms only with oil (Telia Birjias) and those who use vermilion as well as oil (Sinduraha Birjias). The Asurs seem to have similar practices with the Mundas and the Birjias seem to have clan as well as individual totems. They now practise only cremation of the dead and there is no urn-burial. However, such burial is seen among the Hos and Mundas. In a particular ritual called sanrsi-kulasi , iron implements are used to sacrifice fowl to ancient Asur spirits in order that they continue giving them a plentiful supply of iron-ore. Though the two tribes look similar, the title Asur seems to have been given to them because they practice iron-smelting. The earlier Asurs were not from the same racial stock as the Mundas[44].

Roy[44] further avers that they were an earlier advanced group of people who lost to the Indo-Aryans and escaped to the jungles. They were rapidly absorbed into the Indian groups through intermarriage and the Bengalis contain a large proportion of this mixture also. They are also found in Southern and Central India. He refers to them as the Nag branch of the Asurs and finds similarities with Asur sites and the ruins of the Indus Valley civilization. He also feels that this group may have had more than one division and may have been as widespread as the Indus Valley sites.

In the mythology of the Mundas, there is an account of the existence of the Asuras, who were iron-smelters, long before the advent of Mundas. The Asuras would not allow the Mundas to stay. Hence, the Munda gods tried to intercede on behalf of the Mundas. When the Asuras still refused to allow Mundas into their territory, the Asuras were punished by the gods. The men went into their iron-smelting furnaces believing that they would find gold. Doors were shut on them and they burnt to death. The women became part of the Munda tribe.

The dates match this version of mytho-history, for the first Munda King, Phanimukut Rai, was crowned in 93 A.D. according to the Vansavali or genealogy kept by his 63rd descendant, the present Maharaja of Chotanagpur.

The coming of the Oraons into the region is also clouded in mystery. Some accounts claim that the Oraons were present at the coronation of Phanimukut Rai. Others claim that they lost their kingdom when the Turkish Muslims attacked and won Rohtasgarh in 1198 A.D. Still others vehemently declare that they were beaten by Sher Shah Suri who treacherously defeated them and won Rohtasgarh from them in 1538 A.D., leaving them to flee to Chotanagpur[45].

It is also a matter of confusion that Oraons are a Dravidian language speaking group[46] while the Asuras and the Mundas are an Austro-Asiatic language speaking group[46].

Apart from the Oraons, the Sauriya Paharia, the Mal Pahariya and the Gond speak the Dravidian language. Hence, by this token it was believed that since all the other communities spoke either Indo-Aryan or Austro-Asiatic languages they must have migrated from the Southern parts of India. According to S.C. Roy, the route could not be ascertained but he suspected that a small portion of this group settled in the Rajmahal hills and came to be called the Maler tribe. S.C. Roy thus influenced his student to conduct a study on the Maler. The study of S.S. Sarkar on the Maler of Rajmahal Hills disproved this hypothesis.

However, it is clear that the Oraons came after the Mundas had already established themselves in the region. This can be seen from their mythological accounts. The Oraons of Ranchi district frequently claim that they had to give up their language as well as their gods when they settled on Munda land which may be seen even now. Then, many Oraons villages still have their old Munda names. Finally, the original, communal land-ownership of the Mundas (known as the khuntkatti ) gave way to the present bhuinhari land tenure of the Oraons which is a breakdown of the khuntkatti tenure. This land tenure also was broken down into a tenure system for the later settlers and who were required as service providers (whether castes or tribes) for the dominant caste or tribe of the village. This became the raiyati tenure.

Having delineated these problems, I again return to the issue of state formation or of the rise of chiefdoms. The case of the Asuras makes it clear that there was trade with others outside this area. Whether such Asuras can be linked to the Asuras of the Mahabharata period is a matter of conjecture[40]. However, if the black or gray clayey layer is taken to be the site of a neolithic-chalcolithic industry, then other evidences would have to be taken into account.

Iron is known from many regions in the area. At Barudih in Singhbhum district, an iron sickle with a profusion of Neolithic celts and coarse black-and-red pottery has been dated to 1055/210 BC (calibrated to 140-830 BC). Further, in the Neolithic-Chalcolithic phase, a total of 80 sites are recorded from Bengal alone. Of these, the iron-bearing layers of Bahiri, Pandu Rajar Dhibi and Mangalkot yield dates around 1000 BC for their first iron-bearing levels[47].

It is necessary for a large population to go in for an intensification of their agriculture as arable land decreases. However, early states need not have intensification of agriculture as a necessary hallmark[48]. They may have a root crop agriculture tradition which would require the small-sized celts and ring-stones found in the region[4950].

It is not yet clear when or how sedentary agricultural practices came into the region. The Oraons claim that they first started practicing agriculture but there is no evidence to prove this. What is clear is that the early inhabitants of Ranchi district did not solely practice sedentary agriculture. All of them had alternative modes of livelihood.

Conclusions

Considering the fact that the Hathnora calvarium was dated to about 760,000 BP, it seems important to find out the spread and dispersion of prehistoric cultures in India during the entire period. The Chotanagpur region may be taken to be one geographic zone and thus it has been taken as a unit, even though it spans many states. One of the states that it spans is Madhya Pradesh, which includes the Hathnora region.

This tenuous link has been taken to include the fact that populations from these regions must have passed through the region or even settled there. The diversity and specificity of the tools found in the region need to be explained, if not through direct stratigraphic and other hard evidences, then through the lens of a variety of theoretical approaches.

The data from ethno-archaeology teaches us that there is a very tenuous link between the current classification of communities as ‘tribes’ or as ‘peasants’ since there is a deep interlinkage between these two hypothetically created definitions. Also, many communities also traditionally participated in metal-working and so their ‘simple’ or ‘primitive’ nature is thrown into doubt. Different communities seem to have formed niches or economic-categories in between modern communities. This model that is seen in the current context may also have been followed earlier. As a result, it seems clear that earlier communities need not have followed one culture but would have been composites of populations having many cultures, often interspersed and sharing traits and ideas.

Thus, the iron using and iron making cultures of the past could not have been a unified Iron Age but was a product of this past multi-cultural heritage where many cultures collected, smelted and worked iron to help out and earn from the iron using communities that emerged.

The rock art-creating cultures are another offshoot of this complexity that is emerging in this zone. There seems to be a large variety in these as well and spatially this is to be expected since they are located in regions fairly separated. However, the rock art that is seen here seems to have lent itself readily to being transmitted culturally to present generations of tribals in the Jharkhand region who use such motifs as decorations on the mud walls of their huts even today. Also, there seems to be a traditional sequence from one stage to the next and associated skeletal finds that substantiate this.

The Asura sites are much more varied and interesting than they had appeared at first. It seems that most states, grave goods and use of iron and other metals has often made early archaeologists call them Asura sites, which has been linked with some mythological material or researches into local folklore. However, the Asura sites seem to be developing into the same pattern of variety within the structure that we see in the ethno-archaeological, iron using and iron making and rock art contexts. Thus, they are also formed from a variety of cultures and communities and their apparent similarity should not blind us to this basic reality. In the next stage of analysis we shall see how the entire structure of the prehistory of the Chotanagpur region may be seen from this perspective.