Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/p7ote68

Paramahamsa. Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam through Indus Script cipher

भारतम् जनम् कथनम् -- म्लेच्छित विकल्प (Meluhha cipher), Proto-Prakritam

Introduction

A hamsa in a cartouche is a remarkable hieroglyph on an Indus Script seal. karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) If this denotes a black swan, the unrealized delineation of the Maritime Tin Route linking Hanoi and Haifa has to be narrated as part of Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam celebrating their excellence in metalwork using tin bronzes and cire perdue metal castings of exquisite beauty and their meaningful messages in Proto-Prakritam, reinforcing the Mlecchita Vikalpa as a cipher writing recognized in ancient texts. Using this cipher, Indus Script decipherment provides the framework for the narration of a history devoid of assumed doctrines, for e.g Aryan invasion/migration into India as a linguistic doctrine. This doctrine gets negated by the lexis of Proto-Prakritam metal, alloy, mineral, and casting work with furnaces, smelters yielded by the decipherment.

A powerpoint presentation in 192 slides is a brief narration of the 5,300 year old history of Bharata people, mostly on the banks of Rivers Sarasvati and Sindhu with contacts in civilization areas of the Far East and in Eurasia (Fertile Crescent).

karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

![What is a Black Swan?]()

http://www.slideshare.net/JohnSykes/myanmar-the-black-swan-of-global-tin-gardiner-sykes-may-2015-itri-conference Myanmar The Black Swan of Global Tin - Gardiner & Sykes - May 2015 - ITRI Conference

This is paramahamsa a black swan which could create a hard alloy. Copper alloyed with tin (cassiterite) created Tin Bronze which substituted for the scarce naturally occurrin Arsenical Copper which was used cire perdue (lost wax casting) to create the exquisite alloy artifacts of Nahal Mishmar of 4th millennium BCE. The discovery of tin as an alloying mineral was a revolution of the Bronze Age in which Bhāratam Janam participated as artisans and seafaring merchants along the Maritime Tin Route from Hanoi to Haifa.

The narrative of the history of Bhāratam Janam as they transited from the neolithic to the Tin-Bronze Age is a history of artisans and metalworkers inventing new alloys and metal casting methods using cire perdue (lost-wax) techniques, resulting in exquisite bronze artifacts.

![]() Lost-wax casting. Bronze statue, Mohenjo-daro. Bronze statue of a woman holding a small bowl, Mohenjo-daro; copper alloy made using cire perdue method (DK 12728; Mackay 1938: 274, Pl. LXXIII, 9-11)

Lost-wax casting. Bronze statue, Mohenjo-daro. Bronze statue of a woman holding a small bowl, Mohenjo-daro; copper alloy made using cire perdue method (DK 12728; Mackay 1938: 274, Pl. LXXIII, 9-11)

![]()

![]()

![]()

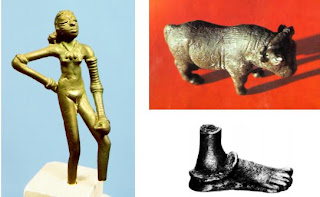

Dancing girl of Sarasvati civilization. 4.3 in. h. Mohenjo-Daro. “Metallurgists smelted silver, lead, and copper and worked gold too. Coppersmiths employed tin bronze as in Sumer, but also an alloy of copper with from 3.4 to 4.4 per cent of arsenic, an alloy used also at Anau in Transcaspia. They could cast cire perdue (lost wax) and rivet, but never seem to have resorted to brazing or soldering.” (Childe, Gordon, 1952, New light on the most ancien East, New York, Frederick A. Praeger)

Dance-step as hieroglyph on a potsherd, Bhirrana. Hieroglyph: meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’(Munda); मेढ meḍh‘merchant’s helper’(Pkt.) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda)

Yuval Gorden notes:"While the traditional manifestation of the technology has vanished from many parts of the world, it has survived in some areas of India. The tradition is carried on in the manufacture of small pieces by tribal groups or by Hindu metalworkers. These tribal people live in the districts of Bankura, Burdwan, and Midnapore in West Bengal...The Dhokra apply two or more layers of clay on top of the wax model. First, a thin clay paste is added and allowed to dry; then a layer of rougher clay mixed with rice husks is added and also allowed to dry. A hole is sometimes cut through the top of the clay coverings to allow for the entrance of the molten metal. Likewise, a channel is made in the bottom to let the wax flow out of the mold. Metal wires are then tied around the whole construction to keep it intact. The mold is heated

until the wax is melted and poured out...Once the mold mixture has set hard, the molds are placed in a furnace and heated until the wax is melted and integrated into the rather spongy fabric of the mold. Then the heating continues until the metal is melted, made evident by a green tinge of the fire, at which point the molds are turned upside down and filled with the liquid metal from the flask. This point is extremely important for our discussion, because it indicates that crucibles are not necessarily used in the process of lost wax casting, in contrast to open casting, where their use is mandatory."

Ibex and birds on Nahal Mishmar artefacts

After examining several artefacts of Nahal Mishmar hoard, Goren concludes: "The results of this study indicate that all the examined materials were the remains of the casting molds...This indeed indiates that the Chalcolithic technology of mold construction for the lost wax casting technique was well established and performed by specialists. Moreover, the emphasized homogeneity of the materials and technology in use, regardless of the location of the find, stands against the possibility of production by itinerary craftsmen and supports the idea that all of these items were produced by a single workshop or workshop cluster. The results make it clear that, although Chalcolithic mold production and casting techniques can be compared to some extent with the methods of traditional craftsmen such as the Dhokra of India, they are far more sophisticated and thus more analogous with the mold construction techniques used today by modern workshops...some motifs...specifically depict ibexes and vultures...It is likely that these animals were seen as protectors of this highly skilled metallurgy... (ibex) representation in the En Gedi sanctuary might be related to the special role of this animal in the decoration fo the Chalcolithic metal artifacts as well as ossuaries. (p.393)"

[Yuval Goren, 2008, The location of specialized copper production by the lost wax technique in the chalcolithis southern Levant, Geoarchaeology: An international Journal, Vol. 23, No. 3, 374-397 (2008), p. 377].

http://www.scribd.com/doc/220039411/Yuval-Goren-2008-The-location-of-specialized-copper-production-by-the-lost-wax-technique-in-the-chalcolithis-southern-Levant-Geoarchaeology-An-int

I suggest that an alternative interpretation for the use of ibex and birds on Nahal Mishmar artefacts. They may be Meluhha hieroglyphs describing the specific metallurgical skill of and materials used by the artisans.

![In 1961, a group of archaeologists were looking for Dead Sea scrolls. Instead, they found the striking double ibex and the rest of the hoard now known as the "Cave of Treasure." (Courtesy of the Israel Museum)]()

![]()

The double ibex was made using a complicated wax and ceramic mold..Standard (scepter)

with ibex heads.

Dm. mraṅ m. ‘markhor’ Wkh. merg f. ‘ibex’ (CDIAL 9885) Tor. miṇḍ ‘ram’, miṇḍā́l ‘markhor’

(CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Munda.Ho.) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. āra‘six’ Rebus: āra ‘brass’

![]()

![]()

![]() The Leopards weight from Shahi Tump - Photography and 30 MeV accelerator tomodensimetry showing the copper shell and the lead filling.(Science for Cultural Heritage: Technological Innovation and Case Studies in Marine and Land Archaeology in the Adriatic Region and Inland : VII International Conference on Science, Arts and Culture : August 28-31, 2007, Veli Lošinj, Croatia, World Scientific, 2010. The aim of the conference was to discuss the contribution of physics and other sciences in archaeological research and in the preservation of cultural heritage.)

The Leopards weight from Shahi Tump - Photography and 30 MeV accelerator tomodensimetry showing the copper shell and the lead filling.(Science for Cultural Heritage: Technological Innovation and Case Studies in Marine and Land Archaeology in the Adriatic Region and Inland : VII International Conference on Science, Arts and Culture : August 28-31, 2007, Veli Lošinj, Croatia, World Scientific, 2010. The aim of the conference was to discuss the contribution of physics and other sciences in archaeological research and in the preservation of cultural heritage.) ![]()

![]() Mohenjo-daro seal depicts a hieroglyph composition, comparable to the horned, decrepit woman with hanging breasts and ligatured to a bovine hindlegs and tail as shown on one side of the Dholavira tablet. There is an added narrative of two hieroglyphs: horned tiger and a leafless tree.

Mohenjo-daro seal depicts a hieroglyph composition, comparable to the horned, decrepit woman with hanging breasts and ligatured to a bovine hindlegs and tail as shown on one side of the Dholavira tablet. There is an added narrative of two hieroglyphs: horned tiger and a leafless tree.

I would like to comment on the following Fig. 16 of Parpola's paper (Beginnings of Indian astronomy (Asko Parpola, 2013) With reference to a parallel development in China. in: History of Science in South Asia 1 (2013), pp. 21-78):![]()

Meluhha hieroglyphs: 1. Dhokra kamar lost-wax metal caster; 2. Dance-step of Mohenjo-daro metal cast

भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c.भरताचें भांडें (p. 603) [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metal भरत. 2 See भरिताचें भांडें.भरती (p. 603) [ bharatī ] a Composed of the metal भरत. (Molesworth Marathi Dictionary).This gloss, bharata is denoted by the hieroglyphs: backbone, ox.

![]() Seal published by Omananda Saraswati. In Pl. 275: Omananda Saraswati 1975. Ancient Seals of Haryana (in Hindi). Rohtak.

Seal published by Omananda Saraswati. In Pl. 275: Omananda Saraswati 1975. Ancient Seals of Haryana (in Hindi). Rohtak.

![]() This pictorial motif gets normalized in Indus writing system as a hieroglyph sign: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) Tir. mar -- kaṇḍḗ ʻ back (of the body) ʼ; S. kaṇḍo m. ʻ back ʼ, L. kaṇḍ f., kaṇḍā m. ʻ backbone ʼ, awāṇ. kaṇḍ, °ḍī ʻ back ʼH. kã̄ṭā m. ʻ spine ʼ, G. kã̄ṭɔ m., M. kã̄ṭā m.; Pk. kaṁḍa -- m. ʻ backbone ʼ.(CDIAL 2670) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) The hieroglyph ligature to convey the semantics of ‘bone’ and rebus reading is: ‘four short numeral strokes ligature’ |||| Numeral 4: gaṇḍa 'four' Rebus: kaṇḍa 'furnace, fire-altar' (Santali)

This pictorial motif gets normalized in Indus writing system as a hieroglyph sign: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) Tir. mar -- kaṇḍḗ ʻ back (of the body) ʼ; S. kaṇḍo m. ʻ back ʼ, L. kaṇḍ f., kaṇḍā m. ʻ backbone ʼ, awāṇ. kaṇḍ, °ḍī ʻ back ʼH. kã̄ṭā m. ʻ spine ʼ, G. kã̄ṭɔ m., M. kã̄ṭā m.; Pk. kaṁḍa -- m. ʻ backbone ʼ.(CDIAL 2670) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) The hieroglyph ligature to convey the semantics of ‘bone’ and rebus reading is: ‘four short numeral strokes ligature’ |||| Numeral 4: gaṇḍa 'four' Rebus: kaṇḍa 'furnace, fire-altar' (Santali)

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

September 3, 2015

https://www.scribd.com/doc/277981068/Itih%C4%81sa-of-Bh%C4%81ratam-Janam-Through-Indus-Script-and-Maritime-Tin-Route

Paramahamsa. Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam through Indus Script cipher

भारतम् जनम् कथनम् -- म्लेच्छित विकल्प (Meluhha cipher), Proto-Prakritam

Introduction

A hamsa in a cartouche is a remarkable hieroglyph on an Indus Script seal. karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) If this denotes a black swan, the unrealized delineation of the Maritime Tin Route linking Hanoi and Haifa has to be narrated as part of Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam celebrating their excellence in metalwork using tin bronzes and cire perdue metal castings of exquisite beauty and their meaningful messages in Proto-Prakritam, reinforcing the Mlecchita Vikalpa as a cipher writing recognized in ancient texts. Using this cipher, Indus Script decipherment provides the framework for the narration of a history devoid of assumed doctrines, for e.g Aryan invasion/migration into India as a linguistic doctrine. This doctrine gets negated by the lexis of Proto-Prakritam metal, alloy, mineral, and casting work with furnaces, smelters yielded by the decipherment.

A powerpoint presentation in 192 slides is a brief narration of the 5,300 year old history of Bharata people, mostly on the banks of Rivers Sarasvati and Sindhu with contacts in civilization areas of the Far East and in Eurasia (Fertile Crescent).

karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

http://www.slideshare.net/JohnSykes/myanmar-the-black-swan-of-global-tin-gardiner-sykes-may-2015-itri-conference Myanmar The Black Swan of Global Tin - Gardiner & Sykes - May 2015 - ITRI Conference

This is paramahamsa a black swan which could create a hard alloy. Copper alloyed with tin (cassiterite) created Tin Bronze which substituted for the scarce naturally occurrin Arsenical Copper which was used cire perdue (lost wax casting) to create the exquisite alloy artifacts of Nahal Mishmar of 4th millennium BCE. The discovery of tin as an alloying mineral was a revolution of the Bronze Age in which Bhāratam Janam participated as artisans and seafaring merchants along the Maritime Tin Route from Hanoi to Haifa.

The narrative of the history of Bhāratam Janam as they transited from the neolithic to the Tin-Bronze Age is a history of artisans and metalworkers inventing new alloys and metal casting methods using cire perdue (lost-wax) techniques, resulting in exquisite bronze artifacts.

Lost-wax casting. Bronze statue, Mohenjo-daro. Bronze statue of a woman holding a small bowl, Mohenjo-daro; copper alloy made using cire perdue method (DK 12728; Mackay 1938: 274, Pl. LXXIII, 9-11)

Lost-wax casting. Bronze statue, Mohenjo-daro. Bronze statue of a woman holding a small bowl, Mohenjo-daro; copper alloy made using cire perdue method (DK 12728; Mackay 1938: 274, Pl. LXXIII, 9-11) Muhly speculates on the possible reason for using of hard alloy for lost-wax castings: "...perhaps arsenical copper was used at Nahal Mishmar not because it was harder, more durable metal but because it would have facilitated the production of intricate lost-wax castings." (Muhly, J., 1986, The beginnings of metallurgy in the old world. In Maddin R, ed., The beginning of the use of metals and alloys, pp. 2-20. Zhengzhou: Second International conference on the beginning of the use of metals and alloys.)

Dancing girl of Sarasvati civilization. 4.3 in. h. Mohenjo-Daro. “Metallurgists smelted silver, lead, and copper and worked gold too. Coppersmiths employed tin bronze as in Sumer, but also an alloy of copper with from 3.4 to 4.4 per cent of arsenic, an alloy used also at Anau in Transcaspia. They could cast cire perdue (lost wax) and rivet, but never seem to have resorted to brazing or soldering.” (Childe, Gordon, 1952, New light on the most ancien East, New York, Frederick A. Praeger)

"Archaeological excavations have shown that Harappan metal smiths obtained copper ore (either directly or through local communities) from the Aravalli hills, Baluchistan or beyond. They soon discovered that adding tin to copper produced bronze, a metal harder than copper yet easier to cast, and also more resistant to corrosion."

Dance-step as hieroglyph on a potsherd, Bhirrana. Hieroglyph: meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’(Munda); मेढ meḍh‘merchant’s helper’(Pkt.) meḍ iron (Ho.) meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda)

Yuval Gorden notes:"While the traditional manifestation of the technology has vanished from many parts of the world, it has survived in some areas of India. The tradition is carried on in the manufacture of small pieces by tribal groups or by Hindu metalworkers. These tribal people live in the districts of Bankura, Burdwan, and Midnapore in West Bengal...The Dhokra apply two or more layers of clay on top of the wax model. First, a thin clay paste is added and allowed to dry; then a layer of rougher clay mixed with rice husks is added and also allowed to dry. A hole is sometimes cut through the top of the clay coverings to allow for the entrance of the molten metal. Likewise, a channel is made in the bottom to let the wax flow out of the mold. Metal wires are then tied around the whole construction to keep it intact. The mold is heated

until the wax is melted and poured out...Once the mold mixture has set hard, the molds are placed in a furnace and heated until the wax is melted and integrated into the rather spongy fabric of the mold. Then the heating continues until the metal is melted, made evident by a green tinge of the fire, at which point the molds are turned upside down and filled with the liquid metal from the flask. This point is extremely important for our discussion, because it indicates that crucibles are not necessarily used in the process of lost wax casting, in contrast to open casting, where their use is mandatory."

Ibex and birds on Nahal Mishmar artefacts

After examining several artefacts of Nahal Mishmar hoard, Goren concludes: "The results of this study indicate that all the examined materials were the remains of the casting molds...This indeed indiates that the Chalcolithic technology of mold construction for the lost wax casting technique was well established and performed by specialists. Moreover, the emphasized homogeneity of the materials and technology in use, regardless of the location of the find, stands against the possibility of production by itinerary craftsmen and supports the idea that all of these items were produced by a single workshop or workshop cluster. The results make it clear that, although Chalcolithic mold production and casting techniques can be compared to some extent with the methods of traditional craftsmen such as the Dhokra of India, they are far more sophisticated and thus more analogous with the mold construction techniques used today by modern workshops...some motifs...specifically depict ibexes and vultures...It is likely that these animals were seen as protectors of this highly skilled metallurgy... (ibex) representation in the En Gedi sanctuary might be related to the special role of this animal in the decoration fo the Chalcolithic metal artifacts as well as ossuaries. (p.393)"

[Yuval Goren, 2008, The location of specialized copper production by the lost wax technique in the chalcolithis southern Levant, Geoarchaeology: An international Journal, Vol. 23, No. 3, 374-397 (2008), p. 377].

http://www.scribd.com/doc/220039411/Yuval-Goren-2008-The-location-of-specialized-copper-production-by-the-lost-wax-technique-in-the-chalcolithis-southern-Levant-Geoarchaeology-An-int

Radiocarbon dating of Nahal Mishmar reed mat by Arizona AMS laboratory takes at least some of (the finds to 5375 +_ 55 to 6020+_60 BP). (Aardsman, G., 2001, New radiocarbon dates for the reed mat from the cave of the treasure, Israel, Radiocarbon, Volume 43, number 3: 1247-1254). This indicates the possibility that cire perdue technique was already known to the metallurgists who created the Nahal Mishmar artefacts. There is, however, a possibility that all the artefacts of the Nahal Mishmar hoard may not belong to the same date and hence, cire perdue artefacts might have been acquisitions of a later date. (Shlomo Guil

I suggest that an alternative interpretation for the use of ibex and birds on Nahal Mishmar artefacts. They may be Meluhha hieroglyphs describing the specific metallurgical skill of and materials used by the artisans.

The double ibex was made using a complicated wax and ceramic mold..Standard (scepter)

with ibex heads.

Dm. mraṅ m. ‘markhor’ Wkh. merg f. ‘ibex’ (CDIAL 9885) Tor. miṇḍ ‘ram’, miṇḍā́l ‘markhor’

(CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Munda.Ho.) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. āra‘six’ Rebus: āra ‘brass’

Nahal Mishmar. Crown with building facade decoration and birds.

karaṇḍa ‘duck’ (Sanskrit) karaṛa ‘a very large aquatic bird’ (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'.

sã̄gāḍā m. ʻ frame of a building ʼ (M.)(CDIAL 12859) Rebus: jaṅgaḍ ‘entrustment articles’ sãgaṛh m. ʻ line of entrenchments, stone walls for defence ʼ (Lahnda).(CDIAL 12845) Allograph: saṅgaḍa ‘lathe’. 'potable furnace'. sang ‘stone’, gaḍa ‘large stone’. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'. koḍ ‘horns’ Rebus: koḍ‘artisan’s workshop’.

[quote] Among the items displayed in ISAW’s Masters of Fire exhibit are Nahal Mishmar finds—intricately crafted scepters and mace heads—that were made using the relatively advanced lost-wax castingtechnique, in which a mixture of copper, arsenic, antimony, and nickel is poured into a mold. One highlight is a circular metal object with decorative horns and vultures (birds) protruding from the top—but don’t let its shape fool you, notes curator Michael Sebanne of the Israeli Antiquities Authority. This “crown” was probably too heavy, and too small in circumference, to be worn; it’s more likely a model of a temple or a tomb, Sebanne says.

We know that people living in the Middle East more than 6,000 years ago raised livestock for dairy, crafted exquisite vessels out of copper, and took great care in burying their dead. But what did they believe? How did they view the world? Did they conceive of the beautiful objects they made as art?

These are the questions at the heart of Masters of Fire: Copper Age Art From Israel, a current NYU Institute for the Study of the Ancient World exhibit displaying 157 items from the Chalcolithic Era (4500-3600 BCE)—otherwise known as the Copper Age. Over the past eight decades of archaeological discovery, scholars have determined that this was the period in which the people of the Southern Levant first settled in organized villages headed by tribal chiefs; first imported raw metals from great distances to forge tools; and first dedicated sanctuaries for cults and rituals. For the first time, workers specialized in agriculture and particular crafts, and wool, cheese, olives, and dates were produced on a large scale.

But mysteries still remain. To look at these artifacts is to confront adistant, and yet recognizable, ancestor—foreign, and yet somehow familiar.

...

The Leopards weight from Shahi Tump - Photography and 30 MeV accelerator tomodensimetry showing the copper shell and the lead filling.(Science for Cultural Heritage: Technological Innovation and Case Studies in Marine and Land Archaeology in the Adriatic Region and Inland : VII International Conference on Science, Arts and Culture : August 28-31, 2007, Veli Lošinj, Croatia, World Scientific, 2010. The aim of the conference was to discuss the contribution of physics and other sciences in archaeological research and in the preservation of cultural heritage.)

The Leopards weight from Shahi Tump - Photography and 30 MeV accelerator tomodensimetry showing the copper shell and the lead filling.(Science for Cultural Heritage: Technological Innovation and Case Studies in Marine and Land Archaeology in the Adriatic Region and Inland : VII International Conference on Science, Arts and Culture : August 28-31, 2007, Veli Lošinj, Croatia, World Scientific, 2010. The aim of the conference was to discuss the contribution of physics and other sciences in archaeological research and in the preservation of cultural heritage.)

...

Meluhha metallurgy to Bronze Age civilizations

I would like to comment on the following Fig. 16 of Parpola's paper (Beginnings of Indian astronomy (Asko Parpola, 2013) With reference to a parallel development in China. in: History of Science in South Asia 1 (2013), pp. 21-78):

Fig. 16 Two-faced tablet from Dholavira, Kutch, Gujarat, suggesting child sacrifice (lower picture) connected with crocodile cult (upper picture). After Parpola 2011: 41 fig. 48 (sketch AP). 'Crocodile in the Indus civilization and later south Asian traditions'. In Linguistics, archaeology and the human past: occasional paper 12, ed. Toshiki Osada & Hitoshi Endo. Pp. 1-58. Kyoto: Indus Project, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature.

To compare the details provided by AP's sketch on this Fig. 16, I reproduce below a photograph of the tablet:

Even assuming that a seated person on the lower sketch figure with raised arms carries 'children' I do not see how Asko Parpola (AP the sketch-maker) can jump to the conclusion of 'suggested child sacrifice'.

Even assuming that a seated person on the lower sketch figure with raised arms carries 'children' I do not see how Asko Parpola (AP the sketch-maker) can jump to the conclusion of 'suggested child sacrifice'.

Dholavira molded terracotta tablet with Meluhha hieroglyphs written on two sides.

Some readings:

Hieroglyph: Ku. ḍokro, ḍokhro ʻ old man ʼ; B. ḍokrā ʻ old, decrepit ʼ, Or. ḍokarā; H. ḍokrā ʻ decrepit ʼ; G. ḍokɔ m. ʻ penis ʼ, ḍokrɔ m. ʻ old man ʼ, M. ḍokrā m. -- Kho. (Lor.) duk ʻ hunched up, hump of camel ʼ; K. ḍọ̆ku ʻ humpbacked ʼ perh. < *ḍōkka -- 2. Or. dhokaṛa ʻ decrepit, hanging down (of breasts) ʼ.(CDIAL 5567). M. ḍhẽg n. ʻ groin ʼ, ḍhẽgā m. ʻ buttock ʼ. M. dhõgā m. ʻ buttock ʼ. (CDIAL 5585). Glyph: Br. kōnḍō on all fours, bent double. (DEDR 204a) Rebus: kunda ‘turner’ kundār turner (A.); kũdār, kũdāri (B.); kundāru (Or.); kundau to turn on a lathe, to carve, to chase; kundau dhiri = a hewn stone; kundau murhut = a graven image (Santali) kunda a turner’s lathe (Skt.)(CDIAL 3295) Tiger has head turned backwards. క్రమ్మర krammara. adv. క్రమ్మరిల్లు or క్రమరబడు Same as క్రమ్మరు (Telugu). Rebus: krəm backʼ(Kho.)(CDIAL 3145) karmāra ‘smith, artisan’ (Skt.) kamar ‘smith’ (Santali) Hieroglyph: krəm backʼ(Khotanese)(CDIAL 3145) Rebus: karmāra ‘smith, artisan’ (Skt.) kamar ‘smith’ (Santali)

Hieroglyphs to children held aloft on a seated person's hands: dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' kuṛī 'girl, child' Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) kuṛī f. ‘fireplace’ (H.); krvṛi f. ‘granary (WPah.); kuṛī, kuṛohouse, building’(Ku.)(CDIAL 3232) kuṭi ‘hut made of boughs’ (Skt.) guḍi temple (Telugu)

Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn; Ka. kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr horn Tu. kōḍů, kōḍu horn Ko. kṛ (obl. kṭ-)( (DEDR 2200) Paš. kōṇḍā ‘bald’, Kal. rumb. kōṇḍa ‘hornless’.(CDIAL 3508). Kal. rumb. khōṇḍ a ‘half’ (CDIAL 3792).

Rebus: koḍ 'workshop' (Gujarati)

kāruvu ‘crocodile’ Rebus: khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri)

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron', 'pañcaloha, alloy of five metals'.

Hieroglyph: dhokra ‘decrepit woman with breasts hanging down’. Rebus: dhokra kamar 'artisan caster using lost-wax technique'.

Meluhha hieroglyphs: 1. Dhokra kamar lost-wax metal caster; 2. Dance-step of Mohenjo-daro metal castkŕ̊tā -- ʻgirlʼ (RV); kuṛäˊ ʻgirlʼ (Ash.); kola ‘woman’ (Nahali); ‘wife’(Assamese). *kuḍa1 ʻ boy, son ʼ, °ḍī ʻ girl, daughter ʼ. [Prob. ← Mu. (Sant. Muṇḍari koṛa ʻ boy ʼ, kuṛi ʻ girl ʼ, Ho koa, kui, Kūrkū kōn, kōnjē); or ← Drav. (Tam. kur̤a ʻ young ʼ, Kan.koḍa ʻ youth ʼ) T. Burrow BSOAS xii 373. Prob. separate from RV. kŕ̊tā -- ʻ girl ʼ H. W. Bailey TPS 1955, 65. -- Cf. kuḍáti ʻ acts like a child ʼ Dhātup.] NiDoc. kuḍ'aǵa ʻ boy ʼ, kuḍ'i ʻ girl ʼ; Ash. kūˊṛə ʻ child, foetus ʼ, istrimalī -- kuṛäˊ ʻ girl ʼ; Kt. kŕū, kuŕuk ʻ young of animals ʼ; Pr. kyútru ʻ young of animals, child ʼ, kyurú ʻ boy ʼ,kurīˊ ʻ colt, calf ʼ; Dm. kúŕa ʻ child ʼ, Shum. kuṛ; Kal. kūŕ*lk ʻ young of animals ʼ; Phal. kuṛĭ̄ ʻ woman, wife ʼ; K. kūrü f. ʻ young girl ʼ, kash. kōṛī, ram. kuṛhī; L. kuṛā m. ʻ bridegroom ʼ,kuṛī f. ʻ girl, virgin, bride ʼ, awāṇ. kuṛī f. ʻ woman ʼ; P. kuṛī f. ʻ girl, daughter ʼ, P. bhaṭ. WPah. khaś. kuṛi, cur. kuḷī, cam. kǒḷā ʻ boy ʼ, kuṛī ʻ girl ʼ; -- B. ã̄ṭ -- kuṛā ʻ childless ʼ (ã̄ṭa ʻ tight ʼ)? -- X pṓta -- 1: WPah. bhad. kō ʻ son ʼ, kūī ʻ daughter ʼ, bhal. ko m., koi f., pāḍ.kuā, kōī, paṅ. koā, kūī. (CDIAL 3245)

Roots of Bhāratam Janam have to be traced from the banks of Rivers Sarasvati and Sindhu identifying their life-activity as metalworkers, metalcasters who made भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. भरताचें भांडें (p. 603) [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metal भरत. 2 See भरिताचें भांडें.भरती (p. 603) [ bharatī ] a Composed of the metal भरत. (Marathi. Moleworth).

Cognate etyma (semantics of alloy) of Indian sprachbund: bhāraṇ = to bring out from a kiln (G.) bāraṇiyo = one whose profession it is to sift ashes or dust in a goldsmith’s workshop (G.lex.) In the Punjab, the mixed alloys were generally called, bharat (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin). In Bengal, an alloy called bharan or toul was created by adding some brass or zinc into pure bronze. bharata = casting metals in moulds; bharavum = to fill in; to put in; to pour into (G.lex.) Bengali. ভরন [ bharana ] n an inferior metal obtained from an alloy of coper, zinc and tin. baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

Seal published by Omananda Saraswati. In Pl. 275: Omananda Saraswati 1975. Ancient Seals of Haryana (in Hindi). Rohtak.

Seal published by Omananda Saraswati. In Pl. 275: Omananda Saraswati 1975. Ancient Seals of Haryana (in Hindi). Rohtak. This pictorial motif gets normalized in Indus writing system as a hieroglyph sign: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) Tir. mar -- kaṇḍḗ ʻ back (of the body) ʼ; S. kaṇḍo m. ʻ back ʼ, L. kaṇḍ f., kaṇḍā m. ʻ backbone ʼ, awāṇ. kaṇḍ, °ḍī ʻ back ʼH. kã̄ṭā m. ʻ spine ʼ, G. kã̄ṭɔ m., M. kã̄ṭā m.; Pk. kaṁḍa -- m. ʻ backbone ʼ.(CDIAL 2670) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) The hieroglyph ligature to convey the semantics of ‘bone’ and rebus reading is: ‘four short numeral strokes ligature’ |||| Numeral 4: gaṇḍa 'four' Rebus: kaṇḍa 'furnace, fire-altar' (Santali)

This pictorial motif gets normalized in Indus writing system as a hieroglyph sign: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) Tir. mar -- kaṇḍḗ ʻ back (of the body) ʼ; S. kaṇḍo m. ʻ back ʼ, L. kaṇḍ f., kaṇḍā m. ʻ backbone ʼ, awāṇ. kaṇḍ, °ḍī ʻ back ʼH. kã̄ṭā m. ʻ spine ʼ, G. kã̄ṭɔ m., M. kã̄ṭā m.; Pk. kaṁḍa -- m. ʻ backbone ʼ.(CDIAL 2670) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) The hieroglyph ligature to convey the semantics of ‘bone’ and rebus reading is: ‘four short numeral strokes ligature’ |||| Numeral 4: gaṇḍa 'four' Rebus: kaṇḍa 'furnace, fire-altar' (Santali)This is one possible explanation for the ancient name of the Hindu nation: Bhāratam, mentioned in R̥gveda – the Bhāratam janam were metalworkers producingbharat mixed alloy of copper, zinc and tin.

bharatiyo = a caster of metals; a brazier; bharatar, bharatal, bharataḷ = moulded; an article made in a mould; bharata = casting metals in moulds; bharavum = to fill in; to put in; to pour into (Gujarati) bhart = a mixed metal of copper and lead; bhartīyā = a brazier, worker in metal; bhaṭ, bhrāṣṭra = oven, furnace (Sanskrit.)

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

September 3, 2015

https://www.scribd.com/doc/277981068/Itih%C4%81sa-of-Bh%C4%81ratam-Janam-Through-Indus-Script-and-Maritime-Tin-Route

Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam Through Indus Script and Maritime Tin Route by Srini Kalyanaraman

https://www.scribd.com/doc/277987971/Parama-Hamsa

https://www.scribd.com/doc/277987971/Parama-Hamsa