Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/q9z5mje

Rove goat kid, one month old. A two-month-old goat kid in a field of capeweed.

A kid as a hieroglyph is repeated on tens of seals of Dilmun and Persian Gulf. What does the kid as a hieroglyph signify?

It signifies a hard metal alloy.

This note provides examples of Indus Script inscriptions which are technical product descriptions of a smithy/forge.

Note: As demonstrated by hundreds of cuneiform clay tablets of Kanesh, Kultepe of Ancient Near East, Indus Script hieroglyhphs (as production speciications) are complemented by inscriptions in cuneiform Akkadian to provide additional bill of lading information such as contracting trade partners and contract conditions.

Clearly, the hieroglyphs of Indus Script are created by very literate artisans who were experimenting during the Bronze Age with invention of new metal alloys and with techniques of metalcastings using techniques such as cire perdue (lost-wax). It will be a non-falsifiable hypothesis, a faith-based statement to aver that the hieroglyphs are created by illiterate people and that Indus Script is not a writing system. A writing system which could convey production specifications of products using about 500 hieroglyphs as texts, construction of hieroglyph-multiplexes and over 100 hieroglyphs as pictorial hieroglyphs are outstanding evidence of a cipher for rebus-metonymy-layered Prakritam glosses for communications among Meluhha trading community with trading colonies or caravanserai or as seafaring merchants. The metalwork catalogues which emerge are veritable catalogus catalogorum of the Bronze Age competence of Meluhha (Prakritam-speaking) artisans. The Prakritam glosses yield tadbhava and tatsama in a Samskritam lexicon and lexicons of almost all ancient Indian languages which constituted a linguistic area, an Indian sprachbund of the Bronze Age.

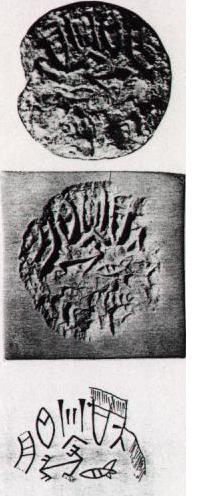

117 antelope; sun motif. Dholavira seal impression. arka 'sun' Rebus: araka, eraka 'copper, moltencast' PLUS करडूं karaḍū 'kid' Rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy'. Thus, together, the rebus message: hard alloy of copper.

117 antelope; sun motif. Dholavira seal impression. arka 'sun' Rebus: araka, eraka 'copper, moltencast' PLUS करडूं karaḍū 'kid' Rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy'. Thus, together, the rebus message: hard alloy of copper.On arka in compound expressions: அருக்கம்¹ arukkam, n. < arka. (நாநார்த்த.) 1. Copper; செம்பு (Tamil) అగసాలి (p. 0023) [ agasāli ] or అగసాలెవాడు agasāli. [Tel.] n. A goldsmith. కంసాలివాడు.(Telugu) Kannada (Kittel lexicon):

Bet Dwaraka seal. करडूं karaḍū 'kid' Rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy'. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' khond 'young bull' koD 'horn' Rebus: khond 'turner' koD 'workshop'. Thus workshop of hard alloys of copper, pewter, tin.

Bet Dwaraka seal. करडूं karaḍū 'kid' Rebus: karaḍā 'hard alloy'. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' khond 'young bull' koD 'horn' Rebus: khond 'turner' koD 'workshop'. Thus workshop of hard alloys of copper, pewter, tin. 40 Three-headed animal, plant; sun motifDholavira. Seal. Readings as above. PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. Thus, the message of the hieroglyph-multiplex is: smithy/forge for moltencast coper and hard alloys of copper, pewter, tin.

40 Three-headed animal, plant; sun motifDholavira. Seal. Readings as above. PLUS kolmo 'rice plant' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. Thus, the message of the hieroglyph-multiplex is: smithy/forge for moltencast coper and hard alloys of copper, pewter, tin.Hieroglyph: करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or karaḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं ) A kid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi. Molesworth).

Glyph: svastika; rebus: jasta ‘zinc’ (Kashmiri). Svastika: sathiyā (H.), sāthiyo (G.); satthia, sotthia (Pkt.) Rebus: svastika pewter (Kannada)

Glyph: svastika; rebus: jasta ‘zinc’ (Kashmiri). Svastika: sathiyā (H.), sāthiyo (G.); satthia, sotthia (Pkt.) Rebus: svastika pewter (Kannada) Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.

Circular seal, of steatite, from Bahrein, found at Lothal.ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'

m417 Glyph: ‘ladder’: H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ Rebus: Pa. sēṇi -- f. ʻ guild, division of army ʼ; Pk. sēṇi -- f. ʻ row, collection ʼ; śrḗṇi (metr. often śrayaṇi -- ) f. ʻ line, row, troop ʼ RV. The lexeme in Tamil means: Limit, boundary; எல்லை. நளியிரு முந்நீரேணி யாக (புறநா. 35, 1). Country, territory.

The glyphics are:

Semantics: ‘group of animals/quadrupeds’: paśu ‘animal’ (RV), pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Te.) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

Glyph: ‘six’: bhaṭa ‘six’. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

Glyph (the only inscription on the Mohenjo-daro seal m417): ‘warrior’: bhaṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’. Thus, this glyph is a semantic determinant of the message: ‘furnace’. It appears that the six heads of ‘animal’ glyphs are related to ‘furnace’ work.

The glyphics are:

Semantics: ‘group of animals/quadrupeds’: paśu ‘animal’ (RV), pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Te.) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

Glyph: ‘six’: bhaṭa ‘six’. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

Glyph (the only inscription on the Mohenjo-daro seal m417): ‘warrior’: bhaṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’. Thus, this glyph is a semantic determinant of the message: ‘furnace’. It appears that the six heads of ‘animal’ glyphs are related to ‘furnace’ work.

This guild, community of smiths and masons evolves into Harosheth Hagoyim, ‘a smithy of nations’.

It appears that the Meluhhans were in contact with many interaction areas, Dilmun and Susa (elam) in particular. There is evidence for Meluhhan settlements outside of Meluhha. It is a reasonable inference that the Meluhhans with bronze-age expertise of creating arsenical and bronze alloys and working with other metals constituted the ‘smithy of nations’, Harosheth Hagoyim.

Dilmun seal from Barbar; six heads of antelope radiating from a circle; similar to animal protomes in Failaka, Anatolia and Indus. Obverse of the seal shows four dotted circles. [Poul Kjaerum, The Dilmun Seals as evidence of long distance relations in the early second millennium BC, pp. 269-277.] A tree is shown on this Dilmun seal.

Glyph: ‘tree’: kuṭi ‘tree’. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali).

It appears that the Meluhhans were in contact with many interaction areas, Dilmun and Susa (elam) in particular. There is evidence for Meluhhan settlements outside of Meluhha. It is a reasonable inference that the Meluhhans with bronze-age expertise of creating arsenical and bronze alloys and working with other metals constituted the ‘smithy of nations’, Harosheth Hagoyim.

Dilmun seal from Barbar; six heads of antelope radiating from a circle; similar to animal protomes in Failaka, Anatolia and Indus. Obverse of the seal shows four dotted circles. [Poul Kjaerum, The Dilmun Seals as evidence of long distance relations in the early second millennium BC, pp. 269-277.] A tree is shown on this Dilmun seal.

Glyph: ‘tree’: kuṭi ‘tree’. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali).

baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'

Izzat Allah Nigahban, 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, The University Museum, UPenn, p. 97. furnace’ Fig.96a.

There is a possibility that this seal impression from Haft Tepe had some connections with Indian hieroglyphs. This requires further investigation. “From Haft Tepe (Middle Elamite period, ca. 13th century) in Ḵūzestān an unusual pyrotechnological installation was associated with a craft workroom containing such materials as mosaics of colored stones framed in bronze, a dismembered elephant skeleton used in manufacture of bone tools, and several hundred bronze arrowpoints and small tools. “Situated in a courtyard directly in front of this workroom is a most unusual kiln. This kiln is very large, about 8 m long and 2 and one half m wide, and contains two long compartments with chimneys at each end, separated by a fuel chamber in the middle. Although the roof of the kiln had collapsed, it is evident from the slight inturning of the walls which remain in situ that it was barrel vaulted like the roofs of the tombs. Each of the two long heating chambers is divided into eight sections by partition walls. The southern heating chamber contained metallic slag, and was apparently used for making bronze objects. The northern heating chamber contained pieces of broken pottery and other material, and thus was apparently used for baking clay objects including tablets . . .” (loc.cit. Bronze in pre-Islamic Iran, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-i Negahban, 1977; and forthcoming).

Many of the bronze-age manufactured or industrial goods were surplus to the needs of the producing community and had to be traded, together with a record of types of goods and types of processes such as native metal or minerals, smelting of minerals, alloying of metals using two or more minerals, casting ingots, forging and turning metal into shapes such as plates or vessels, using anvils, cire perdue technique for creating bronze statues – in addition to the production of artifacts such as bangles and ornaments made of śankha or shell (turbinella pyrum), semi-precious stones, gold or silver beads. Thus writing was invented to maintain production-cum-trade accounts, to cope with the economic imperative of bronze age technological advances to take the artisans of guilds into the stage of an industrial production-cum-trading community.

Tablets and seals inscribed with hieroglyphs, together with the process of creating seal impressions took inventory lists to the next stage of trading property items using bills of lading of trade loads of industrial goods. Such bills of lading describing trade loads were created using tablets and seals with the invention of writing based on phonetics and semantics of language – the hallmark of Indian hieroglyphs.

Izzat Allah Nigahban, 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, The University Museum, UPenn, p. 97. furnace’ Fig.96a.

There is a possibility that this seal impression from Haft Tepe had some connections with Indian hieroglyphs. This requires further investigation. “From Haft Tepe (Middle Elamite period, ca. 13th century) in Ḵūzestān an unusual pyrotechnological installation was associated with a craft workroom containing such materials as mosaics of colored stones framed in bronze, a dismembered elephant skeleton used in manufacture of bone tools, and several hundred bronze arrowpoints and small tools. “Situated in a courtyard directly in front of this workroom is a most unusual kiln. This kiln is very large, about 8 m long and 2 and one half m wide, and contains two long compartments with chimneys at each end, separated by a fuel chamber in the middle. Although the roof of the kiln had collapsed, it is evident from the slight inturning of the walls which remain in situ that it was barrel vaulted like the roofs of the tombs. Each of the two long heating chambers is divided into eight sections by partition walls. The southern heating chamber contained metallic slag, and was apparently used for making bronze objects. The northern heating chamber contained pieces of broken pottery and other material, and thus was apparently used for baking clay objects including tablets . . .” (loc.cit. Bronze in pre-Islamic Iran, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-i Negahban, 1977; and forthcoming).

Many of the bronze-age manufactured or industrial goods were surplus to the needs of the producing community and had to be traded, together with a record of types of goods and types of processes such as native metal or minerals, smelting of minerals, alloying of metals using two or more minerals, casting ingots, forging and turning metal into shapes such as plates or vessels, using anvils, cire perdue technique for creating bronze statues – in addition to the production of artifacts such as bangles and ornaments made of śankha or shell (turbinella pyrum), semi-precious stones, gold or silver beads. Thus writing was invented to maintain production-cum-trade accounts, to cope with the economic imperative of bronze age technological advances to take the artisans of guilds into the stage of an industrial production-cum-trading community.

Tablets and seals inscribed with hieroglyphs, together with the process of creating seal impressions took inventory lists to the next stage of trading property items using bills of lading of trade loads of industrial goods. Such bills of lading describing trade loads were created using tablets and seals with the invention of writing based on phonetics and semantics of language – the hallmark of Indian hieroglyphs.

9351; Nippur; ca. 13th cent. BC; white stone; zebu bull and two pictograms. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'. goTa 'round object' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'; bartI 'partridge/quail' (Khotanese); bharati id. (Samskritam) Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, the message is: kuThi poLa khoTa bharata smelter for magnetite, alloy ingot (copper, pewter, tin alloy).

9351; Nippur; ca. 13th cent. BC; white stone; zebu bull and two pictograms. poLa 'zebu' Rebus: poLa 'magnetite'. goTa 'round object' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'; bartI 'partridge/quail' (Khotanese); bharati id. (Samskritam) Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. kuTi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. Thus, the message is: kuThi poLa khoTa bharata smelter for magnetite, alloy ingot (copper, pewter, tin alloy). 9851; Louvre Museum; Luristan; unglazed, gray steatite; short-horned bull and 4 pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; PLUS meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' thus, the pair of 'bodies' signify: iron cast metal.

9851; Louvre Museum; Luristan; unglazed, gray steatite; short-horned bull and 4 pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal'; PLUS meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron' thus, the pair of 'bodies' signify: iron cast metal. dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoTa 'ingot'. Thus, cast metal ingot. (Next two hieroglyhphs not legible).

![]()

![]() 9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge) sã̄gāḍ lathe, portable furnace Rebus: stone-cutter sangatarāśū ). sanghāḍo (Gujarati) cutting stone, gilding (Gujarati); sangsāru karaṇu = to stone (Sindhi) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati) sangaDa 'cargo boat' sanghAta 'collection of articles'; samghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge) sã̄gāḍ lathe, portable furnace Rebus: stone-cutter sangatarāśū ). sanghāḍo (Gujarati) cutting stone, gilding (Gujarati); sangsāru karaṇu = to stone (Sindhi) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati) sangaDa 'cargo boat' sanghAta 'collection of articles'; samghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge) sã̄gāḍ lathe, portable furnace Rebus: stone-cutter sangatarāśū ). sanghāḍo (Gujarati) cutting stone, gilding (Gujarati); sangsāru karaṇu = to stone (Sindhi) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati) sangaDa 'cargo boat' sanghAta 'collection of articles'; samghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)

9908. Iraq museum; glazed steatite; perhaps from an Iraqi site; the one-horned bull, the standard are below a six-sign inscription. kõdā 'young bull calf' Rebus: kõdā 'turner-joiner' (forge) sã̄gāḍ lathe, portable furnace Rebus: stone-cutter sangatarāśū ). sanghāḍo (Gujarati) cutting stone, gilding (Gujarati); sangsāru karaṇu = to stone (Sindhi) sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati) sangaDa 'cargo boat' sanghAta 'collection of articles'; samghAta 'adamantine glue' (Varahamihira)aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' PLUS kANDa 'notch' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; ayas 'fish' aduru' native metal' (unsmelted) eraka 'nave of wheel' Rebus: eraka 'copper, moltencast' arA 'spokes' Rebus: Ara 'brass'.

![]() Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron'

Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron'![]() 3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.![]()

![]() 9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

![]() 9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'![]() 9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.

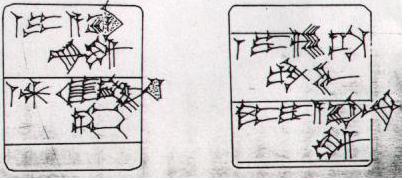

9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.![]() Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim)

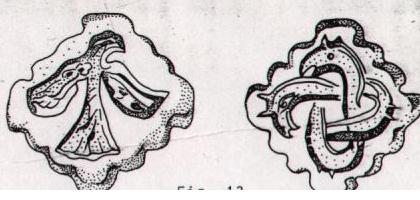

Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim)![]() Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

![]() 9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'![]() Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron'

Foroughi collection; Luristan; medium gray steatite; bull, crescent, star and net square; of the Dilmun seal type. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'; khaNDa 'square divisions' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements'; meDha 'polar star' Rebus: meD 'iron' 3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

3255; Louvre Museum; Luristan; light yellow stone; seal impression; one side shows four eagles; the eagles hold snakes in their beaks; at the center is a human figure with outstretched limbs; obverse of the seal shows an animal, perhaps a hyena or boar striding across the field, with a smaller animal of the same type depicted above it; comparable to the seal found in Harappa, Vats 1940, II: Pl. XCI.255.

garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' gaNDa 'four' Rebus: khaNDa 'metal implements' arye 'lion' Rebus: Ara 'brass'.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'.

9701; Failaka; unglazed steatite; an arc of four pictograms above the hindquarter of a bull. meD 'body' Rebus: meD 'iron'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop' goTa 'seed' Rebus: khoT 'ingot' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'forge, smithy'. kamaDa 'bow' Rebus: kammaTa 'mint, coiner'. 9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'

9702; seal, impression, inscription; Failaka; brownish-grey unglazed steatite; Indus pictograms above a short-horned bull. aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron, metal' kanca 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze' 9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.

9602; seal, impression; Qala'at al-Bahrain; green steatite; short-horned bull and five pictograms. Found in association with an Isin-Larsa type tablet bearing three Amorite names. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'. Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim)

Qala'at al-Bahrain; ca. 2050-1900 BC; tablet, found in the same level where 8 Dilmun seals and six Harappan type weights were found. Three Amorite names are: Janbi-naim; Ila-milkum; Jis.i-tambu (son of Janbi-naim) Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead'

Two seals from Gonur 1 in the Murghab delta; dark brown stone (Sarianidi 1981 b: 232-233, Fig. 7, 8); eagle engraced on one face. garuDa 'eagle' Rebus: karaDa 'hard alloy' nAga 'serpent' Rebus: nAga 'lead' 9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin'

9601; Qala'at al-Bahrain; light-grey steatite; hindquarters of a bull and two pictograms. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Seal impression; Dept. of Antiquities, Bahrain; three Harapan-style bulls. barad 'ox' Rebus: bharata 'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.Hieroglyph: meṇḍā ʻlump, clotʼ (Oriya)

On mED 'copper' in Eurasian languages:

Wilhelm von Hevesy wrote about the Finno-Ugric-Munda kinship, like "Munda-Magyar-Maori, an Indian link between the antipodes new tracks of Hungarian origins" and "Finnisch-Ugrisches aus Indien". (DRIEM, George van: Languages of the Himalayas: an ethnolinguistic handbook. 1997. p.161-162.) Sumerian-Ural-Altaic language affinities have been noted. Given the presence of Meluhha settlements in Sumer, some Meluhha glosses might have been adapted in these languages. One etyma cluster refers to 'iron' exemplified by meD (Ho.). The alternative suggestion for the origin of the gloss med 'copper' in Uralic languages may be explained by the word meD (Ho.) of Munda family of Meluhha language stream:

Sa. <i>mE~R~hE~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mE~RhE~d</i>(M).

Ma. <i>mErhE'd</i> `iron'.

Mu. <i>mERE'd</i> `iron'.

~ <i>mE~R~E~'d</i> `iron'. ! <i>mENhEd</i>(M).

Ho <i>meD</i> `iron'.

Bj. <i>merhd</i>(Hunter) `iron'.

KW <i>mENhEd</i>

@(V168,M080)

— Slavic glosses for 'copper'

Мед [Med]Bulgarian

Bakar Bosnian

Медзь [medz']Belarusian

Měď Czech

Bakar Croatian

KòperKashubian

Бакар [Bakar]Macedonian

Miedź Polish

Медь [Med']Russian

Meď Slovak

BakerSlovenian

Бакар [Bakar]Serbian

Мідь [mid'] Ukrainian[unquote]

Miedź, med' (Northern Slavic, Altaic) 'copper'.

One suggestion is that corruptions from the German "Schmied", "Geschmeide" = jewelry. Schmied, a smith (of tin, gold, silver, or other metal)(German) result in med ‘copper’.

Meluhha acculturation in Ancient Near East

Many scholars have noted the contacts between the Mesopotamian and Sarasvati-Sindhu (Indus, Hindu) Civilizations, in terms of cultural history, chronology, artefacts (beads, jewellery), pottery and seals found from archaeological sites in the two areas.

"...the four examples of round seals found in Mohenjodaro show well-supported sequences, whereas the three from Mesopotamia show sequences of signs not paralleled elsewhere in the Indus Script. But the ordinary square seals found in Mesopotamia show the normal Mohenjodaro sequences. In other words, the square seals are in the Indian language, and were probably imported in the course of trade; while the circular seals, although in the Indus script, are in a different language, and were probably manufactured in Mesopotamia for a Sumerian- or Semitic-speaking person of Indian descent..." [G.R. Hunter,1932. Mohenjodaro--Indus Epigraphy, JRAS: 466-503]

The acculturation of Meluhhans (probably, Indus people) residing in Mesopotamia in the late third and early second millennium BC, is noted by their adoption of Sumerian names (Parpola, Parpola and Brunswig 1977: 155-159).

"The adaptation of Harappan motifs and script to the Dilmun seal form may be a further indication of the acculturative phenomenon, one indicated in Mesopotamia by the adaptation of Harappan traits to the cylinder seal." (Brunswig et al, 1983, p. 110).

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

August 17, 2015

Resources:

Robert H. Brunswig, Jr. et al, New Indus Type and Related Seals from the Near East, 101-115 in: Daniel T. Potts (ed.), Dilmun: New Studies in the Archaeology and Early History of Bahrain, Berlin, Dietrich Reimer Verlag, 1983; each seal is referenced by a four-digit number which is registered in the Finnish concordance.]

Asthana, S.P. 1976. History and archaeology of India's contacts with other countires: from earliest times to 300 BC, B.R. Publications Corp., Delhi.

Bibby, T.G., 1958. The 'ancient Indian Style' Seals from Bahrain, Antiquity 33: 243-246.

During Caspers, E.C.L. 1972. Harappan trade in the Arabian Gulf in the third millennium BC, Mesopotamia 7: 167-191.

During Caspers, E.C.L. 1982. Sumerian traders and businessmen residing in the Indus Valley cities: a critical assessment of archaeological evidence, Annali 42: 337-380.

Chakrabarti, D.K. 1977. India and West Asia--an alternative approach, Man and Environment 1:25-38.

Chakrabarti, D.K. 1978. Seals as evidence of Indus-West Asia Interrelations, in D. Chattopadhyaya, ed., History and Society, Essays in Honour of Prof. Niharranjan Ray, Calcutta, p. 93-116.

Corbiau, S. 1936. An Indo-Sumerian Cylinder, Iraq 3: 100-103.

Frankfort, H. 1934. The Indus Civilization and the Near East, Annual Bibliography of Indian Archaeology VII: 1-12.

Gadd, C.J. 1932. Seals of Ancient Indian Style found at Ur, Proc. of the British Academy, XVII: 191-210.

Gadd, C.J. and Smith, S. 1924. The new links between Indian and Babylonian Civilizations, Illus. London News, Oct. 4, p. 614-616.

Gibson, McG. 1976. The Nippur expedition, The Oriental Institute of the Univ. of Chicago Annual Report 1975/76: 26,28.

Kjaerum, P. 1980. Seals of Dilmun-Type from Failaka, Kuwait, PSAS 10: 45-53.

Kjaerum, P. 1983. The Stamp and Cylinder Seals 1:1, Failaka/Dilmun: The second millennium settlements, Jutland Arch. Soc. Publ. XVII:1, Aarhus.

Mackay, E.J.H. 1925. Sumerian connections with Ancient India, JRAS: 696-701.

Mackay, E.J.H. 1931. Further Excavations at Mohenjo-daro, New Delhi.

Marshall, Sir J. 1931. Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, London.

Masson, V.M. and Sarianidi, V.I. 1972. Central Asia, Thames and Hudson, London.

Nissen, H.J. 1982. Linking distanct areas archaeologically, paper read at the 1st International Conference on Pakistan Archaeology, Peshawar.

Parpola, A. 1984. New correspondences between Harappan and Near Eastern Glyptic Art, in B. Allchin, ed., South Asian Archaeology 1981, Univ. of Cambridge Oriental Publications 34, Cambridge.

Parpola, S., Parpola, A., and Brunswig, R.H. Jr. 1977. The Meluhha village: evidence of acculturation of Harappan traders in late third millennium Mesopotamia? JESHO XX: 129-165.

Ratnagar, S. 1981. Encounters, the westerly trade of the Harappan Civilization, Oxford Univ. Press, Delhi.

Tosi, M. 1982. A possible Harappan Seaport in Eastern Arabia: Ra's Al Junayz in the Sultanate of Oman, paper read at the 1st International Conference on Pakistan Archaeology, Peshawar.

Vats, M.S. 1940. Excavations at Harappa, Calcutta.

Wheeler, Sir M. 1968. The Indus Civilization, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

Yule, P. 1981. Zu den Beziehungen zwischen Mesopotamien und dem Indusgebiet im 3. und beginnenden 2. Jahrtausend, Allgemeine und Vergleichende Archaologie Kolloquien 1:191-205.