Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/othgjh7

I submit with all humility that it is no longer necessary to add a footnote to narratives of Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam that Indus Script has not been deciphered so far. The entire Indus Script Corpora is a writing system based on Meluhha speech of Indian sprachbund (speech union). The writing system was called mlecchita vikalpa (i.e. Meluhha cipher), by Vātsyāyana. The Corpora of inscriptions encoded Proto-Indo-European or Proto-Indo-Aryan speech, variously called Prākritam or Des'i. For a documentation on Des'i, see: Sharma, Sheo Murti, 1980, Ācārya Hemacandra racita Deśī nāma mālā kā bhāshā vaijñānika adhyayana, Jayapura, Devanagara Prakasana.

![]()

In the monumental work Ācārya Hemacandra identifies one gloss: ibbo. This is explained semantically as 'merchant'. This is signified by the hieroglyph ibha, 'elephant'. ibbo (merchant of ib 'iron') ibha 'elephant' (Samskritam) Rebus: ibbho,,,Hemacandra, Desinamamala, vaṇika). ib 'iron' (Santali) karibha 'elephant' (Samskritam). See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/sanchi-stupa-message-karuja-silpi-gana.html

![]()

![]() Photo ca. 1910.Hieroglyph multiplex capital on the architrave, toraṇa of Sanchi stupa northern gateway: four elephants hold aloft the spoked-wheel standard. [This can also be interpreted as upholding the wheel of dharma-dhamma if the art historian's interpretation of aniconic representations represented the reality of the times.]

Photo ca. 1910.Hieroglyph multiplex capital on the architrave, toraṇa of Sanchi stupa northern gateway: four elephants hold aloft the spoked-wheel standard. [This can also be interpreted as upholding the wheel of dharma-dhamma if the art historian's interpretation of aniconic representations represented the reality of the times.]

The centre-piece on a Sanchi torana shows four elephants holding aloft the standard of spoked wheel. The rebus-metonymy-layered-cipher provides a reading: ibbo vaThAra'merchant quarter of the town.'

In Besanagara as a trading center at a trade route intersection, the hieroglyph multiplex denoted collection of materials traded at the vaThAra 'quarter of the town' -- denoted by the hieroglyph: circle with spokes: vaTTa, vRtta 'circle' PLUS Ara 'spokes'. Just as the Dholavira sign board announced metalwork at Kotda of Gujarat, the pillars with capitals in Besanagara broadcast the competence of artificers in artistic working with metals as armourers, as brass-workers, lapidaries, metalsmiths, cire perdue metalcasters. நகரவிடுதி nakara-viṭuti , n. < நகரம்¹ +. A lodging-place specially intended for Nāṭṭuk- kōṭṭai Cheṭṭies; நாட்டுக்கோட்டை நகரத்தார் வந்து தங்குவதற்காக ஏற்பட்ட கட்டடம். Nāṭ. Cheṭṭi. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/itihasa-of-bharatam-janam-makara-manda.html

This monograph argues that the decipherment of Indus Script Corpora as metalwork catalogues, catalogus catalogorum is validated -- indeed, proved --in the context of reading the Corpora as hypertexts. The tradition of Indus writing system continues into the historical periods as evidenced by the continued use of the characteristic principles of the writing system in the unique hieroglyph multiplexes displayed on sculptural artifacts of the Kushana and Satavahana periods and on tens of thousands of punch-marked coins and cast coins (pace the documentation of 342 symbols identified by W. Theobald on punch-marked coins, many of which are based on Indus Script prototypes).

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/an-object-lesson-for-art-historians.html Monographs of Theobald (1890, 1901) list 342 symbols deployed on punch-marked coins. These symbols also survive on later coinages of Ujjain or Eran or of many janapadas. One view is that early punch-marked coinage in Bharatam is datable to 10th century BCE, predating Lydia's electrum coin of 7th cent. BCE. “The coins to which these notes refer, though presenting neither king’s names, dates of inscription of any sort, are nevertheless very interesting not only from their being the earliest money coined in India, and of a purely indigenous character, but from their being stamped with a number of symbols, some of which we can, with the utmost confidence, declare to have originated in distant lands and inthe remotest antiquity…The coins to which I shall confine my remarks are those to which the term ‘punch -marked’ properly applies. The ‘punch’ used to produce these coins differed from the ordinary dies which subsequently came into use, in that they covered only a portion of the surface of the coin or ‘blank’, and impressed only one, of the many symbols usually seen on their pieces…One thing which is specially striking about most of the symbols representing animals is, the fidelity and spirit with which certain portions of it may be of an animal, or certain attitudes are represented…Man, Woman, the Elephant, Bull, Dog, Rhinoceros,Goat, Hare, Peacock, Turtle, Snake, Fish, Frog, are all recognizable

at a glance…First, there is the historical record of Quintus Curtius, who describes the Raja of Taxila (the modern Shahdheri, 20miles north-west from Rawal Pindi) as offering Alexander 80 talents of coined silver (‘signati argenti’). Now what other, except these punch-marked coins could these pieces of coined silver have been? Again, the name by which these coins are spoken of in the Buddhist sutras, about 200 BCE was ‘purana’, which simply signies ‘old’, whence the General argunes that the word ‘old as applied to the indigenous ‘karsha’,was used to distinguish it from the new and more recent issues of the Greeks. Then again a mere comparison of the two classes of coins almost itself suffices to refute the idea of the Indian coins being derived from the Greek. The Greek coins present us with a portrait of the king, with his name and titles in two languages together with a great number and variety of monograms indicating, in many instances where they have been deciphered by the ingenuity and perseverance of General Cunningham and others, the names of the mint cities where the coins were struck, and it is our ignorance of the geographical names of the period that probably has prevented the whole of them receiving their proper attribution; but with the indigenous coins it is far otherwise, as they display neither king’s head, neame, titles or mongrams of any description…It is true that General Cunningham considers that many of these symbols, though not monograms in a strict sense, are nevertheless marks which indicate the mints where the coins were struck or the tribes among whom they were current, and this contention in no wise invalidates the supposition contended for by me either that the majority of them possess an esoteric meaning or have originated in other lands at a period anterior to the

ir adoption for the purpose they fulfil on the coins in Hindustan.”

(W. Theobald, 1890, Notes on some of the symbols found on the punch-marked coins of Hindustan, and on their relationship to the archaic symbolism of other races and distant lands, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Bombay Branch (JASB), Part 1. History , Literature etc., Nos. III & IV, 1890, pp. 181 to 184) W. Theobald, Symbols on punch-marked coins of Hindustan (1890,1901).

See: Fabri, CL, The punch-marked coins: a survival of the Indus Civilization, 1935, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press. pp.307-318. A comparison of Punch-marked hieroglyphs with Indus Script inscriptions:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

This follows the insightful, scintillating presentation by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale which presents an exposition of art appreciation of Indus Script Corpora with particular reference to orthographic fidelity to signify hypertext components on inscriptions. A paper by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale on composite Indus creatures and their meaning: Harappa Chimaeras as 'Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some Thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization at http://a.harappa.com/content/harappan-chimaeras

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/hieroglyphmultiplextext-sagad-vakyam.html In this post, it has been argued that the hypertexts of pictorial motifs on Indus Script Corpora discussed by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale should be extended to hieroglyphs as 'signs' and ligatured hieroglyphs as 'signs' on 'texts' of the Indus inscriptions. The entire Indus Script Corpora consist of hieroglyph multiplexes -- using hieroglyphs as components -- and hence, the comparison with hypertexts need not be restricted to pictorial motifs or field symbols of Indus inscriptions. See also: Massimo Vidale, 2007, 'The collapse melts down: a reply to Farmer, Sproat and Witzel', East and West, vol. 57, no. 1-4, pp. 333 to 366).Mirror: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/document-preview.aspx?doc_id=9163376 The use of the phrase 'hypertexts' in the context of Indus Script is apposite because, the entire Indus Script Corpora is founded on rebus-metonymy-layered representations of Meluhha glosses from Indian sprachbund, speech area of ancient Bhāratam Janam of the Bronze Age.

Since the entire Indus Scrip Corpora constitute metalwork catalogues, it is but natural that the Indus Script continuum is more pronounced in the array of symbols used by mints from Taxila to Karur. This continuum reinforces the validity of decipherment of the hypertexts of the Corpora. See: https://www.academia.edu/

Many hieroglyphs of Indus Script Corpora continue to be used in historical periods:

![]()

From a review of Indus Script Corpora of nearly 7000 inscriptions, the nature of Indus writing system is defined, while validating decipherment as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork by Bronze Age artisans of Indian sprachbund.

The Corpora will expand by over approximately 10,000 inscriptions if the hieroglyphs (so-called symbols such as svastika, tree-on-railing, elephant, tiger, fish, crocodile, srivatsa) deployed on punch-marked coins, cast coins and sculptural friezes and artifacts such as Begram ivories, from sites such as Bharhut or Sanchi stupas, Kankali-Tila or Mathura AyAgapaTTa or artifacts of Candi Sukuh, Candi Setho, Dong Son Bronze drums, are taken into reckoning as Indus Writing tradition continuum (either used as hieroglyphs or used together with Brahmi or Kharoshthi syllabic scripts providing additional inscriptions, say, names of people or titles or references to other texts such as Jataka tales in Bauddham tradition).

1. Composed of hieroglyph elements as pictorial motifs and signs on texts; thus there are two categories of hieroglyphs: pictorial hieroglyphs and sign hieroglyphs

2. Orthographic construction of hieroglyph multiplexes using hieroglyph elements

3. Rebus-metonymy-layer to signify metalwork catalogues

4. Deciphered plain Meluhha or Indian sprachbund speech texts from hieroglyphmultiplex cipher texts (i.e. hypertexts with both a) hieroglyphs on pictorial motifs and b) hieroglyphs as signs on texts)

This definition will be explained in this note identifying some characteristic principles governing design features of the Indus writing system.

1. A good example of constructed orthography of hieroglyph multiplex is a seal impression from Ur identified by CJ Gadd and interpreted by GR Hunter:

![Takṣat vāk, ‘incised speech’ -- Evidence of Indus writing of ...]()

The ellipse is signified by Meluhha gloss with rebus reading indicating the artisan's competence as a professional: kōnṭa 'corner' (Nk.); kōṇṭu angle, corner (Tu.); rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) Alternative reading; kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze'.

kõdā is a metals turner, a mixer of metals to create alloys in smelters.

The signifiers are the hieroglyph components: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal'; meḍha ‘polar star’ rebus: meḍ ‘iron’; kōnṭa 'corner' rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal').

The entire hieroglyph multiplex stands deciphered: kõdā, 'metals turner' (with) meḍ ‘iron’ kuṭhi '

smelter', kuṭila, 'tin metal'.

2. This hieroglyph multiplex of the Ur Seal Impression confirms the rebus-metonymy-layered cipher of Meluhha glosses related to metalwork.

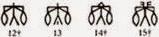

3. A characteristic feature of Indus writing system unravels from this example: what is orthographically constructed as a pictorial motif can also be deployed as a 'sign' on texts of inscriptions. This is achieved by a stylized reconstruction of the pictorial motif as a 'sign' which occurs with notable frequency on Indus Script Corpora -- with orthographic variants (Signs 12, 13, 14).

Identifying Meluhha gloss for parenthesis hieroglyph or ( ) split ellipse: குடிலம்¹ kuṭilam, n. < kuṭila. 1. Bend curve, flexure; வளைவு. (திவா.) (Tamil) In this reading, the Sign 12 signifies a specific smelter for tin metal: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/ kuṭila, 'tin (bronze)metal; kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) [cf. āra-kūṭa, ‘brass’ (Samskritam) See: http://download.docslide.us/uploads/check_up03/192015/5468918eb4af9f285a8b4c67.pdf

It will be seen from Sign 15 that the basic framework of a water-carrier hieroglyph (Sign 12) is superscripted with another hieroglyph component, Sign 342: 'Rim of jar' to result in Sign 15. Thus, Sign 15 is composed of two hieroglyph components: Sign 12 'water-carrier' hieroglyph; Sign 342: "rim-of-jar' hieroglyph (which constitutes the inscription on Daimabad Seal 1).

kaṇḍ kanka ‘rim of jar’; Rebus: karṇaka ‘scribe’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’. Thus the ligatured Glyph is decoded: kaṇḍ karṇaka ‘furnace scribe'

![]() Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Each hieroglyph component of Sign 15 is read in rebus-metonymy-layered-meluhha-cipher: Hieroglyph component 1: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal'. Hieroglyph component 2: kanka, kārṇī-ka 'rim-of-jar' rebus: kanka, kārṇī-ka m. ʻsupercargo of a shipʼ 'scribe'.

Thus, the hieroglyph multiplex on m1405 is read rebus from r.: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka eraka bharata pattar'goldsmith-merchant guild -- smelting furnace account (scribe), molten cast metal infusion, alloy of copper, pewter, tin.'

Sign 13 is a composition of hieroglyph component Sign 12 kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' PLUS

Sign' which signifies hieroglyph: 'notch'. Reading the two hieroglyph components together Sign 13 reads: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal'.PLUS khāṇḍā ‘notch’ Marathi: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘metal tools, pots and pans’. Thus, the reading is: kuṭhi khāṇḍā 'smelter metal tools, pots and pans'.

Sign 14 add the hieroglyph component kōla 'arrow' or kaṇḍa ;'arrow-head' to Sign 12. This Sign 14 is deciphered as kuṭhi kaṇḍa'smelter metal tools, pots and pans' (Thus, a synonym of Sign 13) OR kuṭhi kola 'smelter, working in iron' or kuṭhi kole.l 'smelter, smithy'.

Hieroglyph: eraka‘raised arm’ (Telugu) Rebus: eraka‘copper’ (Telugu); 'moltencast' (Gujarati); metal infusion (Kannada.Tulu)

Sign 15 occurs togethe with a notch-in-fixed fish hieroglyph on Harappa 73 seal:

![]() Harappa seal (H-73)[Note: the hieroglyph ‘water carrier’ pictorial of Ur Seal Impression becomes a hieroglyph sign] Hieroglyph: fish + notch: aya 'fish' + khāṇḍā m A jag, notch Rebus: aya 'metal'+ khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kuṭi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A

Harappa seal (H-73)[Note: the hieroglyph ‘water carrier’ pictorial of Ur Seal Impression becomes a hieroglyph sign] Hieroglyph: fish + notch: aya 'fish' + khāṇḍā m A jag, notch Rebus: aya 'metal'+ khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kuṭi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. खोंडरूं [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा -cowl (Marathi); kōḍe dūḍa bull calf (Telugu); kōṛe'young bullock' (Konda) rebus: kõdā‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) [The characteristic pannier which is ligatured to the young bull pictorial hieroglyph is a synonym खोंडा 'cowl' or 'pannier').खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा , to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.) ] खोंड (p. 216) [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf.(Marathi) खोंडरूं [ khōṇḍarūṃ ] n A contemptuous form of खोंडा in the sense of कांबळा -cowl.खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A कांबळा of which one end is formed into a cowl or hood. खोंडी [ khōṇḍī ] f An outspread shovelform sack (as formed temporarily out of a कांबळा , to hold or fend off grain, chaff &c.)

खोदणें Dug. 2 Engraved, carved, sculptured. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/04/excavations-at-dholavifra-1989-2005-rs.html

The intimations of a metals turner as a scribe are also gleaned from the gloss: खोडाखोड or डी [ khōḍākhōḍa or ḍī ] f (खोडणें ) Erasing, altering, interlining &c. in numerous places: also the scratched, scrawled, and disfigured state of the paper so operated upon; खोडींव [ khōḍīṃva ] p of खोडणें v c Erased or crossed out.Marathi). खोडपत्र [ khōḍapatra ] n Commonly खोटपत्र .खोटपत्र [ khōṭapatra ] n In law or in caste-adjudication. A written acknowledgment taken from an offender of his falseness or guilt: also, in disputations, from the person confuted. (Marathi) Thus, khond 'turner' is also an engraver, scribe.

That a metals turner is engaged in metal alloying is evident from the gloss: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge. Hence 2 A lump or solid bit (as of phlegm, gore, curds, inspissated milk); any concretion or clot.खोटीचा Composed or made of खोट , as खोटीचें भांडें .

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/03/x.html

,

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/hieroglyphmultiplextext-sagad-vakyam.html Thanks to Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale who compared Indus Script 'chimaera' to 'hypertext'. A paper (2012) by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale on Composite Indus creatures and their meaning: Harappa Chimaeras as 'Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some Thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization at http://a.harappa.com/content/harappan-chimaeras

This note elaborates on this splendid insight argued archaeologically and orthographically in their monograph.

Arguments of Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale

The arguments of Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale are framed taking the example of a Mohenjo-daro seal m0300 with what they call 'symbolic hypertext' or, 'Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components':

![]()

Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components. Harappan chimera and its hypertextual components. The 'expression' summarizes the syntax of Harappan chimeras within round brackets, creatures with body parts used in their correct anatomic position (tiger, unicorn, markhor goat, elephant, zebu, and human); within square brackets, creatures with body parts used to symbolize other anatomic elements (cobra snake for tail and human arm for elephant proboscis); the elephant icon as exonent out of the square brackets symbolizes the overall elephantine contour of the chimeras; out of brackes, scorpion indicates the animal automatically perceived joining the lineate horns, the human face, and the arm-like trunk of Harappan chimeras. (After Fig. 6 in: Harappan chimaeras as 'symbolic hypertexts'. Some thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization (Dennys Frenez & Massimo Vidale, 2012)

Framework and Functions of Indus Script

The unique characteristic of Indus Script which distinguishes the writing system from Egyptian hieroglyphs are as follows:

1. On both Indus Script and Egyptian hieroglyphs, hieroglyph-multiplexes are created using hieroglyph components (which Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale call hypertextual components).

2. Indus Script denotes 'expressions or speech-words' for every hieroglyph while Egyptian hieroglyphs generally denote 'syllables' (principally consonants without vowels).

3. While Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally deployed to derive 'names of people' or 'expressions denoting administrative divisions' deploying nomes, Indus Script is NOT used for syllabic combinations which result in names of people or designations. As evidenced by the use of Brahmi or Kharoshthi script together with Indus Script hieroglyphs on tens of thousands of ancient coins, the Brahmi or Kharoshthi syllabic representations are generally used for 'names of people or designations' while Indus Script hieroglyphs are used to detail artisan products, metalwork, in particular.

The framework of Indus Script has two structures: 1) pictorial motifs as hieroglyph-multiplexes; and 2) text lines as hieroglyph-multiplexes

Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale focus attention on pictorial motifs and on m0300 seal, identify a number of hieroglyph components constituting the hieroglyph-multiplex -- on the pictorial motif of 'composite animal', seen are hieroglyph components (which they call hypertextual components): serpent (tail), scorpion, tiger, one-horned young bull, markhor, elephant, zebu, standing man (human face), man seated in penance (yogi).

The yogi seated in penance and other hieroglyphs are read rebus in archaeometallurgical terms: kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) rebus: kampaTTa 'mint'. Hieroglyph: kola 'tiger', xolA 'tail' rebus: kol 'working in iron'; kolle'blacksmith'; kolhe'smelter'; kole.l 'smithy'; kolimi 'smithy, forge'. खोड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi) rebus: khond 'turner'. dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhatu 'minerals'. bica 'scorpion' rebus: bica'stone ore'. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) mẽṛhet iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda) kara'elephant's trunk' Rebus: khar'blacksmith'; ibha'elephant' rebus: ib'iron'. Together: karaibā 'maker, builder'.

Use of such glosses in Meluhha speech can be explained by the following examples of vAkyam or speech expressions as hieroglyph signifiers and rebus-metonymy-layered-cipher yielding signified metalwork:

Example 1: mũh opening or hole (in a stove for stoking (Bi.); ingot (Santali) mũh metal ingot (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) kaula mengro ‘blacksmith’ (Gypsy) mleccha-mukha (Samskritam) = milakkhu‘copper’ (Pali) The Samskritam gloss mleccha-mukha should literally mean: copper-ingot absorbing the Santali gloss, mũh, as a suffix.

Example 2: samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari) samanom = an obsolete name for gold (Santali) [bica‘stone ore’ (Munda): meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda)].

In addition to the use of hieroglyph-components to create hieroglyph-multiplexes of pictorial motifs such as 'composite animals', the same principle of multiplexing is used also on the so-called 'signs' of texts of inscriptions.

Rebus: fire-god: @B27990. #16671. Remo <karandi>E155 {N} ``^fire-^god''.(Munda)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

m0295 Mohenjo-daro seal This is a good example of hypertext with two categories of hypertext components: 1. pictorial motif hieroglyphs; 2. text hieroglyphs called signs in Indus Script Concordances such as those of Parpola and Mahadevan.

![]() Text1386 Note how the hieroglyph components of the text are displayed in the space available on the seal after the pictorial motif hieroglyphs have been put together as part of the hypertext. The broken corner of the seal may have included other 'text hieroglyphs called signs'.

Text1386 Note how the hieroglyph components of the text are displayed in the space available on the seal after the pictorial motif hieroglyphs have been put together as part of the hypertext. The broken corner of the seal may have included other 'text hieroglyphs called signs'.

I submit with all humility that it is no longer necessary to add a footnote to narratives of Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam that Indus Script has not been deciphered so far. The entire Indus Script Corpora is a writing system based on Meluhha speech of Indian sprachbund (speech union). The writing system was called mlecchita vikalpa (i.e. Meluhha cipher), by Vātsyāyana. The Corpora of inscriptions encoded Proto-Indo-European or Proto-Indo-Aryan speech, variously called Prākritam or Des'i. For a documentation on Des'i, see: Sharma, Sheo Murti, 1980, Ācārya Hemacandra racita Deśī nāma mālā kā bhāshā vaijñānika adhyayana, Jayapura, Devanagara Prakasana.

In the monumental work Ācārya Hemacandra identifies one gloss: ibbo. This is explained semantically as 'merchant'. This is signified by the hieroglyph ibha, 'elephant'. ibbo (merchant of ib 'iron') ibha 'elephant' (Samskritam) Rebus: ibbho,,,Hemacandra, Desinamamala, vaṇika). ib 'iron' (Santali) karibha 'elephant' (Samskritam). See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/sanchi-stupa-message-karuja-silpi-gana.html

Photo ca. 1910.Hieroglyph multiplex capital on the architrave, toraṇa of Sanchi stupa northern gateway: four elephants hold aloft the spoked-wheel standard. [This can also be interpreted as upholding the wheel of dharma-dhamma if the art historian's interpretation of aniconic representations represented the reality of the times.]

Photo ca. 1910.Hieroglyph multiplex capital on the architrave, toraṇa of Sanchi stupa northern gateway: four elephants hold aloft the spoked-wheel standard. [This can also be interpreted as upholding the wheel of dharma-dhamma if the art historian's interpretation of aniconic representations represented the reality of the times.]The centre-piece on a Sanchi torana shows four elephants holding aloft the standard of spoked wheel. The rebus-metonymy-layered-cipher provides a reading: ibbo vaThAra'merchant quarter of the town.'

In Besanagara as a trading center at a trade route intersection, the hieroglyph multiplex denoted collection of materials traded at the vaThAra 'quarter of the town' -- denoted by the hieroglyph: circle with spokes: vaTTa, vRtta 'circle' PLUS Ara 'spokes'. Just as the Dholavira sign board announced metalwork at Kotda of Gujarat, the pillars with capitals in Besanagara broadcast the competence of artificers in artistic working with metals as armourers, as brass-workers, lapidaries, metalsmiths, cire perdue metalcasters. நகரவிடுதி nakara-viṭuti , n. < நகரம்¹ +. A lodging-place specially intended for Nāṭṭuk- kōṭṭai Cheṭṭies; நாட்டுக்கோட்டை நகரத்தார் வந்து தங்குவதற்காக ஏற்பட்ட கட்டடம். Nāṭ. Cheṭṭi. http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/itihasa-of-bharatam-janam-makara-manda.html

This monograph argues that the decipherment of Indus Script Corpora as metalwork catalogues, catalogus catalogorum is validated -- indeed, proved --in the context of reading the Corpora as hypertexts. The tradition of Indus writing system continues into the historical periods as evidenced by the continued use of the characteristic principles of the writing system in the unique hieroglyph multiplexes displayed on sculptural artifacts of the Kushana and Satavahana periods and on tens of thousands of punch-marked coins and cast coins (pace the documentation of 342 symbols identified by W. Theobald on punch-marked coins, many of which are based on Indus Script prototypes).

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/an-object-lesson-for-art-historians.html Monographs of Theobald (1890, 1901) list 342 symbols deployed on punch-marked coins. These symbols also survive on later coinages of Ujjain or Eran or of many janapadas. One view is that early punch-marked coinage in Bharatam is datable to 10th century BCE, predating Lydia's electrum coin of 7th cent. BCE. “The coins to which these notes refer, though presenting neither king’s names, dates of inscription of any sort, are nevertheless very interesting not only from their being the earliest money coined in India, and of a purely indigenous character, but from their being stamped with a number of symbols, some of which we can, with the utmost confidence, declare to have originated in distant lands and inthe remotest antiquity…The coins to which I shall confine my remarks are those to which the term ‘punch -marked’ properly applies. The ‘punch’ used to produce these coins differed from the ordinary dies which subsequently came into use, in that they covered only a portion of the surface of the coin or ‘blank’, and impressed only one, of the many symbols usually seen on their pieces…One thing which is specially striking about most of the symbols representing animals is, the fidelity and spirit with which certain portions of it may be of an animal, or certain attitudes are represented…Man, Woman, the Elephant, Bull, Dog, Rhinoceros,Goat, Hare, Peacock, Turtle, Snake, Fish, Frog, are all recognizable

at a glance…First, there is the historical record of Quintus Curtius, who describes the Raja of Taxila (the modern Shahdheri, 20miles north-west from Rawal Pindi) as offering Alexander 80 talents of coined silver (‘signati argenti’). Now what other, except these punch-marked coins could these pieces of coined silver have been? Again, the name by which these coins are spoken of in the Buddhist sutras, about 200 BCE was ‘purana’, which simply signies ‘old’, whence the General argunes that the word ‘old as applied to the indigenous ‘karsha’,was used to distinguish it from the new and more recent issues of the Greeks. Then again a mere comparison of the two classes of coins almost itself suffices to refute the idea of the Indian coins being derived from the Greek. The Greek coins present us with a portrait of the king, with his name and titles in two languages together with a great number and variety of monograms indicating, in many instances where they have been deciphered by the ingenuity and perseverance of General Cunningham and others, the names of the mint cities where the coins were struck, and it is our ignorance of the geographical names of the period that probably has prevented the whole of them receiving their proper attribution; but with the indigenous coins it is far otherwise, as they display neither king’s head, neame, titles or mongrams of any description…It is true that General Cunningham considers that many of these symbols, though not monograms in a strict sense, are nevertheless marks which indicate the mints where the coins were struck or the tribes among whom they were current, and this contention in no wise invalidates the supposition contended for by me either that the majority of them possess an esoteric meaning or have originated in other lands at a period anterior to the

ir adoption for the purpose they fulfil on the coins in Hindustan.”

(W. Theobald, 1890, Notes on some of the symbols found on the punch-marked coins of Hindustan, and on their relationship to the archaic symbolism of other races and distant lands, Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, Bombay Branch (JASB), Part 1. History , Literature etc., Nos. III & IV, 1890, pp. 181 to 184) W. Theobald, Symbols on punch-marked coins of Hindustan (1890,1901).

See: Fabri, CL, The punch-marked coins: a survival of the Indus Civilization, 1935, Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Cambridge University Press. pp.307-318. A comparison of Punch-marked hieroglyphs with Indus Script inscriptions:

This follows the insightful, scintillating presentation by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale which presents an exposition of art appreciation of Indus Script Corpora with particular reference to orthographic fidelity to signify hypertext components on inscriptions. A paper by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale on composite Indus creatures and their meaning: Harappa Chimaeras as 'Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some Thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization at http://a.harappa.com/content/harappan-chimaeras

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/hieroglyphmultiplextext-sagad-vakyam.html In this post, it has been argued that the hypertexts of pictorial motifs on Indus Script Corpora discussed by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale should be extended to hieroglyphs as 'signs' and ligatured hieroglyphs as 'signs' on 'texts' of the Indus inscriptions. The entire Indus Script Corpora consist of hieroglyph multiplexes -- using hieroglyphs as components -- and hence, the comparison with hypertexts need not be restricted to pictorial motifs or field symbols of Indus inscriptions. See also: Massimo Vidale, 2007, 'The collapse melts down: a reply to Farmer, Sproat and Witzel', East and West, vol. 57, no. 1-4, pp. 333 to 366).Mirror: http://www.docstoc.com/docs/document-preview.aspx?doc_id=9163376 The use of the phrase 'hypertexts' in the context of Indus Script is apposite because, the entire Indus Script Corpora is founded on rebus-metonymy-layered representations of Meluhha glosses from Indian sprachbund, speech area of ancient Bhāratam Janam of the Bronze Age.

Since the entire Indus Scrip Corpora constitute metalwork catalogues, it is but natural that the Indus Script continuum is more pronounced in the array of symbols used by mints from Taxila to Karur. This continuum reinforces the validity of decipherment of the hypertexts of the Corpora. See: https://www.academia.edu/

Many hieroglyphs of Indus Script Corpora continue to be used in historical periods:

From a review of Indus Script Corpora of nearly 7000 inscriptions, the nature of Indus writing system is defined, while validating decipherment as catalogus catalogorum of metalwork by Bronze Age artisans of Indian sprachbund.

The Corpora will expand by over approximately 10,000 inscriptions if the hieroglyphs (so-called symbols such as svastika, tree-on-railing, elephant, tiger, fish, crocodile, srivatsa) deployed on punch-marked coins, cast coins and sculptural friezes and artifacts such as Begram ivories, from sites such as Bharhut or Sanchi stupas, Kankali-Tila or Mathura AyAgapaTTa or artifacts of Candi Sukuh, Candi Setho, Dong Son Bronze drums, are taken into reckoning as Indus Writing tradition continuum (either used as hieroglyphs or used together with Brahmi or Kharoshthi syllabic scripts providing additional inscriptions, say, names of people or titles or references to other texts such as Jataka tales in Bauddham tradition).

1. Composed of hieroglyph elements as pictorial motifs and signs on texts; thus there are two categories of hieroglyphs: pictorial hieroglyphs and sign hieroglyphs

2. Orthographic construction of hieroglyph multiplexes using hieroglyph elements

3. Rebus-metonymy-layer to signify metalwork catalogues

4. Deciphered plain Meluhha or Indian sprachbund speech texts from hieroglyphmultiplex cipher texts (i.e. hypertexts with both a) hieroglyphs on pictorial motifs and b) hieroglyphs as signs on texts)

This definition will be explained in this note identifying some characteristic principles governing design features of the Indus writing system.

1. A good example of constructed orthography of hieroglyph multiplex is a seal impression from Ur identified by CJ Gadd and interpreted by GR Hunter:

Seal impression, Ur (Upenn; U.16747); dia. 2.6, ht. 0.9 cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 11-12, pl. II, no. 12; Porada 1971: pl.9, fig.5; Parpola, 1994, p. 183; water carrier with a skin (or pot?) hung on each end of the yoke across his shoulders and another one below the crook of his left arm; the vessel on the right end of his yoke is over a receptacle for the water; a star on either side of the head (denoting supernatural?). The whole object is enclosed by 'parenthesis' marks. The parenthesis is perhaps a way of splitting of the ellipse (Hunter, G.R.,JRAS, 1932, 476). An unmistakable example of an 'hieroglyphic' seal. Hieroglyph: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' (Telugu) Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron' (Santali) Hieroglyph: meḍha ‘polar star’ (Marathi). Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.Mu.) Thus, meḍ kuṭhi 'iron smelter'. (Parenthesis kuṭila is a phonetic determinan of the substantive gloss: kuṭhi 'smelter'. It could also denote a smelter for kuṭila, 'tin metal').

kuṭi కుటి : శంకరనారాయణ తెలుగు-ఇంగ్లీష్ నిఘంటువు 1953 a woman water-carrier.

Splitting the ellipse () results in the parenthesis, ( ) within which the hieroglyph multiplex (in this case of Ur Seal Impression, a water-carrier with stars flanking her head) is infixed, as noted by Hunter.

The ellipse is signified by Meluhha gloss with rebus reading indicating the artisan's competence as a professional: kōnṭa 'corner' (Nk.); kōṇṭu angle, corner (Tu.); rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) Alternative reading; kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze'.

kõdā is a metals turner, a mixer of metals to create alloys in smelters.

The signifiers are the hieroglyph components: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal'; meḍha ‘polar star’ rebus: meḍ ‘iron’; kōnṭa 'corner' rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’; kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal').

The entire hieroglyph multiplex stands deciphered: kõdā, 'metals turner' (with) meḍ ‘iron’ kuṭhi '

smelter', kuṭila, 'tin metal'.

2. This hieroglyph multiplex of the Ur Seal Impression confirms the rebus-metonymy-layered cipher of Meluhha glosses related to metalwork.

3. A characteristic feature of Indus writing system unravels from this example: what is orthographically constructed as a pictorial motif can also be deployed as a 'sign' on texts of inscriptions. This is achieved by a stylized reconstruction of the pictorial motif as a 'sign' which occurs with notable frequency on Indus Script Corpora -- with orthographic variants (Signs 12, 13, 14).

Identifying Meluhha gloss for parenthesis hieroglyph or ( ) split ellipse: குடிலம்¹ kuṭilam, n. < kuṭila. 1. Bend curve, flexure; வளைவு. (திவா.) (Tamil) In this reading, the Sign 12 signifies a specific smelter for tin metal: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/ kuṭila, 'tin (bronze)metal; kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) [cf. āra-kūṭa, ‘brass’ (Samskritam) See: http://download.docslide.us/uploads/check_up03/192015/5468918eb4af9f285a8b4c67.pdf

It will be seen from Sign 15 that the basic framework of a water-carrier hieroglyph (Sign 12) is superscripted with another hieroglyph component, Sign 342: 'Rim of jar' to result in Sign 15. Thus, Sign 15 is composed of two hieroglyph components: Sign 12 'water-carrier' hieroglyph; Sign 342: "rim-of-jar' hieroglyph (which constitutes the inscription on Daimabad Seal 1).

kaṇḍ kanka ‘rim of jar’; Rebus: karṇaka ‘scribe’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’. Thus the ligatured Glyph is decoded: kaṇḍ karṇaka ‘furnace scribe'

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.Each hieroglyph component of Sign 15 is read in rebus-metonymy-layered-meluhha-cipher: Hieroglyph component 1: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal'. Hieroglyph component 2: kanka, kārṇī-ka 'rim-of-jar' rebus: kanka, kārṇī-ka m. ʻsupercargo of a shipʼ 'scribe'.

Ligatured hieroglyph 15 using two ligaturing components: 1. water-carrier; 2. rim-of-jar. The ‘rim-of-jar’ glyph connotes: furnace account (scribe). Together with the glyph showing ‘water-carrier’, the ligatured glyphs of kuṭi ‘water-carrier’ + ‘rim-of-jar’ can thus be read as: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka ‘smelting furnace account (scribe)’.

m1405 Pict-97 Person standing at the centre pointing with his right hand at a bison facing a trough, and with his left hand pointing to the Sign 15.

This tablet is a clear and unambiguous example of the fundamental orthographic style of Indus Script inscriptions that: both signs and pictorial motifs are integral components of the message conveyed by the inscriptions. Attempts at 'deciphering' only what is called a 'sign' in Parpola or Mahadevan corpuses will result in an incomplete decoding of the complete message of the inscribed object.

barad, barat 'ox' Rebus: भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c.(Marathi)

pattar 'trough'; rebus pattar, vartaka 'merchant, goldsmith' (Tamil) பத்தர்² pattar

, n. < T. battuḍu. A caste title of goldsmiths; தட்டார் பட்டப்பெயருள் ஒன்று.

eraka'raised arm' Rebus: eraka'metal infusion' (Kannada. Tulu)

Sign 15: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka ‘smelting furnace account (scribe)’.

Thus, the hieroglyph multiplex on m1405 is read rebus from r.: kuṭhi kaṇḍa kanka eraka bharata pattar'goldsmith-merchant guild -- smelting furnace account (scribe), molten cast metal infusion, alloy of copper, pewter, tin.'

Sign 13 is a composition of hieroglyph component Sign 12 kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' PLUS

Sign' which signifies hieroglyph: 'notch'. Reading the two hieroglyph components together Sign 13 reads: kuṭi 'woman water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter' furnace for iron/kuṭila, 'tin metal'.PLUS khāṇḍā ‘notch’ Marathi: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). Rebus: khāṇḍā ‘metal tools, pots and pans’. Thus, the reading is: kuṭhi khāṇḍā 'smelter metal tools, pots and pans'.

Sign 14 add the hieroglyph component kōla 'arrow' or kaṇḍa ;'arrow-head' to Sign 12. This Sign 14 is deciphered as kuṭhi kaṇḍa'smelter metal tools, pots and pans' (Thus, a synonym of Sign 13) OR kuṭhi kola 'smelter, working in iron' or kuṭhi kole.l 'smelter, smithy'.

Hieroglyph: eraka‘raised arm’ (Telugu) Rebus: eraka‘copper’ (Telugu); 'moltencast' (Gujarati); metal infusion (Kannada.Tulu)

Sign 15 occurs togethe with a notch-in-fixed fish hieroglyph on Harappa 73 seal:

Harappa seal (H-73)[Note: the hieroglyph ‘water carrier’ pictorial of Ur Seal Impression becomes a hieroglyph sign] Hieroglyph: fish + notch: aya 'fish' + khāṇḍā m A jag, notch Rebus: aya 'metal'+ khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kuṭi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A

Harappa seal (H-73)[Note: the hieroglyph ‘water carrier’ pictorial of Ur Seal Impression becomes a hieroglyph sign] Hieroglyph: fish + notch: aya 'fish' + khāṇḍā m A jag, notch Rebus: aya 'metal'+ khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’. kuṭi 'water-carrier' Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. खोंड (p. 216) [khōṇḍa] m A young bull, a bullcalf; खोंडा [ khōṇḍā ] m A Hieroglyph: kōḍ 'horn' Rebus: kōḍ 'place where artisans work, workshop' কুঁদন, কোঁদন [ kun̐dana, kōn̐dana ] n act of turning (a thing) on a lathe; act of carving (Bengali) कातारी or कांतारी (p. 154) [ kātārī or kāntārī ] m (कातणें ) A turner.(Marathi)

Rebus: खोदकाम [ khōdakāma ] n Sculpture; carved work or work for the carver.

खोदगिरी [ khōdagirī ] f Sculpture, carving, engraving: also sculptured or carved work.खोदणें [ khōdaṇēṃ ] v c & i (The intimations of a metals turner as a scribe are also gleaned from the gloss: खोडाखोड or डी [ khōḍākhōḍa or ḍī ] f (

That a metals turner is engaged in metal alloying is evident from the gloss: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge. Hence 2 A lump or solid bit (as of phlegm, gore, curds, inspissated milk); any concretion or clot.

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/03/x.html

,

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/06/hieroglyphmultiplextext-sagad-vakyam.html Thanks to Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale who compared Indus Script 'chimaera' to 'hypertext'. A paper (2012) by Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale on Composite Indus creatures and their meaning: Harappa Chimaeras as 'Symbolic Hypertexts'. Some Thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization at http://a.harappa.com/content/harappan-chimaeras

This note elaborates on this splendid insight argued archaeologically and orthographically in their monograph.

Arguments of Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale

The arguments of Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale are framed taking the example of a Mohenjo-daro seal m0300 with what they call 'symbolic hypertext' or, 'Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components':

m0300. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Harappan chimaera and its hypertextual components. Harappan chimera and its hypertextual components. The 'expression' summarizes the syntax of Harappan chimeras within round brackets, creatures with body parts used in their correct anatomic position (tiger, unicorn, markhor goat, elephant, zebu, and human); within square brackets, creatures with body parts used to symbolize other anatomic elements (cobra snake for tail and human arm for elephant proboscis); the elephant icon as exonent out of the square brackets symbolizes the overall elephantine contour of the chimeras; out of brackes, scorpion indicates the animal automatically perceived joining the lineate horns, the human face, and the arm-like trunk of Harappan chimeras. (After Fig. 6 in: Harappan chimaeras as 'symbolic hypertexts'. Some thoughts on Plato, Chimaera and the Indus Civilization (Dennys Frenez & Massimo Vidale, 2012)

Framework and Functions of Indus Script

The unique characteristic of Indus Script which distinguishes the writing system from Egyptian hieroglyphs are as follows:

1. On both Indus Script and Egyptian hieroglyphs, hieroglyph-multiplexes are created using hieroglyph components (which Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale call hypertextual components).

2. Indus Script denotes 'expressions or speech-words' for every hieroglyph while Egyptian hieroglyphs generally denote 'syllables' (principally consonants without vowels).

3. While Egyptian hieroglyphs are generally deployed to derive 'names of people' or 'expressions denoting administrative divisions' deploying nomes, Indus Script is NOT used for syllabic combinations which result in names of people or designations. As evidenced by the use of Brahmi or Kharoshthi script together with Indus Script hieroglyphs on tens of thousands of ancient coins, the Brahmi or Kharoshthi syllabic representations are generally used for 'names of people or designations' while Indus Script hieroglyphs are used to detail artisan products, metalwork, in particular.

The framework of Indus Script has two structures: 1) pictorial motifs as hieroglyph-multiplexes; and 2) text lines as hieroglyph-multiplexes

Dennys Frenez and Massimo Vidale focus attention on pictorial motifs and on m0300 seal, identify a number of hieroglyph components constituting the hieroglyph-multiplex -- on the pictorial motif of 'composite animal', seen are hieroglyph components (which they call hypertextual components): serpent (tail), scorpion, tiger, one-horned young bull, markhor, elephant, zebu, standing man (human face), man seated in penance (yogi).

The yogi seated in penance and other hieroglyphs are read rebus in archaeometallurgical terms: kamaDha 'penance' (Prakritam) rebus: kampaTTa 'mint'. Hieroglyph: kola 'tiger', xolA 'tail' rebus: kol 'working in iron'; kolle'blacksmith'; kolhe'smelter'; kole.l 'smithy'; kolimi 'smithy, forge'. खोड [ khōṇḍa ] m A young bull, a bullcalf (Marathi) rebus: khond 'turner'. dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhatu 'minerals'. bica 'scorpion' rebus: bica'stone ore'. miṇḍāl markhor (Tor.wali) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati) Rebus: meḍ (Ho.); mẽṛhet ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) mẽṛhet iron; ispat m. = steel; dul m. = cast iron (Munda) kara'elephant's trunk' Rebus: khar'blacksmith'; ibha'elephant' rebus: ib'iron'. Together: karaibā 'maker, builder'.

Use of such glosses in Meluhha speech can be explained by the following examples of vAkyam or speech expressions as hieroglyph signifiers and rebus-metonymy-layered-cipher yielding signified metalwork:

Example 1: mũh opening or hole (in a stove for stoking (Bi.); ingot (Santali) mũh metal ingot (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt ko mūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali) kaula mengro ‘blacksmith’ (Gypsy) mleccha-mukha (Samskritam) = milakkhu‘copper’ (Pali) The Samskritam gloss mleccha-mukha should literally mean: copper-ingot absorbing the Santali gloss, mũh, as a suffix.

Example 2: samṛobica, stones containing gold (Mundari) samanom = an obsolete name for gold (Santali) [bica‘stone ore’ (Munda): meṛed-bica = iron stone ore, in contrast to bali-bica, iron sand ore (Munda)].

In addition to the use of hieroglyph-components to create hieroglyph-multiplexes of pictorial motifs such as 'composite animals', the same principle of multiplexing is used also on the so-called 'signs' of texts of inscriptions.

Smithy with an armourer

http://www.harappa.com/indus/32.html Seal. Mohenjo-daro. Terracotta sealing from Mohenjo-daro depicting a collection of animals and some script symbols. In the centre is a horned crocodile (gharial) surrounded by other animals including a monkey.

In these seals of Mohenjo-daro ‘horned crocodile’ hieroglyph is the center-piece surrounded by hieroglyphs of a pair of bullocks, elephant, rhinoceros, tiger looking back and a monkey-like creature.

Obverse of m1395 and m0441 had the following images of a multi-headed tiger.

Ta. kōṭaram monkey. Ir. kōḍa (small) monkey; kūḍag monkey. Ko. ko·ṛṇ small monkey. To. kwṛṇ monkey. Ka. kōḍaga monkey, ape. Koḍ. ko·ḍë monkey. Tu. koḍañji, koḍañja, koḍaṅgů baboon. (DEDR 2196). kuṭhāru = a monkey (Sanskrit) Rebus: kuṭhāru ‘armourer or weapons maker’(metal-worker), also an inscriber or writer.

Pa. kōḍ (pl. kōḍul) horn; Ka. kōḍu horn, tusk, branch of a tree; kōr horn Tu. kōḍů, kōḍu horn Ko. kṛ (obl. kṭ-)( (DEDR 2200) Paš. kōṇḍā ‘bald’, Kal. rumb. kōṇḍa ‘hornless’.(CDIAL 3508). Kal. rumb. khōṇḍ a ‘half’ (CDIAL 3792).

Rebus: koḍ 'workshop' (Gujarati) Thus, a horned crocodile is read rebus: koḍ khar 'blacksmith workshop'. khar ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri) kāruvu ‘crocodile’ Rebus: ‘artisan, blacksmith’.

Hieroglyph: Joined animals (tigers): sangaḍi = joined animals (M.)

Rebus 1: sãgaṛh m. ʻ line of entrenchments, stone walls for defence ʼ (Lahnda)(CDIAL 12845)

Rebus 2: sang संग् m. a stone (Kashmiri) sanghāḍo (G.) = cutting stone, gilding; sangatarāśū = stone cutter; sangatarāśi = stone-cutting; sangsāru karan.u = to stone (S.), cankatam = to scrape (Ta.), sankaḍa (Tu.), sankaṭam = to scrape (Skt.)

kol 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'. Thus, the multi-headed tiger yields one reading: rebus: kol sangaḍi 'fortified place for metal (& ore stone) workers'.

Rebus 3: saMghAta 'caravan'

Thus, the three tigers together with wings reads: eraka kol saMghAta 'moltencast metal, iron worker caravan'.

सं-घात b [p= 1130,1] a company of fellow-travellers , caravan VP. close union or combination , collection , cluster , heap , mass , multitude TS. MBh. &c (Monier-Williams)

सं-गत [p= 1128,2] mfn. come together , met , encountered , joined , united AV. &cm. (scil. संधि) an alliance or peace based on mutual friendship Ka1m. Hit.n. frequent meeting , intercourse , alliance , association , friendship or intimacy with (instr. gen. , or comp.) Kat2hUp. Mn. MBh. &n. agreement MBh.fitted together , apposite , proper , suitable , according with or fit for (comp.) Ka1v. Katha1s. (Monier-Williams)

Three entwined winged tigers (Sanchi) kola ‘tiger, jackal’ (Konkani.) kul ‘tiger’ (Santali); kōlu id. (Telugu) kōlupuli = Bengal tiger (Te.) कोल्हा [ kōlhā ] कोल्हें [kōlhēṃ] A jackal (Marathi) Rebus: kol, kolhe, ‘the koles, iron smelters speaking a language akin to that of Santals’ (Santali) kol ‘working in iron’ (Tamil)

Phonetic determinant glyph: kola, kōlu ‘jackal, jackal’ (Kon.Telugu) kul ‘the tiger, felis tigris’ (Santali) कोला [ kōlā ] m (Commonly कोल्हा) A jackal. कोल्हें [ kōlhēṃ ] n A jackal. Without reference to sex. Pr. अडलें कोल्हें मंगळ गाय Even the yelling jackal can sing pleasantly when he is in distress. कोल्हें लागलें Applied to a practical joke. केल्हेटेकणें or कोल्हेटेकण [ kēlhēṭēkaṇē or ṅkōlhēṭēkaṇa ] n Gen. in obl. cases with बस or ये, as कोल्हेटेकण्यास बसणें To sit cowering; to sit as a jackal.कोल्हेटेकण्यास येणें To be arrived at or to be approaching the infirmities of age. 2 To be approaching to setting;--used of the sun or the day, when the sun is conceived to be about that distance from the horizon as a jackal, when he rests on his hinder legs, is from the ground. कोल्हेभूंक [ kōlhēbhūṅka ] or -भोंक f (कोल्हा & भुंकणें To bark.) The yelling of jackals. 2 Early dawn; peep of day. कोल्हेहूक [ kōlhēhūka ] f The yelling of jackals. 2 fig. Assailing or setting upon with vehement vociferations. (Marathi) See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2011/10/itihasa-and-eagle-narratives.html

kul tiger; kul dander den of tiger; an.d.kul to become tiger; hudur. to growl as tiger; maran. d.at.kap kul a big-headed tiger (Santali.lex.) kolo, kolea_ jackal (Kon.lex.) ko_lhuya-, kulha- jackal (Pkt.)[cf. kul.l.a-nari jackal (Ta.)(DEDR 1839)]; kolha_, ko_ jackal; adj. crafty (H.); kohlu~, kolu~ jackal (G.); kolha_, kola_ (M.)(CDIAL 3615). karaj a jackal (Santali.lex.) kudke fox (Kor.); kudike jackal (Tu.); kudka id. (Ka.); kor-o naka jackal (small in size, opposed to peri naka)(Kond.a)(DEDR 1851). kulaippu barking, snarling (Ta.)(DEDR 1811). ko_lupuli = big tiger (Te.)

Allograph: kola ‘woman’ (Nahali); kolami ‘forge’ (Te.).kolhe ‘iron smelter’ (Santali) kol, kolhe ‘the koles, an aboriginal tribe of iron smelters akin to that of the Santals’ (Santali) kola bride, son's wife, younger brother's wife (Nk.); koral younger brother's wife; kommal (pl. kommasil) daughter (Nk.); kor.ol bride (Pa.); kor.al son's wife, younger brother's wife; kod.us-, kod.c- to sprout (Ga.); kor.iya ga_r. son's wife, younger brother's wife (Mand..); kur.a, kr.ua, kr.uha wife (Kui); kur.ia, ku_ria daughter-in-law; kur.va younger brother's wife (Kuwi); kor.gi young (of children); qro infant (Malt.); xarruni_ wife (Br.)(DEDR 2149). kur.i_ woman, wife (Phal.); ku_ru young girl; ko_r.i_, kur.hi_ (K.); kur.a_ bridegroom (L.); kur.i_ girl, virgin, bride; woman (L.); girl, daughter (P.); kur.i, kul.i_, kol.a_ boy; kur.i_ girl (WPah.); a~_t.-kur.a_ childless (a~_t.a tight)(B.); ko_ son; ku_i_ daughter (WPah.); ko son; koi daughter; kua_, ko_i_, koa_, ku_i_ (WPah.)(CDIAL 3245). kur.matt relationship by marriage (P.)(CDIAL 3234). kola ‘woman’ (Nahali. Assamese).

Furnace: kola_ burning charcoal (L.P.); ko_ila_ burning charcoal (L.P.N.); id. (Or.H.Mth.), kolla burning charcoal (Pkt.); koilo dead coal (S.); kwelo charcoal (Ku.); kayala_ charcoal (B.); koela_ id. (Bi.); koilo (Marw.); koyalo (G.)(CDIAL 3484). < Proto-Munda. ko(y)ila = kuila black (Santali): all NIA forms may rest on ko_illa.] koela, kuila charcoal; khaura to become charcoal; ker.e to prepare charcoal (Santali.lex.) kolime, mulime, kolume a fire-pit or furnace (Ka.); kolimi (Te.); pit (Te.); kolame a very deep pit (Tu.); kulume kanda_ya a tax on blacksmiths (Ka.); kol, kolla a furnace (Ta.); kolla a blacksmith (Ma.); kol metal (Ta.)(Ka.lex.) kol iron smelters (Santali.lex.) cf. kol working in iron, blacksmith (Ta.)(DEDR 2133). Temple; smithy: kol-l-ulai blacksmith's forge (kollulaik ku_t.attin-a_l : Kumara. Pira. Ni_tiner-i. 14)(Ta.lex.) kollu- to neutralize metallic properties by oxidation (Ta.lex.) kole.l smithy, temple in Kota village (Ko.); kwala.l Kota smithy (To.); kolmi smithy (Go.)(DEDR 2133). kollan--kamma_lai < + karmas'a_la_, kollan--pat.t.arai, kollan-ulai-k-ku_t.am blacksmith's workshop, smithy (Ta.lex.) lohsa_ri_ smithy (Bi.)(CDIAL 11162). cf. ulai smith's forge or furnace (Na_lat.i, 298); ulai-k-kal.am smith's forge; ulai-k-kur-at.u smith's tongs; ulai-t-turutti smith's bellows; ulai-y-a_n.i-k-ko_l smith's poker, beak-iron (Ta.lex.) Self-willed man: lo_hala made of iron (Skt.); lohar, lohariyo self-willed and unyielding man (G.)(CDIAL 11161). cf. goul.i, goul.ia_ herdsman (Kon.lex.) goil cowhouse, hut, pasture ground (P.); gol drove of cattle sent to another village (P.); go_uliya herdsman (Pkt.); goili_ (P.)(CDIAL 4259). kol brass or iron bar nailed across a door or gate; kollu-t-tat.i-y-a_n.i large nail for studding doors or gates to add to their strength (Ta.lex.) Tool-bag: lokhar bag in which a barber keeps his tools (N.); iron tools, pots and pans (H.); lokhar. iron tools (Ku.); lokhan.d. iron tools, pots and pans (H.); lokha~d. tools, iron, ironware (G.); iron (M.)(CDIAL 11171). lod.hu~ pl. carpenter's tools (G.)(CDIAL 11173). karuvi-p-pai instrument-case; barber's bag (Ta.lex.) cf. karuvu-kalam treasury, treasure-house (Ta.lex.) Cobbler's iron pounder: lohaga~ga_, lahau~ga_ cobbler's iron pounder (Bi.); leha~ga_ (Mth.); luha~_gi_ staff set with iron rings (P.); loha~_gi_ (H.M.); lavha~_gi_ (M.); laha~_gi_, loha~gi_ (M.)(CDIAL 11174). Image: frying pan: lohra_, lohri_ small iron pan (Bi.)(CDIAL 11160). lo_hi_ any object made of iron (Skt.); pot (Skt.); iron pot (Pkt.); lo_hika_ large shallow wooden bowl bound with iron (Skt.); lauha_ iron pot (Skt.); loh large baking iron (P.); luhiya_ iron pan (A.); lohiya_ iron or brass shallow pan with handles (Bi.); lohiyu~ frying pan (G.)(CDIAL 11170). lauhabha_n.d.a iron pot, iron mortar (Skt.); lo_habhan.d.a copper or brass ware (Pali); luha~_d.ir.i_ iron pot (S.); luha~_d.a_ (L.); frying pan (P.); lohn.d.a_, lo~_hd.a_ (P.); luhu~r.e iron cooking pot (N.); lohora_ iron pan (A.); loha~r.a_ iron vessel for drawing water for irrigation (Bi.); lohan.d.a_, luhan.d.a_ iron pot (H.); lod.hu~ iron, razor (G.)[cf. xolla_ razor (Kur.); qole id. (Malt.); hola'd razor (Santali)(DEDR 2141)]; lod.hi_ iron pan (G.)(CDIAL 11173).

Rebus: kolimi 'smithy-forge'; kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelters' kole.l 'smithy, temple'; eraka 'wing' Rebus: eraka 'copper'.

The artistic entwining of three tigers is seen on a seal with Indus Script from Mohenjo-daro.

This can be seen as a precursor model for the three tigers/lions shown on a Sanchi torana (gateway). Out of the seven friezes showing a hieroglyph-multiplex of three winged tigers, one frieze adds hieroglyphs 'leafless stalks' as horns of two tigers; two riders are also added to signify the artisans at work:

Thus, tigers with wings joined reads: eraka kol saMghAta 'moltencast metal, iron worker caravan'. With karaṇḍā 'stalks' as koD 'horns' and artisans (carrying goads or weapons or काण्डी kANDI 'little stalk or stem') hieroglyph components added: karaḍā eraka kol saMghAta 'hard alloy moltencast copper working in iron caravan' PLUS kuThAru 'armourer', or kamar 'artisan' PLUS koD 'workshop'. [In Udipi and coastal Dakshina Kannada districts of Karnataka, there is a practice of ‘Pili Kola’ worshiping Tiger. The festival is conducted once in every two years in Muggerkala Temple in Kaup. http://www.bellevision.com/belle/index.php?action=topnews&type=3842

http://www.mangalorean.com/specials/specialnews.php?newsid=481755&newstype=local] Rebus: खांड (p. 202) [ khāṇḍa as in lokhaṇḍa 'metal tools, pots and pans, metalware' (Marathi). Thus the two riders of the hieroglyph-multiplex of stalk-as-horn PLUS winged tigers can be read as: armourers working in a smithy-forge, kolimi and with hard alloy, karaDa; moltencast metal, eraka. The riders seem to be arrying: कुठार (p. 167) [ kuṭhāra ] m S An ax or a hatchet. Hence, they are kuThAru 'armourers'.

mAtri is a knower, one who has true knowledge; hence, mahAmAtra is an elephant trainer. A mahout is a person who rides an elephant. The word mahout comes from the Hindi words mahaut (महौत) and mahavat (महावत), which eventually goes back to Sanskrit mahamatra (महामात्र). Another term for mahout is cornac (as in French, from the Portuguese; kornak in Polish, also a rather current last name). This word comes form Sanskrit term karināyaka, the compound of Sanskrit words karin (elephant) and nayaka (leader). In Tamil, the word used is "pahan", which means elephant keeper, and in Sinhalese kurawanayaka ('stable master'). In Malayalam the word used is paappaan.In Burma, the profession is called oozie; in Thailand kwan-chang; and in Vietnam quản tượng. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mahout

The 'horns' are 'stalks', hieroglyphs: कारंडा [ kāraṇḍā ]करंडा [ karaṇḍā ] m A chump or block. the stock or fixed portion of the staff of the large leaf-covered summerhead or umbrella. A clump, chump, or block of wood. करांडा [ karāṇḍā ] m C A cylindrical piece as sawn or chopped off the trunk or a bough of a tree; a clump, chump, or block. करोळा [ karōḷā ] m The half-burnt grass of a Potter's kiln: also a single stalk of it. Kalanda [cp. Sk. karaṇḍa piece of wood?] heap, stack (like a heap of wood? cp. kalingara) Miln 292 (sīsa˚) (Pali) करण्ड [L=44277] n. a piece of wood , block Bhpr.

Rebus: fire-god: @B27990. #16671. Remo <karandi>E155 {N} ``^fire-^god''.(Munda)

Allograph: करडी [ karaḍī ] f (See करडई) Safflower: also its seed.

Rebus: karaḍa ‘hard alloy’ (Marathi) See: http://tinyurl.com/qcjhwl2

It is notable that the 'stalks' as 'horns' of tigers on Sanchi South stupa architrave pillar are comparable to the three leafless stalks displayed on Sit Shamshi Bronze:

Why three? kolmo 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'; kole.l 'smithy, temple'.

Wooden marker or stone planted for the dead on Sit Shamshi bronze model

kol 'pancaloha, alloy of five metals' (Tamil)

kolom = cutting, graft; to graft, engraft, prune; kolom dare kana = it is a grafted tree; kolom ul = grafted mango; kolom gocena = the cutting has died; kolom kat.hi hor.o = a certain variety of the paddy plant (Santali); kolom (B.); kolom mit = to engraft; kolom porena = the cutting has struck root; kolom kat.hi = a reed pen (Santali.lex.) ku_l.e stump (Ka.) [ku_li = paddy (Pe.)] xo_l = rice-sheaf (Kur.) ko_li = stubble of jo_l.a (Ka.); ko_r.a = sprout (Kui.) ko_le = a stub or stump of corn (Te.)(DEDR 2242). kol.ake, kol.ke, the third crop of rice (Ka.); kolake, kol.ake (Tu.)(DEDR 2154) kolma = a paddy plant; kolma hor.o ‘ a variety of rice plant’ (Santali.lex.) [kural = corn-ear (Ta.)]

Three stalks are adjacent to a stele which could have denoted the stone marker planted for the dead, Pitr-s. It may also denote meḍ ‘stake’ Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’(Munda. Ho.) Note: meḍ may refer to meteorite iron. mŏnḍ 1 म्वंड् m. (in Hindū mythology) the N. of a demon (in Skt., Muṇḍa) who with Caṇḍa was killed by Dēvī, the consort, or Śakti, of Śiva. mŏnḍa-daham म्वंड-दहम् । तिथिविशेषः the 'Muṇḍatenth', the tenth lunar day of the dark half of the month of Wāhĕkh (Skt., Vaiśākha) (April-May), on which the slaughter of Caṇḍa and Muṇḍa is celebrated. <munda> {N} ``wooden ^marker or stone planted for the dead''. @7722. #20071.wana munda, 'the log harrow over which rice is threshed' (sic. L. 464;? wana-mọ̆nḍu). mọ̆nḍu । स्थाणुः m. the trunk or stump of a tree, including the solid part of the root (cf. mŏ̈nḍü 1) (El. múnd) (cf. khŏḍa-mo, p. 392a, l. 5, and nasta-mo, s.v. nast); a log, a heavy block of wood (Gr.Gr. 37, Śiv. 1856); a pillar; -- ˚ any clumsy lump (Rām. 631)(Kashmiri) muṇḍaka -- m. ʻ trunk of lopped tree ʼ lex. [Prob. of Drav. origin (A. Master BSOAS xii 354) with coalescence of two Drav. wordgroups (DED 4199, 4200); less likely Mu. connexions (J. Przyluski BSL xxx 199, PMWS 102). Not with P. Thieme ZDMG 93, 134 < *mr̥ṁṣṭa -- nor with P. Tedesco JAOS 65, 82 < vr̥ddha -- K. mŏnḍ m. ʻ stump of a tree ʼ, f. ʻ thick underground stalk ʼ, mŏnḍuru m. ʻstump of a tree ʼ; S. muno ʻ blunt, less by a quarter ʼ, m. ʻ upright post of water -- or spinning -- wheel ʼ, munī f. ʻ post, stake ʼ; L. munn m. ʻ pillar, post ʼ, munnī f. ʻ post in middle of threshing floor, upright gravestone ʼ; P. munnī f. ʻ girl ʼ, muṇḍā m. ʻ boy ʼ, munnā m. ʻ penis, plough -- handle ʼ; Ku. mũṛo ʻ stump ʼ; Or. muṇḍa ʻ pollard, trunk ʼ, muṇḍā ʻ stump ʼ; Bi. mū̃ṛ, °ṛā, °ṛī ʻ ball at end of beam of sugar -- mill ʼ; Mth. mū̃ṛ ʻ trunk of cut tree ʼ, mū̃ṛā ʻ hornless ox ʼ, muṇḍā ʻ round cap covering the ears (worn by Brahmans) ʼ;Kho. mun ʻ stump of tree ʼ, (Lor.) Sh. (Lor.) mūn, pl. °ní ʻ stump or bole of tree, stump of amputated leg or arm, maize stubble ʼ are either Bi. mũṛer, (Camparan) mũṛerā, (Gaya) mũṛerī ʻ masonry work at head of a well ʼ (semant. cf. SEBi. mūṛhā < *muḍḍha -- 1, and another name for the same: nirārī < nirākāra -- ʻ shapeless ʼ).WPah.kṭg. məṇḍēr, məḍēr f. (obl. -- a) ʻ fence, railing ʼ. (CDIAL 10191, 10192).

kolime, kolume, kulame, kulime, kulume, kulme fire-pit, furnace (Ka.); kolimi furnace (Te.); pit (Te.); kolame a very deep pit (Tu.); kulume kanda_ya a tax on blacksmiths (Ka.); kol, kolla a furnace (Ta.) kole.l smithy, temple in Kota village (Ko.); kwala.l Kota smithy (To.); konimi blacksmith; kola id. (Ka.); kolle blacksmith (Kod.); kollusa_na_ to mend implements; kolsta_na, kulsa_na_ to forge; ko_lsta_na_ to repair (of plough-shares); kolmi smithy (Go.); kolhali to forge (Go.)(DEDR 2133).] kolimi-titti = bellows used for a furnace (Te.lex.) kollu- to neutralize metallic properties by oxidation (Ta.) kol = brass or iron bar nailed across a door or gate; kollu-t-tat.i-y-a_n.i large nail for studding doors or gates to add to their strength (Ta.lex.) kollan--kamma_lai < + karmas'a_la_, kollan--pat.t.arai, kollan-ulai-k-ku_t.am blacksmith's workshop, smithy (Ta.lex.) cf. ulai smith's forge or furnace (Na_lat.i, 298); ulai-k-kal.am smith's forge; ulai-k-kur-at.u smith's tongs; ulai-t-turutti smith's bellows; ulai-y-a_n.i-k-ko_l smith's poker, beak-iron (Ta.lex.) [kollulaive_r-kan.alla_r: nait.ata. na_t.t.up.); mitiyulaikkollan- mur-iot.ir.r.an-n-a: perumpa_)(Ta.lex.) Temple; smithy: kol-l-ulai blacksmith's forge (kollulaik ku_t.attin-a_l : Kumara. Pira. Ni_tiner-i. 14)(Ta.lex.) cf. kolhua_r sugarcane milkl and boiling house (Bi.); kolha_r oil factory (P.)(CDIAL 3537). kulhu ‘a hindu caste, mostly oilmen’ (Santali) kolsa_r = sugarcane mill and boiling house (Bi.)(CDIAL 3538).

d.abe, d.abea ‘large horns, with a sweeping upward curve, applied to buffaloes’ (Santali)

d.ab, d.himba, d.hompo ‘lump (ingot?)’, clot, make a lump or clot, coagulate, fuse, melt together (Santali) d.himba = become lumpy, solidify; a lump (of molasses or iron ore, also of earth); sadaere kolheko tahe_kanre d.himba me~r.he~t reak khan.d.ako bena_oet tahe_kana_ = formerly when the Kolhes were here they made implements from lumps of iron (Santali)

Detail of three winged tigers on Sanchi Stupa as centre-piece on the top architrave and on left and right pillars (in three segments):

Left pillar:

Right pillar:

cāli 'Interlocking bodies' (IL 3872) Rebus: sal 'workshop' (Santali)

Pict-61: Composite motif of three tigers

Text1386 Note how the hieroglyph components of the text are displayed in the space available on the seal after the pictorial motif hieroglyphs have been put together as part of the hypertext. The broken corner of the seal may have included other 'text hieroglyphs called signs'.

Text1386 Note how the hieroglyph components of the text are displayed in the space available on the seal after the pictorial motif hieroglyphs have been put together as part of the hypertext. The broken corner of the seal may have included other 'text hieroglyphs called signs'.Hieroglyph of ‘looking back’ is read rebus as kamar 'artisan': క్రమ్మరు [krammaru] krammaru. [Tel.] v. n. To turn, return, go back. మరలు. క్రమ్మరించు or క్రమ్మరుచు krammarinṭsu. V. a. To turn, send back, recall. To revoke, annul, rescind.క్రమ్మరజేయు. క్రమ్మర krammara. Adv. Again. క్రమ్మరిల్లు or క్రమరబడు Same as క్రమ్మరు. krəm backʼ(Kho.)(CDIAL 3145) Kho. Krəm ʻ back ʼ NTS ii 262 with (?) (CDIAL 3145)[Cf. Ir. *kamaka – or *kamraka -- ʻ back ʼ in Shgh. Čůmč ʻ back ʼ, Sar. Čomǰ EVSh 26] (CDIAL 2776) cf. Sang. kamak ʻ back ʼ, Shgh. Čomǰ (< *kamak G.M.) ʻ back of an animal ʼ, Yghn. Kama ʻ neck ʼ (CDIAL 14356). Kár, kãr ‘neck’ (Kashmiri) Kal. Gřä ʻ neck ʼ; Kho. Goḷ ʻ front of neck, throat ʼ. Gala m. ʻ throat, neck ʼ MBh. (CDIAL 4070) Rebus: karmāra ‘smith, artisan’ (Skt.) kamar ‘smith’ (Santali)

kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

kola 'tiger' Rebus: kol 'working in iron'; kolle 'blacksmith'; kolimi 'smithy, forge'; kole.l 'smithy, temple'

meḍ ‘body’ Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.) Vikalpa: kāḍ 2 काड् a man's length, the stature of a man (as a measure of length); rebus: kāḍ ‘stone’; Ga. (Oll.) kanḍ , (S.) kanḍu (pl. kanḍkil) stone

kaṇḍ kanka ‘rim of jar’; Rebus: karṇaka‘scribe’; kaṇḍ ‘furnace, fire-altar’. Thus the ligatured Glyph is decoded: kaṇḍkarṇaka ‘furnace scribe'

kole.l smithy, temple in Kota village (Ko.)

kōnṭa corner (Nk.); tu. kōṇṭu angle, corner (Tu.); rebus: kõdā ‘to turn in a lathe’ (Bengali) Alternative reading; kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bronze'

sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop'

Thus, the message on the seal reads: meḍ ‘iron’; kāḍ ‘stone’; karṇaka ‘furnace scribe'; kolimi 'smithy, forge' kole.l 'smithy, temple'; sal ‘workshop’ PLUS kõdā sal'turner workshop' (Alternative: kancu sal 'bronze workshop')

The entire hypertexts of pictorial and text hieroglyph components can thus be read using rebus-metonymy-layered-meluhha cipher as: 'iron stone furnace scribe smithy-forge, temple, turner or bronze workshop'.

cāli 'Interlocking bodies' (IL 3872) Rebus: sal 'workshop' (Santali) Did the Bharhut architect who designed the Western Torana (Gateway) with hieroglyph multiplex of 3 tigers (winged) intend to send the message that the precincts are: Hieroglyph: cAli 'interlocking bodies' Rebus: sal 'workshop'?

Hieroglyph: kul 'tiger' (Santali) कोल्हें [ kōlhēṃ ] A jackal (Marathi) kol 'tiger, jackal' (Konkani.) kOlupuli 'tiger' (Telugu) కోలు [ kōlu ] kōlu. [Tel.] adj. Big, great, huge పెద్ద. కోలుపులి or కోల్పులి a royal tiger. Rebus: kolimi 'smithy, temple'; kol 'working in iron'. Thus kol(m) could have connoted a tiger.

*ut-- śāla ʻ leaping up ʼ. (CDIAL 1846) śāˊlā f. ʻ shed, stable, house ʼ AV., śālám adv. ʻ at home ʼ ŚBr., śālikā -- f. ʻ house, shop ʼ lex. Pa. Pk. sālā -- f. ʻ shed, stable, large open -- sided hall, house ʼ, Pk. sāla -- n. ʻ house ʼ; Ash. sal ʻ cattleshed ʼ, Wg. šāl, Kt. šål, Dm. šâl; Paš.weg. sāl, ar. šol ʻ cattleshed on summer pasture ʼ; Kho. šal ʻ cattleshed ʼ, še li ʻ goatpen ʼ; K. hal f. ʻ hall, house ʼ; L. sālh f. ʻ house with thatched roof ʼ; A. xāl, xāli ʻ house, workshop, factory ʼ; B. sāl ʻ shed, workshop ʼ; Or. sāḷa ʻ shed, stable ʼ; Bi. sār f. ʻ cowshed ʼ; H. sāl f. ʻ hall, house, school ʼ, sār f. ʻ cowshed ʼ; M. sāḷ f. ʻ workshop, school ʼ; Si. sal -- a, ha° ʻ hall, market -- hall ʼ.(CDIAL 12414) *kōlhuśālā ʻ pressing house for sugarcane or oilseeds ʼ. [*kōlhu -- , śāˊlā -- ] Bi. kolsār ʻ sugarcane mill and boiling house ʼ.(CDIAL 3538) karmaśālā f. ʻ workshop ʼ MBh. [kárman -- 1 , śāˊlā -- ]Pk. kammasālā -- f.; L. kamhāl f. ʻ hole in the ground for a weaver's feet ʼ; Si. kamhala ʻ workshop ʼ, kammala ʻ smithy ʼ.(CDIAL 2896) 2898 karmāˊra m. ʻ blacksmith ʼ RV. [EWA i 176 < stem *karmar -- ~ karman -- , but perh. with ODBL 668 ← Drav. cf. Tam. karumā ʻ smith, smelter ʼ whence meaning ʻ smith ʼ was transferred also to karmakāra -- ] Pa. kammāra -- m. ʻ worker in metal ʼ; Pk. kammāra -- , °aya -- m. ʻ blacksmith ʼ, A. kamār, B. kāmār; Or. kamāra ʻ blacksmith, caste of non -- Aryans, caste of fishermen ʼ; Mth. kamār ʻ blacksmith ʼ, Si. kam̆burā. Md. kan̆buru ʻ blacksmith ʼ.(CDIAL 2898) *karmāraśālā ʻ smithy ʼ. [karmāˊra -- , śāˊlā -- ] Mth. kamarsārī; -- Bi. kamarsāyar?(CDIAL 2899)

I suggest that the three tigers with interlocked bodies DOES connote cāli 'interlocked bodies' Rebus-metonymy layered cipher yields the plain text message : kola 'tiger'> kolom 'three' PLUS cāli 'interlocked bodies' :kammasālā 'workshop' (Prakritam) < kol(m) PLUS śāˊlā, i.e. smithy workshop.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

July 2, 2015