Indian sprachbund of Sarasvati-Sindhu (Hindu) civilization and the imperative of further Proto-IE language studies

I have suggested that chandas of Vedic Samskritam was the prosodic diction and the corresponding parole (vernacular) was mleccha (meluhha), Proto-Prakritam. It is significant that the word mleccha also has the meaning 'copper'. Equally significant is the self-designation of the people as Bharatam Janam by Viswamitra in Rigveda. The word bharatam janam means 'metalcaster folk'; the word भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. भरताचें भांडें (p. 603) [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metalभरत . भरती (p. 603) [ bharatī ] a Composed of the metal भरत .(Marathi. Molesworth lexicon)

Bharatas is used as a collective noun referring to performers of yajna, worshippers of Agni, in the following Krishna Yajurveda texts:\

yvk.1.3 i O Agni, of the Bharatas, youngest, Bear to us excellent, glorious wealth,

yvk.1.8 d This is your king, O Bharatas; Soma is the king of us Brahmans.

yvk.1.8 h This is your king, O Bharatas; Soma is the king of us Brahmans.

yvk.4.4 g He hath been born as guardian of men, wakeful, Agni, skilful, for fresh prosperity; Ghee faced, with mighty sky reaching (blaze) He shineth gloriously, pure for the Bharatas.

The following are references to bharata in Rigveda; it is clear from the reference to 'sons of bharata' in RV 3.53 that the reference is to a group of people engaged in Soma yajna and metaphoric reference to Soma imbibed from Potr's bowl:

The title Mahabharata of the Great Epic is also of significance, narrating the participation of bharata people in a number of episodes; there are 2260 occurrfences of the word bharata as a noun in the Great Epic.

Source: http://ancientvoice.wikidot.com/mbh:bharatas

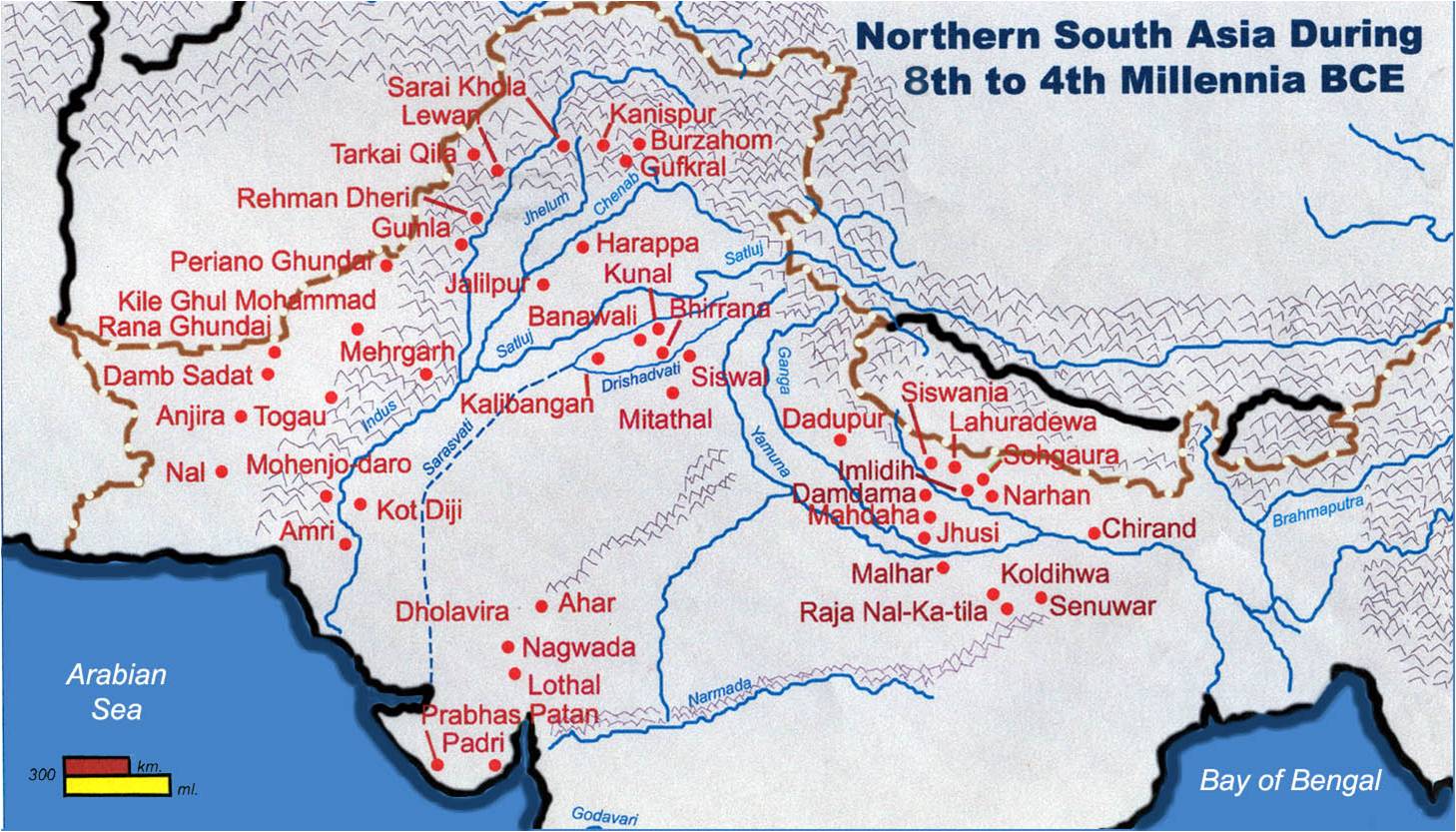

Since the evolution of the Bronze Age was a defining cultural marker of the civilization contact areas, the task begins with the map showing bronze-age sites of eastern India and neighbouring areas in Southeast Asia.

George Pinault's suggested tracing of ams'u 'synonym: soma' of Rigveda in Tocharian ancu, 'iron' also suggests further language and civilization studies in Proto-Indo-European and trade contacts between Sarasvati basin people and Kyrgystan (Mustagh Ata), with particular reference to the processing of soma purchased from merchants from Mt. Mujavant recorded in Rigveda.

Based on archaeometallurgical indicators, it has been hypothesized that a Tin Road between Hanoi, Vietnam and Haifa, Israel was traversed during the Bronze Age. This is consistent with the map drawn by Pinnow for Austro-Asiatic languages which extend from Munda languages of Eastern India to Mon-Khmer of Southeast Asia which is mirrored by the presence of bronze age archaeological sites in a correlated region.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Map of Bronze Age sites of eastern India and neighbouring areas: 1. Koldihwa; 2.Khairdih; 3. Chirand; 4. Mahisadal; 5. Pandu Rajar Dhibi; 6.Mehrgarh; 7. Harappa;8. Mohenjo-daro; 9.Ahar; 10. Kayatha; 11.Navdatoli; 12.Inamgaon; 13. Non PaWai; 14. Nong Nor;15. Ban Na Di andBan Chiang; 16. NonNok Tha; 17. Thanh Den; 18. Shizhaishan; 19. Ban Don Ta Phet [After Fig. 8.1 in: Charles Higham, 1996, The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press].

Decipherment of the Indus script corpora as metalwork catalogues, points to the use of Bronze Age words related to metalwork in almost all the languages of Indian sprachbund. Further research work is needed to trace and identify the phonetic variations recorded in many language lexicons which retain the remembered memories of the Bronze Age work by bharata, 'metalcaster' artisans.

Similar tracing has to be done for the use of the gloss 'meluhha' cognate 'mleccha' in cuneiform texts of Ancient Near East -- as a reference to a language and also to seafaring merchants from Meluhha region which has been mapped by identifying archaeological sites documenting trade exchanges between Meluhha and Ancient Near East and revisiting the Mitanni treaties which seem to include Proto-Indo-Aryan words in Hurrian/Hittite/Gutian; and reference to 'indara' in Gudea inscription, see: http://www.academia.edu/10344521/An_Indo-European_god_in_a_Gudea_Inscription An Indo-European god in a Gudea Inscription.

.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Indian sprachbund

[After Franklin C. Southworth, 2005 Linguistic archaeology of South Asia, London: Routledge-Curzon (for the Table of Contents and chapter summaries, download LASAcontents.pdf). MLECCHA and VEDIC are added as overlays, on the language categories maped by Southworth.]

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/maritime-meluhha-tin-road-links-far.html

Pinnow map

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Austroasiatic Languages:

Munda (Eastern India) and

Mon-Khmer (NE India, mainland SE Asia, Malaysia, Nicobars) [Site maintained by Patricia Donegan and David Stampe]

Lexicography: Etymology: http://www.ling.hawaii.edu/austroasiatic/

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

https://kampotmuseum.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/austroasiatic-languages.jpg

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![{{{mapalt}}}]()

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Austroasiatic-en.svg/300px-Austroasiatic-en.svg.png

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

[Source: Vikrant Kumar, et. al., “Asian and Non-Asian Origins of Mon-Khmer- and Mundari-Speaking Austro-Asiatic Populations of India,” American Journal of Human Biology 18 (2006): 467.]

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

Paul Sidwell and Roger Blench propose that the Austroasiatic phylum had dispersed via the Mekong River drainage basin.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![Indo-Aryan]()

http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~haroldfs/dravling/hopper5.html

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![]()

I have suggested that chandas of Vedic Samskritam was the prosodic diction and the corresponding parole (vernacular) was mleccha (meluhha), Proto-Prakritam. It is significant that the word mleccha also has the meaning 'copper'. Equally significant is the self-designation of the people as Bharatam Janam by Viswamitra in Rigveda. The word bharatam janam means 'metalcaster folk'; the word भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. भरताचें भांडें (p. 603) [ bharatācē mbhāṇḍēṃ ] n A vessel made of the metal

Bharatas is used as a collective noun referring to performers of yajna, worshippers of Agni, in the following Krishna Yajurveda texts:\

yvk.1.3 i O Agni, of the Bharatas, youngest, Bear to us excellent, glorious wealth,

yvk.1.8 d This is your king, O Bharatas; Soma is the king of us Brahmans.

yvk.1.8 h This is your king, O Bharatas; Soma is the king of us Brahmans.

yvk.4.4 g He hath been born as guardian of men, wakeful, Agni, skilful, for fresh prosperity; Ghee faced, with mighty sky reaching (blaze) He shineth gloriously, pure for the Bharatas.

The following are references to bharata in Rigveda; it is clear from the reference to 'sons of bharata' in RV 3.53 that the reference is to a group of people engaged in Soma yajna and metaphoric reference to Soma imbibed from Potr's bowl:

| rvs.2.7 | 1. VASU, thou most youthful God, Bharata, Agni, bring us wealth, |

| rvs.2.7 | 5 Ours art thou, Agni, Bharata, honoured by us with barren cows, |

| rvs.2.36 | Sitting on sacred grass, ye Sons of Bharata, drink Soma from the Potars' bowl, O Men of heaven. |

| rvs.3.53 | 24 These men, the sons of Bharata, O Indra, regard not severance or close connexion. |

| rvs.4.25 | 4 To him shall Agni Bharata give shelter: long shall he look upon the Sun uprising-, |

| rvs.5.54 | Ye give the Bharata as his strength, a charger, and ye bestow a king who quickly listens. |

| rvs.6.16 | 4 Thee, too, hath Bharata of old, with mighty men, implored for bliss. |

| rvs.6.16 | 19 Agni, the Bharata, hath been sought, the Vrtraslayer-, marked of all, |

The title Mahabharata of the Great Epic is also of significance, narrating the participation of bharata people in a number of episodes; there are 2260 occurrfences of the word bharata as a noun in the Great Epic.

| Mbh.1.94.5188 | There the Bharatas lived for a full thousand years, within their fort. |

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.![EpicIndia.jpg]()

Clik here to view.

A map of Bharatavarsha based on Mahabharata references [After Jijith Nadumuri ,2010 http://ancientvoice.wikidot.com/bharatavarsha]

Since the evolution of the Bronze Age was a defining cultural marker of the civilization contact areas, the task begins with the map showing bronze-age sites of eastern India and neighbouring areas in Southeast Asia.

George Pinault's suggested tracing of ams'u 'synonym: soma' of Rigveda in Tocharian ancu, 'iron' also suggests further language and civilization studies in Proto-Indo-European and trade contacts between Sarasvati basin people and Kyrgystan (Mustagh Ata), with particular reference to the processing of soma purchased from merchants from Mt. Mujavant recorded in Rigveda.

Based on archaeometallurgical indicators, it has been hypothesized that a Tin Road between Hanoi, Vietnam and Haifa, Israel was traversed during the Bronze Age. This is consistent with the map drawn by Pinnow for Austro-Asiatic languages which extend from Munda languages of Eastern India to Mon-Khmer of Southeast Asia which is mirrored by the presence of bronze age archaeological sites in a correlated region.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Map of Bronze Age sites of eastern India and neighbouring areas: 1. Koldihwa; 2.Khairdih; 3. Chirand; 4. Mahisadal; 5. Pandu Rajar Dhibi; 6.Mehrgarh; 7. Harappa;8. Mohenjo-daro; 9.Ahar; 10. Kayatha; 11.Navdatoli; 12.Inamgaon; 13. Non PaWai; 14. Nong Nor;15. Ban Na Di andBan Chiang; 16. NonNok Tha; 17. Thanh Den; 18. Shizhaishan; 19. Ban Don Ta Phet [After Fig. 8.1 in: Charles Higham, 1996, The Bronze Age of Southeast Asia, Cambridge University Press].

Decipherment of the Indus script corpora as metalwork catalogues, points to the use of Bronze Age words related to metalwork in almost all the languages of Indian sprachbund. Further research work is needed to trace and identify the phonetic variations recorded in many language lexicons which retain the remembered memories of the Bronze Age work by bharata, 'metalcaster' artisans.

Similar tracing has to be done for the use of the gloss 'meluhha' cognate 'mleccha' in cuneiform texts of Ancient Near East -- as a reference to a language and also to seafaring merchants from Meluhha region which has been mapped by identifying archaeological sites documenting trade exchanges between Meluhha and Ancient Near East and revisiting the Mitanni treaties which seem to include Proto-Indo-Aryan words in Hurrian/Hittite/Gutian; and reference to 'indara' in Gudea inscription, see: http://www.academia.edu/

.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Indian sprachbund

[After Franklin C. Southworth, 2005 Linguistic archaeology of South Asia, London: Routledge-Curzon (for the Table of Contents and chapter summaries, download LASAcontents.pdf). MLECCHA and VEDIC are added as overlays, on the language categories maped by Southworth.]

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/02/maritime-meluhha-tin-road-links-far.html

Pinnow map

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Austroasiatic Languages:

Munda (Eastern India) and

Mon-Khmer (NE India, mainland SE Asia, Malaysia, Nicobars) [Site maintained by Patricia Donegan and David Stampe]

- Munda Lexical Archive, an ongoing copylefted archive of most of the lexical materials available from the non-Kherwarian Munda languages, assembled, analyzed, and arranged by Patricia J. Donegan & David Stampe. A detailed description with credits is forthcoming. For now see 00README. (A current snapshot of the whole is available for download as a zip archive: munda-archive.zip)

- Sora (Saora, Savara), data of G. V. Ramamurti, Verrier Elwin, H. S. Biligiri, David Stampe, Stanley Starosta, Bijoy P. Mahapatra, Ranganayaki Mahapatra, Arlene R. K. Zide, Khageswar Mahapatra, Piers Vitebsky, Patricia J. Donegan, et al.

- Gorum (Parengi), data of Arlene R. K. Zide et al.

- Gutob (Gadaba), data of Norman H. Zide, Bimal Prasad Das, Patricia J. Donegan, et al.

- Remo (Bonda), data of Verrier Elwin, Frank Fernandez, S. Bhattacharya, Patricia J. Donegan, et al.

- Gta' (Didayi), data of Suhas Chatterji, P. N. Chakravarti, Norman H. Zide, Khageswar Mahapatra, Patricia J. Donegan, et al.

- Kharia, data of H. Floor, H. Geysens, H. S. Biligiri, Heinz-Jürgen Pinnow, et al.

- Juang, data of Verrier Elwin, Dan M. Matson, Bijoy P. Mahapatra, Heinz-Jürgen Pinnow, et al.

- Korku, data of Norman H. Zide, Beryl A. Girard, Patricia J. Donegan, et al.

- Santali, a growing selection of Paul Otto Bodding's 5-volume A Santal Dictionary (Oslo, Norske Videnskaps-Akademi, 1929-1936), input by Makoto Minegishi and associates, ILCAA, Tokyo, but so far of limited value since it is accessible only by searching for an exactly spelled Santali headword! .

- Munda:

- Comparative Munda (mostly North), rough draft ed. Stampe, based on Heinz-Jürgen Pinnow's Versuch einer historischen Lautlehre der Kharia-Sprache(Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 1959) and Ram Dayal Munda's Proto-Kherwarian Phonology, unpublished MA thesis, University of Chicago, 1968.

- Working files of South Munda lexical data by gloss assembled from collections of David Stampe, Patricia Donegan, H.-J. Pinnow, Sudhibhushan Bhattacharya, and Norman and Arlene Zide for a seminar by Stampe on Austroasiatic languages.

- Indian Substratum: South Asia Residual Vocabulary Assemblage (SARVA), a compilation of ancient Indian words lacking apparent Indo-Aryan, Dravidian, or Austroasiatic origins, in progress by Franklin Southworth and Michael Witzel, with David Stampe.

- Dravidian: Thomas Burrow and Murray B. Emeneau's A Dravidian Etymological Dictionary, Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2nd ed. 1984. Accessible by search on headwords or strings, through the Digital Dictionaries of South Asia project, U. Chicago.

- Indo-Aryan: Sir Ralph Turner's A Comparative Dictionary of Indo-Aryan Languages, London: Oxford University Press, 1962-66, with 3 supplements 1969-85. Accessible by search on headwords or strings, through the Digital Dictionaries of South Asia project, U. Chicago.

- Sino-Tibetan: James A. Matisoff's STEDT (Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus) Project, at Berkeley. The first fruit of the project, Matisoff'sHandbook of Proto-Tibeto-Burman: System and Philosophy of Sino-Tibetan Reconstruction (University of California Publications in Linguistics 135), 2003, can be downloaded from California's eScholarship Repository as a searchable pdf file. On the STEDT site is an index of reconstructions and a first set ofaddenda and corrigenda for HPTB. Electronic publication of STEDT is planned in 8 semantically arranged fascicles.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

https://kampotmuseum.files.wordpress.com/2013/06/austroasiatic-languages.jpg

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/8/8e/Austroasiatic-en.svg/300px-Austroasiatic-en.svg.png

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

[Source: Vikrant Kumar, et. al., “Asian and Non-Asian Origins of Mon-Khmer- and Mundari-Speaking Austro-Asiatic Populations of India,” American Journal of Human Biology 18 (2006): 467.]

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Paul Sidwell and Roger Blench propose that the Austroasiatic phylum had dispersed via the Mekong River drainage basin.

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

http://ccat.sas.upenn.edu/~haroldfs/dravling/hopper5.html

Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Linguistic history of the Indian subcontinent

The languages of the Indian Subcontinent are divided into various language families, of which the Indo-Aryan languages and the Dravidian languages are the most widely spoken. There are also many languages belonging to unrelated language families such asTibeto-Burman, spoken by smaller groups. Linguistic records begin with the appearance of the Brāhmī script from about the 3rd century BCE.

Indo-Aryan languages

Main article: Indo-Aryan languages

Old Indo-Aryan

Vedic Sanskrit

Main article: Vedic Sanskrit

See also: Indo-Aryan superstrate in Mitanni

Vedic Sanskrit is the language of the Vedas, a large collection ofhymns, incantations, and religio-philosophical discussions which form the earliest religious texts in India and the basis for much of the Hindu religion. Modern linguists consider the metrical hymns of the Rigveda to be the earliest. The hymns preserved in theRigveda were preserved by oral tradition alone over several centuries before the introduction of writing, the oldest among them predating the introduction of Brahmi by as much as a millennium .[citation needed]

The end of the Vedic period is marked by the composition of the Upanishads, which form the concluding part of the Vedic corpus in the traditional compilations... It is around this time that Sanskrit began the transition from a first language to a second language of religion and learning, marking the beginning of the Classical period.

Classical Sanskrit

Main article: Sanskrit

Further information: Pāṇini

The oldest surviving Sanskrit grammar is Pāṇini's Aṣtādhyāyī ("Eight-Chapter Grammar") dating to c. the 5th century BCE. It is essentially a prescriptive grammar, i.e., an authority that defines (rather than describes) correct Sanskrit, although it contains descriptive parts, mostly to account for Vedic forms that had already passed out of use in Pāṇini's time.

When the term arose in India, Sanskrit was not thought of as a specific language set apart from other languages (the people of the time regarded languages more as dialects), but rather as a particularly refined or perfected manner of speaking. Knowledge of Sanskritwas a marker of social class and educational attainment and was taught mainly to Brahmins through close analysis of Sanskritgrammarians such as Pāṇini.

Vedic Sanskrit and Classical or "Paninian" Sanskrit, while broadly similar, are separate varieties, which differ in a number of points ofphonology, vocabulary, and grammar.

Middle Indo-Aryan

Prakrits

Main article: Prakrit

Prakrit (Sanskrit prākṛta प्राकृत (from prakṛti प्रकृति), "original, natural, artless, normal, ordinary, usual", i.e. "vernacular", in contrast tosamskrta "excellently made",[citation needed] both adjectives elliptically referring to vak "speech") refers to the broad family of Indiclanguages and dialects spoken in ancient India. Some modern scholars include all Middle Indo-Aryan languages under the rubric of "Prakrits", while others emphasise the independent development of these languages, often separated from the history of Sanskrit by wide divisions of caste, religion, and geography.

The Prakrits became literary languages, generally patronized by kings identified with the ksatriya caste. The earliest inscriptions in Prakrit are those of Asoka, emperor of Southern India, and while the various Prakrit languages are associated with different patron dynasties, with different religions and different literary traditions.

In Sanskrit drama, kings speak in Prakrit when addressing women or servants, in contrast to the Sanskrit used in reciting more formal poetic monologues.

The three Dramatic Prakrits – Sauraseni, Magadhi, Maharashtri, as well as Jain Prakrit each represent a distinct tradition of literaturewithin the history of India. Other Prakrits are reported in historical sources, but have no extant corpus (e.g., Paisaci).

Pali

Main article: Pāli language

Pali is the Middle Indo-Aryan language in which the Theravada Buddhist scriptures and commentaries are preserved. Pali is believed by the Theravada tradition to be the same language as Magadhi, but modern scholars believe this to be unlikely.[citation needed] Pali shows signs of development from several underlying prakrits as well as some Sanskritisation.

The prakrit of the North-western area of India known as Gāndhāra has come to be called Gāndhārī. A few documents written in theKharoṣṭhi script survive including a version of the Dhammapada.

Apabhraṃśa/Apasabda

Main articles: Middle Indo-Aryan and apabhraṃśa

The Prakrits (which includes Pali) were gradually transformed into अपभ्रंश apabhraṃśas which were used until about the 13th century CE. The term apabhraṃśa refers to the dialects of Northern India before the rise of modern Northern Indian languages, and implies a corrupt or non-standard language. A significant amount of apabhraṃśa literature has been found in Jain libraries. While Amir Khusro andKabir were writing in a language quite similar to modern Hindi-Urdu, many poets, specially in regions that were still ruled by Hindu kings, continued to write in Apabhraṃśa. Apabhraṃśa authors include Sarahapad of Kamarupa, Devasena of Dhar (9th century CE),Pushpadanta of Manikhet (9th century CE), Dhanapal, Muni Ramsimha, Hemachandra of Patan, Raighu of Gwalior (15th century CE). An early example of the use of Apabhraṃśa is in Vikramūrvashīiya of Kalidasa, when Pururava asks the animals in the forest about his beloved who had disappeared.

...

Dravidian languages

Main article: Dravidian languages

Further information: Proto-Dravidian and Elamo-Dravidian languages

The Dravidian family of languages includes approximately 73 languages[3] that are mainly spoken insouthern India and northeastern Sri Lanka, as well as certain areas in Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, and eastern and central India, as well as in parts ofAfghanistan and Iran, and overseas in other countries such as the United Kingdom, United States, Canada,Malaysia and Singapore.

The origins of the Dravidian languages, as well as their subsequent development and the period of their differentiation, are unclear, and the situation is not helped by the lack of comparative linguistic research into the Dravidian languages. Inconclusive attempts have also been made to link the family with the Japonic languages[citation needed] and with the extinct Elamite language (by Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis).

Many linguists, however, tend to favour the theory that speakers of Dravidian languages spread southwards and eastwards through the Indian subcontinent, based on the fact that the southern Dravidian languages show some signs of contact with linguistic groups which the northern Dravidian languages do not. Proto-Dravidian is thought to have differentiated into Proto-North Dravidian, Proto-Central Dravidian and Proto-South Dravidian around 1500 BCE, although some linguists have argued that the degree of differentiation between the sub-families points to an earlier split.

It was not until 1856 that Robert Caldwell published his Comparative grammar of the Dravidian or South-Indian family of languages, which considerably expanded the Dravidian umbrella and established it as one of the major language groups of the world. Caldwell coined the term "Dravidian" from the Sanskrit drāvida, related to the word ‘Tamil’ or ‘Tamilan’, which is seen in such forms as into ‘Dramila’, ‘Drami˜a’, ‘Dramida’ and ‘Dravida’ which was used in a 7th-century text to refer to the languages of the southern India. The publication of the Dravidian Etymological Dictionary by T. Burrow and M. B. Emeneau was a landmark event in Dravidian linguistics.

,,,

Languages of other families in India

Tibeto-Burman languages

Main article: Tibeto-Burman languages

Austroasiatic languages

Main article: Austroasiatic languages

The Austroasiatic family of languages includes the Santal and Munda languages of eastern India, Nepal, and Bangladesh, along with the Mon–Khmer languages spoken by the Khasi and Nicobarese in India and in Burma, Thailand, Laos, Cambodia, Vietnam, and southern China. The Austroasiatic languages are thought to have been spoken throughout the Indian subcontinent by hunter-gatherers who were later assimilated first by the agriculturalist Dravidian settlers and later by the Indo-Aryan peoples arriving from northwestern India.

The Austroasiatic family is thought to be the first to be spoken in ancient India. Some believe the family to be a part of an Austricsuperstock of languages, along with the Austronesian language family.

Great Andamanese & Ongan languages

On the Andaman Islands, language from at least two families are spoken: the Great Andamanese languages and the Ongan languages. The Sentinelese language is spoken on North Sentinel Island but contact has not been made with the Sentinelis, so its language affiliation is unknown. While Joseph Greenberg considered the Great Andamanese languages to be part of a larger Indo-Pacific family, not established through the comparative method and considered spurious by historical linguists, Stephen Wurm suggests similarities with Trans-New Guinea languages and others are due to a linguistic substrate.[67] Juliette Blevins has suggested that the Ongan languages are the sister branch to the Austronesian languages in an Austronesian-Ongan family based on sound correspondences between protolanguages.[68]

Isolates

The Nihali language is a language isolate spoken in Madhya Pradesh and Maharashtra. Affiliations have been suggested to the Munda languages but they have yet to be demonstrated.

Evolution of scripts

Indus script

Main article: Indus script

The Indus script is the short strings of symbols associated with theHarappan civilization of ancient India (most of the Indus sites are distributed in present-day Pakistan and northwest India) used between 2600–1900 BCE, which evolved from an early Indus script attested from around 3500–3300 BCE. Found in at least a dozen types of context, the symbols are most commonly associated with flat, rectangular stone tablets called seals. The first publication of a Harappan seal was a drawing byAlexander Cunningham in 1875. Since then, well over 4000 symbol-bearing objects have been discovered, some as far afield as Mesopotamia. After 1500 BCE, coinciding with the final stage of Harappan civilization, use of the symbols ends. There are over 400 distinct signs, but many are thought to be slight modifications or combinations of perhaps 200 'basic' signs. The symbols remain undeciphered (in spite of numerous attempts that did not find favour with the academic community), and some scholars classify them as proto-writing rather than writing proper.

Substratum in Vedic Sanskrit

Vedic Sanskrit has a number of linguistic features which are alien to most other Indo-European languages. Prominent examples include: phonologically, the introduction of retroflexes, which alternate with dentals; morphologically, the formation of gerunds; andsyntactically, the use of a quotative marker ("iti").Such features, as well as the presence of non-Indo-European vocabulary, are attributed to a local substratum of languages encountered by Indo-Aryan peoples in Central Asia and within the Indian subcontinent.

A substantial body of loanwords has been identified in the earliest Indian texts. Non-Indo-Aryan elements (such as -s- following -u- in Rigvedic busa) are clearly in evidence. While some loanwords are from Dravidian, and other forms are traceable to Munda or Proto-Burushaski, the bulk have no sensible basis in any of these families, suggesting a source in one or more lost languages. The discovery that some loan words from one of these lost sources had also been preserved in the earliest Iranian texts, and also in Tocharian, convinced Michael Witzel and Alexander Lubotsky that the source lay in Central Asia and could be associated with the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC). Another lost language is that of the Indus Valley Civilization, which Witzel initially labelled Para-Munda, but later the Kubhā-Vipāś substrate.

...

Vocabulary[edit]

In 1955 Burrow listed some 500 words in Sanskrit that he considered to be loans from non-Indo-European languages. He noted that in the earliest form of the language such words are comparatively few, but they progressively become more numerous. Though mentioning the likelihood that one source was lost Indian languages extinguished by the advance of Indo-Aryan, he concentrated on finding loans from Dravidian.[12] Kuiper identified 383 specifically Ṛigvedic words as non-Indo-Aryan — roughly 4% of its vocabulary.[13]Oberlies prefers to consider 344-358 "secure" non-Indo European words in the Rigveda.[14] Even if all local non-Indo-Aryan names of persons and places are subtracted from Kuiper's list, that still leaves some 211-250 "foreign" words, around 2% of the total vocabulary of the Rigveda.[15]

These loanwords cover local flora and fauna, agriculture and artisanship, terms of toilette, clothing and household. Dancing and music are particularly prominent, and there are some items of religion and beliefs.[16] They only reflect village life, and not the intricate civilization of the Indus cities, befitting a post-Harappan time frame.[17] In particular Indo-Aryan words for plants stem in large part from other language families, especially from the now lost substrate languages.[18]

Mayrhofer identified a "prefixing" language as the source of many non-Indo-European words in the Rigveda, based on recurring prefixes like ka- or ki-, that have been compared by Michael Witzel to the Munda prefix k- for designation of persons, and the plural prefix ki seen in Khasi, though he notes that in Vedic, k- also applies to items merely connected with humans and animals.[19] Examples include:

- kākambīra a certain tree

- kakardu "wooden stick"

- kapardin "with a hair-knot"

- karpāsa "cotton"

- kavandha "barrel"

- kavaṣa "straddle-legged"

- kilāsa "spotted, leprous"

- kimīda "a demon", śimidā "a demoness"

- kīnāśa "ploughman"

- kiyāmbu a water plant

- kulāya "nest"

- kuliśa "axe"

- kumāra "boy"

- kuluṅga "antelope"

- Kuruṅga name of a chieftain of the Turvaśa.

Witzel remarks that these words span all of local village life. He considers that they were drawn from the lost language of the northern Indus Civilization and its Neolithic predecessors. As they abound in Austroasiatic-like prefixes, he initially chose to call it Para-Munda, but later the Kubhā-Vipāś substrate.[20]

The Indo-Europeanist and Indologist Thieme has questioned Dravidian etymologies proposed for Vedic words, most of which he gives Indo-Aryan or Sanskrit etymologies, and condemned what he characterizes as a misplaced "zeal for hunting up Dravidian loans in Sanskrit". Das even contended that there is "not a single case" in which a communis opinio has been found confirming the foreign origin of a Rigvedic word".[21] Kuiper answered that charge.[22] Burrow in turn has criticized the "resort to tortuous reconstructions in order to find, by hook or by crook, Indo-European explanations for Sanskrit words". Kuiper reasons that given the abundance of Indo-European comparative material — and the scarcity of Dravidian or Munda — the inability to clearly confirm whether the etymology of a Vedic word is Indo-European implies that it is not.[23]

Lost donor languages[edit]

Colin Masica could not find etymologies from Indo-European or Dravidian or Munda or as loans from Persian for 31 percent of agricultural and flora terms of Hindi. He proposed an origin in unknown Language "X".[24] Southworth also notes that the flora terms did not come from either Dravidian or Munda. Southworth found only five terms which are shared with Munda, leading to his suggestion that "the presence of other ethnic groups, speaking other languages, must be assumed for the period in question".[25]

Language of the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC)[edit]

Terms borrowed from an otherwise unknown language include those relating to cereal-growing and bread-making (bread, ploughshare, seed, sheaf, yeast), water-works (canal, well), architecture (brick, house, pillar, wooden peg), tools or weapons (axe, club), textiles and garments (cloak, cloth, coarse garment, hem, needle) and plants (hemp, mustard, Soma plant).[26] Lubotsky pointed out that the phonological and morphological similarity of 55 loanwords in Iranian and in Sanskrit indicate that both share a common substratum, or perhaps two dialects of the same substratum. He concludes that the BMAC language of the population of the towns of Central Asia (where Indo-Iranians must have arrived in the 2nd millennium b.c.) and the language spoken in Punjab (see Harappan below) were intimately related.[27] However, the prevailing interpretation is that Harappan is not related, and the 55 loanwords entered Proto-Indo-Iranian during its development in the Sintashta culture in distant contact with the Bactria–Margiana Archaeological Complex, and then many more words with the same origin enriched Old Indic as it developed among pastoralists who integrated with and perhaps ruled over the declining BMAC.[28] Examples:

- BMAC *anću ‘soma plant (ephedra)’ → Skt. aṃśú-; Av. ąsu-

- BMAC *atʰr̥ → Skt. átharvan ‘priest’, Av. āϑrauuan-/aϑaurun- ‘id.’, Pehlevi āsrōn; Toch. A atär, B etre ‘hero’

- BMAC *bʰiš- ‘to heal’ → Skt. bhiṣáj- m. ‘physician’; LAv. bišaziia- ‘to cure’

- BMAC *dr̥ća → Skt. dūrśa- ‘coarse garment’; Wakhi δirs ‘goat or yak wool’, Shughni δox̆c ‘body hair; coarse cloth’

- BMAC *gandʰ/t- → Skt. gandhá-; LAv. gaiṇti- ‘odor’

- BMAC *gandʰ(a)rw- ‘mythical beast’ → Skt. gandharvá-; LAv. gaṇdərəβa-

- BMAC *indra theonym → Skt. Índra; LAv. Iṇdra daeva's name

- BMAC *išt(i) ‘brick’ → Skt. íṣṭakā- f. (VS+); LAv. ištiia- n., OP išti- f., Pers. xešt; Toch. B iścem ‘clay’

- BMAC *ǰaǰʰa/uka ‘hedgehog’ → Skt. jáhakā; LAv. dužuka-, Bal. ǰaǰuk, Pers. žūža

- BMAC *jawījā ‘canal, irrigation channel’ → Skt. yavīyā-; OP yauwiyā-, Pers. ju(y)

- BMAC *k/ćan- ‘hemp’ → Skt. śaṇa; MP šan, Khot. kaṃha, Oss. gæn(æ)

- BMAC *majūkʰa ‘wooden peg’ → Skt. mayūkha-; OP mayūxa- ‘doorknob’, Pers. mix ‘peg, nail’

- BMAC *nagna → Skt. nagnáhu- (AVP+) m. ‘yeast’; Sogd. nɣny, Pashto naɣan, Pers. nān ‘bread’

- BMAC *sćāga ~ sćaga ‘billy-goat’ → Skt. chāga-; Oss. sæǧ(æ), Wakhi čəɣ ‘kid’

- BMAC *sikatā ‘sand, gravel’ → Skt. sikatā-; OP ϑikā `sand', Khot. siyatā, Buddh. Sogd. šykth

- BMAC *sinšap- ‘mustard’ → Skt. saṣarpa; Khot. śśaśvāna, Parth. šyfš-d'n, Sodg. šywšp-δn, Pers. sipan-dān ‘mustard seed’

- BMAC *(s)pʰāra ‘ploughshare’ → Skt. phāla-; Pers. supār

- BMAC *sūčī ‘needle’ → Skt. sūćī; LAv. sūkā-, MP sozan, Oss. sūʒīn ~ soʒīnæ

- BMAC *šwaipa ‘tail’ → Skt. śépa-, Prākrit cheppā-; LAv. xšuuaēpā-

- BMAC *(H)uštra ‘camel’ → Skt. úṣṭra-; Av. uštra-, Pers. šotor

Harappan[edit]

Witzel initially used the term "Para-Munda" to denote a hypothetical language related but not ancestral to modern Munda languages, which he identified as "Harappan", the language of the Indus Valley Civilization.[29] To avoid confusion with Munda, he later opted for the term "Kubhā-Vipāś substrate".[30] He argues that the Rigveda shows signs of this hypothetical Harappan influence in the earliest level and Dravidian only in later levels, suggesting that speakers of Harappan were the original inhabitants of Punjab and that the Indo-Aryans encountered speakers of Dravidian not before middle Rigvedic times.[31] Krishnamurti deems the evidence too meagre for this proposal. Regarding Witzel's methodology in claiming Para-Munda origins, Krishnamurti states: "The main flaw in Witzel's argument is his inability to show a large number of complete, unanalyzed words from Munda borrowed into the first phase of the Ṛgveda.[32] This statement, however, confuses Proto-Munda and Para-Munda and neglects the several hundred "complete, unanalyzed words" from a prefixing language, adduced by Kuiper [33] and Witzel.[34]

Living donor languages[edit]

A concern raised in the identification of the substrate is that there is a large time gap between the comparative materials, which can be seen as a serious methodological drawback. One issue is the early geographical distribution of the South Asian languages. It should not be assumed that the present-day northern location of Brahui, Kurukh, and Malto reflects the position of their ancestor languages at the time of Indo-Aryan development. Another problem is that modern literary languages may present a misleading picture of their prehistoric ancestors.[35] The first completely intelligible, datable, and sufficiently long and complete epigraphs that might be of some use in linguistic comparison are the Tamil inscriptions of the Pallava dynasty of about 550 C.E. and the early Tamil Brahmi inscriptions starting in the second century BCE.[36] Similarly there is much less material available for comparative Munda and the interval in their case is at least three millennia. However reconstructions of Proto-Dravidian[37] and Proto-Munda[38] now help in distinguishing the traits of these languages from those of Indo-European in the evaluation of substrate and loan words.

Dravidian[edit]

There are an estimated thirty to forty Dravidian loanwords in Vedic.[39] Those for which Dravidian etymologies are certain include kulāya "nest", kulpha "ankle", daṇḍa "stick", kūla "slope", bila "hollow", khala "threshing floor".[40] However Witzel finds Dravidian loans only from the middle Rigvedic period, suggesting that linguistic contact between Indo-Aryan and Dravidian speakers only occurred as the Indo-Aryans expanded well into and beyond the Punjab.[41]

While Dravidian languages are primarily confined to the South of India today, there is a striking exception: Brahui (which is spoken in parts of Baluchistan). It has been taken by some as the linguistic equivalent of a relict population, perhaps indicating that Dravidian languages were formerly much more widespread and were supplanted by the incoming Indo-Aryan languages. Certainly some Dravidian place-names are found in now Indo-Aryan regions of central India,[42] and possibly even as far northwest as Sindh.[43]However, it is now argued by Elfenbein that the Brahui could only have migrated to Balochistan from central India after 1000 CE, because of the lack of any older Iranian (Avestan) loanwords in Brahui. The main Iranian contributor to Brahui vocabulary, Balochi, is a western Iranian language like Kurdish, and moved to the area from the west only around 1000 CE.[44]

As noted above, retroflex phonemes in early Indo-Aryan cannot identify the donor language as specifically Dravidian. Krishnamurti argues the Dravidian case other features: "Besides, the Ṛg Veda has used the gerund, not found in Avestan, with the same grammatical function as in Dravidian, as a non-finite verb for 'incomplete' action. Ṛg Vedic language also attests the use of iti as a quotative clause complementizer." However, such features are also found in the indigenous Burushaski language of the Pamirs and cannot be attributed only to Dravidian influence on the early Rigveda.[45]

Munda[edit]

Kuiper identified one of the donor languages to Indo-Aryan as Proto-Munda.[46] Munda linguist Gregory D. Anderson states: "It is surprising that nothing in the way of quotations from a Munda language turned up in (the hundreds and hundreds of) Sanskrit and middle-Indic texts. There is also a surprising lack of borrowings of names of plants/animal/bird, etc. into Sanskrit (Zide and Zide 1976). Much of what has been proposed for Munda words in older Indic (e.g. Kuiper 1948) has been rejected by careful analysis. Some possible Munda names have been proposed, for example, Savara (Sora) or Khara, but ethnonymy is notoriously messy for the identification of language groups, and a single ethnonym may be adopted and used for linguistically rather different or entirely unrelated groups".[47]

Austroasiatic languages

The Austroasiatic languages,[2] in recent classifications synonymous with Mon–Khmer,[3] are a large language family of continental Southeast Asia, also scattered throughout India, Bangladesh, and the southern border of China. The nameAustroasiatic comes from the Latin words for "south" and "Asia", hence "South Asia". Of these languages, only Khmer, Vietnamese, and Mon have a long-established recorded history, and only Vietnamese and Khmer have official status (in Vietnam and Cambodia, respectively). The rest of the languages are spoken by minority groups. Ethnologue identifies 168 Austroasiatic languages. These form thirteen established families (plus perhaps Shompen, which is poorly attested, as a fourteenth), which have traditionally been grouped into two, as Mon–Khmer andMunda. However, one recent classification posits three groups (Munda, Nuclear Mon-Khmer and Khasi-Khmuic)[4] while another has abandoned Mon–Khmer as a taxon altogether, making it synonymous with the larger family.[5]

Austroasiatic languages have a disjunct distribution across India, Bangladesh and Southeast Asia, separated by regions where other languages are spoken. They appear to be the autochthonous languages of Southeast Asia, with the neighboringIndo-Aryan, Tai–Kadai, Dravidian, Austronesian, and Tibeto-Burman languages being the result of later migrations.[6]

,,,

Proto-language

Main article: Proto-Mon–Khmer language

Much work has been done on the reconstruction of Proto-Mon–Khmer in Harry L. Shorto's Mon–Khmer Comparative Dictionary. Little work has been done on the Munda languages, which are not well documented. With their demotion from a primary branch,[citation needed]Proto-Mon–Khmer becomes synonymous with Proto-Austroasiatic.

Paul Sidwell (2005) reconstructs the consonant inventory of Proto-Mon–Khmer as follows:

| *p | *t | *c | *k | *ʔ |

| *b | *d | *ɟ | *ɡ | |

| *ɓ | *ɗ | *ʄ | ||

| *m | *n | *ɲ | *ŋ | |

| *w | *l, *r | *j | ||

| *s | *h |

This is identical to earlier reconstructions except for *ʄ. *ʄ is better preserved in the Katuic languages, which Sidwell has specialized in. Sidwell (2011) suggests that the likely homeland of Austroasiatic is the middle Mekong, in the area of the Bahnaric and Katuic languages (approximately where modern Laos, Thailand, and Cambodia come together), and that the family is not as old as frequently assumed, dating to perhaps 2000 BCE.[6]

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

April 29, 2015