Kaalaadhan: Luxembourg where accountants outnumber police -- Jennifer Rankin. How multinational corporations like Pepsi use intra-group loans to pay taxes to tax haven Luxembourg

Luxembourg is a sovereign nation the size of a Bharatiya Panchayat. It has a population of 524,853 (October 2012) and a tax haven next only to Cayman Islands. Now 1600 multinationals have set up their address in one street, one building 5, rue Guillaume Kroll

A company protected under Double Taxation Avoidance Treaty (DTAT) between Luxembourg and India is Pepsi Bottling Group.

Now the concern is how internal loans are shown in the accounts of multinational corporations to avoid paying taxes to countries like India, where companies like Pepsi get their income. Income is from India and tax is paid to Luxembourg under the DTAT. Like this, many nations are losing their legitimate tax revenues.

This is an instance of corporate kaalaadhan which SIT headed by Justice Shah should investigate.

Kalyanaraman.

G20 experts to act on corporations’ internal loans that help cut tax

Move against intra-group financing could destroy whole area of financial services in Switzerland and Luxembourg

Tax experts responsible for the G20-led shakeup of international tax rules are discussing radical measures to bar global corporations from using internal loans, that bear no relation to their borrowing needs, in order to avoid tax.

If adopted, the move could wipe out vast swaths of the financial industry at a stroke in countries such as Switzerland and Luxembourg, which have for years courted the intra-group financing offices of multinational firms by operating friendly local tax regimes.

Raffaele Russo, one of the OECD tax experts leading the reform programme that has come in response to increasingly aggressive tax planning by multinationals, told the Guardian that if the proposals were backed, “this will be the end of [tax] base erosion and profit shifting using intra-group financing”.

Measures to tackle multinationals taking large tax deductions for interest payments on loans within the same group are hinted at in a report published in September. It said: “A formulary type of approach which ties the deductible interest payments to external debt payments may lead to results that better reflect the business reality of multinational … groups.”

While other measures are also on the table, pressure to take radical steps to stamp out intra-group loans contrived for tax avoidance has grown this week after revelations about tax agreements rubber-stamped by the Luxembourg tax office.

Luxembourg finance minister Pierre Gramegna used a public session during a meeting of European finance ministers in Brussels to deliver a statement in reaction to this week’s revelations about tax agreements with multinationals.

“My country [has] come under scrutiny in the latest days. The rulings of Luxembourg are being done according to the national laws of Luxembourg and also according to international conventions. What is being done is totally legal.” He acknowledged rulings and weak tax treaties had led to “situations where companies are paying no taxes or very little taxes [which] is obviously not a good result”.

He noted, however, that many other EU countries offered companies advance tax agreements for their tax structures, but said that more must be done to coordinate global efforts led by the G20. “If we want to change [the] legal framework we will have to do it all together.”

The Guardian this week published an investigation into several multinational companies with large intra-group lending activities based out of Luxembourg. The investigation was part of a wider analysis, involving journalists in more than 20 countries, scrutinising hundreds of ATAs awarded by the local tax office.

Among the findings was an internal financing company within drug group Shire, best known for its treatments for ADHD. The tiny lending unit – with staff costs last year of less than $50,000 – lent more than $10bn to other group companies, sometimes at 8% or 9% interest.

Neither the scale of lending nor the interest rates charged bore much relation to Shire’s global borrowing needs. The Guardian investigation showed, however, that Shire’s controversial structures had allowed the lending unit to amass more than $1.9bn in interest income over five years while incurring tax of less than $2m for four of the years.

Asked why Shire’s Luxembourg unit had made large loans to sister companies and charged high rates of interest – neither seemingly reflecting the group’s overall borrowing needs or financial strength – the drugs firm declined to comment.

In a statement, it said its Luxembourg lending unit was “part of our overall treasury operations”, adding “we have a responsibility to all our stakeholders to manage our business responsibly; this includes managing our tax affairs in the interests of all stakeholders”.

Tax advisers Grant Thornton set out the benefits of Luxembourg in a presentation last year saying the Grand Duchy was “pre-eminent within the financial sector … often used as a treasury/financing location”. The presentation continued: “Luxembourg’s government understands the need for a close working relationship with business.” It added: “It is possible for companies to obtain an advance tax agreement [ATA] … commonly obtained for financing structures.”

More than 40 nations, representing over 90% of the world’s economy, are signed up to the G20-led reform agenda. They acknowledge that multinationals and their tax advisers have stretched current rules to breaking point and that there is an “urgent need” to rein in the avoidance industry, which was draining tax receipts and threatening the authority of governments.

Tasked with leading the reform project, the Paris-based Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), in September published the first wave of proposals, which have been agreed. A second wave – expected to include measures to tackle excessive interest deductions – is expected in the autumn of 2015.

http://www.theguardian.com/business/2014/nov/07/g20-tax-experts-shakeup-corporations-internal-loans

Jean-Claude Juncker's real scandal is his tax-haven homeland of Luxembourg

The favoured candidate for the presidency of the European Commission has dedicated himself to making society less fair

Jean-Claude Juncker: 'The odds are he has made your life harder.' Photograph: Geert Vanden Wijngaert/AP

Comrades! Allow me to introduce to you the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats at the European parliament's favoured candidate in this week's election for the next president of the European Commission. Fraternal greetings please for Mr Jean-Claude Juncker.

I admit that Jean-Claude does not appear at first glance to be the man most likely to promote the European socialists' goal of "ensuring that our societies become fairer". Nor at a second, third or fourth glance either. Juncker has dedicated his career to ensuring that society becomes less fair; that wealthy institutions and individuals can avoid the taxes little people and small businesses must pay. "Everywhere do I perceive a certain conspiracy of rich men seeking their own advantage," wrote Sir Thomas More in 1516. He might have been describing Mr Juncker.

The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg's Ruritanian title carries a whiff of archaic glamour. But it is nothing more than a piratical state. The only difference between pirates old and new is that instead of using muskets and cannons to seize other people's money, Luxembourg uses accountants.

We don't see it because the EU turns the British upside down. Conservatives deploreEurope because it threatens national sovereignty, even though the euro is bringing cuts to welfare states and wages conservatives approve of in other circumstances. The liberal-left thinks of itself as internationalist and therefore bites its tongue and mumbles its words when the EU promotes policies it would condemn if they came from Westminster.

Please put your prejudices aside, if you can, and concentrate instead on why Luxembourg matters.

What heavy industry the duchy had was vanishing by the early 1990s. During Juncker's reign as Luxembourg's prime minister from 1995 to 2013, the duchy reinvented itself as Europe's largest tax haven: a land fit for Bernie Madoff to trade through. It allowed conglomerates to avoid tax through intermediate holding companies solely.

BBC's Panorama uncovered documents that neatly illustrated how the companies redistribute wealth. The UK headquarters of GlaxoSmithKline established a Luxembourg branch in 2009. The subsidiary lent £6.34bn to GSK in the UK. The UK company paid nearly £124m in interest back to the Luxembourg subsidiary. The revenue could not tax the interest at the then UK level of 28% and collect £34m. Instead, the Luxembourg tax authorities levied a tax of 0.5%, or £300,000. The deal was pin money by Luxembourg's standards.

Virtually every large British company has moved capital through Luxembourg including, it appears, my managers here at the Guardian and Observer, though they say such a structure was not about saving the group "any UK corporation tax when compared with an onshore structure".

The revenue endured the greatest scandal in its history when it allowed Vodafone to pay just £1.25bn of an alleged £6bn tax bill from a takeover organised in Luxembourg. TheFinancial Times estimates that Luxembourg's financial sector has grown from virtually nothing in the 1980s to €3tn today.

Richard Brooks, the author of The Great Tax Robbery, tells me Luxembourg is a far greater menace than the Caribbean laundromats. It benefits from the European Union's free movement of capital, while the Cayman Islands, say, cannot. More dangerously, it inspires the Netherlands, Ireland and other EU states following beggar-thy-neighbour tax policies to join it in a race to the bottom.

If your services are being cut or taxes are going up, if you run a small business that cannot compete with Amazon or another large entity, the odds are that Jean-Claude Juncker's Luxembourg has made your life harder.

The basic standards of honest government ought to disbar him from the presidency. The European Commission he presumes to lead is investigating the Luxembourg he created. It wants to know how Amazon could put £11bn through its Luxembourg-based subsidiary in 2013, while paying only £4m in UK corporation tax on goods sold to British customers, packaged in British warehouses and moved on British roads. Ireland and the Netherlands are co-operating with the inquiry into illicit tax advantages. Luxembourg, however, has compelled the commission to go to court to secure the relevant documents.

Juncker is asking to be put in charge of a European Commission that is engaged in legal action against his tax regime. He will be supervising an investigation into deals he insisted as prime minister of Luxembourg should remain hidden. I do not see how he can be trusted with such power, not least because the EU's lax rules place no obligation on Juncker to declare a conflict of interest.

And this is the man Europe's "progressives" want to make president of a continent. François Hollande and other socialist and social democrat leaders endorsed Juncker at a meeting in Paris last month.

They, and Europe's green leaders too, believe that the centre-right "won" the last European elections. The rest of us could not help but notice the success of racists and know-nothing nationalists. Our progressive leaders disagree. To their mind, Juncker triumphed and must be rewarded. Their support comes at a price, of course. The socialists expect Juncker to cuts deals and scratch backs: promote a German social democrat here and an Italian feminist there.

I am pleased to say that the British Labour party is upholding the honour of the European left. Its 20 members of the European parliament will not vote for a candidate who believes in austerity for the many and tax breaks for the few, whatever payoffs he promises. They believe socialists and greens from other countries will ignore their leaders and deny Juncker victory in this week's secret ballot. I hope for the sake of the centre-left they are right.

Commentators have been saying the left is in crisis for so long it is easy to dismiss them with a shrug and a yawn. But the success of the far right cannot be breezily ignored. It tells working-class voters that conventional politicians are all the same. The choices they pretend to offer are a fraud. While the elite prattles about its principles in public, it rigs the system in private.

The worst damage Europe's socialists will inflict when they endorse a man who has done as much harm as any politician his generation is easy to describe. They will prove the extremists right.

Havens like Luxembourg turn ‘tax competition’ into a global race to the bottom

An overhaul of the Grand Duchy’s corporate tax law and administration is required

Occupying a damp 1,000 square miles where the French, German and Belgian borders meet, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg is a far cry from the palm-fringed tropical island tax haven of popular imagination.

In fact the country owes its status as the world’s premier corporate tax haven to its position at the heart of Europe. A founding member of the European Economic Community in 1957, Luxembourg enjoys all the freedoms governing investment in what is now the European Union. These and a network of taxation agreements with all the world’s leading economies ensure the Grand Duchy is accepted in a club of leading nations that share basic principles on how to tax corporations operating across national borders.

Such a privilege would never be afforded to island-in-the-sun tax havens. Large economies, such as the US and UK, typically block multinationals from shifting profits to low-tax territories by imposing ‘withholding taxes’ on payments leaving their borders. Luxembourg, by contrast, is a respected member of the international economic club, and assumed therefore to tax its companies fully; it even has a corporate income tax system with a 29% rate that is now relatively high by international standards. So money flows into the country tax-free.

Secretly, however, Luxembourg is a tax haven, offering a range of ways in which payments that reduce a multinational’s taxable profits in a country such as the UK or US can escape tax when received in the Grand Duchy. These include: exempting income diverted to foreign branches of Luxembourg companies in places like Switzerland and Ireland, tax relief for paper investment losses, and the approval of complex ‘hybrid’ financial instruments and corporate structures within its borders. Top FTSE 100 firms like Vodafone and GlaxoSmithKline are known to have exploited these opportunities to channel billions through Luxembourg companies.

When a multinational approaches the Luxembourg tax authorities with a scheme employing one of these tactics, after a meeting or two to chew over the details a senior official rubber-stamps the plan and the company walks away with a big tax break. In this way the Grand Duchy behaves like the club member who enjoys all the benefits of membership while quietly pilfering from the kitty.

It might be an underhand way to run a tax system, but it serves Luxembourg well. The country has the highest levels of foreign investment inflows and outflows in the EU, taking a small but valuable tax levy as the money washes through. Corporate income taxes, at 5% of GDP, consequently form a far greater share of Luxembourg’s finances than they do in other EU countries.

As the world cottons on to Luxembourg’s tax poaching, pressure for reform grows. So does embarrassment for the new president of the European Commission, Jean-Claude Juncker, who as prime minister of the Grand Duchy for 18 years until 2013 presided over the activity. Revelations of precisely how its corporate tax avoidance factory works give the lie to Juncker’s repeated protestations that the country is not a tax haven.

Investigations by the European Commission into deals offered by Juncker’s government to Amazon and Fiat might or might not conclude that they constituted anti-competitive ‘state aid’. But these inquiries concern the possibility of ‘sweetheart deals’ for favoured companies, when the bigger problem is that Luxembourg offers major tax breaks to all companies – as long as they have enough money.

Neutering Luxembourg as a tax haven at the heart of Europe requires an overhaul of its corporate tax law and administration. A concerted effort coordinated by the OECD aims to bring many of the tax structures facilitated by Luxembourg to an end. But, even if its proposals are technically sufficient, it will take intense political pressure to force Luxembourg to implement them.

In the meantime, despite his claims to be spearheading the OECD’s work, George Osborne has enhanced the allure of Luxembourg’s tax breaks. In 2012 he drastically scaled back anti-tax avoidance laws targeted at multinationals’ so-called ‘controlled foreign companies’. These are tax laws that since 1984 have caught profits diverted by UK multinationals into tax havens. In a move specifically aimed at favouring finance companies established in Luxembourg, Osborne reduced the tax on their profits to no more than 5%.

Osborne’s changes are designed to make the UK an attractive place for multinationals to base themselves. They do so by accommodating predatory tax practices, in response to opportunities provided by countries like the Netherlands and Luxembourg. Other widely publicised tax breaks such as the ‘patent box’ special tax rate for income from intellectual property mimic concessions elsewhere.

This is the real harm that tax havens like Luxembourg cause. They turn ‘tax competition’ into a global race to the bottom, depleting the contributions of major corporations and leaving citizens to pick up the tab.

Richard Brooks is the author of The Great Tax Robbery - How Britain became a tax haven for fat cats and big business.

Luxembourg and Juncker under pressure over tax deals

Politicians in France, Germany and Netherlands protest at effect of laws passed by EC chief when the country’s prime minister

French, German and Dutch finance ministers have rounded on Luxembourg for allowing multinational companies to create complicated structures to avoid billions of dollars of tax.

Pressure is also mounting on Jean-Claude Juncker, the new president of the European commission and former long-serving prime minister of Luxembourg, who oversaw the introduction of laws that helped turn the tiny European country into a magnet for multinationals who are seeking to reduce their tax bills.

The calls for Luxembourg to stop arranging special deals that help corporations avoid tax came after a vast cache of 28,000 leaked tax papers from the Grand Duchy revealed the country had been rubber-stamping tax avoidance on an industrial scale. Details of the documents were revealed by 80 journalists in 26 countries working with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), including the Guardian.

Wolfgang Schäuble, Germany’s finance minister, said the revelations about Luxembourg’s secret tax deals showed that the Grand Duchy had “a lot to do” to meet global standards.

The French finance minister, Michel Sapin, said such deals were “no longer acceptable for any country”. He added: “I wish that in a few years we never have to talk about something like this again.”

The Netherlands finance minister, Jeroen Dijsselbloem, who is also chair of the Eurogroup of all 18 finance ministers in the eurozone, said that Luxembourg was breaching international tax standards. “Many countries make agreements with companies to provide security. But these agreements need to comply with international standards. We still have some work here.”

At Westminster, Margaret Hodge, chair of the Commons public accounts committee, said: “[Juncker has] just taken over the European commission, [yet] he’s presided over the biggest exploitation of European nations in his own little country for decades.”

Despite the criticism, Juncker was said to be “very serene” and “cool”. Juncker, who took over as president of the commission on Saturday after serving 19 years as premier of Luxembourg, was scheduled to take part in a public debate on Thursday in Brussels. But he pulled out on Wednesday night as news organisations prepared to publish the leaked tax documents.

His official spokesman said Juncker did not feel under any pressure to explain how he oversaw changes to Luxembourg’s tax laws. He said: “If he were a teenager I’d say he was cool.”

Many of the tax deals – secured for companies including Ikea, Pepsi, Burberry, FedEx and Procter & Gamble – were aided by laws written during Juncker’s term of office.

The Danish tax minister, Benny Engelbrecht, said the revelations were “shocking”. “Tax payments are down to percentages that are so crazy that you can almost not even describe the challenges that they create for other countries,” Engelbrecht told the Danish paper Politiken.

Juncker is credited with helping transform Luxembourg’s economy from one relying on agriculture and steelmaking into a low-tax centre for financial services. His changes turned the small nation into the world’s richest country with a per capita income of $111,000, compared with $39,000 in the UK, according to the World Bank.

Luxembourg’s current prime minister, Xavier Bettel, called an emergency press conference to defend his country. “These rulings, as they have been done in Luxembourg, are in line with international and national rules,” he insisted. Pierre Gramegna, the Grand Duchy’s finance minister, said the comfort letter tax deals exposed in the leaked documents are “not something that’s particular to Luxembourg. It exists in a lot of countries.”

Gramegna will face tough questioning from his counterparts across Europe on Fridaywhen EU finance ministers meet in Brussels on Friday. Up for discussion is a new anti-tax-avoidance measure targeted at multinationals.

Luxembourg is already the subject of EU probes into claims that local tax agreements for Amazon and a subsidiary of Fiat amount to state aid.

Hodge, who hauled the bosses of Starbucks, Google, Amazon and the big four accountancy firms to parliament to explain their roles in UK tax avoidance, told the Guardian that Juncker should be forced to come clean about his role in turning Luxembourg into a low-tax haven for multinationals.

“I think he should come clean and talk about it, certainly try to explain it,” she said. “How can we know he’s working in the interest of Europe when as prime minister in Luxembourg he has exploited populations in every European country and elsewhere for decades?”

Ronen Palan, professor of international relations at City University, London, a specialist on tax havens, said: “Luxembourg is extremely secretive. I can’t underline [enough] how aggressive they are in denying that they are a tax haven. Now we have evidence. For the first time we have real evidence as opposed to supposition, as opposed to suspicions and so forth.”

The revelations have sparked political outrage across the world. The Australian tax office said it had launched an investigation into whether multinational firms operating in Australia were avoiding tax by using deals arranged through Luxembourg. ICIJ documents show that Ikea’s Australian arm has paid hardly any tax on an estimated $1bn profit earned since 2003, according to the Australian Financial Review’s report on the leaked documents.

Guy Verhofstadt, president of the alliance of liberals and democrats for Europe and former prime minister of Belgium, said: “Recent allegations against the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg on tax avoidance practices need to be clarified immediately. The commission should come to the European parliament immediately to explain if these practices are in accordance with EU law. It must be made clear, if the setup chosen by Luxembourg is legal or not.”

The anti-corruption campaign group Transparency International said: “EU ministers must now take action to end the secrecy of corporate tax deals in Europe. The Luxleaks deals could not have been kept secret if all companies were required to report details of their tax payments in every country where they operate.”

Oxfam’s tax adviser, Catherine Olier, said: “The leaks underline the scale of tax dodging – it’s not just one isolated scandal; we’re talking about a whole industry making profits disappear. Tax-dodging results in both developing and European countries missing out on billions in tax. This is money that would be much better spent on healthcare or education rather than lining already wealthy corporate pockets.

“G20 leaders meeting next week should adopt ambitious rules that will benefit all countries, including the developing countries that suffer most from corporate tax dodging.”

The anti-poverty campaign group ActionAid said: “This exposure of the industrial scale of global tax avoidance involving Luxembourg clearly highlights the need for global action.

“A fundamental rethink of the world’s tax system is needed, that puts all the issues on the table and includes all countries, including developing countries, as equal partners, to tackle these kinds of abuse.”

• This article was amended on 7 November. The original said that the EU competition commissioner, Margrethe Vestager, warned Luxembourg she was considering launching a series of fresh investigations into state aid. Commissioner Vestager actually said: “We have at this stage not yet formed an opinion about these rulings and a possible formal follow-up by the Commission ... we will be vigilant to enforce state aid control in fair and justified manner.”

UK aid investments target tax havens

Private sector arm of DfID and other EU development institutions channel significant investments to offshore havens, study finds

More than two-thirds of the investments made by the private sector arm of the UK’s aid programme last year were channelled through “notoriously secretive” tax havens, according to a report that calls on European development agencies to be more transparent and accountable in their business dealings.

The study, by the European Network on Debt and Development (Eurodad), found that billions of euros intended for projects in developing countries are being routed through some of the world’s most secretive financial centres, allowing businesses to avoid taxes and the attendant regulations.

Eurodad notes that the UK’s CDC – formerly the Commonwealth Development Corporation, which is wholly owned by the Department for International Development (DfID) – makes frequent use of such jurisdictions.

In 2013, CDC invested in nine funds, six of which used tax havens in Mauritius, Singapore, Guernsey and Luxembourg. Between them, the six funds received $553m (£441m).

“CDC’s portfolio as of 31 December 2013 shows that both its direct and its indirect investment model rely heavily on secrecy jurisdictions,” says the report. “A massive 118 out of a total of 157 fund investments go through secrecy jurisdictions. Between 2000 and 2013, these funds received a total of $3.8bn in CDC commitments.”

Sixty-nine of the funds are registered in Mauritius ($1.8bn), while 26 are registered in the Cayman Islands ($909m). CDC is designed to be a “pioneering investor” in developing countries. Its net investments count as official aid, and towards meeting the UK commitment to spend 0.7% of gross national income as aid. Almost all of CDC’s money goes through investment funds, which then invest in businesses in developing countries.

The Eurodad report – Going Offshore – discerned a similar pattern of tax haven usage in other European national development finance institutions (DFIs).

As of June this year, the Belgian Investment Company for Developing Countries (BIO) was involved in a total of 42 investment funds, including 30 domiciled in jurisdictions that feature in the top 20 of the Tax Justice Network’s financial secrecy index (FSI). The investments amounted to $207m.

At the end of last year, 46 of the Norwegian Norfund’s 165 active investments were channelled through jurisdictions that appear in the FSI’s top 20. The investments totalled $339m.

At least seven of the 46 projects involving the German DFI Deutsche Investitions und Entwicklungsgesellschaft (DEG) were structured through major tax havens such as the Cayman Islands and Mauritius.

The report’s author, Eurodad policy analyst Mathieu Vervynckt, said: “Developing countries lose hundreds of billions of euros every year through tax avoidance and evasion by companies. It therefore seems very contradictory for DFIs, whose mandate is to promote development and end poverty, to route so much support through notoriously secretive financial centres that maintain these practices.”

By doing so, he added, bilateral and multilateral DFIs were essentially funding and legitimising the offshore industry.

The report suggests ways in which DFIs can improve their transparency, including: investing only in companies and funds that are willing to “publicly disclose beneficial ownership information and report back to the DFI their financial accounts on a country-by-country basis”; ensuring the funds in which they invest are – where possible – registered in the country of operation, and being fully accountable for their own operations and those of their clients.

Eurodad is also calling for an intergovernmental tax body to be set up under the auspices of the UN to allow developing countries an equal role in the global reform of tax rules.

“We are urging these institutions to stop supporting companies that use tax havens and make sure that details of all operations are open to the public,” said Vervynckt. “After all, DFIs are public institutions with a development mandate, so it’s only right to demand that they should be accountable to the taxpayers that pay for them and the people in the developing countries that they are supposed to help.”

A spokesperson for CDC said: “CDC investments are helping create the jobs and growth needed to lift people out of poverty. Businesses we support employ over 1 million people in developing countries and last year paid over £2.3bn in local taxes.

“CDC requires the businesses we invest in to pay all taxes that are due of them and avoids making investments in jurisdictions that are not compliant with the OECD’s internationally agreed standards on tax transparency.”

Speaking before the G8 summit in June last year, David Cameron said financial fairness was central to development and promised to clamp down on secrecy.

“It is about proper companies, proper taxes and proper global rules ensuring that openness delivers the benefits it should for rich and poor countries alike,” he said. “Aid is important but these things matter just as much. Now is the time. This is the agenda. The world should get behind it.”

In May, the Guardian revealed that CDC has invested more than $260m of aid money in builders of gated communities, shopping centres and luxury property in poor countries in Latin America, Africa and Asia.

http://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2014/nov/04/uk-aid-investments-target-tax-havens/print

Morning Mail: Luxembourg tax leaks and G20, AC/DC's Phil Rudd, SA fire warnings and Miriam Margolyes

Guardian Australia’s morning news briefing from around the web

Good morning folks, and welcome to the Morning Mail – sign up here to get it straight to your inbox every weekday morning.

Luxembourg tax files and G20

After yesterday’s revelations about how the tiny state of Luxembourg has facilitated global tax avoidance on an industrial scale,

G20 leaders are under pressure to crack down on the practice, and Labor’s Sam Dastyari says a Senate inquiry will look ask questions about the involvement of major Australian companies. http://www.theguardian.com/australia-news/2014/nov/07/morning-mail-luxembourg-tax-leaks-and-g20-acdcs-phil-rudd-sa-fire-warnings-and-miriam-margolyes

Luxembourg tax files: the Australian companies engaged in tax avoidance

Ikea, the Future Fund, Lend Lease, AMP and Macquarie Group are among dozens of Australian companies using elaborate, legal structures to cut their tax bills, leaked documents reveal

The largest ever leak of Luxembourg tax deals has exposed the complex schemes used by hundreds of Australian and international companies to drastically shrink their tax bills.

The Future Fund, Lend Lease, AMP and Macquarie Group are among dozens of Australian companies whose tax arrangements are revealed in nearly 28,000 pages of leaked documents, according to analysis by the Australian Financial Review.

The Australian arm of the furniture retailer Ikea paid less than 1% tax over the past 12 years, the AFR reported.

Ikea’s Australian stores turned over $4.76bn between 2002 and 2013. But they paid $2.67bn in supply fees to another independent Ikea entity, and a further $904m to other Ikea companies in Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

The arrangement allowed the Swedish furniture giant to declare a pre-tax profit of $103m, on which it paid just $31m in tax – while its sales surged 500%.

Investigation of the documents has been led by the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. The documents, showing extensive use of shell companies, hybrid debt structures, internal loans and royalty payments, are available on its website.

The documents include details of a deal struck in 2010 between the Future Fund and Luxembourg that appears to limit income tax on trades in specific distressed debts on a $500m European portfolio to just $136,000 a year.

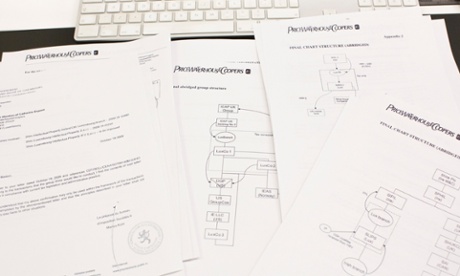

A management buyout deal negotiated for Lend Lease in 2003 by the accounting firm PriceWaterhouseCoopers saw lucrative management fees routed from Luxembourg through Bermuda and subcontracted back to Europe, cutting the tax rate on these payments to less than 3%.

Lend Lease was bought out of the business by Macquarie Group, which sold its 56% stake to the American funds manager BlackRock last year. Both Australian companies said they comply with domestic and international tax laws.

The secret tax arrangements of many of the world’s largest companies are contained in the leak, including Pepsi, AIG, Coach and Deutsche Bank. The documents show one Luxembourg address, 5 rue Guillame Kroll, is registered to more than 1,600 businesses.

Schemes such as these are legal, but their exposure will build momentum for a crackdown on global tax avoidance at this month’s G20 meeting in Brisbane.

The treasurer, Joe Hockey, has labelled “tax cheats” thieves and already agreed to increase transparency and crack down on profit shifting by having tax authorities share more information across borders.

But Labor said the government rejected measures that would prevent an additional $1.1bn being sent offshore, and cut more than $180m from the Australian Tax Office’s staff budget.

Tax minimisation strategies employed by Australia’s largest companies cost the federal government more than $8bn in revenue a year, a report by the union United Voice and the Tax Justice Network found.

Oxfam estimated similar techniques deprived developing nations of $114bn a year.

Dr Mark Zirnsak, who runs the Australian branch of the Tax Justice Network, said the new revelations vindicated many of the concerns it had been raising and “add absolute weight to Australia taking a real lead on cracking down on this sort of tax avoidance”.

Most recent

Top story

Luxembourg, the country where accountants outnumber police 4:1

Grand Duchy advertises itself as ‘business-friendly’ haven amid leak showing it helped multinationals save millions in tax

Welcome to Luxembourg, where accountants outnumber the police by four to one – and people enjoy some of the highest living standards in the world.

“Conquer the world from your Luxembourg headquarters,” is the title of one government-sponsored marketing brochure promoting the Grand Duchy and its “business-friendly legal and fiscal framework”. “Political decision-makers are very accessible to companies,” it promises.

The big four accountancy firms tend to agree, if a 2009 presentation by PricewaterhouseCoopers is anything to go by: the authorities are “flexible and welcoming”, “easily contactable” and offer “a readiness for dialogue and quick decision-making” it said in the document, part of a trove of documents obtained by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and shared with the Guardian.

The big four are huge global enterprises that employ 750,000 people in total and have combined earnings of $117bn (£74bn), according to the latest figures – making them bigger than the economy of Angola.

Their footprint is especially large in Luxembourg, where they employ 6,200 people – among a population of 550,000.

The Grand Duchy’s economy has come to be dominated by high finance since the decline of its steel factories. Today, financial services are Luxembourg’s biggest earner, accounting for more than a third of the national income. Almost half the workforce are foreigners, with 44% of employees commuting in daily from France, Germany and Belgium.

Despite the financial crisis, accountancy has been booming. Deloitte has increased its Luxembourg staff by 142% in less than a decade to 1,700.

PwC is comfortably ahead of Deloitte, its nearest rival. The biggest of the big four, which once described itself as “an ambassador of Luxembourg abroad”, it employs more people in Luxembourg than the country’s police force: it has 2,300 staff, while the gendarmerie has 1,600 officers. That makes it the country’s ninth largest employer, behind steelmaker ArcelorMittal and French bank BNP Paribas.

The talents, as PwC likes to call its staff, are housed in its state-of-the-art Crystal Park headquarters, a wood and glass eco-friendly building that opened last month. Last year, PwC Luxembourg earned €288m (£225m), an 11% increase on 2012. Tax was one of its best-performing divisions, bringing in €78m (£61m), up 15% on the previous year.