January 7, 2013

See http://www.arth.upenn.edu/phs/index.html about Pakistan Heritage Society and work of Michael Meister on Salt Range temples.

Endangered heritage

From the Newspaper | Majid Sheikh

THE Indus Valley Civilisation, stretching over the area that today constitutes Pakistan, is probably the oldest known to mankind.

From the remote northern reaches of the Hindu Kush mountains to the Indus River delta in the south, and along the vast expanses of land on both sides of the Indus and its tributaries, exist traces of a rich past going back in antiquity.

Without doubt it is the largest ancient civilisation in the world, and yet no place else on earth is such amazing heritage under more threat than in Pakistan.

The earliest known ‘food-producing’ era (7,000-5,000 BC) was Mehrgarh in the ‘kachi plains’ of Balochistan. This is the oldest known ‘settled village life’ habitation, where crops were produced, skins tanned, copper mined and metal worked.

Life at Mehrgarh existed till 2,600 BC. It was roughly in this time period (3,300-2,800 BC) that the Harappan cities along the Ravi came about. Mohenjodaro and other Sindh cities by then were busy trading towns.

Experts believe that the cities of Multan, Hyderabad, Lahore and Peshawar came about in this time period. Numerous smaller towns like Bhera sprouted up. All of them were on major trading routes.

Immensely rich that Pakistan is in its heritage, there seems to be a reluctance to accept this heritage. History in Pakistan, it seems, starts from the time the Afghan invader Mahmud of Ghazni pillaged the areas that are Pakistan and beyond. In hundreds of years of Muslim rulers, foreign invaders cemented the mentality that all cultures alien to the invader did not deserve consideration.

Pakistan, it could be reasonably argued, was born out of such a worldview. From this, right or wrong, flows the undeniable fact that culture is a low priority of Pakistani life. But then what is culture?

The poet Faiz summed it up succinctly when he said: “Everything that exists on the ground is our culture.” This is exactly what Unesco’s World Heritage Convention states, warning that human intervention, as well as natural causes, is destroying the heritage of the world, and needs to be reversed.

No place else is this more relevant than in Pakistan. We rightly vent anger and dismay at the destruction of the Buddha statues in Bamiyan in Afghanistan, yet what is happening in Pakistan is even more dire.

Mind you, before Pakistan came into being, the British also destroyed a lot of our heritage in the name of modernisation and security. The rest they stole for their museums in the name of ‘human progress’. Such are the ways of rulers who have no accountability.

But we must be concerned with what is left. Here it must be pointed out that the Indus Valley was the place where Hinduism and Jainism emerged, and Buddhism flourished. From the Hindu Kush to the coast of Makran, from the mountains of Afghanistan to the plains of Punjab, thousands of monuments exist that were once part and parcel of our lives.

Today they are fast disappearing. Even ancient sites like Mehrgarh, Harappa and Mohenjodaro are starved of funds to preserve, let alone conserve.

As they shrink and get damaged by human intervention, Pakistan is losing its immensely rich heritage. That we do not love and cherish our past is surely reflected in our regrettable condition today. Without a past and a woeful present, one shudders to think what the future will be like.

One can dwell at length on the plight of cities like Multan, Hyderabad, Lahore, Peshawar and even smaller towns like Bhera. Lahore’s walled city today is 70 per cent commercialised, with all its ancient walls knocked down to make way for commercialisation. When the Aga Khan Trust for Culture intervened, the trader-politicians of Lahore literally chased them out.

On the rebound, a former prime minister requested the Aga Khan to help conserve old Multan, and it goes to the credit of the Ismaili leader that he obliged.

One hears that the Punjab rulers are now making life difficult for the researchers in Multan. A potent combination of mercantile and religious interests is keeping the conservation of our past at bay. Of this there is no doubt.

Take a small town like Bhera, the place where Alexander clashed with the local ruler called the ‘Puru’, or Porus in its Latinised version.

Mind you Porus defeated the foreigner, even though respectable Western historians follow the Greek description of how their leader fared. But then Bhera remains an exquisite walled city that is disintegrating. Ancient Hindu temples have been knocked down and the houses of members of a religious sect have been reduced to ashes. The once old centre of power is today a ghost town.

As an example take the condition of the magnificent Lahore Fort. It is slowly disintegrating because of neglect. Sadly, Unesco is only moved if ‘officially’ approached. The official world does not want Pakistan to have too many endangered sites, and in that they manage well.

Pakistan, the world and Unesco are losing out to such manipulation. Experience tells us endangered sites are saved when the ‘relatively richer’ sections of society stand up to save their world. To take from Pakistan is easy and has reduced the country to ruins. It is time they gave something back. The government one should not rely on. Only then will the future seem worth the fight.

The writer is a senior commentator with a focus on heritage and economics.

http://dawn.com/2013/01/07/endangered-heritage-2/

Salt Range Temples, Pakistan

Michael W. Meister, W. Norman Brown Professor, Department of the History of Art, University of Pennsylvania, and Curator, Asian Section, University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, has served as Chair, Department of South Asia Studies, and Director, South Asia Center

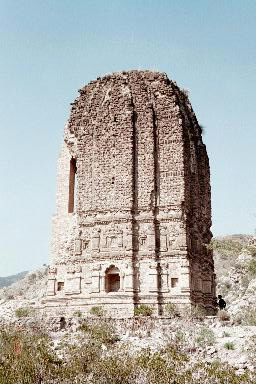

Along the Indus river and in the Salt Range mountains, temples dating from the sixth to the early eleventh century survive in upper Pakistan. A joint project with Professors Abdur Rehman, past Chairman of the Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, and Farid Khan, founder of the Pakistan Heritage Society, has begun to analyse and document these important monuments in the history of South Asian temple architecture with funding from the University of Pennsylvania. Two seasons of excavation have been carried out at the site of North Kafirkot.

A preliminary review and analysis of this tradition, "Temples Along the Indus," has been published in the University of Pennsylvania Museum's journal, Expedition, 38.3 (1996): 41-54. (The text as well as a preliminary typescript of this article are available on the Web.)

A preliminary review and analysis of this tradition, "Temples Along the Indus," has been published in the University of Pennsylvania Museum's journal, Expedition, 38.3 (1996): 41-54. (The text as well as a preliminary typescript of this article are available on the Web.)

We discovered an important new temple designated temple E through excavations undertaken at north Kafirkot in 1997. A report on both seasons of excavation has been published inExpedition. 42.1 (2000): 37-46.

We discovered an important new temple designated temple E through excavations undertaken at north Kafirkot in 1997. A report on both seasons of excavation has been published inExpedition. 42.1 (2000): 37-46.

(See also a full list of project publications below.)

Recent views of Kafirkot in Feb. 2000 following excavation are also available, as well as two hypothetical reconstructions of temple E based on neighboring temple A.

Salt Range Workshop

An international Workshop on the Salt Range Culture Zone was held at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Wisconsin, Madison, in April 2004, with the sponsorship of the American Institute of Pakistan Studies.Amb

Further archaeological work and exploration was begun at the Salt-Range site of Amb, in association with the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of the Punjab.

Amb, temples A and B

Support for this project has been received from the Middle East Center, South Asia Regional Studies Department, the University of Pennsylvania Research Foundation, and the American Institute of Pakistan Studies.

Sites

- Taxila, fifth-century encasement of Dharmarajika stupa

- Murti, stupa mound and Gupta-period temple-remains

- Katas, pilgrimage site, tank, and temples

- North Kafirkot, fortress, citadel, and temples;

destroyed temple at Kanjari-kothi compared to temple B; the site of the newly discovered temple E is just south of temple A. - Bilot (South Kafirkot), fortress, citadel, and temples

- Mari-Indus, four temples and habitation site

- Kalar, brick temple

- Amb, fort and two temples

- Malot, temple and gateway

- Shivganga, grove, tank, and temple ruins

- Nandana, fort, temple, and platform

For more views of these monuments, see also Selected Enlarged Views of Salt Range Temples.

Salt Range Temple Project Publications

Michael W. Meister- "Architectural Originality in the Punjab." Kalâ, Journal of Indian Art History Congress 6 (1999-2000): 27-35.

- "Chronology of Temples in the Salt Range, Pakistan." In South Asian Archaeology 1997, ed. Maurizio Taddei and Giuseppe De Marco. Rome: Istituto Italiano per l'Africa e l'Oriente, 2000, pp. 1321-39.

- "Crossing Lines, Architecture in Early Islamic South Asia," Res, Anthropology and Aesthetics 43 (2003): 117-30.

- "Gandhâra-Nâgara Temples of the Salt Range and the Indus." Kalâ, the Journal of Indian Art History Congress 4 (1997-98): 45-52.

- "Malot and the Originality of the Punjab." Punjab Journal of Archaeology and History 1 (1997): 31-36.

- "Pattan Munara: Minar or Mandir?" In Hari Smiriti: Studies in Art, Archaeology and Indology, Papers Presented in Memory of Dr. H. Sarkar, New Delhi: Kaveri Books, 2006.

- "Temples Along the Indus." Expedition, the Magazine of the University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology 38.3 (1996): 41-54. [.pdf available]

- "Temples of the Salt Range." In Religion, Ritual & Royalty, ed. N. K. Singhi and Rajendra Joshi, pp. 132-39. Jaipur: Rawat Publications, 1999.

- "Discoveries on the Indus." In The Ananda-Vana of Indian Art, ed. Naval Krishna and Manu Krishna, pp. 95-102. New Delhi: Indica.

In Press

- "Northwest India and the Punjab." In M. A. Dhaky , ed., Art and Architecture in India: North Indian Art and Architecture (Pre-Medieval).

- "The Problem of Platform Extensions at Kafirkot North," Ancient Pakistan.

- "Restoring Temples in the Kafirkots, N.W.F.P., and Katas, Panjab, to Discussions of the Origins of Nâgara." In M. S. Nagaraja Rao, ed. K. V. Ramesh Felicitation Volume.

- Temple Conservation and Transformation." In South Asian Archaeology 1999, ed. K.R. van Kooij and E.M. Raven, Leiden.

- "Archaeology at Kafirkot." In Catherine Jarrige and Vincent Lefevre, ed., South Asian Archaeology 2001, Paris: Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations, 2005, pp. 571-78.

- "Discovery of a New Temple on the Indus." Expedition, 42.1 (2000): 37-46. [.pdf available]

- "Temples of the Indus & the Salt Range, A Fresh Probe (1995-97)." The Pakistan Heritage Society Newsletter 1 (1998): 2-5.

- "The Discovery of Siva-Mahesvara Figure at Kafirkot." Lahore Museum Bulletin 9/2 (1996) [1998]: 51-56.

Farzand Masih

A student of Professor Abdhur Rehman's at the University of Peshawar, and team representative of the Department of Archaeology and Museums, Government of Pakistan, Farzand Masih travelled and worked with theSalt Range Project for several seasons while he prepared a doctoral dissertation, "Temples of the Salt Range and North and South Kafirkot: Detailed Analysis of Their Architecture and Decorative Designs" (Department of Archaeology, University of Peshawar, 2000). He is now an Assistant Professor of Archaeology, Department of History, University of the Punjab, Lahore. He has recently published parts of the dissertation:

- (with Shahbaz Khan) "Kallar - a Brick Temple." Journal of the Punjab University Historical Society, XXV (2000): 105-09.

- "Temples of the Salt Range and Kafir Kot: Ornamentation." Lahore Museum Bulletin XIII.2 (2000): 33-36.

- "An Extant Hindu Sahi Temple at Nandana." In Sohdra, History & Archaeology, by Abudl Aziz Farooq. Majlis-i-Sqafat Sohdra (Gujranwala), pp. 81-94.

- "Temples of North Kafir Kot." Indo Koko Kenkyu 22 (2001): 101-22.

- "A Seventh Century Temple at North Kafir Kot." Lahore Museum Bulletin XIV.1 (2001): 1-8.

- "Style of the Salt Range and Kafir Kot Temples in Pakistan: A Critical Analysis." Pakistan Vision III.1-2 (2002): 105-40.

last modified 3 March 2006

Michael W. Meister, mmeister@sas.upenn.edu