--validates JM Kenoyer's thesis of textile dyeing at Harappa on circular worker platforms;

--mañjiṣṭhā 'Indian madder, saffron/red dye for garments' is 1) archaeologically attested from Mohenjo-daro and 2) on an Indus Script inscription on an Anthromorph;

--reaffirms the possibility of vats used on circular worker platforms of Harappa to dye textiles with red/saffron madder dye and also possibly, indigo dye; the 'granary' or 'warehouse' may have been used to dry and store the dyed textiles.

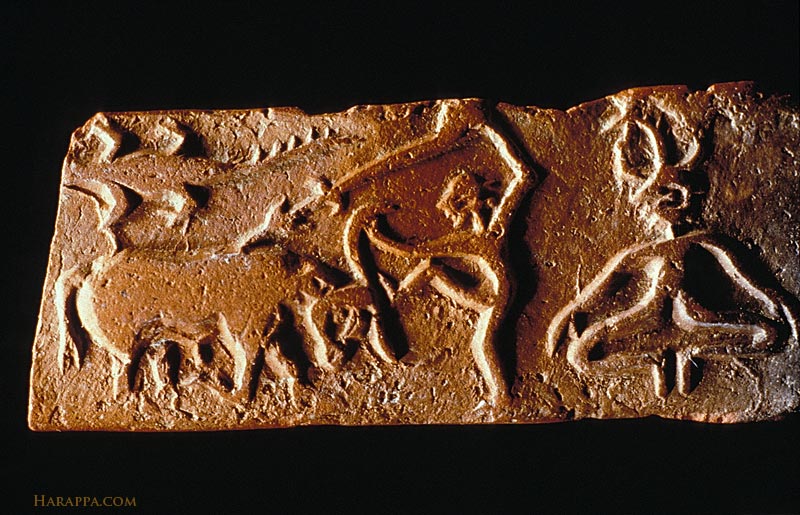

dhokra ‘decrepit woman with breasts hanging down’. Rebus: dhokra kamar 'artisan metalcaster using lost-wax technique'. The first hieroglyph on the text message on

Central pit of circular working platform indicates working with indigo? -- a hypothesis of JM Kenoyer.

The slides are sourced from, courtesy Dennys Frenez (2021):

https://www.academia.edu/48933836/THE_INDUS_CIVILIZATION_4_Integration_Era_The_Urban_Centres

This is an addendum to:

1. Brāhmī inscription on Indus Script anthropomorph reads: symbol of मांझीथा Majhīthā sadya 'member of mã̄jhī boat people assembly (community)' https://tinyurl.com/y85lflto

2. Indus Script solves the mysteries of stupa, circular platforms, archaeology identifies in Mohenjo-daro karaṇaśāle 'office of writers' https://tinyurl.com/s6qq46m

3. Dholavira tablet text message: koṭṭhāra 'warehouse' (of) kuṭila sal 'bronze workshop' PLUS dul khaṇḍa 'cast metal implements' https://tinyurl.com/ydhrb74c

The professional calling card used by metal merchants of Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization is overlayed with Brāhmī inscription (at a later date) by a goldsmith guild (mã̄jhī) working with madder, red saffron dye source for textiles. The reference to मांझीथा Majhīthā is significant and indicates the continuing tradition of dyeing textiles, from the days of Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization.

I submit that this decipherment of the anthropomorph mentioning मांझीथा Majhīthā ‘madder or red/saffron dye for textiles’ validates – in a later-day Brāhmī inscription, 1) the discovery by HARP team of possible indigo vats in the central pits of circular working platforms and 2) the hypothesis that the ‘granary’ of Harappa was indeed a “building for dyeing and drying fabrics” (JM Kenoyer).

माञ्जिष्ठं, क्ली, (मञ्जिष्ठया रक्तम् । “तेन रक्तंरागात् ।” ४ । २ । ४ । इत्यण् ।) लोहितवर्णः ।(यथा, बृहत्संहितायाम् । ३० । १२ ।“कल्माषबभ्रुकपिलाविचित्रमाञ्जिष्ठहरितशव-लाभाः ।”तद्वति, त्रि । इति हेमचन्द्रः ॥.—शब्दकल्पद्रुमः

माञ्जिष्ठ न०मञ्जिष्ठयारक्तमणे।१रक्तवर्णे२तद्वतित्रि०—वाचस्पत्यम्

mañjiṣṭhā f. ʻ the Indian madder (Rubia cordifolia and its dye) ʼ Kauś. [

Pa. mañjeṭṭhī -- f. ʻ madder ʼ, Pk. maṁjiṭṭhā -- f.; K. mazēṭh, dat. ˚ṭhi f. ʻ madder plant and dye (R. cordifolia or its substitute Geranium nepalense) ʼ; S. mañuṭha, maĩṭha f. ʻ madder ʼ; P. majīṭ(h), mãj˚ f. ʻ root of R. cordifolia ʼ; N. majiṭho ʻ R. cordifolia ʼ, A. mezāṭhi, maz˚, OAw. maṁjīṭha f.; H. mãjīṭ(h), maj˚ f. ʻ madder ʼ, G. majīṭh f., Ko. mañjūṭi; -- Si. madaṭa ʻ a small red berry ʼ, madaṭiya ʻ the tree with red wood Adenanthera pavonina (Leguminosae) ʼ; Md. madoři ʻ a weight ʼ.māñjiṣṭha -- .Addenda: mañjiṣṭhā -- [Cf. Drav. Kan. mañcaṭige,

mañjāḍi, mañjeṭṭi S. M. Katre]: S.kcch. majīṭh f. ʻ madder ʼ.(CDIAL 9718) K. mönz

mö̃z f. ʻ henna (a red -- orange dye), madder ʼ (< *mañjukā -- ).(CDIAL 9720) māñjiṣṭha ʻ bright red ʼ Gr̥S., ˚aka -- R. [

Madder. Rubia tinctorum, the rose madder or common madder or dyer's madder, is a herbaceous perennial plant species belonging to the bedstraw and coffee family Rubiaceae…

The roots can be over a metre long, up to 12 mm thick and the source of red dyes known as rose madder and Turkey red… It has been used since ancient times as a vegetable red dye for leather, wool, cotton and silk. For dye production, the roots are harvested after two years. The outer red layer gives the common variety of the dye, the inner yellow layer the refined variety. The dye is fixed to the cloth with help of a mordant, most commonly alum. Madder can be fermented for dyeing as well (Fleurs de garance)… The pulverised roots can be dissolved in sulfuric acid, which leaves a dye called garance (the French name for madder) after drying… Early evidence of dyeing comes from India where a piece of cotton dyed with madder has been recovered from the archaeological site at Mohenjo-daro (3rd millennium BCE). H. C. Bhardwaj & K. K. Jain (1982). "Indian dyes and dyeing industry during 18th–19th century" (PDF). Indian Journal of History of Science. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy. 17 (11): 70–81. ()

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rubia_tinctorum

Naturally dyed skeins made with madder root, Colonial Williamsburg, VA

Naturally dyed skeins made with madder root, Colonial Williamsburg, VA

“In India the earliest evidence of dyeing comes from Indus civilization (2300-1750 BCE) from where a piece of cotton at Mohenjo-daro, dyed with madder – a vegetable dye has been found. (Marshall, John, ed., Mohenjodaro and the Indus Civilization, Indological Book House, Delhi, 1973, p.32-33; reprint of 1931 edition. ” https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.722

Marshall reports that Messrs. Gulati and Turner opined that the purple dye on a scrap of cotton material found in Mohenjo-daro could be of the madder class.

This is further evaluated in an article by HC Bhardwaj and Kamal K. Jain in Indian Journal of History of Science, 17(1): 70-81. Bhardwaj and Kamal Jain note: "In fact, some of the dyes namely Indigo, Madder and Kermes were introduced all over the world by the Indians during very early periods. A red dye obtained either from Madder or Kermes was tactfully used by Alexander the Great, as probably the first important use of camouflage in war to win the battle against Persians. Similarly, Indigo was the dye selected for colouring the uniforms of British navy." (p. 70 ibid.)

This is the context in which the hypothesis of James Kenoyer becomes validated. Kenoyer found

“What was going on atop these baked-brick, circular platforms inside enclosed structures? At Harappan sites, platforms of closely fitted bricks laid on edge are usually associated with the use of water. Perhaps these circular platform installations were used to prepare indigo dye, which in South Asia traditionally involved fermentation in a darkened room. Sediment taken from between the bricks and in the center cavity of the HARP platform is being analyzed to test this hypothesis.” (Richard H. Meadow and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer, 2000, The Indus Valley Mystery, One of the world’s first great civilizations is still a puzzle, in: Scientific American, March/April 2000, pp.42-43; discoveringarchaeology.com)

https://www.harappa.com/slide/vs-area-section-block-i-house-ii-room-23-showing-brick-floor-dyeing-troughs

VS Area, Section A. Block I, House II: Room 23, showing brick floor with dyeing troughs

[Original 1931 caption] "House II. - Rooms 1 to 26, covering a rectangular area of 86 ft. 10 in. by 64 ft. 5 in. to the north of the building just described, appear originally to have belonged to one and the same house, which had two entrances opening into the main street on the east and another into Lane I on the north. At a subsequent date the building appears to have been divided into four separate dwellings. . .. Noteworthy features of this room are five conical pits or holes dug into the floor and lined with wedge-shaped bricks, apparently meant to hold the pointed bases of large storage jars, and what seems to have been a very narrow well in the S.E. corner. Room 2 has a small chamber screened off in its N.W. corner and a paved bath or floor for cleaning utensils in the other corner, with a covered drain to carry of waste water into the cesspit in front of Room I." [Marshall, Vol. I. p. 216]

https://www.harappa.com/slide/vs-area-section-block-i-house-ii-room-23-showing-brick-floor-dyeing-troughs

https://www.harappa.com/blog/dyers-workshop

In an article (2004) ‘Ancient Textiles of the Indus Valley Region, in Tana Bana: The woven soul of Pakistan, edited by Noorjehan Bilgrami, pp.18-31, Koel Publications, Karachi, Jonathan Mark Kenoyer notes: “The most common fibres used in the Indua Valley appear to have been cotton, but various types of wool and possibly jute or hemp fibres were also used. Most recently, the discovery of silk thread inside copper beads from the site of Harappa indicates that wild silk was also known to the ancient inhabitants of the region, though there is no evidence to suggest that it was woven into fabric…One of the most famous examples of a textile from the site of Mohenjo-Daro is seen on a small stone sculpture with a cloak thrown over the left shoulder. Often referred to as the ‘Priest-King’ this sculpture shows the use of circular designs comprised of circles, double circles and trefoils. When the sculpture was first discovered, the trefoils and circles were filled with red pigment and the background was filled with a dark pigment that may have originally been green or blue. The white color of the original stone would hve been visible in the form of the circle, resulting in a striking pattern made of green or blue with red and white designs. This type of patterning, using indigo, madder and bleached cotton, is still commonly used in the priting of ajrak block prints in modern Sindh, Gujarat and Rajasthan. Due to the lack of repetition in the design, the cloak worn by the ‘priest-king’ probably is not a block printed textile, but may have been made with large embroidered designs or by tie dyeing… ”

https://www.harappa.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Kenoyer2004%20IndusTextilesfinal.pdf

[quote] There is no hard and fast proof yet that indigo was an important dye during Indus times, but it is quite possible. Hobson-Jobson (1903) defines indigo as: "The plant Indigofera tinctoria, L. (N.O. Leguminosao), and the dark blue dye made from it. Greek [xxxx]. This word appears from Hippocrates to have been applied in his time to Pepper. It is also applied by Dioscorides to the mineral substance (a variety of the red oxide of iron) called Indian red (F. Adams, Appendix to Dunbar's LexiconLiddell & Scott call it "a dark blue dye, indigo." The dye was used in Egyptian mummy cloths (Wilkinson, Ancient Egypt, ed. 1878, ii. 163).]

The earliest reference Hobson-Jobson gives is "a.D. c. 60.–"Of that which is called [xxxx] one kind is produced spontaneously, being as it were a scum thrown out by the Indian reeds; but that used for dyeing is purple efflorescence which flots on the brazen cauldrons, which the craftsmen skim off and dry. That is deemed best which is blue in colour, succulent, and smooth to the touch. Dioscorides, v. cap. 107. (Henry Yule and A.C. Burnell, Hobson-Jobson, John Murray, 1903 [1994], p. 437).

Wikipedia defines indigo asa "Species of Indigofera were cultivated in India, East Asia and Egypt in antiquity. Pliny mentions India as the source of the dye, imported in small quantities via the Silk Road. The Greek term for the dye was Ἰνδικὸν φάρμακον ("Indian dye"), which, adopted to Latin as indicum and via Portuguese gave rise to the modern word indigo."

Gregory Possehl writes in one of the few references by an Indus scholar, "Indigo and Lathyrus odoratus, both legumes, the root nodules of which help in the natural fertilization of the soil, were once widely cultivated in the western region of the subcontinent. Their cultiuvation was stopped by the British and this adversely affected soil fertility (Harappan Civilization, p. 35).[unquote]https://www.harappa.com/blog/night-indigo

https://insa.nic.in/writereaddata/UpLoadedFiles/IJHS/Vol17_1_6_HCBhardwaj.pdf Full text embedded below:

![]() kuṭilika 'bent, curved' rebus: कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin); " sal 'splinter' rebus: sal'workshop'. Thus, together, 'bronze workshop'

kuṭilika 'bent, curved' rebus: कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin); " sal 'splinter' rebus: sal'workshop'. Thus, together, 'bronze workshop'

kaṇḍa 'arrow' rebus: khaṇḍa 'implements' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metalcasting'. Thus the pair of 'arrows' signify, cast metal implements.

karṇika 'rim of jar' rebus: karṇī 'supercargo, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale'; कर्णिक having a helm; a steersman (Monier-

Side B of the tablet:

Hieroglyph: dhokra ‘decrepit woman with breasts hanging down’. Rebus: dhokra kamar 'artisan metalcaster using lost-wax technique'. Ku. ḍokro, ḍokhro ʻ old man ʼ; B. ḍokrā ʻ old, decrepit ʼ, Or. ḍokarā; H. ḍokrā ʻ decrepit ʼ; G. ḍokɔ m. ʻ penis ʼ, ḍokrɔ m. ʻ old man ʼ, M. ḍokrā m. -- Kho. (Lor.) duk ʻ hunched up, hump of camel ʼ; K. ḍọ̆ku ʻ humpbacked ʼ perh. < *ḍōkka -- 2. Or. dhokaṛa ʻ decrepit, hanging down (of breasts) ʼ.(CDIAL 5567). M. ḍhẽg n. ʻ groin ʼ, ḍhẽgā m. ʻ buttock ʼ. M. dhõgā m. ʻ buttock ʼ. (CDIAL 5585). (The decrepit woman is ligatured to the hindpart of a bovine).

kāruvu ‘crocodile’ Rebus: khār ‘blacksmith’ (Kashmiri) PLUS dula 'pair' rebus; dul 'metal casting'. Thus, the pair of crocodiles signify metalcaster smith.

Heroglyph: Person with upraised arms: eraka 'upraised arm' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper'. Ka. eṟe to pour any liquids, cast (as metal); n. pouring; eṟacu, ercu to scoop, sprinkle, scatter, strew, sow; eṟaka, eraka any metal infusion; molten state, fusion. Tu. eraka molten, cast (as metal); eraguni to melt. Kur. ecchnā to dash a liquid out or over (by scooping, splashing, besprinkling). (DEDR 866).

kuṭilika 'bent, curved' rebus: कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin); " sal 'splinter' rebus: sal'workshop'. Thus, together, 'bronze workshop'

kuṭilika 'bent, curved' rebus: कुटिल kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin); " sal 'splinter' rebus: sal'workshop'. Thus, together, 'bronze workshop'

a royal tiger. (Telugu)

a royal tiger. (Telugu)