Itihāsa. Unhinging Śiva from the Indus Civilization -- Doris Srinivasan (1984)

Itihāsa. Aristotle on the Origin of the Jews in India -- Subhash Kak

Published 28th March 2017 |

This article is to try to make sense of a puzzling statement of Aristotle (384-322 BCE) that links Jews with India. This statement is recalled in a fragment by Aristotle’s pupil Clearchus who traveled widely and whose inscription on a tomb of a friend is preserved in the Afghan city of Ai-Khanoum.

The Jewish scholar Flavius Josephus (37 – 100 CE) quotes from Clearchus’s fragment in his Contra Apionem [Against Apion], which has Aristotle say: “Jews are derived from the Indian philosophers; they are named by the Indians Calami, and by the Syrians Judaei, and took their name from the country they inhabit, which is called Judea.” (Book I:22) [1]

I can think of two places that might have been the Calami of Aristotle. The first candidate is the famous port city of Kollam, in Kerala, which was well known to the Phoenicians and Romans, and the second is the ancient city of Kalyani or Kalyan, in Karnataka, which was to later become the capital of one branch of the Chalukya Empire. The second city, which has recently been renamed Basavakalyan, appears to be the older of the two.

The interaction between India and the West during the first millennium BCE is well known as in the mention in Old Testament of trade for ivory, apes and peacocks (1 Kings 10:22). There was thriving bilateral trade between India and Rome both through the overland caravan route and the southern sea route. By the time of Augustus 120 ships set sail every year from Myos Hormos to India. Pliny complains in Historia Naturae 12.41.84, “India, China and the Arabian Peninsula take one hundred million sesterces from our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us.”

India and the West had rich interaction in the second millennium BCE also. This was the time of the Mitanni of Syria, who worshiped Vedic gods. The Mitanni ruled northern Mesopotamia (including Syria) for about 300 years, starting 1600 BCE, out of their capital of Vasukhani. In a treaty between the Hittites and the Mitanni, Indic deities Mitra, Varuṇa, Indra, and Nāsatya (Aśvins) are invoked. Their chief festival was the celebration of viṣuva (solstice) very much like in India. It is not only the kings who had Sanskrit names; a large number of other Sanskrit names have also been unearthed in the records from the area.

The list of the Sanskrit names used in Syria and elsewhere was published by P. E. Dumont of the Johns Hopkins University, in the Journal of American Oriental Society in 1947, and one may see a summary of that in my own book chapter on Akhenaten, Sūrya, and the Ṛgveda, which is available here. [2] The names of the main kings are (with the standard Sanskrit form or meaning inside brackets): The first Mitanni king was Sutarna I (good Sun). He was followed by Baratarna I (Paratarṇa, great Sun); Paraśukṣatra (ruler with axe); Saustatar (Saukṣatra, son of Sukṣatra, the good ruler); Paratarṇa II; Artadama (Ṛtadhāman, abiding in cosmic law); Sutarṇa II; Tushratta (Daśaratha or Tveṣaratha, having ten or fast chariots); and finally Matiwazza (Mativāja, whose wealth is thought), during whose lifetime the Mitanni state became a vassal to Assyria.

It is most interesting that the Mitannis were connected by marriage across several generations to the Egyptian 18th dynasty to which Pharaoh Akhenaten (ruled 1352-1336 BCE according to the mainstream view) belonged. Akhenaten’s second wife was Tadukhipa (“khipa” from the Sanskrit “kṣipā,” night) and she became famous as the queen Kiya (short for Khipa). His first wife was the beautiful Nefertiti, whose bust is available in a museum in Berlin.

Akhenaten (“glory of the Aten”) changed his name to honour Aten (“One god” represented as the solar disk) in his sixth year of rule. Many see Akhenaten as the originator of monotheism by his banishment of all deities except for his chosen one. He has been seen as a precursor to the Old Testament prophets, and thus to the Abrahamic religions. Some Biblical scholars see his Hymn to Aten as the original Psalm 104 of the Old Testament [3].

‘Amehotep IV’ (Akhenaten), found in N. de G. Davies, The Rock Tombs of El Amarna, part VI, ‘The Egypt Exploration Fund’ (London, 1908).

The other possibility is that Akhenaten’s worship of Aten is derived from the Vedic system through the three generations of queens in his family that were from the Mitanni. There are parallels between his hymn and the Sūrya hymns of the Ṛgveda. For example, in both the Sun has absolute power over the lives of animals and men and it provides natural bounties while also residing in the heart of the poet. Note also that Agni is praised as Yahvah in the Ṛgveda 21 times, and Yahweh is the name of the highest divinity in the Old Testament.

If the Vedic element was important, as is perhaps reflected in the mysticism of the Egyptian Book of the Dead, the cult of the dead and resurrection remained the most important element of the Egyptian religion. This cult continues to form the cornerstone of the three Abrahamic faiths.

The Vedic presence via the Mitanni in Egypt and the Near East occurs several centuries before the exodus of the Jews. This presence is sure to have left its mark in various customs, traditions, and beliefs. It may be that this encounter explains uncanny similarities in mythology and ritual, such as circumambulation around a rock, the use of a rosary of 108 beads, (or the idea of 33 gods in pre-Abrahamic traditions). These practices are easily understandable within the Vedic system, whereas they are remembered as commandments to be believed without understanding in the Western faiths. [4]

Sigmund Freud in his essay, Moses and Monotheism (1937) proposes that Moses was an Egyptian linked to the court of Akhenaten. In defence of this proposal he argued that the Hebrew word for “Lord,” “Adonai,” becomes “Aten” when the letters are written in Egyptian. [5]

The memory of India’s interaction with Egypt persisted within the Indo-Iranian world. The Iranian scholar Al-Biruni (973-1048), speaking of chariots of war in his book Tarikh Al-Hind, mentions the Greek claim that they were the first to use them and insists they are wrong because the chariots were already invented by Aphrodisios the Hindu, when he ruled over Egypt, about 900 years after the deluge. [6] This reference, which cannot be literally true because of the sheer distance between the two regions, is significant for it preserves the memory of a “Hindu” (Indic-inspired) king of Egypt prior to the Greek state. The reference to the chariots of war of this king (Akhenaten) seems to remember the foreigner warlords Hyksos (literally, ruler of the foreign countries) who ruled Egypt during the Second Intermediate Period just before the New Kingdom to which Akhenaten belonged.

It is not surprising then that the iconic Shiva-Shakti Yantra of the Indian spiritual tradition is identical to the Star of David of the Jews. A picture of the Star of David from the Leningrad Codex with a date of 1008 in its colophon is presented for comparison.

But how could the Indic element be so far from India, in Syria and Egypt? Scholars have suggested that after catastrophic earthquakes, or a long drought that dried up the Sarasvati River around 1900 BCE, there was the abandonment of Harappan cities and great migrations away in all directions [7]. Within India, we see the focus of the Sindhu-Sarasvati culture shift eastwards. To the west, we see the Kassites, a somewhat shadowy aristocracy with Indic names and worshiping Surya and the Maruts, in Western Iran about 1800 BCE. They captured power in Babylon in 1600 BCE, which they were to rule for over 500 years. And then, of course, we have the long line of the Sanskritic Mitanni aristocracy of Syria that we have already spoken about.

Megasthenes (350-290 BCE), the ambassador of Seleucus I to the court of Chandragupta Maurya in Pataliputra appears to have been aware of the connections between the Indians and the Jews. In the third book of Indica, as available to the Church Father Clement of Alexandria (200 CE), he writes: “All that has been said regarding nature by the ancients is asserted also by philosophers out of Greece, on the one part in India by the Brachmanes, and on the other in Syria by the people called the Jews.” [8]

A thousand years later, the memory of a special link between the Jews and India persisted. Al-Biruni mentions on page 206, vol. 1 of Alberuni’s India by Edward Sachau, that no foreigners excepting the Jews were permitted to enter Kashmir during the period it was under attack by Muslims.

India has its own Jewish communities that are found principally in South India; the oldest of these is that of the Cochin Jews. They believe they are the descendants of traders from Judea who arrived in 562 BCE, with others coming as exiles in 70 CE after the destruction of the Second Temple [9]. It appears that there was migration of communities in both directions.

Bibliography

- Flavius Josephus, Against Apion, Project Gutenberg: http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2849

- Subhash Kak, ‘Akhenaten, Surya, and the Rgveda’, In G.C. Pande (ed.), A Golden Chain of Civilizations: Indic, Iranic, Semitic, and Hellenic up to C. 600 BCE, Munshiram Manoharlal, 2007. http://www.ece.lsu.edu/kak/akhena.pdf

- Dominic Montserrat, Akhenaten: History, Fantasy and Ancient Egypt, Routledge, 2002.

- Subhash Kak, The Wishing Tree, Aditya Prakashan, New Delhi, 2015.

- Sigmund Freud, Moses and Monotheism, The Hogarth Press, 1939.

- Al-Biruni, Tarikh Al-Hind, E.C. Sachau trans., Alberuni’s India, Kegan Paul, London, 1910.

- G. Feuerstein, S. Kak, and D. Frawley, In Search of the Cradle of Civilization, Quest Books, 2001.

- J.W. McCrindle, Ancient India As Described By Megasthenes And Arrian, Trübner & Co, London, 1877.

- Peter Schäfer, The History of the Jews in Antiquity, Routledge, 1995.

YouTube video on ai-Khanoum: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5tka9TFyWIw

Subhash Kak is Regents Professor and a previous Head of the Computer Science Department at Oklahoma State University, who has made contributions to cryptography, artificial neural networks, and quantum information.

Kak is also notable for his Indological publications on the history of science, the philosophy of science, ancient astronomy, and the history of mathematics. Alan Sokal labeled Kak “one of the leading intellectual luminaries of the Hindu-nationalist diaspora”.

Itihāsa. The Buried Mysteries of Angkor Wat revealed by Lidar Survey

Huge Hidden Cities Found Near Angkor Wat Under the Forest - YouTube (2:01)

Laser technology reveals cities concealed under the earth which would have made up the world’s largest empire in 12th century. Source: https://www.theguardian.com/world/201... Credit: Dr Damian Evans/Journal of Archaeological Science

(225) The Buried Mysteries Of Angkor Wat | The City Of God Kings | Timeline - YouTube (49:33)

Lost Worlds investigates the very latest archaeological finds at three remote and hugely significant sites - Angkor Wat, Troy and Persepolis. Lost Worlds travels to each site and through high-end computer graphics, lavish re-enactment and the latest archaeological evidence brings them to stunning televisual life. From the 900-year-old remains of Angkor Wat in the Cambodian jungle the staggering City of the God Kings is recreated. From Project Troia, in North West Turkey, the location of the biggest archaeological expedition ever mounted the lost city is stunningly visualised and finally from Persepolis the city and the great Persian Empire are brought to life.

Revealed: Cambodia's vast medieval cities hidden beneath the jungle

Exclusive: Laser technology reveals cities concealed under the earth which would have made up the world’s largest empire in 12th century

Archaeologists in Cambodia have found multiple, previously undocumented medieval cities not far from the ancient temple city of Angkor Wat, the Guardian can reveal, in groundbreaking discoveries that promise to upend key assumptions about south-east Asia’s history.

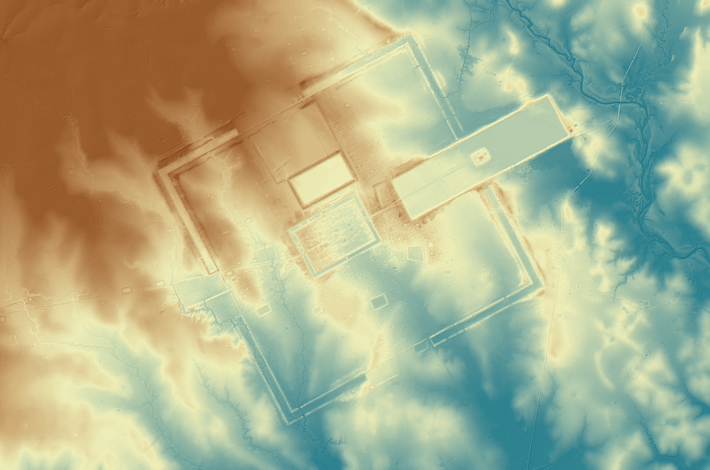

The Australian archaeologist Dr Damian Evans, whose findings will be published in the Journal of Archaeological Science on Monday, will announce that cutting-edge airborne laser scanning technology has revealed multiple cities between 900 and 1,400 years old beneath the tropical forest floor, some of which rival the size of Cambodia’s capital, Phnom Penh.

Some experts believe that the recently analysed data – captured in 2015 during the most extensive airborne study ever undertaken by an archaeological project, covering 734 sq miles (1,901 sq km) – shows that the colossal, densely populated cities would have constituted the largest empire on earth at the time of its peak in the 12th century.

Evans said: “We have entire cities discovered beneath the forest that no one knew were there – at Preah Khan of Kompong Svay and, it turns out, we uncovered only a part of Mahendraparvata on Phnom Kulen [in the 2012 survey] … this time we got the whole deal and it’s big, the size of Phnom Penh big.”

A research fellow at Siem Reap’s École Française d’Extrême-Orient (EFEO) and the architect of the Cambodian Archaeological Lidar Initiative (Cali), Evans will speak at the Royal Geographic Society in London about the findings on Monday.

Evans obtained European Research Council (ERC) funding for the project, based on the success of his first lidar (light detection and ranging) survey in Cambodia in 2012. That uncovered a complex urban landscape connecting medieval temple-cities, such as Beng Mealea and Koh Ker, to Angkor, and confirmed what archaeologists had long suspected, that there was a city beneath Mount Kulen. It was not until the results of the significantly larger 2015 survey were analysed that the size of the city was apparent.

That survey uncovered an array of discoveries, including elaborate water systems that were built hundreds of years before historians believed the technology existed. The findings are expected to challenge theories on how the Khmer empire developed, dominated the region, and declined around the 15th century, and the role of climate change and water management in that process.

“Our coverage of the post-Angkorian capitals also provides some fascinating new insights on the ‘collapse’ of Angkor,” Evans said. “There’s an idea that somehow the Thais invaded and everyone fled down south – that didn’t happen, there are no cities [revealed by the aerial survey] that they fled to. It calls into question the whole notion of an Angkorian collapse.”

The Angkor temple ruins, which sprawl across the Unesco-protected Angkor archaeological park, are the country’s top tourist destination, with the main temple-city, Angkor Wat, appearing on the Cambodian national flag. Considered the most extensive urban settlement of pre-industrial times, and boasting a highly sophisticated water management system, Angkor’s supposed decline has long occupied archaeologists.

The new cities were found by firing lasers to the ground from a helicopter to produce extremely detailed imagery of the Earth’s surface. Evans said the airborne laser scanners had also identified large numbers of mysterious geometric patterns formed from earthen embankments, which could have been gardens.

Experts in the archaeological world agree these are the most significant archaeological discoveries in recent years.

Michael Coe, emeritus professor of anthropology at Yale University and one of the world’s pre-eminent archaeologists, specialises in Angkor and the Khmer civilisation.

“I think that these airborne laser discoveries mark the greatest advance in the past 50 or even 100 years of our knowledge of Angkorian civilisation,” he said from Long Island in the US.

There is an undiscovered city beneath Mount Kulen. Photograph: Terence Carter

“I saw Angkor for the first time in 1954, when I wondered at the magnificent temples, but there was nothing to tell us who had lived in the city, where they had lived, and how such an amazing culture was supported. To a visitor, Angkor was nothing but temples and rice paddies.”

Charles Higham, research professor at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand, and the leading archaeologist of mainland south-east Asia, said it was the most exciting paper he could recall reading

“I have been to all the sites described and at a stroke, they spring into life … it is as if a bright light has been switched on to illuminate the previous dark veil that covered these great sites,” Higham said. “Personally, it is wonderful to be alive as these new discoveries are being made. Emotionally, I am stunned. Intellectually, I am stimulated.”

David Chandler, emeritus professor at Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, the foremost expert on Cambodian history and the author of several books and articles on the subject, said the work was thrilling and credited Evans and his colleagues with “rewriting history”.

Chandler said he believed it would open up a series of perspectives that would help people know more about Angkorian civilisation, and how it flourished and eventually collapsed.

“It will take time for their game-changing findings to drift into guide books, tour guides, and published histories,” Chandler said. “But their success at putting hundreds of nameless, ordinary, Khmer-speaking people back into Cambodia’s past is a giant step for anyone trying to deal with Cambodian history.”

David Kyle, an archaeologist and ecological anthropologist has conducted projects at Phnom Kulen, the location of the biggest findings, the massive city of Mahendraparvata, the size of Phnom Penh, beneath the forest floor.

He said the “survey results have revolutionised our understanding and approaches. It’s impossible not to be excited. It facilitates a paradigm shift in our comprehension of the complexity, size and the questions we can address.”

While the 2012 survey identified a sprawling, highly urbanised landscape at Greater Angkor, including rather “spectacularly” in the “downtown” area of the temple-city of Angkor Wat, the 2015 project has revealed a similar pattern of equally intense urbanism at remote archaeological ruins, including pre- and post-Angkorian sites.

Dr Peter Sharrock, who is on the south-east Asian board at London University’s School of Oriental and African Studies and has a decades-long connection to Cambodia, said the findings showed “clear data for the first time of dense populations settled in and around all ancient Khmer temples”.

“This urban and rural landscape, linked by road and canal networks, now seems to have constituted the largest empire on earth in the 12th century,” Sharrock said.

Evans, whose domain is an air-conditioned room full of computers at the French archaeological centre in Siem Reap, rather than dirt trenches at far-flung digs, is modest about his achievements and quick to credit his colleagues on the Cali project.

He said he believed the discoveries would completely upend many assumptions about the Khmer empire. He also hoped it would bring the study of people back into the picture.

Coe, who has been to many of the places covered by the survey and has seen the imagery, said that while the 2012 survey of Phnom Kulen demonstrated what the technology could do – “it could look through the dense jungle covering these hills and reveal an unexpected city which predated Angkor itself” – the 2015 survey took this into new dimensions.

This view was shared by Dr Mitch Hendrickson, the director of the industries of Angkor project and assistant professor in the department of anthropology at the University of Illinois. He said the initial survey had been “an incredible leap forward” in archaeologists’ ability to see everything for the first time and had been “a major game-changer” in understanding how the Angkorian Khmer people built, modified and lived in their cities. But he was “stunned” by the second survey.

“The results for Preah Khan of Kompong Svay are truly remarkable and are arguably the jewel in the crown of this mission. The lidar shows us that there was much, much more,” Hendrickson said, referencing a full-blown community layout that was previously unknown. “It’s both humbling and exciting. There are so many fantastic new discoveries.”

“We knew that Preah Khan of Kompong Svay was significant before the lidar – it’s the largest complex ever built during the Angkorian period at 22 sq km, it is connected to Angkor directly by a major road fitted with infrastructure, and likely played a role in facilitating iron supply to the capital.

“The new results suggest that it may have been more important than many temples built in Angkor and that it had a decent-sized population supporting it.”

Dr Martin Polkinghorne, a research fellow in the department of archaeology at Adelaide’s Flinders University who is conducting a joint research project on Longvek and Oudong, the post-Angkorian capitals, said his team would use the data during excavations scheduled until 2019 to understand the cities.

“The decline of Angkor is among the most significant events in the history of south-east Asia, but we do not have a precise date for the event,” Polkinghorne said. “By using lidar to guide excavations on the capitals of Cambodia that followed we can determine when the kings of Angkor moved south and clarify the end of Angkor.

“Cambodia after Angkor is customarily understood in terms of loss, retreat and absence; a dark age,” he said. “Yet, Cambodia was alive with activity after Angkor. South-east Asia was the hub of international trade between east and west. Using the lidar at Longvek and Oudong in combination with conventional archaeology we will reveal the dark age as equally rich, complex and diverse.”

What is a lidar survey?

An airborne laser scanner (ALS) is mounted to a helicopter skid pad. Flying with pre-determined guidelines, including altitude, flight path and airspeed, the ALS pulses the terrain with more than 16 laser beams per square metre during flights. The time the laser pulse takes to return to the sensor determines the elevation of each individual data point.

The data downloaded from the ALS is calibrated and creates a 3D model of the information captured during the flights. In order to negate tree foliage and manmade obstacles from the data, any sudden and radical changes in ground height are mapped out, with technicians who have models of the terrain fine-tuning the thresholds in processing these data points. Once completed, the final 3D model is handed over to the archaeologists for analysis, which can take months to process into maps.

Archaeologists have found a monumental structure buried under the sands of Petra, according to a new study that drew on satellite imagery to scan the ancient city.

Satellite surveys of the city revealed a massive platform, 184ft by 161ft, with an interior platform that was paved with flagstones, lined with columns on one side and with a gigantic staircase descending to the east. A smaller structure, 28ft by 28ft, topped the interior platform and opened to the staircase. Pottery found near the structure suggests the structure could be more than 2,150 years old.

“This monumental platform has no parallels at Petra or in its hinterlands at present,” the researchers wrote, noting that the structure, strangely, is near the city center but “hidden” and hard to reach.

“To my knowledge, we don’t have anything quite like this at Petra,” said Christopher Tuttle, an archaeologist who has worked at Petra for about 15 years and a co-author of the paper.

“I knew something was there and other archaeologists – who have worked in Petra for the last, God knows, 100 years at least – I know at least one other had noticed something there,” he said. But the structure’s sides resembled terrace walls common to the city, he noted: “I don’t think anybody paid much attention to them.”

Tuttle collaborated on the research with Sarah Parcak, a self-described “space archaeologist” from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who used satellites to survey the site.

Parcak said that she begins surveys “quite skeptical” of what they might find – they are working on sites in northern Africa, North America, Europe and elsewhere – and that she was surprised to find the monument “turned out to be something significant”.

“Petra is a massive site, and we chose the name for our article [‘Hiding in plain sight’] precisely because, even though this is less than a kilometer south of the main city, previous surveys had missed it,” she said.

Tuttle and a team took subsequent trips to measure and examine the site from the ground. There they found scattered pottery, the oldest of which suggests the site could date back to the time of Petra’s founding. “We’re always very cautious on this,” Tuttle said, “but the oldest pottery can be dated back relatively securely to about 150BC.”

Petra was built by the Nabateans in what is now southern Jordan, while the civilization was amassing great wealth trading with its Greek and Persian contemporaries around 150BC. The city was eventually subsumed by the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman empires, but its ruins remain famous for the work of its founders, who carved spectacular facades into cliffs and canyons. It was abandoned around the seventh century, and rediscovered by Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt in 1812.

Along with the oldest Nabatean pottery, they found fragments that had been imported from the Hellenistic cultures who traded with Petra, as well as pottery of the eras when the Roman and the Byzantine empires took the city under their guard.

In the mountains, valleys and canyons surrounding Petra, Tuttle said, “there’s tons of small cultic shrines and platforms and these things, but nothing on this scale”. He said these sites, including a large, open plateau known as the Monastery and probably “used for various cultic displays or political activities”, are the closest parallel to the newly discovered edifice. “To be honest, we don’t know a whole lot about it.”

Those sites suggest that the structure was used for “some kind of massive display function”, he said. Unlike those other sites, however, the giant staircase does not face the city center of Petra, which Tuttle called a “fascinating” peculiarity.

“We don’t understand what the purpose [of visible shrines], because the Nabateans didn’t leave any written documents to tell us,” he said, adding: “But I find it interesting that such a monumental feature doesn’t have a visible relationship to the city.”

Nabatean shrines around Petra offer mixed clues about the ancient people’s practices. Like other Semitic cultures of the day, the Nabateans used an indirect, “aniconic” style to indirectly represent their divinities: carved blocks, stelae and niches. Sometimes there will be “an empty niche, just a carving in the wall, which the empty space itself can be representative or they would’ve had portable images”, Tuttle said.

But because they were in near constant trade with other cultures of the Mediterranean, the Nabateans also adopted figural representations. “Nabatean gods depicted as parallels to Zeus or Hermes or Aphrodite, and those kinds of things,” he said.

The researchers published their work in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. They said that while they have no plans at this time to excavate the site, they hope they will have the chance to work there in the future.

Parcak said that she expects “some pretty amazing discoveries over the next year” using satellites and sophisticated new techniques in south-east Asia “and other densely forested/rainforest areas”. A surveying technology called Lidar, for instance, has uncovered sites in remote forests in Central America.

“This technology is not about what you find – but how you can think about things like settlement scale and ancient human-environment interactions more broadly,” she added. “What happens when you can truly map the near-surface buried features for an entire site? I’m excited, but we need to think about the implications of having all this technology at our fingertips so we can use it responsibly.”

Archaeologists discover massive Petra monument that could be 2,150 years old

This article is more than 4 years oldBuried platform measuring 184ft by 161ft ‘has no parallels’ at the ancient city and was discovered using satellite imagery to scan the surrounding land

Alan Yuhas 9 June 2016

A facade at Petra, where a new monumental structure has been found at the city built by Nabateans more than 2,000 years ago. Photograph: Martin Keene/PAArchaeologists have found a monumental structure buried under the sands of Petra, according to a new study that drew on satellite imagery to scan the ancient city.

Satellite surveys of the city revealed a massive platform, 184ft by 161ft, with an interior platform that was paved with flagstones, lined with columns on one side and with a gigantic staircase descending to the east. A smaller structure, 28ft by 28ft, topped the interior platform and opened to the staircase. Pottery found near the structure suggests the structure could be more than 2,150 years old.

“This monumental platform has no parallels at Petra or in its hinterlands at present,” the researchers wrote, noting that the structure, strangely, is near the city center but “hidden” and hard to reach.

“To my knowledge, we don’t have anything quite like this at Petra,” said Christopher Tuttle, an archaeologist who has worked at Petra for about 15 years and a co-author of the paper.

“I knew something was there and other archaeologists – who have worked in Petra for the last, God knows, 100 years at least – I know at least one other had noticed something there,” he said. But the structure’s sides resembled terrace walls common to the city, he noted: “I don’t think anybody paid much attention to them.”

Tuttle collaborated on the research with Sarah Parcak, a self-described “space archaeologist” from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who used satellites to survey the site.

Parcak said that she begins surveys “quite skeptical” of what they might find – they are working on sites in northern Africa, North America, Europe and elsewhere – and that she was surprised to find the monument “turned out to be something significant”.

“Petra is a massive site, and we chose the name for our article [‘Hiding in plain sight’] precisely because, even though this is less than a kilometer south of the main city, previous surveys had missed it,” she said.

Overview of the monumental platform, looking south-east. Jabal an-Nmayr is is indicated by the left-facing arrow, and the slope of ‘South Ridge’ with agricultural terracing by the down-facing arrow. Photograph: G al FaqeerIn the mountains, valleys and canyons surrounding Petra, Tuttle said, “there’s tons of small cultic shrines and platforms and these things, but nothing on this scale”. He said these sites, including a large, open plateau known as the Monastery and probably “used for various cultic displays or political activities”, are the closest parallel to the newly discovered edifice. “To be honest, we don’t know a whole lot about it.”

Those sites suggest that the structure was used for “some kind of massive display function”, he said. Unlike those other sites, however, the giant staircase does not face the city center of Petra, which Tuttle called a “fascinating” peculiarity.

“We don’t understand what the purpose [of visible shrines], because the Nabateans didn’t leave any written documents to tell us,” he said, adding: “But I find it interesting that such a monumental feature doesn’t have a visible relationship to the city.”

Nabatean shrines around Petra offer mixed clues about the ancient people’s practices. Like other Semitic cultures of the day, the Nabateans used an indirect, “aniconic” style to indirectly represent their divinities: carved blocks, stelae and niches. Sometimes there will be “an empty niche, just a carving in the wall, which the empty space itself can be representative or they would’ve had portable images”, Tuttle said.

But because they were in near constant trade with other cultures of the Mediterranean, the Nabateans also adopted figural representations. “Nabatean gods depicted as parallels to Zeus or Hermes or Aphrodite, and those kinds of things,” he said.

The researchers published their work in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. They said that while they have no plans at this time to excavate the site, they hope they will have the chance to work there in the future.

Parcak said that she expects “some pretty amazing discoveries over the next year” using satellites and sophisticated new techniques in south-east Asia “and other densely forested/rainforest areas”. A surveying technology called Lidar, for instance, has uncovered sites in remote forests in Central America.

“This technology is not about what you find – but how you can think about things like settlement scale and ancient human-environment interactions more broadly,” she added. “What happens when you can truly map the near-surface buried features for an entire site? I’m excited, but we need to think about the implications of having all this technology at our fingertips so we can use it responsibly.”

Petra was built by the Nabateans in what is now southern Jordan, while the civilization was amassing great wealth trading with its Greek and Persian contemporaries around 150BC. The city was eventually subsumed by the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman empires, but its ruins remain famous for the work of its founders, who carved spectacular facades into cliffs and canyons. It was abandoned around the seventh century, and rediscovered by Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt in 1812.Tuttle and a team took subsequent trips to measure and examine the site from the ground. There they found scattered pottery, the oldest of which suggests the site could date back to the time of Petra’s founding. “We’re always very cautious on this,” Tuttle said, “but the oldest pottery can be dated back relatively securely to about 150BC.”

Along with the oldest Nabatean pottery, they found fragments that had been imported from the Hellenistic cultures who traded with Petra, as well as pottery of the eras when the Roman and the Byzantine empires took the city under their guard.

Buried platform measuring 184ft by 161ft ‘has no parallels’ at the ancient city and was discovered using satellite imagery to scan the surrounding land

Alan Yuhas 9 June 2016

Archaeologists have found a monumental structure buried under the sands of Petra, according to a new study that drew on satellite imagery to scan the ancient city.

Satellite surveys of the city revealed a massive platform, 184ft by 161ft, with an interior platform that was paved with flagstones, lined with columns on one side and with a gigantic staircase descending to the east. A smaller structure, 28ft by 28ft, topped the interior platform and opened to the staircase. Pottery found near the structure suggests the structure could be more than 2,150 years old.

“This monumental platform has no parallels at Petra or in its hinterlands at present,” the researchers wrote, noting that the structure, strangely, is near the city center but “hidden” and hard to reach.

“To my knowledge, we don’t have anything quite like this at Petra,” said Christopher Tuttle, an archaeologist who has worked at Petra for about 15 years and a co-author of the paper.

“I knew something was there and other archaeologists – who have worked in Petra for the last, God knows, 100 years at least – I know at least one other had noticed something there,” he said. But the structure’s sides resembled terrace walls common to the city, he noted: “I don’t think anybody paid much attention to them.”

Tuttle collaborated on the research with Sarah Parcak, a self-described “space archaeologist” from the University of Alabama at Birmingham, who used satellites to survey the site.

Parcak said that she begins surveys “quite skeptical” of what they might find – they are working on sites in northern Africa, North America, Europe and elsewhere – and that she was surprised to find the monument “turned out to be something significant”.

“Petra is a massive site, and we chose the name for our article [‘Hiding in plain sight’] precisely because, even though this is less than a kilometer south of the main city, previous surveys had missed it,” she said.

In the mountains, valleys and canyons surrounding Petra, Tuttle said, “there’s tons of small cultic shrines and platforms and these things, but nothing on this scale”. He said these sites, including a large, open plateau known as the Monastery and probably “used for various cultic displays or political activities”, are the closest parallel to the newly discovered edifice. “To be honest, we don’t know a whole lot about it.”

Those sites suggest that the structure was used for “some kind of massive display function”, he said. Unlike those other sites, however, the giant staircase does not face the city center of Petra, which Tuttle called a “fascinating” peculiarity.

“We don’t understand what the purpose [of visible shrines], because the Nabateans didn’t leave any written documents to tell us,” he said, adding: “But I find it interesting that such a monumental feature doesn’t have a visible relationship to the city.”

Nabatean shrines around Petra offer mixed clues about the ancient people’s practices. Like other Semitic cultures of the day, the Nabateans used an indirect, “aniconic” style to indirectly represent their divinities: carved blocks, stelae and niches. Sometimes there will be “an empty niche, just a carving in the wall, which the empty space itself can be representative or they would’ve had portable images”, Tuttle said.

But because they were in near constant trade with other cultures of the Mediterranean, the Nabateans also adopted figural representations. “Nabatean gods depicted as parallels to Zeus or Hermes or Aphrodite, and those kinds of things,” he said.

The researchers published their work in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. They said that while they have no plans at this time to excavate the site, they hope they will have the chance to work there in the future.

Parcak said that she expects “some pretty amazing discoveries over the next year” using satellites and sophisticated new techniques in south-east Asia “and other densely forested/rainforest areas”. A surveying technology called Lidar, for instance, has uncovered sites in remote forests in Central America.

“This technology is not about what you find – but how you can think about things like settlement scale and ancient human-environment interactions more broadly,” she added. “What happens when you can truly map the near-surface buried features for an entire site? I’m excited, but we need to think about the implications of having all this technology at our fingertips so we can use it responsibly.”

Petra was built by the Nabateans in what is now southern Jordan, while the civilization was amassing great wealth trading with its Greek and Persian contemporaries around 150BC. The city was eventually subsumed by the Roman, Byzantine and Ottoman empires, but its ruins remain famous for the work of its founders, who carved spectacular facades into cliffs and canyons. It was abandoned around the seventh century, and rediscovered by Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt in 1812.Tuttle and a team took subsequent trips to measure and examine the site from the ground. There they found scattered pottery, the oldest of which suggests the site could date back to the time of Petra’s founding. “We’re always very cautious on this,” Tuttle said, “but the oldest pottery can be dated back relatively securely to about 150BC.”

Along with the oldest Nabatean pottery, they found fragments that had been imported from the Hellenistic cultures who traded with Petra, as well as pottery of the eras when the Roman and the Byzantine empires took the city under their guard.

Laser technology reveals lost city around Angkor Wat

Airborne laser technology has uncovered a network of roads and canals, illustrating the remains of a bustling ancient city linking Cambodia's famed Angkor Wat temples complex.

The discovery was announced late on Monday in a peer-reviewed paper released early by the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal. The laser scanning revealed a previously undocumented formal urban planned landscape integrating the 1,200-year-old temples.

The Angkor temple complex, Cambodia's top tourist destination and one of Asia's most famous landmarks, was constructed in the 12th century. Angkor Wat is a point of deep pride for Cambodians, appearing on the national flag, and was named a Unesco world heritage site.

"No one had ever mapped the city in any kind of detail before, and so it was a real revelation to see the city revealed in such clarity," University of Sydney archaeologist Damian Evans, the study's lead author, said by phone from Cambodia. "It's really remarkable to see these traces of human activity still inscribed into the forest floor many, many centuries after the city ceased to function and was overgrown."Archaeologists had long suspected that the city of Mahendraparvata lay hidden beneath a canopy of dense vegetation atop Phnom Kulen mountain in Siem Reap province. But the airborne lasers produced the first detailed map of a vast cityscape, including highways and previously undiscovered temples.

The technology, known as lidar, works by firing laser pulses from an aircraft to the ground and measuring the distance to create a detailed, three-dimensional map of the area. It is a useful tool for archaeologists because the lasers can penetrate dense vegetation and cover swaths of ground far faster than they could be analysed on foot. Lidar has been used to explore other archaeological sites, such as Stonehenge.

In April 2012, researchers loaded the equipment on to a helicopter, which spent days crisscrossing the dense forests from 800 metres above the ground. A team of Australian and French archaeologists then confirmed the findings with an expedition on foot through the jungle.

Archaeologists had already spent years doing ground research to map a 3.5 sq mile section of the city's downtown area. But the lidar revealed the section was much bigger – at least 14 sq miles – and more heavily populated than once believed.

"The real revelation is to find that the downtown area is densely inhabited, formally-planned and bigger than previously thought," Evans said. "To see the extent of things we missed before has completely changed our understanding of how these cities were structured."

Researchers do not yet know why the civilisation at Mahendraparvata collapsed. But Evans said one current theory is that possible problems with the city's water management system may have driven people out.

The next step for researchers involves excavating the site, which Evans hopes will reveal clues about how many people once lived in the city.

Angkor, Cambodia, 2015

January/February 2021

Thiruvathirai: The Dance Of Shiva At Every Level byAravindan Neelakandan

Ancient tradition distinguishes between jyautiṣiká 'astrologer' (Pāṇini); निमित्तज्ञः 'knower of omens'; this clue resolves absurd dates posited by astronomers

-- Resolving the absurdity of three dates for Mahabharata war derived by astronomy buffs: 1478 BCE, 3067 BCE, 5376 BCE

A jyautiṣiká जौतिषिक is an astronomer who documents celestial events.

A निमित्तज्ञः nimittajna is an interpreter of omens.

I submit that MBh references related to celestial events should be clearly distinguished between the observations of a jyautiṣiká and of a निमित्तज्ञः । Thus, the insights of a निमित्तज्ञः related to Arundhati (a binary star with Vasiṣṭa) should be distinguished from the observation of a jyautiṣiká who observes and records a celestial event.

Similarly, the meaning of the word 'graha' should be interpreted context. Graha is a word which means both 'planet' and 'comet'. Text of MBh should be carefully interpreted to determine the intended planetary or comet motion on the celestial sky.

I have appended a detailed explanatory note of Dr. Jayasree Saranathan which should help the astronomy-club buffs to distinguish betwen the observations of a jyautiṣiká and of a निमित्तज्ञः । while determining the dates of contemporary events recorded in the text of MBh.

Mbh 6-108-3 sacred-texts.com/hin/mbs/mbs061

3 निमित्तानि निमित्तज्ञः सर्वतॊ वीक्ष्य वीर्यवान

परतपन्तम अनीकानि दरॊणः पुत्रम अभाषत

Drona is called निमित्तज्ञः 'astrologer, who knows the meaning of omens'.

Only one of these dates can be right.

One thing is clear. Mahabharata is the most accurately dated Itihasa in the history of human civilization. With over 200 celestial observations discussed and recorded in the Great Epic, the challenge is to make a clear distinction between 'astrological omens' and contemporary 'astronomical observations'. The tradition is succinctly recorded by Aryabhata:

Āryabhaṭīya emphatically records the beginning of Kaliyuga at 3102 BCE in his Āryabhaṭīya in an autobiographical context, citing his age:

10. When three yugapādas and sixty times sixty years had elapsed (from the beginning of the yuga) then twenty-three years of my life had passed.

“If Āryabhaṭa began the Kaliyuga at 3102 BCE as later astronomers did, and if his fourth yugapāda began with the beginning of the Kaliyuga, we arrive at the date 499 CE. It is natural to take this as the date of composition of the treatise. “ (The Āryabhaṭīya of Āryabhaṭa—an Ancient Indian work on Mathematics and Astronomy, tr. By Walter Eugene Clark, Univ. of Chicago Press, Illinois, 1930 (pp.54-55)

Source: https://archive.org/stream/The_Aryabhatiya_of_Aryabhata_Clark_1930#page/n3/mode/2up

Kannada and Oriya lexicons provide a distinction between nimitta and upādāna, 'instrumental cause' and 'material cause':

I submit that the observation of Āryabhaṭa should be the fulcrum around which the differing interpretations of astronomy-buffs should be resolved. The astronomy-buffs should agree upon the categorisation of textual references as either nimittamātram or based on ज्योतिषं or observations on contemporary celestial events.

ज्योतिषं, क्ली, (ज्योतिः सूर्य्यादीनां ग्रहाणां गत्या-दिकं प्रतिपाद्यतया अस्त्यस्येति अच् ।) वेदाङ्ग-शास्त्रविशेषः । तत् ग्रहणादिगणनशास्त्रम् ।इत्यमरटीकायां भरतः ॥“पञ्चम्कन्धमिदं शास्त्रं होरागणितसंहिता ।केरलिः शकुनञ्चैव -- ॥”इति प्रश्नरत्नटीका ॥ * ॥अस्य सम्बन्धादि यथा, --“अस्य शास्त्रस्य सम्बन्धो वेदाङ्गमिति चोदितः ।अभिधेयञ्च जगतां शुभाशुभनिरूपणम् ॥इज्याध्ययनसंक्रान्तिग्रहषोडशकर्म्मणाम् ।प्रयोजनञ्च विज्ञेयं तत्तत्कालविनिर्णयः ॥”इति नारदीयम् ॥ * ॥अस्याध्ययनं द्बिजैः कर्त्तव्यम् । यथा, --“सिद्धान्तसंहिताहोरारूपस्कन्धत्रयात्मकम् ।वेदस्य निर्म्मलं चक्षुर्ज्योतिःशास्त्रमकल्मषम् ॥विनैतदखिलं श्रौतं स्मार्त्तं कर्म्म न सिध्यति ।तस्माज्जगद्धितायेदं ब्रह्मणा निर्म्मितं पुरा ॥अतएव द्विजैरेतदध्येतव्यं प्रयत्नतः ॥”इति नारदः ॥ * ॥शूद्रस्य पाठनिषेधो यथा, --“स्नेहाल्लोभाच्च मोहाच्च यो विप्रोऽज्ञानतो-ऽपि वा ।शूद्राणामुपदेशन्तु दद्यात् स नरकं व्रजेत् ॥”इति गर्गः ॥ * ॥अस्य ज्ञानमावश्यकं यथा, --“वेदा हि यज्ञार्थमभिप्रवृत्ताःकालानुपूर्ब्ब्या विहिताश्च यज्ञाः ।तस्मादिदं कालविधानशास्त्रंयो ज्योतिषं वेद स वेद यज्ञान् ॥यथा शिखा मयूराणां नागानां मणयो यथा ।तद्बद्वेदाङ्गशास्त्राणां गणितं मूर्द्ध्नि संस्थितम् ॥”इति वेदाङ्गज्योतिषम् ॥ * ॥अस्याध्ययनफलं यथा, --“एवंविधस्य श्रुतिनेत्रशास्त्र-स्वरूपभर्त्तुः खलु दर्शनं वै ।निहन्त्यशेषं कलुषं जनानांषडब्दजं धर्म्मसुखास्पदं स्यात् ॥”इति माण्डव्यः ॥ * ॥अस्य ज्ञाने फलं यथा, --“ज्योतिश्चक्रे तु लोकस्य सर्व्वस्योक्तं शुभाशुभम् ।ज्योतिर्ज्ञानन्तु यो वेद स याति परमां गतिम् ॥”इति गर्गः ॥--शब्दकल्पद्रुमः

ज्योतिर्विद् पु० ज्योतिषां सूर्य्यादीनां गत्यादिकं वेत्ति विद्-किप् । ज्योतिःशास्त्राभिज्ञे । “दृष्ट्वा ज्योतिर्विदोवैद्यान् दद्याद्गां काञ्चनं महीम्” याज्ञ० । ज्योति-र्विदाभरणम् ।

ज्योतिर्विद्या स्त्री ज्योतिषां सूर्य्यादीनां गत्थादिज्ञानसा-धनं विद्या । ज्योतिःशास्त्रे ।--वाचस्पत्यम्

jyautiṣiká m. ʻ astrologer ʼ Pāṇ., jyōtiṣika -- m. VarBr̥S. [A. zuhāl ʻ fireplace ʼ.(CDIAL 5297)

Mahabharata: 4-42-22

adeśikā mahāraṇye grīṣme śatruvaśaṃ gatā

yathā na vibhramet senā tathā nītir vidhīyatām

Karna observed their troops had come to an unknown place possessed by enemies and in the mighty forest in the hot grīṣma season

Note:

Mahabharata: 2-72 21

divolkāś cāpatan ghorā rāhuś cārkam upāgrasat

aparvaṇi mahāghoraṃ prajānāṃ janayan bhayam

Translation by Ganguli: “Meteors fell from the sky, and Rahu by swallowing the Sun unseasonably alarmed the people terribly”

Mahabharata: 5-183 -22 “arkaṃ ca sahasā dīptaṃ svarbhānur abhisaṃvṛṇot”

When Parasurama fell down on the earth afflicted by the shaft of Bhishma, it is said that Rahu forcibly attained the blazing sun

Mahabharata: 14-76-15 “rāhur agrasad ādityaṃ yugapat somam eva ca”

when Arjuna was badly wounded by the Saindhavas during his military campaign for the Aswamedha yajna, it is said that Rahu swallowed both the sun and the moon at the same time

Mahabharata: 5-81- v.6,7

6 [व] ततॊ वयपेते तमसि सूर्ये विमल उद्गते

मैत्रे मुहूर्ते संप्राप्ते मृद्व अर्चिषि दिवाकरे

7 कौमुदे मासि रेवत्यां शरद अन्ते हिमागमे

सफीतसस्यमुखे काले कल्यः सत्त्ववतां वरः

kaumude māsi revatyāṃ śarad ante himāgame

sphītasasyamukhe kāle kalyaḥ sattvavatāṃ varaḥ

Translation by Ganguli: “The night having passed away, a bright sun arose in the east. The hour called Maitra set in, and the rays of the sun were still mild. The month was (Kaumuda Kartika) under the constellation Revati. It was the season of dew, Autumn having departed. The earth was covered with abundant crops all around.”

Note: Kartika was also known as Kaumuda.

Source: DDSA: The practical Sanskrit-English dictionary

Kaumudī (कौमुदी).—[kumudasyeyaṃ prakāśakatvāt aṇ ṅīṣ Tv.]

1) Moonlight; शशिना सह याति कौमुदी (śaśinā saha yāti kaumudī) Ku.4.33; शशिनमुपगतेयं कौमुदी मेघमुक्तम् (śaśinamupagateyaṃ kaumudī meghamuktam) R.6.85; (the word is thus popularly derived :-kau modante janā yasyāṃ tenāsau kaumudī matā).

2) Anything serving as moonlight, i. e. causing delight and balmy coolness; त्वं कौमुदी नयनयोरमृतं त्वमङ्गे (tvaṃ kaumudī nayanayoramṛtaṃ tvamaṅge) U.2; त्वमस्य लोकस्य च नेत्रकौमुदी (tvamasya lokasya ca netrakaumudī) Ku.5.71; या कौमुदी नयनयो- र्भवतः सुजन्मा (yā kaumudī nayanayo- rbhavataḥ sujanmā) Māl.1.34; cf. चन्द्रिका (candrikā).

3) The full moon day in Kārtika; तस्मात्तु कपिला देया कौमुद्यां ज्येष्ठपुष्करे (tasmāttu kapilā deyā kaumudyāṃ jyeṣṭhapuṣkare) Mb.13.13.32.

4) The full moon day in Āśvina.

5) Festivity (in general).

6) Particularly, a festive day on which temples, houses &c. are illuminated.

7) (At the end of titles of works &c.) Elucidation, throwing light on the subject treated; e. g. तर्ककौमुदी, साख्यतत्त्वकौमुदी, सिद्धान्तकौमुदी (tarkakaumudī, sākhyatattvakaumudī, siddhāntakaumudī) &c.

कौमुदी, स्त्री, (कुमुदस्य इयं प्रकाशकत्वात् “तस्येदं” ।४ । ३ । १२० । इत्यण् ततो ङीप् ।) ज्योत्स्ना ।इत्यमरः । १ । ३ । १६ । (यथा, कुमारे । ४ ३३ ।“शशिना सह याति कौमुदी ॥सह मेघेन तडित्प्रलीयते ।प्रमदाः पतिवर्त्मगा इतिप्रतिपन्नं हि विचेतनैरपि” ॥)उत्सवः । इति धरणी । (यथा, महाभारते १३पर्व्वणि ।“अकालकौमुदीञ्चैव चक्रतुः सार्व्वकालिकीम्” ॥कौमुदस्य कार्त्तिकमासस्य इयं “तस्येदम्” । ४ ।३ । १२० । इति अण् । ततो ङीप् । यदुक्तम् ।“कुशब्देन मही ज्ञेया मुद हर्षे ततो द्वयम् ।धातुज्ञैर्नियमैश्चैव तेन सा कौमुदी स्मृता” ॥)कार्त्तिकोत्सवः । स तु कार्त्तिकीपूर्णिमायां कर्त्तव्यः ।इति त्रिकाण्डशेषः । कार्त्तिकीपूर्णिमा ॥आश्विनीपूर्णिमा । इति शब्दरत्नावली । (यथा, --“आश्विने पौर्णमास्यान्तु चरेज्जागरणं निशि ।कौमुदी सा समाख्याता कार्य्या लोकविभूतये” ॥दीपोत्सवतिथिः । यथा, रघुप्रभृतिटीकाकृ-न्मल्लिनाथधृतभविष्योत्तरवचनम् ।“कौ मोदन्ते जना यस्यां तेनासौ कौमुदी स्मृता” ॥कुमुदान्येव कौमुदी । सुदी वा सालुक इति भाषा ॥)

--शब्दकल्पद्रुमः

कौमुद पु० “कौ मोदन्ते जनायस्मिन् कौमुदस्तेन कीर्त्तितः”इक्तुक्तलक्षणे १ कार्त्तिकमासे । “एतैरन्यैश्च राजेन्द्रैःपुरा मांसं न भक्षितम् । शारदं कौमुदं मासं ततस्तेस्वर्गमाप्लुयुः । कौमुदं तु विशेषेण शुक्लपक्षं नराधिप! ।वर्ज्जयेत् सर्वमांसानि धर्म्मोह्यत्र विधीयते” म० त० भार०

कौमुदी स्त्री कुमदस्येयं प्रकाशकत्वात् प्रिया अण् ङीप् ।१ न्योत्लायाम् अमरः । “शशिना सह याति कौमुदी”कुमा० १ तद्वत्प्रकाशिकायाम् “त्वमस्य लोकस्य च नेत्रकौ-दी” कुमा० कौमुदस्येवम् अण् ङीप् । “कुशब्देन महीज्ञेया मुद हर्षे० ततोद्वयम् । धातुज्ञैर्नियमैश्चैव तेन सांकौमुदी स्मृता” इत्युक्तायां २ कार्त्तिकपौर्ण्णमास्यां “कौमोदन्ते जनायस्यान्नानाभावैः परस्परम् । हृष्टास्तुष्टाःसुखापन्नास्तेन सा कौमुदी मता” इत्युक्तायाम् ३ आश्विनषौर्ण्णमास्याम् “आश्विने षौर्ण्णगास्यान्तु चरेज्जागरणं निशिकौमुदी सा समाख्याता कार्य्या लोकविभूतये” ति० त०लौङ्गोक्तेः । ४ दीपोत्मवतिथौ दीपोत्वतिथिं प्रकृत्यभविष्योत्तरे “कौमोदन्ते जनायस्यां तेन सा कौमुदी मता”“सखीजनोद्वीक्षणकौमुदीमुखम्” रघुः कौमुदी दीपोत्वातिथिः” इति मल्लि०” ५ उत्सवे धरणिः” ६ कार्त्तिकोत्सवेत्रिका० । स्वार्थे क । ह्रस्वे कौमुदिका ज्योत्स्नायाम् ।संज्ञायां कन् । उमासखीभेदे शब्दरत्ना० कुमुद + चतुरर्थ्यांकुमुदा० ठक् । कौमुदिक कुमुदसन्निकृष्टदेशादौ त्रि०

--वाचस्पत्यम्

A reference is made in MBh. to the thirty-sixth year from the date of the war in the text. In thirty-sixth year occurs the death of Krishna consistent with Gandhari’s curse.

Hindu tradition has recognized this thirty-sixth year as the start of Kali Yuga, calendrical reckoning.

The Bhagavata Purana (1.18.6), Vishnu Purana (5.38.8), and Brahma Purana (2.103.8) state that the day Krishna left the earth was the day that the Dvapara Yuga ended and the Kali Yuga began:

— Bhagavata Purana Part I. Motilal Banarsidass Publishers Private Limited. 1950. p. 137. (1.18.6) On the very day, and at the very moment the Lord [Krishna] left the earth, on that very day this Kali, the source of irreligiousness, (in this world), entered here.

— Wilson, H. H. (1895). The Vishnu Purana. S.P.C.K. Press. p. 61. (5.38.8) The Parijata tree proceeded to heaven, and on the same day that Hari [Krishna] departed from the earth the dark-bodied Kali age descended.

— Brahma Purana Part 2. Motilal Banarsidass. 1955. p. 515. (2.103.8) It was on the day on which Krishna left the Earth and went to heaven that the Kali age, with time for its body set in.

Gandhari’s curse states in Stri-vilapa parva: “In the thirty-sixth year from this, O slayer of Madhu, thou shalt, after causing the slaughter of thy kinsmen and friends and sons, perish by disgusting means in the wilderness.”

Mausala Parva confirms this: (After the death of Balarama), Keshava (Krishna)… also recollected the words that Durvasas had spoken at the time his body was smeared by that Rishi with the remnant of the Payasa he had eaten (while a guest at Krishna’s house). The high-souled one, thinking of the destruction of the Vrishnis and the Andhakas, as also of the previous slaughter of the Kurus, concluded that the hour (for his own departure from the world) had come.

Book 16: Mausala Parva

Kisari Mohan Ganguli, tr.

[1883-1896]

Death of Krishna

Section 4

…

"Proceeding then to the forest, Keshava beheld Rama sitting in a solitary spot thereof. He also saw that Rama had set himself to Yoga and that from out his mouth was issuing a mighty snake. The colour of that snake was white. Leaving the human body (in which he had dwelt so long), that high-souled naga of a 1,000 heads and having a form as large as that of a mountain, endued besides with red eyes, proceeded along that way which led to the ocean. Ocean himself, and many celestial snakes, and many sacred Rivers were there, for receiving him with honour. There were Karkotaka and Vasuki and Takshaka and Prithusravas and Varuna and Kunjara, and Misri and Sankha and Kumuda and Pundarika, and the high-souled Dhritarashtra, and Hrada and Kratha and Sitikantha of fierce energy, and Chakramanda and Atishanda, and that foremost of Nagas called Durmukha, and Amvarisha, and king Varuna himself, O monarch. Advancing forward and offering him the Arghya and water to wash his feet, and with diverse other rites, they all worshipped the mighty Naga and saluted him by making the usual enquiries.

"After his brother had thus departed from the (human) world, Vasudeva of celestial vision, who was fully acquainted with the end of all things, wandered for some time in that lonely forest thoughtfully. Endued with great energy he then sat down on the bare earth. He had thought before this of everything that had been fore-shadowed by the words uttered by Gandhari in former days. He also recollected the words that Durvasas had spoken at the time his body was smeared by that Rishi with the remnant of the Payasa he had eaten (while a guest at Krishna’s house). The high-souled one, thinking of the destruction of the Vrishnis and the Andhakas, as also of the previous slaughter of the Kurus, concluded that the hour (for his own departure from the world) had come. He then restrained his senses (in Yoga). Conversant with the truth of every topic, Vasudeva, though he was the Supreme Deity, wished to die, for dispelling all doubts and establishing a certainty of results (in the matter of human existence), simply for upholding the three worlds and for making the words of Atri’s son true. Having restrained all his senses, speech, and mind, Krishna laid himself down in high Yoga.

"A fierce hunter of the name of Jara then came there, desirous of deer. The hunter, mistaking Keshava, who was stretched on the earth in high Yoga, for a deer, pierced him at the heel with a shaft and quickly came to that spot for capturing his prey. Coming up, Jara beheld a man dressed in yellow robes, rapt in Yoga and endued with many arms. Regarding himself an offender, and filled with fear, he touched the feet of Keshava. The high-souled one comforted him and then ascended upwards, filling the entire welkin with splendour. When he reached Heaven, Vasava and the twin Ashvinis and Rudra and the Adityas and the Vasus and the Viswedevas, and Munis and Siddhas and many foremost ones among the Gandharvas, with the Apsaras, advanced to receive him. Then, O king, the illustrious Narayana of fierce energy, the Creator and Destroyer of all, that preceptor of Yoga, filling Heaven with his splendour, reached his own inconceivable region. Krishna then met the deities and (celestial) Rishis and Charanas, O king, and the foremost ones among the Gandharvas and many beautiful Apsaras and Siddhas and Saddhyas. All of them, bending in humility, worshipped him. The deities all saluted him, O monarch, and many foremost of Munis and Rishis worshipped him who was the Lord of all. The Gandharvas waited on him, hymning his praises, and Indra also joyfully praised him."

https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m16/m16004.htm

Section 5

Vaishampayana said: "Meanwhile Daruka, going to the Kurus and seeing those mighty car-warriors, the son of Pritha, informed them of how the Vrishnis had slain one another with iron bolts. Hearing that the Vrishnis along with the Bhojas and Andhakas and Kukuras had all been slain, the Pandavas, burning with grief, became highly agitated. Then Arjuna, the dear friend of Keshava, bidding them farewell, set out for seeing his maternal uncle. He said that destruction would soon overtake everything. Proceeding to the city of the Vrishnis with Daruka in his company, O puissant king, that hero beheld that the city of Dwaraka looked like a woman bereft of her husband. Those ladies who had, before this, the very Lord of the universe for their protector, were now lordless. Seeing that Partha had come for protecting them, they all set up a loud wail. 16,000 ladies had been wedded to Vasudeva. Indeed, as soon as they saw Arjuna arrive, they uttered a loud cry of sorrow. As soon as the Kuru prince met those beauteous ones deprived of the protection of Krishna and of their sons as well, he was unable to look at them, his vision being obstructed by tears. The Dwaraka river had the Vrishnis and the Andhakas for its water, steeds for its fishes, cars for its rafts, the sound of musical instruments and the rattle of cars for its waves, houses and mansions and public squares for its lakes. Gems and precious stones were its abundant moss. The walls of adamant were the garlands of flowers that floated on it. The streets and roads were the strong currents running in eddies along its surface. The great open squares were the still large lakes in its course. Rama and Krishna were its two mighty alligators. That agreeable river now seemed to Arjuna to be the fierce Vaitarani bound up with Time’s net. Indeed, the son of Vasava, endued with great intelligence, beheld the city to look even thus, reft as it was of the Vrishni heroes. Shorn of beauty, and perfectly cheerless, it presented the aspect of a lotus flower in the season of winter. Beholding the sight that Dwaraka presented, and seeing the numerous wives of Krishna, Arjuna wailed aloud with eyes bathed in tears and fell down on the earth. Then Satya, the daughter of Satrajit, and Rukmini too, O king, fell down beside Dhananjaya and uttered loud wails of grief. Raising him then they caused him to be seated on a golden seat. The ladies sat around that high-souled one, giving expression to their feelings. Praising Govinda and talking with the ladies, the son of Pandu comforted them and then proceeded to see his maternal uncle."

https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m16/m16005.htm

Gandhari’s curse

Book 11: Stri Parva

Stri-vilapa-parva

Section 25

Vaishampayana continued, "Having said these words, Gandhari, deprived of her senses by grief, fell down on the earth! Casting off her fortitude, she suffered her senses to be stupefied by grief. Filled with wrath and with sorrow at the death of her sons, Gandhari, with agitated heart, ascribed every fault to Keshava.

"Gandhari said, ‘The Pandavas and the Dhartarashtras, O Krishna, have both been burnt. Whilst they were thus being exterminated, O Janardana, why wert thou indifferent to them? Thou wert competent to prevent the slaughter, for thou hast a large number of followers and a vast force. Thou hadst eloquence, and thou hadst the power (for bringing about peace). Since deliberately, O slayer of Madhu, thou wert indifferent to this universal carnage, therefore, O mighty-armed one, thou shouldst reap the fruit of this act. By the little merit I have acquired through waiting dutifully on my husband, by that merit so difficult to attain, I shall curse thee, O wielder of the discus and the mace! Since thou wert indifferent to the Kurus and the Pandavas whilst they slew each other, therefore, O Govinda, thou shalt be the slayer of thy own kinsmen! In the thirty-sixth year from this, O slayer of Madhu, thou shalt, after causing the slaughter of thy kinsmen and friends and sons, perish by disgusting means in the wilderness. The ladies of thy race, deprived of sons, kinsmen, and friends, shall weep and cry even as these ladies of the Bharata race!’"

Vaishampayana continued, "Hearing these words, the high-souled Vasudeva, addressing the venerable Gandhari, said unto her these words, with a faint smile, ‘There is none in the world, save myself, that is capable of exterminating the Vrishnis. I know this well. I am endeavouring to bring it about. In uttering this curse, O thou of excellent vows, thou hast aided me in the accomplishment of that task. The Vrishnis are incapable of being slain by others, be they human beings or gods or Danavas. The Yadavas, therefore shall fall by one another’s hand.’ After he of Dasharha’s race had said these words, the Pandavas became stupefied. Filled with anxiety all of them became hopeless of life!’"

Section 26

"The holy one said, ‘Arise, arise, O Gandhari, do not set thy heart on grief! Through thy fault, this vast carnage has taken place! Thy son Duryodhana was wicked-souled, envious, and exceedingly arrogant. Applauding his wicked acts, thou regardest them to be good. Exceedingly cruel, he was the embodiment of hostilities, and disobedient to the injunctions of the old. Why dost thou wish to ascribe thy own faults to me? Dead or lost, the person that grieves for what has already occurred, obtaineth more grief. By indulging in grief, one increases it two-fold. A woman of the regenerate class bears children for the practice of austerities; the cow brings forth offspring for bearing burdens; the mare brings forth her young for acquiring speed of motion; the Shudra woman bears a child for adding to the number of servitors; the Vaishya woman for adding to the number of keepers of cattle. A princess, however, like thee, brings forth sons for being slaughtered!’"

Vaishampayana said, "Hearing these words of Vasudeva that were disagreeable to her, Gandhari, with heart exceedingly agitated by grief, remained silent. The royal sage Dhritarashtra, however, restraining the grief that arises from folly, enquired of Yudhishthira the just, saying, ‘If, O son of Pandu, thou knowest it, tell me the number of those that have fallen in this battle, as also of those that have escaped with life!’

https://www.sacred-texts.com/hin/m11/m11025.htm

ni-√mā Ā. -mimīte (pf. -mamire, RV. iii, 38, 7 ), to measure, adjust, RV. ; &c. (cf. nime).;nimitta n. (possibly connected with ni-√mā above) a butt, mark, target, MBh. sign, omen, Mn. ; Yājñ. ; MBh. &c. (cf. dur-n°) (Monier-Williams)

निमित nimita 1 See निर्मित; caused; शापोमयैवनिमितस्तदवैतविप्राः Bhāg.3.16.26. -2 Measured.

निमित्तम् nimittam [नि-मिद्-क्त Tv.] 1 A cause, motive, ground reason; निमित्तनैमित्तिकयोरयंक्रमः Ś.7.30. -2 The instrumental or efficient cause (opp. उपादान); धर्मार्थकाममोक्षाणांनिमित्तान्यविरोधतः Bhāg.3.7.32. -3 Any apparent cause, pretext; निमित्तमात्रंभवसव्यसाचिन् Bg.11.33; निमित्तमात्रेणपाण्डवक्रोधेनभवितव्यम् Ve.1. -4 A mark, sign, token. -5 A butt, mark, target; निमित्तेदूरपातित्वेलघुत्वेदृढवेधने Mb.7.74.23; निमित्तादपराद्धेषोर्धानुष्कस्येववल्गितम् Śi.2.27. -6 An omen, prognostic (good or bad); निमित्तंसूचयित्वा Ś.1; निमित्तानिचपश्यामिविपरीतानिकेशव Bg.1.31; R.1.86; Ms.6.50; Y.1.203;3.171. -7 Means of knowledge; तस्यनिमित्तपरीष्टिः MS.1.1.3. -8 Function, ceremony; एतान्येवनिमित्तानिमुनीनामूर्ध्वरेतसाम् (कर्तव्यानि); Mb.12.61.6. (निमित्त is used at the end of comp. in the sense of 'caused or occasioned by'; किन्निमित्तोऽयमातङ्कः Ś.3. निमित्तम्, निमित्तेन, निमित्तान् 'because of', 'on occount of'.) -Comp. -अर्थः the infinitive mood (in gram). -आवृत्तिः f. dependence on a special cause. -कारणम्, हेतुः an instrumental or efficient cause. -कालः a specific time. -कृत् m. a crow -ज्ञ a. acquainted with omens (as an astrologar). -धर्मः 1 expiation. -2 an occasional rite. -नैमित्तिकम् (du.) cause and effect; निमित्तनैमित्तिकयोरयंक्रमः Ś.7.30. -परीष्टि f. scrutiny of the means (of knowing); तस्यनिमित्तपरीष्टिः MS.1.1.3. -मात्रम् the mere efficient cause or instrument; Bg.11.33. -विद् a. knowing good or bad omens. (-m.) an astrologer.

निमित्तकम् nimittakam 1 A cause. -2 Kissing.

निमित्तिन् nimittin a. Having a cause, influenced by (some cause or ground).(Apte)

निमित्तं, क्ली, (नि+ मिद् + क्त।संज्ञापूर्ब्बकत्वान्ननत्वम्।) हेतुः। (यथा, देवीभागवते।१।१८।५।“किंनिमित्तंमहाभाग ! निःस्पृहस्यचमांप्रति।जातंह्यागमनंब्रूहिकार्य्यंतन्मुनिसत्तम ! ॥”)चिह्नम्।इत्यमरः।३।३।७६॥शकुनः।यथा,“निमित्तानिचपश्यामिविपरीतानिकेशव ! ।इतिश्रीभगवद्गीता॥

निमित्तकं, क्ली, (निमित्त+ संज्ञायांकन्।)निमित्तनिश्चयादागतम्।चुम्बनम्।इतिशब्द-ला॥निमित्तञ्च॥

निमित्तकारणं, क्ली, (निमित्तंकारणम्।)समवायिकारणासमवायिकारणाभ्यांभिन्नम्।तृतीयकारणम्।यथा।घटंप्रतिकुलाल-दण्डचक्रसलिलसूत्रादि।इतिभाषापरिच्छेद-सिद्धान्तमुक्तावल्यौ॥

निमित्तकृत्, पुं, (निमित्तंस्वरुतेनशुभाशुभशकुनंकरोतीति।कृ+ क्विप्।) काकः।इतिराज-निर्घण्टः॥

निमित्तवित्, [द्] पुं, (निमित्तंशुभाशुभलक्षणंवेत्तीति।विद्+ क्विप्।) दैवज्ञः।गणकः।इतिहेमचन्द्रः।३।१४६॥

-- शब्दकल्पद्रुमः

निमित त्रि०नि + मि--क्त।समदीर्घविस्तारपरिमाणयुर्क्तनिघशब्देदृश्यम्।

निमित्त न०नि + मिद--क्त।“अनात्मनेपदनिमित्ते” पासूत्रनिर्देशान्ननदस्यनः।१हेतौ२चिह्नेचअमरः“निमित्तेषुचसर्वेषुह्यप्रमत्तोचभवेन्नरः” स्मृतिः“मयैवपूर्वंनिहताधार्त्तराष्ट्राःनिमित्तमात्रंभवसव्यसाचिन्।” गीता“अतःकालंप्रवक्ष्यामिनिमित्तंकर्मणामिह” ति०त०भविष्यपु०“मासपक्षतिथीनाञ्चनिमित्तानाञ्चसर्वशः।उल्लेखनमकुर्वाणोनतस्वफलभाग्भवेत्” ति०त०भविष्यपु०।ब्रह्माण्डे“निमित्तानिचशंसन्तिशुभाशुभफलोदयम्” “निमित्तंमनश्चक्षुरा-दिप्रवृत्तौ” हस्तामलकम्।शुभाशुभसूचके३शकुने“निमित्तानिचपश्यामिविपरीतानिकेशव!” गीता४फलेउद्देश्ये“निमित्तात्कर्मयोगे” वार्त्ति०निमित्त-मिहफलम्।५निमित्तनिश्चयेनैमित्तिकंनिमित्तनिश्च-यादागतम्।६शरव्येचशब्दार्थचि०स्वार्थेकतत्रार्थेसंज्ञायांकन्।निमित्तकचुम्बनेशब्दमाला।

निमित्तकारण न०कर्म०।नैयायिकमतेसमवायिकारणाऽ-समवामिकारणभिन्नकारणेतथाहिघटादौमृत्तिकादिसमवायिकारणम्कपालद्वयसंयोगोऽसमयवायिकार-णम्।कुलालचक्रदण्डसलिलसूत्रादिनिमित्तकारणम्।एवमदृष्टादिकालादिच।एवन्यत्रयथायथमुन्नेयम्।

निमित्तकृत् त्रि०निमित्तंशकुनंरुतेनकरोतिकृ--क्विप्तुक्।रवेणदुष्टादुष्टशकुनकारकेकाकेराजनि०।तस्यरवेणशकुनसूचकत्वात्तथात्वम्।काकरुतशब्दे१८४४पृ०दृश्यम्।

-- वाचस्पत्यम्

निमित्तबध पु०निमित्तेनरोधादिहेतुनाबधः।रोधादि-निमित्ते१गवादेर्वधेतत्रप्रायश्चित्तादिप्रा०त०उक्तंयथा“रोधादिनिमित्तकप्रायश्चित्तम्।तत्राङ्गिराः“रोधनेबन्धनेचापियोजनेचगवांरुजः।उत्पाद्यमरणंवापिनिमित्तीतत्रलिप्यते।पादञ्चरेद्रोधबधेद्वौपादौबन्धनेचरेत्।योजनेपादहीनंस्याच्चरेत्सर्वंनिपातने” ।निमित्तीलिप्यतइतियथाकथञ्चित्मरणनिमित्ततारतम्येन“योभूयआरभतेतास्मन्फलेविशेषः” इत्यापस्तम्बवचनात्पापविशेषेणंलिप्यतेतद्विशेषात्प्रायश्चित्तविशेषमाहपादञ्चरेदित्यादि।रोधःशीणायाःगोराहारप्रचारनिर्गमविरोधः।बन्धन-मयथाबन्धनमकालबन्धनञ्च।योजनंहलशकटादौयोजनंतत्रातिवाहादिनेतिशेषः।अत्रैवविषयेव्यवनः“प्राजापत्यद्वयंगोहत्याप्रायश्चित्तंरोधनबन्धनयोक्त्र-बधेपादवृद्ध्यानस्रानिलोमानिशिखावर्जंसशिखंवपनंत्रिषवणंगवानुगमनंसहशयनंसुमहत्तृणानिरथ्यासुचारयेत्व्रतान्तेब्राह्मणभोजनमिति” ।रोधन-बन्धनयोक्त्रबधइत्यादेरयमर्थःरोधनिमित्तकवधेप्राजा-पत्यस्यपादःप्रायश्चित्तंनखच्छेदनमात्रम्।बन्धन-निमित्तबधेप्राजापत्यस्यद्वौपादौनखानांलीम्नाञ्चछेदनम्।योक्त्रनिमित्तेचबधेप्राजापत्यपादत्रयंनखलोमशिखावर्जकेशच्छेदनञ्च।दण्डादिप्रहारबधेसम्पूर्णप्राजापत्यम्नखलोमकेशशिखाच्छेदनञ्चइति।एतद्विषयएवमिताक्षराधृतंसंवर्त्तवचनंतदेकवाक्य-त्वात्तद्यया“पादेऽङ्गलोमवपनंद्विपादेश्मश्रुणोऽपिच।त्रिपादेचशिम्नावर्जंवशिखन्तुनिपातने” ।अत्रप्राजापत्यस्यपादादित्वेकिंमानमितिचत्।पराशर-वचनम्“रोधनेतुचरेत्पादंबन्धनेचार्द्धमेवहि।योजनेपादहीनंस्यात्प्राजापत्यंनिपातने” ।“कृच्छ्रमज्ञानताड़ने” इतिवार्हस्वत्यात्।दण्डोऽत्रहस्त-प्रमाणोग्राह्यः।तदधिकेतुद्विगुणपायश्चित्तविधानात्।यथाअङ्गिराः“अङ्गुष्ठमात्रःस्थौल्येनबाहुमात्रःप्रमाणतः।सार्द्रश्चसपलाशश्चदण्डइत्यभिधीयते” ।“अस्यादूर्द्ध्वप्रहारेणयदिगांविनिपातयेत्।द्विगुणन्तुभवेत्तत्रप्रायश्चित्तमितिस्थितिः” ।सपलासःसपत्रः।एतद्वचनविषयएवच्यवनीक्तप्राजापत्यद्वयमितिएतच्चा-ज्ञानतःयथावृहस्पतिः“पादञ्चरेत्रोधवधेकृच्छ्रार्द्धंबन्धधातने।अतिवाहेचपादोनंकृच्छ्रमज्ञानताड़ने” ।अन्नानञ्चक्षीणायामक्षीणत्वभ्रमः।क्षैण्यज्ञानेतुपायिकमरणंज्ञात्वाप्रवृत्तस्यचान्द्रायणपादादिकम्।यथाहारीतः“नासाच्छेदनदाहेषुकर्णच्छेदनबन्धने।अतिदोहातिवाहाभ्यांकृच्छ्रंचान्द्रायणंचरेत्” हत्वेतिशेषः।कृच्छ्रंव्रतंतेनचान्द्रायणव्रतमित्यर्थः।इतिशूलपाणिमहामहोपाध्यायाः।भवदेवभट्टैस्तुनिपातनेकूपावदादिषुइतिव्याख्यातंतदपियुक्तंअन्यथातत्रपातजनकभयादिदर्शकस्यप्रायश्चित्तस्यानध्य-तद्धायापत्तेः।“शस्त्रादिनातुहत्वागांमानवंततपाक्षरेत्।रोधादिनात्वाङ्गिरनमापस्तम्बोक्तमेवचेति”बृहस्पत्युक्तंतत्रप्रयमादिपदामुष्टिलोष्ट्रलगुड़विषाग्न्या-दीनांप्रायिकमृत्युफलानांग्रहणम्।रोधादिनेतियथाकथञ्चिन्निमितमात्रस्य, बन्धादेरितिशूलपाणिव्याख्या-न्तराच्च।तस्मान्निपातनपरम्उभयपरम्।एतच्चरात्रौरक्षणार्थंरोधबन्धनव्यतिरिक्तविषयम्।“सायंसंयम-सनार्थन्तुनदुष्येद्रोधबन्धयोः” इतिअङ्गिरोवचनात्वन्धनेमिताक्षरायांविशेषमाहव्यासः“ननारि-केलैर्नचशाणतालैर्नचापिमौञ्जैर्नचबन्धशृङ्खलैः।एतैस्तुगावोनहिबन्धनीयाबद्ध्वातुतिष्ठेत्परशुंगृहीत्वा।कुशैःकाशैश्चबध्नीयात्स्थानेदोषविवार्जते” ।निमित्तिन्शब्देवक्ष्यमाणेमन्यूत्पादनदारा२हननेच।

निमित्तविद त्रि०निमित्तंशकुनंशुभाशुभसूचकंलक्षणंवेत्तिविद--क्विप्।निमित्तज्ञेदैवज्ञेहेमच०निमि-त्तज्ञादयोऽप्यत्र।“निमित्तज्ञस्तपोधनः” रघुः।

निमित्तिन् त्रि०निमित्तवस्त्यस्यइनि।निमित्तयुक्ते१कार्येप्रा०वि०उक्ते२बधकर्त्तृभेदेचयथा“कर्त्ताचपञ्चविधःकर्त्ताप्रयोजकोऽनुमन्ताअनुग्राहकोनिमित्तीचेति” ।निमित्तिनमाहविष्णुः“अन्यायेनगृहीतस्वोन्याय-मर्थयतेतुयः।यसुद्दिश्यत्यजेत्प्राणांस्तमाहुर्ब्रह्म-घातकम्” तल्लक्षणंप्रो०वि०उक्तं“उद्देश्यत्वेसतिहन्तुर्मन्यूत्पादकोनिमित्तो” इतिमन्यूत्पादनेनिमि-त्तमाहतत्रैववृद्धशा०“गोभूहिरण्यहरणेस्त्रीसम्ब-न्धकृतेऽपिच।यमुद्दिश्यत्यजेत्प्राणांस्तमाहुर्ब्रह्म-धातकम्” वृहस्मतिः“ज्ञातिमित्रकलत्रार्थंसुहृत्क्ष-त्रार्थमेवच।यमुद्दिश्यत्यजेत्प्राणांस्तभाहुर्ब्रह्मघा-तकम्।गोभूहिरण्यहरणेस्त्रीणांक्षेत्रगृहस्यच।यमुद्दिश्यत्यजेत्प्राणांस्तमाहुर्ब्रह्मथातकम्।गुर्वर्थंपितृमात्रर्थमात्मार्थमथवापुनः।यमुद्दिश्यत्यजेत्प्राणां-स्तमाहुर्ब्रह्मथातकम्” षट्त्रिंशन्मतमितिकृत्वापठितम्“आक्रोशितस्ताद्धितोवाधनैर्बापरिपीडितः।यमुद्दिश्यत्यजेत्प्राणांस्तगाहुर्ब्रह्मघातकम्” सत्रोद्दि-श्येतिसर्वत्रकीर्त्तनात्उद्देशाभावेनिमित्ततामा-त्रेणवधित्वंनास्तिअर्थादिहरणाक्रोशनताड-नादीनांमन्युकारणानामुपात्तत्वादेतेषाभभावेधनाद्यर्थंवृक्षारोहणादिनायेम्रियन्ते(यदिमह्यंघनंनदास्यसितदावृक्षारोहणेनमरिष्यामीतिं) तत्रकीर्त्तनमात्रेणनिमित्तबधोनास्तितथाचपठन्ति“अमम्बेनयःफश्चित्द्विजःप्राणान्परित्यजेत्।तणैषतद्भवेत्पाषंनतुयंपरिकी-र्तयेत्” अयम्बन्धेगेतिवाक्कृतादिसकलापराधसम्ब-न्धामावपरंयच्च“सम्बन्धेनविनादेव! शुष्कवादेनकोपितः” इतिभविष्यपुराणवचनंवार्षिकप्रायश्चित्त-विधायकंतत्वाक्कृतेतरापराधसम्बन्धाभावपरं“शुष्क-वादेनकोपितः” इत्यभिधानात्।एवंयत्राक्रोशनादौपश्चात्कृतेनापराधःतत्रापिनबधःयथावृहस्पतिः“आष्युष्टस्तयदाक्रोशँस्ताडितःप्रतिताडवम्।हत्वा-ततायिनञ्चैवनापराधीभवेन्नरः” ।शास्त्रविहितताड-मादौकृतेयत्रपुत्रशिष्यादिर्म्रियतेतत्रापिबधोनाख्येवतथाभविष्यपुराणे“पुत्रःशिष्यस्तथाभार्य्याशासितश्चेद्विनश्यति।नशास्तातत्रदोषेणलिप्यतेदेवसत्तम! ।अशास्त्रीयताडनादौभवत्येवयथामनुः।“पुत्रःशिष्यस्तथाभार्य्यादासीदासस्तुपञ्चमः।प्राप्ताप-राधास्ताह्याःस्यूरज्ज्वावेणुदलेनवा।अधस्तान्नुप्रहर्त्तव्यंनोत्तमाङ्गेकदाचन।अतोऽन्थथातुप्रहरँ-श्चौरस्याप्नोतिकिल्यिषम्” ।एवञ्चविहितदण्डाचरणेशास्त्रीयकरग्रहणेक्रियमाणेयदिम्रियतेतदापिवधोनास्त्येवदण्डादिशास्त्रविरोधान्निषेधाप्रवृत्तेः।वधनिमित्तिनस्तुप्रायश्चित्तंतत्रोक्तंयथा“निमित्तिनस्तुवचनात्त्रैवार्षिकंसम्बन्धे, असम्बन्धेवार्षिकंयथाभविष्ये“ससम्बन्धयदाविप्रोहत्वात्मानंमृतोगुह! ।निर्गुणःसहसाक्रोधादुमृहक्षेत्रादितोविभो! ।त्रैवार्षिकंव्रतंकुर्य्यात्ब्रह्मचर्व्यञ्चरन्वने” ।सम्बन्धशब्दोऽत्रधनसम्बन्धपरः।ताड़नादिनातिरस्कारेऽपित्रैवार्षिकमाहसएव“तिरस्कतोयदाविप्रोनिर्गुणोम्रियतेऽनच! ।सनिमित्तंयदाविप्रस्तदेदंशुद्धवेचरेद।त्रैवार्षिकंब्रह्मचर्य्यंकृत्वाशुध्येतविप्रहा” ।षनताडनादिसम्बन्धाभावेवाक्कलहमात्रेणमृतेवार्षिकमाहसएव“यसुद्दिश्यद्विजोहन्यात्ब्राह्मणंस्वयमेवहि।आत्मानंसहसाक्रोधात्तस्यकिन्नुभवेदिदम्।सम्बन्धेनविनादेव! शुष्कवादेनकोपितः।केशस्मश्रुनखादीनांकृत्वावैवपनंगुह! ।ब्रह्मचर्य्यञ्चरन्वीर! वर्षेणैकेनशुध्यति” एतत्त्रितय-कारणाभावेऽर्थलोभादिनामृतेप्रायश्चित्ताभावइतिप्रागुक्तम्” प्रा०चि०।

-- वाचस्पत्यम्

Saturday, October 5, 2013

Planetary position at the start of Mahabharata war.

The blogpost below was written in 2013, six years before I did my own analysis of Mahabharata references to deduce / validate the traditional date, 35 years before the start of the Kali Maha Yuga. The war started on October 23, 3136 BCE, in the year Krodhi.

Request readers to read my ebook.

https://www.amazon.in/MYTH-EPOCH-ARUNDHATI-NILESH-NILKANTH-ebook/dp/B07YVFNQLD/ref=cm_cr_arp_d_pl_foot_top?ie=UTF8

The specific chapter deciphering the date can be read here also

https://www.academia.edu/40802932/DATE_OF_MAHABHARATA_FROM_INTERNAL_EVIDENCES

Read my blog to know the contents and the links to ebook in amazon UK and USA

https://jayasreesaranathan.blogspot.com/2019/10/my-book-myth-of-epoch-of-arundhati-of.html

*****************

The reference to planets and their motion at the start of Mahabharata war pertains to Nimittha (निमित्त ) and the results connected with planetary motions or in other words astrology, and not exactly about the position of those planets as per astronomy. Therefore one must not take the reference to planets at face value.

तरिवर्णाः परिघाः संधौ भानुम आवारयन्त्य उत

trivarṇāḥ parighāḥ saṃdhau bhānum āvārayanty uta)

अहॊरात्रं मया दृष्टं तत कषयाय भविष्यति

23 अलक्ष्यः परभया हीनः पौर्णमासीं च कार्त्तिकीम

चन्द्रॊ ऽभूद अग्निवर्णश च समवर्णे नभस्तले

ahorātraṃ mayā dṛṣṭaṃ tat kṣayāya bhaviṣyati

23 alakṣyaḥ prabhayā hīnaḥ paurṇamāsīṃ ca kārttikīm

candro 'bhūd agnivarṇaś ca samavarṇe nabhastale)

राजानॊ राजपुत्राश च शूराः परिघबाहवः

rājāno rājaputrāś ca śūrāḥ parighabāhavaḥ)

saṃgrāmaṃ yojayet tatra tāṃ hy āhuḥ śakra devatām

18 सप्तमाच चापि दिवसाद अमावास्या भविष्यति

संग्रामं यॊजयेत तत्र तां हय आहुः शक्र देवताम

शनैश्चरः पीडयति पीडयन पराणिनॊ ऽधिकम

śanaiścaraḥ pīḍayati pīḍayan prāṇino 'dhikam)

Saturn posited in the third pada of Purva phalguni means it is in the 7th pada (of the 9-padas) of Leo.

From there it is afflicting both Rohini and Vishaka.

That means the exact drishti would fall on the 7th pada in Libra and 7th pada in Taurus.

The 7th pada in Libra is Vishaka 1st pada.

The 7th pada in Taurus is Rohini 4th pada.

The position of saturn could not be at any other place than 7th pada of Leo (3rd pada of P.Phalguni) because if it is one pada behind, it can not aspect Vishaka. If it is one pada forward, it can not aspect Rohini.

śanaiścaraḥ pīḍayati pīḍayan prāṇino 'dhikam (5-141-7)

अनुराधां परार्थयते मैत्रं संशमयन्न इव

anurādhāṃ prārthayate maitraṃ saṃśamayann iva (5-141-8)

बरह्मराशिं समावृत्य लॊहिताङ्गॊ वयवस्थितः (6-3-17)

brahmarāśiṃ samāvṛtya lohitāṅgo vyavasthitaḥ)

विशेषेण हि वार्ष्णेय चित्रां पीडयते गरहः (5-141-9)

viśeṣeṇa hi vārṣṇeya citrāṃ pīḍayate grahaḥ)

दिवश चॊल्काः पतन्त्य एताः सनिर्घाताः सकम्पनाः (5-141-10)

divaś colkāḥ patanty etāḥ sanirghātāḥ sakampanāḥ)

anurādhāṃ prārthayate maitraṃ saṃśamayann iva

अनुराधां परार्थयते मैत्रं संशमयन्न इव

viśeṣeṇa hi vārṣṇeya citrāṃ pīḍayate grahaḥ" (5-141-9)

STAR | THITHI | 1ST KARANA | 2ND KARANA |

Uttara phalguni | Navami | Taitila | Gara |

Hastha | Dasami | Vanija | Bhadra / Vishti |

Chitra | Ekadashi | Bava | Balava |

Swati | Dwadashi | Kaulava | Taitila |

Vishaka | Trayodashi | Gara | Vanija |

Anu radha | Chathurdashi | Bhadra | Sakuni |

Jyeshta | Amavasya | Chathuspad | Nagava |

Chitra | Ekadashi | Gara | Vanija |

Swati | Dwadashi | Bhadra | Sakuni |

Vishaka/ Anuradha? / Jyeshta | Trayodashi/ Amavasya | Chathuspad | Nagava |

From Taurus, 7th and 9th aspect falls on Scorpio and Capricorn respectively. In both cases, direct affliction of Sravana is possible but on Vishaka factor, approach towards Vishaka would be there.

ऐन्द्रं तेजस्वि नक्षत्रं जयेष्ठाम आक्रम्य तिष्ठति

aindraṃ tejasvi nakṣatraṃ jyeṣṭhām ākramya tiṣṭhati

vapūṃṣy apaharan bhāsā dhūmaketur iva sthitaḥ