If rice farming was domesticated prior to 9000 BCE in India, as noted by Stevens and Fuller (See embedded document), the origin of India languages CANNOT be linked to steppe hypothesis of Renfrew. Indian sprachbund, language union or linguistic area is an indigenous evolution and hence, Meluhha speech form seen on Indus Script messages.

If agriculture spread from India to the Fertile Crescent, PIE polemics will have to be turned upside down. I am happy because my Meluhha thesis for Indus Script decipherment stands validated with thousands of words of Meluhha spread all over Europe and in Mon-Khmer languages through Munda-Santali. I have posited an Ancient Maritime Tin Route from Hanoi to Haifa of 4th m.BCE whch explains why India was an economic superpower contributing to over 33% of Global GDP in 1 CE. The tin ingots of Haifa shipwreck had Indus Script hieroglyphs, deciphered as ranku dhatu muh 'tin ore ingot'.

S. KalyanaramanSarasvati Research Centre

See: http://indiafacts.org/how-old-is-indian-agriculture/?fbclid=IwAR0G4hRFwj9jtDMqkytIXsxAxcaCxWDa1pJAKZrXxg_SeTRyiWb9bP6Tjg0How old is Indian agriculture? by Anil Suri

13 June 2018

Given the relatively abrupt appearance of cultivation practices in the Fertile Crescent, is it unreasonable to ask if agriculture may have actually come to the Fertile Crescent from India?

It is common knowledge now that food production in the northwestern part of the Indian subcontinent began with the Mehrgarh Neolithic in the early 7th millennium BCE. What is less known is that there were many independent centres for the development of agriculture on the subcontinent. There is evidence of rice ostensibly being used as food on the Ganga plains from 13,000 years ago. However, the archaeological data on early agriculture remains fragmentary. We take a look at a very recently published scientific paper which came up with some fascinating findings about the early agriculture on the eastern Ganga plain. Thereafter, we shall try to retrace the evolution of Indian agriculture from the earliest beginnings. This shall inevitably bring us to the commonly-held notion – one that has acquired the status of confirmed fact by sheer force of repetition – that agriculture arrived in India from the Near East. We shall look at other evidence from the subcontinent, not all of which is recent, but which has been surprisingly ignored, and re-examine textbook theories about the history of Indian agriculture.

Lahuradewa, the gift that keeps on giving

A paper published last month (May 2018) in Current Science came up with some stunning insights into early agriculture on the banks of Lahuradewa lake in eastern Uttar Pradesh. The area, located in the Sant Kabir Nagar District, has been in the limelight for over two decades now thanks to the

discovery of outright rice cultivation from the mid-7

th millennium (

i.e., 6000s) BCE, carbonised rice grains dating as far back as ~11,000 BCE, and micro-charcoal particles and Cerealia pollen, providing evidence of human activity and some form of slash-and-burn agriculture in the region from at least 13,000 BCE. Owing to the wealth of archaeological evidence now available, it is now generally

accepted that the Ganga plains were an independent centre for the domestication of rice, as opposed to the earlier – and still often repeated – view that rice cultivation originated in China and spread to India from there. However, while the evidence indicated people were growing and cooking rice by the lake from that long ago, it wasn’t clear what stage of agriculture had been reached by then.

The latest

paper by Biswajeet Thakur, Anju Saxena and IB Singh fills in some major gaps in our understanding. They found a type of algae, called diatoms in the sediments of the lake going back around 10,000 years. Some of them would have been washed into the lake from the banks, and got embedded in the sediments. Diatoms can be of many types. Specifically, the discovery of the type of diatoms that thrive in standing water in paddy fields, called, simply, paddy field diatoms going back to ~7300 BCE, tells us that people were

cultivating rice on the banks as early as the mid-8

th millennium BCE. Additional corroboration is provided by the presence from ~6300 BCE of other types of diatoms which result from organic pollution from human activities (anthropogenic diatoms). This seems to push back the date for rice cultivation in the region by a few centuries, if not a full millennium.

What these findings tell us is that, when the lake swelled its banks in the monsoon, leading to stagnant water on the lands by the lake, the dwellers by the lake from as early as 9300 years ago were growing rice on the water-logged land, to harvest it in the autumn. This is not the end of the story – in fact, this is where it gets interesting.

So when did it actually begin?

Significantly, this means that the dwellers by Lahuradewa lake had progressed to wetland rice cultivation over 9000 years ago. Rice is grown in water-logged fields for a variety of reasons, including the very important one of controlling weeds, which do not grow very well in water. This is one of the reasons why rice

transplantation was invented (although we don’t have the evidence to tell if the early Lahuradewa people were resorting to deliberate transplantation). So they had by then identified the varieties of rice which had adapted to growing in standing water. Also, clearly, they were adept at exploiting the monsoon for agriculture.

But what about before this time? After all, the earliest carbonized rice grains from the Lahuradewa region date back much further. Here, unfortunately, the physical limits of the lake play spoilsport. The base of the lake is dated to around 10,000 years ago, as that is when the lake had started forming. Although some diatoms have been found from that long ago, their identification is difficult. This is typical in shallow waters. Dr. Thakur says that, at that time, it was probably not the contiguous water body it was to evolve into later, and there were only many shallow pools of water, which may have nevertheless supported agriculture on the low land. But the shallow, disconnected pools would not have been conducive to the assembling and preservation of any diatoms from paddy fields on the banks.

This leaves us in a tantalising situation. Rice was first grown as a dryland crop, before it was adapted for wetland agriculture. This is perfectly natural: after all, rice, like all other cereals, is merely a variety of grass that was originally growing wild. So when did this progression to wetland agriculture take place?

Beyond the Holocene: Agriculture in the Pleistocene

By now, it will be obvious that obtaining archaeological evidence is a huge challenge on the subcontinent. Features like water bodies have undergone multiple changes over thousands of years, so they may not yield all the evidence we would like to have. While this is true of most of the world, what uniquely complicates matters in India is that most areas have been continuously lived on and used for agriculture from time immemorial to the present day, making any evidence irrecoverable. Barring the occasional stroke of luck, we are mostly down to reconstructing the past from sketchy data.

To trace the trajectory from incipient cultivation as a dry crop to the wetland crop rice had become by around 7500 BCE, we must journey south, indeed, as far down as the southern part of Sri Lanka. To the mesmerizingly beautiful

Horton Plains National Park, to be precise. Here, there is

evidence of cattle herding and grazing, microcharcoal indicating the use of fire to clear the land of forests, cultivation of edible plants, and early management of barley and oats from – hold your breath – 15,500 BCE. It is believed the subcontinent experienced a semi-arid climate between 22,000 and 15,500 BCE, followed by a sustained, progressively warmer spell, with a concomitantly strengthening monsoon, starting around 16,500 BCE. Thus, early attempts at pastoralism and agriculture begin almost as soon as the climate became ever so slightly conducive. The climate got progressively better for agriculture, peaking in an extremely humid period around 6700 BCE. As the humidity increased, cultivated rice made its first known appearance here around 13,000 BCE. Notice that the early dwellers of the Horton Plains seem to have figured out which crop was best suited to a particular climate. Closely following the improvement in the climate, intensive agriculture in the region began around 11,000 BCE, and there was an abrupt shift in emphasis from oats and barley to rice after 8000 BCE. The fact that intensive rice cultivation was being done on the Ganga plain by no later than the mid-8

th millennium BCE, as described above, shows there were many independent centres for the establishment of agriculture in the subcontinent, and that the progress in agriculture happened closely in tandem with climactic changes.

In around 16,000 BCE, which falls in the Ice Age, India and Sri Lanka would have been contiguous as the sea level was about

120 metres lower than it is today. (Around 8000 BCE, it was still 50 metres lower.) This early attempt at agriculture was no flash in the pan. Archaeologists believe that there is a continuity of agricultural tradition in the subcontinent right from then. The archaeologist, Premathilake writes,

“The evidence of early form of agricultural activities found in the Horton Plains do not appear to have got isolated at the regional level and similar type of evidence in the form of cultivated pollen and other proxies is available in the Indian subcontinent.”Interestingly, it is from around the early 7

th millennium BCE, at the time of maximum humidity, that we have the earliest evidence of food production in the Indus Valley Tradition, in

Mehrgarh, Balochistan. In Rajasthan, the sediments of the salty Lunkaransar lake in the Bikaner district, and the well-known Sambar lake, show a marked increase of both carbonized (burnt) scrub and wood fragments as well as Cerealia pollen, from 8300 BCE and 7000 BCE respectively, clearly indicating agricultural activity. The Nilgiri hills also show Cerealia pollen from around 11,500 BCE, and a similar spurt in carbonized vegetable matter and Cerealia pollen from 8000 BCE (Chakrabarti DK in

The Oxford Companion to Indian Archaeology: The Archaeological Foundations of Ancient India, OUP, New York, 2006, pp. 106).

Jhusi near Allahabad has provided evidence that, from the earliest 7

th millennium BCE, if not earlier,

multi-cropping was being practiced by the Neolithic people there. Both winter crops, such as barley and many types of wheats, as well as rice and adlay millets, oil seeds like sesame, and a variety of legumes including

masur,

mung, peas and horsegram, and fruits including grapes and

amla (gooseberry), were being cultivated from the earliest known levels here. This stunningly diverse crop record implies several millennia of prior agricultural development.

Did agriculture arrive in India from the Fertile Crescent?

It is a long-standing myth that agriculture came to India from the

Fertile Crescent (FC). This is regularly repeated even in the scholarly literature, in defiance of the wealth of archaeological evidence which clearly shows that agriculture in India was an indigenous, autochthonous development, and has now acquired the status of confirmed fact. Archaeologists casually talk of crops like barley and pulses having reached the Indus Valley from the FC in spite of the fact that wild barley is native to the region, and the archaeological data indicates the

in situ organic development of agriculture from hunting-gathering. Indeed, you will get branded a “nationalist” or “saffron warrior” merely for pointing out that evidence contradicts the outdated west-to-east diffusion model. The earliest evidence of cultivation in the FC

dates to only around 10,000 BCE. Also, contrary to the notion of a Biblical “cradle of civilization” which has persisted in modern scholarly discourse, even within the FC, there are believed to have been multiple, independent centres for the establishment of agriculture.

The commencement of agriculture virtually at the southernmost tip of the subcontinent, that too almost immediately after the onset of a favourable climactic spell as long ago as the 16th millennium BCE, unambiguously means that agriculture was indigenous to the subcontinent. This is corroborated by the fact that the establishment and progress of agriculture in various regions of India followed the strengthening monsoon over the millennia.

Did agriculture go to the Fertile Crescent from India?

Although the data from the subcontinent is still far from complete, this is now a possibility worth considering. The key is the regional climate, and the vegetation it would have supported. Between 15,000 BCE and 13,000 BCE, the Near East was a cold, open landscape, covered with plants like Chenopodiaceae and Artemisia. Thereafter, up to around 10,500 BCE, an increase in temperature and humidity led to the expansion of deciduous oak forests, as well as grasslands. The plant products that people living here may have used for food include nuts like pistachios, almonds and chestnuts, and edible fruits and roots that grew wild in the forests. At the same time, wild barleys, wheats and ryes made their appearance in the grasslands, and there is evidence that, from around 11,000 BCE, these

made their way for the first time into the diet of the people living in Abu Hureyra on the banks of the Euphrates in present-day Syria. However, at this time, there is no evidence of these species being cultivated, and the lifestyle of the local population was clearly one of hunting-gathering. This is almost exactly the same time from when we have the earliest discovered burnt rice grains in the Lahuradewa region, where the onset of slash-and-burn agriculture seems to go back at least a further two millennia.

Then, against the grain around 10,000 BCE, there was an abrupt regression to a colder climate, and the time of plenty came to an end. This cold phase, called the Younger Dryas, caused the grasslands to retreat, and reduced the availability of the wild plants like pistachio, almond and wild fruits, that had provided ready food for the hunter-gatherers, forcing them to look for greater food security by harnessing the cereals that were growing in the wild.

Around 10,000 BCE, the first evidence of plant cultivation and livestock appears in the Ghab Valley in Northwest Syria. Around 9000 BCE we have evidence of the use of fire to systematically clear large swathes of the oak forests for agriculture.

The contrast with the subcontinent is very sharp. Whereas in the subcontinent, agriculture began as a spontaneous enterprise as soon as the climate turned conducive, a sudden, sharp glacial spell is needed to force a resort to plant domestication for food security in the FC. Better preservation means that there is earlier evidence (9th millennium BCE, to be precise) of crop “packages” comprising cereals, legumes and fruits in the FC than is available from the subcontinent, such as in Jhusi. However, that itself does not substantiate the “accepted view” that agriculture arrived in India from the west. Indeed, if one weighs the archaeological evidence properly and looks closely at the process of development of agriculture itself, the opposite appears the more logical conclusion.

Contrary to what we have been made to believe by our textbooks, the dates for the onset of agriculture in the FC – and indeed every stage of development – are at least two millennia later than those on the subcontinent, as described above. This is the inevitable result of the differences in climate in the two regions. Given the relatively abrupt appearance of cultivation practices in the FC, is it unreasonable to ask if agriculture may have actually come to the FC from India? After all, the subcontinent not only had an older agricultural tradition, but had also developed a diverse crop record to suit a range of climates much earlier, as can be seen from the Horton Plains. It is not necessary for crops themselves to have spread from one region to another, although that may inevitably have happened over time. Wild varieties of barley and wheat were probably native to both regions, and each region cultivated local varieties. However, India, with its clear head start, could have provided the FC with the knowhow for cultivating the right type of crops that could provide food security in the harsh Younger Dryas, which caught the so-called “cradle of civilisation” napping. The wild legumes and lentils that the hunter-gatherers of Abu Hureyra relied on for food, for instance,

vanished completely for many centuries, and wild ryes and wheats dropped sharply, as they became unavailable in the cold weather, inspite of the fact that Abu Hureyra was one of the best-provided areas in terms of plants as well as animals that could be exploited for food. When domestication of wheats and ryes started here in the Dryas, and the legumes made their return, the grasslands could not have been re-established. Before the onset of the Dryas, given the easy availability of wild fruits, roots and tubers, wild grains were probably not a major source of food. So how did this leap in agriculture from an almost non-existent baseline happen in a hostile climate? The Horton Plains dwellers would have started agriculture from nothing too, but theirs had clearly been a conscientious endeavour to exploit a favourable climate. Could an external stimulus have helped the Abu Hureyra hunter-gatherers, and other communities like theirs elsewhere in the FC, find their feet?

An indication, if not an outright answer, is provided by the history of domestication of the grape (

Vitis vinifera). It is

commonly believed that the grape was domesticated around 7000 years ago somewhere in the South Caucasus, from where it spread all over the FC, and reached Egypt and Europe around 5000 years ago. As usual, the archaeological evidence from India is ignored. As mentioned above, grape has been found among other crops from the Neolithic period dating back to at least 8000 years ago

at Jhusi. It is possible this early Indian cultivar may have died out, but without even factoring the archaeological evidence in, India cannot now be ruled out as the home of the grape, in which case, we would have a Neolithic-era spread of a crop from India to the FC and beyond.

The history of agriculture in India dates back to the 16th millennium BCE, when it started as a spontaneous endeavour to exploit the onset of favourable climate. Interestingly, the domestication of bovine species started near-simultaneously. Thus, the traditional strong connection between cattle-rearing and cultivation of crops is as old as the start of agriculture itself. This phenomenon is repeated in the Mehrgarh Neolithic, where the native Bos indicus appears to have predominated over the rearing of goats and sheep, implying continuity in agricultural practices in the subcontinent over several millennia even from this early time. New and significant findings continue to deepen our understanding of its origins and evolution, and may eventually turn the long-held and often-repeated theories of agriculture having arrived in India from the Fertile Crescent in the Near East, on their head.

The author is grateful to Dr. Biswajeet Thakur, Scientist, Birbal Sahni Institute of Palaeosciences, Lucknow, for insightful comments. Views expressed are the author’s own.

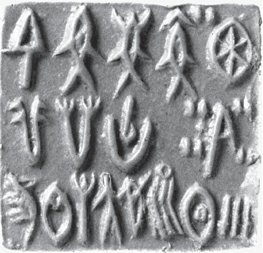

https://www.scribd.com/document/435587301/Spread-of-Agriculture-in-EastAsia-StevensFuller2017 ![No photo description available.]() Seal discovered in Cholistan (near Ganweriwala). Surface find. https://blog.travel-culture.com/2012/02/07/rare-indus-seal-discovered-at-archeological-site-in-cholistan/

Seal discovered in Cholistan (near Ganweriwala). Surface find. https://blog.travel-culture.com/2012/02/07/rare-indus-seal-discovered-at-archeological-site-in-cholistan/ Seal discovered in Cholistan (near Ganweriwala). Surface find. https://blog.travel-culture.com/2012/02/07/rare-indus-seal-discovered-at-archeological-site-in-cholistan/

Seal discovered in Cholistan (near Ganweriwala). Surface find. https://blog.travel-culture.com/2012/02/07/rare-indus-seal-discovered-at-archeological-site-in-cholistan/

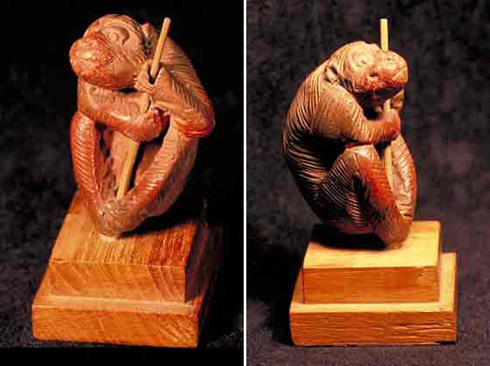

Terracotta toy monkeys, Mohenjo-daro

Terracotta toy monkeys, Mohenjo-daro

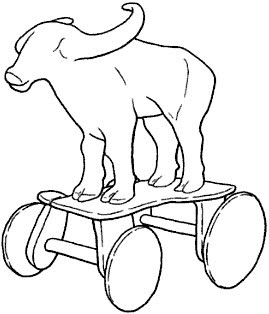

Sculpture of a rhinoceros 19 cm high and 25 cm long standing on two horizontal bars, each attached to an axle of two solid wheels.

Sculpture of a rhinoceros 19 cm high and 25 cm long standing on two horizontal bars, each attached to an axle of two solid wheels.

See decipherment at:

See decipherment at:

Aerial photograph of the "Great Bath," at the centre of the citadel of Harappa .The round stucture to the left of the bath is the well.

Aerial photograph of the "Great Bath," at the centre of the citadel of Harappa .The round stucture to the left of the bath is the well.

Cemetery IV - Grave and detail of headband

Cemetery IV - Grave and detail of headband Grave of cemetery 9 at Mehrgarh showing the remains of the wall sealing the pit as well as a basket offering.Copper beads were found around the waist of the skeleton,in which the remains of a cotton thread were identified.

Grave of cemetery 9 at Mehrgarh showing the remains of the wall sealing the pit as well as a basket offering.Copper beads were found around the waist of the skeleton,in which the remains of a cotton thread were identified.

The Symbol contained within the 'Ensign of the Rising Sun of Mehrgarh' is taken from Faiz Mohammed greyware excavated in Mehrgarh.Viewed as a helicon, the four quadrants that constitute the ensign are interpreted to represent the four provinces.

The Symbol contained within the 'Ensign of the Rising Sun of Mehrgarh' is taken from Faiz Mohammed greyware excavated in Mehrgarh.Viewed as a helicon, the four quadrants that constitute the ensign are interpreted to represent the four provinces.

Ziggurat. Mohenjo-daro.

Ziggurat. Mohenjo-daro.

The person in the middle with elephantine legs is holding back two elephantsdraped in dotted circles scarf. karibha, ibha'elephant' rebus: karba, ib'iron' PLUS

The person in the middle with elephantine legs is holding back two elephantsdraped in dotted circles scarf. karibha, ibha'elephant' rebus: karba, ib'iron' PLUS

Ornamental beads from 2300 BC found in Rakhigarhi show the high level of craftsmanship during the Harappan era. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

Ornamental beads from 2300 BC found in Rakhigarhi show the high level of craftsmanship during the Harappan era. Photo: Priyanka Parashar/Mint

A plate of the Kulli Culture in Balochistan.

A plate of the Kulli Culture in Balochistan.

Mehrgarh Period VII, c. 2800-2600 BCE

Mehrgarh Period VII, c. 2800-2600 BCE

Pirak:terracotta figurines of horses and riders (1800 BC) © C. Jarrige

Pirak:terracotta figurines of horses and riders (1800 BC) © C. Jarrige

By 1,500 BC the population of the Indus Valley was creating moulds for metal and terracotta ornaments. Gold jewellery from these civilizations also consisted of bracelets, necklaces, bangles, ear ornaments, rings, head ornaments, brooches, girdles etc. Here, the bead trade was in a full swing and they were made using simple techniques.

By 1,500 BC the population of the Indus Valley was creating moulds for metal and terracotta ornaments. Gold jewellery from these civilizations also consisted of bracelets, necklaces, bangles, ear ornaments, rings, head ornaments, brooches, girdles etc. Here, the bead trade was in a full swing and they were made using simple techniques. Wide shell bangles, each made from a single conch shell (Turbinella pyrum) found at Harappa.

Wide shell bangles, each made from a single conch shell (Turbinella pyrum) found at Harappa.

Shell works excavated from Balakot

Shell works excavated from Balakot

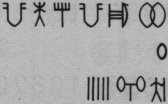

The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan (ASI 1987, Sign 51)

The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan (ASI 1987, Sign 51)  Nindowari seal 1

Nindowari seal 1

Herringbone pattern.

Herringbone pattern.

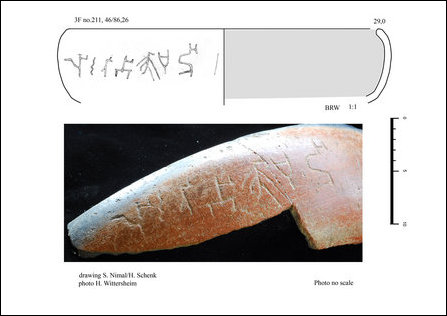

Rajanpur surface find tablet. Rajanpur is 70 km. northeast of Harappa.

Rajanpur surface find tablet. Rajanpur is 70 km. northeast of Harappa.

Mohenjo-daro

Mohenjo-daro