The Making of Early Kashmir: Landscape and Identity in the Rajatarangini by Shonaleeka Kaul is available for purchase on Amazon.

![]()

![]()

Sanskrit, the most defining characteristic of Indic civilization, is not just a language. It is a cultural phenomenon. It is the common thread which runs throughout the Indic cultural sphere.

To common Hindus it has always been an object of reverence. She has been worshipped as a goddess and is a living reality in the home of every practicing Hindu. Even while most of the Hindus can no longer understand or speak Sanskrit, it is very firmly a part of their lives in the daily mantras, stotrams and scriptures that they recite.

To the elite, in past two hundred years, it has come to mean different things. The masses have come to cherish and uphold Sanskrit and the cultural values that come with it. The deracinated elite of India has come to regard Sanskrit as a Brahmanical tool of oppression, a source of hegemony, oppression and even racism; the most potent tool with which the evil Hinduism enslaved millions.

So what is Sanskrit? Is it just a language or a cultural phenomenon? Is it a cultural unifier or a political power of enforcing hegemony? A new book, ‘The Making of Early Kashmir: Landscape and Identity in the Rajatarangini’ tries to answer some of these questions… and then some. [1]

The choice of subject in The Making of Early Kashmir is very specific. Kaul delves into debates like that of the relationship of ‘cosmopolitan’ Sanskrit with the vernacular, of Sanskritization vs. regionalization; centre vs. periphery etc. through her analysis of the great Kashmiri classic the Rajatarangini by Kalhana. In the course of her book she demolishes three false binaries created over time by Indologists.

‘Historical’ vs. ‘Didactic’

Kaul begins by reflecting on the historiography and textual criticism of the Rajatarangini over centuries by discussing the works of European scholars like Harold H. Wilson, Georg Buhler and Marcus Aurel Stein and then Indologists such as A. L. Basham and even R. C. Majumdar.

The Rajatarangini became a pivot on which the discussions about Indians and their sense of history revolved. While most of Indian scriptures were discarded as myth and useless to a historian for all practical purposes, Kalhana’s Rajatarangini was established as perhaps the sole exception to the rule. It had, quite surprisingly, a sense of history which fit the European criteria.

Having declared Rajatarangini as a text having a ‘sense of history’, these Indologists then had to excise those parts of the text which did not fit this notion. Kaul discusses how this characterization of Indians and Rajatarangini had its own problems. There were some “aspects of the text that did not fit their idea of what history should be – aspects which they then had to disown and describe as ‘failings’ and ‘imperfections’.” [Kaul, 18]

Like the nineteenth century German Indologists who picked apart the Mahabharata and the Gita, separating their ‘pantheism’ from ‘polytheism’, their ‘animism’ from ‘proto-monotheism’, these Indologists also fragmented the Rajatarangini into the ‘historical’ and the ‘didactic’, between ‘poetry’ and ‘history’.

Considering the basic character of the text to be historical, they had to declare the ‘rhetorical’ and the ‘didactic’ parts as ‘failings’ and ‘imperfections’. Kalhana’s implicit faith in the Puranic genealogy led Majumdar and Basham to declare that ‘the first three tarangas were less credible than the last five’. [Kaul, 18]

“Philologists and historians who dominated the study of the Rajatarangini thus ended up fragmenting it, setting up some parts of it against other parts, as it were, obfuscating rather than elucidating the nature of the text as a whole. Moreover, all aspects of figuration proper to a poetic discourse were deemed extraneous and detrimental to the essentially ‘historical’ substance and intent of Kalhana’s enterprise that were presumed antithetical to the poetic.” [Kaul, 19]

In absence of any indigenous modern exposition on Rajatarangini, this discourse which touted the Rajatarangini as the sole example of Indian sense of history, albeit with imperfections, became the norm, leading scholars of one tradition after other to follow in the footsteps of 19th century Indologists. Kaul names this the ‘history hypothesis’.

Kaul considers the history hypothesis as easily refutable and even self-contradictory. She argues that this opposition between history and poetry is flawed. The myths in the text are not ‘failings’… “far from being a lapse in critical judgement, their inclusion served a purposive, didactic function which was crucial in the text’s scheme of things.” [Kaul, 24]

Discarding this false binary between kavya and history Kaul says that ‘the Rajatarangini was indeed a kavya first, and thereby perhaps history.’ [Kaul, xi] She also believes that ‘ethics is the fulcrum of Kalhana’s literary and historical vision’. Like Vishwa Adluri, she objects to the textual surgery that Indologists and modern scholar have performed on various Indian texts in the past 200 years. Contrary to being peripheral and corrupting influence on the Rajatarangini, she believes that the ‘moral’, ‘rhetorical’ and the ‘didactic’ was central to the Rajatarangini.

“I identify that organizing principle, which brings an order of meaning to the sprawling account, as a model of orthopraxis or righteous conduct according to which Kalhana classifies and narrativizes – not just narrates – Kashmiri kings from the earliest till the poet’s own time.” [Kaul, 10-11]

The history hypothesis lauds the Rajatarangini for having a sense of history and then criticizes it for its imperfections; for being not quite up to the mark. It fragments the text into two hostile camps. What Kaul proposes, in the line of the native tradition, to see the text in its unity:

“I therefore urge reclaiming the poem from the hegemonic but troubled understanding of it as history – only to perhaps restore it ultimately to a more integral notion of historicity that is sensitive to the literary, is internally consistent, and is true to the contents of the text rather than to the externally levied criteria. One way to do this is to rehabilitate the text to its original literary culture and invest in its vision. In other words, to view the text as what it itself claims and proves to be, namely a kavya. Kavya is highly aesthetic poetry or prose (including drama) characterized by the use of indirect and figurative language (vakrokti, alamkara) and the evocation of essentialized emotional states (rasa).” [Kaul, 29]

‘Cosmopolitan’ vs. ‘Vernacular’

The second misconception about Kalhana that Kaul deconstructs is the Pollock’s binary of cosmopolitan vs. the vernacular; of regional vs. trans-regional. Pollock claims that Sanskrit literature has always aimed for religious and political centralization; in which national and pan-Indian paradigms, metaphors and symbols have sought to suppress the regional and vernacular cultures. He envisions a history of India in which the centralizing power of Aryans, governed by the malicious combine of Brahmins and Kshatriyas, suppressed the expression of vernacular literature and idiom and oppressed regional cultures. In other words, he posits ‘Sanskrit hegemony’ not unlike a colonial power imposing itself on unwilling and oppressed hordes of conquered natives.

Kaul shows us something which should be obvious to all of us but strangely isn’t: The Rajatarangini is a regional (vernacular) account of Kashmir, and it is written in a trans-regional (cosmopolitan) language, Sanskrit. This tiny bit of fact destroys Pollock’s cosmopolitan vs. vernacular binary.

“Sanskrit mediates Kashmir’s rise to region hood. It points to how, by all accounts and traces, the birth of Kashmir as Kashmir was performed and attended on by Sanskritic culture. In other words, Kashmir emerges on the discursive horizons of history with self-awareness as a land and a people – Sanskrit. So much so that till today the Kashmiri names of places in the Valley are clearly derivatives of their Sanskrit names mentioned in the Rajatarangini 900 years ago, displaying a remarkable persistence of culture despite the odds.” [Kaul, 159-160]

Not only this, there is no vernacular account of Kashmir since the Rajatarangini until the 17thcentury. It is a Sanskrit chronicle which creates the regional consciousness of Kashmir. Far from being an oppressive hegemonic force, Sanskrit became a vehicle of shared communication between Kashmiris of different times and between Kashmiris and other peoples of India. “The language appears to have been an instrument less of hegemonization and more of a shared communication.” [Kaul, 161]

Pollock argues that beginning from somewhere around 200 CE, the process of regionalization in Indian politics began with dialects developing into literary languages, creating vernacular literature, in opposition to the hegemonic power of Sanskrit which started to wane after this period. Denying this, Kaul says that “this did not quite happen in Kashmir”. [Kaul, 61] Kaul believes that the models revolving around centre-periphery, cosmopolitan-vernacular debates are essentially colonialist in origin and behavior and should be abandoned in an age of post-colonialism:

“…the macro argument of this book would also be the one that calls for abandonment of the essentially colonialist model of centre-periphery or its variants such as borderland and frontier, and their evolutionist conceptual adjuncts such as acculturation, to explain Kashmir’s development. Binaries and hierarchies are never enough to think about complex spaces, especially lived ones. A model of cultural flows is proposed in this book as the more suitable alternative… The local and the universal, the vernacular and the pan-Indic appear as but different registers of expression for Kashmir.” [Kaul, 161-162]

Kaul explains that dialectic world of binaries in which one worldview and approach is diametrically opposed to another is an insufficient model to understand Kashmir in particular and even other times and places in general. Cultures rarely see themselves in neatly organized ideologies opposed to each other. Instead many currents and undercurrents run which do not necessarily contradict each other. In fact reading the Rajatarangini proves that the regional and the trans-regional are not enemies but have enriched each other.

“In what may be described then as a diglossic identity, the regional is hardly expropriated by the trans-regional. Instead there is a need to appreciate that societies have always been constituted by their involvements in more extensive networks.” [Kaul, 163]

‘Centre’ vs. ‘Periphery’

The third false binary that Kaul dissects is that of ‘centre’ vs. ‘periphery’. Most of the Western and western-influenced Indian scholarship of Sanskrit texts maintain that these texts were little more than tools of ‘acculturation’. It was the evil Brahmins, who imposed the Aryan civilization upon the unsuspecting tribal and regional cultures of the sub-continent through a process of Sanskritization and Brahmanization in order to bring these peripheral cultures into the ‘main-stream civilization’.

This theory argues that Sanskrit was not just a language of a refined culture, but a tool for suppression, an instrument of cultural hegemony, and a device for wielding political power. This theory has become stock in trade in not just the western but Indian academic circles. Words and phrases like centre-periphery, hegemony, legitimation, acculturation and Sanskritization “have become gate-keeping concepts thought to apply to every regional process, perhaps limiting thereby the full potential for apprehending what was in fact a complicated compound of local realities.” [Kaul, 102]

This binary creates artificial but dangerous fault lines, not only in the study of Sanskrit texts but also on ground. It seeks to divides Brahmins from the rest; north Indians from south Indians; tribals from sedentary people; nomads from agriculturalists. It has resulted in violent clashes on ground. These academic binaries have actually resulted in bloody battles on ground, battles which would not have taken place had it not been for this faulty scholarship which seeks to divide one part of Indian society from the other.

These scholars claim Kashmir as a classic case of a peripheral regional power lying at the crossroads of cultures and civilizations and which was at best only nominally connected to the center of ‘India’. It was only later that the Sanskrit hegemony ‘acculturated’ Kashmir into its own fold. Kashmir is seen as a quintessential borderland.

Kaul claims that if there is one cultural paradigm which has always defined Kashmir, then it is not Hellenistic, Iranian or Tibeto-Burman, but it is Indic. And it was not a one-way traffic. Indic culture learned as much from Kashmir as Kashmir learned from it. By attracting our attention to the people, places, food and habits discussed in the Rajatarangini, Kaul shows that Kashmir was in constant contact with all the major regions of Indic culture and civilization and not just with the ‘Sanskrit metropolis’. Assam, Bihar and Bengal feature as much in the text as do the nearby Jammu, Chamba and Kangra.

Coins were found in Kashmir of various regions and times. People of all sorts from all corners of India visited Kashmir. Similarly Kashmiris visited a wide variety of places. Through various such examples taken from language, culture, art, sculpture and from the Rajatarangini, Kaul demonstrates that Kashmir was integral to Indic culture by its cultural, social and political connection to the rest of India.

Kaul does not find any evidence of ‘Sanskritization’. Rather she finds that Kashmiri influenced Sanskrit and other languages as much as it got influenced by them.

“Linguistically as well, we are looking at something of a horizontal continuum. The continuum extends, however, not only with Sanskrit but also, not surprisingly, between Kashmiri and Pahari, Kashmiri and Punjabi, and Kashmiri and Dogri, that is, with other IA dialects that fade in and out of the bordering areas of the Valley adjoining Himachal, Punjab, and Jammu, respectively.” [Kaul, 142]

Even archaeology proves that the pre-historic culture of Kashmir was remarkably similar to that of Harappa and many other cities of the Saraswati River Valley in Haryana and adjacent places. Comparing sculptural art from Kashmir to various other places in north India, she arrives at the same conclusion. As a fitting end to a brilliant enquiry, demolishing the third false binary that has been dividing and breaking India into artificial fault lines, Shonaleeka Kaul says that:

“Kashmir emerges to be… a periphery in no sense whatsoever. Nor does it appear as a cultural crossroads; the impress of the Indic cultural regime on the landscape is undeniable…”

Shonaleeka Kaul’s The Making of Early Kashmir: Landscape and Identity in the Rajatarangini is a work, not to be missed by either the expert or the layman.

REFERENCES

- Kaul, Shonaleeka. The Making of Early Kashmir: Landscape and Identity in the Rajatarangini. New Delhi: Oxford, 2018. p. xi.

Featured Image: Amazon, Indian Women Blog

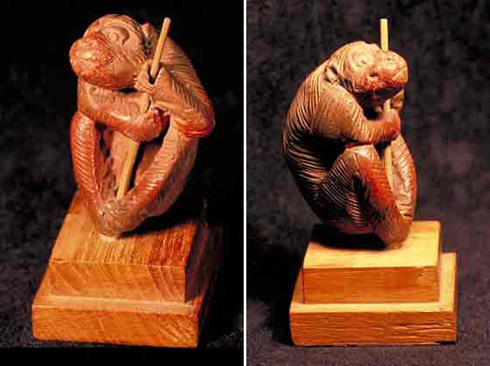

Terracotta toy monkeys, Mohenjo-daro

Terracotta toy monkeys, Mohenjo-daro

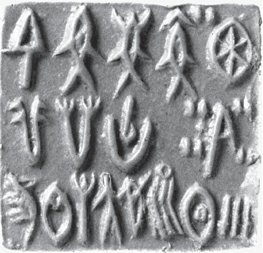

Combined animal heads on a bovine body. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Combined animal heads on a bovine body. Mohenjo-daro seal.

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate.

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate. "Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum, described as "one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period [2350–2170 BCE]. . . . The decoration, which is characteristic of the Agade period, shows two buffaloes that have just slaked their thirst in the stream of water spurting from two vases held by two naked kneeling heroes." It belonged to Ibni-Sharrum, the scribe of King Sharkali-Sharri, who succeeded his father Naram-Sin. The caption cotinues: "The two naked, curly-headed heroes are arranged symmetrically, half-kneeling. They are both holding vases from which water is gushing as a symbol of fertility and abundance; it is also the attribute of the god of the river, Enki-Ea, of whom these spirits of running water are indeed the acolytes. Two arni, or water buffaloes, have just drunk from them. Below the scene, a river winds between the mountains represented conventionally by a pattern of two lines of scales. The central cartouche bearing an inscription is held between the buffaloes' horns." The buffalo was known to have come from ancient Indus lands by the Akkadians."

"Cylinder Seal of Ibni-Sharrum, described as "one of the most striking examples of the perfection attained by carvers in the Agade period [2350–2170 BCE]. . . . The decoration, which is characteristic of the Agade period, shows two buffaloes that have just slaked their thirst in the stream of water spurting from two vases held by two naked kneeling heroes." It belonged to Ibni-Sharrum, the scribe of King Sharkali-Sharri, who succeeded his father Naram-Sin. The caption cotinues: "The two naked, curly-headed heroes are arranged symmetrically, half-kneeling. They are both holding vases from which water is gushing as a symbol of fertility and abundance; it is also the attribute of the god of the river, Enki-Ea, of whom these spirits of running water are indeed the acolytes. Two arni, or water buffaloes, have just drunk from them. Below the scene, a river winds between the mountains represented conventionally by a pattern of two lines of scales. The central cartouche bearing an inscription is held between the buffaloes' horns." The buffalo was known to have come from ancient Indus lands by the Akkadians."  m0295 Pict-61: Composite motif of three tigers (Mahadevan concodance)Location: Mohenjo Daro, Larkana Dt., Sind, Pakistan Site: Mohenjo Daro Monument/Object: carved sealCurrent Location: National Museum, New Delhi, India Subject: interlinked tigers Period: Harappa/Indus Civilization (Pakistan) (3300-1700 BCE) Date: ca. 2100 - 1750 BCE Material: stone Scan Number: 27412 Copyright: Huntington, John C. and Susan L. Image Source: Huntington Archive

m0295 Pict-61: Composite motif of three tigers (Mahadevan concodance)Location: Mohenjo Daro, Larkana Dt., Sind, Pakistan Site: Mohenjo Daro Monument/Object: carved sealCurrent Location: National Museum, New Delhi, India Subject: interlinked tigers Period: Harappa/Indus Civilization (Pakistan) (3300-1700 BCE) Date: ca. 2100 - 1750 BCE Material: stone Scan Number: 27412 Copyright: Huntington, John C. and Susan L. Image Source: Huntington Archive

The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is

The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is

h419

h419 eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop.

eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop.

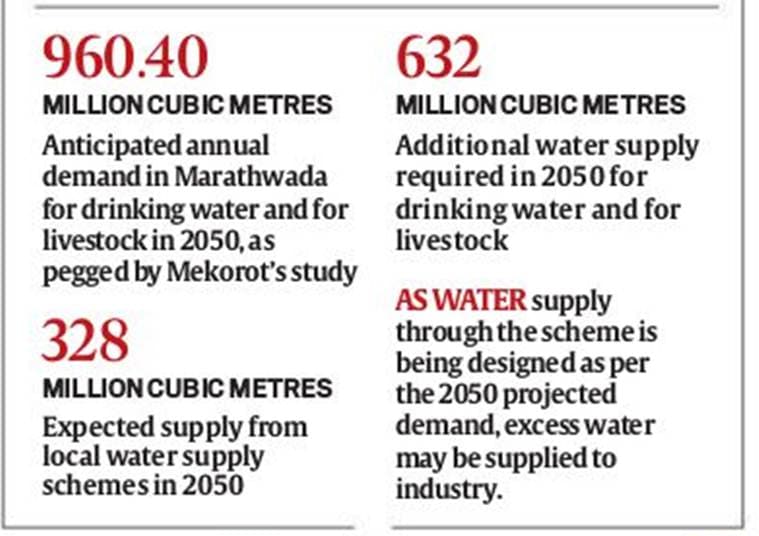

Water scarcity in the region is acute — while large parts of western Maharashtra reeled under floods last week, over 250 villages in Marathwada continued to receive water through tankers. (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)

Water scarcity in the region is acute — while large parts of western Maharashtra reeled under floods last week, over 250 villages in Marathwada continued to receive water through tankers. (Express Photo by Amit Chakravarty)