https://tinyurl.com/yyktjqpp

-- pasār, pahārā, bazaar of Mohenjo-daro identified. Each circular artisan platform in Harappa is kole.l 'smithy, forge, temple'; Lajjā Gaurī (1st cent., Padri) signifies tāmarasa kóśa Indus Script hypertext, metalwork treasure

--Series of circular platforms in Harappa are a Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization bazaar, Lajjā Gaurī signifies Aditi, Devatā Ātmā (RV X.125), Indus Script hieroglyphs, metalworker's professional calling card

-- Archaeological evidence for the earliest bazaar of the world and veneration of Lajja Gaurī in Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization

-- Why does Lajjā Gaurī on a slate plaque found in Padri carry a lotus bud a a hieroglyph on her left hand?

-- Why is Lajjā Gaurī divinity shown as a headless woman, but with the lotus above the neck as a hieroglyph, vulva exposed?

-- Each of the circular workers' platforms may have held in the centre, a thã̄bh kole.l 'pillar temple' rebus signifier: tāmbā kole.l 'copper smithy.forge'.

-- Archaeological evidence for the earliest bazaar of the world is in a Meluhha word pahārāʻgoldsmith's workshopʼ, thanks to decipherment of Indus Script inscriptions on 1) Mohenjo-daro storage pot & 2) Susa pot with cargo received from Meluhha

-- Archaeological evidence of a Mohenjo-daro brick room with conical pits lined with wedge-shaped bricks

-- Mohenjo-daro brick room with conical pits is pasār, pahārā 'metals bazaar or market' of Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization

-- Like copper anthropomorphs which are lapidary-smith-merchant professional calling cards, Lajjā Gaurī plaques are professional calling cards of metalworkers proclaiming their metallurgical competence related to working in gold and copper.

-- Evidence provided by Đinh Hồng Hải (2016) on the Lajjā Gaurī tradition of Cham people in Vietnam is appended (with a Google translation from his Vietnamese monograph)

This monograph provides Archaeological evidence for the earliest bazaar of the world in Mohenjo-daro; and explains why Lajjā Gaurī is venerated in Padri pahārā ʻgoldsmith's, coppersmith's workshop'. The name of the divinity is a signifier of the colour of copper/gold: गौर mf(/ई)n. (in comp. or ifc. g. कडारा*दि) white , yellowish , reddish , pale red RV. x , 100 , 2 TS. v &c (Monier-Williams) लाजाहोम lājāhōma m S A burnt-offering at weddings of लाजा or लाह्या to secure the bridegroom and bride from forsaking each other.(Marathi)

I submit that the Lajjā Gaurī plaque found in Padri is a professional calling card with a Meluhha message in Indus Script Cipher, of a metalsmith smelter because the orthography on the plaque signifies Indus Script hieroglyphs:

Lotus bud: tāmarasa kóśa 'lotus bud' rebus: तामरस कोश 'gold/copper treasure'.

कोश 'the vulva' rebus: कोश--वत् possessing treasures , rich , wealthy. Sun's rays: अंशुः read rebus ancu ‘iron’ (Tocharian);

अंशुः is a synonym of Soma. E.g., खर-अंशुः ‘sun’s rays’ rebus: khār ancu ‘blacksmith, iron’. On some Lajjā Gaurī sculptural representations (e.g. Amaravati sculptures), the head of the squatting divinity is replaced by a lotus flower. I submit that this is a semantic determinative of the rebus reading: tāmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tāmarasa 'gold, copper'. Lajjā Gaurī , the mother is Aditi, the ātmā devatā venerated in Devi Sūktam RV X.125. See:

A prayer to wealth givers, Rāṣṭrī Sūktamअहम् राष्ट्री संगमनी वसूनाम् I am the mover of nation's wealth: देवता आत्मा, ऋषिका वाक् आम्भृणी (RV 10.125) https://tinyurl.com/ybt5sas4

A monograph reconstructs two ancient Meluhha (Indian sprachbund, 'language union') expressions which signify wealth-accounting for a nation by merchant-/artisan-guilds of Sarasvati Civilization. Cognates of the word khār has two meanings: 1. blacksmith; 2. खर-अंशुः the sun. अंशुः is a synonym of Soma and is cognate with ancu.'iron' (Tocharian). The processing of Soma or अंशुः is the central, sacred metaphor of R̥gveda.

Etymology of Khar from Sanskrit "Svar", meaning Sun, which changes in northwestern Indian languages to "Khar". खर khara खर a. [opp. मृदु, श्लक्ष्ण, द्रव) 1

Hard, rough, solid-Comp. खर-अंशुः, -करः, -रश्मिः the sun (Apte). खर--मयूख = खरा* ंशु "hot-rayed" , the sun (धूर्तनर्तक)(Monier-Williams)

![Image result for gold pectoral bharatkalyan97]()

![Image result for gold pectoral bharatkalyan97]() m1656 Pectoral. Gold Pendant. Harappa. National Museum, New Delhi

m1656 Pectoral. Gold Pendant. Harappa. National Museum, New Delhi

Sun's rays arka 'sun, rays of sun' rebus: arka 'copper, gold' eraka 'moltencast'.

खार (= खार् (L.V. 96, K.Pr. 47, Śiv. 827) । द्वेषः m. (for 1, see khār 1), a thorn, prickle, spine (K.Pr. 47; Śiv. 827, 1530)(Kashmiri) A خار ḵẖār, s.m. (2nd) A thorn, a thistle, a bramble. 2. A spike, a splinter. Pl. خارونه ḵẖārūnah. خار دار ḵẖār-dār, adj. Thorny, barbed, troublesome. خار ګیري ḵẖār-gīrī, s.f. (3rd) A fence, a temporary defence made of thorns. Pl. ئِي aʿī. See اغزن (Pashto)

Hieroglyph 2: खार khāra 'squirrel'; खारी khārī f (Usually खार) A squirrel. (Kashmiri)

Rebus: khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार ; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन् , which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.). This word is often a part of a name, and in such case comes at the end (W. 118) as in Wahab khār, Wahab the smith (H. ii, 12; vi, 17). khāra-basta खार-बस्त । चर्मप्रसेविका f. the skin bellows of a blacksmith. -büṭhü -ब॑ठू॒ । लोहकारभित्तिः f. the wall of a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -bāy -बाय् । लोहकारपत्नी f. a blacksmith's wife (Gr.Gr. 34). -dŏkuru -द्वकुरु॒ । लोहकारायोघनः m. a blacksmith's hammer, a sledge-hammer. -gȧji -ग॑जि॒ or -güjü -ग॑जू॒ । लोहकारचुल्लिः f. a blacksmith's furnace or hearth. -hāl -हाल् । लोहकारकन्दुः f. (sg. dat. -höjü-हा॑जू॒ ), a blacksmith's smelting furnace; cf. hāl 5. -kūrü -कूरू॒ । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter. -koṭu -क॑टु॒ । लोहकारपुत्रः m. the son of a blacksmith, esp. a skilful son, who can work at the same profession. -küṭü -क॑टू॒ । लोहकारकन्या f. a blacksmith's daughter, esp. one who has the virtues and qualities properly belonging to her father's profession or caste. -më̆ʦü 1 -म्य॑च़ू॒ । लोहकारमृत्तिका f. (for 2, see khāra 3), 'blacksmith's earth,' i.e. iron-ore. -nĕcyuwu-न्यचिवु॒ । लोहकारात्मजः m. a blacksmith's son. -nay -नय् । लोहकारनालिका f. (for khāranay 2, see khārun), the trough into which the blacksmith allows melted iron to flow after smelting. -ʦañĕ -च़्ञ । लोहकारशान्ताङ्गाराः f.pl. charcoal used by blacksmiths in their furnaces. -wān वान् । लोहकारापणः m. a blacksmith's shop, a forge, smithy (K.Pr. 30). -waṭh -वठ् । आघाताधारशिला m. (sg. dat. -waṭas -वटि ), the large stone used by a blacksmith as an anvil. khār 2 खार् or khwār ख्वार् । दरिद्रीभूतः adj. c.g. poor, distressed, become poor, reduced to poverty; deserted, abandoned, friendless, wretched (Śiv. 421, Rām. 1697); abject, vile, base, contemptible (cf. khārakhas) (K.Pr. 247); ruined, desolate (El.); ruined, destroyed, spoiled (K.Pr. 248, Rām. 1380-1); distraught, full of anxiety or sorrow (Rām. 1623). --gōmotu --गोम॑तु॒ । दारिद्र्यमापन्नः perf. part. (f. -gömüʦü -गा॑म॑च़ू॒ ), become poor; become contemptible, despised, despicable (YZ. 486); become distressed, become full of anxiety or sorrow, distraught (Rām. 1463, 1665); etc., as ab. --karun --करुन् । दुःखितीकरणम् m.inf. to reduce a person to distress or poverty (e.g. by unkindness, by robbing him, or by seducing him to profligacy) (Rām. 1386, 1481); to make despised, bring to contempt (YZ. 37, 568); to ruin, destroy (Rām. 1380). --ta kharāba --त खराब । अतिदुर्गतः adj. c.g. reduced to the greatest straits, greatly distressed (by loss of livelihood); reduced to distress (by disease), etc. (Kashmiri)

svar स्वर् ind. 1 Heaven, paradise; as in स्वर्लोक, स्वर्वेश्या, स्वर्भानुः, &c.; त्वं कर्मणां मङ्गलमङ्गलानां कर्तुः स्म लोकं तनुषे स्वः परं वा Bhāg.4.6.45. -2 The heaven of Indra and the temporary abode of the virtuous after death. -3 The sky, ether. -4 The space above the sun or between the sun and the polar star. -5 The third of the three Vyāhṛitis, pronounced by every Brāhmaṇa in his daily prayers; see व्याहृति. -6 Radiance, splendour. -7 Water. ind. (used in nom., acc., gen., or loc. case); स्वलंकृतैर्भ- वनवरैविभूषितां पुरंदरः स्वरिव यथामरावतीम् Rām.7.11.5; साधोरपि स्वः खलु गामिताधो गमी स तु स्वर्गमितः प्रयाणे N.6. 99 (herein abl. case, स्वर् = स्वर्गात्). -Comp. -अतिक्रमः reaching Vaikuṇṭha (beyond heaven). -आपगा, -गङ्गा 1 the celestial Ganges. -2 the galaxy or milky way. -इङ्गणः a strong wind. -गत a. dead. -गतिः f., -गमनम् 1 going to heaven, future felicity. -2 death. -गिरिः Sumeru. -जित् m. a kind of sacrifice; यजेत वाश्वमेधेन स्वर्जिता गोसवेन वा Ms.11.74. -तरुः (स्वस्तरुः) a tree of paradise. -दृश् m. 1 an epithet of Indra. -2 of Agni. -3 of Soma. -धुनी, -नदी (forming स्वर्णदी) the celestial Ganges; सद्यः पुनन्त्युपस्पृष्टाः स्वर्धुन्यापोनुसेवया Bhāg.1.1.15. -भानवः a kind of precious stone. -भानुः Name of Rāhu; तुल्ये$पराधे स्वर्भानुर्भानुमन्तं चिरेण यत् । हिमांशुमाशु ग्रसते तन्म्रदिम्नः स्फुटं फलम् Ś.i.2.49. ˚सूदनः the sun. -मणिः the sun. -मध्यम् the central point of the sky, the zenith. -यात a. dead. -यातृ a. dying. -यानम् dying, death. -योषित a celestial woman, apsaras. -लोकः the celestial world, heaven. -वधूः f. a celestial damsel, an apsaras. -वापी the Ganges. -वारवामभ्रू (see -वधू above); स्वर्वारवामभ्रुवः नृत्यं चक्रुः Cholachampū p.22, Verse 51. -वेश्या 'a courtezan of heaven', acelestial nymph, an apsaras. -वैद्य m. du. an epithet of the two Aśvins. -षा 1 an epithet of Soma. -2 of the thunderbolt of Indra. -सिन्धु = स्वर्गङ्गा q. v. (Apte)

sanskritdictionary.com/svar/35038/4

खरडा kharaḍā m (खरडणें) Scrapings (as from a culinary utensil). 2 Bruised or coarsely broken peppercorns &c.: a mass of bruised मेथ्या &c. 3 also खरडें n A scrawl; a memorandum-scrap; a foul, blotted, interlined piece of writing. 4 also खरडें n A rude sketch; a rough draught; a foul copy; a waste-book; a day-book; a note-book. (Marathi) See: karuma sharpness of sword (Tamil)(DEDR 1265) karumā, 'blaksmith' (Tamil);karmāra 'blacksmith' (R̥gveda)

![]()

![]() Source: Dr. Berenice Bellina of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France, excavations conducted by the Thai Fine Arts at Phu Khao Thong in Thailand in 2007.

Source: Dr. Berenice Bellina of the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, France, excavations conducted by the Thai Fine Arts at Phu Khao Thong in Thailand in 2007.

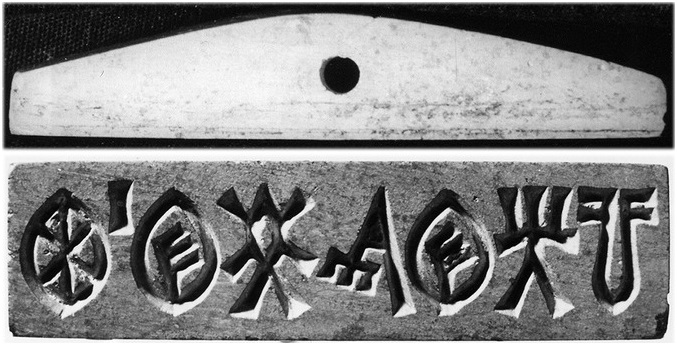

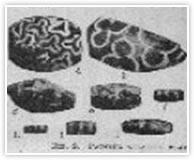

![]() The Phu Khao Thong potsherd inscription has hieroglyphs which read rebus: karaṇḍa'backbone' rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy' PLUS mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end. Thus the inscription reads: karaḍa mũhe 'hard metal alloy ingot'.

The Phu Khao Thong potsherd inscription has hieroglyphs which read rebus: karaṇḍa'backbone' rebus: karaḍa 'hard alloy' PLUS mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed like a four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end. Thus the inscription reads: karaḍa mũhe 'hard metal alloy ingot'.

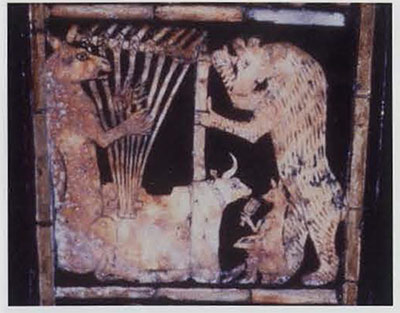

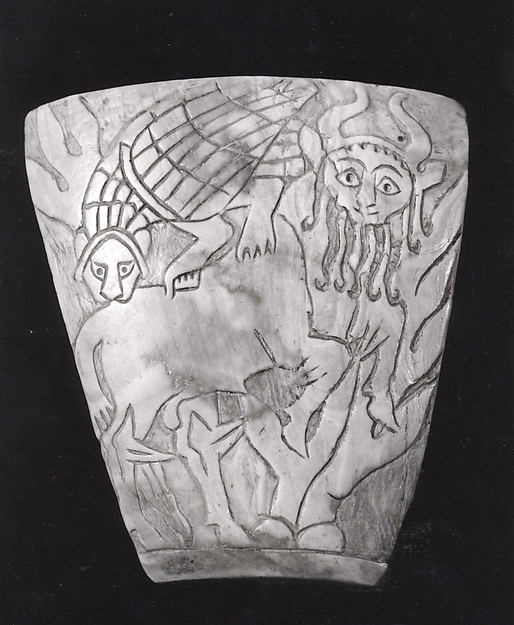

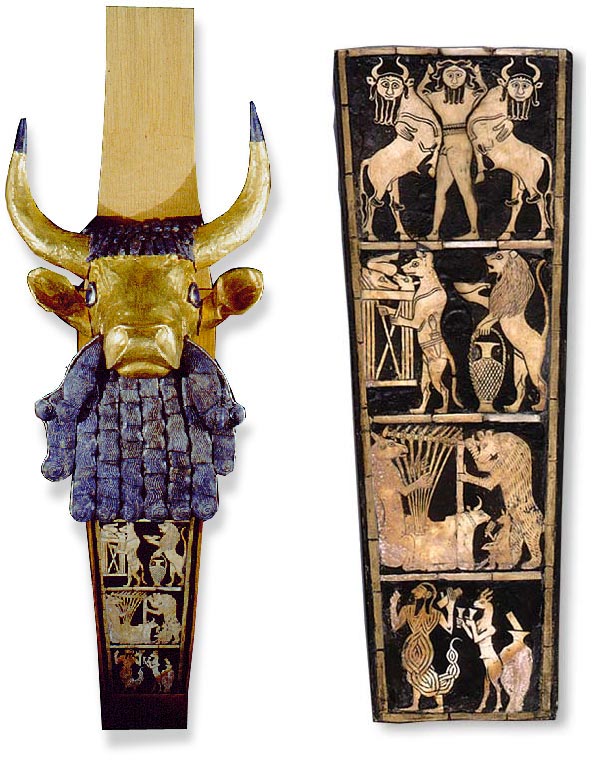

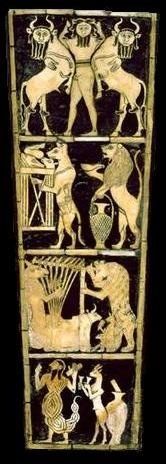

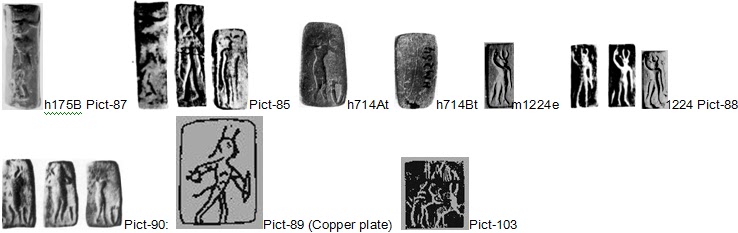

Onager shown on Standard of Ur (2600 BCE) is also shown on Indus Script inscriptions. An example is the seal from Mohenjo-daro (m290)(ca. 2500 BCE) which is a documentation of metalwork wealth by smelters' guild.![bull-head-lyre-panel]()

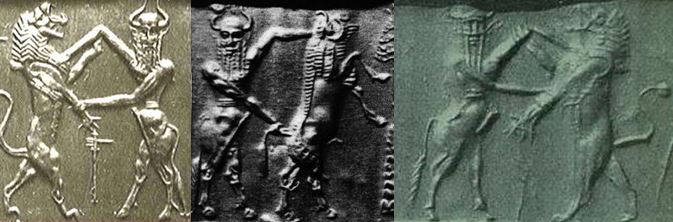

Thus, the symbolic ensemble is a documentation of metalwork in Indus Script Cipher.![Image result for mohenjodaro seal onager]() m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'ṭāṅka ʻleg, thighʼ (Oriya) rebus: ṭaṅka 'mint'

m290 Mohenjo-daro seal. Decipherment: kola 'tiger' Rebus; kolle 'blacksmith' kol 'working in iron' kole.l 'smithy, temple' kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS pattar 'trough' Rebus: pattar 'guild of goldsmiths'. panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace'ṭāṅka ʻleg, thighʼ (Oriya) rebus: ṭaṅka 'mint'

![]()

![]() baTa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'cast metal' Thus, cast metal furnace (Frequency of occurrence: 74)

baTa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'cast metal' Thus, cast metal furnace (Frequency of occurrence: 74)

![]()

![]() baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS kolmo 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy'. Thus smithy furnace (Frequency of occurrence: 111)

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS kolmo 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy'. Thus smithy furnace (Frequency of occurrence: 111)

![]()

![]() baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS gaNDa 'four' rebus: khaNDa 'implements'. Thus implements furnace (Frequency of occurrence: 50)

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS gaNDa 'four' rebus: khaNDa 'implements'. Thus implements furnace (Frequency of occurrence: 50)

![]()

![]() Stone seal. h179. National Museum, India. Carved seal. Scan 27418 Tongues of flame decorate the flaming pillar, further signified by two 'star' hieroglyphs on either side of the bottom of the flaming arch.

Stone seal. h179. National Museum, India. Carved seal. Scan 27418 Tongues of flame decorate the flaming pillar, further signified by two 'star' hieroglyphs on either side of the bottom of the flaming arch.

![]()

ü f. ʻ level surface by kitchen fireplace on which vessels are put when taken off fire ʼ; S. baṭhu m. ʻ large pot in which grain is parched, large cooking fire ʼ, baṭhī f. ʻ distilling furnace ʼ; L. bhaṭṭh m. ʻ grain -- parcher's oven ʼ, bhaṭṭhī f. ʻ kiln, distillery ʼ, awāṇ. bhaṭh; P. bhaṭṭhm., °ṭhī f. ʻ furnace ʼ, bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ; N. bhāṭi ʻ oven or vessel in which clothes are steamed for washing ʼ; A. bhaṭā ʻ brick -- or lime -- kiln ʼ; B. bhāṭi ʻ kiln ʼ; Or. bhāṭi ʻ brick -- kiln, distilling pot ʼ; Mth. bhaṭhī, bhaṭṭī ʻ brick -- kiln, furnace, still ʼ; Aw.lakh. bhāṭhā ʻ kiln ʼ; H. bhaṭṭhā m. ʻ kiln ʼ, bhaṭ f. ʻ kiln, oven, fireplace ʼ; M. bhaṭṭā m. ʻ pot of fire ʼ, bhaṭṭī f. ʻ forge ʼ. -- X bhástrā -- q.v.bhrāṣṭra -- ; *bhraṣṭrapūra -- , *bhraṣṭrāgāra -- .Addenda: bhráṣṭra -- : S.kcch. bhaṭṭhī keṇī ʻ distil (spirits) ʼ.*bhraṣṭrāgāra ʻ grain parching house ʼ. [bhráṣṭra -- , agāra -- ]P. bhaṭhiār, °ālā m. ʻ grainparcher's shop ʼ.(CDIAL 9656, 9658)![]()

![]()

![Image result for raised script metal bharatkalyan97]() Copper tablet (H2000-4498/9889-01) with raised script found in Trench 43 of Harappa. The raised script has apparently been achieved during casting in a mould. Over 8 such tablets have been found in Harappa from circular platforms (which are clearly meant for artisans working in metal smithy/forge work).

Copper tablet (H2000-4498/9889-01) with raised script found in Trench 43 of Harappa. The raised script has apparently been achieved during casting in a mould. Over 8 such tablets have been found in Harappa from circular platforms (which are clearly meant for artisans working in metal smithy/forge work).

![Circular, light grey steatite stamp-seal; hole pierced through back; Dilmun type; face shows engraved design of two men, each dressed in a long skirt, walking left and clutching a vase between them; left figure grasps a leaping gazelle or bull by the neck]()

-- pasār, pahārā, bazaar of Mohenjo-daro identified. Each circular artisan platform in Harappa is kole.l 'smithy, forge, temple'; Lajjā Gaurī (1st cent., Padri) signifies tāmarasa kóśa Indus Script hypertext, metalwork treasure

--Series of circular platforms in Harappa are a Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization bazaar, Lajjā Gaurī signifies Aditi, Devatā Ātmā (RV X.125), Indus Script hieroglyphs, metalworker's professional calling card

-- Archaeological evidence for the earliest bazaar of the world and veneration of Lajja Gaurī in Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization

-- Why does Lajjā Gaurī on a slate plaque found in Padri carry a lotus bud a a hieroglyph on her left hand?

-- Why is Lajjā Gaurī divinity shown as a headless woman, but with the lotus above the neck as a hieroglyph, vulva exposed?

-- Each of the circular workers' platforms may have held in the centre, a thã̄bh kole.l 'pillar temple' rebus signifier: tāmbā kole.l 'copper smithy.forge'.

-- Archaeological evidence for the earliest bazaar of the world is in a Meluhha word pahārāʻgoldsmith's workshopʼ, thanks to decipherment of Indus Script inscriptions on 1) Mohenjo-daro storage pot & 2) Susa pot with cargo received from Meluhha

-- Archaeological evidence of a Mohenjo-daro brick room with conical pits lined with wedge-shaped bricks

-- Mohenjo-daro brick room with conical pits is pasār, pahārā 'metals bazaar or market' of Sindhu-Sarasvati Civilization

-- Like copper anthropomorphs which are lapidary-smith-merchant professional calling cards, Lajjā Gaurī plaques are professional calling cards of metalworkers proclaiming their metallurgical competence related to working in gold and copper.

-- Evidence provided by Đinh Hồng Hải (2016) on the Lajjā Gaurī tradition of Cham people in Vietnam is appended (with a Google translation from his Vietnamese monograph)

This monograph provides Archaeological evidence for the earliest bazaar of the world in Mohenjo-daro; and explains why Lajjā Gaurī is venerated in Padri pahārā ʻgoldsmith's, coppersmith's workshop'. The name of the divinity is a signifier of the colour of copper/gold: गौर mf(/ई)n. (in comp. or ifc. g. कडारा*दि) white , yellowish , reddish , pale red RV. x , 100 , 2 TS. v &c (Monier-Williams) लाजाहोम lājāhōma m S A burnt-offering at weddings of लाजा or लाह्या to secure the bridegroom and bride from forsaking each other.(Marathi)

I submit that the Lajjā Gaurī plaque found in Padri is a professional calling card with a Meluhha message in Indus Script Cipher, of a metalsmith smelter because the orthography on the plaque signifies Indus Script hieroglyphs:

Lotus bud: tāmarasa kóśa 'lotus bud' rebus: तामरस कोश 'gold/copper treasure'.

कोश 'the vulva' rebus: कोश--वत् possessing treasures , rich , wealthy. Sun's rays: अंशुः read rebus ancu ‘iron’ (Tocharian);

अंशुः is a synonym of Soma. E.g., खर-अंशुः ‘sun’s rays’ rebus: khār ancu ‘blacksmith, iron’. On some Lajjā Gaurī sculptural representations (e.g. Amaravati sculptures), the head of the squatting divinity is replaced by a lotus flower. I submit that this is a semantic determinative of the rebus reading: tāmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tāmarasa 'gold, copper'. Lajjā Gaurī , the mother is Aditi, the ātmā devatā venerated in Devi Sūktam RV X.125. See:

A prayer to wealth givers, Rāṣṭrī Sūktamअहम् राष्ट्री संगमनी वसूनाम् I am the mover of nation's wealth: देवता आत्मा, ऋषिका वाक् आम्भृणी (RV 10.125) https://tinyurl.com/ybt5sas4

If the Padri find of Lajjā Gaurī plaque in Padri in a goldsmith's workshop signifies the artisanal professional calling card as a metalsmith smelter, it is likely that the circular workers' platforms found in a series along the Harappa Main Street also signified shops of guilds of metalsmiths and smelters. Each kole.l 'smithy/forge' is rebus: kole.l 'temple' (Kota language).

Why does Lajjā Gaurī hold a lotus bud on her hand on Padri slate plaque?

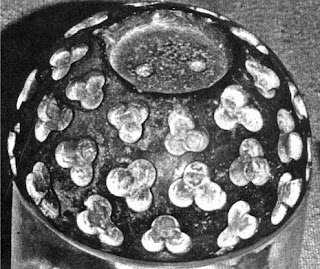

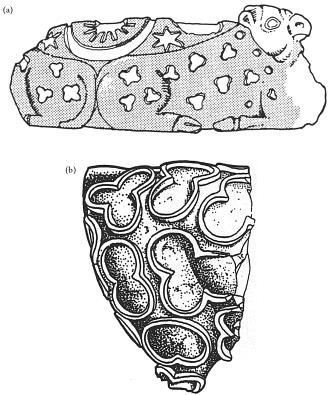

After Fig. 4. Squarish plaque of slate with a ‘Lajjā Gaurī’ engraved on it Shinde, Vasant, 1994, The earliest temple of Lajjā Gaurī? The recent evidence from Padri in Gujarat, in: East and West, Vol. 44, No. 2/4, December, 1994. The bottom portion of the plaque is signified by lotus petals with 'rays or sunbeams' to signify arka-amśu

अंशुः aṃśuḥ अंशुः [अंश्-मृग˚ कु.] 1 A ray, beam of light; चण्ड˚, घर्मं˚ hot-rayed the sun; सूर्यांशुभिर्भिन्नमिवारविन्दम् Ku.1.32; Iustre, brilliance चण्डांशुकिरणाभाश्च हाराः Rām.5.9.48; Śi.1.9. रत्न˚, नख˚ &c. -2 A point or end. -3 A small or minute particle. - 4 End of a thread. -5 A filament, especially of the Soma plant (Ved.) -6 Garment; decoration. -7 N. of a sage or of a prince. -8 Speed, velocity (वेग). -9 Fine thread -Comp. -उदकम् dew-water. -जालम् a collection of rays, a blaze or halo of light. -धरः -पतिः -भृत्-बाणः -भर्तृ-स्वामिन् the sun, (bearer or lord of rays). -पट्टम् a kind of silken cloth (अंशुना सूक्ष्मसूत्रेणयुक्तं पट्टम्); सश्रीफलैरंशुपट्टम् Y. 1.186; श्रीफलैरंशुपट्टानां Ms.5.12. -माला a garland of light, halo. -मालिन् m. [अंशवो मालेव, ततः अस्त्यर्थे इनि] 1 the sun (wreathed with, surrounded by, rays). -2 the number twelve. -हस्तः [अंशुः हस्त इव यस्य] the sun (who draws up water from the earth by means of his 1 hands in the form of rays). अंशुमत् aṃśumat अंशुमत् a. [अंशु-अस्त्यर्थे मतुप्] 1 Luminous, radiant; ज्योतिषां रविरंशुमान् Bg.1.21. -2 Pointed. -3 Fibrous, abounding in filaments (Ved.) -m.(˚मान्) 1 The sun; वालखिल्यैरिवांशुमान् R.15.1; अंशुमानिव तन्वभ्रपटलच्छन्नविग्रहः Ki.11.6; जलाधारेष्विवांशुमान् Y.3.144; rarely the moon also; ततः स मध्यंगतमंशुमन्तं Rām.5.5.1. -2 N. of the grandson of Sagara, son of Asamañjasa and father of Dilīpa. -3 N. of a mountain; ˚मत्फला N. of a plant, कदली Musa sapientum or Paradisiaca. -ती 1 N. of a plant सालपर्णी (Mar. डवला, सालवण) Desmodium Gangeticum. -2 N. of the river Yamunā. )(Apte)

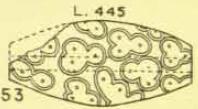

I submit that the lotus bud is a hieroglyph. It is tāmarasa कोश kóśa 'lotus bud'. This expression is read rebus: ताम--रस 'gold'; copper (cf. ताम्र) PLUS कोश kósa 'treasure'. Thus, the lotus bud on Lajjā Gaurī's hand signifies tāmarasa kóśa ताम--रस कोश 'gold/copper treasure'.

ताम--रस n. a day-lotus MBh. iii , 11580 Hariv. 5771 R. iii Ragh. (ifc. f(आ). , ix , 36) &c; Rebus: ताम--रस 'gold'; copper (cf. ताम्र); ताम्र mf(आ)n. ( √ तम् Un2. ) of a coppery red colour VS. xvi ( Naigh. iii , 7) MBh. &c (ताम्रा त्वच् , the 4th of the 7 membranes with which an embryo is covered Sus3r. iii , 4 , 2); mf(ई)n. made of copper R. iii , 21 , 17 Sus3r. Mn. vi , 53÷54 BhavP.; n. copper Kaus3. Mn. &c;n. a coppery receptacle MBh. ii , 61 , 29

Hieroglyph: कोश kósa 'bud, calix (esp. of the lotus)' Rebus: कोश kósa 'store-room; treasury, treasure; box, chest, sheath, case; abode; -griha, n. treasury; -gâta, n. treasure, wealth; -danda, m. du. treasury and army; -pîthin, a. draining or having drained any one's treasury; -petaka, m. n. casket; -rakshin, m. guardian of the treasury. (Arthur Anthony Macdonell, 1929, A Practical Sanskrit Dictionary, OUP, London)

Hieroglyph: कोश 'the vulva' (Monier-Williams) Rebus: (in वेदा*न्त phil.) a term for the three sheaths or succession of cases which make up the various frames of the body enveloping the soul (these are , 1. the आनन्द-मय क्° or " sheath of pleasure " , forming the कारण-शरीर or " causal frame " ; 2. the विज्ञान-मय or बुद्धि-म्° or मनो-म्° or प्रा*ण-म्° क्° , " the sheath of intellect or will or life " , forming the सूक्ष्म-शरीर or " subtile frame " ; 3. the अन्न-म्° क्° , " the sheath of nourishment " , forming the स्थूल-शरीर or " gross frame ") (वेदान्तसार) Hieroglyph: कोशी f. the beard of corn Rebus: f. an iron ploughshare(Monier-Williams) कोशा* धी* श ,

कोशा* धिपति m. a superintendent of the treasury , treasurer; Name of कुबेर; कोश--वत् possessing treasures , rich , wealthy MBh. Katha1s. lxi , 215 (Monier-Williams)

Hieroglyph: कोश 'the eye ball' (रामायण, iii , 79 , 28) Rebus: कोश an oath (

(राजतरंगिणी. v , 325; a cup used in the ratification of a treaty of peace (°शं- √पा , to drink from that cup)(राजतरंगिणी. vii , 8 ; 75 ; 460 and 493 ; viii , 283)

Hieroglyph: कोश f. " a bud " » अर्क- kósa; a bud , flower-cup , seed-vessel (cf. बीज-) (रामायण, रघुवंश,भागवत-पुराण, धूर्तसमागम); Rebus: कोश a cask , vessel for holding liquids , (metaphorically) cloud RV. AV. Sus3r.; a pail , bucket RV.; a drinking-vessel , cup; a box , cupboard , drawer , trunk RV. vi , 47 , 23 AV. xix , 72 , 1 S3Br.; a case , covering , cover AV. ChUp. Mun2d2Up. TUp. Pa1rGr2.BhP.;

store-room , store , provisions Mn. MBh. &c; a treasury , apartment where money or plate is kept , treasure , accumulated wealth (gold or silver , wrought or unwrought , as plate , jewellery , &c ) ib.; अर्क--कोशी f. a bud of the अर्क plant (शतपथ-ब्राह्मण, X) (Monier-Williams)

Griffith: RV VI.47.23 Ten horses and ten treasure chests-, ten garments as an added gift,These and ten lumps of gold have I received from Divodasas' hand.

Wilson: 6.047.23 I have received ten horses, ten purses, clothes, and ample food and ten lumps of gold from Divoda_sa.

कोशः, -शम् (षः, -षम्) [कुश् (ष्) आधारादौ घञ् कर्तरि अच् वा Tv.] 1 A vessel for holding liquids, a pail. -2 A bucket, cup. -3 A vessel in general. -4 A box, cupboard, drawer, trunk; Rv.6.47.23; स एष कोशो वसुधानस्तस्मिन्विश्वमिदं श्रितम् Ch. Up.3.15.1. -5 A sheath, scabbard; Ki.17.45. -6 A case, cover, covering. -7 A store, mass; ईश्वरः सर्वभूतानां धर्मकोशस्य गुप्तये Ms.1.99. -8 A store-room. -9 A treasury, an apartment where money is kept; Ms.8.419. -1 Treasure, money, wealth; निःशेषविश्राणितकोषजातम् R.5.1; (fig. also); कोशस्तपसः K.45; कोशपूर्वाः सर्वारम्भाः Kau. A.2.8. -11 Gold or silver wrought or unwrought. -12 A dictionary, lexicon, vocabulary. -13 A closed flower, bud; सुजातयोः पङ्कजकोशयोः श्रियम् R.3.8,13.29; इत्थं विचिन्तयति कोशगते द्विरेफे हा हन्त हन्त नलिनीं गज उज्जहार Subhāṣ. -14 The stone of a fruit. -15 A pod. -16 A nut-meg, nut-shell. -17 The cocoon of a silk-worm; निजलालासमायोगात्कोशं वा कोश- कारकः Y.3.147. -18 Vulva, the womb. -19 An egg. -2 A testicle or the scrotum. -21 The penis. -22 A ball, globe. -23(In Vedānta phil.) A term for the five (अन्न, प्राण, मनः, विज्ञान, आनन्द) vestures (sheaths or cases) which successively make the body, enshrining the soul. -24 (In law) A kind of ordeal; the defen- dant drinks thrice of the water after some idol has been washed in it; cf. Y.2.112. -25 A house. -26 A cloud. -27 The interior of a carriage. -28 A kind of bandage or ligature (in surgery). -29 An oath; कोशं चक्रतु- रन्योन्यं सखङ्गौ नृपडामरौ Rāj. T.2.326. -3 The pericarp of a lotus. -31 A piece of meat. -32 A cup used in the ratification of a treaty of peace; देवी कोशमपाययत् Rāj. T.7.8,75,459,492. -शी (-षी) 1 A bud. -2 A seed-vessel. -3 The beard of corn. -4 A shoe, sandal (पादुका). -Comp. -अधिपतिः, -अध्यक्षः a treasure, pay- master; (cf. the modern 'minister of finance'). -2 an epithet of Kubera. -अगारः, -रम् a treasurer, store-room. -कारः 1 one who makes scabbards. -2 a lexicographer. -3 the silk-worm while in the cocoon; भूमिं च कोशकाराणाम् Rām.4.4.23. -4 a chrysalis. -5 sugar-cane. -कारकः a silk-worm. Y.3.147. -कृत् m. a kind of sugar-cane. -गृहम् a treasury, store-room; R.5.29. -ग्रहणम् undergoing an ordeal. -चञ्चुः the (Indian) crane. -नायकः, -पालः 1 a treasurer. -2 An epithet of Kubera. -पेटकः, -कम् a chest in which treasure is kept, coffer. -फलम् 1 a kind of perfume. -2 a nut- meg. -वारि water used at an ordeal; Ks.119.35,42. -वासिन् m. an animal living in a shell, a chrysalis. -वृद्धिः f. 1 increase of treasure. -2enlargement of the scrotum. -वेश्मन् n. a treasury; भाण्डं च स्थापयामास तदीये कोषवेश्मनि Ks.24.133. -शायिका a clasped knife, knife lying in a sheath. -शुद्धिः f. purification by ordeal. -स्कृ m. a silk-worm; त्यजेत कोशस्कृदिवेहमानः Bhāg.7.6.13. -स्थ a. incased, sheathed. (-स्थः) an animal living in a shell (as a snail). -हीन a. deprived of riches, poor. (Apte)

Griffith: RV I.89.10 Aditi is the heaven, Aditi is midair-, Aditi is the Mother and the Sire and Son.

Aditi is all Gods, Aditi five classed- men, Aditi all that hath been born and shall be born.

Wilson: 1.089.10 Aditi is heaven; Aditi is the firmament; Aditi is mother, father and son; Aditi is all the gods; Aditi is the five classes of people; Aditi is generation and birth. [Aditi = lit. independent or indivisible, may signify the earth or the mother of the gods. Aditi is hymned as the same with the universe. aditer vibhutim a_cas.t.e, the hymn declares the might of Aditi (Nirukta 4,23); five classes of people: gandharvas (including apsara_sas, serpents), pitr.s (ancestors), gods, asuras and ra_ks.asas; janitvam = faculty of being born, hence, generation].

![]()

![]()

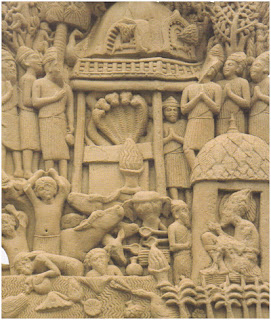

After Fig.1,Fig.2,Fig.3, Fig.4 in: Baba Mishra, Pradeep Mohanty, and PK Mohanty, 2003, Headless contour in the art tradition of Orissa, in: Bulletin of the Deccan College Post-Graduate and Research InstituteVol. 62/63, PROFESSOR ASHOK R. KELKAR FELICITATION VOLUME (2002-2003), pp. 311-321

https://www.jstor.org/stable/42930626 (Copy embedded, annexed in 11 pages)![]() Shiva and Shakti in the half-male, half-female form of Ardhanari. (Elephanta caves, Mumbai, India.)

Shiva and Shakti in the half-male, half-female form of Ardhanari. (Elephanta caves, Mumbai, India.)

Feminine as the supreme divine

"...the Great Goddess of the Indus Valley and Dravidian religions still loomed large in the Vedas, taking most notably the mysterious form of Aditi, the "Vedic Mother of the Gods." Aditi is mentioned about 80 times in the Rigveda, and her appellation (meaning "without limits" in Sanskrit) marks what is perhaps the earliest name used to personify the infinite.[4] Vedic descriptions of Aditi are vividly reflected in the countless Lajjā Gaurī idols – depicting a faceless, lotus-headed goddess in birthing posture – that have been worshiped throughout India for millennia...Other goddess forms appearing prominently in the Vedic period include the Usas, the daughters of the sun-god Surya who govern the dawn and are mentioned more than 300 times in no less than 20 hymns. Prithvi,a variation of the archetypal Indo-European Earth Mother form, is also referenced. More significant is the appearance of two of Hinduism's most widely known and beloved goddesses: Vāc, today better known as Sarasvati; and Srī, now better known as Lakshmi in the famous Rigvedic hymn entitled Devi Sukta. Here these goddesses unambiguously declare their divine supremacy, in words still recited by many Hindus each day:"I am the Sovereign Queen; the treasury of all treasures; the chief of all objects of worship; whose all-pervading Self manifests all gods and goddesses; whose birthplace is in the midst of the causal waters; who in breathing forth gives birth to all created worlds, and yet extends beyond them, so vast am I in greatness." This suggests that the feminine was indeed venerated as the supreme divine in the Vedic age, even in spite of the generally patriarchal nature of the texts.(N.N. Bhattacharyya. History of the Sakta Religion. (New Delhi: Munshiram Manoharlal Publishers Pvt. Ltd., 1974), 42; Carol Radcliffe Bolon. Forms of the Goddess Lajja Gauri in Indian Art. (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 1992).http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Shaktism#cite_note-5"![Image result for harappa circular workers' platforms]() Harappa. Circular Workers' Platforms. Each platform signifies thã̄bh kole.l 'pillar temple' rebus signifier: tāmbā kole.l 'copper smithy.forge'.

Harappa. Circular Workers' Platforms. Each platform signifies thã̄bh kole.l 'pillar temple' rebus signifier: tāmbā kole.l 'copper smithy.forge'.

The word for this assemblage of smithy/forge workplaces is फड, phaḍa 'metalwork artisan guild', 'Bhāratīya arsenal of metal workers guild'. A cognate word is: paṭṭaḍe 'anvil,metals workshop'.

పట్టడ paṭṭaḍu. [Tel.] n. A smithy, a shop. కుమ్మరి వడ్లంగి మొదలగువారు పనిచేయు చోటు.

Ta. paṭṭaṭai, paṭṭaṟai anvil, smithy, forge. Ka. paṭṭaḍe, paṭṭaḍi anvil, workshop. Te. paṭṭika, paṭṭeḍa anvil; paṭṭaḍaworkshop. Cf. 86 Ta. aṭai. (DEDR 3865)Ta. aṭai prop. slight support; aṭai-kal anvil. Ma. aṭa-kkallu anvil of goldsmiths. Ko. aṛ gal small anvil. Ka. aḍe, aḍa, aḍi the piece of wood on which the five artisans put the article which they happen to operate upon, a support; aḍegal, aḍagallu, aḍigallu anvil. Tu. aṭṭè a support, stand. Te. ḍā-kali, ḍā-kallu, dākali, dā-gali, dāyi anvil. (DEDR 86)

கொல்லன்பட்டடை kollaṉ-paṭṭaṭai , n. < கொல்லன் +. Anvil; அடைகல் . (C. G .)

கொல்லன்பட்டரை kollaṉ-paṭṭarai , n. < id. +. Blacksmith's workshop, smithy; கொல்லன் உலைக்கூடம் .பட்டடை1 paṭṭaṭai , n. prob. படு1- + அடை1- . 1. [T. paṭṭika, K. paṭṭaḍe.] Anvil; அடைகல். (பிங்.) சீரிடங்காணி னெறிதற்குப் பட்ட டை (குறள் , 821). 2. [K. paṭṭaḍi.] Smithy, forge; கொல்லன் களரி . 3. Stock, heap, pile, as of straw, firewood or timber; குவியல் . (W .) பட்டடையார் paṭṭaṭaiyār , n. < id. (W. G .) 1. Master of a shop; கடையின் எசமானர் . 2. Overseer; மேற்பார்ப்போர் .

Hieroglyph: फडा (p. 313) phaḍā f (फटा S) The hood of Coluber Nága &c. Ta. patam cobra's hood. Ma. paṭam id. Ka. peḍe id. Te. paḍaga id. Go. (S.) paṛge, (Mu.) baṛak, (Ma.) baṛki, (F-H.) biṛki hood of serpent (Voc. 2154). / Turner, CDIAL, no. 9040, Skt. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā- id. For IE etymology, see Burrow, The Problem of Shwa in Sanskrit, p. 45.(DEDR 47) Rebus: phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office’, keeper of all accounts, registers.फडपूस (p. 313) phaḍapūsa f (फड & पुसणें) Public or open inquiry. फडफरमाश or स (p. 313) phaḍapharamāśa or sa f ( H & P) Fruit, vegetables &c. furnished on occasions to Rajas and public officers, on the authority of their order upon the villages; any petty article or trifling work exacted from the Ryots by Government or a public officer.

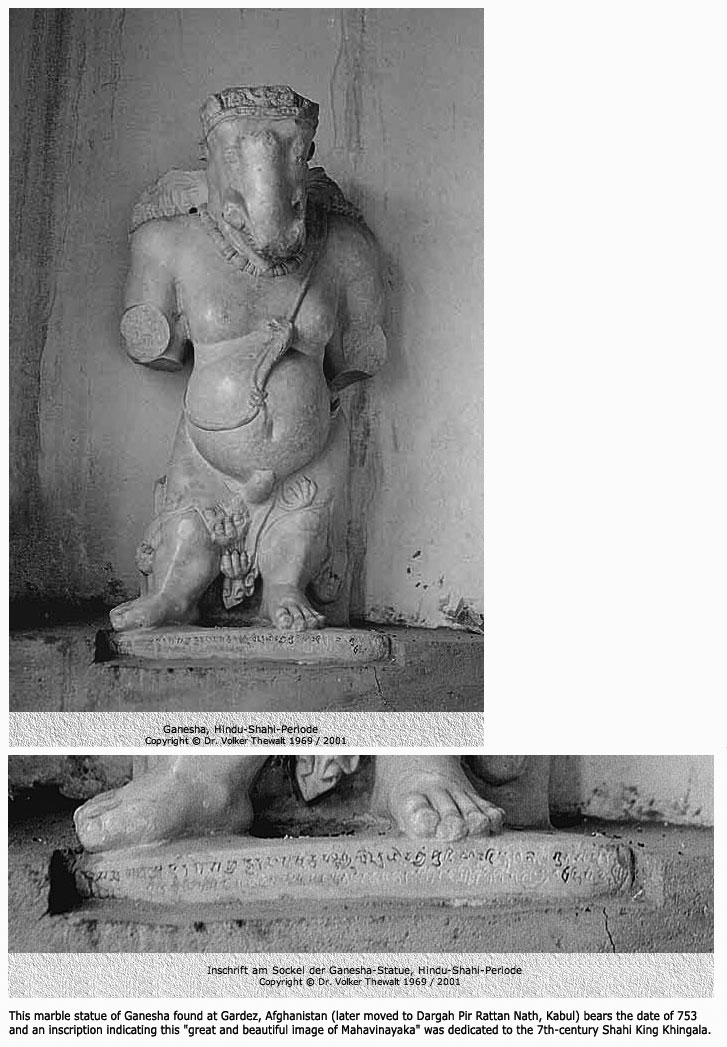

![Image result for gardez ganesha]() Cloth worn on Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan. Hieroglyph: படம்¹ paṭam , n. < paṭa. 1. Cloth for wear; சீலை. (பிங்.) மாப்பட நூலின் றொகுதிக் காண் டலின் (ஞானா. 14, 21). 2. Painted or printed cloth; சித்திரச்சீலை. (பிங்.) இப்படத்தெழுது ஞான வாவி (காசிக. கலாவ. 2). 3. Coat, jacket; சட்டை. படம்புக்கு (பெரும்பாண். 69). 4. Upper garment, cloak; போர்வை. வனப்பகட்டைப் பட மாக வுரித்தாய் (தேவா. 32, 7). 5. Body; உடல். படங்கொடு நின்றவிப் பல்லுயிர் (திருமந். 2768). The cobra shown on the pratimā signifies फड phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; semantic determinatives are: panja 'feline paw' rrebus: panja 'kiln, furnace' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'. He is Mahā Vināyaka, the leader of Gaṇa 'guilds' of kharva 'dwarfs' rebus: karba 'iron'.Kharva is one of nine treasures, Kubera's navanidhi. These imageries are celebrated on Bhutesvar sculptural friezes.

Cloth worn on Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan. Hieroglyph: படம்¹ paṭam , n. < paṭa. 1. Cloth for wear; சீலை. (பிங்.) மாப்பட நூலின் றொகுதிக் காண் டலின் (ஞானா. 14, 21). 2. Painted or printed cloth; சித்திரச்சீலை. (பிங்.) இப்படத்தெழுது ஞான வாவி (காசிக. கலாவ. 2). 3. Coat, jacket; சட்டை. படம்புக்கு (பெரும்பாண். 69). 4. Upper garment, cloak; போர்வை. வனப்பகட்டைப் பட மாக வுரித்தாய் (தேவா. 32, 7). 5. Body; உடல். படங்கொடு நின்றவிப் பல்லுயிர் (திருமந். 2768). The cobra shown on the pratimā signifies फड phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; semantic determinatives are: panja 'feline paw' rrebus: panja 'kiln, furnace' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'. He is Mahā Vināyaka, the leader of Gaṇa 'guilds' of kharva 'dwarfs' rebus: karba 'iron'.Kharva is one of nine treasures, Kubera's navanidhi. These imageries are celebrated on Bhutesvar sculptural friezes.

![]() Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE.Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228). http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/smithy-is-temple-of-bronze-age-stambha_14.html H. dām m.f. ʻ rope, string, fetter ʼ, dāmā m. ʻ id., garland ʼ(CDIA Si. dama ʻ chain, rope ʼ, (SigGr) dam ʻ garland ʼ.L 6283) rebus: dhAu 'metal; (Prakrtam) dhAI 'wisp of fibres' (S.) dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√

Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE.Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228). http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/smithy-is-temple-of-bronze-age-stambha_14.html H. dām m.f. ʻ rope, string, fetter ʼ, dāmā m. ʻ id., garland ʼ(CDIA Si. dama ʻ chain, rope ʼ, (SigGr) dam ʻ garland ʼ.L 6283) rebus: dhAu 'metal; (Prakrtam) dhAI 'wisp of fibres' (S.) dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ]Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whenceḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)![File:Worship of Shiva Linga by Gandharvas - Shunga Period - Bhuteshwar - ACCN 3625 - Government Museum - Mathura 2013-02-24 6098.JPG]() Worship of Shiva Linga by Gandharvas - Shunga Period - Bhuteshwar - ACCN 3625 - Government Museum - Mathura

Worship of Shiva Linga by Gandharvas - Shunga Period - Bhuteshwar - ACCN 3625 - Government Museum - Mathura

kuThi 'smelter' lokhaNDa 'metal implements' (lo 'penis' -- Munda)![]() Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2). This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2). This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually मेढ q. v.) मेडका m A stake, esp. as bifurcated. मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] f A forked stake. Used as a post. Hence a short post generally whether forked or not. मेढा (p. 665) [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. 2 A dense arrangement of stakes, a palisade, a paling. मेढी (p. 665) [ mēḍhī ] f (Dim. of मेढ ) A small bifurcated stake: also a small stake, with or without furcation, used as a post to support a cross piece. मेढ्या (p. 665) [ mēḍhyā ] a (मेढ Stake or post.) A term for a person considered as the pillar, prop, or support (of a household, army, or other body), the staff or stay. मेढेजोशी (p. 665) [ mēḍhējōśī ] m A stake-जोशी ; a जोशी who keeps account of the तिथि &c., by driving stakes into the ground: also a class, or an individual of it, of fortune-tellers, diviners, presagers, seasonannouncers, almanack-makers &c. They are Shúdras and followers of the मेढेमत q. v. 2 Jocosely. The hereditary or settled (quasi fixed as a stake) जोशी of a village.मेंधला (p. 665) [ mēndhalā ] m In architecture. A common term for the two upper arms of a double चौकठ (door-frame) connecting the two. Called also मेंढरी & घोडा . It answers to छिली the name of the two lower arms or connections. (Marathi)

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda)

Since Sivalinga as aniconic forms are also signified by चतुर्श्रि, अष्टाश्रि quadrangular, octagonal components and as iconic connotations appear with ekamukha linga (linga with one face ligatured), it is surmised that Sivalinga are Yupa skambha, as a multi-layered, metallurgical metaphor. One layer relates to the rebus reading of the ekamukha. The surmise of Sivalinga as Yupa Skambha is framed on the extraordinary metaphors of the philosophical tractus in Atharva veda called Skambha Sukta (AV X.7). ![]()

The ekamukha linga signified on such pillars atop a kiln or smelter on Bhuteswar sculptural friezes refer to mũh 'face' rebus: mũhe 'ingot', mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes, 'smelters'. (Santali) A garland is arried by a dwarf, to signify dāmā m. ʻ id., garland ʼ rebus: Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (Red ochre is Fe2O3, takes its reddish color from the mineral hematite, which is an anhydrous iron oxide.)

kharva, 'dwarfs' are associated with ekamukha śivalinga (Rudra) atop a smelter on Bhutesvar sculptural friezes, to signify wealth-producing smelted products. mũh 'a face' in Indus Script Cipher signifies mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' kharva 'dwarf' rebus: kharva 'nidhi of Kubera' karba 'iron'.

Association of Gaṇeśa with metalwork is vividly demonstrated on Candi-Sukuh sculptural frieze which shows Bhima as blacksmith, Arjuna as bellows blower and Gaṇeśa on a dance step karaṇa rebus:karana 'scribe'. karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' mẽḍha 'ram' meḍho 'helper of merchant

Thus, the spectacular series of circular workers' platforms evidenced in Harappa may be a series of tāmbā kole.l 'smithy, forge' structures working on copper metal.

This monographs demonstrates, based on decipherment of over 8000 inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora that the Mohenjo-daro brick room signifies a metalware shop. The underlying Meluhha dialect expression is: pajhar 'smelter, smithy', rebus: పసారము pasāramu or పసారు pasāramu. [Tel.] n. A shop. The Bengali cognate is: pasār ʻextent of practice in business, popularityʼ (or, market). That the business is related to metalwork is signified by Punjabi cognate: pahārā m. ʻgoldsmith's workshop'. I submit that the semantics of this Punjabi word extended to the shop vending metalware.

Cheh Tuti Chowk or Six Tuti Chowk, Main Bazaar, is in an area called Paharganj in Old Delhi. Note the expression: Paharganj; the word pahar is likely to be the old Meluhha word to signify a metalware shop, since a cognate word pajhar signifies a smithy in Santali.

بازار bāzār, s.m. (2nd) A market. Pl. بازارونه bāzārūnah. P بازارګيَ bāzārgaey, s.m. (1st) A small market. Pl. يِ ī. P بازاري bāzār-ī, adj. Belonging to the market, a market person. (Pashto) bāzar बाज़र् (=। विपणिः m. a street with shops in it, a market, market-place, bazaar, mart (YZ. 40, 253, where the word is spelt bāzār, in imitation of Persian; K.Pr. 78, 103, Śiv. 1211, 1808). In Śiv. 1566 bāzār also occurs m.c. in the sense of market, i.e. traffic of the market. --aʦun --अच़ुन् । व्यसनवृत्तिः m.inf. to enter the bazaar; esp. to waste one's money in bazaar enjoyments, to lead a dissolute life. -banga -बंग । अन्नफलविशेषः f. a certain food grain, a kind of millet, akin to bājrā (Panicum spicatum or P. italicum). --ʦānun --च़ानुन् । व्यसनासञ्जनम् m.inf. to cause to enter the bazaar; to induce (a respectable youth) to lead a profligate life; to seduce to dissoluteness. --wuchun --वुछुन् । मूल्यपरीक्षणम् m.inf. to look at the bazaar; to ascertain the market rate of anything, to test the value of anything by comparison with the market price.(Kashmiri)Shop, smithy, forge: pasôru पसोरु॒ m. a mean petty shopkeeper, a druggist, a grocer (cf. Hindī pansārī), in the following:--pasöri-bāy पसा॑रि॒-बाय् । पामरवणिक्स्त्री f. the wife of such a petty shopkeeper. -küṭü -क॑टू॒ । पामरकन्या f. the daughter of such a petty shopkeeper; (as an abusive term) an ill-conducted woman. -kaṭh -कठ् । पामरपुत्रः m. (sg. dat. -kaṭas -कटस् ), the son of such a petty shopkeeper; (as an abusive term) a mean, ill-conducted man. -pöthar -पा॑थ्र् । पामरवणिग्व्यापारः m. the occupation of a mean petty shopkeeper; occupation (of some one else) similar to such. -wān -वान् । पामरवणिगापणः m. the shop of such a mean shopkeeper. pạsürü प॑स॒॑रू॒। प्रान्तखण्डसमूहः f. a chip, filing or the like (such as cutting from the edge of a metal plate in making a vessel). Cf. pạsarun. pạsaran प॑स्रन् । प्रान्ततक्षणेन समीकरणम्, कुट्टनेन विस्तारणम् f. (sg. dat. pạsarüña प॑स्र॑ञू॒ ), paring off the edges of a metal plate (for manufacture); beating out a metal plate to flatten it or beat it thin. pạsarun प॑स्रुन् । प्रान्ततक्षणम्, कुट्टनेन विस्तारणम् conj. 1 (1 p.p. pạsoro प॑स॒॑रु॒ ), to pare off the edges of a metal plate (in manufacture); to beat out a metal plate to flatten it or beat it thin. pạsoro-moto प॑स॒॑रु॒-म॑तु॒ । प्रान्तेषु तष्टः, कुट्टनेन विस्तारितः perf. part. (f. pạsürü-müʦü प॑स॒॑रू॒-म॑च़ू॒ ), having the edges pared off; beaten out flat. pasārun पसारुन् । पात्रतक्षणम् conj. 1 (1 p.p. pasôru पसोरु॒ ), i.q. pạsarun, q.v. pasôru-motu पसोरु॒-म॑तु॒ । कुट्टनेन विस्तारितः, कर्तनेन समीकृतः perf. part. (f. pasörü-müʦü पसा॑रू॒-म॑च़ू॒ ), i.q. pạsoro-moto, s.v. pạsarun, q.v. pasöril पसा॑रिल् । पामरवणिग्वृत्तिः f. the business of a petty shopkeeper, of a druggist, of a grocer.

Santali. पाजिकः A falcon (Skt.) rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’.

"A bazaar is a permanently enclosed marketplace or street where goods and services are exchanged or sold. The term originates from the Persian word bāzār." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bazaar I submit that the root of the Persian word is traceable to many forms of pasar 'shop, spreading out' in Meluhha (mleccha) spoken form dialects of Indian sprachbund, 'speech union'. The Prakrit word is pasara ʻextensionʼ. The word seems to have originated in the Punjabi word, pahārā which signifies a goldsmith's workshop.'

Evidence for such a shop is seen in a Mohenjo-daro brick room described by John Marshall. With the evidence of a seal impression on a storage jar in Indus Script which has been deciphered in this monograph, it can be established that the shop of Mohenjo-daro is datable to ca. 3300 BCE since the first evidence of writing is also dated to ca. 3300 BCE from a potsherd of Harappa with Indus Script inscription. (cf. HARP reports).

![]()

![Image may contain: outdoor]()

1. VS. Area, Section A, Block I, House II: Floor in shop made of cut and rubbed brick on edge. (Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, III, pl. LIV, a) and above, Same floor as shown below about 45 years later. https://www.harappa.com/blog/mohenjo-daro-cause-common-concern

Vol. 62/63, PROFESSOR ASHOK R. KELKAR FELICITATION VOLUME (2002-2003), pp. 311-321

Harappa. Circular Workers' Platforms. Each platform signifies thã̄bh kole.l 'pillar temple' rebus signifier: tāmbā kole.l 'copper smithy.forge'.

Harappa. Circular Workers' Platforms. Each platform signifies thã̄bh kole.l 'pillar temple' rebus signifier: tāmbā kole.l 'copper smithy.forge'.The word for this assemblage of smithy/forge workplaces is फड, phaḍa 'metalwork artisan guild', 'Bhāratīya arsenal of metal workers guild'. A cognate word is: paṭṭaḍe 'anvil,metals workshop'.

పట్టడ paṭṭaḍu. [Tel.] n. A smithy, a shop. కుమ్మరి వడ్లంగి మొదలగువారు పనిచేయు చోటు.

Ta. paṭṭaṭai, paṭṭaṟai anvil, smithy, forge. Ka. paṭṭaḍe, paṭṭaḍi anvil, workshop. Te. paṭṭika, paṭṭeḍa anvil; paṭṭaḍaworkshop. Cf. 86 Ta. aṭai. (DEDR 3865)Ta. aṭai prop. slight support; aṭai-kal anvil. Ma. aṭa-kkallu anvil of goldsmiths. Ko. aṛ gal small anvil. Ka. aḍe, aḍa, aḍi the piece of wood on which the five artisans put the article which they happen to operate upon, a support; aḍegal, aḍagallu, aḍigallu anvil. Tu. aṭṭè a support, stand. Te. ḍā-kali, ḍā-kallu, dākali, dā-gali, dāyi anvil. (DEDR 86)

Hieroglyph: फडा (p. 313) phaḍā f (फटा S) The hood of Coluber Nága &c. Ta. patam cobra's hood. Ma. paṭam id. Ka. peḍe id. Te. paḍaga id. Go. (S.) paṛge, (Mu.) baṛak, (Ma.) baṛki, (F-H.) biṛki hood of serpent (Voc. 2154). / Turner, CDIAL, no. 9040, Skt. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā- id. For IE etymology, see Burrow, The Problem of Shwa in Sanskrit, p. 45.(DEDR 47) Rebus: phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office’, keeper of all accounts, registers.

![Image result for gardez ganesha]() Cloth worn on Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan. Hieroglyph: படம்¹ paṭam , n. < paṭa. 1. Cloth for wear; சீலை. (பிங்.) மாப்பட நூலின் றொகுதிக் காண் டலின் (ஞானா. 14, 21). 2. Painted or printed cloth; சித்திரச்சீலை. (பிங்.) இப்படத்தெழுது ஞான வாவி (காசிக. கலாவ. 2). 3. Coat, jacket; சட்டை. படம்புக்கு (பெரும்பாண். 69). 4. Upper garment, cloak; போர்வை. வனப்பகட்டைப் பட மாக வுரித்தாய் (தேவா. 32, 7). 5. Body; உடல். படங்கொடு நின்றவிப் பல்லுயிர் (திருமந். 2768). The cobra shown on the pratimā signifies फड phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; semantic determinatives are: panja 'feline paw' rrebus: panja 'kiln, furnace' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'. He is Mahā Vināyaka, the leader of Gaṇa 'guilds' of kharva 'dwarfs' rebus: karba 'iron'.Kharva is one of nine treasures, Kubera's navanidhi. These imageries are celebrated on Bhutesvar sculptural friezes.

Cloth worn on Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan. Hieroglyph: படம்¹ paṭam , n. < paṭa. 1. Cloth for wear; சீலை. (பிங்.) மாப்பட நூலின் றொகுதிக் காண் டலின் (ஞானா. 14, 21). 2. Painted or printed cloth; சித்திரச்சீலை. (பிங்.) இப்படத்தெழுது ஞான வாவி (காசிக. கலாவ. 2). 3. Coat, jacket; சட்டை. படம்புக்கு (பெரும்பாண். 69). 4. Upper garment, cloak; போர்வை. வனப்பகட்டைப் பட மாக வுரித்தாய் (தேவா. 32, 7). 5. Body; உடல். படங்கொடு நின்றவிப் பல்லுயிர் (திருமந். 2768). The cobra shown on the pratimā signifies फड phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; semantic determinatives are: panja 'feline paw' rrebus: panja 'kiln, furnace' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'. He is Mahā Vināyaka, the leader of Gaṇa 'guilds' of kharva 'dwarfs' rebus: karba 'iron'.Kharva is one of nine treasures, Kubera's navanidhi. These imageries are celebrated on Bhutesvar sculptural friezes.

फडपूस (p. 313) phaḍapūsa f (फड & पुसणें) Public or open inquiry. फडफरमाश or स (p. 313) phaḍapharamāśa or sa f ( H & P) Fruit, vegetables &c. furnished on occasions to Rajas and public officers, on the authority of their order upon the villages; any petty article or trifling work exacted from the Ryots by Government or a public officer.

फडनिविशी or सी (p. 313) phaḍaniviśī or sī & फडनिवीस Commonly फड- निशी & फडनीस. फडनीस (p. 313) phaḍanīsa m ( H) A public officer,--the keeper of the registers &c. By him were issued all grants, commissions, and orders; and to him were rendered all accounts from the other departments. He answers to Deputy auditor and accountant. Formerly the head Kárkún of a district-cutcherry who had charge of the accounts &c. was called फडनीस.

फडकरी (p. 313) phaḍakarī m A man belonging to a company or band (of players, showmen &c.) 2 A superintendent or master of a फड or public place. See under फड. 3 A retail-dealer (esp. in grain).

फडझडती (p. 313) phaḍajhaḍatī f sometimes फडझाडणी f A clearing off of public business (of any business comprehended under the word फड q. v.): also clearing examination of any फड or place of public business.

फड (p. 313) phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; as a court of justice, an exchange, a mart, a counting-house, a custom-house, an auction-room: also, in an ill-sense, as खेळण्या- चा फड A gambling-house, नाचण्याचा फड A nach house, गाण्याचा or ख्यालीखुशालीचा फड A singing shop or merriment shop. The word expresses freely Gymnasium or arena, circus, club-room, debating-room, house or room or stand for idlers, newsmongers, gossips, scamps &c. 2 The spot to which field-produce is brought, that the crop may be ascertained and the tax fixed; the depot at which the Government-revenue in kind is delivered; a place in general where goods in quantity are exposed for inspection or sale. 3 Any office or place of extensive business or work, as a factory, manufactory, arsenal, dock-yard, printing-office &c. 4 A plantation or field (as of ऊस, वांग्या, मिरच्या, खरबुजे &c.): also a standing crop of such produce. 5 fig. Full and vigorous operation or proceeding, the going on with high animation and bustle (of business in general). v चाल, पड, घाल, मांड. 6 A company, a troop, a band or set (as of actors, showmen, dancers &c.) 7 The stand of a great gun. फड पडणें g. of s. To be in full and active operation. 2 To come under brisk discussion. फड मारणें- राखणें-संभाळणें To save appearances, फड मारणें or संपादणें To cut a dash; to make a display (upon an occasion). फडाच्या मापानें With full tale; in flowing measure. फडास येणें To come before the public; to come under general discussion.

Cloth worn on Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan. Hieroglyph: படம்¹ paṭam , n. < paṭa. 1. Cloth for wear; சீலை. (பிங்.) மாப்பட நூலின் றொகுதிக் காண் டலின் (ஞானா. 14, 21). 2. Painted or printed cloth; சித்திரச்சீலை. (பிங்.) இப்படத்தெழுது ஞான வாவி (காசிக. கலாவ. 2). 3. Coat, jacket; சட்டை. படம்புக்கு (பெரும்பாண். 69). 4. Upper garment, cloak; போர்வை. வனப்பகட்டைப் பட மாக வுரித்தாய் (தேவா. 32, 7). 5. Body; உடல். படங்கொடு நின்றவிப் பல்லுயிர் (திருமந். 2768). The cobra shown on the pratimā signifies फड phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; semantic determinatives are: panja 'feline paw' rrebus: panja 'kiln, furnace' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'. He is Mahā Vināyaka, the leader of Gaṇa 'guilds' of kharva 'dwarfs' rebus: karba 'iron'.Kharva is one of nine treasures, Kubera's navanidhi. These imageries are celebrated on Bhutesvar sculptural friezes.

Cloth worn on Gaṇeśa pratimā, Gardez, Afghanistan. Hieroglyph: படம்¹ paṭam , n. < paṭa. 1. Cloth for wear; சீலை. (பிங்.) மாப்பட நூலின் றொகுதிக் காண் டலின் (ஞானா. 14, 21). 2. Painted or printed cloth; சித்திரச்சீலை. (பிங்.) இப்படத்தெழுது ஞான வாவி (காசிக. கலாவ. 2). 3. Coat, jacket; சட்டை. படம்புக்கு (பெரும்பாண். 69). 4. Upper garment, cloak; போர்வை. வனப்பகட்டைப் பட மாக வுரித்தாய் (தேவா. 32, 7). 5. Body; உடல். படங்கொடு நின்றவிப் பல்லுயிர் (திருமந். 2768). The cobra shown on the pratimā signifies फड phaḍa m ( H) A place of public business or public resort; semantic determinatives are: panja 'feline paw' rrebus: panja 'kiln, furnace' kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'. He is Mahā Vināyaka, the leader of Gaṇa 'guilds' of kharva 'dwarfs' rebus: karba 'iron'.Kharva is one of nine treasures, Kubera's navanidhi. These imageries are celebrated on Bhutesvar sculptural friezes.

Architectural fragment with relief showing winged dwarfs (or gaNa) worshipping with flower garlands, Siva Linga. Bhuteshwar, ca. 2nd cent BCE.Lingam is on a platform with wall under a pipal tree encircled by railing. (Srivastava, AK, 1999, Catalogue of Saiva sculptures in Government Museum, Mathura: 47, GMM 52.3625) The tree is a phonetic determinant of the smelter indicated by the railing around the linga: kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ Rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'. kuṭa, °ṭi -- , °ṭha -- 3, °ṭhi -- m. ʻ tree ʼ lex., °ṭaka -- m. ʻ a kind of tree ʼ Kauś.Pk. kuḍa -- m. ʻ tree ʼ; Paš. lauṛ. kuṛāˊ ʻ tree ʼ, dar. kaṛék ʻ tree, oak ʼ ~ Par. kōṛ ʻ stick ʼ IIFL iii 3, 98. (CDIAL 3228). http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2015/05/smithy-is-temple-of-bronze-age-stambha_14.html H. dām m.f. ʻ rope, string, fetter ʼ, dāmā m. ʻ id., garland ʼ(CDIA Si. dama ʻ chain, rope ʼ, (SigGr) dam ʻ garland ʼ.L 6283) rebus: dhAu 'metal; (Prakrtam) dhAI 'wisp of fibres' (S.) dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ]

Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whenceḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773)

Worship of Shiva Linga by Gandharvas - Shunga Period - Bhuteshwar - ACCN 3625 - Government Museum - Mathura

kuThi 'smelter' lokhaNDa 'metal implements' (lo 'penis' -- Munda)

Relief with Ekamukha linga. Mathura. 1st cent. CE (Fig. 6.2). This is the most emphatic representation of linga as a pillar of fire. The pillar is embedded within a brick-kiln with an angular roof and is ligatured to a tree. Hieroglyph: kuTi 'tree' rebus: kuThi 'smelter'. In this composition, the artists is depicting the smelter used for smelting to create mũh 'face' (Hindi) rebus: mũhe 'ingot' (Santali) of mēḍha 'stake' rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda). मेड (p. 662) [ mēḍa ] f (Usually मेढ q. v.) मेडका m A stake, esp. as bifurcated. मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] f A forked stake. Used as a post. Hence a short post generally whether forked or not. मेढा (p. 665) [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. 2 A dense arrangement of stakes, a palisade, a paling. मेढी (p. 665) [ mēḍhī ] f (Dim. of मेढ ) A small bifurcated stake: also a small stake, with or without furcation, used as a post to support a cross piece. मेढ्या (p. 665) [ mēḍhyā ] a (मेढ Stake or post.) A term for a person considered as the pillar, prop, or support (of a household, army, or other body), the staff or stay. मेढेजोशी (p. 665) [ mēḍhējōśī ] m A stake-जोशी ; a जोशी who keeps account of the तिथि &c., by driving stakes into the ground: also a class, or an individual of it, of fortune-tellers, diviners, presagers, seasonannouncers, almanack-makers &c. They are Shúdras and followers of the मेढेमत q. v. 2 Jocosely. The hereditary or settled (quasi fixed as a stake) जोशी of a village.मेंधला (p. 665) [ mēndhalā ] m In architecture. A common term for the two upper arms of a double चौकठ (door-frame) connecting the two. Called also मेंढरी & घोडा . It answers to छिली the name of the two lower arms or connections. (Marathi)

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda)

मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end rebus: meḍ 'iron, metal' (Ho. Munda)

Since Sivalinga as aniconic forms are also signified by चतुर्श्रि, अष्टाश्रि quadrangular, octagonal components and as iconic connotations appear with ekamukha linga (linga with one face ligatured), it is surmised that Sivalinga are Yupa skambha, as a multi-layered, metallurgical metaphor. One layer relates to the rebus reading of the ekamukha. The surmise of Sivalinga as Yupa Skambha is framed on the extraordinary metaphors of the philosophical tractus in Atharva veda called Skambha Sukta (AV X.7).

The ekamukha linga signified on such pillars atop a kiln or smelter on Bhuteswar sculptural friezes refer to mũh 'face' rebus: mũhe 'ingot', mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes, 'smelters'. (Santali) A garland is arried by a dwarf, to signify dāmā m. ʻ id., garland ʼ rebus: Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (Red ochre is Fe

2O3, takes its reddish color from the mineral hematite, which is an anhydrous iron oxide.)kharva, 'dwarfs' are associated with ekamukha śivalinga (Rudra) atop a smelter on Bhutesvar sculptural friezes, to signify wealth-producing smelted products. mũh 'a face' in Indus Script Cipher signifies mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' kharva 'dwarf' rebus: kharva 'nidhi of Kubera' karba 'iron'.

Association of Gaṇeśa with metalwork is vividly demonstrated on Candi-Sukuh sculptural frieze which shows Bhima as blacksmith, Arjuna as bellows blower and Gaṇeśa on a dance step karaṇa rebus:karana 'scribe'. karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' mẽḍha 'ram' meḍho 'helper of merchant

Thus, the spectacular series of circular workers' platforms evidenced in Harappa may be a series of tāmbā kole.l 'smithy, forge' structures working on copper metal.

This monographs demonstrates, based on decipherment of over 8000 inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora that the Mohenjo-daro brick room signifies a metalware shop. The underlying Meluhha dialect expression is: pajhar 'smelter, smithy', rebus:

Cheh Tuti Chowk or Six Tuti Chowk, Main Bazaar, is in an area called Paharganj in Old Delhi. Note the expression: Paharganj; the word pahar is likely to be the old Meluhha word to signify a metalware shop, since a cognate word pajhar signifies a smithy in Santali.

P بازار bāzār, s.m. (2nd) A market. Pl. بازارونه bāzārūnah. P بازارګيَ bāzārgaey, s.m. (1st) A small market. Pl. يِ ī.

P بازاري bāzār-ī, adj. Belonging to the market, a market person. (Pashto) bāzar बाज़र् (=। विपणिः m. a street with shops in it, a market, market-place, bazaar, mart (YZ. 40, 253, where the word is spelt bāzār, in imitation of Persian; K.Pr. 78, 103, Śiv. 1211, 1808). In Śiv. 1566 bāzār also occurs m.c. in the sense of market, i.e. traffic of the market. --aʦun --अच़ुन् । व्यसनवृत्तिः m.inf. to enter the bazaar; esp. to waste one's money in bazaar enjoyments, to lead a dissolute life. -banga -बंग । अन्नफलविशेषः f. a certain food grain, a kind of millet, akin to bājrā (Panicum spicatum or P. italicum). --ʦānun --च़ानुन् । व्यसनासञ्जनम् m.inf. to cause to enter the bazaar; to induce (a respectable youth) to lead a profligate life; to seduce to dissoluteness. --wuchun --वुछुन् । मूल्यपरीक्षणम् m.inf. to look at the bazaar; to ascertain the market rate of anything, to test the value of anything by comparison with the market price.(Kashmiri)

Santali. पाजिकः A falcon (Skt.) rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’.

"A bazaar is a permanently enclosed marketplace or street where goods and services are exchanged or sold. The term originates from the Persian word bāzār." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bazaar I submit that the root of the Persian word is traceable to many forms of pasar 'shop, spreading out' in Meluhha (mleccha) spoken form dialects of Indian sprachbund, 'speech union'. The Prakrit word is pasara ʻextensionʼ. The word seems to have originated in the Punjabi word, pahārā which signifies a goldsmith's workshop.'

Evidence for such a shop is seen in a Mohenjo-daro brick room described by John Marshall. With the evidence of a seal impression on a storage jar in Indus Script which has been deciphered in this monograph, it can be established that the shop of Mohenjo-daro is datable to ca. 3300 BCE since the first evidence of writing is also dated to ca. 3300 BCE from a potsherd of Harappa with Indus Script inscription. (cf. HARP reports).

1. VS. Area, Section A, Block I, House II: Floor in shop made of cut and rubbed brick on edge. (Marshall, Mohenjo-daro and the Indus Civilization, III, pl. LIV, a) and above, Same floor as shown below about 45 years later. https://www.harappa.com/blog/mohenjo-daro-cause-common-concern

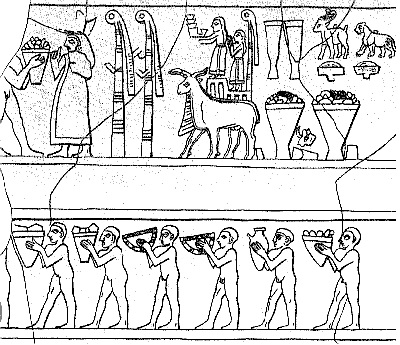

VS Area, Section A. Block I, House II: Room 23, showing brick floor with dyeing troughs

[Original 1931 caption] "House II. - Rooms 1 to 26, covering a rectangular area of 86 ft. 10 in. by 64 ft. 5 in. to the north of the building just described, appear originally to have belonged to one and the same house, which had two entrances opening into the main street on the east and another into Lane I on the north. At a subsequent date the building appears to have been divided into four separate dwellings. . .. Noteworthy features of this room are five conical pits or holes dug into the floor and lined with wedge-shaped bricks, apparently meant to hold the pointed bases of large storage jars, and what seems to have been a very narrow well in the S.E. corner. Room 2 has a small chamber screened off in its N.W. corner and a paved bath or floor for cleaning utensils in the other corner, with a covered drain to carry of waste water into the cesspit in front of Room I." [Marshall, Vol. I. p. 216]

- Pasar malam – a night market in Indonesia, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore that opens in the evening, typically held in the street in residential neighbourhoods.

- Pasar pagi – a morning market, typically a wet market that trades from dawn until midday, found in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore

Indonesia - Pasar Gambir, now Jakarta Fair, Jakarta

- id:Pasar Baru, Jakarta

- id:Pasar Turi, Surabaya

- Pasar Beringharjo, Yogyakarta

- id:Pasar Semawis, Semarang

- id:Pasar Gede Harjonagoro, Surakarta

Malaysia- Bukit Beruang Bazaar, Malacca

- Bazar Bukakbonet Gelang Patah, Johor Bahru

[quote] In Balinese, the word pasar means "market." The capital of Bali province, in Indonesia, is Denpasar, which means "north market." [unquote] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bazaar![]() Women purchasing copper utensils in a bazaar by Edwin Lord Weeks, late 19th century

Women purchasing copper utensils in a bazaar by Edwin Lord Weeks, late 19th century

pajhar 'smelter, smithy', rebus: పసారము pasāramu or పసారు pasāramu. [Tel.] n. A shop. associated triplets of hypertext clusters. Thus, clusters of animals (expanded also as a composite animal or animals shown in procession) are wealth-accounting classifiers of distinct metalwork categories related to a smelter or a smithy. prasara m. ʻ advance, extension ʼ Kālid. [√sr̥ ]Pk. pasara -- m. ʻ extension ʼ; Ku. pasar ʻ extension of family, lineage, family, household ʼ; N. pasal ʻ booth, shop ʼ; B. Or. pasarā ʻ tray of goods for sale ʼ; M. pasar m. ʻ extension ʼ; -- N. pasar ʻ the two hands placed together to receive something, one hand so held out ʼ, H. pasar m. ʻ hollowed palm of hand ʼ: rather < prasr̥ta -- .(CDIAL 8824) prasāra m. ʻ extension ʼ Suśr., ʻ trader's shop ʼ Nalac. [Cf. prasārayati ʻ spreads out for sale ʼ Mn. -- √sr̥ ] Paš. lāsar ʻ bench -- like flower beds outside the window ʼ IIFL iii 3, 113; K. pasār m. ʻ rest ʼ (semant. cf. prásarati in Ku. N. Aw.); P. puhārā m. ʻ breaking out (of fever, smallpox, &c.) ʼ; Ku. pasāro ʻ extension, bigness, extension of family or property, lineage, family, household ʼ; N. pasār ʻ extension ʼ; B. pasār ʻ extent of practice in business, popularity ʼ, Or. pasāra; H. pasārā m. ʻ stretching out, expansion ʼ (→ P. pasārā m.; S. pasāro m. ʻ expansion, crowd ʼ), G. pasār, °rɔ m., M. pasārā; -- K. pasôru m. ʻ petty shopkeeper ʼ; P. pahārā m. ʻ goldsmith's workshop ʼ; A. pohār ʻ small shop ʼ; -- ← Centre: S. pasāru m. ʻ spices ʼ; P. pasār -- haṭṭā m. ʻ druggist's shop ʼ; -- X paṇyaśālā -- : Ku. pansārī f. ʻ grocer's shop ʼ.(CDIAL 8835) prásārayati ʻ stretches out, extends ʼ VS. [√sr̥ ] Pa. pasārēti ʻ extends ʼ, Pk. pasārēi; Gy. rum. prasar<-> ʻ to win ʼ; K. pasārun, pạsa run ʻ to beat out a metal plate thin, pare off the edges of a metal plate ʼ; Ku. pasārṇo ʻ to stretch, throw, lay flat ʼ; B. pasārā tr. ʻ to spread out ʼ; Or. pasāribā ʻ to spread out, exhibit for sale ʼ; Mth. Aw. lakh. pasārab ʻ to spread out ʼ, Bhoj. pasāral, H. pasārnā, Marw. pasārṇo, G. prasārvũ, pas˚, M. pasarṇẽ, Si. paharanavā; -- with anal. -- ss -- or ← Centre: S. pasāraṇu tr. ʻ to stretch out ʼ, P. pasārṇā.Addenda: prásārayati: Garh. pasārnu ʻto spreadʼ. (CDIAL 8838) prasāˊraṇa n. ʻ spreading out ʼ ŚBr. [√sr̥ ]Pa. pasāraṇa -- n. ʻ stretching out ʼ; Si. pasaraṇa ʻ cloth spread on ground, carpet, lacquer work, enamel ʼ.(CDIAL 8836) prasārin ʻ spreading out ʼ PārGr̥. [prasāra -- ]Ku.gng. pasāri ʻ shopkeeper ʼ, A. pohāri; B. pasāri ʻ druggist, petty trader ʼ; Or. pasāri ʻ druggist, pedlar ʼ, f. °ruṇī, H. M. pasārī m. ʻ seller of spices ʼ (→ S. P. pasārī m.). -- X paṇyaśālā -- : N. pansāri ʻ grocer ʼ, H. pansārī, pãs° m. ʻ seller of spices ʼ (→ P. pansārī m.).(CDIAL 8839) *prastarati ʻ spreads out ʼ. [prástr̥ṇōti AV. -- √str̥ ]Pa. pattharati tr. ʻ spreads out, scatters ʼ, Pk. pattharaï patthuraï; L. (Ju.) patharaṇ ʻ to spread, turn over ʼ; Mth. pathrab intr. ʻ to lie scattered ʼ; G. pātharvũ tr. ʻ to spread ʼ; Si. paturanavā ʻ to spread abroad, proclaim ʼ (whence caus. paturuvanavā and intr. pätirenavā ʻ to be extended ʼ); Md. faturān ʻ to spread out ʼ; -- Pk. pattharia<-> ʻ spread out ʼ; Si. pätali ʻ flat, level, plain ʼ (rather than < pattralá -- ). -- See *prastārayati, *prastr̥ta -- .Addenda: *prastarati: S.kcch. pātharṇū ʻ to spread ʼ; caus. Ko. pātlāytā ʻ spreads out (bed, etc.) ʼ S. M. Katre, Md. faturuvanī tr. ʻ spreads ʼ, feturenī intr. (absol. feturi).(CDIAL 8850)Circular Workers' Platforms

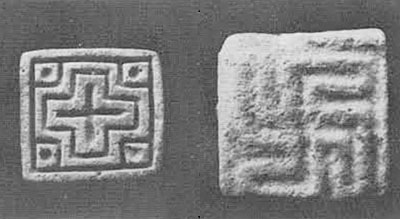

A circular platform was found inside house and small courtyard in Padri (also known as Kerala-no-dhoro), Gujarat. The floor of the house in Padri had two circular platforms in the northern and southern end with a diametre of 1.5 metres each. Two terracotta plaques of Lajjā Gaurī were found from the area adjoining this floor. The structure has been identified as a temple dedicated to the divinity.

Lajjā Gaurī is associated with the lotus in iconography. Lotus is an Indus Script hieroglyph: tāmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tāmra 'copper'. Hence, the worshipper of Lajjā Gaurī is a coppersmith.

See: Celtic-Meluhha contacts during early Bronze Age: some hypothesesThe geographic spread of ancient Celts, Hallstatt and La Tène cultures and iron age links with Britain and Ireland are unresolved controversies. (See bibliographical links at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celts).

Adding to these controversies, some hypotheses are presented:

1. Lia Fáil granite stone pillar in the Hill of Tara, County Meath, Ireland is a Meluhhan artifact signifying copper, tamba.2. The circular platform surrounding Lia Fáil is a Meluhhan artisan working platform and finds parallels in Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization, in Harappa in particular.3. The stone pillars of Lia Fáil and Dholavira are comparable and denote early gestalt of Meluhhans for denoting astambha (rebus: tamba, 'copper') as a fiery pillar, a hieroglyphic metaphor for Rudra-Shiva inferred from a Skambha Sukta in Atharvaveda.4. The Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs find echoes in hieroglyhs deployed by metalworkers on the Gundestrup silver gilded Cauldron traceable to Proto-Celtic, Hallstat and La Tene cultural traditions positing Meluhha-Celtic cultural interactions.5. Meluhha links to the treasures of Tuatha Dé Danann of Celtic-Irish tradition are relatable to Bronze Age metalwork of Meluhha artisans and traders evidenced by the Indus script hieroglyphs and artifacts of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization.

These hypotheses are premised on the decipherment of Indus writing as Meluhha metalwork hieroglyphs read rebus in Meluhha which constituted the lingua franca of the civilization in the Sarasvati-Sindhu doab with evidenced contact areas stretching along the Tin Road from Meluhha (Sarasvati-Sindhu doab) upto Haifa, Israel.I suggest that the polished granite pillar stone -- Lia Fáil --was brought by descendants of artisans of Meluhha.One speculation is that Tuatha De Danann brought the techniques of making bronze to Ireland. The supernaturally gifted people were venerated and remembered as divinities in Ireland, children of Danu, the river divinity associated with the names of rivers -- Danube, Don, Dneiper, Dniestr. Dagda, son of Danu, is cognate with dagdha 'अग्निदग्ध 'burnt with fire'. This gloss means: (pl.) a class of Manes or Pitṛis who, when alive, kept up the household flame and presented oblations to fire.

[Original 1931 caption] "House II. - Rooms 1 to 26, covering a rectangular area of 86 ft. 10 in. by 64 ft. 5 in. to the north of the building just described, appear originally to have belonged to one and the same house, which had two entrances opening into the main street on the east and another into Lane I on the north. At a subsequent date the building appears to have been divided into four separate dwellings. . .. Noteworthy features of this room are five conical pits or holes dug into the floor and lined with wedge-shaped bricks, apparently meant to hold the pointed bases of large storage jars, and what seems to have been a very narrow well in the S.E. corner. Room 2 has a small chamber screened off in its N.W. corner and a paved bath or floor for cleaning utensils in the other corner, with a covered drain to carry of waste water into the cesspit in front of Room I." [Marshall, Vol. I. p. 216]

- Pasar malam – a night market in Indonesia, Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore that opens in the evening, typically held in the street in residential neighbourhoods.

- Pasar pagi – a morning market, typically a wet market that trades from dawn until midday, found in Malaysia, Indonesia and Singapore

Indonesia

- Pasar Gambir, now Jakarta Fair, Jakarta

- id:Pasar Baru, Jakarta

- id:Pasar Turi, Surabaya

- Pasar Beringharjo, Yogyakarta

- id:Pasar Semawis, Semarang

- id:Pasar Gede Harjonagoro, Surakarta

Malaysia

- Bukit Beruang Bazaar, Malacca

- Bazar Bukakbonet Gelang Patah, Johor Bahru

[quote] In Balinese, the word pasar means "market." The capital of Bali province, in Indonesia, is Denpasar, which means "north market." [unquote] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bazaar

Women purchasing copper utensils in a bazaar by Edwin Lord Weeks, late 19th century

pajhar 'smelter, smithy', rebus: పసారము pasāramu or పసారు pasāramu. [Tel.] n. A shop. associated triplets of hypertext clusters. Thus, clusters of animals (expanded also as a composite animal or animals shown in procession) are wealth-accounting classifiers of distinct metalwork categories related to a smelter or a smithy. prasara m. ʻ advance, extension ʼ Kālid. [√sr̥ ]Pk. pasara -- m. ʻ extension ʼ; Ku. pasar ʻ extension of family, lineage, family, household ʼ; N. pasal ʻ booth, shop ʼ; B. Or. pasarā ʻ tray of goods for sale ʼ; M. pasar m. ʻ extension ʼ; -- N. pasar ʻ the two hands placed together to receive something, one hand so held out ʼ, H. pasar m. ʻ hollowed palm of hand ʼ: rather < prasr̥ta -- .(CDIAL 8824) prasāra m. ʻ extension ʼ Suśr., ʻ trader's shop ʼ Nalac. [Cf. prasārayati ʻ spreads out for sale ʼ Mn. -- √sr̥ ] Paš. lāsar ʻ bench -- like flower beds outside the window ʼ IIFL iii 3, 113; K. pasār m. ʻ rest ʼ (semant. cf. prásarati in Ku. N. Aw.); P. puhārā m. ʻ breaking out (of fever, smallpox, &c.) ʼ; Ku. pasāro ʻ extension, bigness, extension of family or property, lineage, family, household ʼ; N. pasār ʻ extension ʼ; B. pasār ʻ extent of practice in business, popularity ʼ, Or. pasāra; H. pasārā m. ʻ stretching out, expansion ʼ (→ P. pasārā m.; S. pasāro m. ʻ expansion, crowd ʼ), G. pasār, °rɔ m., M. pasārā; -- K. pasôru m. ʻ petty shopkeeper ʼ; P. pahārā m. ʻ goldsmith's workshop ʼ; A. pohār ʻ small shop ʼ; -- ← Centre: S. pasāru m. ʻ spices ʼ; P. pasār -- haṭṭā m. ʻ druggist's shop ʼ; -- X paṇyaśālā -- : Ku. pansārī f. ʻ grocer's shop ʼ.(CDIAL 8835) prásārayati ʻ stretches out, extends ʼ VS. [√sr̥ ] Pa. pasārēti ʻ extends ʼ, Pk. pasārēi; Gy. rum. prasar<-> ʻ to win ʼ; K. pasārun, pạsa run ʻ to beat out a metal plate thin, pare off the edges of a metal plate ʼ; Ku. pasārṇo ʻ to stretch, throw, lay flat ʼ; B. pasārā tr. ʻ to spread out ʼ; Or. pasāribā ʻ to spread out, exhibit for sale ʼ; Mth. Aw. lakh. pasārab ʻ to spread out ʼ, Bhoj. pasāral, H. pasārnā, Marw. pasārṇo, G. prasārvũ, pas˚, M. pasarṇẽ, Si. paharanavā; -- with anal. -- ss -- or ← Centre: S. pasāraṇu tr. ʻ to stretch out ʼ, P. pasārṇā.Addenda: prásārayati: Garh. pasārnu ʻto spreadʼ. (CDIAL 8838) prasāˊraṇa n. ʻ spreading out ʼ ŚBr. [√sr̥ ]Pa. pasāraṇa -- n. ʻ stretching out ʼ; Si. pasaraṇa ʻ cloth spread on ground, carpet, lacquer work, enamel ʼ.(CDIAL 8836) prasārin ʻ spreading out ʼ PārGr̥. [prasāra -- ]Ku.gng. pasāri ʻ shopkeeper ʼ, A. pohāri; B. pasāri ʻ druggist, petty trader ʼ; Or. pasāri ʻ druggist, pedlar ʼ, f. °ruṇī, H. M. pasārī m. ʻ seller of spices ʼ (→ S. P. pasārī m.). -- X paṇyaśālā -- : N. pansāri ʻ grocer ʼ, H. pansārī, pãs° m. ʻ seller of spices ʼ (→ P. pansārī m.).(CDIAL 8839) *prastarati ʻ spreads out ʼ. [prástr̥ṇōti AV. -- √str̥ ]Pa. pattharati tr. ʻ spreads out, scatters ʼ, Pk. pattharaï patthuraï; L. (Ju.) patharaṇ ʻ to spread, turn over ʼ; Mth. pathrab intr. ʻ to lie scattered ʼ; G. pātharvũ tr. ʻ to spread ʼ; Si. paturanavā ʻ to spread abroad, proclaim ʼ (whence caus. paturuvanavā and intr. pätirenavā ʻ to be extended ʼ); Md. faturān ʻ to spread out ʼ; -- Pk. pattharia<-> ʻ spread out ʼ; Si. pätali ʻ flat, level, plain ʼ (rather than < pattralá -- ). -- See *prastārayati, *prastr̥ta -- .Addenda: *prastarati: S.kcch. pātharṇū ʻ to spread ʼ; caus. Ko. pātlāytā ʻ spreads out (bed, etc.) ʼ S. M. Katre, Md. faturuvanī tr. ʻ spreads ʼ, feturenī intr. (absol. feturi).(CDIAL 8850)

Circular Workers' Platforms

A circular platform was found inside house and small courtyard in Padri (also known as Kerala-no-dhoro), Gujarat. The floor of the house in Padri had two circular platforms in the northern and southern end with a diametre of 1.5 metres each. Two terracotta plaques of Lajjā Gaurī were found from the area adjoining this floor. The structure has been identified as a temple dedicated to the divinity.

Lajjā Gaurī is associated with the lotus in iconography. Lotus is an Indus Script hieroglyph: tāmarasa 'lotus' rebus: tāmra 'copper'. Hence, the worshipper of Lajjā Gaurī is a coppersmith.

See: Celtic-Meluhha contacts during early Bronze Age: some hypotheses

The geographic spread of ancient Celts, Hallstatt and La Tène cultures and iron age links with Britain and Ireland are unresolved controversies. (See bibliographical links at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Celts).