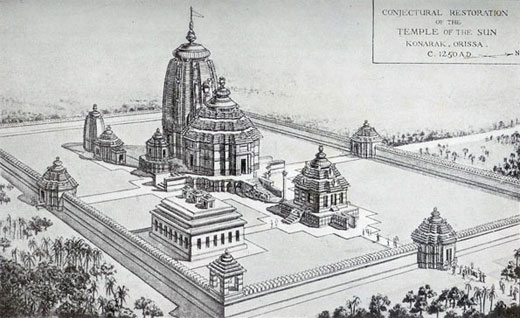

I suggest that Indus Script writing system invented ca. 3300 BCE, making it the world's oldest writing system, can be classified, consistent with the expressions recorded from very ancient texts, by Vātsyāyana as mlecchita vikalpa and in Lalita Vistara to specify two of the 64 writing systems as: 1. nikṣepavarta lipi and 2. utkṣepavarta lipi. (Translations: Incised metalwork ledgers, bas relief metalwork ledgers).

Vātsyāyana is the name of an ancient Indian philosopher, known for writing the Kāma Sūtra, the most famous book in the world on human sexuality. This work includes a chapter called vidyaā samuddeśa, 'objective of education' and includes a list of 64 arts learned by youth.. He lived in India during the second or third century CE, probably in Pataliputra (modern day Patna). Lalita Vistara is a Pali text dated to first millennium BCE since a translation of the work in Chinese is dated 308 CE.

I suggest that both Vātsyāyana and Lalita Vistara are perhaps first millennium BCE signifiers of the knowledge of writing systems in ancient Bhāratam.

![]() An example of utkṣepavarta lipi. Bas-relief writing on metal from Harappa. h2249A Text 3247

An example of utkṣepavarta lipi. Bas-relief writing on metal from Harappa. h2249A Text 3247

baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus: baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) bhārata ‘a factitious alloy of copper, pewter, tin’ (Marathi) dula ‘pair’ Rebus: dul ‘cast metal’. The cast metal is pewter.

goTa 'round pebble' rebus: goTa 'laterite ferrous ore'. dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal'

Thus, the inscription reads rebus: dul goTa PLUS bharat, i.e., 'cast laterite PLUS pewter'

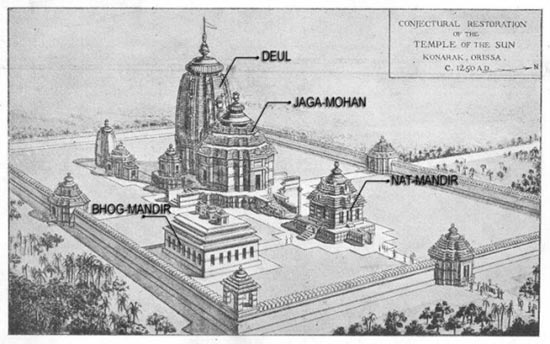

The word Meluhha is attested in cuneiform text of a cylinder seal of Shu Ilishu, Meluhha interpreter. The rollout of Shu-ilishu's Cylinder seal. Courtesy of the Department des Antiquites Orientales, Musee du Louvre, Paris. The cuneiform text reads: Shu-Ilishu EME.BAL.ME.LUH.HA.KI (interpreter of Meluhha language). Apparently, the Meluhhan is the person carrying the antelope on his arms.

![]()

![]()

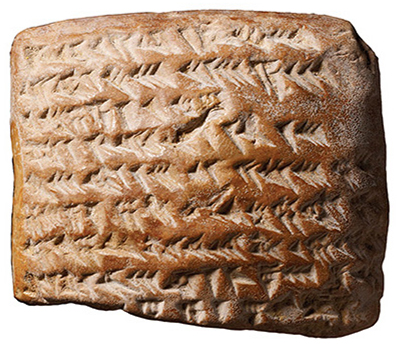

![]() m1457A,B An example of nikṣepavarta lipi. Incised writring on metal from Mohenjo-daro. m1457A Copper tablet

m1457A,B An example of nikṣepavarta lipi. Incised writring on metal from Mohenjo-daro. m1457A Copper tablet

m1457Bct Text 2904 Pict-124: Endless knot motif. The hypertext on two lines are read rebus:

Hieroglyph: मेढा [ mēḍhā ] 'a curl or snarl; twist in thread' (Marathi) .L. meṛh f. ʻrope tying oxen to each other'.mer.ha = twisted, crumpled, as a horn (Santali.lex.) meli, melika = a turn, a twist, a loop, entanglement. Viewed as a string or strand of rope, the gloss is read rebus as dhāu ʻore (esp. of copper)ʼ. The specific ore is:

![]() med 'copper' (Slavic languages)

med 'copper' (Slavic languages)

dhāˊtu *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.) S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773 ) Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn.Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ)(CDIAL 6773).

Line 1: ad.ar 'harrow'; rebus: aduru 'native metal, unsmelted' (Kannada)

baTa 'warrior' rebus: bhaTa 'furnace'

karNika 'rim of jar' rebus: karNI 'supercargo'; karNaka 'account'. Alternative: kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: kanga 'brazier'.

Line 2: ad.ar 'harrow'; rebus: aduru 'native metal, unsmelted' (Kannada)

aya 'fish' rebus: aya, ayas 'iron''metal'

dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' PLUS goTa 'round' rebus: goTa 'laterite ore'

mū̃h ‘ingot’ (Santali) dula 'pair' Rebus: dul 'cast metal' Thus, cast metal ingot of laterite and implements.

Thus, the hieroglyph-multiplex signifies cast metal of laterite ore pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali) Rebus: pasra 'smithy' (Santali) kolom,

Alternative: kolma 'rice plant' rebus: kolime 'furnace' (Kannada) kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Telugu); kolame 'deep pit' (Tulu)

Decipherment

Thus, read together with Lines 1 and 2 of Hypertext, the copper plate m1457 with the 'endless knot' hieroglyph signifies: copper smithy. The descriptive glosses of the metalwork catalogue are: karNi 'supercargo' of med 'copper', dhāu 'metal'; kolimi 'furnace'; dul goTa kaNDa 'cast laterite ore implements'; ayas 'metal alloy'; furnace for aduru 'native (unsmelted) metal'.Alternative: kanka 'rim of jar' rebus: kanga 'brazier'.

Ancient text Lalita Vistara mentions 64 types of scripts used in ancient India. LalitaVistara itself is an ancient text and was translated in Chinese in 308CE. Some prominent scripts were Brahmi, Kharoshthi, Vanga(Bengali?), CīnaLipi(script of China?), Hūna(of Hūna) etc. The text is dated to ca. 3rd century CE.

अङ्गुलीय lipi is one of the 64 writing systems listed in Lalita Vistara. This expression signifies: अङ्गुलीय aṅgulîya finger-ring; -ka, n. id.; -mudrakâ, f. seal-ring. अङ्गुली aṅgulî finger; toe; -mudrâ, f. finger-mark. अङ्गुलिपर्वन्् aṅguli-parvan finger-joint; -pranegana, n. water for washing the fingers; -mukha, n. finger-tip; -mudrâ, f. seal-ring; -sphotana, n. cracking the fingers.

This is consistent with one of the 64 arts identified by Vātsyāyana. He refers to three arts related to language:

akṣara muṣṭika kathanam, deśa bhāṣā jñānam, mlecchita vikalpa.

akṣara muṣṭika kathanam can be explained as a writing system for messaging, using finger-tips.

deśa bhāṣā jñānam signifies that the art relates to learning of a spoken form, a dialect of language of the times.

mlecchita vikalpa is an expression which signifies the spoken forms of mleccha 'copper (metal)' words of spoken, mispronounced words. वि--कल्प alternation , alternative , option S3rS. Mn. VarBr2S. &c ( °पेन ind. " optionally "); contrivance , art Ragh.; mental occupation , thinking; (in rhet.) antithesis of opposites Prata1p.; (in gram.) admission of an option or alternative , the allowing a rule to be observed or not at pleasure (वे*ति विकल्पः Pa1n2. 1-1 , 44 Sch.); a collateral form VarBr2S.; mfn. different BhP. (Monier-Williams). 1. writing by metal (mleccha, 'copper') artisans (Comparable to the अङ्गुलीय lipi, finger-writing listed by Lalita Vistara)

2. optional form of expression (Lalita vistara elaborates two types of form and function in lipi: 1. nikṣepavarta lipi and 2. utkṣepavarta lipi.which are elucidations of 1. incised writing on metals production and trade and 2. bas-relief systems of writing on metals production and trade.

3. rebus, alternative, optional representation involving antithesis of opposites, which can specifically refer tocontrivance, cipher --rebus use of similar sounding words of homonyms signified by a writing system with hypertexts, hieroglyphs. This may be an explanation of शास्त्रावर्त लिपि (Varta relates to metal), i.e. related to metalwork, a body of teaching (in general) , scripture , science Ka1v. Pur. गणनावर्त लिपि gaṇanāvartalipi 'wealth,metals accounting' (Monier-Williams) किरात लिपि refers to a writing system of mleccha (Meluhha): m. pl. N. of a degraded mountain-tribe (inhabiting woods and mountains and living by hunting , having become शूद्रs by their neglect of all prescribed religious rites ; also regarded as म्लेच्छs ; the Kirrhadae of Arrian) VS. xxx , 16 Ta1n2d2yaBr. Mn. x , 44 MBh. &c (Monier-Williams) A cognate wor may signify a merchant (of metals): kirāṭa m. ʻ merchant ʼ Rājat., kirīṭa -- 2 m. BhP., kírāta- m. ʻ a degraded mountain tribe ʼ VS., cilātī -- f. ʻ woman of this tribe ʼ YogH. [Alternance of k -- and c -- , -- ṭ -- and -- t<-> suggests Drav. origin, EWA i 211. Perh. same as kilāta -- ʻ dwarf ʼ]Pa. kirāṭa -- m. ʻ fraudulent merchant ʼ (kirāṭa -- , ˚āta<-> m. ʻ man of a jungle tribe ʼ see kilāta -- ); Pk. kirāḍa -- , ˚āya -- , cilāa -- m., f. ˚āī -- , ˚āiyā -- ʻ a non -- Aryan tribe, slave ʼ, cilāī -- f.; S. kirāṛu m. ʻ Hindu shopkeeper ʼ; L. kirāṛ, karāṛ m., kirāṛī f. ʻ member of a tribe of Hindus (also called aroṛā) who act as traders and moneylenders ʼ; H. kirāṛ m. ʻ merchant ʼ. -- Deriv. Pa. kērāṭika -- , ˚iya<-> ʻ false ʼ (cf. kirāsa -- ʻ fraudulent ʼ); -- L. kirṛakkā ʻ connected with Hindus ʼ.(CDIAL 3173)

म्लेच्छ mlekkh-á foreigner, barbarian (Br., C.); ignorance of the vernacular, barbarism (rare): -taskara-sevita, pp. infested by barbarians and robbers; -tâ, f. condition of barbarians.(Monier-Williams). म्लेच्छः mlēcchḥ म्लेच्छः [म्लेच्छ्-घञ्] 1 A barbarian, a non-Āryan (one not speaking the Sanskṛit language, or not con- forming to Hindu or Āryan institutions), a foreigner in general; ग्राह्या म्लेच्छप्रसिद्धिस्तु विरोधादर्शने सति J. N. V.; म्लेच्छान् मूर्छयते; or म्लेच्छनिवहनिधने कलयसि करवालम् Gīt.1. -2 An outcast, a very low man; (Baudhāyana thus defines the word:-गोमांसखादको यस्तु विरुद्धं बहु भाषते । सर्वा- चारविहीनश्च म्लेच्छ इत्यभिधीयते ॥). -3 A sinner, wicked person. -4 Foreign or barbarous speech -च्छम् 1 Copper. -2 Vermilion. -Comp. -आख्यम्copper. -आशः wheat. -आस्यम्, -मुखम् copper. -कन्दः garlic. -जातिः f. a savage or barbarian race, a mountaineer; पुलिन्दा नाहला निष्ट्याः शबरा वरुटा भटाः । माला भिल्लाः किराताश्च सर्वे$पि म्लेच्छजातयः ॥ Abh. Chin.934. -देशः, -मण्डलम् a country inhabited by non-Āryans or barbarians, a foreign or barbarous country; कृष्णसारस्तु चरति मृगो यत्र स्वभावतः । स ज्ञेयो यज्ञियो देशो म्लेच्छदेशस्त्वतः परः ॥ Ms.2.23. -द्विष्टःbdellium. -भाषा a foreign language. -भोजनः wheat. (-नम्) barley. -वाच् a. speaking a barbarous or foreign language; म्लेच्छवाचश्चार्यवाचः सर्वे ते दस्यवः स्मृताः Ms.1.45.म्लेच्छनम् mlēcchanam म्लेच्छनम् 1 Speaking indistinctly or confusedly. -2 Speaking in a barbarous tongue. म्लेच्छित mlēcchita म्लेच्छित p. p. Spoken indistinctly or barbarously. -तम् 1 A foreign tongue. -2 An ungrammatical word or speech. म्लेच्छितकम् mlēcchitakam म्लेच्छितकम् Foreign or barbarous speech.(Apte) mlēcchá ʻ non -- Aryan ʼ ŚBr. [√mlēch] Pk. maleccha -- , miliccha -- , meccha -- , miccha -- m. ʻ barbarian ʼ; K. mī˜ċh, dat. mī˜ċas m. ʻ non -- Hindu ʼ (loss of aspiration unexpl.); P. milech, mal˚ m. (f. milechṇī, mal˚) ʻ Moslem, unclean outcaste, wretch ʼ; WPah.bhad, məle_ċh ʻ dirty ʼ; B. mech ʻ a Tibeto -- Burman tribe ʼ ODBL 473; Si. milidu, miliñdu ʻ wild, savage ʼ (< MIA. *mlēcha -- or with H. Smith JA 1950, 186 X pulindá -- ), milis (< MIA. miliccha -- ). -- Paš. mečə ʻ wretched, miserly ʼ rather < *mēcca -- ʻ defective ʼ. -- With unexpl. -- kkh -- : Pa. milakkha -- , ˚khu -- ʻ non -- Aryan ʼ, Si. malak ʻ savage ʼ, malaki -- dū ʻ a Väddā woman ʼ. -- X piśācá -- : Pa. milāca -- m. ʻ wild man of the woods, non -- Aryan ʼ; Si. maladu ʻ wild, savage ʼ.(CDIAL 10389)

'To speak indistinctly' is the key characteristic of mleccha,meluhha speech, i.e. with mispronunciations in Bhāratiya sprachbund (speech union)

*mlēcchatva ʻ condition of a non -- Aryan ʼ. [Cf. mlēcchatā -- f. VP. -- mlēcchá -- ] K. mīċuth, dat. ˚ċatas m. ʻ habit or life of an outcaste ʼ. MLĒCH ʻ speak indistinctly ʼ: *mrēcchati, mlēcchá -- .(CDIAL 10390)

*mrēcchati ~ mlḗcchati ʻ speaks indistinctly ʼ ŚBr. [MIA. mr -- < ml -- ? See Add. -- √mlēch]

K. briċhun, pp. bryuċhu ʻ to weep and lament, cry as a child for something wanted or as motherless child ʼ.(CDIAL 10384)

"Concerning the origins of the text, the Dharmachakra Translation Committee states:

- This scripture is an obvious compilation of various early sources, which have been strung together and elaborated on according to the Mahāyāna worldview. As such this text is a fascinating example of the ways in which the Mahāyāna rests firmly on the earlier tradition, yet reinterprets the very foundations of Buddhism in a way that fit its own vast perspective. The fact that the text is a compilation is initially evident from the mixture of prose and verse that, in some cases, contains strata from the very earliest Buddhist teachings and, in other cases, presents later Buddhist themes that do not emerge until the first centuries of the common era. Previous scholarship on The Play in Full (mostly published in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries) devoted much time to determining the text’s potential sources and their respective time periods, although without much success. [...] Although this topic clearly deserves further study, it is interesting to note that hardly any new research on this sūtra has been published during the last sixty years. As such the only thing we can currently say concerning the sources and origin of The Play in Fullis that it was based on several early and, for the most part, unidentified sources that belong to the very early days of the Buddhist tradition." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lalitavistara_S%C5%ABtra

Delineating Meluhha (Mleccha) language of ca. 4th millennium BCE, a date of Bronze Age which produced evidence of the earliest writing on a Harappa potsherd is a philological challenge.

Harappa. Potsherd. Indus writing (HARP) dated to ca. 3500 BCE. tagaraka 'tabernae montana' rebus: tagara 'tin'.

Attempts can be made to respond to this challenge using a variety of textual resources available, apart from using the Indus Writing corpora as a frame of reference to validate the Meluhha (Mleccha) words. This note discusses some resources provided by studies related to ancient Indian languages which contributed to the Indiansprachbund.

Ancient arts related to communicating ideas

Vātsyāyana’s Kāmasūtra refers to a cipher called mlecchita vikalpa (alternative representation in writing of mleccha(Meluhha) language) as one of the 64 arts to be learnt by youth. Vātsyāyana also uses the phrase deśabhāṣā jñānamreferring to the learning of vernacular languages and dialects. deśabhāṣā is also variously referred to as deśī or deśya.He also uses the phrase akṣara muṣṭikā kathanam as another of the 64 arts. This is a reference to karaṇa or karaṇīmentioned in Bharata’s Nāṭyaśāstra as gesticulation or articulation in dance using positions of finger-knuckles and wrists to convey messages or bhāvá ‘thought or disposition’. akṣara muṣṭikā is explained by Monier-Williams (p. 3) as: ‘the art of communicating syllables or ideas by the fingers (one of the 64 kalās, Vātsyāyana)’.

करण the occupation of this class is writing , accounts (Monier-Williams, p. 254) n. (in law) an instrument , document , bond Mn. viii , 51 ; 52 ; 154. m. writer , scribe. n. the special business of any tribe or caste

करणी f. a particular position of the fingers (Monier-Williams, p. 254) n. pronunciation , articulation , APrāt.करण n. the act of making , doing , producing , effecting S3Br. MBh. &c (very often ifc. e.g. मुष्टि-क्° , विरूप-क्°) Pori ‘the joints of a bamboo, a cane, or the fingers’ (Maltese)(DEDR 4541). Pkt. pora- joint (CDIAL 8406).

Meluhha is cognate mleccha. Mleccha were island-dwellers (attested in Mahabharata and other ancientIndian sprachbund texts). Their speech did not conform to the rules of grammar (mlecchāḥ mā bhūma iti adhyeyam vyākaraṇam) and had dialectical variants or unrefined sounds in words (mlecchitavai na apabhāṣitavai) (Patanjali: Mahābhāṣya).

Prākṛitarūpāvatāra literally means ‘the descent of Prākṛit forms’. Pischel noted: “…the Prākṛitarūpāvatāra is not unimportant for the knowledge of the declension and conjugation, chiefly because Simharāja frequently quotes more forms than Hēmachandra and Trivikrama. No doubt many of these forms are theoretically inferred; but they are formed strictly according to the rules and are not without interest.” (Pischel, 1900, Grammatik der Prākṛit-Sprachen, Strassburg, p.43). Pischel also had written a book titled, Hēmachandra's Prākṛit grammar, Halle, 1877. The full text of the Vālmīkisūtra, with gaṇas, dēśīyas, and iṣṭis, has been printed in Telugu characters at Mysore in 1886 as an appendix to the ṣaḍbhāṣachandrikā.

A format to determine the structure of Prākṛit is to identify words which are identical with Sanskrit words or can be derived from Sanskrit. In this process, dēśīyas or dēśyas, ‘provincialisms’ are excluded. One part of the work of Simharja is samjñāvibhāga ‘technical terms’. Another is pari bhāṣāvibhāga ‘explanatory rules’. Dialects are identified in a part called śaurasēnyādivibhāga; the dialects include: śaurasēni, māgadhī, paiśācī, chūḷikā paiśācī, apabhramśa.

Additional rules are identified beyond those employed by Pāṇini:

sus, nominative; as, accusative; ṭās, instrumental; nēs, dative; nam, genitive; nip, locative.

Other resources available for delineation of mleccha are: The Prākṛita-prakāśa; or the Prākṛit grammar of Vararuchi. With the commentary Manorama of Bhamaha. The first complete ed. of the original text... With notes, an English translation and index of Prākṛit words; to which is prefixed a short introd. to Prākṛit grammar (Ed. Cowell, Edward Byles,1868, London, Trubner)

On these lines, and using the methods used for delineating Ardhamāgadhi language, by Prākṛita grammarians, and in a process of extrapolation of such possible morphemic changes into the past, an attempt may be made to hypothesize morphemic or phonetic variants of mleccha words as they might have been, in various periods from ca. 4th millennium BCE. There are also grammars of languages such as Marathi (William Carey), Braj bhāṣā grammar (James Robert), Sindhi, Hindi, Tamil (Tolkāppiyam) and Gujarati which can be used as supplementary references, together with the classic Hemacandra's Dēsīnāmamālā, Prākṛit Grammar of Hemachandra edited by P. L. Vaidya (BORI, Pune), Vararuchi's works and Richard Pischel's Comparative Grammar of Prākṛit Languages.(Repr. Motilal Banarsidass, 1957). Colin P. Masica's Indo-Aryan Languages, Cambridge University Press, 1993,"... has provided a fundamental, comparative introduction that will interest not only general and theoretical linguists but also students of one or more languages (Hindi, Urdu, Bengali, Punjabi, Gujurati, Marathi, Sinhalese, etc.) who want to acquaint themselves with the broader linguistic context. Generally synchronic in approach, concentrating on the phonology, morphology and syntax of the modern representatives of the group, the volume also covers their historical development, writing systems, and aspects of sociolinguistics." Thomas Oberlies' Pali grammar (Walter de Gruyter, 2001) presents a full description of Pali, the language used in the Theravada Buddhist canon, which is still alive in Ceylon and South-East Asia. The development of its phonological and morphological systems is traced in detail from Old Indic (including mleccha?). Comprehensive references to comparable features and phenomena from other Middle Indic languages mean that this grammar can also be used to study the literature of Jainism. Madhukar Anant Mehendale's Historical Grammar of Inscriptional Prākṛit s is a useful aid to delineate changes in morphemes over time. A good introduction is: Alfred C. Woolner's Introduction to Prākṛit , 1928 (Motilal Banarsidass). "Introduction to Prākṛit provides the reader with a guide for the more attentive and scholarly study of Prākṛit occurring in Sanskrit plays, poetry and prose--both literary and inscriptional. It presents a general view of the subject with special stress on Sauraseni and Maharastri Prākṛit system. The book is divided into two parts. Part I consists of I-XI Chapters which deal with the three periods of Indo-Aryan speech, the three stages of the Middle Period, the literary and spoken Prākṛit s, their classification and characteristics, their system of Single and Compound Consonants, Vowels, Sandhi, Declension, Conjugation and their history of literature. Part II consists of a number of extracts from Sanskrit and Prākṛit literature which illustrate different types of Prākṛit --Sauraseni, Maharastri, Magadhi, Ardhamagadhi, Avanti, Apabhramsa, etc., most of which are translated into English. The book contains valuable information on the Phonetics and Grammar of the Dramatic Prākṛit s--Sauraseni and Maharastri. It is documented with an Index as well as a Students'. " It may be noted that Hemacandra is a resource which has provided the sememe ibbo 'merchant' which reads rebus with ibha 'elephant' hieroglyph.

Sir George A. Grierson's article on The Prākṛit Vibhasas cites: "Pischel, in §§3, 4, and 5 of his Prākṛit Grammar, refers very briefly to the Vibhāṣās of the Prākṛit grammarians. In § 3 he quotes Mārkaṇḍēya's (Intr., 4) division of the Prākṛit s into Bhāṣā, Vibhāṣā, Apabhraṁśa, and Paiśāca, his division of the Vibhāṣās into Śākārī, Cāṇḍālī, Śābarī, Ābhīrikā, and Ṭākkī (not Śākkī, as written by Pischel), and his rejection of Auḍhrī (Pischel, Oḍrī) and Drāviḍī. In § 4 he says, “Rāmatarkavāgīśa observes that the vibhāṣāḥcannot be called Apabhraṁśa, if they are used in dramatic works and the like.” He repeats the latter statement in § 5, and this is all that he says on the subject. Nowhere does he say what the term vibhāṣā means. The present paper is an attempt to supply this deficiency." See also: http://www.indianetzone.com/39/Prākṛit _language.htm

"...Ganga, on the lower reaches of which were the kingdoms of Anga, Variga, and Kalinga, regarded in the Mahabharata as Mleccha. Now the non- Aryan people that today live closest to the territory formerly occupied by these ancient kingdoms are Tibeto-Burmans of the Baric branch. One of the languages of that branch is called Mech, a term given to them by their Hindu neighbors. The Mech live partly in Bengal and partly in Assam. B(runo) Lieblich remarked the resemblance between Mleccha and Mech and that Skr. Mleccha normally became Prākṛit Meccha or Mecha and that the last form is actually found in Sauraseni. 1 Sten Konow thought Mech probably a corruption of Mleccha.* I do not believe that the people of the ancient kingdoms of Anga, Vanga, and Kalinga were precisely of the same stock as the modern Mech, but rather that they and the modern Mech spoke languages of the Baric division of Sino-Tibetan. " (Robert Shafer, 1954, Ethnography of Ancient India, Otto Harras Sowitz, Wiesbaden).http://archive.org/stream/ethnographyofanc033514mbp/ethnographyofanc033514mbp_djvu.txt

The following note is based on: Source: MK Dhavalikar, 1997, Meluhha, the land of copper, South Asian Studies, 13:1, 275-279 (embedded document appended):

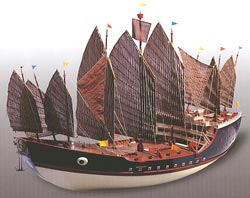

Citing a cuneiform tablet inscription of Sargon of Akkad (2370-2316 BCE), Dhavalikar notes that the boats of Dilmun, Magan and Meluhha were moored at the quay in his capital (Leemans, WF, 1960, Foreign Trade in the Old Babylonian Period as revealed by texts from Southern Mesopotamia, EJ Brill, Leiden, p. 11). The goods imported include agate, carnelian, shell, ivory, varieties of wood and copper. Dhavalikar cites a reference to the people or ‘sons’ of Meluhha who had undergone a process of acculturation into Mesopotamian society of Ur III times cf. Parpola, S., A. Parpola and RH Brunswwig, Jr., 1977, The Meluhha Village: evidence of acculturation of Harappan traders in the late Third Millennium Mesopotamia, JESHO, 20 , p.152. Oppenheim describes Meluhha as the land of seafarers. (Oppenheim, AL, 1954, The seafaring merchants of Ur, JAOS, 74: 6-17). Dhavalikar notes the name given to a rāga of classical Indian (Hindustani) music – maluha kedār – which may indicate maluha as a geographical connotation as in the name of another rāga called Gujarī Todi. Noting a pronunciation variant for meluhha, melukkha, the form is noted as closer to Prākṛit milakkhu (Jaina Sūtras, SBE XLV, p. 414, n.) cognate Pali malikkho or malikkhako (Childer’s Pali Dictionary). Prākṛit milakkhu or Pali malikkho are cognate with the Sanskrit word mleccha (References cited include Mahabharata, Patanjali). Jayaswal (Jayaswal, KP, 1914, On the origin of Mlechcha, ZDMG, 68: pp. 719-720) takes the Sanskrit representation to be cognate with Semitic melekh (Hebrew) meaning ‘king’.

Śathapatha Brāhmaṇa [3.2.1(24)], a Vedic text (ca. 8th century BCE) uses the word mleccha as a noun referring to Asuras who ill-pronounce or speak an imprecise language: tatraitāmapi vācamūduḥ | upajijñāsyāṃ sa mlecastasmānna brāhmaṇo mlecedasuryāhaiṣā vā natevaiṣa dviṣatāṃ sapatnānāmādatte vācaṃ te 'syāttavacasaḥ parābhavanti ya evametadveda. This is a remarkable reference to mleccha (meluhha) as a language in the ancient Indian tradition. Pali texts Digha Nikāya and Vinaya, also denotes milakkha as a language (milakkha bhāsā). Comparable to the reference in Manu, a Jaina text (Pannavana, 1.37) also described two groups of speakers (people?): ārya and milakkhu. Pāṇini also observes the imprecise nature of mleccha language by using the terms: avyaktayam vāci (X, 1663) and mleccha avyakte śabde (1.205). This is echoed in Patanjali’s reference to apaśabda.

Dhavalikar notes: “Sengupta (1971) has made out a strong case for identifying mlecchas with the Phoenicians. He proposes to derive the word mleccha from Moloch or Molech and relates it to Melek or Melqart which was the god of the Phoenicians. But the Phoenicians flourished in the latter half of the second and the first half of the first millennium when the Harappan civilization was a thing of the past.” (: MK Dhavalikar, 1997, Meluhha, the land of copper, South Asian Studies, 13:1, p. 276).

Worterbuch (St. Petersburg Dictionary), Hemacandra’s Abhidāna Cintāmaṇi (IV.105), lexicons of Monier Williams and Apte give ‘copper’ as one of the meanings of the lexeme mleccha.

Gudea (ca. 2200 BCE) under the Lagash dynasty brought usu wood and gold dust and carnelian from Meluhha. Ibbi-Sin (2029-2006 BCE) under the third dynasty of Ur “imported from Meluhha copper, wood used for making chairs and dagger sheaths, mesu wood, and the multi-coloured birds of ivory.”

Dhavalikar argues for the identification of Gujarat with Meluhha (interpreted as a region and as copper ore of Gujarat) and makes a reference to Viṣṇu Purāṇa (IV,24) which refers to Gujarat as mleccha country.

Nicholas Kazanas has demonstrated that Avestan (OldIranian) is much later than Vedic. "'Vedic and Avestan' by N. Kazanas In this essay the author examines independent linguistic evidence, often provided by iranianists like R. Beekes, and arrives at the conclusion that the Avesta, even its older parts (the gaθas), is much later than the Rigveda. Also, of course, that Vedic is more archaic than Avestan and that it was not the Indoaryans who moved away from the common Indo-Iranian habitat into the Region of the Seven Rivers, but the Iranians broke off and eventually settled and spread in ancientv Iran." http://www.omilosmeleton.gr/pdf/en/indology/Vedic_and_Avestan.pdf

The oldest Prākṛit lexicon is the work of a Jaina scholar, Paiyalacchi nāmamālā of Dhanapāla (972 A. D.)

Mahapurana of Pushpadanta–A critical study: By Dr Smt. Ratna Nagesha Shriyan. L. D. Bharatiya Samskriti Vidyamandira, Ahmadabad–9 . Price: Rs. 30.

A thesis approved for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy by the Bombay University, this is a critical study of the Desya and rare material contained in the three Apabhramsa works of Pushpadanta, a major Apabhramsa poet of the Ninth Century CE D.

The first part mainly deals with the nature and character of Desya element and the role of Desya element in Prākṛit and Apabhramsa in general and Pushpadanta’s works in particular. The authoress pointed out that the term Deśī has been used in the earlier Sanskrit and Prākṛit literature mainly in three different senses, viz., (1) a local spoken dialect (2) a type of Prākṛit , (3) and as equivalent to Apabhramsa. The interpretations of the word Deśī as given by Hemachandra and modern scholars are also given in detail. The authoress comes to the conclusion that most of the modern scholars agree that “Desya or Deśī is a very loose label applied by early grammarians and lexicographers to a section of Middle Indo-Aryan lexical material of a heterogeneous character.

In part II, the more important one, the learned Doctor has collected 1430 words and divided them into seven categories– (1) items only derivable from Samskrit (2) Tadbhavas with specialized or changed meaning (3) items partly derivable from Samskrit (4) items that have correspondents only in late Samskrit (5) onometopoetic words (6) foreign loans and (7) pure Deśī words. Critical and comparative notes on their meanings and interpretations, with corroborating passages from original texts are also given here and they evidence the high scholarly labours of the authoress. We cannot, but respect the words of Dr H. C. Bhayani of the Gujarat University in whose opinion the present study paves “the way for investigating the bases and authenticity of Hemachandra’s Deśīnāmamālā and provides highly valuable material for middle and Modern Indo-Aryan lexicography.”

“Words which are not derived from Sanskrit in his grammar, which though derived from Sanskrit, are not found in that sense in the Sanskrit lexicons, which have changed their meaning in Prākṛit , the change not being due to the secondary or metaphorical use of words, and which are used in standard Prākṛit from times immemorial, are considered as deśī by Hemacandra (I,3,4). Thus, he teaches in his grammar (IV,2) that pajjar is one of the substitutes of the root kath in Prākṛit . In II,136 he says that trasta assumes the forms hittha and taTTha in Prākṛit . The words pajjara, hittha and taTTha are not, therefore, des’yas and are excluded from the work. The Verbal substitutes have been, as a matter of fact, considered as deśī words by Hemacandra’s predecessors (1.11,13,20). Again the word amayaNiggamo signifies the moon in Prākṛit , and it is evidently a bhava of amrutanirgama which by some such analysis as amrutaanirgamo yasyacan denote the moon But the Sanskrit word is not found in that sense in any of the lexicons and hence amayaNiggamo is reckoned as a deśya and taught in this work. The word yayillo is a regular derivative of baliivarda according to rules of Prākṛit grammar, and as the latter word can by the force of lakshaNa mean a ‘fool’, the word vayillo in this sense is not considered a deśī word and, therefore, is not included in this work. Every provincial expression is not considered a deśī word, but only those which have found entrance into the known Prākṛit literature. Otherwise, the number of deśī words will be innumerable and it will be impossible to teach them all. As Hemacandra himself says (I,4): vacaspaterapi matirna prabhavati divyayugasahasreNa. This definition of a deśī word does not appear to have been followed by the predecessors of Hemacandra; and therein consists, he says, the superiority of his work over that of others. He quotes in a number of places words which have been taught as deśī words by his predecessors and shows that they are derived from Sanskrit words. Thus in I.37 Hemacandra says that the words acchoDaNam, alinjaramk, amilaayam andacchabhallo are considered as deśī words by some authors, but he does not do so as they are evidently derived from Sanskrit words. Again in II.89, he says that the word gamgarii is taught a a deśī word by some authors but Hemacandra says this is not a deśī word as it is derived from Sanskrit gargarii. But here our author shows some latitude and says that it may be considered a deśī word. Many such instances may be quoted and in most cases Hemacandra gives the Sanskrit equivalents to such words.” (Paravastu Venkata Ramanujaswami, in: Introduction, The Deśīnāmamālā of Hemachandra ed. By R. Pischel, 1938, 2nd edn., Dept. of Public Instruction, Bombay, pp.3-4).

TABLE : DICTIONARIES

PRĀKṛIT :

10 C.E : Deshi Nama Mala (Hemachandra)

11 C.E ![]() ayyalacchi Nama Mala (Maha Kavi Dhanapala)

ayyalacchi Nama Mala (Maha Kavi Dhanapala) 12 C.E :Abhidana Rajendra (Vijayendra Suri)

SANSKRIT

4 C.E : Amarakosha (Amarasimha) Dhanvantari Nighantu (Dhanvantari)

6 C.E : Anekartha Samucchaya (Shashaavata)

10 C.E : Abhidana Ratna Mala (Hemachandra ),Srikanda Shesha Vishvakosha (Srikanda Shesha),HaravaLi (Purushottama Deva) ,Abhidana Ratnamala (Halayudha)

11 C.E :Vyjayanti (Yadava Prakasha), Nama Mala (Dhananjaya) , Anekartha Nama Mala (Amara Keerti) , Shabdha Pradipa (Sureshvara)

12 C.E :Namarthaarnava Sankshepa , Shabda Kalpa Druma (Keshava Svamin ), Vishva Prakasha (Maheshvara) , Namartha Ratnamala (Abhaya Pala) , Abidana Cintamani +Anekartha Sangraha (Hemachandra) , Anekartha Kosha (Mankha) , Akyata Candrika (Malla Bhatta) , Raja Nighantu (Narahari)

14 C.E : Nanartha Ratna Mala (Irugappa Dandanatha) , Madana Vinoda Nighantu (Madana Pala)

15 C.E : Shabda Chandrike ( Vamana Bhatta) , Shabda Ratnakara(Bana)

16 C.E :Sundara Prakashabdarnava (Padma Sundara)

17 C.E :Kalpa Druma (Keshava Daivajna), Nama Sangraha Mala(Appaiah Dikshita)

TAMIL :

10 C.E – Sendan Divakaram (Divakaram) , Pingalantai (Pingalar)

12 C.E : Chudamani Nighantu (Mangala Puttiran)

16 C.E : Chudamani Nighantu ( Mandala Purutan) ,Akaradi Nighantu (Chidambara Revana)

17 C.E : Uriccol Nighantu (Gangeyan) , Kayataram (Kayatarar) ,Bharati Deepam (Anonymus) , Ashiriya Nighantu (Anonymus)

18 C.E : Pothigai Nighantu (Swaminatha Kavirayar), Pal Porul Chudamani (Eshwara Bharati) , Arumpporul Vilakka Nighantu (Anonymus)

KANNADA

10 C.E : Ranna Kanda (Ranna)

11 C.E : Abhidana Vastu Kosha (Nagavarma-2) ,Abhidana Ratna Mala+Amarakosha Bhashya (Halayudha)

12 C.E :Nachirajiya (Naciraja)

13 C.E : Akaradi Vaidya Nighantu+Indra Dipike+Madanari (Amrutanandi)

14 C.E: Karnataka Shbda Sara (Anonymus) , Karnataka Nighantu (Anonymus), Abhinavabhidana (Abhinava Mangaraja)

15 C.E : Chaturasya Nighantu(Bommarasa) , Dhanvantariya Nighantu (Anonymus)

16 C.E : Kabbigara Kaipidi (Linga Mantri) , Shabda Ratnakara (Anonumus) , Nanartha Kanda (Chenna Kavi) , Nanartha Ratnakara+Ekakshara Nighantu (Devottama) , Karnataka Shabda Manjari (Totadarya) , Bharata Nighantu (Anonymus) , Amarakosha Dipike (Vitthala)

17 C.E : Karnataka Sanjivini +Kavi Kanthahara (Shrungara Kavi) , Karnataka Nighantu (Surya kavi)

TELUGU :

14-18 C.E : Venkateshandhramu (Ganavarapu Venkatakavi) , Akaradi Deshiyandhra Nighantu ( Anonymus), Andhra Prayoga Ratnakaram (Anonymus) , Sarva Lakshana Shiromani (Anonymus) ,Padya Rupa Amara Kosham ( Venkata Rayudu), Andhra Nama Sangraham (Lakshmana Kavi) , Andhra Nama Vishesham (Sura Kavi) Samba Nighantuvu (Kasturi Ranga) , Andhra Bhasharnavam ( Venkata Narayanudu) , Akshara Malika Nighantu (Parvatishvara Shastry) , Andhra Pada Nidanam (Tumu Ramadasa) , Sarnadhra Sara sangraham (Amrutapuram Sanyasi),Nanartha Nighantu (Jayarama Rayulu)

TABLE 2 : GRAMMERS

PRĀKṛIT :

5-7 C.E : Prakruta Prakasha (Vararuchi) , Prakruta Lakshana (Chanda) , Prakruta Kamadhenu (Anonymus)

12 C.E : Prakrutanushasana (Purushottama) , Siddha Hema Shabdanushasana (Hemachandra)

14 C.E : Prkruta Shabdanushasdana (Trivikrama) , Shdbhasha Chandrika (Lakshmidhara)

17 C.E : Prakruta Sarvasva (Markandeya)

SANSKRIT

4-2 B.C.E : Ashtadhyayi (Panini) , Mahabhashya-Commentary on Ashtadhyayi (Patanjali)

2 C.E : Katantra Vyakarana (Shrvavarman)

6 C.E : Mahabhashya Dipika-Commentary on Mahabhashya (Bhatruhari ), Kashika Vrutti- Commentary on Ashtadhyayi (Vamana)

7 C.E : Ashtadhyayi-Commentary (Jayaditya)

8 C.E : Kashika Vivarana Pancika –Commentary on Kashika Vrutti (Jinendra Buddivada)

9 C.E : Pada Manjari – Commentary on Kashika Vrutti (Haradatta)

11 C.E : Pradipa ( Kaiyata) , Bhasha Vrutti -Commentary on Ashtadhyayi (Purushottama Deva)

13 C.E ; Rupavatara (Dharma Keerti)

14 C.E : Mitakshara- Commentary on Ashtadhyayi (AnnaM Bhatta) , Rupamala (Vimala Sarsvati)

15 C.E : Prakriya Kaumudi (Ramachandra Shesha)

16 C.E : Shabda kaustubha (Bhattoji Dikshita) , Prakriya Sarvasva (Nayarana Bhatta)

17 C.E : Pradipodyota (Nagesha Bhatta)

TAMIL :

-3 to 10 C.E : Tolkappiam (Tolkappiyanar)

11 C.E : Viracholiyam (Buddha Mitra)

12 C.E : Neminatham (Gunaveera pandita) , Tolkappiam- Poruladigaram Commentary (Perashiyar)

13 C.E : Nannul (Bhavanadi) , Tolkappiam- Solladigaram Commentary (Senavaraiyar)

14 C.E : Tolkappiam-Commentary (Naccinarkkiniyar)

16 C.E : Tolkappiam- Solladigaram Commentary (Teyvacilaiyar , Kalladanar)

17 C.E : Tolkappiam- Solladigaram Commentary (Anonymus)

KANNADA

11 C.E : Kavyavalokana (Nagavarma)

13 C.E : Shabdamani Darpana ( Keshiraja) , Shabdanushasanam (Akalanka Deva)

17 C.E : Shabdamani Darpana-Commentary (Nitturu Nanjayya)

17 C.E : Shabdamani Darpana-Commentary (Anonymus)

TELUGU :

13 C.E : Andhra Bhasha Bhushanam (Mulaghatika Ketana)

14 C.E : Kavyalankara Chidamani (Vinnakota Peddana)

Part-6:

TABLE 3 : POETICS/PROSODY/RHETORIC

SANSKRIT :

5 C.E : Bruhatsamhita (Varahamihira)

6 C.E : Kavyalankara (Bamaha) , Kavyadarsha (Dandin)

9 C.E : Kavyalankara Sara Sangraha (Uddata) , Kavyalankara Sutravrutti (Vamana) , Kavyalankara (Rudrata), Dhvanyaloka (Anandavarhana)

10 C.E : Cahmdraloka (Jayadeva)

11 C.E : Chandonushasana (Jayakirti), Kavyamimamse (Rajashekhara) , Abhidaavrutti Maatruke (Mukula Bhatta) , Kavyakautuka (Bhatta Tauta) , Hrudaya Drapana (Bhatta Nayaka)

12 C.E :Vrutta Ratnakara (Kedara Bhatta) ,Kavya Praklasha (mummata)

15 C.E : Chando Manjari (ganga Raja)

TAMIL :

-3 to 10 C.E : Tolkappiam (Tolkappiyanar)

10 C.E : Yappurungulam + Yappurungulakkarikai (Amruta Saagara)

11 C.E : Chulamani (Gunasagarar) , Purapporul Vembamalai (Iyanaar Idanaar), Dandiyalankaram(Annonymus)

12 C.E : Ilakkana Vilakkam (Jivanana Munivar)

13 C.E : Veyyappadial (Gunaveera Panditar)

17 C.E : Chidambaram Seyyuttakkovai (Kumara Kruparar)

18 C.E : Ilakkana Vilakkam (Vaidyanathan Alvar)

KANNADA

9 C.E : Kaviraja Marga (Sri Vijaya)

10 C.E : Chandobudhi (Nagavarma-1)

11 C.E : Kavyavalokana (Nagavarma-2)

12 C.E : Udayadityalankaram (Udayaditya) , Shrungara Ratnakara (Kavi Kama)

15-16 C.E : Madhavalankara (Madhava), Kavi jihva Bandhana (Eshwara Kavi) , Kavya Sara (Abhinava Vadi Vidyananda) , Rasa Ratnakara+Apratima Veera Charite (Tirumalarya)

17 C.E : Navarasalankara (Timma) , Kuvalayananda( Jayendra)

TELUGU :

13 C.E : Kavi Vagbhadanamu (Tikkana)

14 C.E : Pratapa Rudriya (Vaidyanatha) , Kavi Janaashrayamu (Rachanna ) , Kavyalankara Chudamani ( Vinnakota Peddana) , Shrungara Dipika (Srinatha)

Part-7 :

TABLE 4 : ENCYCLOPEDIAS

SANSKRIT :

5 C.E : Bruhatsamhita (Varahamihira)

12 C.E : Abhilashitartha Chintamani ( Bhulokamalla)

TAMIL :

10 C.E : Sendan Divakaram (Divakaram) , Pingalantai (Pingalar)

12 C.E : Chudamani Nigantu (Mangala Puttiran)

KANNADA :

10-11 C.E : Lokopakara (Chavundaraya)

15 C.E : Viveka Chintamani (Nijaguna Shivayogi) , Siribhuvalaya (Kumudendu), Shivatatva Chintamani (Lakkana Dandesha)

16 C.E :Sakala Vaidya Samhita Sararnva ( Veeraraja)

TELUGU :

20 C.E :Andhra Vignana Sarvasvam ( K.V.L. Pantulu)

Part-8:

TABLE 5 : MEDICINE/VETERINARY SCIENCE/EROTICS

SANSKRIT :

-2 TO 0 C.E : Sushruta Samhite (Sushruta) , Gajayurveda (Palakapya) , Ashvashastra (Shalihotra), Vaidyaka Sarvasva ashva Chikitse(Nakula)

0 TO 2 C.E : Charaka Samhita (Charaka) , Kumara Tantra (Ravana) , Prayoga Ratnakara (Garga), Bruhaspatimata (Bruhaspati), Kamasutra (Vatsayana)

4 C.E :Ashtanga Hrudaya + Ashtanga Sangraha (Vagbhata) , Ashvayurveda Saara Sindhu (MallaDeva) ,

5-7 C.E :Matanga Leela , Shalihotra , Ashva Vaidyaka

7 to 10 C.E : Madhava Nidanam +Rugna Nischaya (Madhavakara) , Charaka samhite-Commentary (Jayadatta Suri) , Rati Rahasya (kokkoka)

11 to 13 C.E : Nibandha sangraha (Dallana) , Shabda Pradipa (Sureshvara) , Raja Nighantu+Dhanvantari Nighantu (Narahari) , Sarottama Nighantu (Anonymus) , Bhanumati (Chakradatta) , Jayamangala (Yashodhara) , Nagara sarvasva (Padmashri)

14 to 15 C.E : Madana Vinoda Nighantu (Madanapala), Sarangadhara Samhite (Sarangadhara) , RatiManjari (JayaDeva)

16 to 17 C.E : Anna Pana Vidhi (Susena) , Pathyapathya Nighantu + Bhojana Kutuhala ( Raghunatha) , Anangaranga (Kalyana Malla) , Kandarpa Chudamani (Veerabhadra Deva)

TAMIL :

13 to 18 C.E : Vaidya Shataka Nadi + Chikitsa Sara Sangraha ( Teraiyar) , Amudakalai Jnanam+Muppu+Muppuvaippu+Muppuchunnam+Charakku+GuruseyNeer+PacchaiVettu chuttiram (Agastya) , Kadai Kandam +Valalai ChuttiraM +Nadukandam (Konganavar) , Karagappa +Muppu Chuttiram +Dravakam (Nandikeshvara) , Karpam +Valai Chuttiram (Bogara)

KANNADA :

11-12 C.E : Karnata Kalyana Karaka (Jagaddala Somanatha) , Balagraha Chikitse (Devendra Muni) , Govaodya (Kirti Varma) , Madana Tilaka (Chandra Raja) , Anubhava Mukura (Janna)

14 C.E : Khagendra Mani Darpana (Mangaraja) , Ashvashastra (Abhinava Chandra)

15 C.E : Vaidyanruta (Sridhara Deva) , Vaidya Sangatya (Salva) , Ashva Vaidya (Bacarasa), Janavashya (Kallarasa)

16 C.E : Vaidya Sara Sangraha (Channaraja) , Hastayurveda-Commentary (Veerabhadraraja ) , Ashva Vaidya (Bacarasa), Janavashya (Kallarasa)

17 C.E : Vaidya Sara Sangraha (Nanjanatha Bhupala) , Vaidya Samhita Sararnava (Veeraraja ) , Shalihotra Samhita (Ramachandra), Hayasara Samuccaya (Padmana Pandita), Vaidyakanda (Brahma), Strivaidya (Timmaraja)

TELUGU :

15 C.E : Haya Lakshana Sara (manumanchi Bhatta)

TABLE 9 : ASTRONOMY/MATHEMATICS/ASTROLOGY

SANSKRIT :

3-2 B. C.E : Surya Prajnapti , Stananga Sutra , Anuyogadvara Sutra , Shatkhandagama

2-0 B. C.E : Vedanga Jyotishya (Lagada) , Bhadrabahu samhita +Surya Prajnapti-Commentary (Bhadrabahu) , Tiloyapanatti (Yatishvaracharya), Tatvarthayagama shastra (Umasvamin)

5-6 C.E : Arya Bhatiya (Arya Bhata) , Pancvha siddantika + Bruhajjataka+Laghu Jataka + Bruhatsamhita (Varahamihira) , Dashagitika Sara (Anonymus) , Aryastashata (Anonymus)

6-7 C.E : Brahma sputa Siddhanta+Kanadakadhyaya(Brahma Gupta) , Maha Bhaskariyam + Karana Kutuhala (Bhaskara-1) , Rajamruganka (Bhoja)

8 C.E : Shishayabhuvruddhi (Lallacharya) , Ganita Sara sangaraha (Mahaveeracharya) , Horasatpanchashika(Pruthuyana)

11-12 C.E : Siddhanta Shekhara (Sripati) , Siddhanta Shiromani (Bhaskara-2)

14 C.E : Yantraraja (Mahendra Suri)

15 C.E : Tantra sangraha (Neelakantha somayaji)

16 C.E : Sputa Nirnaya (Achyuta)

TAMIL :

16-18 C.E : Ganakkadigaram , Ganita Nul , Asthana Golakam , Ganita Venba , Ganita Divakaram, Ponnilakkam

KANNADA :

11 C.E : Jataka Tilaka (Sridharacharya) ,

12 C.E : Vyavahara Ganita+Kshetra Ganita+Chitra Hasuge +Jaina Ganita Sutra Tikodaaharana +Lilavati (Rajaditya)

15 C.E : Kannada Lilavati (Bala Vaidyada Cheluva)

17 C.E : Ksetra Ganita (Timmarasa) , Behara Ganita (Bhaskara)

TELUGU :

11 C.E : Ganita sara Sangrahamu (Pavaluri Mallana)

The direction of 'borrowings' from one language to another is a secondary component of the philological excursus; there is no universal linguistic rule to firmly aver such a direction of borrowing. Certainly, more work is called for in delineating the structure and forms of meluhha (mleccha) language beyond a mere list of metalware glosses.

![[ image: Work at Harappa is likely to fuel the debate on early writing]](http://news.bbc.co.uk/olmedia/330000/images/_334517_work150.jpg)

![[ image: Harappa was occupied until about 1900 BC]](http://news.bbc.co.uk/olmedia/330000/images/_334517_site150.jpg)

Decipherment in Meluhha rebus cipher: kolmo'three' rebus:kolimi'smithy, forge' PLUS tagaraka'tabernae montana' rebus: tagara'tin (casiterite ore)'.

Decipherment in Meluhha rebus cipher: kolmo'three' rebus:kolimi'smithy, forge' PLUS tagaraka'tabernae montana' rebus: tagara'tin (casiterite ore)'.

The pair of 'ovals or ellipses' are infixed with 'notches'. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implement'.

The pair of 'ovals or ellipses' are infixed with 'notches'. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implement'.

A pair of eagles ligatured with feline paws. Persepolis.

A pair of eagles ligatured with feline paws. Persepolis.

Crucible steel button.

Crucible steel button.  M428 Mohenjo-daro. Sun's rays, hieroglyph on seal. arka 'sun, sun's rays' rebus: arka 'copper, gold', eraka 'molten cast'. Synonym of arka: kundaṇ

M428 Mohenjo-daro. Sun's rays, hieroglyph on seal. arka 'sun, sun's rays' rebus: arka 'copper, gold', eraka 'molten cast'. Synonym of arka: kundaṇ

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Daimabad Seal 1 (Sign 342: Two hieroglyph components: jar with short-neck and rim-of-jar) -- distringuished from broad-mouthed rimless pot which is another Sign hieroglyph.

Sunga 185-75 BCE karabha'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

Sunga 185-75 BCE karabha'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

Kausambi 200 BCE

Kausambi 200 BCE kola 'tiger' rebus: kol'blacksmith' karabha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

kola 'tiger' rebus: kol'blacksmith' karabha 'trunk of elephant' ibha 'elephant' rebus:

Taxila. Pushkalavati 185-160 BCE Karshapana

Taxila. Pushkalavati 185-160 BCE Karshapana Kalinga. Copper punch-marked 3rd cent. BCEarka 'sun' rebus: arka 'copper gold'

Kalinga. Copper punch-marked 3rd cent. BCEarka 'sun' rebus: arka 'copper gold'

Silver punch-marked

Silver punch-marked Asmaka

Asmaka Vidarbha janapada

Vidarbha janapada

m1406 Seal using

m1406 Seal using

Ancient Polynesian catamaran (developed as early as 1500 BCE)

Ancient Polynesian catamaran (developed as early as 1500 BCE)

un système de tenons ressemblant à des languettes de bois prenant place dans des mortaises. Les tenons mesurent 7 cm de largeur, 2 cm d’épaisseur et la profondeur des mortaises peut atteindre 15 cm.

un système de tenons ressemblant à des languettes de bois prenant place dans des mortaises. Les tenons mesurent 7 cm de largeur, 2 cm d’épaisseur et la profondeur des mortaises peut atteindre 15 cm.

How was our language written ~1900-1200 years ago: vikR^iti-s of da from the spitzer manuscript

How was our language written ~1900-1200 years ago: vikR^iti-s of da from the spitzer manuscript

Further, what does the sentence that all the extant Hindu sects follow the basic Vedic principles mean ?There is nothing in the Vedic rituals which allows for the exclusion of women of any age.

I have already commented on the contradictory nature of assuming a celibate deity who cannot tolerate the presence of women in a certain age group and will not repeat it here (See my comments at the end of Sandhyaji's article on the Sabarimala question).It seems that a certain group of people took it upon themselves to set up a code and claim that it originated from Ayyappa himself.

1 Hour ago