Decipherment of Indus Script poses a challenge to historians and students of civilization studies to document the economic history along an Ancient Maritime Tin Route which predated Silk Road by two millennia, creating Arthaśāstra, study of the wealth of a nation. The Tin Route spans -- along the Indian Ocean Rim and Himalayan and Ancient Near Eastern navigable, riverine waterways -- a maritime regime ranging from Hanoi (Vietnam) to Haifa (Israel).

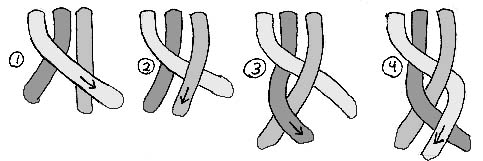

Indus Script Scribes are 4th millennium BCE कारणिका arbiters of metalwork wealth-accounting system symbolised by hieroglyph tagaraka tabernaemontana leguminous shrub. This tagaraka hieroglyph is documented on a potsherd dated to ca.3300 BCE at Harappa, signifying the world's early writing system for a wealth-acounting system for a hypertext read rebus: tagara kolami 'tin smithy, forge'. The signifier of a smithy is a hieroglyph composed of three long linear strokes. ![]()

Sign 102 which reads: kolom 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. Thus, smithy, forge is identified as a cluster subset. This cluster subset hieroglyph of Sign 102 'three' explains why

tabernae montana hieroglyph is repeated thrice on the porsherd. The larger sets of wealth-creating metalwork are signified by over 100 field symbols which accompany such ciphertexts of accounting category clusters.

These larger sets of over 100 field symbols documented on Indus Script are presented in a separate addendum monograph supported by

1. over 1150 monographs at https://independent.academia.edu/SriniKalyanaraman and

2. over 8000 semantic clusters of

Bhāratīya sprachbund (speech union) in

Indian Lexicon of over 25+ ancient languages.

3. over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions presented in 3 volumes of Epigraphia Indus Script, Hypertexts and Meanings (2017)

![]()

![]()

The thesis of this monograph is that Indus Script Scribes are कारणिका teachers, arbiters of metalwork wealth-accounting system. This is demonstrated in the context of the सांगड sāṅgaḍa system of cataloguing which is a 4th millennium BCE innovation of a wealth-accounting ledger entry system to document economic and mercantile transactions.

The underlying sign design principle सांगड sāṅgaḍa 'joined parts' is HTTP hypertext transfer protocol. A hypertext on an Indus Script inscription is composed of hieroglyphs joined together which are classified as both composite 'signs' and composite 'field symbols', for e.g.,: 1. on field symbols with composite animals such as ![]()

hieroglyphs of

a bovine body with bos indicus (zebu horns), ram (hoofs), cobrahood (tail), elephant trunk, human face, scarfs on neck,; and 2. on texts with hypertexts wich are composite hieroglyphs such as ![]() a water-carrier hieroglyph superscripted by a rim-of-jar hieroglyph.

a water-carrier hieroglyph superscripted by a rim-of-jar hieroglyph.

It is indeed surprising that this design principle of Indus Script of the 4th millennium BCE is the underlying principle of the modern-day internet of things, cryptographic and computing systems with transmissions of overlaid texts, images, voice/video.

This HTTP thesis is elaborated in falsifiable clusters of:

1. semantics of the expression कारणिक a. (-का or -की f.) a teacher MBh. ii , 167. कच्चित्कारणिका धर्मे सर्वशास्त्रेषु कोविदाः Mb.2.5.34.; mfn. (g. काश्य्-ादि) " investigating , ascertaining the cause " , a judge (Pañcatantra)(Monier-Williams); Causal, causativ (Apte)

2. clusters of accounting classifiers of metalwork wealth categories created by śreṇi, guilds of artisans/seafaring-merchants

Introduction of a unique mercantile transaction system of jangaḍa, 'approval basis invoicing' is evidenced by the written ciphertext expressions of 'joined hieroglyphs': sāṅgaḍa m f (संघट्ट S) f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together.(Marathi). For example, Mohenjo-daro Seal m0296 is a सांगड sāṅgaḍa, 'a hypertext orthograph formed of two or more components linked together'. Rebus: sangraha, sangaha 'catalogue, list' Rebus also: sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati). samgraha, samgaha 'catalogue,list, arranger, manager' The earliest documented ledger entry is on a potsherd of Harappa dated in archaeological context by HARP to ca. 3300 BCE.

![]()

Harappa potsherd (discovered by Harvard HARP archeaology team). Accounting ledger entry.

kolom 'three' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge'

tagara '

tabernae montana' rebus:

tagara 'tin'. तमर 'tin' (Monier-Williams). Thus,together the hypertext reds:

tagara kolami'tin smithy, forge'

The orthography of the hieroglyph repeated thrice on the potsherd signified a leguminous herb, āhulyamआहुल्यम् N. of a leguminous shrub (तगर, तरवट &c.)

तगरक Tabernaemontana coronaria and a fragrant powder prepared from , it (

वराह-मिहिर 's बृहत्-संहिता. li)tagara

1 n. ʻ the shrub

Tabernaemontana coronaria and a fragrant powder obtained from it ʼ Kauś.,

°aka<-> VarBr̥S. [Cf.

sthagara -- ,

sthakara -- n. ʻ a partic. fragrant powder ʼ TBr.] Pa.

tagara -- n., Dhp.

takara; Pk.

tagara -- ,

ṭayara -- m. ʻ a kind of tree, a kind of scented wood ʼ; Si.

tuvara,

tōra ʻ a species of Cassia plant. ʼ(CDIAL 5622)tagaravallī f. ʻ Cassia auriculata ʼ Npr. [

tagara -- 1, vallī -- ]Si.

tuvaralā ʻ an incense prepared from a species of Tabernaemontana ʼ. (CDIAL 5624) Rebus;

Ta. takaram tin, white lead, metal sheet, coated with tin.

Ma. takaram tin, tinned iron plate.

Ko. tagarm (

obl. tagart-) tin.

Ka. tagara, tamara, tavara id.

Tu. tamarů, tamara, tavara id.

Te. tagaramu, tamaramu, tavaramu id.

Kuwi (Isr.) ṭagromi tin metal, alloy. / Cf. Skt. tamara- id. (DEDR 3001)

![Related image]()

m0296 See:

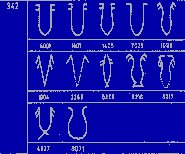

Ten most frequently used signs, (listed in descending order of frequency from left to right).

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account,karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account,karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]() kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá 1 m. ʻmetal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metalʼ PLUS mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' (oval-/rhombus-shaped like a bun-ingot)

kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá 1 m. ʻmetal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metalʼ PLUS mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' (oval-/rhombus-shaped like a bun-ingot)![]() ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.]) ![]() dula

dula 'two' rebus:

dul 'metal casting'

![]() khareḍo 'a currycomb' Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) kharādī' turner, a person who fashions or shapes objects on a lathe ' (Gujarati)

khareḍo 'a currycomb' Rebus: करडा [karaḍā] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) kharādī' turner, a person who fashions or shapes objects on a lathe ' (Gujarati) ![]()

Sign 67

khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin.

Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭamcoinage,

mint.

Ka. kammaṭa id.;

kammaṭi a coiner.

(DEDR 1236) PLUS ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.]). Thus, ayo kammaṭa 'alloy metalmint'.

![]() kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ

kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023).

ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Rebus: khaṇḍa, khāṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans, metal-ware’.

kanda 'fire-altar'

![]() kolmo

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:

kolimi 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

![]() eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arā 'spoke' rebus: āra 'brass'.

eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arā 'spoke' rebus: āra 'brass'. ![]()

![]()

Duplicated Sign 391 (as on Dholavira signboard) is read as:

dula 'pair' rebus:

dul'metal casting' of

eraka 'moltencast copper',

āra 'brass'.

An eleventh sign may be added to the list:

![]()

Sign 123 is comparable to Sign 99 'splinter' hieroglyph.

kuṭi 'a slice, a bit, a small piece'(Santali) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546) PLUS 'notch' hieroglyph: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, khāṇḍā kuṭhi metalware smelter.

![]() Variants of Sign 293 Sign 293 is a ligature of

Variants of Sign 293 Sign 293 is a ligature of![]()

Sign 287 '

curve' hieroglyph and 'angle' hieroglyph (as seen on lozenge/rhombus/ovalshaped hieroglyphs). The basic orthograph of Sign 287 is signifiedby the semantics of: kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) cf. āra-kūṭa, 'brass' Old English ār 'brass, copper, bronze' Old Norse eir 'brass, copper', German ehern 'brassy, bronzen'. kastīra n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. 2. *kastilla -- .1. H. kathīr m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; G. kathīr n. ʻ pewter ʼ.2. H. (Bhoj.?) kathīl, °lā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; M. kathīl n. ʻ tin ʼ, kathlẽ n. ʻ large tin vessel ʼ.(CDIAL 2984) कौटिलिकः kauṭilikḥ कौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith. Sign 293 may be seen as a ligature of Sign 287 PLUS 'corner' signifier: Thus, kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá 1 m. ʻmetal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metalʼ PLUS kuṭila 'curve' rebus: kuṭila 'bronze/pewter' (Pewter is an alloy that is a variant brass alloy). The reading of Sign 293 is:

kanac kuṭila 'pewter'

.

I find a surprisingly comparable Indus Script hieroglyphs.

![]()

This 'sign' is a semantic expansion of the

![]()

Sign 293 'curve +corner' duplicated, i.e.

dula 'duplicated' rebus:

dul 'metal casting' PLUS

kanac kuṭila 'pewter'. May signify pewter casting. Alternative: kaḍī a chain; a hook; a link (G.); kaḍum a bracelet, a ring (G.) Rebus: kaḍiyo [Hem. Des. kaḍaio = Skt. sthapati a mason] a bricklayer; a mason; kaḍiyaṇa, kaḍiyeṇa a woman of the bricklayer caste; a wife of a bricklayer (Gujarati)

![]()

h1028

![]()

h1029

h2049a baṭa 'rimless, wide-mouthed pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' PLUS ḍabu 'an iron spoon' (Santali) Rebus: ḍab, ḍhimba, ḍhompo 'lump (ingot?). Thus, together, furnace ingots

The following 45 clusters of three consecutive signs (triplets) are examples of joined hieroglyph components to create a composite sign or ciphertext. Such 'joined hieroglyphs' exemplify sāṅgaḍa m f (संघट्ट S) f A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together.(Marathi). Seal m0296 is a

सांगड sāṅgaḍa, 'a hypertext orthograph formed of two or more components linked together'. Rebus: sangraha, sangaha 'catalogue, list' Rebus also: sanghāḍiyo, a worker on a lathe (Gujarati).

Cluster1

![]()

Sign 293

kanac kuṭila 'pewter';

kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace', 'factory';

Sign 123 kuṭi 'a slice, a bit, a small piece'(Santali) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546) PLUS 'notch' hieroglyph: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, kuṭhi khāṇḍā smelter metalware.

Sign 343 kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman' PLUS खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, khāṇḍā karṇī 'metalware supercargo'.

The inscription message:Pewter factory, smelter metalware,metalware supercargo.

![]()

Sign 178 is a ligature of 'three short strokes' and 'crook' hieroglyph shown infixed with a circumscript of duplicated four short strokes as in Sign 179

![]()

![]() Sign 178 is: kolmo ‘three’ (Mu.); rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Telugu.) मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) Together: kolami meḍ 'iron smithy'.

Sign 178 is: kolmo ‘three’ (Mu.); rebus: kolami ‘smithy’ (Telugu.) मेंढा [ mēṇḍhā ] A crook or curved end (of a stick, horn &c.) and attrib. such a stick, horn, bullock. मेढा [ mēḍhā ] m A stake, esp. as forked. meḍ(h), meḍhī f., meḍhā m. ʻ post, forked stake ʼ.(Marathi)(CDIAL 10317) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.) Together: kolami meḍ 'iron smithy'.![]()

Sign 389 is a composite hypertext composed of

![]()

Sign 169 infixed in 'oval/lozenge/rhombus' hieoglyph

![]()

Sign 373.

Sign 373 has the shape of oval or lozenge is the shape of a bun ingot. mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced atone time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed likea four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes andformed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt komūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali). Thus, Sign 373 signifies word, mũhã̄ 'bun ingot'.

Sign 169 may be a variant of ![]() Sign 162. Sign kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:kolami 'smithy, forge'. Thus, the composite hypertext of Sign 389 reads: mũhã̄ kolami 'ingot smithy/forge'.

Sign 162. Sign kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:kolami 'smithy, forge'. Thus, the composite hypertext of Sign 389 reads: mũhã̄ kolami 'ingot smithy/forge'.

Cluster 2

![]()

![]() Sign 12 is kuṭi 'water-carrier' (Telugu) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546)

Sign 12 is kuṭi 'water-carrier' (Telugu) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546)![]()

Sign 178 reads:

kolami meḍ 'iron smithy'

![]() Sign 389 reads: mũhã̄ kolami 'ingot smithy/forge'.

Sign 389 reads: mũhã̄ kolami 'ingot smithy/forge'.

![]() Sign 15 reads:

Sign 15 reads: ![]() Sign 12 kuṭi 'water-carrier' (Telugu) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546) PLUS

Sign 12 kuṭi 'water-carrier' (Telugu) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546) PLUS ![]() Sign 342 kanda kanka

Sign 342 kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus:

kanda kanka 'fire-trench account,

karṇika 'scribe, account'

karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.

Thus, the composite hypertext of Sign 15 reads: kuṭhi karṇika 'smelter helmsman/scribe/supercargo'.

Cluster 3

kuṭhi khāṇḍā smelter metalware.

kolami 'smithy/forge' (for)

khaṇḍa kuṭhi 'implements, (from) smelter'.

||| PLUS

![]()

Sign 190

Ciphertext 190: Sprouts (in watery field), twigs: kūdī ‘bunch of twigs’ (Sanskrit) rebus:

kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) PLUS

gaṇḍa 'four' rebus:

kaṇḍa 'fire-altar'

khaṇḍa 'implements, metalware'.

||| Number three reads:

kolom 'three' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge'. Thus,the hypertext of Sign 190 PLUS numeral three reads:

kolami khaṇḍa kuṭhi 'smithy/forge (for) implements, (from) smelter'

![]()

Variants of Sign 190

![]()

h0048 Text of inscription:

kolami khaṇḍa kuṭhi 'smithy/forge (for) implements, (from) smelter'

![]() Shortugai, Bactria (Jarrige, 1984) Text of inscription: kolami khaṇḍa kuṭhi 'smithy/forge (for) implements, (from) smelter'. The same expression is a field-ssymbol on B12 set of Mohenjo-daro copper plates (One example out of 205 copper plates;on the reverse tiger PLUS text). kola 'tiger' rebus:kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron' kolle 'blacksmith'.

Shortugai, Bactria (Jarrige, 1984) Text of inscription: kolami khaṇḍa kuṭhi 'smithy/forge (for) implements, (from) smelter'. The same expression is a field-ssymbol on B12 set of Mohenjo-daro copper plates (One example out of 205 copper plates;on the reverse tiger PLUS text). kola 'tiger' rebus:kolhe 'smelter' kol 'working in iron' kolle 'blacksmith'.![]() B12 set of an example from 205 Mohenjo-daro copper plates

B12 set of an example from 205 Mohenjo-daro copper plates

![]()

Sign 123

kuṭhi khāṇḍā smelter metalware.![]() Sign 102 kolomo 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'

Sign 102 kolomo 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'

Togetherwith Sign102 and Sign 190, the pair of hieroglyphs reads:

kolami khaṇḍa kuṭhi 'smithy/forge (for) implements, (with) smelter'.

Thus, Sign 123 which occurs in hypertext Cluster 3 is a semantic determinative: that, the products documented and accounted for in samgara, 'catalogue' relate to smithy/forge implements (from) smelter'.

Cluster 4

![]() kanac kuṭila kuṭhi khāṇḍā kolami, 'bell-netal, pewter smelter metalware (for/from) smithy/forge'.

kanac kuṭila kuṭhi khāṇḍā kolami, 'bell-netal, pewter smelter metalware (for/from) smithy/forge'.

![]()

![]()

Sign pair of Signs 123, 293 is instructive on the semantics of the hypertext 'slice' PLUS 'notch' hieroglyphs signified by Sign 123 The hypertext reads:

kanac kuṭila kuṭhi khāṇḍā 'bell-metal, pewter smelter metalware.'

Sign 293

kanac kuṭila 'pewter'

.

Sign 123 kuṭi 'a slice, a bit, a small piece'(Santali) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546) PLUS 'notch' hieroglyph: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, kuṭhi khāṇḍā smelter metalware.

![]() Sign 102 kolomo 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Sign 102 kolomo 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Thus, the hypertext of the triplet of Cluster 4 reads: kanac kuṭila kuṭhi khāṇḍā kolami, 'smelter metalware (for/from) smithy/forge'.

Cluster 5

![]()

The hypertext reads:

ranku kuṭhi kanda kanka 'tin smelter, fire-trench account,

karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',

कर्णिक helmsman

. PLUS

kūdī ‘bunch of twigs’ (Sanskrit) rebus:

kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali) or

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

ranku 'liquid measure' (Santal8i) Rebus: ranku 'tin' (Santali) rango 'pewter'. ranga, rang pewter is an alloy of tin, lead, and antimony (anjana) (Santali).

raṅga

3 n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. [Cf.

nāga -- 2, vaṅga --

1] Pk.

raṁga -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; P.

rã̄g f.,

rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ (← H.); Ku.

rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼ, gng.

rã̄k; N.

rāṅ,

rāṅo ʻ tin, solder ʼ, A. B.

rāṅ; Or.

rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ,

rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth.

rã̄gā, OAw.

rāṁga; H.

rã̄g f.,

rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; Si.

ran̆ga ʻ tin ʼ.(CDIAL 10562) B.

rāṅ(

g)

tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.(CDIAL 10567)

![]()

Sign 169 may be a variant of

![]()

Sign 162.

Sign kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. If interpreted as a sprout, the reading is: Sprouts (in watery field), twigs: kūdī ‘bunch of twigs’ (Sanskrit) rebus:

kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali)

![]() Sign 342kanda kanka

Sign 342kanda kanka 'rim of jar'

कार्णिक 'relating to the ear'

rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account,

karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',

कर्णिक helmsman.

Cluster 6

![]()

Hypertext reads:

mē̃ḍ koḍ dul kāṇḍā 'cast iron workshop';

'metalcast equipment'.

![]() Variants of Sign 245 Hieroglyph: khaṇḍa'divisions' Rebus: kāṇḍā 'metalware' Duplicated Sign 245: dula 'duplicated' rebus: dul 'metal casting'.

Variants of Sign 245 Hieroglyph: khaṇḍa'divisions' Rebus: kāṇḍā 'metalware' Duplicated Sign 245: dula 'duplicated' rebus: dul 'metal casting'.Sign 25 ciphertext is composed of ![]() Sign 1 and

Sign 1 and ![]() Sign 86. mē̃ḍ

Sign 86. mē̃ḍ 'body' rebus:

mē̃ḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.)

Hypertext reads in a constructed Meluhha expression: mē̃ḍ koḍ 'iron workshop'.

Cluster 7

![]()

This is Ciphertext comparable to Cluster 6 (without duplication of 'divisions' hieroglyph) PLUS 'notch' hierogglyph:.

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, the hypertext reads: mē̃ḍ koḍ kāṇḍā 'cast iron workshop';

'equipment, metalware'.

Cluster 8

![]()

Cluster 8 is a variant of Cluster 7.

mē̃ḍ koḍ kāṇḍā 'cast iron workshop';

'equipment, metalware'.

Cluster 9

![]() kanda kanka

kanda kanka 'rim of jar'

कार्णिक 'relating to the ear'

rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account,

karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī'supercargo',

कर्णिक helmsman. PLUS

kolom 'three' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge'. Thus, the hypertext of Sign 345 reads:

kolami karṇī 'smithy, forge, supercargo'. ![]()

This is ciphertext comparable to Cluster 7 (but replacing 'notch' hieroglyph with hypertext 'rim-of-jar'+ infixed three short linearstrokes). The hypertext reads:

mē̃ḍ koḍ kāṇḍā 'cast iron workshop; PLUS

kolami karṇī 'smithy, forge, supercargo'.

Cluster 10

![]()

Sign 99 is

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

'notch' hierogglyph: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

![]() Sign 245 Hieroglyph: khaṇḍa'divisions' Rebus: kāṇḍā 'metalware'. The hypertext Cluster 10 reads: kāṇḍā sal 'metalware workshop'. Semantic determinative: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Sign 245 Hieroglyph: khaṇḍa'divisions' Rebus: kāṇḍā 'metalware'. The hypertext Cluster 10 reads: kāṇḍā sal 'metalware workshop'. Semantic determinative: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Cluster11

![]()

variants of Sign 336

Hypertext of ![]() Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS

Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h'ingot' (Santali).PLUS![]()

Sign 328

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace' ![]() Sign 102 variant

Sign 102 variant ![]() Sign 89 kolomo 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Sign 89 kolomo 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. ![]() Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ

Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023).

ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Thus ciphertext kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ is rebus hypertext

kāṇḍa 'excellent iron',

khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Hypertext Cluster 11 reads : (Catalogue accounting ledger entries) -- mū̃h bhaṭa kolami kāṇḍa 'ingot furnace, smithy/forge, metalware'.

Cluster 12

![]()

Hypertext of

![]()

Sign 267 is composed of rhombus/oval/bun-ingot shape and signifier of 'corner' hieroglyph. The hypertext reads:

mũhã̄ 'bun ingot' PLUS

kanac 'corner' rebus:

kañcu 'bell-metal'.

Sign 267 is oval=shape variant, rhombus-shape of a bun ingot. Like Sign 373, this sign also signifies mũhã̄ 'bun ingot' PLUS kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá1 m. ʻ metal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ Pat. as in S., but would in Pa. Pk. and most NIA. lggs. collide with kāˊṁsya -- to which L. P. testify and under which the remaining forms for the metal are listed. 2. *kaṁsikā -- .1. Pa. kaṁsa -- m. ʻ bronze dish ʼ; S. kañjho m. ʻ bellmetal ʼ; A. kã̄h ʻ gong ʼ; Or. kãsā ʻ big pot of bell -- metal ʼ; OMarw. kāso (= kã̄ -- ?) m. ʻ bell -- metal tray for food, food ʼ; G. kã̄sā m. pl. ʻ cymbals ʼ; -- perh. Woṭ. kasṓṭ m. ʻ metal pot ʼ Buddruss Woṭ 109.2. Pk. kaṁsiā -- f. ʻ a kind of musical instrument ʼ; A. kã̄hi ʻ bell -- metal dish ʼ; G. kã̄śī f. ʻ bell -- metal cymbal ʼ, kã̄śiyɔ m. ʻ open bellmetal pan ʼ. (CDIAL 2756)

sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'![]() Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ

Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023).

ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Thus ciphertext kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ is rebus hypertext

kāṇḍa 'excellent iron',

khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Hypertext Cluster 12 reads: mũhã̄ kañcu sal khāṇḍā 'bun ingot, bell-metal workshop, tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Cluster 13

sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'

![]() ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.]) ![]() Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ

Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023).

ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Thus ciphertext kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ is rebus hypertext

kāṇḍa 'excellent iron',

khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Hypertext Cluster 13 reads: sal ayas khāṇḍā 'workshop, alloy metal, tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Cluster 14

![]()

Hypertext of

![]()

Sign 267 is composed of rhombus/oval/bun-ingot shape and signifier of 'corner' hieroglyph. The hypertext reads:

mũhã̄ 'bun ingot' PLUS

kanac 'corner' rebus:

kañcu 'bell-metal'.

Sign 267 is oval=shape variant, rhombus-shape of a bun ingot. Like Sign 373, this sign also signifies mũhã̄ 'bun ingot' PLUS kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá1 m. ʻ metal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metal ʼ Pat. as in S., but would in Pa. Pk. and most NIA. lggs. collide with kāˊṁsya -- to which L. P. testify and under which the remaining forms for the metal are listed. 2. *kaṁsikā -- .1. Pa. kaṁsa -- m. ʻ bronze dish ʼ; S. kañjho m. ʻ bellmetal ʼ; A. kã̄h ʻ gong ʼ; Or. kãsā ʻ big pot of bell -- metal ʼ; OMarw. kāso (= kã̄ -- ?) m. ʻ bell -- metal tray for food, food ʼ; G. kã̄sā m. pl. ʻ cymbals ʼ; -- perh. Woṭ. kasṓṭ m. ʻ metal pot ʼ Buddruss Woṭ 109.2. Pk. kaṁsiā -- f. ʻ a kind of musical instrument ʼ; A. kã̄hi ʻ bell -- metal dish ʼ; G. kã̄śī f. ʻ bell -- metal cymbal ʼ, kã̄śiyɔ m. ʻ open bellmetal pan ʼ. (CDIAL 2756)![]() ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.]) ![]() Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ

Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023).

ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Thus ciphertext kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ is rebus hypertext

kāṇḍa 'excellent iron',

khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Hypertext Cluster 15 reads: mũhã̄ 'kañcu 'ayas khāṇḍā 'bun ingot, bell metal, alloy metal, tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Cluster 16

![]() sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'

sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'Hypertext of ![]() Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h 'ingot' (Santali).PLUS

Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h 'ingot' (Santali).PLUS![]()

Sign 328

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace' ![]() Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ

Sign 211 'arrow' hieroglyph: kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ (Skt.) H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers (CDIAL 3024). Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023).

ayaskāṇḍa ‘a quantity of iron, excellent iron’ (Pāṇ.gaṇ) Thus ciphertext kaṇḍa ‘arrow’ is rebus hypertext

kāṇḍa 'excellent iron',

khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Hypertext Cluster 16 reads: sal, mū̃h bhaṭa, khāṇḍā 'workshop, ingot furnace, tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'.

Cluster 17

![]() kanac 'corner' rebus: kañcu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá 1 m. ʻmetal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metalʼ PLUS mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' (oval-/rhombus-shaped like a bun-ingot)

kanac 'corner' rebus: kañcu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá 1 m. ʻmetal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metalʼ PLUS mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' (oval-/rhombus-shaped like a bun-ingot)![]() sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'

sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p= 256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel RV. viii , 72 , 12 S3Br. ix Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p= 256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel RV. viii , 72 , 12 S3Br. ix Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 17 reads: kañcu muhã karṇī 'bell-metal ingot, supercargo, scribe'

Cluster 18

![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]() ayo

ayo 'fish' rebus:

ayas 'alloy metal' ays 'iron' PLUS

khambhaṛā 'fish fin rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin.

Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage,

mint.

Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner (DEDR 1236) Thus,

ayo kammaṭa, 'alloymetal mint'

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p= 256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel RV. viii , 72 , 12 S3Br. ix Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p= 256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel RV. viii , 72 , 12 S3Br. ix Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 18 reads: sal kammaṭa karṇī 'workshop, alloymetal mint, supercargo, scribe'

Cluster 19

![]() eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arā 'spoke' rebus: āra 'brass'.

eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arā 'spoke' rebus: āra 'brass'. ![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 19 reads: eraka āra sal karṇī ''moltencast, copper, brass workshop, supercargo, scribe'

Cluster 20

![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]()

Variants of Sign 347

![]()

Sign 347 is duplicated

![]()

Sign 162:

dula 'duplicated,, pair' rebus:

dul 'metal casting'

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali). The hypertext Sign 347 reads:

dul kolami 'metal casting smithy, forge'

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 20 reads: sal dul kolami karṇī workshop, metal casting smithy, forgesupercargo, scribe'

Cluster 21

![]() Variants of Sign 293 Sign 293 is a ligature of

Variants of Sign 293 Sign 293 is a ligature of![]()

Sign 287 '

curve' hieroglyph and 'angle' hieroglyph (as seen on lozenge/rhombus/ovalshaped hieroglyphs). The basic orthograph of Sign 287 is signifiedby the semantics of: kuṭila ‘bent’ CDIAL 3230 kuṭi— in cmpd. ‘curve’, kuṭika— ‘bent’ MBh. Rebus: kuṭila, katthīl = bronze (8 parts copper and 2 parts tin) cf. āra-kūṭa, 'brass' Old English ār 'brass, copper, bronze' Old Norse eir 'brass, copper', German ehern 'brassy, bronzen'. kastīra n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. 2. *kastilla -- .1. H. kathīr m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; G. kathīr n. ʻ pewter ʼ.2. H. (Bhoj.?) kathīl, °lā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; M. kathīl n. ʻ tin ʼ, kathlẽ n. ʻ large tin vessel ʼ.(CDIAL 2984) कौटिलिकः kauṭilikḥ कौटिलिकः 1 A hunter.-2 A blacksmith. Sign 293 may be seen as a ligature of Sign 287 PLUS 'corner' signifier: Thus, kanac 'corner' rebus: kañcu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá 1 m. ʻmetal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metalʼ PLUS kuṭila 'curve' rebus: kuṭila 'bronze/pewter' (Pewter is an alloy that is a variant brass alloy). The reading of Sign 293 is:

kanac kuṭila 'pewter'

.![]()

Sign 123 is comparable to Sign 99 'splinter' hieroglyph.

kuṭi 'a slice, a bit, a small piece'(Santali) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546) PLUS 'notch' hieroglyph: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, khāṇḍā kuṭhi metalware smelter.![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 21 reads: kuṭila kañcu khāṇḍā kuṭhi karṇī 'pewter, bell-metal metalware, smelter, scribe, supercargo;.

Cluster 22

![]() Sign 65 is a hypertext composed of

Sign 65 is a hypertext composed of![]() Sign 59 and 'lid of pot' hieroglyph.

Sign 59 and 'lid of pot' hieroglyph.![]() Sign 134 ayo 'fish' rebus: ayas 'alloy metal' ays 'iron' PLUS

Sign 134 ayo 'fish' rebus: ayas 'alloy metal' ays 'iron' PLUS ![]() dhakka 'lid of pot' rebus: dhakka 'bright' Thus, ayo dhakka, 'bright alloy metal.' Thus, Sign 65 hypertext reads: ayo dhakka 'bright alloy metal'

dhakka 'lid of pot' rebus: dhakka 'bright' Thus, ayo dhakka, 'bright alloy metal.' Thus, Sign 65 hypertext reads: ayo dhakka 'bright alloy metal'![]() ayo

ayo 'fish' rebus:

ayas 'alloy metal' ays 'iron' PLUS

khambhaṛā 'fish fin rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin.

Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage,

mint.

Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner (DEDR 1236) Thus,

ayo kammaṭa, 'alloymetal mint'

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Clust 22 reads: ayo dhakka ayo kammaṭa karṇī , 'bright alloy metal alloymetal mint, scribe, supercargo.'

Cluster 23

![]()

Sign 160 is a variant of

Sign 137![]() Variants of Sign 137 dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu 'mineral' (Santali)

Variants of Sign 137 dāṭu 'cross' rebus: dhatu 'mineral' (Santali)![]()

Sign 123 is comparable to Sign 99 'splinter' hieroglyph.

kuṭi 'a slice, a bit, a small piece'(Santali) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546) PLUS 'notch' hieroglyph: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware'. Thus, khāṇḍā kuṭhi metalware smelter.![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 23 reads: khāṇḍā kuṭhi dhatu karṇī 'metalware smelter, mineral, scribe, supercargo'

Cluster 24

Hypertext of ![]() Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h 'ingot' (Santali).PLUS

Sign 336 has hieroglyph components: muka 'ladle' (Tamil)(DEDR 4887) Rebus: mū̃h 'ingot' (Santali).PLUS![]()

Sign 328

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: baṭa 'iron' bhaṭa 'furnace'. The hypertext reads: mū̃h bhaṭa 'ingot furnace' ![]() Sign 102 variant

Sign 102 variant ![]() Sign 89 kolomo 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Sign 89 kolomo 'three' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. ![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 24 reads: mū̃h bhaṭa kolami, karṇī 'ingot furnace, smithy, forge, scribe, supercarggo'

Cluster 25

![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]() käti

käti ʻwarrior' (Sinhalese)(CDIAL 3649). rebus:

khātī m. ʻ 'member of a caste of wheelwrights'ʼVikalpa:

bhaṭa 'warrior' rebus:

bhaṭa 'furnace'.

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 25 reads: sal khäti ʻkarṇī 'workshop, wheelwright, scribe, supercargo'

Cluster 26

![]() Sign 249 ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin' Rebus: rango ‘pewter’. ranga, rang pewter is an alloy of tin, lead, and antimony (anjana) (Santali). Hieroglyhph: buffalo:

Sign 249 ranku 'liquid measure' rebus: ranku 'tin' Rebus: rango ‘pewter’. ranga, rang pewter is an alloy of tin, lead, and antimony (anjana) (Santali). Hieroglyhph: buffalo: Ku. N.

rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ (or <

raṅku -- ?).(CDIAL 10538, 10559) Rebus: raṅga

3 n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. [Cf.

nāga -- 2, vaṅga --

1] Pk.

raṁga -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; P.

rã̄g f.,

rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ (← H.); Ku.

rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼ, gng.

rã̄k; N.

rāṅ,

rāṅo ʻ tin, solder ʼ, A. B.

rāṅ; Or.

rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ,

rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth.

rã̄gā, OAw.

rāṁga; H.

rã̄g f.,

rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; Si.

ran̆ga ʻ tin ʼ.(CDIAL 10562) B.

rāṅ(

g)

tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.(CDIAL 10567)

![]() kolmo

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 26 reads: ranku kolami karṇī 'tin smithy, forge, scribe, supercargo'

Cluster 27

![]() kolmo

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali) PLUS semantic determinative: kolom 'thrice' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Thus, hypertext Cluster 27 reads: kolami 'smithy, forge'.

Cluster 28

![]() eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arā 'spoke' rebus: āra 'brass'.

eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' arā 'spoke' rebus: āra 'brass'. ![]() Sign 99 sal 'splinter rebus: sal 'workshop'

Sign 99 sal 'splinter rebus: sal 'workshop'![]() kolmo

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

Hypertext Cluster 28 reads: eraka āra sal kolami 'moltencast copper,brass workshop, smithy,forge'.

Cluster 29

![]()

Variants of Sign 343

![]()

Sign 343 hypertext is a composite of: 1. rim-of-jar hieroglyph and 2. notch.

'notch' hieroglyph: खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware' PLUS कार्णिक rebus:

karṇī 'supercargo, scribe',कर्णिक helmsman' कारणिका 'accountant'. Thus, the hypertext reads:

khāṇḍā karṇī 'equipment scribe, accountant'

![]() kolmo

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12

S3Br. ix

Ka1tyS3r. &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship

R. कर्णी

f. of °ण

ifc. (

e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°)

Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46"

N. of कंस's mother " , in

comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant essel'.

Hypertext Cluster 29 reads: khāṇḍā karṇī kolami karṇika कर्णिक 'equipment scribe, accountant, smithy/forge, helmsman'.

Cluster 30

![]() Variants of Sign 328

Variants of Sign 328![]() baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'. dula 'duplicated' rebus: dul 'metalcasting'. Thus, hypertext of duplicated Sign328 hieroglyphs is read: dul bhaṭa 'metalcasting furnace'

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'. dula 'duplicated' rebus: dul 'metalcasting'. Thus, hypertext of duplicated Sign328 hieroglyphs is read: dul bhaṭa 'metalcasting furnace'![]()

Sign 12 variants

![]()

Sign 12 hieroglyph

kuṭi 'water-carrier' rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'

Hypertext Cluster 30 reads: kuṭhi dul baṭa bhaṭa 'smelter, iron metalcasting furnace'

Cluster 31

![]()

Variants of Sign 48

![]()

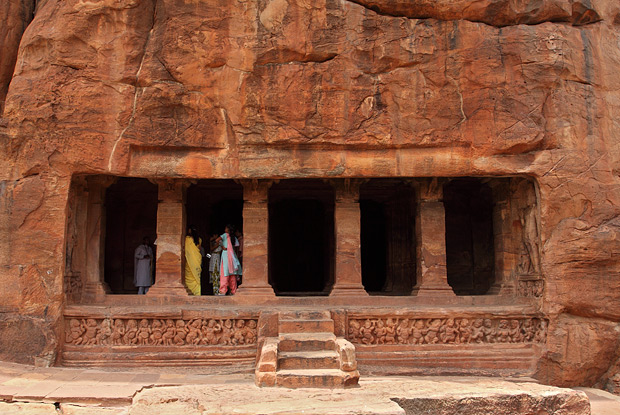

Seal published by Omananda Saraswati. In Pl. 275: Omananda Saraswati 1975. Ancient Seals of Haryana (in Hindi). Rohtak.

![]() This pictorial motif gets normalized in Indus writing system as a hieroglyph sign: baraḍo

This pictorial motif gets normalized in Indus writing system as a hieroglyph sign: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu)

![]()

Sign 48 is a 'backbone, spine' hieroglyph:

baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus:

baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) Tir. mar -- kaṇḍḗ ʻ back (of the body) ʼ; S. kaṇḍo m. ʻ back ʼ, L. kaṇḍ f., kaṇḍā m. ʻ backbone ʼ, awāṇ. kaṇḍ, °ḍī ʻ back ʼH. kã̄ṭā m. ʻ spine ʼ, G. kã̄ṭɔ m., M. kã̄ṭā m.; Pk. kaṁḍa -- m. ʻ backbone ʼ.(CDIAL 2670) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) bharatiyo = a caster of metals; a brazier; bharatar, bharatal, bharataḷ = moulded; an article made in a mould; bharata = casting metals in moulds; bharavum = to fill in; to put in; to pour into (Gujarati) bhart = a mixed metal of copper and lead; bhartīyā = a brazier, worker in metal; bhaṭ, bhrāṣṭra = oven, furnace (Sanskrit. )baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) ![]() baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'.

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'.![]() kolmo

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

Hypertext Cluster 31 reads: bhaṭa bharat kolami 'furnace, mixed alloy (copper, zinc,tin)smithy, forge'. The word bharat may explain the semantics of Bhāratīya, 'people working with bharata metal alloys'. bharatiyo are metalcasters, who -- together with agriculturists, textile workers, sculptors, śilpi, seafaring merchant guilds --śreṇi --, medicinemen -- created the wealth of a nation by the key economic factor of 'corporate form of organization' called śreṇi which contributed to 33% of global GDP in 1 CE (pace Angus Maddison).

Cluster 32

![]()

Sign 386 is a hypertext composed of

![]()

Sign 373 and notch.

खांडा [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon). (Marathi) Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, pots and pans, metal-ware' PLUS mũh, muhã 'ingot' or muhã 'quantity of metal produced at one time in a native smelting furnace.' (oval-/rhombus-shaped like a bun-ingot).The hypertext Sign 386 reads two distinct wealth categories: muhã khāṇḍā 'ingots, equipment, tools, metalware'.

![]() baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'.

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'.![]() kolmo

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus:

kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

Hypertext Cluster 32 reads: muhã khāṇḍā bhaṭa kolami 'ingots, equipment, tools, metalware, iron furnace, smithy, forge'.

Cluster 33

![]()

![]()

Sign 12 is

kuṭi 'water-carrier' (Telugu) Rebus: kuṭhi. 'iron smelter furnace' (Santali) kuṭhī factory (A.)(CDIAL 3546)![]() baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'.

baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'.![]() kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

kolmo 'rice plant' rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge. Vikalpa: pajhaṛ = to sprout from a root (Santali); Rebus: pasra ‘smithy, forge’ (Santali)

Hypertext of Cluster 33 reads: kuṭh bhaṭa kolami ' 'iron smelterfactory, furnace, smithy, forge'.

Cluster 34

![]()

Sign 67

khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin.

Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage,

mint.

Ka. kammaṭa id.;

kammaṭi a coiner.

(DEDR 1236) PLUS ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.]). Thus, ayo kammaṭa 'alloy metalmint'.

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)| &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'. |

![]()

Variants of Sign 176

![]()

Sign 176

khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati).

Hypertext Cluster 34 reads: ayo kammaṭa karṇī karaḍā खरडें 'alloy metal mint, supercargo, scribe, daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. kharādī ' turner'

Cluster 35

![]()

Sign 48 is a 'backbone, spine' hieroglyph:

baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus:

baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) Tir. mar -- kaṇḍḗ ʻ back (of the body) ʼ; S. kaṇḍo m. ʻ back ʼ, L. kaṇḍ f., kaṇḍā m. ʻ backbone ʼ, awāṇ. kaṇḍ, °ḍī ʻ back ʼH. kã̄ṭā m. ʻ spine ʼ, G. kã̄ṭɔ m., M. kã̄ṭā m.; Pk. kaṁḍa -- m. ʻ backbone ʼ.(CDIAL 2670) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) bharatiyo = a caster of metals; a brazier; bharatar, bharatal, bharataḷ = moulded; an article made in a mould; bharata = casting metals in moulds; bharavum = to fill in; to put in; to pour into (Gujarati) bhart = a mixed metal of copper and lead; bhartīyā = a brazier, worker in metal; bhaṭ, bhrāṣṭra = oven, furnace (Sanskrit. )baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

&c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'.

![]() Sign 176 khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati). Sign 176 khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati). |

Cluster 36

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

| &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'. |

![]()

Sign 176

khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati).

Cluster 37

![]()

Sign 65 is a hypertext composed of

![]()

Sign 59 and 'lid of pot' hieroglyph.

![]()

Sign 134

ayo 'fish' rebus:

ayas 'alloy metal' ays 'iron' PLUS

![]() dhakka 'lid of pot' rebus: dhakka 'bright' Thus, ayo dhakka, 'bright alloy metal.

dhakka 'lid of pot' rebus: dhakka 'bright' Thus, ayo dhakka, 'bright alloy metal.' Thus, Sign 65 hypertext reads:

ayo dhakka 'bright alloy metal'

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

| &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'. |

![]()

Sign 176

khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati).

Hypertext Cluster 37 reads: ayo dhakka karṇī karaḍā खरडें 'bright alloy metal, scribe, supecargo, daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati).

Cluster 38

![]()

Sign 193 signifies a structure, perhaps a pair of warehouse. A variant may be seen on Sohgaura copperplate topline of Indus Script hieroglyphs.

dula 'two, pair' rebus:

dul 'metalcasting' PLUS

koṭhāri 'treasurer, warehouse'. Rebus: kuṭhāru 'armourer' Together the hypertext reads: dul kuṭhāru 'metalcasting armourer'![]() Sohgaura copper plate. Bilingual (Indus Script hypertext+ Brāhmi syllabary) inscription describes functions of two warehouses for itinerant merchants.

Sohgaura copper plate. Bilingual (Indus Script hypertext+ Brāhmi syllabary) inscription describes functions of two warehouses for itinerant merchants.

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

| &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'. |

![]()

Sign 176

khareḍo 'a currycomb (Gujarati) Rebus: karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. Rebus: kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati).

Hypertext Cluster 38 reads: dul kuṭhāru karṇī karaḍā खरडें 'metalcasting armourer, scribe, supecargo, daybook, wealth-accounting ledger'. kharādī ' turner' (Gujarati).

Cluster 39

![]()

Sign 87

dula 'two' rebus:

dul 'metalcasting'

![]() ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

&c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'.

Hypertext Cluster 39 reads: dul ayas karṇī 'metalcasting, alloy metal, scribe (engraver), supercargo' |

Cluster 40

![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]()

Sign 87

dula 'two' rebus:

dul 'metalcasting'

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

&c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'.

Hypertext Cluster 40 reads: sal, dul, karṇī 'workshop, metalcasting, scribe (engraver), supercargo' |

Cluster 41

![]()

Variants of Sign 403

![]()

Sign 403 is a duplication of

![]() dula

dula 'pair, duplicated' rebus:

dul 'metalcasting' PLUS Sign'oval/lozenge/rhombus' hieoglyph Sign 373.

Sign 373 has the shape of oval or lozenge is the shape of a bun ingot. mũhã̄ = the quantity of iron produced atone time in a native smelting furnace of the Kolhes; iron produced by the Kolhes and formed likea four-cornered piece a little pointed at each end; mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes andformed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends; kolhe tehen mẽṛhẽt komūhā akata = the Kolhes have to-day produced pig iron (Santali). Thus, Sign 373 signifies word, mũhã̄ 'bun ingot'. Thus, hypertext Sign 403 reads:

dul mũhã̄ 'metalcast ingot'.

![]()

Sign 87

dula 'two' rebus:

dul 'metalcasting'

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

| &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'. |

Hypertext Cluster 41 reads:dul mũhã̄ dul karṇī 'metalcast ingot, metalcasting, scribe (engraver), supercargo'.

Cluster 42

![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]()

Sign 87

dula 'two' rebus:

dul 'metalcasting'

![]() ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])

Hypertext Cluster 42 reads: sal dul aya 'workshop, metalcasting, alloymetal'

Cluster 43

![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]() ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.])

ayo, aya 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' अयस् n. iron , metal RV. &c; an iron weapon (as an axe , &c ) RV. vi , 3 ,5 and 47 , 10; gold (नैघण्टुक , commented on by यास्क); steel L. ; ([cf. Lat. aes , aer-is for as-is ; Goth. ais , Thema aisa ; Old Germ. e7r , iron ; Goth. eisarn ; Mod. Germ. Eisen.]) ![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

&c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'.

Hypertext Cluster 43 reads: sal aya karṇī 'workshop, alloy metal, scribe (engraver), supercargo' |

Cluster 44

![]() sal

sal 'splinter' rebus:

sal 'workshop'

![]() käti

käti ʻwarrior' (Sinhalese)(CDIAL 3649). rebus:

khātī m. ʻ 'member of a caste of wheelwrights'ʼVikalpa:

bhaṭa 'warrior' rebus:

bhaṭa 'furnace'.

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

| &c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'. |

Hypertext Cluster 44 reads: sal bhaṭa karṇī 'workshop, furnace, scribe (engraver), supercargo'

Cluster 45

![]()

Variants of Sign 48

![]()

Seal published by Omananda Saraswati. In Pl. 275: Omananda Saraswati 1975. Ancient Seals of Haryana (in Hindi). Rohtak.

![]() This pictorial motif gets normalized in Indus writing system as a hieroglyph sign: baraḍo

This pictorial motif gets normalized in Indus writing system as a hieroglyph sign: baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu)

![]()

Sign 48 is a 'backbone, spine' hieroglyph:

baraḍo = spine; backbone (Tulu) Rebus:

baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi) Tir. mar -- kaṇḍḗ ʻ back (of the body) ʼ; S. kaṇḍo m. ʻ back ʼ, L. kaṇḍ f., kaṇḍā m. ʻ backbone ʼ, awāṇ. kaṇḍ, °ḍī ʻ back ʼH. kã̄ṭā m. ʻ spine ʼ, G. kã̄ṭɔ m., M. kã̄ṭā m.; Pk. kaṁḍa -- m. ʻ backbone ʼ.(CDIAL 2670) Rebus: kaṇḍ ‘fire-altar’ (Santali) bharatiyo = a caster of metals; a brazier; bharatar, bharatal, bharataḷ = moulded; an article made in a mould; bharata = casting metals in moulds; bharavum = to fill in; to put in; to pour into (Gujarati) bhart = a mixed metal of copper and lead; bhartīyā = a brazier, worker in metal; bhaṭ, bhrāṣṭra = oven, furnace (Sanskrit. )baran, bharat ‘mixed alloys’ (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

![]() kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note:

kanda kanka 'rim of jar' कार्णिक 'relating to the ear' rebus: kanda kanka 'fire-trench account, karṇika 'scribe, account' karṇī 'supercargo',कर्णिक helmsman'.Note: Hieroglyph: कर्ण [p=

256,2] the handle or ear of a vessel

RV. viii , 72 , 12 Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa ix (

कात्यायन-श्रौत-सूत्र)

&c Rebus: कर्ण the helm or rudder of a ship R. कर्णी f. of °ण ifc. (e.g. अयस्-क्° and पयस्-क्°) Pa1n2. 8-3 , 46" N. of कंस's mother " , in comp. Rebus: karṇī, 'Supercargo responsible for cargo of a merchant vessel'

![]() baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'. baṭa 'rimless pot' rebus: bhaṭa 'furnace' baṭa 'iron'.

Hypertext Cluster 45 reads: bharat karṇī bhaṭa 'mixed alloys (5 copper, 4 zinc,1 tin), scribe (engraver), supercargo, iron furnace'.

Background note on how cluster analysis of Indus Script sign hypertexts help identify repeating, freuquently occurring triplets (i.e. three 'signs' in sequence) constituting a semantic cluster

This monograph is in effect an addendum to the cluster analysis of 'signs' presenting the 'sematnic' structure or accounting classifiers of wealth-accounting ledgers.

|

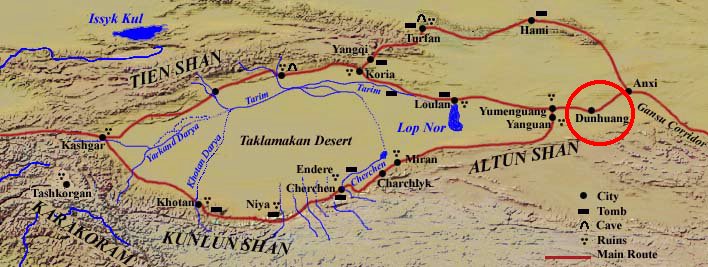

Using partition-based clustering (K-means algorithm) to analyse Indus Script texts, Nisha Yadav et al identify the following dominant (high-frequency occurrence) clusters. The cluster analysis is based on a subset of inscriptions. The number of texts included in a computer corpus called EBUDS is 1548. This is a filtered corpus excluding duplicates and ambiguous texts.EBUDS identifies 377 distinct signs. Strings of sign images are read from right to left. The statistical approach in creating EBUDS is detailed in:

Yadav, N., Vahia, M. N., Mahadevan, I. and Joglekar, H. 2008. A Statistical Approach for Pattern Search in Indus Writing. International Journal of Dravidian Linguistics. vol. XXXVII, pp. 39-52.

These 45 Semantic clusters of metalwork wealth-accounting are valided in a monograph Table 6 which lists 45 triplets of signs, which are of frequent occurrence.

After Table 6 in: Nisha Yadav, Ambuja Salgaonkar and Mayank Vahia. Clustering Indus Texts using K-means. International Journal of Computer Applications 162(1):16-21, March 2017

https://tinyurl.com/y8gr7amt This monograph is an addendum emphasising the significance of this brilliant cluster analysis done by Nisha Yadav, Ambuja Salgaonkar and Mayank Vahia (2017). At the outset, congratulations to Nisha Yadav, Ambuja Salgaonkar, and Mayank Vahia for this lucid, precisely presented, outstanding contribution which validates the decipherment of the Indus Scipt Cipher as a cataloguing, sāṅgāḍī 'joined parts' rebus:

samgraha, samgaha 'catalogue,list, arranger, manager' --

an accounting classification of ledgers for wealth accounting during the Tin-Bronze Revolution, 4th millennium BCE.

Thesis of the monograph: Indus Script Field symbols are accounting ledger classifications of wealth categories, classified as metalwork.

This thesis is validated by a Cluster analysis of 33 sāṅgāḍī 'joined parts' Indus Script Field symbols evidences samgaha wealth categories for accounting ledgers, samgaha 'catalogue, list, arranger, manager'. The cargo listed in samgaha are inscribed -- as Indus Script inscriptions -- for delivery by જંગડિયો jangaḍiyo 'military guard who accompanies treasure into the treasury' (Gujarati) --in mercantile transactions on jangaḍ ,'invoiced on approval basis'. This mercantile process explains the repeated and frequent deployment of sāṅgāḍī 'joined parts' princple of writing system for both 'signs' and 'field symbols'.

Executive Summary

The cluster analysis presented in this monograph identify superstructures of wealth categories to which the ‘triplets of signs’ are substructures. The study suggests that there are 33 distinct structures relatedto wealth categories of metalwork to document work on: 1. Minerals; 2. Smelting; 3. Use of furnaces to create alloys by mixing minerals or infusing carbon element through carburization processes; smithy, forge work; 4. Forging of implements, tools, metalware; 5. Metalcasting, including cire perdue (lost-waxmethods) of metal casting; 6. Organization in guilds of artisans/seafaring merchants.

The following 38 categories of wealth accounting ledgers are identified by cluster analysis

Cluster 1 Eagle in flight cluster, thunderbolt weapon, blacksmith classifier

Cluster 2 Metallurgical invention of aṅgāra carburization, infusion of carbon element to harden molten metal

Cluster 3 Svastika cluster, zinc wealth category

Cluster 4 Ficus clusters, copper wealth category

Cluster 5 Tiger cluster, smelter category

Cluster 6 Spearing a bovine cluster, smelter work

Cluster 7 A metallurgical process narrative in four clusters -- four sides of a tablet:

Cluster 8 Seafaring boat cluster, cargo wealth category

Cluster 9 Bier cluster, wheelwright category

Cluster 10 Sickle cluster, wheelwright category

Cluster 11 Sun's rays cluster, gold wealth category

Cluster 12 Body of standing person cluster, element classifier

Cluster 13 Frog cluster, ingot classifier

Cluster 14 Serpent cluster as anakku, 'tin ore' classifier

Cluster 15 Tortoise, turtle clusters, bronze classifiers

Cluster 16 Seated person in penance, mint classifier

Cluster 17 Archer cluster, mint classifier

Cluster 18 ayakara 'metalsmith' cluster, alloy metal smithy, forge classifier

Cluster 19 Smelter cluster, wealth-category of smelted mineral ores

Cluster 20 Magnetite, ferrite ore cluster wealth-category or wealth-classification

Cluster 21 Dhokra 'cire perdue' metal cassting artisans classifier

Cluster 22 dhāvḍī ʻcomposed of or relating to ironʼ, dhā̆vaḍ 'iron-smelters' cluster, Iron, steel product cluster

Cluster 23 Endless knot cluster, yajña dhanam, iron category, ḍhangar ‘blacksmith’ category

Cluster 24 Dance-step cluster, iron smithy/forge

Cluster 25 Minerals Smelter, metals furnace, clusters

Cluster 26 Armoury clusters

Cluster 27 Double-axe cluster, armourer category

Cluster 28 Seafaring merchant clusters

Cluster 29 Smithy, forge clusters

Cluster 30 Equipment making blacksmithy/forge

Cluster 31 Tin smithy, forge clusters

Cluster 32 Alloy metal clusters

Cluster 33 Metal equipment, product clusters

-- Metalwork samgaha, 'catalogues' cluster सं-ग्रह complete enumeration or collection , sum , amount , totality (एण , " completely " , " entirely ") (याज्ञवल्क्य), catalogue, list

Cluster 34 śreṇi Goldsmith Guild clusters

Cluster 34a Three tigers joined, smithy village,smithy shop category

Cluster 35 पोळ [pōḷa], 'zebu'cluster, magnetite ore category pōḷa, 'magnetite, ferrous-ferric oxide

Cluster 36 Dotted circles, Indus Script Hypertexts dhāv 'red ores'

Cluster 37 Indus Script inscriptions on ivory artifacts signify metalwork wealth accounting

Cluster 38 Diffusion of Metallurgy: Meluhha and western Afghanistan sources of tin

This accounting classification of metalwork wealth categories is consistent with the finding that the writing system with a recognized pattern of clustering pictorial motifs was consistently used over the entire gamut of contact areas of Sarasvati civilization. Decipherment of the hieroglyph components of field symbols yields the semantic structure of underlying Meluhha speech in Bhāratīya sprachbund(Speech union).

The total number of objects on M Corpus with distinct, unambiguous pictorials or field symbols is 1894. It is unfortunate that most decipherment claims ignore an analysis of this dominant portion of the documented evidence of the civilization. Some brush them aside as 'cult symbols', some say they are 'religious symbols'.

A cluster analysis of these 1894 Indus Script Field symbols has also been ignored by the cluster analysis of triplets of 'signs' done by K-means by Nisha Yadav et al. I submit that pictorial motifs or field symbols are integral parts of the hypertext messaging system of the Indus Script inscriptions. It should be noted that these pictorial motifs or field symbols occupy the major portion of the space for messaging used on an inscribed object in Indus Script Corpora (which now total over 8000 inscriptions).

This demonstrable laxity in most decipherment claims or cluster analyses is governed by a hypothesis of the 'text' as the writing system, and perhaps ignoring the field symbol or pictorial motifs are extraneous to the messaging system.