-- Vasu-s, wealth givers, Vṛṣākapi is a Rudra, hunter (Mṛgaśiras, Orion)

This is an addendum to:

Astronomical evidence dates ancient R̥gveda Soma yajña performances from ca.7th millennium BCE -- Narahari Achar https://tinyurl.com/ya969v73

ऋभुक्ष इन्द्र's thunderbolt L.(इन्द्र's) heaven Comm. on Un2. iv , 12; m. इन्द्र L. ऋभुक्षिन् Pa1n2. 7-1 , 85 ff.), N. of the above ऋभुs , and esp. of the first of them RV.;

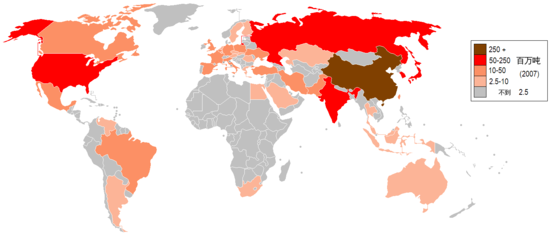

Skilled artisans R̥bhu-s are founders of yajña, Vasu-s, wealth givers, Vṛṣākapi is a Rudra, hunter (Mṛgaśiras, Orion). I suggest that the skilled artisans and seafaring merchants are the architects of Sarasvati Civilization who have left for us the heritage of over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions which are wealth accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues.

The astronomical references point to 8th millennium BCE as the date the yajña wer founded.

Vṛṣākapi is a Rudra. Viṣṇu Purāṇa 1.5 lists eleven Rudra: Hara, Bahurupa, Tryambaka, Aparajita,

Vṛṣākapi, Śambhu, Kaparddi, Raivata, Mrigavyadha, Sarva, and Kapāli. Rudra (/ˈrʊdrə/; Sanskrit: रुद्र) is a Rigvedic deity, associated with wind or storm and the hunt. In RV 7.46, Rudra is described as armed with a bow and fast-flying arrows रुद्र m. " Roarer or Howler " , N. of the god of tempests and father and ruler of the रुद्रs and मरुत्s (in the वेद he is closely connected with इन्द्र and still more with अग्नि , the god of fire , which , as a destroying agent , rages and crackles like the roaring storm , and also with काल or Time the all-consumer , with whom he is afterwards identified ; though generally represented as a destroying deity , whose terrible shafts bring death or disease on men and cattle , he has also the epithet शिव , " benevolent " or " auspicious " , and is even supposed to possess healing powers from his chasing away vapours and purifying the atmosphere ; in the later mythology the word शिव , which does not occur as a name in the वेद , was employed , first as an euphemistic epithet and then as a real name for रुद्र , who lost his special connection with storms and developed into a form of the disintegrating and reintegrating principle ; while a new class of beings , described as eleven [or thirty-three] in number , though still called रुद्रs , took the place of the original रुद्रs or मरुत्s: in VP. i , 7, रुद्र is said to have sprung from ब्रह्मा's forehead , and to have afterwards separated himself into a figure half male and half female , the former portion separating again into the 11 रुद्रs , hence these later रुद्रs are sometimes regarded as inferior manifestations of शिव , and most of their names , which are variously given in the different पुराणs , are also names of शिव ; those of the Va1yuP. are अजैकपाद् , अहिर्-बुध्न्य , हर , निरृत , ईश्वर , भुवन , अङ्गारक , अर्ध-केतु , मृत्यु , सर्प , कपालिन् ; accord. to others the रुद्रs are represented as children of कश्यप and सुरभि or of ब्रह्मा and सुरभि or of भूतand सु-रूपा ; accord. to VP. i , 8, रुद्र is one of the 8 forms of शिव ; elsewhere he is reckoned among the दिक्-पालs as regent of the north-east quarter) RV. &c (cf.RTL. 75 &c )

Mṛgaśira nakṣatra extends from after 23°20 in Vṛṣabha Rāśi up to 6°40 in Mithuna. Star is governed by mars and the presiding deity or God is a Soma God. Soma mean Chandra or Moon God. He hold amrita (nectar or eternity poison ). Symbol is Antelope or Deer. The first two carana/pada (quarters) of this nakṣatra are part of Vṛṣabha Rāśi (Devanagari: वृषभ) or Taurus. The latter half of this star belong to Mithuna Rāśi(Devanagari: मिथुन) or Gemini (from 23°20’ Taurus to 6°40’ Gemini). stars in λ, φ1, φ2 Orionis

7.048.01 R.bhu, (Vibhu), and Va_ja, leaders of rites, possessors of opulence, be exhilarated by our effused (libation); may your active and powerful (horses) bring to our presence your chariot, beneficial to mankind. [r.bhuks.an.o va_jah, the use of the plural implies that the three brothers are intended].

7.048.02 Mighty with the R.bhus, opulent with the Vibhus, may we overcome by strength, the strength (of our foes); may Va_ja defend us in battle; with Indra, our ally, may we destroy the enemy. [R.bhus: r.bhur r.bhubhih vibhvo vibhubhih: r.bhu and uru = great; vibhu vibhvah = rich or powerful].

7.048.03 They verily, (Indra and R.bhus), overcome multitudes by their prowess; they overcome all enemies in the missile conflict; may Indra, Vibhvan, R.bhuks.in and Va_ja, the subduers of foes, annihilate by their wrath the strength of the enemy. [Missile: uparata_ti: upara = upala, a stone; upalaih pa_s.a_n.asadr.s'air a_yudhai ta_yate yuddham, war that is waged with weapons like stones, is uparatati].

7.048.04 Grant us, deities, this day opulence; may you all, may you all, well-pleased alike, be (ready) for our protection; may the exalted (R.bhus) bestow upon us food; and do you (all) ever cherish us with blessings. [R.bhus: vasavah = Vasus; pras'asyah, an epithet of R.bhavah].

Vṛṣākapi (वृषाकपि):—One of the Eleven Rudras (ekādaśa-rudra), according to the Agni-purāṇa. The Agni Purāṇa is a religious text containing details on Viṣṇu’s different incarnations (avatar), but also deals with various cultural subjects such as Cosmology, Grammar and Astrology. Vṛṣākapi (वृषाकपि).—A Rudra, and a son of Bhūta and Sarūpā: Fought with Jambha in the Devāsura war.

Viṣṇu Purāṇa 1.5 being devoted to it, was the wife of Prabhasa, the eighth of the Vasus, and bore to him the patriarch Viswakarma, the author of a thousand arts, the mechanist of the gods, the fabricator of all ornaments, the chief of artists, the constructor of the self moving chariots of the deities, and by whose skill men obtain subsistence. Ajaikapad, Ahirvradhna, and the wise Rudra Twashtri, were born; and the self born son of Twashtri was also the celebrated Viswarupa. There are eleven well known Rudras, lords of the three worlds, or Hara, Bahurupa, Tryambaka, Aparajita, Vrishakapi, Sambhu, Kaparddi, Raivata, Mrigavyadha, Sarva, and Kapali 17; but there are a hundred appellations of the immeasurably mighty Rudras 18.

AtharvavedaAV 20.126

Where at the votary s store my friend Vrishakapi hath drunk his fill.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012602] Thou, Indra, heedless passest by the ill Vrishakapi hath wrought; Yet nowhere else thou findest place wherein to drink the Soma juice.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012603] What hath he done to injure thee, this tawny beast Vrishakapi, With whom thou art so angry now? What is the votary s food ful store? Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012604] Soon may the hound who hunts the boar seize him and bite him in the ear, O Indra, that Vrishakapi whom thou protectest as a friend.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012605] Kapi hath marred the beauteous things, all deftly wrought, that were my joy.

In pieces will I rend his head; the sinner s portion shall be woe.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012606] No dame hath ampler charms than I, or greater wealth of love s delights.

None with more ardour offers all her beauty to her lord s embrace.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012607] Mother whose love is quickly won,I say what verily will be, My breast, O mother, and my head and both my hips seem quivering Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012608] Dame with the lovely hands and arms, with broad hair plaits and ample hips, Why, O thou hero s wife, art thou angry with our Vrishakapi? Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012609] This noxious creature looks on me as one bereft of hero s love. [p. 361] Yet heroes for my sons have I, the Maruts friend and Indra s Queen Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012610] From olden time the matron goes to feast and general sacrifice.

Mother of heroes, Indra s Queen, the rite s ordainer is extolled.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012611] So have I heard Indrani called most fortunate among these dames, For never shall her Consort die in future time through length of days.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012612] Never, Indrani have I joyed without my friend Vrishakapi, Whose welcome offering here, made pure with water, goeth to the Gods.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012613] Wealthy Vrishakapayi, blest with sons and consorts of thy sons, Indra will eat thy bulls, thy dear oblation that effecteth much.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012614] Fifteen in number, then, for me a score of bullocks they prepare.

And I devour the fat thereof: they fill my belly full with food.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012615] Like as a bull with pointed horn, loud bellowing amid the herds, Sweet to thine heart, O Indra, is the brew which she who tends thee pours.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012616] Indrani speaks.

Non ille fortis (ad Venerem) est cujus mentula laxe inter femora dependet; fortis vero estille cujus, quum sederit, membrum pilosum se extendit.

Super omnia est Indra.

[2012617] Indra speaks.

Non fortis est ille cujus, quum sederit, membrum pilosum se extendit: fortis vero est ille cujus mentula laxe inter femora dependet.

Super omnia est Indra.

[2012618] O Indra, this Vrishakapi hath found a slain wild animal, Dresser, and new made pan, and knife, and wagon with a load of wood.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012619] Distinguishing the Dasa and the Arya, viewing all, I go.

I look upon the wise, and drink the simple votary s Soma juice.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012620] The desert plains and steep descents, how many leagues in length they spread! Go to the nearest houses, go unto thine home, Vrishakapi.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012621] Turn thee again Vrishakapi; we twain will bring thee happiness.

Thou goest homeward on thy way along this path which leads to sleep.

Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012622] When, Indra and Vrishakapi, ye travelled upward to your home, Where was that noisome beast, to whom went it, the beast that troubles man? Supreme is Indra over all.

[2012623] Daughter of Manu, Parsu bare a score of children at a birth. [p. 362] Her portion verily was bliss although her burthen caused her grief.

[p. 363]

The legend of vr̥ṣākapi The legend appears in R̥gVeda X.86 which is not an easy hymn to understand. Tilak (1893) gives a long verse by verse discussion of this hymn and concludes that the import of the legend can be understood by taking vr̥ṣākapi to represent the sun at vernal equinox when the dog star started the equinoctial year. Again Tilak interpreted this to mean vernal equinox occurring at Orion. However, it is our opinion that this legend also refers to the same event namely the equinoctical year with the Dog star and is illustrated by the figure 8.

1.020.01 This hymn, the bestower of riches, has been addressed by the sages, with their own mouths, to the (class of) divinities having birth (lit. to the divine or brilliant birth; e.g. R.bhus--R.bhu, Vibhu and Va_ja were pious men, who through penance became divinities). [deva_ya janmane: lit. to the divine or brilliant birth; janmane: ja_yama_na_ya, being born, or having birth; deva_ya: deva-san:gha_ya, a class of divinities, R.bhus who achieved deification: manus.ya_h santastapasa_ devatvam pra_pta_h. R.bhus were three sons of Sudhanvan, a descendant of An:giras. Through their good work (svapas = su-apas), they became divine, exercised superhuman powers and became entitled to receive praise and adoration. They dwell in the solar sphere, identified with the rays of the sun].

1.020.02 They who created mentally for Indra the horses that are harnessed (carved) at his words, have partaken of the sacrifice performed with holy acts. (s'ami_bhih = ceremonies; i.e. they have pervaded, appropriated or accepted the sacrifice peformed with tongs, ladles, and utensils; an intimation of the mechanical skills of R.bhu). [grahacamasa_dinis'pa_danaru_paih karmabhir, yajn~am, asmadi_yam a_s'ata (vya_ptavantah): they have pervaded (or accepted) our sacrifice, performed with those acts which are executed by means of tongs, ladles, and other (utensils used in oblations). R.bhus invented these implements, and attest to their mechanical skills].

1.020.03 They constructed for the Na_satya_s, a universally-moving and easy car, and a cow yielding milk. (taks.an = ataks.an, lit. they (R.bhus) chipped or fabricated, mechanically, the appendages of Indra and As'vin). [They carved (tataks.uh) Indar's horse; they did it mentally (ma_nasa)].

1.020.04 The R.bhus, uttering unfailing prayers, endowed with rectitude, and succeeding (in all pious acts; vis.t.i_ = vya_ptiyuktah, i.e. encountering no opposition in all acts), made their (aged) parents young. [satya-mantra_h = repeating true prayers, i.e. prayers certain to achieve the objects prayed for; akrata: fr. kr., to make generally].

1.020.05 R.bhus, the exhilarating juices are offered to you, along with Indra, attended by the Maruts and along with the brilliang A_dityas. [Libations offered at the third daily, or evening sacrifice, are presented to Indra, along with the A_dityas, together with R.bhu, Vibhu and Va_ja, with Br.haspati and the Vis'vedeva_s (A_s'vala_yana S'rauta Su_tra, 5.3)].

1.020.06 The R.bhus have divided unto four the new ladle, the work of the divine Tvas.t.a_ (i.e. devasambandhih taks.ana.vya_pa_rah = divinity whose duty in relations to gods is carpentry; cf. tvas.t.a_ tvas.t.uh s'is.ya_h R.bhavah = R.bhus are the disciples of Tvas.t.a_; four ladles are an apparent reference to an innovation in the objects of libation for sharing). [Tvas.t.a_ is the artisan of the gods; he is a divinity whose duty is carpentry, with relation to the gods].

1.020.07 May they, moved by our praises, give to the offere of the libation many precious things, and perfect the thrice seven sacrifices [i.e. seven sacrifices in each of three classes: agnya_dheyam (clarified butter), pa_kayajn~a (dressed viands), agnis.t.oma (soma)]. [Trira_ sa_pta_ni: trih may be applied to precious things to sa_pta_ni, seven sacrifices].

1.020.08 Offerers (of sacrifices), they held (a moral existence); by their pious acts they obtained a share of sacrifices with the gods. [a_dha_rayanta = they held or enjoyed (pra_n.a_n, i.e. vital airs, life)] [marta_sah santo amr.tatvam anas'uh: beyong mortals, they obtained immprtality (RV. 1.110.4); saudhanvana_ yajn~iyam bha_gam a_nas'a: by the son of Sudhanvan was a sacrificial portion acquired (RV. 1.60.1); r.bhavo vai deves.u tapasa_ somapi_tham abhyajayan: r.bhus won by devotion the drinking of Soma among the gods (Aitareya Bra_hman.a 3.30)].

1.110.01 R.bhus, the rite formerly celebrated by me is again repeated, and the melodious hymn is recited in your praise; in this ceremony, the Soma is sufficient for all the gods; drink of it to your utmost content when offered on the fire.

1.110.02 When, R.bhus, you who are amongst my ancestors, yet immature (in wisdom), but desirous of enjoying (the Soma libations), retired to the forest to perform (penance), then, sons of Sudhanvan, throught he plenitude of your completed (devotions), you came to the (sacrificial) hall of the worshipper Savita_. [r.bhurvibhva_ va_ja iti sudhanvana a_n:girasasya trayah putra_h babhu_vuh (Nirukta 11.16): Sudhanvan, father of the R.bhus, was a descendant of An:giras; so is Kutsa; pra_n~cah = pu_rva ka_li_na, of a former period; Kutsa is a kinsman of R.bhus of a former period].

1.110.03 Then Savita_ bestowed upon you immortality, when you came to him, who is not to be concealed, and representd (your desire) to partake of the libations; and that ladle for the sacrificial viands which the Asura had formed single, you made fourfold. [Who is not to be concealed: In the previous hymn, Savita_ (fr. su, to offer oblations) perhaps refers to the presenter of oblations; in this hymn, the sun is alluded to].

1.110.04 Associated with the priests, and quickly performing the holy rites, they, being yet mortals, acquired immortality and the son of Sudhanvan, the R.bhus, brilliant as the sun, became connected with the ceremonies (appropriated to the different season) of the year.

1.110.05 Lauded by the bystanders, the R.bhus, with a sharp weapon, meted out the single sacrificial ladle, like a field (measured by a rod), soliciting the best (libations) and desiring (to participate of) sacrificial food amongs thte gods.

6 To the leaders (of the sacrifice), dwelling in the firmament, we present, as with a ladle, the appointed clarified butter, and praise with knowledge those R.bhus, who, having equalled the velocityof the protector (of the universe, the sun), ascended to the region of heaven, through (the offerings) of (sacrificial) food. [nr.bhyah = yajn~asya netr.bhyah; r.bhavo hi yajn~asya neta_rah: 'the r.bhus are the leaders of the sacrifice'; because of this position, they obtained immortality; the term is perhaps connected with antariks.asya, to the chief of the firmament; r.bhus also identified with the solar rays (a_dityaras'mayo api r.bhava ucyanti: the r.bhus are, indeed, said to be the rays of the sun].

1.110.07 The most excellent R.bhu is in strength our defender; R.bhu, through gifts of food and of wealth, is our asylum; may he bestow them upon us, Gods, through your protection; may we, upon a favourable occasion, overcome the hosts of those who offer no libations.

1.110.08 R.bhus, you covered the cow with a hide, and reunited themother with the calf; sons of Sudhanvan, leaders (of sacrifice), through your good works you rendered your aged parents young. [Legend: a r.s.i, whose cow had died, leaving a calf prayed to the r.bhus for assistance, on which, they formed a living cow, and covered it with the skin of the dead one, from which the calf imagined it to be its own mother].

1.110.09 Indra, associated with the R.bhus, supply us, in the distribution of viands, with food, and consent to bestow upon us wonderful riches; and may Mitra, Varun.a, Aditi--ocean, earth, and heaven, preserve them fo rus. [alternative: va_jebhir no va_jasa_tau aviddhi = protect us in battle with your horses].

1.161.01 Is this our senior or our junior who has come (to us); has he come upon a message (from the gods); what is it we should say? Agni,brother, we revile not the ladle which is of exalted race; verily we assert the dignity of the wooden (implement). [The legend: the three R.bhus were engaged in a sacrifice and about to drink the Soma; the gods sent Agni to see what they were doing. Agni noticed that they resembled each other; Agni assumed a like form. The hymn refers to this form, calling him brother, and questionign his comparative age. The next hymn states the purpose of Agni's visit is to order the conversion of one spoon or ladle, camasa, used for drinking Soma, or for libations, into four spoons].

1.161.02 Make fourfold the single ladle; so the gods command you; and for that purpose have I come, sons of Sudhanvan; if you accomplish this, you will be entitled to sacrifices along with the gods.

1.161.03 Then said they, in answer to Agni, the messenger (of the gods). Whatever is to be done, whether a horse is to be made, or a car is to be made, or a cow is to be made, or the two (old parents) are to be made young, having done all these (acts), Brother Agni, we are then ready to do (what you desire) to be done. [cf. su_ktas 20, 110 and 111 which relate the marvels of the R.bhus].

1.161.04 So doing R.bhus, you inquired: where, indeed, is he who came to us as a messenger? When Tvas.t.a_ observed the one ladle become four, he was immediately lost amongst the women. [gna_su antarnya_naje; the verb is explained: nyakto abhu_t; the combination of ni and anj is perhaps the converse of vyan~j, to be manifest, i.e. to be concealed, indistinct, or invisible. gna_ = stri_ (mena gna_ iti stri_n.a_m--Nirukta 3.21); str.yam a_tma_nam amanyata = he, Tvas.t.a_, fancied himself; woman, that is, he felt humbled, as feeble as a female].

1.161.05 When Tvas.t.a_ said: let us slay those who have profaned the ladle, (designed) for the drinking of the gods; then they made use of other names for one another as the libation was poured out; and the maiden (mother) propitiated them by different appellations. [Then they made us of other names: a legend accounts for the origin of the names of the chief officiating priests; to evade the indignation of Tvas.t.a_, the R.bhus assumed the titles: adhvaryu, hota_ and udgata_;an individual engaged in priestly functions at a sacrifice is to be always addressed by these titles, and never by his own name; propitiated them by different appellations: anyair ena_n kanya_ na_mabhih sparat: kanya_ = svotpa_dayitri_ ma_ta_, a mother self-engendering].

1.161.06 Indra has caparisoned his horses; the As'vins have harnessed their car; Br.haspati has accepted the omniform (cow); therefore, R.bhu, Vibhva and Va_ja, go the gods, doers of good deeds, enjoy your sacrificial portion.

1.161.07 Sons of Sudhanvan, from a hideless (cow) you have formed a living one; by your marvellous acts you have made your aged parents young; from one horse you have fabricated another; harness now your chariot, and repair unto the gods.

1.161.08 They, (the gods), have said, sons of Sudhanvan, drink of this water, (the Soma); or drink that which has been filtered through the mun~ja grass; or, if you be pleased with neither of these, be exhilarated (by that which is drunk) at the third (daily) sacrifice. [R.bhus may be participants of the libations offered at dawn or at noon; the right of the R.bhus to share in the third, or evening sacrifice is always acknowledged].

1.161.09 Waters are the most excellent said one (of them). Agni is that most excellent, said another; the third declared to many the Earth (to be the most excellent), and thus speaking true things the R.bhus divided the ladle. [The earth: vardhayanti_m = a line of clouds or the earth: vadhah arkah (Nirukta 2.20.7)].

1.161.10 One pours the red water (the blood) upon the ground; one cuts the flesh, divided into fragments by the chopper; and a third seperates the excrement from the other parts; in what manner may the parents (of the sacrifice) render assistance to their sons? [The R.bhus are identified with the priests employed in the sacrifice of a victim; the parents of the sacrifice: the parents pitr.s, = the institutor of the ceremony and his wife].

1.161.11 R.bhus, leaders (of the rains), you have caused the grass to grow upon the high places; you have caused the waters to flow over the low places; for (the promotion of) good works; as you have reposed for a while in the dwelling of the unapprehensible (Sun), so desist not today from (the discharge of) this (your function). [R.bhus are identified in this and following hymns with the rays of the sun, as the instruments of the rain and the causes of fertility; a_dityaras'mayo api r.bhava ucyante: (Nirukta 11.16); unapprehensible Sun: agohyasya gr.he: agohya = a name of the sun (Nirukta); who is not to be hidden, aguhani_ya;or, agrahan.i_ya, not to be apprehended, literally or metaphorically; so desist not: idam na_nugacchatha; anusr.tya na gacchatha, having come forth, go not away without doing this,idam, your office of sending down rain for as long a period as you repose in the solar orb; a truism is explained in Nirukta: ya_vat tatra bhavatha na ta_vadiha bhavatha, as long as you are there, you are not here].

1.161.12 As you glide along enveloping the regions (in clouds); where, then, are the parents (of the world)? curse him who arrests your arm; reply sternly to him who speaks disrespectfully (to you). [The parents of the world: the sun and the moon, the protectors of the world, which, during the rains, are hidden by the clouds; who speaks disrespectfully: yah pra_bravi_t pra tasma_ abravi_tana: pra prefixed to bru_ = either to speak harshly or kindly, to censure or to praise].

1.161.13 R.bhus, reposing in the solar orb, you inquire: who awakens us, unapprehensive (Sun), to this office (of sending rain). The Sun replies: the awakener is the wind; and the year (being ended), you again today light up this (world). [The awakener is the wind: s'va_nam bodhayita_ram = the awakener is the dog; but, s'va_nam = antarks.e svasantam va_yum, the reposer in the firmament, the wind; sam.vatsare idam adya_ vyakhyata, you have made this world today luminous, after the year has expired; i.e. the rainy season has passed, the rays of the sun and moon are again visible].

1.161.14 Sons of Strength, the Maruts, desirous of your coming, advance from the sky; Agni comes (to meet you) from the earth; the wind traverses the firmament; and Varun.a comes with undulating waters.

1.161.02 Make fourfold the single ladle; so the gods command you; and for that purpose have I come, sons of Sudhanvan; if you accomplish this, you will be entitled to sacrifices along with the gods.

1.161.03 Then said they, in answer to Agni, the messenger (of the gods). Whatever is to be done, whether a horse is to be made, or a car is to be made, or a cow is to be made, or the two (old parents) are to be made young, having done all these (acts), Brother Agni, we are then ready to do (what you desire) to be done. [cf. su_ktas 20, 110 and 111 which relate the marvels of the R.bhus].

1.161.04 So doing R.bhus, you inquired: where, indeed, is he who came to us as a messenger? When Tvas.t.a_ observed the one ladle become four, he was immediately lost amongst the women. [gna_su antarnya_naje; the verb is explained: nyakto abhu_t; the combination of ni and anj is perhaps the converse of vyan~j, to be manifest, i.e. to be concealed, indistinct, or invisible. gna_ = stri_ (mena gna_ iti stri_n.a_m--Nirukta 3.21); str.yam a_tma_nam amanyata = he, Tvas.t.a_, fancied himself; woman, that is, he felt humbled, as feeble as a female].

1.161.05 When Tvas.t.a_ said: let us slay those who have profaned the ladle, (designed) for the drinking of the gods; then they made use of other names for one another as the libation was poured out; and the maiden (mother) propitiated them by different appellations. [Then they made us of other names: a legend accounts for the origin of the names of the chief officiating priests; to evade the indignation of Tvas.t.a_, the R.bhus assumed the titles: adhvaryu, hota_ and udgata_;an individual engaged in priestly functions at a sacrifice is to be always addressed by these titles, and never by his own name; propitiated them by different appellations: anyair ena_n kanya_ na_mabhih sparat: kanya_ = svotpa_dayitri_ ma_ta_, a mother self-engendering].

1.161.06 Indra has caparisoned his horses; the As'vins have harnessed their car; Br.haspati has accepted the omniform (cow); therefore, R.bhu, Vibhva and Va_ja, go the gods, doers of good deeds, enjoy your sacrificial portion.

1.161.07 Sons of Sudhanvan, from a hideless (cow) you have formed a living one; by your marvellous acts you have made your aged parents young; from one horse you have fabricated another; harness now your chariot, and repair unto the gods.

1.161.08 They, (the gods), have said, sons of Sudhanvan, drink of this water, (the Soma); or drink that which has been filtered through the mun~ja grass; or, if you be pleased with neither of these, be exhilarated (by that which is drunk) at the third (daily) sacrifice. [R.bhus may be participants of the libations offered at dawn or at noon; the right of the R.bhus to share in the third, or evening sacrifice is always acknowledged].

1.161.09 Waters are the most excellent said one (of them). Agni is that most excellent, said another; the third declared to many the Earth (to be the most excellent), and thus speaking true things the R.bhus divided the ladle. [The earth: vardhayanti_m = a line of clouds or the earth: vadhah arkah (Nirukta 2.20.7)].

1.161.10 One pours the red water (the blood) upon the ground; one cuts the flesh, divided into fragments by the chopper; and a third seperates the excrement from the other parts; in what manner may the parents (of the sacrifice) render assistance to their sons? [The R.bhus are identified with the priests employed in the sacrifice of a victim; the parents of the sacrifice: the parents pitr.s, = the institutor of the ceremony and his wife].

1.161.11 R.bhus, leaders (of the rains), you have caused the grass to grow upon the high places; you have caused the waters to flow over the low places; for (the promotion of) good works; as you have reposed for a while in the dwelling of the unapprehensible (Sun), so desist not today from (the discharge of) this (your function). [R.bhus are identified in this and following hymns with the rays of the sun, as the instruments of the rain and the causes of fertility; a_dityaras'mayo api r.bhava ucyante: (Nirukta 11.16); unapprehensible Sun: agohyasya gr.he: agohya = a name of the sun (Nirukta); who is not to be hidden, aguhani_ya;or, agrahan.i_ya, not to be apprehended, literally or metaphorically; so desist not: idam na_nugacchatha; anusr.tya na gacchatha, having come forth, go not away without doing this,idam, your office of sending down rain for as long a period as you repose in the solar orb; a truism is explained in Nirukta: ya_vat tatra bhavatha na ta_vadiha bhavatha, as long as you are there, you are not here].

1.161.12 As you glide along enveloping the regions (in clouds); where, then, are the parents (of the world)? curse him who arrests your arm; reply sternly to him who speaks disrespectfully (to you). [The parents of the world: the sun and the moon, the protectors of the world, which, during the rains, are hidden by the clouds; who speaks disrespectfully: yah pra_bravi_t pra tasma_ abravi_tana: pra prefixed to bru_ = either to speak harshly or kindly, to censure or to praise].

1.161.13 R.bhus, reposing in the solar orb, you inquire: who awakens us, unapprehensive (Sun), to this office (of sending rain). The Sun replies: the awakener is the wind; and the year (being ended), you again today light up this (world). [The awakener is the wind: s'va_nam bodhayita_ram = the awakener is the dog; but, s'va_nam = antarks.e svasantam va_yum, the reposer in the firmament, the wind; sam.vatsare idam adya_ vyakhyata, you have made this world today luminous, after the year has expired; i.e. the rainy season has passed, the rays of the sun and moon are again visible].

1.161.14 Sons of Strength, the Maruts, desirous of your coming, advance from the sky; Agni comes (to meet you) from the earth; the wind traverses the firmament; and Varun.a comes with undulating waters.

4.033.01 I send my prayer as a messenger to the r.bhus; I solicit (of them) the cow, the yielder of the white milk, for the dilution (of the Soma libation); for they, as swift as the wind, the doers of good works, were borne quickly across the firmament by rapid steeds. [WSere borne quickly: as applicable to the deified mortals, the allusion is to their being transported to the sphere of the gods; if the reference is to the rays of the sun, it implies merely their dispersal through the sky].

4.033.02 When the r.bhus, by honouring their parents with renovated (youth), and by other works, had achieved enough, they thereupon proceeded to the society of the gods, and, considerate, they bring nourishment to the devout (worshipper).

4.033.03 May they who rendered their decrepid and dropsy parents, when, like two dry posts, again perpetually young, Va_ja, Vibhavan, and R.bhu associated with Indra, drinkers of the Soma juice, protect our sacrifice.

4.033.04 Inasmuch as for a year the R.bhus preserved the (dead) cow, inasmuch as for a year they invested it with flesh, inasmuch as for a year they continued its beauty they obtained by their acts of immortality.

4.033.05 The eldest said, let us make two ladles; the younger said, let us make three: Tvas.t.a_, R.bhus, has applauded your proposal.

4.033.06 The men, (the R.bhus), spoke the truth, for such (ladles) they made, and thereupon the R.bhus partook of that libation; Tvas.t.a_, beholding the four ladles, brilliant as day, was content.

4.033.07 When the R.bhus, reposing for twelve days, remained in the hospitality of the uncealable (sun) they rendered the fields fertile, they led forth the rivers, plants sprung upon the waste, and waters (spread over) the low (places).

4.033.08 May those R.bhus who constructed the firm-abiding wheel-conducting car; who formed the all-impelling multiform cow; they who are the bestowers of food, the doers of great deeds, and dexterous of hand, fabricate our riches.

4.033.09 The gods were pleased by their works, illustrious in act and in thought; Va_ja was the artificer of the gods, R.bhuks.in of Indra, Vibhavan of Varun.a.

4.033.10 May those R.bhus who gratified the horses (of Indra) by pious praise, who constructed for Indra his two docile steeds, bestow upon us satiety of riches, and wealth (of cattle), like those who devise prosperity for a friend.

4.033.11 The gods verily have given you the beverage at the (third sacrifice of the) day, and its exhilarqation, not through regard, but (as the gift of one) wearied out (by penance); R.bhus, who are so (eminent), grant us, verily, wealth at this third (diurnal) sacrifice. [Wearied out by penance: r.te s'ra_ntasya sakhya_ya = na sakhitva_ya bhavanti deva_h, the gods are not through friendship, s'ra_nta_t tapo yukta_t r.te except one wearied by penance; ete s'ra_nta ato saduh, they, wearied out, therefore gave].

4.037.01 Divine Va_jas, R.bhus, come to our sacrifice by the path travelled by the gods, inasmuch as you, gracious (R.bhus), have maintained sacrifice among the people, (the progeny) of Manu, for (the sake of) securing the prosperous course of days. [R.bhus: the text has r.bhuks.ah, nom. sing. of r.bhuks.in, a name of Indra; here, it is equated with r.bhavah, pl. nom. of r.bhu; in the following verses r.bhuks.a_n.ah is used, the nom. or voc. pl. of r.bhuks.in].

4.037.02 May these sacrifices be (acceptable) to you in heart and mind; may today the sufficient (juices) mixed with butter to you; the full libations are prepared for you; may they, when drunk, animate you for glorious deeds.

4.037.03 As the offering suited to the gods at the third (daily) sacrifice supports, you, Va_jas, R.bhuks.ans; as the praise (then recited supports you); therefore, like Manu, I offer you the Soma juice, along with the very radiant (deities) among the people assembled at the solemnity. [I offer you: juhve manus.vat uparasu viks.u yus.me saca_ br.had dives.u somam: upara = those who are pleased or sport near the worship of the gods, devayajana sami_pe ramantah; ta_su viks.u-praja_su = in or among such people; br.haddives.u is an epithet of deves.u implied].

4.037.04 Va_jins, you are borne by stout horses mounted on a brilliant car, have jaws of metal and are possessed of treasures; sons of Indra, grandsons of strength, this last sacrifice is for your exhilaration. [Possessed of treasures: va_jinah = possessors either of horses or food; ayahs'ipra_ = as hard or strong as metal, ayovat sa_rabhu_ta s'ipra_h; sunis.ka_h = having good nis.kas, a certain weight of gold; sons of Indra, grandsons of strength: the text has singular nouns, son of Indra, son or grandson of strength; this is followed by vah-vos, you in the plural; last sacrifice: ityagriyam = agre bhavam, the first, the preceding; explained as tr.ti_yam savanam].

4.037.05 We invoke you, R.bhuks.ans, for splendid wealth, mutually co-operating, most invigorating in war, affecting the senses, ever munificent, and comprehending horses. [Splendid wealth: the epithets apply to rayim, wealth: r.bhu yujam, va_jintamam, indrasvantam, sada_sa_tamam as'vinam].

4.037.06 May the man whom you, R.bhus and Indra, favour, be ever liberal by his acts, and possessed of a horse at the sacrifice. [A horse at the sacrifice: medhasa_ta_ so arvata_, perhaps a horse fit for the as'vamedha is implied].

4.037.07 Va_jas, R.bhuks.an.s, direct us in the way to sacrifice; for you, who are intelligent, being glorified (by us), are able to traverse all the quarters (of space).

4.037.08 Va_jas, R.bhuks.an.s, Indra, Na_satyas, command that ample wealth with horses be sent to men for their enrichment.

Constellation Orioon

The legend of R̥bhu-s

R̥bhu-s occur in eleven suktas in R̥gVeda, I. 20, I. 110, I.161, I. 164, IV. 33- IV.-37.

R̥bhu-s are three in number, R̥bhu, vibhvan and vaj and are the sons of Sudhanvan. They learnt many crafts under Tvaṣṭr̥, and constructed rathas and other equipment for the devas. By their hard work the devas were pleased and they were granted immortality. saudhanvanā R̥bhava¨sūraacakṣasah¨ samvatsare samapr̥cyanta dhītibhih¨ RV (I. 110.4) The R̥bhu-s, children of Sudhanvan, bright as suns, were in a year's course made associate with prayers ('connected with the ceremonies appropriated to the different seasons of the year'-Wilson) The R̥bhus represent the three seasons of the year (lunar year of 354 days) at the end of which they take rest for 12 days in the house of aghohya (the unconcealable, the sun) before they start their work again in the New Year. They are

awakened from their sleep and vasta gives the information that they were awakened by the hound. suṣupvāmsa r̥bhavaastadāpr̥cchat āgohya ka idam no abūbudhatśvānam bastobodhayitāram abravīt samvatsara idamadyā vyākhyata (RV 1.161.13) R̥bhus, reposing in the solar orb, you inquire, 'who wakens us, unconcealable sun to this office of sending rain?'. Sun replies 'the awakener is the Dog and in the year you again today light up this world'. This legend can be taken as referring to the time of commencement of the year with vernal equinox. The śvāna obviously refers to the Dog star. Tilak(1893) regards this as referring to the equinox in mr̥gaśiras (identified by him with the constellation Orion, which according to him also includes the Dog-star). He supported his interpretation with a large number of quotations from R̥gveda and other Vedic texts. The date corresponding to the occurrence of vernal equinox at the Orion can be simulated assuming that the Orion is represented by its brightest star, α-Ori, also known as Betelguese. The vernal equinox occurring at α-Ori is shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. Vernal Equinox at α-Ori. 5000 BCE. Note the passing of zero hour line of the coordinate Right Ascension (RA) through Betelguese.

Tilak(1893) in his book The Orion first proposed the date of 4500 BCE, and then later on proposed the date of 5000 BCE. However, Sengupta interprets the R̥bhu legend as referring to the heliacal rising of Canis Major after the summer solstice. But this is not the correct interpretation either, as the beginning of the New Year was most likely at the vernal equinox.

The legend refers to the vernal equinox, with the Dog star (Sirius) at the vernal equinox and is illustrated in Figure 8.![]()

Translation: Griffith

Indra. 86

1. MEN have abstained from pouring juice they count not Indra as a God.

Where at the votarys' store my friend Vṛṣākapi hath drunk his fill. Supreme is Indra over all.

2 Thou, Indra, heedless passest by the ill Vṛṣākapi hath wrought;

Yet nowhere else thou findest place wherein to drink the Soma juice. Supreme is Indra over all.

3 What hath he done to injure thee, this tawny beaVṛṣākapi,

With whom thou art so angry now? What is the votarys' foodful store? Supreme is Indra over all.

4 Soon may the hound who hunts the boar seize him and bite him in the car,

O Indra, that Vṛṣākapi whom thou protectest as a friend, Supreme is Indra over all.

5 Kapi hath marred the beauteous things, all deftly wrought, that were my joy.

In pieces will I rend his head; the sinners' portion sball be woo. Supreme is Indra over all.

6 No Dame hath ampler charms than 1, or greater wealth of loves' delights.

None with more ardour offers all her beauty to her lords' embrace. Supreme is Indra over all.

7 Mother whose love is quickly wibn, I say what verily will be.

Mybreast,, O Mother, and my head and both my hips seem quivering. Supreme is Indra over all.

8 Dame with the lovely hands and arms, with broad hairplaits- add ample hips,

Why, O thou Heros' wife, art thou angry with our Vṛṣākapi? Supreme is Indra over all.

9 This noxious creature looks on me as one bereft of heros' love,

Yet Heroes for my sons have I, the Maruts? Friend and Indras' Queen. Supreme is Indra over all.

10 From olden time the matron goes to feast and general sacrifice.

Mother of Heroes, Indras' Queen, the rites' ordainer is extolled. Supreme is Indra over all.

11 So have I heard Indrani called most fortunate among these Dames,

For never shall her Consort die in future time through length of days. Supreme is Indra overall.

12 Never, Indralni, have I joyed without my friend Vṛṣākapi,

Whose welcome offering here, made pure with water, goeth to the Gods. Supreme is Indra over all.

13 Wealthy Vṛṣākapayi, blest with sons and consorts of thy sons,

Indra will eat thy bulls, thy dear oblation that effecteth much. Supreme is Indra over all.

14 Fifteen in number, then, for me a score of bullocks they prepare,

And I devour the fat thereof: they fill my belly full with food. Supreme is Indra over all.

15 Like as a bull with pointed horn, loud bellowing amid the herds,

Sweet to thine heart, O Indra, is the brew which she who tends thee pours. Supreme is Indra over

all.

18 O Indra this Vṛṣākapi hath found a slain wild animal,

Dresser, and newmade- pan, and knife, and wagon with a load of wood. Supreme is Indra over all.

19 Distinguishing the Dasa and the Arya, viewing all, I go.

I look upon the wise, and drink the simple votarys' Soma juice. Supreme is Indra over all.

20 The desert plains and steep descents, how many leagues in length they spread!

Go to the nearest houses, go unto thine home, Vrsakapi. Supreme is Indra over all.

21 Turn thee again Vṛṣākapi: we twain will bring thee happiness.

Thou goest homeward on thy way along this path which leads to sleep. Supreme is Indra over all.

22 When, Indra and Vṛṣākapi, ye travelled upward to your home,

Where was that noisome beast, to whom went it, the beast that troubles man? Supreme is Indra over

all.

23 Daughter of Manu, Parsu bare a score of children at a birth. Her portion verily was bliss although her burthen caused her grief.

Where at the votarys' store my friend Vṛṣākapi hath drunk his fill. Supreme is Indra over all.

2 Thou, Indra, heedless passest by the ill Vṛṣākapi hath wrought;

Yet nowhere else thou findest place wherein to drink the Soma juice. Supreme is Indra over all.

3 What hath he done to injure thee, this tawny beaVṛṣākapi,

With whom thou art so angry now? What is the votarys' foodful store? Supreme is Indra over all.

4 Soon may the hound who hunts the boar seize him and bite him in the car,

O Indra, that Vṛṣākapi whom thou protectest as a friend, Supreme is Indra over all.

5 Kapi hath marred the beauteous things, all deftly wrought, that were my joy.

In pieces will I rend his head; the sinners' portion sball be woo. Supreme is Indra over all.

6 No Dame hath ampler charms than 1, or greater wealth of loves' delights.

None with more ardour offers all her beauty to her lords' embrace. Supreme is Indra over all.

7 Mother whose love is quickly wibn, I say what verily will be.

Mybreast,, O Mother, and my head and both my hips seem quivering. Supreme is Indra over all.

8 Dame with the lovely hands and arms, with broad hairplaits- add ample hips,

Why, O thou Heros' wife, art thou angry with our Vṛṣākapi? Supreme is Indra over all.

9 This noxious creature looks on me as one bereft of heros' love,

Yet Heroes for my sons have I, the Maruts? Friend and Indras' Queen. Supreme is Indra over all.

10 From olden time the matron goes to feast and general sacrifice.

Mother of Heroes, Indras' Queen, the rites' ordainer is extolled. Supreme is Indra over all.

11 So have I heard Indrani called most fortunate among these Dames,

For never shall her Consort die in future time through length of days. Supreme is Indra overall.

12 Never, Indralni, have I joyed without my friend Vṛṣākapi,

Whose welcome offering here, made pure with water, goeth to the Gods. Supreme is Indra over all.

13 Wealthy Vṛṣākapayi, blest with sons and consorts of thy sons,

Indra will eat thy bulls, thy dear oblation that effecteth much. Supreme is Indra over all.

14 Fifteen in number, then, for me a score of bullocks they prepare,

And I devour the fat thereof: they fill my belly full with food. Supreme is Indra over all.

15 Like as a bull with pointed horn, loud bellowing amid the herds,

Sweet to thine heart, O Indra, is the brew which she who tends thee pours. Supreme is Indra over

all.

18 O Indra this Vṛṣākapi hath found a slain wild animal,

Dresser, and newmade- pan, and knife, and wagon with a load of wood. Supreme is Indra over all.

19 Distinguishing the Dasa and the Arya, viewing all, I go.

I look upon the wise, and drink the simple votarys' Soma juice. Supreme is Indra over all.

20 The desert plains and steep descents, how many leagues in length they spread!

Go to the nearest houses, go unto thine home, Vrsakapi. Supreme is Indra over all.

21 Turn thee again Vṛṣākapi: we twain will bring thee happiness.

Thou goest homeward on thy way along this path which leads to sleep. Supreme is Indra over all.

22 When, Indra and Vṛṣākapi, ye travelled upward to your home,

Where was that noisome beast, to whom went it, the beast that troubles man? Supreme is Indra over

all.

23 Daughter of Manu, Parsu bare a score of children at a birth. Her portion verily was bliss although her burthen caused her grief.

Translation Sāyaṇa/Wilson

10.086.01 Indra speaks: They have neglected the pressing of the Soma, they have not praised the divine Indra at the cherished (sacrifices), at which the noble Vṛṣākapi becoming my friend rejoiced; (still) I, Indra, am above all (the world). [Ma_dhavabhat.t.as ascribe the r.ca to Indra_n.i_ the wife of Indra, deprecating the preference given to Vṛṣākapi].

10.086.02 Indra_n.i_ speaks: You, Indra, much annoyed, hasten towards Vṛṣākapi; and yet you find no other place to drink the Soma; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.03 What (favour) has this tawny deer Vṛṣākapi done to you that you should like a liberal (benefactor) bestow upon him wealth and nourish me; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.04 This Vṛṣākapi whom you, Indra, cherish as your dear (son)-- may the dog which chases the boar (seize) him by the ear (and) devour him; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.05 The ape has spoiled the beloved ghi_-adorned (oblations) made to me (by worshippers); let me quickly cut off his head, let me not be the giver of happiness to one who works evil; Indra is above all (the world). [The ape: kapi = ape; also, a shorter form of Vr.s.a_kapi].

10.086.06 There is no woman more amiable than I am, not one who bears fairer sons than I; nor one more tractable not one more ardent; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.07 [Vṛṣākapi speaks]: O mother, who are easy of access, it will quickly be as (you have said); may my (father) and you, mother, be united; may it delight my (father) and your head like a bird; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.08 [Indra speaks]: You who have beautiful arms, who have beautiful fingers, long-haired, broad-hipped, why are you angry with our Vṛṣākapi, O you wife of a hero; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.09 [Indra_n.i_ speaks]: This savage beast (Vṛṣākapi) despises me as one who has no male (protector), and yet I am the mother of male offspring, the wife of Indra, the friend of the Maruts; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.10 The mother who is the institutress of the ceremony, the mother of male offspring, the wife of Indra, goes first to the united sacrifice to battle, (and) is honoured (by the praisers); Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.11 (Indra speaks]: I have heard that Indra_n.i_ is the most fortunate among these women, for her lord Indra, who is above all (the world), does ot die of old age like other (men).

10.086.12 I am not happy, Indra_n.i, without my friend Vṛṣākapi; whose acceptable oblation here, purified with water, proceeds to the gods; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.13 [Vṛṣākapi speaks]: O mother of Vṛṣākapi, wealthy, possessing excellent sons, possessing excellent daughters-in-law, let Indra eat your bulls, (give him) the beloved and most delightful ghi_, Indra is above all (the world). [Mother of Vṛṣākapi: Vṛṣākapayin = wife of Indra; Vṛṣākapi may be a name of Indra, as the showerer of benefits].

10.086.14 [Indra speaks]: The worshippers dress for me fifteen (and) twenty bulls; I eat them and (become) fat, they fill both sides of my belly; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.15 [Indra_n.i_ speaks]: Like a sharp-horned bull roaring among the herds, so may your libation please your heart, Indra, (your libation) which she who desires to please you is expressing for you; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.16 The man who is impotent begets not progeny, but he who is endowed with vigour; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.17 [Indra speaks]: He who is endowed with vigour begets not progeny, but he who is impotent; Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.18 [Indra_n.i_ speaks]: Let this Vṛṣākapi, Indra, take a dead wild ass, (let him take) a knife (to cut it up), a fire-place (to cook it), a new saucepan, and a cart full of fuel; Indra is above all (the world). [A dead wild ass: parasvantam = parasvam, i.e. one who is of his own nature, i.e. an ape, kapi; a fire place: su_na_; cf. Manu 3.68].

10.086.19 [Indra speaks]: Here I come to the (sacrifice) looking upon (the worshippers), distinguishing the Da_sa and the A_rya; I drink (the Soma) of the (worshipper), who effuses (the Soma) with mature (mind); I look upon the intelligent (sacrificer); Indra is above all (the world). [cf. Muir, Sanskrit Texts, vol. 2, p. 374].

10.086.20 Go home, Vṛṣākapi, to the halls of sacrifice (from the lurking-place of the enemy), which is desert and forest (how many leagues are there from there?) and from the nearest (lurking-place); Indra is above all (the world).

10.086.21 Come back, Vṛṣākapi, that we may do what is agreeable to you; you, who are the destroyer of sleep, come home again by the road; Indra is above all (the world). [Destroyer of sleep: i.e., the sun; cf. Nirukta 12.28].

10.086.22 Rise up and come home, Vṛṣākapi and Indra; where is that destructive beast, to what (region) has (that beast), the exhilarator of men, gone? Indra is above all (the world). [To what region: Nirukta, 13.3].

10.086.23 The daughter of Manu, Pars'u by name, bore twenty children at once; may good fortune, O arrow of Indra, befall her whose belly was so prolific; Indra is above all (the world). [Indra is the deity invoked: Nirukta 13.3].

Anser indicus. haṁsá

Anser indicus. haṁsá

Railing post with a lotus rhizome. Allahabad Museum. Stone. Bharhut, Madhya Pradesh.Shunga. c. 2nd cent. BCE. 43x58x25 cm. Pillar shows in the middle a lotus flower. A border of palmettes on each bevelled side. A small fragment later joined to it.

Railing post with a lotus rhizome. Allahabad Museum. Stone. Bharhut, Madhya Pradesh.Shunga. c. 2nd cent. BCE. 43x58x25 cm. Pillar shows in the middle a lotus flower. A border of palmettes on each bevelled side. A small fragment later joined to it.

Crucible steel button.

Crucible steel button.

Figurine of zebu, humped bull discovered in Binjor 4MSR

Figurine of zebu, humped bull discovered in Binjor 4MSR

Focus on bos indicus aurochs + water flowing out of muzzle.

Focus on bos indicus aurochs + water flowing out of muzzle.

kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Phonetic determinative)

kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' (Phonetic determinative)

A Black drongo in Rajasthan state, northern India

A Black drongo in Rajasthan state, northern India A pair of black drongo birds are perched on the Daimabad bronze chariot flanking the charioter

A pair of black drongo birds are perched on the Daimabad bronze chariot flanking the charioter

Gate on Nahalmishmar crown:

Gate on Nahalmishmar crown:

Drawing of the animals carved on the cylinder seal found at Konar Sandal South.

Drawing of the animals carved on the cylinder seal found at Konar Sandal South. Jiroft. Vase. Basket-shaped wallet.

Jiroft. Vase. Basket-shaped wallet.

Stairs of Konar Sandal Ziggurat The main part of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat of the Jiroft ancient site, located in the southern Iranian province of Kerman, has recently been excavated, the Persian service of CHN reported on Friday.

Stairs of Konar Sandal Ziggurat The main part of the Konar Sandal Ziggurat of the Jiroft ancient site, located in the southern Iranian province of Kerman, has recently been excavated, the Persian service of CHN reported on Friday.

The seal does NOT have any 'signs' but only a composite animal pictogram with three animal heads joined together to a bovine body. Any decipherment should also read such messages [using the sounds of language(s) of the scribe] as shown on this seal, because the seal without any 'signs' does convey some information about some product(s) traded. Any analysis of 'statistical signatures' should also cover such 'pictograms or pictorial motifs' and should not be restricted only to 'signs' treating the 'signs' alone as texts messages and ignoring the sounds conveyed by the pictograms or pictorial motifs.

The seal does NOT have any 'signs' but only a composite animal pictogram with three animal heads joined together to a bovine body. Any decipherment should also read such messages [using the sounds of language(s) of the scribe] as shown on this seal, because the seal without any 'signs' does convey some information about some product(s) traded. Any analysis of 'statistical signatures' should also cover such 'pictograms or pictorial motifs' and should not be restricted only to 'signs' treating the 'signs' alone as texts messages and ignoring the sounds conveyed by the pictograms or pictorial motifs.

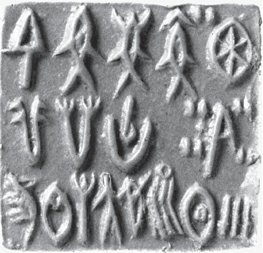

m0314 Seal impression, Text 1400 Dimension: 1.4 sq. in. (3.6 cm)

m0314 Seal impression, Text 1400 Dimension: 1.4 sq. in. (3.6 cm)  The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is

The last sign is wrongly identified in Mahadevan concordance. This hieroglyph is  eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop.

eraka 'nave of wheel' rebus: eraka 'moltencast, copper' PLUS sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop'. Thus, moltencast copper workshop.

h419

h419

Description

Description