https://tinyurl.com/y8arm7gh

The continuum is evidenced by: 1. Cunda, kammāraputta, son of the village smith, metalworker who served the last meal to the Buddha. 2. Anathapindika covers Jetavana with gold coins.

Epigraphia Indus Script -- Hypertexts and Meanings (3 vols.) posits that the entire set of over 8000 inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora are wealth accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues.

![]()

![]()

Indications of the wealth achieved by ancient India through metalwork from 4th millennium BCE is exemplified by two episodes in the Buddha's life:

1. Cunda metalworker who offers the last meal to the Buddha and

2. Anāthapiṇḍika who covers the Jetavana monastery with gold coins

Thanks to Prof. Shrinivas Tilak who reminds me that Cunda, who served 'the last meal to the Buddha,' was a metal worker (kammāraputta) living in Pava where the Buddha had reached on his way to Kusinārā. He stayed in Cunda’s Mango grove.

Kammāraputta (in Sanskrit, Karmāraputra) means son of the smith.

![Cunda prepares Pork.jpg]()

Cunda preparing pork, Wat Kasatrathiraj, Ayutthaya

In the Cunda Kammāraputta Sutta, Gautama Buddha stays at Cunda's mango grove and they talk about rites of purification. Cunda declares that he approves of the rites of the brahmins of the West and the Buddha mentions that the rites of purification of these brahmins and the purification in the discipline of the noble ones is quite different. Cunda asks him to explain how there is purification in his discipline, and so the Buddha teaches him the ten courses of skillful action. Cunda praises him for his teachings and declares himself a lay follower from that day on.

The continuum is evidenced by: 1. Cunda, kammāraputta, son of the village smith, metalworker who served the last meal to the Buddha. 2. Anathapindika covers Jetavana with gold coins.

Epigraphia Indus Script -- Hypertexts and Meanings (3 vols.) posits that the entire set of over 8000 inscriptions of Indus Script Corpora are wealth accounting ledgers, metalwork catalogues.

Indications of the wealth achieved by ancient India through metalwork from 4th millennium BCE is exemplified by two episodes in the Buddha's life:

1. Cunda metalworker who offers the last meal to the Buddha and

2. Anāthapiṇḍika who covers the Jetavana monastery with gold coins

Thanks to Prof. Shrinivas Tilak who reminds me that Cunda, who served 'the last meal to the Buddha,' was a metal worker (kammāraputta) living in Pava where the Buddha had reached on his way to Kusinārā. He stayed in Cunda’s Mango grove.

Kammāraputta (in Sanskrit, Karmāraputra) means son of the smith.

Cunda preparing pork, Wat Kasatrathiraj, Ayutthaya

In the Cunda Kammāraputta Sutta, Gautama Buddha stays at Cunda's mango grove and they talk about rites of purification. Cunda declares that he approves of the rites of the brahmins of the West and the Buddha mentions that the rites of purification of these brahmins and the purification in the discipline of the noble ones is quite different. Cunda asks him to explain how there is purification in his discipline, and so the Buddha teaches him the ten courses of skillful action. Cunda praises him for his teachings and declares himself a lay follower from that day on.

Sūkaramaddava, is translated differently depending on the buddhist tradition. Since the word is composed by sūkara, which means pig, and maddava, which means soft, tender, delicate, two alternatives are possible:

- Tender pig or boar meat.

- What is enjoyed by pigs and boars.

The Buddha's Last Meal

When the Buddha and his disciples arrived at Pava, the son of the village goldsmith, whose name was Cunda, invited the party to a meal called sukaramaddava, or "boar's delight". Some scholars believe it was a special delicious dish of mushrooms, while others believe it to be a dish of wild boar's flesh.The Buddha advised Cunda to serve him only with the sukaramaddava that he had prepared. The other food that Cunda had prepared could be served to the other monks. After the meals were served Buddha told Cunda, "Cunda, if any sukaramaddava is left over, bury it in a hole. I do not see anyone in the world other than the Blessed One who could digest the food if he ate it."

"So be it, Lord," Cunda replied, and buried the leftovers in the ground. He went to the Buddha and, after paying homage to him, sat down at one side. Then the Buddha taught him the Dharma. The Buddha also praised Cunda for the meal that had refreshed and strengthened him after his journey. But soon after this, the Buddha suffered from an attack of the dysentery he had been suffering from earlier and sharp pains came upon him. By an effort of will he was able to bear the pain. Though extremely weak the Buddha decided to continue on immediately to Kusinaga, a little more than six miles away. After a painful struggle, he reached a grove of sala trees just outside the town.

The Buddha took his last bath in the Kakuttha river. After resting a while, he said, "Now it may happen that some people may make Cunda regret having given me the meal that made me sick. Ananda, if this should happen, you should tell Cunda that you have heard directly from the Buddha that it was a gain for him. Tell him that two offerings to the Buddha are of equal gain; the offering of food just before his supreme enlightenment and the offering of food just before he passes away. This is the final birth of the Buddha."

Then he said, "Ananda, please make a couch ready for me with its head to the North between two big sala trees. I am tired and I want to lie down."

Now, on that occasion, those two sala trees were covered with blossoms through the influence of the devas, though it was not the season. They scattered and sprinkled the Buddha with the falling blossoms, as though out of respect for him. Then the Buddha said to Venerable Ananda, "Ananda, the two big sala trees are scattering flowers on me as though they are paying their respects to me. But this is not how I should be respected and honoured. Rather, it is the monks or nuns, or the men or woman lay followers, who live according to my teaching, that should respect and honour me."

A little while later it was noticed that Venerable Ananda was nowhere to be seen. He had gone inside a hut and stood leaning against the door bar, weeping. He thought: "Alas! I remain still but a learner, one who has yet to work out his own perfection. And the Master is about to pass away from me — he who is so kind!"

And the Buddha, sending for Ananda, said to him, "Enough now, Ananda! Do not sorrow and cry. Have I not already repeatedly told you that there is separation and parting from all that is dear and beloved? How is it possible that anything that has been born, has had a beginning, should not again die? Such a thing is not possible.

"Ananda, you have served me with your acts of loving-kindness, helpfully, gladly, sincerely, and so too in your words and your thoughts. You have gained merit, Ananda. Keep on trying and you will soon be free of all your human weaknesses. In a very short time you too will become an arahant.

"Now you can go, Ananda. But go into Kusinaga and tell all the people that tonight, in the last watch of the night, the Buddha will pass away into nirvana. Come and see the Buddha before he passes away."

So Venerable Ananda, taking with him another monk, did as the Buddha bid him and went to Kusinaga to tell the people. When they heard the news, they were much grieved. And all the people of Kusinaga, men, women and children came to the two big sala trees to bid a last farewell to the Buddha. Family by family, they bowed low down before him and so bade him farewell.

There are four places for faithful followers to see their inspiration. These are four holy places made sacred by their association with the Buddha. They are:

1. The Buddha's birth place (Lumbini)

2. The place where the Buddha attained enlightenment (Bodh Gaya)

3. The place where the Buddha gave his first teachings and set in motion the Wheel of the Dharma or Truth (Sarnath)

4. The place where the Buddha attained parinibbana, or final liberation (Kusinaga).

https://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhism/lifebuddha/2_29lbud.htm

Anathapindika (Pāli: Anāthapiṇḍika; Sanskrit: Anāthapiṇḍada) was a wealthy merchant and banker, believed to have been the wealthiest merchant in Savatthi in the time of Gautama Buddha. Anathapindika is frequently referred to as Anathapindika-setthi (setthi meaning "wealthy person" or "millionaire"), and is sometimes referred to as Mahā Anāthapindika to distinguish him from Cūla Anāthapindika, another disciple of the Buddha.

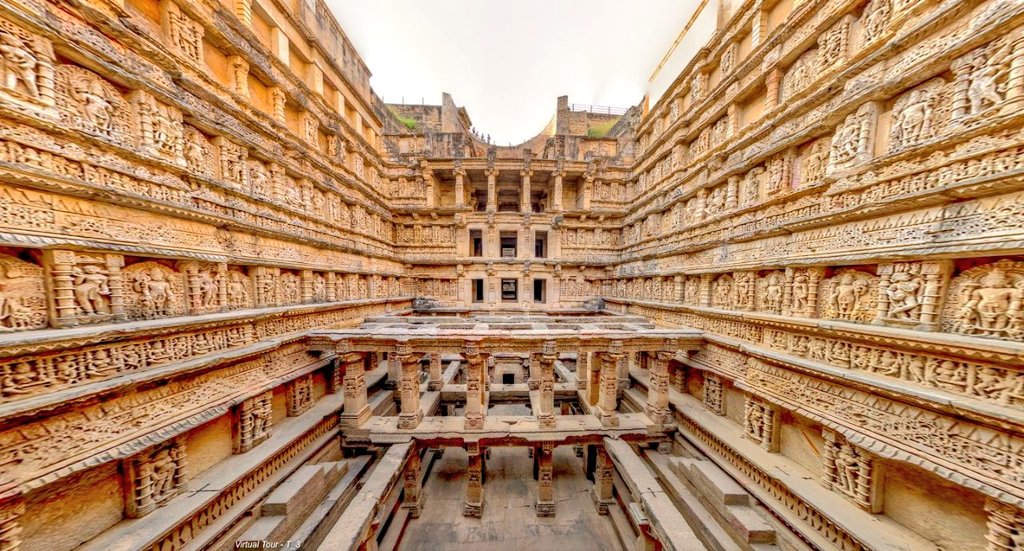

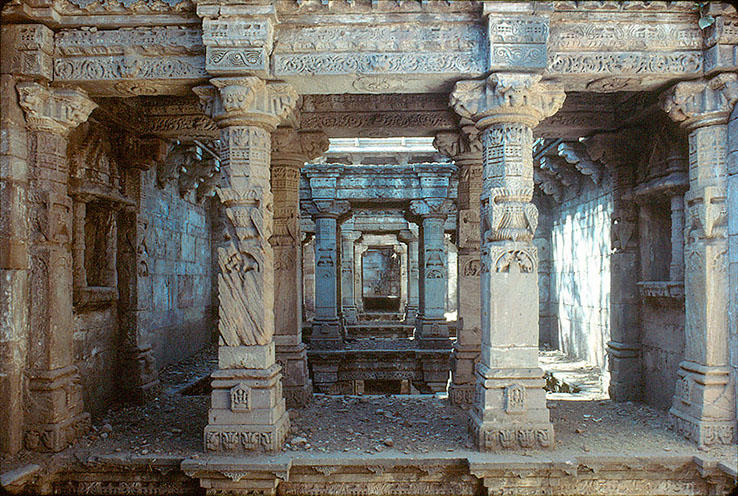

![]()

![Image result for bharhut anathapindika]()

Anathapindika covers Jetavana with coins (Bharhut, Brahmi text: jetavana ananthapindiko deti kotisanthatena keta

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anathapindika

"So be it, Lord," Cunda replied, and buried the leftovers in the ground. He went to the Buddha and, after paying homage to him, sat down at one side. Then the Buddha taught him the Dharma. The Buddha also praised Cunda for the meal that had refreshed and strengthened him after his journey. But soon after this, the Buddha suffered from an attack of the dysentery he had been suffering from earlier and sharp pains came upon him. By an effort of will he was able to bear the pain. Though extremely weak the Buddha decided to continue on immediately to Kusinaga, a little more than six miles away. After a painful struggle, he reached a grove of sala trees just outside the town.

The Buddha took his last bath in the Kakuttha river. After resting a while, he said, "Now it may happen that some people may make Cunda regret having given me the meal that made me sick. Ananda, if this should happen, you should tell Cunda that you have heard directly from the Buddha that it was a gain for him. Tell him that two offerings to the Buddha are of equal gain; the offering of food just before his supreme enlightenment and the offering of food just before he passes away. This is the final birth of the Buddha."

Then he said, "Ananda, please make a couch ready for me with its head to the North between two big sala trees. I am tired and I want to lie down."

Now, on that occasion, those two sala trees were covered with blossoms through the influence of the devas, though it was not the season. They scattered and sprinkled the Buddha with the falling blossoms, as though out of respect for him. Then the Buddha said to Venerable Ananda, "Ananda, the two big sala trees are scattering flowers on me as though they are paying their respects to me. But this is not how I should be respected and honoured. Rather, it is the monks or nuns, or the men or woman lay followers, who live according to my teaching, that should respect and honour me."

A little while later it was noticed that Venerable Ananda was nowhere to be seen. He had gone inside a hut and stood leaning against the door bar, weeping. He thought: "Alas! I remain still but a learner, one who has yet to work out his own perfection. And the Master is about to pass away from me — he who is so kind!"

And the Buddha, sending for Ananda, said to him, "Enough now, Ananda! Do not sorrow and cry. Have I not already repeatedly told you that there is separation and parting from all that is dear and beloved? How is it possible that anything that has been born, has had a beginning, should not again die? Such a thing is not possible.

"Ananda, you have served me with your acts of loving-kindness, helpfully, gladly, sincerely, and so too in your words and your thoughts. You have gained merit, Ananda. Keep on trying and you will soon be free of all your human weaknesses. In a very short time you too will become an arahant.

"Now you can go, Ananda. But go into Kusinaga and tell all the people that tonight, in the last watch of the night, the Buddha will pass away into nirvana. Come and see the Buddha before he passes away."

So Venerable Ananda, taking with him another monk, did as the Buddha bid him and went to Kusinaga to tell the people. When they heard the news, they were much grieved. And all the people of Kusinaga, men, women and children came to the two big sala trees to bid a last farewell to the Buddha. Family by family, they bowed low down before him and so bade him farewell.

There are four places for faithful followers to see their inspiration. These are four holy places made sacred by their association with the Buddha. They are:

1. The Buddha's birth place (Lumbini)

2. The place where the Buddha attained enlightenment (Bodh Gaya)

3. The place where the Buddha gave his first teachings and set in motion the Wheel of the Dharma or Truth (Sarnath)

4. The place where the Buddha attained parinibbana, or final liberation (Kusinaga).

https://www.buddhanet.net/e-learning/buddhism/lifebuddha/2_29lbud.htm

Anathapindika (Pāli: Anāthapiṇḍika; Sanskrit: Anāthapiṇḍada) was a wealthy merchant and banker, believed to have been the wealthiest merchant in Savatthi in the time of Gautama Buddha. Anathapindika is frequently referred to as Anathapindika-setthi (setthi meaning "wealthy person" or "millionaire"), and is sometimes referred to as Mahā Anāthapindika to distinguish him from Cūla Anāthapindika, another disciple of the Buddha.

Anathapindika covers Jetavana with coins (Bharhut, Brahmi text: jetavana ananthapindiko deti kotisanthatena keta

Building Jetavana Monastery

Following Anathapindika's first encounter with the Buddha, he requested to offer him a meal, which the Buddha accepted, and then asked to build a temple for him and his monks in his hometown of Savatthi, to which the Buddha agreed.[3]

Shortly after, Anathapindika went back to Savatthi to search for a place to build the monastery. Looking for a place that was both accessible to followers and peacefully secluded, he came across a park belonging to Prince Jeta, the son of King Pasenadi of Kosala. Anathapindika offered to buy the park from the prince but the prince refused, after Anathapindika persisted, the prince joking said he will sell him the park if he covers it with gold coins, to which Anathapindika agreed.[4][6]

Anathapindika later came back with wagons full of gold pieces to cover the park with. When Prince Jeta stated he was merely joking, Anathapindika and the prince went to arbitrators who concluded that Prince Jeta had to sell the park at the agreed price. After seeing Anathapindika's resolve, Prince Jeta offered to build a wall and gate for the monastery. Afterwards, Anathapindika spent several million more gold pieces building the temple and its furnishings, in what would come to be known as the Jetavana Monastery, also often referred to in Buddhist scriptures as "Anathapindika's Monastery"https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Anathapindika

Anathapindika's Offering

THE Master was in Rajagriha when a rich merchant named Anathapindika arrived from Cravasti. Anathapindika was a religious man, and when he heard that a Buddha was living in the Bamboo Grove, he was eager to see him.

He set out one morning, and as he entered the Grove, a divine voice led him to where the Master was seated. He was greeted with words of kindness; he presented the community with a magnificent gift, and the Master promised to visit him in Cravasti.

When he returned home, Anathapindika began to wonder where he could receive the Blessed One. His gardens did not seem worthy of such a guest. The most beautiful park in the city belonged to Prince Jeta, and Anathapindika decided to buy it.

"I will sell the park," Jeta said to him, "if you cover the ground with gold coins."

Anathapindika accepted the terms. He had chariot-loads of gold coins carried to the park, and presently only a small strip of ground remained uncovered. Then Jeta joyfully exclaimed:

"The park is yours, merchant; I will gladly give you the strip that is still uncovered."

Anathapindika had the park made ready for the Master; then he sent his most faithful servant to the Bamboo Grove, to inform him that he was now prepared to receive him in Cravasti.

"O Venerable One," said the messenger, "my master falls at your feet. He hopes you have been spared anxiety and sickness, and that you are not loath to keep the promise you made to him. You are awaited in Cravasti, O Venerable One."

The Blessed One had not forgotten the promise he had made to the merchant Anathapindika; he wished to abide by it, and he said to the messenger, "I will go."

He allowed a few days to pass; then he took his cloak and his alms-bowl, and followed by a great number of disciples, he set out for Cravasti. The messenger went ahead, to tell the merchant he was coming.

Anathapindika decided to go and meet the Master. His wife, his son and his daughter accompanied him, and they were attended by the wealthiest inhabitants of the city. And when they saw the Buddha, they were dazzled by his splendor; he seemed to be walking on a path of molten gold.

They escorted him to Jeta's park, and Anathapindika said to him:

"My Lord, what shall I do with this park?""Give it to the community, now and for all time," replied the Master.

Anathapindika ordered a servant to bring him a golden bowl full of water. He poured the water over the Master's hands, and he said:

"I give this park to the community, ruled by the Buddha, now and for all time."

"Good!" said the Master. "I accept the gift. This park will be a happy refuge; here we shall live in peace, and find shelter from the heat and from the cold. No vicious animals enter here: not even the humming of a mosquito disturbs the silence; and here there is protection from the rain, the biting wind and the ardent sun. And this park will inspire dreams, for here we shall meditate hour after hour. It is only right that such gifts be made to the community. The intelligent man, the man who does not neglect his own interests, should give the monks a proper home; he should give them food and drink; he should give them clothes. The monks, in return, will teach him the law, and he who knows the law is delivered from evil and attains nirvana."

The Buddha and his disciples established themselves in Jeta's park, Anathapindika was happy; but, one day, a solemn thought occurred to him.

"I am being loudly praised," he said to himself, "and yet what is so admirable about my actions? I present gifts to the Buddha and to the monks, and for this I am entitled to a future reward; but my virtue benefits me alone! I must get others to share in the privilege. I shall go through the streets of the city, and from those whom I meet, I shall get donations for the Buddha and for the monks. Many will thus participate in the good I shall be doing."

He went to Prasenajit, king of Cravasti, who was a wise and upright man. He told him what he had decided to do, and the king approved. A herald was sent through the city with this royal proclamation:

"Listen well, inhabitants of Cravasti! Seven days from this day, the merchant Anathapindika, riding an elephant, will go through the streets of the city. He will ask all of you for alms, which he will then offer to the Buddha and to his disciples. Let each one of you give him whatever he can afford."

On the day announced, Anathapindika mounted his finest elephant and rode through the streets, asking every one for donations for the Master and for the community. They crowded around him: this one gave gold, that one silver; one woman took off her necklace, another her bracelet, a third an anklet; and even the humblest gifts were accepted.

Now, there lived in Cravasti a young girl who was extremely poor. It had taken her three months to save enough money to buy a piece of coarse material, out of which she had just made a dress for herself. She saw Anathapindika with a great crowd around him.

"The merchant Anathapindika appears to be begging," she said to a bystander.

"Yes, he is begging," was the reply.

"But he is said to be the richest man in Cravasti. Why should he be begging?"

"Did you not hear the royal proclamation being cried through the streets, seven days ago?"

"No."

"Anathapindika is not collecting alms for himself. He wants every one to participate in the good he is doing, and he is asking for donations for the Buddha and his disciples. All those who give will be entitled to a future reward."

The young girl said to herself, "I have never done anything deserving of praise. It would be wonderful to make an offering to the Buddha. But I am poor. What have I to give?" She walked away, wistfully. She looked at her new dress. "I have only this dress to offer him. But I can not go through the streets naked."

She went home and took off the dress. Then she sat at the window and watched for Anathapindika, and when he passed in front of her house, she threw the dress to him. He took it and showed it to his servants.

"The woman who threw this dress to me," said he, "probably had nothing else to offer. She must be naked, if she had to remain at home and give alms in this strange manner. Go; try to find her and see who she is."

The servants had some difficulty finding the young girl. At last they saw her, and they learned that their master had been correct in his surmise: the dress thrown out of the window was the poor child's entire fortune. Anathapindika was deeply moved; he ordered his servants to bring many costly, beautiful clothes, and he gave them to this pious maiden who had offered him her simple dress.

She died the following day and was reborn a Goddess in Indra's sky. But she never forgot how she had come to deserve such a reward, and, one night, she came down to earth and went to the Buddha, and he instructed her in the holy law.

m1356 Copper plate. The endless knot and svastika

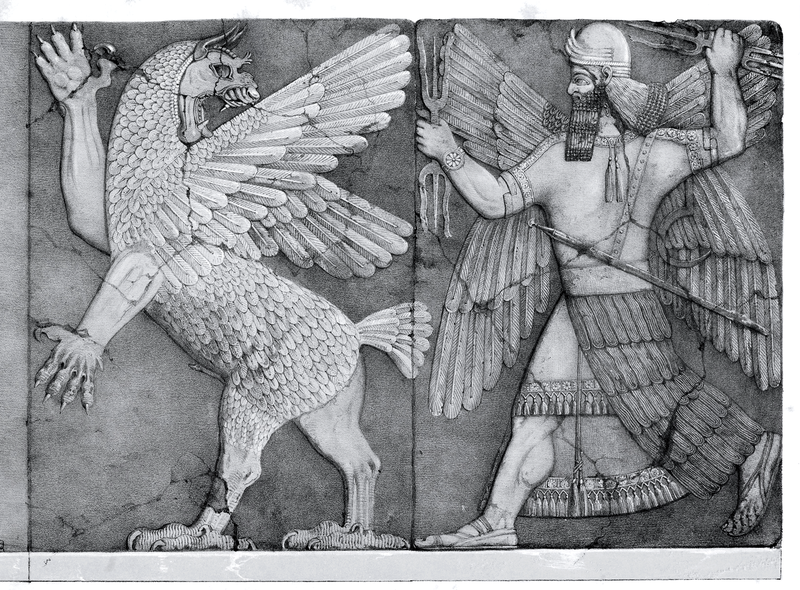

m1356 Copper plate. The endless knot and svastika The shaft-hole axhead is conclusive proof of the Indus Script hypertext signified by the double-headed eagle ligatured to the body of a standing human, with wingsemerging from his shoulders. This hypertext is accompanied with two other hypertexts: winged tiger with feline paws and boar. All three Indus Script hypertexts are read rebus: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS śyēná m. ʻ hawk, falcon, eagle ʼ RV.Pa. sēna -- , °aka -- m. ʻ hawk ʼ, Pk. sēṇa -- m.; WPah.bhad. śeṇ ʻ kite ʼ; A. xen ʻ falcon, hawk ʼ, Or. seṇā, H. sen, sẽ m., M. śen m., śenī f. (< MIA. *senna -- ); Si. sen ʻ falcon, eagle, kite ʼ.(CDIAL 12674) Rebus:

The shaft-hole axhead is conclusive proof of the Indus Script hypertext signified by the double-headed eagle ligatured to the body of a standing human, with wingsemerging from his shoulders. This hypertext is accompanied with two other hypertexts: winged tiger with feline paws and boar. All three Indus Script hypertexts are read rebus: dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS śyēná m. ʻ hawk, falcon, eagle ʼ RV.Pa. sēna -- , °aka -- m. ʻ hawk ʼ, Pk. sēṇa -- m.; WPah.bhad. śeṇ ʻ kite ʼ; A. xen ʻ falcon, hawk ʼ, Or. seṇā, H. sen, sẽ m., M. śen m., śenī f. (< MIA. *senna -- ); Si. sen ʻ falcon, eagle, kite ʼ.(CDIAL 12674) Rebus:

.jpg)

Ancient Greek tetradrachm coin from Akragas, 410 BCE, with a grasshopper on the right.

Ancient Greek tetradrachm coin from Akragas, 410 BCE, with a grasshopper on the right.

[quote]

[quote]

The pedestal signifies hamsa with a garland held in its beak and an adorant with a garland in his hand. Hamsa is cognate with hansa, guild.

The pedestal signifies hamsa with a garland held in its beak and an adorant with a garland in his hand. Hamsa is cognate with hansa, guild.

*

*

K(C)ernunnos is shown seated in penance (comparable to the sitting posture of the seated person on the Mohenjo-daro seal m0304).

K(C)ernunnos is shown seated in penance (comparable to the sitting posture of the seated person on the Mohenjo-daro seal m0304).

"

" (Mac Cana, page 35)

(Mac Cana, page 35) Plate B "This plate shows an antithetical arrangement of animals around a bust of a goddess. The goddess is presented in the center with a six-spoked rosette wheel on either side of her. She is flanked by two elephants confronting each other. Below them are two griffins arranged in the same antithetical manner and a hound is placed in the lower center of the plate, between these two griffins. The goddess seems almost identical with the goddess on

Plate B "This plate shows an antithetical arrangement of animals around a bust of a goddess. The goddess is presented in the center with a six-spoked rosette wheel on either side of her. She is flanked by two elephants confronting each other. Below them are two griffins arranged in the same antithetical manner and a hound is placed in the lower center of the plate, between these two griffins. The goddess seems almost identical with the goddess on  Plate C "This plate shows an intriguing iconography of two deities with a broken wheel: in the center of the plate, a bust of a bearded deity is depicted with a half-shaped wheel on his right side and a full-length leaping figure is holding the rim of the wheel from the right. Under this leaping figure, a horned serpent is presented. The rest of animals are placed clockwise around this group of two deities: in the upper part of the plate, two identical beasts are depicted on either side of the group, both facing the left side of the deities and in the lower part, three griffins are depicted in parallel, all facing the right side of the deities. The space between the upper and lower group of the animals is filled with some botanical patterns which are usually identified as ivy tendrils.

Plate C "This plate shows an intriguing iconography of two deities with a broken wheel: in the center of the plate, a bust of a bearded deity is depicted with a half-shaped wheel on his right side and a full-length leaping figure is holding the rim of the wheel from the right. Under this leaping figure, a horned serpent is presented. The rest of animals are placed clockwise around this group of two deities: in the upper part of the plate, two identical beasts are depicted on either side of the group, both facing the left side of the deities and in the lower part, three griffins are depicted in parallel, all facing the right side of the deities. The space between the upper and lower group of the animals is filled with some botanical patterns which are usually identified as ivy tendrils. Plate D "On the lower right side of each bull, a man is standing in the posture of attacking the bull with a sword. Under the feet of each bull, by the side of each man, a dog is depicted as running toward the left while a cat-like creature is running in the same direction over the back of the bull. These cats as well as the dogs have the same hanging feet. As shown in other plates, the spaces between each figure are filled with tear-drop shaped leaves."

Plate D "On the lower right side of each bull, a man is standing in the posture of attacking the bull with a sword. Under the feet of each bull, by the side of each man, a dog is depicted as running toward the left while a cat-like creature is running in the same direction over the back of the bull. These cats as well as the dogs have the same hanging feet. As shown in other plates, the spaces between each figure are filled with tear-drop shaped leaves."

Outer plate a "On plate (a), a bearded god holds a small man in each hand over his shoulders. He is in so-called "orans position"with his arms raised. Like another male god on

Outer plate a "On plate (a), a bearded god holds a small man in each hand over his shoulders. He is in so-called "orans position"with his arms raised. Like another male god on  Outer plate b "Plate (b) shows a male deity holding two sea horses or dragons. These two animals have the mixed characters of horse and dragon; they have a long, serpentine body of a dragon and a horse-like head and two front legs. Their ribs are prominently fluted and the tails and wings are swirled. Below the god is a double-headed monster attacking small figures of fallen men...as early as 1913, Hubert suggested that this scene should be related to the sea or water since the god holds the sea horses. "

Outer plate b "Plate (b) shows a male deity holding two sea horses or dragons. These two animals have the mixed characters of horse and dragon; they have a long, serpentine body of a dragon and a horse-like head and two front legs. Their ribs are prominently fluted and the tails and wings are swirled. Below the god is a double-headed monster attacking small figures of fallen men...as early as 1913, Hubert suggested that this scene should be related to the sea or water since the god holds the sea horses. " Outer plate c '"This plates shows a deity with his upraised hands in "orans position" as the other male gods on the outer plates. However, unlike the others, his hands are empty. He has a boxing man at his right and on the left is a leaping figure with a small horse rider below it. The leaping figure is similar to the one on the

Outer plate c '"This plates shows a deity with his upraised hands in "orans position" as the other male gods on the outer plates. However, unlike the others, his hands are empty. He has a boxing man at his right and on the left is a leaping figure with a small horse rider below it. The leaping figure is similar to the one on the  Outer plate d "The iconographic details of this plate are comparatively clear: a bearded god is holding two stags in each hand. Stylistically, this plate share some characteristics with the

Outer plate d "The iconographic details of this plate are comparatively clear: a bearded god is holding two stags in each hand. Stylistically, this plate share some characteristics with the  Outer plate e "Plate (e) shows a bust of a goddess in the center and the smaller busts of two male gods on her shoulders. She wears a torque and has a typical mask-like face with her small mouth and T-shaped eye brows and nose. The bearded deity on her right shoulder is almost identical with the central god on the inner

Outer plate e "Plate (e) shows a bust of a goddess in the center and the smaller busts of two male gods on her shoulders. She wears a torque and has a typical mask-like face with her small mouth and T-shaped eye brows and nose. The bearded deity on her right shoulder is almost identical with the central god on the inner  Outer plate f "Plate (f) shows an interesting iconography. The central goddess holds a small bird in her upraised right hand while her left arm is placed across her chest. Crossed over her left arm is lying a small man and on the opposite side to the man is a dog upside down. Some have suggested that the goddess is cradling the two figures on her chest. But this would hardly be the case because the figures are depicted as fallen rather than cradled.(Davison: 498) The goddess has two birds of prey - which may be eagles or ravens - on either side of her head. On her right shoulder is seated a small female figure, over whose head is a lion-like animal runs. On the left side, another small figure is holding the hair of the goddess as if plaiting her hair. Olmsted notes that the small bird in her right hand is same as that on the helmet on

Outer plate f "Plate (f) shows an interesting iconography. The central goddess holds a small bird in her upraised right hand while her left arm is placed across her chest. Crossed over her left arm is lying a small man and on the opposite side to the man is a dog upside down. Some have suggested that the goddess is cradling the two figures on her chest. But this would hardly be the case because the figures are depicted as fallen rather than cradled.(Davison: 498) The goddess has two birds of prey - which may be eagles or ravens - on either side of her head. On her right shoulder is seated a small female figure, over whose head is a lion-like animal runs. On the left side, another small figure is holding the hair of the goddess as if plaiting her hair. Olmsted notes that the small bird in her right hand is same as that on the helmet on  Outer plate g ".The goddess is crossing her arms on the chest. On her right shoulder is a man struggling with a lion and on the left is a leaping figure who is almost identical with the one on

Outer plate g ".The goddess is crossing her arms on the chest. On her right shoulder is a man struggling with a lion and on the left is a leaping figure who is almost identical with the one on

Two decorated bases and a lingam, Mohenjodaro.

Two decorated bases and a lingam, Mohenjodaro.  Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994.

Tre-foil inlay decorated base (for linga icon?); smoothed, polished pedestal of dark red stone; National Museum of Pakistan, Karachi; After Mackay 1938: I, 411; II, pl. 107:35; Parpola, 1994.

North Jutlandic Island

North Jutlandic Island

Rakhigarhi project 2012 15

Rakhigarhi project 2012 15

.jpg?1372283917)

.jpg?1372341437)

.jpg?1372284540)

https://www.navaratnarajaram.com

8 Hours ago