Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/llvrtwuhttps://www.facebook.com/srini.kalyanaraman/posts/10156238542274625

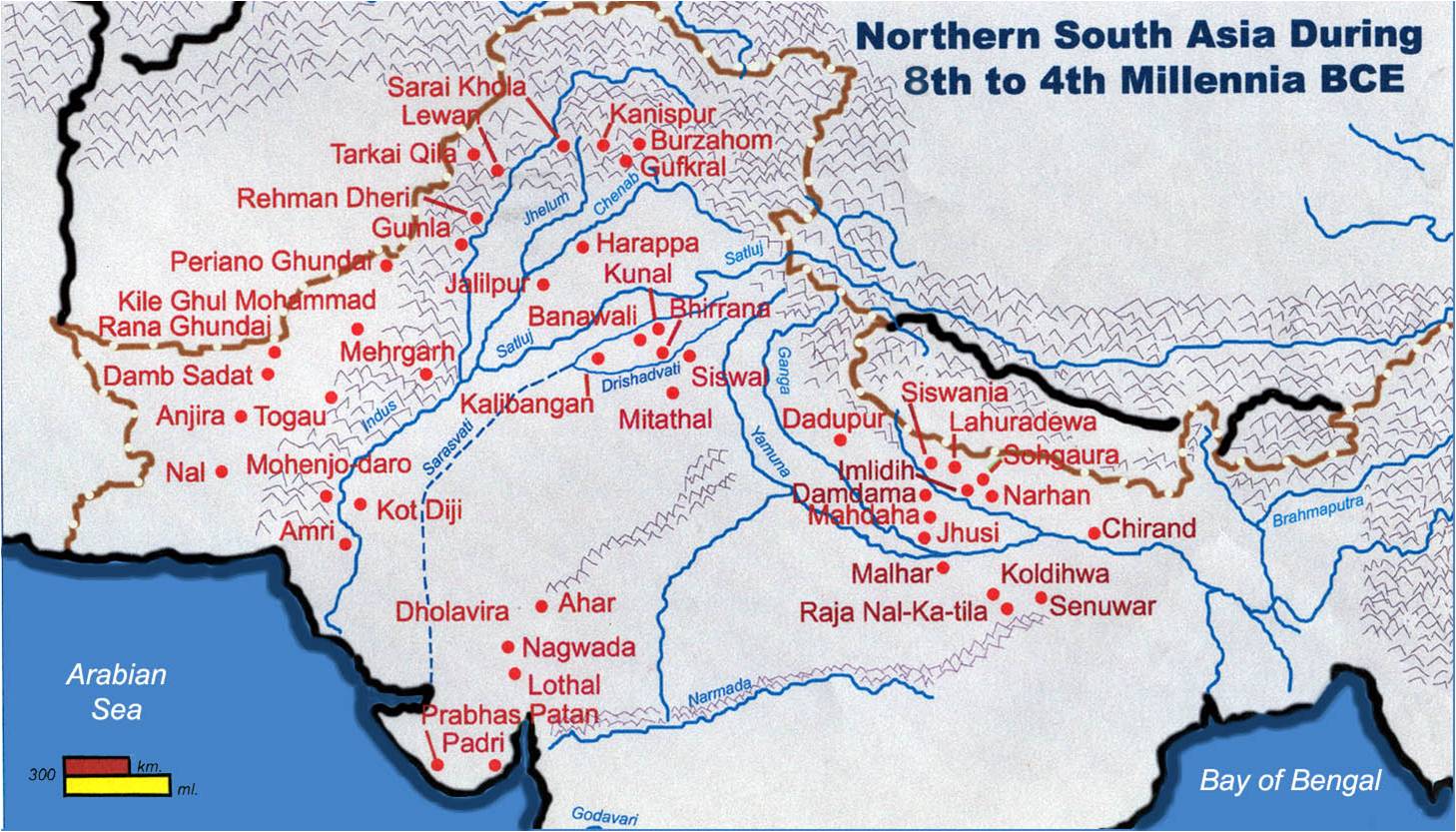

This monograph is a continuation of "Tridhātu as Gaṇeśa, Tridhātu on Indus Script metalwork for crucible steel, ādhyātmikā metaphor pr̥thvyaptejorūpadhātu (R̥gveda)" presentedin http://tinyurl.com/kptlbz3 to evidence the Veda culture continuum in Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization.

Meluhha Indus Script cipher signifiers are hieroglyphs which build up a hypertext to render artha, 'purpose, business, meaning'. This signification is achieved using Meluhha words and rebus expressions.

A good example of a hypertext is the 'priest' statue discovered in Mohenjo-daro.

This monograph demonstrates that the hieroglyph/hypertext expressions on the statuette signify in Meluhha Indus Script cipher (mlecchita vikalpa), the words: Potr̥ 'purifier priest'; dhatu 'mineral ores’; and dhāvaḍ 'smelter'. These hypertexts sculpted on the statuette of 'priest' of Mohenjo-daro are elucidated.

The hypertext expression of the statue is composed of the following hieroglyphs: 1. A dotted circle on a fillet worn as a strand on the forehead; 2. a shawl worn leaving right-shoulder bare; 3. the shawl is decorated with trefoil hieroglyphs (combination of three dotted circle hieroglyphs). Each of these hypertexts is a Meluhha cipher expression related to smelting work, metalwork.

![]() The uttarIyam worn by the Priest is potta -- , °taga -- , °tia -- n. ʻ cotton cloth ʼ (Prakrtam) potti 'cloth' (Kannada) Rebus: Potr̥, पोतृ 'purifier' Priest (Rigveda). போத்தி pōtti, n. < போற்றி. 1. Grandfather; பாட்டன். Tinn. 2. Brahman temple- priest in Malabar; மலையாளத்திலுள்ள கோயிலருச் சகன்.

The uttarIyam worn by the Priest is potta -- , °taga -- , °tia -- n. ʻ cotton cloth ʼ (Prakrtam) potti 'cloth' (Kannada) Rebus: Potr̥, पोतृ 'purifier' Priest (Rigveda). போத்தி pōtti, n. < போற்றி. 1. Grandfather; பாட்டன். Tinn. 2. Brahman temple- priest in Malabar; மலையாளத்திலுள்ள கோயிலருச் சகன். पोतदार (p. 303) pōtadāra m ( P) An officer under the native governments. His business was to assay all money paid into the treasury. He was also the village-silversmith. (Marathi)

Another word (Meluhha) for the shawl as cloth worn as uttarIyam is: *dhaṭa2 , dhaṭī -- f. ʻ old cloth, loincloth ʼ lex. [Drav., Kan. daṭṭi ʻ waistband ʼ etc., DED 2465] Ku. dhaṛo ʻ piece of cloth ʼ, N. dharo, B. dhaṛā; Or. dhaṛā ʻ rag, loincloth ʼ, dhaṛi ʻ rag ʼ; Mth. dhariā ʻ child's narrow loincloth ʼ.*dhaṭavastra -- .Addenda: *dhaṭa -- 2 . 2. †*dhaṭṭa -- : WPah.kṭg. dhàṭṭu m. ʻ woman's headgear, kerchief ʼ, kc. dhaṭu m. (also dhaṭhu m. ʻ scarf ʼ, J. dhāṭ(h)u m. Him.I 105). This yields the rebus word: dhatu 'mineral ore'.

Thus, read together with the dotted circle fillets worn on the forehead and on the right shoulder, the functions of this person in the guils is to work with dhatu, 'mineral ores' and to smelt them: dhāvaḍ 'smelter'.

R̥gveda tradition lists a number of functionaries engaged in a yajna. The 16 priests include a priest termed as Potr̥, 'purifier'. पोतृ [p= 650,1] प्/ओतृ or पोतृ, m. " Purifier " , N. of one of the 16 officiating priests at a sacrifice (the assistant of the Brahman ; = यज्ञस्य शोधयिट्रि Sa1y. ) RV. Br. S3rS. Hariv. (Monier-Williams). Other functionaries in the yajna are: नेष्टृ [p= 569,3] m. (prob. fr. √ नी aor. stem नेष् ; but cf. Pa1n2. 3-2 , 135 Va1rtt. 2 &c ) one of the chief officiating priests at a सोम sacrifice , he who leads forward the wife of the sacrificer and prepares the सुरा (त्वष्टृ so called RV. i , 15 , 3) RV. Br. S3rS. &c; होतृ [p= 1306,1] m. (fr. √1. हु) an offerer of an oblation or burnt-offering (with fire) , sacrificer , priest , (esp.) a priest who at a sacrifice invokes the gods or recites the ऋग्-वेद , a ऋग्-वेद priest (one of the 4 kinds of officiating priest » ऋत्विज् , p.224; properly the होतृ priest has 3 assistants , sometimes called पुरुषs , viz. the मैत्रा-वरुण , अच्छा-वाक , and ग्रावस्तुत् ; to these are sometimes added three others , the ब्राह्मणाच्छंसिन् , अग्नीध्र or अग्नीध् , and पोतृ , though these last are properly assigned to the Brahman priest ; sometimes the नेष्टृ is substituted for the ग्राव-स्तुत्) RV. &c; ऋत्व्-िज् a [p= 224,2] m. (क्) a priest (usually four are enumerated , viz. होतृ , अध्वर्यु , ब्रह्मन् , and उद्गातृ ; each of them has three companions or helpers , so that the total number is sixteen , viz. होतृ , मैत्रावरुण , अच्छावाक , ग्राव-स्तुत् ; अध्वर्यु , प्रति-प्रस्थातृ , नेष्टृ , उन्ने तृ ; ब्रह्मन् , ब्राह्मणाच्छंसिन् , अग्नीध्र , पोतृ ; उद्गातृ , प्रस्तोतृ , प्रतिहर्तृ , सुब्रह्मण्य A1s3vS3r. iv , 1 , 4-6) RV. AV. TS. S3Br. Ka1tyS3r. &cI suggest that the purifier is a smelter based on a reading of the fillet with a dotted circle worn on the forehead of the 'rpeist' statuette. The dotted circle is a cross-section of a strand. The word for a strand in R̥gveda is dhātu. The rebus of this word dhātu signifies 'mineral ores'. The purifier purifies mineral ores in a smelting process by oxidising impurities to produce a pure metal ingot. Thus, a smelter is a purifier. The fillet with dhātu worn with a strand of string is rebus for dhāi 'strand' PLUS vaṭa 'single strand' yielding the expression: dhāvaḍ A smelter of mineral ores, iron or ferrite ores in particular is called dhāvaḍ in Marathi language Three 'dotted circles' constitute the hypertext expression tri-dhātu, 'three minerals, 'three strands'. vaṭa- string, rope, tie (Samskrtam) is signified by the string which ties the 'dotted circle' on the forehead and right-shoulder of the Priest. The rebus reading is: -vaḍ వటగ 'clever, skilful' (Telugu). Thus, the 'dotted circle' dhāī˜ PLUS vaṭa 'string' is read: dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter'.

The dotted circle fillet worn on the forehead is replicated on a similar fillet worn on the right shoulder. This is a semantic determinative hieroglyph-hypertext expression on the statuette of the 'priest'. See Annex B for an explanation on the evolution of Brahmi syllable symbol for the phoneme dha-.

These orthographic variants provide semantic elucidations for a single: dhātu, dhāū, dhāv 'red stone mineral' or two minerals: dul PLUS dhātu, dhāū, dhāv 'cast minerals' or tri- dhātu, -dhāū, -dhāv 'three minerals' to create metal alloys'. The artisans producing alloys are dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -- smeltersʼ, dhāvḍī ʻcomposed of or relating to ironʼ)(CDIAL 6773)..

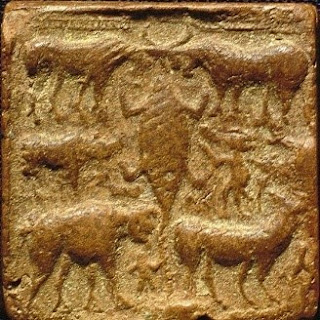

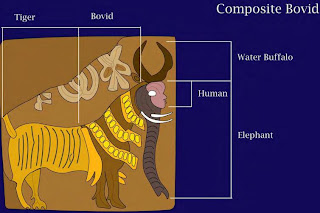

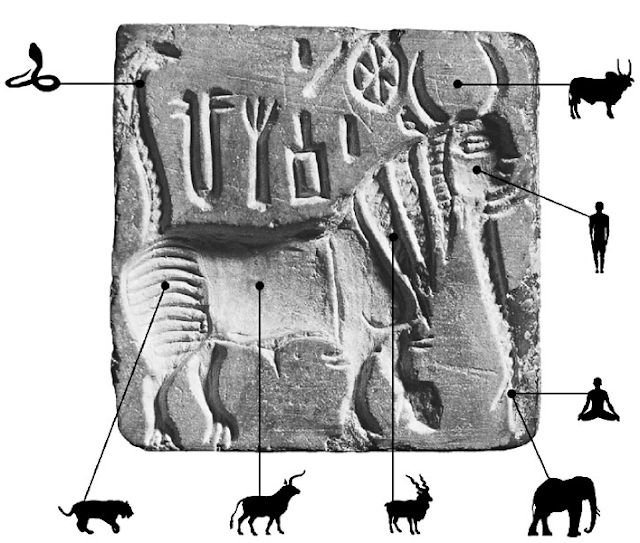

The three red ores signiied on many Sarasvati-Sindhu Script inscriptions are: magnetite, haematite, laterite (Meluhha words: pola (magnetite), gota (laterite), bichi (hematite) magnetite ore [pōḷa], steel [pōlāda]; bica 'haematite, ferrite ore'; gota laterite, ferritte ore'. The hieroglyphs related to these three forms of red ore ferrite minerals are: karibha,ibha' elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' ibbio 'merchant'; goTa 'round stone' rebus: goTa 'laterite ore'; bica 'scorprion' rebus: bicha 'haematite, ferrite ore'; poLa 'zebu bull, bos indicus' rebus: poLa 'magnetite, ferrite ore'.

At an ādi bhautika level, the meaning of the expression tridhātu is provided by the following lexical entries from ancient languages of Bharatiya sprachbund (Meluhha words/expressions):

dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

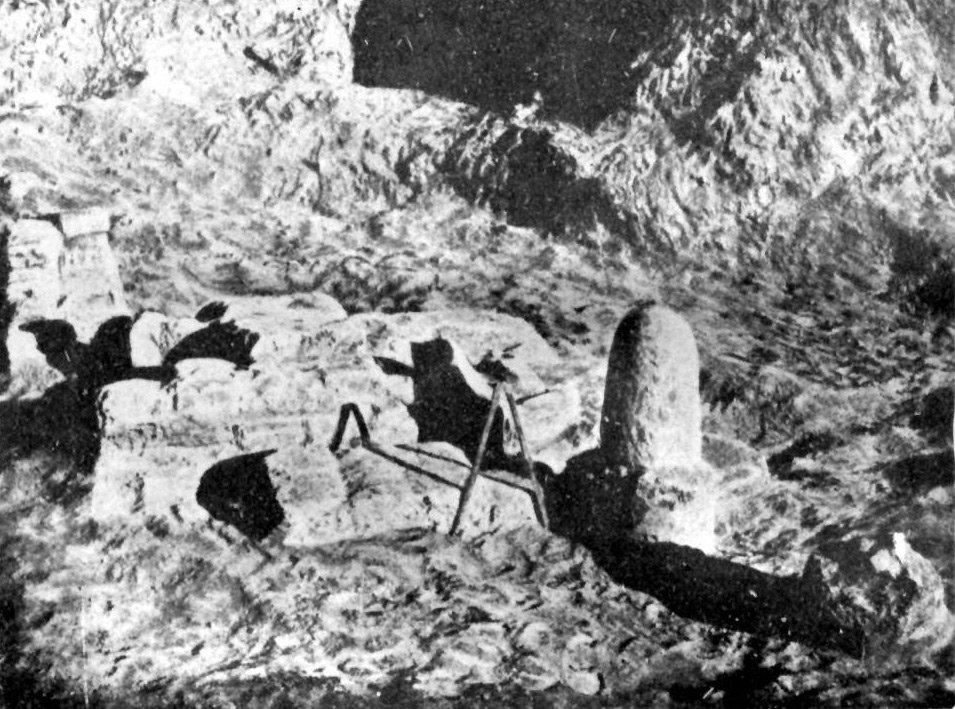

It has been demonstrated that the Binjor discovery of a yajna kunda with an octagonal pillar and a seal with an inscription are signifiers of the performance of a Soma Yajna (Soma Samsthā, one of seven 'Soma enterprises' such as agniṣṭoma, vājapeya, etc.) at the site.

Soma Yajna may be metaphorical accounts of pyrolyis and carburization to harden metal alloys, thus signifying metalwork processes.“Pyrolysis is a thermochemical decomposition of organic material at elevated temperatures in the absence of oxygen (or any halogen). Carburizing, carburising or carburization is a heat treatment process in which iron or steel absorbs carbon liberated when the metal is heated in the presence of a carbon bearing material, such as charcoal or carbon monoxide, with the intent of making the metal harder.” In such an archaeo-metallurgical framework, soma yajna can be seen as a metalwork process in a smelter/furnace of hardening metals/alloys. Soma is called ams'u (synonym). It is cognate with ancu 'iron' (Tocharian). Soma may also relate to assem 'electrum' (Old Egyptian pace Needham). See Annex A for the role played by the yūpa and caṣāla (wheat chaff) atop the yūpa which makes the yūpa a fiery pillar infusing carbon into the metal in fire to harden it as a process of carburization.

The 'priest' statue is evidence of the continuum of the Veda tradition of performance of a yajna with a number of functionaries participating in the process working with fire in a yajna kunda.

Annex A

Excerpts from Raffale Pettazzoni's essay, related to Vajapeya, a Soma Samstha, Soma Yajna:

“A cake made of wheat-flour in the form of a waggon-wheel (rathacakra) was used in ancient India in the celebration of the Vajapeya. This rite, which, perhaps by reason of its popularity, was taken up into the priestly liturgial system of Brahmanism, yet keeps the marks of an archaic character which attests its remote secular origins. In the Brahmanical texts, the vajapeya appears as a special form of the rite of soma, and it is probable that the libation of the sacred drink (-peya from rt. pa-, to drink, according to most etymologists) was the most important action from the priestly point of view. But from various indications it would seem that it is nothing but a secondary development, and the true nature of vajapeya remains rather obscure. It may be said with greater probability that it conferred power and prestige, raising the celebrant above the common condition of mankind. In the description of the vajapeya there are to be noted certain differences between the texts of the black Yajurveda, the Taittiriya Samhita and the Taittiriya Brahmana, which represent the older tradition, and those of the white yajur-veda, the Satapatha Brahmana and the Katyayana Srautasutra, which give a greater number of details.

”The vajapeya was celebrated in autumn. The officiant, who might be a Brahman, a noble, or even, perhaps originally, a Vaisya (Weber, p.770), was the chief actor in the liturgical performance, which, neglecting the secondary divergencies between the different traditions, was carried out, with the assistance of qualified priests, brahmana, adhvaryu, hotr, and udgAtr, in three main actions or movements. The first was a chariot race. Seventeen chariots took part; this number, which is sacred to Prajapati, keeps recurring in the symbolism of the vajapeya (Weber, p. 776). The course was marked out by throwing seventeen javelins one after another, the second being thrown from the point reached by the first and in the same direction, and so on, the point reached by the seventeenth being the goal, which was then marked by planting a branch of udumbara in the ground. The officiant took part in the rae on one of the chariots, while the Brahman, mounted upon a wheel fastened to the top of a post, recited an appropriate formula. The officiant arrived at the goal first and returned in triumph.

“Now came the second act. On the sacrificial post, to which the victims were tied, and which was seventeen cubits high, wrapped in seventeen cloths, and flattened at the top so that it was possible to sit on it, was fastened a wheel of pastry. A ladder was placed against the post. He then touched the round cake, looked to the four cardinal points, and said 'We are become immortal'. (Taitt. Sam. I,7,8 Keith; Satap. Brah. V,2,1,5-14 Eggeling; Katyay xiv,9,21-22 Weber). Now came the third and final act. The officiant coming down from the sacrificial post, was placed on a kind of throne, anointed, and proclaimed samrAj, i.e. 'king of all'.

“The ritual of the vajapeya is full of solar symbols. The Sun, Savitr, with the epithet of deva (deva Savitr) has a leading part in the litanies and perhaps belongs to the primitive kernel of the vajapeya (Weber p.773, n. 2). The race in which the officiant is the winner may be a sybol of the sun's course. The climbing of the sacrificial post symbolises ascension to heaven or, according to Oldenberg, to the sun. 'Come, wife, we will ascend the sky' is what the officiant says while climbing, and when he reaches the top of the post he cries, 'Lo, we have reached the sky, O ye gods!' It would see as if by virtue of the ceremony the officiant himself is transformed into the Sun. According to Katyayana Srautasutra (Weber, pp. 792, 800), before starting to climb the sacrificial post the officiant is hailed with certain formulae, twelve Apti and six kLpti, which declare him lord of the twelve months and the six seasons (Rtu), i.e. of the year. According to Taitt.Sam. p. 107 foll. Keith, while he is climbing twelve libations are made, and a formula recited consisting of the twelve symbolic names of the months, or in other versions thirteen, i.e. twelve plus the intercalary month. During the ritual the officiant and his wife, also the priests, wear gold crowns on their heads, and when the officiant descends from the sacrificial post, he sets his foot on a hide stretched on the ground and on some gold which lies on it (Hillebrandt). Gold is often employed in Brahman ritual as a symbol of the sun. In a soma-rite of the same type (Sodas'in) as the vajapeya, a hymn is chanted as the sun declines, and there is present a horse which must be either white, dark chestnut, or black. The singers while they are singing hold gold in their hands. In other cases, as the water used in the sacrifice must be drawn before the sun sets, the officiant who has not remembered to do this in time may draw it when the sun has already gone down, but he must then hold over the water either fire (a burning brand) or else gold, as symbols and surrogates of the sun.

“The wheel-shaped cake is another piece of solar symbolism in the vajapeya, for the wheel is an obvious symbol of the sun, whether by reason fo its circular form or by a patent allusion to the course of the sun's chariot across the sky. Other instance of the wheel-ritual in ancient Indian have been collected by W. Caland, Das Rad im Ritual, in Zeitsch. Der Deutschen Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft liii (1899), 699-701. As early as the Rigveda the sun is thought of as a wheel (Rigveda I.30.19), sometimes even as a wheel drawn by a horse (ibid. vii, 63..2; 66.4). This sets one thinking of the well-known otive monument from Trundholm in Denmark, which consists of a gilded bronze disk drawn by a horse and mounted on three pairs of wheels (K. Helm, Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte I, Heidelberg 1913, 177; J. de Vries, Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte I, Berlin 1935, Plate 2), and less directy of certain rock-carvings a Bohuslan in southern Sweden, in which the sun is represented by a wheel on top of a pole (O. Almgren, Nordische Felszeichnungen als religiose Urkunden, Frankfurt a/M 1934, Figs. 1-6; J. Bing, Der Kultwagen von Trundholm und die nordischen Felszeichnungen,IPEK ii, 1926, 236-54).

[Raffale Pettazzoni, 67, Ch. IX. The wheel in the ritual symbolism of some Indo-European peoples, in: Raffaele Petlazzoni, Essays on the History of Religions, Brille Archive, pp. 100-109; loc.cit. Alex Weber, Ueber den vajapeya, in Sitz. Berl. Akad. 1892, ii, 765-813; A. Hillebrandt, Ritual Literatur (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie u. Alterumswissenschaftiii,2, Strassburg 1897, 140 foll.; same, Vedische Mythologie, ed. 2 (Breslau 1927), 484; H. Oldenburg, Die Religion des Veda ed. 304 (Stuttgart and Berlin 1922), 85 foll., 415; AB Keith, The Veda of the Black Yajus School entitled Taittiriya Samhita, translated, i (Cambridge, Mass, 1914), viii foll., 104 foll.; J. Eggeling, The Satapatha Brahmana, Pt. Iii Sacred Books of the East xli, Oxford 1894, I foll., 31 foll.'] https://books.google.co.in/books?id=xtsUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA95&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

Annex B

Evolution ḍha-, dha- in Brahmi script syllables are evocative of 'string' and 'circle, dotted circle' as may be seen from the following orthographic evidence of epigraphs dated from ca. 300 BCE: ![]()

It may be seen from the table of evoution of Brahmi script orthography that

1. a circle signified the Brahmi syllable '

2. a string with a twist signified the syllable 'da-', a string ending in a circled twist signified the syllable '

Section 4: Orthograhy of Brahmi syllabary from ca. 300 BCEవడము (p. 1124) vaḍamu vaḍamu. [Tel.] n. A very thick rope. మోకు. A garland, దండ. తేరివడము a rope used to drag a car. vaṭa2 ʻ string ʼ lex. [Prob. ← Drav. Tam. vaṭam, Kan. vaṭi, vaṭara,] N. bariyo ʻ cord, rope ʼ; Bi. barah ʻ rope working irrigation lever ʼ, barhā ʻ thick well -- rope ʼ, Mth. barahā ʻ rope ʼ.vaṭāraka -- , vaṭin -- ; *karṇavaṭikā -- , *yantravaṭa -- .(CDIAL 11212) vaṭāraka -- , varāṭaka -- m. ʻ string ʼ MBh. [vaṭa -- 2 ]Pa. sa -- vaṭākara -- ʻ having a cable ʼ; Bi. baral -- rassī ʻ twisted string ʼ; H. barrā m. ʻ rope ʼ, barārā m. ʻ thong ʼ. (CDIAL 11217) *karṇavaṭikā ʻ side -- cord ʼ. [kárṇa -- , vaṭa -- 2 ]WPah. bhal. k*l nɔṛi f. ʻ knots between upper and lower parts of a snow -- shoe, rope pegs to which the distaff in a spinning -- wheel is attached ʼ.(CDIAL 2842) *yantravaṭa ʻ cord of a machine ʼ. [Cf. Pa. yantasutta- n. -- yantrá -- , vaṭa -- 2 ]WPah.bhal. jaṇṭḷoṛ m. ʻ long string round spinning wheel ʼ.(CDIAL 10413) Ta. vaṭam cable, large rope, cord, bowstring, strands of a garland, chains of a necklace; vaṭi rope; vaṭṭi (-pp-, -tt-) to tie. Ma. vaṭam rope, a rope of cowhide (in plough), dancing rope, thick rope for dragging timber. Ka. vaṭa, vaṭara, vaṭi string, rope, tie. Te. vaṭi rope, cord. Go. (Mu.) vaṭiya strong rope made of paddy straw (Voc.3150). Cf. 3184 Ta. tār̤vaṭam. / Cf. Skt. vaṭa- string, rope, tie; vaṭāraka-, vaṭākara-, varāṭaka- cord, string; Turner, CDIAL, no. 11212.(DEDR 5220) வடம்¹ vaṭam , n. < vaṭa. 1. Cable, large rope, as for drawing a temple-car; கனமான கயிறு. வடமற்றது (நன். 219, மயிலை.). 2. Cord; தாம்பு. (சூடா.) 3. A loop of coir rope, used for climbing palm-trees; மரமேறவுதவுங் கயிறு. Loc. 4. Bowstring; வில்லின் நாணி. (பிங்.) 5. String of jewels; மணிவடம். வடங்கள் அசையும்படி உடுத்து (திருமுரு. 204, உரை). (சூடா.) 6. Strands of a garland; chains of a necklace; சரம். இடை மங்கை கொங்கை வடமலைய (அஷ்டப். திருவேங்கடத் தந். 39). 7. Arrangement; ஒழுங்கு. தொடங்கற் காலை வடம்பட விளங்கும் (ஞானா. 14, 41). தாழ்வடம் tāḻ-vaṭam , n. < id. +. 1. [M. tāḻvaṭam.] Necklace of pearls or beads; கழுத் தணி. தாவி றாழ்வடம் தயங்க (சீவக. 2426). 2. String of Rudrākṣa beads; உருத்திராக்கமாலை. மார்பின்மீதிலே தாழ்வடங்கள் மனதிலே கரவடமாம் (தண்டலை. சத. 29).

వటగ (p. 1122) vaṭaga , వటారి or వఠారి vaṭaga. [Tel.] adj. Clever, skilful, నేర్పుగల,

वराटक [p= 921,1] a rope , cord , string (only ifc. , with f(आ).) MBh. xii , 2488 v.l. वरारका वरारक [p= 923,2] n. a diamond L.

pōta2 m. ʻ cloth ʼ, pōtikā -- f. lex. 2. *pōtta -- 2 (sanskrit- ized as pōtra -- 2 n. ʻ cloth ʼ lex.). 3. *pōttha -- 2 ~ pavásta<-> n. ʻ covering (?) ʼ RV., ʻ rough hempen cloth ʼ AV. T. Chowdhury JBORS xvii 83. 4. pōntī -- f. ʻ cloth ʼ Divyāv. 5. *pōcca -- 2 < *pōtya -- ? (Cf. pōtyā = pōtānāṁ samūhaḥ Pāṇ.gaṇa. -- pṓta -- 1 ?). [Relationship with prōta -- n. ʻ woven cloth ʼ lex., plōta -- ʻ bandage, cloth ʼ Suśr. or with pavásta -- is obscure: EWA ii 347 with lit. Forms meaning ʻ cloth to smear with, smearing ʼ poss. conn. with or infl. by pusta -- 2 n. ʻ working in clay ʼ (prob. ← Drav., Tam. pūcu &c. DED 3569, EWA ii 319)]

1. Pk. pōa -- n. ʻ cloth ʼ; Paš.ar. pōwok ʻ cloth ʼ, pōg ʻ net, web ʼ (but lauṛ. dar. pāwāk ʻ cotton cloth ʼ, Gaw. pāk IIFL iii 3, 150).

2. Pk. potta -- , °taga -- , °tia -- n. ʻ cotton cloth ʼ, pottī -- , °tiā -- , °tullayā -- , puttī -- f. ʻ piece of cloth, man's dhotī, woman's sāṛī ʼ, pottia -- ʻ wearing clothes ʼ; S. potī f. ʻ shawl ʼ, potyo m. ʻ loincloth ʼ; L. pot, pl. °tã f. ʻ width of cloth ʼ; P. potṛā m. ʻ child's clout ʼ, potṇā ʻ to smear a wall with a rag ʼ; N. poto ʻ rag to lay on lime -- wash ʼ,potnu ʻ to smear ʼ; Or. potā ʻ gunny bag ʼ; OAw. potaï ʻ smears, plasters ʼ; H. potā m. ʻ whitewashing brush ʼ, potī f. ʻ red cotton ʼ, potiyā m. ʻ loincloth ʼ, potṛā m. ʻ baby clothes ʼ; G. pot n. ʻ fine cloth, texture ʼ, potũ n. ʻ rag ʼ, potī f., °tiyũ n. ʻ loincloth ʼ, potṛī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; M. pot m. ʻ roll of coarse cloth ʼ, n. ʻ weftage or texture of cloth ʼ, potrẽ n. ʻ rag for smearing cowdung ʼ.

3. Pa. potthaka -- n. ʻ cheap rough hemp cloth ʼ, potthakamma -- n. ʻ plastering ʼ; Pk. pottha -- , °aya -- n.m. ʻ cloth ʼ; S. potho m. ʻ lump of rag for smearing, smearing, cloth soaked in opium ʼ.

4. Pa. ponti -- ʻ rags ʼ.

5. Wg. pōč ʻ cotton cloth, muslin ʼ, Kt. puč; Pr. puč ʻ duster, cloth ʼ, pūˊčuk ʻ clothes ʼ; S. poco m. ʻ rag for plastering, plastering ʼ; P. poccā m. ʻ cloth or brush for smearing ʼ, pocṇā ʻ to smear with earth ʼ; Or. pucā̆ra, pucurā ʻ wisp of rag or jute for whitewashing with, smearing with such a rag ʼ.

*maṣipōtta -- . pōta -- 3 ʻ boat ʼ see *plōtra -- . pōta -- 4 ʻ foundation ʼ see *pēnda -- .

*pōtara -- ʻ young ʼ, pōtalaka -- see pṓta -- 1 . Addenda: pōta -- 2 . 2. *pōtta -- 2 : S.kcch. potyo m. ʻ small dhoti ʼ.(CDIAL 8400) Ta. potti garment of fibres, cloth. Ka. potti cloth. Te. potti bark, a baby's linen, a sort of linen cloth; pottika a small fine cloth; podugu a baby's linen. Kol. (SSTW)pot sari. Pa. bodgid a short loincloth. / Cf. Skt. potikā-, Pkt. potti-, pottiā-, etc.; Turner, CDIAL, no. 8400. (DEDR 4515)

पोत (p. 303) pōta m f A bead of glass and, sometimes, of gold and of stone. 2 m A neck-ornament of females made of these beads.

58) पोत (p. 303) pōta m ( or P) A link composed of rolls of coarse cloth. This portion, together with the विडी or iron handle, constitute the मशालor torch. 2 The head, end, point (of a tool, stick &c.): also the end or extreme portion (of a thing gen.) 3 m A seton; and fig. the hole of a फाळ or ploughshare.

59) पोत (p. 303) pōta n m ( H Quality; or formed by redup. out of सूत with which word it is generally conjoined in use.) Weftage or texture (of cloth); quality as respects closeness, firmness, body. Ex. सूत- पोत पाहून धोत्र घ्यावें.

पोंत (p. 303) pōnta m (In Konkan̤ neuter.) A seton.

61) पोतडी (p. 303) pōtaḍī f पोतडें n (पोतें) A bag, esp. the circular bag of goldsmiths, shroffs &c. containing their weights, scales, coins &c.

62) पोतंडी (p. 303) pōtaṇḍī f A little thing (as a nut, a pebble,) or a small quantity (as of sugar, flour, grain) put up in a corner of a cloth and confined by a knot; thus forming a knob or ball. 2 Medicaments tied up in a corner of a cloth, to be dabbed on the eye or other part: also a cloth rolled up into a ball, heated, and applied to foment. v दे,लाव, also पोतंडीनें or पोतंडीचा शेक.

63) पोतदार (p. 303) pōtadāra m ( P) An officer under the native governments. His business was to assay all money paid into the treasury. He was also the village-silversmith.

64) पोतदारी (p. 303) pōtadārī f ( P) The office or business of पोतदार: also his rights or fees.

65) पोतनिशी (p. 303) pōtaniśī f ( P) The office or business of पोतनीस.

66) पोतनीस (p. 303) pōtanīsa m ( P) The treasurer or cash-keeper. पोतें (p. 303) pōtēṃ n ( or P) A sack or large bag. 2 The treasury or the treasure-bags of Government. 3 The treasure-bag of a village made up for the district-treasury.

73) पोतेखाद (p. 303) pōtēkhāda f Wastage or loss on goods (as on sugar &c.) from adhesion to the containing sack or bag.

74) पोतेचाल (p. 303) pōtēcāla f (Treasury-currency.) The currency in which the public revenue is received. 2 Used as a Of that currency; as पोतेचालीचा (रूपया-पैसा- नाणें &c.) Coin or money admitted into or issued from the Government-treasury; sterling money of the realm.

75) पोतेझाडा (p. 303) pōtējhāḍā m Settlement of the accounts of the treasury.

76) पोतेरें (p. 303) pōtērēṃ n A clout or rag (as used in cowdunging floors &c.) 2 By meton. The smearing of cowdung effected by means of it. पो0 करून टाकणें To treat with exceeding slight and contumely. (Marathi)

धावड (p. 250) dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. In these parts they are Muhammadans. धावडी (p. 250) dhāvaḍī a Relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron.

धातु 1[p= 513,3]m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3.constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf. त्रिविष्टि- ,सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &celement , primitive matter (= महा-भूत L. ) MBh. Hariv. &c (usually reckoned as 5 , viz. ख or आकाश , अनिल , तेजस् , जल , भू; to which is added ब्रह्म Ya1jn5. iii , 145 ; or विज्ञान Buddh. )a constituent element or essential ingredient of the body (distinct from the 5 mentioned above and conceived either as 3 humours [called also दोष] phlegm , wind and bile BhP. [cf. पुरीष , मांस , मनस् , ChUp. vi , 5 , 1] ; or as the 5 organs of sense , इन्द्रियाणि [cf. s.v. and MBh. xii , 6842 , where श्रोत्र , घ्राण , आस्य , हृदय and कोष्ठ are mentioned as the 5 धातु of the human body born from the either] and the 5 properties of the elements perceived by them , गन्ध , रस , रूप , स्पर्श andशब्द L. ; or the 7 fluids or secretions , chyle , blood , flesh , fat , bone , marrow , semen Sus3r. [ L. रसा*दि or रस-रक्ता*दि, of which sometimes 10 are given , the above 7 and hair , skin , sinews BhP. ])primary element of the earth i.e. metal , mineral , are (esp. a mineral of a red colour) Mn. MBh. &c element of wordsi.e. grammatical or verbal root or stem Nir. Pra1t. MBh. &c (with the southern Buddhists धातु means either the 6 elements [see above] Dharmas. xxv ; or the 18 elementary spheres [धातु-लोक] ib. lviii ; or the ashes of the body , relicsL. [cf. -गर्भ]). dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf.tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ]![]()

Seated male sculpture, or "Priest King" from Mohenjo-daro (41,42,43). Fillet or ribbon headband with circular inlay ornament on the forehead and similar but smaller ornament on the right upper arm. The two ends of the fillet fall along the back and though the hair is carefully combed towards the back of the head, no bun is present. The flat back of the head may have held a separately carved bun as is traditional on the other seated figures, or it could have held a more elaborate horn and plumed headdress.Two holes beneath the highly stylized ears suggest that a necklace or other head ornament was attached to the sculpture. The left shoulder is covered with a cloak decorated with trefoil, double circle and single circle designs that were originally filled with red pigment. Drill holes in the center of each circle indicate they were made with a specialized drill and then touched up with a chisel. Eyes are deeply incised and may have held inlay. The upper lip is shaved and a short combed beard frames the face. The large crack in the face is the result of weathering or it may be due to original firing of this object.Material: white, low fired steatite

Dimensions: 17.5 cm height, 11 cm width

Mohenjo-daro, DK 1909

National Museum, Karachi, 50.852

Marshall 1931: 356-7, pl. XCVIII

Source: https://www.harappa.com/slide/priest-king-mohenjo-daro

S. KalyanaramanSarasvati Research CenterMay 19, 2017

R̥gveda tradition lists a number of functionaries engaged in a yajna. The 16 priests include a priest termed as Potr̥, 'purifier'. पोतृ [p= 650,1] प्/ओतृ or पोतृ, m. " Purifier " , N. of one of the 16 officiating priests at a sacrifice (the assistant of the Brahman ; = यज्ञस्य शोधयिट्रि Sa1y. ) RV. Br. S3rS. Hariv. (Monier-Williams). Other functionaries in the yajna are: नेष्टृ [p= 569,3] m. (prob. fr. √ नी aor. stem नेष् ; but cf. Pa1n2. 3-2 , 135 Va1rtt. 2 &c ) one of the chief officiating priests at a सोम sacrifice , he who leads forward the wife of the sacrificer and prepares the सुरा (त्वष्टृ so called RV. i , 15 , 3) RV. Br. S3rS. &c; होतृ [p= 1306,1] m. (fr. √1. हु) an offerer of an oblation or burnt-offering (with fire) , sacrificer , priest , (esp.) a priest who at a sacrifice invokes the gods or recites the ऋग्-वेद , a ऋग्-वेद priest (one of the 4 kinds of officiating priest » ऋत्विज् , p.224; properly the होतृ priest has 3 assistants , sometimes called पुरुषs , viz. the मैत्रा-वरुण , अच्छा-वाक , and ग्रावस्तुत् ; to these are sometimes added three others , the ब्राह्मणाच्छंसिन् , अग्नीध्र or अग्नीध् , and पोतृ , though these last are properly assigned to the Brahman priest ; sometimes the नेष्टृ is substituted for the ग्राव-स्तुत्) RV. &c; ऋत्व्-िज् a [p= 224,2] m. (क्) a priest (usually four are enumerated , viz. होतृ , अध्वर्यु , ब्रह्मन् , and उद्गातृ ; each of them has three companions or helpers , so that the total number is sixteen , viz. होतृ , मैत्रावरुण , अच्छावाक , ग्राव-स्तुत् ; अध्वर्यु , प्रति-प्रस्थातृ , नेष्टृ , उन्ने तृ ; ब्रह्मन् , ब्राह्मणाच्छंसिन् , अग्नीध्र , पोतृ ;

उद्गातृ , प्रस्तोतृ , प्रतिहर्तृ , सुब्रह्मण्य A1s3vS3r. iv , 1 , 4-6) RV. AV. TS. S3Br. Ka1tyS3r. &c

I suggest that the purifier is a smelter based on a reading of the fillet with a dotted circle worn on the forehead of the 'rpeist' statuette. The dotted circle is a cross-section of a strand. The word for a strand in R̥gveda is dhātu. The rebus of this word dhātu signifies 'mineral ores'. The purifier purifies mineral ores in a smelting process by oxidising impurities to produce a pure metal ingot. Thus, a smelter is a purifier. The fillet with dhātu worn with a strand of string is rebus for dhāi 'strand' PLUS vaṭa 'single strand' yielding the expression: dhāvaḍ A smelter of mineral ores, iron or ferrite ores in particular is called dhāvaḍ in Marathi language Three 'dotted circles' constitute the hypertext expression tri-dhātu, 'three minerals, 'three strands'. vaṭa- string, rope, tie (Samskrtam) is signified by the string which ties the 'dotted circle' on the forehead and right-shoulder of the Priest. The rebus reading is: -vaḍ వటగ 'clever, skilful' (Telugu). Thus, the 'dotted circle' dhāī˜ PLUS vaṭa 'string' is read: dhā̆vaḍ 'smelter'.

The dotted circle fillet worn on the forehead is replicated on a similar fillet worn on the right shoulder. This is a semantic determinative hieroglyph-hypertext expression on the statuette of the 'priest'. See Annex B for an explanation on the evolution of Brahmi syllable symbol for the phoneme dha-.

These orthographic variants provide semantic elucidations for a single: dhātu, dhāū, dhāv 'red stone mineral' or two minerals: dul PLUS dhātu, dhāū, dhāv 'cast minerals' or tri- dhātu, -dhāū, -dhāv 'three minerals' to create metal alloys'. The artisans producing alloys are dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron -- smeltersʼ, dhāvḍī ʻcomposed of or relating to ironʼ)(CDIAL 6773)..

The three red ores signiied on many Sarasvati-Sindhu Script inscriptions are: magnetite, haematite, laterite (Meluhha words: pola (magnetite), gota (laterite), bichi (hematite) magnetite ore [pōḷa], steel [pōlāda]; bica 'haematite, ferrite ore'; gota laterite, ferritte ore'. The hieroglyphs related to these three forms of red ore ferrite minerals are: karibha,ibha' elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron' ibbio 'merchant'; goTa 'round stone' rebus: goTa 'laterite ore'; bica 'scorprion' rebus: bicha 'haematite, ferrite ore'; poLa 'zebu bull, bos indicus' rebus: poLa 'magnetite, ferrite ore'.

At an ādi bhautika level, the meaning of the expression tridhātu is provided by the following lexical entries from ancient languages of Bharatiya sprachbund (Meluhha words/expressions):

dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ] Pa. dhātu -- m. ʻ element, ashes of the dead, relic ʼ; KharI. dhatu ʻ relic ʼ; Pk. dhāu -- m. ʻ metal, red chalk ʼ; N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ); -- Si. dā ʻ relic ʼ; -- S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. (CDIAL 6773)

dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf. tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√

It has been demonstrated that the Binjor discovery of a yajna kunda with an octagonal pillar and a seal with an inscription are signifiers of the performance of a Soma Yajna (Soma Samsthā, one of seven 'Soma enterprises' such as agniṣṭoma, vājapeya, etc.) at the site.

Soma Yajna may be metaphorical accounts of pyrolyis and carburization to harden metal alloys, thus signifying metalwork processes.“Pyrolysis is a thermochemical decomposition of organic material at elevated temperatures in the absence of oxygen (or any halogen). Carburizing, carburising or carburization is a heat treatment process in which iron or steel absorbs carbon liberated when the metal is heated in the presence of a carbon bearing material, such as charcoal or carbon monoxide, with the intent of making the metal harder.” In such an archaeo-metallurgical framework, soma yajna can be seen as a metalwork process in a smelter/furnace of hardening metals/alloys. Soma is called ams'u (synonym). It is cognate with ancu 'iron' (Tocharian). Soma may also relate to assem 'electrum' (Old Egyptian pace Needham). See Annex A for the role played by the yūpa and caṣāla (wheat chaff) atop the yūpa which makes the yūpa a fiery pillar infusing carbon into the metal in fire to harden it as a process of carburization.

The 'priest' statue is evidence of the continuum of the Veda tradition of performance of a yajna with a number of functionaries participating in the process working with fire in a yajna kunda.

Annex A

Excerpts from Raffale Pettazzoni's essay, related to Vajapeya, a Soma Samstha, Soma Yajna:

“A cake made of wheat-flour in the form of a waggon-wheel (rathacakra) was used in ancient India in the celebration of the Vajapeya. This rite, which, perhaps by reason of its popularity, was taken up into the priestly liturgial system of Brahmanism, yet keeps the marks of an archaic character which attests its remote secular origins. In the Brahmanical texts, the vajapeya appears as a special form of the rite of soma, and it is probable that the libation of the sacred drink (-peya from rt. pa-, to drink, according to most etymologists) was the most important action from the priestly point of view. But from various indications it would seem that it is nothing but a secondary development, and the true nature of vajapeya remains rather obscure. It may be said with greater probability that it conferred power and prestige, raising the celebrant above the common condition of mankind. In the description of the vajapeya there are to be noted certain differences between the texts of the black Yajurveda, the Taittiriya Samhita and the Taittiriya Brahmana, which represent the older tradition, and those of the white yajur-veda, the Satapatha Brahmana and the Katyayana Srautasutra, which give a greater number of details.

”The vajapeya was celebrated in autumn. The officiant, who might be a Brahman, a noble, or even, perhaps originally, a Vaisya (Weber, p.770), was the chief actor in the liturgical performance, which, neglecting the secondary divergencies between the different traditions, was carried out, with the assistance of qualified priests, brahmana, adhvaryu, hotr, and udgAtr, in three main actions or movements. The first was a chariot race. Seventeen chariots took part; this number, which is sacred to Prajapati, keeps recurring in the symbolism of the vajapeya (Weber, p. 776). The course was marked out by throwing seventeen javelins one after another, the second being thrown from the point reached by the first and in the same direction, and so on, the point reached by the seventeenth being the goal, which was then marked by planting a branch of udumbara in the ground. The officiant took part in the rae on one of the chariots, while the Brahman, mounted upon a wheel fastened to the top of a post, recited an appropriate formula. The officiant arrived at the goal first and returned in triumph.

“Now came the second act. On the sacrificial post, to which the victims were tied, and which was seventeen cubits high, wrapped in seventeen cloths, and flattened at the top so that it was possible to sit on it, was fastened a wheel of pastry. A ladder was placed against the post. He then touched the round cake, looked to the four cardinal points, and said 'We are become immortal'. (Taitt. Sam. I,7,8 Keith; Satap. Brah. V,2,1,5-14 Eggeling; Katyay xiv,9,21-22 Weber). Now came the third and final act. The officiant coming down from the sacrificial post, was placed on a kind of throne, anointed, and proclaimed samrAj, i.e. 'king of all'.

“The ritual of the vajapeya is full of solar symbols. The Sun, Savitr, with the epithet of deva (deva Savitr) has a leading part in the litanies and perhaps belongs to the primitive kernel of the vajapeya (Weber p.773, n. 2). The race in which the officiant is the winner may be a sybol of the sun's course. The climbing of the sacrificial post symbolises ascension to heaven or, according to Oldenberg, to the sun. 'Come, wife, we will ascend the sky' is what the officiant says while climbing, and when he reaches the top of the post he cries, 'Lo, we have reached the sky, O ye gods!' It would see as if by virtue of the ceremony the officiant himself is transformed into the Sun. According to Katyayana Srautasutra (Weber, pp. 792, 800), before starting to climb the sacrificial post the officiant is hailed with certain formulae, twelve Apti and six kLpti, which declare him lord of the twelve months and the six seasons (Rtu), i.e. of the year. According to Taitt.Sam. p. 107 foll. Keith, while he is climbing twelve libations are made, and a formula recited consisting of the twelve symbolic names of the months, or in other versions thirteen, i.e. twelve plus the intercalary month. During the ritual the officiant and his wife, also the priests, wear gold crowns on their heads, and when the officiant descends from the sacrificial post, he sets his foot on a hide stretched on the ground and on some gold which lies on it (Hillebrandt). Gold is often employed in Brahman ritual as a symbol of the sun. In a soma-rite of the same type (Sodas'in) as the vajapeya, a hymn is chanted as the sun declines, and there is present a horse which must be either white, dark chestnut, or black. The singers while they are singing hold gold in their hands. In other cases, as the water used in the sacrifice must be drawn before the sun sets, the officiant who has not remembered to do this in time may draw it when the sun has already gone down, but he must then hold over the water either fire (a burning brand) or else gold, as symbols and surrogates of the sun.

“The wheel-shaped cake is another piece of solar symbolism in the vajapeya, for the wheel is an obvious symbol of the sun, whether by reason fo its circular form or by a patent allusion to the course of the sun's chariot across the sky. Other instance of the wheel-ritual in ancient Indian have been collected by W. Caland, Das Rad im Ritual, in Zeitsch. Der Deutschen Morgenlandischen Gesellschaft liii (1899), 699-701. As early as the Rigveda the sun is thought of as a wheel (Rigveda I.30.19), sometimes even as a wheel drawn by a horse (ibid. vii, 63..2; 66.4). This sets one thinking of the well-known otive monument from Trundholm in Denmark, which consists of a gilded bronze disk drawn by a horse and mounted on three pairs of wheels (K. Helm, Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte I, Heidelberg 1913, 177; J. de Vries, Altgermanische Religionsgeschichte I, Berlin 1935, Plate 2), and less directy of certain rock-carvings a Bohuslan in southern Sweden, in which the sun is represented by a wheel on top of a pole (O. Almgren, Nordische Felszeichnungen als religiose Urkunden, Frankfurt a/M 1934, Figs. 1-6; J. Bing, Der Kultwagen von Trundholm und die nordischen Felszeichnungen,IPEK ii, 1926, 236-54).

[Raffale Pettazzoni, 67, Ch. IX. The wheel in the ritual symbolism of some Indo-European peoples, in: Raffaele Petlazzoni, Essays on the History of Religions, Brille Archive, pp. 100-109; loc.cit. Alex Weber, Ueber den vajapeya, in Sitz. Berl. Akad. 1892, ii, 765-813; A. Hillebrandt, Ritual Literatur (Grundriss der indo-arischen Philologie u. Alterumswissenschaftiii,2, Strassburg 1897, 140 foll.; same, Vedische Mythologie, ed. 2 (Breslau 1927), 484; H. Oldenburg, Die Religion des Veda ed. 304 (Stuttgart and Berlin 1922), 85 foll., 415; AB Keith, The Veda of the Black Yajus School entitled Taittiriya Samhita, translated, i (Cambridge, Mass, 1914), viii foll., 104 foll.; J. Eggeling, The Satapatha Brahmana, Pt. Iii Sacred Books of the East xli, Oxford 1894, I foll., 31 foll.'] https://books.google.co.in/books?id=xtsUAAAAIAAJ&pg=PA95&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=3#v=onepage&q&f=false

Annex B

Section 4: Orthograhy of Brahmi syllabary from ca. 300 BCE

वराटक [p= 921,1] a rope , cord , string (only ifc. , with f(आ).) MBh. xii , 2488 v.l. वरारका वरारक [p= 923,2] n. a diamond L.

pōta

1. Pk. pōa -- n. ʻ cloth ʼ; Paš.ar. pōwok ʻ cloth ʼ, pō

2. Pk. potta -- , °taga -- , °tia -- n. ʻ cotton cloth ʼ, pottī -- , °tiā -- , °tullayā -- , puttī -- f. ʻ piece of cloth, man's dhotī, woman's sāṛī ʼ, pottia -- ʻ wearing clothes ʼ; S. potī f. ʻ shawl ʼ, potyo m. ʻ loincloth ʼ; L. pot, pl. °tã f. ʻ width of cloth ʼ; P. potṛā m. ʻ child's clout ʼ, potṇā ʻ to smear a wall with a rag ʼ; N. poto ʻ rag to lay on lime -- wash ʼ,potnu ʻ to smear ʼ; Or. potā ʻ gunny bag ʼ; OAw. potaï ʻ smears, plasters ʼ; H. potā m. ʻ whitewashing brush ʼ, potī f. ʻ red cotton ʼ, potiyā m. ʻ loincloth ʼ, potṛā m. ʻ baby clothes ʼ; G. pot n. ʻ fine cloth, texture ʼ, potũ n. ʻ rag ʼ, potī f., °tiyũ n. ʻ loincloth ʼ, potṛī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; M. pot m. ʻ roll of coarse cloth ʼ, n. ʻ weftage or texture of cloth ʼ, potrẽ n. ʻ rag for smearing cowdung ʼ.

3. Pa. potthaka -- n. ʻ cheap rough hemp cloth ʼ, potthakamma -- n. ʻ plastering ʼ; Pk. pottha -- , °aya -- n.m. ʻ cloth ʼ; S. potho m. ʻ lump of rag for smearing, smearing, cloth soaked in opium ʼ.

4. Pa. ponti -- ʻ rags ʼ.

5. Wg. pōč ʻ cotton cloth, muslin ʼ, Kt. puč; Pr. puč ʻ duster, cloth ʼ, pūˊčuk ʻ clothes ʼ; S. poco m. ʻ rag for plastering, plastering ʼ; P. poccā m. ʻ cloth or brush for smearing ʼ, pocṇā ʻ to smear with earth ʼ; Or. pucā̆ra, pucurā ʻ wisp of rag or jute for whitewashing with, smearing with such a rag ʼ.

*

*pōtara -- ʻ young ʼ, pōtalaka -- see

58)

59)

61)

62)

63)

64)

65)

66)

73)

74)

75)

76)

धातु 1[p= 513,3]m. layer , stratum Ka1tyS3r. Kaus3.constituent part , ingredient (esp. [ and in RV. only] ifc. , where often = " fold " e.g. त्रि-ध्/आतु , threefold &c ; cf. त्रिविष्टि- ,सप्त- , सु-) RV. TS. S3Br. &celement , primitive matter (= महा-भूत L. ) MBh. Hariv. &c (usually reckoned as 5 , viz. ख or आकाश , अनिल , तेजस् , जल , भू; to which is added ब्रह्म Ya1jn5. iii , 145 ; or विज्ञान Buddh. )a constituent element or essential ingredient of the body (distinct from the 5 mentioned above and conceived either as 3 humours [called also दोष] phlegm , wind and bile BhP. [cf. पुरीष , मांस , मनस् , ChUp. vi , 5 , 1] ; or as the 5 organs of sense , इन्द्रियाणि [cf. s.v. and MBh. xii , 6842 , where श्रोत्र , घ्राण , आस्य , हृदय and कोष्ठ are mentioned as the 5 धातु of the human body born from the either] and the 5 properties of the elements perceived by them , गन्ध , रस , रूप , स्पर्श andशब्द L. ; or the 7 fluids or secretions , chyle , blood , flesh , fat , bone , marrow , semen Sus3r. [ L. रसा*दि or रस-रक्ता*दि, of which sometimes 10 are given , the above 7 and hair , skin , sinews BhP. ])primary element of the earth i.e. metal , mineral , are (esp. a mineral of a red colour) Mn. MBh. &c element of wordsi.e. grammatical or verbal root or stem Nir. Pra1t. MBh. &c (with the southern Buddhists धातु means either the 6 elements [see above] Dharmas. xxv ; or the 18 elementary spheres [धातु-लोक] ib. lviii ; or the ashes of the body , relicsL. [cf. -गर्भ]). dhāˊtu n. ʻ substance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour) ʼ Mn., ʻ ashes of the dead ʼ lex., ʻ *strand of rope ʼ (cf.tridhāˊtu -- ʻ threefold ʼ RV., ayugdhātu -- ʻ having an uneven number of strands ʼ KātyŚr.). [√dhā ]

Seated male sculpture, or "Priest King" from Mohenjo-daro (41,42,43). Fillet or ribbon headband with circular inlay ornament on the forehead and similar but smaller ornament on the right upper arm. The two ends of the fillet fall along the back and though the hair is carefully combed towards the back of the head, no bun is present. The flat back of the head may have held a separately carved bun as is traditional on the other seated figures, or it could have held a more elaborate horn and plumed headdress.

Two holes beneath the highly stylized ears suggest that a necklace or other head ornament was attached to the sculpture. The left shoulder is covered with a cloak decorated with trefoil, double circle and single circle designs that were originally filled with red pigment. Drill holes in the center of each circle indicate they were made with a specialized drill and then touched up with a chisel. Eyes are deeply incised and may have held inlay. The upper lip is shaved and a short combed beard frames the face. The large crack in the face is the result of weathering or it may be due to original firing of this object.

Material: white, low fired steatite

Dimensions: 17.5 cm height, 11 cm width

Mohenjo-daro, DK 1909

National Museum, Karachi, 50.852

Marshall 1931: 356-7, pl. XCVIII

Dimensions: 17.5 cm height, 11 cm width

Mohenjo-daro, DK 1909

National Museum, Karachi, 50.852

Marshall 1931: 356-7, pl. XCVIII

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

May 19, 2017

Pearl millet in the field.

Pearl millet in the field.

In front of a soldier, a

In front of a soldier, a

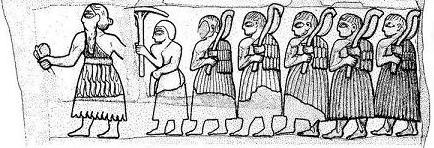

Rein Rings atop the shaft of the ceremonial 'chariot' (sledge) found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb. valgā f. ʻ bridle ʼ Mr̥cch. [S. L. P. poss. indicate earlier *vālgā -- ]

Rein Rings atop the shaft of the ceremonial 'chariot' (sledge) found in Queen Pu-abi's tomb. valgā f. ʻ bridle ʼ Mr̥cch. [S. L. P. poss. indicate earlier *vālgā -- ]

9:40 AM, May 19, 2017

9:40 AM, May 19, 2017

''"

''"

Storage jar

Storage jar  Mohenjo-daro storage pot c.2700 to 2000 BCE.

Mohenjo-daro storage pot c.2700 to 2000 BCE.

In the centre of each platform, a large storage jar of the type shown on Harappa tablet h1393a might have been as the centre-piece of merchandise offered in the market street of Harappa. It is possible that there was a canopy atop each circular platform making it a marketing hut of the artisan.

In the centre of each platform, a large storage jar of the type shown on Harappa tablet h1393a might have been as the centre-piece of merchandise offered in the market street of Harappa. It is possible that there was a canopy atop each circular platform making it a marketing hut of the artisan.

h1198b

h1198b

Santali glosses

Santali glosses

m1177, m0300 Mohenjo-daro seals ligature a human face to the trunk of an elephant.This epigraphy model provides the framework of an artistic style in iconography of

m1177, m0300 Mohenjo-daro seals ligature a human face to the trunk of an elephant.This epigraphy model provides the framework of an artistic style in iconography of

Gaṇeśa, Pārvati

Gaṇeśa, Pārvati

Slide 63 Elephant trunk ligatured to a winnowing fan

Slide 63 Elephant trunk ligatured to a winnowing fan

Banawari. Seal 17. Text 9201. Hornd tiger PLUS lathe + portable furnace.

Banawari. Seal 17. Text 9201. Hornd tiger PLUS lathe + portable furnace.

Why is a 'dancing girl' glyph shown on a potsherd discovered at Bhirrana? Because, dance-step is a hieroglyph written as hypertext cipher.vi

Why is a 'dancing girl' glyph shown on a potsherd discovered at Bhirrana? Because, dance-step is a hieroglyph written as hypertext cipher.vi