We decided to undertake a thorough examination of the article and share our observation, for, unless responded to, the plethora of such research, considered as fringe half a century ago, might end up becoming mainstream and that would be a grave injustice to India – the land and its people. For reading convenience, the original article has been kept in red and our response is given in blue.

It’s no big news that contemporary India is brazenly partisan about its national heroes, especially the ones who tower over the subcontinent’s history..

Every country in the world is proud to the extent of being brazenly partisan about its national heroes. It is surprising that the article would fault contemporary India for the same.

But few figures have elicited as much contempt from a section of the public as well as the political class as the Mughal emperor Aurangzeb

Yes, few figures have elicited as much contempt as has Aurangzeb. But the fear and disgust for him is not a modern phenomenon. These remarks are based on the book (Aurangzeb: The Man and the Myth, 2017 by Audrey Truschke) which the article praises. We have read the book and it claims that Aurangzeb’s image as a bigot was a British colonial construction

Such ideas filtered to society at large via textbooks and mass media, and several generations have continued to eat up and regurgitate the colonial notion that Aurangzeb was a tyrant driven by religious fanaticism [1]

This claim does not hold true in the light of contemporary testimonies. Let us examine how a ‘section of the public’ perceived Aurangzeb in the pre- colonial period.

- Pranami (Sant) tradition Pranamis follow a syncretic tradition and go beyond sectarian identities such as Hindu and Muslim. This sect honours both Gita and Quran in its temples and freely quotes from Quran, Bible and Gita. Mahatma Gandhi, whose mother belonged to this sect, and who himself was possibly influenced by these ideas, had the following words to say in his autobiography about Pranamis

Pranami is a sect deriving the best of both the Quran and Gita, in search of one goal – God

According to the 17th century Bitak Sahitya composed by Pranamis, Aurangzeb was a typical bigot who tortured Hindus, slaughtered cows and destroyed temples. Pran Nath, the founder of the sect, stayed in Delhi for sixteen months to meet Aurangzeb. He tried to reason that both the Hindu and Muslim scriptures had the same essence and led to the same truth. However, Aurangzeb declined to pay any heed to such appeals and refused any interview with him. He further imprisoned Pran Nath’s disciples and made a condition that they would be released only if they surrendered to Shariat [2].

The contemporary Pranami sects viewed Aurangzeb as a bigot who prosecuted Hindus

- Nek Rai This Persian poet of Aurangzeb’s time was a disciple of the Chishti Sufi order and made frequent pilgrimages to the hospice of Bakhtiyar Kaki. He has described how Aurangzeb broke the temple at Mathura and replaced it with a mosque. He disapproved of Aurangzeb’s bigotry and said this in a verse

Look at the miracle of my Idol House O shaikh That when it was ruined it became house of God

Nek Rai also said that looking beyond bigotry was the need of the hour as both Hindu and Muslim scriptures speak the same truth.

This clearly shows that Aurangzeb’s bigotry was looked down upon even by those people deeply connected to Indo Persianate world following sufi traditions.

- Shah Abdul Aziz Dehlavi He was one of the greatest Islamic scholars of Hadith in the 18th century. Writing in c.1780, he tells us about an event that occurred in Delhi during Aurangzeb’s time. The Shias of Delhi made Panja Sahib a place of pilgrimage.

When Aurangzeb came to know about it, he immediately issued orders for the demolition of the place. Shah Dehlavi clearly saw Aurangzeb as a Sunni puritan who destroyed Shia places of worship.

- Dasam Granth Bachitar Natak of Dasam Granth written (c.1690) describes how Aurangzeb dealt with civilians who had come to pay respects to the Sikh Guru.

Their houses were plundered, wealth destroyed, their heads shaven, urinated upon, publicly paraded, jeered upon, beaten with shoes and finally sent to death [3].

Pre- colonial Sikh tradition (Sri Guru Panth Prakash) ascribes the “martyrdom” of Tegh Bahadur to the bigotry and religious persecution of Aurangzeb. This scripture was written in the early nineteenth century when there were no English institutions in Punjab which was ruled by Maharaja Ranjit Singh.

Whether or not this episode is mentioned in Persian primary sources, this tradition was current among Sikhs even before British took over Punjab

- Nirvanis of Benaras The Nirvana Akhara of Benares have in their records an incident that in 1664, Aurangzeb sent an Army to destroy the Vishveshwar temple. The Nirvanis fought and defeated the armies of Aurangzeb, thus protecting the temple which was later demolished by him in 1669.

![]() Gyanvapi Mosque built in 1669 CE by Aurangzeb on top of the great Vishveshwar temple

Gyanvapi Mosque built in 1669 CE by Aurangzeb on top of the great Vishveshwar temple- Atrocities against Shias Shia traditions of the sub-continent have seen Aurangzeb as a bigot. We illustrate this fact by examining the traditions of northern and southern encompassing ends of Indo Shia world- Ladakh and Hyderabad. Among Shias of both Ladakh and Hyderabad Aurangzeb is a byword for sunni persecutions [4].

In Kashmir, Aurangzeb’s reign saw Shia persecution. Hasanabad, a Shia colony, was torched. Aurangzeb executed a Kashmiri Shia Husayn Malik on charges of blasphemy as he was alleged to have insulted companions of prophet. A song has been sung ever since by Kashmiri Shias commemorating this event

Because of the atrocities of Yazid’s community,

Husayn son of Haydar has been martyred again

In Hyderabad, Aurangzeb is notorious for converting Shia Royal Ashurkhana (chamber for Shia prayers and ritual) into a garage.

![]() Royal Ashurkhana

Royal Ashurkhana The Shia historian Sadiq Naqvi asks

Explain to me about when Awrangzîb attacked the Deccani sultanates, when he ordered the Shîcî shrines to be destroyed! I can show you the firmân [official order]! For what crime were these shrines destroyed? But the modern period of history is not very different in this respect. Who are the enemies? In this time, the same things are being repeated as in the earlier period [5]

- Hindus of Benaras In 1809, before English educational institutions were established in Benaras, there were Hindu-Muslim riots after the pillar of Lat Bhairav was demolished. The Hindus of Benaras submitted a petition to the British wherein they blamed Aurangzeb for fomenting communal strife in the city by destroying temples and converting them to mosques.

All had been well in Banaras, until the Emperor Aurangzeb had destroyed the harmony between the communities by demolishing a temple; but the Emperor was so powerful that the Hindus had ‘necessarily submitted with patience’.

This episode again elucidates how Hindus of the pre-colonial and early colonial age viewed Aurangzeb.

- Hindus of Kashmir Hindu historian Bahadur Singh’s account of the history of Kashmir (c. 1824) based on earlier texts in addition to his own sources, recounts many examples of the rape and murder of Kashmiri Hindus by Muslim soldiers and gangs of insurgents over the centuries. Under Aurangzeb, he says,

‘ten seers’ (twenty pounds) weight of sacred threads (the symbol of high caste status) were collected from forcibly converted Hindus, many of whom were later to ‘reconvert’ to Hinduism[6]

This book was written three decades before colonialism found its way to Kashmir.

- Hindus of Kumaon Bahadur Singh also claimed that the females of Kumaon, on the mountainous northern borders of the Empire, were regularly consigned to brothels when their men failed to pay revenue

- Sufis of Bijapur Aurangzeb’s self-proclaimed Jihad against Bijapur had disastrous consequences. Many Deccani Muslim poets lamented the bad state of incomes and the economy in Bijapur and Golkonda in the troubled times following their fall. A pre-colonial Sufi writing attributes the cholera epidemic that struck the Bijapur plateau as

bud waba’ az Mughal — “the cholera came from the Mughals[7].”

A census of Bijapur taken on behalf of Aurangzeb showed that the city had lost over half of its former population in the few years after his conquest. The Bijapuri Sufi Ansari fled Bijapur to his native place Gogi noted that if he were to return to Bijapur he would be put to death. The Sufi Bahri wrote in his own account how the Mughals officers inspected and persecuted him on the allegations of heterodoxy.[8]

- Astrologers of Gujarat Aurangzeb became extremely unpopular after the introduction of Jaziya so much so that earthquakes were attributed to him and in 1684 astrologers of Gujarat predicted the demise of Aurangzeb following a series of earthquakes.

Such a prediction would not likely have been made about a loved and admired king.

- Jains of Agra In a contemporary Jain work written in Agra c.1676 CE, “Aurangzeb was not accepted as king”. The historian who examined this manuscript observes

Aurangzeb was reigning in 1676, his name has NOT been mentioned as the ruling king. Though dead, Shãh Jehãn was still deemed to be the real sovereign (‘ chakravartin’) of the country. This shows that the ‘ Chakravartin’ status, granted by the native intellectuals to Akbar, Jehãngir and Shãh Jehãn, was discontinued, and that Aurangzeb was not accepted as such by them, obviously, owing to his iconoclastic measures against the ‘ Dharma ‘. It was regal derision or reproach, like the modern Parliamentary reprimand and an intellectual refutal of the Kingship of Aurangzeb [9]

In her book, Audrey quotes laudatory descriptions of Aurangzeb in vernacular Jain works to show that he ensured the well being of all his subjects. At this juncture, we would simply like to submit that many contemporary subjects wrote favourably of Stalin and Hitler, too!

Aurangzeb’s legacy, in the popular imagination, is one of unmitigated tyranny — reviled as the destroyer of Hindu temples, executioner of Sikh guru Teg Bahadur, and an austere Muslim ruler, who imposed unpopular taxes and curbed expressions of liberal Islam.

It is amusing that the author would blame the public and political class for showing contempt for someone who has been found to be responsible for the genocide of 4.6 Mn Indians according to a Pew research report based on Manucci’s account of Aurangzeb’s reign Audrey answers to this charge by saying that though Manucci remains a useful source, he should be read critically and with caution.

Ignoring the corroboration by Dutch records, she even tries to lay the blame of this genocide on the shoulders of Marathas for scorched earth policy in defending their own land from Aurangzeb’s invasion.

This is akin to one blaming an owner who defends his house against thieves.

If Adolf Hitler is looked down upon with contempt and rightly so, why would the author want to excuse Aurangzeb?

In 2015, amid a raging controversy, the ruling government acceded to an extraordinary request from the New Delhi Municipal Corporation to have the name of Aurangzeb Road in the national capital changed to APJ Abdul Kalam Road. The idea was to remove the association of evil, represented by Aurangzeb, from the name of the street and replace it with the name of the former president of India, who, presumably, embodied goodness.

What exactly did the ruling government do to merit an uproar, one wonders! Nobody in India has desecrated his grave or destroyed his tomb. It is strange that someone who changed the name of so many sacred places of Hindus is being defended this way. Mathura and Chittagong both became Islamabad, Varanasi was renamed as Mohammadabad and Khirki was changed to Aurangabad, to cite a few examples.

The article finds no substantiation for Dr Kalam’s goodness despite his personal and professional conduct being well recorded and not so far back in the past. And ironically, at the same time, uses unsubstantiated rhetoric to claim that Aurangzeb was not a Tyrant and a Bigot that his actions, recorded in documents from the past, clearly reveal him to be.

The hatred for Aurangzeb also comes through in his denunciation by the Shiv Sena and other groups that admire his arch-rival, the Maratha warrior, Shivaji. In 2004, a biography of Shivaji by James Laine was banned in Maharashtra because it had dared to raise questions deemed unseemly by his fans. In 2015, a Shiv Sena MP abused an officer on duty on camera by calling him “Aurangzeb ki aulad” (a descendant of Aurangzeb), after he razed some temples during a demolition drive sanctioned by the district collector in Aurangabad, based on high court orders.

We have already established that Aurangzeb was a reviled figure. And it is not because of some propaganda by any political party. Yes, Shiv Sena and other groups admire Shivaji, the nemesis of Aurangzeb. But this admiration for Shivaji is not a new found 21st century phenomenon! He was admired even back in the 19th century Colonial Bengal where Shivaji Jayanti used to be conducted every year.

Historian Audrey Truschke took it upon herself to write a biography of Aurangzeb for the common reader to disabuse them of the many misconceptions around the Mughal king. At a little over 100 pages, without the paraphernalia of footnotes, it is as accessible as a complex historical narrative can get, without losing its essential core of erudition.

All the sources cited in the book have been known for years. There is not a single new source that has been used in the book. Thus, it is no pioneering work. All that the book does, is reinterpret existing sources in a contrarian manner to fit the theory or narrative where Aurangzeb is expected to be remembered as a mango loving, cap selling devout Muslim instead of the perpetrator of a genocide of Indians!

As Truschke says in the Preface, the idea for the book, fittingly, came to her in an exchange on Twitter, a minefield for peddling divisive political agenda by interested groups and individuals. The spirit of the book, with its crisp prose and controlled polemics, hits out at the easy generalisations of social media.

Dr Konrad Elst, a historian and scholar of repute, has written about how scholars who do not share Left ideology have been systematically denied opportunities, over the years. And how Academia is dominated with scholars who label anyone not agreeing with their left leaning ideology as ‘having some agenda’. With this background, the section above sounds more like a left liberal SJW complaining about the equal freedom of speech that Social Media offers to everyone without fear or favour! Aurangzeb’s life, widely misrepresented by the Hindutva brigade as that of a cardboard despot’s, was far more complex, as anyone with common sense would expect, as well as riddled with many contradictions. Those who are familiar with politics should not be surprised by the persistence of the latter either.

The last of the so-called ‘Grand Mughals,’ Aurungzeb, tried to put back the clock, and in this attempt stopped it and broke it up.

—Jawaharlal Nehru

Seeds of Partition were sown when Aurangzeb triumphed over [his brother] Dara Shikoh. – Shahid Nadeem, Pakistani Playwright

Even Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the father of Pakistan, observed that

Aurangzeb presided over a conquest state where Hindus had to submit to his rule most unwillingly[10]

None of these individuals would qualify to be a part of the Hindutva brigade. This attribution of Aurangzeb’s portrayal in popular memory, as something misrepresented by the Hindutva brigade, is unsubstantiated.

Even Audrey Truschke’s tutors and seniors in her own academic circles have differed with her views on Aurangzeb. Her undergraduate advisor Wendy Doniger , who she holds in high regard, is renowned as one of the greatest critics of Hindutva.

She has said this about Aurangzeb

The Hindus suffered most under Aurangzeb. In 1679, he reimposed the jizya on all castes (even the Brahmins, who were usually exempt) and the tax on Hindu pilgrims that Akbar had lifted. He rescinded endowments to temples and to Brahmins, placed heavier duties on Hindu merchants, and replaced Hindus in administration with Muslims. When a large crowd rioted in protests the jizya, he sent in the troops—more precisely, the elephants—to trample them. He put pressure on the Hindus to convert.

Does Doniger’s statement also amount to “misrepresentation by Hindutva brigade”?

A successful statesman must act expediently, even though their actions may not always square with their professed political ideologies. (Consider the Bharatiya Janata Party’s stance on beef, for instance, which seems to keep changing according to populist demands in different parts of the country.)

Why should a piece on Medieval History include a comment on a political organisation? Is this book by a Historian or someone with political backing and inclination?

Aurangzeb, who took on the title of Alamgir (“the seizer of the world”), was no exception. His actions were in accordance with what he imagined to be that of an effective and equitable ruler’s. His understanding of justice was never meant to live up to postmodern notions of human rights. To impose on him the standards of the modern world is to thus make a grave historical error. He remained a truly Machiavellian ruler in the classic sense of the term, drawing on The Prince, a treatise by the Italian diplomat Niccolò Machiavelli who advised rulers to imbibe cunning in their personal conduct and art of statecraft.

Aurangzeb’s actions were not merely in accordance with what he imagined to be that of an effective and equitable ruler’s. These were completely aligned with his idea of a true Muslim. We agree that his understanding of justice is not expected to live up to the postmodern notions of human rights. Can we expect Aurangzeb to have acted at least like the earlier Mughal emperors or would that also amount to, what the article claims to be, a grave historical error?

It is an established fact that his standards of justice took a complete break from his predecessors such as Akbar who implemented Sulh-e-Kul. Even his son Prince Akbar fares better than him who is supposed to have written to his father

On the Hindu community [firqa] two calamities have descended, the exaction of jiziya in the towns and the oppression of the enemy in the country.

Looking at his contemporaries, we find that he did not even show the same characteristics as Shivaji. The deplorable condition of natives under Mughal invaders and their descendants is documented in various sources. And it is in complete contrast with how Shivaji treated his subjects. Kavi Bhushan, who was not a Maratha, mentions how Shivaji uplifted the enslaved Hindus. Kavi Bhushan, a Bundela poet from North India was an admirer of Shivaji and considered him to be the uplifter of suppressed Hindus. This itself makes for an interesting case, for, according to Audrey, there was no Hindu identity in pre-colonial age. How a person from UP could praise Shivaji as the uplifter of Hindus in the absence of any identity is beyond one’s imagination?

Even if we were to ignore the writing of a native such as Kavi Bhushan, we have Aurangzeb’s biographers, who were not Shiv Sainiks, expressing admiration for Shivaji.

Khafi Khan, a rival of Shivaji, who called Hindus dogs said

But he (Shivaji) made it a rule that whenever his followers were plundering, they should not do harm to the mosques, the Book of God (Quran), or the women of anyone

Aurangzeb presided over the creation of Fatawa-i-Alamgiri , the most important source book for Muslim law in India which has the following rules about manumission of slaves

Manumission can be done orally or in writing, but it has to be done in accordance with rules and in proper form and proper words. Captured slaves, if kafirs, could not be freed.6 To be kafir is a disqualification (aib) both in ghulam (male slave) and bandi (female slave). The Muslim detests the company of kafirs because the object, in the purchase of a female slave, is cohabitation and generation of children

Once a slave converts, there is provision for his freedom. If a slave apostatizes, he cannot be freed until he returns to Islam. An exposition of the faith is to be laid before an apostate; who, if he repent not within three days is put to death. A female slave or free woman who apostatizes is not to be killed, but she must be daily beaten with severity until she return to the faith. 10 A Musalman slave, purchased by an infidel, becomes free after entering an infidel territory. The slave of an infidel, upon becoming Musalman, acquires the right to freedom.

Aurangzeb put this law code to practice when he prevailed upon Portuguese pirates to release captured Muslim slaves but approved capture of Hindu slaves.

By contrast, Shivaji implemented a strong prohibition against slavery of anyone irrespective of religion within his jurisdiction since

“ [he] has established [as] a fundamental rule of his government, that none of his subjects may be made into slaves, let alone be sold or transported, in order not to lack any inhabitants, with which these new conquests are sparsely enough provided, even though this tyrannical rule has already made many of the best inhabitants leave”.

Aurangzeb threatened his generals that he would rape their wives whereas Shivaji implemented a rule that women should not be harmed when his soldiers went plundering.

Aurangzeb demolished temples whereas Shivaji refrained from destroying places of worship of people from other faiths. He even donated to the Dargah of Muslim Sufi of Baba Yakut.

Aurangzeb levied discriminotory taxes including Jaziya taxes on non-muslims. The trade tax for Muslims was 2.5% as against 5% for Hindus. Shivaji did not discriminate.

A snapshot comparing the two is given below.

Common sense and basic humanity suggests that killing 4.6 Mn people is Macabre and not Machiavellian.

Just as it is true that Aurangzeb imposed the oppressive jizya tax on non-Muslims (in spite of opposition from within the court and the royal family), he also elevated Hindu officials to positions of eminence in his court. While he did destroy temples during his reign, the number was probably no more than a dozen.

Here the article is forced to mention Jizya as no amount of whitewashing can do away this clear manifestation of inequitable conduct. Jiziya is unarguably one of the most humiliating acts against the human spirit. Aurangzeb followed it, for, he believed that it was prescribed in Islam. His biographer Khafi Khan wrote this some time after Aurangzeb’s reign had ended,

the imposition of the tax was done, “with a view to suppress the infidels, and make clear the distinction between the dar ul-harb en de muti‘ ul-Islam,” that is between the rebellious areas and the areas that were muti‘, obedient or submissive, to Islam.

And in order to balance out the monstrosity of this unfair, unjust act, the author tries to create an impression that Aurangzeb also elevated Hindu officials to positions of eminence in his court.

The truth is that the number of Hindu Mansabdars grew in Aurangzeb’s time, apparently, on account of the rise of Hindu scribal groups and the need to include locals, familiar with the lay of the land, who had deserted the Marathas. This step, taken by him out of desperation, for, he was not able to make gains on his own, was resented by orthodox Muslims who cursed him to hell. However, it is to be noted that similar growth in Hindu scribal groups was also witnessed in the Islamic Deccan kingdoms of Golconda and Bijapur.

However, there was a clear “glass ceiling” to the rise of Hindu Mansabdars under Aurangzeb. When the Rajput Jai Singh was appointed as the deputy in Malwa in 1705, Aurangzeb wrote that a Hindu could not ordinarily be given the position of Governor or even that of Faujdar. It is to be noted that everyone had to pay Jaziya with the added humiliation of having to kneel to the Kazi while paying the same.

The author very kindly forgives destruction of Temples by saying that the number was probably no more than a dozen. The fact is that Aurangzeb’s iconoclastic frenzy led to the destruction of thousands of Temples as can be seen from imperial records and historiographies (ref: Table below). And this is not all, for, epigraphical records also reveal instances of mosques built on temples during his . Examples are the Jami Masjid at Gwalior and Pattar ki Masjid at Patna. How many Temples were destroyed but unattested in epigraphy and historical records? We simply will never know. All we know is that only a few Temples have survived Aurangzeb’s reign and most of north India was deprived of large Temples.

Hindu Reaction to Aurangzeb’s Iconoclasm

Here we examine the effect of Aurangzeb’s temple demolition on Hindu psyche through the reaction of Hindus to his spree of iconoclastic measures.

Temple legends Many Hindu temples were ruthlessly demolished during Aurangzeb’s reign.

The temples that survived, either fully or partially, were considered to have had miraculous powers, for, surviving Aurangzeb was no less than a miracle.

- Prominent in this class of temples is Karmanghat Hanuman temple in Hyderabad. According to a Hindu legend, Aurangzeb sent his men to destroy this temple after conquering Golconda. When they tried to enter the temple, they were pushed back by some strong force and could not enter. Upon hearing of this incident, Aurangzeb himself came down to destroy this temple. He too could not enter the temple and he heard voices which said, “If you want to enter this temple, make your heart stronger(Karo-man-ghat)”. Aurangzeb asked the voice to prove its truthfulness, which resulted in lights all around with the appearance of the form of the lord. This is how the place came to be called as Karmanghat.

- Another temple that has “miraculously” survived Aurangzeb’s iconoclasm is the Jeen Mata temple in Sikar, Rajasthan that Aurangzeb wanted to raze to the ground .Being invoked by her priests, the Mata let out its army of Bhairons (a species of fly family) which brought the Emperor and his soldiers to their knees. He sought pardon and the Kind hearted Mataji excused him from her anger.

- Similarly, Sthal Purana of the Shiva temple at Jangamwadi states that Aurangzeb was put to flight by heavenly host of Lord

- The Khandoba temple at Jejuri has a tradition that an attack on it by Aurangzeb was foiled by the deity. Similarly, K N sane in Varshik Itibritta (saka year 1838) records that the attack by Aurangzeb on Narsinghpur was foiled by snakes and scorpions

Temples that have partially survived Aurangzeb’s iconoclasm have also been attributed miracles.

- There is a legend that when his soldiers wanted to destroy the Gaurishankar temple, they attacked the Shiva Linga with a spear. Fountains of blood appeared from the Shiva Linga, and the soldiers ran away, terrified. One can still see the mark of the spear on the Linga.

- Chand Khedi temple in Kota(Rajasthan) has a legend that, during the time of the Mughal invasions, a blow from an invader’s axe damaged the toe of the Rishabhdev temple idol, resulting in a flow of milk which swept away the invaders and kept the temple safe.

- According to Kedara Temple Sthal Purana, Aurangzeb’s troops approached the vicinity of the Kedāra Temple in Benares and were met by a Muslim holy man who warned them not to touch Kedāra. The commander paid not heed. He stormed into the Kedāra Temple and slashed with his sword at the image of the bull Nandin, kneeling before the doorway to the sanctum. Real blood, it is said, began to flow from the neck of the stone Nandin, and the Muslim assailants backed away in awe

![]()

Ruins of Chausath Yogini temple destroyed by Aurangzeb

Idols of Chausath Yogini temple destroyed by Aurangzeb

There is an interesting story behind the Chausath Yogini temple in Jabalpur. Aurangzeb once decided that he would kill anybody who did not make a sound when his sword was put on him. When he came to the Chausath Yogini temple, he put his sword on every Yogini idol and destroyed each , for, no sound was heard. In the end, he went to the idol of Lord Shiv-Shakti. As soon as he put his sword on Lord Shiva’s leg, he heard the sound of bees and flow of milk from his leg and decided not to damage the idol.

There are other temple traditions which attest to the iconoclasm of Aurangzeb. These traditions are about priests relocating idols to escape Aurangzeb’s Jihadi fury.

- It is believed that the original linga of Varanasi was secretly smuggled to the Temple of Guptakashi in Uttarakhand.

- According to a tradition, the temple of Bhavani Mandap at Kolhapur houses the image of Goddess Tulja Bhavani secretly smuggled to prevent demolition.

- Srinathji was shifted from Mathura to safeguard it from, according to legend, the Mughal ruler and installed in a temple there under the rule and protection of the then Maharana Raj Singh of Mewar.

Other Hindus were defiant.

- An inscription from Ranganatha Swamy temple at Nirthadi states that the temple was rebuilt in 1698 by Baramappa Nayaka after its destruction by Aurangzeb in 1696.

- When Aurangzeb ordered demolition of Laxmi Narayan temple of Chamba in 1678, Raja Chattra Singh, instead, gilded its pinnacles.

- In 1671, a Muslim officer sent to demolish temples around Ujjain was killed by Rajputs along with his 121 men. He had succeeded in demolishing a few temples before being overpowered by them.

Whether we believe the legends etched into the Stahal Puranas of these temples, these instances do indicate that Aurangzeb’s iconoclasm led to huge destruction and resettlement of Hindu places of worship.

Until 1669, Aurangzeb was only upholding Hanafi law which was prevalent even in the days of Shahjahan, according to which all newly constructed Temples had to be demolished and while older ones were not be demolished, these could not be repaired. But he did break this law as the table below shows.

In 1669, he issued orders for general demolition of all Temples, including the holiest ones such as Vishvanath in Varanasi, Somanath in Prabhasa and Keshav Rai in Mathura. When Aurangzeb invaded Orissa, he demolished all other Temples but left Puri Jagannath intact because he thought it was a source of great revenue for Mughals. Similarly, Tirupati was spared.

An 1850 sketch of Somnath temple. Mosque elements (dome and minarets) piled clumsily on top of the ancient temple by Aurangzeb’s forces

Mosque built by Aurangzeb on top of Gobind Dev temple, Vrindavan. Sketch by James Fergusson

Table: A list of demolition and destruction of Temples carried out by Aurangzeb

Here are few more documented facts

![]()

- One mosque at Benares was built by Aurangzeb on the site of the Bisheshwar Temple –a tall temple considered holy by Hindus. He constructed a lofty mosque on the site of the temple using the stones from the temple structure.

- He also demolished Krittivasa and Bindu Madhava temples, raised mosques in their stead.

- He built Alamgiri mosque on top of Beni Madhav temple.

- Similarly, a pillar of old Lat Bhairav temple survives in the midst of a mosque. This pillar once stood in a Hindu temple complex, but in the time of Aurangzeb the temple was destroyed and the site became a Muslim tomb site. The pillar, however, was wisely left intact, as Sherring put it, “either as an ornament to the grounds, or under a wholesome dread of provoking to too great a pitch the indignation of his Hindu subjects.” Muslims continued to permit some access to the pillar and received part of the offerings in return. As a result, there is no major religious sanctuary in all Banāras that pre-dates the time of Aurangzeb in the seventeenth century.

In 1669 CE, Aurangeb destroyed Bindu Madhav temple and built Alamgiri Mosque on top of it

- He built a mosque at Mathura on the site of the Gobind Dev Temple which was very strong and beautiful as well as exquisite.

- Maisaram Masjid was built by Aurangzeb from the materials of 200 temples demolished after the fall of Golconda • Masjid of Aurangzeb in Rohtasgarh, Shahabad District, Patna was a part of a temple converted

- 17 Masjids were built by Aurangzeb in Hubli, Karnataka in 1675 on Temple sites

- Masjid built by Aurangzeb in Udaypur, MP used Temple materials

- A Persian inscription discovered in the Jãmi Masjid at Ritpur in the Amravati District of Maharashtra proclaims that the mosque which was originally built by Aurangzeb on the site of a Hindu temple, having become desolate through passage of time, was reconstructed in AH 1295 (AD 1878) with the help of contributions raised by the local Muslims

- Maqbara of Aurangzeb in Aurangabad is built on a Temple site

- Masjid built in Aurangzeb’s reign in Ramtek, Nagpur District is a converted temple

- Masjid built by Aurangzeb in Fyzabad District, Uttar Pradesh on Swargadvãra Temple site

- Masjid built by Aurangzeb Tretã-kã-Thãkur Temple site

In addition to the above, we have other instances where the dates are not definitely known.

- The Juma Masjid at Irach in Bundelkhand, built in his reign seems to have been built using material taken from a Hindu temple.

- It is also said that he ordered the demolition of a Saiva temple which he saw while passing through Udaipur in Bundelkhand (about 1681). However, the order was later modified and the temple converted into a mosque.

- The temples at Gayaspur near Bhilsa and the temple of Khaundai Rao in Gujarat were also destroyed on his orders.

- Aurangzeb destroyed the temples at Mayapur (Haridwar) and Ayodhya.

- He also stopped public worship at the Hindu temple of Dwaraka.

![]()

Ruins of Bhima Devi Temple

- Bhima Devi temple complex was destroyed by Aurangzeb’s foster brother who built Mughal gardens in their stead in 1666 CE at Pinjore

![]()

![]() Mughal Garden, Pinjore

Mughal Garden, Pinjore - A newswriter of Ranathambore reported the destruction of a temple in the pargana of Bhagwant Garh in the state of Jaipur. • Bakhtawar Khan, who was in Aurangzeb’s court, says this in “Mir’at-i-Alam”

All the religious structures of infidels and great temples of these infam

ous people have been thrown down or destroyed in a manner which excites astonishment at the successful completion of so difficult a task. His Majesty (Aurangzeb) personally teaches the sacred kalima to many infidels with success. … All mosques in the empire are repaired at public expense…

- Aurangzeb’s court records (Akhbarat-i-Darbar) talk about the destruction of hundreds of temples in Udaipur.

- An undated order mentions the destruction of every temple built in the last 12 years and not repair any old temple. This order was issued to the governor of Orissa.

- Aurangzeb also partially destroyed the temple of Sitaramji at Soron.

![]() Sitaramji temple Soron;Destroyed by Aurangzeb

Sitaramji temple Soron;Destroyed by AurangzebAurangzeb’s soldiers destroyed the Devipatan temple in Gonda(UP) and slew the priests therein

![]() Ruins of Harshnath temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1679

Ruins of Harshnath temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1679![]() Ruins of Harshnath temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1679

Ruins of Harshnath temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1679![]() Someshwar Temple(Rajasthan). Destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1680

Someshwar Temple(Rajasthan). Destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1680![]() Bhuleshwara temple ruined by Aurangzeb

Bhuleshwara temple ruined by Aurangzeb![]() Idgah mosque built by Aurangzeb over Keshav Rai temple in Krishnajanmabhoomi complex. Mathura, 1670

Idgah mosque built by Aurangzeb over Keshav Rai temple in Krishnajanmabhoomi complex. Mathura, 1670Alamgiri Mosque built by Aurangzeb after destroying Hanumangarhi temple of Ayodhya

Given the long list, it is no wonder that in her book Audrey talks of “few dozen temples“ destroyed by Aurangzeb even as the Huffington post author stays stuck on “no more than a dozen”

In most instances, he ordered the razing of religious sites or their desecration with the aim of teaching his subjects a lesson for transgression or inciting revolts. Any monarch, who wanted to ensure the continuance of his reign, was unlikely to have acted differently under the circumstances.

One wonders if we shall soon be reading similar research to explain away Hitler and the Holocaust as teaching the ‘subjects a lesson’!

This theory of political iconoclasm is unable to explain that if desecration and destruction of Hindu Temples was simply driven by politics, how is it that the mosques in the opponents’ lands escaped similar treatment.

The historian Richard Eaton has tried to put up a theory that Hindu temples were places of revolt while as Mosques were above politics. Now this theory is highly flimsy as reading Khutba in the name of the Emperor was a Friday ritual in the mosques.

State religion and state politics were inseparable in Muslim rule. As an example, we can talk about an incident that happened right after the death of Aurangzeb. When Bahadur Shah proposed some changes in the Khutba, people suspected that he had modified the prayers because he was sympathetic to Shias. The Lahore mosque refused to read this Khutba and acknowledge Bahadur Shah as the sovereign.

Now if the theory of political iconoclasm was correct, Bahadur shah should have destroyed this mosque right away. He even trained his guns at it. But he finally had to capitulate on the plea that destruction of mosques would incur him wrath. The very fact that a mosque could not be touched even when there was an open political rebellion within the same, against the imperial regime, shows that the theory of political iconoclasm hold no merit.

As against this, there is no recorded evidence of a Hindu parallel for Khutba reading in a temple.

When Aurangzeb invaded Bijapur, the Khutba in the mosque was read in the name of King Sikandar Adil Shah. If the theory of political iconoclasm were correct, he should have destroyed this mosque but he did not. Instead he donated to this mosque and to others shrines such as the one at Gesu Daraz which had been associated with the polity of Bijapuri Adil Sahis.

The whole theory of political iconoclasm falls flat when one considers the case of Shantidas Zhaveri. Shantidas Zhaveri was a rich Jain merchant and a close associate of Mughals. The non-violent Jain merchants of Gujarat were never known to foment violent political rebellions anyway. But Shantidas was dear to Shahjahan. Young prince Aurangzeb demolished Chintamani Parshvanath temple built by Shantidas Zhaveri in Ahmedabad. He slaughtered a cow inside its premises and converted it into mosque. When Shahjahan came to know about, he handed the temple back to Shantidas Zhaveri. But the Jains did not take back the temple as it had already been desecrated. Later, Shantidas Zhaveri sponsored the campaign of Murad when he allied himself with Aurangzeb rebelling against Shahjahan and Dara Shikoh. After he became the king, Aurangzeb maintained friendly relations with Shantidas Zhaveri and assigned him some land in Shantrunjaya.

With this the statement that Aurangzeb “destroyed temples as a lesson for revolts” falls flat on its face. Clearly, Shantidas was not inciting any revolt and it was not the imperial policy to destroy his temple as Shahjahan’s reaction shows. Shantidas was a much sought after friend of both Shahjahan and later, Aurangzeb, and this action simply cannot be attributed to any politics. Aurangzeb did it out of pure religious bigotry. No sophistry can explain his action.

As if that was not enough, Aurangzeb in his last year (1707) ordered demolition of temple at Purandhar, in Maharashtra, simply because his own soldiers worshipped idols inside it! This was not his own army, these were not rebels! No theory of political iconoclasm can explain this fact.

The fact is that Aurangzeb himself cited Islamic precedents for iconoclasm and sincerely believed that it was his duty as a pious Muslim to destroy idols. When demolishing Hindu Idol temples, Aurangzeb quoted “has the truth not come, has the falsehood not vanished”? (Quran 17.81). This saying is famously attributed on the authority of Hadith of Sahih Al Bukhari to Prophet Muhammad when he was breaking the idols inside mecca.

And the order for general demolition of temples in 1669 clearly bears it out. It says

The Lord Cherisher of the Faith learnt that in the provinces of Thatta, Multan and especially at Benaras, the Brahmin misbelievers used to teach their false books in their established schools, and their admirers and students, both Hindu and Muslim, used to come from great distances to these misguided men in order to acquire their vile learning. His Majesty, eager to establish Islam, issued orders to the governors of all the provinces to demolish the schools and temples of the infidels, and, with the utmost urgency, put down the teaching and the public practice of the religion of these unbelievers” The order talks of “establishing Islam” and is directed against religious Brahmin teachers, not political rebels. Richard Eaton has argued that this order was confined to benares. But his words are proven wrong by the testimony of Degraaf. De Graaf, who was at hoogly in 1670 attests to the fact that Aurangzeb ordered destruction of temples everywhere in his reign “In the month of January [1670], all the governors and native officers received an order from the Great Mughal prohibiting the practice of Pagan religion throughout the country and closing down all the temples and sanctuaries of idol worshippers…in the hope that some Pagans would embrace the Muslim religion”

![]() Aurangzeb destroyed Charchika temple and converted it into Bijamandal mosque. C.1682 CE

Aurangzeb destroyed Charchika temple and converted it into Bijamandal mosque. C.1682 CEAurangzeb merely acted in line with the hallowed Mughal tradition of in-fighting, where brother didn’t hesitate killing brother in battles of succession, to come to power. In his case, he drove away one of his brothers from the empire, killed the other two, and kept his aged father, Shah Jahan, in house arrest. Had Aurangzeb not secured the kingdom for himself by such violent means, he’d have lost face among his contemporaries, and most probably his life in the hands of one of his brothers.

Looks like, in the author’s eyes, he could do no wrong! It is true that Mughals had the tradition of infighting but it was fratricidal. Aurangzeb took it to glorious heights by imprisoning his father! This displeased the Sharif of Mecca so much that he refused to accept his gift. The Chief Kazi of Delhi refused to announce Aurangzeb’s coronation saying that it was illegal as his father was alive. Shah Suleiman of Iran mocked his reputation by saying that he usurped his father’s throne which he refused by lying that his father had abdicated it voluntarily.

When read in the context of Mughal history, much of the aura of a “cartoon bigot” that social media trolls and right-wing politicians have imposed on Aurangzeb seems to fade away, leaving behind the impression of a king who was as human and fallible as any other.

The facts put forth by us clearly emphasise that the aura of Aurangzeb is not something concocted by social media trolls and right wing politicians. It is a result of authentic findings from contemporary and later primary sources.

There are peculiarly contemporary resonances with his reign. Aurangzeb, too, for instance, tried to impose prohibition, which proved to be a disastrous policy. An admirer of music in his early years, he turned into a strictly religious man in his tastes later in life. He never lost his appetite for satirical verse though, letting his court poets compose lines that dared to lampoon him.

It is strange that the author would find contemporary resonances with Aurangzeb’s reign. Let us look at all that he prohibited or put an end to, in addition to the lives of countless non-muslims, that is!

- He replaced the Persian Ilahi year with the Islamic Hijra year.

- In his second year he discontinued the celebration of Nauroz as it was a pagan or heretic festival.

- He dismissed singers from his court in his 11th year.

- Music and dancing (including musical parties) were forbidden. Sheikh Yahyat Chisti, a Sufi of Ahmedabad refused to capitulate and he was troubled by imperial agents.

- He discontinued the Hindu practices of Jharokha Darshan , Tula Dan.

- He dismissed Hindu astrologers and replaced them with Muslim astrologers.

- He imposed a ban on wine and if a wine seller was apprehended, he was whipped on the first offence and imprisoned on the second.

- Aurangzeb proscribed the poem of Hafiz (Diwan-e-Hafiz) in schools because he believed that it encouraged wine drinking.

- The allowable length of beard was fixed at 4 fingers. An army of men was mobilised which set out ascertaining the length of beards of people and cutting off the excess length.

- Garments of gold were forbidden.

Although he diminished the presence of Sanskrit scholars at the Mughal court, he also wanted Brahmins to pray for the safety and continuation of the empire. The Hindus were too diverse anyway (a composite of the Brahmins, Marathas, Rajputs and other castes) to bear down on him with a united hostility.

The author talks about patronage of Brahmins. A good example of how and why he patronised Brahmins can be gleaned from the episode of Jwalamukhi. When Aurangzeb attacked the temple of Jwalamukhi, he tried to wall the flames worshipped therein with metal plates, for, he considered these to be Satan’s tongues. This plating led to fire breaking out with full force, elsewhere. Then, the frightened Emperor made offerings to the Brahmins and hurried away.

If such examples are used by scholars to show that Aurangzeb was tolerant and secular, it is extremely unfair and dishonest.

In spite of grounding her narrative in historical facts,

LOL

Truschke brings to life Aurangzeb the emperor in all his flaws and splendour.

Truschke also brings to life a mythical Aurangzeb who invokes Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesh! In another review of her book, it is written Aurangzeb composed a poem in Hindi in which he invokes the blessings of Vishnu, Brahma and Mahesh on his accession (see Manager Pandey, Mughal Badshahon ki Hindi Kavita). Clearly, the emperor Aurangzeb was too multifaceted to be reduced to a single personal/religious identity

This article refers to a book by Manager Pandey in which it is claimed that Aurangzeb invoked the Trinity!Surprisingly, her book does not include it at all!

The poem, we found out, comes from Sangita Raga Kalpa Druma by Nagendranath Basu, published in 1914, who supposedly republished Krishnananda Vyasa’s Sangita Ragakalpadruma, first Published in three editions in 1842, 1845 and 1849, respectively.

One may wonder as to how did Aurangzeb’s “Hindi” poems find their way into a book published into a book first published in the 19th century and nowhere earlier! Turns out that the author Krishnananda Vyas was a singer who toured most of north India to collect poems to compose this musical treatise. These were oral poems, as admitted by Manager Pandey himself , collected by Krishnananda Vyasa from various folk singers. These poems did not exist in any document before 1842 and were just oral folk poems collected by a singer, and attributed to Aurangzeb, almost 200 years later. This leaves a gap of almost two centuries between Aurangzeb and the poems allegedly written by him. This makes us question the scholarly integrity of someone who always harps on contemporary sources but ignores such a huge gap only as it seems to suit a specific theory.

This is not all! In 1889, the renowned British linguist George Grierson while writing his book on Hindi literature, looked for the book published by Krishnananda Vyas , he found that there was not a single copy available. The book available to us is the one republished by Nagendranath Basu, a Bengali author, in three editions from 1914 to 1916. Thus, we cannot be certain about how much is Nagendranath Basu’s republication true to Krishnanand Vyasa’s original book. A serious doubt is cast by the fact that the third volume is in Bangla and not Hindi. It is likely that the copy or source available to Nagendranath Basu was interpolated or corrupted with regional poems. Therefore, going by the scholarship displayed by Manager Pandey’s and subsequently the author, the Mughal kings also wrote in Bengali!

But the story doesn’t end here! We found that Manager Pandey committed a huge blunder by attributing poems written by court poets to Mughal emperor.

He attributes the poems of Muhammad Shah Rangile to Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah when Muhammad Shah Rangile was the Mudra of his court poet Nemat Khan.

Similarly, the eleven Hindi poems attributed to Aurangzeb have actually been written by a person who seems to be a court poet . This is clear from the poems.

In the first poem, he praises the Mughal dynasty and says, “Oh master, I shall describe your glories O progeny of Babur” (54.1). It is extremely difficult to accept that these were Aurangzeb’s poems as they are addressed to Aurangzeb himself in vocative case.

In the second poem (55.2), he says, “Now my misery has gone, happiness has come, I have become a favourite of Aurangzeb, I have become rich”.

Aurangzeb was not a court poet to express happiness on alleviation of poverty by a patron.

In the third poem (55.3), he says, “May emperor Aurangzeb live a crore years”.

In the fourth poem,” Emperor Aurangzeb is the remover of all pains, he takes you across (the world ocean), he is the destroyer of misery and poverty” (55.4).

In the fifth, “Emperor Aurangzeb is master of my masters”, he is the most powerful and most intelligent”. This actually gives us the evidence that the poet belonged not to the court of Aurangzeb but to one of his Mansabdars.

Finally, (56.9) ” each particle of my body is delighted by the blessed vision of Aurangzeb”.

And as regards Brahma, Vishnu, Mahesh, this is the poem

Uttam Lagan Shoba Sagun

Gin Gin Brahma Vishnu Mahesh

Vyas Keeno Shah Aurangzeb Jasan

Takhat Baitho Aannandan

Shah Aurangzeb Jagat Peer Haran

Lok Taare Nistare Fandehi

Rehat Dukh Daaridr Ke Ganjan

We have tried to roughly translate it

At the auspicious time and virtuous grace recounting Brahman, Vishnu, Mahesh, Aurangzeb happily sat on his glorious throne.

Shah Aurangzeb is the peer of the world. He is the one who carries the world across. He is the one who annihilates poverty and misery

It is, therefore, a travesty to ascribe the poems in Manager Pandey’s book to Aurangzeb!

At 88, as he lay dying, he was consumed by a longing for mangoes, she writes — a detail that stands out with an overwhelming sense of pathos and makes this re-telling of the emperor’s life richly rewarding.

Aurangzeb had one Qumir beheaded he wrote a book with Christian tendencies which could not be refuted by hMuslim divines. He has a Portuguese convert beheaded when he reverted to his original faith! These are also his accomplishments which don’t seem to find mention. In no way does the narrative, being created through the book, seem to be grounded in historical facts! The book is devoid of complete historical evidence and tries to obfuscate facts. No honest scholar would falsify facts to paint outright religious bigotry as a political compulsion. All the articles and posts being churned to market this book seem to be targeted at putting out an incorrect narrative through which revulsion for Aurangzeb’s conduct in the past is wrongly meant to be interpreted as revulsion for people of his own faith in the present. This makes us wonder if those who have written posts on the book have read the book to find out if this mythification of Aurangzeb, under the ironical guise of debunking the myths related to the man, is fact or fiction. Reason enough for us to pen Aurangzeb – The Man And Her Myth?

-@TrueIndology @dimple_kaul

References

1. Truschke, Audrey. Aurangzeb, The man and his myth(2016)

2. Hijri, Zulfikar. Diversity and pluralism in Islam(2010)

3. Dasam Granth , Bachitar Natak PP.169

4. Pinault, D Horse of Karbala: Muslim Devotional Life in India(2016) PP.16

5. Toby Howarth , The Twelver Shi’a as a Muslim Minority in India: Pulpit of Tears(2005) PP.158

6. Bahadur Singh, Yadgar-I-Bahaduri Mss. 30,786

7. Sahifat, Persian MS copy, P.252

8. Waqiat I Mamlaqat I Bijapur Volume 3

9. R Nath, Annals of The Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute, Vol. 83 (2002), PP. 211-214

10.Muslim Zion: Pakistan as a Political Idea By Faisal Devji PP.96

![Image result for ram mandir ayodhya]()

Gyanvapi Mosque built in 1669 CE by Aurangzeb on top of the great Vishveshwar temple

Gyanvapi Mosque built in 1669 CE by Aurangzeb on top of the great Vishveshwar temple

Sitaramji temple Soron;Destroyed by Aurangzeb

Sitaramji temple Soron;Destroyed by Aurangzeb Ruins of Harshnath temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1679

Ruins of Harshnath temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1679 Ruins of Harshnath temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1679

Ruins of Harshnath temple destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1679 Someshwar Temple(Rajasthan). Destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1680

Someshwar Temple(Rajasthan). Destroyed by Aurangzeb in 1680 Bhuleshwara temple ruined by Aurangzeb

Bhuleshwara temple ruined by Aurangzeb Idgah mosque built by Aurangzeb over Keshav Rai temple in Krishnajanmabhoomi complex. Mathura, 1670

Idgah mosque built by Aurangzeb over Keshav Rai temple in Krishnajanmabhoomi complex. Mathura, 1670

Aurangzeb destroyed Charchika temple and converted it into Bijamandal mosque. C.1682 CE

Aurangzeb destroyed Charchika temple and converted it into Bijamandal mosque. C.1682 CE

Jiroft artifact. Two zebu PLUS twisted cord

Jiroft artifact. Two zebu PLUS twisted cord

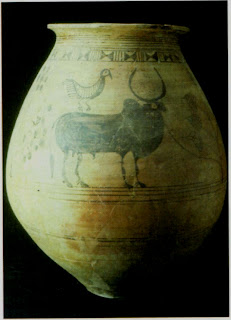

Nausharo. Pot.

Nausharo. Pot. A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE.

A zebu bull tied to a post; a bird above. Large painted storage jar discovered in burned rooms at Nausharo, ca. 2600 to 2500 BCE.  m1118

m1118

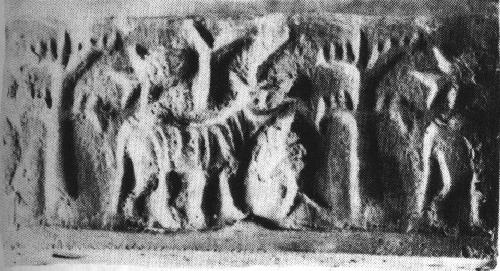

Cylinder (white shell) seal impression; Ur, Mesopotamia (IM 8028); white shell. height 1.7 cm., dia. 0.9 cm.; cf. Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 7-8

Cylinder (white shell) seal impression; Ur, Mesopotamia (IM 8028); white shell. height 1.7 cm., dia. 0.9 cm.; cf. Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 7-8

An additional six copies of these tablets, again all with the same inscriptions, were found elsewhere in the debris outside of perimeter wall [250] including two near the group of 16 and two in debris between the perimeter and curtain walls. Here all 22 tablets are displayed together with a unicorn intaglio seal from the Period 3B street inside the perimeter wall, which has two of the same signs as those found on the tablets.

An additional six copies of these tablets, again all with the same inscriptions, were found elsewhere in the debris outside of perimeter wall [250] including two near the group of 16 and two in debris between the perimeter and curtain walls. Here all 22 tablets are displayed together with a unicorn intaglio seal from the Period 3B street inside the perimeter wall, which has two of the same signs as those found on the tablets.  After Fig. 4. Harappa 1995-1997: Mounds E and ET; Trench 11: steatite seal H96-2796/6874-01 and incised steatite tablets (22) with the same inscriptions. "The last 2 signs of this seal are the same as those on one side of the 22 tablets (taking three strokes as a single sign)...Each tablet is three-sided with the inscription on each side comprising a single more complex sign accompanied by three or four simple strokes." The tablets are "incised with script that was to be read directly from the tablet." (Note by J. Mark Kenoyer & Richard H. meadow on Inscribed objects from Harappa excavations: 1986-2007 in: Asko Parpola, BM ande and Petteri Koskikallio eds., 2010, CISI, Vol.3: New material, untraced objects, and collections outside India and Pakistan, Part 1: Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, Helsinki, Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, (pp.xliv to lviii), p. xliv

After Fig. 4. Harappa 1995-1997: Mounds E and ET; Trench 11: steatite seal H96-2796/6874-01 and incised steatite tablets (22) with the same inscriptions. "The last 2 signs of this seal are the same as those on one side of the 22 tablets (taking three strokes as a single sign)...Each tablet is three-sided with the inscription on each side comprising a single more complex sign accompanied by three or four simple strokes." The tablets are "incised with script that was to be read directly from the tablet." (Note by J. Mark Kenoyer & Richard H. meadow on Inscribed objects from Harappa excavations: 1986-2007 in: Asko Parpola, BM ande and Petteri Koskikallio eds., 2010, CISI, Vol.3: New material, untraced objects, and collections outside India and Pakistan, Part 1: Mohenjo-daro and Harappa, Helsinki, Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, (pp.xliv to lviii), p. xliv

h252A

h252A h254B

h254B

Background of Shek Husen -TN Farmer protests

Background of Shek Husen -TN Farmer protests Shek Husen updates his profile picture against an Indian Kashmir

Shek Husen updates his profile picture against an Indian Kashmir Shek Husen accuses the Indian Army of being rapists

Shek Husen accuses the Indian Army of being rapists Shek Husen posts in favor of terrorist Afzal Guru

Shek Husen posts in favor of terrorist Afzal Guru