Sri Rāma and Sri Krishna are the ātmā of Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam.

There can be no Itihāsa of Bhāratam Janam without the narratives of Sri Rama and Sri Krishna which are "still living and throbbing in the lives of the Indian people," to cite Sukthankar.

Together with the book review of Meenakshi Jain's work on 'The Battle for Rama', I publish excerpts from Sukthankar's lectures posthumously published with the title: On the meaning of the Mahābhārata

The meaning of the Ramayana and the Mahabharata is the quintessemtial essemce of Itihāsa of Bhāratiya identity. A remarkable divinity links the two epics: Ānjaneya also called Hanumān.

Hanumān is an ardent devotee of Rama. Arjuna displays

The Battle for Rama reviewed in this note is thus the battle for a statement of hāratiya identity.

Sukthankar states about the two Epics, Mahābhārata and Rāmāyaṇa: what is more remarkable still is that this epic - along with the ramAyaNa -- is still living and throbbing in the lives of the indian people -- not merely of the intelligentsia, but also of the illiterate and inarticulate masses, the "hewers of wood and the carriers of water."

No power on earth can take Sri Rama and Sri Krishna from the collective memories of over 2 billion people of the Indian Ocean Community since their itihāsa defines dharma-dhamma which is the weltanschauung of these people.. Visvāmitra refers to Rāma as vigrahavān dharmah.'enbodiment of dharma'. Sri Krishna is revered as Gitāchārya of Bhagavadgīta which is the quintessential statement of dharma.

Bhāratiya Itihāsa has to be narrated with the narratives of Sri Rāma and Sri Krishna.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center February 28, 2017

Professor Meenakshi Jain's new book, 'The Battle for Rama: Case of the Temple at Ayodhya', is a definitive and scholarly guide to the biggest controversy of the early nineties, which totally changed the dynamics of Indian politics. Review by Koenraad Elst Posted On: 28 Feb 2017 Ayodhya, the city supposedly founded by the patriarch Manu, and at one time the seat of the kings belonging to the Solar Dynasty, including Rama, still decides who can rule India. It no longer arouses the passions it did ca. 1990, but we all have to live with the political consequences of the controversies of those days.

Political fall-out

In the 1980s the Congress Party aimed for a non-conflictual way to leave the contested site of Rama’s birth to Hindu society, where it belongs, all while compensating the Muslim leadership with some concessions. This would have been typical Congress culture: horse-trading may not be noble, but it has the merit of not needlessly exacerbating tensions, it is bloodless and keeps all parties satisfied. By 1990, the temple could have been built, just one more of the thousands that adorn India, and the whole matter would have been forgotten by now.

But the secularist historians publicly intervened and put everyone on notice that the misplaced Babri Masjid which Muslims had imposed on the site centuries ago was the last bulwark of secularism. Just like Jawaharlal Nehru said about democracy in peril: “Defend it with all your might!” Though it was a Congress PM, PV Narasimha Rao, who presided over its demolition by Hindu militants on 6 December 1992 and refused to save the Masjid, the party did not stay the course. It had been intimidated into conformity with the secularist line and also underwent the natural effect of polarization: it adopted the line opposite to the one that had by then been chosen by its adversary, the BJP.

Under the fateful leadership of Atal Behari Vajpayee, the BJP had been reduced to total marginality in the 1980s. After it committed itself to the Ayodhya cause championed by the Vishva Hindu Parishad, however, it made a spectacular leap in the 1989 elections and became the largest opposition party in the snap elections of 1991. After those profits had been politically encashed, it effectively abandoned the cause. This betrayal (together with the Supreme Court’s dithering in speaking out on the controversy) provoked the activists into wresting the initiative from BJP leader Lal Krishan Advani and physically removing the mosque. This only encouraged the BJP to disown the movement entirely.

No matter, for by then, a decisive turn had been taken. For Rama and his devotees, the main hurdle in the way of building a proper temple at his birth site was now out of the way. Hindus could look forward to Ayodhya becoming an unfettered pilgrimage site. Most Muslims now gave up all hopes of having the site as their own. However, the Muslim hardliners could console themselves that, on present demographic trends, India will turn Islamic-majority anyway, at which time all open accounts can still be settled. The case which the secularist historians had tried to build, deploying rhetoric with which they managed to over-awe the politicians, still had to judicially confront the case built in favour of the temple by other scholars. Those in the know expected that the secularists would not be able to convince the judges.

For the BJP, what counted was that it had by now become a non-ignorable political player. It was on the way to accession to the government. As Prime Ministers, both Vajpayee and Narendra Modi owe a debt to Rama and his dynamic devotees. Conversely, by leaving the issue to the BJP, Congress no longer had a monopoly on being the natural party of government.

Battle

To sum up: the Ayodhya controversy was one of the main events in post-Independence India. It is inappropriate, though significant, that all the vocal Ayodhya-meddlers of yore have fallen silent. Conversely, it is everyone’s good fortune that a comprehensive account of the decisive factors in at least the scholarly debate has been presented, and further researched for angles hitherto unknown, by as competent a historian and as serene a writer as Meenakshi Jain.

In her new book, 'The Battle for Rama: Case of the Temple at Ayodhya' (Aryan Books International, Delhi 2017), Prof. Jain gives a contents-wise overview of the controversy. It hardly touches upon the street riots and political campaigns but focuses on the documentary and archaeological evidence and the scholarly debate about these. The book carries plenty of photographs of the artefacts found at the site. With only 160 pages and a pleasant layout, it ought to reach the larger public and henceforth serve as the definitive guide to what the stake of the whole affair was.

She, first of all, lays bare what the controversy was about. First of all, not about Rama’s existence or the exact place where he was born. Religions never submit their basic convictions to a secular court (though these convictions are a fair object of free intellectual debate). Hindus need not lower themselves to that level, though some leaders actually felt pressured into the silly exercise of “proving” Rama’s existence. Conversely, nor should the secularists have demanded this of them: they already showed their malicious intent by even raising the question. And, of course, they never asked of the Muslim party by what right a mosque had been imposed on the temple site, even though it directly implicates their scriptures and the example set by their Prophet, who had personally destroyed the murtis in the main pilgrimage site of the Pagan Arabs, the Kaaba in Mecca.

Rather, the focus rightfully was, and has effectively been, on the medieval history of the site, when a replay of the usual scenario of iconoclasm already enacted in numerous places to India’s west had been inflicted on the Rama Janmabhumi site. Until the early 1980s, no interested party had denied that a Rama birthplace temple had been demolished to make way for a mosque. In the atmosphere of ca. 1990, whipped up by the secularists, arguing for this scenario had seemed an uphill task, and the scholars who did the job were widely acclaimed in Hindu circles. Not just the medieval battles resulting in iconoclasm and the street riots then taking place, but even the historians’ debate turned out to be a battle requiring some courage.

Brazen-faced deceit

But in fact, they could capitalize on a number of documents written in tempore non suspecto, mostly by Muslims, that attested it. Their argument claimed nothing out of the ordinary, it was the secularist case that, with hindsight, stood out as far-fetched. The closer verification of the evidence undertaken by Prof. Jain shows that the secularist case proves to have been even poorer than we thought at the time.

In her book 'Rama and Ayodhya' (2013), she had already shown that the Leftist academics who had fought for the Babri Masjid, had crumbled under judicial court-examination. This time, we are given to deal not just with their lack of genuine expertise, but with actual deceit and deliberate lies by some of them. Back in 1990, in his article “Hideaway communalism”, Arun Shourie had already brought to light four cases where Muslim authorities had tampered with old documents that showed how the Muslim community itself had always taken for granted the mosque’s location on land venerated as Rama’s birthplace. Now, Irfan Habib’s seemingly strongest piece of evidence (not for the temple’s non-existence, of course, but at least for the untrustworthiness of some pro-temple spokesmen) turned out to be false. During the demolition on 6 December 1992, many Hindu artefacts had turned up, albeit in less than desirable circumstances from an archaeological viewpoint. Proper excavations at the site in mid-1993 found some more, before the thorough Court-ordered excavations by the Archaeological Survey of India in 2003 uncovered the famous pillar-bases, long ridiculed as a “Hindutva concoction” by the secularists but henceforth undeniable. Among the first findings during the demolition was the Vishnu Hari inscription, dating from the mid-11th century Rajput temple, which the Babri Masjid masons had placed between the outer and inner wall. Several Babri historians dismissed the inscription as fake, as of much later date, or as actually brought by the Kar Sevaks during the demolition itself.

Prof. Irfan Habib, in a combine with Dr. Jahnawi Roy and Dr. Pushpa Prasad, dismissed this inscription as stolen from the Lucknow Museum and to be nothing other than the Treta ka Thakur inscription. The curator kept this inscription under lock, but after some trying, Kishore Kunal, author of another Ayodhya book (Ayodhya Revisited, 2016), could finally gain access to it and publish a photograph. What had been suspected all along, turns out to be true: Prof. Habib, who must have known both inscriptions, has told a blatant lie. Both inscriptions exist and are different. Here they have been neatly juxtaposed on p.104-5. Yet, none of the three scholars has “responded to the publication of the photograph of the Treta ka Thakur inscription, which falsifies the arguments they have been persistently advocating for over two decades.” (p.112)

It is no news if a secularist tells a lie: they have been doing it all along. Only, in the past they could get away with it, as the media and the publishers toed their line and withheld the publication of facts that pin-pricked their authority. Today, internet media have broken open the public sphere and some publishers have been emboldened to defy the secularists by exposing their misdeeds and defeats. The establishment media will not give any publicity to this book but defend the status-quo instead, yet the truth is irrevocably out. Since the suppression of the truth concerning Ayodhya was part of a power equation to the secularists’ advantage, the waning of that power equation means that future scholars will now become free to take the mendaciousness of the then secularists into account.

Pro-temple case

On the other hand, the pro-temple case turns out to have been even stronger than Hindus at the time realized. Thus, in much of the Moghul period, Muslims continuously acknowledged the site’s association with Rama. In the circumstances, Hindus could not replace mosque architecture with temple architecture, but they continued to assert their presence around the site and celebrate Rama’s birthday (Rama Navami). Since the crumbling of Moghul power, they even seem to have had access to the disputed building itself:

“No evidence whatsoever has been proffered of continued Muslim occupation Babri Masjid, while the uninterrupted presence of Hindu devotees has been attested by several sources. Babri Masjid finds no mention in the revenue records of the Nawabi and British periods, nor was any Waqf ever created for its upkeep. No Muslim filed an FIR when the image of Sri Rama was placed under the central dome on 23rd December 1949.” (p.144)

It is only in the nick of time that the Sunni Central Waqf Board entered litigation, on 18 December 1961 (five days later, it would have become time-barred), thus juridically causing the controversy. From then on, it was up to the politicians to ensure a peaceful settlement to prevent the Court proceedings from provoking street riots. After the Court gave Hindu worshippers unlimited access in 1986, a definitive formal settlement became urgent. Congress PM Rajiv Gandhi thought he could handle this challenge, but the initiative was wrested from his hands by the secularist historians. With their shrill statements about “secularism in danger”, they raised the stakes enormously. The rest is history.

Discrimination

Even after the Allahabad High Court ruled in favour of the Hindu claim on 30 September 2010, a statement signed by a handful of secularist veterans of the anti-temple campaign considered it a scandal that the verdict had acknowledged the “faith and belief of the Hindus” (quoted p.140). Mind you, the judges had not interiorized that claim, they had kept a clear distance, but assumed that “secularism” presupposes a recognition of this fact. This is the attitude that any Indian law or verdict adopts concerning Islam as well. The very existence of a category “Muslim community” (entitled e.g. to the Hajj pilgrimage and even to taxpayer-funded subsidies for this Hajj) implies the acknowledgment of a specific set of beliefs that make up Islam, and nobody finds this a scandal.

So, this statement bespeaks a discrimination between Hindus, who are first expected to give scientific proofs of their beliefs, and the minorities, whose irrational and unprovable beliefs should be accepted without any ado. It is but one of the many illustrations of how in India, “secularist” unambiguously means “anti-Hindu”. That is not paranoia but a hard fact, frequently illustrated by real-life events including unasked-for statements by the secularists themselves. India-watchers who assure their audiences that the Indian state is “religiously neutral”, or indeed “secular”, only prove their own incompetence.

As Prof. Jain concludes:

“So why has the matter dragged on for so long? Can a handful of historians be held accountable for stalling resolution of what is essentially a settled matter? Their voluble assertions on Babri Masjid have all been found to be erroneous, yet there has been no public retraction. Are they liable for vitiating social harmony over the issue? If the nation has to move on, honest answers must be found to these questions.” (p.145)

Epilogue

This book documents one rare Hindu victory. Having personally lived through some scenes of this long drama, and having seen many of the concerned actors evolve over the years, and seen one generation succeeded by another, I wonder if this victory doesn’t highlight a deeper evolution that can only be characterized as a defeat.

Around 1990, enormous passions were unleashed by the masses’ attachment to the Rama Janmabhumi or the Babri Masjid. It led some activists to acts of resourcefulness and of heroism including giving their lives. It led some scholars to the abandonment of their professional objectivity, to acts of deceit and plain mendaciousness. But at any rate, it proved numerous people’s deep convictions. One can hardly imagine such passions today, and perhaps it is for the better, with cooler heads and calmer minds. Unfortunately, the real reason seems to lie elsewhere.

In comparison, today’s Hindus, and especially the young generation, are more lukewarm about issues of Hindu history. Indeed, they are far more ignorant about them, and “unknown makes unloved”. Today they know all about computer games and silly American-inspired TV shows, but little about Hanuman. When I enquired about this among youngsters looking up from their smartphones, they claimed that they actually knew more about Hinduism than their parents’ generation. That might be true to an extent for the inquisitive ones who look things up on Google (not always a reliable source, moreover), but the vast majority does not compensate for its increasing ignorance this way. On the contrary, the illiterate and semi-literate ones are the demographic where this decline of Hinduism is most palpable (to the extent that an outsider can tell; but then, many insiders confirm this impression). They used to interiorize Hinduism not by reading or scanning, but by breathing in the culture that existed all around them. It is this that now disappears, making way for the hollowest contents of the modern media.

In this respect, the secularists have won. It is their version of history that is percolating to the masses. Many of them know nothing about history except what they have learned at school in their history textbooks. And these are under secularist control. A BJP attempt to correct these ca. 2002 failed. The only new schoolbook that was fully up to standard, was precisely the contribution by Meenakshi Jain. In any case, all BJP textbooks were at once discarded as soon as the Congress-Communist alliance came to power in 2004. The present BJP government is hardly equipped to do a new overhaul, and even shows no interest in doing so.

So, either Hindu society is continuing on the present path, and then Prof. Jain’s beautiful book will merely gather dust as a memory from a bygone age when Hindus had not given up yet. A museum piece. Only if it inspires more such thorough history, and only if the latter gets promoted by a powerful establishment among the masses, will it prove to be the light-bringer of a new dawn.

------------------------------------------------------------

![Koenraad]() Koenraad Elst (°Leuven 1959) distinguished himself early on as eager to learn and to dissent. After a few hippie years, he studied at the KU Leuven, obtaining MA degrees in Sinology, Indology and Philosophy. After a research stay at Benares Hindu University, he did original fieldwork for a doctorate on Hindu nationalism, which he obtained magna cum laude in 1998. As an independent researcher, he earned laurels and ostracism with his findings on hot items like Islam, multiculturalism and the secular state, the roots of Indo-European, the Ayodhya temple/mosque dispute and Mahatma Gandhi's legacy. He also published on the interface of religion and politics, correlative cosmologies, the dark side of Buddhism, the reinvention of Hinduism, technical points of Indian and Chinese philosophies, various language policy issues, Maoism, the renewed relevance of Confucius in conservatism, the increasing Asian stamp on integrating world civilization, direct democracy, the defence of threatened freedoms, and the Belgian question. Regarding religion, he combines human sympathy with substantive skepticism.

Koenraad Elst (°Leuven 1959) distinguished himself early on as eager to learn and to dissent. After a few hippie years, he studied at the KU Leuven, obtaining MA degrees in Sinology, Indology and Philosophy. After a research stay at Benares Hindu University, he did original fieldwork for a doctorate on Hindu nationalism, which he obtained magna cum laude in 1998. As an independent researcher, he earned laurels and ostracism with his findings on hot items like Islam, multiculturalism and the secular state, the roots of Indo-European, the Ayodhya temple/mosque dispute and Mahatma Gandhi's legacy. He also published on the interface of religion and politics, correlative cosmologies, the dark side of Buddhism, the reinvention of Hinduism, technical points of Indian and Chinese philosophies, various language policy issues, Maoism, the renewed relevance of Confucius in conservatism, the increasing Asian stamp on integrating world civilization, direct democracy, the defence of threatened freedoms, and the Belgian question. Regarding religion, he combines human sympathy with substantive skepticism.On the meaning of the Mahabharata

Vishnu Sitaram Sukthankar

Sukthankar, Vishnu Sitaram;

On the meaning of the Mahabharata

Asiatic society of bombay, 1957, 146 pages

ISBN 8120815033, 9788120815032

topics: | india | myth | religion |

v.s. sukthankar was a noted expert on sanskrit epics, the editor of the well-known bhandarkar "critical edition" of the mahAbhArata.

in 1942 sukthankar was invited by the university of bombay to deliver four lectures on the "meaning of the mahabharata". however, in january 1943, on the day of the fourth and last lecture, well after a large number of people had reached the lecture-hall, they received the shocking news that prof. sukthanar had passed away that very morning. the audience then converted the meeting "into a condolence meeting and paid their respects to the memory of this distinguished devotee of the great epic."

a dozen years later, the manuscript of these lectures were obtained from his son and they were published as this book.

the first lecture traces the history of mahAbhArata scholarship in the west, and is quietly critical of many of western scholars. it would take several more decades before edward said opened our eyes to to some of these moves which are now well-understood as part of the orientalist stance.

the essay is hardly known, and i am excerpting large chunks from it, since it makes for great history, and you get a glimpse into the mind of a very superb, contrarian scholar.

lecture I: the mahAbhArata and its critics

"the mahAbhArata," wrote hermann OLDENBERG [1854-1920], " began its existence as a simple epic narrative. it became, in course of centuries, the most monstrous chaos."

a forceful and imaginative writer, oldenberg has drawn for us a vivid pen-picture of this chaotic epic or epic chaos, as it appeared to him, which is worth quoting in extenso as a piece of fine rhetoric :

Neben der Haupterzahlung gab es dort wahre Urwälder kleinerer Erzählungen, dazu zahllose und endlose Belehrungen über Theologisches, Philosophisches, Naturwissenschaftliches, Recht, Politik, Lebensweisheit und Lebensklugheit. Ein Gedicht voll tiefsinnigen Träumens und Ahnens, zarter Poesie, schulmeisterlicher Plattheit - voll von funkeln-dem Farbenspiel, erdrückenden, sich zerdrückenden Massen von Bildern, vom Pfeilregen endloser Kampfe, Gewimmel über Gewimmel todesverachtender Heiden, übertugendlicher Mustermenschen, berückend schoner Frauen, Jähzorniger Asketen, abenteuerlicher Fabelwesen, toller Mirakel -- von leerem Wortschwall und von weiten, freien Blicken in die Ordnungen des Weltlaufes.

[a forest of smaller narratives were mixed into the main tale, along with ruminations on theology, philosophy, science, law, politics, life wisdom.profound poetry mixed with the tender, the pedantic and the platudinous.one is overwhelmed by the sparkle of colours - one picture after another like an endless stream of arrows. swarms of death-defying tribes runthrough its pages, along with enchanting women, irascible ascetics, adventurous imaginary creatures, and great miracles. empty verbiage runsside by side with perceptive passages on how the world works.]

this quizzical verdict of the great german indologist - a veritable prodigy of industry and erudition - appears indeed to be justified.there are indeed noticeable, winding in and out of the capacious and

multitudinous folds of this prodigious and remarkable tapestry, unmistakable traces of some great and complex action. but on account of the mass of legends and disquisitions in which the main theme lies embedded, it isdifficult to make out even the main outlines of the story underlying the

action.

"swollen by these inventions," as one sympathetic critic of the mahAbhArata touchingly protests, "the portentous volumes are enough to damp the spirit of the most ardent who, starting off gaily upon their journey, are soon faced by the deserts of levitical doctrine and the morasses of primitive speculation, interesting only to the antiquarian." owing to these digressions, which seem to have grown like a malignant parasite on the original heroic story and which do in a sense hamper the free movement of

the great drama, the poem appears not only to lose in artistic value but to be even lacking in bare unity.

even such an ardent and passionate admirer of the mahAbhArata as romesh chunder DUTT felt constrained to admit this defect in the poem, and bemoan most eloquently the loss of the original primitive epic. he has told us how he pictured to himself the lamentable process of this progressive

deterioration. he wrote (1898):

the epic became so popular that it went on growing with the growth of centuries. every generation of poets had something to add; every distant nation in northern india was anxious to interpolate some account of its deeds in the old record of the international war; every preacher of a new creed desired to have in the old epic some sanction for the new truths he inculcated. passages from legal and moral codes were incorporated in the work which appealed to the nation much more effectively than dry codes; and rules about the different castes and about the different stages of human life were included for the same purpose. all the floating mass of tales,traditions, legends, and myths .... found a shelter under the expanding wings of this wonderful epic; and as krishna worship became the prevailing religion of india after the decay of buddhism,the old epic caught the complexion of the times, and krishna-cult is its dominating religious idea in its present shape. it is thus that the work went on growing for a thousand years after it was first compiled and put together in the form of an epic; until the crystal rill of the epic itself was all but lost in an unending morass of religious and didactic episodes, legends, tales and traditions." p.2-3

if romesh DUTT, a thoroughbred "native" of india with just a thin veneer of western culture, had after a life-long study of the epic failed to grasp the real significance of what he elsewhere describes as "the greatest work of imagination that asia has produced" [suthankar suggests that one may just as

well say "that the world has produced"] -- there is nothing strange in the circumstance that most of the Western critics have like~ wise failed to do so. They have uniformly felt and exhibited a characteristic uneasiness -- I may even say helplessness -- when faced with the -- to them, unnatural -- phenomenon of an avowedly narrative poem in which the "moral", so to say, is nearly four times as long as the story itself. Their researches have, consequently, revolved almost invariably 'round the idea of finding criteria for distinguishing between the "early" and the "late" portions of the epic, between the original and the interpolation, criteria for cutting away what they naturally regard as the asphyxiating parasite and exposing the old, primitive saga in its pristine purity and glory.

this definitive direction seems to have been given to western studies in connection with the mahAbhArata almost from the beginning. franz BOPP [1791-1867], the father of indo-germanic philology, (who was also the first in modern times to edit from manuscripts selected episodes from the mahabharata and make them available in a printed form, had expressed this opinion as early as more than a century ago -- in 1829 -- that all parts of the epic were not of the same age, -- which is in a way no doubt quite true.

[BOPP was followed by LASSEN [1800–1876]- erudite analysis of

mahAbhArata... ]

in the MahAbhArata we have pieces belonging to very different periods and of very different colour and content. He tried therefore to separate the various strata and to date them -- a very hazardous venture at any time.

to us these stratificatory adventures and chronological speculations of LASSEN appear crude and puerile in the extreme; they were taken very seriously by his contemporaries, and regarded as a stupendous advance in their knowledge of the great epic of india.

owing to his very perfunctory study of this prodigious poem, the learned author of the indische alterthumskunde had failed to realize that eliminating the "krishnite " elements from our mahabharata was a not less serious operation than removing all the vital elements from the body of a living organism; and that consequently the residue would no more represent the "original" heroic poem than a mangled cadavre, lacking the vital elments, would represent the organim in its origin or infancy.

another notable attempt at reconstructing the original epic was made between 1883 and 1894 by the scandinavian scholar soren SORENSEN, to whom we also owe the excellent index to the names in the mahAbhArata (london 1904-1925), a solid contribution to mahAbhArata studies, indispensable to every serious student of the great epic. his attempts at reconstruction of the epic kernel have unfortunately not proved equally valuable. [...] [ss attempts to construct an ur-text] the number of stanzas in sorensen's "ur-text" is strangely close to the so-called "kUTashlokas" mentioned in an oft-cited stanza which is a patent interpolation found in some very late Devanagari manuscripts and which has consequently been rejected in the critical edition of the mahAbhArata.

Auguste BARTH [1834-1916], on Sorensen's ur-text: "le methode de I'auteur, malgre toutes le precautions possible, est arbitraire et ...... le probleme tel qu'il le pose, est en realite insoluble." [the methods of the author, despite all precautions, remain arbitrary... and the problem he poses is in

fact insoluble.]

later european scholars [did not pursue the idea of the ur-text, but] contented themselves with theorizing about the nature and the character of the "nucleus" and perfecting their criteria for distinguishing between the "old" and the "new," the original and the spurious in the epic text.

[LUDWIG ?[1904-1978]: focus on how the text was joined together - is it harmonious or

clumsy? [but clearly such a study cannot give dependable results, since it would be subjective.]

this atomistic method reaches its culmination in tbe researches of the great american indologist e. washburn HOPKINS [1857-1932], who had specialized in the mahAbhArata and who, as a result of an intensive study of the epic extending over many years, made the interesting discovery that there was no text there at all.

he could see only a nebulous mass of incongruities, absurdities, contradictions, anachronisms, accretions and interpolations ! " in what shape," asks hopkins, " has epic poetry (in india) come down to us?" and his own answer is: "a text that is no text, enlarged and altered in every recension, chapter after chapter recognized even by native commentaries as praksipta, in a land without historic sense or care for the preservation of popular monuments, where no check was put on any reciter or copyist who might add what beauties or polish what parts he would, where it was a merit to add a glory to the pet god, where every popular poem was handled freely and is so to this day."

the learned labours of hopkins ultimately crystallized in the preparation of a complicated table of

approximate dates of the work in its different stages, which he probably regarded as his greatest contribution to the study of the epic and the final solution of the mahAbhArata problem. here is the scheme of dates rigged up by hopkins:

400 b.c. : bhArata (kuru) lays, perhaps combined into one, but with no evidence of an epic.

400 to 200 b.c. : a mahAbhArata tale with pANDu heroes, lays and legends combined by the puranic diaskeuasts ; kr^SNa as a demigod ; no evidence of didactic form or of kr^SNas divine supremacy.

200 b.c. to 200 a.d. : remaking of the epic with kr^SNa as all-god, intrusion of masses of didactic matter, addition of Puranic material old and new ; multiplication of exploits.

200 to 400 a.d. : the last books added with the introduction to the first book, the swollen anushAsana separated from shAnti and recognized as a separate book ; and finally,

400 A.D. :+ : occasional amplifications.

without wishing to detract from the merits of the work done by hopkins in other fields, which may have its own value, i will say candidly that for all intents and purposes this pretentious table is as good as useless "all dates," says whitney, "given in indian literary history are pins set up to be bowled down again." this was never more true than in the case of the dates given by hopkins, which are in fact, one and all, quite hypothetical and perfectly arbitrary. indeed there is not one figure or one statement in the above table which can be verified or which can lay claims to objective validity.

let me state here more fully, for the sake of clarity, the view-point of the modern analytical criticism of the mahAbhArata. modern criticism begins with the assumption that the epic is definitely not the work of any one poet, like most works of antiquity. no one can write unaided a poem of 100,000 stanzas. we cannot possibly conceive any one man being equal to the task attributed to the kr^SNadvaipAyana vyAsa. the poem is therefore unquestionably a compilation, embodying the work of many writers of varying abilities -- some of them even real poets -- who have added to the original

corpus from time to time as it pleased them. The result is naturally a confused assemblage of heterogeneous matter originating from different hands and belonging to different strata.

a careful analysis of the poem from this view-point reveals the fact that in its present form at least, the work has a radical defect in so far as it consists fundamentally of two mutually incompatible elements, namely, a certain "epic nucleus" and an extensive and undigested mass of didactic-episodical matter, elements which are but loosely hinged together and which form moreover an unbalanced combination.

the first element, the epic nucleus, is naturally the older component and is presumably based on an historical reality, which is preserved in a highly distorted and tendentious form but which retains nevertheless certain genuine archaic features in fossilized condition such as polyandry and levirate [a form of marriage in which the brother of a deceased man is obliged to marry his brother's widow, and the widow is obliged to marry him.] -- these latter are of immense interest and importance for the study of indian ethnology and prehistoric antiquity.

the nucleus mentioned above was now unfortunately used - or rather misused-by wily priests, tedious moralists and dogmatizing lawyers as a convenient peg on which to hang their didactic discourses and sacerdotal legends, which have naturally no organic connection with the epic nucleus. this nucleus of the epic, a kSatriya tale of love and war, does possess a sort of unity, which is lacking entirely in the other element, the priestly episodes and the moralizing discourses, which latter by themselves, loosened from their moorings, would neatly and automatically fall apart. The epic story is in part at least a fairly well-constructed narrative, worthy of our attention, and produces the impression of having been yet more virile - a real "human document" - before it was distorted in the process of assimilation with the moralistic pabulum and legal claptrap of a grasping and degenerate

priesthood.

the mahAbhArata is in short a veritable chaos, containing some good and much useless matter. it is a great pity that a fine heroic poem, which may even be found to contain precious germs of ancient indian history, should have been thus ruined by its careless custodians.

but it is not quite beyond redemption. a skilful surgical operation - technically called "higher criticism" - could still disentangle the submerged "epic core" from the adventitious matter - known to textual critics as "interpolation" - in which it lies embedded. the mahAbhArata problem thus reduces itself to the discovery of criteria which will enable us to analyse the poem and to dissect out the "epic nucleus" from the spurious additions with which it is deeply incrusted. this is the "analytical theory" of the origin and the character of the mahAbhArata, which was espoused by the majority of the western critics of the great epic of india, chief among them being LASSER, WEBBER, LUDWIG, SORENSEN, HOPKINS and WINTERNITZ.

this theory is obviously the outcome of superficial study. the epic at first sight does produce upon a casual observer the impression of being a bizarre and meaningless accumulation of heterogeneous elements. this first impression, however -- as has been pointed out by HELD -- soon makes room for

a second, that of astonishment, as one realizes that this massive monument of indian antiquity may undoubtedly lay claim to being more or less flawless from the constructional view-point and withal perfectly balanced. this fact appears to have been clearly realized also by LUDWIG, himself an ardent advocate of the atomistic theory, who was honest enough to admit the organic unity of this stupendous poem. notwithstanding his preconceptions, which led him to support the analytic theory, he confessed openly his inability to explain how, in spite of the extreme complicacies' of mechanism, it operated in a manner so precise that no crass contradictions were discernible in this prodigious work, there being at most only vague traces here and there of what might be regarded as such.

kauravas more heroic than pANDavas? internal inconsistencies

but that is not the end of the story. there is another little odd twist in the poem, we are told: a subtle sort of topsy-turvydom underlying the story and vitiating it from beginning to end. the poem has obviously a didactic purpose. it sets out clearly to inculcate a moral. its method is to contrast the life and fate of the righteous pANDavas and the unrighteous kauravas, and to induce peqple to lead a good and virtuous life by demonstrating that, in spite of appearances to the contrary, truth and

virtue do triumph in the end (yato dharmas tato jayaH).

This is undoubtedly a very laudable objective. And yet even this simple and clear aim is scarcely achieved by the poem. The characters do not consistently act the parts which they are advertised to do. The "heroes" of the poem are indeed constantly talking about Dharma, but their actions belie

their hollow professions and do not conform even to the most elementary standards of common morality. They are not real heroes, with pure white shining souls. They give one the impression rather of being "villains," who have been liberally whitewashed by interested poets.

[e.g. yudhiSTira's lie to droNa about the death of ashvatthama, or bhIma's hitting duryodhana on his thighs. and even arjuna kills his grandfather bhISma while hiding behind an efffeminate warrior with whom the old knight would not fight, and he kills karNa while the latter is disadvantaged and pleading for time.]

can we regard these pANDava brothers as models of heroism, chivalry, nobility or righteousness ?

the kauravas on the other hand unquestionably behave more honourably and on the whole more magnanimously. they never stoop to employ such base and ignominious tricks on the battlefield against their enemies. they are manly, courageous, chivalrous and noble. these great scions of an old

aristocratic family could play more worthily the distinguished role of the heroes of the indian epopee than the treacherous and sanctimonious pANDavas, who show themselves to have been in reality ignoble parvenus and usurpers, glorified by a later generation. the poem itself naively records that at the moment of duryodhana's death, though the ungenerous and brutal bhIma was mean enough to kick and trample on the annointed head of the fallen monarch, the gods themselves showered flowers on the defeated hero. and this duryodhana is now the villain of the piece! it is unnecessary to multiply

examples.

here is a paradox. the book gives itself out as a dharmagrantha. with uplifted arms, we are told, vyAsa proclaims that dharma is supreme in this world. but that is a high ideal which even his characters -- his own creations -- do not fulfil!

the poem does contain explanations condoning the "sins" of the pANDavas. but

that is a special pleading, sheer casuistry, which fails to carry conviction

to any but the most simple-minded of the readers.

the talented discoverer of this set of facts was ADOLF HOLTZMANN. it was to

explain this element of contradiction in the story that he thought out his

ingenious theory, which HOPKINS later styled the " inversion theory " and

which found many adherents. this

inversion theory

this criticism, which bases itself on the supposed want of unity in the characters, is an effort to prove not merely a change but a complete inversion (in our present story) of the original theme, which explains its name "inversion theory." "starting with the two-fold nature of krishna-vishnu as man and god," as HOPKINS says in describing the theory, "and with the glossed-over sins of the pandus, the critic argues that the first poem was written for the glory of the kurus, and subsequenly tampered

with to magnify the pandus; and that in this latter form we have our present epic, dating from before the fourth century b.c." the first poem would thus be completely changed, or, as one writer has expressed it "set upon its head."

the indefatigable author of this theory, who had taken immense pains to study the epic from various angles in search of arguments to support and fortify his pet thesis, ultimately arrived at the following recondite reconstruction of the epic, as summarized by HELD :

right back in the most ancient times there was a guild of

court-singers who extolled in their professional poetry the mighty

deeds of their monarchs. then came a talented poet who made of the

original epic, composed in honour of the renowned race of the

kauravas, a poem in praise of a great buddhist ruler, perhaps

asoka. but now the new teaching, coming into conflict with the

growing pretensions of the brahmins, begins to decline, and the

priests convert the now popular poem to their own use, but reverse

the original purpose of the work as a whole. now it is no longer the

kauravas. who are lauded but their very adverseries, the pandavas,

to whom a decided predilection for the brahmanical doctrine is

ascribed. the epic is subjected to further revision. buddhism is

eliminated altogether, both vishnu and krishna are thrust into the

foreground, the epic is assimilated to the ancient and sacred

chronicles of the puratnas and portions of a didactic character are

interpolated. and in this revised and irrecognisably altered

recension the epic was non-existent until the twelfth century a.d."

these wild aberrations of HOLTZMANN... hardly deserve the name of a theory. 15

Buhler: epigraphic and other evidence for mahAbhArata dates

they are, as was pointed out by BARTH, not only at variance with the probable course of the religious and literary history of India, but they also stand in crass contradiction with positive and dated facts. The latter relation was brought out especially by the quite independent investigations of BUHLER regarding the mahAbhArata, which were more of a factitive character... as buhler showed, already in the eighth century the poem must have had a form not very different from the one in which we now possess it, namely, as a dharrnasastra or a smr^ti work, that is, a book of sacred lore. the epigraphic evidence, moreover, clearly proved that the epic was known as early as the fifth century a.d. as a work consisting of 100,000 stanzas and composed by the great r^si vyAsa. from this clear and unequivocal evidence, buhler drew the important conclusion that the work must unquestionably have been extant in practically the same shape as at present, several centuries prior to 400 a.d. this finding of BUHLER demolished completely the rickety chronological framework of HOLTZMANN'S fantastic reconstruction and made it clear that the historical background of the thesis was, fundamentally, as unsound as it was absurd.

HOLTZMANN's theory found, however, a doughty champion ih the Viennese Professor Leopold von SCHROEDER, who by pruning away the more patent absurdities set it once more on its legs, and even popularized it through the persuasive quality of his felicitous style and suave mannerism.

... the inversion theme was retained and strengthened.

remodelled by the genial SCHROEDER, the inversion theory took the following shape, as described by hopkins.

the original poet .... lived at a time when brahma was the highest god (700 to 500 or 400 b.c.) ; and this singer was a child of the kuru-land. he heard reports of the celebrated kuru race that once reigned in his land, but had been destroyed by the dishonourable fighting of a strange race of invaders. this tragical overthrow he depicted in such a way as to make his native heroes models of knightly virtue, while he painted the victors (pandus, panchalas,matsyas), with krishna, hero of the yAdavas, at their head, as ignoble and shamefully victorious. this is the old bharata song mentioned in AchvalAyana.

after a time krishna became a god, and his priests, supported by the pandus, sought to make krishna (vishnu) worthy to be set against buddha. their exertions were successful.

vishnu in the fourth century became the great god, and his grateful priests rewarded their helpers, the hindus, by taking the bhArata poem in hand and making a complete change in the story, so as to relieve them of the reproaches of the old poet. finally they worked it into such shape that it praised the pandus and blamed their opponents. about this time they inserted all the episodes that glorify vishnu as the highest god. the pandus then pretended that they had originally belonged to the kuru stock, and the cousinship portrayed in the poem was invented ; whereas they were really an alien, probably a southern race.".)

this ill-conceived theory, though advocated by LASSEN, WiNTERNITZ and J. J. MEYER, has been discountenanced for different reasons, by even BARTH, sylvain LEVI, PISCHEL, JACOBI, 0LDENBERG, and. HOPKINS.

dishonourable conduct by the pANDavas

bhiSma, droNa, karNa and duryodhana were all killed in the war by subterfuges or tricks which violate the strict axle of chivalrous and knightly combats. but the kauravas are just as unscrupulous, if not indeed more so ; only they are discreet and diplomatic in the extreme. their "sins," as HOPKINS has pointed out, smack of cultivated wickedness. they secretly try to burn their enemies alive. they seek to waylay and kill the ambassador of the pANDavas. they form a conspiracy and send out ten men under oath (saMshaptakas) to attack arjuna. they slay arjuna's son first in order to weaken arjuna's heart. are these dark deeds worthy . of models of royal and knightly honour? the truth is that the kauravas are crafty and designing; they are shrewd enough not to break the smaller laws of

propriety. they plot in secret, hiding their deceitfulness under an ostentatious cloak of justice and benevolence. they sin at heart, and present to the world a smiling and virtuous face.

the pANDavas are on the other hand represented throughout as being truly ngenuous and guileless they do "sin" they are human for that ~ but their "sins" are palpably overt and markedly evident. .the kauravas are sanctimonious hypocrites; the wrath and animosity of the grossly outraged

pANDavas stare us in the face.

HOPKINS: "society had advanced from a period when rude manners were justifiable and tricks were considered worthy of a warrior to time when a finer morality had begun to temper the crude royal and military spirit. this is sufficient explanation of that historical anomaly found in the great epic, the endeavour on the part of the priestly redactors to palliate and excuse the sins of their heroes."

HELD has rightly rejected this specious explanation of HOPKINS, pointing out that there is no reason to picture to ourselves those more primitive cultures as a barbarian state of society in which "brutal warrior kings" were rampant.

the atomistic methods of the advanced critics of the mahAbhArata having proved barren of any useful or intelligent result, some attempt was ·made to understand the poem as a whole. the most notable of these legitimate endeavours was that of joseph DAHLMANN; and as such it deserves special reoognition. a certain underlying unity of aim and plan in this gigantic work was postulated and dogmatically emphasized by this great jesuit scholar, who of all the foreign critcs of the mahAbhArata may be said to approach nearest to any real understanding of the great epic of india.

[this theory] categorically repudiates as utterly fantastic the notion that the great epic is but a haphazard compilation of disjointed and incoherent units. it insists on the other hand that the MahAbhArata is primarily a synthesis, a synthesis of all the various aspects of Law, in the widest sense of the term, covered by the Indian conception of dharma, cast by a master intellect into the alluring shape of a story, of an epic. in other words, the mahAbhArata is an epic and a law-book (rechtsbuch) in one. the poem is, as indian tradition has always implied, a conscious product of

literary art (kAvya) of the highest order, with a pronounced unity of conception, aim, and treatment.

Undismayed by the barrage of hostile and even mocking criticism which greeted his first work on the subject, "Das MahAbhArata als Epos una Rechtsbuch" (1895), he continued his labours, defending his favourite thesis again, with great eloquence and enthusiasm, in a second volume, "Geneszs des

MahAbhArata" (1899), which met with no better reception at the hands of his intolerant and opinionated colleagues...

in these earnest and thought-provoking bpoks, DAHLMANN has shown, on the basis of well selected and oonvincing examples, that the relation between the narrative and the didactic matter in our epic was definitely not of a casual character, but was intentional and purposive, concluding therefrom

that it was impossible to separate the two elements without destroy1ng or mutilating the poem...

the didactic matter of the epic, DAHLMANN insisted, was a necessary -- nay, an essential- element of the poem, of which the -- fable itself was in fact largely invented just for the purpose of illustrating certain well defined maxims of law, certain legal, moral and ethical principles underlying the fabric of indian society. thus, for example, there is, according to DAHLMANN, in the crucial instance no historical basis for the polyandric marriage of draupadi with the pANDava brothers, which is to be understood only symbolically. the pANDavs themselves symbolize the undivided or joint family; and draupadi, their common wife in the story, stands for the ideal embodiment and representation of the unconditional unity of the family. a tribal confederacy may perhaps have formed the historical basis of the unity of the pANDavas.

DAHLMANN's conclusions:

- the epic is a well defined unity

- each part has a specific purpose

- the unity of plan was conceived by a single person, who carried out the

work.

- date of the poem is NOT later than 5th c. BC

with DAHLMANN the pendulwn had clearly swung to theother extreme. We owe very impartial and searching criticisms of DAHLMANN'S views to JACOBI and BARTH, who have exposed certain weaknesses of the theory.

we must also admit now that DAHLMANN's views regarding the unity and homogeneity of the text of the epic were much exaggerated. It can now be demonstrated, with mathematical precision, that the text of the mahAbhArata used by DAHLMANN - the bombay or calcutta edition of the vulgate - is much inflated with late accretions and moot certainly does not, as a whole, go back to the fifth century b.c. it may even contain some furtive additions which had been made as late as . 1000 ad. or even later. the critical edition of the mahAbhArata, which is being published by the bhandarkar

oriental research institute, shows that large blocks of the text of the·vulgate must on incontrovertible evidence be excised as comparatively late interpolations.

the brahmA-gaNesha complex and the kaNika nIti in the Adi and the hymns to durgA in the virATa and the bhISma parvans occur to our mind readily as examples of such casual interpolations. but the southern recension offers us illustrations of regular long poems bejng bodily incorporated in the

epic, like the detailed description of the avataras of viSNu put in the mouth of bhISma in the sabhA, and the full enunciation of the vaiSNavadharma in the Ashvamedhikaparvan, two passages comprising together about 2500· stanzas. when we know that these additions have been made in comparatively recent times, even so late as the period to which our written tradition reaches back, can we legitimately assume that our text was free from such intrusions during that prolonged period in the history of our text which extends beyond the periphery of our manuscript tradition ?

the riddle of kr^SNa

it will be noticed that DAHLMANN had no explanation to offer of the paradox of kr^SNa, who looms so large in the world of the epio poets as to overshadow the entire poem, who is to be found in the beginning, in the middle, and in the end of the entire epopee. with his eyes fixed on the dichotomy of dharma and adharma, the most characteristic creation of indian genius, who was above dharma and adharma, beyond good and evil.

who is kr^SNa, indeed ? that paradox of paradoxes! a philosopher on the battlefield! an ally who gives away his powerful army to swell the ranks of his opponents; and himself, though the omnipotent lord of all weapons, takes a vow, before the commencement of the war, not to hold a weapon in his hands! a god who avows impartiality towards all living beings, and yet like a wily and unscrupulous politician secretly plots for the victory of the pANDavas and the annihilation of the kauravas! standing on the field of battle, this self-styled avaiara preaches the lower morality and the mere man (arjuna) the higher! a grotesque character who claims to be the highest god and behaves uncommonly like a "tricky mortal"!

this bizarre figure can certainly not belong to the original heroic poem, which must have been a straightforward work free from all contradictions of this kind. european savants are -agreed that he must needs be an innovation, introduced secondarily into the original " epic nucleus." how could european savants, lacking as they do in their intellectual make-up the milleniums old back-ground of indian culture, ever hope to penetrate this inscrutable mask of the unknowable pulling faces at them, befooling them and enjoying their antics? however we shall leave the matter there for the present.

The question of the historicity

Opinion is sharply divided on this point.

The work claims itself to be an Itihasa, a history; but criticism, both ancient and modern, has been loth to take this statement at its face value. Opinion has thus vacillated from the standpoint of categorical acceptance of perfect historicity to complete scepticism.

a very novel interpretation of the epic we owe to principal THADANI, professor of english in the hindu college of delhi, embodied in an ambitious work comprising five volumes entitled the mystery of the mahAbhArata : a difficult book which no layman can hope to understand. professor thadani is

a philosopher and a poet. accordingly his great work is both poetical and philosophical. it deepens and intensifies the "mystery" of the mahAbhArata rather than solves it.

the whole story of the mahAbhArata is, according to this learned scholar, "but an account of the connection and conflict between the different systems of hindu philosophy and religion." this is especially so in regard to the principal systems. thus there is a conflict between principal vedanta

(vaiSNavism) and principal yoga (saivism); principal yoga and principal sAMkhya (buddhism and jainism); and sAMkhya and vedanta.

professor THADANI is right in insisting that for debate or discussion there must be a common ground of agreement between opposing views, without which a discussion is impossible. i have none with the learned professor, nor have i had the good fortune of coming across anybody who had. professor thadani stands unchallenged.

let us now look at the matter from yet another angle. is it not passing strange that, notwithstanding the repeated and dogged attempts of western savants to demonstrate that our mahAbhArata is but an unintelligible conglomerate of disjointed pieces, without any meaning as a whole, the epic should always have occupied in indian antiquity an eminent position and uniformly enjoyed the highest reputation? it was used, we are told, as a book of education for the young bANa's time, like the iliad in hellenic greece. it has inspired the poets and dramatists of india as a quarry for their plots and ideas. it has attracted in the past celebrated indian philosophers like acarya saMkara and kumArila, famous indian saints like jnaneshwar and ramdas, and distinguished indian rulers like akbar and

shivaji. this epic of the· bhAratas had moreover penetrated to the farthest extremities of greater india. it had conquered not only burma and siam, but even the distant islands of java and bali. the immortal stories of this epic have been carved on the walls of the temples of these people by their sculptors, painted on their canvasses by their artists, acted in their wayongs by their showmen.

what is more remarkable still is that this epic - along with the ramAyaNa -- is still living and throbbing in the lives of the indian people -- not merely of the intelligentsia, but also of the illiterate and inarticulate masses, the "hewers of wood and the carriers of water."

instead of searching for an elusive original nucleus, i believe we shall find in the poem itself something far greater and nobler than the lost paradise of the primitive kSatriya tale of love and war, for which the western savants have been vainly searching, and which the indian people had long outgrown and discarded. 31

http://cse.iitk.ac.in/users/amit/books/sukthankar-1957-on-meaning-of.html

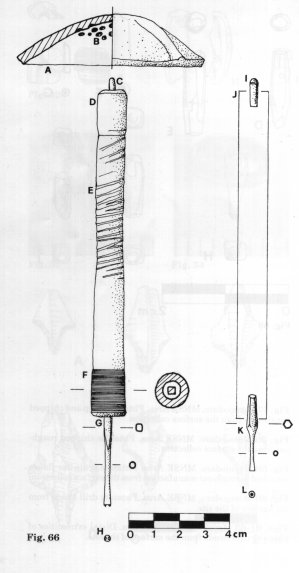

A cylinder seal with zebu and lion, Sibri {Jarrige) Hieroglyphs: aryeh 'lion' rebus: arā 'brass'; [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods. pōḷī, ‘dewlap, honeycomb’. Rebus: pola ‘magnetite ore’ (Munda. Asuri) [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon); Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, weapons, metalware'.

A cylinder seal with zebu and lion, Sibri {Jarrige) Hieroglyphs: aryeh 'lion' rebus: arā 'brass'; [ pōḷa ] m A bull dedicated to the gods. pōḷī, ‘dewlap, honeycomb’. Rebus: pola ‘magnetite ore’ (Munda. Asuri) [ khāṇḍā ] m A jag, notch, or indentation (as upon the edge of a tool or weapon); Rebus: khāṇḍā 'tools, weapons, metalware'.

_and_Porus_(oil_on_canvas).jpg)

Purushottama meets Alexander

Purushottama meets Alexander Alexander's retreat from Bharat campaign.

Alexander's retreat from Bharat campaign.

Subramanian Swamy

Subramanian Swamy