-The HAF Team

The Clandestine Curriculum: Temple of Doom in the Classroom

“Education About Asia”

2001 winter edition

(Published by: the Association of Asian Studies)

Yvette C. Rosser, PhD.

Social studies classrooms often have a back door through which a clandestine curriculum enters with images from popular myths, media, and movies. The scholarly discourse and the learning experience intertwine with this backdoor curriculum of folklore, stereotypes, and sensational misinformation. Often the fusion between Hollywood and the syllabus is so complete that fact and fiction become confused, and ultimately, like ‘Shakespeare or the Bible,’ we are unsure of the source of our knowledge.

Content on India is particularly susceptible to these covert pressures. At educational workshops about India and when making presentations to high school students, I am inevitably asked about the worship of rats in India. When I assert that it is absurd to teach this to students, teachers often argue that they “read it in an AP newswire.” I found it difficult to believe that in American classrooms rat worship is actually taught as a bona fide Hindu practice until my own son came home from high school and told me his World History teacher had made that very statement. The son of my friend who lives in another state also reported the same thing. Urban legends have metamorphosed into fact.

I have often explained to educators and students that the worship of rats among Hindus, at an obscure temple in Rajasthan mentioned in that now infamous AP wire report during the ‘epidemic’ in Surat in the early nineties, is comparable to the worship among Christians of David Koresh at the Davidian compound in Waco, Texas. This is an effective strategy since teachers and students respond passionately that though some Christians may have worshiped David Koresh, it is certainly not a defining characteristic of Christianity and is actually abhorrent to most Christians . . . as is rat worship among Hindus. This analogy helps to deconstruct and discard the flimsy tale of so-called rat worship in India.

When I make presentations about India at teachers’ conferences or in classrooms, the two most often asked questions are: “Why do women wear a ‘dot’ on their forehead?” and “Why, when there is so much poverty in India, don’t they eat all those cows?” These questions broach issues of relevance and correlating non-Western practices to similar experiences in the students’ lives, within a context they can comprehend.

When information about India is contextualized and made relevant rather than exotic and inexplicable, students will have a more realistic, and hopefully non-biased perspective of Indian culture. In answering the question about beef eating, I explain it in several ways. I mention the negative impact that raising beef for meat can have on the environment and, citing statistics, explain that it is ecologically highly inefficient to raise cattle for meat. It takes approximately sixteen pounds of edible vegetable protein and 44,000 gallons of water to make one pound of beef.[i] India cannot afford to waste that much protein and water in an inversely productive ratio. I explain that cows are used primarily for milk, which is a staple and one of the main caloric sources in India. In addition, oxen are essential for pulling plows and carts and for crop irrigation. Even more importantly, the cow is the national symbol, like the eagle is the symbol of the USA, where, in some states, even to be in possession an eagle feather, unless you are a member of a registered tribe, is a criminal offense punishable by a $5,000 fine. To many Hindus, their cow is a member of the family, like the family dog is loved in the USA. We would never eat Rover. Americans are repulsed by the thought of eating dog meat. Most Indians feel the same about the flesh of cows. Americans can easily understand this canine analogy: the thought of eating a cow is as repulsive to most Hindus as the thought of eating a dog or a horse is to most Americans. This does not preclude the eating of dogs or horses in other countries. Culinary habits are quite culturally specific.

A university student of Indian heritage suggested that teachers in World History classes should make associations

“with something Western that kids can understand–associate rebirth or moksha with a Christian principle like being born again or salvation. If [teachers discussed] the American flag and its [patriotic] symbolism, suddenly it would become clear what a symbol is. Instead of just saying that Hindus are idolaters, tell the students that the idols [revered by Hindus] are [religious] symbols to them. Unless the teacher explains it, in their own terms, the [students] think ‘these people are weird,’ but if you explain about the symbolism of the flag, it becomes rational.”

Relating perceived oddities about India to aspects of life in the West can shine a sympathetic light of commonality on practices and theories that might otherwise appear laughable and strange. Grounding the unfamiliar in a recognizable cultural context encourages transferability of respect for other traditions and an appreciation for the pluralistic nature of our world.

The “dot” on the forehead of Indian women is also easy to explain. Though historically originating from a mark with religious connotations still used by holy men and women and by priests, contemporary forms of the ‘dot’ are often made from velvet and glitter. They play the same glamorous role as lipstick or mascara. Some fashion statements are shared across cultures such as the painting of women’s nails and piercing of ear lobes, and others are particular to a certain people, such as the bindi, or dot. As can be seen by the growing popularity of nose rings among Western youths and blue jeans among Indian teens, fashions borrowed from other countries can easily become the norm.[ii] High school teachers often lament that India is more difficult to teach than other countries in Asia. They complain it’s too diverse, too ancient, too exotic, too many gods with too many arms. Unfortunately only a small fraction of aspiring teachers are able to take courses about India during their college experiences. Many educators are therefore at a disadvantage when trying to understand the complexities, sophistication, and resilience of Indic Civilization, particularly the tremendous pressures and dynamic changes that have occurred in Hindu/Indic traditions through the millennia. Since teachers generally have inadequate academic preparation to teach about India, the focus in our classrooms is often centered on the three P’s: population, poverty, and pollution–the usual perspective found in popular media treatments of modern India.

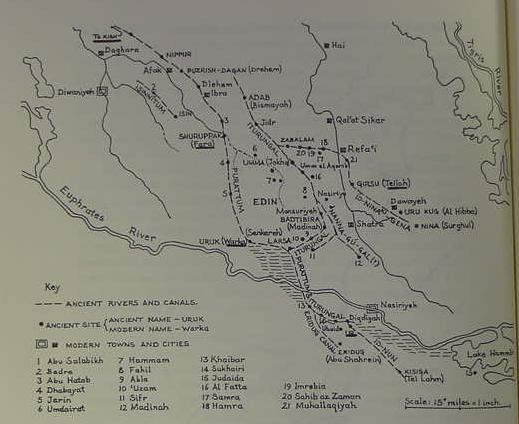

Following the chronology of the World History curriculum from the “Cradle of Civilization” approach, teachers often highlight the Indus-Saraswati Culture while studying Ancient River Valleys. Excavated ruins from the Indus-Saraswati Civilization extend over an area covering half a million square miles, roughly the size of Western Europe–stretching a thousand miles from the Himalayan foothills to the shores of the Arabian Sea. Sites have been found in western Afghanistan near the Iranian border, across most of present day Pakistan and much of northwest India, including a large seaport in Southern Gujarat. Salient archaeological and cultural characteristics link these far flung sites: the uniformity of building styles and materials, advanced urban planning, a uniform standard of weights and measures, hundreds of small seals carved from soapstone and decorated with a wide variety of animal figures, and an as yet undeciphered script. The symbols on these many small seals such as the Pipal or Bo tree, the Brahma bull, the swastika, the trident, serpents, tigers, and a male figure in a yogic or meditative position, often referred to as a “Proto-Shiva”, are still sacred to modern-day Hindus.

High School level textbooks often take great interest in explaining about the amazing drainage system of these 5000 year old urban sites. Many dwellings were equipped with bathrooms that had facilities for showering as well as a toilet. The sewage was channeled out of the private houses to covered canals that ran alongside the public roadways. This hygienic sewer system was far more advanced than anything found in contemporaneous urban sites in the Middle East and even more efficient than can be found in some less developed areas of modern India.

Many teachers in American high schools take the time, during the first weeks of a World History course, to teach about this remarkable culture that thrived for thousands of years with an economy based on commerce and agriculture. Goods sent from the Indian Subcontinent to Mesopotamia and Sumeria, 4,500 years ago, included luxury items such as teak and sandalwood, cotton, sesame oil, etched carnelian beads, lapis lazuli, precious and semi-precious stones and bronze ware. DNA testing has shown that cotton used for wrapping a mummy in an Egyptian pyramid dated 2400 BCE was of Indian origin. There are cuneiform records indicating that even peacocks were exported to the Fertile Crescent thousands of years ago. These are facts that make history fascinating. However, the treatment of the Indus-Saraswati Civilization may be one of the only positive representations of India offered to students until they get to the modern period, when most teachers will take up the topic of Mahatma Gandhi and his influence on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. The rest, several millennia of Indian history, is often skipped because of the teacher’s lack of familiarity or shortage of time.

When topics about India are discussed in American classrooms, one of the most common themes is to focus on the Caste System as the defining feature of Indic Civilization, the lens, as it were, through which a foreigner can understand Hinduism. This is the usual approach, not only in World History and World Geography classrooms, but in university courses as well. At the high school level students sometimes play games in which they draw lots to determine into what caste they have by chance been born. The students must abide by prescribed hierarchical rules that proscribe certain behaviors and allow specific privileges to a select group, namely the “power-hungry dogmatic Brahmans”. The untouchables are banished to one corner of the classroom or forced to stand outside in the hallway.

American students, who are taught from grade one that equality is the basis of our democratic society, will inherently feel negatively towards the privileged Brahmans. Teachers consider the game successful if the students playing the role of the upper castes, gleefully lord their status over their classmates, commanding them to do demeaning chores. The luck of the draw determines their caste, their fate. There is little discussion of the concepts of karma and samsara upon which the caste system is based.

Karma is often erroneously defined as chance, fortune, fate, or coincidence, when it is more aptly the sum total of a soul’s experiences. Our Karma is the residue or residual energy created by the power of our thoughts, words, and deeds–this energy determines the future trajectory of our soul’s path. Karma has been likened to little specks of dust that attach themselves to the pure white light of the soul and color and distort our perceptions, which then create our understandings, thus determining how we experience and respond to our lives. It is the result of an individual’s free will–cause and effect– that determines his or her destiny… not random luck.

Samsara refers to the “rounds of rebirth” through which a soul must pass in order to burn off accumulated karma and transcend to higher states of consciousness. Our birth family, which according to this system of thought we consciously choose at the time of conception, as well the personal challenges we will face, including the strengths and weaknesses of our character, are determined by our past thoughts and deeds. In this system each individual is responsible for his or her own fate or destiny. There are no accidents of birth–poverty or riches, a sorrow-filled life or one full of joy, traits such as kindness or cruelty, are determined by our own previous actions and intentions. However, it is important to understand that karma is not etched in stone and can be altered by conscious efforts toward self-realization. Each soul is on a journey that will ultimately lead to enlightenment. Our dharma, determined by our accumulated karma, is more than mere chance or luck. It is an intimate, individual spiritual path or calling, the unfolding of which is unavoidable and also a sacred duty.[iii] In the ancient past, caste was not determined by birth but rather by ability. This is one important historical caveat about the Caste System that is rarely explained to students. Historically there was a high degree of caste mobility, and interrelationships between groups were in constant flux. Many famous characters in Indian history, such as Valmiki who wrote the epic The Ramayana, are referred to as Brahmins, though Valmiki was actually born in a low caste family. Numerous famous dynasties were founded by men who were born into the servant caste and due to their great deeds became kings–the strength of their personalities determined their caste not their parentage. Many scholars point out that through census data formulated to serve the colonial project, and a quota system designed to divide and rule, the British helped to reify the Caste System. Caste identity was, in the distant past, and is even now, far more adaptable and far less codified than is understood in World History textbooks.

If being born in a certain caste is by chance, like the drawing of lots, then it is certainly cavalier and unfair. But, if the caste system is explained in the context of the broader epistemology, including a discussion of dharma (duty, personal spiritual path) andkarma, then the original concept–dividing the work of society up according to the skill and predilection of the individual–does not seem inherently evil but has a rationale, which is seldom explained to school children.

The Caste System, as taught in American classrooms, is represented as the exact opposite of our democratic institutions. If a rigid Caste System is employed to explain the primary expression or essence of Indic Civilization, it makes that culture seem heartless and quite unfair and does not further the understanding of the fluidity and mobility inherent in Hinduism. This critique is not offered as an apologist for the Caste System but as an alternative to negatively objectifying caste as the evil other that ultimately becomes the hallmark of Indian civilization. In a survey of high school level World History textbooks, I found that more space is devoted to the caste system than all the other characteristics of Hindu India combined, such as their art, literature, architecture, philosophy, economics, politics, and the culturally rich and diverse population.

In textbooks, few other aspects of Hinduism are considered as relevant or dealt with in comparable depth as is the Caste System. What is rarely mentioned or downplayed are India’s post-independence efforts toward national integration of its minorities and low caste citizens. Caste was made illegal by the Indian constitution in 1950. But just as the Civil Rights Amendment of 1965 did not immediately end racism in the USA, the legal prohibition against caste prejudice did not automatically end centuries of social discrimination. Instead of objectifying the Caste System as a curiosity to be deplored, teachers should draw parallels between caste-based discrimination and the tremendous obstacles that poverty stricken inner-city minority families must face to overcome low class status in the United States. Affirmative Action programs exist in both countries and are actually written in to the Indian Constitution.

From the perspective of Western Civilization, which we regard as liberal and egalitarian rising from the Enlightenment, we condemn hereditary castes. Yet, our own societies have a similar past–divine right to rule, inherited aristocracies and sharp class inequities. In all countries, East and West, there are social divisions and vast differences in economic classes that persist, despite the Reformation, Humanism, Marxism, or Capitalism. The Brahman priest is a handy scapegoat to salve the Western conscience and assert our moral superiority over this type of religiously sanctioned inherited status. In later Sanskrit literature there are ironic stories about “stupid Brahmans,” but the spiritual powers of such saintly figures as the sages, Vishwamitra and Valmiki, were considered essential to the survival of the state.

In classical India, Brahmans were charged with the maintenance of religious and societal continuity. There were instances of corrupt Brahmans and Hindu history has condemned them. However, countless Brahman priests undoubtedly took their duties to the community seriously as well as their own personal sadhana or religious practice. In most texts written in the West, Brahmans are uniformly shown as irrelevant hangers-on to the royal court and exploiters of the people.

For example, one textbook that I surveyed, World History: People and Nations, by Anatole G Mazour and John M Peoples, published by Harcourt, Brace, Javonovich in 1990, stressed that moral conduct was unimportant to the Aryans. Which for those familiar with the relevant literature, is easily refuted by the many Sanskrit eulogies to noble and virtuous character. In fact, in the Hindu law books, Brahmins are given harsher penalties than are given to other castes for the same crime. Brahmins were held to a stricter moral code. This was not imposed upon them; Brahmins wrote the law books.

The Mazour-Peoples textbook goes on to explain that during Brahmanic rituals, “The important point was to perform the ceremony properly. The good qualities of the person performing it did not matter.” This implies that Brahmans were not bestowed with adequately “good qualities,” when in fact, according to Vedic tradition, Brahmans had to be in a state of ritual purity to perform the ceremonies, which included proper behavior. Statements such as this reinforce the perception that moral conduct, as found in Indian philosophy, is relative and unimportant. Compared to the later Semitic traditions, with their clearly articulated and specific lists of do’s and don’ts, Hinduism can appear to have fluid views of morality when if fact there are detailed codes of behavior–honesty and trustworthiness are highly valued.

Several times this World History textbook calls the moral character of the Brahman priests into question. It states, “priests, called Brahmans, prepared the proper ceremony for almost every occasion in life and charged heavily for their services.” However, many references from Vedic sources indicate that the majority of Brahmans were poor and often took only alms for their services. Obviously, in later periods, many Brahmans became rich and powerful, and some were corrupt. But the fact that the authors state categorically that they “charged heavily for their services” omits the other side of the picture, knowledge of which is essential for a well-rounded understanding of Brahmans in the Vedic period.

In the post-Enlightenment West, politics and government–political economy–are primary in the historical narrative. The place of religion and its role in the everyday functioning of historical and contemporary Indian society is not adequately addressed. Brahmans are therefore always suspect and unnecessary. A well-known historian of India, Stanley Wolpert, wrote, Brahmans were “guardians and interpreters of that sacred lore,” and as “officiators of the royal sacrifice, the Brahman priesthood maintained its special privileges and courtly influence.”[iv] Though this at least allows the Brahmans some social worth, there is a tone indicating their ultimate political uselessness and economic self-interest. However, on the ground realities, the rulers and the merchants the farmers, and even the low caste laborers depended on the Brahmans for spiritual guidance and advice. The vast majority of Brahmins were not hangers-on at the royal court. Brahmins were scholars. They preserved and passed on the sacred texts ensuring their survival through the ages. It could be said that Brahmins are the main reason that Vedic knowledge and Hindu philosophical treatises are still extant, after centuries of foreign occupations, and the vicissitudes of a hot climate with torrential seasonal rains. It was after all, their duty or dharma to preserve and transmit the Vedic/Indic traditions.

Students should be informed when discussing the Caste System, that modern Hindu teachers such as Swami Vivekananda, who visited the USA in the 1890’s, Shri Aurobindo, a revered twentieth century philosopher and vocal advocate for Indian independence, and also the well-known leader Mahatma Gandhi, have been at the forefront of removing caste from Indian society. Anti-caste movements in modern India include the Arya Samaj, founded in 1875, the largest religious organization in India, and Swadhyaya, a popular religious movement devoted to social causes founded in 1954. The current ruling party of India, the BJP (Bharatiya Janata Party) rejects caste and has made an effort to give prominence to leaders from lower classes. There are socio-religious organizations in India working to open the Hindu priesthood to members of all castes. Though caste continues to be a problem and caste conflicts can occasionally erupt in violence, much like racial violence in the U.S., there are many on-going reform efforts associated with Hindu social, religious and political movements.[v] Another field applied to the study of India that can be shaped to offer primarily negative views of the society is the discourse on the condition of women. The role that women played in the independence movement is rarely discussed in classes, nor is the fact that Indian women continue to be deeply involved in politics. Significantly, at the localpanchayat, village council level, over fifty percent of democratically elected gram pradhans, village headmasters (mayors) are now women. After independence in 1947, women were given the franchise and didn’t have to wait for the suffragette or the women’s liberation movement to earn their constitutional rights. Additionally, there is currently a bill in parliament to amend the constitution and reserve thirty percent of the seats for women in the Lok Saba (the democratically elected “lower” house of the Indian parliament). Though there are on-going debates about how those reservations should be implemented, and the bill has not yet passed, it can be assumed that it will be a long time until thirty percent of the members of the U.S. Congress are female.

According to most Americans, women in India are to be pitied. The positive social progress made by many Indian women in the twentieth century is usually ignored. The very gradual and much maligned development of the Suffragette movement in the U.S. is rarely compared to the correspondingly slow process of upliftment of modern Indian women. The image prevails that if the unfortunate female in India survives a deprived childhood she is likely to be burned in a dowry death after her forced marriage to a complete stranger. Indian women are shown as downtrodden and powerless victims, unlike American women who have more freedom. Indira Gandhi is seen as an anomaly.

Indian feminist scholars often complain that the production of the “third world woman” in Western feminist discourse creates an image of Hindu women as victims of oppressive traditional structures and denies them any agency over their own lives. Indian feminists argue that there are culture differences in terms of oppression and not all women in the world want to be “liberated” by a universalizing Western white middle-class feminist perspective. They claim that focusing on patriarchal oppression alone, and discounting economic and political disempowerment which are also prevalent in Western, predominately Christian societies, serves to continue the ethnocentrism of postcolonialism.

One highly inflated stereotype that is regularly used to describe Indian/Hindu cultural practices is the discourse regarding sati, or as the British spelled it, “suttee”–the burning of widows on their husband’s funeral pyres. Sati has never been widely practiced in India, and in fact in the modern period is very, very rare. Defining Hindu practices through a discussion of sati, is no more accurate than defining Christianity by delving at length into the “Burning Times” in Medieval Europe when as many as nine million women, and even children, were burned at the stake as witches through the encouragement and official approval of the Christian Church. The burning of women does not define Christianity any more than the burning of widows defines Hinduism–both are long discarded practices of the past.

The British justified their exploitation of India by the White Man’s Burden, which often meant rescuing “Brown women” from “Brown men.” Madhu Kishwar the editor of the Indian feminist journal, Manushi, wrote,

“Our erstwhile colonial rulers who needed the pretense of being on a civilizing mission here to justify their brutal reign had a vested interest in identifying select criminal acts and projecting them as Indian traditions in need of reform. They began this cultural invasion by deliberately targeting a few cases of young widows in Bengal who were forcibly burnt on their husband’s pyres, calling those murders sati and banning it by law, so they could appear as agents of a superior civilisation rescuing victims from a savage culture. They even called their mission the White Man’s Burden! Thereafter, the supposedly miserable plight of a newly invented creature called the Indian women became emblematic of the inferior civilisation and culture of the Indian people.”[vi] The popular media in the West often runs stories about “dowry deaths”, when women are murdered by their in-laws because of blind greed. Often the media’s explanation of such criminal behavior is blamed on inherent anti-female bias in Hindu society. Yet the cases of “bride burning” or “dowry deaths” are few and far between in a country with a billion population. Wives and girlfriends murdered by their husbands or significant others are, all too common crimes, certainly not unknown in modern Western countries. But such crimes are carried out by rogues and have no more to do with Hinduism or the Hindu way of life than they do with Christianity or the American way of life.

But in the media, “dowry deaths” are sensationalized and are often given worldwide publicity particularly by proselytization groups in an effort to denigrate Hindu traditions and Indian society. In contrast, crimes in America such as the burning of Black churches, or hate crimes against homosexuals, or wife murdering to collect insurance, or wife battering, of which there are thousands of cases each year, are treated as secular crimes and receive very little or no publicity. We do not define American society with images of domestic abuse. Introducing American students to India through a discussion of dowry deaths is as unrealistic as teaching school children in India about America by focusing primarily on domestic violence, as if it is the defining characteristic of either society.[vii]There are criminal elements in every country that victimize women and children. In our classrooms, many conscientious teachers strive to present non-biased materials in their classes. Unfortunately, often recommended readings, such as May You Be the Mother of a Hundred Sons: A Journey Among the Women of India [viii] are highly stereotyped and use the untenable convention of comparing the lives of poor village women in India with the lives of middle class urban American women. Naturally, the village women seem less free and independent. A more appropriate comparison would a comparison of village women in India with poor women in rural Appalachia, or upper class women in Bombay with their counterparts in urban America.[ix] Sometimes the textbooks themselves can undermine the teachers’ efforts.[x] For example, this statement in large bolded italics meant to stimulate interest on the first page of the chapter about India from a World History textbook, “Although many Hindu rituals no longer exist in India, some, such as walking across a bed of hot coals or lying on a bed of nails, are still practiced to gain forgiveness for sins or to build spiritual control. They continue to intrigue outsiders who have never experienced the rich cultural diversity of India.”[xi] This implies that though Hinduism seems to be fading out in India some strange “rituals” are commonplace and “still practiced”. After a hard day at the office, the banker or farmer comes home and walks across a bed of hot coals before dinner. In reality, most Indians have never seen, let alone tried, this type of tapasya, mortification of the flesh, unless they have gone to a Kumbha Mela or other spiritual fair where Sadhus and holy men may indeed perform these tricks. This casual statement leads the naïve reader to assume that these rituals may be widely practiced in modern India, when they are actually very rare.[xii] Making this sensationalist comment in bold italics at the very beginning of the chapter on India immediately creates an exotic picture in the mind of the student whose Indian teenage counterpart, after doing his or her homework, lies around on a bed of nails watching ZTV (India’s version of MTV). If this book is the only source of information about India available to the students, they may assume that Indian teens regularly walk on coals and sit on nails. Perhaps such tapasya will become a fad in the U.S. much like body piercing and painting the hands and feet with henna have become popular.

Wild fictitious accounts about India, such as eating monkey brains and eyeballs and other strange practices portrayed in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, often find their way into the classroom through the backdoor. With films such as Schindler’s List andAmistad, Hollywood is writing the scripts for our historical narratives, but when they get it really, really wrong, like Spielberg did in Temple of Doom, the negative images can have pervasive repercussions with unexpected longevity.

————————-

“Exchange between educators, on how to teach India in USA schools.”

The special Issue of the journal, “Education About Asia,” that was sponsored by The Infinity Foundation in 2002, had an essay by Yvette Rosser (titled, “Temple of Doom in the Classroom”) critiquing the portrayal of India in American World History classrooms and textbooks. Prof. David Stone wrote a letter to the editor of the magazine to criticize Rosser’s article about using stereotypes in when teaching about India. Yvette Rosser was asked by the editors of EAA to give her response to Stone’s critique. Both the letter by David Stone and Rosser’s response are below. This shows how well-entrenched the bias is; so much so that when someone calls for a change there is criticism of such attempts.

Letter by Professor David Stone, in “Education About Asia,” Fall 2002

Kansas State University

Department of History

208 Eisenhower Hall

Manhattan, KS 66506-1002

March 7, 2002

Dear Editor:

Yvette Rosser’s article “Temple of Doom in the Classroom” is admirable in its intent: to dispel negative stereotypes about South Asia. Her proposed solution, however, leads to the opposite extreme by minimizing South Asia’s very real social problems.

For example, Rosser dismisses sati as “never . . . widely practiced” and today “very, very rare.” As dowry deaths are likewise “few and far between,” there is no basis for an accusation of an “inherent anti-female bias in Hindu society.” As a result, she argues, it would be as unfair to judge India by sati and dowry deaths as it would be to judge the United States by domestic violence.

This misses the point. Rosser is certainly correct that sati is extraordinarily rare, but after the 1987 death of Roop Kanwar on her husband’s funeral pyre, hundreds of thousands came to worship at the site. While many condemned Kanwar’s death, too many others publically celebrated it, something that could not be said of her proposed parallel, American domestic violence. This attitude needs to be explored, not minimized.

True multicultural education should be based on an honest and analytical appraisal of other cultures, both their positives and negatives. We do our students no favors if we teach them that all aspects of all cultures are equally praiseworthy. Better to expose them to the writings of Ram Mohun Roy and contemporary Zadian feminists than to pretend that sati and dowry deaths are not worthy of attention.

David Stone

History Department

Kansas State University

Response by Yvette C. Rosser, in “Education About Asia,” Fall 2002

Re: To a Letter to the Editor written by Professor David Stone, Kansas State University

The EAA article, Temple of Doom in the Classroom proposed strategies for high school teachers to make India relevant to their students, suggesting ways to resist essentializing cultural differences or reifying the exotic as the norm. By contextualizing social oppression and sexism within the discourse of human rights, relating inequities in India to similar problems in Western society, educators can avoid stereotyping class-based discrimination and gender violence as uniquely Hindu. Using sati to narrate Hinduism is tantamount to viewing Christianity through the lens of witch burning.

David Stone contends this approach leads “to the opposite extreme by minimizing South Asia’s very real social problems”. Conceding that “sati is extraordinarily rare”, Stone mentions Roop Kanwar, who died “on her husband’s funeral pyre” where “hundreds of thousands” have since worshiped. Clearly, when a teacher only has a week devoted to India’s millennia – from Mohenjo-Daro to Mahatma Gandhi – Roop Kanwar’s murder sensationalizes the rarified event, creating the impression that dowry deaths and sati are innately linked.

According to Stone, parallel popularization “could not be said of American domestic violence”. Unfortunately, a profitable XXX-rated industry graphically objectifies women, glorifying rape, while Charlton Heston, et al. celebrate America’s gun culture, blurring Hollywood and history, as Moses hands the commandments down from the NRA. Natural Born Killers and Pulp Fiction, orgies of violence, were blockbusters. Domestic violence is celebrated by millions of misguided Americans, re: snuff films and kiddy porn. But, should secondary level students in India with only a few days to cover the USA, explore “wider dimensions” of exploitive porn? Classes about the USA in India should not delve on the Davidian compound in Waco, Texas as relevant to beliefs and practices of most Americans. Roop Kanwar is similarly unrepresentative.

Why should students learn that such anomalies are particular to Hinduism, while practicing Hindus are shocked and repulsed? Does it benefit students to learn that “thousands went to her shrine” while millions were appalled, catalyzing a “nation-wide cathartic reappraisal of women’s status”? (Kanwar was drugged, pushed onto the pyre, her family members arrested for murder. See: Radha Kumar, “Chipko to Sati: Contemporary Indian Women’s Movement”, Challenge of Local Feminisms: Women’s Movements in Global Perspective, ed., Amrita Basu, Westview, Boulder: 1995; also Oldenburg, “Roop Kanwar Case: Feminist Responses”, Sati, The Blessing and the Curse: The Burning of Wives in India, ed., John Hawley, OUP, NY: 1994.) After the Kanwar case, federal legislation was enacted providing the death penalty for anyone abetting Sati.

A World History class is often American students’ only exposure to India unless they specialize, at which time senior class seminars might include “Zadian feminists”. Introductory lessons about India should eschew the obscure, the long outlawed, unsavory details of the past, otherwise we disseminate Eurocentristic constructs of a progressive West, where positive changes happen in history, whereas traditional countries like India are frozen in time by moribund customs.

To base this rejoinder in both practice and theory, I forwarded my article and Prof. Stone’s letter to an experienced high school teacher and a professor who has published extensively on women’s issues in India. David Freedholm, from Princeton Day School, NJ, co-author with Arvind Sharma of Hinduism: An Introduction for High School Students (forthcoming), commented, “When students receive comparatively little instruction about India, is it fair to choose sati or dowry deaths as one of the few topics covered?” He added, “Regarding public celebrations of violence – lyrics of popular rap songs violently demean women, but do not represent American attitudes, similarly, Indians oppose sati and dowry deaths.” Freedholm concluded, “The treatment of India in many American classrooms is full of stereotypes. This must be remedied.”

Prof. Veena Oldenburg, Professor of History at Baruch College and The Graduate Center of the City University of NY concurred, “Worshipping guns is as marked a practice as worshipping ‘holy cows'”. Her recent research unpacks “the ‘cultural fingerprints’ discovered at the scene of any crime because the British saw Hinduism as a cruel set of fixed beliefs”. Dowry Murder: The Imperial Origins of a Cultural Crime (OUP, 2002) points out, “U.S. murders of women are proportionate to those in India, done in ‘ordinary ways’ – shooting, strangling, bludgeoning, poisoning, using automobiles to create convenient accidents. In India, fire as a murder weapon creates false resonances with sati and makes the crime ‘cultural’, whereas kerosene stoves are common and forensically, burning is difficult to prove when repackaged as accidents or suicides.”

Oldenburg demystifies contemporary bride burning arguing such violence is traceable to British policies that drastically eroded “women’s entitlements” by “radically redefining property rights” thus negatively impacting precolonial marriage practices “managed by women, for women […] to establish their status”. British documents blamed crimes against women on the caste system, to “cover up the devastation wrought by colonial agrarian policies”. Classroom discussions of sati must carefully disentangle domestic violence from religion.

In an introduction to Western Civilization should school children in India learn that racism is imbedded in Christian culture, with slavery its corollary; that the Bible and the bullet went hand in hand with imperialism and genocide? Such approaches may deconstruct power relations, but if emphasized and sensationalized, they can promote negative stereotypes.

I agree with Dr. Stone that “multicultural education should be based on an honest and analytical appraisal of other cultures”, but as educators we must be clear that gender crime is a social pathology carried out by rogues and has no more to do with Hinduism than Christianity. If not, we do a disservice to inter-community dialogue by perpetuating old civilizational prejudices that have distorted the discourse about India for several Euro-centric centuries.

Sincerely,

Yvette C. Rosser

Department of Curriculum and Instruction

The University of Texas at Austin

—————–

Note this 2015 update of American teachers actually using The Temple of Doom in their social studies classrooms as a learning aid! See this website designed for social studies teacher to use when teaching their students about India.

I was appalled that serious and alert teachers would think this was an appropriate film to use to teach their students about Hinduism and life in India. I wrote an email to the two educators who are the authors of this ‘Indy in the Classroom’ project:

Greetings,

As an educator I saw that you were using popular culture and fiction to teach students social studies, which is usually a good way to get their attention unless teachers are inadvertently using blatantly stereotypical and negative images.

Unfortunately, the film The Temple of Doom is filled with erroneous and negative images of India and Hinduism. It would have been more educationally productive to use this movie as a method to teach students higher-level discriminatory thinking skills to see through the negative Hollywood stereotypes and sensationalism of other cultures. At least you must add a line or two to your lesson plans if using the movie to teach about India… this very important issue!

Please see my article written 15 years ago, but just as valid now. Please add a link from your lesson plans to this page, so teachers will understand that by using Temple of Doomin their classrooms they are teaching negative stereotypes and cultural biases to their students.

“The Clandestine Curriculum: The Temple of Doom in the Classroom”, Education About Asia, Volume 6, Number 3, Winter 2001 (Association of Asian Studies) -discusses common stereotypes found in teaching about India and suggests corrective pedagogical strategies:

also: “Exchange between educators, on how to teach India in USA schools”:

Thank you,

Yvette C. Rosser, PhD.

See this as well:

and part II:

[i] Lappe, Frances Moore. Diet for a Small Planet, Ballantine Books, 1992. [ii] In the context of cultural borrowing, it is interesting to note one of India’s lasting contributions to what has come to be considered the “Western” lifestyle and that was the export of a thick cotton cloth known as “Dungaree” which, in the sixteenth century was sold at a market near the Dongarii Fort in Bombay. Portuguese and Genoan sailors used this durable blue broad cloth, dyed with indigo, for their bellbottom sailing pants, it was soon became popular with farmers and others. [iii] For an excellent resource about Ancient India, see: Ancient India, part of the Ancient World History Program of History Alive! Created by the Development Team of Teacher’s Curriculum Institute, Executive Director, Bert Bower 2465 Latham Street, Suite 100, Mountain View California 94040: 1997. For more information call 1(800) 497-6138 or email at info@historyalive.com. This thick binder is rich with useful activities and ideas and valuable information. An example of the contexts can be found at: http://www.teachtci.com/curriculum/wh6-program.asp [iv] Stanley Wolpert. A New History of India, New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 1997, page 40.

[v] These two books may be of use when seeking to “read against the text” of the usual negative treatment of Indic traditions: S. Kak, The Wishing Tree: The Presence and Promise of India. Munshiram Manoharlal, New Delhi, 2001. This book is based on invited lectures at Stanford Univ and U o California in 2000. The book presents an overview of Indian history with special emphasis on the Vedic period and history of science. It begins with recent archaeological discoveries including the discovery of the rock art and the elucidation of the Indus-Sarasvati cultural tradition. It describes the influence of Indic ideas on modern science. The book is addressed to the layperson and scholar alike. And: G. Feuerstein, S. Kak, D. Frawley, In Search of the Cradle of Civilization: New Light on Ancient India. Quest Books, Wheaton, IL, 1995, 2001. Synthesizing recent scholarship from archaeology and literary analysis, this book dispenses with several jaded and time-worn academic myths about ancient India to create a new understanding. Written in a straightforward style, it carefully presents the significance of ancient Indian civilization and culture for the study of world history. [vii] The following compilation of statistics reflect a dysfunctional aspect of American society: “Somewhere in America a woman is battered, usually by her intimate partner, every 15 seconds. (United Nations Study on the Status of Women, 2000). Somewhere in America, a woman is raped every 90 seconds. (US Department of Justice, 2000). 1 in 3 murdered females are killed by a partner, versus 3.6% of males. (US Department of Justice, May 2000). Pregnant or recently pregnant women are more likely to be the victims of homicide than to die of any other cause. (Journal of the American Medical Association, March 2001). Battering is the leading cause of injury to women aged 15 to 44 in the United States. (US Surgeon General, 1992).” See: <http://www.vday.org/ie/index.cfm?articleID=522>. [viii] Elisabeth Bumiller, May You Be the Mother of a Hundred Sons: A Journey Among the Women of India, New York: Random House, 1990. [ix] For an excellent critique of the book by Elisabeth Bumiller, May You Be the Mother of a Hundred Sons, see the review by Veena T. Oldenburg athttp://sipa.Columbia.edu/REGIONAL/SAI/veena.html, Professor Oldenburg writes, “Out of a single village she extrapolates and conjures up a homogenized larger reality of rural India. All its dull, dusty, changeless tedium is captured in “thick description,” reprehensibly uninformed by the work of several scholars, some of them western women, who have worked in villages nearby that might have tempered her conclusions. Instead she generates for the reader the impression that the poverty, dirt, flies, and the “ways of the 1,000 people of Khajuron are the ways of most of humanity [in India].” [p.76] Bumiller brisk desire to arrive at conclusions on her journey remind me of anthropology’s beginnings under the aegis of colonial rule for “places without history”, to “observe” people and judge their strange, barbaric, and unchanging ways. Unwittingly she manages to revive the old-fashioned view of “the Indian village” as that quintessentially unchanging place that exists outside of history.” [x] Of the numerous textbooks I surveyed, the one that had the most authentic and inclusive treatments of Indian Civilization is: World History: Continuity and Change, by William Travis Hanes, III, published by Holt, Rinehart and Winston of the Harcourt Brace & Company, Austin: 1997. [xi] Mazour, Anatole G., and Peoples, John M., World History: People and Nations(Harcourt, Brace, Javonovich, 1990). The two following letters appeared in the Spring 2002 edition of EAA:

- Letter to the editor from David Stone:

Kansas State University

Department of History

208 Eisenhower Hall

Manhattan, KS 66506 ‑1002

785-532-6730

Fax: 785-532-7004

March 7, 2002

Dear Editor:

Yvette Rosser’s article “Temple of Doom in the Classroom” is admirable in its intent: to dispell negative stereotypes about South Asia. Her proposed solution, however, leads to the opposite extreme by minimizing South Asia’s very real social problems.

For example, Rosser dismisses sati as “never . . . widely practiced” and today “very, very rare.” As dowry deaths are likewise “few and far between,” there is no basis for an accusation of an “inherent anti-female bias in Hindu society.” As a result, she argues, it would be as unfair to judge India by sati and dowry deaths as it would be to judge the United States by domestic violence.

This misses the point. Rosser is certainly correct that sati is extraordinarily rare, but after the 1987 death of Roop Kanwar on her husband’s funeral pyre, hundreds of thousands came to worship at the site. While many condemned Kanwar’s death, too many others publically celebrated it, something that could not be said of her proposed parallel, American domestic violence. This attitude needs to be explored, not minimized.

True multicultural education should be based on an honest and analytical appraisal of other cultures, both their positives and negatives. We do our students no favors if we teach them that all aspects of all cultures are equally praiseworthy. Better to expose them to the writings of Ram Mohun Roy and contemporary Zadian feminists than to pretend that sati and dowry deaths are not worthy of attention.

David Stone

History Department

Kansas State University

- Rebuttal letter from Yvette Rosser:

Re: Letter to the Editor written by

Professor David Stone, Kansas State University

Temple of Doom in the Classroom proposed strategies for high school teachers to make India relevant to their students, suggesting ways to resist essentializing cultural differences or reifying the exotic as the norm. By contextualizing social oppression and sexism within the discourse of human rights, relating inequities in India to similar problems in Western society, educators can avoid stereotyping class-based discrimination and gender violence as uniquely Hindu. Using sati to narrate Hinduism is tantamount to viewing Christianity through the lens of witch burning.

David Stone contends this approach leads “to the opposite extreme by minimizing South Asia’s very real social problems”. Conceding that “sati is extraordinarily rare”, Stone mentions Roop Kanwar, who died “on her husband’s funeral pyre” where “hundreds of thousands” have since worshiped. Clearly, when a teacher only has a week devoted to India’s millennia–from Mohenjo-Daro to Mahatma Gandhi–Roop Kanwar’s murder sensationalizes the rarified event, creating the impression that dowry deaths and sati are innately linked.

According to Stone, parallel popularization “could not be said of American domestic violence”. Unfortunately, a profitable XXX-rated industry graphically objectifies women, glorifying rape, while Charlton Heston, et al. celebrate America’s gun culture, blurring Hollywood and history, as Moses hands the commandments down from the NRA. Natural Born Killers and Pulp Fiction, orgies of violence, were blockbusters Domestic violence is celebrated by millions of misguided Americans, re: snuff films and kiddy porn. But, should secondary level students in India with only a few days to cover the USA, explore “wider dimensions” of exploitive porn? Classes about the USA in India should not delve on the Davidian compound in Waco, Texas as relevant to beliefs and practices of most Americans. Roop Kanwar is similarly unrepresentative.

Why should students learn that such anomalies are particular to Hinduism, while practicing Hindus are shocked and repulsed? Does it benefit students to learn that “thousands went to her shrine” while millions were appalled, catalyzing a “nation-wide cathartic reappraisal of women’s status”? (Kanwar was drugged, pushed onto the pyre, her family members arrested for murder. See: Radha Kumar, “Chipko to Sati: Contemporary Indian Women’s Movement”, Challenge of Local Feminisms: Women’s Movements in Global Perspective, ed., Amrita Basu, Westview, Boulder: 1995; also Oldenburg, “Roop Kanwar Case: Feminist Responses”, Sati, The Blessing and the Curse: The Burning of Wives in India, ed., John Hawley, OUP, NY: 1994.) After the Kanwar case, federal legislation was enacted providing the death penalty for anyone abetting Sati.

A World History class is often American students’ only exposure to India unless they specialize, at which time seminars might include “Zadian feminists”. Introductory lessons about India should eschew the obscure, the long outlawed, unsavory details of the past, otherwise we disseminate Eurocentristic constructs of a progressive West, where positive changes happen in history, whereas traditional countries like India are frozen in time by moribund customs.

To base this rejoinder in both practice and theory, I forwarded my article and Prof.. Stone’s letter to an experienced high school teacher and a professor who has published extensively on women’s issues in India. David Freedholm, from Princeton Day School, NJ, co-author with Arvind Sharma of Hinduism: An Introduction for High School Students (forthcoming), commented, “When students receive comparatively little instruction about India, is it fair to choose sati or dowry deaths as one of the few topics covered?” He added, “Regarding public celebrations of violence– lyrics of popular rap songs violently demean women, but do not represent American attitudes, similarly, Indians oppose sati and dowry deaths.” Freedholm concluded, “The treatment of India in many American classrooms is full of stereotypes. This must be remedied.”

Prof. Veena Oldenburg, Professor of History at Baruch College and The Graduate Center of the City University of NY concurred, “Worshipping guns is as marked a practice as worshipping ‘holy cows’”. Her recent research unpacks “the ‘cultural fingerprints’ discovered at the scene of any crime because the British saw Hinduism as a cruel set of fixed beliefs”. Dowry Murder: The Imperial Origins of a Cultural Crime (OUP, 2002) points out, “U.S. murders of women are proportionate to those in India, done in ‘ordinary ways’–shooting, strangling, bludgeoning, poisoning, using automobiles to create convenient accidents. In India, fire as a murder weapon creates false resonances with sati and makes the crime ‘cultural’, whereas kerosene stoves are common and forensically, burning is difficult to prove when repackaged as accidents or suicides.”

Oldenburg demystifies contemporary bride burning arguing such violence is traceable to British policies that drastically eroded “women’s entitlements” by “radically redefining property rights” thus negatively impacting precolonial marriage practices “managed by women, for women […] to establish their status”. British documents blamed crimes against women on the caste system, to “cover up the devastation wrought by colonial agrarian policies”. Classroom discussions of sati must carefully disentangle domestic violence from religion.

In an introduction to Western Civilization should school children in India learn that racism is imbedded in Christian culture, with slavery its corollary; that the Bible and the bullet went hand in hand with imperialism and genocide? Such approaches may deconstruct power relations, but if emphasized and sensationalized, they can promote negative stereotypes.

I agree with Dr. Stone that “multicultural education should be based on an honest and analytical appraisal of other cultures”, but as educators we must be clear that gender crime is a social pathology carried out by rogues and has no more to do with Hinduism than Christianity; if not, we do a disservice to inter-community dialogue by perpetuating old civilizational prejudices that have distorted the discourse about India for several Euro-centric centuries.

Yvette C. Rosser

Department of Curriculum and Instruction

The University of Texas at Austin

https://yvetterosser.com/2015/05/11/the-clandestine-curriculum-temple-of-doom-in-the-classroom/

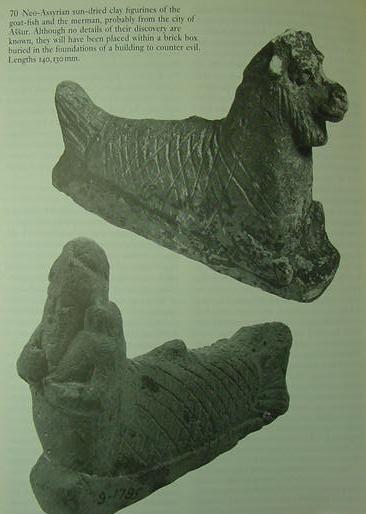

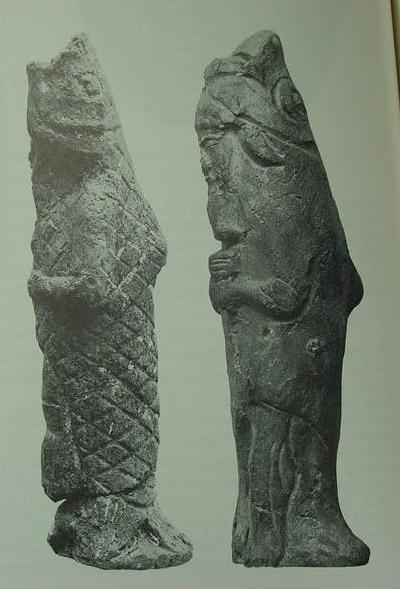

The s'ilpin standing next to the fish-fin hieroglyph-multiplex

The s'ilpin standing next to the fish-fin hieroglyph-multiplex

কাঞ্চন গুপ্ত

কাঞ্চন গুপ্ত

Sarveshi Shukla

Sarveshi Shukla  Aviral Kapoor

Aviral Kapoor  it takes a bit of time2accept new workin PM reality

it takes a bit of time2accept new workin PM reality CHANDRA MOULI H

CHANDRA MOULI H  anshu mathur

anshu mathur

Debashish Adhikary

Debashish Adhikary  Sanjay Singh

Sanjay Singh  Paduvery

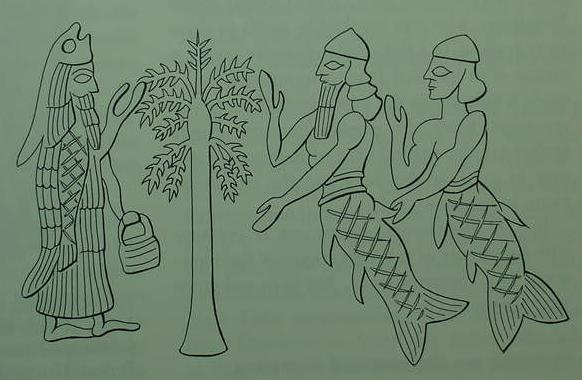

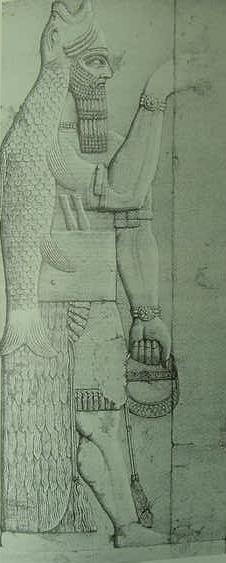

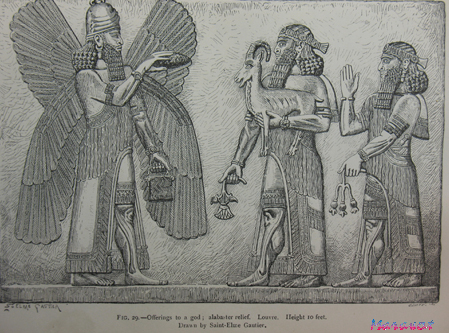

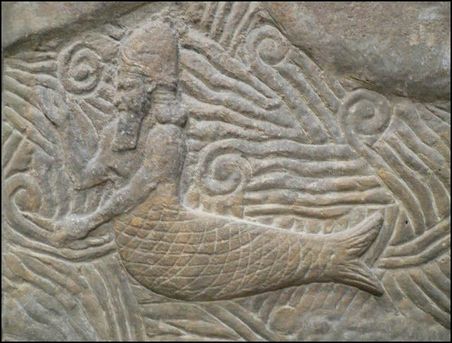

Paduvery  A fish-apkallu drawn by AH Layard from a stone relief, one of a pair flanking a doorway in the Temple of Ninurta at Kalhu. British Museum. Reproduced in Schlomo Izre'el, Adpa and the South Wind, Language has the power of life and death, Eisenbrauns, 2001.

A fish-apkallu drawn by AH Layard from a stone relief, one of a pair flanking a doorway in the Temple of Ninurta at Kalhu. British Museum. Reproduced in Schlomo Izre'el, Adpa and the South Wind, Language has the power of life and death, Eisenbrauns, 2001.

See m1429C

See m1429C

Gudea. Overflowing pot. Sumer.

Gudea. Overflowing pot. Sumer.

Sumerian relief. Louvre.

Sumerian relief. Louvre.  Medallion. Makara, fishes. kara 'crocodile' rebus: khara 'blacksmith' ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron'; ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'metal alloy'.

Medallion. Makara, fishes. kara 'crocodile' rebus: khara 'blacksmith' ibha 'elephant' rebus: ib 'iron'; ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'metal alloy'.

m495G

m495G m1278

m1278 m107

m107 m1169

m1169 m82

m82 m446

m446 m10

m10

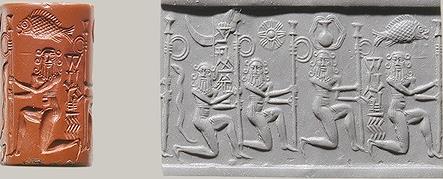

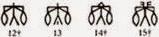

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal'

aya 'fish' Rebus: aya, ayas 'iron, metal' aya dhAL, 'fish+slanted stroke' Rebus: aya DhALako 'iron/metal ingot'

aya dhAL, 'fish+slanted stroke' Rebus: aya DhALako 'iron/metal ingot' aya aDaren,'fish+superscript lid' Rebus: aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal'

aya aDaren,'fish+superscript lid' Rebus: aya aduru 'iron/metal native unsmelted metal' aya khANDa, 'fish+notch' Rebus: aya khaNDa 'iron/metal implements'

aya khANDa, 'fish+notch' Rebus: aya khaNDa 'iron/metal implements' aya kolom 'fish+ numeral 3' Rebus:aya kolimi 'iron/metal smithy/forge'

aya kolom 'fish+ numeral 3' Rebus:aya kolimi 'iron/metal smithy/forge' aya baTa 'fish+numeral 6' Rebus: aya bhaTa 'iron/metal furnace'

aya baTa 'fish+numeral 6' Rebus: aya bhaTa 'iron/metal furnace' aya gaNDa kolom'fish+numeral4+numeral3' Rebus: aya khaNDa kolimi 'metal/iron implements smithy/forge'

aya gaNDa kolom'fish+numeral4+numeral3' Rebus: aya khaNDa kolimi 'metal/iron implements smithy/forge' aya dula 'fish+two' Rebus: aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting'

aya dula 'fish+two' Rebus: aya dul 'metal/iron cast metal or metalcasting'

Ram Madhav

Ram Madhav  কাঞ্চন গুপ্ত

কাঞ্চন গুপ্ত

RVAIDYA

RVAIDYA

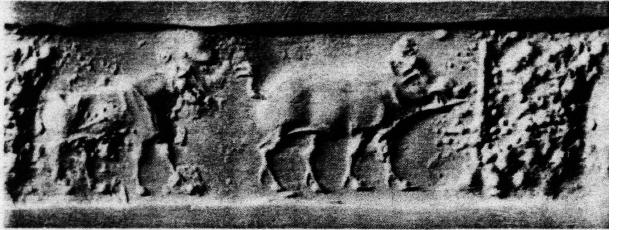

Banawali b-17 Tiger PLUS standard device

Banawali b-17 Tiger PLUS standard device m290 tiger PLUS trough

m290 tiger PLUS trough

h088 Rhinoceros PLUS trough

h088 Rhinoceros PLUS trough

Trough PLUS buffalo/bull

Trough PLUS buffalo/bull

Three-headed: elephant, buffalo, bottom jaw of a feline. NS 91.02.32.01.LXXXII. Dept. of Archaeology, Karachi. EBK 7712

Three-headed: elephant, buffalo, bottom jaw of a feline. NS 91.02.32.01.LXXXII. Dept. of Archaeology, Karachi. EBK 7712

Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar (PTI Photo)

Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar (PTI Photo) Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar speaks in the Lok Sabha in New Delhi on Friday. (PTI Photo/ TV grab)

Defence Minister Manohar Parrikar speaks in the Lok Sabha in New Delhi on Friday. (PTI Photo/ TV grab)

Top Comment

Corruption, fraud, adulteration and dishonesty are in the blood of a majority of Indians. That''s the simple fact.Rohan Seth