A critical review of Rajiv Malhotra’s The Battle for Sanskrit

HarperCollins Publishers India, 2016 ISBN 978-93-5177-538-6

Co-authored by Hari Ravikumar

Before the Great War, Arjuna developed cold feet and Krishna counselled him to lift up his weapons and fight. But how would have Krishna reacted if Arjuna had been over-zealous to battle the sons of Dhritarashtra even before the Pandava side was fully prepared? Perhaps the way Yudhishthira reacted to Bhima’s impatience in Bharavi’s Kiratarjuniyam (Canto 2, Verse 30) – “Act not in haste! A loss of sagacity (viveka) is the worst calamity. Fortune and prosperity comes to one who analyses and calculates.”

In the battle for Sanskrit, Rajiv Malhotra is like an enthusiastic commander of a committed army whose strengths and weaknesses he himself is sadly unable to reconcile. Doubtless there is a battle for Sanskrit and one must wholeheartedly applaud Malhotra’s efforts for Sanskrit. Without hesitation, we shall stand shoulder to shoulder with him and fight this war till the end. We too are opposed to “those who see Sanskrit as a dead language… [and those who] would ‘sanitize’ Sanskrit, cleansing it of what they see as its inherent elitism and oppressive cultural and social structures…” (p. 30). But before the clash of weapons, an objective assessment of our ancient tradition is imperative.

Close to a century ago, Prof. M Hiriyanna – whom Daniel H H Ingalls praised as a “great scholar of whom it might be said that he never wrote a useless word” – said in an address to Sanskrit scholars, “By the application of what is known as the comparative method of study of Sanskrit language and literature, modern scholarship has brought to light many valuable facts about them. It will be a serious deficiency if the Pandit passes through his career as a student altogether oblivious of this new knowledge… The excellences of the old Pandit such for example, as the depth and definiteness of his knowledge, the clearness of his thinking and the exactness of his expression, were many. But there was a lack of historical perspective in what he knew; and he was apt to take for granted that opinions, put forward as siddhantas in Sanskrit works, had all along been in precisely the same form. We may grant that there are some fundamental truths which never grow old; but as regards knowledge in general, change is the rule… Two or three decades ago, our Pandits confined their attention only to the subject in which they specialized, and even there to a few chosen books related to it… But thoroughness is no antidote against the narrowness of mental outlook which such a limited course of study was bound to engender.” (‘The Value of Sanskrit Learning and Culture,’ an essay from Popular Essays in Indian Philosophy).

To ably carry out such an assessment, we must understand Hinduism’s underlying philosophy. The Hindu worldview is that of using a (scriptural) text and then transcending the text (see Rgveda Samhita 1.164.39). On the one hand we have a tradition of the “ever-growing text” and on the other we have a tradition of “transcending the text.” The growing body of knowledge (made possible by the varied and original commentaries of scholars, e.g. Shankara) helps prevent the text from getting outdated. Going beyond the text (as demonstrated by avadhutas, e.g. Ramana Maharishi) helps prevent the text from becoming an imposition.

The means of transcendence may be through text, ritual, or art, but adherents aim to go beyond Form and internalize Content (by means of reflective inquiry into the Self), thus attaining what the Taittiriya Upanisad calls ‘brahmananda.’ This transcendental approach ensures that we neither harbour any malice towards divergent views nor give undue importance to differences in form. It helps us achieve harmony amidst diversity. This quality of transcendence unites the various groups that come under the umbrella of what we call today as sanatana dharma or Indian cultural and spiritual heritage.

Sanatana dharma includes revelation of the seers (Vedas) as well as epics (Ramayana and Mahabharata). The Greek and Roman traditions have epics but no revealed scriptures. The Semitic traditions have revealed scriptures but no epics. Other traditions like the ancient Chinese, Mayan, Incan, etc. have neither. In spite of having such a rich Vedic and epic tradition, sanatana dharma teaches transcendence. The idea of transcending comes neither from inadequacy nor from inability to handle variety. While the tradition respects diversity, its focus is on going within and going beyond.

Malhotra’s intent is noble (and something that we too share) but his understanding of the nature of sanatana dharma as a transcendental system is flawed. He aims to show that Hinduism is exclusivist in its own way and its exclusivism is somehow better than other exclusivist faiths like Christianity or Islam (see his previous book,Being Different). His line of reasoning would reduce this battle to a Communist vs. Theologist type scuffle (and yet he accuses his enemies of being anti-transcendence; see pp. 97, 116). His approach goes against Gaudapada’s observation – “Dualists have firm beliefs in their own systems and are at loggerheads with one another but the non-dualists don’t have a quarrel with them. The dualists may have a problem with non-dualists but not the other way around.” (Mandukya Karika 3.17-18)

Malhotra’s understanding of Sanskrit and Sanskriti seems second hand since he puts a premium on form (rupa) as against content (svarupa) and uses pseudo-logic instead of non-qualified universal experiential wisdom to counter the enemies (see pp. 44-49 for an elaborate but hazy diagnosis of the problem).

Further, he is also confused with some of the basic terms like sastra, kavya and veda. The irony is that Malhotra himself doesn’t know as much formal Sanskrit as the Indologists he is out to battle. Now, this is not a problem for a spiritualist who is unaffected by form. But Malhotra is fighting the battle on the arena of form, so he has no option but to become thorough with Sanskrit and Sanskriti in form.

In the Indian debating tradition, the first step is to establish the pramanas (the methods and means by which knowledge is obtained). Then we embark onpurvapaksa (a study of what the opponent says) and finally move to siddhanta (a rebuttal to the opponents; also called uttarapaksa). The first imperative step of establishing pramanas is missing in The Battle for Sanskrit.

Malhotra claims to merely perform purvapaksa, but in places where he unwittingly tries his hand at siddhanta, he falls short. In other places where the siddhanta is well-reasoned, it is entirely borrowed (from scholars like K S Kannan, Arvind Sharma, T S Satyanath, etc.) Perhaps bringing them on board as co-authors might have salvaged this work in terms of the quality of siddhanta (and also the diagnosis of the problem). However, Malhotra deserves credit for attempting a purvapaksa. And this is why The Battle for Sanskrit is a valuable work.

Backdrop to the Battle

Hinduism has had a long history of dissent. Even in the earliest works, the Vedas, which lay the foundation for our tradition, we can see disagreement and conflict. Our ancestors were comfortable with such differences in opinions and ideas. They did not perceive it as something strange or repulsive since they were constantly and successfully finding harmony and reconciliation amidst diversity. A striking example is the series of exchanges between Yajnavalkya and other scholars in the court of Janaka (Brhadaranyaka Upanisad 3.9). Our tradition has savants like the Buddha whose disagreements created a whole new system of faith (though spiritually not alien to sanatana dharma).

All through our philosophical, literary, aesthetic, and artistic discussions spread over millennia, we have seen remarkable variance in theories and approaches. However, it is noteworthy that Time has been unkind to theories and approaches that have been against the spirit of sanatana dharma.

Western scholars are familiar with dissent but they often lack a framework to reconcile with the differences and transcend them. While Malhotra respects this spirit, he is unable, unfortunately, to express it clearly in his book.

For Malhotra, the starting point of this battle is European Orientalism. And since he tends to ignore the strong internal differences – often clubbing all insider views as ‘the traditionalist view’ (see p. 36, for example) – his argument is rendered weaker. In the Indian tradition, different schools of Vedanta – advaita, dvaita, dvaitadvaita,shuddhadvaita, vishishtadvaita and others – revere the Vedas equally but claim that the others have misrepresented the Vedas and that only their interpretation is the right one. We find this also in the commentators on the Veda. Consider the commentaries of Skandaswami (10th century), Venkatamadhava (12-13th century) and Sayana (14thcentury). In the 19th century, Dayananda Saraswati gave a completely different interpretation to the Vedas while paying due respects to it. Similarly, in the 20thcentury, Sri Aurobindo gave his own esoteric interpretation to the Vedas. Who is to say what the right version is? Which of these schools qualify to be ‘the traditionalist view’? Who is the ‘ideal insider’?

Once we realize that our own tradition has diametrically opposed views, we must consider the facts. We should rely on universal experience and not on personal revelations. We must operate in the material plane, not a metaphysical one. And we must always remember that a debate can proceed only after the pram??as have been agreed upon by both sides. Here is a historical example to illustrate this point. The great 11th century scholar-sage and proponent of vishishtadvaita, Ramanuja was deeply influenced by the divya-prabandham (divine verses, composed by the twelvealwars of Tamil Nadu) and considered it the ‘tamil veda.’ However, when he wrote his commentaries on the Bhagavad-Gita and the Brahma Sutra, he never quoted from thedivya-prabandham since his opponents did not consider that as a pramnaa.

That said, Malhotra’s analysis of European Orientalism and its latter variant, what he terms ‘American Orientalism’ is reasonably accurate. When the British scholars came in contact with Indian knowledge systems in the 18th and 19th centuries, they faced a worldview vastly different from theirs. Instead of understanding the Indian view in Indian terms, they force-fitted what they observed into the worldview they were familiar with. Added to this, there was the White Man’s Burden that egged them to ‘civilize’ the people they conquered. This led to a gross misrepresentation of the Indian culture and this would later become, ironically, the primary source for educated Indians to learn about their own culture. This viewing of India through the Western lens has given rise to several erroneous conclusions and Malhotra makes this point numerous times in his book (to the extent that he could have saved many pages had he chosen not to repeat himself).

Malhotra makes a thorough analysis of the evolution of American Orientalism, showcasing their strategy of creating atrocity literature against the people they wish to dominate. While his comparison of the two kinds of Orientalism is notable, he begins to falter when he compares the ‘Sanskrit Traditionalists’ and ‘American Orientalists.’ Like we have discussed earlier, there is no single group that one can call ‘Sanskrit Traditionalists,’ and the distinctions Malhotra tries to make are rather shallow and even impertinent. For example, he says that the traditionalists see Sanskrit as sacred while the orientalists see Sanskrit as beautiful but not necessarily sacred. Why this divide between sacred and beautiful?

Also, his suggestion for the revival of Sanskrit is to produce new knowledge in Sanskrit. Is this even practical given that scholars from many mainstream non-English languages (like Chinese, Dutch, French, German, Spanish, etc.) are finding it hard to make a name for themselves in the academic community, which is under the firm grip of English?

When Malhotra speaks about American Orientalism appropriating the Indian Left, some of his claims sound like conspiracy theories. Further, he seems to be ignorant of the voluminous writings of D D Kosambi, Debiprasad Chattopadhyaya, R S Sharma, and Rahul Sankrityayan, who opposed Sanskrit and/or Sanskriti long before this supposed American collusion (and even when he mentions Kosambi and Sharma, it is in passing). And more importantly, he fails to mention (or seems to be ignorant of) the luminaries who have categorically rubbished such attempts – A C Bose, A C Das, Arun Shourie, Baldev Upadhyaya, Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Chidananda Murthy, D V Gundappa, David Frawley, Dayananda Saraswati, G N Chakravarti, Hazari Prasad Dwivedi, K S Narayanacharya, Koenraad Elst, Krishna Chaitanya, Kuppuswami Sastri, M Hiriyanna, Michel Danino, Nagendra, Navaratna S Rajaram, Padekallu Narasimha Bhat, Padma Subrahmanyam, Pullela Sriramachandrudu, R C Dwivedi, Ram Swarup, Ranganath Sharma, Rewa Prasad Dwivedi, S K Ramachandra Rao, S L Bhyarappa, S N Balagangadhara, S R Ramaswamy, S Srikanta Sastri, Shrikant Talageri, Sita Ram Goel, Sri Aurobindo, Sushil Kumar Dey, Swami Vivekananda, V S Sukhthanker, Vasudev Sharan Agarwal, Yudhishthira Mimamsaka… the list is endless. And the few scholars he refers to – like A K Coomaraswamy, Dharampal, G C Pande, K Krishnamoorthy, Kapila Vatsyayan, P V Kane, and V Raghavan – are only in passing.

Tucked away in the second chapter is a veiled disclaimer – “Both Indian and Western scholars have extensively criticized the European approaches towards India that prevailed during the colonial era.” (p. 52) but this cannot, sadly, absolve Malhotra of his blatant disregard to the past masters (in spite of his ostentatious dedication line to “our purva-paksha and uttara-paksha debating tradition…”) Not stopping at ignoring the remarkable scholars of the past and present, in several places in his book, Malhotra directly accuses Indian scholars of either being unwillingly complicit with the enemies (p. 68), or being irresponsible (p. 15), or being uninterested (p. 44), or being unaware of Western scholarship (p. 1). He lacks empathy for the numerous scholars who are deeply involved in their own research – be it a specific aspect of Sanskrit grammar, or the accurate dating of an ancient scholar, or preparing a critical edition of a traditional text. And to top it all, Malhotra writes in several places that he is the first person to undertake such a task (see pp. 27, 44, or 379, for example), which as we know is false.

On the one hand, he is an activist for the tradition’s cause but on the other hand he ignores past masters and looks down upon traditionalist scholars. And it is strange he has not quoted any regional language scholar. He could have gone through the writings in a regional language that he is familiar with, say Hindi, and seen the amount of work for and against Sanskrit that is available.

One can list several Indian scholars who have refuted baseless allegations from the European Indologists, Indian Leftists, and the post-colonial Orientalists. Here are just a few illustrative examples. In Art Experience, M Hiriyanna methodically debunks Max Mueller’s claim that the Hindu mind cannot appreciate beauty in nature. Baldev Upadhyaya’s writings show that the divide between Hinduism and Buddhism is not as sharp as they are made out to be. In his remarkable work On the Meaning of the Mahabharata, V S Sukhthankar provides a masterly rebuttal to Western scholars who accuse the Mahabharata of being chaotic and lacking in clarity; he methodically debunks all perverse Western theories about the epic (and Bankim Chandra Chatterjee long before, in his Krishna Caritra). Sita Ram Goel (and Swami Vivekananda long before) wrote extensively about the damage done to India by Islamic invaders. K S Narayanacharya in his extensive writings has systematically refuted accusations hurled at the Vedas and the epics. In his Politics of History, Navaratna S Rajaram describes the misrepresentation of Hinduism by Western scholars. In their brilliant research papers, Kuppuswami Sastri, P V Kane, V Raghavan, K Krishnamoorthy, and Rewa Prasad Dwivedi have defended Indian aesthetics and poetics from Western attacks. In response to ?am B? Joshi’s extensive but baseless theories about the Vedas, Chidambarananda wrote a detailed rebuttal. Equally, K A Krishnaswamy Iyer (in Vedanta: The Science of Reality) and Sri Sacchidanandendra Saraswati (in Paramartha Chintamani and Vedanta Prakriya-pratyabhijña) refuted all Western systems of philosophy (up to the early 20th century) and established a Vedantic tradition in a highly objective historical perspective.

This is not a new battle. It has been fought before, and won before. We (Malhotra included) have to humbly submit to the fact that we are merely trying to continue the great scholarly tradition.

‘Pandit’ Pollock

The assiduous efforts of Malhotra in writing The Battle for Sanskrit bears fruit in one department – a meticulous analysis of the works of Sheldon Pollock. While it is the saving grace of the book, it is also an indicator of Malhotra’s obsession with Western academia, to the extent that the reader gets the impression that Hinduism will not survive unless Western academia views it in a better light.

Sheldon Pollock is arguably the most influential and well-connected Indologist in the world today. And his agenda is clear, as Malhotra points out – “…to secularize the study of Sanskrit.” (p. 79). Pollock uses a new brand of philology (study of the history of a language) to help liberate Sanskrit from its supposedly oppressive and manipulative nature. He is also dead against any kind of Sanskrit revival (for instance, the work of Samskrita Bharati, the premier organization that teaches conversational Sanskrit and has been responsible for promoting Sanskrit in the modern world). Pollock sees the Ramayana as a literary work that was composed in order to oppress the masses. He also tries to show that there was a conflict between Sanskrit and the other regional languages of India (The word that Pollock and others often use is ‘vernacular’ languages; ‘vernacular’ is a 17th century word that was derived from the Latin vernaculus, meaning ‘native,’ which was originally derived from vernus, ‘a slave who was born in the house and not in a foreign land.’) Pollock also claims in a roundabout way that Nazism and fascism were inspired by Sanskrit (see pp. 84-86 for a summary of Pollock main arguments; it is important to note here that such arguments have been made much earlier by scholars like Rahul Sankrityayan, in much more vociferous terms, and have been refuted by many scholars).

While it becomes clear from Malhotra’s study of Pollock that the latter’s intent is far from noble, there is no use playing a blame game. One has to counter Pollock with facts, and that will come only from a deep study and understanding of the Indian tradition. While there are some instances in The Battle for Sanskrit where Malhotra uses the works of other scholars and provides meaningful refutation to Pollock’s writings, there are instances where Malhotra has erred (see Appendix A), made untenable arguments (see Appendix B), is ignorant of earlier works and divergent views (see Appendix C), and has missed out critical points to counter Pollock (see Appendix D). While we have prepared an exhaustive list, we have provided only a representative one in the appendix.

Conclusion

The battle for Sanskrit and Sanskriti is not a new one. San?tana dharma has survived years of onslaught from many quarters in many guises. But this doesn’t mean that we should ignore the current threats. Malhotra has given a new shape to the debate and because of his influence, this message has spread widely. As he himself writes, it is hoped that more Indian scholars will get on board and provide fitting responses to Malhotra’s red flagging of problematic areas in Pollock’s discourse.

In the Upani?ads, we find a fascinating framework of three epistemologies –adhibhuta, adhidaiva, and adhyatma. Anything that pertains to the world of matter isadhibhuta (operates at the level of universe). Anything that pertains to the world of beliefs is adhidaiva (operates at the level of religion). Anything that pertains to the inner Self is adhyatma (operates at the level of the individual). Pollock tricks his readers using adhibhuta but while countering him, Malhotra confuses adhidaiva foradhyatma, thus taking the discussion nowhere. Added to that, he quotes views that are good but only partially correct, confusing the issue further.

In addition to showing the malicious motives of some of the Western Indologists, it is important to pin-point their errors they have made in translation (Dr. Shankar Rajaraman is currently working such a project) and in understanding our tradition (see the writings of Manasataramgini). We should also be objective about our own tradition and that will help us recognize the chinks in our armour (see the writings of D V Gundappa). When we enter into a debate with our opponents, we must ensure that the pramanas are mutually agreed upon. We should never forget that our tradition espouses universality and not exclusivity (see Appendix E). Finally, it is important for us to become an affluent, scientifically advanced, geo-politically influential culture if our words are to be taken seriously. We must strengthen ourselves by ushering in a strong work culture, aiming for greater efficiency, and laying emphasis on merit.

While we recognize the battle and continue to fight on the side of Sanskrit, we must also realize that diversity is the way of the world and should learn to tolerate opposing views, however different they might be from our own. And indeed, when we encounter intellectual dishonesty in scholars who tried to canonize their views as facts, we shall combat them with facts.

That said, if we allow ourselves to be too troubled by such scholars and such debates, we will never be able to attain the peace of a contemplative mind. While we shall respect scholars like Malhotra and Pollock, we shall also remember Shankara’s insightful words: “The web of words, akin to a great forest, deludes the intellect. Seek thus to know the true Self, O seeker of Truth!” (Vivekachudamani 60).

~

Thanks to Dr. Koti Sreekrishna, Sandeep Balakrishna, Dr. G L Krishna, Arjun Bharadwaj, and Shashi Kiran for their timely and insightful feedback. Special thanks to Dr. G L Krishna for writing a short piece that brilliantly captures the universality of our tradition (see Appendix E).

Appendices

A. Partially Incorrect Claims

- “Shastras arise out of, and are deeply intertwined with, the metaphysics of the Vedas. Kavyas are less formal and hence more accessible at the popular level.” (pp. 37-38)

Malhotra’s understanding of the terms sastra, kavya, and veda are hazy. But he opposes Pollock’s understanding of sastra (pp. 114-15; incidentally, even Pollock doesn’t understand what sastra is). Any organized body of knowledge is sastra; it serves two purposes – to govern and to reveal. A system of grammar is a sastra. It tells us what is the right usage (governs) and shows us new connections (reveals). A sastra may or may not be connected to the Vedas. Any creative work that evokesrasa (art experience; aesthetic delight) is kavya. When it comes to the purpose of kavya, traditional scholars differ in their views. While Malhotra quotes Kuntaka’s Vakrokti jivita (p. 132) to show the harmony between veda, kavya, and sastra (and condemns Pollock for seeing them as separate; see p. 85 for example), how would he reconcile with some of the statements of our own traditional aestheticians – Bhattanayaka’s declaration that kavya finds its fulfilment only in rasa, or Dhananjaya’s disdain for seeking a message in a work of art (Dasarupaka 1.6), or Hemachandra’s views on the utility of kavya in Kavyanushasana? Mamma?a says that veda, kavya, itihasa, andpurnana have different operations (Kavyaprakasha 1.2). Bhavabhuti goes as far as to say, “What is the use of extensive learning in the Vedas, Upanisads, Samkhya and Yoga while telling a story? The depth and magnanimity of words that come from its usage and meaning – this is the true indicator of felicity of learning and composition.” (Malatimadhavam, Act 1, Verse 8).

M Hiriyanna says in Sanskrit Studies that Vedas are daivakendra (deity-centric) whilekavya is jivakendra (life-centric). While the Vedas also have elements of kavya, it focuses on the divine and not on humans. Of course, at a deeper philosophical level, everything leads to ananda, we should adhere to the respective sastra–maryada and recognize the operational differences. If not, no specific research can proceed in those areas.

In the field of Indian poetics, rasa is the greatest means of art appreciation at the level of prabandha. However, guna, alamkara, riti, vakrata, dhvani, aucitya, etc. working at the levels of varna, pada, vakya, etc. become relevant in their respective domains. This is so even in the case of satta-caaturvidhya (the four levels of truth) dealt in Vedanta. As long as the paramarthika is not challenged, the other sattas like pratibhashika,vyavaharika and aakalpaka are held extremely relevant in their own spheres. We can give the analogy of physics – classical Newtonian physics and modern Einsteinian physics operate at different levels. Within their respective frameworks, both are true.

- “Darshana (philosophy) is an intellectual method of acquiring analytical capabilities.” (p. 98)

Darsana (‘visionary orientation,’ ‘point of view,’ or ‘school of philosophy’) is more sophisticated than that. Further, it has both a tarka-pada (intellectual element) and akriya-pada (experiential element) unlike Western philosophy which is merely an intellectual exercise.

- “Dhyana (meditation) is available without the need for analysis since it is entirely experiential.” (p. 98)

If this is the case, how do we account for the fact that dhyana has been analyzed extensively on the basis of experience (known as srauta-tarka)? Ved?nta offers a path of sravana, manana, and nididhyasana (see Brhadaranyaka Upanisad 2.4.5) and emphasizes karma for cittasuddhi (see Bhagavad-G?t? 3.20).

- While defining yajña, he fails to use the nirukta (semantic etymology) of the word to describe it, thus giving a fuzzy meaning (p. 98). The word yajña comes from the root yaj-devapujasangatikaranadanesu, which means ‘worship of the divine,’ ‘interaction,’ and ‘sharing’. In general, yajña refers to an act of self-dedication or service above self.

- “…Natya Shastra was a text developed to enable the theatrical performance of itihasas.” (p. 101)

Theatrical performance of the itihsas is one of the uses. Natyashastra has bothprakhyata (well-known, celebrated) and vyutpadya (original, creative) themes. It has themes that are religious as well as secular. It has serious themes and light-hearted ones. This is one of the many instances of Malhotra’s monolithic view of Indian culture and tradition.

- “Traditionally, Hindus have read Sanskrit for the purpose of understanding the ideas of ultimate reality.” (p. 101)

The ultimate reality is beyond form – it is immaterial if Sanskrit is used as a means. Speaking about deep sleep, there is a famous passage that proclaims, “In this state, a father is no longer a father, a mother is no more a mother, the universe is no longer a universe, Vedas are no more the Vedas, a thief is no longer a thief, a sinner is no more a sinner…” (Brhadaranyaka Upanisad 4.3.22)

Further, how does he account for the teachings of many poets and sages who were unaware of Sanskrit – be it the alwars, the vacanakaras, Mahalingaranga, Tukaram, or Ramakrishna Paramahamsa? And are they not a part of our tradition?

In Devendra’s commentary on the Uttaradhyayana Sutra of the Jains, there is a beautiful quote in the second lecture – “When Mahavira spoke, his words were understood by gods and goddesses, men and women, forest-dwellers, and animals.” This is also a traditionalist view!

Of course, we understand and agree in spirit with Malhotra but he should realize that the same tradition that he is defending has these diverse views. We are not anti-Sanskrit but we are also not Sanskrit fanatics. Here, the insightful words of M Hiriyanna prove invaluable – “When a new stage of progress is reached, the old is not discarded but is consciously incorporated in the new. It is the critical conservatism which marks Indian civilization…” (Popular Essays in Indian Philosophy)

- The four ‘levels’ of speech (p. 108)

Malhotra’s explanation is incorrect (and he doesn’t give any references for this too). They are not four ‘levels’ of speech but rather the four ‘stages.’ From conception to utterance, an idea is said to pass through four stages – paraa (before thought),pashyanti (thought), madhyamaa (on the verge of utterance) and vaikhari (utterance). The ancient seers were able to go from paraa to vaikhari instantly (see Vicaraprapañcaof Sediapu Krishna Bhat).

B. Untenable Arguments

- “Meditation mantras…produce effects which ordinary sounds do not.” (p. 21; also see pp. 32, 113

This is at best a theological argument of a mimamsaka. If mantras truly had healing effects, why did our tradition evolve from the daiva-vyapasraya of the Atharva Veda (which believed that certain chants and spells could cure a disease) into the yukti-vyapasraya of Ayurveda (which relies completely on observation; it doesn’t speak about even the healing effects of yogasanas, let alone mantra)? In fact, Vagbhata laughs at people who seek proof for medicines in mantras.

Later on in the book, Malhotra uses terms like “supersensory experiences,” “higher states of consciousness” (p. 107), and “‘rishi’ state of consciousness” (p. 109). He makes arbitrary statements like – “The idea of selfhood that is transcending the ordinary ego is increasingly accepted in scientific inquiry.” (pp. 108-09). All such remarks only weaken his argument since the debate is happening at the level ofpratyaksa and anumana.

- Sanskrit words are non-translatable (pp. 22, 32, 101)

In general, the defining feature of a technical work (pertaining to philosophy, or medicine, or science) is that it can be translated, since it has a precise language of its own (and is not bound to a particular language). On the other hand, poetry is quite hard to translate, but this is true of any language and not just Sanskrit.

Some words become a part of the culture and when we translate such words, we need to provide an explanation but the message can still be passed on in translation. In any case, we find that anything that comes within universal experience can be translated.

Further, even in Sanskrit, the same word has different connotations in different subjects. The word ‘guna’ has a different meaning in Arthasastra, in Yoga, in thekavyasastras, etc. so we need explanations in any case. Just by knowing Sanskrit, one cannot, for instance, read and understand a text on navinanyaya, just like how knowing the English language doesn’t automatically make it possible for one to understand a thesis on Economics.

- Traditional Indian scholars must study Western theories in order to be taken seriously by the West (pp. 44-45)

Malhotra’s pseudo-logic is like the trap of Nyaya that later advaitis fell victim to. See Shankara’s comment on nayyayikas in his commentaries on the Brhadaranyaka Upanisad and the Brahma Sutra. He says that logic can be used on both sides. It doesn’t rely on universal experience. Logic seeks proofs, which are external but spirituality seeks to go inward. Therefore, we have to consider all proofs in the light of universal experience. Nyaya operates at the level of adhibhuta, but Vedanta operates at the level of adhyatma.

The same applies to the Western Orientalists or the Indian Leftists, who are crass materialists. And why should we use Western jargons and systems to study Indian works? We must work out our own way. Doesn’t Malhotra himself admit that the fundamental problem is the viewing of India through a Western lens? An ‘insider’ will use his/her experiential wisdom to silence the complex web of words.

- While providing his reinterpretation of var?a (social classification), Malhotra says, “Manusmriti, 1.87, does give the criteria that the protection of the universe is the purpose of the system.” (p. 165)

This is a dangerous line of argument because many utterances of the Manusm?ti can be used against Malhotra’s reinterpretation. A scholar has the responsibility to perform a critical samanvaya. This will come only upon completely reading the text and transcending it.

- “I agree with Krishna Shastry that Sanskrit must once again become a language of innovation and change, absorbing new words from elsewhere, and inventing new ones internally, as and when the need arises.” (p. 297)

Innovation is not language-specific. Appropriating works (and words) into Sanskrit is not of practical value since the world is becoming a global village. We have to produce knowledge and not just write books. And knowledge production doesn’t rely heavily on language (especially as more and more branches of science are developing their own specific language). It is pointless having mere bauddharthawithout having padartha.

- Malhotra opines that it was unwise of M S University, Baroda to have compiled a critical edition of the R?m?ya?a and preparing an English translation (p. 322)

Even before M S University took up this project, there were translations of the Ramayana in English and other European languages. What was so unwise in the critical edition project?

Futher, the Western Indologists have the intellectual equipment to produce other critical editions as well as translations – will Malhotra not agree that it would be better if traditional Indian scholars undertook such work instead of Westerners?

- Malhotra suggests that we must write new smritis for this era (p. 358) and wants traditional scholars to develop new texts (p. 360)

How is this practical? If someone were to compose a new constitution of India in Sanskrit, would s/he be taken seriously? For example, refer to the sastras and smritis composed by great scholars like Vasishta Ganapati Muni and Pullela Sriramachandrudu – what is the value given to their works by the laity and by the scholars? One can compose a sm?ti but what executive authority does s/he have? What are the kind of new texts can traditional scholars develop in Sanskrit? And what to make of compositions in Sanskrit hailing a tyrant like Lenin (Leninamritam)? Or hailing Indira Gandhi (Indira Jivanam), who was one of the major sponsors of Leftist scholars who have been dead against Sanskrit and Sanskriti?

- Malhotra wants Sanskrit to be bracketed with Arabic, Mandarin, and Persian instead of Greek and Latin (p. 377)

Sanskrit grammar has remained more or less frozen from the time of Panini. However, widely spoken languages like Arabic, Mandarin, and Persian have undergone changes in grammar and structure over the years. It is best to put Sanskrit in a separate category.

C. Ignorance of Existing Literature and Divergent Views

- Malhotra speaks about an “Integral unity of Hindu metaphysics” (pp. 98-102) without caring to look at divergent view from within the tradition. The irony is that those whom Malhotra calls ‘insiders’ themselves have so many divergent views.

- “Kavya is literature that can be merely entertaining, or can also be a means for experiencing transcendence.” (p.98)

What then to make of Abhinavagupta’s view that joy and utility are not different in nature; they operate in the same realm (Dhvanyalokalocana 3.14)?

- “If paramarthika is the realm ‘beyond,’ vyavaharika is the ordinary reality around us.” (p. 99)

Paramarthika is not just beyond but also within. By putting a premium on such a narrow interpretation of paramarthika, there is a danger of leaning towards absolute exclusivity. Also, Malhotra has not given a direct quote of Pollock rejecting theparamarthika.

D. Additional Approaches to Counter Pollock

- Oral tradition vs. Written tradition (p. 106)

Brihatkatha, Tripitakas, Puranas, Janapada (folklore), etc. have all evolved from oral tradition. For that matter, any living culture relies on an oral tradition. Writing plays (or at least played) a vital role in documenting a great act after it is over. A culture that is alive cannot completely rely on writing.

- Pollock says, “dharma is by definition ‘rule-boundedness,’ and notes that the rules themselves are encoded in sastra.” (p. 118)

Dharma is not merely normative but is rather a universal support mechanism that seeks sustainability. In fact, by definition, dharma is that which sustains and supports. Further, the tradition has never laid emphasis on blind adherence to sastra at the cost of common sense. For example, Manu says, “Abandon all acts of artha and kama that are opposed to dharma. So also, abandon those acts of dharma that cause sorrow or trouble people.” (Manusmriti 4.176).

- Malhotra describes how Pollock uses sastra to show a “top-down nature of the flow of all knowledge.” (p. 120)

Clearly, Pollock isn’t aware of the sastra–maryada in the Indian context. Also, how does he account for the several scholars from non-brahmana communities who have written several treatises on various subjects in Sanskrit? Among the kayasthas, thereddis, the kammas, and the nayars, there are many mahapanditas who have written extensively in Sanskrit on a variety of subjects. For example, we have a living tradition of the non-brahmana communities from Kerala (including sudras) who have contributed much to vyakarana, ayurveda, jyautisha, natyasastra and kavyamimamsa – not only by writing authoritative works in chaste Sanskrit but also by practical work in those fields. Similarly the kayasthas of Bengal were masters of several areas of study. (For more details refer to our article The Hindu View of Social Classification).

- Pollock underscores the difference between oral tradition and written tradition (p. 130) but how does he account for the fact that all Vedic commentaries were written down? So also, all the Ved??gas and further texts were written down. There is ample evidence for both oral and written tradition in India. Why look upon one with disdain?

- “…the implication is that Sanskrit was also used by common persons for ordinary purposes.” (p. 158)

Further to what evidence Malhotra provides, one can also look into the sudra-vaishya-varga and visesyanighna-varga of the Amarakosa. Even the kalpasutras and many Sanskrit plays are along these lines.

- While speaking about Buddhist impact on Vedic culture (pp. 158-59), we can show the rich pre-Buddhist tradition of many sastras that are outside of ritual. For example, luminaries like Bharata, Kautilya, Panini, Vatsyayana, and Yaska refer to the earlier masters who have inspired their works.

- When Pollock claims that sastra is oppressive (see p. 175), he misses the point that there is a difference between the understanding of the term sastra as used by the laity and by those with classical learning.

- Malhotra describes how Pollock uses the Ramayana as a project for propagating Vedic social oppression (pp. 179-82)

Several allegations have been hurled on Rama andRamayana by members of the Justice Party, Dravida Kazhagam (DK), Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), etc. These have been able refuted by scholars like Sri Chandrashekharendra Saraswati (Kanchi Paramacharya), V Raghavan, and K S Narayanacharya. One can also refer to the lectures of V S Srinivasa Shastry.

In his writings, H D Sankalia presents some strange arguments aboutRamayana. Rahul Sankrityayan floated many absurd theories in his book Volga se Ganga. Savants like K Krishnamoorthy (in Samskruta Kavya) dismissed such ideas at the primary level itself. Similarly, Muppala Ranganayakamma wrote a three-volume work in Telugu demeaning the Ramayana and has been ably refuted.

In every major regional language of India, there have been a host of scholars who have defended Ramayana and Mahabharata.

- Pollock suggests that the Ramayana provides a two-fold divine/demonic construct (pp. 180-81)

Divinization-demonization can be seen in the Vedas too, but it isn’t surprising. It is but natural to any culture – be it the Egyptians, Mesopotamians, Assyrians, Greeks, etc. All of them make a distinction between the good guys and the bad guys.

It is also not uncommon to for heroes to be sons of gods – be it in the Greek tradition or the Christian tradition.

Pollock remains silent on the various injunctions and prescriptions that were imposed on the king. Kings were expected to maintain high standards in their personal and professional lives. The so-called divine right of kings did not mean that they were above dharma. See A K Coomaraswamy’s Spiritual Authority and Temporal Power in the Indian Theory of Government.

- In the list of important milestones in kavya theory (p. 207), one can also add luminaries like Vishwanatha, Madhusudhana Saraswati, and Jagannatha, who showed that art experience is spiritual in the sense of non-sectarian Vedantism.

When Pollock says that kavya and rasa are purely secular and has no connection with spirituality, we should counter him using the words of Kalidasa – “Sages say that dance is a beautiful visual ritual for the gods. It was developed in different ways by Shiva and Parvati. It is seen in the characters of people with varied dispositions (sattva, rajas, tamas) and is distinguished by many rasas. Dancing is the primary entertainment for humans, though individual tastes may vary.” (Malavikagnimitram, Act 1, Verse 4)

Further Pollock ignores a work that he himself has translated – Bhavabhuti’s Uttarar?macarita, which says that the Ramayana is “a history that represents the first such manifestation among men of the mystery of language.” (Prelude to Act 2; from p. 134 of Rama’s Last Act – Sheldon Pollock’s translation). It is also noteworthy that his translation is unsatisfactory. What the poet is trying to say is really this – “The Ramayana is the temporal appearance of the eternal unmanifest sound (sabda-brahman).”

- Pollock “gives the example of Kalidasa’s composition Raghuvamsha, ‘in itself a notable instance of the aestheticization of the political.’” (p. 215)

Raghuvamsa is studied for the sake of values including the theory of beauty and art. Kalidasa declares at the outset of his epic, “Those who were pure by birth and worked without a greed for reward, those who ruled the earth until the sea, the tracks of their chariots went to heaven.” (Raghuva??a, Canto 1, Verse 5; also refer to verses 6-8)

If Kalidasa was subservient to a political game, why did he give the grim image of an evil king like Agnivarna, who ignored values and met his downfall?

- Pollock claims that the theory of kavya became robust only at the time of Bhoja (p. 217)

This is untrue. Medhavirudra, Dandin, Bhamaha, Vamana, Rudrata, Udbhata, Anandavardhana, et al. were much before Bhoja and their contributions are significant to the kavya theory.

- Pollock claims that kavya was primarily produced in royal courts, in support of royal mandates and its content was complicit with oppression (p. 218)

How does he account for the fact that several poets like Shudraka, Shyamalika, Dandin, Bhallata, Kshemendra, and Kalhana show a great acumen for social and political criticism?

Outside the royal courts, there were the nagaraka goshtis in towns (see Vatsyayana’sKamasutra) and purana goshtis in villages. For example, Kalidasa refers to ‘learned village elders’ in Ujjain who are familiar with Udayana’s tale (Meghaduta, Canto 1, Verse 31). We find a reference to vidya-goshtis in Mankha’s Srikanthacaritam (Canto 25). Rajashekhara, Kshemendra, and Dandin speak about such goshtis (see Ratnasrijnana’s commentary on Dandin for a detailed explanation).

- Pollock tries to show that the Ramayana being recited before Rama shows thatkavya was a product of royal patronage (p. 219)

Ramayana was first sung in the forest hermitages of the seers. Valmiki also speaks about the gifts given by the seers to Lava and Kusha (Rama’s children) but say nothing about Rama’s giving any gifts.

Further, we have several poets who never sought royal patronage, including Tikkana (when he worked on his Mahabharata project), Potana, and Somanatha (in Telugu) as well as Harihara, Raghavanka, Kumaravyasa, Chamarasa, Lakshmisha, and many more (in Kannada). Many Sanskrit poets like Bharavi, Magha, Kalhana, Shilhana, Jalhana, Vallabhadeva, and Vedanta Deshika never mention any of their patrons and one can never be sure if they ever received royal patronage.

- Pollock “claims that spatial differences in Sanskrit literature imply a bias about geographies. Some places are shown as rustic and others as sophisticated. Naive rustic maidens are, he says, differentiated from the cultured, beautiful ladies of a city.” (p. 220)

While this is true to some extent, there is no contempt shown by one group towards another (see Meghaduta for example). Also, the concept of ‘spaces’ can be seen in Sangam Tamil tradition (‘tinai’). Rajashekhara says in his Kavyamimamsa that the couple of kavyapurusa and sahityavadhu moved in every corner of India and adopted respective lifestyles and never sowed any contempt.

- Pollock says that the “kings sponsored brahmins to infuse Sanskrit grammar and rules of kavya into the local languages…” (p. 225)

How does he account for the court poetry produced by Jains and Buddhists in Tamil and Kannada in large numbers? Similarly, many Jain scholars from Gujarat like Hemachandra, Gunachandra, and Ramachandra were under the patronage of the Chalukyas. Ashvagosha, the foremost Buddhist poet, was patronized by Kanishka.

- Pollock tries to connect royal patronage to grammar in order to show that it is a tool for oppression (pp. 234-35)

Panini himself pays tribute to ancient grammarians, whose work guided him. Both Panini and Patanjali often speak about common usage. No serious commentator or critic of Panini has accused him of being partial to royalty. Pollock’s quoting of a random Chinese pilgrim is absolutely ludicrous (p. 435)

- On the basis of his study of prasastis, Pollock suggests that it was the royalty that primarily sponsored works of art and grammar (p. 242-43)

History has shown that a great work of art is something that has appealed to the laity as well as the learned. Pollock forgets that no prasasti kavya was held in high esteem by either the laity or the aestheticians/scholars. Even a cursory glance at the works of ‘asthana-kavis’ and the ‘mahakavis’ will show us that there is no causal connection between royal patronage and the greatness of art.

We can give an example from the history of Indian temples to counter Pollock’s hypothesis that the kings held sway over every aspect of culture. Many of the temples built by kings in places of their choice have been forgotten but those temples constructed in kshetras, which have been hailed by the masses, are popular even today. The Kalyana Chalukyas and Hoysalas built numerous temples but many are forgotten. But the temples in Tirupati, Kashi, Srirangam, etc. are still popular.

- Pollock tries to make a case that the meaning of the word ‘aksara’ is different in Sanskrit and Kannada (p. 249-50)

This is untrue. The word aksara also means ‘alphabet’ in Sanskrit. For example, seeomityekaksaram brahma (Mandukya Upanisad), aksharani parikshyantam (Caatu of Appaya Dikshita), and aksharaani suvruttani (Samayocitapadyamalika).

- Pollock tries to show that there was a divide between Sanskrit and the regional languages and dismisses the idea that bilingual scholars used both languages they knew (p. 251)

A host of scholars and poets like Hemachandra, Krishna Deva Raya, Kshemendra, Madhuravani, Nachana Somana, Nannaya, Pampa, Raghavanka, Rajashekhara, Shadakshari, Srinatha, Tirupati Venkata Kavi, Venkamatya, Vishwanatha, etc. have composed in more than one language (and this continues to this day).

- Malhotra quotes Hanneder’s rebuttal of Pollock, who claims that no new Sanskrit work of great merit has come out (p. 302)

One can refer to the works of Chakrakavi, Chamarajanagar Ramashastry, Ghanashyama, Harijivan Mishra, Kuttikavi, Samarapungava Dikshita, Sitarama Shastry, Venkatadhvari, et al.

- To the list of evidence for Ramayana prior to the Turkish invasion (pp. 392-96) that Malhotra gives, we can also add the works of Kalidasa, Bhasa, and Ashvaghosa, as well as Shudraka’s Mricchakatika, Abhinanda’s Ramacarita, Dinnaga’s Kundamala, and Amoghavarsha’s Kavirajamarga.

E. The Universality of San?tana Dharma (by Dr. G L Krishna)

Three cardinal features confer upon sanatana dharma its universal character. These three, needless to say, are not mutually exclusive; they, in fact, nourish one another.

- The Natural Foundation

na va are devanaam kaamaya devaah priyaa bhavanti

atmanastu kaamaya devaah priyaa bhavanti |

na va are vedaanaam kaamaya vedaah priyaa bhavanti

atmanastu kaamaya vedaah priyaa bhavanti |

(B?had?ra?yaka Upani?ad 4.5.6)

Devas are loved, not for their sake,

but for the sake of the Self

Vedas are loved, not for their sake,

but for the sake of the Self

This Vedic idea, trans-Vedic nevertheless, couched in those immortal love-talks of Yajnavalkya and Maitreyi, constitutes the very foundation of sanatana dharma. The self, which is “the same and yet not the same as the ego,” is here the object of ultimate value. Therefore, the self, and not the world, becomes the determinant of all dharma. It is this feature that accounts for the naturalness of sanatana dharma and makes its adherent amusingly independent of all societal constructs in the exercise of his religious choices. Vivekananda said it point-blank: “No two persons have the same mind or the same body… No two persons have the same religion…” Multiplicity of Hindu deities and myriad forms of their worship is a fierce expression of this primacy of self in the determination of dharma.

This primacy of the self requires and in fact, engenders a striking societal imperative – liberty. Naturalness expresses itself through liberty and liberty nurtures naturalness. All reformations within sanatana dharma have had this idea for their pivot. Vivekananda again: “Liberty… is our natural right to be allowed to use our own body, intelligence, or wealth according to our will, without doing any harm to others… Freedom in all matters, i.e. advance towards Mukti is the worthiest gain of man. To advance towards freedom – physical, mental and spiritual – and help others to do so, is the supreme prize of man. Those social rules which stand in the way of the unfoldment of this freedom are injurious, and steps should be taken to destroy them speedily. Those institutions should be encouraged by which men advance in the path of freedom.”

It may be mentioned in the passing that this principle stands at root of the svakarmaconcept elaborated in the Bhagavad-Gita.

- The Cultural Edifice

yadyat vibhutimatsattvam

srimadurjitameva va? |

tattadevaavagaccha tva?

mama tejomshasambhavam ||

(Bhagavad-Gita 10.41)

All that is endowed with

glory, grace, grandeur,

has sprung from

a mere flare of my radiance

In this masterstroke of a verse, Krishna has universalized the culture of sanatana dharma. The ripe civilizational idea that aesthetic experience is a religious exercise, expressly stated in the verse quoted, has made art and religion the same thing in India. That our Gods and Goddesses, from Rama and Krishna to Hanuman and Draupadi, are characters from our literary classics is a most marvellous phenomenon of the Indian religion. Our temples doubling as auditoria for performing arts is a corollary of this phenomenon. The implications of this, needless to say, are enormous. The metamorphosis of religious instinct into aesthetic sensibility, of the egotistic into the universal, becomes here simply a matter of course.

Two other important aspects may here be briefly noted. The worship of vibh?ti, in addition to art experience, includes two other things: the celebration of natural geography (the great rivers, the great mountains, etc. as centres of pilgrimage) and the worship of sages (from Vyasa-Vishwamitra to Ramana-Ramakrishna). While the former forges a sense of spiritual fellowship alongside promoting reverence for nature, the latter is a perennial renewer of faith in the grandest ideals of this dharma.

- The Scientific Robustness

na dharmajijñasaayaamiva srutyaadaya eva pramaanam brahmajijnaasaayaam

kintu srutyaadayonubhavaadayasca yathaasambhavamiha pramaanam

anubhavaavasaanatvaat bhutavastuvishayatvaat ca brahmajnanasya

– Shankara (Brahma Sutra Bhashya 1.1.2)

Examination of the nature of the Self, though guided by scriptural authority, is quite independent of it. It derives its authority from being experiential as a matter of fact.

“The question is: Is religion to justify itself by the discoveries of reason, through which every other science justifies itself? Are the same methods of investigation that we apply to sciences and knowledge outside, to be applied to science of religion? In my opinion this must be so… If a religion is destroyed by such investigations, it was then all the time useless, unworthy superstition, and the sooner it goes the better. I am thoroughly convinced that its destruction would be the best thing that could happen.” (Vivekananda)

If there is one religion that can survive this rigorous examination, it is sanatana dharma. The avasthaatraya prakriya of Vedanta, contained mainly in the Brhadaranyaka and Chandogya Upanisads, emphasized especially in the karikas of Gaudapada and clarified accessibly in the path-breaking work of Sacchidanandendra Saraswati, is the truest exemplar of scientific robustness in the examination of ultimate reality (brahmajijñasa?). Detailing the methodology is beyond the scope of this essay. Thanks to this Vedantic analysis, sanatana dharma is extricated from the web of beliefs and dogmas, which in spite of their benefits for the commoner are unfulfilling to the intellectually robust. Solace comes from truth and from truth that is accessible.

These three together make sanatana dharma what it is – benign and accommodative, uplifting and joy-giving, strong and perennial.

sukhaarthaah sarvabhutaanaam

matah sarvah pravruttayah |

sukham ca na vinaa dharmaat

tasmaat dharmaparo bhavet ||

– Vagbhata (in Astangahrudayam)

All beings are naturally driven by a quest after happiness

Without righteous conduct

one can’t attain unfailing happiness

Therefore, righteous conduct is obligatory for all

svakarmanaah anushtaanaam

cintanam paramaatmanah |

rasanam ca vibhutiinaam

trayametaddhi satsukham ||

– G L Krishna

Work in consonance with one’s natural proclivity,

meditation upon the Self, and

worship of exalted beauty

![]() m489A

m489A![Images show a figure strangling two tigers with his bare hands.]()

![]()

m489A

m489A

Long before “connectivity” became a buzzword in India’s foreign policy, Verghese had a clear sense of the damage done by the economic vivisection of the subcontinent.

Long before “connectivity” became a buzzword in India’s foreign policy, Verghese had a clear sense of the damage done by the economic vivisection of the subcontinent. PM

PM

The dismissal of the Rawat government now renders tomorrow’s confidence vote infructuous.

The dismissal of the Rawat government now renders tomorrow’s confidence vote infructuous. BJP national general secretary Kailash Vijayvargiya with Senior Editor Liz Mathew at The Indian Express office. (Express Photo: Renuka Puri)

BJP national general secretary Kailash Vijayvargiya with Senior Editor Liz Mathew at The Indian Express office. (Express Photo: Renuka Puri)

Harish Rawat

Harish Rawat

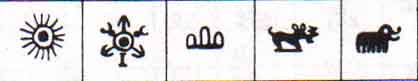

Tinsukia : Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses an election rally at Tinsukia, Assam on Saturday. PTI Photo

Tinsukia : Prime Minister Narendra Modi addresses an election rally at Tinsukia, Assam on Saturday. PTI Photo

Narendra Modi

Narendra Modi

Vikas Swarup

Vikas Swarup

height="380" />

height="380" /> @koenraad_elst

@koenraad_elst

Magadha janapada. Dotted circle connected to three arrows. Ovals between arrows. Elephant. Six dots circling a cntral dot.

Magadha janapada. Dotted circle connected to three arrows. Ovals between arrows. Elephant. Six dots circling a cntral dot.

Magadha janapada. Dotted circle is connected by three allows. Oval hieroglyphs occur between the arrows. Sun hieroglyph is shown on the right top corner, clockwise next to a crucible hieroglyph and a circle with strand hieroglyph.

Magadha janapada. Dotted circle is connected by three allows. Oval hieroglyphs occur between the arrows. Sun hieroglyph is shown on the right top corner, clockwise next to a crucible hieroglyph and a circle with strand hieroglyph. Magadha. Karshapana.

Magadha. Karshapana.

2

2

.jpg)