![]() Shatavadhani Ganesh

Shatavadhani GaneshExploring the World of Varna

Education and economic stability further reduces social disparity. One of the positive outcomes of this is the fading away of social distinctions.

Introduction

Varṇa, the system of classification of society into different groups, has been a topic of much controversy, debate, and deliberation. The numerous studies on varṇa fill up whole bookshelves and deal with humongous details. However, we will explore the subject from a broader perspective, using as references our foundational texts and ancient works of literature.

In general, varṇa is a four-fold classification of society, based on attitude and aptitude. The texts of grammar tell us that the word varṇa comes from the root vṛ-varaṇe, ‘to choose.’ According to semantic etymology, the wordvarṇa comes from vṛṇoteḥ, ‘choosing.’ This suggests that the word initially referred to a self-selection, just like in modern times we choose a career path of our preference.

![anna]() For example, there is a beautiful rite that is part of theannaprāśana ritual (when the baby is fed solid food for the first time; typically six to eight months after birth). The baby is shown a set of objects–a book or a tool or a musical instrument–and the belief is that whatever object the child picks up will indicate the future profession of the child. Though it is symbolic, it shows the inherent prevalence of choice.

For example, there is a beautiful rite that is part of theannaprāśana ritual (when the baby is fed solid food for the first time; typically six to eight months after birth). The baby is shown a set of objects–a book or a tool or a musical instrument–and the belief is that whatever object the child picks up will indicate the future profession of the child. Though it is symbolic, it shows the inherent prevalence of choice.The four varṇas are: brāhmaṇa, kṣatriya, vaiśya, and śūdra. In addition, there are several sub-groups that arose from the inter-mingling of thevarṇas.

A brāhmaṇa is a person with natural aptitude for learning, analyzing, researching, and teaching. A kṣatriya is a person with natural aptitude for protecting others, warfare, governance, politics, administration, and management. A vaiśya is a person with natural aptitude for managing money, trading, farming, and skilled labour. A śūdra is a person with natural aptitude for service and physical work.

Every individual has certain inherent talents and interests. This makes him/her naturally suited to fulfil certain roles in the world. The various activities that people undertake finally contributes to the growth of the community, the society, and the world; hence no one is greater or lower than the other.

In fact, the affirmation is that all members of society have their origin in the Supreme Being (Ṛgveda Saṃhitā 10.90.12). We find a similar sentiment in Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa 2.8.8.9, which says that Brahmā is the progenitor of all people, and of all deities.

Of course, the connotations of varṇa have changed over the years – starting from the early Vedic period (c. 4000 BCE) all the way down to today. It is evident from our texts that varṇa has always been dynamic – it has never been set in stone. We must also remember that the ordinances in our ancient law texts are not necessarily an indication of how society functioned at that period of time; laws also tend to be aspirational (for example, according to article 51A of the Constitution of India, one of the fundamental duties of an Indian citizen is to develop “scientific temper, humanism and the spirit of inquiry and reform”).

The instances that we can draw from our works of literature give us a better understanding of how society worked. And when we juxtapose that understanding with the dictates of the law texts, we will further get a sense of what portions reflect the nature of the society in those times and what portions are theoretical and idealistic in their conception.

Here are some works of literature that give us many insights into ancient India: Vālmīki’s Rāmāyaṇa, Vyāsa’s Mahābhārata, Kālidāsa’s poems and plays, Somadeva’s Kathāsaritasāgara, Kalhaṇa’s Rājataraṅgiṇi, Viṣṇuśarma’s Pañcatantra, Śūdraka’s Mṛcchakaṭika, Viśākhadatta’sMudrārākṣasa, the four plays contained in Caturbhāṇi, the minor works of Kṣemendra (like Narmamālā, Samayamātṛkā, Darpadalana, Deśopadeśa, and Kalāvilāsa), Damodaragupta’s Kuṭṭinīmata, Bodhayana’sBhagavadajjuka, Veṅkaṭādhvari’s Viśvaguṇādarśa, Mahendravarma’sMattavilāsa, Nīlakaṇṭhadīkṣita’s Kaliviḍambana, Simhāsana Dvātriṃsika,Vetāla Pañcaviṃśati, Rājaśekara’s Prabandhakośa, Merutuṅga’sPrabandhacintāmaṇi, Vidyāpati’s Puruṣaparīkṣā, Saṅghadāsagaṇi and Dharmasenagaṇi’s Vasudevahiṇḍī, Hālaśātavāhana’s Gāhāsattasayī, and theJātaka stories.

At any rate, all through this discussion on varṇa, we have to remember one thing – varṇa is not a core aspect of Hinduism. It comes under what is called viśeṣa dharma, a set of rules applicable only with limited jurisprudence and are bound by geographical and temporal constraints. It is contextual, not universal, and therefore is a peripheral aspect of our tradition. Sāmānya dharma, on the other hand, applies to everyone and therefore forms a core aspect of our tradition.

Varṇa in the Vedas

There is no unanimous view on the origin of varṇa – it might have been a distinction based on occupation or based on the tribes that people belonged to. What we do know for sure is that varṇa has nothing to do with race and ethnicity, since recent studies have shown that most Indians are genetically alike (see Elie Dolgin’s article “Indian ancestry revealed” in Nature, September 2009).

In the Ṛgveda Saṃhitā, varṇa is not used in the sense of ‘caste’ or ‘class’ but rather it means ‘colour’ or ‘light’ in many passages (see RVS 1.73.7, 1.104.2, 2.3.5, 2.34.13, 3.34.5, 4.5.13, 9.97.15, 9.71.8, 10.3.3, and 10.124.7).

In some verses, it means ‘form’ or ‘definition’ (see RVS 1.92.10, 1.96.5, 1.113.2, 2.1.12, 2.4.5, 2.5.5, 9.104.4, and 9.105.4). In some other verses (see RVS 1.179.6, 2.12.4, 3.34.9, 9.65.8, and 9.71.2) the word varṇa is associated with groups of people having fair skin (the āryas) or dark skin (the dāsas ordasyus). This might give an impression that the āryas and the dāsas were different tribes or opposing clans but we realize that the ‘colour’ is more metaphorical than literal. We know, for instance, some of the ṛṣis were dark-coloured, like Kṛṣṇa, Kaṇva, and Vyāsa. Further, some of the āryas had the name ‘dāsa’ as part of their name, like King Sudāsa, the son of Divodāsa (see RVS 7.18 for example). The bright-coloured āryas are those people who adhere to dharma while the dark-coloured dāsas are those who don’t – ‘bright’ symbolizing wisdom and ‘dark’ symbolizing ignorance. We see this in the text itself, where dāsas are described as avrata, ‘not obeying the prescribed rules’ (see RVS 1.51.8, 1.175.3, and 6.14.3) and as akratu, ‘those who don’t perform yajña’ (see RVS 7.6.3).

There is a verse (RVS 1.179.6) that has the word varṇau, meaning “twovarṇas” and this is used to imply the two fundamental dispositions – of desire (kāma) and of penance (tapas).

In the Ṛgveda Saṃhitā, varṇa is only used in connection with the two groups – the āryas and the dāsas. Though the words brāhmaṇa and kṣatriyaoccur frequently, the word varṇa is not associated with them. Also, it is unlikely that these two were distinct “castes” at that period of time (unlike the later period, where they were rigidly separated).

In RVS 8.35.16-18, there is a mention of the three groups in society –brahma, ‘those who think and compose songs,’ kṣatra, ‘those who are endowed with valour and protect others,’ and viśa, ‘the common people who tend to cattle.’

Again, it is unlikely that these were inflexible social structures and it is highly improbable that they had anything to do with birth. In RVS 7.33.11, Vaśiṣṭha is referred to as a brāhmaṇa, but we know that he wasn’t born abrāhmaṇa (he was the son of the celestial courtesan Urvaśī).

In RVS 9.112.3, the poet says, “I am a singer of poems, my father is a doctor, and my mother grinds corn. We desire to obtain wealth in various activities.”In another verse (see P V Kane’s History of Dharmaśātra, Vol. 2, Part 2, p. 31) the poet asks Indra, “Will you make me the protector of people, or will you make me a king? Will you make me a sage, who has drunk soma? Or will you impart to me endless wealth?”

RVS 10.98.8 speaks about two brothers, Devāpi and Śantanu. While the younger brother Śantanu takes over the kingdom, Devāpi becomes abrāhmaṇa (we also find this story in the Śalyaparva of the Mahābhārata).

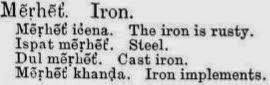

We find the names of various professions in the Ṛgveda Saṃhitā which later went on to become castes – for example, vaptā, ‘barber’ (RVS 10.142.4); tvaṣṭā, ‘carpenter’ (RVS 8.102.8); bhiṣak, ‘physician’ (RVS 9.112.1); karmāra, ‘ironsmith’ (RVS 10.72.2); and carmamnā, ‘tanner’ (RV 8.5.38).

Chapter 30 of the Vājasaneyi Saṃhitā (of the Śukla Yajurveda) has a list of several professions and these later became “castes.” It is highly plausible that the professional groups of the Saṃhitā period evolved into social groups and castes in the Brāhmaṇa period.

The only instance where the four “castes” are mentioned in the Ṛgveda Saṃhitā is in the Puruṣa sūkta (RVS 10.90.12), which we know to be from a later period. (Of the ten books of the Ṛgveda Saṃhitā, books 1 and 10 are chronologically last). Further, in this verse, we don’t find the word varṇa.

Varṇa in the Later Vedic Period

We observe that even in the period of the Vedas, during the later part of the Saṃhitā texts and with the advent of the Brāhmaṇa texts, the society became more structured. The distinctions of social class became more prominent.

The word dāsa in later works came to mean ‘servant.’ We can surmise that the dāsas who were overpowered by the āryas, over time were made into servants. Manu’s statement that śūdras were created by the Supreme for the service of the brāhmaṇas (Manusmṛti 8.413) gives us the idea that thedāsas eventually became the śūdras, who had a low position in society.

This can be further illustrated by many instances from the later texts. For example, Aitareya Brāhmaṇa 7.29.4 says, “the śūdra is at the beck and call of the other three varṇa; he can be made to rise at will, he can be beaten at will.” We may also draw from the darśana texts – Jaimini in his Pūrvamīmāṃsa Sūtra 6.1.25-28 says that a śūdra doesn’t have the right to perform Vedicyajñas and Bādarāyaṇa in his Vedānta Sūtra 1.3.34-38 says that a śūdradoesn’t have the right to study the Vedas. A notable exception is Ācārya Bādarī who mentions that everyone, including śūdras, had the right to perform Vedic yajñas (see Jaimini’s Pūrvamīmāṃsa Sūtra 6.1.27).

In spite of the lowly status given to śūdras in the later texts, it is interesting to note that they were still considered an important component of the society. For example, Taittirīya Saṃhitā 5.7.6.3-4 says, “…put glory in our brāhmaṇas, put glory in our kṣatriyas, put glory in ourvaiśyas and śūdras.”

Vājasaneyi Saṃhitā 26.2 shares a similar sentiment when it says, “The words of the Vedas are for the welfare of all people – the brāhmaṇas, the kṣatriya, the vaiśyas, the śūdras, relatives and strangers, the women, and the servants, wanderers/forest-dwellers, and all others. The Gods love those who share wisdom with everyone. Both who gives and receives knowledge is blessed.” (yathemāṃ vācaṃ kalyāṇīmāvadāni janebhyaḥ|brahmarājanyābhyāṃ śūdrāya cāryāya ca svāya cāraṇāya | priyo devānāṃ dakṣiṇāyai dāturiha bhūyāsamayaṃ me kāmaḥ samṛdhyatāmupamādo namatu ||)

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 1.4.11-15 mentions that each varṇa is great in its own way. It also divides the gods into four varṇas – Agni is a brāhmaṇadeity, Indra is a kṣatriya deity, Viśvedevas are vaiśya deities, and Pūṣaṇ is aśūdra deity. This again reinforces the conception that varṇa refers more to trait than hierarchy, because among the deities, none is greater or lower (as suggested by Ṛgveda Saṃhitā 5.60.5).

Although the social classification had started becoming inflexible by the later Vedic period (c. 1500 BCE), we find that those who were really talented attained recognition and came to the forefront, irrespective of their varṇa.

Aitareya Brāhmaṇa 2.19.1 tells the story of the seer Kavaṣa Ailūṣa, who was humiliated by some brāhmaṇas during a yajña with the words, “O son of a śūdra mother, you are a rogue and not a brāhmaṇa! How did you become one of us?” They carried him to a desert and left him there to die. Tormented by thirst, he had a vision of a poem (Ṛgveda Saṃhitā 10.30) and the river Sarasvatī gushed towards him.

The great sage Mahīdāsa Aitareya was a pāraśava (a lower caste; an offspring born to a śūdra woman from a brāhmaṇa man). He was the son of Itarā, a śūdra woman who was married to a sage. He is the seer of the Aitareya Brāhmaṇa, Aitareya Āraṇyaka, and Aitareya Upaniṣad.

Similarly, Kakṣivān, one of the seers of the first book of the Ṛgveda Saṃhitā was the son of sage Dīrghatamas and a servant maid. Chāndogya Upaniṣad 4.4 tells the story of Satyakāma Jābāla, the illegitimate child of aśūdra woman, who goes on to become a great sage.

Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 2.1 tells the story of a brāhmaṇa, Bālāki Gārgya, who learns the highest truth from a kṣatriya, Ajātaśatru, the king of Kāśi. We see similar instances in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 11.6.2.5 (King Janaka of Videha instructs sage Yājñavalkya), Chāndogya Upaniṣad 5.3 (Pravāhana Jaivali, the king of the Pāñcālas instructs Śvetaketu), and Chāndogya Upaniṣad 5.11-18 (Aśvapati Kaikeya instructs Āruṇi Uddālaka and others).

These incidents are significant because in the normal course, it was thebrāhmaṇa who was the teacher of the highest truths.

There are several instances in the Vedas as well as the smṛti texts that tell that brāhmaṇas were given an exalted position (see for example, Taittirīya Saṃhitā 2.6.2.5, 5.2.7.1) and had many privileges (see for example, Manusmṛti 8.24, 8.37, 8.87). However, the brāhmaṇas also had numerous rules and regulations to follow. They were expected to lead ascetic lives and focus more on spiritual pursuits (see for example, Manusmṛti 8.2, 8.3, 8.7, 8.11). Furthermore they never claimed to be above truth and justice in a court of law.

In the Atharvaveda, many verses declare that great harm befalls people and kingdoms when a brāhmaṇa is disrespected or injured or whose cow is robbed (see for example, AVS 5.18.4, 5.18.13, 5.19.3, and 5.19.8).

The stories from the Purāṇas suggest that these decrees arose possibly because of the widespread disrespect of brāhmaṇas by the rulers, who in some cases stole the cows of respected brāhmaṇas (like Kārtavīryārjuna stealing the cow of Jamadagni – Mahābhārata, Śānti Parva / Book 12, 49).

At some point, even the wives of brāhmaṇas were not safe from the kings. A striking instance of this is the story of the descendents of Bhṛgu from the Purāṇas. When the Bhārgavas living in Bhṛgukaccha (modern-day Bharuch, Gujarat) fell out of favour with kṣatriya kings from the haihaya kula (rulers of the Narmada province in Western India), they were chased down, persecuted, and killed. Even women and children were not spared. One of the women being chased was pregnant with a child and she concealed the baby in her thigh to save his life. The son born to her was the renowned sage Aurva (named so because he was born from the ūrū, ‘thigh’).

Varṇa in the Purāṇas and the Smṛtis

The origin of varṇa according to the Purāṇas (Viṣṇu Purāṇa 4.8) is from the sage Śaunaka who first brought forth the four varṇas. Sage Bharga is said to have accorded the various tasks to the varṇas.

The Bhāgavata Purāṇa 9.15.48 says that in earlier times there was only onevarṇa from which all other varṇas came about. We find a similar idea in the Rāmāyaṇa (Uttarakāṇḍa 3.19-20). However, Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad 1.4 tells us in unequivocal terms that brahman (the supreme being) did not flourish until it created all the four varṇas as well as the idea of dharma.

For a society to flourish, we need different kinds of people with varied abilities, temperaments, and skills. Just like the human body has different vital organs performing totally different tasks to maintain health and well-being, we need different kinds of people in society executing different functions to maintain harmony. Just as no vital organ is greater than the other, no social group is greater than the other. They have to work in coordination for a smooth functioning of the system.

Further, the four varṇas may be realized within a single individual during one’s lifetime. For example, in the life of Kṛṣṇa, who is the very embodiment of sanātana dharma, we find him fulfilling the roles of different varṇas. He is a brāhmaṇa, engaging in intellectual pursuit and meditation – he imparts the wisdom of the Gītā, an exposition of the highest truths. He is a kṣatriya, who engages in battle, rules his kingdom, and is renowned for his political acumen. He also kills wicked people like Kamsa, Cāṇūra, Madhu, and Kaiṭhaba. He is a vaiśya, engaging in farming, trade, and tending cattle as he grows up among cowherds in Gokula. He is aśūdra, driving Arjuna’s chariot in the great war.

That said, all our traditional law-givers have structured their law texts in the framework of the varṇas, so even if we are unsure about the relationships and power equations between the different classes, we are quite certain that they existed, there was a hierarchy of classes, and gradually it became rigid and based on birth.

There is a lot of divergence in the various smṛtis (we have about fortysmṛtis) about the same or similar issues. This should not come as a surprise because many of the lawgivers were born in different time periods and in different kingdoms. In spite of all the differences in opinions, they all seem to have adhered to the fundamental principles of dharma while composing these texts.

There are five basic features of varṇa as laid out in the law texts:

- A person belongs to a certain varṇa since he is born to parents of that varṇa

- A person can marry only with the same varṇa but can’t marry specific relatives

- Food, drink, clothing, etc. of a person should be in line with his/her varṇa

- A person belonging to a certain varṇa is allowed to carry out specific occupations and no other

- The different varṇas have a hierarchy in society

For each of these features, there are several rules and exceptions. For example, in case the parents of the child are from different varṇas, there are rules about how the varṇa of the child would be determined.

There is also considerable debate about whether a person belongs to a certain varṇa merely by accident of birth or should his traits and occupation account for something. In the Śāntiparva and Anuśāsanaparva of the Mahābhārata, we find many verses that suggest that brāhmaṇas must be respected simply because of their birth (also see Manusmṛti 5.317) but we find some crucial verses that indicate that a brāhmaṇa is known by his conduct and skill and not by his birth (see for example, Vanaparva / Book 3, 181.42-43 or Udyoga Parva / Book 5, 43.49). In Bhaviṣya Purāṇa 40.25 and 41.3, Śukranīti 1.38, and Bṛhadgautamasmṛti 29.10 we find the same idea – traits dominate birth.

Even the redoubtable Manu concedes at one point (Manusmṛti 12.106) that only the person who explores the words of the wise and the dharmaśātras using his power of reasoning without losing track of the fundamental principles of the Vedas can truly know dharma (also see Nirukta 13.12).

Further, there is the idea that varṇa is not static across births. Depending on the actions one undertakes in this birth, his/her varṇa might change in the next birth. Āpastamba Dharmasūtra 2.5.11.10-11 speaks about this change of varṇa. It says that if people fulfil their dharma, in their next birth, they are born in a higher varṇa but if they abandon their dharma, in their next birth they are born in a lower varṇa.

![gita]() A text no less than the Bhagavad-Gītā says that varṇa is a distinction based on guṇa, ‘trait’ and karma, ‘work’ (BG 4.13) and not on other factors. The natural temperament of the individual, coupled with the nature of his work determines his varṇa. This is by far the broadest and most sensible definition of varṇa in our tradition.

A text no less than the Bhagavad-Gītā says that varṇa is a distinction based on guṇa, ‘trait’ and karma, ‘work’ (BG 4.13) and not on other factors. The natural temperament of the individual, coupled with the nature of his work determines his varṇa. This is by far the broadest and most sensible definition of varṇa in our tradition.It is important to note here that some of the latter-day commentators of the Gītā have narrowly presented the idea of varṇa in their commentaries because of their bias. If we look at the text itself, there is no reason to believe that varṇa is based on anything but guṇa and karma (for example, BG 3.27 says that all actions are driven by guṇa and BG 3.5 says that nobody is exempt from karma).

We can deduce that as society grew more complicated, birth became an easy cut-off point to determine varṇa. But in spite of this, we find illustrative examples of people who rose in the ranks because of their great deeds (e.g. Vidura from the Mahābhārata) or fell in the ranks by committing a grave sin (e.g. Rāvaṇa from the Rāmāyaṇa).

In the Anuśāsana Parva of the Mahābhārata, we find the story of the great sage Mataṅga. At one point of time in his life, Mataṅga realizes that he is actually not a brāhmaṇa; he was born when his mother had an affair with a barber. The moment he comes to know of this, he goes away to the forest, performs severe penance and then becomes a brāhmaṇa by virtue of his learning and meditation.

Then there is the story of the kṣatriya Vītahavya, who becomes a brāhmaṇaby chance. His son, Gṛtsamada is one of the seers of the Ṛgveda. Similarly, Rathītara was a kṣatriya by birth but he became a brāhmaṇa by his learning. In the lineage of the famous kṣatriya Rantideva, we find Gārgya, a famous brāhmaṇa.

Similarly, with respect to marriage, though it was preferred that one marries within the same varṇa, there were several marriages and clandestine affairs that violated this. It was ordained that if at all one had to marry outside of one’s varṇa, a man from a higher varṇa could marry a woman from a lower varṇa (called anuloma marriage) but not the other way round. And in case it was the other way round (pratiloma marriage) or during instances of illegitimate affairs, they speak of the repercussions – in some cases it is punishment and in others, it is lowering of social status or banishment.

When we see the staggering number of rules, duties, and privileges of the various sub-groups – offspring of brāhmaṇa father and vaiśya mother,śūdra father and kṣatriya mother, kṣatriya father and brāhmaṇa mother, etc. – we realize that though marriage outside varṇa was frowned upon, it was rather common.

In the Mahābhārata (Vanaparva / Book 3, 180.31-33), Yudhiṣṭira tells King Nahuṣa that distinctions based on varṇa no longer make sense since there has already been so much of mixing up of varṇas.

Evolution of varṇa

Before we discuss the evolution of varṇa from the classical period (6thcentury BCE) onwards, it might be worthwhile to introduce the term jāti, or ‘category.’

While varṇa seems to have come from occupation, culture, and aptitude,jāti seems to emphasize on birth, family reputation, (family) profession, and economic status. Varṇa takes into account the worth of the individual and constructs a social system for the division of labour.

Further, varṇa emphasizes the prescribed duties for the community. Jāti, on the other hand, takes into account the history of the family and cares little for the prescribed duties. It is more concerned with rights and privileges. It is noteworthy that the term jāti in the sense of social classification hardly ever occurs in the Vedas. Interestingly, the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa uses the word jāti to denote ‘species.’

Swami Maheshwaranandagiri’s research based on the sthaḻa-purāṇas (local stories) and folk traditions indicates that there has been a great deal of mixing up of varṇas as well as inclusion of foreigners and forest-dwellers into the mainstream society.

The nambūdiri brāhmaṇas of Kerala are said to have come from kṣatriyas who fell from their standing due to an act of imprudence; so also thenāgamācī brāhmaṇas. The tuḻu brāhmaṇas of Karnataka were originally from the fishing community and Paraśurāma is said to have converted them, using the wires from the fishing nets as the upavīta (sacred thread).

During the reign of Kadamba Mayūra Varma, several people were converted into the brāhmaṇa varṇa for the sake of performing yajña (the Vedic fire ritual). The citpāvana brāhmaṇas of Maharashtra are said to have come from Iran. The ābhīra gujjara brāhmaṇas of Punjab are said to have come from Eurasia. Also, some of the prominent kṣatriya groups in Punjab were originally brāhmaṇas.

The brāhmaṇas of Gorakhpur like the pāṇḍes, śuklas, and miśras were originally bañjāras (wandering gypsies). Similarly the pāṭhaks and ojhas were originally not brāhmaṇas. The gaṇaka brāhmaṇas of Assam are said to have come from Mongolia. The bhodri brāhmaṇas were originally barbers.

Kings like Jayacandra and Śivasiṃha (of Mithila) made thousands of forest dwellers and tribals into brāhmaṇas. They are the kanojiyā and sarayū pārīṇa brāhmaṇas. King Śālivāhana is also said to have done mass conversions into the brāhmaṇa fold. Also, the Bhaviṣya Purāṇa speaks of how sages like Śaunaka and Kaṇva went to foreign lands and brought many people into the Hindu fold.

We observe that even the surnames of the different varṇas changed over time. Manusmṛti 2.32 says that a brāhmaṇa’s surname should connote happiness (hence came Śarma), a kṣatriya’s surname should imply protection (hence Varma), a vaiśya’s name should imply nourishment (hence Gupta), and a śūdra’s name should connote service (hence Dāsa). But we know of brāhmaṇas with vaiśya surnames, like Viṣṇugupta (Kauṭilya), Abhinavagupta, and Parimalagupta. Kālidāsa, a brāhmaṇa and Kumāradāsa, a kṣatriya had śūdra surnames.

Even with regard to occupation, we find some instances where people had given up occupations that were specific to them and moved on to jobs that were more lucrative. Many of the smṛtis specify the kinds of professions people of different varṇas (and sub-groups) are supposed to take up but also mention that during times of emergency (as an āpaddharma), a change of roles and professions was allowed.

If we look at the economy of those times, we know that production was localized (not centralized) and in small quantities (not mass produced). Transportation of produce was limited and took quite a while. There was little or no chance for people to rush to a certain profession because it was lucrative.

Today, quite a few boys and girls choose their line of study in accordance with the “scope” of the field. If in one generation, there is a mad rush to be lawyers, another generation sees a mad rush to be engineers. This wasn’t the case in those days; also, the overall choices were limited.

Patañjali says in his Mahābhāṣya (on Pāṇinī’s Aṣṭādhyāyī 2.2.6) –“Contemplation, study of Vedas, and birth in a brāhmaṇa family are the three factors for someone to be a true brāhmaṇa; one who is devoid of contemplation and study of Vedas is a brāhmaṇa by birth alone (and not a true brāhmaṇa).” He also says, “Words like brāhmaṇa, kṣatriya, vaiśya, and śūdra are indicative of guṇa.” Again (in his commentary on Aṣṭādhyāyī 4.1.104), Patañjali says that a person becomes a seer only after deep penance and not by birth.

In spite of this, brāhmaṇas retained their social status. We see this in Śūdraka’s play Mṛcchakaṭika, where the hero Cārudatta is a brāhmaṇa by birth but a businessman by profession.

Also, in our Purāṇas it is said (Viṣṇupurāṇa 4.24.20-21, Matsyapurāṇa 171.17-18) that after the Nanda kings of Magadha (5th century BCE), nokṣatriya king ruled India – we mostly had śūdra kings, sometimes vaiśyakings, and rarely brāhmaṇa kings.

The Mauryas, the Chalukyas, the Rashtrakutas, the Vijayanagara kings, the Cholas, the Pandyas, the Yadavas (also known as Sevunas), the Kakatiyas, the Chandelas, the Paramaras, the Rajputs, the Pratiharas, the Palas, the Senas, the Chauhans, the Rathods, and the Tomars are some of the śūdrakings. The Guptas were vaiśya kings. The Shungas, the Kadambas, and the Pallavas were brāhmaṇa kings.

Another point to consider here is that even among the brāhmaṇas, there seems to have been a constant evaluation as to which group is greater than the other. One group typically looked down upon another. Even today, in temples, only a particular group of brāhmaṇas are allowed to conduct the worship – for example, the rāval (head priest) of the Badrīnārāyaṇa Temple in Badrinath can only be a nambūdiri brāhmaṇa from Kerala.

So much so, a brāhmaṇa from another group is not even allowed to enter the sanctum-sanctorum. It is little surprise then that brāhmaṇas looked down upon other varṇas. In fact, we see this kind of one-upmanship even among sannyāsis (ascetics) and maṭhādhipatis (pontiffs). This trait seems to be at the core of the human psyche!

There are instances of Hindus who could not tolerate the social discrimination and therefore preferred to convert to Christianity or Islam. We know from history that people with surnames like Bohara, Luhana, Khoja, Bhatia, etc. were Hindus who converted to Islam. There is a story about a group of brāhmaṇas who drank water from a polluted well and were looked down upon by other brāhmaṇas; they got angry and converted to Islam. They are the Bohra Muslims of today.

At this point, it is important to note that many Hindus were forcibly converted to Islam and they needed to have the option to return to Hinduism. This notion is contested by a few orthodox scholars but there is ample evidence in the scriptures to show that such reconversion was not only prevalent (from other faiths, such as Jainism and Buddhism) but also in the spirit of Hinduism.

For example, Ṛgveda Saṃhitā 9.63.5 prays for auspiciousness to all, without any distinctions. When speaking of the maruts, Ṛgveda Saṃhitā 5.59.6 and 5.60.5 declare that no one is elder, no one is younger, no one has a middle position; everyone excels in glory; everyone is honourable in birth; they all grow together, nourishing each other.

This is pretty much the spirit of the utterances in the Ṛgveda. Similarly the Atharvaveda Śaunaka Saṃhitā 3.30.5 exhorts people not to discriminate on physical traits but instead to deal with everyone in a friendly and compassionate manner.

Reformation of varṇa

Over time, varṇa became more and more inflexible. Perhaps from the end of the classical period (c. 8th century CE), for several centuries, the establishment of varṇa remained rather inflexible.

Recent genetic studies show that for the past 1,900 years there has not been much admixture of varṇas in India. However, scholars suggest thatvarṇa became particularly rigid with the increase in the onslaught from foreign invaders, starting from Alexander (4th century BCE) to the Islamic invasions (c. 7th century CE to c. 14th century CE) and finally the domination of the European imperial powers (c. 15th century CE to c. 19thcentury CE).

In the post-classical period of Indian history (c. 8th century CE to c. 18thcentury CE), we find a marked change from the classical period (c. 6thcentury BCE to c. 8th century CE). Rules and regulations became stricter.

For example, in the classical era, Dhruvadevi, the widow of King Ramagupta married his brother, King Chandragupta Vikramaditya (4thcentury CE). In the post-classical period, widow remarriage was not common. Not only in society, but even in matters of rituals and art forms, there was an increasing rigidity in rules.

The openness and magnanimity of the classical period were stifled. There was a shift from elegance and sublimity to sophistication and superficiality. Even in the interpretations of texts, what was easy and natural became strained and efforted in the post-classical period.

After all, only a society that is politically, economically, and culturally free can be open to reforms. With the onslaught of foreign invaders, there was a rise in insecurity, giving way to a form of intellectual ghettoism which was largely absent in the classical era.

It is unlikely that the system of varṇa was brutally enforced by the members of those who were higher in the social hierarchy. If such was the case, there would have been a revolt from the śūdras, who formed a majority of the population. Some form of civil war would have broken out. The classical and post-classical period of Indian history have no such record of revolts that arose because of discrimination based on varṇa. We find the earliest of such revolts only in the modern era (c. 19th century CE).

Starting from the later part of the classical period, all the way to the 21stcentury, our tradition has had a string of sages, social reformers, and internal critics who took drastic measures to rid the society of decadence and outdated ideas.

Śankara says sarveṣām adhikāro vidyāyām, ‘everyone has the right to knowledge’ (Taittirīya Upaniṣad Bhāṣya 1.11) and varṇa or birth is not a barrier for knowledge (also see Śankara’s Bṛhadāraṇyaka Upaniṣad Bhāṣya 4.4.23 and Brahmasūtra Bhāṣya 1.3.37 for similar ideas). Śankara is also known to have given mantropadeśa – pañcākṣara mantras (on Śiva),aṣṭākṣara mantras (on Viṣṇu), and ṣoḍaśākṣara mantras (on Śakti) – to people from various social backgrounds.

![ramanuj]() Rāmānuja is well-known for his social reforms and bringing many people from lower jātis into the śrīvaiṣṇava fold. There is a famous story of him sharing the secretaṣṭākṣara mantra – om namo nārāyaṇaya – with everyone, by shouting it aloud from the temple top in Thirukoshtiyur.

Rāmānuja is well-known for his social reforms and bringing many people from lower jātis into the śrīvaiṣṇava fold. There is a famous story of him sharing the secretaṣṭākṣara mantra – om namo nārāyaṇaya – with everyone, by shouting it aloud from the temple top in Thirukoshtiyur.Madhva gave haridāsa dīkṣa to one and all. Basavaṇṇa’s conception of the vīraśaivasect was aimed at a society free from distinctions based on varṇa. Similarly, thevaiṣṇava movement in Bengal took into its fold people from all walks of life.

There are instances of even foreigners (who were traditionally seen as outside of the establishment of varṇa, since they were not from āryavarta) being welcomed within the social structure and given status among the Hindus.

In the śrīvaiṣṇava tradition, the twelve āzhvār saints are revered. The compilation of the poems of these twelve saints forms the nālāyira divya prabandham (four thousand divine compositions). Among the āzhvārs, we find people from all varṇas. Tiruppāṇāzhvār was an untouchable. Kulaśekhāzhvār was a king. Āṇḍaḻ was a woman saint; her composition, thetiruppāvai, is one of the most important poems among the collection of four thousand. And Madhurakaviyāzhvār, a brāhmaṇa wrote poems only in praise of Nammāzhvār, who was a śūdra.

In the śaiva tradition, the sixty-threenāyaṅmārs (or nāyanārs) are revered. The compilation of the poems of these sixty-three saints forms the twelve volumes of the tirumuṛai. Among the nāyaṅmārs, not only do we find people from all varṇas but also converts from other faiths.

Tirunāvukkarasar (or Appar) was born a Hindu but was drawn to the Jain faith. He lived in a Jain monastery and studied the faith. Later, when he fell ill, he prayed to lord Śiva to cure him. After he was cured, he became a śaiva.

Kāraikkāl Ammaiyār was a woman saint. Kaṇappa Nāyanār was a tribal hunter. Maṅgaiyarkkaraciyār was a queen. Pugazhcozha Nāyanār was a king. Cakkiya Nāyanār was born in the agricultural veḻāḻar community, then converted to Buddhism, and re-converted to Hinduism.

One of the great luminaries of the vārkarī tradition, Jñāneśvara, was born to an outcaste. The nātha and siddha traditions promoted vedānta by transcending the boundaries of varṇa and jāti.In fact, across the bhaktimovements in the post-classical period, there was a call to remove distinctions based on varṇa and jāti. We see this in the teachings of Ramananda, Kabir, Shankar Dev, Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, Meerabai, Ravidas, and others.

An important detail that must be recorded here is that through the post-classical period, almost all our social reformers were also spiritualists, with a strong connection to the spirit of the Vedas – be it a scholar like Śaṅkara, an iconoclast like Basavaṇṇa, or an unschooled weaver like Kabir.

At this point, it might be interesting to briefly examine the advantages and disadvantages of the establishment of varṇa. The positive aspects of varṇaare the following – there was absolutely no question of job insecurity; there was no hindrance to pursue excellence in one’s field; since different people performed different roles in society, there was no chance of cut-throat competition; due to inter-dependency of members of the society, there arose a natural empathy and connectedness; and there was genuine appreciation of diversity in society.

The negative aspects of varṇa are the following – with utter job security, the chances of striving for excellence are low; if a person doesn’t like his/her profession, it was extremely hard to find an alternative; one has to move out of his village or community if he wanted to do something different; and to be able to even make headway in another profession, one had to have extraordinary potential (unlike today, where such jumps in profession are possible thanks to development in science).

Fortunately, our dharmaśāstra texts were constantly evolving over the years with several iterations and changes that were aligned to changing times. We had internal corrections. Commentators on law texts added more layers and offered possibilities for reformation, thus making the law relevant, inclusive, and pertinent for a given place and time.

Varṇa and Education

One of the major disabilities imposed upon the śūdras (and women from allvarṇas) by the lawgivers was that they could not study the Vedas or perform Vedic yajñas. Looking at this with the eyepiece of modern values, we find it unfair and discriminating (in fact, today such a thing is almost impossible with regard to knowledge – everyone has access to all kinds of information).

However, for a moment, consider the difficulty of learning and propagation of knowledge in those ancient times. The study of the Vedas was a serious discipline and perhaps they wanted to keep away those who were not serious. Information was not easily available. Writing was rare and writing materials were procured with great difficulty.

And as for the words of the Veda, utmost fidelity was required. The teacher would recite and the student would repeat. The Vedas were never read, only recited and remembered. The pattern of intonation (or accents) is extremely intricate (there are ten distinct methods of recitation – pada-pāṭha, krama-pāṭha, jaṭā-pāṭha, ghana-pāṭha, rekhā-pāṭha, dhvaja-pāṭha,daṇḍa-pāṭha, ratha-pāṭha, mālā-pāṭha, and śikhā-pāṭha) and a small change in recitation would change the meaning itself.

Given this kind of rigour involved, the brāhmaṇas were not only wary of who they taught it to but also of who overheard the recitation. While it was only the brāhmaṇas who taught the Vedas, Vedic education was available to kṣatriyas and vaiśyas as well.

Further, the quintessence of the Vedic wisdom could be found in the Purāṇas, Rāmāyaṇa, and Mahābhārata. Also, the great kāvyas (poems),kathas (stories), and nāṭakas (plays) are a storehouse of Vedic (spiritual) and non-Vedic (worldly) wisdom; and these were accessible to all.

In fact, the story goes that the eighteen Mahāpurāṇas were first narrated by a sūta (a lower caste; an offspring born to a brāhmaṇa woman from akṣatriya man) in Naimiṣāraṇya with all the great sages in audience.

Another example can be seen in the practice of the sixteen saṃskāras (religious sacraments). Many of the saṃskāras apply to people from allvarṇas – the only difference being that for the śūdras, the mantras used were taken from the Purāṇas and the Āgamas, while for the others, Veda mantras were used.

If the aim of the society was to keep away the śūdras, why did they go through the exercise of having equivalent verses from the Purāṇas for their saṃskāras? Even the highly venerated Gāyatrī mantra had apaurāṇika version (yo devaḥ savitāsmākaṃ dhiyo dharmādi gocharaḥ |prerayet tasya yadbhargaḥ tat vareṇyam upāsmahe ||) so that the people who did not have access to the Vedic Gāyatrī mantra could at least benefit from the wisdom.

The Vedas were kept away not only from śūdras and women but also frombrāhmaṇas who had deviated from the righteous path (they were dubbed asbrahmabandhus, ‘merely related to brāhmaṇas,’ a derogatory term to refer to the patitas, ‘those who have fallen from grace’). In fact, the growth of the Purāṇas and Āgamas seem to have been especially for the sake ofśūdras, women, and fallen brāhmaṇas.

Further, it is important to note that everyone was eligible to learn reading and writing. The knowledge of Sanskrit was available to all.So also were works of literature and all the secular śāstras.

We have many great poets who were śūdras, women, prostitutes, etc. – for example, the poet Bhartṛmeṇṭha was a mahout, Dhāvaka was a washerman, while poetesses Tirumalāmba and Madhuravāṇi were courtesans.

Many mahāpaṇḍitas (great scholars) are not brāhmaṇas – the kāyasthas, the reḍḍis, the kammas, the nāyars, and even Jains and Buddhists – and have written extensively in Sanskrit on a variety of subjects apart from literary compositions.

For example, we have a living tradition of the non-brāhmaṇa communities from Kerala (including śūdras) who have contributed much to vyākaraṇa(grammar), āyurveda (health and well-being), jyautiṣa (astrology),nāṭyaśāstra (dance, drama, and music) and kāvyamīmāmsā (poetics) – not only by writing authoritative works in chaste Sanskrit but also by practical work in those fields.

![images]() Similarly the kāyasthas of Bengal were masters of several areas of study although they did not traditionally have access to Vedic learning. Uriliṅga Peddi, a lower caste poet from the vīraśaiva community extensively quotes Vedas and Upaniṣads in his vacanas (free verse). Nārāyaṇa Guru, a great saint from the ezhava community, composed many works in Sanskrit.

Similarly the kāyasthas of Bengal were masters of several areas of study although they did not traditionally have access to Vedic learning. Uriliṅga Peddi, a lower caste poet from the vīraśaiva community extensively quotes Vedas and Upaniṣads in his vacanas (free verse). Nārāyaṇa Guru, a great saint from the ezhava community, composed many works in Sanskrit.We also know from Kauṭilya’s writings that in the Mauryan era, even courtesans and servant maids were well-educated. Also, we know that many brāhmaṇas who were well-versed in the Vedas were either illiterate or semi-literate (for example, in Act 1 of Viśākhadatta’s Mudrārākṣasa, Kauṭilya gets a kāyastha to write the letter because he feels that abrāhmaṇa’s handwriting is always illegible).

When we look at all these examples, we begin to question the meaning of the word ‘education’ in the ancient context. What we consider today as a hallmark of good education was different in those days.

Also, we know that in certain instances merely having access to knowledge is not sufficient and a specific protocol has to be followed. Today, anyone can gain access to information about medicine or law and become extremely well-versed in either field. However, to practice medicine or law requires us to follow a certain protocol. Similarly, in the study of the Vedas, while birth was a cut-off point, there was no escaping protocol.

Untouchability

In the Vedas, we don’t find any reference to untouchability. Some groups of people who were later labelled antyajas (‘last born,’ ‘untouchables,’ ‘lower birth’) appear in the Vedas, like tanners, barbers, washerwomen, etc. but there is no mention of untouchability.

There is one verse in the whole of the Vedic canon that might be taken to be a reference to untouchability – Chāndogya Upaniṣad 5.10.7 which says that those people whose conduct has been good on earth will attain a higher birth, like that of a brāhmaṇa, kṣatriya, or a vaiśya, but those whose conduct has been evil will attain a lower birth like that of a dog, a boar, or acāṇḍāla (in specific, refers to a person whose father is a śūdra and mother is a brāhmaṇa; in general, refers to lower caste or untouchable).

![chandal]() Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 12.4.1.4 says that dogs, boars, and rams are the uncleanest of all animals but Manusmṛti 3.270 says that the pitṝs (ancestors) are delighted when boar meat is offered duringśrāddha (annual ritual in memory of ancestors). So it is unclear why cāṇḍālas have been equated with these two animals; it is also unclear if the word ‘cāṇḍāla’ is used as a generic term for an untouchable or refers specifically to an offspring of a śūdra man and abrāhmaṇa woman.

Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa 12.4.1.4 says that dogs, boars, and rams are the uncleanest of all animals but Manusmṛti 3.270 says that the pitṝs (ancestors) are delighted when boar meat is offered duringśrāddha (annual ritual in memory of ancestors). So it is unclear why cāṇḍālas have been equated with these two animals; it is also unclear if the word ‘cāṇḍāla’ is used as a generic term for an untouchable or refers specifically to an offspring of a śūdra man and abrāhmaṇa woman.Manusmṛti 10.4 (and Mahābhārata / Anuśāsana parva 47.18) clearly states that there are only four varṇas and there is no fifth varṇa. We also know from Manu that children of mixed parentage are pretty much considered equal to śūdras (Manusmṛti 10.41).

However, in some of the other smṛti texts, we find references to a fifth group of people who are below the four varṇas. Gradually, there seems to have been a divide between the śūdras and groups such as cāṇḍālas. The idea of untouchability went to its extreme when some groups of people were segregated as untouchables simply by birth. But this was not the case earlier. Untouchability arose due to a number of reasons:

- People became outcastes or untouchables if they committed a grave sin (see Manusmṛti 9.235-39) but if they performed the appropriate prāyaścitta(atonement, penitence) they were restored to their former place in society.

- People who followed certain professions that were seen as unclean (both physically and morally) became untouchables. People who came in physical contact with such untouchables also became temporarily untouchable.

- People who belonged to a different sect, or who lived in a foreign land were considered untouchables.

- People became untouchable under specific conditions, for a short duration of time. For instance, a person who touches a woman during her monthly period, or a person who touches a woman during the first ten days after delivery of a child, or a person who touches one who is in the mourning period, or a person who carries a corpse to the cemetery. This kind of untouchability was said to be removed by bathing.

Basically, there was a premium on cleanliness of body and mind. Anything that went against that was considered unholy and thus liable to be kept away from the mainstream.

These restrictions seem to be mostly due to religious and hygiene factors rather than any ill-will or racial malice. If we look at the injunctions with respect to untouchability, this point will be clearly illustrated.

For example, a person should not come in physical contact with a woman during her monthly periods. That woman might be one’s mother or wife or daughter. Similarly, one should not come in contact with a person who is mourning the death of a relative – this typically lasts for thirteen days. Therefore, it is often not a matter of superiority as it is of hygiene and religious beliefs.

Varṇa and Industrialization

Before industrialization, the world was localized and slow-moving. Only a handful of people had the opportunity to travel outside their village, let alone the kingdom. And even for those, the speed of travel was determined by the speed of their horse (or their bullock cart, or their legs). For a message to be sent from one part of the kingdom to another, it took time. News travelled slowly.

![factory]() To be constantly aware of what was happening in another part of the kingdom or the continent was unheard of. People were confined to their communities and villages. So they interacted with a small set of people who they were intimately familiar with.

To be constantly aware of what was happening in another part of the kingdom or the continent was unheard of. People were confined to their communities and villages. So they interacted with a small set of people who they were intimately familiar with.Every village had to have people who fulfilled different roles – they needed farmers, ironsmiths, carpenters, priests, accountants, cobblers, servants, weavers, potters, and so forth. Each of them did their task and was part of the community. In such a setting, it is not easy to tyrannize any group because if they refused to carry out their task, the whole village would suffer. Mutual respect was not a courtesy but an important ingredient for survival.

With the advent of industrialization, communication became faster; travel became more convenient and quicker. The world opened out and there were more possibilities for individuals. No longer had they to stick on to their family business – jobs became centralized. Added to this, in India, we had colonial rule. This further complicated the situation and brought about changes in the social structure.

In today’s world varṇa has little relevance. The society has undergone such massive transformations in the past century that the traditional notion ofvarṇa is meaningless. Apart from a sense of belonging and community along with a certain set of practices peculiar to each varṇa, there is little to salvage from this age-old societal model of India. Needless to say, it will be replaced by a different kind of social stratification that is relevant for this day and age.

Some of the orthodox Hindus who might be shocked at such a suggestion must remember that our traditional law texts are not monolithic constructions. The texts were significant at a certain time in history and in a certain place. They are not eternal. They are bound to undergo redrafting and amendments.

Today we don’t refer to any of the ancient texts of law but instead use the Constitution of India, which is applicable to our country and to this time period. And when the need arises, we will make the necessary amendments or changes to it.

The Gautama Dharmasūtra 1.8.24-26 says that people may follow all sorts of rituals and sacraments but if they don’t have the eight qualities of the self (ātmaguṇas) they will fail to attain the highest truth. On the other hand, even if people don’t follow ritual and sacraments but are endowed with the ātmaguṇas, they will attain the highest level.

The eight qualities of the self that Gautama speaks about are: “Compassion to all beings, forbearance, freedom from envy, cleanliness, freedom from over-exertion, auspiciousness, freedom from misery, and freedom from greed.”

These qualities are above all other distinctions of caste, class, or family.

Conclusion

When we look back at the ancient world, we find practices that today we consider ridiculous or abhorrent. However, at a different time, these were the norms. What is remarkable about our ancient thinkers is that they were pragmatic about accepting certain ills in society and made provisions for humane management of the discrepancies that are part of any social system.

Of course, many aspects of the ancient world are irrelevant today while many aspects of the modern world were impossible in earlier periods. We should not lose sight of the overall social, cultural, economic, intellectual milieu of the period of time and geographical location when we pass judgments.

Today, with urban migration, people seem to be getting alienated from culture, and individualism is the new credo. For example, while the first generation of migrants preferred to live in ghettos, holding on to the feelings of nationality or community, the subsequent generations strive towards dissolving differences and merging with the mainstream.

Education and economic stability further reduces social disparity. One of the positive outcomes of this is the fading away of social distinctions. However, the flipside is the rise of new kind of distinction based on economic strength and increase in disparity between rich and poor.

When we look at youngsters in the second or third generation of people who have come out of social discrimination and oppression, the biggest challenges they face are no longer related to social disparity. They face problems that are common to all of the upwardly mobile youth – problems of drugs, alcoholism, discrimination based on economic strength, abuse of technology, etc. This brings us to the fundamental human condition – corruption can seep in anytime, anywhere, and in any manner.

Arjuna raises a beautiful question in the Gītā, “What is that powerful force which compels a man to sin though he doesn’t want to be sinful?” (BG 3.36) Kṛṣṇa’s response is that Desire compels people to commit sinful acts. Andtherefore, it is essential for us to look at this topic with utmost intellectual honesty, keeping our petty biases aside. We have neither to whitewash the evils nor ignore the good.

In India today, more than at any other time, varṇa is used as a perverse tool for political gains. Instead of larger affirmative action, there seems to be a temporary pandering to the demands of a specific group for the sake of garnering votes. Also, with the growth of individualism, there seems to be a growing identity crisis among certain sections of people which naturally leads to a greater bond with family, varṇa, religion, etc.

The society has to therefore promote oneness between the different groups and aim to transcend distinctions instead of rigorously keeping alive the differences.

Of course, the world abounds in duality and we can never avoid discrimination. Also, differences add to the richness of diversity. But as a society we should ensure that this doesn’t lead to disparity and exploitation. In the four holy cities of Haridwar, Prayag (both on the banks of river Ganga), Ujjaini (on the banks of river Kshipra), and Nasik (on the banks of river Godavari), the kumbh mela is celebrated once every twelve years.

In these festivals, apart from the millions of common people who participate, we also see about seventy-five different groups of sannyāsis who come together for the celebration. Among these ascetics, some are believers in murti puja, some are believers in a formless deity; some have deified their spiritual masters, some believe fire to be the ultimate deity, while some others are absolute non-believers who even reject the Vedas. Some of them eat only what they have cooked while others have absolutely no restrictions on food. Some of them are opposed to pilgrimage while for others it is obligatory. Some of them are nationalists, some are not. Some care about social classification and tradition, while others are opposed to it.

They often argue and fight about which group has the honour to bathe first in the river. But such friction is normal. It is not pushed aside but rather sorted out in an amicable manner by means of debate and discussion (not by violence or killing.) This is a wonderful symbol of the diversity and vibrancy in the Hindu tradition. We must try to bring such oneness in variety even in our day-to-day lives.

In spite of all their differences, these sannyāsis come together and celebrate. The holy river unites them all. That ever-flowing river issanātana dharma.

Co-authored by Hari Ravikumar

References:

- Dolgin, Elie. Indian ancestry revealed. http://www.nature.com/news/2009/090922/full/news.2009.935.html

- Kane, Pandurang Vaman. History of Dharmaśātra. Poona: Bhandarkar Oriental Research

- Institute, 1941. Vol. II, Part I. pp. 19-179 (Chapter II. Varṇa, Chapter III. The

- Duties, Disabilities and Privileges of the Varṇas, and Chapter IV. Untouchability)

- Maheshwaranandagiri, Swami. Cāturvarṇya-Bhārata-Samīkṣā.

- Haridwar: Kaivalyananda Saraswati, 1963

- Sreekrishna, Koti and Ravikumar, Hari. The New Bhagavad-Gita.

- Mason: W.I.S.E. Words Inc., 2011

- Ṛgvedasaṃhitā. Vols. 1-36. Ed. Rao, H. P. Venkata. Mysore: Sri Jayachamarajendra

- Vedaratnamala, 1948-62

- The Constitution of India. http://indiankanoon.org/doc/237570/

Dr. Ganesh is a Shatavadhani, a multi-faceted scholar, linguist, and poet and polyglot and author of numerous books on philosophy, Hinduism, art, music, dance, and culture.

see this is how we loose control over our own narrative...

Excellent ! Excellent ! I am delighted to read this ! Thank you so much sir!

Namaste,

Nevertheless this one is more detailed :) !

Thanks for sharing!

Scholarly article. The times are really more brighter and opportunities are unbound these days. All these caste-religion stuff is being kept alive artificially in public, only by the corrupt power mongering political forces. True, that there are some flip sides of this modern era where one can compete freely and use all sorts of intellectual powers or ulterior ways(as political system often does) to amass wealth and create socio-economical divides in the society. This division is growing rapidly and is in turn fostering discrimination - for instance in right to quality education, healthcare, security, etc. As authors rightly remind us towards the end of this article, if humans do everything but fall short of the said qualities, the same problems will persist forever and there is no cure for it.

Thank you. Its high time We Indians discuss this. I have always felt that a vocation based segregation of society is inevitable; if mankind is to survive. Ofcourse without imposition.

I had a few questions:

1. To what extent was Sanskrit used colloquially in classical period?

2. Was there any formal education set-up for general public; where a basic level of skills could be attained, or was it mostly home schooled? What about the under-performing population?

3. Does Jati have any relation with biology (genes)? And are there any indications about how did it become a mainstream classification method without references in texts ? Do regional languages have a contribution towards this?

To answer questions 1 and 2 , please specify which period do you mean exactly by classical period ??

Q3 I don't know

Dr. Tribhuvan Singh - JNU Roundtable on Decolonizing the Academy & Debating breaking India forces

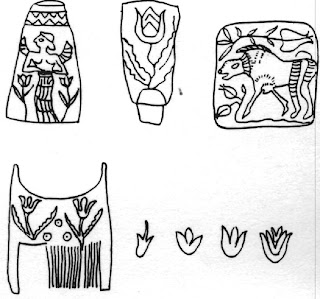

The fillet worn on the forehead and on the right-shoulder signifies one strand; while the trefoil on the shawl signifies three strands. A hieroglyph for two strands is also signified.

The fillet worn on the forehead and on the right-shoulder signifies one strand; while the trefoil on the shawl signifies three strands. A hieroglyph for two strands is also signified.

Button seal. Harappa.

Button seal. Harappa.

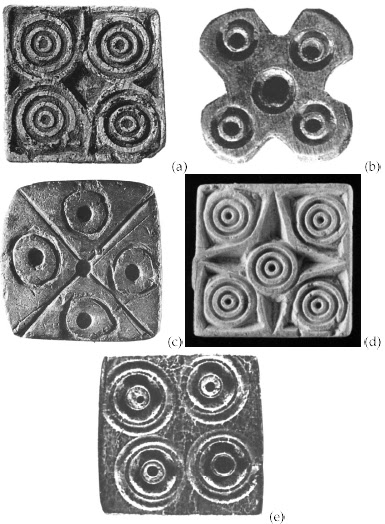

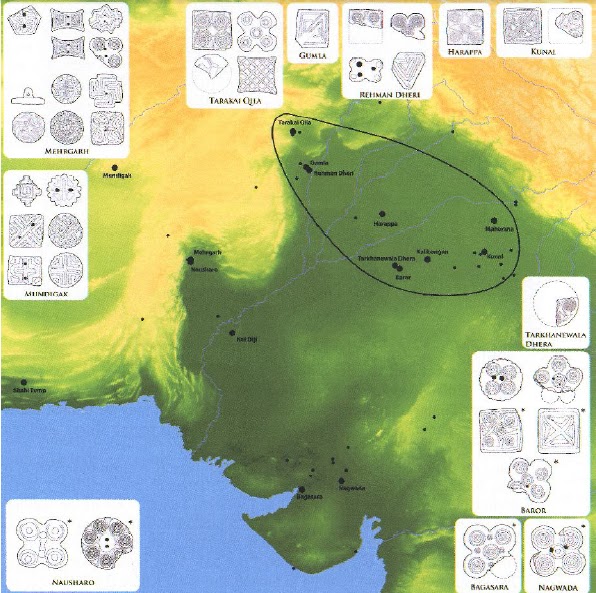

Kot Diji type seals with concentric circles from (a,b) Taraqai Qila (Trq-2 &3, after CISI 2: 414), (c,d) Harappa(H-638 after CISI 2: 304, H-1535 after CISI 3.1:211), and (e) Mohenjo-daro (M-1259, aftr CISI 2: 158). (From Fig. 7 Parpola, 2013).

Kot Diji type seals with concentric circles from (a,b) Taraqai Qila (Trq-2 &3, after CISI 2: 414), (c,d) Harappa(H-638 after CISI 2: 304, H-1535 after CISI 3.1:211), and (e) Mohenjo-daro (M-1259, aftr CISI 2: 158). (From Fig. 7 Parpola, 2013).

This reconstruction by Mahadevan of the 'standard device' on this drawing, connotes 'dotted circles' read rebus as: dhāu'ore'. The process of purification (smoke emanating from the bottom crucible) is comparable to the production of crucible steel using ferrite ores and carbon. This 'device' is an orthographic collage of a lathe PLUS portable brazier. The intention of the engraver is to show the lathe used to pierce holes in beads and also to show dhātu 'strand', dhāi, 'single strand or fibre' rebus: dhāu, dhātu 'ore, element'.

This reconstruction by Mahadevan of the 'standard device' on this drawing, connotes 'dotted circles' read rebus as: dhāu'ore'. The process of purification (smoke emanating from the bottom crucible) is comparable to the production of crucible steel using ferrite ores and carbon. This 'device' is an orthographic collage of a lathe PLUS portable brazier. The intention of the engraver is to show the lathe used to pierce holes in beads and also to show dhātu 'strand', dhāi, 'single strand or fibre' rebus: dhāu, dhātu 'ore, element'.

The pair of 'ovals or ellipses' are infixed with 'notches'. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implement'.

The pair of 'ovals or ellipses' are infixed with 'notches'. khANDA 'notch' rebus: khaNDa 'implement'.

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph.

Mohenjo-daro. m1457 Copper plate with 'twist' hieroglyph.  m478a tablet

m478a tablet

![clip_image062[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0624-thumb.jpg?w=99&h=45)

Preneet Kaur is the wife of

Preneet Kaur is the wife of

Narendra Modi

Narendra Modi  Vijay Chauthaiwale

Vijay Chauthaiwale

Honouring ‘Father of white revolution’ Verghese Kurien, Google on Thursday made a doodle of him on his 94th birth anniversary.

Honouring ‘Father of white revolution’ Verghese Kurien, Google on Thursday made a doodle of him on his 94th birth anniversary.