https://tinyurl.com/ycjldvsb

The cover story of Science Magazine (6 June 2008) has to be updated with the key discovery of Vedic River Sarasvati, decipherment of over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions and new light on the sources of tin which created the Tin-Bronze Revolution of 4th millennium BCE.

The insights provided by Andrew Lawler about a 'Trade-Savvy' civilization, thus should enable researchers to focus on the contributions made by artisans and seafaring merchants of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization.

I have posited a hypothesis that an ancient maritime tin route linked Hanoi (Vietnam) and Haifa (Israel) through the intermediation of Sarasvati Civilization people. This hypothesis is premised on the fact that the largest tin belt of the globe in the river basins of three Himalayan rivers (Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween) which drain a vast region of Ancient Far East. This together with the decipherment of Indus Script inscriptions as wealth accounting ledgers of metalwork necessitates further researches on 1. Formation and evolution of languages of Indian sprachbund and interactions with neighbouring civilizations to the west, to the east and to the north; 2. archaeometallurgical researches to revisit the tin-bronze artifacts discovered all over Eurasia from 4th millennium BCE; and 3. narrate the economic history of ancient Sarasvati civilization marked by the oldest human document, R̥gveda, domestication of maize and millet in 7th millennium BCE, domestication of cotton in 6th millennium BCE in the Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization area.

The decipherment of inscriptions is presented in the following volumes:

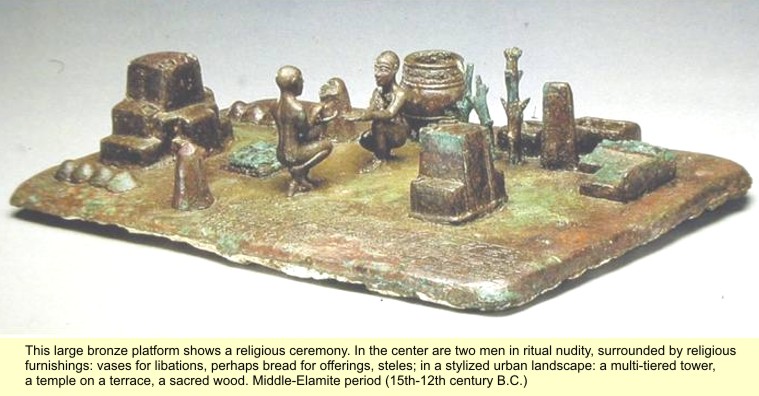

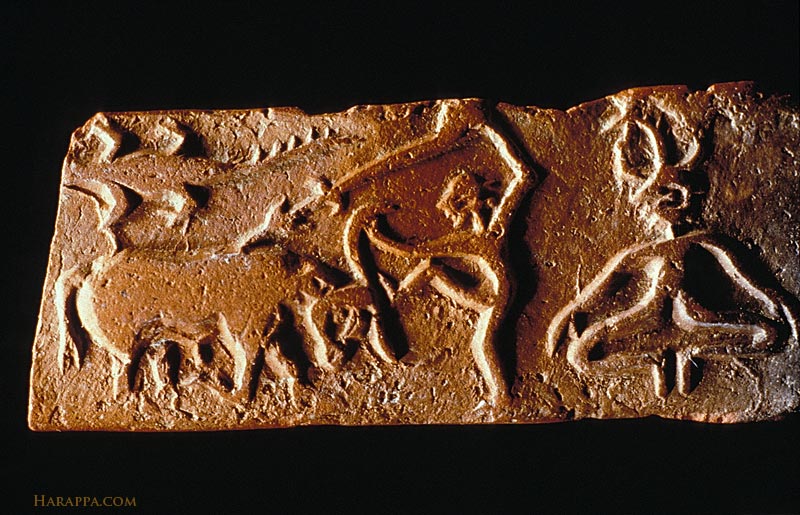

The deciphered messages emphatically document the contributions made by Sarasvati civilization artisans and seafaring merchants in working with varieties of metal alloys, not excluding iron and steel and the advances of cire perdue techniques of metalcasting. The overall impact of the messages is that the contributions made by Sarasvati civilization artisans and seafaring merchants to Tin-Bronze Revolution (necessitated by the scarcity of naturally occurring Arsenical Bronzes) are very significant, exemplified by alloys such as pōḷad 'steel' T (by infusion of element carbon into ferrite ores through the use of wheat-chaff fumes), brass (alloy of copper and zinc), bronze (alloy of copper and tin), pewter (alloy of copper, tin, zinc/spelter). The contributions made are best exemplified by 1. the report of Ernest Mackay who called Chanhudaro the Sheffield of Ancient India; 2. discovery of.four pure tin ingots with Indus script inscriptions from Haifa shipwreck; 3. discovery of ancient zinc distillation plants in Zawar; 4. discovery of Indus Script hypertexts on Dong Son/Karen Bronze drums; 5. discovery of Indus Script hypertexts along the Persian Gulf sites and in Ancient Near East; and 6. discovery of Indus Script hypertexts on Anatolian seals; 6. discovery of a pot in Susa with metal implements and Indus Script hypertexts.

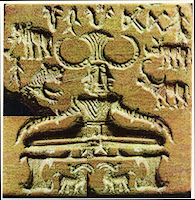

The deciphered messages also explain the significance of the priest statue of Mohenjo-daro as Potr̥, 'purifier'dhā̆vaḍ, 'iron-smelter'. There are also markers of Hindu culture with the preence of śivalinga-s in Harappa, Kalibangan, performance of Soma yajña in Binjor where a fire-altar with octagonal pillar was discovered (R̥gveda and Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa mention such a ketu, 'emblem, pillar' as a proclamation of the performation of a Soma yāga).

Dong Son Bronze drum tympanum; Karen Bronze drum with Indus Script hypertexts with Indus Script hypertext

Dong Son Bronze drum tympanum; Karen Bronze drum with Indus Script hypertexts with Indus Script hypertext Persian Gulf seals with Indus Script hypertexts

Persian Gulf seals with Indus Script hypertexts Susa pot with metal implements and Indus Script hypertexts

Susa pot with metal implements and Indus Script hypertextsIndus Script hypertexts on Anatolian seals (Mitanni)

The hypothesis is also premised on the fact highlighted by Angus Maddison in his study of contributions to world GDP by various regions for over 2000 years since 1 CE. His conclusions presented in a bar chart indicate that India contributed to 33% of world GDP in 1 CE. The 'Trade-Savvy' Sarasvati civilization is the principal cause for this level of contribution made by artisans and seafaring merchants of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization.

S. Kalyanaraman

Sarasvati Research Center

January 16, 2018

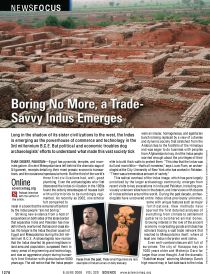

Boring No more, a Trade-Savvy Indus Emerges

- A

- ndrew Lawler

- Science 06 Jun 2008:

Vol. 320, Issue 5881, pp. 1276-1281

DOI: 10.1126/science.320.5881.1276 UNMASKING THE INDUS SCIENCE, VOL. 320, P. 1276-1285, COVER STORY, JUNE 6, 2008 5

![Science: 320 (5881)]() 5 CM. HIGH TERRACOTTA MASK, MOHENJO-DARO

5 CM. HIGH TERRACOTTA MASK, MOHENJO-DARO

- Science 06 Jun 2008:

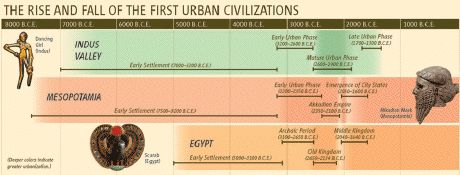

Long in the shadow of its sister civilizations to the west, the Indus is emerging as the powerhouse of commerce and technology in the 3rd millennium B.C.E. But political and economic troubles dog archaeologists' efforts to understand what made this vast society tickTHAR DESERT, PAKISTAN—Egypt has pyramids, temples, and mummies galore. Ancient Mesopotamians left behind the dramatic saga of Gilgamesh, receipts detailing their most prosaic economic transactions, and the occasional spectacular tomb. But the third of the world's three first civilizations had, well, good plumbing. Even the archaeologists who first discovered the Indus civilization in the 1920s found the orderly streetscapes of houses built with uniform brick to be numbingly regimented. As recently as 2002, one scholar felt compelled to insist in a book that the remains left behind by the Indus people “are not boring.”Faces from the past.These small figurines are rare examples of Indus human or deity statuary.CREDIT: © J. M. KENOYER, COURTESY DEPT. OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND MUSEUMS, GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTANStriking new evidence from a host of excavations on both sides of the tense border that separates India and Pakistan has now definitively overturned that second-class status. No longer is the Indus the plain cousin of Egypt and Mesopotamia during the 3rd millennium B.C.E. Archaeologists now realize that the Indus dwarfed its grand neighbors in land area and population, surpassed them in many areas of engineering and technology, and was an aggressive player during humanity's first flirtation with globalization 5000 years ago. The old notion that the Indus people were an insular, homogeneous, and egalitarian bunch is being replaced by a view of a diverse and dynamic society that stretched from the Arabian Sea to the foothills of the Himalaya and was eager to do business with peoples from Afghanistan to Iraq. And the Indus people worried enough about the privileges of their elite to build thick walls to protect them. “This idea that the Indus was dull and monolithic—that's all nonsense,” says Louis Flam, an archaeologist at the City University of New York who has worked in Pakistan. “There was a tremendous amount of variety.”This radical overhaul of the Indus image, which has gone largely unnoticed by the larger archaeology community, emerges from recent visits to key excavations in India and Pakistan, including previously unknown sites here in the desert, and interviews with dozens of Indus scholars around the world. During the past decade, archaeologists have uncovered entire Indus cities previously unknown, some with unique features such as major fortifications. New methods have spurred the first detailed analyses of everything from climate to settlement patterns to butchered animal bones. Growing interest in the role of the ancient economy in spreading goods and ideas has scholars tracing a vast trade network that reached to Mesopotamia itself, where at least one Indus interpreter went native.Even well-combed sites are still full of surprises: The city of Harappa may be 1000 years older and Mohenjo Daro far larger than once thought. And the dramatic “Buddhist stupa” adorning Mohenjo Daro's high mound may in fact date back to the Indus heyday around 2000 B.C.E. “What has changed is the mass of evidence from the past 15 years,” says archaeologist Rita Wright of New York University (NYU), assistant director of the Harappa dig. “There is more data from landscapes and settlements, not just the cities.”But piecing together a cohesive new picture is hampered by the political discord between India and Pakistan. Many foreign archaeologists steer clear of Pakistan because of political instability, while India's government—scarred by colonialism—often discourages researchers from collaborating with European or American teams. A virtual Cold War between the two countries leaves scientists and sites on one side nearly inaccessible to the other. And although Indus sites are finally receiving extensive attention, many unexcavated mounds face destruction from a lethal combination of expanding agriculture, intensive looting, and unregulated urban development. The small coterie of archaeologists from Pakistan, India, America, Europe, and Japan who study the Indus admit that they also share some of the blame. Often slow to publish, this community can be reluctant to work together and lacks the journals and tradition of peer review common to colleagues who focus on other parts of the world. “We're at fault,” says one Indus researcher. “We should be pushing harder to publish and collaborate.”Despite these challenges, the wave of fresh material is leading to a deeper understanding of a culture once considered obscure and impenetrable. The new data paint a far more vibrant and complex picture of the Indus than the old view of a xenophobic and egalitarian society that lasted for only a few centuries before utterly vanishing. “We are rewiring the discussion,” says archaeologist Gregory Possehl of the University of Pennsylvania. Adds Wright: “The Indus is no longer just enigmatic—it can now be brought into the broader discussion of comparative civilizations.”The faceless place

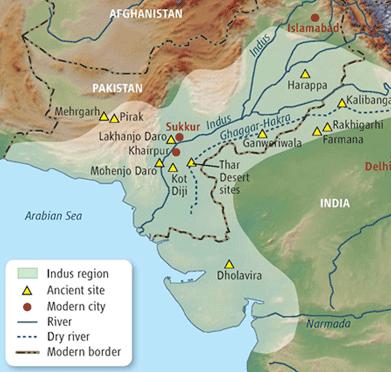

The very existence of the Indus wasn't recognized until more than 100 years after digs began in Egypt and Mesopotamia. It was only in 1924 that archaeologists announced they had found two great cities from a previously unknown urban society that flourished at the same time as the Old Kingdom pyramids and the great ziggurats of Sumer. The cities, Mohenjo Daro and Harappa, thrived for nearly 1000 years along the floodplain of the Indus River, which like the Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates irrigates vast swaths of land that otherwise would be desert (see map).The discovery in what was then British India was stunning: Mohenjo Daro covered at least 200 square hectares and may have housed from 20,000 to 40,000 people. Harappa, 400 kilometers to the north, was only slightly smaller. Both were comparable in size to contemporary cities such as Memphis on the Nile and Ur in today's Iraq. Unlike Egyptian and Mesopotamian cities of the time, however, the Indus builders created well-ordered streets and homes with sophisticated water and sewer systems unmatched until Roman times. The Indus penchant for precise standardization—from tiny weights to bricks to houses to entire cities—was unique in the early historic period. And at Mohenjo Daro, they used expensive baked brick rather than the cheaper mud brick favored in the Middle East, thus leaving behind the only Bronze Age city on Earth where it is still possible to stroll down ancient alleys shaded by intact walls.Yet despite the impressive remains, there were bafflingly few clues to the political or religious systems behind the urban complexes, which seemed to lack the grandeur of Egypt and Mesopotamia. There are no remaining life-sized statues, extensive wall carvings, or elaborate building decorations. The Indus used a still-undeciphered script, but chiefly on small seals, and some scholars believe it was not a script at all (Science, 17 December 2004, p. 2026). Indus scribes did not leave the vast libraries of clay tablets or carved stone inscriptions that have yielded such insight into Mesopotamia and Egypt. Most burials include only a few modest goods, in contrast to the riches of Egyptian tombs. And archaeologists could find no obvious temples or palaces. The few monumental buildings—though given nicknames like “the Granary” and “the Monastery”—had functions still hotly debated.Unlike the many pharaohs, kings, architects, and merchants who show up in sculpture and texts in Egypt and Mesopotamia, few Indus individuals were recorded. Only a few small statues show individuals, such as seated men wearing tunics and a tiny, lithe dancer. The Indus “is something of a faceless sociocultural system,” says Possehl.This led some early and mid-20th century archaeologists to consider the Indus a nonhierarchical society. Others postulated rigid control by a small elite. Given the lack of data to support either interpretation, these ideas may have had more to do with socialist and totalitarian ideas popular at the time than with the ancient pastPicking at the past.

Workers at Farmana in India uncover clues to Indus architecture.CREDIT: A. LAWLER/SCIENCEThat first generation of archaeologists did agree that the Indus was an impressive but brief flash in the pan without deep roots. Because there was no evidence of previous settled life in the region, they surmised at the time that the Indus people absorbed urban ideas from Mesopotamia—2500 kilometers to the west—and rapidly created a quirky two-city state around 2600 B.C.E., which then vanished equally abruptly by 1800 B.C.E. The 1947 partition of India, creating the new nations of India and Pakistan, drew a line through the Indus heartland and left Indus archaeology largely an academic backwater for nearly a half-century.Round to square

The assumption that the Indus did not spring from local culture began to unravel in the 1970s, when a French-led team excavated a Neolithic site called Mehrgarh dating to 7000 B.C.E. in the Baluchistan hills on the western fringe of the Indus valley. The town included many of the trappings of later Indus life, from mud-brick houses and copper tools to wheat, barley, sheep, goats, and cattle. Although some plants may have arrived from the Near East, goats and cattle were likely domesticated locally, and possibly sheep as well. A partially worked elephant tusk demonstrates that craft specialists were already plying their trade, and lapis lazuli jewelry from Afghanistan and marine shells from the distant coast show long-distance trade networks.The site is now widely accepted as a precursor to the Indus and clear proof of the indigenous nature of the later civilization. That idea gets new support from surveys here in the Thar Desert, on the eastern edge of the Indus valley. This area was long assumed to have been largely uninhabited before the rise of the Indus cities. But hundreds of small sites now show that humans lived here on the plains, not just in the Baluchistan hills, for several millennia prior to the rise of the Indus, says archaeologist Qasid Mallah of Shah Abdul Latif University in Khairpur. Taking a reporter on a tour across dunes covered in scrub, he pointed out huge piles of chert used to make blades by the Neolithic predecessors of the Indus.Burnt out.

Qasid Mallah points to a burn layer at Kot Diji, perhaps a sign of ancient conflict.CREDIT: A. LAWLER/SCIENCEStill, the sudden appearance of fully formed urban areas remains a puzzle. Indus cities appeared starting about 2600 B.C.E.—600 years after the first cities sprouted in Mesopotamia—and typically arose on virgin soil rather than atop earlier settlements. Some older towns date back about a millennium earlier, but most of these appear to have suffered catastrophic fires and were abandoned at the dawn of the new urban era. A site called Kot Diji a short drive from the Thar Desert shows the scars, says Mallah. The mound is an archaeological layer cake built up over centuries, with a dark layer of ash distinctly visible in a band several meters above the plain.EAST OF EDEN.Sprawling between the Himalaya Mountains and the Arabian Sea, the Indus civilization covered a larger area than Egypt or Mesopotamia (inset) and boasted at least a half-dozen large cities and many smaller towns and villages. Trading posts stretched from northern Afghanistan to Oman, and goods traveled over both land and sea routes.Some scholars argue that these burn layers record conflict between the earlier towns and new cities. But Mallah and many of his colleagues say there is not enough evidence to make that leap. Whoever constructed the cities did make distinct changes, creating new pottery styles and introducing metal forms such as razors and fishhooks. But they also drew on the long cultural history of the region and don't appear to be outside invaders, says Mallah.In fact, new evidence suggests that not all the major cities were built from scratch. At an ongoing dig at Harappa, led by Richard Meadow of Harvard University and Jonathan Kenoyer of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, the team has found evidence of occupation dating to as early as 3700 B.C.E. By 3300 B.C.E., Harappa was a modest village of 10 square hectares but with streets running in a gridlike pattern and bricks of two standard sizes—clear foreshadowing of orderly Indus construction. “And they were trading lapis, shells from the coast, copper, and carnelian across a vast area,” says Kenoyer. One of his graduate students, Randall Law, just published a dissertation pinpointing for the first time the far-flung origin of the many varieties of stone used by Indus artisans.At a site called Farmana in the intensely farmed region west of Delhi, across the Pakistan border from Harappa, this evolution from a village of huts to sophisticated urban architecture is remarkably visible. At this previously unexcavated site, Vasant Shinde of Deccan College in Pune and his team have uncovered remains of an oval-shaped hut dating to about 3500 B.C.E., a pit dwelling made with wattle and daub and plastered walls, of a type seen today in the region. A few meters away is a level from 1000 years later where the houses have morphed into a rectangular shape and resemble those of the later Indus, except for postholes on the periphery that may have held up a roof. A few meters and 2 centuries from that trench is classic urban Indus: the clear outline of a large house with more than a dozen rooms, including a plastered bathroom, and a 20-meter-long wall fronting a long street nearly 4 meters wide. “You can see how beautifully this was planned,” Shinde says, pointing at the fine brickwork and straight lines. “There are no postholes, and the bricks are of the same ratio as at Harappa.” Thus from both sides of the border, the newest evidence not only underscores the local origins of the Indus, it also reveals in situ evolution. Says Mallah, “We believe that urbanization was a gradual process.”Gated communities

For the first half-century after its discovery, the Indus was virtually synonymous with Mohenjo Daro and Harappa. No other major cities were known. But along with 1000 smaller sites, archaeologists now count at least five major urban areas and a handful of others of substantial size. These sites reveal new facets of Indus life, including signs of hierarchy and regional differences that suggest a society that was anything but dull and regimented.Water works.

This drain from Harappa is part of a sophisticated water system that set the Indus apart from its Mesopotamian and Egyptian cousins.CREDIT: © J. M. KENOYER, COURTESY DEPT. OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND MUSEUMS, GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTANTake Dholavira, 800 kilometers south of Harappa in the Indian state of Gujarat. Covering 60 square hectares, it thrived for nearly 1000 years with perhaps seasonal access to the Arabian Sea. Evidence from excavations during the 1990s reveals a city that apparently included different classes of society. “Here you have meticulous planning, monumental and aesthetic architecture, a large stadium, and an efficient water-management system,” says R. S. Bisht, the Archaeological Survey of India scientist who oversaw the digs. Although still largely unpublished, archaeologists around the world say Bisht's finds are truly extraordinary.In Dholavira's central citadel is an enormous structure—which Bisht dubs “the castle”—with walls that are an astounding 18.5 meters wide at their base. Next to it is an enclosed area Bisht calls “the bailey” that may have housed an elite. “This shows that Harappan [Indus] society was highly structured,” says Bisht. “There was a hierarchy.” Nearby is a huge mud-brick platform adorned with rare pink-and-white clay decoration and what Bisht believes was a multipurpose stadium ground stretching nearly the length of three football fields and including terraces to seat thousands of people. No structures of similar size are found at other Indus cities. And though the acropolis of an Indus city is usually walled, Dholavira's acropolis, middle town, lower town, and a series of water tanks are surrounded by an enormous wall measuring nearly 800 meters on one side and more than 600 meters on the other.The finds at Dholavira are part of a growing body of data that lay to rest the idea of an egalitarian or a totalitarian society. For example, although most Indus graves are modest, at Kalibangan in India the remains of an elderly man lie in a mud-brick chamber beside 70 pottery vessels. At Harappa, another elderly man shares his tomb with 340 steatite beads plus three beads of gold, one of onyx, one of banded jasper, and one of turquoise. Another high-status Harappan went to rest in an elegant coffin made of elm and cedar from the distant Himalayas and rosewood from central India.Urban house sizes also vary much more dramatically than early excavators thought, says Wright, who works on the Harappa team. Then, as now, location was a matter of status: She notes that whereas some larger dwellings have private wells and are next to covered drains, more modest houses face open drains and cesspools.Like elites everywhere, high-status Indus people were able to acquire high-quality goods from master craftsmen to denote their wealth. They owned finely crafted beads made in a wide variety of stone, glazed pottery called faience, and ornamentation in gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, and electrum (a gold and silver alloy). For those with less means, beaded necklaces of cheap terra cotta imitated those of semiprecious stone. Anthropologist Heather Miller of the University of Toronto in Canada and Massimo Vidale, a visiting professor at the University of Bologna in Italy, concluded in a 2001 paper that the Indus were capable of “technological virtuosity.” A recent find at Harappa tentatively dated to 1700 B.C.E. may prove to be the world's oldest glass, says Kenoyer.Such goods are found across the region, including at newly discovered cities. For example, recent excavations at Rakhigarhi, 340 kilometers southeast of Harappa in rural India, turned up a bronze vessel decorated in gold and silver along with a foundry containing thousands of semiprecious stones, demonstrating extensive craft production and bolstering the notion of an elite. At another new site called Ganweriwala, deep in the desert region south of Harappa, preliminary fieldwork by Farzand Masih of Punjab University in Pakistan has yielded finely made shell bangles and a variety of agate, terra cotta, and steatite beads.Yet despite the trappings of wealth for some, there is little evidence of the vast divide that separated pharaoh from field hand in Egypt. “This was an enormously innovative civilization,” says Michael Jansen of RWTH Aachen University in Germany. “Rather than spend their time on monuments as in Egypt, they built practical things that benefited the inhabitants.”The newly discovered cities also reveal a surprisingly diverse urban life. Rakhigarhi contains the usual Indus amenities—paved streets, brick-lined drains, orderly planning—that are conspicuously lacking in the current town that covers the highest mound. But instead of following a grid, the ancient streets radiate from the city's east gate. As at Harappa, there is evidence of settlement centuries before the urban explosion rather than the clean-slate approach typical of other Indus cities. Dholavira has its own peculiarities, including large amounts of dressed stone from a local quarry in addition to the standard baked or mud brick. A 10-symbol signboard was posted on the gate leading into the citadel, an unusual use of a script typically found only on small seals or pots. Grave rites also seem diverse. At Mohenjo Daro, there is no evidence for formal burials at all. At Dholavira, Bisht found a set of tomblike chambers containing an unusual variety of grave goods such as beads and pots but no traces of skeletons; he speculates that the bodies may have been cremated.How the Indus people viewed life after death remains elusive. And the lack of temples adds to the difficulties in understanding their overall religious beliefs. A rare clue to religious practice may have emerged from now-barren Ganweriwala, which once bloomed thanks to the ancient Ghaggar-Hakra River. In his preliminary work there last year, Masih found a seal with the figure of a person or god in a yogalike pose and an apparent devotee below; on the reverse side is Indus script. The seal is similar to others found at Mohenjo Daro and dubbed “proto-Shiva” by some for its similarity to the Hindu deity. The seal has fueled speculation that the religious traditions of the Indus lived on beyond the urban collapse of 1800 B.C.E. and helped lay the basis for Hinduism (see p. 1281). Horned figures on a variety of artifacts may depict gods, as they often do in Mesopotamia.The frustrating lack of evidence has fueled other theories that remain tenuous. Jansen and Possehl suggest that the Indus obsession with baths, wells, and drains reveals a religious ideology based on the use of water, although other scholars are skeptical.Masters of trade

While evidence accumulates from Indus cities, other insights are coming from beyond the region, as artifacts from Central Asia, Iraq, and Afghanistan show the long arm of Indus trade networks. Small and transportable Indus goods such as beads and pottery found their way across the Iranian plateau or by sea to Oman and Mesopotamia, and Indus seals show up in Central Asia as well as southern Iraq. An Indus trading center at Shortugai in northern Afghanistan funneled lapis to the homeland. And there is strong evidence for trade and cultural links between the Indus and cities in today's Iran as well as Mesopotamia.Holding a pose?

This rare seal may hint at the ancient origins of yoga and the Hindu god Shiva.CREDIT: © J. M. KENOYER, COURTESY DEPT. OF ARCHAEOLOGY AND MUSEUMS, GOVERNMENT OF PAKISTANTextual analysis of cuneiform tablets coupled with recent excavations along the Persian Gulf also show that Indus merchants routinely plied the Arabian Sea and Persian Gulf, likely in reed boats with cotton sails. “They were major participants in commercial trade,” says Bisht, who sees Dholavira and other sites along the coast as trading centers thanks to monsoon winds that allowed sailors to cross 800 kilometers of open waters speedily. “These people were aggressive traders, there is no doubt about it,” adds Possehl, who has found Indus-style pottery made from Gujarat clay at a dig in Oman. Archaeologist Nilofer Shaikh, vice chancellor of Latif University, takes that assertion a step further, arguing that “the Indus people were controlling the trade. They controlled the quarries, the trade routes, and they knew where the markets were.”She points out that although Indus artifacts spread far and wide, only a small number of Mesopotamian artifacts have been found at Indus sites. Evidence suggests that some Indus merchants and diplomats lived abroad, although the trade was certainly two-way. An inscription from the late 3rd millennium B.C.E. refers to one Shu-ilishu, an interpreter from Meluhha, reports NYU's Wright in a forthcoming book. What may be Shu-ilishu and his wife are featured on a seal wearing Mesopotamian dress. There is some evidence for a village of Indus merchants between 2114 and 2004 B.C.E. in southern Iraq. And “a man from Meluhha” knocked out someone's tooth during an altercation and was made to pay a fine, according to a cuneiform text, hinting at a life that was neither faceless nor boring.Indus archaeologists still confront fundamental research questions, including how a far-flung array of cities adopted standardized measures. There is little or no data on how the Indus people governed themselves, what language they spoke, and whether they engaged in war. Some researchers envision a collection of city states, while others imagine regional powers that jockeyed for influence but generally cooperated. What is clear is that the organization differed from the pharaonic ways of Egypt and the rival kingdoms of Mesopotamia. “We don't need to use the models from the Near East,” says Kenoyer. “What was once seen as a monolithic state was actually a highly diverse set of multiple centers of power that negotiated across a large landscape.”With barely one-tenth of the 1000-plus known Indus sites examined, archaeologists say the next frontier is the smaller sites that could reveal more about day-to-day life. That could fill in the gaps about how the Indus people worshipped, traded, and governed themselves. “There are thousands of villages,” says Shinde during lunch break at the Farmana dig. “And it is our fault that we only go to the big sites.” Researchers are also bringing the latest archaeological tools to bear on Indus artifacts, closely examining the origins of stone used in beadwork, the prevalence of certain animals and plants, and even the methods used in butchering. Archaeologists also recognize an urgent need to chart climate change throughout the region during the Indus era. “It's a great tragedy,” says Bisht. “It is a book waiting to be read.” Whatever archaeologists uncover in coming years, the revised story of the Indus civilization is sure not to be a dull read.

The opening few paragraphs of the lead essay – “Boring No More, a Trade-Savvy Indus Emerges” – give a flavor of the key argument:

However, the problems remain serious. As the author points out:THAR DESERT, PAKISTAN–Egypt has pyramids, temples, and mummies galore. Ancient Mesopotamians left behind the dramatic saga of Gilgamesh, receipts detailing their most prosaic economic transactions, and the occasional spectacular tomb. But the third of the world’s three first civilizations had, well, good plumbing. Even the archaeologists who first discovered the Indus civilization in the 1920s found the orderly streetscapes of houses built with uniform brick to be numbingly regimented. As recently as 2002, one scholar felt compelled to insist in a book that the remains left behind by the Indus people “are not boring.”Striking new evidence from a host of excavations on both sides of the tense border that separates India and Pakistan has now definitively overturned that second-class status. No longer is the Indus the plain cousin of Egypt and Mesopotamia during the 3rd millennium B.C.E. Archaeologists now realize that the Indus dwarfed its grand neighbors in land area and population, surpassed them in many areas of engineering and technology, and was an aggressive player during humanity’s first flirtation with globalization 5000 years ago. The old notion that the Indus people were an insular, homogeneous, and egalitarian bunch is being replaced by a view of a diverse and dynamic society that stretched from the Arabian Sea to the foothills of the Himalaya and was eager to do business with peoples from Afghanistan to Iraq. And the Indus people worried enough about the privileges of their elite to build thick walls to protect them. “This idea that the Indus was dull and monolithic–that’s all nonsense,” says Louis Flam, an archaeologist at the City University of New York who has worked in Pakistan. “There was a tremendous amount of variety.”

… Even well-combed sites are still full of surprises: The city of Harappa may be 1000 years older and Mohenjo Daro far larger than once thought. And the dramatic “Buddhist stupa” adorning Mohenjo Daro’s high mound may in fact date back to the Indus heyday around 2000 B.C.E.

…piecing together a cohesive new picture is hampered by the political discord between India and Pakistan. Many foreign archaeologists steer clear of Pakistan because of political instability, while India’s government–scarred by colonialism–often discourages researchers from collaborating with European or American teams. A virtual Cold War between the two countries leaves scientists and sites on one side nearly inaccessible to the other.

One key in this new wave is the knowledge that was unleashed with the discovery, in the 1970s by a French-led team, of Mehrgarh“dating to 7000 B.C.E. in the Baluchistan hills on the western fringe of the Indus valley.” The Science article points out:

[Mehrgarh] is now widely accepted as a precursor to the Indus and clear proof of the indigenous nature of the later civilization. That idea gets new support from surveys here in the Thar Desert, on the eastern edge of the Indus valley. This area was long assumed to have been largely uninhabited before the rise of the Indus cities. But hundreds of small sites now show that humans lived here on the plains, not just in the Baluchistan hills, for several millennia prior to the rise of the Indus, says archaeologist Qasid Mallah of Shah Abdul Latif University in Khairpur.

Of course many mysteries remain – the largest probably about language and civilizational collapse – however, there is a key, and exciting difference:

For the first half-century after its discovery, the Indus was virtually synonymous with Mohenjo Daro and Harappa. No other major cities were known. But along with 1000 smaller sites, archaeologists now count at least five major urban areas and a handful of others of substantial size. These sites reveal new facets of Indus life, including signs of hierarchy and regional differences that suggest a society that was anything but dull and regimented.

One of the most fascinating aspect is about international trade:

While evidence accumulates from Indus cities, other insights are coming from beyond the region, as artifacts from Central Asia, Iraq, and Afghanistan show the long arm of Indus trade networks. Small and transportable Indus goods such as beads and pottery found their way across the Iranian plateau or by sea to Oman and Mesopotamia, and Indus seals show up in Central Asia as well as southern Iraq. An Indus trading center at Shortugai in northern Afghanistan funneled lapis to the homeland. And there is strong evidence for trade and cultural links between the Indus and cities in today’s Iran as well as Mesopotamia.

…”These people were aggressive traders, there is no doubt about it,” adds [Gregory] Possehl [ of the University of Pennsylvania], who has found Indus-style pottery made from Gujarat clay at a dig in Oman. Archaeologist Nilofer Shaikh, vice chancellor of Latif University, takes that assertion a step further, arguing that “the Indus people were controlling the trade. They controlled the quarries, the trade routes, and they knew where the markets were.”She points out that although Indus artifacts spread far and wide, only a small number of Mesopotamian artifacts have been found at Indus sites. Evidence suggests that some Indus merchants and diplomats lived abroad, although the trade was certainly two-way. An inscription from the late 3rd millennium B.C.E. refers to one Shu-ilishu, an interpreter from Meluhha [a reference to the Indus civilization], reports NYU’s Wright in a forthcoming book. What may be Shu-ilishu and his wife are featured on a seal wearing Mesopotamian dress. There is some evidence for a village of Indus merchants between 2114 and 2004 B.C.E. in southern Iraq. And “a man from Meluhha” knocked out someone’s tooth during an altercation and was made to pay a fine, according to a cuneiform text, hinting at a life that was neither faceless nor boring.

There is much more in the full report to keep the reader engrossed. How archeaologists are chronically short of resources. How archaeologist Farzand Masih from Punjab University, Lahore, who is excavating at Ganweriwala, Pakistan, and Vasant Shinde from Deccan College, Pune, who is excavating at Farmana, India, work a mere 200 kilometers apart but cannot collaborate on their findings. How part of the last remains of a 5000-year-old city known as Lakhanjo Daro has been lost to “development” and a factory is being built over the site. How the politics of religion threatens to undermine scientific integrity and matters of archeology are being played out in the Indian parliament as well as the courts. How looters and thieves are running away with treasures of the Indus civilization. And much more.

There is much more in the full report to keep the reader engrossed. How archeaologists are chronically short of resources. How archaeologist Farzand Masih from Punjab University, Lahore, who is excavating at Ganweriwala, Pakistan, and Vasant Shinde from Deccan College, Pune, who is excavating at Farmana, India, work a mere 200 kilometers apart but cannot collaborate on their findings. How part of the last remains of a 5000-year-old city known as Lakhanjo Daro has been lost to “development” and a factory is being built over the site. How the politics of religion threatens to undermine scientific integrity and matters of archeology are being played out in the Indian parliament as well as the courts. How looters and thieves are running away with treasures of the Indus civilization. And much more.https://www.scribd.com/document/37199095/Indus-Valley

Indus Valley by gupadupa on Scribd

5 CM. HIGH TERRACOTTA MASK, MOHENJO-DARO

5 CM. HIGH TERRACOTTA MASK, MOHENJO-DARO Holding a pose?

Holding a pose?

/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/Daro-470.jpg)

Heap of dust

Heap of dust

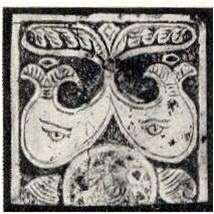

Adjacent to the ground in Dholavira, where two stambhas exist, is a raised place with an 8-shaped structure. This shape compares with a furnace of Harappa.

Adjacent to the ground in Dholavira, where two stambhas exist, is a raised place with an 8-shaped structure. This shape compares with a furnace of Harappa.  Furnace. Harappa

Furnace. Harappa

Santali glosses

Santali glosses

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.

Horned person. Terracotta. Harappa.