Shouldn't Stellarium opensource be adapted to produce Skymaps of Veda calendar, say, from 7th millennium BCE? As of version 0.8.1,Stellarium contains 4 different sets of skycultures: Western, Chinese, Ancient Egyptian, and Polynesian. http://stellarium.sourceforge.net/wiki/index.php/Sky_cultures … The attached image shows date of Mahabharata war Nov. 22, 3067 BCE (pace Prof. Narahari Achar).

Plea for Stellarium for Veda skyculture

↧

↧

The valour of Pushya Mitra Shunga -- Shatavadhani R. Ganesh

Note:

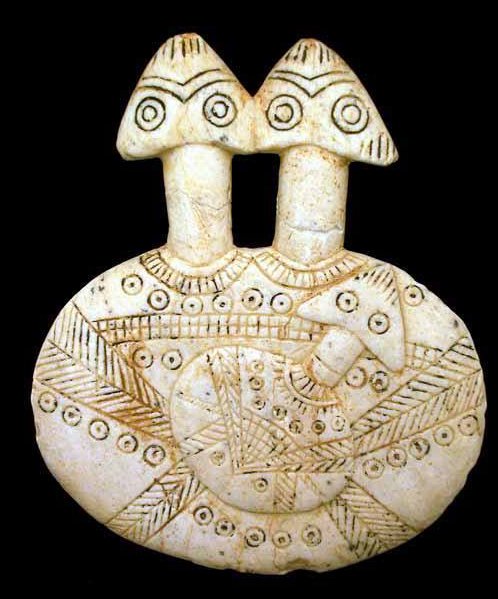

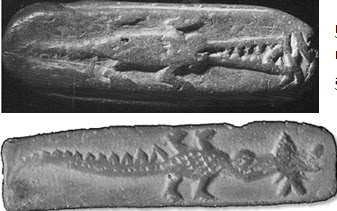

Bharhut and Sanchi stupa art history is a revelation. The sculptural friezes are a continuum of Indus Script hypertexts. As evidenced by an inscription at Sanchi, the sculptures were made by Ivory carvers. Ivory carvers' models for torana-s are available from Begram which substantiate this inscription. The Begram ivory carvers are in Indus Script Hypertext tradition when they signify the purpose of the toranas- by the 'srivatsa' symbol. I have proved that this symbol is a composition of Indus Script hieroglyphs:

Pair of fish fins tied together: ayo'fish' rebus: aya'iron'ayas'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā'fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'. Thus, the gateways proclaim the alloy metal mints at both Sanchi and Bharhut monuments.

This hypertext continues in Amaravati scultural tradition to signify metalwork wealth creation proclamations..

S. Kalyanaraman

Marxist-Communist historians claim that because Pushyamitra Shunga was a brāhmaṇa, all events that occurred during his period were merely the revolt of brāhmaṇas. These incidents symbolize the enmity that brāhmaṇas had against Ashoka and his heritage. Contrary to their claims, varṇa doesn’t occupy a significant place in this.

The Shungas weren’t in power for a long period. The Kanvas, who succeeded them were brāhmaṇas too. If the Shunga reign was indeed a brāhmaṇa rebellion, the Kanvas should not have opposed them. In the realm of authority and position, considerations of varṇa and morality are only secondary to the human impulse of Selfishness. People from all social backgrounds succumb to avarice. The main challenge that arose back then was the responsibility of national security. When the commander Pushyamitra realized this, he assumed the reins of power.

Others claim that Pushyamitra Shunga was an enemy of Buddhists, he destroyed the foundational texts of Buddhism, and murdered Buddhist bhikkus. But then, they forget an important fact in this context: The Bharhut Stūpa is among the most exquisite stūpas of ancient India with extraordinary sculptural craftsmanship. It was entirely commissioned and built under the supervision of Pushyamitra Shunga. Similarly, the exceptional balustrade surrounding the Sanchi Stūpa standing resolute till date, was built by the selfsame Pushyamitra Shunga.

Coins from the Shunga Period

It was the Shatavahanas who built the four ornate doors outside the balustrade. The Shatavahanas were not Buddhists, but firm adherents of the Vedic tradition. They performed grand yajñas like Aśvamedha and Vājapeya. It was the same Shatavahanas who built the stūpa at Nagarjunakonda. When we notice the pravaras of the Shatavahana kings—Gautamiputra Shatakarni, Vasishtiputra Shatakarni, etc.—it becomes evident that their mothers too were kṣatriyas and retained the gotras belonging to tradition of the hallowed Vedic ṛṣis. The archaeological remnants of their yajña altars survive to this day.[1]

In those times, even the adherents of the Vedas did not reject Buddhism. The Shatavahanas built not merely the doors to the Sanchi Stupa, but built the entire stupa at Amaravati. Some of their remains are on display at the Madras Museum and the British Museum. The sort of hostility[2] that exists today among the Hindus, Buddhists, and Jains never existed in those times even at the level of the Rājagurus. The authors of some sectarian works might have been roused by attachment towards their chosen sect and hatred towards the others. It will be erroneous to ascribe such sectarian zeal both to the common folk and to the kings. Besides, a text like Ashokavadana authored by fanatic Buddhists, which is far from the truth cannot be held as a primary source. Further, the Shunga-haters cleverly gloss over the mention of Ashoka’s mass murder of Jains in the same Ashokavadana. How shall we label this chicanery? Therefore, one must be careful while relying on the mythical narrations found in sectarian works.

It is also worth recalling that in Pushyamitra Shunga’s time, several Buddhists were sentenced for treason for colluding with foreign invaders. We can examine this in detail when we discuss the Gupta period.

Magnanimity of the Indian Tradition of Kṣātra

The pre-eminent among the Guptas was Chandragupta Vikramaditya (Chandragupta II), a great bhāgavata (devotee of Viṣṇu). His son Kumaragupta worshipped both Śiva and Skanda. Father and son worshipped different deities. What does this show? Though their personal preference was Śiva or Skanda, they did not impose it upon their subjects. Several records show that Kavikulaguru Kālidāsa, a supreme devotee of Śiva, was in the court of the great Viṣṇu devotee Chandragupta Vikramaditya.

All the mayhem surrounding Śaiva, Vaiṣṇava, Śākta, etc. was restricted to a few people who took mythological ideas literally and wrote about them as if they were real episodes. We can notice sectarian hostility in Buddhist, Jain, and <Sanatanic> texts. For instance, the Madhaviyashankaravijaya has been attributed to Vidyaranya. In reality, Vyasachala, an obscure poet, has composed this work. As a work of poetry, it is good, but in many places, it is historically inaccurate and far from the truth. In places, it also defames ācārya Śaṅkara. “There was a king named Sudhanva. The Mīmāṃsā scholar Kumarilabhatta adorned his court. There was a clash between him and the Buddhists. The defeated Buddhists were boiled in water mixed with slaked lime (Calcium Hydroxide) and were used in oil-pressing labour.” The text contains this and several other outlandish episodes. In the history of India, we don’t find any king with the name of Sudhanva – be it among the Magadhas, the Vidarbhas, the Cholas, the Cheras, the Pandyas, or the Pallavas. Ācārya Śaṅkara lived between 630-662 CE. This dating is the result of rigorous scientific research in recent years. Therefore, it becomes evident that the author of Madhaviyashankaravijaya was imbued with sectarian fanaticism.

Rāmanuja’s guru was the Advaiti Yadavaprakasha. The historical fact, however, is that he was not an advaiti. His Brahma-sūtra-bhāṣya is itself sufficient proof for this. Yadavaprakasha followed the bhedābheda school of Vedānta. This is quite close to the Rāmanuja school of philosophy. Sectarian texts baselessly allege that Yadavaprakasha tortured Rāmanuja badly. No historical evidence exists for such allegations. There are also stories that Krimikanta Chola (Karikala Chola) conspired to assassinate Rāmanuja. In truth, this is a great insult to both Rāmanuja and the Chola king. In fact, we do not see the name of this king in history! The Cholas were not zealous Saivaites. They patronized all sects equally. Several stotras and poems in praise of Viṣṇu were composed in the Chola period. In the grand Chola temples, we see many beautiful vigrahas of Viṣṇu.

Any Hindu king who was extremely sectarian could never hope to rule over his subjects. It was impossible to survive by inflicting tyranny upon the people. The religious tolerance during Akbar’s reign was absent in Aurangzeb’s regime, which is why he faced such widespread rebellion.[3] It is a fact that Pushyamitra Shunga was a liberal ruler, who greatly respected all sects.

There is also an allegation that the Guptas were enemies of Buddhists. But a study of history will show that the great Buddhist Vasubandhu was a minister in the court of Samudragupta.

To be continued…

Translated by Sandeep Balakrishna and Hari Ravikumar from the Kannada original.

[1] In recent times, a few malicious minds have claimed that Adi Shankara destroyed the stupas at Nagarjunakonda. Based on rumours and concocted legends, they have built an evil edifice of distorted history and are savouring its luxuries. However, several years ago, great scholars like Bharat Ratna Pandrurang Vaman Kane and Govinda Chandra Pande demolished such theories as naked lies. Besides, the yajna altars and caityas at Nagarjunakonda have also been ruined. It is beyond doubt that these monuments as well as the stupa were decimated by the dear friends of the Communist historians, the barbaric Islamic hordes.

[2] Translators’ Note: It must be noted that the ‘hostility’ between these schools (of philosophy) amounts to verbal duels and name-calling; physical violence is neither prescribed nor practiced against the other. In the entire history of India, the violent confrontations between these schools have been minimal to the extent of being non-existent. It is incomparable to the extreme violence that characterizes the Abrahamic religions – both amongst themselves as well as against non-Abrahamic systems.

[3] Translators’ Note: The notion of Akbar’s religious tolerance and magnanimity towards Hindus must be seen in the context of the larger history of Hindu and Islamic empires. It must be contrasted with the typical religious bigotry of an average Muslim king all the way from the Delhi Sultanate and Akbar’s grandfather, Babur. Therefore, Akbar’s so-called religious tolerance was an aberration and when juxtaposed with the average Hindu king, he pales in comparison.

Shatavadhani Dr. R. Ganesh

Dr. Ganesh is a 'shatavadhani' and one of India’s foremost Sanskrit poets and scholars. He writes and lectures extensively on various subjects pertaining to India and Indian cultural heritage. He is a master of the ancient art of avadhana and is credited with reviving the art in Kannada. He is a recipient of the Badarayana-Vyasa Puraskar from the President of India for his contribution to the Sanskrit

http://prekshaa.in/valour-pushyamitra-shunga/#.WlQHDzfhXIW

↧

It’s Time to Bomb North Korea, destroy Pyongyang's nuclear arsenal -- Edward Luttwak

A neocon who previously advised the State Department, the National Security Council and the U.S. military recommends that the U.S. bomb North Korea even if it means sacrificing the lives of many of the 20 million South Koreans living in and around Seoul.

U.S. Air Force B-1B Lancer bombers flying with F-35B fighter jets and South Korean Air Force F-15K fighter jets on September 18, 2017 in Gangwon-do, South Korea. (Getty Images)

It’s Time to Bomb North Korea

Destroying Pyongyang’s nuclear arsenal is still in America’s national interest.

Each test would have been an excellent occasion for the United States to finally decide to do to North Korea what Israel did to Iraq in 1981, and to Syria in 2007 — namely, use well-aimed conventional weapons to deny nuclear weapons to regimes that shouldn’t have firearms, let alone weapons of mass destruction. Fortunately, there is still time for Washington to launch such an attack to destroy North Korea’s nuclear arsenal. It should be earnestly considered rather than rejected out of hand.Of course, there are reasons not to act against North Korea. But the most commonly cited ones are far weaker than generally acknowledged.

One mistaken reason to avoid attacking North Korea is the fear of direct retaliation.

One mistaken reason to avoid attacking North Korea is the fear of direct retaliation.The U.S. intelligence community has reportedly claimed that North Korea already has ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads that can reach as far as the United States. But this is almost certainly an exaggeration, or rather an anticipation of a future that could still be averted by prompt action. The first North Korean nuclear device that could potentially be miniaturized into a warhead for a long-range ballistic missile was tested on September 3, 2017, while its first full-scale ICBM was only tested on November 28, 2017. If the North Koreans have managed to complete the full-scale engineering development and initial production of operational ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads in the short time since then — and on their tiny total budget — then their mastery of science and engineering would be entirely unprecedented and utterly phenomenal. It is altogether more likely that they have yet to match warheads and missiles into an operational weapon.

It’s true that North Korea could retaliate for any attack by using its conventional rocket artillery against the South Korean capital of Seoul and its surroundings, where almost 20 million inhabitants live within 35 miles of the armistice line. U.S. military officers have cited the fear of a “sea of fire” to justify inaction. But this vulnerability should not paralyze U.S. policy for one simple reason: It is very largely self-inflicted.

When then-U.S. President Jimmy Carter decided to withdraw all U.S. Army troops from South Korea 40 years ago (ultimately a division was left behind), the defense advisors brought in to help — including myself — urged the Korean government to move its ministries and bureaucrats well away from the country’s northern border and to give strong relocation incentives to private companies. South Korea was also told to mandate proper shelters, as in Zurich for example, where every new building must have its own (under bombardment, casualties increase dramatically if people leave their homes to seek shelter). In recent years, moreover, South Korea has had the option of importing, at moderate cost, Iron Dome batteries, which are produced by both Israel and the United States, that would be capable of intercepting 95 percent of North Korean rockets headed to inhabited structures.

But over these past four decades, South Korean governments have done practically nothing along these lines. The 3,257 officially listed “shelters” in the Seoul area are nothing more than underground shopping malls, subway stations, and hotel parking lots without any stocks of food or water, medical kits or gas masks. As for importing Iron Dome batteries, the South Koreans have preferred to spend their money on developing a bomber aimed at Japan.

Even now, casualties could still be drastically reduced by a crash resilience program. This should involve clearing out and hardening with jacks, props, and steel beams the basements of buildings of all sizes; promptly stocking necessities in the 3,257 official shelters and sign-posting them more visibly; and, of course, evacuating as many as possible beforehand (most of the 20 million or so at risk would be quite safe even just 20 miles further to the south). The United States, for its part, should consider adding vigorous counterbattery attacks to any airstrike on North Korea.

Nonetheless, given South Korea’s deliberate inaction over many years, any damage ultimately done to Seoul cannot be allowed to paralyze the United States in the face of immense danger to its own national interests, and to those of its other allies elsewhere in the world. North Korea is already unique in selling its ballistic missiles, to Iran most notably; it’s not difficult to imagine it selling nuclear weapons, too.

Another frequently cited reason for the United States to abstain from an attack — that it would be very difficult to pull off — is even less convincing. The claim is that destroying North Korean nuclear facilities would require many thousands of bombing sorties. But all North Korean nuclear facilities — the known, the probable, and the possible — almost certainly add up to less than fewer dozen installations, most of them quite small. Under no reasonable military plan would destroying those facilities demand thousands of airstrikes.

Unfortunately, this would not be the first time that U.S. military planning proved unreasonable. The United States Air Force habitually rejects one-time strikes, insisting instead on the total “Suppression of Enemy Air Defenses.” This is a peculiar conceit whereby every single air-defense radar, surface-to-air missile, airstrip, and combat aircraft in a given country must be bombed to destruction to safeguard U.S. pilots from any danger, instead of just bombing the targets that actually matter. Given that North Korea’s radars, missiles, and aircraft are badly outdated, with their antique electronics long since countermeasured, the Air Force’s requirements are nothing but an excuse for inaction. Yes, a more limited air attack might miss a wheelbarrow or two, but North Korea has no nuclear-warhead mobile missile launchers to miss — not yet.

Perhaps the only good reason to hesitate before ordering an attack on North Korea is China.

Perhaps the only good reason to hesitate before ordering an attack on North Korea is China.But that’s not because Beijing would intervene against the United States. The notion that China is North Korea’s all-around protector is badly out of date. Yes, the Chinese do not want to see North Korea disappear with U.S. troops moving up to the Yalu River and China’s border. But President Xi Jinping’s support for maximum economic sanctions, including a de facto blockade of oil imports — a classic act of war — amounts to a change of sides when it comes to North Korean nuclear weapons. Anybody who believes China would act on North Korea’s behalf in the event of an American attack against its nuclear installations has not been paying attention.

But China’s shift has surfaced a quite different reason for the United States not to bomb: While North Korea’s acquisition of nuclear weapons is of course very dangerous, it does ensure its independence from Chinese influence. In a post-strike scenario, the Pyongyang regime might well crumble, with the country becoming a Chinese ward. That could give Beijing dominant influence over South Korea as well, given the preference of some South Koreans — including President Moon Jae-in, according to reports — for Chinese as opposed to American patronage. A China-dominated Korean Peninsula would make Japan less secure and the United States much less of a Pacific power.

In theory, a post-attack North Korea in chaos could be rescued by the political unification of the peninsula, with the United States assuaging Chinese concerns by promptly moving its troops further south, instead of moving them north. In practice, however, this would be a difficult plan to carry out, not least because South Korea’s government and its population are generally unwilling to share their prosperity with the miserably poor northerners, as the West Germans once did with their East German compatriots.

For now, it seems clear that U.S. military authorities have foreclosed a pre-emptive military option. But the United States could still spare the world the vast dangers of a North Korea with nuclear-armed long-range missiles if it acts in the remaining months before they become operational.

It’s true that India, Israel, and Pakistan all have those weapons, with no catastrophic consequences so far. But each has proven its reliability in ways that North Korea has not. Their embassies, for instance, don’t sell hard drugs or traffic in forged banknotes. More pertinently, those other countries have gone through severe crises, and even fought wars, without ever mentioning nuclear weapons, let alone threatening their use as Kim Jong Un already has. North Korea is different, and U.S. policy should recognize that reality before it is too late.

Edward Luttwak is a senior associate at the Center for Strategic and International Studies and the author of Strategy: The Logic of War and Peace.

↧

India’s dire contemporary challenges -- Gautam Sen

India’s dire contemporary challenges

The significant positive outcome of a retreat of state patronage, as the dynamic in society, will be the creation of a more autonomous citizen. Such a citizen’s future will be less dependent on engaging with the goodwill of a corruptible state system.Featured Image: (Plan for Amaravati, Andhra Pradesh) The Hindu

09-01-2018

t seems difficult for observers to abstract from the immediate hurly burly of daily political life and the fascination it evokes to focus on complex long-term processes of historic significance that occur periodically in polities.

Contemporary India is an apt example of this predicament, with the unfortunate tendency of commentators preoccupied with the immediate obscuring vital issues that are unfolding. Indeed such perplexed incomprehension even hinders policy makers from making thoughtful inferences of the dilemmas they are encountering. They too get waylaid by the instant TRP obsessions of the media and intellectually limited observers. There is a real failure to perceive that contemporary India is experiencing a historic systemic transformation, hugely consequential for its ordinary citizens and elites.

India today is undergoing a two-fold transformation that cannot but prove difficult for many and painful for some. The justifiable glee over the repossession of Lutyens bungalows, illegally occupied by beneficiaries of unjust patronage, is only of superficial moment. Similarly, the end of the unwholesome bonhomie between the prime minister and the media during his visits abroad is welcome but only hints at a larger phenomenon of transformation. Many other changes, from the withdrawal of indiscriminate and hugely expensive security details for all and sundry to enforcing disciplined attendance at work, are symptoms of a much deeper process at work. And a fortuitous accident of fate has created in Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the vehicle for implementing this far-reaching underlying change and the profound socioeconomic and political phenomenon that it implies.

What is actually occurring in India is the decisive curtailment of a system of state patronage with very long historical roots. It is also alluding to the rise of a more meritocratic order that threatens to undermine established hierarchies, stabilised by privileges of birth, which an impatient urbanising India is challenging. Some of the protest over caste reservations in Gujarat, Rajasthan and elsewhere is an aspect of the discontent unwilling to accept an order that has produced privileged new elites under the guise of social justice. The contemporary contours of the system of state patronage and privileges of birth may have been shaped after independence, but its socio-cultural antecedents are much older. Indeed it has dominated the Indian polity since the rise of Muslim power in India. And it endured in a modified form during British rule, when special preferment was extended to native collaborators who aided the continuance and operation of colonial rule.

Of course state patronage and associated privileges are always present in any polity, but likely to become the dominant mode of governance and social reproduction during foreign occupation because collaborators are created by extending special privileges. It also acquires prominence when the polity and society are unduly fractured and difficult to govern as a collectivity and the state authority remains vulnerable to disorder emanating from below. This is a situation vulnerable to patronage and compromises, designed to bind the polity together, however dysfunctional the result in the aggregate, which Indian reality highlights. Of course ideology and policy choices, like expanding employment within a public sector, can reinforce patronage as a method of manipulation, which also happened in independent India. Yet the inevitable paradox is that demographic and accompanying societal change will provoke tensions over state patronage, with the state unable to accommodate large numbers of newer claimants excluded from its pre-existing networks of privilege.

In India, there has since independence been an unceasing struggle between state patronage as a mode of governance and the dynamics of civil autonomy, particularly refracted through market relations, i.e. how the economy is organised and functions. The faltering of the economy and necessary outcomes to prevent a downward spiral of competition between claimants for shares of static resources prompted greater play being allowed to markets that empowered civil society as a result. The empowering of civil society in this context results in less dependence on state patronage and privileges to operate and succeed. It also creates space for meritocratic primacy though its operation in Indian society remains constrained by legal inhibitions of reservation policy to remedy historic inequities. But India’s constraints on meritocracy are a matter of degree. The private marketplace is outside the domain of reservation policies and merit and performance play a much greater role in dictating individual advancement in it. It goes without saying that the retreat of state patronage does not imply an irrelevance of regulatory intervention by it to ensure efficient and equitable functioning of markets that cannot in fact operate in conditions approximating to a fictive state of nature.

The significant positive outcome of a retreat of state patronage, as the dynamic in society, will be the creation of a more autonomous citizen. Such a citizen’s future will be less dependent on engaging with the goodwill of a corruptible state system. And it will reduce the automatic imputation of outcomes and failures to the state, making governance of the polity a less fraught task. A society that is less politicised on numerous axes also has a better chance of achieving greater social harmony and creating more unity of purpose. But the transition from a society in which state patronage dominates to one in which civil society attains greater autonomy also precipitates instability and conflict. The process creates losers and winners and the former suffer greater setback than winners. The winners may be more numerous, but gain modestly as individuals and will not be motivated to exert themselves overly in favour of the transition. By contrast, the losers, as erstwhile wielders of political, socioeconomic power and authority, are in a position to fight hard to retain the privileges they enjoyed under state patronage.

It is this situation of a deadly domestic contest that India under Narendra Modi is encountering and finding difficult to adequately address. A collateral aspect of this struggle is the contemporaneous international dimension associated with the transformational retreat of state patronage in India. The local domestic resistance to change becomes entangled with the international. Domestic opponents of the transition from state patronage will use all means at their disposal to thwart the ensuing transformation and international adversaries of India will combine with Indian domestic discontent to achieve parochial national goals in relation to the emerging resurgent India. And this phenomenon has been laid bare by recent political upheaval in India. What is increasingly visible is that the erstwhile leading political class, advised by foreign agencies connected to governments and local assets of India’s adversaries, Naxalites and the Jihadi elements, are acting in concert to provoke disorder.

The incumbent elites, political class and bureaucracy and the vast retinue that benefited under state patronage, is understandably aggrieved and unwilling to give up their privileged status, in favour of some putative higher purpose. From bureaucrats, furious at the curtailment of bribery income that funded their handsome life styles, to the previously dominant political class itself resisting and reversing the juggernaut of change is virtually a matter of life-and-death. Having failed to thwart Narendra Modi at the polls since the emergent new India has also created a growing constituency favouring the imperfect transformation to end state patronage that has begun haltingly, a more radical strategy of disruption to stop his programme change is being adopted. If that also fails, the assassination of Narendra Modi, on whom the end of the era of state patronage apparently depends, becomes a real threat since many in the BJP would also prefer a quiet life by making a deal with beneficiaries of the status quo.

In the meantime, the age-old subterfuge of rulers, always so effective in India, is to identify and inflame extant or dormant societal fissures and fault lines. Caste and religious identity are the most promising of these and signs that they were being overlaid by newer concerns of Indians everywhere, with governance and economic aspirations, have prompted an urgency to arouse animosities latent in both. There is a regional and linguistic dimension lurking as well that is evident in the renewed attempt to prompt dissensions over language and region, in Karnataka and, in recent days, between West Bengal and Assam over illegal migrants, whom the CM of West Bengal has chosen to champion. One mundane aspect of the gross provocations being sponsored by the Congress party and its allies is the ease with which alleged leaders can be created, bought and patronised to instigate social chaos through violence. One critical dimension of the situation is the hope that relatively modest instances of street violence can be turned into major conflagration of damaging proportions if the authorities make an ill judged response, as occurred in the 1980s Punjab.

The experience of the Punjab during the 1980s also highlights a salutary lesson about the ability of India’s foreign adversaries to interfere in such crises, indeed play a role in instigating them. The key external players, each for their own reasons, are the Sino-Pak alliance and of course the historic foe of Hinduism, the church, infinitely duplicitous and matchless in its sophistication for skulduggery. In the case of the former, especially Pakistan, derailing India’s economic advance that threatens to relegate it and its ambitions to a minor footnote in history, is now an imperative. In this project Pakistan has the solicitous assistance of China though the latter outwardly dismisses India as an economic competitor, viewing it through the prism of its ancient racial prejudices, now deepened by its own extraordinary economic advance. But the church, despite all its manifold internal schisms and conflicting identities, remains the primary origin of bottomless enmity towards the civilisation of Indica. Discreetly rejoicing at the decisive extirpation of its historic enemy of Jewry the church is hoping to disempower and destroy Brahmins, the source of the detested remaining coherent intellectual challenge to the primacy of its world-view, underpinning ascendancy of people of European racial ancestry.

The desperation of ruling parties like Congress, communists and other episodic political actors, sponsored from abroad, threatened with termination is understandable. Their willingness to collaborate with external subversion to survive, although it would also grievously injure their own country as a result, is unsurprising and happens routinely elsewhere in the world too. With an existential threat to their entire way of life, sources of sustenance and social status, many Indian political parties are seeking help from adversaries of India for whom creating chaos and territorial losses are the principal goals. The fate of the Middle East and in fact the USSR as well after 1990 is an illustration of the dangers, with the US and its NATO allies wreaking permanent devastation on these regions. Foreign intervention to assist political forces resisting India’s transformation from a system of state patronage to a high performing economy and unified society takes many subtle and obvious forms. The acquisition of important stakes in the Indian media by Christian fronts is but one important example of blatant intervention to impact local political outcomes.

The most important external agencies active in creating disorder are the myriad surrogates of the Sino-Pakistani alliance and evangelists. The latter, in conjunction with Washington, has embedded itself in Indian society especially since 1999 with a degree of durability from which it is problematic for India to extricate itself. It is now clear that Manmohan Singh was chosen as PM by Washington and there is eerie indication of Union Cabinet ministers, some of them clandestine religious converts, being nominated by evangelist organisations in conjunction with the US government. The idea that Indian journalists, of no particular standing except high exposure on television channels and as op-ed columnists and some minor fixers like Niira Radia, were recommending candidates for ministerial office to the prime minister on their own initiative alone is unsustainable. They were essentially fronts for significant external agents. In any case, the Sino-Pakistani alliance also directly controls entire political movements and one of the most prominent in UP assisted terrorists in 2005, according to a senior RAW functionary.

India is massively infiltrated by external foes and many Indians abroad have been suborned by agencies of the countries where they reside. Virtually all social scientists and humanities academics abroad are ideologically hostile to India. The hostility stems from profound cultural and personal socialisation, which is not based on some claim to ethical concerns and intellectual cognition, but entirely hollow. One can hardly take virtually anything they posit seriously, echoing as it does the motivated op-ed columns associated with government agencies. But the real explanation for the illogical and bizarre views some of the most prominent regularly express is more mundane. They are often agents of foreign governments or victims of blackmail, as recent exposure for sexual peccadilloes by a host of them in US universities highlights. The recent attempt by hundreds of Indian-origin academics in the most hallowed portals of international academia to subvert India’s engagement with Silicon Valley to achieve its mission to digitise is but one example of their perversity and willingness to cause harm to their country of birth. And it is shocking to observe some of these individuals enjoy extraordinary access to the most senior politicians and bureaucrats in India.

The future of India currently hangs in the balance, with established parties fearing political oblivion in the 2019 general elections, effectively declaring war. Their willingness to countenance civil war by provoking caste and communal violence, in association with foreign agencies, is an indication of the climactic moment India has reached. Congress leader Mani Shankar Aiyar inviting Pakistani help to thwart Prime Minister Modi likely lacks substantive connotation, but has enormous symbolic significance. Hinting as it does on the removal of the elected Prime Minister of the country it underlines a huge danger for India. An attempt to assassinate of the Prime Minister remains an ominous threat that must be taken seriously. It will plunge the country into civil war, exactly as its sworn enemies, China and Pakistan hope and cause huge setback to the promise of national economic advance and greater social harmony. The evangelists take a long-term view and would regard chaos in India as an opportunity for a massive wave of conversions, a scenario they have taken advantage of during Nepal’s civil war, converting a third of the population. The failure of the Indian state to grasp the nature of the threat and its uncertain response to it should alarm its supporters.

Dr. Gautam Sen is President, World Association of Hindu Academicians and Co-director of the Dharmic Ideas and Policy Foundation. He taught international political economy at the London School of Economics and Political Science for over two decades.

What is actually occurring in India is the decisive curtailment of a system of state patronage with very long historical roots. It is also alluding to the rise of a more meritocratic order that threatens to undermine established hierarchies, stabilised by privileges of birth, which an impatient urbanising India is challenging. Some of the protest over caste reservations in Gujarat, Rajasthan and elsewhere is an aspect of the discontent unwilling to accept an order that has produced privileged new elites under the guise of social justice. The contemporary contours of the system of state patronage and privileges of birth may have been shaped after independence, but its socio-cultural antecedents are much older. Indeed it has dominated the Indian polity since the rise of Muslim power in India. And it endured in a modified form during British rule, when special preferment was extended to native collaborators who aided the continuance and operation of colonial rule.

Of course state patronage and associated privileges are always present in any polity, but likely to become the dominant mode of governance and social reproduction during foreign occupation because collaborators are created by extending special privileges. It also acquires prominence when the polity and society are unduly fractured and difficult to govern as a collectivity and the state authority remains vulnerable to disorder emanating from below. This is a situation vulnerable to patronage and compromises, designed to bind the polity together, however dysfunctional the result in the aggregate, which Indian reality highlights. Of course ideology and policy choices, like expanding employment within a public sector, can reinforce patronage as a method of manipulation, which also happened in independent India. Yet the inevitable paradox is that demographic and accompanying societal change will provoke tensions over state patronage, with the state unable to accommodate large numbers of newer claimants excluded from its pre-existing networks of privilege.

In India, there has since independence been an unceasing struggle between state patronage as a mode of governance and the dynamics of civil autonomy, particularly refracted through market relations, i.e. how the economy is organised and functions. The faltering of the economy and necessary outcomes to prevent a downward spiral of competition between claimants for shares of static resources prompted greater play being allowed to markets that empowered civil society as a result. The empowering of civil society in this context results in less dependence on state patronage and privileges to operate and succeed. It also creates space for meritocratic primacy though its operation in Indian society remains constrained by legal inhibitions of reservation policy to remedy historic inequities. But India’s constraints on meritocracy are a matter of degree. The private marketplace is outside the domain of reservation policies and merit and performance play a much greater role in dictating individual advancement in it. It goes without saying that the retreat of state patronage does not imply an irrelevance of regulatory intervention by it to ensure efficient and equitable functioning of markets that cannot in fact operate in conditions approximating to a fictive state of nature.

The significant positive outcome of a retreat of state patronage, as the dynamic in society, will be the creation of a more autonomous citizen. Such a citizen’s future will be less dependent on engaging with the goodwill of a corruptible state system. And it will reduce the automatic imputation of outcomes and failures to the state, making governance of the polity a less fraught task. A society that is less politicised on numerous axes also has a better chance of achieving greater social harmony and creating more unity of purpose. But the transition from a society in which state patronage dominates to one in which civil society attains greater autonomy also precipitates instability and conflict. The process creates losers and winners and the former suffer greater setback than winners. The winners may be more numerous, but gain modestly as individuals and will not be motivated to exert themselves overly in favour of the transition. By contrast, the losers, as erstwhile wielders of political, socioeconomic power and authority, are in a position to fight hard to retain the privileges they enjoyed under state patronage.

It is this situation of a deadly domestic contest that India under Narendra Modi is encountering and finding difficult to adequately address. A collateral aspect of this struggle is the contemporaneous international dimension associated with the transformational retreat of state patronage in India. The local domestic resistance to change becomes entangled with the international. Domestic opponents of the transition from state patronage will use all means at their disposal to thwart the ensuing transformation and international adversaries of India will combine with Indian domestic discontent to achieve parochial national goals in relation to the emerging resurgent India. And this phenomenon has been laid bare by recent political upheaval in India. What is increasingly visible is that the erstwhile leading political class, advised by foreign agencies connected to governments and local assets of India’s adversaries, Naxalites and the Jihadi elements, are acting in concert to provoke disorder.

The incumbent elites, political class and bureaucracy and the vast retinue that benefited under state patronage, is understandably aggrieved and unwilling to give up their privileged status, in favour of some putative higher purpose. From bureaucrats, furious at the curtailment of bribery income that funded their handsome life styles, to the previously dominant political class itself resisting and reversing the juggernaut of change is virtually a matter of life-and-death. Having failed to thwart Narendra Modi at the polls since the emergent new India has also created a growing constituency favouring the imperfect transformation to end state patronage that has begun haltingly, a more radical strategy of disruption to stop his programme change is being adopted. If that also fails, the assassination of Narendra Modi, on whom the end of the era of state patronage apparently depends, becomes a real threat since many in the BJP would also prefer a quiet life by making a deal with beneficiaries of the status quo.

In the meantime, the age-old subterfuge of rulers, always so effective in India, is to identify and inflame extant or dormant societal fissures and fault lines. Caste and religious identity are the most promising of these and signs that they were being overlaid by newer concerns of Indians everywhere, with governance and economic aspirations, have prompted an urgency to arouse animosities latent in both. There is a regional and linguistic dimension lurking as well that is evident in the renewed attempt to prompt dissensions over language and region, in Karnataka and, in recent days, between West Bengal and Assam over illegal migrants, whom the CM of West Bengal has chosen to champion. One mundane aspect of the gross provocations being sponsored by the Congress party and its allies is the ease with which alleged leaders can be created, bought and patronised to instigate social chaos through violence. One critical dimension of the situation is the hope that relatively modest instances of street violence can be turned into major conflagration of damaging proportions if the authorities make an ill judged response, as occurred in the 1980s Punjab.

The experience of the Punjab during the 1980s also highlights a salutary lesson about the ability of India’s foreign adversaries to interfere in such crises, indeed play a role in instigating them. The key external players, each for their own reasons, are the Sino-Pak alliance and of course the historic foe of Hinduism, the church, infinitely duplicitous and matchless in its sophistication for skulduggery. In the case of the former, especially Pakistan, derailing India’s economic advance that threatens to relegate it and its ambitions to a minor footnote in history, is now an imperative. In this project Pakistan has the solicitous assistance of China though the latter outwardly dismisses India as an economic competitor, viewing it through the prism of its ancient racial prejudices, now deepened by its own extraordinary economic advance. But the church, despite all its manifold internal schisms and conflicting identities, remains the primary origin of bottomless enmity towards the civilisation of Indica. Discreetly rejoicing at the decisive extirpation of its historic enemy of Jewry the church is hoping to disempower and destroy Brahmins, the source of the detested remaining coherent intellectual challenge to the primacy of its world-view, underpinning ascendancy of people of European racial ancestry.

The desperation of ruling parties like Congress, communists and other episodic political actors, sponsored from abroad, threatened with termination is understandable. Their willingness to collaborate with external subversion to survive, although it would also grievously injure their own country as a result, is unsurprising and happens routinely elsewhere in the world too. With an existential threat to their entire way of life, sources of sustenance and social status, many Indian political parties are seeking help from adversaries of India for whom creating chaos and territorial losses are the principal goals. The fate of the Middle East and in fact the USSR as well after 1990 is an illustration of the dangers, with the US and its NATO allies wreaking permanent devastation on these regions. Foreign intervention to assist political forces resisting India’s transformation from a system of state patronage to a high performing economy and unified society takes many subtle and obvious forms. The acquisition of important stakes in the Indian media by Christian fronts is but one important example of blatant intervention to impact local political outcomes.

The most important external agencies active in creating disorder are the myriad surrogates of the Sino-Pakistani alliance and evangelists. The latter, in conjunction with Washington, has embedded itself in Indian society especially since 1999 with a degree of durability from which it is problematic for India to extricate itself. It is now clear that Manmohan Singh was chosen as PM by Washington and there is eerie indication of Union Cabinet ministers, some of them clandestine religious converts, being nominated by evangelist organisations in conjunction with the US government. The idea that Indian journalists, of no particular standing except high exposure on television channels and as op-ed columnists and some minor fixers like Niira Radia, were recommending candidates for ministerial office to the prime minister on their own initiative alone is unsustainable. They were essentially fronts for significant external agents. In any case, the Sino-Pakistani alliance also directly controls entire political movements and one of the most prominent in UP assisted terrorists in 2005, according to a senior RAW functionary.

India is massively infiltrated by external foes and many Indians abroad have been suborned by agencies of the countries where they reside. Virtually all social scientists and humanities academics abroad are ideologically hostile to India. The hostility stems from profound cultural and personal socialisation, which is not based on some claim to ethical concerns and intellectual cognition, but entirely hollow. One can hardly take virtually anything they posit seriously, echoing as it does the motivated op-ed columns associated with government agencies. But the real explanation for the illogical and bizarre views some of the most prominent regularly express is more mundane. They are often agents of foreign governments or victims of blackmail, as recent exposure for sexual peccadilloes by a host of them in US universities highlights. The recent attempt by hundreds of Indian-origin academics in the most hallowed portals of international academia to subvert India’s engagement with Silicon Valley to achieve its mission to digitise is but one example of their perversity and willingness to cause harm to their country of birth. And it is shocking to observe some of these individuals enjoy extraordinary access to the most senior politicians and bureaucrats in India.

The future of India currently hangs in the balance, with established parties fearing political oblivion in the 2019 general elections, effectively declaring war. Their willingness to countenance civil war by provoking caste and communal violence, in association with foreign agencies, is an indication of the climactic moment India has reached. Congress leader Mani Shankar Aiyar inviting Pakistani help to thwart Prime Minister Modi likely lacks substantive connotation, but has enormous symbolic significance. Hinting as it does on the removal of the elected Prime Minister of the country it underlines a huge danger for India. An attempt to assassinate of the Prime Minister remains an ominous threat that must be taken seriously. It will plunge the country into civil war, exactly as its sworn enemies, China and Pakistan hope and cause huge setback to the promise of national economic advance and greater social harmony. The evangelists take a long-term view and would regard chaos in India as an opportunity for a massive wave of conversions, a scenario they have taken advantage of during Nepal’s civil war, converting a third of the population. The failure of the Indian state to grasp the nature of the threat and its uncertain response to it should alarm its supporters.

http://indiafacts.org/india-dire-contemporary-challenges/

↧

Visiting Natyashastra in the Ancient Paramparaa: A Vyaakhyaa by Prof Bharat Gupt -- Rashma Kalsie

Visiting Natyashastra in the Ancient Paramparaa: A Vyaakhyaa by Prof Bharat Gupt

Unlike today the audience of ancient India was not fragmented and art was accessible to everyone. There was no rural-urban divide, the same plays were enjoyed by the elite and the common man. In fact, Natya bridged the distance between the rulers and the ordinary citizens.Bharata Muni had given India it unified aesthetics theory some 2,500 years ago. The Natyashastra had laid down common principles of aesthetics for all arts. The principles for making an aesthetically pleasing spoon could be applied to drama and vice versa. The tenets of Natyashastra were equally relevant to the useful arts and the fine arts. Unfortunately this great text is now limited to conferences and a small academic circle.

An idyllic setting in Ramgarh in Uttarkhand where Prof Gupt conducted a traditional style vyaakhayaa on Natyashastra

It was impossible to discuss all the 6,000 kaarikaas given in the 36 chapters of Natyashastra in the given time of 7 days in thirty hours, therefore only the essential kaarikaas were discussed in detail. Kaarikaa is a shloka that executes meaning. For starters Prof Gupt demolished the major controversy around the date of Natyashastra. He cited evidence to prove Natyashastra was written in the fifth century BC, and not the second century AD as claimed by the Western scholars. The most crucial evidence being that Bharata Muni lived before Panini, the Sanskrit grammarian, who is estimated to have lived around 520 BC. Further, sage Valmiki has used Natyashastra’s vocabulary in Ramayana, which proves that Bharata Muni existed at a time before Valmiki. The dating of Natyashastra is significant because it implies that Aristotle’s Poetics was written at a much later date compared to Natyashastra. In which case, there’s a possibility that Aristotle borrowed from Natyashastra and not vice versa. Unlike Poetics, Natyashastra was not written by one person. Indian texts were written by a group of scholars over a long period of time. Bharata Muni had compiled it from earlier texts and his hundred disciples expanded the Natyashastra.

The story of the origin of Natyashastra is just as interesting. The legend goes that in the Treta yuga, when sattva was declining and there was a mix of happiness and unhappiness, Indra asked Brahma to create a ‘play’ or activity to please the mind through the aural and the visual senses. Also, the pleasure that Indra was seeking was not the sensory pleasure, but a pleasure of the elevated kind. Indra emphasized the need for knowledge for the illiterate persons who had no knowledge of the Vedas.

Hence, Lord Brahma created the Natyaveda and instructed Bharata Muni to create the Natyashastra for the art of natya or theatre. Bharata Muni borrowed the text or ‘path’ from Rig Veda, music from Sam Veda, abhinaya from Yajur Veda and the concept of rasa from Ayurveda. Prof Gupt expanded on the relationship between Ayurveda and natya. He said natya acts as a medicine and restores balance in the human body. It brings you back to a state of emotional balance which was distorted due to worldly tribulations. It should be noted that Natya had an elevated status in ancient India.

Amrtamanthan, the first play created and staged by Bharata Muni, has also been a subject of controversy. The play and its theme have been wrongly interpreted by the scholars as a fight between the Aryan and the Dravidian races. Prof Gupt is of the view that the conflict between the devas and the asuras should be seen as the conflict of values and not interpreted in historic and anthropological terms.

One by one all the conflicts around Natyashastra were taken up and resolved. Talking of the theater halls, Prof Gupt said, that on the one hand there is detailed description of natyagrihas/theater halls, but on the other we find no archaeological remains of the theater halls. In contrast, remains of Greek theaters can be found not only in Greece but also as far as Afghanistan. Prof Gupt explained that the natyagrihas were temporary structures and were dismantled at the end of the play. Just like there are no remains of the thousands of ancient Yagyasthalas, there are no remains of the natyagrihas. Even stage props were ‘pusta’ or fragile and temporary. Further, he gave the example of the modern-day Hindu Wedding mandap. Even today for every wedding the mandap is erected and dismantled after the wedding.

Unlike today the audience of ancient India was not fragmented and the art was accessible to everyone. There was no rural-urban divide, the same plays were enjoyed by the elite and the common man. In fact, Natya bridged the distance between the rulers and the ordinary citizens. The king or the rich patron along with the residents of the town/village participated in the yagya and the construction of the natyagrah. Hence from the construction of the theater hall to the last day of the performance, theater was a community affair. Theater was funded by the rich patrons, the community and the temples. Theater did not depend on the royal patronage only, hence theater was not liable to censor or follow political correctness. Natya performances happened throughout the year. There were multiple productions in a town. Hence many natyagrihas had to be constructed and there may have been multiple patrons. If we had to conjure the image of ancient India, by the description given in the Natyashastra, it would appear to the modern eye as a colourful, festive place that came alive every evening with dance, music and theatrical performances.

Another distinct feature of the ancient Indian theater was the emphasis on gesture, dance and body movement. Prof Gupt emphasized the difference by calling Western theater, ‘the theater of dialogue’. He said in Indian theater, body was the main medium of storytelling. Abhinaya has four parts – aangika (body), vaacika (dialogue), saattvika (emotions) and aaharya (costume). According to the Indian aesthetic theory, verbal language is incapable of depicting the cosmos, hence it is just one of the abhinayas.

What with shrinking attention span, there’s a trend to produce plays with a running time under two hours. Compare the modern trend with the ancient theater where even the prelude to the play was two hours long. Puurvaranga or the prelude had a set sequence of music, dance, singing, prayer and jest. While an elaborate puurvaranga was performed at the start of the play, a short puurvaranga was performed every day. This means a full-length play such as Abhijnanashaakuntalam could not have been performed in one day. Prof Gupt concluded that only one act could have been performed in a day and a seven-act-play would have been performed over eight to ten days.

The interrelation between natya, nrtta and sculpture is a fine example of the unified aesthetics theory in ancient India. Natyashastra talks about pindi bandha, which were part of the puurvaranga.Pindi bandhas were specific postures to depict a devata, for instance samapaada posture depicts Vishnu. Later pindi bandhas became prototype for sculptures and temple icons. Prof Gupt emphasized that all the icons in temples are dance icons and the origin of sculpture is in natyakaranas or Nrtta.

Natyashastra is not limited to theater craft and aesthetic principles. The rasa siddhanta, which is the foundation of the Indian aesthetics theory, goes deep into the psychology of drama and the psyche of the spectator. Rasa siddhanta is unique to Indian aesthetics theory. The literal meaning of rasa is juice. According to Bharata Muni rasa is extracted from the other ten elements of drama. Bharata Muni says there’s no meaning without rasa. Bharata Muni was clear about what was acceptable as art. He says only those arts that are worthy, are rasa vishesh. Not every kind of rasa is suitable for attainment of dharma, artha, kama, and moksha. Hence art that merely entertains, gives lowly pleasure or titillates is not capable of rasa. It gives the impression of rasabhaas– rasa ka abhaas. But it is not socially, mentally healthy. For instance porn. Only that which has asvaadyatva (worthiness of tasting) is rasa.

Bharata Muni has drawn a parallel between drama and food to explain the concept of rasa. He says when an open-minded spectator sees acting which is embellished with different bhavas, gestures and acting, the spectator experiences joy just as a person experiences joy on eating a dish which has been flavoured with spices and condiments. Prof Gupt emphasized the spectator does not create rasa, he is suffused in it.

Prof Gupt was categorical there are only eight rasas in Natyashastra. Some students put forth the ninth rasa, which is referred to as shaanta rasa. Prof Gupt said Bharat Muni did not add shaanta rasa to the list because shaantarasa and its originator sthayibhava (nirveda/vairagya), cannot be enacted in detail on stage.

Closely related to the concept of rasa is vibhaava. Bharata Muni says vibhaava is that which expands the meaning by using the techniques of theater such as abhinaya. The root word for bhava is bhu. If you burn an incense stick, its aroma pervades. This is bhaavayan. Likewise an actor has to pervade the audience. He has to affect the audience. Bharata explains that actor is the vibhaava and he takes up the bhaava and the meaning. Through gestures and acting the audience infers the meaning. These gestures are anubhava. Bhaava (thoughts plus feelings) is carried by vibhaava and deciphered through anubhavas.

Bharata Muni says that just as fire pervades the dry wood and the whole forest starts burning, likewise the intent or the meaning pervades the body of the actor and reaches the spectators and all the spectators are affected. This bhaava expansion is the cause of rasa.

Prof Gupt discussed the commentary of the four great commentators on the rasasutra– Lollata, Sankuka, Bhattanayak, and Abhinavagupta.

Abhinavagupta uses the analogy of the deer chase in Abhijnanashakuntalam to analyze rasasutra. He explains that on seeing the deer chase the spectator feels no anxiety for the deer because there is no earthly reality of what is being seen. Neither the deer, nor the chaser are real. The self of the spectator is neither assertive, nor subdued. Since dramatic emotion is impersonal it is felt in a special way. In drama we can step away from personal. Further Abhinavagupta says, that the experience of a single spectator is influenced by the community of spectators. When the community of spectators is offered the same pratiti, the resultant experience (sadharanikarana) is so strong. This single unifying experience which is deeply felt by the audience is rasa.

Prof Gupt put forth his own analysis of the sutra. He said rasa is not just in transformation of sthaayiibhaavas but in the union of sthaayii with anubhaava, vibhaava, and sanchaarii. The union of vibhaava, anubhaava, and sanchaarii bhavas forces the spectator to forget everything. It is then that the spectator is in total tanmayataa with the natya and this complete union (samyukti) is rasa. Prof Gupt says that rasa is extreme extroversion, going out of yourself to unite with the prayoga.

Last of all, Prof Gupt examined the position of rasa in Marxist theory. He said the followers of Karl Marx believe that rasa is dangerous because it causes escape. To them the purpose of theater is revolution, not escape or aesthetic beauty or rasa.

Coming to the application of rasa siddhaanta to other arts, Prof Gupt explained the principles and definitions of rasa given in Natyashastra will not apply in the same way to other arts and media. There has to be a different grammar and definition for other arts. For instance in a painting the balance of colours results in rasa. Rasa and bliss are synonyms in one sense, but not every sense. Prof Gupt emphasized that rasa is not bound by time. Bharata Muni’s rasa concept is not only for ancient plays, it can be applied to modern plays as well. Notion of beauty may change but the end result or rasa is the same. Most scholars dispute that Aristotle has called ‘Katharsis’ as the purpose of drama. Prof Gupt criticized scholars for having read the Poetics in parts. Because Aristotle has said that we go to watch a play for ‘proper pleasure’. The word for ‘pleasure’ is ‘Hedone’. Katharsis is one of the things that emerges watching tragedy, but not the main thing. ‘Pleasure proper’ to that genre of performance, that is tragedy/comedy/satirikon, is what we seek. Proper pleasure to a tragic play is tragedy and likewise for comedy and satirikon.

Prof Gupt said that looking at all the vyakhyas and analysis we can conclude that pleasure is the primary cause of seeking art.

In the context of rural theater, Prof Gupt remarked that the sophistication of ancient Indian theater has been lost for 900 years. Remnants of traditional drama survive in dance forms like ‘bhavai’ and ‘koodiyatam’ etc. There was a constant flow, travel and exchange of artists and manuscripts between the rural and the urban India. There were educational institutions even in small villages. Theater had multiple patrons and companies toured the production all over the country. Hence rural theater was as sophisticated as city theatre. After Turkish invasion in the 11th century theatre could not be performed in the openly cities as Islamic rulers did not permit it.

Prof Gupt busted the biggest myth around ancient Indian theater. He said Indian theater is wrongly referred to as ‘Sanskrit theater’. Sanskrit was one of the many languages spoken in the ancient plays. The plays were multi-lingual. Only 20 to 30% lines were in Sanskrit. Most characters spoke Praakrta languages like Avanti, Maaghdii, Sharaseni etc. Natyashastra clearly lays down rules for who will speak which language with whom. For instance Devas spoke Ati Bhasha or old Sanskrit, the kings spoke mostly in Sanskrit and illiterate and poor people spoke in Praakrta languages. There is an exhaustive list of people and the languages they would speak in which situation.

Natyashastra deals in every aspect of theater. From toe and eyebrow movements to music to musical instruments to actor’s make up to costumes to character delineation to the director’s job, Natyashastra discusses everything in great detail. It is evident that the ancient drama was a highly sophisticated art form and the audience was well versed with the language of the theater. Looking at Natyashastra we can only imagine the richness of art forms at that time.

http://indiafacts.org/visiting-natyashastra-ancient-paramparaa-vyaakhyaa-prof-bharat-gupt/

↧

↧

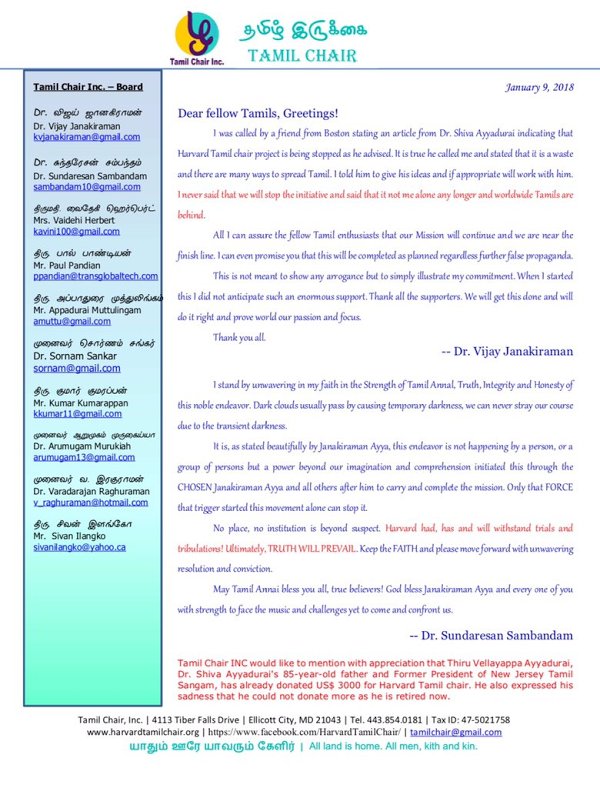

Harvard's Tamil Professorship scam

Dr. Shiva Ayyadurai Stops Harvard’s Tamil Professorship Scam

Dr. Shiva Ayyadurai Stops Harvard’s Selling of Tamil Professorship

Co-Founder of “Harvard Tamil Chair” Agrees to Pull Plug on $6 Million and Concurs with Dr. Ayyadurai That It Was Mistake to Fund Harvard

U.S. Senate Candidate Dr. Shiva Ayyadurai has stopped Harvard University’s attempt to pilfer trillions of dollars worth of indigenous artifacts through the sale of a “Harvard Tamil Chair” professorship. Harvard sought to collect $6 Million from the Tamil diaspora worldwide, who had no idea of Harvard’s business model of selling professorships to fund its $35 Billion hedge fund investments. Tamil is the oldest surviving language with the richest body of poetry, art, and literature known to humankind, along with hundreds of thousands of sacred artifacts codified in palm leaf manuscripts embodying the scientific, technological and medical knowledge spanning at least 5,000 years of the Tamilians, the indigenous people of the Indian subcontinent, who today primarily reside in Tamil Nadu.

![]()

According to Dr. Ayyadurai, “The fundraising effort in the name of setting up a Tamil Chair is a ruse that exemplifies Harvard’s habitual exploitation of indigenous people. This is an egregious example akin to a burglar asking you to pay money to buy a rickety ladder to rob your own home. Harvard is asking Tamilians to pay $6 million for a professorship that will be used to rob their own historic artifacts worth trillions of dollars representing the ‘Holy Grail’ of the world’s most highly-prized indigenous knowledge.” Harvard will then proceed to use access to those artifacts to rewrite and hegemonize Tamil history, an unfortunate and recurrent process that Harvard has done for far too long to many indigenous cultures.

![]()

A Hedge Fund Masquerading as a University

Harvard’s financial statements reveal that the university is fundamentally a tax-exempt Wall Street hedge fund with cash and investments of nearly $35 Billion. In 2016 alone, Harvard’s capital marketing campaign raised $7 Billion, with its hedge fund in 2017 yielding $2 billion in gross profits. The operating budget further reveals that professors and administrators effectively serve as business development staff to attract wealthy donors to fund Chairs and professorships that finance their lucrative hedge fund. In 2017, as the Boston Globe reported, Harvard’s seven top hedge fund managers earned a total of nearly $58 million in compensation.

![]()

Dr. Ayyadurai said, “As these numbers indicate, Harvard is a hedge fund masquerading as a University, which perpetuates this facade by reinvesting large portions of its hedge fund proceeds to unleash propaganda that it is a ‘world-renowned’ institution of higher learning and scholarliness dedicated to advancing humankind. This branding attracts financing from well-meaning folks, compelled to ‘join the club’ so their children get preferential treatment when applying to Harvard and access to Harvard’s insider network. This dynamic is rarely discussed in the mainstream media.” Nearly one-third of the students admitted to Harvard are beneficiaries of a well-documented legacy and preferential admission system that is not merit-based but on “who you know” or who donated money.

![]()

Dr. Ayyadurai’s leadership in opposing the “Harvard Tamil Chair” has led to significant discussions on social media. Questions are being raised about why Harvard exists. Does Harvard exist as a center of research and learning? Or, does Harvard exist to enrich itself through its hedge fund activities? Given the historic value of Tamil, why didn’t Harvard fund Tamil studies with its own $6 million, particularly given that the amount would be a paltry sum (which would be less than one-tenth of one-percent of the $7 billion Harvard raised from its recent 2016 capital campaign)?

Harvard’s Victimization of Indigenous Peoples

Dr. Vijay Janakiraman, the co-founder of the Harvard Tamil Chair effort to raise the $6 million, claimed he was unaware of Harvard’s business practices until his recent phone conversation with Dr. Ayyadurai, who shared with him that Harvard is not only a hedge fund but also an institution that thrives on racism, corruption and exploitation of indigenous people. Dr. Janakiraman admitted he had naively believed that by donating money to Harvard, he was helping in the preservation and dissemination of the Tamil language.

![Elizabeth Warren Pocahontas Victimization of Indigenous People]()

Harvard has a track record of destroying indigenous people’s heritage and culture by seizing control of their property, intellectual and otherwise. In 2011, an exposé revealed that Harvard used its hedge fund cash to take over land in Africa leading to forcible displacement of indigenous farmers. The Harvard Tamil Chair would have offered a gateway for Harvard to exercise control over the rare and ancient palm leaf manuscripts — the intellectual property of the indigenous people of Tamil Nadu. Harvard’s abusive treatment of Dr. Subramanian Swamy further exemplifies how they treat an indigenous Tamil scholar, who was dismissed for challenging Harvard’s party line. In contrast, Harvard uses its hedge fund profits to hire and retain Elizabeth Warren, who has never challenged Harvard’s exploitative practices. In fact, it paid her an exorbitant sum of $350,000 per year for teaching just one course.

The Harvard Office of the President was complicit with Warren, who shoplifted Native American identity in order to not just advance her career but also to benefit Harvard from Federal grants by misleading the government that they had a Native American on their staff. Warren went on to increase her net worth to over $10 million while the average net worth of African-Americans, segregated in Warren’s and Harvard’s own backyard in Cambridge and Boston, spiraled downward, as reported by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, to a meager and unbelievable $8 (“Eight Dollars”).

Dr. Ayyadurai’s timely involvement, fortunately, has been a relief to Tamilians worldwide, who are pleased that Dr. Janakiraman, after listening to Dr. Ayyadurai, decided to stop funding Harvard. Dr. Janakiraman told Dr. Ayyadurai, “You are the expert. Tell me what to do and provide me guidance.”

The Emperor Has No Clothes

Dr. Ayyadurai’s plan involves galvanizing the Tamil population globally to build the first online Tamil University at TamilNadu.com, a media property Dr. Ayyadurai has owned since 1993 and will donate to the cause. The finest Tamil software engineers worldwide are volunteering to build a 21st century digital platform that will deliver the Tamil language to all who seek to learn it, across various skill levels. This approach will be far different than “Harvard Tamil Chair” that would have provided, at best, a rudimentary pre-kindergarten knowledge in Tamil language. The online video of Jonathan Ripley of Harvard University purportedly teaching Tamil language is evidence of this. The vocabulary in his lessons is limited to a few words — yes, no, this, that, what, hand, leg, tooth, stone, bag, and milk — which is nothing more than baby-talk. The TamilNadu.Com platform will further provide universal access to the ancient manuscripts to advance all humanity, in contrast to enabling Harvard’s predatory practices.

![]()

There is also growing evidence that people behind the Harvard effort appear to be Hebrew language chauvinists in academia and their allies who seek to deliberately cover up the preeminence of the Tamil language by ensuring that they control the historical narrative of Tamil and reduce it to some “goo goo ga ga” language. A comparison of the Hebrew script with the Tamil Brahmi script will confirm that Hebrew script is based on the older Brahmi script, an uncomfortable fact for the Hebrew chauvinists who suppress this fact.

Dr. Ayyadurai stated, “Harvard is a predatory institution that leeches of taxpayers and needs to be busted up and returned to the public to serve as a community college, as it was originally intended. Their teaching model is medieval and dead, relying on egomaniacal professors who think they know better than the rest of us. The Department of Justice must investigate the racial and religious composition of Harvard’s faculty to determine if any single group is overrepresented due to its chauvinist hiring practices.”

U.S. Senate Candidate Dr. Shiva Ayyadurai has stopped Harvard University’s attempt to pilfer trillions of dollars worth of indigenous artifacts through the sale of a “Harvard Tamil Chair” professorship. Harvard sought to collect $6 Million from the Tamil diaspora worldwide, who had no idea of Harvard’s business model of selling professorships to fund its $35 Billion hedge fund investments. Tamil is the oldest surviving language with the richest body of poetry, art, and literature known to humankind, along with hundreds of thousands of sacred artifacts codified in palm leaf manuscripts embodying the scientific, technological and medical knowledge spanning at least 5,000 years of the Tamilians, the indigenous people of the Indian subcontinent, who today primarily reside in Tamil Nadu.

According to Dr. Ayyadurai, “The fundraising effort in the name of setting up a Tamil Chair is a ruse that exemplifies Harvard’s habitual exploitation of indigenous people. This is an egregious example akin to a burglar asking you to pay money to buy a rickety ladder to rob your own home. Harvard is asking Tamilians to pay $6 million for a professorship that will be used to rob their own historic artifacts worth trillions of dollars representing the ‘Holy Grail’ of the world’s most highly-prized indigenous knowledge.” Harvard will then proceed to use access to those artifacts to rewrite and hegemonize Tamil history, an unfortunate and recurrent process that Harvard has done for far too long to many indigenous cultures.

A Hedge Fund Masquerading as a University

Harvard’s financial statements reveal that the university is fundamentally a tax-exempt Wall Street hedge fund with cash and investments of nearly $35 Billion. In 2016 alone, Harvard’s capital marketing campaign raised $7 Billion, with its hedge fund in 2017 yielding $2 billion in gross profits. The operating budget further reveals that professors and administrators effectively serve as business development staff to attract wealthy donors to fund Chairs and professorships that finance their lucrative hedge fund. In 2017, as the Boston Globe reported, Harvard’s seven top hedge fund managers earned a total of nearly $58 million in compensation.

Dr. Ayyadurai said, “As these numbers indicate, Harvard is a hedge fund masquerading as a University, which perpetuates this facade by reinvesting large portions of its hedge fund proceeds to unleash propaganda that it is a ‘world-renowned’ institution of higher learning and scholarliness dedicated to advancing humankind. This branding attracts financing from well-meaning folks, compelled to ‘join the club’ so their children get preferential treatment when applying to Harvard and access to Harvard’s insider network. This dynamic is rarely discussed in the mainstream media.” Nearly one-third of the students admitted to Harvard are beneficiaries of a well-documented legacy and preferential admission system that is not merit-based but on “who you know” or who donated money.

Dr. Ayyadurai’s leadership in opposing the “Harvard Tamil Chair” has led to significant discussions on social media. Questions are being raised about why Harvard exists. Does Harvard exist as a center of research and learning? Or, does Harvard exist to enrich itself through its hedge fund activities? Given the historic value of Tamil, why didn’t Harvard fund Tamil studies with its own $6 million, particularly given that the amount would be a paltry sum (which would be less than one-tenth of one-percent of the $7 billion Harvard raised from its recent 2016 capital campaign)?

Harvard’s Victimization of Indigenous Peoples

Dr. Vijay Janakiraman, the co-founder of the Harvard Tamil Chair effort to raise the $6 million, claimed he was unaware of Harvard’s business practices until his recent phone conversation with Dr. Ayyadurai, who shared with him that Harvard is not only a hedge fund but also an institution that thrives on racism, corruption and exploitation of indigenous people. Dr. Janakiraman admitted he had naively believed that by donating money to Harvard, he was helping in the preservation and dissemination of the Tamil language.

Harvard has a track record of destroying indigenous people’s heritage and culture by seizing control of their property, intellectual and otherwise. In 2011, an exposé revealed that Harvard used its hedge fund cash to take over land in Africa leading to forcible displacement of indigenous farmers. The Harvard Tamil Chair would have offered a gateway for Harvard to exercise control over the rare and ancient palm leaf manuscripts — the intellectual property of the indigenous people of Tamil Nadu. Harvard’s abusive treatment of Dr. Subramanian Swamy further exemplifies how they treat an indigenous Tamil scholar, who was dismissed for challenging Harvard’s party line. In contrast, Harvard uses its hedge fund profits to hire and retain Elizabeth Warren, who has never challenged Harvard’s exploitative practices. In fact, it paid her an exorbitant sum of $350,000 per year for teaching just one course.

The Harvard Office of the President was complicit with Warren, who shoplifted Native American identity in order to not just advance her career but also to benefit Harvard from Federal grants by misleading the government that they had a Native American on their staff. Warren went on to increase her net worth to over $10 million while the average net worth of African-Americans, segregated in Warren’s and Harvard’s own backyard in Cambridge and Boston, spiraled downward, as reported by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, to a meager and unbelievable $8 (“Eight Dollars”).

Dr. Ayyadurai’s timely involvement, fortunately, has been a relief to Tamilians worldwide, who are pleased that Dr. Janakiraman, after listening to Dr. Ayyadurai, decided to stop funding Harvard. Dr. Janakiraman told Dr. Ayyadurai, “You are the expert. Tell me what to do and provide me guidance.”

The Emperor Has No Clothes