This blogpost is prompted by an exquisite monograph, 'Written language vs. non-linguistic symbol systems' by Richard Sproat http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/05/written-language-vs-non-linguistic.html The monograph cited in this URL makes an assumption that symbols used on many examples of Indus writing were pre-literate and did not constitute a 'writing' system. It should be noted that the thesis presented fails to analyse the context in which Indus writing was deployed -- the context of the bronze-age which saw the revolutionary advances in metallurgy of copper + tin bronzes replacing naturally-occurring arsenic bronzes. Just one shape of a token to connote 'metal' was NOT adequate to convey messages about the products emerging out of the bronze-age technologies of alloying.

Clay tokens from Susa, a city site in Iran, are seen in the composite photograph on the opposite page. The tokens, in the collection of the Musée du Louvre, are about 5,000 years old. The five tokens in the top row represent some of the commonest shapes: a sphere, a half-sphere, a disk, a cone and a tetrahedron. The more elaborate tokens in the next row have been marked with incisions or impressions. Unperforated and perforated versions of similar tokens appear in the third and fourth rows. Tokens in the bottom two rows vary in shape and marking; some can be equated with early Sumerian ideographs

Clay tokens from Susa, a city site in Iran, are seen in the composite photograph on the opposite page. The tokens, in the collection of the Musée du Louvre, are about 5,000 years old. The five tokens in the top row represent some of the commonest shapes: a sphere, a half-sphere, a disk, a cone and a tetrahedron. The more elaborate tokens in the next row have been marked with incisions or impressions. Unperforated and perforated versions of similar tokens appear in the third and fourth rows. Tokens in the bottom two rows vary in shape and marking; some can be equated with early Sumerian ideographs Clay Tokens a la Schmandt-Besserat

The early system of counting numbers of categorised goods and use of specific token shapes related to a specific commodity is well attested in the system of bullae and clay tokens from the days of Sumer. Tokens of different geometric shapes connoted different commodities and the count of the commodities was indicated by markings on the tokens. An evolution was the envelope (bulla) to hold the tokens as in a rattle. Wedge was a graphic form and became a component of the cuneiform writing system. See: Denise Schmandt-Besserat, 1977, The earliest precur of writing, Scientific American. June 1977, Vol. 238, No. 6, p. 50-58 http://en.finaly.org/index.php/The_earliest_precursor_of_writingI have demonstrated that Indus writing evolved from the system of tokens as the bronze age products were so large in number that new shapes could not be invented for the tokens to distinguish varieties of minerals, metals, alloys and products of the metal alloys such as ingots, hammers, sickles, knives, ploughshare and so on. HARP (Harappa archaeological project) had shown how tablets were used on workers' platforms. I have shown that these tablets recorded work-in-progress before the final consolitation of the information contained on tablets on to seals which could accompany the consignments of goods like bills of lading.

Assuming that a writing system is defined as a system based on underlying human sounds of language, it can be demonstrated that such symbols did in fact have an underlying basis of words from Meluhha (mleccha) of Indian sprachbund.

The key to answer the assumptions underlying Richard's thesis is to outline an evolution of the system of tokens and bullae into a hieroglyphic writing system, using glyphs to connote words, in a logo-semantic method reading the words rebus to connote similar sounding words denoting the commodities of the bronze-age.

Geographical distribution of tokens extends from as far north as the Caspian border of Iran to as far south as Khartoum and from Asia Minor eastward to the Indus Valley.

Geographical distribution of tokens extends from as far north as the Caspian border of Iran to as far south as Khartoum and from Asia Minor eastward to the Indus Valley.  Fifty-two tokens, representative of 12 major categories of token types, have been matched here with incised characters that appear in the earliest Sumerian inscriptions. Most of the inscriptions cannot be read. Here, if the meaning of the symbol is known, the equivalent word in English appears. The Sumerian numerical symbols equated with the various spherical and conical tokens are actual impressions in the surface of the tablet. In two instances (sphere) incised lines are added; in a third (cone) a circular punch mark is added.

Fifty-two tokens, representative of 12 major categories of token types, have been matched here with incised characters that appear in the earliest Sumerian inscriptions. Most of the inscriptions cannot be read. Here, if the meaning of the symbol is known, the equivalent word in English appears. The Sumerian numerical symbols equated with the various spherical and conical tokens are actual impressions in the surface of the tablet. In two instances (sphere) incised lines are added; in a third (cone) a circular punch mark is added. Harappa fish-shaped tablet with Indus writing. Fish is a hieroglyph connoting ayo, ayas 'metal' AND IS NOT fish as a commodity to be accounted for in food rations. This reading is consistent with the entire set of Indus writing corpora as metalware catalogs.

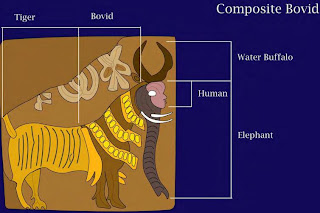

Harappa fish-shaped tablet with Indus writing. Fish is a hieroglyph connoting ayo, ayas 'metal' AND IS NOT fish as a commodity to be accounted for in food rations. This reading is consistent with the entire set of Indus writing corpora as metalware catalogs.A dramatic advancement in metal alloying was matched by the technique of ligaturing of hieroglyphs in the writing system. This is exemplified by the composite hieroglyph of what is referred to as a composite animal and components analysed by Huntington.

A ligature of two hieroglyphs: 1. mountain; 2. leaf. kōṭu summit of a hill, peak, mountain; rebus: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge.

A ligature of two hieroglyphs: 1. mountain; 2. leaf. kōṭu summit of a hill, peak, mountain; rebus: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge.kamaṛkom 'petiole of leaf'; rebus: kampaṭṭam 'mint'.

Another characteristic ligature of hieroglyphs: 1. fish; 2. crocodile (alligator) on one side of a prism tablet MD-602. ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (fish, aya+ crocodile, karā). There are Indus writing examples which show a 'trough' glyph placed in front of even wild animals such as a tiger or a rhinoceros. Is it unreasonable to assume that this is a hieroglyphic narrative read rebus rather than some imagined 'mythical story' or 'symbols of valor or heraldry'?

Another characteristic ligature of hieroglyphs: 1. fish; 2. crocodile (alligator) on one side of a prism tablet MD-602. ayakāra ‘ironsmith’ (fish, aya+ crocodile, karā). There are Indus writing examples which show a 'trough' glyph placed in front of even wild animals such as a tiger or a rhinoceros. Is it unreasonable to assume that this is a hieroglyphic narrative read rebus rather than some imagined 'mythical story' or 'symbols of valor or heraldry'? Components of the composite hieroglyph on seal M-299. A ligaturing element is a human face which is a hieroglyph read rebus in mleccha (meluhha): mũhe‘face’ (Santali) ; rebus:mũh metal ingot (Santali). Using such readings, it has been demonstrated that the entire corpora of Indus writing which now counts for over 5000 inscriptions + comparable hieroglyphs in contact areas of Dilmun where seals are deployed using the characeristic hieroglyphs of four dotted circles and three linear strokes.

Components of the composite hieroglyph on seal M-299. A ligaturing element is a human face which is a hieroglyph read rebus in mleccha (meluhha): mũhe‘face’ (Santali) ; rebus:mũh metal ingot (Santali). Using such readings, it has been demonstrated that the entire corpora of Indus writing which now counts for over 5000 inscriptions + comparable hieroglyphs in contact areas of Dilmun where seals are deployed using the characeristic hieroglyphs of four dotted circles and three linear strokes. Rebus readings: gaṇḍ 'four'. kaṇḍ 'bit'. Rebus: kaṇḍ 'fire-altar'. kolmo 'three'. Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'. Most of the inscriptions have been listed in the book available through flipkart.com:

The system of accounting using tokens and clay bullae evolved into two streams: 1. cuneiform writing with wedge-shaped letters for syllabic writing; 2. Indus writing for hieroglyphs for logo-semantic writing.

m0478A tablet.

It is now for Richard to explain how he identified the symbols AS symbols and why he does not consider the possibility that the symbols may in fact have been hieroglyphs as outlined in the examples cited here and as detailed for about one thousand hieroglyphs deployed on Indus writing as narratives. Just look at the narrative of a tiger looking upwards at a person perched on a tree-branch. It is reasonable to assume that there were underlying words of a spoken language which could complete the narrative presented pictorially. eraka, hero = a messenger; a spy (G.lex.) kola ‘tiger, jackal’ (Kon.); rebus: kol working in iron, blacksmith, ‘alloy of five metals, panchaloha’ (Tamil) kol ‘furnace, forge’ (Kuwi) kolami ‘smithy’ (Te.) heraka = spy (Skt.); er to look at or for (Pkt.); er uk- to play 'peeping tom' (Ko.) Rebus: eraka ‘copper’ (Ka.) kōṭu branch of tree, Rebus: खोट [ khōṭa ] f A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge.I have not reviewed Richard's analytical framework for explaining pre-literate symbols. I am just pointing out that his assumption about the Indus writing evidences of 'pre-literate' symbols can be countered by treating the 'symbols' as hieroglyphs, read rebus in the lexemes of Indian sprachbund.

Kalyanaraman

May 26, 2013

PS. On Indus language. My contention is that the Indus writers were literate and used meluhha (mleccha), a speech form attested in Manu as mlecchavaacas juxtaposed to aryavaacas. Vaatsyayana refers to writing of mleccha as cryptography, mlecchitavikalpa as one of the 64 arts to be taught to the young students, together with two other language skills: akshara mushtika kathanam, des'abhaashaa jnaanam.

Kalyanaraman