Agricultural Signs in the Indus Script

*Iravatham Mahadevan (iravatham.jani@gmail.com) is a specialist in Indian epigraphy whose areas of specific study are the Indus script and the Brahmi writing system.

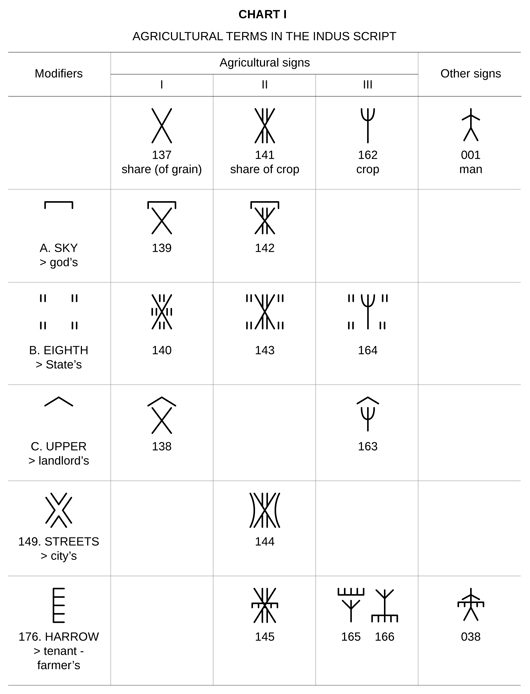

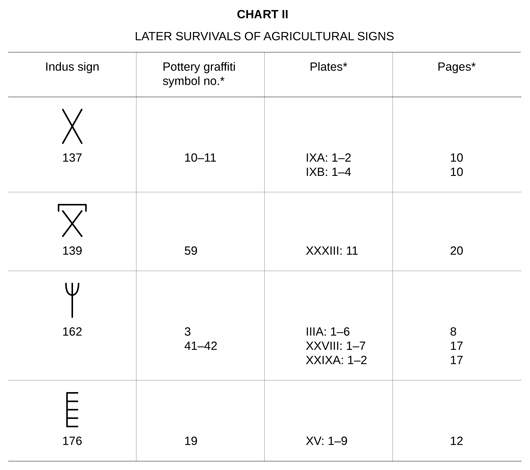

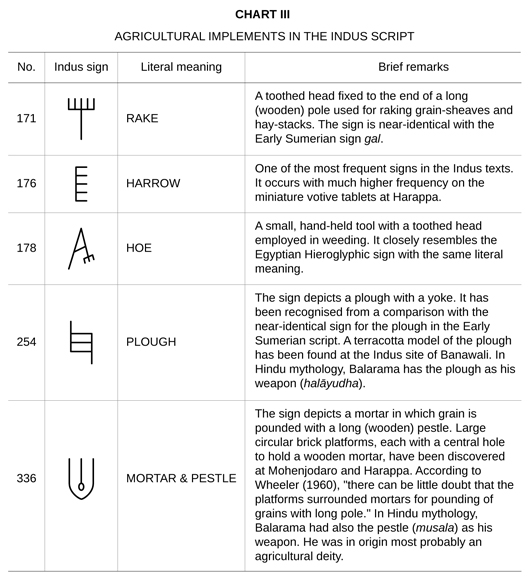

Abstract: The Indus script possessed a set of signs referring to crop and share of the agricultural produce (Chart I). Five hierarchical levels of levies on the produce have been identified, namely, those due to god, state, city, land owner, and the tenant-farmer. Survivals of the agricultural signs in the Indus script as pottery graffiti in later periods are illustrated in Chart II. A list of signs of the Indus script depicting agricultural implements is also included (Chart III).

Keywords: The Indus civilization, the Indus script, agricultural signs in the Indus script, agricultural implements in the Indus script.

Like all other contemporary river-valley civilisations of the Bronze Age, the Indus or Harappan Civilisation was based on agricultural surplus. The annual flooding in the Indus and the rivers of the Punjab brought down rich silt, making irrigated land very fertile. There must have existed an administrative machinery to collect the grain as taxes due to the State or as offerings to the temples. The grain would have been stored in large granaries for distribution as wages, especially to the army of workers employed in the construction of massive public works, such as the brick platform at Mohenjodaro, the fortifications at Harappa, city drainage systems, irrigation canals, and so on.

It would have been convenient to control the apportionment of grain right at the threshing floor. Sheaves of grain-stalks would have been bundled into lots and marked with clay-tags that were then impressed with seals to identify ownership before the grain was transported to granaries or taken away by landlords as their share, leaving the rest as the share of tenant-farmers or wages to the cultivators.

It is thus quite likely that Harappan seals and sealings would contain information on agricultural production and distribution. This probable scenario has led me to search for and identify a remarkable set of closely knit signs that appear to refer to crops and sharing of grain.1

MethodologyThe proposed interpretations are based on the pictorial character of the signs and their probable functions as determined by positional and statistical analysis of the texts. As the “rebus principle” is not invoked in this study, there is no need to make any assumption about the language of the texts.2 I have, however, chosen to cite, wherever apt, bi-lingual (Dravidian and Indo-Aryan) parallels relating to agriculture, as I believe that they represent age-old traditions at the ground level and that they lend support to the proposed ideographic identification of the signs.

Agricultural Terms in the Indus Script (Chart I)Chart I illustrates a set of closely related signs interpreted as “agricultural terms.” The signs are arranged in a grid of columns and rows to bring out their similarities and inter-relationship. It is remarkable that the entire set of agricultural terms is made up of just three “basic” signs combining with five “modifiers.” The basic signs are placed at the head of the three central columns (I to III). The modifiers are listed one below the other in the first column at the left. They consist of three modifying “elements” (labelled A, B, and C) and two modifying signs. The modified compound signs are placed at the junction of the respective columns and rows. The meanings of the basic signs and the modifiers are given in Chart I. The meanings of the compound signs are derived by the combination of the respective modifier and basic sign.

Clik here to view.

As explained below, the basic signs, especially their graphic variants, provide the pictorial clues to their identification.

Sign 137: “to divide, share (as grain)” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

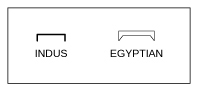

The point of departure for this study is the X-like sign 137, one of the simplest in the Indus script. It invites comparison with the near-identical ideogram in the Egyptian Hieroglyphic script, an ideogram that means “to divide.” The comparison enables us to assign the same general meaning to the corresponding Indus sign, “to divide, share” (Figure 1).

Clik here to view.

Figure 1 Signs to “divide, share”

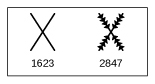

The next clue with respect to what is divided as shares comes from two identical texts on a pair of three-sided, prism-like sealings (1623 and 2847) from Mohenjodaro. These are, incidentally, the longest known Indus texts, each consisting of 26 signs. While all but one of the signs are identical in the two inscriptions, one sign alone (137) shows an interesting variation, providing a precious clue to its meaning. The graphic variant in 2847 shows a pair of stalks laden with grain arranged in X-like form to mean “share (as grain)” (Figure 2). Sign 137 and the modified compound signs derived from it (in column I of Chart I) also have other minor graphic variants, where the straight X-like lines are replaced by curved lines suggestive of slender and supple grain-stalks (e.g., 1179 and 6131).

Clik here to view.

Figure 2 Variants of sign 137 “share (as grain)”

Sign 141: “share of crop” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

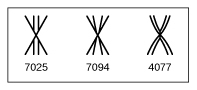

This more elaborate sign can be interpreted as a combination of the X-like element “to share” with a pair of tall vertical lines representing “grain-stalks,” the whole sign having the meaning “share of crop.” The proposed identification is supported by the graphic variants of the sign, which suggest “bundles of grain-stalks tied in the middle” (Figure 3). The modified compound signs derived from sign 141 (in column II of Chart I) also have similar variants (e.g., 2098, 3107, and 4077).

Clik here to view.

Figure 3 Variants of sign 141 “share of crop”

Many Dravidian languages have specific expressions for “share of the crop” that are derived from the verb “to gather, make into bundles, carry away.”

Examples are:

Verbs: Tamil vāru, “to take by the handfuls”; Malayalam vāruka, “to take in a heap”; Kannadavāme, “heap of straw”; Telugu vāru, “to make into a bundle (of hay)”; Malto bāre, “to take out as grain” (DEDR 5362).

Nouns: Tamil vāram, “share, lease of land for a share of the produce, share of the crop of a field”; Malayalam vāram, “share, landlord’s share”; Kannada vāra, “share, landlord’s half-share of the produce in the field in lieu of rent” (DEDR 5359). Cf. Tamil vāri, ‘produce, grain’ (Tamil Lexicon).

Also see the discussion below on Tamil mēl-vāram, “landlord’s share of the produce”; andkuṭi-vāram, “tenant’s share of the produce.” The pictorial depictions in the corresponding Indus signs are in close accord with the imagery invoked by the Dravidian expressions cited above.

Sign 162: “crop” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

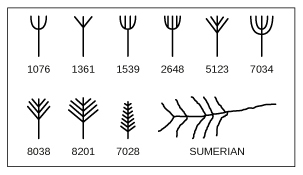

Sign 162 is a self-evident ideogram for “crop” as may be seen from its graphic variants (including signs 167 and 168, now recognised to be mere variants of 162). The sign may also be compared with the identical Sumerian “grain” sign (Figure 4).

Clik here to view.

Figure 4 Variants of “crop” signs 162, 167, 168 and Sumerian “grain” sign

The very realistic depiction of the “crop” sign in the more recently discovered seals from Banawali is conclusive evidence for the proposed identification. (See especially B-12 in CISI, vol. I, 1987). The similar manner in which modifiers are added to this sign like the other two basic signs lends additional support to its identification. The most common expression for “crop” in the Dravidian languages is viḷai: (verb) “to be produced,” (noun) “produce, crop, yield” (DEDR 5437).

Modifiers and Compound SignsModifying element A: “sky” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The modifying element A is near-identical with the corresponding Egyptian ideogram for “sky,” and is accordingly interpreted to mean “sky, heavens, pertaining to god,” etc. (Figure 5). When the element “sky” is placed above the basic signs, the compound signs (in the same row inChart I) acquire the meaning “god’s share of grain or crop.”

The concept of first fruits, “the first agricultural produce of the season, especially when given as an offering to god” (Oxford English Dictionary), is familiar to all agricultural societies. Many Dravidian languages have specific expressions for “god’s first share of the produce” – e.g., Malayalam mīttal, “first fruits, offering to demons”; Kodava mīdi, “offering to a god”; Telugu mīdu, “what is devoted or set aside for a deity” (DEDR 4841). Cf. Tamil midupoli, “grain first taken from the grain heap at the threshing floor for charitable purposes” (Tamil Lexicon).

Clik here to view.

Figure 5 Signs for “sky”

Compound signs for “god's share of the grain/crop” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The compound sign 139 occurs only on seals, mostly from Mohenjodaro. It is the only sign on a large “unicorn” seal from Chanhudaro (6131). It would appear that seals with this sign were used by temple functionaries to mark the clay-tags affixed to bundles of grain-stalks which were set apart as “god’s first share of the produce” at the threshing floor.

The compound sign 142 occurs only on the miniature tablets and sealings from Harappa. The function of 142 seems to be somewhat different from that of 139. Sign 142 may depict the voluntary offerings by small farmers or tenants of the first fruits to god before further apportionment of the grain. Apparently, the miniature tablets or sealings marked with this sign would be placed on bundles of grain-stalks or heaps of grain offered to the deity.

Modifying element B: “one-eighth” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The modifying element B consists of eight vertical short strokes arranged in four pairs around the basic signs. The context indicates the meaning “one-eighth.”

Compound signs for “one-eighth share of grain/crop (due to the State)” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

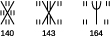

The compound signs 140, 143, and 164, which mean, literally, “one-eighth share of grain or crop,” are interpreted as the “State’s share of the produce” from the following evidence. The Pillar Inscription of Asoka at Lumbini, the place of birth of the Buddha, states:

luṃmini-gāmēubalikēkaṭēaṭha-bhāgiyē ca.

The village of Lumbini was made free of taxes and to pay [only] an eighth share [of the produce]. (Inscriptions of Asoka, Hultzsch (ed.), Rummindei Pillar Inscription)

Hultzsch cites Fleet (JRAS, 1908, p. 479) that “aṭha-bhāga (from Sanskrit ashṭa-bhāga) is an ‘eighth share’ which the king is permitted by Manu (VII: 130) to levy on grains.”

Apparently, the Harappan rate of land revenue at one-eighth the share of the produce continued down the ages, and was later codified by Manu and was prevalent until at least the Mauryan age. In later times, the rate of land revenue varied from place to place. Tamil literary and inscriptional sources mention āṟil-oṉṟu (“one-sixth”) as the prescribed rate. The general term for “tax on land” in Tamil was iṟai (DEDR 521).

Modifying element C: “roof” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The modifying element C, representing the roof, is interpreted to mean “upper, higher, above,” etc. (cf. Tamil mēl). When it is added to the basic signs for “share of grain/crop,” the compound signs are interpreted to mean “upper share of the produce.”

Compound signs for “upper (landlord's) share of grain/crop” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The compound signs 138 and 163, combining “upper” with “share of grain or crop” respectively, seem to have the same meaning, namely the “upper share of the produce (due to the landlord).” The interpretation is suggested by the Tamil literary and inscriptional usage which equates “upper share” with “landlord’s share” of the produce; e.g., Tamil mēl-vāram, “the proportion of the crop or produce claimed by the land holder” (Tamil Lexicon). The term generally occurs in contrast with kuṭi-vāram, “tenant’s share” (discussed below).

Modifying sign 149: “streets” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

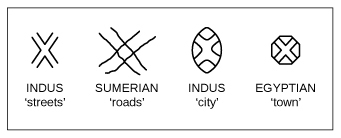

Sign 149 depicts pictorially “crossroads.” It may be compared with the near-identical Sumerian sign for “roads.” The Indus sign can be interpreted as “streets” or “part of a city” when compared with another Indus sign (284) for “city” which has an exact counterpart in an Egyptian ideogram (Figure 6).

Clik here to view.

Figure 6 Signs for “streets” and “city”

Compound sign 144: “streets' share” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

The compound sign 144 can be analysed as follows: “streets” (149) + “share of crop” (141) = “streets’ share of the crop” (144).

We learn from Tamil inscriptional evidence that a levy known as pāṭi-kāval (literally, “levy for guarding the streets”) was collected from the citizens for payment to those guarding the city or village (Tamil Lexicon). It is quite likely that a similar system of municipal taxation was in vogue in the highly organised urban societies of the Indus Civilisation.

Modifying sign 176: “harrow” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

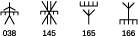

Sign 176, apparently a toothed implement, is interpreted as a “harrow.” The harrow symbolises “cultivating tenant” in the compound signs to which it is added. Note particularly the compound sign:

176 (“harrow”) + 001 (“man”) = 038 (“ploughman, farmer”).

Cf. Tamil kuṭi/kuṭiy-āl, “tenant”; Malayalam kuṭiyān, “tenant” (DEDR 1655); Tamil, Malayalam, Kannada, āḷ, “man, servant, labourer” (DEDR 399).

Compound signs for “tenant” and “tenant's share of crop” Image may be NSFW.

Clik here to view.

Sign 145 is interpreted as a compound of “share” (X-like element), “grain-stalks” (pair of tall vertical lines), and the “harrow.” The compound sign means the “share of crop due to the tenant-farmer.” (See Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions, vol. I, M391, for a realistic variant of this sign.) Similarly, signs 165 and 166 are compounds of “harrow” (176) and “crop” (162) with the same meaning, “the share in the produce of the tenant.” Compare Tamilkuṭi-vāram, “the share of the produce to which a ryot is entitled” (Tamil Lexicon).

Clik here to view.

* References to Lal (1960).

It is very significant that some of the agricultural signs of the Indus script survived as isolated symbols in the pottery graffiti of the succeeding Chalcolithic and Megalithic periods (Lal 1960). The relevant comparisons from Lal’s photographic catalogue are listed in Chart II.

While Lal has compared the pottery graffiti with similar-looking Indus signs, he has refrained from offering any interpretations. In the light of the present identification of the Indus signs listed above as “agricultural terms,” it is perhaps not too far-fetched to suggest that the corresponding symbols occurring as graffiti on pottery during the Chalcolithic and Megalithic periods had the same significance. The survivals lend support to the linguistic parallels linking Harappan agricultural practices with later traditions suggested in the paper.

Agricultural Implements in the Indus Script (Chart III)Agricultural implements depicted in the Indus script have been recognised from their pictorial character, and also by comparison with near-identical signs in other pictographic scripts like the Egyptian Hieroglyphic and the Early Sumerian. However, the signs were not employed in their literal sense but with other meanings by ideographic association or through the rebus method. Such interpretations are not considered here. It is still instructive to study the literal meanings of the signs for the light they throw on the earliest agricultural economy in South Asia. The Indus signs, their literal meanings, and brief remarks on their identification are provided in Chart III.

Clik here to view.

It remains for us to add some comments on a few points arising out of the proposed identification of agricultural signs in the Indus script.

Modifiers. The modifying elements and signs in Chart I modify the sense and not the sound of the basic signs. In other words, the additions are semantic and not phonetic. The modifiers act as attributes qualifying the sense of the basic signs. Chart I indicates that in the Harappan language the attribute precedes the noun it qualifies. Further, it is not necessary that a compound sign should have two phonetic elements; it may be a single word.

Signs stand for personal nouns also. The signs listed in Chart I can also be interpreted, when warranted by the context, as the corresponding personal nouns.

(e.g.) share > share-holder, share-cropper

crop > one who grows the crop, agriculturist

harrow > tenant-farmer

streets > citizens, municipal authority.

Such interpretations are more likely when the signs occur initially or when followed by nominal suffixes in the texts.

Other signs. Signs 001 (“man”) and 149 (“streets”) are not “agricultural terms,” but are included in Chart I as they combine with agricultural signs to produce compound signs interpreted as agricultural terms.

Frequent signs in other contexts. The two signs mentioned above (001 and 149), and also the signs 162 (“crop”) and 176 (“harrow”) occur very frequently in the Indus texts in other contexts. In such cases, these signs may have much wider, though still related, significance (not considered in this paper).

Redundancy of signs. Signs in the same rows have virtually the same meanings. The redundancy could have arisen at different places and during different periods. Perhaps some of them are not redundant but have nuances and shades of meanings that elude us at this preliminary stage of analysis. Even after allowing for such possibilities, one is left with the impression that the Indus script, even in its mature stage, is a limited type of writing, comprised almost wholly of word-signs that represent matters of interest to the ruling classes. Such redundancy, as seen even in this limited set of signs, is not expected to be present if the script had reached a more advanced stage, as Sumerian or Egyptian did.

Parallels from other pictographic scripts. The parallels cited from Sumerian and Egyptian scripts do not mean that they are related to the Indus script or that there were direct borrowings from them. When picture-signs are drawn from material objects, there are bound to be some similarities even between unrelated scripts. However, ideographic signs from different scripts can be compared only semantically and would have no phonetic connections.

Bi-lingual parallels. The bi-lingual parallels (from Dravidian and Indo-Aryan) cited in the paper are intended to highlight the cultural unity and continuity of traditions, which get reflected as parallel expressions in languages belonging to different families. As mentioned at the outset, the interpretations proposed here are ideographic and not based on linguistic arguments.

The grid. The grid of related signs presented in Chart I has turned out to be a powerful tool for analysis. Even the very rare signs, which occur only once each (144, 145, 164, 165, and 166) and are hence normally unanalysable, have been identified with some confidence because of the pattern brought out by the grid. What is more, one can even predict that the blank squares in columns I–III in Chart I would be filled up in due course by new discoveries of compound signs, which would be combinations of the basic signs and respective modifiers.

1 Text Numbers, Sign Numbers and statistics are cited from my book, The Indus Script: Texts, Concordance and Tables (1977). Four-digit numbers refer to texts and three-digit numbers to signs. The Sign List and List of Sign Variants in the book are the sources for the illustrations.

2 For example, the picture of an 'eye' can be read as 'I', first person singular pronoun, if the language is English.

| A Dravidian Etymological Dictionary (DEDR) (1984), Burrow, T., and Emeneau, M. B. (eds.), Clarendon Press, Oxford, 2nd ed. | |

| Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions (CISI) (1987), vol. 1, Joshi, Jagat Pati and Parpola, Asko (eds.), Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Helsinki. | |

| Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions (CISI) (1991), vol. 2, Shah, S. G. M., and Parpola, Asko (eds.), Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Helsinki. | |

| Corpus of Indus Seals and Inscriptions (CISI) (2010), vol. 3.1, Parpola, Asko, Pande, B. M., and Koskikallio, Petteri (eds.), Suomalainen Tiedeakatemia, Helsinki. | |

| Englund, R. K., and Gregoire, J-P (1991), The Proto-Cuneiform Texts from Jamdet Nasr, Gebr. Mann Verlag, Berlin. | |

| Gardiner, A. H. (1927), Egyptian Grammar: Being an Introduction to the Study of Hieroglyphs, Clarendon Press, Oxford. | |

| Hultzsch, E. (ed.) (1991), Inscriptions of Asoka, Corpus Inscriptionum Indicarum, vol. I, reprint, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi. | |

| Lal, B. B. (1960), “From the Megalithic to the Harappa: Tracing Back the Graffiti on Pottery,” Ancient India, 16, pp. 4–24. | |

| Mahadevan, Iravatham (1977), The Indus Script: Texts, Concordance and Tables, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi. | |

| Tamil Lexicon (1982), University of Madras, Madras. | |

| Wheeler, Mortimer (1960), The Indus Civilization, second edition, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2nd ed. Image may be NSFW.

|