https://tinyurl.com/uct98ka

This monograph is presented in two sections dealing with inscriptions found in Sri Lanka which include both Indus Script hieroglyphs and Brāhmi syllables.

Section 1. Annaikottai seal inscription

Section 2: Tissamaharama inscription

The continued use of Indus Script hieroglyphs on these two inscriptions is consistent with the fact that millions of early coins from mints also signified the Indus Script hieroglyphs to signify the wealth resources worked on in the mints. Indus Script is also used as top line on pre-Mauryan Sohgaura copper plate inscription. See:

https://tinyurl.com/uct98ka

The focus of this monograph is on the Indus Script hieroglyphs on these inscriptions while recognizing variant readings of Brāhmi syllables included in the inscriptions. It is seen that on both the inscriptions, the combination of Brāhmi syllables is NOT intended to be a transliteration of Indus Script readings but as signifiers of personal titles/names and of trade contract. Thus, Annaikottai seal Brāhmi syllables signify ko-veta'chieftain'; the Tissamaharam Brāhmi syllables signify tiraLi muRi 'agreement of the assembly'.

The accompanying Indus Script hieroglyphs amplify the Brāhmi message by adding on Annaikottai Brāhmi inscription 'metalcasting smithy, mint' and on Tissamaharama Brāhmi

inscription, the agreement is between iron ore smelter, smith (Sign 18) and iron ore metal infusion smith (Sign 1)-- i.e., between persons signified by Sign 18 and Sign 1 (read from r.. to l.). If the ligature on Sign 1 is read as an arch, the reading is: manda 'arch' rebus: manda'warehouse'. Thus, Sign 1 variant on seal (with an arch atop the standing person) may read as mint warehouse.

Indus Script is linguistic hieroglyphic writing कर्णक 'rim-of-jar' rebus करण 'writer, scribe' kunda singi ‘lathe, spiny-horn’ rebus ‘fine, ornament gold’ https://tinyurl.com/rbqnfzu

Indus Scripthieroglyphs used on Annaikottai seal

Sign307, Sign 162, Sign 162 of Indus Script

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() Decipherment of Indus Script hieroglyphs: kamaḍha'archer' Rebus: kammaṭa'mint, gold furnace' PLUS kāˊṇḍa 'arrow' rebus: khṇḍa 'equipment' (See Santali expression shown below) PLUS kolmo'rice-plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS dula'duplicated' rebus: dul'metalcasting'. Thus, metalcasting smithy, mint.

Decipherment of Indus Script hieroglyphs: kamaḍha'archer' Rebus: kammaṭa'mint, gold furnace' PLUS kāˊṇḍa 'arrow' rebus: khṇḍa 'equipment' (See Santali expression shown below) PLUS kolmo'rice-plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS dula'duplicated' rebus: dul'metalcasting'. Thus, metalcasting smithy, mint.

Indus Script hieroglyphs used on Tissamaharama inscription

Indus Script hieroglyphs used on Annaikottai seal inscription compare with Sign 18 and Sign 1 of Indus Script![]()

![]() Sign 1 is shown as a variant on an Indus Script seal with a standing person wearing a scarf as a pigtail.

Sign 1 is shown as a variant on an Indus Script seal with a standing person wearing a scarf as a pigtail.

The standing person with pigtail (sacrf) compares with a standing person on an Indus Script seal

These two Indus Script hieroglyphs on Annaikottai seal have been deciphered:

Sign 18: eraka 'upraised arm' rebus: arka, 'copper, gold'; eraka 'metal infusion,moltencast' PLUS meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron'. Thus, iron metal infusion (smith)

Sign 1 (with variant of scarf as pigtail): meD 'body' rebus: meD 'iron' PLUS dhatu 'scarf' Rebus: dhatu, 'mineral ore'. Thus, iron ore.( smelter, smith).

Framework:maNDA 'framework' rebus: manDA 'warehouse' PLUS text message:

h179A, B 4307 Pict-83: Person wearing a diadem or tall W head-dress standing within an ornamented arch; there are two stars on either side, at the bottom of the arch.

Hieroglyph: कर्णक (ifc. f(आ).) 'a tendril' Rebus: कर्णक 'scribe, steersan' PLUS maNDA 'framework' rebus: manDA 'warehouse'.Thus, warehouse scribe, steersman. The three prongs as head-dress or crown of the standing person: kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'.

Sign48 baraḍo 'spine, backbone' rebus: baran, bharat 'mixed alloys' (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin) (Punjabi)

kāmṭhiyɔ kāmaṭhiyo a bowman; an archer (Skt.) (CDIAL 2760) rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner' ...

Sign 342 kanda kanka 'Equipment supercargo'

Pictorial motif of arch on h179 tablet

maṇḍa ʻ some sort of framework (?) ʼ. [In nau -- maṇḍḗ n. du. ʻ the two sets of poles rising from the thwarts or the two bamboo covers of a boat (?) ʼ ŚBr. (as illustrated in BPL p. 42); and in BHSk. and Pa. bōdhi -- maṇḍa -- n. perh. ʻ thatched cover ʼ rather than ʻ raised platform ʼ (BHS ii 402). If so, it may belong to maṇḍapá -- and maṭha -- ]Ku. mã̄ṛā m. pl. ʻ shed, resthouse ʼ (if not < *mã̄ṛhā < *maṇḍhaka -- s.v. maṇḍapá -- ).(CDIAL 9737) maṇḍapa m.n. ʻ open temporary shed, pavilion ʼ Hariv., ˚pikā -- f. ʻ small pavilion, customs house ʼ Kād. 2. maṇṭapa -- m.n. lex. 3. *maṇḍhaka -- . [Variation of ṇḍ with ṇṭ supports supposition of non -- Aryan origin in Wackernagel AiGr ii 2, 212: see EWA ii 557. -- Prob. of same origin as maṭha -- 1 and maṇḍa -- 6 with which NIA. words largely collide in meaning and form]1. Pa. maṇḍapa -- m. ʻ temporary shed for festive occasions ʼ; Pk. maṁḍava -- m. ʻ temporary erection, booth covered with creepers ʼ, ˚viā -- f. ʻ small do. ʼ; Phal. maṇḍau m. ʻ wooden gallery outside a house ʼ; K. manḍav m. ʻ a kind of house found in forest villages ʼ; S. manahũ m. ʻ shed, thatched roof ʼ; Ku. mãṛyā, manyā ʻ resthouse ʼ; N. kāṭhmã̄ṛau ʻ the city of Kathmandu ʼ (kāṭh -- < kāṣṭhá -- ); Or. maṇḍuā̆ ʻ raised and shaded pavilion ʼ, paṭā -- maṇḍoi ʻ pavilion laid over with planks below roof ʼ, muṇḍoi, ˚ḍei ʻ raised unroofed platform ʼ; Bi. mã̄ṛo ʻ roof of betel plantation ʼ, mãṛuā, maṛ˚, malwā ʻ lean -- to thatch against a wall ʼ, maṛaī ʻ watcher's shed on ground without platform ʼ; Mth. māṛab ʻ roof of betel plantation ʼ, maṛwā ʻ open erection in courtyard for festive occasions ʼ; OAw. māṁḍava m. ʻ wedding canopy ʼ; H. mãṛwā m., ˚wī f., maṇḍwā m., ˚wī f. ʻ arbour, temporary erection, pavilion ʼ, OMarw. maṁḍavo, māḍhivo m.; G. mã̄ḍav m. ʻ thatched open shed ʼ, mã̄ḍvɔ m. ʻ booth ʼ, mã̄ḍvī f. ʻ slightly raised platform before door of a house, customs house ʼ, mã̄ḍaviyɔ m. ʻ member of bride's party ʼ; M. mã̄ḍav m. ʻ pavilion for festivals ʼ, mã̄ḍvī f. ʻ small canopy over an idol ʼ; Si. maḍu -- va ʻ hut ʼ, maḍa ʻ open hall ʼ SigGr ii 452.

2. Ko. māṁṭav ʻ open pavilion ʼ.3. H. mã̄ḍhā, māṛhā, mãḍhā m. ʻ temporary shed, arbour ʼ (cf. OMarw. māḍhivo in 1); -- Ku. mã̄ṛā m.pl. ʻ shed, resthouse ʼ (or < *

With these readigs of the Indus Script hieroglyphs on Annaikottai seal, the Brāhmi inscription read by Mahadevan seems concordant with the message of

Tirali Muri 'written agreement of the assembly'.

Section 1. Annaikottai (variant spelling Annaicoddai) seal inscription

https://tinyurl.com/yfkq6fap

![Image result for tree indus script]()

Metal seal is discovered by prof. Indrapala of Jaffna (The Hindu dated 28th Aptil 1981 )

kamaḍha 'archer'; kamāṭhiyo = archer; kāmaṭhum = a bow; kāmaḍ, kāmaḍum = a chip of bamboo (G.) kāmaṭhiyo a bowman; an archer (Skt.lex.) Rebus: kammaṭi a coiner (Ka.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Ta.) kammaṭa = mint, gold furnace (Te.)

kāˊṇḍa (kāṇḍá -- TS.) m.n. ʻ single joint of a plant ʼ AV., ʻ arrow ʼ MBh., ʻ cluster, heap ʼ (in tr̥ṇa -- kāṇḍa -- Pāṇ. Kāś.). [Poss. connexion with gaṇḍa -- 2 makes prob. non -- Aryan origin (not with P. Tedesco Language 22, 190 < kr̥ntáti). Prob. ← Drav., cf. Tam. kaṇ ʻ joint of bamboo or sugarcane ʼ EWA i 197]Pa. kaṇḍa -- m.n. ʻ joint of stalk, stalk, arrow, lump ʼ; Pk. kaṁḍa -- , °aya -- m.n. ʻ knot of bough, bough, stick ʼ; Ash. kaṇ ʻ arrow ʼ, Kt. kåṇ, Wg. kāṇ, kŕãdotdot;, Pr. kə̃, Dm. kā̆n; Paš. lauṛ. kāṇḍ, kāṇ, ar. kōṇ, kuṛ. kō̃, dar. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ torch ʼ; Shum. kō̃ṛ, kō̃ ʻ arrow ʼ, Gaw. kāṇḍ,kāṇ; Kho. kan ʻ tree, large bush ʼ; Bshk. kāˋ'n ʻ arrow ʼ, Tor. kan m., Sv. kã̄ṛa, Phal. kōṇ, Sh. gil. kōn f. (→ Ḍ. kōn, pl. kāna f.), pales. kōṇ; K. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ stalk of a reed, straw ʼ (kān m. ʻ arrow ʼ ← Sh.?); S. kānu m. ʻ arrow ʼ, °no m. ʻ reed ʼ, °nī f. ʻ topmost joint of the reed Sara, reed pen, stalk, straw, porcupine's quill ʼ; L. kānã̄ m. ʻ stalk of the reed Sara ʼ, °nī˜ f. ʻ pen, small spear ʼ; P. kānnā m. ʻ the reed Saccharum munja, reed in a weaver's warp ʼ, kānī f. ʻ arrow ʼ; WPah. bhal. kān n. ʻ arrow ʼ, jaun. kã̄ḍ; N. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, °ṛo ʻ rafter ʼ; A. kã̄r ʻ arrow ʼ; B. kã̄ṛ ʻ arrow ʼ, °ṛāʻ oil vessel made of bamboo joint, needle of bamboo for netting ʼ, kẽṛiyā ʻ wooden or earthen vessel for oil &c. ʼ; Or. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻ stalk, arrow ʼ; Bi. kã̄ṛā ʻ stem of muñja grass (used for thatching) ʼ; Mth. kã̄ṛ ʻ stack of stalks of large millet ʼ, kã̄ṛī ʻ wooden milkpail ʼ; Bhoj. kaṇḍā ʻ reeds ʼ; H. kã̄ṛī f. ʻ rafter, yoke ʼ, kaṇḍā m. ʻ reed, bush ʼ (← EP.?); G. kã̄ḍ m. ʻ joint, bough, arrow ʼ, °ḍũ n. ʻ wrist ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint, bough, arrow, lucifer match ʼ; M. kã̄ḍ n. ʻ trunk, stem ʼ, °ḍẽ n. ʻ joint, knot, stem, straw ʼ, °ḍī f. ʻ joint of sugarcane, shoot of root (of ginger, &c.) ʼ; Si. kaḍaya ʻ arrow ʼ. -- Deriv. A. kāriyāiba ʻ to shoot with an arrow ʼ.kāˊṇḍīra -- ; *kāṇḍakara -- , *kāṇḍārā -- ; *dēhīkāṇḍa -- Add.Addenda: kāˊṇḍa -- [< IE. *kondo -- , Gk. kondu/lo s ʻ knuckle ʼ, ko/ndo s ʻ ankle ʼ T. Burrow BSOAS xxxviii 55]S.kcch. kāṇḍī f. ʻ lucifer match ʼ? *kāṇḍakara ʻ worker with reeds or arrows ʼ. [kāˊṇḍa -- , kará -- 1 ]L. kanērā m. ʻ mat -- maker ʼ; H. kãḍerā m. ʻ a caste of bow -- and arrow -- makers ʼ. *kāṇḍārā ʻ bamboo -- goad ʼ. [kāˊṇḍa -- , āˊrā -- ]Mth. (ETirhut) kanār ʻ bamboo -- goad for young elephants ʼ < *ka&rtodtilde;ār. kāˊṇḍīra ʻ armed with arrows ʼ Pāṇ., m. ʻ archer ʼ lex. [kāˊṇḍa -- ]H. kanīrā m. ʻ a caste (usu. of arrow -- makers) ʼ.(CDIAL 3023 to 3026).

Hieroglyph: arrowTamil-Brāhmi inscriptions mixed in with Megalithic Graffiti Symbols found in Annaikottai, Sri Lanka.

Metal seal is discovered by prof. Indrapala of Jaffna (The Hindu dated 28th Aptil 1981 )

kamaḍha 'archer'; kamāṭhiyo = archer; kāmaṭhum = a bow; kāmaḍ, kāmaḍum = a chip of bamboo (G.) kāmaṭhiyo a bowman; an archer (Skt.lex.) Rebus: kammaṭi a coiner (Ka.); kampaṭṭam coinage, coin, mint (Ta.) kammaṭa = mint, gold furnace (Te.)

Hieroglyph: arrowTamil-Brāhmi inscriptions mixed in with Megalithic Graffiti Symbols found in Annaikottai, Sri Lanka.

The two duplicated graffiti symbols resemble and may be variants of Sign 162

This sign 162 is read in Meluhha rebus as: kolmo 'rice-plant' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS dula 'duplicated' rebus: dul 'metalcasting'. Thus, metalcasting smithy.

The following details are taken from wikipedia.

[quote]Annaicoddai Seal is a steatite seal that was found in Annaicoddai, Sri Lanka during archeological excavations of a megalithic burial site by a team of researchers from the Jaffna University. The seal contains some of the oldest inscriptions in Tamil-Brāhmi mixed with Megalithic Graffiti symbols found on the island and is dated to early 3rd or late 4th century BC. Although many pottery fragments have been found in excavations throughout Sri Lanka and Southern India that had both varieties of Brāhmi and Megalithic Graffiti Symbols side by side, Annaicoddai seal is distinguished by having each written in a manner that indicates that the Megalithic Graffiti Symbols may be a translation of the Brahmi characters. Read from right to left, the legend is read as ‘Koveta’ (Ko-vet-a). Linguists read it as in South Dravidian or early Tamil indicating a chieftain or king. Similar inscriptions have been found throughout ancient Tamilakam, in modern day South India. (Indrapala, Karthigesu (2007). The evolution of an ethnic identity: The Tamils in Sri Lanka C. 300 BCE to C. 1200 CE. Colombo: Vijitha Yapa, pp. 337–338; Raghupathy, Ponnambalam (1987). Early settlements in Jaffna, an archaeological surveyMadras: Raghupathy, pp. 199-204). Investigators disagree on whether Megalithic Graffiti Symbols found in South India and Sri Lanka constitute an ancient writing system that preceded the introduction and widespread acceptance of Brāhmi variant scripts or non lithic symbols. The purpose of usage remains unclear. (Boivin, Nicole; Korisettar, Ravi; Venkatasubbaiah, P.C (2003), "Megalithic Markings in Context: graffiti marks on burial pots from Kudatini, Karnataka", South Asian Studies, 19 (1): 21–33, pp. 29-31). [unquote]

Section 2: Tissamaharama inscription

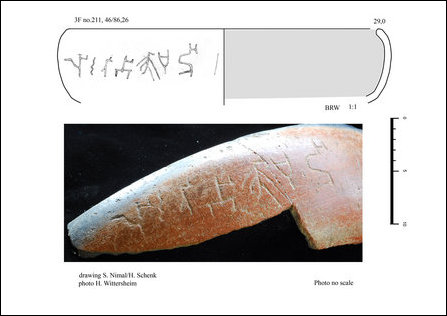

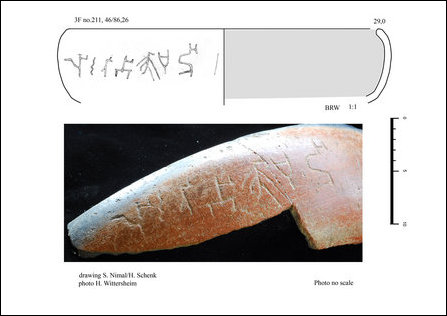

Readings of Tissamaharama inscription with bi-script, Brāhmi syllables and Indus Script hieroglyphs

-- variant readings by Mahadevan and Ragupathy

Mahadevan reads the meaning of Tirali Muri as written agreement of the assembly. He further postulates that it indicates the presence of a Tamil trade guild in Southern Sri Lanka in the 2nd century BCE.

P. Ragupathy reads it as indicating a vessel specified for the purpose of serving rice portions. He postulates that it indicates the presence of common people not a trade guild.

For ready reference, the texts of some of the URL links are appended.

Tissamaharama potsherd evidences ordinary early Tamils among population

[TamilNet, Wednesday, 28 July 2010, 03:18 GMT]A potsherd inscription in Tamil Brāhmi found some times back in an archaeological excavation by a German team at Tissamaharama in the Hambantota district of the Southern Province of Sri Lanka can be interpreted as meaning an equipment to measure, and thus evidences the presence of ordinary Tamil speaking people in the population of that region as early as at 2200 years before present, says archaeologist and epigraphist, Ponnampalam Ragupathy. The identification of the script of the legend as Tamil Brāhmi and the decipherment getting the reading Thira’li Mu’ri in Tamil by veteran epigraphist Iravatham Mahadevan in an article last month in The Hindu, has stirred interest of the archaeological circles in the island to unearth this old find from obscurity to limelight.

Inscribed potsherd from archaeological excavation at Tissamaharama, Hambantota District, Sri Lanka: From left to right the first letter is Li, second one is ra and the third one is ti. From right to left they are read as tiraLi. The fourth and fifth ones are symbols or graffiti marks. The sixth letter is mu and the seventh one is Ri. The last two are read from left to right as muRi. A little away is found a vertical line that perhaps marks the end of the legend. [Image courtesy: Department of Archaeology, Sri Lanka and the academics who sent it]

Full text of the article by Dr. P. Ragupathy:

An inscribed piece of pottery from Tissamaharama

An inscribed piece of Black and Red Ware pottery was found in the archaeological excavations at Tissamaharama in the Hambantota District of Southern Province, Sri Lanka, sometimes back.

Information of the find, along with decipherment of the legend, appeared in The Hindu on 24th June, in an article “An Epigraphic Perspective on the Antiquity of Tamil,” written by veteran epigraphist Iravatam Mahadevan. His article has kindled interest in the official circles of archaeology in Sri Lanka to take notice of the find, which was hitherto not brought by them to the knowledge of the public.

According to Iravatam Mahadevan, the piece of pottery was found in the earliest layer of the excavation and the German scholars who undertook the excavation provisionally dated it to around 200 BCE.

Mahadevan, who identifies the writing on the pottery as Tamil in the Tamil Brāhmi script, reads it as “tiraLi muRi” and interprets it as “written agreement of the assembly”.

“The inscription bears testimony to the presence in southern Sri Lanka of a local Tamil merchant community organised in a guild to conduct inland and maritime trade as early as at the close of the 3rd century BCE,” he further says in the article.

A few days ago, the present writer received a clear photograph and a drawing of the pottery sent by academic sources in Sri Lanka seeking opinion.

A perusal of the pottery legend as it appears in the photographs show that Iravatham Mahadevan’s identification of the script as Tamil Brāhmi and his reading of the legend in Tamil could hardly be challenged. But there are possibilities of alternative interpretations.

The legend is a combination of readable Tamil Brāhmi and unreadable graffiti or symbols that usually appear in megalithic and early historic pottery.

From left to right, the first three are Brāhmi letters, the next two are symbols and the following last two letters are again in Brāhmi. There is a vertical line, a little bit away from the legend that perhaps marks the end of the legend like a full stop.

Mahadevan reads the first three letters from right to left to get the reading ‘thiraLi’ and reads the last two letters from left to right to get the reading ‘muRi,’ keeping the unreadable symbols in the middle.

Brāhmi was usually written from left to right just like all the South Asian-origin scripts of today. In the very few occasions when Tamil Brāhmi was found written from right to left, the letters were inverted to serve the purpose of reading it from the above. (Mahadevan, I., 2003, Early Tamil Epigraphy p 179-180).

However, in the island of Sri Lanka, some examples have already been noticed in which Brāhmi was found written from right to left without inverting the letters, indicating that even though obscure it was a writing practice in the island. (Paranavitana 1970, Inscriptions of Ceylon Vol I, plate xxii; Karunaratne. S., 1984, cited by Mahadevan, ibid. p.180).

But, perhaps this is the first time, a single legend is partly read from right to left and partly read from left to right, keeping symbols in the middle. The reason for this way of the writing in the pottery needs investigation.

From left to right, the first letter of the pottery legend is a clear Tamil BBrāhmi‘Li’ (palatal L). This script is known in the Brāhmi inscriptions of Sri Lanka too. No word begins from this letter in the known diction of Tamil, Sinhala, Prakrit or Sanskrit. Mahadevan is logical in reading the three letters placed left to the symbols from right to left to get the meaningful word ‘tiraLi’.

The last letter of the legend (as counted from left to right) is a clear Tamil Brāhmi script ‘Ri’ (retroflex R). A few years ago Prof. P. Pushparatnam identified the presence of retroflex R in the Brāhmi inscriptions of Sri Lanka. (Pushparatnam. P., cited by Mahadevan I., ibid., p.195).

Once again Mahadevan is logical in reading the last two letters placed right to the symbols from left to right to get the meaningful word ‘muRi’,

But why the legend meaning “written agreement of the assembly” of trade guild connotations according to Mahadevan, should appear on a small pottery of day-to-day use is a question.

Such pottery legends usually mark individual ownership, serving the purpose of identification.

Both ‘tiraLi’ and ‘muRi’ are connected to the words tiraL, muRi and muRai, listed as Tamil words in the Dravidian Etymological Dictionary (entries, 3245, 5008, 5010 and 5015).

The word ‘muRi’ as a noun has several shades of meaning in Tamil. In its literary usages it means sprout or young leaf in Cankam diction; writing, deed, document, written agreement etc in early medieval diction and settlement in old lexicons (Glossary of Historical Tamil Literature, Santi Sadhana, p.2028).

The word ‘muRai’, apart from agreement, approved code of conduct etc (DED 5015), also means share (panku), measure (aLavu) and portion (pakuti) in the Cankam diction itself. (nattiNai 336:6; neTunalvaaTai 70, 177)

The latter shades of meanings are from the verb form of the word muRi, which means ‘to divide, break down etc’ (DED 5008). In the lexicons muRai also means anything that is amassed (kooTTu). (Pinkalam 10:953).

In some instances of usage in Tamil inscriptions muRi means a division of land (DED 5008, Glossary of Tamil Inscriptions, Santi Sadhana, p.510).

Interestingly in a surviving usage of contemporary Eezham Tamil, muRi means a chunk, portion etc (as in ‘meen muRi’ for a piece of fish in the curry).

The shade of meaning, deed, agreement or written bond for the word muRi is found for the first time only in the devotional literature of the 7th century CE (Glossary of Historical Tamil Literature, ibid.). This shade of meaning must have come from the Cankam usage of the word for leaf. But the meanings share, division, measure etc from the verb root muRi are older shades of meaning as found in muRai and are more or less contemporaneous in usage to the pottery legend under discussion.

Therefore, it may be more appropriate to consider that the word ‘muRi’ in the potsherd legend means a measuring utensil or a standard cubic measure. The pottery in question is a flat bottomed and raised edged dish. But it is deep enough to be a cubic measure.

Interestingly, the other word ‘tiraLi’ could also mean the same – ‘an equipment to amass’.

The word ‘tiraL’ as a verb means, to become round, globular, assemble, congregate, collect in large numbers, accumulate, abound etc (DED 3245) and as a noun or adjective means, mass, matured produce, group, ball of rice, society, heap, pearl, congregation of people etc (Glossary of Historical Tamil Literature p.1049).

Even though tiraL could mean an assembly of people, neither the word nor the derivate tiraLi was ever found used to indicate a trade guild.

In fact, in available Tamil diction tiraLi as a noun only means a kind of fish. Another derivate tiraLai means a ball of cooked rice.

However, originating from the verb root tiraL, the word tiraLi could very well mean a utensil or equipment that was used in amassing commodities - in other words a cubic measure.

In this context, note the word-formation ‘uruLi’ in Malayalam for a particular type of vessel, originating from the verb root ‘uruL’ (to round).

There is another possibility that tiraLi muRi may mean ‘a mould for cooked rice’ or a measure for rice balls (from tiraLai). Various dishes made of cooked rice are served in the temples in the moulded form even today.

Such moulded rice items served in the temples are called taLikai (taLicai, taLucai, taLacil in Eezham Tamil), because, they are moulded by a type of eating-vessel or dish called by the same name taLikai.

Temples used to keep a separate vessel called taLikaik-ki’n’nam for this purpose (Winslow’s Tamil Dictionary). This vessel is used in inverted way.

Until recent past, payment of daily wages to certain categories of workers was in the form of cooked and moulded portions of rice, specified in numbers. Standard vessels of measurement must have been used for moulding the portions.

One could also see this practice in serving rice in the restaurants of Tamil Nadu. They use a dish-mould for serving uniform portions of rice.

Therefore, if considered as one phrase, 'tiraLi muRi' from the usages tiraL or tiraLai (rice ball) and muRi (portion) could also be interpreted as the vessel specified for the purpose of serving rice portions.

But the fact that one word being written from right to left and the other word from left to right brings out the question whether both words could make one phrase.

Probably tiraLi and muRi as discussed earlier are used as synonyms in this instance, individually meaning an equipment of cubic measure. One word was written right to left and the other left to right, keeping the symbols in the middle.

This also means that the symbols or graffiti at the centre were given the foremost importance in the legend and were probably incised first before writing the words in either direction in Brāhmi. Whether the symbols or graffiti have anything to do with the meaning of the words needs further research.

One word written in an unusual way, right to left, beginning from one symbol, and the other word written left to right beginning from the other symbol, may probably mean that there was an effort in the legend to convey that the words in phonetic writing are equivalents to the graffiti.

Megalithic graffiti, the lineage of which is traced back to the Indus Writing, appearing along with phonetic Brāhmi in suggesting ways, that too in combination with Tamil/Dravidian words during the transition period of megalithic into early historic, is a very significant topic for serious further investigation. In fact, the topic is of wider academic significance.

Graffiti in the first line and Brāhmi in the second line. A seal from the Megalithic burial at Aanaikkoaddai, Jaffna. Read from right to left as it is a seal, the Brāhmi legend is deciphered as 'Koveta' (Kō-vēt-a), which in Tamil / Dravidian means: the King's. The three components of the word, which are independently meaningful, may correspond to the three graffiti above. This steatite seal was probably a part of a signet ring. [Image courtesy: Early Settlements in Jaffna, 1987]

Many pottery fragments having legends written in the combination of Brāhmi and graffiti have also been found in the excavations of the megalithic site at Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu by Y. Subbarayalu and K. Rajan. (Subbarayalu. Y., 1988 and 1996, unpublished, cited by Mahadevan. I., ibid., pp. 206-210).

As far as the Tissamaharama find is concerned it may not perhaps mean the presence of a Tamil trade guild but means the presence of ordinary Tamil speaking people in the population.

Dr. P. Ragupathy taught archaeology at the University of Jaffna in the early 1980s, was Professor of South Asian Studies and Head of the Postgraduate Departments at the Utkal University of Culture, Bhubaneswar, and for a brief period served as consultant at the National Centre for Linguistic and Historical Research in the Republic of Maldives. He has authored Early Settlements in Jaffna: An Archaeological Survey (1987), An Etymological Dictionary of Maldivian Island Names (2008) and has co-authored Inscriptions of Maldives Vol I (2005).

Chronology:

Related Articles:

27.06.10 Tamil Brahmi inscription found in Tissamaharama

External Links:

| The Hindu: | An epigraphic perspective on the antiquity of Tamil |

Tissamaharama Tamil Brahmi inscription ‘missing’

[TamilNet, Thursday, 21 October 2010, 19:34 GMT]The third century BCE potsherd inscription in Tamil language and in Tamil Brahmi script found at Tissamaharama in Hambantota district by German excavators is now missing in Sri Lanka’s Archaeology Department, informed sources said. The inscription found sometimes back was not included in the excavation reports of the Archaeology Department. Photo and decipherment of the inscription was brought out by Iravatam Mahadevan in The Hindu in June this year, followed by TamilNet. Meanwhile, accusing TamilNet for false publications, Dr. Susantha Goonatilleke in an article posted by transcurrents.com and published by Daily Mirror said that TamilNet had recently published inscriptions claimed to be from the South of Sri Lanka, which nobody in the Archaeology Department had seen.

Inscribed potsherd from archaeological excavation at Tissamaharama, Hambantota District, Sri Lanka: From left to right the first letter is Li, second one is ra and the third one is ti. From right to left they are read as tiraLi. The fourth and fifth ones are symbols or graffiti marks. The sixth letter is mu and the seventh one is Ri. The last two are read from left to right as muRi. A little away is found a vertical line that perhaps marks the end of the legend. [Image courtesy: Department of Archaeology, Sri Lanka and the academics who sent it]

The article of Susantha Goonatilake, a Sinhalese sociologist, appeared in Daily Mirror with the title “Fictional LTTE archaeology continues” and posted in transcurrents.com run by D.B.S Jeyaraj titled as "Tamilnet site is best witness to the separatist project being lost".

Apart from the photograph appeared in The Hindu, TamilNet has brought out another photograph of the potsherd inscription and a drawing of it made by the German excavator and a staff member of the Archaeology Department. Their names could be found in the drawing. (See image above)

In another instance, TamilNet published a Brahmi inscription still found on a rock at Godawaya temple in Hambantota district and was published by Paranavitana long back, giving the name of the place in Dravidian mixed with Prakrit. (See image on the right)

Some years ago, M S Nagaraja Rao, former Director General of Archaeology of the Archaeological Survey of India is said to have misidentified a megalithic grey ware potsherd found in the island as Painted Gray Ware pottery of the Gangetic plains. It was prestigiously displayed by the Archaeology Department in its museum at Anuradhapura in the 1990s, as an evidence for the arrival of ‘Aryans’. Recently also Nagaraja Rao visited the island for a lecture at the National Museum Auditorium in Colombo.

Whether the Tamil Brahmi potsherd is missing just because it is Tamil Brahmi and whether there will be an open investigation on this, are questions asked in academic circles.

Another complaint of Dr. Susantha Goonatilleke is the news appeared in TamilNet on Sri Lanka Archaeology Department taking over Kanniyaa hot-water springs in Trincomalee, long considered to be a sacred place by the local Hindus who associate them with the Ravana myth.

Of course the Ravana story is a myth, but Mahavamsa is equally a myth, commented academic circles. Colombo that lures tourists from India and other countries in Southeast Asia by showing the Ravana myth in southern Sri Lanka erases it in the North and East only to replace it by the Mahavamsa myth, they pointed out.

Goonatilleke denies the existence of the Siva temple at Trincomalee for which there is a hymn in the Theavaaram of 7th century CE that gives the name of the place as Koa’na-maa-malai. Many medieval literature in Tamil, such as Koa’neasar Kalveddu and Thadcha’na Kailaasa Puraa’nam note that the temple was the predominant religious structure at Trincomalee at that time. For the Portuguese who destroyed it, both a Hindu and a Buddhist structure was a ‘Pagoda’. Goonatilleke says the temple that was destroyed by the Portuguese was Buddhist.

After the war, state sponsored vandals destroyed Saiva temples in worship in Trincomalee such as the historic Siva temple at Kangkuveali.

Goonatilleke says there was no Tamil Buddhism in the North and East and everything was part and parcel of Sinhala Buddhism. His highlight about Kantharoadai in Jaffna, one of the earliest urban centres of the island arose from the basis of Megalithic Culture of South India, is the Kadurugoda Vihara mentioned in the medieval Sinhala literature Nam Potha.

Ironically the Nam Potha cited by him very clearly says that the said Vihara, and many other such places, were in Dema’la Patanama (The city or country of the Tamils).

Buddhist archaeological sites in the North and East and Hindu archaeological sites in the rest of the island, as far south as in the Dondra Head, cannot be contested and that is not the issue. By a deeply entrenched attitude, clearly demonstrated by the majority of the people in the island, the Tamil North and East and the Sinhala South have become two separate nations is the issue and is the reality. People like Dr. Goonatilleke only reflect it, commented an academic in Jaffna.

‘Temporal and spiritual conquest’ was the model set for colonialism in the last 500 years. Dehumanising the people of a land and deny them their ownership are prerequisites and that is what the Sinhala nation is doing to the Tamil nation. When there is Army and Archaeology it is a clear case of genocide, the academic further said.

Goonatilleke says that the Colombo government should stop Jaffna university academics studying their own region.

But, what the Army and Archaeology Department of Colombo are doing in the Tamil land have already been brought out to the outside world by Jeremy Page in The Times, to the chagrin of many a colonial Sinhala academics.

During the height of the war, Dr. Goonatilleke wrote that Colombo government should permanently settle the Army along with their families in the ‘conquered’ land of Tamils and that’s what Colombo is doing now. (See related article at the end, titled 'Vision' of a Sinhala sociologist)

Tamils are not historical owners of any part of the island; they were intruders into the ‘promised land’ of Sinhala-Buddhists and now as Mahinda Rajapaksa has ‘liberated’ the North and East the Sinhala-Buddhists are free to colonise it, is the picture given in the South.

After the war there were many Sinhalese on missionary visits to Jaffna to tell the youth that how once they were Sinhala Buddhists who have now become ‘degrading’ Tamil Saivites – a small twist of the kaleidoscope to show in the North.

Modern missionaries of Sinhala-Buddhist colonialism, armed with ‘Army and Archaeology’ and people like Goonatilleke are small fry, said the Jaffna university academic.

The naked genocide and colonialism committed on the Eezham Tamil nation and the dehumanisation process that is taking place are neither recognized nor stopped by the international community or its international organizations. The powers that dominate them and dehumanise entire humanity are a party to what is happening in the island and they are the real culprits, the academic said, adding that in this respect there is an unholy alliance between Brahmanism and Buddhism of the Establishments in New Delhi and in Colombo in their long-term agenda to subjugate Tamils.

The Sinhala-Buddhist missionaries have now gone beyond the island, into Tamil Nadu, seeking background support.

While Dr. Goonatilleke denies archaeological Buddhist heritage in the North and East to Eezham Tamils of that land, Prof. Sunil Ariyaratne of the University of Sri Jayawardenapura, delivering keynote address at the Mahabodhi Society in Chennai said, “As we are nearing 2600 Buddha Jayanthi, as a Sinhala Buddhist, this is my humble dream for the future: Tamil Buddhist temples should come up in Sri Lanka; Tamil children should embrace Buddhist monkhood; Buddhism must be taught in Tamil; preaching and worshipping Buddhism in Tamil; Tamil Bikkus should have Sinhala followers and Tamil Bhikkus must visit Sinhala homes. That togetherness should be there.”

If needed for socio-political purposes Tamil Nadu can rediscover its own Buddhism without polluting its culture by genocidal Sinhala-Buddhism, the Jaffna academic said.

Tamils becoming Buddhists is not the answer as one could see how the Orientalist-rediscovered Buddhism in the island of Sri Lanka turned genocidal, the academic said.

The Dravidian Movement of Tamil Nadu, which once was the vanguard of secularism of modern Tamil culture, taking it above religions, stopped at only attacking the Brahmins and now it worships the Mammon god. Only a true secularisation of Tamil culture on either side of the Palk Strait would strengthen the Tamil geopolitics against erring Establishments and would arrest genocide and colonialism, the academic further said.

Chronology:

Related Articles:

07.10.10 Colombo takes control of historic Kanniyaa hot wells in Trin..

08.09.10 SL Army, Archaeology dept appropriate lands of uprooted Tami..

24.08.10 Cultural and psychological attack on Tamils in Jaffna

27.04.10 All in the game in the name of archaeology

10.04.10 Army and Archaeology Department at work in Tamil homeland

02.02.10 India plays upon Buddhist emissary while monks colonize Tami..

30.12.09 Heritage genocide abetted by decades of Western funding

10.10.09 Sinhalese Buddhist priest appointed as archaeological curato..

30.06.09 Ploy of Buddhism in nullifying Tamil nationalism

30.01.09 'Vision' of a Sinhala sociologist

03.07.08 Knowledge books mistreat Tamil history

External Links:

| Daily Mirror: | Fictional LTTE archaeology continues |

Ancient port near Hambantota had Dravidian name mixed with Prakrit

[TamilNet, Thursday, 16 September 2010, 18:14 GMT]Jars, Black and Red ware pottery and some timber sections were found in 2008 at a depth of 31 metres under sea, at a probable shipwreck site around 3 km off the coast of Godawaya, between Hambantota and Ambalantota in the Southern Province. Earlier, divers retrieved a stone bench having symbols engraved on it from the site. Stone pillars, probably remains of an old maritime structure were excavated and reported in 2001 at Godawaya fishing village, while a stone anchor was found in the sea near the coast in 2003. A late Brahmi inscription of 2nd century CE found on a rock at the Buddhist temple of Godawaya gives the ancient name of the port as Goda-pavata Patana, which is largely Dravidian mixed with Prakrit.

Rasika Muthucumarana, Maritime Archaeologist of the Maritime Archaeology Unit of the Central Cultural Fund, Galle, wrote an article Monday, “Godawaya: An Ancient Port City (2nd Century CE.) and the Recent Discovery of the Unknown Wooden Wreck”, in archaeology.lk in which he discussed the maritime finds at the site.

He cited the Late Brahmi inscription found at Godawaya, recorded by S. Paranavitana earlier, in which the old name Goda-pavata Patana is found.

“The name Godapawatha, Gota pabbata or Godawaya means, mountain with boulders (Gota – Short and round / Pabbata – Rocky Mountain),” the archaeology.lk article says (see link below).

The interpretation of the place name brought out in the article may need modification and further explanation to understand its significance, an academic comment received by TamilNet said.

The comments follow:

The inscription clearly gives the spelling of the prefix as Goda and not as Gota.

Goda in Sinhala means heap, mass or land at water’s edge. Godæalla in Sinhala is hill, mound or rising ground. Goda is a very popular place name component in Sinhala in the names of places having rocks, hillocks, rocky hills, peaks and banks. In this sense, Goda also means a village or hamlet in Sinhala.

As Goda, in one shade of its meaning stands for land at water’s edge, the verb Godabaanawaa in Sinhala means, to unship, to unload, to land, to disembark etc.

Small stone bench found in the seabed at the site of a probable shipwreck, 31 metres deep and 3km off the coast of Godawaya. [Image courtesy: archaeology.lk]

Koadu was widely used in toponymic context in the Changkam Tamil literature. It is still found in the place names of the extreme south of Tamil Nadu (ex: Vi’lavang-koadu), and more popularly in the Malayalam place names (Ex: Koazhik-koad, Kaasara-goad).

The other component ‘Pavata’ in the name of the ancient port is a Prakrit form of Sanskrit ‘Parvata’, which means a hill or mountain.

The suffix Patana is a cognate of Tamil Paddinam, which means a port, port town, coastal village or small town, and is listed as a Dravidian word (Dravidian Etymological Dictionary 3868).

Goda-pavata Patana, found in the Brahmi inscription as the ancient name for Godawaya, therefore means ‘the port-town of the rock-hill’ or ‘the port-town of the coastal hill’.

It may even simply mean ‘the port of the hillock’ if Goda and Pavata are treated as Dravidian and Prakrit synonyms put together.

Such combinations of synonyms sometimes occur in the languages of South Asia when they are put to usage-influence of Sanskrit / Prakrit. For example: Kal-aal (The banyan tree. Kal in Sanskrit and Aal in Tamil both mean the banyan tree); Gha’ntaa-ma’ni (A bell. Gha’nta in Sanskrit and Ma’ni in Tamil both mean a bell).

The inscription is in Prakrit language and it refers to the donation of the customs duties of the port to the Vihara (Buddhist monastery) at that place by king Gama’ni Abaya.

However, the place name having strong Dravidian elements in it may be suggestive that the substratum was Dravidian and the use of Prakrit in the inscription was the trend of elitism at that time, which was progressing in the replacement of language.

Interestingly, the Prakrit repetition ‘Pavata’ is dropped in the place name today, while the Dravidian ‘Goda’ survives in Godawaya, which means the expanse or stretch of the rocky hillock (Godava-yaaya > Godawaya). Perhaps with the decline of the port the Patana part is also lost.

The rocky hillock at Godawaya facing the coast, where the Buddhist temple and the inscription are located, is 58 meters high, and is the highest spot in the stretch.

Among the finds of the probable shipwreck, the small stone bench has some interesting symbols engraved on it. At the centre of the panel could be found the symbol of Srivatsa, a stylized form of Sri or Lakshmi seated. This symbol is pan South Asian since protohistoric times.

Immediately on either side of Srivatsa in the panel, there are Nandipada (bull head) symbols, then there are fish symbols on either side and finally symbols of ladder on either side. All these symbols are also known as graffiti marks in the megalithic and early historic pottery.

Near Godawaya, at Ridiyagama in the estuary of the river Walawe Ganga, large quantities of Black and Red pottery incised with megalithic graffiti marks were found in the 1990s by Osmund Bopearchchi and other archaeologists.

Many early coins with Tamil Brahmi legends were found at Tissamaharama in the same Hambantota district and some of them were identified as belonging to the Changkam rulers of the ancient Tamil country.

At Tisamaharama an inscribed Black and Red Ware piece, dateable to c. 200 BCE was found in the excavations. The legend in Tamil Brahmi script and Tamil language found on it infers the presence of ordinary people speaking Tamil in that region at that time. But this significant find was not included in the excavation report and was brought to light only recently, when I. Mahadevan wrote on it in June.

Chronology:

Related Articles:

21.07.07 Ællegoda

External Links:

| archelogy.lk: | Godawaya: an ancient port city (2nd Century CE.) and the recent discovery of the unknown wooden wreck |

Palani excavation triggers fresh debate

One of the two underground chambers of the grave was remarkable for the richness of its goods: a skull and skeletal bones, a four-legged jar with two kg of paddy inside, two ring-stands inscribed with the same Tamil-Brahmi script reading “va-y-ra” (meaning diamond) and a symbol of a gem with a thread passing through it, 7,500 beads made of carnelian, steatite, quartz and agate, three pairs of iron stirrups, iron swords, knives, four-legged jars of heights ranging from few centimetres to one metre, urns, vases, plates and bowls. It was obviously a grave that belonged to a chieftain ( The Hindu , June 28, 2009 and Frontline , October 8, 2010).

When K. Rajan, Professor, Department of History, Pondicherry University, excavated this megalithic grave, little did he realise that the paddy found in the four-legged jar would be instrumental in reviving the debate on the origin of the Tamil-Brahmi script. Accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) dating of the paddy done by Beta Analysis Inc., Miami, U.S.A, assigned the paddy to 490 BCE. “Since all the goods kept in the grave including the paddy and the ring-stands with the Tamil-Brahmi script are single-time deposits, the date given to the paddy is applicable to the Tamil-Brahmi script also,” said Dr. Rajan. So the date of evolution of Tamil-Brahmi could be pushed 200 years before Asoka, he argued.

This dating, done on the Porunthal paddy sent to the U.S. laboratory by Dr. Rajan, took the antiquity of the grave belonging to the early historic age to 490 BCE, he said. It held great significance for Tamil Nadu's history, he added. This was the first time an AMS dating was done for a grave in Tamil Nadu.

There are two major divergent views on the date of Tamil-Brahmi.

While scholars such as Iravatham Mahadevan and Y. Subbarayalu hold the view that Tamil-Brahmi was introduced in Tamil Nadu after 3rd century BCE and it is, therefore, post-Asokan, some others including K.V. Ramesh, retired Director of Epigraphy, Archaeological Survey of India (ASI), consider it pre-Asokan.

According to Dr. Rajan, the AMS dating of the Porunthal paddy grains has the following implications: the context of the Tamil-Brahmi goes back to 490 BCE and it is, therefore, pre-Asokan; Tamil Nadu's ancient history can be pushed back to 5th century BCE and it was contemporary to mahajanapadas (kingdoms) such as Avanti, Kosala, Magadha and so on; paddy cultivation goes back to 5th century BCE; and it establishes that the megalithic graves introduced in the Iron Age continued into the early historic times.

When contacted, Mr. Mahadevan, a leading authority on the Tamil-Brahmi and Indus scripts, and Dr. Subbarayalu, Head, Department of Indology, French Institute of Pondicherry, said it was difficult to reach a conclusion on the basis of one single scientific dating.

Mr. Mahadevan described the dating as “interesting” but said “multiple carbon-dates are needed” for confirmation. “If there are several such cases, history has to be re-written because up to now, the scientifically proved earliest date is from Tissamaharama in southern Sri Lanka, where a Tamil-Brahmi script is dated to 200 BCE.” If there is scientific evidence that the paddy is dated to 490 BCE, “we have to sit up and take notice, and wait for confirmation,” Mr. Mahadevan said.

The Asokan-Brahmi is dated to 250 BCE. Megasthenes, the Greek Ambassador to the court of Chandragupta Maurya, Emperor Asoka's grandfather, had stated that the people of Chandragupta Maurya's kingdom did not know how to write and that they depended on memory. Besides, there is no inscription of the pre-Asoka period available. Mr. Mahadevan said: “Supposing a large number of carbon-datings are available from various sites, which will take us to the period of the Mauryas and even the Nandas, we can consider. But to push [the date of the origin of the Tamil-Brahmi script] a couple of centuries earlier with a single carbon-dating is not acceptable because chances of contamination and error are there.”

Dr. Subbarayalu also argued that on the basis of one single scientific dating, it was difficult to reach the conclusion that Tamil-Brahmi was pre-Asokan. There should be more evidence to prove that Tamil-Brahmi was earlier to the time of Asoka, in whose time was available the earliest Brahmi script in north India.

Mr. Mahadevan's conclusion that Tamil-Brahmi is post-Asokan and it had its advent from about the middle of the third century BCE is based on “concrete archaeological as well as palaeographical grounds” and this date is as yet the most reasonable one, in spite of minor points of difference on his dating of individual inscriptions, said Dr. Subbarayalu.

The date of the Tamil-Brahmi script found at Porunthal, on palaeographic basis, could be put only in the first century BCE/CE and “cannot be pushed back to such an early date [490 BCE].” The three letters “va-y-ra” found on the ring-stands were developed and belonged to the second stage of Mr. Mahadevan's dating of Tamil-Brahmi. “It is premature to revise the Tamil-Brahmi dating on the basis of a single carbon date, which is governed by complicated statistical probabilities,” Dr. Subbarayalu said. The word “vayra” is an adapted name from the Prakrit or Sanskrit “vajra” and it is difficult to explain convincingly the generally dominant Prakrit element in Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions found on rock and pot-sherds if Tamil-Brahmi is indigenous and pre-Asokan and transported from south India to north India, he says.

On the other hand, Dilip K. Chakrabarti, Emeritus Professor, Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, called the Porunthal Tamil-Brahmi script “an epoch-making discovery in the archaeology of Tamil Nadu” and said there “is no doubt” that Tamil-Brahmi belonged to the pre-Asokan period. In two of his books — “An Oxford Companion to Indian Archaeology” and “India, an Archaeological History” — he had written that the evolution of Tamil-Brahmi should go back to circa 500 BCE.

He refuted the theory that Tamil-Brahmi was post-Asokan.

Dr. Ramesh, who retired as the ASI's Joint Director-General in 1993, said the Porunthal scientific dating strengthened the argument that Tamil-Brahmi was pre-Asokan. He dismissed the assessment that Tamil-Brahmi was post-Asokan as “the argument of people who say that there cannot be pre-Asokan inscriptions.” “How can you question the scientific dating given by an American laboratory?” Dr. Ramesh said the Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions found at Mankulam, near Madurai, were pre-Asokan. [The Mankulam inscriptions are the earliest Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions and they are dated to second century BCE]. “The consonants in the Mankulam inscriptions do not have vowel value attached to them. They are pre-Asokan and the script is more rudimentary than the Asokan-Brahmi,” he claimed.

The date given by the American laboratory was “a wonderful result,” said M.R. Raghava Varier, former Professor, Department of History, Calicut University, “because the earliest date given so far to a south Indian site was 300 BCE.” The archaeological sites of Uraiyur in Tamil Nadu and Arikkamedu in Puducherry fell within the time-limit of 300 BCE and Arikkamedu belonged to a later period than Uraiyur. While the [pre-Asokan] date given to a Tamil-Brahmi inscription found at Anuradhapura in Sri Lanka “has not been proved convincingly,” there was “a convincing date” at Porunthal and it was based on a scientific dating system, said Professor Varier, who was the honorary Editor of Kerala Archaeological Series. Its importance lay in the fact that while the Asokan-Brahmi began in the 3rd century BCE, the Porunthal script could be dated to 5th century BCE, he says. “But we cannot argue that Brahmi was invented by the southern people. That is a different issue.”