This monograph presents evidence from Indus Script Corpora attesting to the migrations of artisans and seafaring merchants -- Meluhha language-speakers -- into and interactions with people settled along Persian Gulf & in Ancient Near East.

This monograph claims that Out of India theory is evidenced because most of the etyma are traceable to rebus Meluhha readings of over 8000 inscriptions. The messages of inscriptions relate to metalwork, lapidary lexemes -- of neolithic and bronze age phases of civilization story -- still in use and traceable among lexemes of Ancient Indian language (so-called Proto-Prakrtam, Proto-Indo-Aryan, Munda, Dravidian etyma which constitute Indian sprachbund, 'language union'). (Evidence in Indian lexicon, a comparative dictionary of 8000 + semantic clusters of Ancient Indian Languages):

A good example is provided linking Indian sprachbund with PIE: med'copper' (Slavic languages); mẽṛhẽt, meḍ ‘iron’ (Mu.Ho.)meḍ 'iron' (Mundari.Remo); muṇḍa मुण्ड 'iron' mṛdu मृदु 'a kind of iron; -कार्ष्णायसम्, -कृष्णायसम् soft-iron, lead. '(Apte.Samskrtam) A rebus rendering for this ancient form is: मृद्वी f. a vine with red grapes L. (cf. मृद्वीका). This rebus Meluhha representation is evidenced in a stunning Bharhut sculpture ca. 3rd cent. BCE of a Greek soldier holding a broad-sword with Indus Script hypertext and grapevine hieroglyph.

Greek soldier is an iron smelter, an artificer in a laterite, ferrite ore sword, metal casting mint. मृदु mṛdu khaṇḍaka kammaṭi 'iron, laterite, sword mint'. Thus, Bharhut was a metals armoury,mint town with metalwork artificers and blacksmiths..

Bharhut Yavana, Greek soldier of Bharhut; did the Yavana soldier sculpted by the śilpin, 'sculptor' speak Meluhha?

The broad sword held on his leftr hand has an Indus Script Hypertext: Fish-fin pair atop a round pebble. The hypertext Meluhha readings are: khambhaṛā 'fish-fin' rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner.(DEDR 1236) PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS Hieroglyph: seed, something round: *gōṭṭa ʻ something round ʼ. [Cf. guḍá -- 1. -- In sense ʻ fruit, kernel ʼ cert. ← Drav., cf. Tam. koṭṭai ʻ nut, kernel ʼ, Kan. goṟaṭe &c. listed DED 1722]K. goṭh f., dat. °ṭi f. ʻ chequer or chess or dice board ʼ; S. g̠oṭu m. ʻ large ball of tobacco ready for hookah ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ small do. ʼ; P. goṭ f. ʻ spool on which gold or silver wire is wound, piece on a chequer board ʼ; N. goṭo ʻ piece ʼ, goṭi ʻ chess piece ʼ; A. goṭ ʻ a fruit, whole piece ʼ, °ṭā ʻ globular, solid ʼ, guṭi ʻ small ball, seed, kernel ʼ; B. goṭā ʻ seed, bean, whole ʼ; Or. goṭā ʻ whole, undivided ʼ, goṭi ʻ small ball, cocoon ʼ, goṭāli ʻ small round piece of chalk ʼ; Bi. goṭā ʻ seed ʼ; Mth. goṭa ʻ numerative particle ʼ; H. goṭf. ʻ piece (at chess &c.) ʼ; G. goṭ m. ʻ cloud of smoke ʼ, °ṭɔ m. ʻ kernel of coconut, nosegay ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ lump of silver, clot of blood ʼ, °ṭilɔ m. ʻ hard ball of cloth ʼ; M. goṭā m. ʻ roundish stone ʼ, °ṭī f. ʻ a marble ʼ, goṭuḷā ʻ spherical ʼ; Si. guṭiya ʻ lump, ball ʼ; -- prob. also P. goṭṭā ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ, H. goṭā m. ʻ edging of such ʼ (→ K. goṭa m. ʻ edging of gold braid ʼ, S. goṭo m. ʻ gold or silver lace ʼ); M. goṭ ʻ hem of a garment, metal wristlet ʼ.*gōḍḍ -- ʻ dig ʼ see *khōdd -- .Addenda: *gōṭṭa -- : also Ko. gōṭu ʻ silver or gold braid ʼ.(CDIAL 4271) Ta. koṭṭai seed of any kind not enclosed in chaff or husk, nut, stone, kernel; testicles; (RS, p. 142, items 200, 201) koṭṭāṅkacci, koṭṭācci coconut shell. Ma. koṭṭakernel of fruit, particularly of coconut, castor-oil seed; kuṟaṭṭa, kuraṭṭa kernel; kuraṇṭi stone of palmfruit. Ko. keṭ testes; scrotum. Ka. koṭṭe, goṟaṭe stone or kernel of fruit, esp. of mangoes; goṭṭa mango stone. Koḍ. koraṇḍi id. Tu. koṭṭè kernel of a nut, testicles; koṭṭañji a fruit without flesh; koṭṭayi a dried areca-nut; koraṇtu kernel or stone of fruit, cashew-nut; goṭṭu kernel of a nut as coconut, almond, castor-oil seed. Te. kuriḍī dried whole kernel of coconut. Kol. (Kin.) goṛva stone of fruit. Nk. goṛage stone of fruit. Kur. goṭā any seed which forms inside a fruit or shell. Malt. goṭa a seed or berry. / Cf. words meaning 'fruit, kernel, seed' in Turner, CDIAL, no. 4271 (so noted by Turner).(DEDR 2069) Rebus: khōṭa 'alloy ingot' (Marathi) gota (laterite)

The ligatured pair of fish-fins is above a dotted circle. A dotted circle signifies

dhāvaḍ 'smelter'; see: dhāv 'mineral' vaḍ 'circle' rebus dhāvaḍ 'smelter' Caduceus, śúlba 'string' rebus शुल्बम् 'copper' on kārṣāpaṇa & other symbols of ancient India coins are Indus Script hieroglyphs to signify metals wealth-accounting ledgers,mintwork catalogues of آهن ګر āhangar 'blacksmith'

Hieroglyph: sword: *khaṇḍaka3 ʻ sword ʼ. [Perh. of same non -- Aryan origin as khaḍgá -- 2]Pk. khaṁḍa -- m. ʻ sword ʼ (→ Tam. kaṇṭam), Gy. SEeur. xai̦o, eur. xanro, xarno, xanlo, wel. xenlī f., S. khano m., P. khaṇḍā m., Ku. gng. khã̄ṛ, N. khã̄ṛo, khũṛo (X churi < kṣurá -- ); A. khāṇḍā ʻ heavy knife ʼ; B. khã̄rā ʻ large sacrificial knife ʼ; Or. khaṇḍā ʻ sword ʼ, H. khã̄ṛā, G. khã̄ḍũ n., M. khã̄ḍā m., Si. kaḍuva.(CDIAL 3793).

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/d/d8/Bharhut_Stupa_Yavana_symbolism.jpg/250px-Bharhut_Stupa_Yavana_symbolism.jpg

The top of the Greek soldier of Bharhut has an inscription.classified as Inscription 55 in the Pillars of Railing of the SW Quadrant at Bharhut (The Stupa of Bharhut, Cunningham, p. 136), is in the Brahmi script and reads from left to right:

Inscription 55 in the Pillars of Railing of the SW Quadrant at Bharhut.

Transliteration and translation: "Bhadanta Mahilasa thabho dânam"

"Pillar-gift of the lay brother Mahila."

— Inscription of the Bharhut Yavana

The role of the stading warrior is that of a dvarapala, deities who were Guardians of a temple gate.Many elements point to the depiction being that of a foreigner, and possibly an Indo-Greek, called a Yavana among the Indians of the period. Elements leading to this suggestion are the hairstyle (short curly hairstyle without an Indian turban), the hair band normally worn by Indo-Greek kings on their coins, the tunic, and boots. In his right hand he holds a grape plant, possibly emblematic of his origin. The sheath of his broadsword is decorated with a srivasta or nandipada, symbols of Bhauddham.He is holding in his right hand a vine...This type of head with the band of a Greek king is also seen on reliefs at Sanchi, in which man in northern dress are seen riding horned and winged lions. It has been suggested that the warrior is actually the Indo-Greek king Menander who may have conquered Indian territory as far as Pataliputra and is known through the Milinda Panha to have converted to Buddhism "The Diffusion of Classical Art in Antiquity, John Boardman, 1993, p.112 Note 90 Buddhist Art & Antiquities of Himachal Pradesh, Upto 8th Century A.D., Omacanda Hāṇḍā, Indus Publishing, 1994 p.48 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bharhut_Yavana

| The Bharhut Yavana. | |

| Material | Red sandstone |

|---|---|

| Period/culture | c. 100 BCE |

| Discovered | 24°27′00″N 80°55′00″E |

| Place | Bharhut, India. |

| Present location | Mathura Museum |

The monograph demonstrates that the Indus Script inscriptions are read rebus in Meluhha parole (or spoken forms of dialects of Indian sprachbund, 'language union'), principally along the 2000 settlements of the civilization along Sarasvati River Basin. These 2000 settlements are out of over 2600 settlements of the so-called Harappan or Sarasvati Civilization of the Neolithic & Bronze Ages, from 8th millennium BCE. (Carbon-14 dating attested by the continuous layers of settlement of Bhirrana of Sarasvati River Basin and of Mehrgarh in Baluchistan).

This evidence tends to support the Out of India Theory (OIT) proposed as a counter to Aryan Tourist Theories (ATT, AMT, AIT) while reinforcing the insights provided by the PIE studies attesting to the Indo-European continuum in Indo-Aryan languages. This continuum is most pronounced in Meluhha etyma which constitute the core of Indian sprachbund, 'language union' with particular reference to wealth-creation acivities of artisans and seafaring merchants during the Bronze Age documented in Indus Script Corpora which now exceeds 8000 inscriptions.

This renewed attempt to decipher the inscription on the bilingual (Sumerian and Proto-Indian) Ur (?) stamp seal starts with a hypothesis that the cuneiform sign readings as: SAG KUSIDA.

Reading of field symbol: The ox is read rebus in Meluhha as: barad, barat'ox' Rebus: भरत (p. 603) [ bharata ] n A factitious metal compounded of copper, pewter, tin &c. The gloss bharata denoted metalcasting in general leading to the self-designation of metalworkers in Rigveda as Bharatam Janam, lit. metalcaster folk.

Pre-Sargonic period bilingual stamp seal from Ur -- of a Meluhha merchant? -- with Indus Script inscription

Note: Sargon of Akkad also known as Sargon the Great, was the first ruler of the Akkadian Empire, known for his conquests of the Sumerian city-states in the 24th to 23rd centuries BCE.

Bronze head of an Akkadian ruler -- made using cire-purdue (lost-wax technique)--, discovered in Nineveh in 1931, presumably depicting either Sargon or Sargon's grandson Naram-Sin (M. E. L. Mallowan, "The Bronze Head of the Akkadian Period from Nineveh", Iraq Vol. 3, No. 1 (1936), 104–110.)

Bronze head of an Akkadian ruler -- made using cire-purdue (lost-wax technique)--, discovered in Nineveh in 1931, presumably depicting either Sargon or Sargon's grandson Naram-Sin (M. E. L. Mallowan, "The Bronze Head of the Akkadian Period from Nineveh", Iraq Vol. 3, No. 1 (1936), 104–110.)The find of an Indus Script inscription dated perhaps to a pre-Sargonic period, i.e. prior to 25th cent. BCE is remarkable and attests to the presence of migrating seafaring merchants from Meluhha in Sumeria (or, Old Akkad).

"Before the decipherment of cuneiform in the 19th century, the city was known only from a single reference in Genesis 10:10The name is spelled logographically as URIKI, or phonetically as a-ga-dèKI, variously transcribed into English as Akkad, Akkade or Agade.

The etymology of the name is unclear, but not of Akkadian (Semitic) origin. Various suggestions have proposed Sumerian, Hurrian or Lullubean etymologies.

The non-Akkadian origin of the city's name suggests that the site may have already been occupied in pre-Sargonic times, as also suggested by the mentioning of the city in one pre-Sargonic year-name. where it is written אַכַּד ( 'Akkad), rendered in the KJV as Accad. The name is given in a list of cities of Nimrod in Sumer (Shinar)...."(Wall-Romana 1990, pp. 205–206; Wall-Romana, Christophe (1990), "An Areal Location of Agade", Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 49 (3): 205–245,)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Akkad_(city) A homonymous word attested in Rgveda is: अ-गद mfn. free from disease, healthy RV.

Goddess Ishtar on an Akkadian seal, 2350-2150 BCE.

Akkadian Empire

Akkadian Empirec. 2334 – 2154 BCE Map of the Akkadian Empire (brown) and the directions in which military campaigns were conducted (yellow arrows) " The Akkadian Empire exercised influence across Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Anatolia, sending military expeditions as far south as Dilmun and Magan (modern Bahrain and Oman) in the Arabian Peninsula."(Mish, Frederick C., Editor in Chief. "Akkad" Webster’s Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary. ninth ed. Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster 1985)

-- Sag kusida, 'chief money-lender' for bharata, 'metalcasters' -- cuneiform text on an Indus seal of Ur including Sag, a borrowed word from Sumerian and kusida as a Meluhha word PLUS hieroglyph 'ox' read rebus in Meluhha as bharata, 'metal alloy of copper, pewter, tin'.

SAG 'warrior, chief' (Sumerian) PLUS kusida, 'chief money-lender' कुसीद kusīda, mf. a money-lender, usurer L.(Monier-Williams)

Field symbol, alternative decipherment: dhanga 'bull' Rebus: dhangar The seal may be a dhamma samjna ‘responsibility indicator’, a professional badge to signify ‘moneylender of metalworkers’ guild’.

Gadd Seal 1 Seal impression and reverse of seal (with pierced lug handle) from Ur (U.7683; BM 120573); image of bison and cuneiform inscription; length 2.7, width 2.4, ht. 1.1 cm. cf. Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 5-6, pl. I, no.1; Mitchell 1986: 280-1 no.7 and fig. 111; Parpola, 1994, p. 131: signs may be read as (1) sag(k) or ka, (2) ku or lu or ma, and (3) zi or ba (4)?. SAG.KU(?). IGI .X or SAG.KU(?).P(AD)(?) The commonest value: sag-ku-zi Rebus: sang m. ʻ union ʼ(Kashmiri)(CDIAL 13382)

Procedure and analyses ofdecipherment are presented in Annex A.

Imported Indian seal from Tell Asmar

Cylinder seal impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register]

Tell Asmar Cylinder seal modern impression [elephant, rhinoceros and gharial (alligator) on the upper register] bibliography and image source: Frankfort, Henri: Stratified Cylinder Seals from the Diyala Region. Oriental Institute Publications 72. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, no. 642. Museum Number: IM14674 3.4 cm. high. Glazed steatite. ca. 2250 - 2200 BCE. Imported Indian seal from Tell Asmar. "The Indus civilization used the signet, but knew the cylinder seal. Whether the five tall ivory cylinders [4] tentatively explained as seals in Sir John Marshall's work were used for that purpose remains uncertain. They have nothing in common with the seal cylinders of the Near East. In the upper layers of Mohenjo Daro, however, three cylinder seals were found [2,3]. The published specimen shows two animals with birds upon their backs [2], a snake and a small conventional tree. It is an inferior piece of work which displays none of the characteristics of the finely engraved stamp-seals which are so distinctive a feature of early Indian remains. Another cylinder of glazed steatite was discovered at Tell Asmar in Iraq, but here the peculiarities of design, as well as the subject, show such close resemblances to seals from the Indus valley that its Indian origin is certain [3]. The elephant, rhinoceros and crocodile (gharial), foreign to Babylonia, were obviously carved by an artist to whom they were familiar, as appears from the faithful rendering of the skin of the rhinoceros (closely resembling the plate-armour) and the sloping back and bulbous forehead of the elephant. Certain other peculiarities of style connect the seal as definitely with the Indus civilisation as if it actually bore the signs of the Indus script. Such is the convention by which the feet of the elephant are rendered and the network of lines, in other Indian seals mostly confined to the ears, but extending here over the whole of his head and trunk. The setting of the ears of the rhinoceros on two little stems is also a feature connecting this cylinder with the Indus valley seals." (H. Frankfort, Cylinder Seals, Macmillan and Co., 1939, p. 304-305.)

https://www.harappa.com/blog/indus-cylinder-seals Indus Script hypertexts: karibha, ibha 'elephant' rebus: karba, ib 'iron'ibbo'merchant'; kāṇḍa 'rhinoceros' rebus: kaṇḍa 'implements'; karā 'crocodile' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'.

Seal of dhā̆vaḍ 'iron-smelter', kolimi 'smithy, forge, temple', kuṭhi 'smelter' (producing wealth proucts of) dul mūhā mẽṛhẽt 'cast iron ingots'

mūhā parenthesis/split ellipse (orthography), signifies rebus: mūhā 'ingot' (semantics). mūhā mẽṛhẽt = iron smelted by the Kolhes and formed into an equilateral lump a little pointed at each of four ends (Santali)

Three lines on the boss of seal: kolom'thre' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge'

Ligatures to fish: parentheses + snout dul mūhā kuṭila ayas 'cast bronze ayas alloy with tuttha, copper sulphate ingot.'

Modifier hieroglyph: 'snout' Hieroglyph: WPah.kṭg. ṭōṭ ʻ mouth ʼ.WPah.kṭg. thótti f., thótthəṛ m. ʻ snout, mouth ʼ, A. ṭhõt (phonet. thõt) (CDIAL 5853). Semantics, Rebus:

tutthá n. (m. lex.), tutthaka -- n. ʻ blue vitriol (used as an eye ointment) ʼ Suśr., tūtaka -- lex. 2. *thōttha -- 4 . 3. *tūtta -- . 4. *tōtta -- 2 . [Prob. ← Drav. T. Burrow BSOAS xii 381; cf. dhūrta -- 2 n. ʻ iron filings ʼ lex.]1. N. tutho ʻ blue vitriol or sulphate of copper ʼ, B. tuth.2. K. thŏth, dat. °thas m., P. thothā m.3. S.tūtio m., A. tutiyā, B. tũte, Or. tutiā, H. tūtā, tūtiyā m., M. tutiyā m. 4. M. totā m.(CDIAL 5855) Ka. tukku rust of iron; tutta, tuttu, tutte blue vitriol. Tu. tukků rust; mair(ů)suttu, (Eng.-Tu. Dict.) mairůtuttu blue vitriol. Te. t(r)uppu rust; (SAN) trukku id., verdigris. / Cf. Skt. tuttha- blue vitriol (DEDR 3343).

Modifier hieroglyph: 'snout' Hieroglyph: WPah.kṭg. ṭōṭ ʻ mouth ʼ.WPah.kṭg. thótt |

Gadd has demonstrated how an ellipse may be broken into parenthesis marks contituting hieroglyph component pair. His insight is that an ellipse split into parenthesis of two curved lines ( ) signifies hieroglyph writing. I suggest that the hieroglyph components signify the orthography which matches an 'ingot' formation -- a four-cornered ellipse a little pointed at each end.

On Indus Script Corpora, mūhā parenthesis/split ellipse (orthography), 'ingot' (semantics) is elaborated as an example of a gloss matching orthography of a writing system with the semantics of an underlying language -- Prakritam.

Dotted circles on the boss of the seal:

Dotted circles is a hypertext of dots + circle. dhā + vaṭṭa read together as dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻa caste of iron-smeltersʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to ironʼ).

Circle is vaṭṭa (Pali): वृत्त round , rounded , circular (शतपथ-ब्राह्मण); a circle (गणिताध्याय) vr̥ttá ʻ turned ʼ RV., ʻ rounded ʼ ŚBr. 2. ʻ completed ʼ MaitrUp., ʻ passed, elapsed (of time) ʼ KauṣUp. 3. n. ʻ conduct, matter ʼ ŚBr., ʻ livelihood ʼ Hariv. [√vr̥t 1 ] 1. Pa. vaṭṭa -- ʻ round ʼ, n. ʻ circle ʼ; Pk. vaṭṭa -- , vatta -- , vitta -- , vutta -- ʻ round ʼ; L. (Ju.) vaṭ m. ʻ anything twisted ʼ; Si. vaṭa ʻ round ʼ, vaṭa -- ya ʻ circle, girth (esp. of trees) ʼ; Md. va'ʻ round ʼ GS 58; -- Paš.ar. waṭṭəwīˊk, waḍḍawik ʻ kidney ʼ ( -- wĭ̄k vr̥kká -- ) IIFL iii 3, 192? 2. Pk. vaṭṭa -- , vatta -- , vitta -- , vutta -- ʻ passed, gone away, completed, dead ʼ; Ash. weṭ -- intr. ʻ to pass (of time), pass, fall (of an avalanche) ʼ, weṭā -- tr. ʻ to pass (time) ʼ; Paš. wiṭīk ʻ passed ʼ; K.ḍoḍ. buto ʻ he was ʼ; P. batāuṇā ʻ to pass (time) ʼ; Ku. bītṇo ʻ to be spent, die ʼ, bitauṇo ʻ to pass, spend ʼ; N. bitāunu ʻ to pass (time), kill ʼ, butāunu ʻ to extinguish ʼ; Or. bitibā intr. ʻ to pass (of time), bitāibā tr.; Mth. butāb ʻ to extinguish ʼ; OAw. pret. bītā ʻ passed (of time) ʼ; H. bītnā intr. ʻ to pass (of time) ʼ, butnā ʻ to be extinguished ʼ, butānā ʻ to extinguish ʼ; G. vĭ̄tvũ intr. ʻ to pass (of time) ʼ, vatāvvũ tr. ʻ to stop ʼ.3. Pa. vatta -- n. ʻ duty, office ʼ; Pk. vaṭṭa -- , vatta -- , vitta -- , vutta -- n. ʻ livelihood ʼ; P. buttā m. ʻ means ʼ; Ku. buto ʻ daily labour, wages ʼ; N. butā ʻ means, ability ʼ; H. oūtām. ʻ power ʼ; Si. vaṭa ʻ subsistence, wages ʼ.(CDIAL 12069)*ardhavr̥tta ʻ half -- completed ʼ. [ardhá -- 2 , vr̥ttá -- ]G. adhoṭ ʻ past middle age ʼ (CDIAL 673).

Mirror: http://tinyurl.com/hq2qpve

dhāī˜ (Lahnda) signifies a single strand of rope or thread.

dhāī˜ (Lahnda) signifies a single strand of rope or thread.

I havesuggested that N. dhāu ʻ ore (esp. of copper) ʼ; Or. ḍhāu ʻ red chalk, red ochre ʼ (whence ḍhāuā ʻ reddish ʼ; M. dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ (whence dhā̆vaḍ m. ʻ a caste of iron -- smelters ʼ, dhāvḍī ʻ composed of or relating to iron ʼ) is related to the hieroglyph: strand of rope: S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f.(CDIAL 6773) తాడు [ tāḍu ] or త్రాడు tādu. [Tel.] n. A cord, thread, string. दामन् n. [दो-मनिन्] 1 A string, thread, fillet, rope.

I have suggested that a dotted circle hieroglyph is a cross-section of a strand of rope: S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻsubstance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour)ʼ; dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ(Marathi) धवड (p. 436) [ dhavaḍa ] m (Orधावड ) A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron (Marathi). Hence, the depiction of a single dotted circle, two dotted circles and three dotted circles (called trefoil) on the robe of the Purifier priest of Mohenjo-daro.

The phoneme dhāī˜ (Lahnda) signifying a single strand may thus signify the hieroglyph: dotted circle. This possibility is reinforced by the glosses in Rigveda, Tamil and other languages of Baratiya sprachbund which are explained by the word dāya 'playing of dice' which is explained by the cognate Tamil word: தாயம் tāyam, n. < dāya Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண்.

I have suggested that a dotted circle hieroglyph is a cross-section of a strand of rope: S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻsubstance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour)ʼ; dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ(Marathi) धवड (p. 436) [ dhavaḍa ] m (Or

The phoneme dhāī˜ (Lahnda) signifying a single strand may thus signify the hieroglyph: dotted circle. This possibility is reinforced by the glosses in Rigveda, Tamil and other languages of Baratiya sprachbund which are explained by the word dāya 'playing of dice' which is explained by the cognate Tamil word: தாயம் tāyam, n. < dāya Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண்.

Seal impression, Ur (Upenn; U.16747); dia. 2.6, ht. 0.9 cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 11-12, pl. II, no. 12; Porada 1971: pl.9, fig.5; Parpola, 1994, p. 183; water carrier with a skin (or pot?) hung on each end of the yoke across his shoulders and another one below the crook of his left arm; the vessel on the right end of his yoke is over a receptacle for the water; a star on either side of the head (denoting supernatural?). The whole object is enclosed by 'parenthesis' marks. The parenthesis is perhaps a way of splitting of the ellipse (Hunter, G.R., JRAS, 1932, 476). An unmistakable example of an 'hieroglyphic' seal.

Mesopotamian seals in Frankfort with Indus Seal indicators

Dilmun seal from Bahrain.

cylinder seal with six signs,found in 'Swat and Seistan', unrolled photographically and the unbroken stamp-end of the seal; positive impression of the cylinder showing Harappan inscriptions (Robert Knox, 1994, A new Indus Valley Cylinder Seal, pp. 375-378 in: South Asian Archaeology 1993, Vol. I, Helsinki)

The triangle motif is similar to the motif shown on M-443B.

Possible connection with Sibri cylinder seals (which show (i) a zebu and a lion and image of a scorpion on the flat end (Shah and Parpola 1991: 413); and (ii) a zebu bull with a geometric pattern of triangles and a circle at the stamp end).

"The Seistan findspot of this seal is of great interest. Evidence exists for the movement of Indus commodities, and, therefore, Indus commercial activities in the direction of western Asia and, in return, from there to the Indus world.. Evidence for the Harappan penetration of Seistan and farther to southeastern Iran is scanty but includes at least one other Indus inscription from an impression of a sherd discovered at Tepe Yahya, period IV A (c. 2200 BC) (Lamberg- Karlovsky and Tosi 1973: pl. 137)" (Knox, p. 377).

Cylinder seal impression; scene representing mythological beings, bullls and lions in conflict (British Museum No. 89538).

Cylinder seal impression, Mesopotamia [Scene representing Gilgamesh and Ea-bani in conflict with bulls in a wooded and mountainous country; British Museum No. 89308] Image parallels:

Yale tablet. Bull's head (bucranium) between two seated figures drinking from two vessels through straws. YBC. 5447; dia. c. 2.5 cm. Possibly from Ur. Buchanan, studies Landsberger, 1965, p. 204; A seal impression was found on an inscribed tablet (called Yale tablet) dated to the tenth year of Gungunum, King of Larsa, in southern Babylonia--that is, 1923 B.C. according to the most commonly accepted ('middle') chronology of the period. The design in the impression closely matches that in a stamp seal found on the Failaka island in the Persian Gulf, west of the delta of the Shatt al Arab, which is formed by the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers.

Failaka seal. The Yale tablet is dated to ca. the second half of the twentieth century B.C.... Trade3 on the Persian gulf was in existence well before that time-- about 2350 B.C.-- when Sargon, the first Akkadian king referred to ships from or destined for Melukhkha, Magan and Tilmun (Dilmun) at his wharves. in the Third Dynasty of Ur (around 2000), when trade apparently was centred at Magan. It is even better documented on other tablets from Ur (from about 1900 and from about 1800), belonging to various kings of Larsa. At this time the trade was centered at Tilmun... Cuneiform inscriptions naming Inzak, the god of Tilmun, were found on Failaka and, a long time ago, one on Bahrein... Failaka can be equated with Tilmun, or at least was an important part of it. (Briggs Buchanan, A dated seal impression connecting Babylonia and ancient India, Archaeology, Vol. 20, No.2, 1967, pp. 104-107).

Seal; UPenn; cf. Philadelphia Museum Journal, 1929; ithyphallic bull-men; the so-called 'Enkidu' figure common upon Babylonian cylinders of the early period; all have horned head-dresses; moon-symbols upon poles seem to represent the door-posts that the pair of 'twin' genii are commonly seen supporting on either side of a god; material and shape make it the 'Indus' type while the device is Babylonian.

Seal; BM 122841; dia. 2.35; ht. 1 cm.; Gadd PBA 18 (1932), p. 12, pl. II, no. 13; circle with centre-spot in each of four spaces formed by four forked branches springing from the angles of a small square. Alt. four stylised bulls' heads (bucrania) in the quadrants of an elaborate quartering device which has a cross-hatched rectangle in the centre.

Seal impression; UPenn; steatite; bull below a scorpion; dia. 2.4cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), p. 13, Pl. III, no. 15; Legrain, MJ (1929), p. 306, pl. XLI, no. 119; found at Ur in the cemetery area, in a ruined grave .9 metres from the surface, together with a pair of gold ear-rings of the double-crescent type and long beads of steatite and carnelian, two of gilt copper, and others of lapis-lazuli, carnelian, and banded sard. The first sign to the left has the form of a flower or perhaps an animal's skin with curly tail; there is a round spot upon the bull's back.

Seal; UPenn; a scorpion and an elipse [an eye (?)]; U. 16397; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 10-11, pl. II, no. 11

Seal; BM 122945; U. 16181; dia. 2.25, ht. 1.05 cm; Gadd PBA 18 (1932), p. 10, pl. II, no. o; each of four quadrants terminates at the edge of the seal in a vase; each quadrant is occupied by a naked figure, sitting so that, following round the circle, the head of one is placed nearest to the feet of the preceding; two figures clasp their hands upon their breasts; the other two spread out the arms, beckoning with one hand.

koṭhāri 'crucible' Rebus: koṭhāri 'treasurer' kuThAru 'armourer'

मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda)

करडूं karaḍū 'kid' rebus karaḍā 'hard alloy' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' meD 'body' rebus: med 'iron' meṛha, meḍhi ‘merchant’s clerk; (Gujarati) kAraNika 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'Supercargo'-- a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale. Thus, a supercargo (controlling) cast metal..

The relatively more frequent use on Dilmun seals this hieroglyph-multiplex of ‘twins’ is explained, not as a prefix but as a pairing device to signify dula ‘pair’ rebus: dul ‘cast metal’. Thus, in Dilmun area where the seals were inscribed and used, there was activity of producing metalcastings. The explicit use of the short-horned bull is also explained by the production of hard alloys: barad, balad ‘ox’ rebus: bharata ‘hard alloy of pewter, copper, tin’.

I submit that there was no distancing from the Indus Script tradition, but was a continuum on Dilmun seals by the artisans and merchants who had been conversant with the writing system tradition using rebus rendering of Prakrtam words to signify metalwork and create catalogues by inscribing on seals and seal impressions. The presence of Meluhhan settlements in the nearby contact areas of Elam/Sumer also explains why some Sumerian motifs also occur on the corpus of Dilmun seal inscriptions.

Many Dilmun seals are deciphered in this monograph as a continuum of the tradition of Indus Script Corpora to create hypertext data mines of metalwork catalogues to document and promote authenticated trade transactions across the Ancient Near East.

The presence of Meluhha settlements in Ancient Near East is attested in cuneiform texts. this finds confirmation in an ancient text. The ancient text is also the basis for suggesting the presence of Indian sprachbund speakers in Dilmun to create the Dilmun seals.

Baudhāyana śrautasūtra 18.44 which documents migrations of Āyu and Amavasu from a central region:

pran Ayuh pravavraja. tasyaite Kuru-Pancalah Kasi-Videha ity. etad Ayavam pravrajam. pratyan amavasus. tasyaite Gandharvarayas Parsavo ‘ratta ity. etad Amavasavam

Trans. Ayu went east, his is the Yamuna-Ganga region (Kuru-Pancala, Kasi-Videha). Amavasu went west, his is Gandhara, Parsu and Araṭṭa.

Ayu went east from Kurukshetra to Kuru-Pancala, Kasi-Videha. The migratory path of Meluhha artisand in the lineage of Ayu of the Rigvedic tradition, to Kasi-Videha certainly included the very ancient temple town of Sheorajpur of Dist. Etawah (Kanpur), Uttar Pradesh.

I, therefore, conclude that the Indus Script tradition of rebus signifiers using hieroglyphs continued on Dilmun seals indicating the possibility that the creators and users of the Dilmun seals were speakers from the Indian sprachbund (language union).

koṭhāri 'crucible' Rebus: koṭhāri 'treasurer' kuThAru 'armourer'

मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda)

करडूं karaḍū 'kid' rebus karaḍā 'hard alloy' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' meD 'body' rebus: med 'iron' meṛha, meḍhi ‘merchant’s clerk; (Gujarati) kAraNika 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'Supercargo'-- a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale. Thus, a supercargo (controlling) cast metal..

The relatively more frequent use on Dilmun seals this hieroglyph-multiplex of ‘twins’ is explained, not as a prefix but as a pairing device to signify dula ‘pair’ rebus: dul ‘cast metal’. Thus, in Dilmun area where the seals were inscribed and used, there was activity of producing metalcastings. The explicit use of the short-horned bull is also explained by the production of hard alloys: barad, balad ‘ox’ rebus: bharata ‘hard alloy of pewter, copper, tin’.

I submit that there was no distancing from the Indus Script tradition, but was a continuum on Dilmun seals by the artisans and merchants who had been conversant with the writing system tradition using rebus rendering of Prakrtam words to signify metalwork and create catalogues by inscribing on seals and seal impressions. The presence of Meluhhan settlements in the nearby contact areas of Elam/Sumer also explains why some Sumerian motifs also occur on the corpus of Dilmun seal inscriptions.

Many Dilmun seals are deciphered in this monograph as a continuum of the tradition of Indus Script Corpora to create hypertext data mines of metalwork catalogues to document and promote authenticated trade transactions across the Ancient Near East.

The presence of Meluhha settlements in Ancient Near East is attested in cuneiform texts. this finds confirmation in an ancient text. The ancient text is also the basis for suggesting the presence of Indian sprachbund speakers in Dilmun to create the Dilmun seals.

Baudhāyana śrautasūtra 18.44 which documents migrations of Āyu and Amavasu from a central region:

pran Ayuh pravavraja. tasyaite Kuru-Pancalah Kasi-Videha ity. etad Ayavam pravrajam. pratyan amavasus. tasyaite Gandharvarayas Parsavo ‘ratta ity. etad Amavasavam

Trans. Ayu went east, his is the Yamuna-Ganga region (Kuru-Pancala, Kasi-Videha). Amavasu went west, his is Gandhara, Parsu and Araṭṭa.

Ayu went east from Kurukshetra to Kuru-Pancala, Kasi-Videha. The migratory path of Meluhha artisand in the lineage of Ayu of the Rigvedic tradition, to Kasi-Videha certainly included the very ancient temple town of Sheorajpur of Dist. Etawah (Kanpur), Uttar Pradesh.

I, therefore, conclude that the Indus Script tradition of rebus signifiers using hieroglyphs continued on Dilmun seals indicating the possibility that the creators and users of the Dilmun seals were speakers from the Indian sprachbund (language union).

Dilmun seal from Bahrain.

koṭhāri 'crucible' Rebus:koṭhāri'treasurer' kuThAru 'armourer'

मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Munda)

करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं) A kid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi) khaNDa 'divisions' Rebus: khANDa 'implements'

dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'cast metal' meD 'body' rebus: med 'iron' meṛha, meḍhi ‘merchant’s clerk; (Gujarati) kAraNika 'spread legs' rebus: karNI 'Supercargo'-- a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale. Thus, a supercargo (controlling) cast metal.

ull-man standing on a hatched podium Fig. 4b, f bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch; Fig. 4a, c-d bull-man grasping an animal; Fig. 4b : bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch.

karaḍi 'safflower' Rebus: karandi 'fire-god' (Remo) karaḍa 'hard alloy' (Marathi); khaNDa 'divisions' Rebus: khANDa 'implements' koThAri 'crucible' Rebus: koThAri 'treasurer, warehouse' . मेढ (p. 662) [ mēḍha ] 'polar' star' Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Ho.M) करडूं or करडें 'hard alloy'. The ram is: Tor. miṇḍ'ram', miṇḍā́l 'markhor' (CDIAL 10310) Rebus: meḍh 'helper of merchant'.

Thus, the kid of ram signified hard alloy merchant which is rendered in Ancient Meluhha phonetic form from ca. 4th millennium BCE on the Sarasvati River basin as: मेंढा mēṇḍhā m (मेष S through H) A male sheep, a ram or tup मेंढ mēḍha करडूं or करडें karaḍū.

mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, ˚aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4 , miṇḍha -- 2 , ˚aka -- , mēṭha -- 2 , mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2 , ˚aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ]1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, ˚aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (˚ḍhī -- f.), ˚ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (˚dhiā -- f.), ˚aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb. amŕ n/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*l l ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m., ˚ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., ˚ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, ˚ḍā m., ˚ḍhi f., H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M. mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.

*mēṇḍharūpa -- , mēḍhraśr̥ṅgī -- .Addenda: mēṇḍha -- 2 : A. also mer (phonet. me r) ʻ ram ʼ AFD 235. *mēṇḍharūpa ʻ like a ram ʼ. [mēṇḍha -- 2 , rūpá -- ]Bi. mẽṛhwā ʻ a bullock with curved horns like a ram's ʼ; M. mẽḍhrū̃ n. ʻ sheep ʼ.(CDIAL 10310, 10311)

*

Fig. 5a-f bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch; Fig 5c, d bull-man standing ‘above’ an animal; Fig. 5a-f : bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch![]()

Features: god with a naked or garbed attendant behind or before; god holding/touching a crescent-standard; bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch Fig. 3b bull-man grasped/touched by a naked male figure Fig. 3b-f bull-man grasping an animal; Fig. 3d bull-man standing ‘above’ an animal; Fig. 3a : bull-man holding/touching a ‘ritual’ object or a branch

करडूं or करडें (p. 137) [ karaḍū or ṅkaraḍēṃ ] n A kid. कराडूं (p. 137) [ karāḍūṃ ] n (Commonly करडूं) A kid. (Marathi) Rebus: करडा (p. 137) [ karaḍā ] Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

Features Fig. 1c-f: god with a naked or garbed attendant behind or before; Fig. 1d-e god seated on a stool/throne ‘above’ a bull; Fig. 1a-f god drinking through a tube leading to a jar; god holding a cup

barad, balad, 'ox' rebus: bharat 'alloy of pewter, copper, tin'

meṭ sole of foot, footstep, footprint (Ko.); meṭṭu step, stair, treading, slipper (Te.)(DEDR 1557). dula ‘pair’.

Rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Rebus: dul 'metal casting'

Rebus: meḍ ‘iron’ (Ho.) dul meṛed, cast iron (Mu.) mẽṛhẽt baṭi = iron (Ore) furnaces (Santali)

kuDi 'drink' rebus: kuThi 'smelter' khaNDa 'water' rebus: khaNDa 'implements'

“Recent excavations on the island of Bahrain have uncovered a seal impression similar to a stamped seal tablet in the Yale Babylonian Collection. This Yale impression is dated to the tenth year of Gungunum, King of Larsa, in southern Babylonia – that is 1923 BCE. The Bahrain seal was found in a Barbar culture level, partially contemporary with the Umm an-Nar culture of Oman, which can in turn be paralled at Bampur V with the incised ware (‘hut-pot’) motifs. The general evidence, thus, points to a date c. 1900 BCE for the terminus of the Bampur sequence, and for the date of the Kurab shaft-hole pick-axe.” (Lamberg-Karlovsky, GC, 1969, Further Notes on the Shaft Hole Pick Axe From Khurab MakranIran, Vol. 7, 1969, pp 163-164) http://www.jstor.org/stable/4299621 .British Institute of Persian Studies

https://www.scribd.com/doc/315224554/Further-Notes-on-the-Shaft-Hole-Pick-Axe-From-Khurab-Makran-G-C-Lamberg-Karlovsky-Year-1969

Many sites on the Gulf of Khambat, and the site of Lothal evidence that the Sarasvati civilization was involved in trade through the Persian Gulf and beyond through Tigris-Euphrates upto Haifa, Israel in Ancient Near East.

Many sites on the Gulf of Khambat, and the site of Lothal evidence that the Sarasvati civilization was involved in trade through the Persian Gulf and beyond through Tigris-Euphrates upto Haifa, Israel in Ancient Near East.

m417 Glyph: ‘ladder’: H. sainī, senī f. ʻ ladder ʼ Rebus: Pa. sēṇi -- f. ʻ guild, division of army ʼ; Pk. sēṇi -- f. ʻ row, collection ʼ; śrḗṇi (metr. often śrayaṇi -- ) f. ʻ line, row, troop ʼ RV. The lexeme in Tamil means: Limit, boundary; எல்லை. நளியிரு முந்நீரேணி யாக (புறநா. 35, 1). Country, territory.

Hieroglyph: *śrētrī ʻ ladder ʼ. [Cf. śrētr̥ -- ʻ one who has recourse to ʼ MBh. -- See śrití -- . -- √śri]Ash. ċeitr ʻ ladder ʼ (< *ċaitr -- dissim. from ċraitr -- ?).(CDIAL 12720)*śrēṣṭrī2 ʻ line, ladder ʼ. [For mng. ʻ line ʼ conn. with √śriṣ2 cf. śrḗṇi -- ~ √śri. -- See śrití -- . -- √śriṣ2]Pk. sēḍhĭ̄ -- f. ʻ line, row ʼ (cf. pasēḍhi -- f. ʻ id. ʼ. -- < EMIA. *sēṭhī -- sanskritized as śrēḍhī -- , śrēṭī -- , śrēḍī<-> (Col.), śrēdhī -- (W.) f. ʻ a partic. progression of arithmetical figures ʼ); K. hēr, dat. °ri f. ʻ ladder ʼ.(CDIAL 12724) rebus: Seṭṭhi [fr. seṭṭha, Sk. śreṣṭhin] foreman of a guild, treasurer, banker, "City man", wealthy merchant Vin i.15 sq., 271 sq.; ii.110 sq., 157; S i.89; J i.122;ii.367 etc.; Rājagaha˚ the merchant of Rājagaha Vin ii.154; J iv.37; Bārāṇasi˚ the merchant of Benares J i.242, 269; jana -- pada -- seṭṭhi a commercial man of the country J iv.37; seṭṭhi gahapati Vin i.273; S i.92; there were families of seṭṭhis Vin i.18; J iv.62; ˚ -- ṭṭhāna the position of a seṭṭhi J ii.122, 231; hereditary J i.231, 243; ii.64; iii.475; iv.62 etc.; seṭṭhânuseṭṭhī treasurers and under -- treasurers Vin i.18; see Vinaya Texts i.102.

Seṭṭhitta Seṭṭhitta (nt.) [abstr. fr. seṭṭhi] the office of treasurer or (wholesale) merchant S i.92. The glyphics are:

Seṭṭhitta Seṭṭhitta (nt.) [abstr. fr. seṭṭhi] the office of treasurer or (wholesale) merchant S i.92. The glyphics are:

Semantics: ‘group of animals/quadrupeds’: paśu ‘animal’ (RV), pasaramu, pasalamu = an animal, a beast, a brute, quadruped (Te.) Rebus: pasra ‘smithy’ (Santali)

Glyph: ‘six’: bhaṭa ‘six’. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’.

Glyph (the only inscription on the Mohenjo-daro seal m417): ‘warrior’: bhaṭa. Rebus: bhaṭa ‘furnace’. Thus, this glyph is a semantic determinant of the message: ‘furnace’. It appears that the six protomes of animal heads of ‘animal’ glyphs' are related to ‘furnace’ work.

This guild, community of smiths and masons evolves into Harosheth Hagoyim, ‘a smithy of nations’.

It appears that the Meluhhans were in contact with many interaction areas, Dilmun and Susa (elam) in particular. There is evidence for Meluhhan settlements outside of Meluhha. It is a reasonable inference that the Meluhhans with bronze-age expertise of creating arsenical and bronze alloys and working with other metals constituted the ‘smithy of nations’, Harosheth Hagoyim.

It appears that the Meluhhans were in contact with many interaction areas, Dilmun and Susa (elam) in particular. There is evidence for Meluhhan settlements outside of Meluhha. It is a reasonable inference that the Meluhhans with bronze-age expertise of creating arsenical and bronze alloys and working with other metals constituted the ‘smithy of nations’, Harosheth Hagoyim.

Dilmun seal from Barbar; six heads of antelope radiating from a circle; similar to animal protomes in Failaka, Anatolia and Indus. Obverse of the seal shows four dotted circles. [Poul Kjærum , The Dilmun Seals as evidence of long distance relations in the early second millennium BC, pp. 269-277.] A tree is shown on this Dilmun seal.

Glyph: ‘tree’: kuṭi ‘tree’. Rebus: kuṭhi ‘smelter furnace’ (Santali).

baTa 'six' Rebus: bhaTa 'furnace' ranku 'antelope' Rebus: ranku 'tin'

Izzat Allah Nigahban, 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, The University Museum, UPenn, p. 97. furnace’ Fig.96a.

There is a possibility that this seal impression from Haft Tepe had some connections with Indian hieroglyphs. This requires further investigation. “From Haft Tepe (Middle Elamite period, ca. 13th century) in Ḵūzestān an unusual pyrotechnological installation was associated with a craft workroom containing such materials as mosaics of colored stones framed in bronze, a dismembered elephant skeleton used in manufacture of bone tools, and several hundred bronze arrowpoints and small tools. “Situated in a courtyard directly in front of this workroom is a most unusual kiln. This kiln is very large, about 8 m long and 2 and one half m wide, and contains two long compartments with chimneys at each end, separated by a fuel chamber in the middle. Although the roof of the kiln had collapsed, it is evident from the slight inturning of the walls which remain in situ that it was barrel vaulted like the roofs of the tombs. Each of the two long heating chambers is divided into eight sections by partition walls. The southern heating chamber contained metallic slag, and was apparently used for making bronze objects. The northern heating chamber contained pieces of broken pottery and other material, and thus was apparently used for baking clay objects including tablets . . .” (loc.cit. Bronze in pre-Islamic Iran, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-i Negahban, 1977; and forthcoming).

Izzat Allah Nigahban, 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, The University Museum, UPenn, p. 97. furnace’ Fig.96a.

There is a possibility that this seal impression from Haft Tepe had some connections with Indian hieroglyphs. This requires further investigation. “From Haft Tepe (Middle Elamite period, ca. 13th century) in Ḵūzestān an unusual pyrotechnological installation was associated with a craft workroom containing such materials as mosaics of colored stones framed in bronze, a dismembered elephant skeleton used in manufacture of bone tools, and several hundred bronze arrowpoints and small tools. “Situated in a courtyard directly in front of this workroom is a most unusual kiln. This kiln is very large, about 8 m long and 2 and one half m wide, and contains two long compartments with chimneys at each end, separated by a fuel chamber in the middle. Although the roof of the kiln had collapsed, it is evident from the slight inturning of the walls which remain in situ that it was barrel vaulted like the roofs of the tombs. Each of the two long heating chambers is divided into eight sections by partition walls. The southern heating chamber contained metallic slag, and was apparently used for making bronze objects. The northern heating chamber contained pieces of broken pottery and other material, and thus was apparently used for baking clay objects including tablets . . .” (loc.cit. Bronze in pre-Islamic Iran, Encyclopaedia Iranica, http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/bronze-i Negahban, 1977; and forthcoming).

Seal; BM 118704; U. 6020; Gadd PBA 18 (1932), pp. 9-10, pl. II, no.8; two figures carry between them a vase, and one presents a goat-like animal (not an antelope) which he holds by the neck. Human figures wear early Sumerian garments of fleece.

Stamp seals with figures and animals as Indus Script hieroglyphs

a. Dia 2.9 cm thickness 1.25 cm Gulf region, Bahrain, Karrana, Bahrain national Museum, Manama 4061

b. Dia 2.4 cm thickness 1.15 cm Gulf region, Bahrain, Karrana, Bahrain national Museum, Manama 4054

c. Dia 3 cm thickness 1.3 cm Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum 881 AIT

d. Dia 6.5 cm thickness 3 cm. Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum

e. Dia 2.8 cm thickness 1.3 cm Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum

f. Dia 2.5 cm thickness 1.3 cm Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum 881 UK

g. Dia 3.5 cm thickness 1.25 cm Gulf region, Failaka, Tell Sa’ad, F3, trench I, nu National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum 1129 CE.

“A number of decorative elements on the seals excavated at Bahrain and Failaka – two islands in the Gulf, which have been identified with the legendary kingdom of Dilmun – can be traced to Mesopotamia, Iran, the Indus Valley, Anatolia, and Central Asia. The cultural influences that these foreign motifs reflect stemmed from the maritime trade that connected the far-flung cities of the region beginning about 2500 BCE and lasting until about 1500 BCE. Epigraphic evidence from dated seal impressions and tablets found at Susa and Ur suggests that the Dilmun stamp seals, with their distinctive shape, were made between the end of the third millennium BCE and the early second millennium BCE. They are characterized by a flat obverse and a hemispherical reverse. Their backs are pierced for suspension and scored with multiple grooves at right angles to the piercing. Pairs of concentric circles are placed symmetrically on eithr side of the groose. Other characteristic features of the Dilmun glyptic include the manner in which animals and human figures are depicted. Deep cavities mark the eyes of animals, and there is no indication of a pupil; human figures, seen in profile, have linear bodies and stylized facial features rendered with horizontal lines. Foreign decorative elements on Dilmun seals include typical third-millennium BCE Mesopotamian imagery centered on male figures engaged in a rich repertoire of activities, including presentations in which local gods are occasionally adorned with the Mesopotamian horned crown as protectors of the flock; in contests with animals (see nos. 220d,e). In these scenes the adaptation of Mesopotamian dress, horned crown, bull-men (see no. 220c), standards, and lyres with taurine sound boxes (see no. 220f) indicates a close contact between the two regions and may signify a spiritual affinity. In catalogue number 220a a seated figure holds an axelike tool in one hand and reaches for the hand of a standing winged creature, possibly a deity, with the other. Similar winged figures on seals dating to the third millennium BCE are known from both Mesopotamia and Central Asia. The northern connection is underscored in this image by a solitary foot (here with four toes), a motif known from Central Asia and Syria and Iran. Two more seemingly unrelated elements – a bird and a gazelle – complete the composition. Ships and boats are a common theme. In catalogue number 220b the image can be interpreted as a variation of the Mesopotamian contest scene. Here, the central figure dressed in a tufted garment stands in a boat. He graps the animal’s foreleg with one hand, while the other is extended towards a companion figure. The craft resembles the modern-day mashluf – a small boat with a rather shallow draft, ideal for marsh travel. The boat with its upturned stern is reminiscent of vessels depicted in the earlier seals of Ur, a motif rarely occurring the second-millennium BCE Mesopotamian glyptic. The Mesopotamian pictorial repertoire is again reflected on a Dilmun seal showing two figures in an architectural setting (cat. No. 220c). The motif may best be compared with that of an early Old Babylonian seal in the Yale Babylonian Collection, New Haven, where suppliant deities and worshippers face an altar within a temple. They raise their hands in a gesture of respect toward a star standard on a podium. On the roof are two winged creatures and two vertical snakes that may be grasping. Two nude, double-belted fantastic beings with what seems to be three horns flank the structure and repeate the central worshippers’ gestures. Local decorative motifs such as a rosette, three stars, and two tree branches complete the harmonious, almost symmetrical composition that is so typical of later Dilmun seals. Mesopotamian banquet imagery occurs on three seals. In catalogue number 220e a high podium on which a small jar is placed separates two seated figures who confront each other. One of them is drinking through a long straw from a jar comparable in size to the one on the podium. This drinking scene closely parallels the image on a sealing dated to the reign of Gungunum of Larsa. Such drinking scenes must have had propitious significance for local Dilmunite seal owners. On a second seal with banquet imagery – by far the largest of the seven seals discussed here – two men dressed in tiered, flounced skirts face eath other (cat. No. 220d). Seated on rectangular stols, they are flanked by a ladder and a bird; between them are four vessels beneath a crescent and a star. Below, occupying most of the seal’s surface, are two vertical rows of bovids and recumbent antelopes. Two human figures, one nude, the other clothed, each raise one hand. On the third seal a seated man plays a three-stringed lyre (cat. No. 220f). The sound box is similar to Mesopotamian examples, such as those excavated from the royal tombs of Ur and those depicted on the Standard of Ur and in glyptic art. On preserved Mesopotamian lyres, bulls’ heads decorate the boxes, but in the present example the artists has created the music box out of the body of a bull so that its back acts as a strut – a detail paralleled on a stele from Tello, where the sound box of a lyre is formed by two superimposed bulls, one in profile. Seals with a radial composition form a distinct group. An example in this exhibition (cat. No. 220g) displays six antelope heads radiating like a six-pointed star from a central point. This decoration closely resembles that on sealings excavated at the early-second-millennium BCE site of Acemhovuk, in central Anatolia. Similar compositions are recorded earlier, however, at the site of Mohenjo-daro in the Indus Valley.

ib'iron'' (Santali) karba 'iron'; ajirda karba 'native metal iron' (Tulu) karabha 'trunk of elephant' Rebus: karba 'iron' ibha 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron ore' (Santali) The gloss ajirda (Tulu) is cognate with aduru, ayas. Hence, it is likely that the gloss ayas of Rigveda signifies native, unsmelted metal of iron ore. Glazed steatite . Cylinder seal. 3.4cm high; imported from Indus valley. Rhinoceros, elephant, crocodile (lizard? ).Tell Asmar (Eshnunna), Iraq. Elephant, rhinoceros, crocodile hieroglyphs: ib 'elephant' Rebus: ib 'iron' kANDa 'rhinoceros' Rebus: kANDa 'iron implements' karA 'crocodile' Rebus: khAr 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

cat.no. 218 “218. Cylinder seal with confronted figures and a tree. Steatite h 2.2 cm dia 1.15 cm Gulf region, Failaka F6 1174 Early Dilmun ca. 2000-1800 BCE National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters, Kuwait National Museum 1129 AXJ. The cylindrical form and the imagery of the seal exhibited here clearly illustrate how strong was Mesopotamian influence on the glyptic art of the Gulf. The image is a crude imitation of a Mesopotamian banquet scene. Two figures are seated on stools, which have been made to differ slightly by the addition of a second horizontal bar to one on the right. Horned headdresses identify the figures as deities. They are dressed in garments with tufts, indicated by the vertical striations, and their lower bodies appear exaggeratedly triangular. A crescent fills the space above and between them. Two nude worshippers, each of whom holds a crescent, flank a stylized tree, perhaps a date palm. Although the scene may have Mesopotamian roots, the peculiar details of the tree and the manner in which the humans are depicted – with elongated bodies and horizontal facial features – are typical of Gulf seals. This seal has counterparts at Susa, in Iran, where similarly nude worshippers are shown in front of enthroned deities.”(Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp.318-319)

cat. no. 221“221. Stamp seal with a boat scene. Steatite. L. 2 cm, w. 1.9 cm Gulf region, Failaka, F6 758 early Dilmun, ca. 2000-1800 BCE National Council of Culture, Arts, and Letters, Kuwait National Museum, 1129 ADY. This seal from Failaka island, at the head of the Gulf, is unusual in shape, as it is square rather than circular possibly alluding to the most common form of Harappan seals. The subject is a nude male figure standing in the middle of a flat-bottomed boat, facing right. The man’s arms are bent at the elbow, perpendicular to his torso. Beside him two jars stand on the deck of the boat, each containing a long pole to which is attached a hatched square that perhaps represents a banner. Flat-bottomed vessels with a single sail were used to transport cargoes in shallow tidal waters, but the one illustrated on this seal lacks a sail. If the two vertical posts on the stern are interpreted as steering paddles, then it resembles a model found in India at Lothal, which appears to have had square sails. Although the seal’s shape is atypical, all the decorative elements, including the boat and the two jars, find parallels on other seals from Dilmun, indicating that this one was made in the region where it was found.” (Note: On the Lothal boat model, three blind holes used as sockets may have held the masts of square-shaped sails.)(Art of the First Cities: The Third Millennium B.C. from the Mediterranean to the Indus, Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp.322-323)

Early Near Eastern Seals in the Yale Babylonian Collection, by Briggs Buchanan, with introduction and seal inscriptions by William W. Hallo, edited by Ulla Kasten. New Haven, Yale University Press, 1981.

Uruk-period seal (NBC 2579).

Seal no. 79 Persian gulf cylinder seal with seated person. Burnt steatite. H. 2.7 cm, dia 1.4 cm; string hole .3 cm Late 3rd-early 2nd millennium BCE Sb 1383 Excavated by Mecquenem. “The Mesopotamian influence on glyptic from the Persian gulf area is very clearly demonstrated in this example, one of the few cylinder seals executed in this distinctive style. Close parallels are found at Failaka, in the Gulf. Adopted here are not only the Mesopotamian cylinder-seal shape but also the theme of a worshipper standing before a seated horned deity in a flounced (?) garment and a version of the context scene with crossed animals. Pecular iconographic details also appear, however, such as the nude worshipper with his hand in a pot; the two ‘master of animals’, one nude and one kilted, grasping the animals’ necks; and the snake framing the scene from above. Glyptic and textual evidence suggests that the cities of Susa and Ur were trading centers in close contact with ancient Dilmun, located in the Persian Gulf. This contact, however, does not seem to have been limited to an exchange of goods. Francois Vallat has noted, the chief god of Dilmun, was one of a triad of deities worshipped on the Susa Acropole in the eighteenth century BCE. Persian Gulf-style seals found at Susa and other foreign sites with Mesopotamian and Indus-derived themes incorporated into their iconography were created, some scholars believe, for Dilmunite traders living abroad.” (The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre By Musée du Louvre, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992, p.120)

A bun-ingot flanked by two goats: mlekh 'goat' rebus: milakkhu 'copper' dula 'pair' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS muh ingot

Thus copper ingot. The dotted circles and three lines on the boss: dhAv 'strand' rebus: dhAv, dhAtu 'mineral' kolom 'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' tri-dhAtu 'three strands' rebus: three minerals. Thus the seal signifies a copper mineral cast ingot and a smithy/forge working with three minerals, tridhAtu. Seal of the old Elamite period in Metmuseum cat. no. 78 Persian Gulf stamp seal with two caprids. Burnt steatite. 2.2 cm. dia, .8 cm ht. Late 3rd -early 2nd millennium BCE Sb1015 Excavated by Mecquenem

The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre By Musée du Louvre, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992 “Many objects found at Susa reflect contacts with the Persian Gulf region…A mercantile document and a basket sealing were stamped with Gulf-style seals. Elamite imitations of Gulf seals were made in the local bitumen compound. Perhaps the most characteristic type of Persian Gulf seal is illustrated by this piece, one of four burnt, (whitened) steatite stamp seals found at Susa that have distinctive grooves and dot circles incised on a raised boss on the back. The face of this seal is engraved with the figures of two goats crouching head to foot on opposite sides of the circular field, the center of which is marked by a lozenge. Their slightly modeled bodies are defined by a curving outline, and distinctive details, such as large dot-circle eyes and striated necks, are sharply cut. Similar seals are known mainly from the Gulf region (and one example was found at Lothal in India). They were also exported to, and imitated at, the southern Mesopotamian city of Ur, a site with cuneiform texts that refer to the import of copper, semiprecious stones, and perhaps pearls from Dilmun. They are datable to the end of the third and the beginning of the second millennium BCE. That is the period when one elaborate Persian Gulf seal depicting a a Mesopotamian-derived ‘banquet scene’ was stamped on an old Babylonian contract between two merchants. The tablet, written in the time of Gungunum, ruler of Larsa in the late twentieth century BCE, is in the Yale Babylonian Collection. The document from Susa mentioning a Dilmunite merchant and ten minas of copper dates to the same period.” (p.119)

Cylinder (white shell) seal impression; Ur, Mesopotamia (IM 8028); white shell. height 1.7 cm., dia. 0.9 cm.; cf. Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 7-8, pl. I, no.7; Mitchell 1986: 280-1, no.8 and fig. 112; Parpola, 1994, p. 181; fish vertically in front of and horizontally above a unicorn; trefoil design

Cylinder seal; BM 122947; U. 16220; humped bull stands before a palm-tree, feeding froun a round manger or a bundle of fodder; behind the bull is a scorpion and two snakes; above the whole a human figure, placed horizontally, with fantastically long arms and legs, and rays about his head.

Seal and impression (BM 123059), from an antique dealer, Baghdad; script and motif of a bull mating with a cow; the tuft at the end of the tail of the cow is summarily shaped like an arrow-head; inscription is of five characters, most prominent among them the two 'men' standing side by side. To the right of these is a damaged 'fish' sign.cf. Gadd 1932: no.18; Parpola, 1994, p.219.

Seal; BM 122946; Dia. 2.6; ht. 1.2cm.; Gadd PBA 18 (1932), p. 7, pl. I, no.3; Legrain, Ur Excavations, X (1951), no. 629.

Seal impression, Mesopotamia (?) (BM 120228); cf. Gadd 1932: no.17; cf. Parpola, 1994, p. 132. Note the doubling of the common sign, 'jar'.

Seal impression; BM 123208; found in the filling of a tomb-shaft (Second Dynasty of Ur). Dia. 2.3; ht. 1.5 cm.; Gadd, PBA 18 (1932), pp. 13-14, pl. III, no. 16; Buchanan, JAOS 74 (1954), p. 149.

Seal; BM 122187; dia. 2.55; ht. 1.55 cm. Gadd PBA 18 (1932), pp. 6-7, pl. 1, no. 2Composite animal normalised as a sign is ligatured with a short tail with three prongs. kolom'three' rebus: kolimi 'smithy, forge' PLUS xoli'tail' rebus: kol'working in iron', kolhe 'smelter'

xoli 'tail' rebus: kol 'working in iron', kolhe 'smelter', kole.l 'smithy, forge'

aya 'metal, iron' PLUS khambhaṛā 'fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner'

https://tinyurl.com/y9lbeenj

“Another fact connected with Mohenjo Daro but strangely omitted from the official reports is the discovery of a piece of silver, bearing the number DK 1341 (NS9), made by Rao Bahadur (then Mr.) KN Dikshit, on the 1st of January 1926, on both sides of which he noted the occurrence of cuneiform punches. This silver piece is the earliest known cuneiform inscription or writing found in India, and will form part of the work of a future palaeographist who will have to revise the now classical treatise of Buhler (Indische Palaeographie, Strassburg, 1896).”(SM Katre, 1941, Introduction to Indian Txtual criticism, p.3)

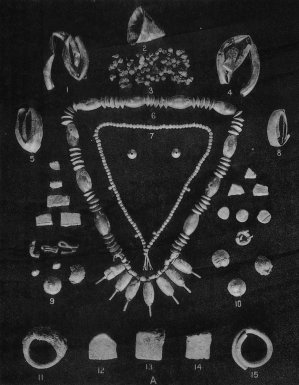

Gold jewellery, Mohenjodaro (After Marshall, Pl. CXLVIII).

The jewellery was found in a silver vase. The large necklace is made up of barrel-shaped beads of a translucent, light-green jade. Each jade bead is separated from its neighbours on either side by five disc-shaped gold beads, 0.4 in. dia made by soldering two cap-like pieces together. Seven pendants of agate-jasper are suspended by means of a thick gold wire. The pendants are separated one from another by a small cylindrical bead of steatite capped at each end with gold. The smaller necklace (No. 7) inside the large one is made up of small globular gold beads, all of which are cast. The spacers were made by soldering two of these beads together, and it is probable that the beads were originally strung into a bracelet of two rows. The two bangles (Nos. 1 and 4) were each made of thin sheet gold wrapped over a core (dia. 3 in.) No.2 is a conical gold cap (1.3 in. high) beaten out from a plate of gold; it is perhaps a hair ornament.

- Two silver bracelets were also found with this hoard. (Marshall, Pl. CLXIV)

![]() Silver vase, Mohenjodaro (After Marshall, Pl. CXLVIII). The silver vase contained gold jewellery.

Silver vase, Mohenjodaro (After Marshall, Pl. CXLVIII). The silver vase contained gold jewellery.

“The jewellery illustrated in Pl. CXLVIII,a, was found in the silver vessel (DK 1341), illustrated on the right of the plate, which was unearthed by Mr. Dikshit in a long trench that he dug to connect up sections B and C in the DK Area…Together with these strings of beads several rough pieces of silver were found, one of which bears chisel-marks remarkably like cuneiform characters. A cast of this piece was submitted to Mr. Sidney Smith, of the British Museum, who, however, could not identify any definite sign upon it. This fragment, which measures 0.95 by 0.9 by 0.25 inch, is part of a bar, from which it was shaped after both ends had been struck with a broad chisel.” (John Marshall, 1931, Mohenjo-daro, p.519)

“It is known for certain that seals and sealings of this class were carried thither by trade from Indus valley in ancient times, and one such seal has already been found (at ur) with a cuneiform in place of an ‘Indus’ inscription. (Mr. CL Woolley in Antiquaries’ Journal, 1928, p.26 and pl. xi,2)”(John Marshall, 1931, Mohenjo-daro, p.406)

I have not had access to the illustration on Pl. XI,2 of CL Woolley's article referred by John Marshall. I think he is referring to the following seal with a cuneiform text:

Note on cursive writing of Indus Script hypertext on a gold pendant

This 2.5 inch long gold pendant has a 0.3 inch nib; its ending is shaped like a sewing or netting needle. It bears an inscription painted in Indus Script. This inscription is deciphered as a proclamation of metalwork competence.

3 Gold pendants: Jewelry Marshall 1931: 521, pl. CLI, B3

The comments made by John Marshall on three curious objects at bottom right-hand corner of Pl. CLI, B3: “Personal ornaments…Jewellery and Necklaces…Netting needles (?) Three very curious objects found with the studs and the necklace appear to be netting needles of gold. They are shown just above the ear-studs and also in the lower right-hand corner of Pl. CLI, B, 3-5 and 12-14. The largest of these needles (E 2044a) is 2.5 inches long. The handle is hollow and cylindrical and tapers slightly, being 0.2 inch in diameter at the needle-end. The needle point is 0.5 inch long and has a roughly shaped oval eye at its base. The medium sized needle (E 2044b) is 2.5 inches long and of the same pattern: but the cap that closed the end of the handle is now missing. The point which has an oval eye at its base is 0.3 inch long. The third needle (E 2044c) is only 1.7 inches long with the point 0.3 inch in length. Its handle, which is otherwise similar to those of the other two needles, is badly dented. The exact use of these three objects is open to question, for they could have been used for either sewing or netting. The handles seem to have been drawn, as there is no sign of a soldered line, but the caps at either end were soldered on with an alloy that is very little lighter in colour than the gold itself. The two smaller needles have evidently been held between the teeth on more than one occasion.” (p.521)

Evidently, Marshall has missed out on the incription written in paint, as a free-hand writing, over one of the objects: Pl. CLI, B3.

This is an extraordinary evidence of the Indus writing system written down, with hieroglyphs inscribed using a coloured paint, on an object.

The comments made by John Marshall on three curious objects at bottom right-hand corner of Pl. CLI, B3: “Personal ornaments…Jewellery and Necklaces…Netting needles (?) Three very curious objects found with the studs and the necklace appear to be netting needles of gold. They are shown just above the ear-studs and also in the lower right-hand corner of Pl. CLI, B, 3-5 and 12-14. The largest of these needles (E 2044a) is 2.5 inches long. The handle is hollow and cylindrical and tapers slightly, being 0.2 inch in diameter at the needle-end. The needle point is 0.5 inch long and has a roughly shaped oval eye at its base. The medium sized needle (E 2044b) is 2.5 inches long and of the same pattern: but the cap that closed the end of the handle is now missing. The point which has an oval eye at its base is 0.3 inch long. The third needle (E 2044c) is only 1.7 inches long with the point 0.3 inch in length. Its handle, which is otherwise similar to those of the other two needles, is badly dented. The exact use of these three objects is open to question, for they could have been used for either sewing or netting. The handles seem to have been drawn, as there is no sign of a soldered line, but the caps at either end were soldered on with an alloy that is very little lighter in colour than the gold itself. The two smaller needles have evidently been held between the teeth on more than one occasion.” (p.521)

Evidently, Marshall has missed out on the incription written in paint, as a free-hand writing, over one of the objects: Pl. CLI, B3.

This is an extraordinary evidence of the Indus writing system written down, with hieroglyphs inscribed using a coloured paint, on an object.

Gold pendant with Indus script inscription. The pendant is needle-like with cylindrical body. It is made from a hollow cylinder with soldered ends and perforated joint. Museum No. MM 1374.50.271; Marshall 1931: 521, pl. CLI, B3 (After Fig. 4.17 a,b in: JM Kenoyer, 1998, p. 196).

ib 'needle' rebus: ib 'iron'

kanac 'corner' Rebus: kancu 'bronze'; sal 'splinter' Rebus: sal 'workshop'; dhatu 'cross road' Rebus: dhatu 'mineral'; gaNDa 'four' Rebus: khanda 'implements'; kolmo 'three' Rebus: kolami 'smithy, forge'; Vikalpa: ?ea ‘seven’ (Santali); rebus: ?eh-ku ‘steel’ (Te.)aya 'fish' Rebus: aya 'iron'(Gujarati) ayas 'metal' (Rigveda)

Thus, the inscription is: ib kancu sal (iron, bronze workshop), dhatu aya kaṇḍ kolami mineral, metal, furnace/fire-altar smithy. The hypertext message is: artisan with iron, bronze workshop, (competence in working with) minerals,metals, furnace/fire-altar, smithy/forge.

The inscription is a professional calling card -- describing professional competence and ownership of specified items of property -- of the wearer of the pendant.

What could these three objects be? Sewing needles? Netting needles?

सूची a [p= 1241,1] f. (prob. to be connected with सूत्र , स्यूत &c fr. √ सिव् , " to sew " cf. सूक्ष्म ; in R. once सूचिना instr.) , a needle or any sharp-pointed instrument (e.g. " a needle used in surgery " , " a magnet " &c ) RV. &c. See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2017/09/a-short-note-on-iconography-of-sindhu.html

Mrugendra Vinod links the needle to an Ashvamedha reference:The gold needles are found in Mohen jo Daro. They are explicitly referred to in Ashvamedha Ritual. (Ref.7)Ref. 7 यत्सूच न्नर्रन्नसपिातकल्पयन्नति।----िय्याः सूच्यो र्वन्नति। अयस्िय्यो रजिा हररण्याः। तै .ब्रा.3.9.6I do not know the explanation for the reference to and use of सूची in the Taittirīya Brāhmaṇa in the context of Ashvamedha yajña.

ஊசி¹ ūci

, n. < sūcī. 1. Sewing-needle; தையலூசி. (பிங்.). 2. Iron style for writing on palmyra leaves; எழுத்தாணி. பொன்னோலை செம் பொ னூசியா லெழுதி (சீவக. 369)I surmise that all the three gold objects could be pendants tagged to other jewellery such as necklaces.

The pendants were perhaps worn with a thread of fibre passing through the eye of the needle-like ending of the pendants and used as stylus for writing.

Why needle-like endings? Maybe, the pendants were used as 'writing' devices 1) either to engrave hieroglyphs into objects; 2)or to use the needle-ending like a metal nib to dip into a colored ink or liquid or zinc-oxide paste or cinnabar-paste. This possibility is suggested by the use of cinnabar in ancient China to paint into lacquer plates or bowls. Cinnabar or powdered mercury sulphide was the primary colorant lof lacquer vessels. "Known in China during the late Neolithic period (ca. 5000–ca. 2000 B.C.), lacquer was an important artistic medium from the sixth century B.C. to the second century A.D. and was often colored with minerals such as carbon (black), orpiment (yellow), and cinnabar (red) and used to paint the surfaces of sculptures and vessels...a red lacquer background is carved with thin lines that are filled with gold, gold powder, or lacquer that has been tinted black, green, or yellow." http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2009/cinnabar

![西漢 黑地朱繪雲氣紋漆碗 <br/>Bowl with Geometric Designs]()

Why needle-like endings? Maybe, the pendants were used as 'writing' devices 1) either to engrave hieroglyphs into objects; 2)or to use the needle-ending like a metal nib to dip into a colored ink or liquid or zinc-oxide paste or cinnabar-paste. This possibility is suggested by the use of cinnabar in ancient China to paint into lacquer plates or bowls. Cinnabar or powdered mercury sulphide was the primary colorant lof lacquer vessels. "Known in China during the late Neolithic period (ca. 5000–ca. 2000 B.C.), lacquer was an important artistic medium from the sixth century B.C. to the second century A.D. and was often colored with minerals such as carbon (black), orpiment (yellow), and cinnabar (red) and used to paint the surfaces of sculptures and vessels...a red lacquer background is carved with thin lines that are filled with gold, gold powder, or lacquer that has been tinted black, green, or yellow." http://www.metmuseum.org/exhibitions/listings/2009/cinnabar

Vikalpa: sūcīˊ’needle’ rebus: sūcika ‘tailor’

*sūcikāgharikā ʻ needle -- case ʼ. [Cf. sūcigr̥haka -- n. lex. -- sūcīˊ -- , ghara -- ]

Ku. suyārī, siyã̄rī ʻ needle bag ʼ.(CDIAL 13550) sūcīˊ f. ʻ needle ʼ RV., sūcí -- m. R. (f. Kālid. lex.), sūcikā -- f. lex.: v.l. śucĭ̄ -- . 2. *sūñcī -- . [Kaf. forms with č -- and Kho š -- can be explained as assimilation of s -- č, but Ash. points to IA. ś -- . If originally IA. had śūci -- (agreeing with Pahl. sūčan, Pers. sōzen), ś -- was perh. replaced by s -- through the influence of sīˊvyati, sūˊtra -- . Cf. similar influence of verb ʻ to sew ʼ in N.] 1. Pa. sūci -- , °ikā -- f. ʻ needle ʼ, Pk. sūī -- f., Gy. eur. suv, pl. suvya f., pal. suʻ , as. siv, Ḍ. sūiya f., Ash. arċūˊċ (ar -- < āˊrā -- ); Kt. čim -- čič ʻ iron needle ʼ, p -- čič ʻ thread ʼ; Paš.ar. sūī ʻ needle ʼ, chil. sūĩ, kuṛ. sũī, Shum. suīˊ, Gaw. suī˜, Kal.rumb. suš (< *suž with -- š carried into obl. sūšuna), urt. sužīk, Bshk. sū̃ī; Sh.gil. sū f. ʻ needle, pine needle ʼ, koh. sū̃ f., gur. sūw f.; K. suyu m. ʻ needle ʼ, suwa m. ʻ large pack -- needle ʼ; S. suī f. ʻ needle ʼ, suo m. ʻ pack -- needle ʼ, L.awāṇ. P. sūī f., sūā m., N. siyo (X siunu < sīvayati), B. sui, sũi, chũi, Or. sui, Bi. sūī, Mth. sui, Bhoj. suī, sūwā ʻ large needle ʼ, Aw.lakh. sūī, H. sūī f., sūā m., G. soy f., soyɔ, soiyɔ m., M. sū, sūī f., Ko. sū, suvva, Si. (h)ida, st. (h)idi -- . -- Ext. -- ḍ -- : S. suiṛī f. ʻ tattooing needle ʼ; Ku. syūṛo ʻ needle ʼ, gng. śwīṛ; N. suiro ʻ needle, goad, blade of grass ʼ.2. Wg. čunċ ʻ needle ʼ, Dm. čū̃či (NTS xii 163 < *šū̃či), Paš.dar. weg. sū˘nčék, gul. čánčak, Kho. šunǰ, B. sũc, suc, chũc, Or. suñci, chuñci, H. chū̃chī f.; Si. hin̆du ʻ porcupine quill ʼ. -- K. saċ m. ʻ large pack -- needle ʼ,saċan f. ʻ needle ʼ ← Ir., cf. Wkh. siċ, Pahl. sūčan.sūcika -- , *sūcya -- , saucika -- ; *sūcikāgharikā -- .*sūcya -- ʻ tailor ʼ see sūcika -- .Addenda: sūcīˊ -- [Cf. Ir. *sūčī -- in Shgh. X. Rosh. siǰ f. ʻ needle ʼ EVSh 73; also Pahl. sūčan id.]: deriv. WPah.kṭg. súɔ ʻ large needle ʼ. -- In line 2 read v.l. śūcĭ̄ -- .(CDIAL 13551)M. suċṇẽ ʻ to come to mind ʼ, sucẽ n. ʻ hint, suggestion ʼ, caus. Or. sucāibā ʻ to remind ʼ, G. sucavvũ ʻ to hint ʼ, rather than < śúcyati; -- WPah.kc. sunċṇo ʻ to consider ʼ, A. xusāiba rather < †samarthyatē? (J.C.W.)(CDIAL 13551a)1. WPah. (Joshi) sūī m. ʻ tailor ʼ, OG. suī m. (whence saïyaṇi f. ʻ his wife ʼ), G. soi, saī m. (or < 2).2. P. soī m. ʻ tailor ʼ, G. see 1.3. K. saċ m. ʻ tailor ʼ?Addenda: sūcika -- . 2. saucika -- : WPah.kṭg. sói m. ʻ tailor ʼ.(CDIAL 13549)

Ku. suyārī, siyã̄rī ʻ needle bag ʼ.(CDIAL 13550) sūcīˊ f. ʻ needle ʼ RV., sūcí -- m. R. (f. Kālid. lex.), sūcikā -- f. lex.: v.l. śucĭ̄ -- . 2. *sūñcī -- . [Kaf. forms with č -- and Kho š -- can be explained as assimilation of s -- č, but Ash. points to IA. ś -- . If originally IA. had śūci -- (agreeing with Pahl. sūčan, Pers. sōzen), ś -- was perh. replaced by s -- through the influence of sīˊvyati, sūˊtra -- . Cf. similar influence of verb ʻ to sew ʼ in N.] 1. Pa. sūci -- , °ikā -- f. ʻ needle ʼ, Pk. sūī -- f., Gy. eur. suv, pl. suvya f., pal. suʻ , as. siv, Ḍ. sūiya f., Ash. arċūˊċ (ar -- < āˊrā -- ); Kt. čim -- čič ʻ iron needle ʼ, p -- čič ʻ thread ʼ; Paš.ar. sūī ʻ needle ʼ, chil. sūĩ, kuṛ. sũī, Shum. suīˊ, Gaw. suī˜, Kal.rumb. suš (< *suž with -- š carried into obl. sūšuna), urt. sužīk, Bshk. sū̃ī; Sh.gil. sū f. ʻ needle, pine needle ʼ, koh. sū̃ f., gur. sūw f.; K. suyu m. ʻ needle ʼ, suwa m. ʻ large pack -- needle ʼ; S. suī f. ʻ needle ʼ, suo m. ʻ pack -- needle ʼ, L.awāṇ. P. sūī f., sūā m., N. siyo (X siunu < sīvayati), B. sui, sũi, chũi, Or. sui, Bi. sūī, Mth. sui, Bhoj. suī, sūwā ʻ large needle ʼ, Aw.lakh. sūī, H. sūī f., sūā m., G. soy f., soyɔ, soiyɔ m., M. sū, sūī f., Ko. sū, suvva, Si. (h)ida, st. (h)idi -- . -- Ext. -- ḍ -- : S. suiṛī f. ʻ tattooing needle ʼ; Ku. syūṛo ʻ needle ʼ, gng. śwīṛ; N. suiro ʻ needle, goad, blade of grass ʼ.2. Wg. čunċ ʻ needle ʼ, Dm. čū̃či (NTS xii 163 < *šū̃či), Paš.dar. weg. sū˘nčék, gul. čánčak, Kho. šunǰ, B. sũc, suc, chũc, Or. suñci, chuñci, H. chū̃chī f.; Si. hin̆du ʻ porcupine quill ʼ. -- K. saċ m. ʻ large pack -- needle ʼ,saċan f. ʻ needle ʼ ← Ir., cf. Wkh. siċ, Pahl. sūčan.sūcika -- , *sūcya -- , saucika -- ; *sūcikāgharikā -- .*sūcya -- ʻ tailor ʼ see sūcika -- .Addenda: sūcīˊ -- [Cf. Ir. *sūčī -- in Shgh. X. Rosh. siǰ f. ʻ needle ʼ EVSh 73; also Pahl. sūčan id.]: deriv. WPah.kṭg. súɔ ʻ large needle ʼ. -- In line 2 read v.l. śūcĭ̄ -- .(CDIAL 13551)M. suċṇẽ ʻ to come to mind ʼ, sucẽ n. ʻ hint, suggestion ʼ, caus. Or. sucāibā ʻ to remind ʼ, G. sucavvũ ʻ to hint ʼ, rather than < śúcyati; -- WPah.kc. sunċṇo ʻ to consider ʼ, A. xusāiba rather < †samarthyatē? (J.C.W.)(CDIAL 13551a)1. WPah. (Joshi) sūī m. ʻ tailor ʼ, OG. suī m. (whence saïyaṇi f. ʻ his wife ʼ), G. soi, saī m. (or < 2).2. P. soī m. ʻ tailor ʼ, G. see 1.3. K. saċ m. ʻ tailor ʼ?Addenda: sūcika -- . 2. saucika -- : WPah.kṭg. sói m. ʻ tailor ʼ.(CDIAL 13549)

Rebus: sūcika m. ʻ tailor ʼ VarBr̥S. 2. saucika -- m. Kull. 3. *sūcya -- . [sūcīˊ -- ] ஊசி¹ ūci

, n. < sūcī. 1. Sewing-needle; தையலூசி. (பிங்.). 2. Iron style for writing on palmyra leaves; எழுத்தாணி. பொன்னோலை செம் பொ னூசியா லெழுதி (சீவக. 369)Rebus: †sūcyatē ʻ is indicated ʼ Kāv., sūcya -- ʻ to be communicated ʼ Sāh. [Pass. of sūcayati ʻ indicates ʼ Up., Pk. suēi, suaï. -- Denom. fr. Pk. sūā -- f. ʻ indication ʼ, Sk. sūcā -- f. Buddh. -- Poss. < śūkā -- f. (ʻ sting ʼ Suśr., ʻ scruple, doubt ʼ lex.) ~ śūcĭ̄ -- . -- śūka -- ?]

Annex A Decipherment of a bilingual stamp seal from Ur?

This may be called Gadd Seal 1 of Ur since this was the first item on the Plates of figures included in his paper.

Introduction

Seal impression and reverse of seal from Ur (U.7683; BM 120573); image of bison and cuneiform inscription; cf. Mitchell 1986: 280-1 no.7 and fig. 111; Parpola, 1994, p. 131: signs may be read as (1) sag(k) or ka, (2) ku or lu orma, and (3) zi or ba (4)?. The commonest value: sag-ku-zi