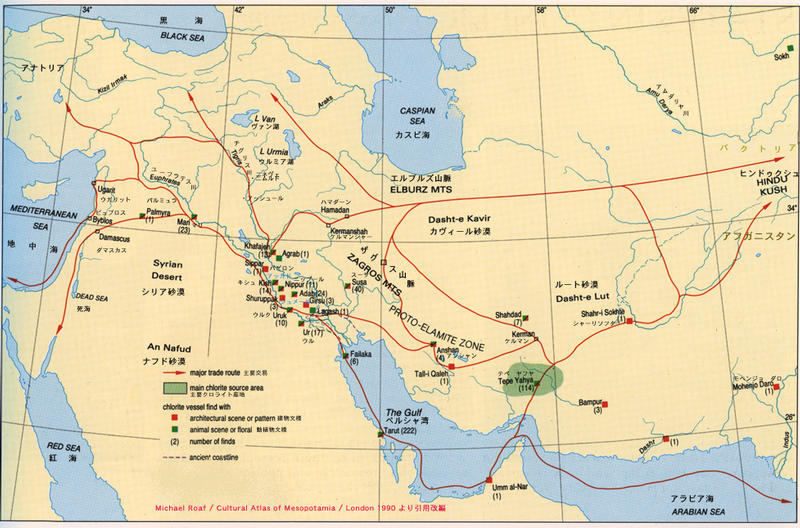

https://tinyurl.com/y2swgouy

This is an addendum to:

Sharper images discussed at https://tinyurl.com/yyv3uybo are further amplified in this addendum.

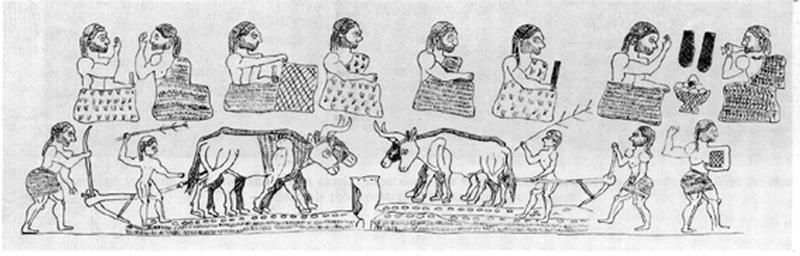

Two additional cylindrical vases with animals also are presented to complement the discussion on priests of R̥gveda displayed on the main Cylindrical Cup with Agricultural and Ceremonial Scene Bactria Late 3rd - early 2nd millennium B.C.E Silver. Sharper images presented herein contain additional pictorial narratives in Indus Script.

Miho Museum catalogue note states: "The ruins of a massive Bactrian fort of this same period have been excavated, along with temples inside the fort and large numbers of weapons, and we can thus imagine the existence of a ruler who was powerful both in politics and in military might, all while acting as the head cleric of the religion."

These discoveries on the site are consistent with and complement the messages conveyed through Indus Script hypertexts which constituted the writing system of Sarasvati Civilization people conveying messages in Meluhha cipher cataloguing their metalwork wealth through Indus Script inscriptions which constitute pictorial visual language -- technically called logo-semantic writing system.

The figure on the far right on the top register is shown with a basket of ingots in front and is raising a cup to his mouth. Jewels adorn his head, neck and wrists. The figure in front of this eminent person is shown in obeisance and is adorned with jewelry on his head only, thus indicating that this figure is an assistant to the eminent person.

I suggest that on the top register, the eminent person is:

brāhmanācchamsin –first assistant priest of Brahman.

I suggest that on the top register, eight priests are signified on the top register of Bactria vase; the right-most pair of priests flank a vessel with metal ingots of amśu (soma), ancu (Tocharian) 'iron'.

The two perforated vessels shown between the two persons is a signifier of the purification process or process of calcination, to harden the moltencast metal infusion in the fire-altar. The person shown in obeisance is neṣṭṛ = त्वष्टृ 'artisan', 'creator of living beings' (vividly metaphored as composite animals which constitute Indus Script hypertexts which are signifiers of metalwork wealth catalogues). The metaphor of Soma drink is shown with the eminent person holding a drinking vessel which is ancu 'iron' (Tocharian) rebus: amśu 'Soma'.

Eight priests shown on top register are:

brāhmanācchamsin –first assistant priest of Brahman;

hotṛ -- reciter of invocations;

potṛ -- purifier;

neṣṭṛ = त्वष्टृ so called RV. i , 15 , 3; त्वष्टृ a carpenter , maker of carriages (= त्/अष्टृ) AV. xii , 3 , 33; " creator of living beings " , the heavenly builder; maker of divine implements , esp. of इन्द्र's thunderbolt and teacher of the ऋभुs i , iv-vi , x Hariv. 12146 f. R. ii , 91 , 12 ; former of the bodies of men and animals , hence called " firstborn " (reference to 'bodies of men and animals' is significant since these constitute सांगड sāṅgaḍa A body formed of two or more (fruits, animals, men) linked or joined together rebus: sangara 'trade'.

RV 1.15.3 O Nestar, with thy Dame accept our sacrifice; with Rtu drink,

For thou art he who giveth wealth.(Griffith translation)

RV 1.15.3 Nes.t.a_ (= Tvas.t.a_), with your spouse, commend our sacrifice to the gods; drink with R.tu, for you are possessed of riches. [Tvas.t.a_ assumes the functions of Nes.t.r. as the priest at a sacrifice].(Wilson translation)

neṣṭṛ is called in RV 1.15.3 रत्न--धा mfn. procuring wealth , distributing riches or precious things ( -तम mfn. distributing great riches) RV. AV. S3Br.; possesing wealth. Thus, neṣṭṛ = त्वष्टृ, the procurer of wealth and distributor of riches.

agnīdh अग्नी* ध् – kindler of the fire;

adhvaryu -- in charge of the physical details of the sacrifice (in particular the adhvara, a term for the Somayajna).

pratiprasthātṛ -- प्र-° शास्तृ m. " director " , N. of a priest (commonly called मैत्रावरुण , the first assistant of the होतृ) RV. (RV 2.1.2 refers to प्र-° शास्तृ) प्रति-प्र-स्थातृ ( √ स्था) N. of a priest who assists the अध्वर्यु TS. Br. S3rS.

तवाग्ने होत्रं तव पोत्रमृत्वियं तव नेष्ट्रं त्वमग्निदृतायतः ।

तव प्रशास्त्रं त्वमध्वरीयसि ब्रह्मा चासि गृहपतिश्च नो दमे ॥२॥[1]

Thine is the Herald's task and Cleanser's duly timed; Leader art thou, and Kindler for the pious man.

Thou art Director, thou the ministering Priest: thou art the Brahman, Lord and Master in our home.— Rigveda 2.1.2 (Griffith translation)

RV 2.1.2 Yours Agni, is the office of the Hota_, of the Pota_, of the R.tvij, of the Nes.t.a_; you are the Agni_dhra of the devout; yours is the function of the Pras'a_sta_; you are the Adhvaryu (adhvaryu radhvarayur adhvaram ka_mayata iti va_ (Nirukta 1.8) and the Brahma_; and the householder in our dwelling. [Hota_ etc.: these are the eight of the sixteen priests employed at very solemn ceremonies; the duty of the Pras'a_sta_ is ascribed to the Maitra_varun.a, and Brahma_ is identified with the Bra_hman.a_ccahm.si; Kulluka Bhat.t.a, in his commentary on Manu viii.210 enumerates sixteen priests, in the order and proportion in which they are entitled to share in a daks.in.a_ of a hundred cows, being arranged in four classes, of which the first four are severally the heads, and others subordinate to them, in the same course of succession: 1. Hota_, Adhvaryu, Udgata_ and Brahma_, are to have twelve each, or forty-eight in all; 2. Maitra_varun.a, Pratistota_, Bra_hman.a_ccam.si and Prastota_, six each, or twenty-four; 3. Accava_ka, Nes.t.a_, A_gni_dhra and Pratiharta_ four each, or sixteen; and 4. Gra_vadut, Neta_, Pota_ and Subrahman.ya, three each, or twelve in all; making up the total of one hundred. Thus, the percentages for the four groups are: 48, 24, 16, 12 respectively. Ra_mana_tha, in his commentary on the Amarakos'a, viii.17 gives the names of 16 priests, but with a few variations: Gra_vastut replaces Gra_vadut; Prastota_, Neta_ and Pota_ are replaced with Prastha_ta_, Pras'a_sta_ and Balaccadaka. In the Aitareya Bra_hman.a vii.1, the sixteen priests are enumerated with some variations: Pratistota_, Gra_vadut, Neta_ and Subrahman.ya are replaced with Pratiprasthata_, Upaga_ta_, A_treya and Sadasya. Other priests included in this list are: Gra_vastut, Unneta_, Subrahman.ya and the S'amita_ (immolator), when a Bra_hman.a. Ma_dhava's commentary on the Nya_ya-ma_la-Vista_ra of Jaimini, the list of 16 priests, following Kuma_rila Bhat.t.a includes: 1. Adhvaryu, Prati-prastha_ta_, Nes.t.a_, Unneta_ (ceremonial of the Yajurveda); 2. Brahma_, Bra_hman.a_ccam.si, A_gni_dh, Pota_ (superintend the whole according to the ritual of the three vedas); 3. Udga_ta_, Prastota_, Pratiharta_, Subrahman.ya (chant the hymns, especially, Sa_maveda); 4. Hota_, Maitra_varun.a, Acchava_ka, Gra_vastut (repeat the hymns of the R.ca_); the head of each class receives the entire daks.in.a_,or gratuity; the second, one-half; the third, one-third; and the fourth, a quarter]. (Wilson translation).

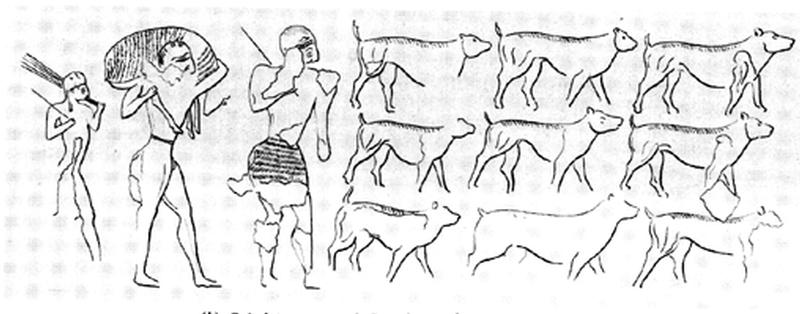

The bottom register is a farming scene with Indus Script hypertexts read rebus as goldsmith fine gold, ornament gold and iron metalworkshop.

Two boys or girls are seen holding holcus sorghum plants.

Young girl or boy hieroglyph

*kuḍa1 ʻ boy, son ʼ, ˚ḍī ʻ girl, daughter ʼ. [Prob. ← Mu. (Sant. Muṇḍari koṛa ʻ boy ʼ, kuṛi ʻ girl ʼ, Ho koa, kui, Kūrkū kōn, kōnjē); or ← Drav. (Tam. kur̤a ʻ young ʼ, Kan. koḍa ʻ youth ʼ) T. Burrow BSOAS xii 373. Prob. separate from RV. kŕ̊tā -- ʻ girl ʼ H. W. Bailey TPS 1955, 65. -- Cf. kuḍáti ʻ acts like a child ʼ Dhātup.]NiDoc. ǵ ʻ boy ʼ, kuḍ'i ʻ girl ʼ; Ash. kūˊṛə ʻ child, foetus ʼ, istrimalī -- kuṛäˊ ʻ girl ʼ; Kt. kŕū, kuŕuk ʻ young of animals ʼ; Pr. kyǘru ʻ young of animals, child ʼ, kyurú ʻ boy ʼ, kurīˊ ʻ colt, calf ʼ; Dm. kúŕa ʻ child ʼ, Shum. kuṛ; Kal. kūŕ*l k ʻ young of animals ʼ; Phal. kuṛĭ̄ ʻ woman, wife ʼ; K. kūrü f. ʻ young girl ʼ, kash. kōṛī, ram. kuṛhī; L. kuṛā m. ʻ bridegroom ʼ, kuṛī f. ʻ girl, virgin, bride ʼ, awāṇ. kuṛī f. ʻ woman ʼ; P. kuṛī f. ʻ girl, daughter ʼ, P. bhaṭ. WPah. khaś. kuṛi, cur. kuḷī, cam. kǒḷā ʻ boy ʼ, kuṛī ʻ girl ʼ; -- B. ã̄ṭ -- kuṛā ʻ childless ʼ (ã̄ṭa ʻ tight ʼ)? -- X pṓta -- 1 : WPah. bhad. kō ʻ son ʼ, kūī ʻ daughter ʼ, bhal. ko m., koi f., pāḍ. kuā, kōī, paṅ. koā, kūī.(CDIAL 3245) This hieroglyph kuṛī 'girl'is rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter'.

Holcus sorghum plant hieroglyph signifies kunda'fine gold' -- a semantic determinative of the young bulls खोंड khōṇḍa m A young bull, a bullcalf. खोंड khōṇḍa A variety of जोंधळा. Rebus: kunda 'fine gold'. The spiny horn is: singhin.śŕ̊ṅga n. ʻ horn ʼ RV. [See *śrū -- , *śruṅka -- ]Pa. siṅga -- n., Pk. siṁga -- , saṁga -- n.; Gy. eur. šing m. (hung. f.), ʻ horn ʼ, pal. šíngi ʻ locust -- tree ʼ (so -- called from the shape of its pods: with š -- < ṣ -- < śr -- ); Ash. Kt. ṣĭ̄ṅ ʻ horn ʼ, Wg. ṣīṅ, ṣŕ iṅ, Dm. ṣiṅ, Paš.lauṛ. ṣāṅg (or < śārṅga -- ), kuṛ. dar. ṣīṅ, nir. ṣēṅ, Shum. ṣīṅ, Woṭ. šiṅ m., Gaw. Kal.rumb. ṣiṅ, Bshk. ṣīṅ, Phal. ṣiṅ, pl. ṣíṅga; Sh.gil. ṣĭṅ m. ʻ horn ʼ, jij. ṣiṅ, pales. c̣riṅga ʻ temples ʼ (← Kaf. AO xviii 229); K. hĕng m. ʻ horn ʼ, S. siṅu m., L. siṅg m., awāṇ. sìṅg, P. siṅg m., WPah.bhad.bhal.khaś. śiṅg n., (Joshi) śī˜g m., Ku. sīṅ, N. siṅ, A. xiṅ, B. siṅ, Or. siṅga, Bhoj. sī˜gi , Aw.lakh. H. sī˜g m., G. sĩg n., M. śī˜g n., Ko. śī˜ṅga, Si. han̆ga, an̆ga, pl. aṅ (sin̆gu ← Pa.).śārṅga -- , śr̥ṅgín -- , śr̥ṅgī -- ; *śr̥ṅgadrōṇa -- , *śr̥ṅgapaṭṭa -- , *śr̥ṅgamāta -- , *śr̥ṅgayukta -- , *śr̥ṅgāsana -- ; *ut -- śr̥ṅga -- ; karkaṭaśr̥ṅgī -- , cátuḥśr̥ṅga -- , mēḍhraśr̥ṅgī -- ; -- śr̥ṅgāra -- ? Addenda: śr̥ṅga -- : WPah.kṭg. (kc.) śīˊṅg m. ʻ horn ʼ, J. śīṅg m., Garh. 'siṅg. (CDIAL 12583)

खुंडी, 'cereal plant, holcus sorghum' rebus: kunda'fine gold', 'a treasure of Kubera'. (जोंधळा jōndhaḷā m A cereal plant or its grain, Holcus sorghum. Eight varieties are reckoned, viz. उता- वळी, निळवा, शाळू, रातडी, पिवळा जोंधळा, खुंडी, काळबोंडी जोंधळा, दूध मोगरा. Unicorn or spiny-horned young bull signifies kunda singi 'fine gold, ornament gold'.)

Four young bulls signify gaṇḍā ‘four' rebus: khaṇḍā ‘tools, pots and pans and metal-ware’.

The ploughshare hieroglyph is a semantic determinative: The plougshare held by the ploughmen is पोत्रम् pōtram rebus: पोत्रम् pōtram 'purification by smelting of minerals/metals'. The right-most person carries a tablet; this narrative signifies पोतः-वणिज् m. a sea-faring merchant; धत्ते पोतवणिग्जनैर्धनदतां यस्यान्तिके सागरः Śiva B. 29.89. Hie right hand is also an Indus Script hieroglyph: eraka 'raised hand' rebus: eraka 'molten cast,metal infusion'; arka 'copper, gold' as in arka śālā 'goldsmith workshop'. Thus, the right-most person is a seafaring merchant (of) goldsmith workshop.

Catalogue Entry(Bac#007) Miho Museum

300 Momodani; Tashiro Shigaraki Koka; Shiga 529-1814, Japan

Tel: +81 (0)748-82-3411

Fax: +81 (0)748-82-3414

Two perforated vessels characteristic of Sarasvati Civilization are shown atop a basket containing metal ingots. The scene is flanked by two priests.

Two perforated vessels characteristic of Sarasvati Civilization are shown atop a basket containing metal ingots. The scene is flanked by two priests.I suggest that the perforated jars were used in fire-altars, to infuse carbon from plant products into molten metal on the fire-altar to harden the alloyed molten metal.

Perforated jar.Mohenjo-daro 2700 to 2000 BCE.

https://www.pinterest.com/pin/431641945518251245/

Other narratives on the cylindrical silver vase show hunting scenes together with hunter, markhor, tigers.The rebus readings of Indus Script hieroglyphs are: panja 'feline paw' rebus: panja 'kiln, furnace' PLUS kold 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter' kole.l 'smithy, forge'.

खरडा kharaḍā , खरड्या [ kharaḍyā ] m or खरड्यावाघ m A leopard (Marathi) Rebus 1: karaDa 'hard alloy'; Rebus 2: kharada 'daybook entries' खरडें n A rude sketch; a rough draught; a foul copy; a waste-book; a day-book; a note-book.(Marathi)

कौटिलिकः kauṭilikḥ कौटिलिकः A hunter.-Rebus: कौटिलिकः kauṭilikḥ A blacksmith

G. kāmṭhiyɔ m. ʻ archer ʼ(CDIAL 2760) Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint'

Hieroglyph markhor, ram: mēṇḍha2 m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- , mēṇḍa -- 4, miṇḍha -- 2, °aka -- , mēṭha -- 2, mēṇḍhra -- , mēḍhra -- 2, °aka -- m. lex. 2. *mēṇṭha- (mēṭha -- m. lex.). 3. *mējjha -- . [r -- forms (which are not attested in NIA.) are due to further sanskritization of a loan -- word prob. of Austro -- as. origin (EWA ii 682 with lit.) and perh. related to the group s.v. bhēḍra -- ]1. Pa. meṇḍa -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, °aka -- ʻ made of a ram's horn (e.g. a bow) ʼ; Pk. meḍḍha -- , meṁḍha -- (°ḍhī -- f.), °ṁḍa -- , miṁḍha -- (°dhiā -- f.), °aga -- m. ʻ ram ʼ, Dm. Gaw. miṇ Kal.rumb. amŕn/aŕə ʻ sheep ʼ (a -- ?); Bshk. mināˊl ʻ ram ʼ; Tor. miṇḍ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍāˊl ʻ markhor ʼ; Chil. mindh*ll ʻ ram ʼ AO xviii 244 (dh!), Sv. yēṛo -- miṇ; Phal. miṇḍ, miṇ ʻ ram ʼ, miṇḍṓl m. ʻ yearling lamb, gimmer ʼ; P. mẽḍhā m.,°ḍhī f., ludh. mīḍḍhā, mī˜ḍhā m.; N. meṛho, meṛo ʻ ram for sacrifice ʼ; A. mersāg ʻ ram ʼ ( -- sāg < *chāgya -- ?), B. meṛā m., °ṛi f., Or. meṇḍhā, °ḍā m., °ḍhi f., H. meṛh, meṛhā, mẽḍhā m., G. mẽḍhɔ, M.mẽḍhā m., Si. mäḍayā.2. Pk. meṁṭhī -- f. ʻ sheep ʼ; H. meṭhā m. ʻ ram ʼ.3. H. mejhukā m. ʻ ram ʼ.A. also mer (phonet. mer) ʻ ram ʼ (CDIAL 10310). Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.)

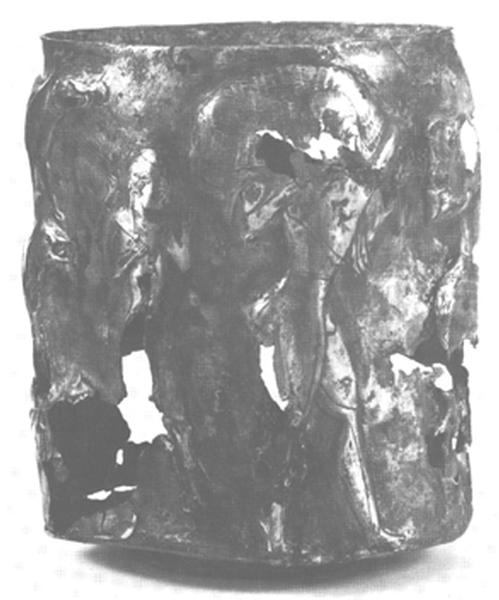

Cylindrical Cup with Agricultural and Ceremonial Scene

- Bactria

- Late 3rd - early 2nd millennium B.C.

- Silver

- H-12.6 D-9.9

- A fine metalworking tradition appears to have developed in western Central Asia in the late third to the early second millennium B.C. Based on comparisons with excavated pottery types and with finds in the so-called Fullol hoard of objects from northern Afghanistan,1 a number of gold and silver vessels have been attributed to Bronze Age Bactria. Perhaps the most exceptional are cylindrical silver vessels with elaborate figural scenes executed in low relief with incised details, all of which may come from a single workshop.

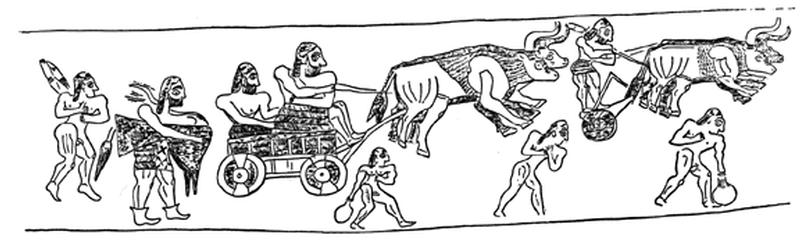

On this example,2 bearded and moustached male banqueters wearing fillets in their bound long hair are seated in a row above men and boys plowing a field. The main personage in this upper row, who faces left, is distinguished by an elliptically shaped bead on his fillet; he also wears a necklace and bracelet with similar beads, all bearing hatched patterns that might suggest veined stone such as agate. A robe with very clearly rendered individual tufts covers one arm entirely and envelops the rectangular form of his lower body. The man's exposed right arm is raised to hold a tall footed beaker to his mouth (this is the only figure to have a defined mouth). In front of him are a footed fruit bowl, a pair of tall vessels, and a second seated figure wearing a robe with a herringbone pattern. The proper right arm of this figure is raised toward the main personage. Also part of this banqueting scene are five other seated male figures, their garments distinguished alternatively by individual tufts or horizontal rows of hatchings that form herringbone patterns. Some figures hold beakers and one rests a hand on a large altar-like rectangular object with a crosshatched pattern.

In the scene below, two plows are held by long-haired men wearing short kilts with herringbone patterns. Before them, nude youths holding branches attempt to keep two pairs of oxen under control. Another male figure holds a square object-perhaps a box or even a drum-under one arm, and raises the other one. The figures stand on freshly seeded earth; between the animals is an object with a wavy-line pattern and seed-like elements along the top edge. Although difficult to interpret, this could indicate landscape in viewed from above or a vessel in profile.

While iconographic elements such as the garments connect the imagery on this cup to the art of Mesopotamia and Elam, certain aspects of style are very distinctive. In particular, a strong interest in the placement of human and animal figures in space is manifest. The oxen in the background are darkened with hatched lines to clearly distinguish them from those in the foreground.3 The muscular shoulders of the human figures may be depicted in profile or in three-quarter view, and they may have one rather than two nipples showing. The two plows, one seen from the front and the other from the back, are placed behind one and in front of the other nude youth. An interest in the use of patterning to define the textures of garments and objects is also evident.

In style, this cup is closely related to a silver vessel in the Levy-White collection.4 The main personage in a hunting scene there bears a close resemblance to the main figure on the present cup. He is bearded, with a well-delineated mouth, and has elliptical beads both in his hair and around his neck. A figure with similar features appears on another cup, which depicts the aftermath of a successful hunt.5

JA

1. Amiet 1988b, pp. 136, 161, describes this hoard (like the "Astrabad treasure" from Iran with related material) as a contrived collection of objects from clandestine excavations in northern Afghanistan; see Tosi and Wardak 1972, pp. 9-17.

2. See Amiet 1986, pp. 328-29, fig. 202; Pottier 1984, pp. 73, 212, pl. xxx, fig. 250; Deshayes 1977, pp. l04-5; Amiet 1988b, p. 136, fig. 9.

3. This convention is also used on a cylindrical cup in the Louvre, with a chariot scene: see Amiet 1988b, p. 163, fig. 6.

4. See Pittman 1990, pp. 43-44, no. 30.

5. Amiet 1986, pp. 326-27, fig. 201. - Late 3rd‐early 2nd millennium B.C.

Silver

H. 12.2-12.6 cm, Dia. 9.5-9.9 cm

Designs are incised into an upper and lower register on the walls of this silver cup, with the upper register showing a ritual scene and the lower register showing a farming scene with oxen. The upper register scene has also been thought to be a banqueting scene, but of the eight seated figures, only the figure on the far right facing to the left is shown with food before him and raising his cup to his mouth. This figure is also shown with his head, neck and wrists wearing jewels that appear to be onyx, and higher grade of clothing, both clearly symbols of his high rank. The figure directly in front of this high ranking figure is shown in a position of obeisance, and he has jewelry only on his head. The other six figures have no jewelry. These devices clearly are thought to indicate the respective ranks of these figures. This offertory or welcoming posture can also be seen in the last two figures in this row. - The two oxen in the lower register are shown pulling plows during a tilling and planting scene. The small naked figure wields a stick to urge on the oxen, and there are clear divisions drawn between the figures holding onto the plow and those sowing seeds. There are similar examples of silver cups from this period with hunting scenes, and in the same manner, those who are thought to be high-ranking figures are shown adorned with jewelry thought to be made of onyx. This body expression with short kilted skirt and emphasized musculature was characteristic of the western Central Asia through Eastern Iran from the 3rd millennium BC through the 2nd millennium BC. The arranged hair expression on the forequarters of the oxen and the musculature of the back legs are also unique to Bactrian culture. The ruins of a massive Bactrian fort of this same period have been excavated, along with temples inside the fort and large numbers of weapons, and we can thus imagine the existence of a ruler who was powerful both in politics and in military might, all while acting as the head cleric of the religion. These people did not have writing, but this vessel clearly depicts one aspect of their society.

http://www.miho.or.jp/booth/html/artcon/00000922e.htm

Cylindrical cup with animals

- Western Central Asia

- 3rd millennium BC

- Silver

- H-12.1 D-10.3

- Late 3rd‐early 2nd millennium B.C.

Silver

H. 11.0 cm, Dia. 9.5 cm

The torso surface of this silver cup is decorated with a leopard with legs spread as if running and a seated ibex. Plant forms are shown between these animals and designs which look like stars. Circles can be seen carved in the midst of the tree forms. At first glance this looks like a scene of a leopard hunting the ibex, and yet the seated ibex and leopard with mellow expression do not seem to construe a death attack scene. Ancient west Asia astronomy included both a leopard constellation and an ibex constellation, and around 4th millennium BC, these two constellations could be seen clearly in the spring equinoctial sky just before dawn. Thus it is thought that a combination of leopard and ibex probably symbolized the arrival of the new year. Further, in the Iranian highlands designs of the god spirit of the ibex grasping a snake have appeared since antiquity on seals, and this is thought to symbolize the god of the ibex ruling over the source of life, water. The combination of ibex, tree, and star design frequently can be seen on seals from Elam in southern Iran ca. 3,000 BC, and thus may have existed as an artistic expression in eastern Iran and western Central Asia under the influence of Elamite culture. In Mesopotamia in the 3rd millennium BC, the ibex constellation was divided into the Aquarius constellation and the Capricorn constellation, while in ancient western Asia, the Taurus and Leo constellations could be seen right after the sun set at the spring equinox and came to symbolize the new year. A cylindrical seal from ca. 3,000 BC excavated at the Tell Agrab site on the Diyala River region of Iraq has this same motif combining a tree with a circular form, there combined with other plant motifs and a battle scene between a lion and a bull. Thus we can imagine that these symbolic designs had some important role in the culture of that period. - http://www.miho.or.jp/booth/html/artcon/00002110e.htm

Cylindrical cup with animals

- Western Central Asia

- 3rd millennium BC

- Silver

- H-11 D-9.5 http://www.miho.or.jp/booth/html/artcon/00002111e.htm

![]()

Cylindrical cup with animals

- Bronze Age Bactria

- Late third - early second millennium B.C.

- Late third - early second millennium B.C

- Silver

- H-9.7 D-11.2 http://www.miho.or.jp/booth/html/artcon/00000918e.htm