-- Unicorn on Ishtar gate is Indus Script hypertext kunda singi 'horned young bull' rebus fine gold, ornament gold; this set the Gold standard seen on Lydia electrum coin; Mušḫuššu is ironwork

-- Kudurru symbols, symbols on Ishtar gate and remembered memories of Indus Script hypertexts of metalwork wealth accounting

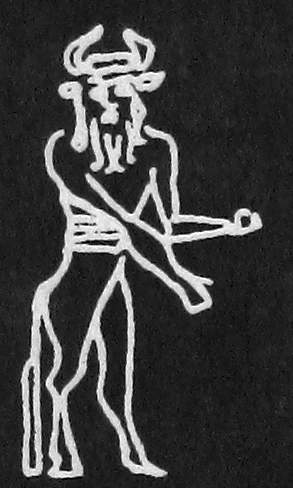

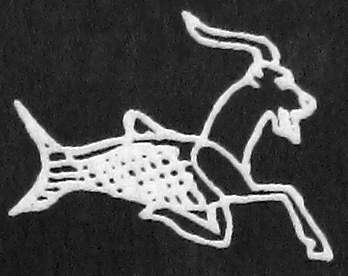

One panel of the sculptural friezes on Shalamanesher Black Obelisk shows uniquely horned bovines. One has two horns, one has a single horn and the third has a double-lion-sickle adapted from the iconography of Early Dynastic II period (c. 2750-2600 BCE). These can be viewed as recollected memories of Indus Script Cipher hypertexts: dhangar 'bull' rebus: dhangar 'blacksmith' PLUS horns of zebu: poḷa 'zebu' rebus: poḷa 'magnetite, ferrite ore' PLUS dhatu 'scarf' rebus: dhatu 'mineral ores'; kunda singi 'young bull horned' rebus: kunda singi 'fine gold, gold for ornaments'; ranku 'antelope' rebus: ranku 'tin' PLUS double-lion-sickle: arye 'lion' rebus: āra 'brass' PLUS dula 'two' rebus: dul 'metal casting' PLUS katti 'sickle' rebus: khātī 'wheelwright'. The horns signify: koḍ 'horns' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'. Thus, a repertoire of workshops with artisans working in iron, fine gold, ornament gold, tin and metal alloys.

These rebus renderings explain why the three animal compositions are listed as 'tributes from workshops of Muśiri' by Shalamanesher II on the cuneiform inscription. Muśiri has been identified as Kurdistan (where Yazidi practice Hindu traditions of wearing tilak on their foreheads even today). See:

Meluhha settlers of Musri (Kurdistan) offer tributes, document the wealth in Indus Script on ShalamaneserIII black obelisk https://tinyurl.com/y6yhql2g

katti 'sickle' (Tamil) kāti the knife attached to the cock's foot (Voc. 490). ? Cf. 1208 Kol. katk-.(DEDR 1204) Rebus 1: khātā 'labour sphere account book' Rebus 2: käti ʻwarrior' (Sinhalese)(CDIAL 3649). Hieroglyph: katī 'blacksmith's goldsmith's scissors' rebus: khātī m. ʻ 'member of a caste of wheelwrights'

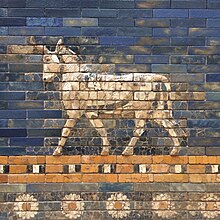

The animals exhibited by Nebudanezzar on Ishtar gate are traceable to the descriptions recorded in 3rd millennium BCE. For examples, Aurochs (Bos primigenius) is identified in"Texts as early as the Early Dynastic II period (c. 2750-2600 BCE) describe Marduk as the “bull-calf” of the sun god, Shamash (UTU)."

I submit that many symbols on Kudurrus of 2nd millennium BCE from sites of Ancient Near East are recollected, remembered memories of Indus Script hypertexts of metalwork wealth accounting. This explains why the Ishtar Gate dramatically displays 'unicorns', 'lions' and Mušḫuššu (composite animal). Composite animals as hypertexts is the hall-mark Indus Script Cipheer; each hieroglyph component is part of a hypertext message related to wealth-accounting ledgers of metalwork, lapidary work with gems and jewels. The most frequent artisanal activity relates to working with fine gold and gold for ornaments signified by the 'one-horned young bull', the so-called 'unicorn'.

The monograph presents arguments to explain the Ishtar Gate Indus Script hypertexts of unicorns', 'lions' and Mušḫuššu (composite animal).

"The Ishtar Gate (Arabic: بوابة عشتار) was the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon.It was constructed in about 575 BCE by order of King Nebuchadnezzar II on the north side of the city. It was part of a grand walled processional way leading into the city. The walls were finished in glazed bricks mostly in blue, with animals and deities in low relief at intervals, these also made up of bricks that are molded and colored differently." The gates are now seen in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

"The Ishtar Gate (Arabic: بوابة عشتار) was the eighth gate to the inner city of Babylon.It was constructed in about 575 BCE by order of King Nebuchadnezzar II on the north side of the city. It was part of a grand walled processional way leading into the city. The walls were finished in glazed bricks mostly in blue, with animals and deities in low relief at intervals, these also made up of bricks that are molded and colored differently." The gates are now seen in Berlin’s Pergamon Museum.

From the inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II on the gate constructed ca. 605–562 BCE

:

"I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor so that Mankind might gaze on them in wonder.

I let the temple of Esiskursiskur, the highest festival house of Marduk, the lord of the gods, a place of joy and jubilation for the major and minor deities, be built firm like a mountain in the precinct of Babylon of asphalt and fired bricks." (Marzahn, Joachim (1981). Babylon und das Neujahrsfest. Berlin: Berlin : Vorderasiatisches Museum. pp. 29–30.)

The cuneiform inscription of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate.

Bull in Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate. Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate animal june 2019 2192.jpg

Istanbul Ancient Orient Museum Ishtar Gate animal june 2019 2192.jpg

An aurochs above a flower ribbon; missing tiles are replaced

One of the striding lions from the Processional Way. egelrelief från Nebukadnessars tronsal i Babylon. 604-562 f Kr. Finns utställd i arkitekturhallen på Röhsska museet.Foto: Mikael Lammgård, Röhsska museet

arye 'lion' rebus: āra 'brass'

See:

Lydia coin 6th cent. BCE juxtaposes Indus Script protomes of Unicorn bull, kunda śṛṅgi, and Lion paw, arye panja https://tinyurl.com/yxvmsoyf

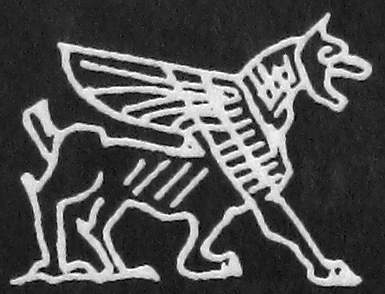

mushhushshu

mushhushshu.

mushhushshu.Hind legs are with eagle tenons.

Front legs are with feline paws

śyena 'eagle' rebus: aśani 'thunderbolt' ahan 'iron'

kola 'tiger' rebus kol 'working in iron' kolhe 'smelter'; panja 'feline paws' rebus panja 'furnace, kiln'

It is horned. sing 'horned' rebus: sing 'gold for ornaments'

It has a cobra-hood for its face.

mũha 'face' mũha 'ingot, quantity of iron taken at one time from a furnace'

I submuit that this is a metalwork mint working in iron, gold, alloys.

| T |

"It appears that the choice of a particular being portrayed on a given object could be influenced by factors such as its owner’s profession, religious and/or political affiliations, and especially by the apotropaic function(s) of specific composite beings...several Mesopotamian (including Babylonian and Assyrian) kings were characterized as apkallu, implying that they were sources of creativity, wisdom, and power to sustain and protect their subjects.

" (Constance Ellen Gane, Composite Beings in Neo-Babylonian Art, Doctoral Dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, 2012, p. 1, p.20).https://laplacamadre.files.wordpress.com/2014/08/apkallu-composite-beings-in-neo-babylonian-art.pdf.

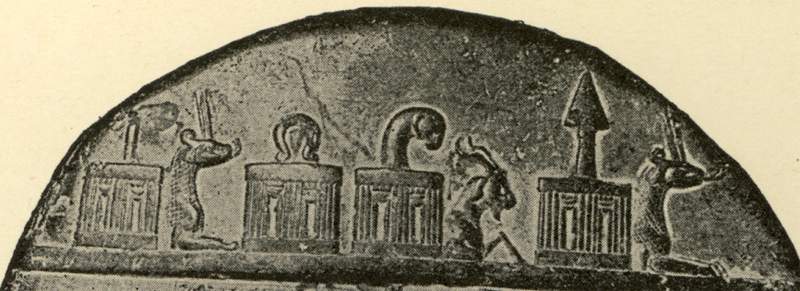

"Cylinder seal VA 7738 from Babylon (Ill. 2.2) depicts a striding, four-winged human apkallu facing right, with his right hand raised before a central tree. On the right and facing left toward the tree is a bearded, human-headed two-winged lion, slightly rampant toward the tree. Above the wing of this sphinx is a crescent moon. Behind the apkallu is a pedestal consisting of six vertical posts. A marru (spade-standard of Marduk) and double-wedged stylus (symbol of Nabu) surmount the pedestal.52 Above the marru and stylus is an eightpointed star. The scene has an awkward distribution in that none of the figures or the pedestal base are on the baseline, but rather appear to float in the air. " (CGane, 2012, opcit., p.26)

Illustration 2.2. Four-winged human-figured ūmu-apkallu. NB cylinder seal: VA 7738 (Babylon) Source. Adapted from Anton Moortgat, Vorderasiatische Rollsiegel: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Steinschneidekunst (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1988), 147, no. 686.

"A worship scene on cylinder seal CBS 14366 from Nippur (Ill. 2.3) has two figures oriented to the left. On the left of the scene, a nude four-winged apkallu reaches forward to grasp the marru spade-standard of Marduk in one hand, while lifting his other hand over it. He has long hair, a beard, and a fillet about his head. Behind the apkallu is a bearded, two-winged human-headed lion that strides toward a tall emblem, perhaps the stylus of Nabu." (ibid.)

Illustration 2.3. Four-winged human-figured ūmu-apkallu. NB cylinder seal: CBS 14366 (Nippur) Source. Adapted from Leon Legrain, Culture of the Babylonians from Their Seals in the Collections of the Museum (2 vols.; PBS 14.1-2; Philadelphia: The University Museum, 1925), pl. XXXIII, no. 654.

"Chalcedony stamp seal VA 6950 from Babylon (Ill. 2.4) has a schematic single figure on the face of the seal. A four-winged ūmu-apkallu stands in profile facing to the right. One arm is raised and holds an unidentifiable object. The other arm is lowered and also holds an unidentifiable object (probably a bucket). The creature maintains the posture and gesture typical of the apkallu." (ibid.)

Illustration 2.4. Four-winged human-figured ūmu-apkallu. NB stamp seal: VA 6950 Bab 41132 (Babylon) Source. Adapted from Liane Jakob-Rost and Iris Gerlach, Die Stempelsiegel im Vorderasiatischen Museum (2d ed.; Mainz: Zabern, 1997), no. 216.

Illustration 2.5. Four-winged human-figured ūmu-apkallu. NB stamp seal impression: BM 56251 (Sippar) Source. Adapted from Terence C. Mitchell and Ann Searight, Catalogue of the Western Asiatic Seals in the British Museum. Stamp Seals III: Impressions of Stamp Seals on Cuneiform Tablets, Clay Bullae, and Jar Handles (Leiden: Brill, 2008), no. 348.

"Two stamp seal impressions, BM 56251 and BM 66789 (Ills. 2.5-2.6), on tablets from Sippar show the four-winged ūmu-apkallu in profile facing to the left. In both examples, the arms are in the typical apkallu gesture with one arm raised and one arm lowered. The scenes are only partially preserved and do not include the hands." (ibid.)

Human apkallu in same posture as on fish apkallu. "The ritual behavior, including orientation and stance, of the provenanced NB human ūmuapkallu are typical of apkallu-type beings: He stands in profile and raises one forearm; the palm of his hand is oriented downward, and with it he usually grasps a mullilu cone or sprinkler.47 His other hand is lowered and usually holds a banduddû bucket." (CGane, opcit., 2012, p.25)

Illustration 2.8. Wingless human-figured ūmu-apkallu. NB stamp seal impression: GCBC 585 (Uruk) Source. Adapted from Ehrenberg, Uruk, pl. 24, no. 193

“In them, a human-apkallu, or sage, holding a cone in the raised arm and a bucket in the lowered arm, approaches a spade standard. Like the fish-apkallu discussed under nos. 67-72, the human-apkallu, carrying the same implements, also performs purification or exorcism rites. The apkallu is clad in a slit-robe with no kilt beneath it. While it is not common, human-apkallu can minister to cultic objects in first millennium glyptic. The impression recalls no. 212, showing a Mischwesen tending to a spade-standard” (Ehrenberg, Uruk, 27).

Illustration 2.10. Wingless human-figured ūmu-apkallu. NB stamp seal impression: YBC 3953 (Uruk) Source. Adapted from Ehrenberg, Uruk, pl. 24, no. 191.

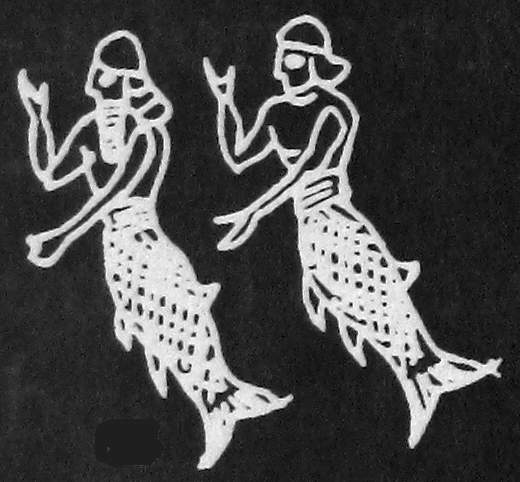

Fish-cloaked apkallu

"The fish-cloaked apkallu is part human and part purādu-fish, “carp.” He has a human body and a bearded human face, with a fish head on top of his human head. The rest of the fish’s body, with caudal and dorsal fins, hangs down his back. His legs and feet can be those of a goat or bull. Combining human intelligence with human and fish capabilities of terrestrial and aquatic survival and locomotion, the supernatural being is amphibious, with access both to the dry land and to the watery Apsu. " (opcit., pp.36-37)

Illustration 2.14. Fish-cloaked apkallu. NB stamp seal impression: YBC 3858 (Uruk) Source. Adapted from Ehrenberg, Uruk, pl. 9, no. 68. "all of these sealings are found on documents relating to transactions archived at the Eanna Temple of Ishtar at Uruk. As suggested in the previous section on ūmu-apkallu, it seems appropriate that apkallu figures, in this case the fish-apkallu, have a significant presence in scenes on seals belonging to temple officials." (opcit., p.39) "In tablet I of the eighth-century-BC Babylonian myth Erra and Ishum, Marduk laments regarding the apkallu: “Where are the Seven Sages of the Apsu, the holy carp, who are perfect in lofty wisdom like Ea their lord, who can make my body holy?...Neo-Babylonians continued to venerate mythical fish sages, who conveyed the basic arts of civilization to the human race. The fish-cloaked apkallu are integrally connected with the divine Ea, god of the Apsu and of wisdom.” (ibid., p.40, p.42)

The bovine

bull-man,

Early Dynastic II - Achaemenid,

kusarikku "bison(-man)" originally associated with the sun-god Shamash

"The so-called wild bull that roamed ancient Mesopotamia was probably identified by the Sumerian term GUD4.ALIM and the Akkadian kusarikku. 1 The wild cattle of the ancient Near East may have been aurochs (Bos primigenius, Ill. 4.1), which are now extinct, but were the probable ancestors of all modern cattle.2 The aurochs was an impressive beast, standing over six feet tall at the shoulder and armed with enormous horns.3 Alternatively, some scholars believe that the ancient wild cattle were more likely bison or wisent (Bison bison caucasicus).4 The wild bovine was portrayed in Mesopotamian iconography since pre-historic times (pre3500 BC) in natural, mythological, and religious contexts.5 Depictions of this natural animal are found in the round, in relief, and in glyptic art well into the Achaemenid period." (ibid., p.67)

Illustration 4.1. Natural bovine: Aurochs (Bos primigenius) "Texts as early as the Early Dynastic II period (c. 2750-2600 BCE) describe Marduk as the “bull-calf” of the sun god, Shamash (UTU). In the Old Babylonian period, the crescent moon could be understood as the horns of a bull that functions as the attribute animal of Sin (NANNA-SUEN).The natural bull is associated with storm deities as early as the Old Babylonian period, and possibly earlier.8 The bull especially functions as the attribute animal of the storm god Adad (ISHKUR). Roiling thunderclouds are referred to as the “bull-calves” of ISHKUR. 9 Bovines are often found in the same contexts as aspects of storms connected with the storm god, such as forked lightning bolts and thunderclouds...Nebuchadnezzar II records in the so-called East India House Inscription (III:36-64) discovered in Babylon (BM 129397) how he elaborately adorns the cellas of Nabu and Sin (here referred to as Nana) in the Ezida temple at Borsippa. Twice he mentions bulls in connection with gates:" (ibid., pp.68-70).

"36. Borsippa the city of his abode 37. I beautified, and 38. Ezida, the Eternal House, 39. in the midst thereof I made. 40. With silver, gold, precious stones, 45. copper, mismakanna-wood, cedar-wood, 42. I finished the work of it. 43. The cedar of the roofing 44. of the cells of Nebo 45. with gold I overlaid. 46. The cedar of the roofing of the gate of Nanâ, 47. I overlaid with shining silver. 48. The bulls, the leaves of the gate of the cell, 49. the lintels, the bars, the bolt, 50. the door-sill, Zarirû-stone. 51. The cedar of the roofing 52. of its chambers (?) 53. with silver I made bright. 54. The path to the cell, 55. and the way to the house, 56. (was of) glazed (?) brickwork. 57. The seat of the chapel therein 58. (was) a work of silver. 59. The bulls, the leaves of the gates, 60. with plates of bronze (?), 61. brightly I made to glisten. 62. The house I made gloriously bright, and, 63. for gazings (of wonder), 64. with carved work I had (it) filled."

The India House Inscription of Nebuchadrezzar the Great,” translated by C. J. Ball in Records of the Past: Being Translations of the Ancient Monuments of Egypt and Western Asia (ed. A. H. Sayce; 2d ser., London: Bagster & Sons, 1890), 110, II:38-65 [cited 24 May 2012] Online: http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/rp/rp203/rp20325.htm.

Later in the same inscription (V:56-VI:21), Nebuchadnezzar describes his construction work in Babylon and his embellishment of that capital city. Here he fabricates bulls and “dreadful serpents” of bronze, and stations them at the gates of the city walls (called Imgur-bel and Nimetti-bel) to make the entrance “unapproachable” to any incursion of evil: Column V 56. Of Imgur-bel 57. and Nimitti-bel 58. the portals, on both sides, 59. through the raising 60. of the causeway of Babylon 61. had become low 62. in their entries: 63. those portals 64. I pulled down, and Column VI 1. over against the water their foundation 2. with bitumen and burnt brick 3. I firmly laid, and 4. with burnt brick (and) gleaming uknû stone, 5. whereof bulls and dreadful serpents 6. were made, the interior of them 7. cunningly I constructed. 8. Strong cedar beams 9. for the roofing of them 10. I laid on. 11. Doors of cedar 12. (with) plating of bronze, 13. lintels and hinges, 14. copper-work, in its gates 15. I set up. 16. Strong bulls of copper, 17. and dreadful serpents, standing upright, 18. on their thresholds I erected: 19. those portals, 20. for the gazings of the multitude of the people, 21. with carven work I caused to be filled. 22. As an outwork 2 for Imgur-bel, 23. the wall of Babylon, unapproachable. (loc.cit., ibid., p.69)

"A second royal inscription of Nebuchadnezzar II (CBS 9), known as the “University Museum Cylinder,” describes in elaborate detail the bronze bulls “clothed” in gold and bulls made of silver that he placed at the Ezida temple in Borsippa (col. I): (36) In Borsippa I restored Ezida the righteous house beloved of Marduk for Nabu the illustrious son . . . (52) As for the six rooms adjoining the shrine of Nabu I adorned their cedar roof with bright silver . . . (55) I fabricated huge bulls in bronze and I clothed them with a coating of gold and adorned them with precious stones and I placed them on the threshold of the shrine gate. The threshold, the fetter, the bar, the doorwings, the lintel, the knob(?), the lock, the bolt of the shrine gate I plated with shining gold. . . (60) I covered with clear silver the cedar wood of the roof of the Dara gate through which goes and comes the son of the lord of the gods . . . (62) I fabricated huge bulls of silver and I placed them on its threshold. This gate where through goes and comes the son of the lord of the gods Nabu, when he rides in procession into Babylon, I let shine like the day. . . (65) Bulls of shining silver I planted as ornament on the threshold of the gates of Ezida.14 In the same text, the Babylonian monarch states that he put monumental bronze bulls at the gates of Babylon (II:1-2): (1) In Babylon the city of the great lord Marduk I completed the great walls Imgur-Bel and Nimitti-Bel. (2) On the threshold of their gates I placed huge bronze bulls and dread inspiring dragons.15 Bull imagery in extant NB iconography is best exemplified in relief on the walls of the famous Ishtar Gate at the entrance of sixth-century-BC Babylon. Nebuchadnezzar II describes the construction of this structure in his “Dedicatory Inscription” on a glazed brick panel of the gate: Both gate entrances of Imgur-Ellil and Nemetti-Ellil following the filling of the street from Babylon had become increasingly lower. Therefore, I pulled down these gates and laid their foundations at the water-table with asphalt and bricks and had them made of bricks with blue stone on which wonderful bulls and dragons were depicted. I covered their roofs by laying majestic cedars length-wise over them. I hung doors of cedar adorned with bronze at all the gate openings. I placed wild bulls and ferocious dragons in the gateways and thus adorned them with luxurious splendor so that people might gaze on them in wonder.16 The colossal guardian bulls and dragons in the round from the Ishtar Gate have not survived, but those rendered in glazed-brick relief are preserved and exhibited at the Vorderasiatisches Museum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (e.g., Ill. 4.2). Remnants of unglazed reliefs from the gate structure remain in situ in Babylon." (ibid., pp. 69-71)

Illustration 4.2. Natural Bovine: Bull of Adad. NB glazed brick relief: VA Bab 1976 (Ishtar Gate, Babylon)

Illustration 2.1. Four-winged human-figured ūmu-apkallu. NB cylinder seal: CBS 8933 (Nippur) Source. Adapted from Beatrice Wittmann, “Babylonische Rollsiegel des 11.-7. Jahrhunderts v. Chr.” BaM 23, (1992), 247, no. 117. Erica Ehrenberg, Uruk: Late Babylonian Seal Impressions on Eanna-Tablets (AUWE 18; Mainz: Zabern, 1999), 94. On a 7th-cent.-BC bronze breastplate, a wingless ūmu-apkallu faces right toward a winged ūmu-apkallu, which is facing left. To the left of this winged figure is a fish-cloaked apkallu. The breastplate, now housed in Karlsruhe, Badisches Landesmuseum, is discussed in Dalley, “Apkallu,” IDD, 3.

"The bull-man takes over the name of the natural bovine: Sumerian GUD4.ALIM, the Akkadian equivalent of which is kusarikku. 21 The kusarikku is solidly attested in the NeoBabylonian period on two cylinder seals (Ills. 4.3-4.4), five seal impressions (Ills. 4.5-4.9), and on the Sun-god Tablet Collection, which consists of a tablet and two plaster casts of the head of this tablet, which were placed within a lidded coffer (Ills. 4.10-4.13). Illustration 4.3. Bull-man (kusarikku): Judgment or worship scene. NB cylinder seal: VA Bab 1510 (Babylon) Source. Adapted from Anton Moortgat, Vorderasiatische Rollsiegel: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Steinschneidekunst (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1988), 67, 140, no. 600.

"The bull-man is extant in iconography by the Early Dynastic II period as the protector of flocks and herds. In glyptic art of this period, bull-men appear in contest scenes, whether depicted alone, in pairs, or in threes as they struggle against wild animals or humans. Early Dynastic III period (c. 2600-2300 BC) glyptic scenes portray the bull-man fighting Lahmu, the hero with curls. This contest became the most common theme of Akkadian period (c. 2330-2190 BC) glyptic art. Also on Akkadian period seals, the bull-man is shown as an adversary to the sun god, UTU: With rebellious mountain gods, he fought against UTU, who was the supervisor of the distant regions, along with INANNA. However, during the Akkadian period, the bull-man’s association with UTU is transformed into a master-servant relationship, so he becomes a protective figure at significant entrances...The NB bull-man continued functions exhibited in earlier periods. These include guarding against intrusion by malevolent forces and attending the sun god Shamash by supporting his throne and winged disk. Because Shamash is the god of justice, the bull-man plays a subordinate role in the administration of justice.60 Additionally, the bull-man can be associated with an apkallu, who performs a purification ritual in what appears to be a judicial context. (ibid., pp.80-83)

Illustration 5.1. Winged genius against two natural lions: Contest scene. NB cylinder seal: VA 6938 (Bab 36292) (Babylon, Merkes) Source. Adapted from Anton Moortgat, Vorderasiatische Rollsiegel: Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der Steinschneidekunst (Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1988), 74, no. 735.

Illustration 5.2. Lion. NB glazed brick relief: VA Bab 4765 (Ishtar Gate, Babylon)

"The best-known lion imagery in NB iconography is on the magnificent glazed brick reliefs lining the Processional Way and on the throne room façade of the Southern Palace in sixthcentury-BC Babylon (Ill. 5.2). In both of these locations, rows of natural lions stride in profile, emphasizing their apotropaic function. Thus, on the outer façade flanking the entrance to the throne room from the Central Court, the lions stride from the left and from the right toward the entrance through which an individual must pass to reach the king on his throne. On the reliefs lining the Processional Way, the lions pace northward, away from the Ishtar Gate and toward anyone approaching it. (Joachim Marzahn, The Ishtar Gate: The Processional Way: The New Year Festival of Babylon (Mainz: Zabern, 1994), 9.)(opcit., pp.94-95)

Lion-sickle indicates that the implement is made of arye 'lion' rebus: āra 'brass'

Illustration 5.5. Lion mace. NB stamp impression: GCBC 59 (Uruk) Source. Adapted from Erica Ehrenberg, Uruk: Late Babylonian Seal Impressions on Eanna-Tablets (AUWE 18; Mainz: Zabern, 1999), pl. 2, no. 12."The lion mace is called d Urigallu, with the divine determinative. It is most notably the standard of Ishtar and supports her star The emblem is less frequently associated with Ningirsu. It is additionally attested as the standard of Nergal and Zababa.20 Since these four deities are warlike, it is not surprising that d Urigallu is closely associated with scenes of war in iconography." (ibid. p.97)

Occasionally in NeoBabylonian iconography, a divine lion-headed emblem, depicting only the head of a natural lion on a sickle, surmounts an altar in a scene of worship (Ills. 5.3-5.4). In both of the extant provenanced examples, the lion sickle appears in front of a worshiper, whose right hand is raised in adoration. Also in both, there is an oblong object on a second altar, surmounted by a crescent, between the worshiper and the lion sickle. Illustration 5.3. Lion sickle. NB cylinder sealing: HSM 890.4.8 (Babylon) Source. Adapted from Paul-Alain Beaulieu, Legal and Administrative Texts from the Reign of Nabonidus (YOSBT 19; New Haven: Yale University Press, 2000), 7, pl. L, no. 5, text 101.(opcit., p.95)

Illustration 11.5. Mušḫuššu. NB glazed brick relief: VA Bab 4431 (Babylon, Ishtar Gate)

Illustration 11.22. Mušḫuššu: Worship scene. NB cylinder seal: BM 89324 (Babylon, SE Palace) Source. Adapted from Klengel-Brandt, Mit Sieben Siegeln Versehen, 103, Abb. 104.

Illustration 11.8. Marduk with mušḫuššu. NB seal: VA Bab 646 (Babylon) Source. Adapted from Evelyn Klengel-Brandt, ed., Mit Sieben Siegeln Versehen: Das Siegel in Wirtschaft und Kunst des Alten Orients (Mainz: Zabern, 1997), 100, Abb. 99.The personal seal of Marduk (VA Bab 646, Babylon; Ill. 11.8), city god of Babylon, depicts the god and his recumbent sacred animal, the mušḫuššu dragon. Marduk is garbed in an ornate robe covered with divine symbols.36 He holds his left hand, which grasps the rod and ring of kingship, against his right breast. His lowered right hand holds a scimitar. The mušḫuššu, recumbent at his feet, has two prominent horns and ears, a curled and hissing tongue, and is covered with a heavy coat of scales. Along the dragon’s neck is a mane. Both the deity and the creature are supported by a plinth evoking water, presumably representing the Apsu, which reflects the close connection between Marduk, the mušḫuššu, and the sea....a single stylus of Nabu on the back of a mušḫuššu is common.(ibid., pp.208-210).

"The overall picture shows a vast and variegated cosmic community inhabited by many kinds of beings and creatures, including gods, subdivine supernatural beings (including demons, monsters, and dragons), humans, and animals (including fish and birds)." (Ibid., p.227).

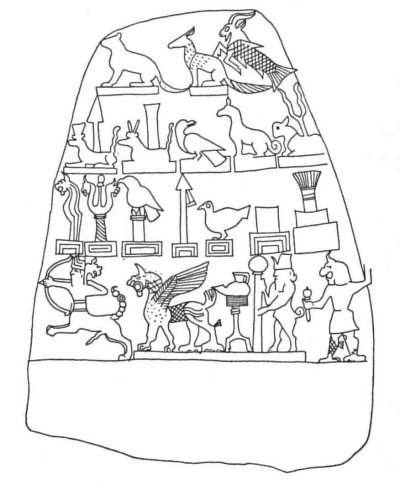

What are kudurrus?

Kudurrus are stelas or stone (or clay) slabs (called nargus or asumittu, "inscribed slab," and abnu, "stone." by the Babylonians) with inscriptions, generally of land grants, boundary markers.

Ignace Gelb et al detailt the functions of the kudurrus as documents of land tenure systems of the Bronze Age. [Ignace Gelb, Piotr Steinkeller, and Robert Whiting Jr., 1991, Earliest Land Tenure Systems in the Near East: Ancient Kudurrus by Ignace Gelb, Piotr Steinkeller, and Robert Whiting Junior (1989-1991, 2 Parts: Part 1: Text, Part 2: Plates)].

Giorgio Buccellati details field and/or temple placement of kudurrus. (Giorgio Buccellati, 1994, The Kudurrus as Monuments in: Cinquante-deux reflexions sur le Proche-Orient ancien offertes en hommage a Leon de Meyer, Pages 283-291).

Kathryn Slanski presents an 'administrative' view on the purpose of kudurrus. (Kathryn Slanski, 2000, Classification, Historiography and Monumental Authority: The Babylonian Entitlement Narus (Kudurrus), in: Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Volume 52, 2000, Pages 95-114).

Brinkman provides an economic interpretation that kudurrus were not legal documents - but mere commemoration/markers of the acquisition of land (perpetual income). (John Brinkman, 2006, Babylonian royal land grants, memorials of financial interest, and invocation of the divine, in: Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient [JESHO], Volume 49, 2006, Pages 1-47).

Indus Script hieroglyphs on Kassite hypertexts on kudurrus are sacred memories of Bronze Age artisanal activities Mirror: https://tinyurl.com/y9umwwldWith this background of links between Syria/Kassites with Indo-Aryan, it is instructive to find many Indus Script hieroglyphs on Kassite kudurrus.

Examples of Kassite kudurru hypertexts deploying Indus Script hieroglyphs are presented in this monograph.

Scorpion hieroglyph on a kudurru. Indus Script: bicha 'scorpion' Rebus: bica 'hematite, sandstone ferrite ore'

![]() Hieroglyph: फडा (p. 313) phaḍā f (फटा S) The hood of Coluber Nága &c. Ta. patam cobra'shood. Ma. paṭam id. Ka. peḍe id. Te. paḍaga id. Go. (S.) paṛge, (Mu.) baṛak, (Ma.) baṛki, (F-H.) biṛki hood of serpent (Voc. 2154). / Turner, CDIAL, no. 9040, Skt. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā- id. For IE etymology, see Burrow, The Problem of Shwa in Sanskrit, p. 45.(DEDR 47) Rebus: phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office’, keeper of all accounts, registers.फडपूस (p. 313) phaḍapūsa f (फड & पुसणें) Public or open inquiry. फडफरमाश or स (p. 313) phaḍapharamāśa or sa f ( H & P) Fruit, vegetables &c. furnished on occasions to Rajas and public officers, on the authority of their order upon the villages; any petty article or trifling work exacted from the Ryots by Government or a public officer.

Hieroglyph: फडा (p. 313) phaḍā f (फटा S) The hood of Coluber Nága &c. Ta. patam cobra'shood. Ma. paṭam id. Ka. peḍe id. Te. paḍaga id. Go. (S.) paṛge, (Mu.) baṛak, (Ma.) baṛki, (F-H.) biṛki hood of serpent (Voc. 2154). / Turner, CDIAL, no. 9040, Skt. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā- id. For IE etymology, see Burrow, The Problem of Shwa in Sanskrit, p. 45.(DEDR 47) Rebus: phaḍa फड ‘manufactory, company, guild, public office’, keeper of all accounts, registers.फडपूस (p. 313) phaḍapūsa f (फड & पुसणें) Public or open inquiry. फडफरमाश or स (p. 313) phaḍapharamāśa or sa f ( H & P) Fruit, vegetables &c. furnished on occasions to Rajas and public officers, on the authority of their order upon the villages; any petty article or trifling work exacted from the Ryots by Government or a public officer.

eraka 'upraised arm' rebus: eraka 'moltencast copper' arka 'gold'.- Ram atop temple on a kudurru. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam)

![]() Akkadian - Late Babylonian,

Akkadian - Late Babylonian,

possibly ûmu naa´iru "roaring weather-beast". arya 'lion' rebus: ara 'brass'; khamba 'wings' rebus: kammata 'mint'.

![]() Fish-anthropomorphs. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'

Fish-anthropomorphs. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'![]() Goat-fish-fin hypertext. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage' PLUS mr̤eka, melh 'goat' (Telugu. Brahui) Rebus: melukkha 'milakkha, copper'. meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam) The expression signifies a copper-metal (iron) mint, smith/merchant.

Goat-fish-fin hypertext. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage' PLUS mr̤eka, melh 'goat' (Telugu. Brahui) Rebus: melukkha 'milakkha, copper'. meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam) The expression signifies a copper-metal (iron) mint, smith/merchant.![Babylonia at the Time of the Kassites]()

![]() Kudurru recording Eanna-shum-iddina's land grant, British Museum. Eanna-shum-iddina was a governor in the Sealand Dynasty of Babylon in the middle of the second millennium BC. Sealand was the region of southern Iraq, of the Tigris-Euphrates-(Mesopotamia) along the coast. Eanna-shum-iddina is known to have made at least one Kudurruboundary stone.The "Eanna-shum-iddina kudurru" was a land grant to Gula-eresh, witnessed by his surveyor Amurru-bel-zeri.The British Museum dates this kudurru to 1125-1100 BC:

Kudurru recording Eanna-shum-iddina's land grant, British Museum. Eanna-shum-iddina was a governor in the Sealand Dynasty of Babylon in the middle of the second millennium BC. Sealand was the region of southern Iraq, of the Tigris-Euphrates-(Mesopotamia) along the coast. Eanna-shum-iddina is known to have made at least one Kudurruboundary stone.The "Eanna-shum-iddina kudurru" was a land grant to Gula-eresh, witnessed by his surveyor Amurru-bel-zeri.The British Museum dates this kudurru to 1125-1100 BC:![]() Walters Art Museum no. 2110 kudurru A "kudurru," the Akkadian term for boundary stone, combines images of the king, gods, and divine symbols with a text recording royal grants of land and tax exemption to an individual. While the original was housed in the temple, a copy of the document was kept at the site of the land in question. This example was found at the temple of Esagila, the primary sanctuary of the god Marduk. The king Marduk-nadin-ahe is depicted with his left hand raised in front of his face; he wears the tall Babylonian feathered crown and an elaborately decorated garment with a honeycomb pattern. On the top are a sun disk, star, crescent moon, and scorpion, representing deities who witnessed the land grant and tax exemption. A snake-dragon deity emerges from a row of altars shaped like temple façades along the back.

Walters Art Museum no. 2110 kudurru A "kudurru," the Akkadian term for boundary stone, combines images of the king, gods, and divine symbols with a text recording royal grants of land and tax exemption to an individual. While the original was housed in the temple, a copy of the document was kept at the site of the land in question. This example was found at the temple of Esagila, the primary sanctuary of the god Marduk. The king Marduk-nadin-ahe is depicted with his left hand raised in front of his face; he wears the tall Babylonian feathered crown and an elaborately decorated garment with a honeycomb pattern. On the top are a sun disk, star, crescent moon, and scorpion, representing deities who witnessed the land grant and tax exemption. A snake-dragon deity emerges from a row of altars shaped like temple façades along the back.

Turtle atop a temple on kudurru. Indus Script: kamaṭha 'turtle' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage'

eraka 'upraised arm' rebus: eraka 'moltencast copper' arka 'gold'.

- Ram atop temple on a kudurru. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS miṇḍāl 'markhor' (Tōrwālī) meḍho a ram, a sheep (Gujarati)(CDIAL 10120) Rebus: mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Munda.Ho.) meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam)

Akkadian - Late Babylonian,

Akkadian - Late Babylonian,possibly ûmu naa´iru "roaring weather-beast". arya 'lion' rebus: ara 'brass'; khamba 'wings' rebus: kammata 'mint'.

Fish-anthropomorphs. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal'

Fish-anthropomorphs. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' Goat-fish-fin hypertext. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage' PLUS mr̤eka, melh 'goat' (Telugu. Brahui) Rebus: melukkha 'milakkha, copper'. meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam) The expression signifies a copper-metal (iron) mint, smith/merchant.

Goat-fish-fin hypertext. Indus Script: ayo 'fish' rebus: aya 'iron' ayas 'alloy metal' PLUS khambhaṛā fish-fin' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner, coinage' PLUS mr̤eka, melh 'goat' (Telugu. Brahui) Rebus: melukkha 'milakkha, copper'. meḍh 'helper of merchant' (Prakrtam) The expression signifies a copper-metal (iron) mint, smith/merchant.

Kudurru recording Eanna-shum-iddina's land grant, British Museum. Eanna-shum-iddina was a governor in the Sealand Dynasty of Babylon in the middle of the second millennium BC. Sealand was the region of southern Iraq, of the Tigris-Euphrates-(Mesopotamia) along the coast. Eanna-shum-iddina is known to have made at least one Kudurruboundary stone.

Kudurru recording Eanna-shum-iddina's land grant, British Museum. Eanna-shum-iddina was a governor in the Sealand Dynasty of Babylon in the middle of the second millennium BC. Sealand was the region of southern Iraq, of the Tigris-Euphrates-(Mesopotamia) along the coast. Eanna-shum-iddina is known to have made at least one Kudurruboundary stone.The "Eanna-shum-iddina kudurru" was a land grant to Gula-eresh, witnessed by his surveyor Amurru-bel-zeri.

The British Museum dates this kudurru to 1125-1100 BC:

Walters Art Museum no. 2110 kudurru A "kudurru," the Akkadian term for boundary stone, combines images of the king, gods, and divine symbols with a text recording royal grants of land and tax exemption to an individual. While the original was housed in the temple, a copy of the document was kept at the site of the land in question. This example was found at the temple of Esagila, the primary sanctuary of the god Marduk. The king Marduk-nadin-ahe is depicted with his left hand raised in front of his face; he wears the tall Babylonian feathered crown and an elaborately decorated garment with a honeycomb pattern. On the top are a sun disk, star, crescent moon, and scorpion, representing deities who witnessed the land grant and tax exemption. A snake-dragon deity emerges from a row of altars shaped like temple façades along the back.

Walters Art Museum no. 2110 kudurru A "kudurru," the Akkadian term for boundary stone, combines images of the king, gods, and divine symbols with a text recording royal grants of land and tax exemption to an individual. While the original was housed in the temple, a copy of the document was kept at the site of the land in question. This example was found at the temple of Esagila, the primary sanctuary of the god Marduk. The king Marduk-nadin-ahe is depicted with his left hand raised in front of his face; he wears the tall Babylonian feathered crown and an elaborately decorated garment with a honeycomb pattern. On the top are a sun disk, star, crescent moon, and scorpion, representing deities who witnessed the land grant and tax exemption. A snake-dragon deity emerges from a row of altars shaped like temple façades along the back.This magnificent object is a Kudurru, a carved stone used to mark a royal land grant. Old books call them "boundary stones", but they were kept in the palace or temple archives, not placed out on the borders of the grant. This one comes from Babylon, the Second Dynasty of Isin, 1157-1025 BC; I found it in an online exhibit at the California Museum of Ancient Art.This stone is carved of black limestone, 16.5 inches tall (42 cm). The designs are full of significance. On the front:the Mesopotamian pantheon is presented. The four great gods come first. Anu ("father of the gods" and god of heaven) and Enlil (god of wind, kingship and the earth), are shown as a multi-horned divine crown each on its own temple facade. Then Ea (god of water, magic and wisdom), is shown as a curved stick ending in a ram's head atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a horned goat. Above the first two deities, a female headdress in the shape of an omega sign, symbolizes Ninhursag ("mother of the gods" and goddess of fertility).

Reverse:The leading Babylonian god, Marduk, and his son Nabu, appear next. A triangular spade pointing up and a scribe's wedge-shaped stylus, respectively, each sits atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a snake-dragon known as a Mushus. All five temple facades float on fresh, underground waters known as the Apsu or the Deep. Following these divinities, we find the mace, perhaps a local war god, the scepter with double lion heads of Ninurta (god of war), the arrow, a symbol of the star Sirius, and the two-pronged lightning bolt of Adad. This storm god is called by the similar name Haddad in the Levant. The running bird Papsukkal (minister of the gods, associated with the constellation Orion), is followed by the scorpion Ishara (goddess of oaths), the seated dog Gula (goddess of healing) and a bird on a perch, symbolizing both Shuqamuna and Shumalia (patron deities of the Kassite royal family).

Top:The top of the kudurru, representing the heavens, is surrounded and enclosed by the body of a large snake. Nirah (the snake god) encompasses four astral deities the crescent moon of Sin (the moon god), a multi-rayed circular sun disc of Shamash (the sun god), a star inside a disc for Ishtar (the goddess of love -especially sexuality- and war) and the lamp of Nusku (the god of fire and light). Ishtar, considered the most important Mesopotamian female deity, is associated with the morning and evening star, the planet Venus.

http://cmaa-museum.org/meso01.html The website of the California Museum of Ancient Art includes the following excerpted document introducing kudurrus:

http://cmaa-museum.org/kudurru.pdf

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

A Gathering of the Gods - the Power of Mesopotamian Religion

Mesopotamian Black Limestone Kudurru

Mesopotamia; Second Dynasty of Isin, 1157-1025 BC; Height 16.5 inchesThe upper section of this finely polished black limestone kudurru is decorated in intricately carved raised relief with symbols and sacred animals representing a large group or "gathering" of Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. Kudurrus, sometimes referred to as "boundary markers," were actually land grant documents used by kings to reward their favored servants. These monuments were set up in temples to record royal land grants. The full force of the Mesopotamian pantheon was utilized both to witness and guarantee the land grant by carving the symbols and sacred animals of the deities on the kudurru. In the shape of a cylindrical ovoid, this particular kudurru was not inscribed, perhaps because the person who was to receive the land grant died before it could be finalized, or because the king changed his mind and decided not to make the land grant after all. Each kudurru is unique; a good deal of variation exists in the number and choice of deities which appear.

Front:On this standing monument, the Mesopotamian pantheon is presented. The four great gods come first. Anu ("father of the gods" and god of heaven) and Enlil (god of wind, kingship and the earth), are shown as a multi-horned divine crown each on its own temple facade. Then Ea (god of water, magic and wisdom), is shown as a curved stick ending in a ram's head atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a horned goat. Above the first two deities, a female headdress in the shape of an omega sign, symbolizes Ninhursag ("mother of the gods" and goddess of fertility).

Reverse:The leading Babylonian god, Marduk, and his son Nabu, appear next. A triangular spade pointing up and a scribe's wedge-shaped stylus, respectively, each sits atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a snake-dragon known as a Mushus. All five temple facades float on fresh, underground waters known as the Apsu or the Deep. Following these divinities, we find the mace, perhaps a local war god, the scepter with double lion heads of Ninurta (god of war), the arrow, a symbol of the star Sirius, and the two-pronged lightning bolt of Adad. This storm god is called by the similar name Haddad in the Levant. The running bird Papsukkal (minister of the gods, associated with the constellation Orion), is followed by the scorpion Ishara (goddess of oaths), the seated dog Gula (goddess of healing) and a bird on a perch, symbolizing both Shuqamuna and Shumalia (patron deities of the Kassite royal family).

Top:The top of the kudurru, representing the heavens, is surrounded and enclosed by the body of a large snake. Nirah (the snake god) encompasses four astral deities the crescent moon of Sin (the moon god), a multi-rayed circular sun disc of Shamash (the sun god), a star inside a disc for Ishtar (the goddess of love -especially sexuality- and war) and the lamp of Nusku (the god of fire and light). Ishtar, considered the most important Mesopotamian female deity, is associated with the morning and evening star, the planet Venus.![Unfinished Kudurru from the Reign of Melishipak, found in Sousa. Louvre, Paris]() Unfinished Kudurru from the Reign of Melishipak, found in Sousa. Louvre, Paris

Unfinished Kudurru from the Reign of Melishipak, found in Sousa. Louvre, Paris![]() Melli-shipak Kudurru

Melli-shipak Kudurru![MeliÅ¡ipak kudurru-Land grant to Hunnubat-Nannaya. Louvre, Paris]() Melišipak kudurru-Land grant to Hunnubat-Nannaya. Louvre, Paris

Melišipak kudurru-Land grant to Hunnubat-Nannaya. Louvre, Paris

Kudurru of Melishihu. Louvre, Paris. Boundary markers for property are a very old concept. They are mentioned in the Bible: Proverbs 22:28 “Do not move an ancient boundary stone set up by your forefathers.”![Pantheon of Kassite Gods. Melishipak kudurru-Land grant to Marduk-apla-iddina]()

![Related image]() Kudurru of Mellishuhu. Louvre.

Kudurru of Mellishuhu. Louvre.

Moonhieroglyph on a kudurru. Indus Script: مر ḳamar A قمر ḳamar, s.m. (9th) The moon. Sing. and Pl. See سپوږمي or سپوګمي (Pashto) rebus: kamar 'artisan, smith' (Santali) Arrow atop a temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS Oriya. kāṇḍa, kã̄ṛ ʻstalk, arrow ʼ(CDIAL 3023). ayaskāṇḍa 'a quantity of iron; kāṇḍa 'implements' NOTE: The Indus Script expression kole.l which signifies a temple is significant. Since kole.l is a smithy, forge', the activities related to metalwork gain sacredness and veneration as products realized in a temple. Hence, the Kassite kudurrus equate metalwork hieroglyphs and express veneration of ancestors who were metalworkers with divinities (as signified on the hieroglyphs used on kudurrus). The divinities for Kassites are: (1) Anu, (2) Enlil, (3) Ea, (4) Ninmakh, (5) Sin, (6) Nabu, (7) Gula, (8) Ninib, and (9) Marduk.

Tiger-head atop a temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'Rim-of-jar (upside down) atop temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS karṇika, kanka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karṇI 'supercaro, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale'.'A rod (signifying 'one') atop temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'

Sun's rays hieroglyph on kudurrus. Indus Script: arka 'sun' rebus: arka, eraka 'copper'. Star hieroglyph on kudurru. Indus Script: mēḍha मेढ 'polar star' (Marathi) rebus: मृदु mṛdu, mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Samskrtam, Santali. Mu.Ho.)

![]() Black drongo atop a pillar on a kudurru. Indus Script: pōlaḍu 'black drongo' signify polad 'steel' PLUS skambha 'pillar' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint', coiner, coinage

Black drongo atop a pillar on a kudurru. Indus Script: pōlaḍu 'black drongo' signify polad 'steel' PLUS skambha 'pillar' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint', coiner, coinage ![]() Duck atop a temple on a kudurru. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS karaṇḍa 'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa 'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā]Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

Duck atop a temple on a kudurru. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS karaṇḍa 'duck' (Sanskrit) karaṛa 'a very large aquatic bird' (Sindhi) Rebus: करडा [karaḍā]Hard from alloy--iron, silver &c. (Marathi)

Tree atop a temple on a kudurru. Indus Script:kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS kuṭhi a sacred, divine tree, kuṭi 'temple'; kuṭhi 'smelter' Tree and bull on a kudurru. Indus Script: kuṭhi a sacred, divine tree, kuṭi'temple'; kuṭhi 'smelter' PLUS ḍhaṅgaru, ḍhiṅgaru m. ʻlean emaciated beastʼ(Sindhi) Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili)

kudurru stones of the Kassite Period (circa 1530-1155/1160 BCE) includes the following hieroglyphs:![Related image]()

![Image result for Kudurru]()

![Related image]() Meli-Šipak kudurru, 1186–1172. pr. Kr. Goat-fish

Meli-Šipak kudurru, 1186–1172. pr. Kr. Goat-fish![]() Kudurru fragments. With mushhushshu.

Kudurru fragments. With mushhushshu.

Lion

Goat-Fish![Limestone kudurru reign of Marduk-nadin-ahhe: the boundary-stone consists of a block of black limestone, which has been shaped and rubbed down to take sculptures and inscriptions. Culture/period: Middle Babylonian Date: 11thC BC From: Babylon (Asia, Middle East, Iraq, South Iraq, Babylon) Materials: limestone Technique: carved British Museum number: 90841]() Limestone kudurru reign of Marduk-nadin-ahhe: the boundary-stone consists of a block of black limestone, which has been shaped and rubbed down to take sculptures and inscriptions. Culture/period: Middle Babylonian Date: 11thC BC From: Babylon (Asia, Middle East, Iraq, South Iraq, Babylon) Materials: limestone Technique: carved British Museum number: 90841

Limestone kudurru reign of Marduk-nadin-ahhe: the boundary-stone consists of a block of black limestone, which has been shaped and rubbed down to take sculptures and inscriptions. Culture/period: Middle Babylonian Date: 11thC BC From: Babylon (Asia, Middle East, Iraq, South Iraq, Babylon) Materials: limestone Technique: carved British Museum number: 90841![Blog dedicated to the greatest ancient culture - Mesopotamia.]()

![Related image]()

![]()

Kudurru recording the bequest of land by Marduk-zâkir-šumi to Ibni-Ištar on behalf of the Eanna temple in Uruk [i 1] Reign c. 855 – 819 BC Predecessor Nabû-apla-iddina Successor Marduk-balāssu-iqbi

![Image result for Kudurru]()

![Related image]()

![]()

![]()

![Related image]() Limestone boundary-stone (kudurru) from the time of Nabu-mukin-apli

Limestone boundary-stone (kudurru) from the time of Nabu-mukin-apli![Image result for Kudurru]()

![File:Unfinished kudurru h9097.jpg]() Unfinished kudurru (boundary marker) with a horned serpent (symbol of Marduk) around pillar at bottom. The most proeminent gods are featured as symbols. The space for the inscription was left Accession No. Sb25 Louvre Museum.

Unfinished kudurru (boundary marker) with a horned serpent (symbol of Marduk) around pillar at bottom. The most proeminent gods are featured as symbols. The space for the inscription was left Accession No. Sb25 Louvre Museum.Kudurru "inachevé" Époque kassite, attribué au règne de Meli-Shipak (1186-1172 av. J.-C.) Découvert à Suse où il avait été emporté en butin de guerre au XIIe siècle avant J.-C. Calcaire Sous les anneaux du serpent qui s'enroule sur le sommet sont figurées les principales divinités du panthéon sous forme de symboles. Au-dessous, un cortège de dieux musiciens et d'animaux. Murs et tours crénelées encadrent l'emplacement réservé à une inscription qui n'a jamais été gravée. Un serpent cornu, emblème du dieu Marduk, entoure la base. Fouilles J. de Morgan Département des Antiquités orientales http://cartelen.louvre.fr/cartelen/visite?srv=car_not_frame&idNotice=24649

![Related image]() “Kudurru or a boundary stone from Babylon dating back to 1099-1082 BCE. The Kudurru was found at the Temple of Esagila in Babylon. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD.

“Kudurru or a boundary stone from Babylon dating back to 1099-1082 BCE. The Kudurru was found at the Temple of Esagila in Babylon. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD.

This magnificent object is a Kudurru, a carved stone used to mark a royal land grant. Old books call them "boundary stones", but they were kept in the palace or temple archives, not placed out on the borders of the grant. This one comes from Babylon, the Second Dynasty of Isin, 1157-1025 BC; I found it in an online exhibit at the California Museum of Ancient Art.This stone is carved of black limestone, 16.5 inches tall (42 cm). The designs are full of significance. On the front:

Reverse:

the Mesopotamian pantheon is presented. The four great gods come first. Anu ("father of the gods" and god of heaven) and Enlil (god of wind, kingship and the earth), are shown as a multi-horned divine crown each on its own temple facade. Then Ea (god of water, magic and wisdom), is shown as a curved stick ending in a ram's head atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a horned goat. Above the first two deities, a female headdress in the shape of an omega sign, symbolizes Ninhursag ("mother of the gods" and goddess of fertility).

Reverse:

The leading Babylonian god, Marduk, and his son Nabu, appear next. A triangular spade pointing up and a scribe's wedge-shaped stylus, respectively, each sits atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a snake-dragon known as a Mushus. All five temple facades float on fresh, underground waters known as the Apsu or the Deep. Following these divinities, we find the mace, perhaps a local war god, the scepter with double lion heads of Ninurta (god of war), the arrow, a symbol of the star Sirius, and the two-pronged lightning bolt of Adad. This storm god is called by the similar name Haddad in the Levant. The running bird Papsukkal (minister of the gods, associated with the constellation Orion), is followed by the scorpion Ishara (goddess of oaths), the seated dog Gula (goddess of healing) and a bird on a perch, symbolizing both Shuqamuna and Shumalia (patron deities of the Kassite royal family).Top:

The top of the kudurru, representing the heavens, is surrounded and enclosed by the body of a large snake. Nirah (the snake god) encompasses four astral deities the crescent moon of Sin (the moon god), a multi-rayed circular sun disc of Shamash (the sun god), a star inside a disc for Ishtar (the goddess of love -especially sexuality- and war) and the lamp of Nusku (the god of fire and light). Ishtar, considered the most important Mesopotamian female deity, is associated with the morning and evening star, the planet Venus.

http://cmaa-museum.org/meso01.html The website of the California Museum of Ancient Art includes the following excerpted document introducing kudurrus:

http://cmaa-museum.org/kudurru.pdf

A Gathering of the Gods - the Power of Mesopotamian Religion

Mesopotamian Black Limestone Kudurru

Mesopotamia; Second Dynasty of Isin, 1157-1025 BC; Height 16.5 inchesThe upper section of this finely polished black limestone kudurru is decorated in intricately carved raised relief with symbols and sacred animals representing a large group or "gathering" of Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. Kudurrus, sometimes referred to as "boundary markers," were actually land grant documents used by kings to reward their favored servants. These monuments were set up in temples to record royal land grants. The full force of the Mesopotamian pantheon was utilized both to witness and guarantee the land grant by carving the symbols and sacred animals of the deities on the kudurru. In the shape of a cylindrical ovoid, this particular kudurru was not inscribed, perhaps because the person who was to receive the land grant died before it could be finalized, or because the king changed his mind and decided not to make the land grant after all. Each kudurru is unique; a good deal of variation exists in the number and choice of deities which appear.

Front:On this standing monument, the Mesopotamian pantheon is presented. The four great gods come first. Anu ("father of the gods" and god of heaven) and Enlil (god of wind, kingship and the earth), are shown as a multi-horned divine crown each on its own temple facade. Then Ea (god of water, magic and wisdom), is shown as a curved stick ending in a ram's head atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a horned goat. Above the first two deities, a female headdress in the shape of an omega sign, symbolizes Ninhursag ("mother of the gods" and goddess of fertility).

Reverse:The leading Babylonian god, Marduk, and his son Nabu, appear next. A triangular spade pointing up and a scribe's wedge-shaped stylus, respectively, each sits atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a snake-dragon known as a Mushus. All five temple facades float on fresh, underground waters known as the Apsu or the Deep. Following these divinities, we find the mace, perhaps a local war god, the scepter with double lion heads of Ninurta (god of war), the arrow, a symbol of the star Sirius, and the two-pronged lightning bolt of Adad. This storm god is called by the similar name Haddad in the Levant. The running bird Papsukkal (minister of the gods, associated with the constellation Orion), is followed by the scorpion Ishara (goddess of oaths), the seated dog Gula (goddess of healing) and a bird on a perch, symbolizing both Shuqamuna and Shumalia (patron deities of the Kassite royal family).

Top:The top of the kudurru, representing the heavens, is surrounded and enclosed by the body of a large snake. Nirah (the snake god) encompasses four astral deities the crescent moon of Sin (the moon god), a multi-rayed circular sun disc of Shamash (the sun god), a star inside a disc for Ishtar (the goddess of love -especially sexuality- and war) and the lamp of Nusku (the god of fire and light). Ishtar, considered the most important Mesopotamian female deity, is associated with the morning and evening star, the planet Venus.

Mesopotamia; Second Dynasty of Isin, 1157-1025 BC; Height 16.5 inchesThe upper section of this finely polished black limestone kudurru is decorated in intricately carved raised relief with symbols and sacred animals representing a large group or "gathering" of Mesopotamian gods and goddesses. Kudurrus, sometimes referred to as "boundary markers," were actually land grant documents used by kings to reward their favored servants. These monuments were set up in temples to record royal land grants. The full force of the Mesopotamian pantheon was utilized both to witness and guarantee the land grant by carving the symbols and sacred animals of the deities on the kudurru. In the shape of a cylindrical ovoid, this particular kudurru was not inscribed, perhaps because the person who was to receive the land grant died before it could be finalized, or because the king changed his mind and decided not to make the land grant after all. Each kudurru is unique; a good deal of variation exists in the number and choice of deities which appear.

Front:On this standing monument, the Mesopotamian pantheon is presented. The four great gods come first. Anu ("father of the gods" and god of heaven) and Enlil (god of wind, kingship and the earth), are shown as a multi-horned divine crown each on its own temple facade. Then Ea (god of water, magic and wisdom), is shown as a curved stick ending in a ram's head atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a horned goat. Above the first two deities, a female headdress in the shape of an omega sign, symbolizes Ninhursag ("mother of the gods" and goddess of fertility).

Reverse:The leading Babylonian god, Marduk, and his son Nabu, appear next. A triangular spade pointing up and a scribe's wedge-shaped stylus, respectively, each sits atop a temple facade pulled by the foreparts of a snake-dragon known as a Mushus. All five temple facades float on fresh, underground waters known as the Apsu or the Deep. Following these divinities, we find the mace, perhaps a local war god, the scepter with double lion heads of Ninurta (god of war), the arrow, a symbol of the star Sirius, and the two-pronged lightning bolt of Adad. This storm god is called by the similar name Haddad in the Levant. The running bird Papsukkal (minister of the gods, associated with the constellation Orion), is followed by the scorpion Ishara (goddess of oaths), the seated dog Gula (goddess of healing) and a bird on a perch, symbolizing both Shuqamuna and Shumalia (patron deities of the Kassite royal family).

Top:The top of the kudurru, representing the heavens, is surrounded and enclosed by the body of a large snake. Nirah (the snake god) encompasses four astral deities the crescent moon of Sin (the moon god), a multi-rayed circular sun disc of Shamash (the sun god), a star inside a disc for Ishtar (the goddess of love -especially sexuality- and war) and the lamp of Nusku (the god of fire and light). Ishtar, considered the most important Mesopotamian female deity, is associated with the morning and evening star, the planet Venus.

Unfinished Kudurru from the Reign of Melishipak, found in Sousa. Louvre, Paris

Melli-shipak Kudurru

Melišipak kudurru-Land grant to Hunnubat-Nannaya. Louvre, Paris

Kudurru of Melishihu. Louvre, Paris. Boundary markers for property are a very old concept. They are mentioned in the Bible: Proverbs 22:28 “Do not move an ancient boundary stone set up by your forefathers.”

Kudurru of Mellishuhu. Louvre.

Kudurru of Mellishuhu. Louvre.Moonhieroglyph on a kudurru. Indus Script: مر ḳamar A قمر ḳamar, s.m. (9th) The moon. Sing. and Pl. See سپوږمي or سپوګمي (Pashto) rebus: kamar 'artisan, smith' (Santali)

Tiger-head atop a temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS kola 'tiger' rebus: kol 'working in iron'

Rim-of-jar (upside down) atop temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS karṇika, kanka 'rim of jar' Rebus: karṇI 'supercaro, a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale'.'

A rod (signifying 'one') atop temple. Indus Script: kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'

Sun's rays hieroglyph on kudurrus. Indus Script: arka 'sun' rebus: arka, eraka 'copper'.

Star hieroglyph on kudurru. Indus Script: mēḍha मेढ 'polar star' (Marathi) rebus: मृदु mṛdu, mẽṛhẽt, meḍ 'iron' (Samskrtam, Santali. Mu.Ho.)Tree atop a temple on a kudurru. Indus Script:kole.l 'temple' rebus: kole.l 'smithy, forge' PLUS kuṭhi a sacred, divine tree, kuṭi 'temple'; kuṭhi 'smelter'

Tree and bull on a kudurru. Indus Script: kuṭhi a sacred, divine tree, kuṭi'temple'; kuṭhi 'smelter' PLUS ḍhaṅgaru, ḍhiṅgaru m. ʻlean emaciated beastʼ(Sindhi) Rebus: dhangar ‘blacksmith’ (Maithili)

kudurru stones of the Kassite Period (circa 1530-1155/1160 BCE) includes the following hieroglyphs:

.jpg)

Meli-Šipak kudurru, 1186–1172. pr. Kr. Goat-fish

Kudurru fragments. With mushhushshu.

Lion

Furrow

Scorpion-Archer

Hired-Man

Goat-Fish

Limestone kudurru reign of Marduk-nadin-ahhe: the boundary-stone consists of a block of black limestone, which has been shaped and rubbed down to take sculptures and inscriptions. Culture/period: Middle Babylonian Date: 11thC BC From: Babylon (Asia, Middle East, Iraq, South Iraq, Babylon) Materials: limestone Technique: carved British Museum number: 90841

Kudurru recording the bequest of land by Marduk-zâkir-šumi to Ibni-Ištar on behalf of the Eanna temple in Uruk [i 1] | |

| Reign | c. 855 – 819 BC |

|---|---|

| Predecessor | Nabû-apla-iddina |

| Successor | Marduk-balāssu-iqbi |

Limestone boundary-stone (kudurru) from the time of Nabu-mukin-apli![Image result for Kudurru]()

Unfinished kudurru (boundary marker) with a horned serpent

(symbol of Marduk) around pillar at bottom. The most proeminent

gods are featured as symbols. The space for the inscription was left

Accession No. Sb25 Louvre Museum.

| Kudurru "inachevé" Époque kassite, attribué au règne de Meli-Shipak (1186-1172 av. J.-C.) Découvert à Suse où il avait été emporté en butin de guerre au XIIe siècle avant J.-C. Calcaire Sous les anneaux du serpent qui s'enroule sur le sommet sont figurées les principales divinités du panthéon sous forme de symboles. Au-dessous, un cortège de dieux musiciens et d'animaux. Murs et tours crénelées encadrent l'emplacement réservé à une inscription qui n'a jamais été gravée. Un serpent cornu, emblème du dieu Marduk, entoure la base. | |||

| |||

“Kudurru or a boundary stone from Babylon dating back to 1099-1082 BCE. The Kudurru was found at the Temple of Esagila in Babylon. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD.

“Kudurru or a boundary stone from Babylon dating back to 1099-1082 BCE. The Kudurru was found at the Temple of Esagila in Babylon. The Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, MD.