-- Indus Script wealth-accounting, Sarasvati river basin archaeology of over 2000 archaeological sites (80% of the sites of Hindu civilization) & R̥gveda evidence for Sarasvati River -- resources for ancient Indian Economic history

This monograph presents 1) textual evidence from R̥gveda related to Sarasvati River and the people of the civilization who lived on Sarasvati-Sindhu river basins; and 2) results of decipherment of over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions as wealth-accounting ledgers of metalwork of Tin-Bronze Age Revolution.

![]()

![]()

Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE Louvre Museum.

khonda 'holcus sorghum' khonda 'young bull' rebus: kond 'kiln', kundar, 'turner' kundana 'fine gold' PLUS karba 'stalk of millet' (holcus sorghum) rebus: karba 'iron'. The proclamation is that the gold workers have started working with iron.

This monograph presents 1) textual evidence from R̥gveda related to Sarasvati River and the people of the civilization who lived on Sarasvati-Sindhu river basins; and 2) results of decipherment of over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions as wealth-accounting ledgers of metalwork of Tin-Bronze Age Revolution.

Detail of a victory parade, from the Ishtar temple, Mari, Syria. 2400 BCE Louvre Museum.

khonda 'holcus sorghum' khonda 'young bull' rebus: kond 'kiln', kundar, 'turner' kundana 'fine gold' PLUS karba 'stalk of millet' (holcus sorghum) rebus: karba 'iron'. The proclamation is that the gold workers have started working with iron.

Establishing Rakhigarhi as the capital of the civilization linking maritime riverine waterways of Ancient India

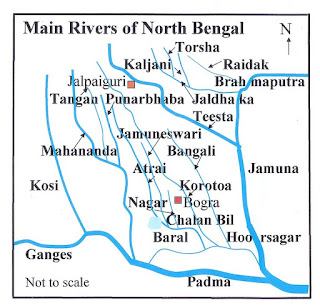

Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa provides a detailed account of the movement of people (Videgha Māthava, Gotama Rahugaṇa) from River Sarasvati to River Sadānīra. The location of this river is central to the history of Pre-Mauryan era Bhāratam Janam (RV 3.53.12). Sadānīra is Karatoya a tributary of Ganga and Brahmaputra. This evidence posits a hypothesis that tin (and iron) for the Tin-Bronze revolution was brought in through Rakhigarhi which linked the Yamuna-Ganga-Brahmaputra riverine waterway with the riverine Maritime waterway of River Sarasvati.

Map of Meluhha and Southwest Asia (inset Bahrain) (After Fig. 1 Eric Olijdam, 2008, A possible Central Asian origin for the seal-impressed jar from the Temple Tower' at Failaka), in:Eric Olijdam & RH Spoor, eds, Intercultural relations between South and Southwest Asia, Studiesin Commemoration of ECL During Caspers (1934-1996), BAR Intrnational Series 1826 (2008): 268-287).

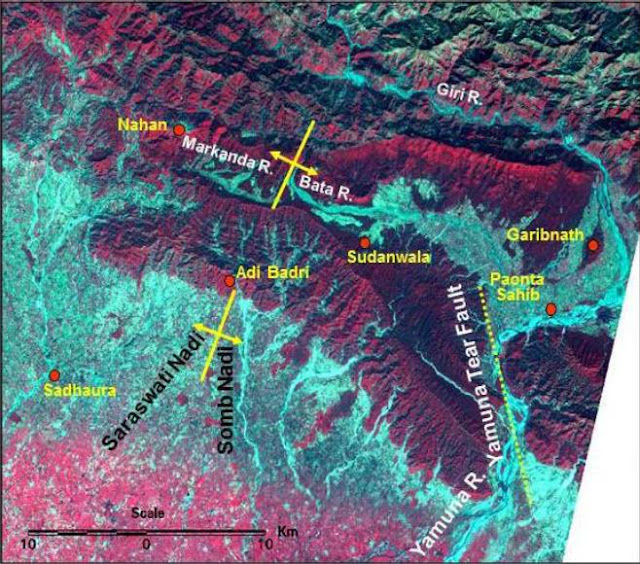

Water-divide (close to Rakhigarhi) caused by Aravalli mountain ranges jutting into Śimla, south of the Himalayas explains eastward flow of Yamuna and westward flow of Sutlej and Sarasvati Rivers

Tectonic events, after 3rd millennium BCE, resulted in eastward shift of Yamuna River (close to Rakhigarhi) and westward shift of 90-degrees and migration of Sutlej River (Ropar); both Yamuna and Sutlej were tributaries of Sarasvati River, during the mature period (3rd m. BCE) of the civilization evidenced by Indus Script inscriptions from archaeological sites on the Sarasvati River basin. Decipherment of Indus Script inscriptions discovered at Rakhigarhi is presented in

Rakhigarhi Indus script metalwork catalogues deciphered. Capital settlement of Sarasvati-Sindhu civilization (224 hectares). Kudos to Dr. Vasant Shinde http://tinyurl.com/zat4ty2I am thankful to Prof. Vasant Shivram Shinde, VC, Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Inst. (Deened-to-be University), Pune for the map showing Palae-Yamuna close to Rakhigarhi in relation to the Saravati River Basin (also called Ghaggar Basin).

The importance of this map has to be realised in reference to Rakhigarhi as the largest archaeological settlement of Sarasvati Civilization with an extent of nearly 500 hectares.

The size of Rakhigarhi settlement and its proximity to Palaeo-Yamuna and Sarasvati River Systems makes it not only the capital of the Ghaggar basin but the capital of all five regions of Sarasvati Civilization divided into 1. Ghaggar Basin (Rakhigarhi); 2. Western Punjab (Harappa); 3. Cholistan (Ganweriwala); 4. Balochistan (Mohenjo-daro); 5. Gujarat (Dholavira).

Palaeo-Yamuna flows eastwards while Chautang and Drishadvati (tributaries of Sarasvati River System) flow westwards. The directional shift of Palaeo-Yamuna eastwards is caused by the water-divide of the Aravalli ranges jutting into the Siwalik ranges, right upto Simla, constituting the water-divide.

Geomorphological studies have to be conducted to delineate the chronological sequences of eastward shift of Yamuna River after it emerges out of the Yamuna tear in the Siwalik ranges.

The prodimity of Palaeo-Yamuna to the cluster of sites of Rakhigarhi, Farmana, Girawad, Mitathal (dated ca. 7th millennium BCE) makes Rakhigarhi the node for linking Yamuna-Ganga-Brahmaputra River Basins with the Sarasvati River (Ghaggar) Basin) rendering the Sarasvati Civilization a Metals Age Civilization working not only with copper and zinc but also with tin and iron ores (magnetite, haematite, laterite ferrite ores). Karatoya River celebrated in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa has been identified by Amara in Amara kośa, as Sadānīrā River mentioned in R̥gveda. The contact areas of Sarasvati Civilization extend into Ancient Far East for tin resouces -- of the largest tin belt of the globe in the Himalayan river basins of Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween -- transported through riverine waterways and in maritime trade across the Indian Ocean.

![Image result for yamuna tear]()

A report on excavations at Farmana 2007-2008 by Vasant Shinde, Toshiki Osada, Akinori Uesugi, and Manmohan Kumar, Indus Project, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto, Japan, 2008

I am thankful to Prof. Vasant Shivram Shinde, VC, Deccan College Postgraduate and Research Inst. (Deened-to-be University), Pune for the map showing Palae-Yamuna close to Rakhigarhi in relation to the Saravati River Basin (also called Ghaggar Basin).

The importance of this map has to be realised in reference to Rakhigarhi as the largest archaeological settlement of Sarasvati Civilization with an extent of nearly 500 hectares.

The size of Rakhigarhi settlement and its proximity to Palaeo-Yamuna and Sarasvati River Systems makes it not only the capital of the Ghaggar basin but the capital of all five regions of Sarasvati Civilization divided into 1. Ghaggar Basin (Rakhigarhi); 2. Western Punjab (Harappa); 3. Cholistan (Ganweriwala); 4. Balochistan (Mohenjo-daro); 5. Gujarat (Dholavira).

Palaeo-Yamuna flows eastwards while Chautang and Drishadvati (tributaries of Sarasvati River System) flow westwards. The directional shift of Palaeo-Yamuna eastwards is caused by the water-divide of the Aravalli ranges jutting into the Siwalik ranges, right upto Simla, constituting the water-divide.

Geomorphological studies have to be conducted to delineate the chronological sequences of eastward shift of Yamuna River after it emerges out of the Yamuna tear in the Siwalik ranges.

The prodimity of Palaeo-Yamuna to the cluster of sites of Rakhigarhi, Farmana, Girawad, Mitathal (dated ca. 7th millennium BCE) makes Rakhigarhi the node for linking Yamuna-Ganga-Brahmaputra River Basins with the Sarasvati River (Ghaggar) Basin) rendering the Sarasvati Civilization a Metals Age Civilization working not only with copper and zinc but also with tin and iron ores (magnetite, haematite, laterite ferrite ores). Karatoya River celebrated in Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa has been identified by Amara in Amara kośa, as Sadānīrā River mentioned in R̥gveda. The contact areas of Sarasvati Civilization extend into Ancient Far East for tin resouces -- of the largest tin belt of the globe in the Himalayan river basins of Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween -- transported through riverine waterways and in maritime trade across the Indian Ocean.

A report on excavations at Farmana 2007-2008 by Vasant Shinde, Toshiki Osada, Akinori Uesugi, and Manmohan Kumar, Indus Project, Research Institute for Humanity and Nature, Kyoto, Japan, 2008

Palaeo-channels of Yamuna river intersecting Sarasvati River. (After Fig. 6 Distribution of Harappan sites in relation to palaeochannels in parts of Haryana plains (modified from Bhadra et al., 2009). Note the concentration of archaeological sites along the resistivity transects. (L. Khan, R. Sinha, 2019, Discovering ‘buried’ channels of the Palaeo-Yamuna river in NW India using geophysical evidence: implications for major drainage reorganization and linkage to the Harappan Civilization, in: Journal of Applied Geophysics 167 (2019) 128-139)

This study by L.Khan and R. Sinha (2019) points to a palaeo-channel of Sutlej River joining Ghaggar close to the Siwalik ranges. To the east of this palaeo-channel flow is a Palaeo-channels of Yamuna marked as Y1 and Y2 on the map. It is notable that these Yamuna Palaeo-channels Y1 and Y2 are to the west of the present-day channel of Yamuna river flowing into New Delhi. Rakhigarhi is shown as Site 1 on the maps. Thus, there are clear indications that Rakhigarhi was located on the right-bank of Yamuna river and the left-bank of River Sarasvati (called Ghaggar). It appears that the Palaeo-channels of Yamuna River joined Drishadvati (Sarasvati-Ghaggar River channel) north of Rakhigarhi, close to Siwalik ranges (Yamunanagar). The dates of these channels close to Rakhigarhi have to be further investigated to determine if Rakhigarhi could have been a riverine port linking the Ancient Maritime waterways of Yamuna and Sarasvati Rivers of ca. 4th-3rd millennium BCE

Sarasvati River, ca. 3000 BCE (After Fig. of Mature Harappan sites by Michel Danino) https://iitgn.academia.edu/

The map of Michel Danino shows a palaeo-channel of River Sutlej joining River Sarasvati west of Anupgarh (site 4MSR of Binjor, a R̥gveda site attested archaeologically with an octagonal pillar as described in the sacred texts). At thi site, the width of the palaeo-channel of River Sarasvati is over 10 kms. with forking channel of River Sarasvati flowing southwards towards Jaisalmer, as shown on the Landsat image.

The map of Michel Danino does not locate Shatrana and does not indicate the 90-degree massive westward deflection of River Sutlej which was flowing southwards as a tributary of River Sarasvati (joining at Shatrana and creating a 20 km. wide channel of River Sarasvati at the site)

NOTE: Virtually no archaeological sites on the Sutlej course (present-day) west of Ropar, but there is a series of sites south of Ropar proving the flow of Vedic River Sutlej into Vedic River Sarasvati to join the latter at Shatrana (width of paleochannel here is 20 kms.) Indus Script seals have also been discovered at Ropar. This esablishes that the westward 90-degree turn at Ropar of present-day Sutlej River AFTER the mature period of Sarasvati Civilization.

Courtesy: Maps of Sarasvati River and settlements by KS Valdiya. The settlements of Hulas and Alamgirpur are shown on the left bank of Yamuna river.

Based on the map of Michel Danino and the two maps of KS Valdiya, it is clear that more researches are needed to explain 1) how the a palaeo-channel of the Pirate River Yamuna was a tributary of the River Sarasvati joining west of Kalibangan and 2) how the two migratory palaeo-channels of River Sutlej joining River Sarasvati at Shatrana and west of Anupgarh, have to be chronologically attested.

One pointer to the chronology of eastward and westward migrations respecively of palaeo-channels of Yamuna and Sutlej is that Rakhigarhi and Kaliban have produced archaeological evidence of cylinder seals. This points to the reasonable inference that these sites had used River Sarasvati navigable channels for maritime trade with Ancient Near East (Mesopotamia) across the Rann of Kutch, Persian Gulf and Tigris-Euphrates rivers.

Definition of term 'hypertext': In this monograph, hypertext is defined as combination of sections of text and associated graphic material. Sections of text can be 'symbols' PLUS typographic ligatures or diacritical marks. Associated graphic material may be compositions of hieroglyphs, e.g. young bull PLUS horn to signify a horned young bull.

अहम् राष्ट्री संगमनी वसूनाम् I am the mover of nation's wealth: देवता आत्मा, ऋषिका वाक्आम्भृणी (RV 10.125) This soliloquy of R̥gveda is a metaphor for Sarasvati as a navigable waterway. Artisans and seafaring merchants traded the products documented in the wealth-accounting ledgers with people of settlements of neighbouring contact areas.

On the Sarasvati river basin which is a navigable waterway, and also on settlement signs of Dilmun, Makan of the Persian Gulf, Meluhha artisans produced the wealth of a nation.

This extraordinary economic activity of the Tin=Bronze revolution is documented in over 8000 Indus Script inscriptions.

Three categories of most frequently displayed hypertexts of Indus Script inscriptions are described below:

Hypertext Category 1: Most frequently displayed Indus Script hieroglyph (which is a hypertext) signifies pure gold, gold for ornaments

Unicorn read in Meluhha cyphertext as खोंड khōṇḍa singin 'young bull, horned'. In plain text, the rebus reading is: kundaṇa 'fine gold', singi 'gold for ornaments'

Component hieroglyphs highlighted on the composite animal

1. singi 'horned' rebus: singi 'village headman' singi 'gold for ornaments';

2. koḍiyum 'neck ring' rebus: koḍ 'workshop';

3. khara 'onager (face)' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'; kāruvu 'artisan' (Telugu)

1. singi 'horned' rebus: singi 'village headman' singi 'gold for ornaments';

2. koḍiyum 'neck ring' rebus: koḍ 'workshop';

3. khara 'onager (face)' rebus: khār 'blacksmith'; kāruvu 'artisan' (Telugu)

4. Body of the animal: खोंड khōṇḍa m A young bull, a bullcalf. (Marathi) rebus: kō̃da कोँद 'kiln, furnace for smelting'; kunda 'a treasure of Kubera' Rebus: Ta. kuntaṉam interspace for setting gems in a jewel; fine gold (< Te.). Ka. kundaṇa setting a precious stone in fine gold; fine gold; kundana fine gold.Tu. kundaṇa pure gold. Te. kundanamu fine gold used in very thin foils in setting precious stones; setting precious stones with fine gold. (DEDR 1725).5. Pannier: khōṇḍa 'sack, pannier' khōṇḍī 'pannier sack' खोंडी (Marathi) Rebus: kunda 'nidhi'; kō̃da कोँद 'kiln, furnace for smelting' This is a semantic determinative of the body of the animal.

Thus, the body of the young bull PLUS face/head of onager is read together: khara 'onager' rebus: खोंड khōṇḍa 'young bull' rebus: kō̃da कोँद 'kiln, furnace for smelting'PLUS khār खार् 'blacksmith'. The expression read together rebus is: kundakara, 'turner, lapidary'.

Composite hypertext, cyphertext of the composite animal: khōṇḍa khara singi 'young bull, onager, one-horn (horned) rebus plain text:

kōṇḍa kunda khār singi Rebus 1: 'कोंड [kōṇḍa] A circular hamlet; a division of a मौजा or village, composed generally of the huts of one caste'; Rebus 2: kō̃da कोँद 'kiln, furnace', fine-gold smith gold for ornaments'.

"This unicorn seal was also discovered during the late 1927-31 excavations at Mohenjo-daro. One theory holds that the bull actually has two horns, but that these have been stylized to one because of the complexity of depicting three dimensions. However the manufacturing and design process behind seals was so sophisticated that the depiction of three dimensions might not necessarily have been a problem." -- Omar Khan https://www.harappa.com/seal/11.html Slide 46 https://slideplayer.com/slide/15162906/

The device is a composition with component hieroglyphs. The four component hieroglyphs are: 1.lathe; 2. portable furnace; 3. dotted circles; 4. gimlet (of lathe)

Component 1. Lathe: kunda1 m. ʻ a turner's lathe ʼ lex. [Cf. *cunda -- 1] N. kũdnu ʻ to shape smoothly, smoothe, carve, hew ʼ, kũduwā ʻ smoothly shaped ʼ; A. kund ʻ lathe ʼ, kundiba ʻ to turn and smooth in a lathe ʼ, kundowā ʻ smoothed and rounded ʼ; B. kũd ʻ lathe ʼ, kũdā, kõdā ʻ to turn in a lathe ʼ; Or. kū˘nda ʻ lathe ʼ, kũdibā, kū̃d° ʻ to turn ʼ (→ Drav. Kur. kū̃d ʻ lathe ʼ); Bi.kund ʻ brassfounder's lathe ʼ; H. kunnā ʻ to shape on a lathe ʼ, kuniyā m. ʻ turner ʼ, kunwā m. (CDIAL 3295). kundakara m. ʻ turner ʼ W. [Cf. *cundakāra -- : kunda -- 1, kará -- 1] A. kundār, B. kũdār, °ri, Or. kundāru; H. kũderā m. ʻ one who works a lathe, one who scrapes ʼ, °rī f., kũdernā ʻ to scrape, plane, round on a lathe ʼ.(CDIAL 3297). Rebus: kunda 'nidhi'; kō̃da कोँद

'kiln, furnace for smelting' Ta. kuntaṉam interspace for setting gems in a jewel; fine gold (< Te.). Ka. kundaṇa setting a precious stone in fine gold; fine gold; kundana fine gold.Tu. kundaṇa pure gold. Te. kundanamu fine gold used in very thin foils in setting precious stones; setting precious stones with fine gold. (DEDR 1725).

Component 2. Portable furnace: kammatamu 'portable gold furnace' rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner coinage'.The bottom portion, the portable furnace is: కమటము (p. 246) kamaṭamu kamaṭamu. [Tel.] n. A portable furnace for melting the precious metals. అగసాలెవాని కుంపటి. "చ కమటము కట్లెసంచి

యొరగల్లును గత్తెర సుత్తె చీర్ణముల్ ధమనియుస్రావణంబు మొలత్రాసును బట్టెడ నీరుకారు సా నము పటుకారు మూస బలునాణె పరీక్షల మచ్చులాదిగా నమరగభద్రకారక సమాహ్వయు డొక్కరుడుండు నప్పురిన్" హంస. ii. కమ్మటము kammaṭamu Same as కమటము. కమ్మటీడు kammaṭīḍu. [Tel.] A man of the goldsmith caste. Rebus: Ta. kampaṭṭam coinage, coin. Ma. kammaṭṭam, kammiṭṭam coinage, mint. Ka. kammaṭa id.; kammaṭi a coiner. (DEDR 1236)

Component 3: Dotted circles on the bottom register, i.e. portable furnace:

Dotted circle is composed of dot PLUS circle.

Circle: Hieroglyph 'roundness': वृत्त [p= 1009,2] mfn. turned , set in motion (as a wheel) RV.; a circle; vr̥ttá ʻ turned ʼ RV., ʻ rounded ʼ ŚBr. 2. ʻ completed ʼ MaitrUp., ʻ passed, elapsed (of time) ʼ KauṣUp. 3. n. ʻ conduct, matter ʼ ŚBr., ʻ livelihood ʼ Hariv. [√vr̥t 1 ] 1. Pa. vaṭṭa -- ʻ round ʼ, n. ʻ circle ʼ; Pk. vaṭṭa -- , vatta -- , vitta -- , vutta -- ʻ round ʼ; L. (Ju.) vaṭ m. ʻ anything twisted ʼ; Si. vaṭa ʻ round ʼ, vaṭa -- ya ʻ circle, girth (esp. of trees) ʼ; Md. va'ʻ round ʼ GS 58; -- Paš.ar. waṭṭəwīˊk, waḍḍawik ʻ kidney ʼ ( -- wĭ̄k vr̥kká -- ) IIFL iii 3, 192?(CDIAL 12069) வட்டம்போர் vaṭṭam-pōr, n. < வட்டு +. Dice-play; சூதுபோர். (தொல். எழுத். 418, இளம்பூ.)வட்டச்சொச்சவியாபாரம் vaṭṭa-c-cocca-viyāpāram, n. < id. + சொச்சம் +. Money-changer's trade; நாணயமாற்று முதலிய தொழில். Pond. வட்டமணியம் vaṭṭa-maṇiyam, n. < வட் டம் +. The office of revenue collection in a division; வட்டத்து ஊர்களில் வரிவசூலிக்கும் வேலை. (R. T .) వట్ట (p. 1123) vaṭṭa vaṭṭa. [Tel.] n. The bar that turns the centre post of a sugar mill. చెరుకుగానుగ రోటినడిమిరోకలికివేయు అడ్డమాను. వట్టకాయలు or వట్టలు vaṭṭa-kāyalu. n. plu. The testicles. వృషణములు, బీజములు. వట్టలుకొట్టు to castrate. lit: to strike the (bullock's) stones, (which are crushed with a mallet, not cut out.) వట్ర (p. 1123) vaṭra or వట్రన vaṭra. [from Skt. వర్తులము.] n. Roundness. నర్తులము, గుండ్రన. వట్ర. వట్రని or వట్రముగానుండే adj. Round. గుండ్రని.

Thus, dot PLUS circle hieroglyphs together read in cyphertext dhā, dāya 'dot'

PLUS: vaṭṭa 'circle'. Together, the rebus reading to yield plain text is: धवड dhavaḍa m (Or धावड) A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावड dhāvaḍa m A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron. धावडी dhāvaḍī 'relating to the class धावड. Hence 2 Composed of or relating to iron. (Reference to 'iron' as a category signifier is a reference to metalwork involving smelter, smithy, forge and lathe-work).

Thus, the dotted circle hypertext signifies धावड dhāvaḍa 'smelter'.

Component 4.Gimlet: In the Soma Yaga tradition, the reading is: hieroglyph: भ्रम a whirling flame RV.; a potter's wheel (सांख्यकारिका); a spring , fountain , watercourse; a gimlet or auger (Monier-Williams) बरमा or म्हा baramā or mhā m ( H) A kind of auger, gimlet, or drill worked with a string. 2 The hole or eye of a rocket.(Marathi) Ta. purai tubular hollow, tube, pipe, windpipe. Tu. perevuni to be bored, perforated; perepini to bore, perforate; burma, burmu a gimlet; berpuri a borer (DEDR 4297) rebus (metathesis): भर्म 'gold'.

Thus, together, the standard device signifies भर्म bharma kammaṭa kunda 'gold mint treasure' (of) धावड dhāvaḍa 'smelter'.

Hypertext Category 3: Most frequently used Indus Script expression in hypertext signifies wealth-accounting ledger of blacksmith, supercargo

The most frequently used Indus Script hypertext expression in Indus Script corpora consists of three unique hieroglyph: 1. khār 'backbone'; 2. karṇaka, 'rim-of-jar' 3. kharaḍā, 'currycomb'.

This triplet of hieroglyphs in Indus Script hypertext signifies wealth-accounting ledger of blacksmith's metalwork products:

1. khār खार् 'blacksmith',

2. karaṇī, scribe/supercargo (a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale), [Note: kul-- karṇī m. ʻ village accountant ʼ(Marathi)]

3. (scribed in) karaḍā खरडें 'daybook, wealth-accounting ledger of khār खार् 'blacksmith' (Kashmiri)

Yadav, Nisha, 2013, Sensitivity of Indus Script to type of object, SCRIPTA, Vol. 5 (Sept. 2013), pp. 67-1

Thus, the Indus Script hypertext ![]() in the centre of the venn diagram the hypertext with three signs, hieroglyphs, Sign 176, Sign 342 and Sign 48 signifies rebus rendering of the Meluhha expression khār karaṇī karaḍā: 1. blacksmith, 2. supercargo (a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.), 3. wealth-accounting ledger.

in the centre of the venn diagram the hypertext with three signs, hieroglyphs, Sign 176, Sign 342 and Sign 48 signifies rebus rendering of the Meluhha expression khār karaṇī karaḍā: 1. blacksmith, 2. supercargo (a representative of the ship's owner on board a merchant ship, responsible for overseeing the cargo and its sale.), 3. wealth-accounting ledger.

I suggest that the hypertexts of Indus Script Cipher are written down documents of the traditions of Soma Yāga processing Soma in fire altars or yajña kuṇḍa-s. The following sections demonstrate that Soma is 1. आहनसं and 2. amśu.

The Vedic texts provide resources to identify Soma and its significance as wealth-yielding product in the lives of the people on the Sarasvati-Sindhu River Basins from ca. 8th millennium BCE (as attested by continuous settlements of Bhirrana, Kunal and Mehrgarh).

The monograph posits that Soma is 1. आहनसं 'iron,gold'; and 2. amśu cognate ancu (Tocharian) 'iron'. (RV 10.125 venerates Tvaṣṭā, artisans who produce wealth,working in guilds. RV 10.125 explains that आहनसं is भर्मन् bharman 'support, maintenance, nourishment'. This is signified as a lathe part of the standard device on Indus Script: hieroglyph: भ्रम a whirling flame RV.; a potter's wheel (सांख्यकारिका); a spring , fountain , watercourse; a gimlet or auger (Monier-Williams) rebus (metathesis): भर्म 'gold'.

Pragmatics of the expression in Devī Sūktam (RV 10.125): अहं सोममाहनसं

In this extraordinary prayer, ऋषिका वाक्आम्भृणी claims:

अहं रुद्रेभिर्वसुभिश्र्चराम्यहमादित्यैरुत विश्र्वदेवैः ।

अहं मित्रावरुणोभा बिभर्म्यहमिन्द्राग्नी अहमश्र्विनोभा ॥ १ ॥

भर्मन् n. support , maintenance , nourishment , care RV. (cf. अरिष्ट- , गर्भ- , जातू-भ्°); भर्म gold; a partic. coin.

भर्मन् n. support , maintenance , nourishment , care RV. (cf. अरिष्ट- , गर्भ- , जातू-भ्°); भर्म gold; a partic. coin.

In addiion to describing herself as Rudra,Vasu, she says: अहं सोममाहनसं

What does आहनसं mean? It signifies striking, beating. The pragmatics and semantics explain the Pashto expressions in the context of ironwork by a blacksmith: P آهن āhan, s.m. (9th) Iron. Sing. and Pl. آهن ګر āhan gar, s.m. (5th) A smith, a blacksmith. Pl. آهن ګران āhan-garān. آهن ربا āhan-rubā, s.f. (6th) The magnet or loadstone. (E.) Sing. and Pl.); (W.) Pl. آهن رباوي āhan-rubāwī. See اوسپنه . اوسپنه aos-panaʿh, s.f. (3rd) Iron. Also used as an adjective to qualify another noun, signifying, Iron-like, hard. Pl. يْ ey. اوسپنخړيَ aos-panḵẖaṟṟaey, s.m. (1st) The dross of iron left after melting. Pl. يِ ī. It is significant that two words/expressions P آهن āhan and اوسپنه aos-panaʿh, are explained semantically as 'Iron.'. thus, the explanation of the expression अहं सोममाहनसं may be explained as 'I am Soma, I am beaten, struck iron' (comparable to the work of a Pl. آهن ګر āhan gar blacksmith, smith who works with P آهن āhan, 'Iron'. Is Soma iron? Scholiast explains the expression in the context of the metaphor of 'the foe-destroying Soma' while Griffith translates the expression as 'highswelling- Soma' (RV 10.125.2). In RV 5.42.13, the word आहन् is explained by Wilson as: "giving form (to the rivers)", while Griffith translates it as "made for us (this All)."

RV X.10.6, X.10.8 What, wanton!, wanton (Griffith) wanton, destructress (Wilson) wanton = sexually unrestrained. It appears that these semantics may have to be reviewed in the contet of the Pashto expressions. It appears that the word आहन् simply means 'strike, beat' (as iron on an anvil in a smith or forge). This is comparable to the wealth produced by the smith, iron worker, آهن ګر āhan gar (Pashto). The Pashto expression is also cognate with अशन् m. (connected with √ अश्) ([only /अश्ना (instr.) and /अश्नस् , perhaps better derived from /अश्मन् q.v. , cf.Whitney's Gr. 425 e]) , stone , rock RV. x , 68 , 8; a stone for slinging , missile stone RV. ii , 30 , 4 and iv , 28 , 5. अशनि f. (rarely m. R. Pa1n2. Sch.) the thunderbolt , a flash of lightning RV. &c; the tip of a missile RV. x , 87 , 4; a hail-stone, Kaus3.;

m. pl. N. of a warrior tribe , (g. पर्श्व्-ादि , q.v.). This word is signified by a similar sounding word (homonym), the hieroglyph: श्येन m. a hawk , falcon , eagle , any bird of prey (esp. the eagle that brings down सोम to man) RV. &c. śyēná m. ʻ hawk, falcon, eagle ʼ RV. Pa. sēna -- , ˚aka -- m. ʻ hawk ʼ, Pk. sēṇa -- m.; WPah.bhad. śeṇ ʻ kite ʼ; A. xen ʻ falcon, hawk ʼ, Or. seṇā, H. sen, sẽ m., M. śen m., śenī f. (< MIA. *senna -- ); Si. sen ʻ falcon, eagle, kite ʼ(CDIAL 12674) aśáni f. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ RV., ˚nī -- f. ŚBr. [Cf. áśan -- m. ʻ sling -- stone ʼ RV.]Pa. asanī -- f. ʻ thunderbolt, lightning ʼ, asana -- n. ʻ stone ʼ; Pk. asaṇi -- m.f. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ; Ash. ašĩˊ ʻ hail ʼ, Wg. ašē˜ˊ, Pr. īšĩ, Bashg. "azhir", Dm. ašin, Paš. ášen, Shum. äˊšin, Gaw. išín, Bshk. ašun, Savi išin, Phal. ã̄šun, L. (Jukes) ahin, awāṇ. &circmacrepsilon; (both with n, not ṇ), P. āhiṇ, f., āhaṇ, aihaṇm.f., WPah. bhad. ã̄ṇ, bhal. ´tildemacrepsilon; f., N. asino, pl. ˚nā; Si. sena, heṇa ʻ thunderbolt ʼ Geiger GS 34, but the expected form would be *ā̤n; -- Sh. aĩyĕˊr f. ʻ hail ʼ (X ?). -- For ʻ stone ʼ > ʻ hailstone ʼ cf. upala -- and A. xil s.v. śilāˊ -- .Addenda: aśáni -- : Sh. aĩyĕˊr (Lor. aĩyār → Bur. *lh ye r ʻ hail ʼ BurLg iii 17) poss. < *aśari -- from heteroclite n/r stem (cf. áśman -- : aśmará -- ʻ made of stone ʼ).(CDIAL 910) vajrāśani m. ʻ Indra's thunderbolt ʼ R. [vájra -- , aśáni -- ] Aw. bajāsani m. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ prob. ← Sk.(CDIAL 11207) These concordances are suggested because vajrāśani, aśán,

āśan > आहन् This yields the expression آهن ګر āhan gar, (lit.) 'thunderbolt (weapon) maker smith'. ahan-gār अहन्-गार् (= आहन् interj. of respect (Gr.Gr. 101) and adv. of assent, employed in the following compounds:--āhanō आहनो । आमिति adv. yes, used when addressing a male of equal or lower rank; it is an expression of doubtful assent. āhanū आहनू । आमि/?/ adv. yes, addressed to a junior male of rank equal to the speaker.(Kashmiri) The -gar, gār suffix in the expressions is cognate khār 1 खार् । लोहकारः m. (sg. abl. khāra 1 खार ; the pl. dat. of this word is khāran 1 खारन् , which is to be distinguished from khāran 2, q.v., s.v.), a blacksmith, an iron worker (cf. bandūka-khār, p. 111b, l. 46; K.Pr. 46; H. xi, 17); a farrier (El.).(Kashmiri)

Thus, when ऋषिका वाक्आम्भृणी claims to be soma, अहं सोममाहनसं, the expression should be pragmatically, semantically interpreted as struck or beaten Soma comparable to struck or beaten iron wealth for sustenance, nourishment (bharman) with a pun on the word bharma 'gold'.भ्रम a whirling flame RV.; a potter's wheel (सांख्यकारिका); a spring , fountain , watercourse; a gimlet or auger (Monier-Williams)

It is remarkable that a synonym of Soma, amśu is cognate ancu ' iron' (Tocharian)

That Soma is amśu is cognate ancu ' iron' (Tocharian); आहनसं 'iron' is consistent with the arguments presented in

What does आहनसं mean? It signifies striking, beating. The pragmatics and semantics explain the Pashto expressions in the context of ironwork by a blacksmith: P

RV X.10.6, X.10.8 What, wanton!, wanton (Griffith) wanton, destructress (Wilson) wanton = sexually unrestrained. It appears that these semantics may have to be reviewed in the contet of the Pashto expressions. It appears that the word आहन् simply means 'strike, beat' (as iron on an anvil in a smith or forge). This is comparable to the wealth produced by the smith, iron worker,

m. pl. N. of a warrior tribe , (g. पर्श्व्-ादि , q.v.). This word is signified by a similar sounding word (homonym), the hieroglyph: श्येन m. a hawk , falcon , eagle , any bird of prey (esp. the eagle that brings down सोम to man) RV. &c. śyēná m. ʻ hawk, falcon, eagle ʼ RV. Pa. sēna -- , ˚aka -- m. ʻ hawk ʼ, Pk. sēṇa -- m.; WPah.bhad. śeṇ ʻ kite ʼ; A. xen ʻ falcon, hawk ʼ, Or. seṇā, H. sen, sẽ m., M. śen m., śenī f. (< MIA. *senna -- ); Si. sen ʻ falcon, eagle, kite ʼ(CDIAL 12674) aśáni f. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ RV., ˚nī -- f. ŚBr. [Cf. áśan -- m. ʻ sling -- stone ʼ RV.]Pa. asanī -- f. ʻ thunderbolt, lightning ʼ, asana -- n. ʻ stone ʼ; Pk. asaṇi -- m.f. ʻ thunderbolt ʼ; Ash. ašĩˊ ʻ hail ʼ, Wg. ašē˜ˊ, Pr. īšĩ, Bashg. "azhir", Dm. ašin, Paš. ášen, Shum. äˊšin, Gaw. išín, Bshk. ašun, Savi išin, Phal. ã̄šun, L. (Jukes) ahin, awāṇ. &circmacrepsilon; (both with n, not ṇ), P. āhiṇ, f., āhaṇ, aihaṇm.f., WPah. bhad. ã̄ṇ, bhal. ´tildemacrepsilon; f., N. asino, pl. ˚nā; Si. sena, heṇa ʻ thunderbolt ʼ Geiger GS 34, but the expected form would be *ā̤n; -- Sh. aĩyĕˊr f. ʻ hail ʼ (X ?). -- For ʻ stone ʼ > ʻ hailstone ʼ cf.

āśan > आहन् This yields the expression

Thus, when ऋषिका वाक्आम्भृणी claims to be soma, अहं सोममाहनसं, the expression should be pragmatically, semantically interpreted as struck or beaten Soma comparable to struck or beaten iron wealth for sustenance, nourishment (bharman) with a pun on the word bharma 'gold'.भ्रम a whirling flame RV.; a potter's wheel (सांख्यकारिका); a spring , fountain , watercourse; a gimlet or auger (Monier-Williams)

It is remarkable that a synonym of Soma, amśu is cognate ancu ' iron' (Tocharian)

That Soma is amśu is cognate ancu ' iron' (Tocharian); आहनसं 'iron' is consistent with the arguments presented in

Soma is NOT a drink, it is a sacred metaphor

Soma is NOT a drink. Soma is EATEN by devā. That Soma is NOT a drink is emphatically stated in Chandogya Upanishad: eṣa somo rājā tad devānām annam tam devā bhakṣayanti:"That soma is king; this is the devas' food. The devas eat it." [Chāndogya.Upaniṣad (Ch.Up.]

Soma is NOT a drink. Soma is EATEN by devā. That Soma is NOT a drink is emphatically stated in Chandogya Upanishad: eṣa somo rājā tad devānām annam tam devā bhakṣayanti:"That soma is king; this is the devas' food. The devas eat it." [Chāndogya.Upaniṣad (Ch.Up.]

One thinks, when they have brayed the plant, that he hath drunk the Somas' juice; Of him whom Brahmans truly know as Soma no one ever tastes." (RV 10.85.3) Trans 2: He who has drunk thinks that the herb which men crush is the Soma; (but) that which the Bra_hman.as know to be Soma,, of that no one partakes. {i.e., no one partakes of it unless he has sacrificed; if the Soma be taken as the moon, 'no one' will mean 'no one but the gods'].

Soma is a sacred metaphor.

आहन् āhan आहन् 2 P. 1 To strike, hit, beat; आहत āhata आहत p. p. 1 Struck, beaten (as a drum &c.) आहत्य āhatya आहत्य ind. Having struck or beaten; striking, hitting. -वचनम्, -वादः An explicit or energetic explanation.आहननम् āhananam आहननम् 1 Striking at, beating. -2 A stick. (for beating a drum). Av.2.133.1.आहननीय āhananīya आहननीय a. Making oneself known by beating a drum. आहनस् āhanas आहनस् a. [आ-हन्-असुन्] 1 To be beaten or pressed out (as Soma). -2 Unchaste, wanton, profligate; य आहना दुहितुर्वक्षणासु Rv.5.42.13.

सोम m. (fr. √3. सु) juice , extract , (esp.) the juice of the सोम plant , (also) the सोम plant itself (said to be the climbing plant Sarcostema Viminalis or

Asclepias Acida , the stalks [अंशु] of which were pressed between stones [अद्रि] by the priests , then sprinkled with water , and purified in a strainer [पवित्र] ; whence the acid juice trinkled into jars [कलश] or larger vessels [द्रोण] ; after which it was mixed with clarified butter , flour &c , made to ferment , and then offered in libations to the gods [in this respect corresponding with the ritual of the Iranian Avesta] or was drunk by the Brahmans , by both of whom its exhilarating effect was supposed to be prized ; it was collected by moonlight on certain mountains [in RV. x , 34 , 1, the mountain मूज-वत् is mentioned] ; it is sometimes described as having been brought from the sky by a falcon [श्येन] and guarded by the गन्धर्वs ; it is personified as one of the most important of Vedic gods , to whose praise all the 114 hymns of the 9th book of the RV. besides 6 in other books and the whole SV. are dedicated ; in post-Vedic mythology and even in a few of the latest hymns of the RV. [although not in the whole of the 9th book] as well as sometimes in the AV. and in the Br. , सोम is identified with the moon [as the receptacle of the other beverage of the gods called अमृत , or as the lord of plants cf. इन्दु , ओषधि-पति] and with the god of the moon , as well as with विष्णु , शिव , यम , and कुबेर ; he is called राजन् , and appears among the 8 वसुs and the 8 लोक-पालs [ Mn. v , 96] , and is the reputed author of RV. x , 124 , 1 , 5-9 (Monier-Williams)

सोम m. (fr. √3. सु) juice , extract , (esp.) the juice of the सोम plant , (also) the सोम plant itself (said to be the climbing plant Sarcostema Viminalis or

Asclepias Acida , the stalks [अंशु] of which were pressed between stones [अद्रि] by the priests , then sprinkled with water , and purified in a strainer [पवित्र] ; whence the acid juice trinkled into jars [कलश] or larger vessels [द्रोण] ; after which it was mixed with clarified butter , flour &c , made to ferment , and then offered in libations to the gods [in this respect corresponding with the ritual of the Iranian Avesta] or was drunk by the Brahmans , by both of whom its exhilarating effect was supposed to be prized ; it was collected by moonlight on certain mountains [in RV. x , 34 , 1, the mountain मूज-वत् is mentioned] ; it is sometimes described as having been brought from the sky by a falcon [श्येन] and guarded by the गन्धर्वs ; it is personified as one of the most important of Vedic gods , to whose praise all the 114 hymns of the 9th book of the RV. besides 6 in other books and the whole SV. are dedicated ; in post-Vedic mythology and even in a few of the latest hymns of the RV. [although not in the whole of the 9th book] as well as sometimes in the AV. and in the Br. , सोम is identified with the moon [as the receptacle of the other beverage of the gods called अमृत , or as the lord of plants cf. इन्दु , ओषधि-पति] and with the god of the moon , as well as with विष्णु , शिव , यम , and कुबेर ; he is called राजन् , and appears among the 8 वसुs and the 8 लोक-पालs [ Mn. v , 96] , and is the reputed author of RV. x , 124 , 1 , 5-9 (Monier-Williams)

Binjor. Sarasvati River basinBinjor Fire-altar with octagonal pillar

The structure of the octagonal yupa signifying Vajapeya Soma Yāga includes an octagonal चिालाः caṣāla signified by the hour-glass-shaped Vajra

Commemorative stone yupa, Isapur – from Vogel, 1910-11, plate 23; drawing based on Vedic texts – from Madeleine Biardeau, 1988, 108, fig. 1; cf. 1989, fig. 2); C. Miniature wooden yupa and caSAla from Vaidika Samsodana Mandala Museum of Vedic sacrificial utensils – from Dharmadhikari 1989, 70) (After Fig. 5 in Alf Hiltebeitel, 1988, The Cult of Draupadi, Vol. 2, Univ. of Chicago Press, p.22)

Isapur Yupa inscription (102 CE, dated in year 24 in Kushana king Vasishka's reign) indicates performance of a sattra (yajña) of dvadasarAtra, 'twelve nights'. (Vogel, JP, The sacrificial posts of Isapur, Annual Report of the Archaeological Survey of India, 1910- 11: 40-8).The Isapur yupa is comparable to the ring and vajra atop

The monograph is presented in the following Sections:

Section A. Ancient Economic History of Hindu Rāṣṭram on Sarasvati-Sindhu River Basins

Section B. Indicators of Maritime trade by seafaring Meluhha merchants

-- Copper from Khetri mines, tin from the Tin Belt of the globe, Mekong delta

-- Source of tin from the Tin belt of the globe, the Himalayan river Mekong delta

Section C. Hypothesis of an eastern source for tin; epic tale of Enmerkar and Lord of Aratta

Section D. Rakhigarhi on the Ancient Maritime Tin Route through linked navigable Himalayan waterways from Ancient Far East to Ancient Near East

Section E. Indus Script hieroglyphs on Karen Bronze Drum of Ancient Far East

Section F. Advances in metallurgy during the Tin-Bronze Revolution from 5th m BCE

Section G. Indus Script decipherment

-- Shalamaneser III Black Obelisk is a Rosetta Stone for Indus Script, displays animals (as tributes); these animals are documented as Meluhha wealth-categories on Indus Script inscriptions

-- Evidence of Meluhha Indus Script animals on Shalamaneser III Black Obelisk (858-824 BCE) and displayed by Assyrian King Ashur-bel-kala (1074-1056 BCE)

Section H. Ivory tags with Egyptian hieroglyphs have been found in Abydos compare with miniature metalwork wealth-accounting tablets of Harappa

Section I. Domestication of farming, cotton and silk, 7th, 6th m BCE

Section J. Makkan and meluhha in early Mesopotamian sources --IJ Gelb

Section K. Literary evidence about Sarasvati river in the Veda, Epics and ancient texts

Over 1500 monographs on decipherment of Indus Script Inscriptions have been posted at https://independent.academia.edu/SriniKalyanaraman

Indian Lexicon with over 8000 semantic clusters of Meluhha words and expressions, gleaned from over 25 languages of Ancient India, is posted at https://www.academia.edu/37229973/Indian_Lexicon_--Comparative_dictionary_of_over_8000_semantic_clusters_in_25_ancient_Bharatiya_languages

Indian Lexicon with over 8000 semantic clusters of Meluhha words and expressions, gleaned from over 25 languages of Ancient India, is posted at https://www.academia.edu/37229973/Indian_Lexicon_--Comparative_dictionary_of_over_8000_semantic_clusters_in_25_ancient_Bharatiya_languages

-- India generated 60% of World GDP in 1 CE

-- Hindu Rāṣṭram on Sarasvati-Sindhu River Basins

-- water management in Sarasvati-Sindhu river basins

Gabar band on River Hab; Dholavira water-reservoir 73.4m long, 29.3m wide, and 10m deep (one of 16 reservoirs)

-- domestication of cotton (5th m BCE), silk (3rd m BCE), rice, cereals (7th m BCE), wood products

-- contribution of metalworkers (gold, copper, tin, zinc, iron), lapidaries' work with gems and jewels, alloying & cire perdue casting metallurgical technologies, shared wealth of śreṇi guilds of artisans, and trade by seafaring Meluhha merchants

Section A. Ancient Economic History of Hindu Rāṣṭram on Sarasvati-Sindhu River Basins

Ancient India was the Super Power from 8th millennium BCE, contributing upto 60% of Global GDP till 1 CE, and upto 27 % of Global GDP in 1700 CE. See the bar chart of Angus Maddison's presentation on Economic History of the World.

Section A. Ancient Economic History of Hindu Rāṣṭram on Sarasvati-Sindhu River Basins

Ancient India was the Super Power from 8th millennium BCE, contributing upto 60% of Global GDP till 1 CE, and upto 27 % of Global GDP in 1700 CE. See the bar chart of Angus Maddison's presentation on Economic History of the World.

Multi-disciplinary knowledge systems on Ancient Indian History posit this economic reality of the civilizational glory of Ancient India in 1 Common Era.

Indus Script evidence elucidates on how ancient India became a Super Power contributing significantly to the Tin-Bronze Revolution contributing to increase in global GDP from 5th millennium BCE.

Over 8000 inscriptions of the Indus Script are wealth-accounting ledgers of metal-work and lapidary-work involving gems and jewels.

Multi-disciplinary knowledge systems on Ancient Indian History posit this economic reality of the civilizational glory of Ancient India in 1 Common Era.

Indus Script evidence elucidates on how ancient India became a Super Power contributing significantly to the Tin-Bronze Revolution contributing to increase in global GDP from 5th millennium BCE.

Over 8000 inscriptions of the Indus Script are wealth-accounting ledgers of metal-work and lapidary-work involving gems and jewels.

Harappa Workers' Circular Platforms (Did the artisans work with indigo vats to colour textiles?)

Chanhudaro, Sheffield of Ancient India.

Discovered in chalcolithic levels of Mehergarh Metallurgical technology,

cire perdue bronze castings 5th m. BCE.

Gold fillets, ornaments of gold, silver,copper, bronze,ivory or shells, carnelian, agate perforated beads of Sarasvati-Sindhu Civilization.

Section B. Indicators of Maritime trade by seafaring Meluhha merchants

Copper from Khetri mines, tin from the Tin Belt of the globe, Mekong delta

Positing an Ancient Maritime Tin Route from Ancient Far East to Ancient Near East, based on Archaeometallurgical provenance study of tin-bronze artifacts of Mesopotamia https://tinyurl.com/yyeyfkxu

Abstract from Iranica Antiqua, 2009:

Copper from Gujarat used in Mesopotmia, 3rd millennium BCE, evidenced by lead isotope analyses of tin-bronze objects; report by Begemann F. et al.

2. Author(s): BEGEMANN, F. , SCHMITT-STRECKER, S.

Journal: Iranica Antiqua

Volume: 44 Date: 2009

Pages: 1-45

DOI: 10.2143/IA.44.0.2034374

Journal: Iranica Antiqua

Volume: 44 Date: 2009

Pages: 1-45

DOI: 10.2143/IA.44.0.2034374

A lead isotope study »On the Early copper of Mesopotamia« reports on copper-base artefacts ranging in age from the 4th millennium BC (Uruk period) to the Akkadian at the end of the 3rd millennium BC. Arguments are presented that, in the (tin)bronzes, the lead associated with the tin used for alloying did not contribute to the total in any detectable way. Hence, the lead isotopy traces the copper and cannot address the problem of the provenance of tin. The data suggest as possible source region of the copper a variety of ore occurrences in Anatolia, Iran, Oman, Palestine and, rather unexpectedly (by us), from India. During the earliest period the isotopic signature of ores from Central and North Anatolia is dominant; during the next millennium this region loses its importance and is hardly present any more at all. Instead, southeast Anatolia, central Iran, Oman, Feinan-Timna in the rift valley between Dead Sea and Red Sea, and sources in the Caucasus are now potential suppliers of the copper. Generally, an unambiguous assignment of an artefact to any of the ores is not possible because the isotopic fingerprints of ore occurrences are not unique. In our suite of samples bronze objects become important during ED III (middle of the 3rd millennium BC) but they never make up more than 50 % of the total. They are distinguished in their lead isotopy by very high 206Pb-normalized abundance ratios. As source of such copper we suggest Gujarat/Southern Rajasthan which, on general grounds, has been proposed before to have been the most important supplier of copper in Ancient India. We propose this Indian copper to have been arsenic-poor and to be the urudu-luh-ha variety which is one of the two sorts of purified copper mentioned in contemporaneous written texts from Mesopotamia to have been in circulation there concurrently.

This archaeometallurgical provenance study links Khetri copper mines --through Dholavira/Lothal and Persian Gulf -- with Mesopotamia. It is possible that tin from Ancient Far East (the tin-belt of the globe) was also routed through Meluhha merchants.

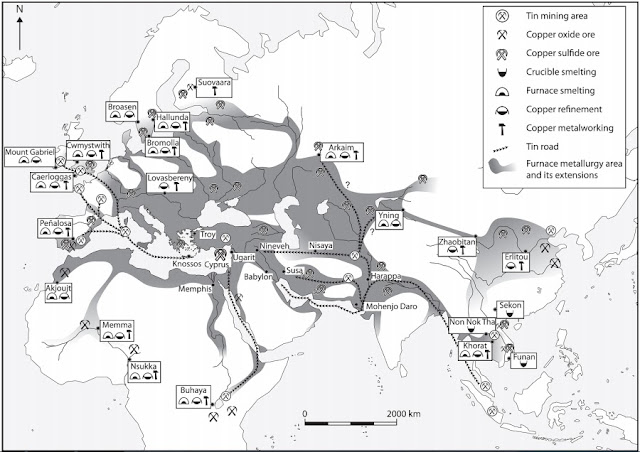

Source of tin from the Tin belt of the globe, the Himalayan river Mekong delta

Hebrew Bible, Ezekiel 27:12, says, "Tarshish was your (Tyre) merchant because of your many luxury goods. They gave you silver, iron, tin, and lead for your goods." "The ships of Tarshish were carriers of your (Tyre's) merchandise. You were filled and very glorious in the midst of the seas. (Ezekiel 27:25)"The mountains of Wales, just north of Cornwall have been a source of all the minerals and metals listed above in Ezekiel 27:12.

It is likely that Tarshish was NOT the source of tin-bronzes of Ancient Near East of 4th and 3rd millennia BCE because one cuneiform text specifically refers to Meluhha as the source of tin. The oldest direct evidence of pure tin is a tin ingot from the 1300 BCE Uluburun

shipwreck off the coast of Turkey which carried over 300 copper bars weighing 10 tons, and approximately 40 tin bars weighing 1 ton Another evidence comes from the three tin ingots of ca. 1200 BCE from Haifa shipwreck.

Mesopotamian EDI cuneiform texts from Ur distinguish between copper (urudu/eru) and tin=bronze (zabar/siparru). ED II/III texts from Fara (Limet 1960) mention metallic tin (AN.NA/annakum). Texts from Palace G at Ebla refer to the mixing of various ratios of 'washed' copper (a-gar(-gar)/abaru) and tin to produce bronze (Waetzoldt and Bachmann 1984; Archi 1993). The recipes are also found in the late 19th century BCE texs from Mari (Muhly 1985:282). Typical copper-tin ratios are from 6:1 to 10:1.

Two collections of cuneiform texts from Kultepe and from Mari dating to 19th and early 18th centuries BCE have references to tin trade. "These texts document a trade in which tin was moving exclusively from east to west. Arriving in Mesopotamia from the east, metallic tin was transhipped up the Euphrates to Mari, or overland to Assur. From Assur the tin (in addition to Babylonian textiles) was transported via donkey caravan to various Assyrian trading colonies such as Kanesh/Kultepe in Anatolia, where it was traded for silver and gold (Larsen 1976, 1987). From Mari, the tin was traded further west to sides in Syria and Palestine (Dossin 1970; Malamat 1971), and perhaps as far as Crete (Malamat 1971:38; Muhly 1985:282)." (p.179)

Section C. Hypothesis of an eastern source for tin; epic tale of Enmerkar and Lord of Aratta

"One text from the reign of Gudea of Lagash mentions that, in addition to lapis lazuli and carnelian, tin was also traded to Mesopotamia from the land of Meluhha. The relevant passage (Cylinder B, column XIV, lines 10-13) states that 'Gudea, the Governor of Lagash, bestowed as gifts copper, tin, blocks of lapis lazuli, [a precious metal] and bright carnelian from Meluhha. (Wilson 1996; see also Muhly 1973: 306-307). This is the only specific cuneiform reference to the trade of tin from Meluhha...'A pre-Sargonic text from Lagash published by B. Foster (1997) and described as 'a Sumerian merchant's account of the Dilmun trade' mentions obtaining from Dilmun 27.5 minas (ca. 14 kg) of an-na zabar. This phrase can be literally translated as 'tin bronze', and Foster suggested the possible reading 'tin (in/for?) bronze'...The fact that the isotopic characteristics of the Aegean tin-bronzes are so similar to those from the Gulf analyzed in this study adds further weight to the hypothesis of an eastern source for these early alloys...The possibility of tin coming from these eastern sources is supported by the occurrence of many tin deposits in modern-day Afghanistan, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, although evidence for tin extraction is currently limited to the central Asian sites of Karnab and Mushiston, and goes only as far back as the second millennium BCE...Yener has argued cogently against a 'on-source-for-all' model of the third millennium tin trade, and does not regard the proposed tin mining and processing in the Taurus Mountains as inconsistent with the importation of large amounts of tin into Anatolia. Taurus in production is thought to have co-existed with large-scale exchange of foreign metal in the third millennium, before the eventual 'devastation' of Anatolian tin mining operations by the availability of 'purer, already packaged, readily-available tin' from the Old Assyrian trade (Yener 2000:75)...IN particular, for regions such as Baluchistan, the Indus Valley, and the Gulf, which show significant third millennium tin-bronze use, the exclusive use of tin or tin-bronze from Afghanistan and central Asia seems highly likely. Textual sources are scarce, but highlight the trade through the Gulf linking Mesopotamia with Meluhha, Magan and Dilmun as the most common source of tin in the latter third millennium BCE, after an earlier overland Iranian tin-lapis-carnelian trade hinted at by the epic tale of Enmerkar and the Lord of Aratta. " (pp.180-181)

Muhly, JD, 1973, Copper and tin. Transactions, The Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 43: 155-535.

Muhly, J.D. (1985), "Sources of tin and the beginnings of bronze metallurgy", Journal of American Archaeology, 89 (2), pp. 275–291

“Almost all the third millennium BCE cuneiform texts from southern Mesopotamia which mention specific toponyms as copper sources speak of copper from either Magan or Dilmun (T. F. Potts 1994:Table 4.1). Meluhha, the third polity of the Lower Sea, is mentioned only rarely as a copper supplier, and then for amounts of only a few kilograms (Leemans 1960:161). The common association of Meluhha with the supply of carnelian, lapis lazuli, gold, precious woods, and especially ivory, suggests that the toponym is to be

related to the region between the Makran coast and Gujarat, encompassing sites of the Indus civilization (Heimpel 1993).” (p.15)

“Mesopotamia, as has often been stated, lacked resources. Its lack of metal ores required this world, at times, independent city-states and, at other times, empire, to look to distant lands in order to procure its metal/ores. Mesopotamian technology, however, was not a form of administrative or scribal concern. When it came to metal technology written texts offer limited information and are all but silent on the training, organization, and recruitment of metal smiths. Similarly, the texts are vague, or more typically silent, as to the geographical provenience from whence they obtained their metal/ore, its quantity, quality, price, or techniques of fabrication. It is left to the archaeologist and the recovered metal artifacts, workshops, associated tools, and mines, to address these questions...Decades ago VG Childe placed metallurgy on the top of his list of important crafts. He maintained that the development of early civilizations was a consequence of the invention of metallurgy (Childe 1930). Bronze-working, he believed, encouraged the manufacture of tools, which in turn led to more productive agriculture, and the growth of cities. Seventy-five years ago, Childe (1930:39) could point out that ‘Other documents from Mesopotamia, also written in the wedge-like characters called cuneiform, refer to the importation of copper from the mountainous region east of the Tigris and of metal and stones from Magan (probably Oman on the Persian Gulf)”…(Lloyd Weeks) introduces us to a new corpus of metal artifacts from the United Arab Emirates. Surprisingly, a significant percentage of these metals, recovered from the site of Tell Abraq, are tin-bronzes…his volume offers an up-to-date review of the enduring ‘tin-problem’ within the context of the greater Near East. Again, Childe (1928: 157) confronted the problem: ‘The Sumerians drew supplies of copper from Oman, from the Iranian Plateau, and even from Anatolia, but the source of their tin remains unknown’…(Lloyd Weeks) states ‘…the absolute source of the metal (tin-bronze) is likely to have been far to the north and east of Afghanistan or central Asia’. The central Asian source has been given reality by the recent discovery in Uzbekistan and Tadzhikistan of Bronze Age settlements and mines involved in tin production (Parzinger and Boroffka 2003).” (From CC Lamberg-Karlovsky’s Foreword in: Weeks, Lloyd R., 2003, Early metallurgy of the Persian Gulf –Technology, trade and the bronze age world, Brill Academic Publishers, Boston, pp. vii-viii).

See full text: https://drive.google.com/file/

Map showing the location of known tin deposits exploited during ancient times

করতোয়া নদী is Sadānīra of Brahmaputra river mentioned in ancient texts, suggesting Brahmaputra as a navigable waterway linking with Sarasvati River across Rakhigarhi

Amara Kośa asserts Sadānīra to be synonym of Karatoya River. See: सदानीरा स्त्री सदा नीरं पेयमस्याः । करतोयानद्याम् अमरः । “अथादौ कर्कटे देवी त्र्यहं गङ्गा रजस्वला । सर्वा रक्तवहा नद्यः करतोयाम्बुवाहिनी” स्मृत्युक्तेः

- तन्नदीजलस्य सदापेयत्वात् तस्यास्तथात्वम् । Source: https://sa.wikisource.org/wiki/वाचस्पत्यम्

Karatoya Mahatmya refers to the sacredness of this river. Rivers Kosi and Mahananda joined the Karatoya and "formed a sort of ethnic boundary between people living south of it and the Kochs and Kiratas living north of the river." (Majumdar, Dr. R.C., History of Ancient Bengal, First published 1971, Reprint 2005, p. 4, Tulshi Prakashani, Kolkata.)

Śatapatha Brāhmaṇa provides a detailed account of the movement of people (Videgha Māthava, Gotama Rahugaṇa) from River Sarasvati to River Sadānīra. The location of this river is central to the history of Pre-Mauryan era Bhāratam Janam (RV 3.53.12). The region of these people has been identified in this monograph and relates to the ironwork of the Bronze Age Sarasvati Civilization. It is possible that both Brahmautra and Ganga river systems were waterways which provided for maritime transport of tin ore from the Himalayan riverbasins (Irrawaddy, Salween, Mekong) which contain the richest and largest tin belt of the globe (as the rivers ground down graniterocks to create the cassiterite -- tin ore -- deposit accumulations as placer deposits). Sources of tin were critical to unleash the Tin-Bronze Industrial Revolution of ca. 4th millennium BCE.

Importance of Rakhigarhi on the water-divide linking Ganga-Yamuna-Brahmaputra waterways with Sarasvati River system

The addition of tin to copper to create bronze alloy was a revolution. The tin-bronze replaed arsenical bronze (copper + arsenic) which was a natural source and in short supply.

This Tin-Bronze Revolution is matched by the revolution of a writing system called Indus Script to document ancient India's contributions to metalwork.

This Tin-Bronze Revolution is matched by the revolution of a writing system called Indus Script to document ancient India's contributions to metalwork.

Section D. Rakhigarhi on the Ancient Maritime Tin Route through linked navigable Himalayan waterways from Ancient Far East to Ancient Near East

I suggest proclamation and constitution of two multi-disciplinary project teams involving archaeology, history, language studies, geochemistry, and geology for researches on: 1. Largest tin belt of the globe in AFE and role of seafaring merchants and artisans of India during the Tin-Bronze Revolution; 2. significance of Rakhigarhi as the link between Ancient Far East and Ancient Near East through navigable Himalayan riverine waterways and maritime trade through Indian Ocean Rim.

I suggest that the remarkable work done by Deccan College Archaeology team in the excavations of Rakhigarhi should be expanded further by making the Deccan College a nodel networking agency for the following research missions for two multi-disciplinary projects involving archaeology, history, language studies, geochemistry, and geology:

1. To establish the sources of Tin ores for the Tin-Bronze revolution in Ancient Far East and the role played by ancient Indian seafaring merchants and artisans in reaching the tin ore resource into all parts of Eurasia; and

2. To establish the significance of Himalayan riverwaterys (Mekong, Irrawaddy, Salween, Brahmaputra (karatoya), Ganga, Yamuna, Sarasvati, Sindhu) and links to the Indian Ocean Maritime routes (through Persian Gulf and Malacca straits) to enhance the importance of an Ancient Maritime Tin Route which linked Hanoi (Vietnam) and Haifa (Israel) through ancient India.

There is a distinct indication that the Ancient Maritime Tin Route mediated by Ancient India pre-dated the Silk road by two millennia, authenticated by Indus Script evidence on tin ingots of Haifa and on Dong Son/Karen Bronze drums of AFE.

The location of Rakhigarhi as the capital pattaṇa (riverine port) of Sarasvati Civilization is central to these missions, because Rakhigarhi is location on the ridge of the Aravalli range which constitues the water-divide between 1. west-flowing rivers of Sarasvati (Drishadvati, Chautan), Ghaggar and Sindhu and 2. east-flowing rivers of Yamuna-Ganga-Brahmaputra proximate to other Himalayan river systems of Mekong, Irrawaddy and Salween in Ancient Far East (AFE). These riverine waterways make Rakhigarhi the nodal site which managed resources of tin ores from AFE; copper/zinc ores of Khetri mineral-belt; iron ore resources of Ganga-Brahmaputra basins and progressed archaeometallurgical advances to proclaim a true Metals Age, complementing the domestication of rice, cereals, cotton cultivation and sericulture to make ancient India the richest nation on the globe contributing to 33% of Global GDP by 1 Common Era (pace Angus Madsison)..

These two missions call for a networking of multidisciplinary teams to unravel the ancient knowledge systems related to navigation along waterways and the Indian Ocean and metallurgical innovations in alloying and metal casting (cire perdue etc.) techniques.

These two missions call for a networking of multidisciplinary teams to unravel the ancient knowledge systems related to navigation along waterways and the Indian Ocean and metallurgical innovations in alloying and metal casting (cire perdue etc.) techniques.

Evaluating this Herodotus text to determine the sources of tin in Athens, James D. Muhly notes: "...it is nonetheless unlikely that we shall ever have exact knowledge about the sources of the tin being used to supply Minoan Crete or Mycenaean Greece...Of greater relevance is the revival of the concept of metallogenic provinces and the formation of metallic belts --copper belts, lead-zinc belts and tin-tungsten belts -- extending over wide areas, as part of the on-going research on plate tectonics and theories of continental drift. What this means for the archaeologist is that mineral deposition is unlikely to have taken place in random, isolated deposits and that theories positing the existence of such deposits are to be regarded with great skepticism. Most important of all is the absolute geological principle that tin is to be found only in association with granite rock. The concentration of tin varies within any single granite formation and among different formations, depending upon local conditions and geological heritage, but without granite there is no possibility of tin ever having been present. Therefore, large areas of the world are automatically ruled out as possible sources of tin. The island of Cyprus is one of these areas; since there is no granite there, it never could have contained deposits of tin...Tin is commonly present in association with pegmatites of quartz and feldspar. Like gold, the tin is found within veins of quartz running through the granite rock. The difference is that while gold occurs as a native metal, tin appears in the form of an oxide (SnO2) known as cassiterite. This cassiterite, again like gold, was frequently exposed and freed from its host through weathering and degradation of the quartz and granite. This degradation was often the result of action by water, the cassiterite (and gold) thus taking the form of small lumps or nuggets present in the stream bed. Although carried along by the force of the current, the cassiterite (and gold), having a specific gravity because of its density, tends to sink and concentrate in the bed of the streams. In general, concentration increases with proximity to the original deposit of the tin...This stream or alluvial tin was thus to be found in the form of small black nuggets of cassiterite known as tin-stone. Recovery involved the panning of the gravel in the stream bed, separating out the cassiterite from the worthless sand and gravel. The process was similar to that which must have also been used to recover gold, and what was done in antiquity was probably not that different from the techniques -- and even the equipment -- used by the Forty-Niners in the great Gold Rush in California and Alaska during the mid-nineteenth century. While gold was recovered as a native metal, the tin was to be found in the form of an oxide that had to be smelted together with charcoal in order to free the oxygen and reduce the oxide to metallic tin...Words for tin...are known in Sumerian, Akkadian, Hittite, Egyptian and Ugaritic, although not in Mycenaean Greek...Sumerian AN.NA, Akkadian annaku mean tin and all Assyriologists are in agreement on this point...Mesopotamian texts...describe the addition of AN.NA/annaku to URUDU/eru in order to produce ZABAR/siparruor, in other words, of tin to copper in order to make bronze...twenty-sixth century BCE...Tin appears in the Royal Cemetery, as at Ebla, together with gold and lapis lazuli. All three materials are to be found in Afghanistan, and it is quite possible that they did all come to Mesopotamia (and to northern Syria) via an orland route across Iran...There is as yet, no hard evidence that Sumerian tin came from Afghanistan, but such a source has long been suggested on the basis of textual and archaeological evidence-- a sugestion that up to now could only be regarded as but an interesting hypothesis because of the lack of geological evidence for the existence of tin deposits in Afghanistan...east-west movement of tin is documented in the numerous Old Assyrian texts from Kultepe, the ancient karum Kanish. Again from unspecified sources to the east, the tin was brought to Assur and from there shipped overland by donkey caravan to various Assyrian merchant colonies in Anatolia...(Afghanistan's) deposits of gold and lapis lazuli, both materials highly prized by the Sumerians during the third millennium BCE, may have led ancient prospectors to tin, which was also then exported to Sumer. It is even possible that, via Mari and Ugarit, Afghan tin was carried to Middle Minoan Crete, the land of Kaptaru..." (Muhly, James D., Sources of tin and the beginnings of bronze metallurgy, in: American Journal of Archaeology, 89 (1985), pp. 277-283, 290).

· Serge Cleuziou and Thierry Berthoud made a convincing case in May 1982 for identifying the sources of tin in the Near East. Their search extended upto Afghanistan and 'the land of Meluhha'.

" In the later 4th and early 3rd millennia, greater tin values occur-5.3% in a pin from Susa B; and 5% in an axe from Mundigak III, in Afghanistan; but these are still exceptional in a period characterized by the use of arsenical copper. It is only around 2700 B.C., during Early Dynastic III in Mesopotamia, that both the number of bronze artifacts and their general tin content increase significantly. Eight metal artifacts of forty-eight in the celebrated “vase a la cachette” of Susa D are bronzes; four of them—three vases and one axe—have over 7% tin. The analyses of objects from the Royal Cemetery at Ur present an even clearer picture: of twenty-four artifacts in the Iraq Museum subjected to analysis, eight containing significant quantities of tin and five with over 8% tin can be considered true bronzes in the traditional sense...We know that the tin came from the east, but from where? Mentions in ancient texts are rare, and only one of them, dating to the time of Gudea of Lagash (2150-2111 B.C.], speaks of the tin of Meluhha. Meluhha is one of the lands east of Mesopotamia, along with Dilmun (Bahrain) and Makkan (the peninsula of Oman). Its location is still controversial, but most scholars tend to place it in Afghanistan or Pakistan. The lists of goods imported to Mesopotamia from Meluhha point to the Indus Valley and the Harappan civilization, but it is not always easy to make a distinction between those which originated in Meluhha and those which passed through Meluhha...A long-distance trade in tin is of course hypothetical...If we now turn to the “land of Meluhha,” or at least to the vast area of which parts have been identified with Meluhha, the use of tin is attested already in the late 4th or early 3rd millennium at Mundigak III in southern Afghanistan. Tin appears only in small quanities in artifacts from Shahr-i Sokhta in eastern Iran and at Tepe Yahya in southern Iran (among the sites from which artifacts were studied). In the Indus Valley, the copper-tin alloy is known at Mohenjo-Daro...Among the products attributed to Meluhha, lapis lazuli and carnelian are found in sites and tombs of the 3rd millennium. We can suggest with reasonable certainty that the tin used in Oman was in transit through Meluhha and that the most likely source was western Afghanistan...The collective indications are that western Afghanistan was the zone able to provide the tin used in Southwest Asia in the 4th and 3rd millennia. The occurrence of tin with copper ores and the signs of earl; exploitation make it obligatory for us to consider the problem of tin in direct connection with the metallurgy of copper in this region. Since our original research design was to define copper sources, the information on tin deposits was looked upon only as a complement. In order to elucidate the questions raised by our findings, a project aimed specifically at tin—its sources and metallurgy—should be organized." (Expedition, Volume 25 Issue 1 October 1982).

http://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/early-tin-in-the-near-east/ Early Tin in the Near East -- A Reassessment in the Light of New Evidence from Western Afghanistan By: Serge Cleuziou and Thierry Berthoud

The largest tin belt of the globe is Southeast Asia. Tin-bronze revolution of ca. 5th millennium BCE can be explained by postulating a Tin Route which linked Hanoi to Haifa, more magnificent than and rivaling the later-day Silk Road. This Tin Route of yore was traversed by Bharatam Janam.

Source: http://pubs.usgs.gov/bul/1301/report.pdf Stanniferous ores are the key to tin-bronze revolution of 5th millennium BCE, creating the Tin Route more magnificent and stunning than the later-day Silk Road.

"Bronze is an alloy consisting primarily of copper, commonly with about 12% tin and often with the addition of other metals (such as aluminium,

manganese, nickel or zinc) and sometimes non-metals or metalloids such as arsenic, phosphorus or silicon. These additions produce a range of alloys that may be harder than copper alone, or have other useful properties, such as stiffness, ductility or machinability. The archeological period where bronze was the hardest metal in widespread use is known as the Bronze Age. In the ancient Near East this began with the rise of Sumer in the 4th millennium BC, with India and China starting to use bronze around the same time; everywhere it gradually spread across regions." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bronze

"The Bronze Age is a time period characterized by the use of bronze, proto-writing, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second principal period of the three-age Stone-Bronze-Iron system, as proposed in modern times by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen, for classifying and studying ancient societies. An ancient civilization is defined to be in the Bronze Age either by smelting its own copperand alloying with tin, arsenic, or other metals, or by trading for bronze from production areas elsewhere. Copper-tin ores are rare, as reflected in the fact that there were no tin bronzes in western Asia before trading in bronze began in the third millennium BCE. Worldwide, the Bronze Age generally followed the Neolithic period, with the Copper ageserving as a transition. Although the Iron Age generally followed the Bronze Age, in some areas, the Iron Age intruded directly on the Neolithic from outside the region...Bronze was independently discovered in the Maykop culture of the North Caucasus as early as the mid-4th millennium BC, which makes them the producers of the oldest known bronze. However, the Maykop culture only had arsenical bronze. Other regions developed bronze and its associated technology at different periods." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bronze_Age

manganese, nickel or zinc) and sometimes non-metals or metalloids such as arsenic, phosphorus or silicon. These additions produce a range of alloys that may be harder than copper alone, or have other useful properties, such as stiffness, ductility or machinability. The archeological period where bronze was the hardest metal in widespread use is known as the Bronze Age. In the ancient Near East this began with the rise of Sumer in the 4th millennium BC, with India and China starting to use bronze around the same time; everywhere it gradually spread across regions." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bronze

"The Bronze Age is a time period characterized by the use of bronze, proto-writing, and other early features of urban civilization. The Bronze Age is the second principal period of the three-age Stone-Bronze-Iron system, as proposed in modern times by Christian Jürgensen Thomsen, for classifying and studying ancient societies. An ancient civilization is defined to be in the Bronze Age either by smelting its own copperand alloying with tin, arsenic, or other metals, or by trading for bronze from production areas elsewhere. Copper-tin ores are rare, as reflected in the fact that there were no tin bronzes in western Asia before trading in bronze began in the third millennium BCE. Worldwide, the Bronze Age generally followed the Neolithic period, with the Copper ageserving as a transition. Although the Iron Age generally followed the Bronze Age, in some areas, the Iron Age intruded directly on the Neolithic from outside the region...Bronze was independently discovered in the Maykop culture of the North Caucasus as early as the mid-4th millennium BC, which makes them the producers of the oldest known bronze. However, the Maykop culture only had arsenical bronze. Other regions developed bronze and its associated technology at different periods." https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bronze_Age

"The land between the Euphrates and Tigris is sedimentary and therefore devoid of metals...Some semi-precious stones came from an even greater distance, cornelian from the Indian subcontinent, and lapis lazuli from Central Asia...The regions furthest to the East about which the ancient Mesopotamians had some knowledge appear to be the Indus valley (Meluhha) and Turkmenistan (Shimashki). The legendary country Aratta figures in several Sumerian epics as the distant adversary of Uruk. One can find references to the alleged trade between Uruk and Aratta in the secondary literature...Of great importance are the remains of the cargo discovered in two Late Bronze Age shipwrecks off the South coast of Turkey. The wreck near Cape Gelidonya (late 13th c. BCE) is thought to have come from Phoenicia. Its cargo consisted mainly of copper, tin, and bronze: copper in the shape of 34 oxhides (averaging 25 kg each)) and a number of bun ingots (averaging 3 kg each), tin ingots, and scrap bronze tools. Beter preserved is the shipwreck of Uluburun (late 14th c.) with a cargo of an estimated 20 tons of weight, including 354 copper oxhide ingots (1bout 10 tons), 121 copper bun ingots (about 1 ton), 110 tin ingot fragmens (about 1 ton), and 175 glass ingots (about 300 kg.)...The copper used in Syria and Mesopotamia came from different sources according to the textual evidence. One route led via the southern city of Ur, which possessed a harbour giving access to the Persian Gulf and beyond. The copper obtained from Tilmun from ca. 21st-18th c. BCE came from Oman, where impressive remains of ancient copper workings have been identified dating to this period...Tin is alloyed with copper to obtain bronze. It is first attested in a pin from Tepe Gawra Level VIII (ca. 3000 BCE), with a content of 5.6% tin. At the time of the royal tombs of Ur (Early Dynastic IIIa. ca. 2700 BCE), bronze appears to be the most commonly used...Weeks contrasted the very limited presence of tin-bronzes in third millennium context in sites of the Iranian Plateau to the significant use of tin-bronze in Baluchistan, the Indus Valley, the Persian Gulf and south-western Iran during the same period. Since the use of tin will have been greatest along the trade route by which it was transported, he convincingly argues that this tin came via the Indian peninsula from one or more Central Asian sources. This is the famous trade with distant Meluhha, which started in the third millennium with the growing importance of the Indus civilisation, and lasted until its decline in about 1900 BCE. The supply of tin by sea route is suggested in a passage in one of the texts of Gudea (Cyl. B xiv 13): 'Along with copper, tin, slabs of lapis lazuli, shining metal (and) spotless Meluhha cornelian' (RIME 3/1,96). After the collapse of Meluhha, tin apparently was traded by an overland route cross Iran. It probably was via this overland route that the tin reached Susa in western Iran from where it was distributed westwards as is documented for the Old Babylonian period. One important route in Mesopotamia ran East of he Tigris to Assur in the North, from where Assyrian traders transported large quantities of tin to Anatolia (documented for the 19th-18th c.). The fact that they exported tin to Anatolia corroborates the view that workable deposits did not exist there...The latest reference to this city (Assur) as a source of tin is contained in an Old Babylonian letter found at the Middle Euphrates site of Haradum, which dates to the reign of Ammi-shaduqa (1683-1626 BCE). The passage reads: 'I entrusted 1 talent 20 minas of tin (= 40kg) to Hushunu, the Ahlami soldier, a guard of the kārum of Haradu, (in) Assur and I had him carry it to Haradum'...King Zimrilim's merchants were allowed to purchase tin and lapis lazuli in Susa. Zimrilim used the tin as diplomatic gifts to rulers in Ugarit, Hazor and other places in the Levant. The gifts made by Zimrilim and earlier by his predecessor Yasmah-Addu (to the king of Apishal) seem to be the only attested cases of tin moving to West Syria by way of Mari...The Uluburn shipwreck discovered off the Turkish coast had a cargo of almost 1,000 kg of tin and (Cypriot) copper, and apparently was heading for a western destination when it sank...tin figures among the tribute, which Neo-Assyrian kings received in North Syria and in the region around Diyarbakir. For example, king Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE) received tribute from Patina (near modern Antakya), which included 600 kg of silver, 30 kg of gold, 3000 kg of iron, and 3000 kg of tin (RI-MA 2, 217 f.)...end of the Neo-Assyrian period (reign of Sin-shar-ishkun, ending 612 BCE), where tin (bdl) is mentioned as payment for a horse or a gift to the god hadad of Gozan. Less than a century later, Transeuphratene was the area where Babylonian merchants from Neo-Babylonian Uruk obtained tin for the Eanna temple according to several texts...Old Assyrian trade (20th-18th c. BCE)...linked the city of Assur with Central Anatolia...(trade) profited from the development of an institutional and legal framework to acommodate trade from about 2000 BCE onwards, in which groups of merchants from a particular town forged long-term relationships with other towns and their rulers through the kārum-system (kārum 'quay, harbour, commercial district). Non-Assyrian caravans brought tons of tin, cornelian and iron to Assur, where local merchants purchased these goods. By means of donkey caravans the goods were shipped to Anatolia and sold there for silver and gold. Kanesh was the main hub of a network of some twenty Assyrian commercial settlements in or close to economically important cities or regions in Anatolia. To facilitate this trade, Assur concluded treaties with local rulers that permitted it to establish trade colonies in existing cities of economic or logistical importance. A string of settlements also existed on the main caravan route from Assur to Anatolia in northern Iraq and Syria...The amount of tin and textiles sent by individual merchants to Anatolia differed considerably. A simple donkey load consisted of some 65 kg of tin, plus some textiles. One particular letter (Kt ck 443) announces the coming to Anatolia of a large convoy consisting of 21 donkeys, carrying 300 kg of tin and 400 assorted textiles. This represented significant load. The shipwreck of Uluburn, however, had a cargo of an estimated 10 tons of copper and 1 ton of tin. The ton of tin equals some 15 donkey-loads. Small as such an amount may seem, it is almost the total estimated yield of one of the mines discovered in Tajikistan. The shipment of textiles and tin to Anatolia was an Assyrian monopoly. There were no traders from Babylon active in Kanesh, but we know that merchants from North Syria (Ebla, Hashshum) were also involved in trade with Anatolia...Obviously, not only Mesopotamian merchants went abroad. Foreign merchants also travelled to Mesopotamia to sell goods. A royal inscription of the Old Akkadian King Sargon (2300) contains a unique hint at the extent of long-distance trade, when he claims that he 'moored the ships of Meluhha, Magan, and Tilmun at the quay of Agade' (RIME 2, 28). The tin and textiles that Assyrian merchants exported to Anatolia reached Assur by means of caravans from Babylonia, and, presumably, Susa...The coastal kingdom of Ugarit was a centre from where copper, tin, alum or lapis lazuli could be sent on to Carchemish and Hatti...Two letters addressed to the king of Ugarit by Tagubli, his representative with the court of Carchemish, deal with the sending of genuine lapis lazuli as a gift to the Hittite king. Urtenu appears as a manager of the palace storage facilities and stables, able to issue horses and donkeys, as well as copper, tin, alum, blue-purple wool, and textiles."

(Jan Gerrit Dercksen, Mineral resources and demand in the Ancient Near East, in: La Natura Nel Vicino Oriente Antico, Atti del Convegno internationale, Milano, 2009, Edizioni Ares, pp. 43-75)

(Jan Gerrit Dercksen, Mineral resources and demand in the Ancient Near East, in: La Natura Nel Vicino Oriente Antico, Atti del Convegno internationale, Milano, 2009, Edizioni Ares, pp. 43-75)