-- Indus Script hieroglyphs camel, elephant, monkeys, water-buffalo, one-horned young bull, antelope are rebus rendered as wealth metalwork sources, and hence constitute tributes to Shalmaneser III (858-824 BCE) from Musri, a region now called Kurdistan in northern Iraq.

It appears the Meluhha were seafaring merchants, artisans and settlers in this region.

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser

"He will raise a signal for a nation from afar off, and whistle for it from the ends of the earth; and lo, swiftly, speedily it comes." Isaiah 5:26

Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), in northern Iraq.was discovered by archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1846.

Some features of the black obelisk might suggest that the work had been commissioned by the commander-in-chief, Dayyan-Ashur.

Campaigns of Shalmaneser III (858-824 BCE)

"The site of Nimrud is located on the Tigris River southeast of Mosul in the north of modern day Iraq. Today the city lies some kilometers east of the Tigris, but in antiquity the river flowed along the northwest side of the acropolis. The site was occupied intermittently from the 6th millennium BC to at least the Hellenistic period, but the most significant period of occupation occurred during the Late Assyrian period, when Assurnasirpal II (883-859 BC) built Nimrud as the capital of his empire. The city remained the chief royal residence and administrative capital of the Assyrian empire until the reign of Sargon II (721-705 BC), though Esarhaddon (680-669 BC) later rebuilt much of the citadel.-- Klaudia Englund"

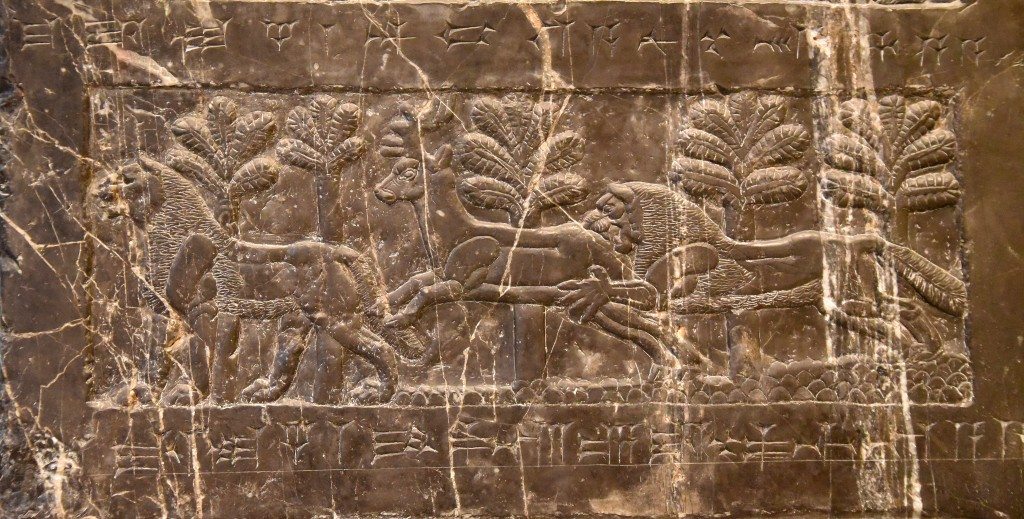

Inscription read as: Tribute of the land of Musri. Camels whose backs are doubled, a river ox (hippopotamus), a sakea (rhinoceros), a susu (antelope), elephants, bazîtu (and) uqupu (monkeys), I received from him.

S.M. Amin's photographs produce clear images of Sides A,B,C, D on the register related to tributes from Musri. Musri (Assyrian: Mu-us-ri), or Muzri, was a small ancient kingdom, in northern areas of Iraqi Kurdistan. The area is now inhabited by Muzuri (Mussouri) Kurds. See reference to Musri in Inscription of Tiglath-Pileser I, King of Assyria: http://www.sacred-texts.com/ane/rp/rp201/rp20126.htm

Since the tributes received from Musri include the three animal hieroglyphs which are normally shown on Indus Script inscriptions, though the iconographic style may be from recollected memory, the cuneiform inscription related to these tributes (or animal hieroglyphs) as: river ox (water buffalo?), sakea (translated as rhinoceros), susu (translated as antelope), elephants, bazitu/uqupu (translated as monkeys). See Ancient Records, Univ. of Chicago, Oriental Institute:

The caption for the third row from the top reads:

(p.211)https://oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/ancient_records_assyria1.pdf

On this third row from the top, the following observations of curators of Metmuseum are apposite:

“Shalmaneseeer never went to Egypt, but he may have approached it after visiting the coast of Lebanon in 837 BCE. There is no suggestion of an individual ruler submitting on the front panel in this row, and there is no Assyrian official to introduce the tribute. Instead, all the panels seem to show exotic animals such as those the Assyrian kings liked to receive for their wildlife parks. This suggests that the consignment was probably a diplomatic gift. The caption and the illustrations in this row of panels help explain one another. The two-humped camels on the front, and the ‘rive ox’ on the right hand side, which bears a slight resemblance to a water buffalo, would both have been exotic in Egypt, though it is unclear how they may have arrived there. The translation ‘rhinoceros’ in the caption is based on the appearance of a single-horned animal in the centre of the right-hand panel, between the ‘river ox’ and an antelope; this beast could be how an Assyrian might have drawn a rhinoceros if he had never seen one but was working from a description. The elephant on the back face could be the small North African type, now extinct. Four more monkeys or apes, each with its keeper, occupy the remainder of the panels on the back and left hand side.” Joan Aruz, Sarah B. Graff, Yelena Rakic, 2014, Assyria to Iberia at the Dawn of the Classical Age, MetMuseum of Art, New York, p.64).”

It appears that the tributes from the land of Musri may ultimately from Meluhha since the hieroglyphs used are from Indus Script Cipher. I suggest that the cuneiform inscription refers to the animals specified as tributes. This is consistent with the decipherment of most of Indus Script Corpora as wealth-accounting ledgers of metalwork.

Water-buffalo: Hieroglyph: rã̄go 'water-buffalo' rebus: Pk. raṅga 'tin' P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼOr. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼraṅgaada -- m. ʻ borax ʼ lex.Kho. (Lor.) ruṅ ʻ saline ground with white efflorescence, salt in earth ʼ *raṅgapattra ʻ tinfoil ʼ. [raṅga -- 3, páttra -- ]B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.(CDIAL 10562) ranga 'alloy of copper, zinc, tin'.

River ox: Hieroglyph, short-horned bull: barad, balad, 'ox' rebus: bharata 'metal alloy' (5 copper, 4 zinc and 1 tin).

Does sakea in the black obelisk inscription signify 'unicorn' i.e. animal shown on Indus Script with one horn? " I suggest that this signifies the 'one-hored young bull with a curved, s-shaped, mutilated horn' shown on thousands of Indus Script Inscriptions.

Elephant, camel: Hieroglyphs: karibha, ibha 'elephant' karabhá m. ʻ camel ʼ MBh., ʻ young camel ʼ Pañcat., ʻ young elephant ʼ BhP. 2. kalabhá -- ʻ young elephant or camel ʼ Pañcat. [Poss. a non -- aryan kar -- ʻ elephant ʼ also in karḗṇu -- , karin -- EWA i 165] 1. Pk. karabha -- m., ˚bhī -- f., karaha -- m. ʻ camel ʼ, S. karahu, ˚ho m., P. H. karhā m., Marw. karhau JRAS 1937, 116, OG. karahu m., OM. karahā m.; Si. karaba ʻ young elephant or camel ʼ.2. Pa. kalabha -- m. ʻ young elephant ʼ, Pk. kalabha -- m., ˚bhiā -- f., kalaha -- m.; Ku. kalṛo ʻ young calf ʼ; Or. kālhuṛi ʻ young bullock, heifer ʼ; Si. kalam̆bayā ʻ young elephant ʼ Rebus: karba, ib 'iron'Addenda: karabhá -- : OMarw. karaha ʻ camel ʼ.

Monkeys: hieroglyphs: kuṭhāru कुठारु monkey; rebus: kuṭhāru, कुठारु an armourer.

Thus, the tributes received are iron implements, metal armour, lapidary metalwork wealth from Meluhha and tin ore (ranku 'antelope' rebus; ranku 'tin').

[quote] There were animals with one horn such as the narwal (a small whale with a long horn); the "sakea" which was a kind of goat like deer depicted by the Assyrians with one horn. In some opinions the sakea was a mythical animal (THE ARAB FRINGE. AN ENQUIRY CONCERNING Mutsri, KUSH, MELUHHA AND MAGAN by Michael Banyai http://www.abara2.de/chronologie/fringe.php)...The Lion and Unicorn were representative of Israel in its aspect of power in the End Times. The lion and unicorn are on the coat of arms officially symbolizing Britain. Bilaam the heathen prophet foresaw that in the End Times the descendants of Israel would be very powerful. He likened them to a lion and a raem or unicorn.

The Coat of Arms of Britain![lion and unicorn Britain]()

The Coat of Arms of Scotland![two unicorns Scotland]()

<<GOD BROUGHT THEM OUT OF EGYPT; HE HATH AS IT WERE THE STRENGTH OF AN UNICORN.

<<SURELY THERE IS NO ENCHANTMENT AGAINST JACOB, NEITHER IS THERE ANY DIVINATION AGAINST ISRAEL: ACCORDING TO THIS TIME IT SHALL BE SAID OF JACOB AND OF ISRAEL, WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT!

<<BEHOLD, THE PEOPLE SHALL RISE UP AS A GREAT LION, AND LIFT UP HIMSELF AS A YOUNG LION: HE SHALL NOT LIE DOWN UNTIL HE EAT OF THE PREY, AND DRINK THE BLOOD OF THE SLAIN>> [Numbers 23:22-24]. The symbols of Scotland had two unicorns and that of the United Kingdom of Great Britain had a lion and a unicorn. The Midrash (Numbers Rabah) says that the raem (unicorn) was the symbol of MANASSEH. In our passage Israel is likened to a unicorn. Only in Britain does the unicorn appear as a national symbol. On the other hand the unicorn came to Britain from Scotland which is still represented by two unicorns. More than 80% of the founding settlers of the USA came from Scotland and related areas in the North and West of Britain.[unquote] -- Yair Davidiy

http://www.britam.org/Proof/Joseph/joUnicorn.html

<<GOD BROUGHT THEM OUT OF EGYPT; HE HATH AS IT WERE THE STRENGTH OF AN UNICORN.

<<SURELY THERE IS NO ENCHANTMENT AGAINST JACOB, NEITHER IS THERE ANY DIVINATION AGAINST ISRAEL: ACCORDING TO THIS TIME IT SHALL BE SAID OF JACOB AND OF ISRAEL, WHAT HATH GOD WROUGHT!

<<BEHOLD, THE PEOPLE SHALL RISE UP AS A GREAT LION, AND LIFT UP HIMSELF AS A YOUNG LION: HE SHALL NOT LIE DOWN UNTIL HE EAT OF THE PREY, AND DRINK THE BLOOD OF THE SLAIN>> [Numbers 23:22-24]. The symbols of Scotland had two unicorns and that of the United Kingdom of Great Britain had a lion and a unicorn. The Midrash (Numbers Rabah) says that the raem (unicorn) was the symbol of MANASSEH. In our passage Israel is likened to a unicorn. Only in Britain does the unicorn appear as a national symbol. On the other hand the unicorn came to Britain from Scotland which is still represented by two unicorns. More than 80% of the founding settlers of the USA came from Scotland and related areas in the North and West of Britain.[unquote] -- Yair Davidiy

Side A: Attendants bring tribute from Musri in the form of two-humped camels. Unlike the upper registers on side A, neither Shalmaneser III nor the subdued ruler appear. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side A: Attendants bring tribute from Musri in the form of two-humped camels. Unlike the upper registers on side A, neither Shalmaneser III nor the subdued ruler appear. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side B: This register depicts exotic animals from Musri in the form of a river-ox, a rhinoceros (and) an antelope. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: This register depicts exotic animals from Musri in the form of a river-ox, a rhinoceros (and) an antelope. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The black obelisk of shalmaneser III (858 - 824 bc) From left to right : a river ox (water buffalo), an Indian rhinoceros and an antelope. As the British museum plaque next to the obelisk explained: the sculptor had clearly never seen a rhinoceros!

Side C: There are female elephants, female monkeys (and) apes. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: There are female elephants, female monkeys (and) apes. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side D: There are more monkeys with their keepers. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: There are more monkeys with their keepers. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III is a black limestone Assyrian sculpture with many scenes in bas-relief and inscriptions. It comes from Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), in northern Iraq, and commemorates the deeds of King Shalmaneser III (reigned 858–824 BC). It is on display at the British Museum in London, and several other museums have cast replicas.

It is the most complete Assyrian obelisk yet discovered, and is historically significant because it is thought to display the earliest ancient depiction of a biblical figure – Jehu, King of Israel. The traditional identification of "Yaw" as Jehuhas been questioned by some scholars, who proposed that the inscription refers to another king, Jehoram of Israel.[1][2] Its reference to Parsua is also the first known reference to the Persians.

Tribute offerings are shown being brought from identifiable regions and peoples. It was erected as a public monument in 825 BC at a time of civil war, in the central square of Nimrud, close to the much earlier White Obelisk of Ashurnasirpal I. It was discovered by archaeologist Sir Austen Henry Layard in 1846 and is now in the British Museum.

It features twenty relief scenes, five on each side. They depict five different subdued kings, bringing tribute and prostrating before the Assyrian king. From top to bottom they are: (1) Sua of Gilzanu (in north-west Iran), (2) "Jehu of Bit Omri" (Jehu of the House of Omri), (3) an unnamed ruler of Musri (probably Egypt), (4) Marduk-apil-usur of Suhi (middle Euphrates, Syria and Iraq), and (5) Qalparunda of Patin (Antakya region of Turkey). Each scene occupies four panels around the monument and is described by a cuneiform script above them.

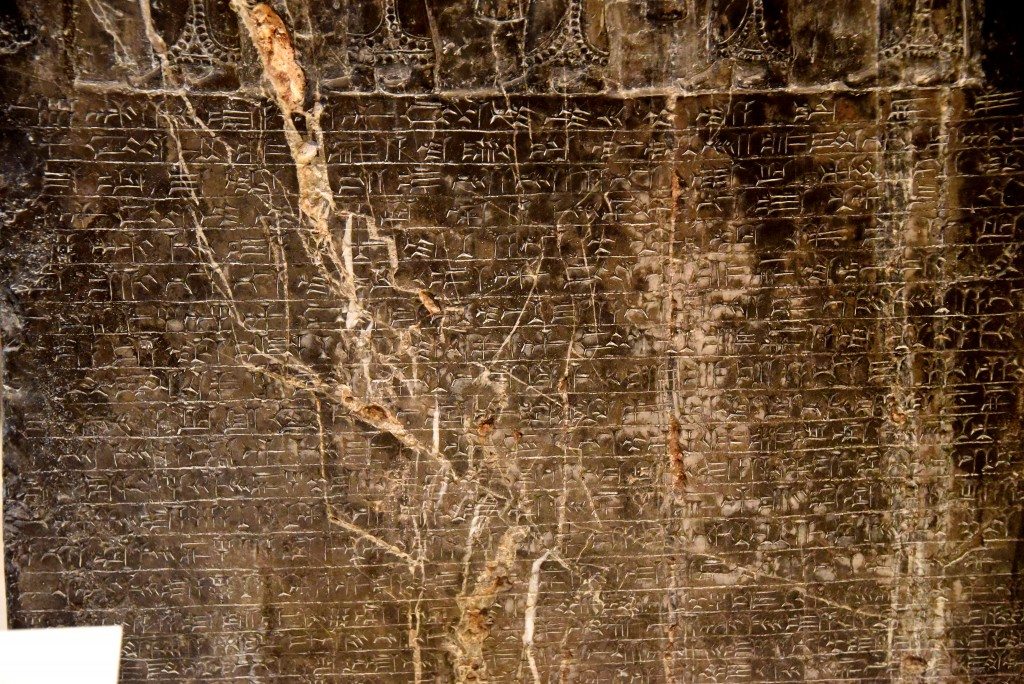

On the top and the bottom of the reliefs there is a long cuneiform inscription recording the annals of Shalmaneser III. It lists the military campaigns which the king and his commander-in-chief headed every year, until the thirty-first year of reign. Some features might suggest that the work had been commissioned by the commander-in-chief, Dayyan-Assur.

Replicas can be found at the Oriental Institute in Chicago, Illinois; Harvard's Semitic Museum in Cambridge, Massachusetts; the ICOR Library in the Semitic Department at The Catholic University of America in Washington, D.C.; Corban University's Prewitt–Allen Archaeological Museum in Salem, Oregon; the Siegfried H. Horn Museum at Andrews University in Berrien Springs, MI; Canterbury Museum in Christchurch, New Zealand; the Museum of Ancient Art at Aarhaus University in Denmark, and in the library of the Theological University of the Reformed Churches in Kampen, the Netherlands. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Black_Obelisk_of_Shalmaneser_III![]() Neo-Assyrian, Nimrud, Black Obelisk, Gold Goblets, Pitchers, Tin Staves

Neo-Assyrian, Nimrud, Black Obelisk, Gold Goblets, Pitchers, Tin Staves

In December 1846, while working with his excavation team at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu or biblical Calah), located in northern Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq, Sir Austen Henry Layard discovered the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser. It was in a perfect state of preservation and is still considered the only complete Assyrian obelisk ever found. It was later on transferred to the British Museum. ** (Article and photos by Osama S.M. Amin) ancient.eu/2016/07/14/black-obelisk-of-shalmaneser-iii-british-museum/

In December 1846, while working with his excavation team at Nimrud (ancient Kalhu or biblical Calah), located in northern Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq, Sir Austen Henry Layard discovered the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser. It was in a perfect state of preservation and is still considered the only complete Assyrian obelisk ever found. It was later on transferred to the British Museum. ** (Article and photos by Osama S.M. Amin) ancient.eu/2016/07/14/black-obelisk-of-shalmaneser-iii-british-museum/What is The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser?

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III is a four-sided monument or pillar made of black limestone. It stands about 6 1/2 feet tall. It was discovered in 1846 by A.H. Layard in the Central Palace of Shalmaneser III at the ruins of Nimrud, known in the Bible as Calah, and known in ancient Assyrian inscriptions as Kalhu. It is now on display in the British Museum.

The Obelisk contains 5 rows of bas-relief (carved) panels on each of the 4 sides, 20 panels in all. Directly above each panel are cuneiform inscriptions describing tribute offered by submissive kings during Shalmaneser's war campaigns with Syria and the West.

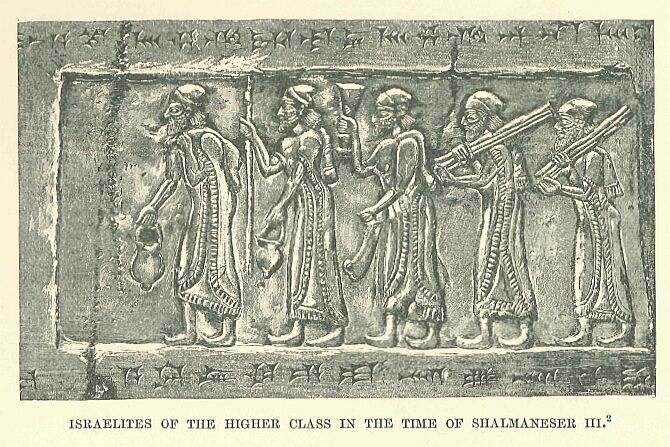

The "Jehu Relief" is the most significant panel because it reveals a bearded Semite in royal attire bowing with his face to the ground before king Shalmaneser III, with Hebrew servants standing behind him bearing gifts. The cuneiform text around it reveals the tribute bearer and his gifts, it says:

"The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received from him silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears."

The Assyrians referred to a northern Israel king as a "son of Omri", whether they were a direct son of Omri or not. Other Assyrian inscriptions reveal Israel's southern kings from Judah, as recorded on Sennacherib's Clay Prism (also known as the Taylor Prism) which reads "Hezekiah the Judahite".

The Black Obelisk has been precisely dated to 841 BC, due to the accurate Assyrian dating methods. One modern scholar refers to the accuracy of Assyrian records:

"Assyrian records were carefully kept. The Assyrians coordinated their records with the solar year. They adopted a system of assigning to each year the name of an official, who was known as the "limmu." In addition, notation was made of outstanding political events in each year, and in some cases reference was made to an eclipse of the sun which astronomers calculate occured on June 15, 763 B.C. Assyriologists have been able to compile a list of these named years, which they designate "eponyms," and which cover 244 years (892-648 B.C.). These records are highly dependable and have been used by Old Testament scholars to establish dates in Hebrew History, particularly during the period of the monarchy."

Walter G. Williams, "Archaeology in Biblical Research" (Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press, 1965) p. 121.

Walter G. Williams, "Archaeology in Biblical Research" (Nashville, Tennessee: Abingdon Press, 1965) p. 121.

Shalmaneser III ruled ancient Assyria from 858-824 BC., and was the son of Assurnasirpal II.

British Museum Excerpt

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

Neo-Assyrian, 858-824 BC

From Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq

The military achievements of an Assyrian king

The archaeologist Henry Layard discovered this black limestone obelisk in 1846 during his excavations of the site of Kalhu, the ancient Assyrian capital. It was erected as a public monument in 825 BC at a time of civil war. The relief sculptures glorify the achievements of King Shalmaneser III (reigned 858-824 BC) and his chief minister. It lists their military campaigns of thirty-one years and the tribute they exacted from their neighbours: including camels, monkeys, an elephant and a rhinoceros. Assyrian kings often collected exotic animals and plants as an expression of their power.

There are five scenes of tribute, each of which occupies four panels round the face of the obelisk and is identified by a line of cuneiform script above the panel. From top to bottom they are:

Sua of Gilzanu (in north-west Iran)

Jehu of Bit Omri (ancient northern Israel)

An unnamed ruler of Musri (probably Egypt)

Marduk-apil-usur of Suhi (middle Euphrates, Syria and Iraq)

Qalparunda of Patin (Antakya region of Turkey)

The second register from the top includes the earliest surviving picture of an Israelite: the Biblical Jehu, king of Israel, brought or sent his tribute in around 841 BC. Ahab, son of Omri, king of Israel, had lost his life in battle a few years previously, fighting against the king of Damascus at Ramoth-Gilead (I Kings xxii. 29-36). His second son (Joram) was succeeded by Jehu, a usurper, who broke the alliances with Phoenicia and Judah, and submitted to Assyria. The caption above the scene, written in Assyrian cuneiform, can be translated

The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received from him silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears.

Height: 197.85 cm

Width: 45.08 cm

Excavated by A.H. Layard

ANE 118885

Room 6, Assyrian sculpture

Neo-Assyrian, 858-824 BC

From Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq

The military achievements of an Assyrian king

The archaeologist Henry Layard discovered this black limestone obelisk in 1846 during his excavations of the site of Kalhu, the ancient Assyrian capital. It was erected as a public monument in 825 BC at a time of civil war. The relief sculptures glorify the achievements of King Shalmaneser III (reigned 858-824 BC) and his chief minister. It lists their military campaigns of thirty-one years and the tribute they exacted from their neighbours: including camels, monkeys, an elephant and a rhinoceros. Assyrian kings often collected exotic animals and plants as an expression of their power.

There are five scenes of tribute, each of which occupies four panels round the face of the obelisk and is identified by a line of cuneiform script above the panel. From top to bottom they are:

Sua of Gilzanu (in north-west Iran)

Jehu of Bit Omri (ancient northern Israel)

An unnamed ruler of Musri (probably Egypt)

Marduk-apil-usur of Suhi (middle Euphrates, Syria and Iraq)

Qalparunda of Patin (Antakya region of Turkey)

The second register from the top includes the earliest surviving picture of an Israelite: the Biblical Jehu, king of Israel, brought or sent his tribute in around 841 BC. Ahab, son of Omri, king of Israel, had lost his life in battle a few years previously, fighting against the king of Damascus at Ramoth-Gilead (I Kings xxii. 29-36). His second son (Joram) was succeeded by Jehu, a usurper, who broke the alliances with Phoenicia and Judah, and submitted to Assyria. The caption above the scene, written in Assyrian cuneiform, can be translated

The tribute of Jehu, son of Omri: I received from him silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden tumblers, golden buckets, tin, a staff for a king [and] spears.

Height: 197.85 cm

Width: 45.08 cm

Excavated by A.H. Layard

ANE 118885

Room 6, Assyrian sculpture

Gifts and tributes brought to Shalamaneser include water-ox, rhino, antelope, elephant, monkeys, two-humped camels

Black Obelisk of King Shalmaneser III of Assyria

from Atour: The State of Assyria: http://www.atour.com/

This inscription is engraved on an obelisk of black marble, five feet in height, found by Mr. Layard in the centre of the Mound at Nimrud, and now in the British Museum. Each of its four sides is divided into five compartments of sculpture representing the tribute brought to the Assyrian King by vassal princes, Jehu of Israel being among the number. Shalmaneser, whose annals and conquests are recorded upon it, was the son of Assurnasirpal, and died in 823 B.C., after a reign of thirty-five years. A translation of the inscription was one of the first achievements of Assyrian decipherment, and was made by Sir. H. Rawlinson; and Dr. Hincks shortly afterward (in 1851) succeeded in reading the name of Jehu in it. M. Oppert translated the inscription in his "Histoire des Empires de Chaldee et d'Assyrie," and M. Menant has given another rendering of it in his "Annales des Rois d'Assyrie" (1874). A copy of the text will be found in Layard's "Inscriptions in the Cuneiform Character" (1851).

Face A[1] Assur, the great Lord, the King of all [2] the great gods; Anu, King of the spirits of heaven [3] and the spirits of earth, the god, Lord of the world; Bel [4] the Supreme, Father of the gods, the Creator; [5] Hea, King of the deep, determiner of destinies, [6] the King of crowns, drinking in brilliance; [7] Rimmon, the crowned hero, Lord of canals; the Sun-god [8] the Judge of heaven and earth, the urger on of all; [9] (Merodach), Prince of the gods, Lord of battles; Adar, the terrible, [10] (Lord) of the spirits of heaven and the spirits of earth, the exceeding strong god; Nergal, [11] the powerful (god), King of the battle; Nebo, the bearer of the high sceptre, [12] the god, the Father above; Beltis, the wife of Bel, mother of the (great) gods; [13] Istar, sovereign of heaven and earth, who the face of heroism perfectest; [14] the great (gods), determining destinies, making great my kingdom. [15] (I am) Shalmaneser, King of multitudes of men, prince (and) hero of Assur, the strong King, [16] King of all the four zones of the Sun (and) of multitudes of men, the marcher over [17] the whole world; Son of Assur-natsir-pal, the supreme hero, who his heroism over the gods [18] has made good and has caused all the world to kiss his feet;

Translations of the inscriptions describing each scene, follow:

I. Tribute of Sua, the Gilzanite. Silver, gold, lead, copper vessels, staves (staffs) for the hand of the king, horses, camels, whose backs are doubled, I received from him.II. Tribute of Jehu, son of Omri. Silver, gold, a golden saplu (bowl), a golden vase with pointed bottom, golden goblets, pitchers of gold, tin, staves (staffs) for the hand of the king, puruhtu (javelins?), I received from him.III. Tribute of the land of Musri. Camels whose backs are doubled, a river ox (hippopotamus), a sakea (rhinoceros), a susu (antelope), elephants, bazîtu (and) uqupu (monkeys), I received from him.IV. Tribute of Marduk-apal-usur of Suhi. Silver, gold, pitchers of gold, ivory, javelins, buia, brightly colored and linen garments, I received from him.V. Tribute of Karparunda of Hattina. Silver, gold, lead, copper, copper vessels, ivory, cypress (timbers), I received from him.

- Where, when and by whom was the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III found?

- Describe the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.

- List some of the gods of Assyria and their realms as shown on the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III?

- What does this introduction to the annals of Shalmaneser tell us about Assyrian society?

- How is Shalmaneser III portrayed on the obelisk?

- What does the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III tell us about Assyria’s relations with other cities and states?

- What is tribute?

- What types of tribute were exacted on defeated cities? https://sites.google.com/a/syd.catholic.edu.au/boudica/year-11-ancient-history/assyria/black-obelisk

Published on July 14, 2016 The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III at the British Museum written by Osama S. M. Amin

Iwas attending an event at the Royal College of Physicians of London in early March 2016, and I had a plenty of time to spare. One of my targets was, of course, the British Museum. Two years ago, Jan van der Crabben(founder and CEO of the Ancient History Encyclopedia) asked me to draft a blog article about the Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, but I lacked detailed and high-quality images of all aspects of the obelisk. Nowadays, I’m equipped with a Nikon D750 full-frame camera and incredible lenses. So let’s spend some time looking at the obelisk and enjoy its wonderful artistic scenes.

The obelisk lies at the heart of Room 6 of the Ground Floor. The overall surrounding lighting is unfortunately scarce, but who cares, my camera can overcome this very easily! Remember, no “flash” photography is allowed.

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III at Room 6 of the Ground Floor of the British Museum, London. We can see side A (right, beginning of the scenes) and side D (left, end of the scenes). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III at Room 6 of the Ground Floor of the British Museum, London. We can see side A (right, beginning of the scenes) and side D (left, end of the scenes). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.In December 1846, while working with his excavation team at Nimrud(ancient Kalhu or biblical Calah), located in northern Mesopotamia in present-day Iraq, Sir Austen Henry Layard discovered the obelisk. It was in a perfect state of preservation and is still considered the only complete Assyrian obelisk ever found. It was later on transferred to the British Museum (BM “Big number” 118885; Registration Number 1848,1104.1).

The obelisk is a black limestone stela or a monument. It was erected in the year 825 BCE within the courtyard of the so-called “Central Building” within Kalhu (the Assyrian capital at that time) as a public monument during a civil war and turbulence . The obelisk is 197.48 cm in height, 81.91 cm height (of plinth), and 45.08 cm in width. The top was made in the shape of a ziggurat.

The ziggurat-shaped top of the Black Obelisk, sides A (right) and D (left). Note the Akkadian cuneiform inscriptions. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

The obelisk commemorates 31 years of military campaigns conducted by the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (reigned 858-824 BCE). The obelisk has four sides. On each side, we can see five vertically arranged registers (or scenes). Each scene tells a story about a subdued king or ruler, who is paying tribute and prostrating before the victorious Assyrian king Shalmaneser III; however, two out of the five kings were depicted on the registers. Each individual scene narrates horizontally, using Akkadian cuneiform inscriptions and carved reliefs, from one side to another (in an anti-clockwise manner), wrapping around the obelisk. Therefore, there are five stories from top to bottom, in 20 registers.

There are cuneiform the inscriptions carved on the base of the Obelisk. This is side A. Note the damages incurred during the transportation of the Obelisk. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

There are cuneiform the inscriptions carved on the base of the Obelisk. This is side A. Note the damages incurred during the transportation of the Obelisk. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.The obelisk became historically important because it depicts and documents Jehu of the House of Omri (king of Israel), and therefore, a biblical figure.

Jehu (son of Omri), king of Israel, bows and prostrates before Shalmaneser III. The Assyrian king is accompanied by four attendants. Jehu is thought to be a biblical figure. Detail of the Black Obelisk, Side A, register 2. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Jehu (son of Omri), king of Israel, bows and prostrates before Shalmaneser III. The Assyrian king is accompanied by four attendants. Jehu is thought to be a biblical figure. Detail of the Black Obelisk, Side A, register 2. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Jehu (son of Omri), king of Israel, bows and prostrates before the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (not shown). An Assyrian attendant stands behind Jehu. Jehu is thought to be a biblical figure. Detail of the Black Obelisk, Side A, register 2. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Jehu (son of Omri), king of Israel, bows and prostrates before the Assyrian king Shalmaneser III (not shown). An Assyrian attendant stands behind Jehu. Jehu is thought to be a biblical figure. Detail of the Black Obelisk, Side A, register 2. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.I will describe each horizontal scene (from top to bottom), not the individual sides separately.

Scene 1: King Shalmaneser III receives tribute from Sua of Gilzanu (of modern day north-west Iran): Shalmaneser says that I received tribute from Sua the Gilzanean, silver, gold, tin, bronze, cauldrons, the staffs of the king’s hand, horses (and) two-humped camels.

Side A: King Shalmaneser III holds a bow and receives tribute from Sua the Gilzanean (who bows before the king). Two attendants stand behind the king. The king looks at his field marshal and another unnamed official. Symbols of gods Assur (right) and Ishtar (left) are seen before the king’s head. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side A: King Shalmaneser III holds a bow and receives tribute from Sua the Gilzanean (who bows before the king). Two attendants stand behind the king. The king looks at his field marshal and another unnamed official. Symbols of gods Assur (right) and Ishtar (left) are seen before the king’s head. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side B: There are two Assyrian officials, a foreign groom, and a horse with rich trappings (which represent the horses for which Gilzanu was famous). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: There are two Assyrian officials, a foreign groom, and a horse with rich trappings (which represent the horses for which Gilzanu was famous). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side C: Two men bring two-humped (Bactrian) camels from Gilzanu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

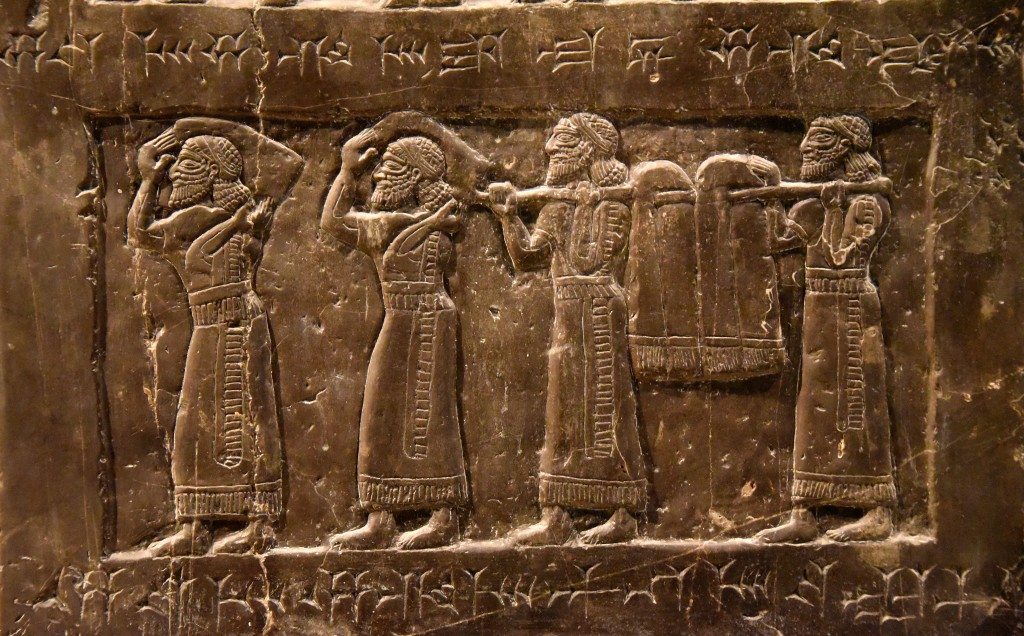

Side C: Two men bring two-humped (Bactrian) camels from Gilzanu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side D: There are five tribute-bearers bringing silver, gold, tin, bronze cauldrons (and) the “staffs of the king’s hand” from Gilzanu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: There are five tribute-bearers bringing silver, gold, tin, bronze cauldrons (and) the “staffs of the king’s hand” from Gilzanu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.Scene 2: King Shalmaneser III receives tribute from Iaua (Jehu) of the House of Omri (ancient Israel): Shalmaneser says that “I received tribute from Iaua, son of Omri. Notice that one can see silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden tureen, golden pails, tin, the staffs ‘of the king’s hand’ and a spear.”

Side A: King Shalmaneser III stands beneath a parasol (held by an attendant) and receives tribute from Iaua of the House of Omri (in the year 841 BCE). This is King Jehu of Israel, who appears in the Bible (2 Kings 9-10). An attendant faces the king and holds a fly whisk. There are two guards at both sides. Symbols of gods Assur (left) and Ishtar (right) are seen before the king’s head. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side A: King Shalmaneser III stands beneath a parasol (held by an attendant) and receives tribute from Iaua of the House of Omri (in the year 841 BCE). This is King Jehu of Israel, who appears in the Bible (2 Kings 9-10). An attendant faces the king and holds a fly whisk. There are two guards at both sides. Symbols of gods Assur (left) and Ishtar (right) are seen before the king’s head. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side B: There are two Assyrian officials and three tribute-bearers from Israel; they hold “silver, gold … gold vessels … tin …” Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: There are two Assyrian officials and three tribute-bearers from Israel; they hold “silver, gold … gold vessels … tin …” Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: There are five more tribute-bearers from Israel bringing a gold bowl, a golden tureen, gold vessels, gold pails, tin, the “staffs of the king’s hand” (and) spears. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: There are five more tribute-bearers from Israel bringing a gold bowl, a golden tureen, gold vessels, gold pails, tin, the “staffs of the king’s hand” (and) spears. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side D: There are five tribute-bearers from Israel holding silver, gold, a gold bowl, a gold tureen, gold vessels, gold pails (and) tin. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: There are five tribute-bearers from Israel holding silver, gold, a gold bowl, a gold tureen, gold vessels, gold pails (and) tin. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.Scene 3: A parade of exotic animals brought from the land of Musri (probably Egypt); there is no depiction of the subdued king or ruler, whose name was not mentioned). Shalmaneser says that “I received tribute from Muṣri, two-humped camels, a water buffalo, a rhinoceros, an antelope, female elephants, female monkeys and apes.”

Side A: Attendants bring tribute from Musri in the form of two-humped camels. Unlike the upper registers on side A, neither Shalmaneser III nor the subdued ruler appear. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side A: Attendants bring tribute from Musri in the form of two-humped camels. Unlike the upper registers on side A, neither Shalmaneser III nor the subdued ruler appear. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side B: This register depicts exotic animals from Musri in the form of a river-ox, a rhinoceros (and) an antelope. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: This register depicts exotic animals from Musri in the form of a river-ox, a rhinoceros (and) an antelope. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side C: There are female elephants, female monkeys (and) apes. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: There are female elephants, female monkeys (and) apes. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side D: There are more monkeys with their keepers. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: There are more monkeys with their keepers. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.Scene 4; Marduk-apla-usur the Suhean (from the mid-Euphrates area of modern-day Syria and Iraq), sends animals and other tribute to the Shalmaneser III (the former was not depicted on the Obelisk). Shalmaneser says that “I received tribute from Marduk-apla-usur, the Suhean, silver, gold, pails, ivory, spears, byssus, garments with multi-coloured trim and linen.”

Side A: There are two lions and a stag from Marduk-apla-usur the Suhean (probably for the royal hunting park). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side A: There are two lions and a stag from Marduk-apla-usur the Suhean (probably for the royal hunting park). Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side B: There are four tribute-bearers from Suhu carrying “silver, gold… byssus, garments with multi-colored trim and linen.” Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: There are four tribute-bearers from Suhu carrying “silver, gold… byssus, garments with multi-colored trim and linen.” Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.![Side C: We can see 5 tribute-bearers bringing "silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears" from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.](http://etc.ancient.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/OSA_7096-1024x587.jpg) Side C: We can see five tribute-bearers bringing “silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears” from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: We can see five tribute-bearers bringing “silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears” from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.![Side D: Four tribute-bearers were depicted carrying "silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears" from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.](http://etc.ancient.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/OSA_7083-1024x720.jpg) Side D: Four tribute-bearers were depicted carrying “silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears” from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: Four tribute-bearers were depicted carrying “silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears” from the land of Suhu. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.![Side A: Tribute from Qarparunda the Patinean in the form of silver, gold, tin, âfastâ bronze ... ivory [tusks] (and) ebony. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III.](http://etc.ancient.eu/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/OSA_7072-1024x588.jpg) Side A: Tribute from Qarparunda the Patinean in the form of silver, gold, tin, “fast” bronze … ivory [tusks] (and) ebony. Qarparunda was not depicted on the scene. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side A: Tribute from Qarparunda the Patinean in the form of silver, gold, tin, “fast” bronze … ivory [tusks] (and) ebony. Qarparunda was not depicted on the scene. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side B: There are two Assyrian officials introducing three tribute-bearers from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side B: There are two Assyrian officials introducing three tribute-bearers from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side C: We can recognize five tribute-bearers bringing “gold and silver” vessels and a “bronze cauldron” from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side C: We can recognize five tribute-bearers bringing “gold and silver” vessels and a “bronze cauldron” from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin. Side D: Four tribute-bearers were depicted holding “gold and silver” vessels and a “bronze cauldron,” which were brought from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.

Side D: Four tribute-bearers were depicted holding “gold and silver” vessels and a “bronze cauldron,” which were brought from the land of Patina. Photo © Osama S. M. Amin.The following were used to draft this article:

- Images from a personal visit to the British Museum and the British Museum website description of the Obelisk.

- Jonathan Taylor, ‘The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III’, Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org.

- The Bible in the British Museum.

- P. Kyle McCarter’s article on Yaw, Son of Omri, which is accessible through JSTOR.

I hope I have been successful in conveying the images of this obelisk to you! As an Iraqi citizen, I would like to sincerely thank all of those who were involved in the excavation, transportation, preservation, protection, and the display of this Black Obelisk. This history belongs to the whole world and humanity, not only to Iraq. Viva Mesopotamia, the Cradle of Civilization!

http://etc.ancient.eu/photos/black-obelisk-of-shalmaneser-iii-british-museum/

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III is a stone monument that celebrates thirty-one successful years of military campaigns by king Shalmaneser III and his chief minister, Dayyan-Aššur. It was erected in 825 BC in a courtyard of a central building in Kalhu. Carved into its four faces are scenes showing king Shalmaneser III receiving tribute TT from vassal TT subjects across the Assyrian empire. After its rediscovery in 1846, the Obelisk became a museum object in London, and gained fame for depicting an Israelite king mentioned in the Christian Bible.

Image 1: The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III, carved with scenes celebrating the achievements of the Assyrian king and his chief minister; 825 BC. British Museum, BM 118885. View information and large image on the British Museum's website. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

The Black Obelisk (Image 1) is a monument (or stela TT ) carved from black limestone, which stands just under two metres high. It has four sides, each 45 cm wide. The top is stepped as though shaped like a ziggurat TT with four sloping stages. The significance of this shape is unknown, but it does seem to be standard for Assyrian obelisks TT . The White Obelisk of Assurnasirpal I found by Hormuzd Rassam at Nineveh shares this shape.

The function of obelisks is not certain, but judging from its four faces, and its findspot TT , it is reasonable to conclude that it was designed for public display. The Black Obelisk (Image 1) was erected in a courtyard outside a large building in the centre of Kalhu, now known as the "Central Building", which is thought to be one of the temples listed in Assurnasirpal II's Standard Inscription (1). At the time of the stela's TT erection, Kalhu was the capital of an Assyrian empire torn apart by civil war, so maybe it was intended to remind the king's retinue of the extent of his authority and rule.

Acts of tribute to the Assyrian king

Five scenes wrap around the Obelisk. They each depict tribute TT exacted from a vassal TT , who is named in a cuneiform TT caption. The tribute includes exotic animals such as camels, monkeys, an elephant and a rhinoceros. Assyrian kings often collected exotic animals and plants as an expression of their power. It is thought that the vassals shown here are chosen to demonstrate the geographical bounds of the empire, from east to west. The Black Obelisk also has a longer inscription, which tells of Shalmaneser's achievements in more detail (2).

The five tribute scenes as they wrap around the monument are as follows, from top to bottom:

Scene 1: Shalmaneser receives tribute from Sua of Gilzanu

Detail from Scene 1, Side A of the Black Obelisk. Richly dressed king Shalmaneser III holds a bow and stands next to an emblem of the sun god, Šamaš PGP . At Shalmaneser's feet (see large image), a vassal subject named Sua the Gilzanean PGP crouches in a pose of tribute. View high-quality large image of Scene 1 (1.7 MB). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Side A: Shalmaneser, holding a bow, receives "tribute from Sua the Gilzanean". (This event is recorded in Shalmaneser's annals (3)). He faces his field marshal and another official.

- Side B: Two Assyrian officials, a foreign groom and a horse with rich trappings, representing the horses for which Gilzanu PGP was famous.

- Side C: [Indian] Two attendants bring "two-humped (Bactrian) camels" from Gilzanu.

- Side D: Five tribute-bearers with "silver, gold, tin, bronze cauldrons (and) the 'staffs of the king's hand'" from Gilzanu.

Scene 2: Shalmaneser receives tribute from Iaua (Jehu) of the House of Omri (ancient northern Israel)

Detail from Scene 2, Side A of the Black Obelisk. A vassal subject named Iaua PGP (known in the Bible as king Jehu of Israel PGP ) crouches in a pose of tribute at king Shalmaneser III's feet. View high-quality large image of Scene 2 (1.7 MB). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

"I received tribute from Iaua, son of Omri: silver, gold, a golden bowl, a golden tureen, golden pails, tin, the staffs 'of the king's hand' and a spear."

- Side A: Shalmaneser, beneath a parasol TT , accepts the "tribute of Iaua PGP of the House of Omri" in 841 BC. This is king Jehu of Israel PGP , who appears in the Bible (2 Kings 9-10).

- Side B: Two Assyrian officials and three tribute-bearers from Israel with "silver, gold ... gold vessels ... tin ...".

- Side C: Five more tribute-bearers from Israel with "a gold bowl, a golden tureen, gold vessels, gold pails, tin, the 'staffs of the king's hand' (and) spears".

- Side D: Five tribute-bearers from Israel with "silver, gold, a gold bowl, a gold tureen, gold vessels, gold pails (and) tin".

Scene 3: A parade of exotic animals from Muṣri

Detail from Scene 3, Side D of the Black Obelisk. A monkey or ape from Muṣri PGP ? This strange-looking humanoid figure, chained by its leg and restrained by a keeper, is described as one of the "female monkeys and apes" brought as tribute to Shalmaneser from the country of Muṣri. View high-quality large image of Scene 3 (1.6 MB). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

"I received tribute from Muṣri: two-humped camels, a water buffalo TT , a rhinoceros, an antelope, female elephants, female monkeys and apes."

- Side A: Attendants bring "tribute from Muṣri: two-humped camels". Muṣri, meaning 'borderland', probably refers to a country far to the east.

- Side B: Exotic animals from Muṣri: "a river-ox [water-buffalo], an [Indian] rhinoceros (and) an antelope". The sculptor seems never to have seen a rhinoceros.

- Side C: "Female [Indian] elephants, female monkeys (and) apes" from Muṣri.

- Side D: More "monkeys" and their keepers from Muṣri. The way the monkeys are carved suggests that the sculptor had not seen them himself. This may not be the case, however. Monkeys were not new sights for the Assyrian court at this time.

Scene 4: Marduk-apla-uṣur the Suhean sends animals and other tribute

Detail from Scene 4, Side A of the Black Obelisk. A roaring big cat, given as tribute to Shalmaneser III by Marduk-apla-uṣur PGP from Suhu PGP (on the Middle Euphrates). View high-quality large image of Scene 4 (1.7 MB). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Side A: Lions and a stag from "Marduk-apla-uṣur PGP the Suhean PGP ", probably for the royal hunting park.

- Side B: Four tribute-bearers from Suhu with "silver, gold... byssus, garments with multi-coloured trim and linen [garments]".

- Side C: Five tribute-bearers with "silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears" from Suhu.

- Side D: Four tribute-bearers with "silver, gold, gold pails, ivory [tusks] (and) spears" from Suhu.

Scene 5: Qarparunda the Patinean sends precious metals, ivory and ebony

Detail from Scene 5, Side A of the Black Obelisk. A bearded man from Patina PGP carries a large basket or bowl on his head, as tribute for king Shalmaneser III. View high-quality large image of Scene 5 (1.8 MB). © The Trustees of the British Museum.

- Side A: "Tribute from Qarparunda the Patinean: silver, gold, tin, 'fast' bronze ... ivory [tusks] (and) ebony".

- Side B: Two Assyrian officials introduce three tribute-bearers from Patina PGP .

- Side C: Five tribute-bearers with "gold and silver" vessels and a "bronze cauldron" from Patina.

- Side D: Four tribute-bearers with "gold and silver" vessels and a "bronze cauldron" from Patina.

Content last modified: 31 Dec 2015.

References

- Oates, D. and J. Oates, 2001. Nimrud, An Assyrian Imperial City Revealed, London: British School of Archaeology in Iraq ( free PDF from BISI, 128 MB), pp. 71-73. (Find in text ^)

- Grayson, A.K., 1996. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC II (858-745 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Periods. Volume 3), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 62-71: A.0.102.14 (with detailed bibliography), pp.148-51: A.0.102.87-91. (Find in text ^)

- Grayson, A.K., 1996. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC II (858-745 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Periods. Volume 3), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 32-41: A.0.102.6, I 41. (Find in text ^)

Jonathan Taylor

Anzu the monstrous lion-eagle

The Anzu bird, half-lion, half-eagle, had been a mainstay of cuneiform TT culture from at least the third millennium BC. He appears in Sumerian literary works as a wild creature of the mountains. He can also be tamed by the gods, as depicted in monumental sculpture. In 9th-century Kalhu, he was portrayed doing battle with the warrior god Ninurta, at an entrance to the most important shrine of the royal citadel TT . Layard PGP discovered this sculpture in the mid-19th century, and shipped it to the British Museum TT . For generations this unnamed "dragon" or "demon" TT captivated the public imagination in many different ways. However, it took over half a century to rediscover Anzu's true identity.

Image 1: In Layard's PGP glossy publication of sculptures from Nimrud and Nineveh PGP he simply labelled the relief TT later known as Anzu and Ninurta as "Bas-reliefs from the entrance to a small temple (Nimroud)" (1). The engraving was made by the eminent Ludwig Gruner PGP . View large version (277 KB).

Fight or flight: Anzu in Ninurta's temple

Image 2: Solomon Malan PGP 's sketch, made on the spot at Nimrud in 1950, shows the northern member of the pair of bas-reliefs TT coming out of the ground (2). The southern one, which originally stood opposite, has already been removed. The tunnel to the left shows how Layard's men dug by following the temple walls. View large version (236 KB).

There were two ways into the shrine of the mighty god Ninurta, nestled into the southeast corner of the ziggurat at Kalhu. The most direct entrance was flanked by enormous stone human-headed lions. When the doors between them were opened, priests and the privileged few could gaze directly through an ante-chamber to the statue of the deity himself (Room A on the plan). Alternatively, they could enter and exit through a doorway just to the north of the lion gateway, and then turn back south into the antechamber or the shrine (Room B). Protective male figures holding branches were positioned on the courtyard side of the doorway, fish-cloaked figures on the interior side. A huge sculpture of king Assurnasirpal PGP stood just to the right.

The doorway to Room B was lined on both sides with mirror-image depictions of the same extraordinary scene (Image 1). A towering male figure in a long robe bears down on a monstrous creature, half lion and half eagle, who turns back to him open mouthed, claws out. The bearded man's horned helmet and double wings mark him out as a god. His muscles bulge and he is laden with weapons. A sickle TT and a sheathed sword hang from his body, while he clutches forked bolts of lightning in each hand. This can only be the culminating episode in The Epic of Anzu, where Ninurta cunningly defeats this demonic TT force of chaos, and reclaims the Tablet of Destinies TT for the gods.

The image of Ninurta chasing Anzu out of his temple powerfully marries the militaristic ideals of Assyrian kingship with the importance of scholarly learning. One the one hand, Ninurta must use intelligence as well as brute force to defeat the wicked Anzu. On the other, his quest is to recover the Tablet of Destinies, which records the gods' decisions about Assyria's future. Court scholarsadvised the Assyrian king on his military decision-making by interrogating the gods about their intentions, through various forms of divination TT . Assyria went to war only with the gods' blessing, and with victory assured in the Tablet of Destinies. Assyrian royal inscriptions increasingly acknowledged the role of scholarly divination in predicting divine support and garnering military success.

Assurnasirpal II commissioned the building of Ninurta's shrine early in the ninth century BC. When the royal court moved to Dur-Šarruken PGP , and then to Nineveh PGP , in the late eighth and early seventh centuries BC, Ninurta was already losing royal patronage in favour of Nabu PGP . Now that the empire had stabilised, learnedness was more fashionable than militarism. Nevertheless, Ninurta's temple survived nearly 200 years of royal neglect, and the twin monuments to his victory over Anzu remained standing, right until Kalhu's temples were pillaged by invaders at the end of empire in 612 BC (4).

A monster unearthed: but which one?

Image 4: Well into the 20th century, the British Museum's Nimroud Gallery displayed Ninurta and Anzu as Marduk PGP and Tiamat, adjacent to a restoration of the fish-cloaked figure that had stood with it in the temple. Look closely and you will spot that it doubles as a cupboard door! Source: M0007475, Wellcome Library, London. CC BY 4.0. View large image.

Image 5: These days Anzu and Ninurta may be visited in Room 6 on the ground floor of the British Museum. They are still accompanied by their protective genie TT and the fish-cloaked figure from the northern half of the doorway. British Museum ME 124571. View the British Museum's catalogue entry for this object.

Anzu came to light again only in June 1850. A visitor to Layard's excavations at Nimrud, the Reverend Solomon Malan PGP , vividly sketched the northern half of the pair of bas-reliefs, still in its earthen matrix and surrounded by discarded rubble (Image 2). A weary local workman sits propped up in its shade (5). Malan's watercolour is the only surviving record of this object, as Layard decided to keep only the southern member of the pair (Image 3).

The sculpture arrived at the British Museum, as part of much larger shipment of Nimrud artefacts, in 1851. It was set up in the so-called Nimroud Gallery on the ground floor, in between the bas-reliefs of protective genies that had flanked it in antiquity (Image 4, Image 5). But who these two powerful, well-matched figures were, no-one yet knew. The inscription running across the front was very badly worn, and the one on the back could not yet be deciphered. In his account of the excavations, Layard rightly inferred that the image "appears to represent the bad spirit driven out by a good deity; a fit subject for the entrance of a temple dedicated to the god of war" (6). That was as much as anyone could say for now.

Gradually over the next few decades, cuneiform script began to make more sense. In 1876, a full quarter of a century after the arrival of the sculpture at the British Museum, the first clues as to Anzu's identity began to appear. Museum assistant George Smith PGP published a book of translated Assyrian and Babylonian PGP myths that aimed to relate this still difficult material to the much more familiar world of the Old Testament (7). The climax of the so-called "Chaldean account of Genesis" (now better known as the Standard Babylonian TT Epic of Creation TT , or Enūma Eliš) featured a cosmic battle very like that shown in the bas-relief from Nimrud. The warrior god Bel PGP or Merodach — now known as Marduk PGP — defeats the dragon Tiamat PGP with a sword and bow.

Smith confidently identified the hitherto mysterious monument from Nimrud as the "fight between Merodach (Bel) and the Dragon" (8) and even used it on the front cover of the book. He undoubtedly knew that Tiamat was female: "Tiamat opened her mouth to swallow him", he translated (9). Yet Anzu's snake-headed penis was clearly visible in the line drawing he used in the book, though was removed for the sake of Victorian modesty on the cover itself. At almost exactly the same time, Assyriological TT dilettante Henry Fox Talbot PGP made almost exactly the same argument, explicitly bringing the apocryphal Old Testament book "Bel and the Dragon" into the argument (10) (11).

It was to be several more decades before the three monsters — Anzu, Tiamat, and Marduk's mušhuššu-dragon — were disentangled. Meanwhile, the British Museum's curators started to label the Nimrud scuplture as "the conflict between the god Marduk or Bêl and the monster Tiâmat", and continued to do so until at least 1908 (12).

From Zu to Anzu

Image 6: For propriety's sake, Anzu lost his snake-headed penis on the cover of George Smith's PGP 1876 book of translations (13). Much confusion resulted, for many years. View large version of image (276 KB).

It did not take long to decipher the inscriptions on the slabs from the temple, establishing it as property of the god "Ninib". British Museum Assyriologist TT Leonard King PGP published the first systematic translation of the temple texts in 1902 (14) (15). W F Albright correctly read the name "Ninib" as Ninurta in 1915 (16). However, there was nothing in these inscriptions to identify the protagonists of the battle scene as Ninurta and Anzu. That was a long time coming.

Another of the narratives in Smith's anthology was the very fragmentary work that he named "The Sin of the God Zu" (17). At that point, in 1876, it was very hard to interpret its contents, except that "Zu" ran away after committing some crime against the gods, who then discussed how to react. As Smith noted, other inscriptions suggested that Zu "was in the likeness of a bird of prey" (18). Gradually, as more pieces of clay tablets TT were discovered, the composition we now call The Epic of Anzu began to take shape. But the process was very gradual indeed. In the late 1940s the Manchester Assyriologist Thomas Fish was still struggling with what the "Zu bird" must have looked like, and which god had defeated him, Marduk or Ninurta (19).

The monster's identity as "Anzu" rather than "the god Zu" gradually gained acceptance over the 1960s and 70s, as it became clear that the first cuneiform sign of the name must be the syllable an and not the (visually identical) divine marker DINGIR (20) (21). Ilse Fuhr-Jaeppelt's diachronic TT analysis of Anzu's iconography TT over the third to first millennium BC, together with Blahoslav Hruška's study and full critical edition of The Epic of Anzu finally put Anzu's identity beyond doubt, a full 125 years after he emerged from the earth of Nimrud (22) (23). In the meantime, however, Anzu's image had taken on a life of its own, far beyond the confines of Assyriology.

Anzu in advertising

Image 7: Anzu starring in a pharmaceuticals advert in Wellcome's Medical Diary and Visting List(1915). In the early twentieth century, pharmaceuticals firm Burroughs Wellcome and Company distributed around 35,000 of these pocket-sized diaries annually to doctors as a marketing tool.Source: private collection. The Nimrud Project CC-BY-SA 3.0 View large image (763 KB).

In the early twentieth century, Anzu featured in an advert by pharmaceuticals firm Burroughs Wellcome & Company (BW&C) designed to defend its brands of medicines against commercial rivals (Image 7). Headed by businessman Henry Wellcome, BW&C secured financial success in the early twentieth century by selling compressed forms of foodstuffs and medicines, trade-marked under the brand-name 'Tabloid' (but which are now better known as tablets). The company fiercely pursued any copyright infringement, through advertising campaigns and by threatening perpetrators with legal action (24) (25).

As part of their brand protection campaign, BW&C targeted chemists and druggists who passed off cheap home-made medicines as BW&C branded versions, pocketing the profits. The company fought a decade of trade warfare with retail chemists over issues of drug substitution around 1900. (26). They pitched adverts to doctors warning them of the dangers of imitation medicines, and the Anzu advert is once such example. Its sharp wording pushed doctors to write out BW&C trade-marked names in their prescriptions, which forced chemists to dispense branded medicines and not cheaper substitutes. According to BW&C's advert, abbreviating the 'Tabloid' brand-name was actively "dangerous" (Image 7), as it let unscrupulous chemists use dubious ingredients and endanger patients.

The Anzu advert appears in the 1915 edition of Wellcome's Medical Diary and Visiting List, a promotional tool distributed free to doctors (27). These appointments diaries came complete with reference information, a handy pencil, and copious BW&C advertisements. Each diary between 1906 and 1940 featured a different ancient civilisation, catering to a rising interest in history of medicine among the medical profession, and the 1915 diary was entirely Assyrian themed. A complete set of the diaries is now held in the Wellcome Library in London.

Tablet stealers

But why use an image of Anzu to represent cut-throat commercial practices? BW&C likely understood that its well-educated audience of doctors would be familiar with the ancient mythologies depicted in their diaries. Each year they chose an appropriate mythological character to accompany their 'Dangerous Abbreviation' advert, assembling a motley crew of 'baddies' to symbolize commercial evil. Anzu's appearance in 1915 was preceded by the fearsome Gorgon Medusa from ancient Greek legend (1911), whose stare turned men to stone, and the Maori marakihau (1910), a deep-water monster that devoured passing sailors (28) (29) (30).

Some of these characters were famously recognisable, others playfully obscure. And if the company was inviting medical doctors to play 'guess the monster', Anzu was likely one of the more familiar creatures, even if his name was not yet known. His image was famous from Layard's and Smith's books where he was known to represent dark malevolence, even though his exact identity as a bird-monster or dragon was uncertain. The pharmaceuticals company played on this familiarity, visualizing brand infringement practices as an evil creature that needed vanquishing.

Doctors who were familiar with the Assyrian battle scene image may also have noticed what was missing in in the BW&C version: the force of good - the vanquishing hero. In the absence of the champion, was the audience invited to infer that the hero was company proprietor, Henry Wellcome, himself? Certainly, the implication was that in the fight between good and evil, BW&C was the force of good. And Anzu, originally stealer of the Tablet of Destinies, now represented 'tablet stealers' of a pharmaceutical kind.

31 Dec 2015 References

- Layard, A.H., 1849-1853. The Monuments of Nineveh: From Drawings Made on the Spot, vols. I–II, London: John Murray (free online edition of vol. 1 and vol. 2), pp. vol II, plate 5. (Find in text ^)

- Gadd, C.J., 1938. "A visiting artist at Nineveh in 1850", Iraq 5, pp. 118-122 and plates XI-XX (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. plate XV. (Find in text ^)

- Layard, A.H., 1853. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, London: John Murray (free online edition via The Internet Archive), p. 302. (Find in text ^)

- Reade, J.E., 2002. "The ziggurrat and temples of Nimrud", Iraq 64, pp. 135-216 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), p. 201. (Find in text ^)

- Gadd, C.J., 1938. "A visiting artist at Nineveh in 1850", Iraq 5, pp. 118-122 and plates XI-XX (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers), pp. pl. XV. (Find in text ^)

- Layard, A.H., 1853. Discoveries in the Ruins of Nineveh and Babylon, London: John Murray (free online edition via The Internet Archive), p. 301. (Find in text ^)

- Smith, G., 1876. The Chaldean Account of Genesis, London: Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington (free online edition at The Internet Archive). (Find in text ^)

- Smith, G., 1876. The Chaldean Account of Genesis, London: Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington (free online edition at The Internet Archive), p. 62. (Find in text ^)

- Smith, G., 1876. The Chaldean Account of Genesis, London: Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington (free online edition at The Internet Archive), p. 98. (Find in text ^)

- Talbot, W.H.F, 1876. "The fight between Bel and the Dragon, and the flaming sword which turned every which way", Transactions of the Society of Biblical Archaeology 5: 1-21. (Find in text ^)

- Robson, E., 2013. "Bel and the dragons: deciphering cuneiform after decipherment", in M. Brusius, K. Dean and C. Ramalingam (eds.), William Henry Fox Talbot: Beyond Photography, New Haven: Yale University Press, pp. 193-218. (Find in text ^)

- British Museum, 1908. A Guide to the Babylonian and Assyrian Antiquities, 2nd edition, revised and enlarged. London: printed by order of the Trustees, p. 24. (Find in text ^)

- Smith, G., 1876. The Chaldean Account of Genesis, London: Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington (free online edition at The Internet Archive). (Find in text ^)

- Budge, E.A.W. and L.W. King, 1902. Annals of the Kings of Assyria: The Cuneiform Text with Translations, Transliterations, etc. from the Original Documents in the British Museum, Vol. 1, London: printed by order of the Trustees, pp. . (Find in text ^)

- Grayson, A.K., 1996. Assyrian Rulers of the Early First Millennium BC II (858-745 BC) (Royal Inscriptions of Mesopotamia. Assyrian Periods. Volume 3), Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. nos.A.0.101.3, 5-7, 31. (Find in text ^)

- Albright, W.F., 1915. "Ninib-Ninurta", Journal of the American Oriental Society 38: 197-201 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers). (Find in text ^)

- Smith, G., 1876. The Chaldean Account of Genesis, London: Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington (free online edition at The Internet Archive), pp. 113-122. (Find in text ^)

- Smith, G., 1876. The Chaldean Account of Genesis, London: Low, Marston, Searle and Rivington (free online edition at The Internet Archive), p. 119. (Find in text ^)

- Fish, T., 1948. "The Zu bird", Bulletin of the John Rylands Library 31: 162-171. (Free PDF available via University of Manchester Library). (Find in text ^)

- Landsberger, B., 1961. "Einige unerkannt gebliebene oder verkannte Nomina des Akkadischen," Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 57: 1-23. (Find in text ^)

- Civil, M., 1972. "The Anzu-bird and scribal whimsies", Journal of the American Oriental Society 92: 271 (PDF available via JSTOR for subscribers). (Find in text ^)

- Fuhr-Jaeppelt, I., 1972. Materialien zur Ikonographie des Löwenadlers Anzu-Imdugud. Munich. (Find in text ^)

- Hruška, B., 1975. Der Mythenadler Anzu in Literatur und Vorstellung des alten Mesopotamien, Budapest: Eötvös-Lorand University. (Find in text ^)

- Larson, F., 2009. An Infinity of Things. How Sir Henry Wellcome Collected the World, London, New York, Toronto: Oxford University Press, pp. 12-13. (Find in text ^)

- Church, R., and E. M. Tansey (2007). Burroughs Wellcome & Co. Knowledge, Trust, Profit and the Transformation of the British Pharmaceutical Industry 1880-1940. Lancaster: Crucible Books, pp. 131–139, 284–285. (Find in text ^)

- Church, R., and E. M. Tansey (2007). Burroughs Wellcome & Co. Knowledge, Trust, Profit and the Transformation of the British Pharmaceutical Industry 1880-1940. Lancaster: Crucible Books, pp. 130-145. (Find in text ^)

- Wellcome's Medical Diary and Visiting List (1915). London: Burroughs Wellcome & Co., WF/M/PB/003/28, Wellcome Foundation Archives, Wellcome Library, London. (Find in text ^)

- Wellcome's Medical Diary and Visiting List (1911). London: Burroughs Wellcome & Co., WF/M/PB/003/24, Wellcome Foundation Archives, Wellcome Library, London. (Find in text ^)

- Wellcome's Medical Diary and Visiting List (1910). London: Burroughs Wellcome & Co., WF/M/PB/003/23, Wellcome Foundation Archives, Wellcome Library, London. (Find in text ^)

- Horry, R. A., 2013. "Transitions and Transformations in Assyriology, c.1880-1913: Artefacts, Academics and Museums", PhD dissertation, University of Cambridge, pp. 96-100, 110-113. (Find in text ^)

Ruth A. Horry & Eleanor Robson

Ruth A. Horry & Eleanor Robson, 'Anzu the monstrous lion-eagle', Nimrud: Materialities of Assyrian Knowledge Production, The Nimrud Project at Oracc.org, 2015 [http://oracc.museum.upenn.edu/nimrud/livesofobjects/anzu/]

Three Obelisks in the British Museum

| 1&2. | Pharaoh: | Nectanebo II (Late Period, The 30th dynasty, Reigned 4 Century BC) |

| Measurement: | 2.74 meters high | |

| 3. | Pharaoh: | Hatshepsut (New Kingdom 18th Dynasty, Reigned 15 Century BC) |

| Measurement: | 1.65 meters high |

The Museum is in the center of London, but no underground station close to the museum. Although there are 4 stations: Russell Square, Goodge Street, Tottenham Court Road, and Holborn, but I would recommend Tottenham Court Road (Northern Line, Central Line), or Holborn (Central Line, Piccadilly Line) for the main entrance of the museum, about 300 meters by walk from the stations.

About the Obelisk:

Three (3) obelisks of Ancient Egypt and two (2) obelisks of Ancient Assyria are exhibited in this Museum.

Among three (3) of Ancient Egypt, two (2) are in the Great Court, along the wall of both side, that were made by King Nectanebo II. Another one (1) is in Room 65 (Sudan, Egypt and Nubia) on the Upper Level, that was made by Queen Hatshepsut.

1&2. Nectanebo II Obelisks (Excluded from the excerpts)

May 6, 2015 by Hiroyuki Nagase

[Appendix] Assyrian ObeliskAmong five (5) obelisks in the British Museum, this would be the most wellknown, as a "Black Obelisk". Wikipedia has a page for this Black Obelisk.

This was originally erected in 825 BC by Shalmaneser III, a king of Assyria [reigned 858-824 BC], and discovered in 1846 from underground of Nimrud (ancient Kalhu, Northern Iraq). This is 1.98 meters high, and has cuneiform inscriptions and the relief illustrated an image of Jehu, King of Israel who is contributing to King Shalmaneser, and the contributed animals.

Next to the "Black Obelisk", "White Obelisk" is also exhibited. This was discovered in 1853, and is 2.84 meters high. According to the Museum, the inscription may not have completed, and most are unreadable. The name of Ashurnasirpal is inscribed, but the researchers are still discussing whether Ashurnasirpal I [reigned 1050-1031 BC] or Ashurnasirpal II [reigned 883-859 BC].

Reference: the Explanation about Black Obelisk by the British Museum

August 2, 2014 by Hiroyuki Nagase

Reference: the Explanation about White Obelisk by the British MuseumObelisks are not on display

The British Museum web site has a search service of the collections database. Checked the search results, it was found that there are following obelisks which are not on display.

There are such as a priest's obelisk in 4th century, and fragment of "Cleopatra's Needle".

| Object ID 111119 Museum number EA495 | Limestone obelisk inscribed with name of Iry, Lector-priest in Heliopolis. |

| Object ID 120829 Museum number EA693 | Sandstone obelisk; Hieroglyphic symbols on three sides; top chipped. |

| Object ID 120152 Museum number EA1205 | Black granite obelisk. |

| Object ID 125238 Museum number EA177 | Limestone truncated obelisk; two columns of incised Hieroglyphic text on each side, |

| Object ID 3358786 Museum number EA943 | Fragment of red granite from the obelisk of Tuthmosis III, known as "Cleopatra's Needle". |

| Object ID 177341 Museum number EA1727 | Pyramidion and upper part of shaft of a small obelisk, made of red granite, |

| Object ID 152637 Museum number EA65339 | Upper part of a red granite obelisk; the four sides are decorated with representations of Sety I(?). |

| Object ID 124686 Museum number EA1635 | Sandstone obelisk; decorative cross on the front in low relief beneath a panel of incised Coptic text. |

| Object ID 122801 Museum number EA1512 | Top of a limestone obelisk(?); Hieroglyphic text and representations of composite deities on each side. |

http://www.obelisks.org/en/british_museum.htm

14. Black obelisk of Shalmaneser III, 825BC, Nimrod (northern Iraq), 198cm high. Here is a close up of the third panel showing the tribute of the country of Musri (probably Egypt), consisting entirely of animals led or driven by attendants dressed in knee-length garments.

14. Black obelisk of Shalmaneser III, 825BC, Nimrod (northern Iraq), 198cm high. Here is a close up of the third panel showing the tribute of the country of Musri (probably Egypt), consisting entirely of animals led or driven by attendants dressed in knee-length garments.

Black obelisk of Shalmaneser III At British Museum depicts King Jehu the King of Israel bowing before the Assyrian king in tribute, read 2Kings 9-10

Attendants bring tribute from Musri with two-humped camels. Musri, meaning a borderland, probably refers to a country in eastern Iran or in Egypt.

From Nimrud, (ancient Kalhu), near the building of Shalmaneser, neo-Assyrian era, 827 BCE, Mesopotamia, northern Iraq. (The British Museum).

https://www.ancient.eu/image/2487/the-black-obelisk-of-shalmaneser-iii-side-a-3rd-re/

This obelisk was erected as a public monument in 825 BCE at a time of civil war. The relief sculptures glorify the achievements of King Shalmaneser III and his commander-in-chief . It lists their military campaigns of 31 years and the tribute they exacted from their neighbors. It is the most complete Assyrian obelisk yet discovered, and it is historically significant because it is thought to display the earliest ancient depiction of a biblical figure - Jehu King of Israel. Reign of Shalmaneser III, 858-824 BCE, neo-Assyrian era, from Nimrud (ancient Kalhu), northern Iraq, Mesopotamia, the British Museum, London.

https://www.ancient.eu/image/2289/the-black-obelisk-of-king-shalmaneser-iii/

The Black Obelisk of Shalmaneser III was made in the 9th century BC in ancient Assyria. It is about six and a half feet in height and is made of fine grained black limestone. The cuneiform text reads, "Tribute of Jehu, son of Omri...." Both Jehu and Omri were Israelite kings who are referred to in the Bible (cf. 1 & 2 Kings). A close-up photo showing an Israelite, possibly Jehu, bowing to the king of Assyria.

Jehu, the King of Israel 841-814 BC Paying tribute to Assyrian King Shalmanasser III Black Obelisk British museum

Jehu, the King of Israel 841-814 BC Paying tribute to Assyrian King Shalmanasser III Black Obelisk British museum

Image id:

00509530001

Object type:

obelisk

Object title:

The Black Obelisk

Findspot:

Nimrud

Materials:

limestone

Period / culture:

Production date:

825BC

Subject:

king/queen, war, mammal, hunting/shooting

Department:

Middle East

Object reference numbers:

https://www.bmimages.com/preview.asp?image=00509530001&itemw=4&itemf=0001&itemstep=1&itemx=443![White Obelisk, top registers of Sides D and A (© Trustees of the British Museum).]() W White Obelisk, top registers of Sides D and A (© Trustees of the British Museum).

W White Obelisk, top registers of Sides D and A (© Trustees of the British Museum).

W White Obelisk, top registers of Sides D and A (© Trustees of the British Museum).

W White Obelisk, top registers of Sides D and A (© Trustees of the British Museum).