https://tinyurl.com/yy656agt

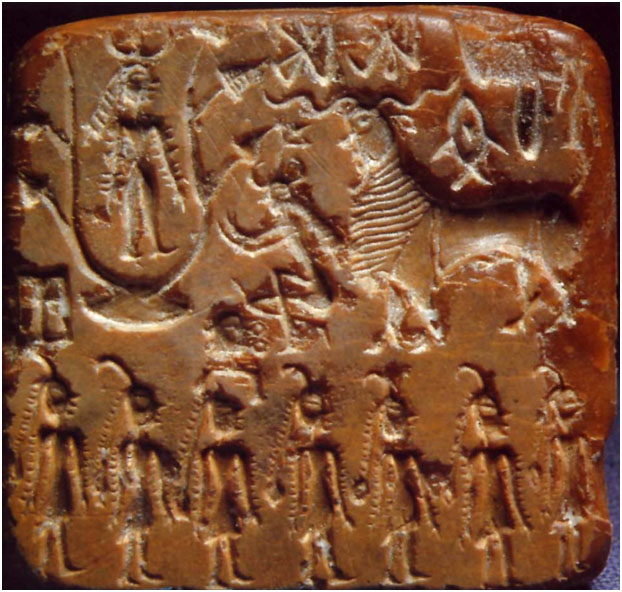

NOTE: This is an unprovenanced seal posted on a website citing an exhibition held in 2017. I have called it Mehrgarh Pasupati seal

-- and silver-capped twisted, crumpled ancient 'unicorn' horn as medhā koḍ 'iron workshop'

Silver-capped twisted, crumpled ancient 'unicorn' horn is read as mer̥ha deren'crumpled horn'.

![]() tešk loop, curve of horn.(Toda), tere 'a wave' (Kannada):Ta. tiraṅku (tiraṅki-) to be wrinkled, crumpled, dry up as dead leaves, be folded in as the fingers of a closed hand, be curled up as the hair; tirakku (tirakki-) to be crumpled, shrivel, wrinkle; tiraṅkal being strivelled, wrinkled, crumpled; tirai (-v-, -nt-) to become wrinkled as the skin by age, be wrinkled, creased as a cloth, roll as waves; (-pp-, -tt-) to roll as waves; gather up, contract, close as the mouth of a sack, plait the ends of a cloth as in dressing, tuck up as one's cloth; n. wrinkle as in the skin through age, curtain as rolled up, wave, billow, ripple; tiraiyal wrinkling; tiraivu wrinkling as by age, rolling as of waves. Ma. tira wave, billow, curtain; tiraccal wrinkles; tirekkuka to roll as waves; tirappu rolling. To. terf- (tert-) to make a loop (of cane); tešk loop, curve of horn. Ka. tere a wave, billow, curtain, cloth for concealing oneself used by huntsmen. Koḍ. (Shanmugam) tere wave, dress, screen. Tu. śerè, serè a wave, billow; serasarè, serasrè curtain, screen. Te. tera screen, curtain, wave. Br.trikking to wither up, change colour, fade. / Cf. Sgh. tiraya curtain, veil (delete from Turner, CDIAL, no. 5825); (Burrow 1967, p. 41).(DEDR 3244) Rebus reading of mer̥ha 'crumpled' is: meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Mu.); medhā 'yajna, dhanam'. meḍhi 'twist' Rupaka, 'metaphor' or rebus reading: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic languages)The horn hieroglyph: koḍ 'horn' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'. Thus, the crumpled, curved, twisted horn of the unicorn is read as medhā koḍ 'iron workshop which produces dhanam, wealth of metals'.

tešk loop, curve of horn.(Toda), tere 'a wave' (Kannada):Ta. tiraṅku (tiraṅki-) to be wrinkled, crumpled, dry up as dead leaves, be folded in as the fingers of a closed hand, be curled up as the hair; tirakku (tirakki-) to be crumpled, shrivel, wrinkle; tiraṅkal being strivelled, wrinkled, crumpled; tirai (-v-, -nt-) to become wrinkled as the skin by age, be wrinkled, creased as a cloth, roll as waves; (-pp-, -tt-) to roll as waves; gather up, contract, close as the mouth of a sack, plait the ends of a cloth as in dressing, tuck up as one's cloth; n. wrinkle as in the skin through age, curtain as rolled up, wave, billow, ripple; tiraiyal wrinkling; tiraivu wrinkling as by age, rolling as of waves. Ma. tira wave, billow, curtain; tiraccal wrinkles; tirekkuka to roll as waves; tirappu rolling. To. terf- (tert-) to make a loop (of cane); tešk loop, curve of horn. Ka. tere a wave, billow, curtain, cloth for concealing oneself used by huntsmen. Koḍ. (Shanmugam) tere wave, dress, screen. Tu. śerè, serè a wave, billow; serasarè, serasrè curtain, screen. Te. tera screen, curtain, wave. Br.trikking to wither up, change colour, fade. / Cf. Sgh. tiraya curtain, veil (delete from Turner, CDIAL, no. 5825); (Burrow 1967, p. 41).(DEDR 3244) Rebus reading of mer̥ha 'crumpled' is: meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Mu.); medhā 'yajna, dhanam'. meḍhi 'twist' Rupaka, 'metaphor' or rebus reading: meḍ 'iron' (Mu.Ho.) med 'copper' (Slavic languages)The horn hieroglyph: koḍ 'horn' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'. Thus, the crumpled, curved, twisted horn of the unicorn is read as medhā koḍ 'iron workshop which produces dhanam, wealth of metals'.

![]()

![5]()

![6]()

Remarkable Inscribed Chalcedony Ear-Lobe Weight, Mergargh, Indus Valley, c. 3000 BC, Size: 42 cm high, 5.9 cm diameter. © Oliver Hoare Ltd This 'weight' is said to have an inscription with five Indus Script alphabets. I shall be grateful for an image of the incription and the alphabets used. Thanks and regards. S.Kalyanaraman Sarasvati Research Centre

http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2017/05/04/35246334.html

NOTE: This is an unprovenanced seal posted on a website citing an exhibition held in 2017. I have called it Mehrgarh Pasupati seal

-- and silver-capped twisted, crumpled ancient 'unicorn' horn as medhā koḍ 'iron workshop'

Silver-capped twisted, crumpled ancient 'unicorn' horn is read as mer̥ha deren'crumpled horn'.

Below the platform:a pair of haystacks: mēṭa 'stack of hay' rebus: medhā 'yajna, dhanam' PLUS dula 'pair' rebus; dul 'metal casting'.Thus, wealth of metal castings

Hypertext: shoggy face with brisltles of hair on the face of the person: sodo bodo, sodro bodro adj. adv. rough, hairy, shoggy, hirsute, uneven; sodo [Persian. sodā, dealing] trade; traffic; merchandise; marketing; a bargain; the purchase or sale of goods; buying and selling; mercantile dealings (G.lex.)sodagor = a merchant, trader; sodāgor (P.B.) id. (Santali)

Face:muhã ʻ face, mouth, head, person ʼRebus:mũhã̄ 'the quantity of iron produced at one time in a native furnace' Bi. mũh ʻ opening or hole (in a stove for stoking, in a handmill for filling, in a grainstore for withdrawing) ʼ(CDIAL 10158)

Seated person in penance: kamaḍha 'penance' Rebus:kammaṭa 'mint, coiner'

Bangles on arms: karã̄ n. pl.wristlets, bangles' Rebus: khãr 'blacksmith'

Buffalo horns: rango 'water buffalo' Rebus: rango ‘pewter’. ranga, rang pewter is an alloy of tin, lead, and antimony (anjana) (Santali). Hieroglyhph: buffalo: Ku. N. rã̄go ʻ buffalo bull ʼ (or < raṅku -- ?).(CDIAL 10538, 10559) Rebus: raṅga3 n. ʻ tin ʼ lex. [Cf. nāga -- 2 , vaṅga -- 1 ] Pk. raṁga -- n. ʻ tin ʼ; P. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ pewter, tin ʼ (← H.); Ku. rāṅ ʻ tin, solder ʼ, gng. rã̄k; N. rāṅ, rāṅo ʻ tin, solder ʼ, A. B. rāṅ; Or. rāṅga ʻ tin ʼ, rāṅgā ʻ solder, spelter ʼ, Bi. Mth. rã̄gā, OAw. rāṁga; H. rã̄g f., rã̄gā m. ʻ tin, pewter ʼ; Si. ran̆ga ʻ tin ʼ.(CDIAL 10562) B. rāṅ(g)tā ʻ tinsel, copper -- foil ʼ.(CDIAL 10567)

Stars on horns: meḍha 'polar star' (Marathi). meḍ 'iron' (Ho.Mu.); medhā 'yajna, dhanam'

Twigs on hair-dress: kūdī 'bunch of twigs' (Sanskrit) rebus: kuṭhi 'smelter furnace' (Santali)

Two adoring, offering adorants with vases in their hands: पूतभृत् pūtábhr̥ta 'soldier offering purified soma in a smelter'--पूतभृत् pūtábhr̥ta 'Soma purified, carried in a vessel) by a worshpper,

The Indus Script inscription the Mehrgarh Pasupati seal (i on the photo, top line) is:

Reading of Sign 267 PLUS Sign 99: kancu ʼmũh sal 'bell-metal ingot workshop'.

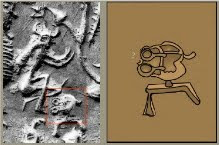

Reading of Sign 307: kamaḍha 'archer' Rebus:kammaṭa 'mint, coiner'

Reading of Slanted line: ḍhāḷ = a slope; the inclination of a plane (G.) Rebus: : ḍhāḷako = a large metal ingot

Reading of Sign 342: Sign 342 'rim-of-jar'कर्णक m. (ifc. f(आ).) a prominence or handle or projection on the side or sides (of a vessel &c ) , a tendril S3Br. Ka1tyS3r. Rebus: कर्णिक having a helm; a steersman; m. pl. N. of a people VP. (Monier-Williams) rebus:karṇī 'supercargo', 'engraver' (

Thus, together, the text message of the Mehrgarh Pasupati seal is: steersman's, supercargo's mint with bell-metal ingot workshop, largemetal ingots.

Variants of Sign 307 (Bow and arrow) ![]() kamaṭha m. ʻ bamboo ʼ lex. 2. *kāmaṭha -- . 3. *kāmāṭṭha -- . 4. *kammaṭha -- . 5. *kammaṭṭha -- . 6. *kambāṭha -- . 7. *kambiṭṭha -- . [Cf.

kamaṭha m. ʻ bamboo ʼ lex. 2. *kāmaṭha -- . 3. *kāmāṭṭha -- . 4. *kammaṭha -- . 5. *kammaṭṭha -- . 6. *kambāṭha -- . 7. *kambiṭṭha -- . [Cf. kambi -- ʻ shoot of bamboo ʼ, kārmuka -- 2 n. ʻ bow ʼ Mn., ʻ bamboo ʼ lex. which may therefore belong here rather than to kr̥múka -- . Certainly ← Austro -- as. PMWS 33 with lit. -- See kāca -- 3 ] 1. Pk. kamaḍha -- , °aya -- m. ʻ bamboo ʼ; Bhoj. kōro ʻ bamboo poles ʼ.2. N. kāmro ʻ bamboo, lath, piece of wood ʼ, OAw. kāṁvari ʻ bamboo pole with slings at each end for carrying things ʼ, H. kã̄waṛ, °ar, kāwaṛ, °ar f., G. kāvaṛ f., M. kāvaḍ f.; -- deriv. Pk. kāvaḍia -- , kavvāḍia -- m. ʻ one who carries a yoke ʼ, H. kã̄waṛī, °ṛiyā m., G. kāvaṛiyɔ m. 3. S. kāvāṭhī f. ʻ carrying pole ʼ, kāvāṭhyo m. ʻ the man who carries it ʼ. 4. Or. kāmaṛā, °muṛā ʻ rafters of a thatched house ʼ;G. kāmṛũ n., °ṛī f. ʻ chip of bamboo ʼ, kāmaṛ -- koṭiyũ n. ʻ bamboo hut ʼ. 5. B. kāmṭhā ʻ bow ʼ, G. kāmṭhũ n., °ṭhī f. ʻ bow ʼ; M. kamṭhā, °ṭā m. ʻ bow of bamboo or horn ʼ; -- deriv. G. kāmṭhiyɔ m. ʻ archer ʼ. 6. A. kabāri ʻ flat piece of bamboo used in smoothing an earthen image ʼ. 7. M. kã̄bīṭ, °baṭ, °bṭī, kāmīṭ, °maṭ, °mṭī, kāmṭhī, kāmāṭhī f. ʻ split piece of bamboo &c., lath ʼ.(CDIAL 2760) Rebus: kammaṭa 'mint, coiner'

Sign 267 is oval=shape variant, rhombus-shape of a bun ingot. Like Sign 373, this sign also signifies mũhã̄ 'bun ingot' PLUS kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'.kaṁsá Sign 278 has a circumscript: four short strokes: gaṇḍā 'four' rebus: kaṇḍa 'fire-altar'. kã̄dur m. ʻ oven ʼ (Kashmiri).: kándu f. ʻ iron pot ʼ Suśr., °uka -- m. ʻ saucepan ʼ.Pk. kaṁdu -- , kaṁḍu -- m.f. ʻ cooking pot ʼ; K. kō̃da f. ʻ potter's kiln, lime or brick kiln ʼ; -- ext. with -- ḍa -- : K. kã̄dur m. ʻ oven ʼ. -- Deriv. Pk. kaṁḍua -- ʻ sweetseller ʼ (< *kānduka -- ?); H. kã̄dū m. ʻ a caste that makes sweetmeats ʼ. (CDIAL 2726)*kandukara ʻ worker with pans ʼ. [ Thus, Sign 278 reads: kancu ʼmũh kaṇḍa sal 'bell-metal ingot implements workshop'. PLUS

|

The Silver-Capped Twisted Section of an Ancient Unicorn’s Horn, Northern Europe, AD 1526-1698. Size: 42 cm long. © Oliver Hoare Ltd "It is probable that at one time this section of a horn was preserved as a precious relic in an ecclesiastical treasury. Apart from representing the Annunciation, such horns were believed to act as an antidote to disease, the Evil Eye and other such inconveniences. Belief in these therapeutic qualities are still recorded throughout the 17th century, and probably later, long after the Council of Trent had banned them from churches, on the basis that by then nobody believed in the existence of unicorns. Its dynamic torque is most unusual. Provenance: Jean-Claude Ciancimino, London "

A Metal Unicorn Head, Indus Valley, second half 3rd millenium BC. Size: 45 cm. © Oliver Hoare Ltd. "The model for this unicorn is a type familiar from seals and terracotta figurines found at Harappa and other Indus Valley sites. European unicorns invariably have bodies like horses, while those further east have the bodies of bulls with the horn pointing upwards, rather than projecting forwards. Among the seals of Mohenjo-daro, 60 per cent show unicorns, and those from Harappa, 46 per cent. The area was teeming with unicorns.

According to scientists, the Siberian Unicorn, Elasmotherium sibiricum, was already extinct 350,000 years ago. However, a skull found recently in Kazakhstan proves they were still around a mere 29,000 years ago. Such a margin of error is a reminder to be wary of scientific opinion when dealing with something as delicate as the unicorn. Iron-smelting can be traced back to c. 2600 bce in the Indus Valley, which was probably where the technology was first developed. "

Three Indus Valley Seals with Unicorns, Indus Valley, 3rd millennium BC. Size: 3 × 3 cm; 4.5 × 4.7 cm; 3.6 × 3.8 cm. Steatite and terracotta. © Oliver Hoare Ltd

Chinese Silver Unicor, (Kylin), Probably Song dynasty, 11th–12th century AD. Size: 7 × 6.5 cm. © Oliver Hoare Ltd. "While European unicorns had horses’ bodies and Middle and South-East Asian unicorns were built like bulls, their Chinese relations were altogether more fanciful, a bit rhino-like, and clearly capable of some surprising tricks."

Jean Duvet (1485–1570), The Unicorn Purifies the Water with his Horn. Plate: 22.6 × 40.2 cm. Sheet: 23.5 × 40.9 cm. © Oliver Hoare Ltd. "A very rare engraving, printed in grey-black, c. 1545–60, from ‘The Unicorn Series’, a very good silvery impression of the second (final) state, printing with clarity, on paper with a Grapes watermark (Eisler, Bessier 68). Duvet signed his prints emblematically, with the bird plucking its down (‘duvet ’, lower right).

This lyrico-mystical engraving is fascinating on many different levels. Firstly, for the personality of its creator, Jean Duvet, a name virtually unknown today in spite of his great accomplishments. He is the earliest known French engraver, having been trained as a goldsmith by his father in Dijon. For his exceptional skills in both these areas he received the royal patronage of kings François I and Henri II. He was in charge of the complicated pageantry celebrating the triumphal entry into Langres of François I in 1533. Fortress design was another of his specialities, and his mark remains in the striking ramparts of Langres and Geneva. Among his other skills were die-making and metal-casting. His fame as an engraver rested on two series of prints: the twenty-three plates of The Apocalypse, for which he was granted the Privilege by Henri II in 1556; and the six large engravings of ‘The Unicorn Series’. Already, in 1666, Michel de Marolles, the first cataloguer of Duvet’s oeuvre, referred to him as ‘The Master of the Unicorn’.

Secondly, for the environment in which it was produced, and for which it is a giant rebus, referencing the complexity of the humanistic culture of Renaissance Europe. The new ideas that f lowed from Marcilio Ficino’s Platonic Academy in Florence, from Pico della Mirandola’s Nine Hundred Theses, from Trithemius of Sponheim, Johann Reuchlin, Paracelsus, and Cornelius Agrippa – among many others – introduced Greek philosophy, alchemy, Hermeticism, Neo-Platonism, Sufi mysticism and Cabbala into the mainstream of European thought, establishing for the first time an intellectual forum outside the Church. Most of those involved in this enterprise were part of the Church, participating in the debate about the Reformation instituted by Martin Luther, and, until the Counter-Reformation unleashed by the Council of Trent in the mid-16th century, were largely tolerated within the Catholic Church. The public burning of Giordano Bruno in Rome in 1600 signalled a brutal end to tolerance. Ficino had inspired Botticelli, Michelangelo, Raphael, Titian and Dürer, and this inspiration, along with the inf luence of those who had built upon it, provided the intellectual fabric of Renaissance France, within which artists such as Ronsard, Rabelais and Duvet f lourished. This was no New-Age-type phenomenon but a deep enquiry into the purpose of human life and its meaning. They did not reject religion, but tried with new tools to expand their understanding beyond the sterile doctrines of the Church.

Jean Duvet was a deeply religious man, Catholic in his upbringing but drawn to Luther, as were most artists of his generation. His solution was to remain a member of the Catholic Church, while keeping his connection with the communities of the Reformation. When the situation became too complicated he retired to Geneva, 80 miles from Dijon, where he had work designing fortifications and coinage. His stance is interesting and subtle, suggesting that he was able to avoid the common habit of accepting or rejecting one doctrine or another, precisely because another possibility had opened up in the humanistic environment in which he lived and worked.

Jean Adhemar wrote in his preface to Colin Eisler’s The Master of the Unicorn (New York, 1979): ‘We are amazed that Duvet was not rediscovered by the Symbolists in the nineteenth century. Probably, this is due to the extreme scarcity of his works. A Huysmans or a Robert de Montesquiou would have pronounced him “l’inextricable graveur” as they have characterized Rodolphe Bresdin for a similar amalgam of malaise and enchantment.’ Earlier in the 19th century, William Blake and Samuel Palmer must have been aware of Jean Duvet’s magical creations."

http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2017/05/04/35246334.htmlRemarkable Inscribed Chalcedony Ear-Lobe Weight, Mergargh, Indus Valley, c. 3000 BC, Size: 42 cm high, 5.9 cm diameter. © Oliver Hoare Ltd

Along the upper rim of this beguiling object are five characters of the Indus Valley alphabet, the tantalizing glyphs of an undeciphered language. The choice of stone, polished to reveal a milky ‘eye’ and undulating ribbons, as well as its seductive concave surfaces, add to its visual and tactile appeal. It has weight, too, which makes its purpose as an ear appendage surprising at first, until one remembers the tradition of such adornments in the pierced and stretched lobes of the statues of goddesses throughout the Indian subcontinent since early times.

Comment posted:Remarkable Inscribed Chalcedony Ear-Lobe Weight, Mergargh, Indus Valley, c. 3000 BC, Size: 42 cm high, 5.9 cm diameter. © Oliver Hoare Ltd This 'weight' is said to have an inscription with five Indus Script alphabets. I shall be grateful for an image of the incription and the alphabets used. Thanks and regards. S.Kalyanaraman Sarasvati Research Centre

http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2017/05/04/35246334.html

(Attached image) includes image of a seal showing a shaman and an inscription. Parallels the famous Pasupati seal m0304. The website states that this is 3 cm square, said to be from Indus Valley seals, Mehrgarh area c. 3500 BCE.. The website says:

Alain.R.Truong > Cabinet de curiosités > Exhibition dedicated to rare and curious objects from over 5,000 years of civilisation opens in London

04 mai 2017

Exhibition dedicated to rare and curious objects from over 5,000 years of civilisation opens in London

Indus Valley Seals, Mehrgarh area, circa 3500 BC, Size: 6 cm long. © Oliver Hoare Ltd

It is assumed that the seals were used for trade, particularly long-distance trade, that the different animals are badges of clans, and that the script spells out the name or title of the owner. The theory has several awkward corners, however. There are about ten animals which are most commonly shown, while at Mohenjo-daro 60 per cent of the animal seals show unicorns. At Harappa it is 46 per cent. There are other animals that are very rare, such as the tiger and markhor goat, and occasionally a horned and naked man seated in a yogic pose with an erection turns up. The same inscription appears with different animals, and sometimes several animals appear on one seal, or a single animal with three different heads. Nevertheless, at their best they are objects of great refinement and beauty, and all the more tantalizing for their undecipherable script. Most are made from steatite that has been hardened by heating after engraving, with a pierced knob at the back. (See also no. 6 for the seals with unicorns.)

a. A bearded bull and inscription. Size: 3.4 cm square

b. A fine zebu and inscription. Size: 3.3 cm square

c. A zebu and inscription. Size: 2.9 cm square

d. A rhinoceros and inscription. Size: 3.6 × 3.4 cm

e. A horned shaman and inscription. Size: 3 cm square

f. An elephant and inscription. Size: 2.6 cm square

g. A bull and inscription. Size: 3 cm square

h. A markhor goat and inscription. Size: 2.6 cm square

i. A unicorn, incense burner and inscription. Size: 3 cm square

j. A horned buffalo and inscription. Size: 2.7 cm square

http://www.alaintruong.com/archives/2017/05/04/35246334.html

https://tinyurl.com/y39d9cut--Kneeling adorant carrying a pot on Indus Script inscriptions is पूतभृत् pūtábhr̥ta 'soldier offering purified soma in a smelter'--पूतभृत् pūtábhr̥ta 'Soma purified, carried in a vessel) by a worshpper, soldier signifed on Indus Scriptपूतभृत् m. a kind of vessel which receives the सोम juice after it has been strained (तैत्तिरीय-संहिता, वाजसनेयि-संहिता, ब्राह्मण)(Monier-Williams) pūtá |

m1186

m1186

![clip_image062[4]](http://kalyan97.files.wordpress.com/2007/06/clip-image0624-thumb.jpg?w=99&h=45)