Shahr-i Sokhta, terracotta cakes, Periods II and III, I, MAI 1026 (front and rear); 2. MAI 376 (front and rear); 3. MAI 9794 (3a, photograph of front and read; 3b, drawing -- After Fig. 12 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008) Inventory of terracotta cakes Shahr-i Sokhta. After Salvatori and Vidale, 1997-79. Table 1 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008)

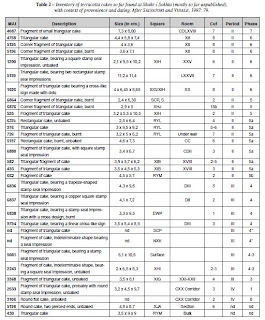

Inventory of terracotta cakes Shahr-i Sokhta. After Salvatori and Vidale, 1997-79. Table 1 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008) Number nd percentages of terracotta cakes found t Shahr-i Sokhta, total 31. (After Table 2 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008).

Number nd percentages of terracotta cakes found t Shahr-i Sokhta, total 31. (After Table 2 in E. Cortesi et al. 2008).

"Terracotta cakes. Variously called 'terracotta tablets', 'triangular plaques' or 'triangular terracotta cakes' these artifacts (fig. 12, tables 2 and 3), made of coarse chaff-tempered clay, are a very common find in several protohistoric sites of the Subcontinent from the late Regionalization Era (2800-2600 BCE) to the Localization Er (1900-1700 BCE). In this latter time0-span they frequently assume irregular round shapes, to finally retain the form of a lump of clay squeezed in the hand. Despite abudant and often unnecessary speculation, archaeological evidence demonstrates tht they were used in pyrotechnological activities, both in domestic and industrial contexts. The most likely hypothesis is tht these objets, in the common kitchen areas, were heated to boil water, and used as kiln setters in other contexts. Shahr-i Sokhta is the only site in the eastern Iranian plateau where such terracotta cakes, triangular or more rarely rectangular, are found in great quantity. Their use, perhaps by families or individuals having special ties with the Indus region, might have been part of simple domestic activities, but this conclusion is questioned by the fact that several terracotta cakes, at Shahr-i Sokhta, bear stamp seal impressions or other graphic signs (in more than 30% of the total cases). In many cases the actual impressions are poorly preserved, and require detailed study. Perhaps these objects used in some form of administrative practice. Although many specimens are fired or burnt, a small percentge of the 'cakes' found at Shahr-i Sokhta is unfired (table 2). On the other hand, their modification in the frame of one or more unknown semantic contexts is not unknown in the Indus valley. At Kalibangan (Haryana, India), for example, two terracotta cake fragments respectively bear a cluster of signs of the Indus writing system and a possible scene of animal sacrifice in front of a possible divinity. While a terracotta cake found at Chanhu-Daro (Sindh, Pakistan) bears a star-like design, anothr has three central depressions. The most important group of incised terracotta cakes comes from Lothal, where the record includes specimens with vertical strokes, central depressions, a V-shaped sign, a triangle, and a cross-like sign identical to those found at Shahr-i Sokhta. Tables 2 and 3 shows a complete inventory of these objects (most so far unpublished), their provenience and proposed dating, and finally summarize their frequencies across the Shahr-i Sokhta sequence. The data suggest that terracotta cakes are absent from Period I. This might be due to the very small amount of excavated deposits in the earliest settlement layers, but the almost total absence of terracotta cakes in layers dtable to phases 8-7, exposed in some extention both in the Eastern Residential Area and in the Centrl Quarter, is remarkable. The majority of the finds belong to Period II, phases 6 and 5 (mount together to about 60% of the cases). As the amount of sediments investigated for Period III in the settlement areas, for various reasons, is much less than what was done for Period II, the percentage of about 40% obtained for Period III (which, we believe, dates to the second hald of the 3rd millennium BCE) actually demonstrates that the use of terracotta cakes at Shahr-i Sokht continued to increase." (E. Cortesi, M. Tosi, A. Lazzari and M. Vidale, 2008, Cultural relationships beyond the Iranian plateau: the Helmand Civilization, Baluchistan and the Indus Valley in the 3rd millennium, pp. 17-18) Indus terracotta nodules. Source: "Terra cotta nodules and cakes of different shapes are common at most Indus sites. These objects appear to have been used in many different ways depending on their shape and size. The flat triangular and circular shaped cakes may have been heated and used for baking small triangular or circular shaped flat bread. The round and irregular shaped nodules have been found in cooking hearths and at the mouth of pottery kilns where they served as heat baffles. Broken and crushed nodule fragments were used instead of gravel for making a level foundation underneath brick walls."

Indus terracotta nodules. Source: "Terra cotta nodules and cakes of different shapes are common at most Indus sites. These objects appear to have been used in many different ways depending on their shape and size. The flat triangular and circular shaped cakes may have been heated and used for baking small triangular or circular shaped flat bread. The round and irregular shaped nodules have been found in cooking hearths and at the mouth of pottery kilns where they served as heat baffles. Broken and crushed nodule fragments were used instead of gravel for making a level foundation underneath brick walls." Terracotta cake. Mohenjo-daro Excavation Number: VS3646. Location of find: 1, I, 37 (near NE corner of the room)."People have many different ideas about how these triangular blocks of clay were used. One idea is that they were placed inside kilns to keep in the heat while objects were fired. Another idea is that they were heated in a fire or oven, then placed in pots to boil liquids." Source: http://www.ancientindia.co.uk/indus/explore/nvs_tcake.html

Terracotta cake. Mohenjo-daro Excavation Number: VS3646. Location of find: 1, I, 37 (near NE corner of the room)."People have many different ideas about how these triangular blocks of clay were used. One idea is that they were placed inside kilns to keep in the heat while objects were fired. Another idea is that they were heated in a fire or oven, then placed in pots to boil liquids." Source: http://www.ancientindia.co.uk/indus/explore/nvs_tcake.html

These terracotta cakes are like Ancient Near East tokens used for accounting, as elaborated by Denise Schmandt-Besserat in her pioneering researches.

The context in which an incised terracotta cake was found at Kalibangan is instructive. I suggest that terracotta cakes were tokens to count the ingots produced in a 'fire-altar' and crucibles, by metallurgists of Sarasvati civilization. This system of incising is found in scores of miniature incised tablets of Harappa, incised with Indus writing. Some of these tablets are shaped like bun ingots, some are triangular and some are shaped like fish. Each shape should have had some semantic significance, e.g., fish may have connoted ayo 'fish' as a glyph; read rebus: ayas 'metal (alloy)'. A horned person on the Kalibangan terracotta cake described herein might have connoted: kōṭu 'horn'; rebus: खोट khōṭa 'A mass of metal (unwrought or of old metal melted down); an ingot or wedge. Hence 2 A lump or solid bit'; खोटसाळ khōṭasāḷa 'Alloyed--a metal'(Marathi) A stake associated with the fire-altar was ढांगर [ ḍhāṅgara ] n 'A stout stake or stick as a prop to a Vine or scandent shrub]' (Marathi); rebus:ḍhaṅgar 'smith' (Maithili. Hindi)Harppa. Two sides of a fish-shaped, incised tablet with Indus writing. Hundreds of inscribed texts on tablets are repetitions; it is, therefore, unlikely that hundreds of such inscribed tablets just contained the same ‘names’ composed of just five ‘alphabets’ or ‘syllables’, even after the direction of writing is firmed up as from right to left.

Kalibangan. Mature Indus period: terracotta cake incised with horned deity. Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India.

Kalibangan. Mature Indus period: terracotta cake incised with horned deity. Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India. "Fire Altars. At Kalibangan, fire Vedic altars have been discovered, similar to those found at Lothal which S.R. Rao thinks could have served no other purpose than a ritualistic one.[18] These altars suggest fire worship or worship of Agni, the Hindu god of fire. It is the only Indus Valley Civilization site where there is no evidence to suggest the worship of the "mother goddess".

"Fire Altars. At Kalibangan, fire Vedic altars have been discovered, similar to those found at Lothal which S.R. Rao thinks could have served no other purpose than a ritualistic one.[18] These altars suggest fire worship or worship of Agni, the Hindu god of fire. It is the only Indus Valley Civilization site where there is no evidence to suggest the worship of the "mother goddess".

Within the fortified citadel complex, the southern half contained many (five or six) raised platforms of mud bricks, mutually separated by corridors. Stairs were attached to these platforms. Vandalism of these platforms by brick robbers makes it difficult to reconstruct the original shape of structures above them but unmistakable remnants of rectangular or oval kuṇḍas or fire-pits of burnt bricks for Vedi (altar)s have been found, with a yūpa or sacrificial post (cylindrical or with rectangular cross-section, sometimes bricks were laid upon each other to construct such a post) in the middle of each kuṇḍa and sacrificial terracotta cakes (piṇḍa) in all these fire-pits. Houses in the lower town also contain similar altars. Burnt charcoals have been found in these fire-pits. The structure of these fire-altars is reminiscent of (Vedic) fire-altars, but the analogy may be coincidental, and these altars are perhaps intended for some specific (perhaps religious) purpose by the community as a whole. In some fire-altars remnants of animals have been found, which suggest a possibility of animal-sacrifice." Source: Elements of Indian Archaeology (Bharatiya Puratatva,in Hindi) by Shri Krishna Ojha, published by Research Publications in Social Sciences, 2/44 Ansari Riad, Daryaganj, New Delhi-2, pp.119-120. (The fifth chapter summarizes the excavation report of Kalibangan in 11 pages).

Manuel, J. 2010. The Enigmatic Mushtikas and the Associated Triangular Terracotta Cakes: Some Observations. Ancient Asia 2:41-46, DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.5334/aa.10204

The Enigmatic Mushtikas and the Associated Triangular Terracotta Cakes: Some Observations

Abstract

For over four decades, now, mushtikas and its common associate, the triangular terracotta cakes have been believed to be part of ‘fire altars’. This is, in spite of the fact that, either or both of these have been found from hearths, ovens, kilns, as flooring material, on walls, in passages, streets, bathrooms and therefore obviously near commodes. Further, the great variety of central stele and construction material, size and shape, materials found within ‘fire altars’ suggest that, all the above were devoid of religious symbolism and used to achieve domestic or industrial objectives. The cakes being primarily associated with run of the mill economic activities ended up in diverse and defiling contexts. However, like many cultures across time and space Harappans may also have used the medium of fire for offering sacrifices. Therefore the existence of ‘fire altars’ is not denied as such, but these then should not have the ubiquitous cakes, at the least.

Introduction

The terracotta object varyingly described as ovoid (Rao, 1985: 19, 26, 27), Bicones (Fairservis, 1993: 109) circular biconvex terracotta ‘cakes’ (Lal, 1997: 227) ‘round ones with a deep finger impression in the center’ (Dikshit, 1993: 399), terracotta mushtis (Mehta, 1993: 168), mushtikas (Dales & Kenoyer, 1993: 490; Nath, 1998: 41) and most recently as ‘idli shaped terracotta cake with a thumb impression’ (Rao, 2006: 40,41) have been commonly found associated with the mature Harappan remains. A small Mature Harappan period site like Allahdino yielded 24000 bicones (mushtikas) and 2600 triangular terracotta cakes (Fairservis, 1993: 109). The mushtikas and triangular cakes were in vogue even at rural sites like Zekda (Mehta, 1993: 168) during the mature period. Similarly, the triangular terracotta cakes are also generally known as most commonly associated with Mature Harappan Culture (Allchin, 1993: 235). However, the emergence of the terracotta cakes have been reported from the ‘pre Indus phase at Mehergarh and Nausharo’ (Jarrige, 1995: 21) and early Harappan phase at Bhirrana (Rao, 2006: 40,41) and Kalibangan (Madhu Bala, 2003: 231, 233). The triangular terracotta cakes in particular were also obtained from Hakra Ware cultural assemblage at Bhirranna, where it was collected as unbaked specimen (Rao et al., 2005: 63). Besides the mature Harappan period both variety of cakes have been reported from other time and space contexts also, albeit in much lesser numbers. The mushtikas have also been reported from late Harappan context at Hulas (Dikshit, 1993: 399) and as surface finds from Moti Pipli, a Harappan affiliated Chalcolithic site (IAR, 1992-93: 19). The triangular terracotta cakes have also been found in later context as at Lothal (Rao, 1985: 15) and Dholavira (IAR, 1991-92: 30). Thus both type of cakes although have been found from a wide span of temporal settings yet their overwhelming preponderance is clearly seen in the Mature Harappan Period, when urbanization, industrial activities and long distance trade were very much in vogue. Even though after the breakdown of the grand system the Harappans held on to some of the practices, the utility of terracotta cakes had probably reduced and therefore the sharp decline in their numbers as observed during the

Association with rituals

The mushtikas and the triangular terracotta cakes have mostly been associated with rituals. From the early sixties the terracotta cakes were supposed to have been used in the performance of ‘fire altar’ rituals during the mature Harappan period as at Kalibangan (IAR, 1962-63: 30). Later, the presence of terracotta cakes, ash and the cylindrical blocks in fire places were reckoned as the usual contents of ‘fire altars’ (IAR, 1968-69: 31). Sankalia (1974: 350) also mentions that ‘in the center of the pit was a cylindrical or rectangular (sundried or prefired bricks)’ and around this central stele of ‘fire altar’, ‘flat triangular or circular terracotta pieces, known hitherto as terracotta cakes’ were placed. Further, according to Rao (1979: 121 & 1985:15,24,26,27) these ovoid balls and triangular cakes ‘were used for ritualistic purposes’ and found in different types of ‘fire altars’. The triangular terracotta cakes and mushtikas were noticed as offering in ‘fire altars’ at Rakhigarhi (Nath, 1999: 48). Terracotta cakes have also been reported from Tarkhanewala Dera as part of a square ‘fire altar’ (Trivedi & Patnaik, 2004: 31). Thus, mushtikas and triangular cakes now have been reportedly associated with the phenomenon of ‘fire altars’ for well over four decades. Pertinently, besides its association with fire, triangular terracotta cakes were earlier reported to have ‘special significance in connection with ritual bathing or other ablutions’ by several scholars including Gordon (Allchin, 1993: 235).

Contexts of findings

The mushtikas and the triangular terracotta cakes have been found from a large number of contexts other than ‘fire altars’. Triangular terracotta cakes have been found at the mouth of kiln at Harappa (Dales & Kenoyer, 1993: 490). At Sanghol terracotta cakes have been found in kiln that yielded unbaked pottery (Sharma, 1993: 157). Cakes have been reported from potters kiln at Tarkhanewala in association with ash etc. (Trivedi & Patnaik, 2004: 31). Rao (1985: 24) reported ‘an altar like enclosure with terracotta triangular cakes and a stone quern’. Nath (1998: 41) is of the opinion that excessive concentration of terracotta cakes including mushtikas at Rakhigarhi is due to the craft activity. At Nausharo, clay built containers ‘had terracotta cakes used as heat conservers in the fireplaces’ (Jarrige, 1994: 288). At Rakhigarhi, a jar filled with terracotta cakes in the base portion is supposed as an hearth for heating semi precious stones at different stages of workmanship in a lapidary workshop (IAR, 1999-2000: 32). Terracotta cakes along with small vases, charred bones and ashes were found within ‘burial urns’ by Tessitori at Kalibangan, during his survey of Rajputana between 1916-1919 (Thapar, 2003: 13). Another place wherein the triangular terracotta cakes occur as decorations on walls (Rao, 1979: 215). According to Nath, (1998: 43) the mushtikas were ‘prepared to keep them in cowdung cake fire pans as heat absorbents, thereafter it was reused either in floor bedding or raising levels’. Successive mushtika beddings in massive mud brick fortification at Rakhigarhi and mushtika bedding in cutting of a street at Kalibangan (Nath, 1998: 41) show the various type of less than sacrosanct contexts these cakes are found.

Triangular cakes have been found in ‘houses and streets’ (Mackay, 1938: 429), ‘passages’ (Rao, 1979: 113), ‘surface of lane’, ‘road’ (Sant et. al., 2005: 53), floors of mud brick houses in association with ovoid terracotta balls ‘plastered with mud’ (Rao, 1979: 83), ‘rooms paved with bricks or fired terracotta cakes’ (Agrawal, 2007: 79), as soling material along with mushtikas for raising levels of store houses (IAR, 1997-98: 57), etc. The triangular terracotta cakes have also been reported to be found from bathrooms, prompting scholars to suggest that these were used in ‘ritual bathing’ (Allchin, 1993: 235). Pertinently, Agrawal (2007: 143) also points out that ‘most houses or groups of houses had private bathing areas and latrines, as well as private wells. The early excavators at both Mohenjodaro and Harappa did not pay much attention to this essential feature’. According to him, the recent HARP excavations at Harappa are finding what appear to be latrines in almost every house. Agrawal mentions that, ‘these sump pot latrines were probably cleaned out quite regularly by a separate class of labourers’. Pertinently, had these large jars or sump pots sunk into the floors in or near bathing platforms been identified as commodes earlier, the scholars would not have correlated the presence of triangular terracotta cakes in bathrooms with ‘ritual bathing’. Earlier the triangular terracotta cakes presence in bathrooms was recognized but since the latrines contiguous to the bathing platforms were not commonly known its presence obviously in the vicinity of commodes could not have also been known as such. Had these facts been known then, none would have given hallowed status to the triangular terracotta cakes now understood to be found in the conjoined latrine bathrooms. The less than sublime presence of these cakes could not have been given any use other than just plain bathing. For, if anyone insistent on ‘ritual bathing’ even after the triangular terracotta cakes being known to have been found in the vicinity of the earlier unidentified commodes would have to associate defecation also with part of rituals.

Discussion

Pertinently, the presence of mushtikas and triangular cakes in a bewildering range of contexts does not allow it to be associated with ceremonies associated with fire, even though they are more often associated with places of fire. Even though cakes of food items are offered to the gods in the fire altars the mushtikas and triangular cakes also could be construed as something similar, which incidentally did not find mention in the Vedic literature. However, problem arises due to the fact that these cakes are found in not only mundane contexts of industrial activities but also in such places that defiles their once hallowed status. The finding of mushtikas and/or its common associate the triangular terracotta cakes in contexts, like: as soling material, as part of floor, in streets, passages, and bathrooms and obviously in the conjoined latrines does not enable it to achieve a sanctified status. In fact, its presence in those fire places which otherwise could have been considered as ‘fire altars’, prejudices one about its defiling presence at a sacrosanct spot. In fact, those fireplaces without these cakes could yet be fire altars. Pertinently, not all ‘fire altars’ have the mushtikas and triangular terracotta cakes within them. At Rakhigarhi several ‘fire altars’ (Nath, 1999: 48 & IAR, 1997-98: 60) have been identified wherein cakes have not been reported. One of these has burnt shells of fruits, which formed part of the offerings. At Lothal also several ‘fire altars’ have been identified by Rao (1979: 117) in which although ash, pottery and or bones are reported but the cakes were not mentioned. On the availability of other concurring evidence, these and others like these could be verily declared as ‘fire altars’. However, those fire places with both or either of the terracotta cakes, being used, as heat conservers are definitely not ‘fire altars’.

Thus, the fireplaces with mushtikas and triangular terracotta cakes therefore has to be the run of the mill, hearths, ovens, kilns, etc. Pertinently, cakes have been found in diverse contexts associated with heat, namely: at the mouth of a pottery kiln at Harappa (Dales & Kenoyer, 1993: 490), with some unbaked pottery in a kiln at Sanghol (Sharma, 1993: 157), in the pottery kiln at Tarkhanewala Dera (Trivedi & Patnaik, 2004: 31), besides in jar identified as hearth at Rakhigarhi (IAR 1999-2000: 32). The findings do hint that the cakes were used in places where prolonged heating was required. Nath (1998: 41) has suggested that the “excessive concentration of terracotta cakes including the mushtikas” indicate to the “intensive involvement of the people in their craft activity”. The cakes therefore appear to be primarily used as heat conservers as reported at Nausharo (Jarrige, 1993: 288) allowing “air into the kiln and at the same time effectively sealing in the heat” as suggested by Dales & Kenoyer (1993: 490) with reference to the triangular terracotta cakes found in the pottery kiln at Harappa. It appears that the frequent finding of pottery along with the terracotta cakes reinforces the possibility that some of the many types of ‘fire altars’ were potters kiln and other industrial fireplaces for baking different types of pottery and processing variety of craft items. Since the cakes did not have any religious value, it could and did end up in streets, floors, bathrooms, etc. Even the reporting of the cakes being found in ‘burial urn’ by Tessitori at Kalibangan does not gain it any religious value as mundane objects of daily use are routinely found along with burial remains. Pertinently, Jarrige (1995: 21) mentions the ‘fireplaces filled with stones or terracotta cakes of the pre-Indus period at Mehergarh and Nausharo and the Indus period at Nausharo’. By extension of logic, if the terracotta cakes are deemed as offerings then the stones also have to be of the same class. Alternatively, if the stones found in the fireplaces are not deemed holy the terracotta cakes also have to be deemed as mundane objects used in hearths and kilns. These cakes, therefore, are nothing else other than what Allchin (1993: 233-238) has termed it, namely, ‘Substitute Stones’.

Further, unlike mundane things, objects of religious value do have a high degree of standardization in mediums used, forms of expression and the association of other objects. These are also found only in limited areas not anywhere and everywhere. Sacred objects even if they have outlived there use would never be used in bathrooms and latrines, nor thrown away on lanes and roads or used as soling in floors to be trodden under the foot of men and animals. Earlier, Rao (1979: 215) had decried that ‘it is not safe to attribute cult value to an object on the basis of its shape or just because no other satisfactory explanation is available in the present state of our knowledge.’ Specifically citing the example of triangular terracotta cakes, he wrote that these ‘were once considered to be cult objects are found to have been used in flooring and for decorating the walls of the houses’. Again those fire altars with the central stele, also does not have any defining attribute regarding the shape or material of the stele or the enclosure nor the range of objects found within. Thus a clay stele in one altar, a mud brick in another, a baked brick in yet another, a cylindrical yashti here and a square one in the adjacent ‘fire altar’ does not show any uniformity, so necessary for outlining religious practices. It is intriguing that scholars did not find ‘the anything would do’ mindset as inferred by the permutations and combinations of material remains of the said ‘fire altars’ strange. Such adhoc substitutions and varieties are seen in industrial activities where the end product has to be achieved irrespective of the construction of the workplace. Where as in matters religious, symbolism rules the roost and uniformity in religious practices and materials are invariably sought for. Albeit, one should say in the same breath, that there is no denying of the fact that those ‘fire altars’ with central stele could be ‘fire altars’. However, such ‘fire altars’ then should have some formal attributes with regard to the construction and materials including the stele, across several similar ones at least in the same phase of the site.

Conclusion

Thus in view of the evidence obtained from many sites wherein the mushtikas and triangular terracotta cakes were used as ‘heat conservers’ besides the later degraded contexts of association of the terracotta cakes supposedly used in ‘rituals’, it appears to the present author that those ‘fire altars’ having these cakes cannot be ‘fire altars’. Moreover, even the association of the two type of cakes in ‘fire altars’ with central stele also does not complement the evidence of ‘fire altars’, as the casual approach in construction of the stele is itself not above circumspection. In all probability, the ‘fire altars’ having the mushtikas and triangular terracotta cakes, both observed in less than sublime conditions, even if it/they be associated with such fire places which, for other reasons appear as ‘fire altars’ including those with the central stele are not actually ‘fire altars’. In fact, they were fire places built up for different type of industrial uses. Thus, only those fire places which do not have these terracotta cakes and are having food offerings with a standard type of stele or without stele could be ‘fire altars’ all others are hearths, ovens, kilns, etc.

Acknowledgements

I am thankful to Shri K.K. Muhammed, and to Dr Narayan Vyas, both Superintending Archaeologists, for always encouraging academic work and for being available for discussions, whenever needed. Thanks are due towards Smt Hemlata Ukhale, Librarian, Bhopal Circle, for not only providing the required literature at the earliest but also suggesting more sources that has been frequently found useful. Last, but not least the miscellaneous technical help rendered by Shri Vijay Mishra is acknowledged herein.

Bibliography

Agrawal, D.P. 2007. The Indus Civilization: An Interdisciplinary Perspective, Aryan Books International, New Delhi.

Allchin, B. 1993. Substitute Stones, in G. L. Possehl eds. Harappan Civilization: A Recent Perspective, Oxford & I.B.H. Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi, pp 233-238.

Dales, G. F. and J. M. Kenoyer 1993. The Harappan Project 1986-1989: New Investigation at an ancient Indus City. in G. L. Possehl eds. Harappan Civilization: A Recent Perspective, Oxford & I.B.H. Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi.

Dikshit, K. N. 1993. Hulas and the Late Harappan Complex in Western Uttar Pradesh, in G. L. Possehl eds. Harappan Civilization: A Recent Perspective, Oxford & I.B.H. Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi.

Fairservis, W.A. 1993. Allahdino: An Excavation of a small Harappan Site, in G. L. Possehl eds. Harappan Civilization: A Recent Perspective, Oxford & I.B.H. Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd., New Delhi.

IAR Indian Archaeology, 1962-63: A Review, Annual Bulletin of Archaeological Survey of India, 30.

IAR Indian Archaeology, 1968-69: A Review, Annual Bulletin of Archaeological Survey of India. 31

IAR Indian Archaeology, 1991-92: A Review, Annual Bulletin of Archaeological Survey of India. 30.

IAR Indian Archaeology, 1992-93: A Review, Annual Bulletin of Archaeological Survey of India. 19.

IAR Indian Archaeology, 1997-98: A Review, Annual Bulletin of Archaeological Survey of India. 57,60.

IAR Indian Archaeology, 1999-2000: A Review, Annual Bulletin of Archaeological Survey of India. 32.

Jarrige, C. 1994. The Mature Indus Phase at Nausharo as seen from a block of period III, Proceedings of the Twelfth International Conference of the European Association of South Asian Archaeologists, I:288.

Jarrige,J.F. 1995. From Nausharo to Pirak: Continuity and change in the Kachi/Bolan Region from the 3rd to the 2nd Millennium B.C., Proceedings of the Thirteenth International Conference of the European Association of South Asian Archaeologists, I: 21.

Lal, B.B. 1997. The Earliest Civilization of South Asia, 227, Aryan Books International, Delhi.

Mackay, E.J.H. 1938. Further Excavations at Mohenjo-daro, Govt. of India Press, New Delhi.

Madhu Bala 2003. Minor Antiquities, in B.B. Lal, J.P. Joshi, B.K. Thapar, Madhu Bala. eds Excavations at Kalibangan: The Early Harappans(1960-69), pp 231-233. Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi.

Mehta, R.N. 1993. Some Rural Harappan Settlements in Gujarat, in G. L. Possehl eds. Harappan Civilization: A Recent Perspective, Oxford & I.B.H. Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi.

Nath, A. 1997-1998. Rakhigarhi: A Harappan Metropolis in Sarasvati- Drishdavati Divide, Puratattva 28: 41,43.

Nath, A. 1998-1999. Further Excavations at Rakhigarhi, Puratattva 29: 48.

Rao, L.S., Nandini B. Sahu, Prabhas Sahu, Samir Diwan and U.A. Shastri. 2004-2005. New Light on the Excavation of Harappan Settlement at Bhirrana, Puratattva 35: 63,65.

Rao, L.S. 2006. Settlement Pattern of the Predecessors of the Early Harappans at Bhirrana, District Fatehbad, Haryana, Man and Environment XXXI no 2 : 41,42.

Rao, S.R. 1979. Lothal: A Harappan Port Town, 1955-62, Vol I: 83, 113, 117, 121, 215, Archaeological Survey of India, New Delhi.

Rao, S.R. 1985. Lothal, Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi.

Sankalia, H.D. 1974. The Prehistory and Proto history of India and Pakistan, Deccan College Postgraduate Research Institute, Poona.

Sant, U., T.J. Baidya, N.G. Nikoshey, N.K. Sinha, S. Nayan, J.K. Tiwari and A. Arif. 2004-2005. Baror - A New Harappan Site in Ghaggar Valley. A Preliminary Report, Purattatva 35:53.

Sharma, Y. D. 1993. Harappan Complex on the Sutlej ( India) in G. L. Possehl eds Harappan Civilization: A Recent Perspective, Oxford & I.B.H. Publishing Co. Pvt. Ltd, New Delhi.

Thapar, B.K. 2003. Discovery and Previous Work, in B.B. Lal, J.P.Joshi, B.K. Thapar, Madhu Bala eds. Excavations at Kalibangan: The Early Harappans (1960-69), Archaeological Survey of India, Delhi.

Trivedi, P.K. and J.K. Patnaik. 2003-2004. Tarkhanewala Dera and Chak 86 (2003-2004), Puratattva 34: 31.

Many conjectures have been made about the functions served by the enigmatic terracotta cakes:

The Indus valley cones, cakes and archaeologists

S. V. Pradhan Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute Vol. 80, No. 1/4 (1999), pp. 43-51 Source:http://www.jstor.org/stable/41694575

The Tiny Steatite Seals of Harappa

See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.in/2013/04/bronze-age-writing-in-ancient-near-east.htmlBronze-age writing in ancient Near East: Two Samarra bowls and Warka vase