https://tinyurl.com/yydb7xls

This monograph presents decipherment of the following five sectios Indus Script inscriptions/artifacts (hypertexts) from Salut,Oman:

Section 1. Salut potsherd with seal impression (After Fig. 10 in Dennys Frenez et al, 2016)

gaṇḍa ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali) Vikalpa: ponea ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: pon ‘gold’ (Ta.)

Section 2. Salue Inscribed potsherd (After Fig. 4 in Dennys Frenez et al, 2016)

gaṇḍa ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali) Vikalpa: ponea ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: pon ‘gold’ (Ta.)

Section 3. Salut, Oman ivory comb inscribed with dotted circles

Section 4. ![]() Bronze snake, Salut, Oman. Salut, Oman

Bronze snake, Salut, Oman. Salut, Oman

Salalah, The Museum of Frankincense Land  Bronze snake, Salut, Oman. Salut, Oman

Bronze snake, Salut, Oman. Salut, Oman Bronze

L 23, W 5.5, Th 1.5

Cobrahood hypertext: Hieroglyph of hood of cobra: phaḍā f (फटा S)

The hood of Coluber Nága

&c Ta. patam cobra'shood. Ma. paṭam id. Ka. peḍe id. Te. paḍaga id. Go. (S.) paṛge, (Mu.) baṛak, (Ma.) baṛki, (F-H.) biṛki hood of serpent (Voc. 2154). / Turner, CDIAL, no. 9040, Skt. (s)phaṭa-, sphaṭā- a serpent's expanded hood, Pkt. phaḍā- id. For IE etymology, see Burrow, The Problem of Shwa in Sanskrit, p. 45.(DEDR 47) phaṭa n. ʻ expanded hood of snake ʼ MBh. 2. *phēṭṭa -- 2 . [Cf. phuṭa -- m., ˚ṭā -- f., sphuṭa -- m. lex., ˚ṭā -- f. Pañcat. (Pk. phuḍā -- f.), sphaṭa -- m., ˚ṭā -- f., sphōṭā -- f. lex. and phaṇa -- 1 . Conn. words in Drav. T. Burrow BSOAS xii 386]1. Pk. phaḍa -- m.n. ʻ snake's hood ʼ, ˚ḍā -- f., M. phaḍā m., ˚ḍī f.2. A. pheṭ, phẽṭ. (CDIAL 9040) Rebus: phaḍa फड 'manufactory, company, guild, public office',

Section 5. Stone seal of Salut with Indus Script inscription (field symbol: trough+ ox PLUS text of hypertexts/hieroglyphs) signifies pattar 'feeding trough' rebus: pattāri, 'merchant' of barad 'ox' rebus: bharat'alloy of copper, pewter,tin'.

New Indus Finds in Salut, Oman

June 26th, 2016

Exciting new discoveries through 2015 at Salut tower in Oman show how extensive Indus trade and relationships with this area were during the Bronze Age (2500-2000 BCE). The article Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction by Denys Frenez, Michele Degli Esposti, Sophie Méry and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer describes and explains the finds in detail. These include include children's toys like a bird whistle, a seal made of chlorite, numerous pottery fragments of types common in places like Harappa, and much else that suggests that Indus traders were active and settled well inside the Omani coast. These recent excavations are led by the Italian Mission to Oman in collaboration with the Office of the Adviser to His Majesty the Sultan for Cultural Affairs.

"This evidence provides support for similar discoveries from excavations of towers and graves in Bāt, and suggests that the interaction between Indus communities and the Omani interior was much more extensive than previously thought," write the authors. Ancient Oman, during what is referred to as the Um al Nair period, is called "Magan" in ancient Mesopotamian texts, was known as a source of copper. The work described in the article below is yet another piece of evidence pointing to the extensive trade that must have once existed among the handful of sophisticated Bronze Age civilizations in the area, supporting wealth generation as well as a the flow of ideologies, beliefs and cultural practices.

Article: Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction

Website: The Salut Museum/Universita di Pisa website

1. Salut archaeological site, Oman. Note that this is not the Bronze Age tower ST1 but the later Iron Age "castle."

2. Seal impressed fragment, likely belonging to an Harappan ledge shouldered jar, the impression showing two confronting bulls and some Harappan script (l 3.6 cm, w. 5.5 cm, th. 0.7 cm).

3. This stone square stamp seal is probably the best example of an Indus-inspired seal found so far in Oman.

4. Among the luxury imported objects discovered in Ras al-Jinz, along the Omani coast, there is this beautiful comb made of elephant ivory. As well as pots, beads and a copper stamp seal, the comb comes from Harappa, one of the main sites of the Indus civilization.

5. Fragment, from Salut, can be identified as a hollow clay “toy” in the shape of a bird: this kind of artifact is well known from Harappan sites (l. 8.5 cm, w. 7 cm, h. 5.5 cm).

"This evidence provides support for similar discoveries from excavations of towers and graves in Bāt, and suggests that the interaction between Indus communities and the Omani interior was much more extensive than previously thought," write the authors. Ancient Oman, during what is referred to as the Um al Nair period, is called "Magan" in ancient Mesopotamian texts, was known as a source of copper. The work described in the article below is yet another piece of evidence pointing to the extensive trade that must have once existed among the handful of sophisticated Bronze Age civilizations in the area, supporting wealth generation as well as a the flow of ideologies, beliefs and cultural practices.

Article: Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction

Website: The Salut Museum/Universita di Pisa website

1. Salut archaeological site, Oman. Note that this is not the Bronze Age tower ST1 but the later Iron Age "castle."

2. Seal impressed fragment, likely belonging to an Harappan ledge shouldered jar, the impression showing two confronting bulls and some Harappan script (l 3.6 cm, w. 5.5 cm, th. 0.7 cm).

3. This stone square stamp seal is probably the best example of an Indus-inspired seal found so far in Oman.

4. Among the luxury imported objects discovered in Ras al-Jinz, along the Omani coast, there is this beautiful comb made of elephant ivory. As well as pots, beads and a copper stamp seal, the comb comes from Harappa, one of the main sites of the Indus civilization.

5. Fragment, from Salut, can be identified as a hollow clay “toy” in the shape of a bird: this kind of artifact is well known from Harappan sites (l. 8.5 cm, w. 7 cm, h. 5.5 cm).

https://www.harappa.com/blog/new-indus-finds-salut-oman

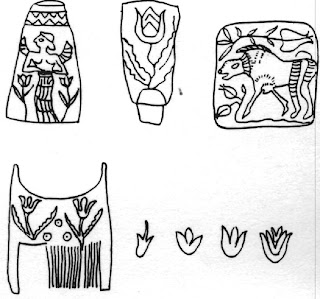

After Fig. 5 in Dennys Frenez (2017) opcit. Ivory comb from Tell Abraq (United Arab Emirates) decorated with a floral motif (1) similar to the one carved on the base of a stone vessel found at Gonur Depe (2) (modified after Potts, 2000: 126; Sarianidi, 2007:112); (3) Ivory comb of Indus style found at Ras Al-Jinz RJ-2 (Sultanate of Oman; photograph by D. Frenez).

After Fig. 9 in Dennys Frenez opcit. (2017): Fig. 9. Stick-dice and gaming pieces in Elephant ivory from Altyn Depe in Margiana and in stone and wood from Shahri Sokhta in Iran (upper register); Stick-dice, decorated sticks and an ivory gaming piece from the Indus Civilization site of Mohenjo-Daro in Pakistan (for Altyn Depe, modified after Masson and Sarianidi, 1972: fig. 117; for Shahr-i Sokhta, courtesy S.M.S. Sajjadi; for Mohenjo-Daro, modified after Mackay, 1931).

Ivory combs from Gonur Depe (After photograph by Dennys Frenez recorded in: Manufacturing and trade of Asian elephant ivory in Bronze Age Middle Asia. Evidence from Gonur Depe (Margiana, Turkmenistan)

See: Vajra and Indus Script ivory hypertexts on a seal, ivory artifacts

https://tinyurl.com/y85goask

m1654 Ivory cube with dotted circles Dotted circle hieroglyphs on each side of the cube (one dotted circle surrounded by 7 dotted circles): dhātu '

See:

http://tinyurl.com/z3x7zev

![]()

Dotted circles, tulips on ivory combs signify dāntā 'ivory' rebus dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (Rigveda) tagaraka 'tulip' rebus tagara 'tin'

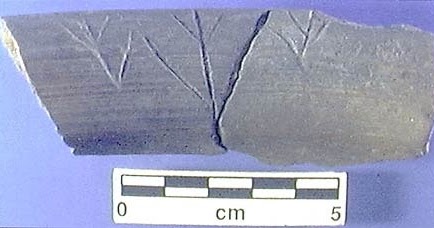

![Image result for Tell abraq comb]() h1522 Potsherd ca. 3300 BCE (from Indus Writing Corpora)

h1522 Potsherd ca. 3300 BCE (from Indus Writing Corpora)

Note: The first known examples of writing may have been unearthed at an archaeological dig in Harappa, Pakistan. So-called 'plant-like' and 'trident-shaped' markings have been found on fragments of pottery dating back 5500 years. According to Dr Richard Meadow of Harvard University, the director of the Harappa Archaeological Research Project, these primitive inscriptions found on pottery may pre-date all other known writing.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/334517.stm http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/334517.stm

The dotted circle as a signifier of interactions between Meluhha and Gonur Tepe has been brilliantly analysed in the context of the following artifacts cited by Dennys Frenez in: Manufacturing and trade of Asian elephant ivory in Bronze Age Middle Asia. Evidence from Gonur Depe (Margiana, Turkmenistan) by Dennys Frenez (2017)

https://www.academia.edu/34596109/Manufacturing_and_trade_of_Asian_elephant_ivory_in_Bronze_Age_Middle_Asia._Evidence_from_Gonur_Depe_Margiana_Turkmenistan

dhāī˜ (Lahnda) signifies a single strand of rope or thread.

I have suggested that a dotted circle hieroglyph is a cross-section of a strand of rope: S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻsubstance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour)ʼ; dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ(Marathi) धवड (p. 436) [ dhavaḍa ] m (Orधावड ) A class or an individual of it. They are smelters of iron (Marathi). Hence, the depiction of a single dotted circle, two dotted circles and three dotted circles (called trefoil) on the robe of the Purifier priest of Mohenjo-daro.

The phoneme dhāī˜ (Lahnda) signifying a single strand may thus signify the hieroglyph: dotted circle. This possibility is reinforced by the glosses in Rigveda, Tamil and other languages of Baratiya sprachbund which are explained by the word dāya 'playing of dice' which is explained by the cognate Tamil word: தாயம் tāyam, n. < dāya Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட

The semantics: dāya 'Number one in the game of dice' is thus signified by the dotted circle on the uttariyam of the pōtṟ पोतृ,'purifier' priest. Rebus rendering in Indus Script cipher is

![OmanTripper - Salut (10)]()

![]() Salut stone seal. (After Fig. 9 in Dennys Frenez et al, 2016) See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2011/12/indus-seal-from-excavation-of-salut.html

Salut stone seal. (After Fig. 9 in Dennys Frenez et al, 2016) See: http://bharatkalyan97.blogspot.com/2011/12/indus-seal-from-excavation-of-salut.html

An Indus Seal from the excavation of the Salut Early Bronze Age tower, December 22, 2011

![]() sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' sal stake, spike, splinter, thorn, difficulty (H.); sal ‘workshop’ (Santali)

sal 'splinter' rebus: sal 'workshop' sal stake, spike, splinter, thorn, difficulty (H.); sal ‘workshop’ (Santali)

![]() Counting in fours: gaṇḍaka m. ʻ a coin worth four cowries ʼ lex., ʻ method of counting by fours ʼ W. [← Mu. Przyluski RoczOrj iv 234]S. g̠aṇḍho m. ʻ four in counting ʼ; P. gaṇḍā m. ʻ four cowries ʼ; B. Or. H. gaṇḍā m. ʻ a group of four, four cowries ʼ; M. gaṇḍā m. ʻ aggregate of four cowries or pice ʼ(CDIAL 4001) rebus: kaṇḍa 'equipment, metalware'. gaṇḍa ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali) Vikalpa: ponea ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: pon ‘gold’ (Ta.)

Counting in fours: gaṇḍaka m. ʻ a coin worth four cowries ʼ lex., ʻ method of counting by fours ʼ W. [← Mu. Przyluski RoczOrj iv 234]S. g̠aṇḍho m. ʻ four in counting ʼ; P. gaṇḍā m. ʻ four cowries ʼ; B. Or. H. gaṇḍā m. ʻ a group of four, four cowries ʼ; M. gaṇḍā m. ʻ aggregate of four cowries or pice ʼ(CDIAL 4001) rebus: kaṇḍa 'equipment, metalware'. gaṇḍa ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: kaṇḍ fire-altar, furnace’ (Santali) Vikalpa: ponea ‘four’ (Santali); rebus: pon ‘gold’ (Ta.)

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() | Thus, the full text message reads: workshop, equipment forge, kancu ʼmũh kharaḍa 'bell metal ingot daybook', ranku 'tin ore.' These cargo items belong to the copper, pewter, tin alloy metal guild merchant: bharat pattāri.

| Thus, the full text message reads: workshop, equipment forge, kancu ʼmũh kharaḍa 'bell metal ingot daybook', ranku 'tin ore.' These cargo items belong to the copper, pewter, tin alloy metal guild merchant: bharat pattāri.

"The discovery of Indus seals manufactured with non-Indus raw materials, but with tools and techniques associated with Indus productions, further supports the idea that merchants and craftsmen from the greater Indus Valley were living and working at interior settlements in the Oman peninsula." This exciting paper reviews the latest finds through 2015 at Salut tower in Oman, which is apparently full of ancient Indus artifacts.

Summary

This study focuses on the nature of interactions and trade between the greater Indus Valley and eastern Arabia during the third millennium BC. The role of Indus trade in eastern Arabia has often been discussed in the general picture of local cultural and economic developments during the Bronze Age, but the organization and mechanism of this important phenomenon are not yet precisely decoded. New evidence from the stone tower ST1 excavated at Salūt, Sultanate of Oman, by the Italian Mission to Oman in collaboration with the Office of the Adviser to His Majesty the Sultan for Cultural Affairs, provided solid information for proposing updated models of transcultural economic interaction. The collection of Indus and Indus-related artefacts from ST1 testifies to an early integration of sites located in the interior of central Oman, within the network of long-distance connections that directly linked the Indus regions with the western shores of the Arabian Sea. The presence of a wide range of Indus pottery types, including utilitarian pottery and specific forms used for food production and presentation, suggests that some degree of cultural interaction occurred along with the expansion of trade. The discovery of Indus seals and carnelian beads possibly manufactured with non-Indus raw materials further supports the hypothesis that merchants and craftsmen from the Indus Valley were living and working in interior Oman during the second half of the third millennium BC. The evidence from ST1 also provides support for similar discoveries from other excavations in Oman and the UAE, suggesting that the interaction between Indus communities and eastern Arabia was much more extensive than previously thought.

Above: Scanning electron microscope image of drill-hole impression of a carnelian bead found in Salut

From Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Volume 46, 2016, Papers from the forty-seventh meeting of the Seminar for Arabian Studies held at the British Museum, London, 24 to 26 July 2015![application/pdf PDF icon]() Bronze-Age-Indus-Connections.pdf (For a copy of the full text, email kalyan97@gmail.com)

Bronze-Age-Indus-Connections.pdf (For a copy of the full text, email kalyan97@gmail.com)

https://tinyurl.com/y85goask

m1654 Ivory cube with dotted circles Dotted circle hieroglyphs on each side of the cube (one dotted circle surrounded by 7 dotted circles): dhātu '

dhā̆vaḍ 'iron-smelters'. Eight dotted circles evoke the Veda tradition of aṣṭāśri Yupa, eight-angled pillar to proclaim the sacred prayers.

See:

Dotted circles, tulips and tin-bronze revolution of 4th millennium BCE documented in Harappa Script

http://tinyurl.com/z3x7zev

In the course of my studies on hieroglyphs of ancient Near East 3rd and 2nd millennium BCE, and the Tin Road of the Bronze Age, I have come across the use of a flower used for perfume oil:tabernae montana as a hieroglyph. I find that this hieroglyph is deployed on hair combs and also on a metal, shaft-hole axe.

In interaction areas, tabernae montana glyph appears: 1. on an ivory comb discovered at Oman Peninsula site of Tell Abraq, 2. on a Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex stone flask and, 3. on a copper alloy shaft-hole axe-head of (unverified provenance) attributed to Southeastern Iran, ca. late 3rd or early 2nd millennium BCE 6.5 in. long, 1980.307 Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The ivory comb found at Tell Abraq measures 11 X 8.2 X .4 cm. Both sides of the comb bear identical, incised decoration in the form of two long-stemmed flowers with crenate or dentate leaves, flanking three dotted circles arranged in a triangular pattern. The occurrence of wild tulip glyph on the ivory comb can be explained.

The spoken word tagaraka connoted a hair fragrance from the flower tagaraka These flowers are identified as tulips, perhaps Mountain tulip or Boeotian tulip (both of which grow in Afghanistan) which have an undulate leaf. There is a possibility that the comb is an import from Bactria, perhaps transmitted through Meluhha to the Oman Peninsula site of Tell Abraq.

At Mundigak, in Afghanistan, only one out of a total of five shaft-hole axes analysed contained as much as 5% Sn. Such shaft-hole implements have also been found at Shah Tepe, Tureng Tepe, and Tepe Hissar in level IIIc (2000-1500 BCE).

Tell Abraq axe with epigraph (‘tulip’ glyph + a person raising his arm above his shoulder and wielding a tool + dotted circles on body) [After Fig. 7 Holly Pittman, 1984, Art of the Bronze Age: Southeastern Iran, Western Central Asia, and the Indus Valley, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 29-30]. ![]()

tabar = a broad axe (Punjabi). Rebus: tam(b)ra ‘copper’ tagara ‘tabernae montana’, ‘tulip’. Rebus: tagara ‘tin’. Glyph: eṛaka ‘upraised arm’ (Tamil); rebus: eraka = copper (Kannada)

A rebus reading of the hieroglyph is: tagaraka, tabernae montana. Rebus: tagara ‘tin’ (Kannada); tamara id. (Skt.) Allograph: ṭagara ‘ram’. Since tagaraka is used as an aromatic unguent for the hair, fragrance, the glyph gets depicted on a stone flask, an ivory comb and axe of Tell Abraq.

The glyph is tabernae montana, ‘mountain tulip’. A soft-stone flask, 6 cm. tall, from Bactria (northern Afghanistan) showing a winged female deity (?) flanked by two flowers similar to those shown on the comb from Tell Abraq.(After Pottier, M.H., 1984, Materiel funeraire e la Bactriane meridionale de l'Age du Bronze, Paris, Editions Recherche sur les Civilisations: plate 20.150) Two flowers are similar to those shown on the comb from Tell Abraq. Ivory comb with Mountain Tulip motif and dotted circles. TA 1649 Tell Abraq. [D.T. Potts, South and Central Asian elements at Tell Abraq (Emirate of Umm al-Qaiwain, United Arab Emirates), c. 2200 BC—AD 400, in Asko Parpola and Petteri Koskikallio, South Asian Archaeology 1993: , pp. 615-666] Tell Abraq comb and axe with epigraph After Fig. 7 Holly Pittman, 1984, Art of the Bronze Age: Southeastern Iran, Western Central Asia, and the Indus Valley, New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, pp. 29-30].

"A fine copper axe-adze from Harappa, and similar bronze examples from Chanhu-daro and, in Baluchistan, at Shahi-tump, are rare imports of the superior shaft-hole implements developed initially in Mesopotamia before 3000 BC. In northern Iran examples have been found at Shah Tepe, Tureng Tepe, and Tepe Hissar in level IIIc (2000-1500 BC)...Tin was more commonly used in eastern Iran, an area only now emerging from obscurity through the excavation of key sites such as Tepe Yahya and Shahdad. In level IVb (ca. 3000 BCE)at Tepe yahya was found a dagger of 3% tin bronze. (Lamberg-Karlovsky, C.C. and M., 1971, An early city in Iran, Scientific American, 1971, 224, No. 6, 102-11; Muhly, 1973, Appendix 11, 347); perhaps the result of using a tin-rich copper ore." (Penhallurick, R.D., 1986, Tin in Antiquity, London, Institute of Metals, pp. 18-32).

Comb discovered in Tell Abraq (ca. 2200 BCE) has two Harappa Script hieroglyphs:

1. dotted circles; and 2. tabernae montana 'mountain tulip' Rebus readings: 1.Hieroglyph: dotted circles: dāntā 'ivory' rebus dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' 2. Hieroglyph: tagaraka 'tabernae montana, mountain tulip' rebus: tagara 'tin'. Thus, two mineral ores are signified by the two hieroglyphs: ferrite, copper ores and tin ore (cassiterite).

Indus Script hypertexts: 1. dotted circles; and 2. tabernae montana 'mountain tulip' Rebus readings: 1.Hieroglyph: dotted circles: dāntā 'ivory' rebus dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' 2. Hieroglyph: tagaraka 'tabernae montana, mountain tulip' rebus: tagara 'tin'. Thus, two mineral ores are signified by the two hieroglyphs: ferrite, copper ores and tin ore (cassiterite).

Dotted circles, tulips on ivory combs signify dāntā 'ivory' rebus dhāˊtu 'ore of red colour' (Rigveda) tagaraka 'tulip' rebus tagara 'tin'

h1522 Potsherd ca. 3300 BCE (from Indus Writing Corpora)

h1522 Potsherd ca. 3300 BCE (from Indus Writing Corpora)Note: The first known examples of writing may have been unearthed at an archaeological dig in Harappa, Pakistan. So-called 'plant-like' and 'trident-shaped' markings have been found on fragments of pottery dating back 5500 years. According to Dr Richard Meadow of Harvard University, the director of the Harappa Archaeological Research Project, these primitive inscriptions found on pottery may pre-date all other known writing.

http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/334517.stm http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/science/nature/334517.stm

A rebus reading of the hieroglyph is: tagaraka, tabernae montana. Rebus:

tagara ‘tin’ (Kannada); tamara id. (Skt.) Allograph: ṭagara ‘ram’. Since tagaraka

is used as an aromatic unguent for the hair, fragrance, the glyph gets depicted on a stone flask, an ivory comb and axe of Tell Abraq.

Discovery of tin-bronzes was momentous in progressing the Bronze Age Revolution of 4th millennium BCE. This discovery created hard alloys combining copper and tin. This discovery was also complemented by the discovery of writing systems to trade in the newly-produced hard alloys.The discovery found substitute hard alloys, to overcome the scarcity of naturally occurring arsenical copper or arsenical bronzes. The early hieroglyph signifiers of tin and copper on an ivory comb made by Meluhha artisans & seafaring merchants point to the contributions made by Bhāratam Janam (RV), ca. 3300 BCE to produce tin-bronzes. The abiding significance of the 'dotted circle' is noted in the continued use on early Punch-marked coins.

https://www.academia.edu/34596109/Manufacturing_and_trade_of_Asian_elephant_ivory_in_Bronze_Age_Middle_Asia._Evidence_from_Gonur_Depe_Margiana_Turkmenistan

dhāī˜ (Lahnda) signifies a single strand of rope or thread.

I have suggested that a dotted circle hieroglyph is a cross-section of a strand of rope: S. dhāī f. ʻ wisp of fibres added from time to time to a rope that is being twisted ʼ, L. dhāī˜ f. Rebus: dhāˊtu n. ʻsubstance ʼ RV., m. ʻ element ʼ MBh., ʻ metal, mineral, ore (esp. of a red colour)ʼ; dhāū, dhāv m.f. ʻ a partic. soft red stone ʼ(Marathi) धवड (p. 436) [ dhavaḍa ] m (Or

The phoneme dhāī˜ (Lahnda) signifying a single strand may thus signify the hieroglyph: dotted circle. This possibility is reinforced by the glosses in Rigveda, Tamil and other languages of Baratiya sprachbund which are explained by the word dāya 'playing of dice' which is explained by the cognate Tamil word: தாயம் tāyam, n. < dāya Number one in the game of dice; கவறுருட்ட

விழும் ஒன்று என்னும் எண்.

The semantics: dāya 'Number one in the game of dice' is thus signified by the dotted circle on the uttariyam of the pōtṟ पोतृ,'purifier' priest. Rebus rendering in Indus Script cipher is

Location of Salut,Oman. After Fig. 2 in Dennys Frenez et al, 2016

Salut (صـلـوت) is an archaeological site near Bisyah (بـسـيـة) village in close proximity to Jabreen in the Al Dakhiliyah region of Oman. Salut archaeological site is a home to an ancient fortified collection of ruins and fortifications, some of which date to over 3,000 years ago, and which offer important evidence of the development civilizations in the Arabic peninsula in the Bronze and Iron ages. https://www.omantripper.com/salut/

Ivory comb of Salut is comparable to the ivory combs from Ras al-Jinz and Tell Abraq

Fig. 19. Salut 1: copper/bronze snake; 2-3: copper/bronze arrowheads; 4: copper/bronze axe; 5: stone ring; 6: copper/bronze cauldron.

An Indus Seal from the excavation of the Salut Early Bronze Age tower, December 22, 2011

Reading of the inscription of text:

Sign134 lid of pot hieroglyph: Hieroglyph: ḍhaṁkaṇa 'lid of pot' rebus dhakka 'excellent, bright, blazing metal article'.

Sign 261 The rhombus sign

This Sign 261 is ligatured with inverted ^ sign which signifies the semantics of kanac 'corner' rebus: kancu 'bell-metal'. kaṁsá 1 m. ʻ metal cup ʼ AV., m.n. ʻ bell -- metal '. Thus, Sign 261 is read as: kancu ʼmũh 'bell-metal ingot'. Sign 270 which is a compositeof Signs 267 and Sign 176 signifies in a Meluhha expression: kancu ʼmũh 'bell-metal ingot' PLUS khareḍo 'a currycomb' (Gujarati) rebus: kharaḍa, 'daybook'. The message of composite Sign 267 is: kancu ʼmũh kharaḍa 'bell metal ingot daybook'.Sign 254 cyphertext (and variants) are a composite of duplicated lonjg lines PLUS Sign 176 ![]() . The hieroglyphs are read rebus: dula 'two' rebus:dul 'metal casting' PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop' PLUS khareḍo 'a currycomb' (Gujarati) rebus: kharaḍa, 'daybook'. Thus, the message is: dul koḍ kharaḍa 'metalcasting workshop daybook'.

. The hieroglyphs are read rebus: dula 'two' rebus:dul 'metal casting' PLUS koḍa 'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop' PLUS khareḍo 'a currycomb' (Gujarati) rebus: kharaḍa, 'daybook'. Thus, the message is: dul koḍ kharaḍa 'metalcasting workshop daybook'.

! (Long linear stroke) koḍa'one' rebus: koḍ 'workshop'

The text of the inscription on Salut stone seal:

Field symbol: Ox with a trough (?) in front. This was a stone seal with a perforated boss and was perhaps tied to a trade load from Meluhha.

The trough signifies pathar rebus: pattāri, ''merchant' of metal alloy: alloy of copper, pewter, tin

barad, barat'ox' Rebus: bharat'alloy of copper, pewter, tin' (Marathi) pattar'

pattar ‘trough’ (Ta.) पात्र pātra, (l.) s. Vessel, cup, plate; receptacle. [lw. Sk. Id.] (Nepali) pātramu A utensil, ఉపకరణము. Hardware. Metal vessels. (Telugu) Rebus paṭṭar-ai community; guild as of workmen (Ta.); pātharī ʻprecious stoneʼ (OMarw.) (CDIAL 8857) Patthara [cp. late Sk. prastara. The ord. meaning of Sk. pr. is "stramentum"] 1. stone, rock S i.32. -- 2. stoneware Miln 2. (Pali) Pa. Pk. patthara -- m. ʻ stone ʼ, S. patharu m., L. (Ju.) pathar m., khet. patthar, P. patthar m. (→ forms of Bi. Mth. Bhoj. H. G. below with atth or ath), WPah.jaun. pātthar; Ku. pāthar m. ʻ slates, stones ʼ, gng. pāth*lr ʻ flat stone ʼ; A. B. pāthar ʻ stone ʼ, Or. pathara; Bi. pāthar, patthar, patthal ʻ hailstone ʼ; Mth. pāthar, pathal ʻ stone ʼ, Bhoj. pathal, Aw.lakh. pāthar, H. pāthar, patthar, pathar, patthal m., G. patthar, pathrɔ m.; M. pāthar f. ʻ flat stone ʼ; Ko. phāttaru ʻ stone ʼ; Si. patura ʻ chip, fragment ʼ; -- S. pathirī f. ʻ stone in the bladder ʼ; P. pathrī f. ʻ small stone ʼ; Ku. patharī ʻ stone cup ʼ; B. pāthri ʻ stone in the bladder, tartar on teeth ʼ; Or. pathurī ʻ stoneware ʼ; H. patthrī f. ʻ grit ʼ, G. pathrī f. *prastarapaṭṭa -- , *prastaramr̥ttikā -- , *prastarāsa -- .Addenda: prastará -- : WPah.kṭg. pátthər m. ʻ stone, rock ʼ; pəthreuṇõ ʻ to stone ʼ; J. pāthar m. ʻ stone ʼ; OMarw. pātharī ʻ precious stone ʼ. (CDIAL 8857)

From one of the higher hills of the large ditch encircling the EBA tower currently excavated by IMTO some 300 m to the north-west of salut, came one stone stamp seal which, by virtue of its iconography, shape and incised inscription, can be considered a genuine (Greater) Indus Valley import. The seal shows a bull, facing right and standing in front of a rectangular feature, possibly an altar or maybe just a manger. Above this scene, stands a line of Indus alphabetical signs. The quality of the glyptic and the close resemblance with specimen coming from Indus Valley sites, seem to indicate that the seal is an original Indus import, rather than an imitation. Such characteristic square stamp seals marked the transition from Early Harappan to Mature Harappan, together with the appearance of the Indus script. This transition is dated around 2500 BC, a date after which various artefacts related to the Indus civilization started to be found in the Near East, from Mesopotamia to Iran, to Failaka and Bahrein. Among the few Bronze Age seals discovered so far in Oman, only two could be compared to the one from Salut EBA tower. One is a stamp seal found in Ras al-Jinz, also bearing Indus signs but made of a copper/bronze, and the other is a stone stamp seal from a tomb in Bisyah, with no inscription. Their overall shape and motifs induce to regard them as well as genuine imports, though in the case of metal seals, only very few examples are known from the Greater Indus Valley, thus leaving some doubts about a possible local production. http://arabiantica.humnet.unipi.it/index.php?id=715&tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=68&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=711&cHash=2fe7666e8c

New Indus Finds in Salut, Oman

June 26th, 2016![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Exciting new discoveries through 2015 at Salut tower in Oman show how extensive Indus trade and relationships with this area were during the Bronze Age (2500-2000 BCE). The article Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction by Denys Frenez, Michele Degli Esposti, Sophie Méry and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer describes and explains the finds in detail. These include include children's toys like a bird whistle, a seal made of chlorite, numerous pottery fragments of types common in places like Harappa, and much else that suggests that Indus traders were active and settled well inside the Omani coast. These recent excavations are led by the Italian Mission to Oman in collaboration with the Office of the Adviser to His Majesty the Sultan for Cultural Affairs.

"This evidence provides support for similar discoveries from excavations of towers and graves in Bāt, and suggests that the interaction between Indus communities and the Omani interior was much more extensive than previously thought," write the authors. Ancient Oman, during what is referred to as the Um al Nair period, is called "Magan" in ancient Mesopotamian texts, was known as a source of copper. The work described in the article below is yet another piece of evidence pointing to the extensive trade that must have once existed among the handful of sophisticated Bronze Age civilizations in the area, supporting wealth generation as well as a the flow of ideologies, beliefs and cultural practices.

Article: Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction

Website: The Salut Museum/Universita di Pisa website

1. Salut archaeological site, Oman. Note that this is not the Bronze Age tower ST1 but the later Iron Age "castle."

2. Seal impressed fragment, likely belonging to an Harappan ledge shouldered jar, the impression showing two confronting bulls and some Harappan script (l 3.6 cm, w. 5.5 cm, th. 0.7 cm).

3. This stone square stamp seal is probably the best example of an Indus-inspired seal found so far in Oman.

4. Among the luxury imported objects discovered in Ras al-Jinz, along the Omani coast, there is this beautiful comb made of elephant ivory. As well as pots, beads and a copper stamp seal, the comb comes from Harappa, one of the main sites of the Indus civilization.

5. Fragment, from Salut, can be identified as a hollow clay “toy” in the shape of a bird: this kind of artifact is well known from Harappan sites (l. 8.5 cm, w. 7 cm, h. 5.5 cm).

June 26th, 2016

Exciting new discoveries through 2015 at Salut tower in Oman show how extensive Indus trade and relationships with this area were during the Bronze Age (2500-2000 BCE). The article Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction by Denys Frenez, Michele Degli Esposti, Sophie Méry and Jonathan Mark Kenoyer describes and explains the finds in detail. These include include children's toys like a bird whistle, a seal made of chlorite, numerous pottery fragments of types common in places like Harappa, and much else that suggests that Indus traders were active and settled well inside the Omani coast. These recent excavations are led by the Italian Mission to Oman in collaboration with the Office of the Adviser to His Majesty the Sultan for Cultural Affairs.

"This evidence provides support for similar discoveries from excavations of towers and graves in Bāt, and suggests that the interaction between Indus communities and the Omani interior was much more extensive than previously thought," write the authors. Ancient Oman, during what is referred to as the Um al Nair period, is called "Magan" in ancient Mesopotamian texts, was known as a source of copper. The work described in the article below is yet another piece of evidence pointing to the extensive trade that must have once existed among the handful of sophisticated Bronze Age civilizations in the area, supporting wealth generation as well as a the flow of ideologies, beliefs and cultural practices.

Article: Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction

Website: The Salut Museum/Universita di Pisa website

1. Salut archaeological site, Oman. Note that this is not the Bronze Age tower ST1 but the later Iron Age "castle."

2. Seal impressed fragment, likely belonging to an Harappan ledge shouldered jar, the impression showing two confronting bulls and some Harappan script (l 3.6 cm, w. 5.5 cm, th. 0.7 cm).

3. This stone square stamp seal is probably the best example of an Indus-inspired seal found so far in Oman.

4. Among the luxury imported objects discovered in Ras al-Jinz, along the Omani coast, there is this beautiful comb made of elephant ivory. As well as pots, beads and a copper stamp seal, the comb comes from Harappa, one of the main sites of the Indus civilization.

5. Fragment, from Salut, can be identified as a hollow clay “toy” in the shape of a bird: this kind of artifact is well known from Harappan sites (l. 8.5 cm, w. 7 cm, h. 5.5 cm).

"This evidence provides support for similar discoveries from excavations of towers and graves in Bāt, and suggests that the interaction between Indus communities and the Omani interior was much more extensive than previously thought," write the authors. Ancient Oman, during what is referred to as the Um al Nair period, is called "Magan" in ancient Mesopotamian texts, was known as a source of copper. The work described in the article below is yet another piece of evidence pointing to the extensive trade that must have once existed among the handful of sophisticated Bronze Age civilizations in the area, supporting wealth generation as well as a the flow of ideologies, beliefs and cultural practices.

Article: Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction

Website: The Salut Museum/Universita di Pisa website

1. Salut archaeological site, Oman. Note that this is not the Bronze Age tower ST1 but the later Iron Age "castle."

2. Seal impressed fragment, likely belonging to an Harappan ledge shouldered jar, the impression showing two confronting bulls and some Harappan script (l 3.6 cm, w. 5.5 cm, th. 0.7 cm).

3. This stone square stamp seal is probably the best example of an Indus-inspired seal found so far in Oman.

4. Among the luxury imported objects discovered in Ras al-Jinz, along the Omani coast, there is this beautiful comb made of elephant ivory. As well as pots, beads and a copper stamp seal, the comb comes from Harappa, one of the main sites of the Indus civilization.

5. Fragment, from Salut, can be identified as a hollow clay “toy” in the shape of a bird: this kind of artifact is well known from Harappan sites (l. 8.5 cm, w. 7 cm, h. 5.5 cm).

Bronze Age Salūt (ST1) and the Indus Civilization: recent discoveries and new insights on regional interaction by

"The discovery of Indus seals manufactured with non-Indus raw materials, but with tools and techniques associated with Indus productions, further supports the idea that merchants and craftsmen from the greater Indus Valley were living and working at interior settlements in the Oman peninsula." This exciting paper reviews the latest finds through 2015 at Salut tower in Oman, which is apparently full of ancient Indus artifacts.

Summary

This study focuses on the nature of interactions and trade between the greater Indus Valley and eastern Arabia during the third millennium BC. The role of Indus trade in eastern Arabia has often been discussed in the general picture of local cultural and economic developments during the Bronze Age, but the organization and mechanism of this important phenomenon are not yet precisely decoded. New evidence from the stone tower ST1 excavated at Salūt, Sultanate of Oman, by the Italian Mission to Oman in collaboration with the Office of the Adviser to His Majesty the Sultan for Cultural Affairs, provided solid information for proposing updated models of transcultural economic interaction. The collection of Indus and Indus-related artefacts from ST1 testifies to an early integration of sites located in the interior of central Oman, within the network of long-distance connections that directly linked the Indus regions with the western shores of the Arabian Sea. The presence of a wide range of Indus pottery types, including utilitarian pottery and specific forms used for food production and presentation, suggests that some degree of cultural interaction occurred along with the expansion of trade. The discovery of Indus seals and carnelian beads possibly manufactured with non-Indus raw materials further supports the hypothesis that merchants and craftsmen from the Indus Valley were living and working in interior Oman during the second half of the third millennium BC. The evidence from ST1 also provides support for similar discoveries from other excavations in Oman and the UAE, suggesting that the interaction between Indus communities and eastern Arabia was much more extensive than previously thought.

Above: Scanning electron microscope image of drill-hole impression of a carnelian bead found in Salut

From Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Volume 46, 2016, Papers from the forty-seventh meeting of the Seminar for Arabian Studies held at the British Museum, London, 24 to 26 July 2015

Salut, ST1 (US98)

Muscat, Office of the Adviser to HM the Sultan for Cultural Affairs

Dark grey stone; H 2.3, D 1.3

Iron Age: 1300-650 BC

The cylinder seal is decorated with a row of five men holding hands that, when rolled, creates a continual motif punctuated at intervals with astral symbols, including a solar disc.

Two stone cylinder seals were discovered from Iron Age contexts related to the re-occupation of the Bronze Age tower ST1, focused on the reuse of its well.

Cylinder seals became widely spread throughout ancient Near and Middle East during the Bronze Age, and remained in use long after, although stamp seals started to be used and finally became preponderant. Very few seals are known form southeast Arabia, and it can be suggested that here they were perceived more like ornaments than real administrative tools. The two seals from ST1 are among the best specimen so far discovered in Oman, especially of Iron Age date. (MdE)

Muscat, Office of the Adviser to HM the Sultan for Cultural Affairs

Dark grey stone; H 2.3, D 1.3

Iron Age: 1300-650 BC

The cylinder seal is decorated with a row of five men holding hands that, when rolled, creates a continual motif punctuated at intervals with astral symbols, including a solar disc.

Two stone cylinder seals were discovered from Iron Age contexts related to the re-occupation of the Bronze Age tower ST1, focused on the reuse of its well.

Cylinder seals became widely spread throughout ancient Near and Middle East during the Bronze Age, and remained in use long after, although stamp seals started to be used and finally became preponderant. Very few seals are known form southeast Arabia, and it can be suggested that here they were perceived more like ornaments than real administrative tools. The two seals from ST1 are among the best specimen so far discovered in Oman, especially of Iron Age date. (MdE)